Bodhi Treeby Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/13/21

The Mahabodhi Tree at the Sri Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya

The Mahabodhi Tree at the Sri Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya Sculpture of the Buddha meditating under the Mahabodhi tree

Sculpture of the Buddha meditating under the Mahabodhi tree The Diamond throne or Vajrashila, where the Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree in Bodh Gaya

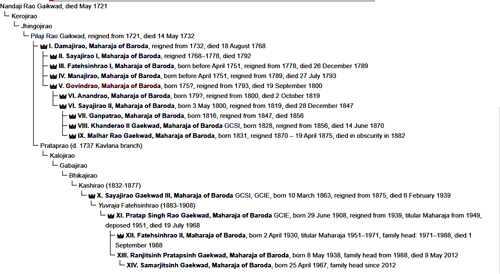

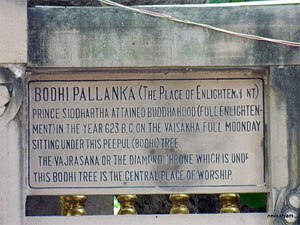

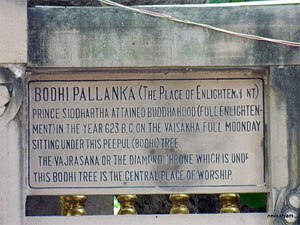

The Diamond throne or Vajrashila, where the Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree in Bodh GayaThe Bodhi Tree or Bodhi Fig Tree ("tree of awakening"[1]), also called the Bo Tree,[2] was a large and ancient sacred fig tree (Ficus religiosa[1][3]) located in Bodh Gaya, Bihar, India. Siddhartha Gautama, the spiritual teacher who became known as the Buddha, is said to have attained enlightenment or Bodhi circa 500 BCE under it.[4] In religious iconography, the Bodhi Tree is recognizable by its heart-shaped leaves, which are usually prominently displayed.

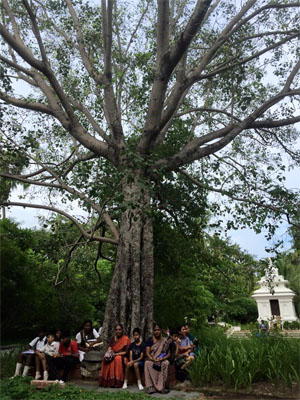

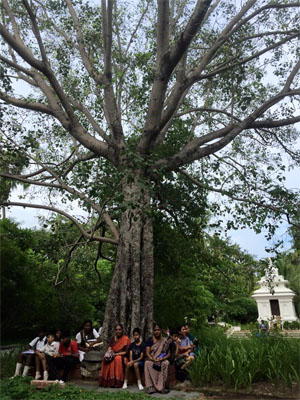

The proper term "Bodhi Tree" is also applied to existing sacred fig (Ficus religiosa) trees, also known as bodhi trees.[5] The foremost example of an existing tree is the Mahabodhi Tree growing at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, which is often cited as a direct descendant of the original tree. This tree, planted around 250 BCE, is a frequent destination for pilgrims, being the most important of the four main Buddhist pilgrimage sites.[6]

Other holy bodhi trees with great significance in the history of Buddhism are the Anandabodhi Tree at Jetavana in Sravasti in North India and the Sri Maha Bodhi Tree in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. Both are also believed to have been propagated from the original Bodhi Tree.

Celebrations

Bodhi DayOn December 8, Bodhi Day celebrates Buddha's enlightenment underneath the Bodhi Tree. Those who follow the Dharma greet each other by saying, “Budu saranai!” which translates to "may the peace of the Buddha be yours.”[7] It is also generally seen as a religious holiday, much like Christmas in the Christian west, in which special meals are served, especially cookies shaped like hearts (referencing the heart-shaped leaves of the Bodhi) and a meal of kheer, the Buddha's first meal ending his six-year asceticism.[8]

Origin and descendants

Bodh Gaya 1810 picture of a small temple beneath the Bodhi tree, Bodh Gaya.[9]

1810 picture of a small temple beneath the Bodhi tree, Bodh Gaya.[9] The Mahabodhi tree in Bodhgaya today

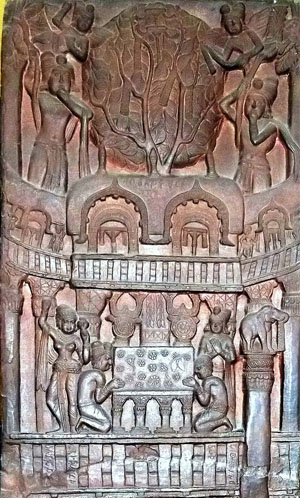

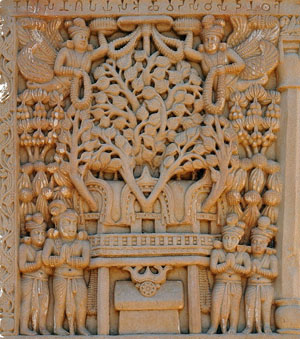

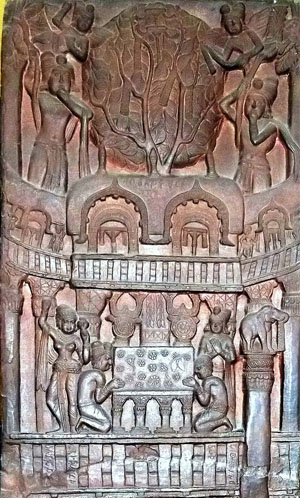

The Mahabodhi tree in Bodhgaya today Illustration of the temple built by Asoka at Bodh-Gaya around the Bodhi tree. Sculpture of the Satavahana period at Sanchi, 1st century CE.

Illustration of the temple built by Asoka at Bodh-Gaya around the Bodhi tree. Sculpture of the Satavahana period at Sanchi, 1st century CE.Main article: Mahabodhi Temple

The Bodhi tree at the Mahabodhi Temple is called the Sri Maha Bodhi. Gautama Buddha attained enlightenment (bodhi) while meditating underneath a Ficus religiosa. According to Buddhist texts, the Buddha meditated without moving from his seat for seven weeks (49 days) under this tree. A shrine called Animisalocana cetiya, was later erected on the spot where he sat.[10]

The spot was used as a shrine even in the lifetime of the Buddha. Emperor Ashoka the Great was most diligent in paying homage to the Bodhi tree, and held a festival every year in its honour in the month of Kattika.[11] His queen, Tissarakkhā, was jealous of the Tree, and three years after she became queen (i.e., in the nineteenth year of Asoka's reign), she caused the tree to be killed by means of mandu thorns.[12] The tree, however, grew again, and a great monastery was attached to the Bodhimanda called the Bodhimanda Vihara. Among those present at the foundation of the Mahā Thūpa are mentioned thirty thousand monks from the Bodhimanda Vihara, led by Cittagutta.[13]The tree was again cut down by King Pushyamitra Shunga in the 2nd century BC, and by King Shashanka in 600 AD. In the 7th century AD, Chinese traveler Xuanzang wrote of the tree in detail.

Bodhi Tree sign, 2013

Bodhi Tree sign, 2013Every time the tree was destroyed, a new tree was planted in the same place.[14]

In 1862 British archaeologist Alexander Cunningham wrote of the site as the first entry in the first volume of the Archaeological Survey of India:The celebrated Bodhi tree still exists, but is very much decayed; one large stem, with three branches to the westward, is still green, but the other branches are barkless and rotten. The green branch perhaps belongs to some younger tree, as there are numerous stems of apparently different trees clustered together. The tree must have been renewed frequently, as the present Pipal is standing on a terrace at least 30 feet above the level of the surrounding country. It was in full vigour in 1811, when seen by Dr. Buchanan (Hamilton), who describes it as in all probability not exceeding 100 years of age.[15]

However, the tree decayed further and in 1876 the remaining tree was destroyed in a storm. In 1881, Cunningham planted a new Bodhi tree on the same site.[16][17]

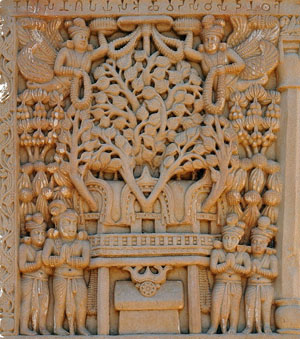

To Jetavana, Sravasti Ashoka's Mahabodhi Temple and Diamond throne in Bodh Gaya, built circa 250 BCE. The inscription between the Chaitya arches reads: "Bhagavato Sakamunino/ bodho" i.e. "The building round the Bodhi tree of the Holy Sakamuni (Shakyamuni)".[18] Bharhut frieze (circa 100 BCE).

Ashoka's Mahabodhi Temple and Diamond throne in Bodh Gaya, built circa 250 BCE. The inscription between the Chaitya arches reads: "Bhagavato Sakamunino/ bodho" i.e. "The building round the Bodhi tree of the Holy Sakamuni (Shakyamuni)".[18] Bharhut frieze (circa 100 BCE).Buddhism recounts that while the Buddha was still alive, in order that people might make their offerings in the name of the Buddha when he was away on pilgrimage, he sanctioned the planting of a seed from the Bodhi tree in Bodhgaya in front of the gateway of Jetavana Monastery near Sravasti. For this purpose Moggallana took a fruit from the tree as it dropped from its stalk before it reached the ground. It was planted in a golden jar by Anathapindika with great pomp and ceremony. A sapling immediately sprouted forth, fifty cubits high, and in order to consecrate it, the Buddha spent one night under it, rapt in meditation. This tree, because it was planted under the direction of Ananda, came to be known as the Ananda Bodhi.

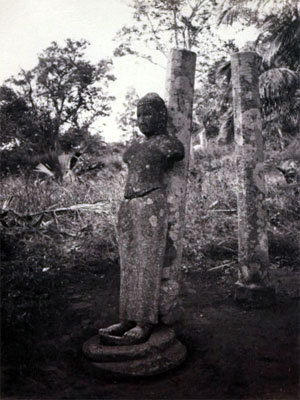

To Anuradhapura, Sri LankaKing Asoka's daughter, Sanghamittra, brought a piece of the tree with her to Sri Lanka where it is continuously growing to this day in the island's ancient capital, Anuradhapura.[16] This Bodhi tree was originally named Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi, and was a piece of another Bodhi tree planted in the year 245 B.C.[19] Although the original Bodhi tree deteriorated and died of old age, the descendants of the branch that was brought by Emperor Ashoka's son, Mahindra, and his daughter, Sanghmittra, can still be found on the island.[20]

According to the Mahavamsa, the Sri Maha Bodhi in Sri Lanka was planted in 288 BC, making it the oldest verified specimen of any angiosperm. In this year (the twelfth year of King Asoka's reign) the right branch of the Bodhi tree was brought by Sanghamittā to Anurādhapura and placed by Devānāmpiyatissa [Devanampiya Tissa of Anuradhapura] his left foot in the Mahāmeghavana. The Buddha, on his death bed, had resolved five things, one being that the branch which should be taken to Ceylon should detach itself.[11] From Gayā, the branch was taken to Pātaliputta, thence to Tāmalittī, where it was placed in a ship and taken to Jambukola, across the sea; finally it arrived at Anuradhapura, staying on the way at Tivakka. Those who assisted the king at the ceremony of the planting of the Tree were the nobles of Kājaragāma and of Candanagāma and of Tivakka.The Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi is also known to be the most sacred Bodhi tree. This came upon the Buddhists who performed rites and rituals near the Bodhi tree. The Bodhi tree was known to cause rain and heal the ill. When an individual became ill, one of his or her relatives would visit the Bodhi tree to water it seven times for seven days and to vow on behalf of the sick for a speedy recovery.[21]

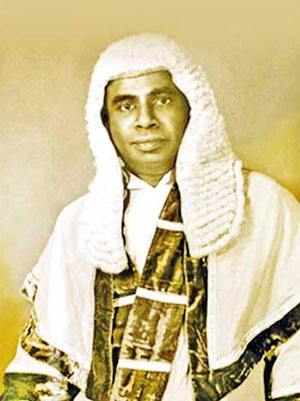

To Honolulu, HawaiiIn 1913,

Anagarika Dharmapala took a sapling of the Sri Maha Bodhi to Hawaii, where he presented it to his benefactor,

Mary Foster, who had funded much Buddhist missionary work. She planted it in the grounds of her house in Honolulu, by the Nuʻuanu stream. On her death, she left her house and its grounds to the people of Honolulu, and it became the Foster Botanical Garden.

To Chennai, India Sapling of the Maha bodhi tree planted in the year 1950 at Theosophical society

Sapling of the Maha bodhi tree planted in the year 1950 at Theosophical societyIn 1950, Jinarajadasa took three saplings of the Sri Maha Bodhi to plant two saplings in Chennai, one was planted near the Buddha temple at the Theosophical Society another at the riverside of Adyar Estuary. The third was planted near a meditation center in Sri Lanka.[22]

To Thousand Oaks, California, USAIn 2012, Brahmanda Pratap Barua, Ripon, Dhaka, Bangladesh, took a sapling of Bodhi tree from Buddha Gaya, Maha Bodhi to Thousand Oaks, California, where he presented it to his benefactor, Anagarika Glenn Hughes, who had funded much Buddhist work and teaches Buddhism in the USA. He and his students received the sapling with a great thanks, later they planted the sapling in the ground in a nearby park.

To Nihon-ji, JapanIn 1989, the government of India presented Nihon-ji with a sapling from the Bodhi Tree as a gesture of world peace.

The trees of the previous BuddhasAccording to the Mahavamsa,[23] branches from the Bodhi trees of all the Buddhas born during this kalpa were planted in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) on the spot where the sacred Bodhi tree stands today in Anurādhapura. The branch of Kakusandha's tree was brought by Rucānandā, Konagamana's by Kantakānandā (or Kanakadattā), and Kassapa's by Sudhammā.

See also  Terracotta Bodhi leaf with dragon decoration, 13th-14th century, Vietnam

Terracotta Bodhi leaf with dragon decoration, 13th-14th century, Vietnam• Bodhi

• Atamasthana

References1. Gethin, Rupert (1998). The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780192892232.

2. Library, C. N. N. "Buddhism Fast Facts". CNN. Retrieved 2019-10-14.

3. Simon Gardner, Pindar Sidisunthorn and Lai Ee May, 2011. Heritage Trees of Penang. Penang: Areca Books. ISBN 978-967-57190-6-6

4. Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 176.

5. "Ficus religiosa - Plant Finder".

http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

6. "Botanic Notables: The Bodhi Tree - Garden Design". GardenDesign.com. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

7. "University of Hawaii".[dead link]

8. Prasoon, Shrikant (2007). Knowing Buddha : [life and teachings]. [Delhi]: Hindoology Books. ISBN 9788122309638.

9. Bodhi Tree British Library.

10. Animisalocana cetiya

11. "CHAPTER XVII_The Arrival Of The Relics". Mahavamsa, chap. 17, 17.

12. "CHAPTER XX_The Nibbana Of The Thera". Mahavamsa, chap. 20, 4f.

13. "CHAPTER XXIX_The Beginning Of The Great Thupa". Mahavamsa, chap. 29, 41.

14. J. Gordon, Melton; Martin, Baumann (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, Second edition. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara. p. 358. ISBN 978-1598842043.

15. Archaeological Survey of India, Volume 1, Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-66

16. "Buddhist Studies: Bodhi Tree". Buddhanet.net. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

17. Mahâbodhi, or the great Buddhist temple under the Bodhi tree at Buddha-Gaya, Alexander Cunningham, 1892: "I next saw the tree in 1871 and again in 1875, when it had become completely decayed, and shortly afterwards in 1876 the only remaining portion of the tree fell over the west wall during a storm, and the old pipal tree was gone. Many seeds, however, had been collected and the young scion of the parent tree were already in existence to take its place."

18. Luders, Heinrich (1963). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol.2 Pt.2 Bharhut Inscriptions. p. 95.

19. K.H.J. Wijayadasa. "Śrī Maha Bodhi". Srimahabodhi.org. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

20. George Boeree. "History of Buddhism". Webspace.ship.edu. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

21. "Rain-makers: The Sacred Bodhi Tree Part 2". Srimahabodhi.org. 2003-04-24. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

22. Madhavan, Chitra. "Buddhist shrine in Adyar". Madras Musings. Madras Musings. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

23. "CHAPTER XV_The Acceptance Of The Mahavihara". For example, chap 15.

***********************************

A Review on Ficus Religiosa -- An Important Medicinal Plantby Shailendra Singh *, S. K. Jain, Shashi Alok, Dilip Chanchal and Surabhi Rashi

Published: January 31, 2016

© 2015 by International Journal of Life Sciences and Review

*Department of Pharmacognosy, Institute of Pharmacy, Bundelkhand University, Jhansi- 284128, Uttar Pradesh, India.

ABSTRACT: Ficus religiosa Linn. is a large evergreen tree found throughout India, wild as well as cultivated, it is widely branched tree with leathery, heart-shaped, long tipped leaves. It is a sacred plant in India. It is one of the most versatile plants having a wide variety of medicinal activities, therefore, used in the treatment of several types of diseases, e.g., diarrhea, diabetes, urinary disorders, burns, hemorrhoids, gastrohelcosis, skin diseases, convulsions, tuberculosis, fever, paralysis, oxidative stress, bacterial infections, etc. This is a unique source of various types of compounds having diverse chemical structure (phenolics, sterols etc.). In this article, we will review the knowledge regarding peepal.

Keywords: Ficus religiosa, Different Species of Ficus, Pharmacognosy, Phytochemistry, Pharmacological activities, Medicinal usesINTRODUCTION: Medicinal plants are naturally gifted with invaluable bioactive compounds which form the backbone of traditional medicines 1. To increase the wide range of medicinal usages, the present day entails new drugs with more potent and desired activity with less or no side effects against particular disease 2. The use of plants as medicines antedates history 1. Medicinal plants have served through ages, as a constant source of medicaments for the exposure of a variety of diseases, as they have curative properties due to the presence of various complex chemical substances of different composition, which are found as secondary plant metabolites in one or more parts of these plants 3.

The history of herbal medicine is almost as old as human civilization 4, 5, and traditional medicines from plants have attracted major attention worldwide because of their potential pharmaceutical importance 6. The material medica provides a great deal of information on the folklore practices and traditional aspects of therapeutically important natural products. Indian traditional medicine is based on various systems including Ayurveda, Siddha, Unani, and Homoeopathy 8. Any part of the plant may contain active components like bark, leaves, flowers, roots, fruits, seeds, etc. 9 The beneficial medicinal effects of plant materials typically result from the combinations of secondary products present in the plant.

Ficus: It is a genus of about 800 species and 2000 varieties, which are woody trees, shrubs and vines in the family Moraceae occurring in most tropical and subtropical forests worldwide 10. It is collectively known as fig trees, and the most well-known species in the genus is the common fig which produces commercial fruit called fig 11. Ficus is one of the most loved bonsai. It is an excellent tree for beginners, as most species of Ficus are fast growers, tolerant of most any soil and light conditions. About half of the species of Ficus are monoecious, and the rest are functionally dioecious 12. Many Ficus species are commonly used in traditional medicine to cure various diseases. They have long been used in folk medicine as astringents carminatives, stomachics, vermicides, hypotensives, antihelmintics and anti-dysentery drugs 13. Many species are cultivated for shade and ornament in gardens. Several species produce edible figs of varying palatability. All species possess latex-like material within their vasculatures that provide protection and self-healing from physical assaults 14. The fig is a very nourishing food and used in industrial products.

Figs contained water, fats, high amounts of amino acids, such as leucine, lysine, valine, and arginine, and minerals, such as potassium, calcium, magnesium, sodium, phosphorus and Vitamins 15.

Taxonomy of Ficus:Domain: Eukaryota

Kingdom: Plantae

Subkingdom: Viridaeplantae

Phylum: Tracheophyta

Subphylum: Euphyllophytina

Infraphylum: Radiatopses

Class: Magnoliopsida

Subclass: Dilleniidae

Superorder: Urticanae

Order: Urticales

Family: Moraceae

Genus: Ficus

Various Species of Ficus are: 16

Ficus altissima (council tree)

Ficus aspera (clown fig)

Ficus auriculata, [Leaves, fruits, bark] syn. Ficus roxburghii

Ficus asperifolia [Young stems]

Ficus benghalensis (Indian banyan) [Wood, leaves, bark, roots]

Ficus benjamina (weeping fig) [Fruits]

Ficus benjamina ‘Exotica

Ficus benjamina ‘Comosa

Ficus binnendykii (narrow-leaf ficus)

Ficus carica (common edible fig) [Fruit latex, leaves]

Ficus celebinsis (willow ficus)

Ficus capensis [Leaves, stem bark]

Ficus deltoidea (mistletoe fig) syn. Ficus diversifolia [Leaves]

Ficus elastica (Indian rubber tree) [Young stems]

Ficus elastica ‘Abidjan’

Ficus elastica ‘Asahi’

Ficus elastica ‘Decora’

Ficus elastica ‘Gold’

Ficus elastica ‘Schrijveriana’

Ficus exasperate [Leaves]

Ficus glomerata [Bark]

Ficus lacor (pakur tree)

Ficus lingua (box-leaved fig) syn. Ficus buxifolia

Ficus lyrata (fiddle-leaf fig) [Leaves, fruit latex]

Ficus macrophylla (Moreton Bay fig)

Ficus microcarpa (Chinese banyan)

Ficus microcarpa var. crassifolia (wax ficus)

Ficus microcarpa ‘Variegata.’

Ficus nitida [Wood, bark, leaves, young stems]

Ficus palmata [Leaves, fruits, bark, root]

Ficus pseudopalma (Philippine fig)

Ficus pumila (creeping fig) syn. Ficus repens

Ficus polita [Roots]

Ficus racemosa [Roots, bark]

Ficus religiosa (bo tree or sacred fig) [Bark, fruits, leaves]

Ficus retusa [Aerial parts]

Ficus rubiginosa (Port Jackson fig or rusty fig)

Ficus rubiginosa ‘Variegata.’

Ficus sagittata ‘Variegata’, syn. Ficus radicans ‘Variegata’

Ficus saussureana, syn. Ficus dawei

Ficus stricta

Ficus subulata, syn. Ficus salicifolia

Ficus sycomorus [Fruits]

Ficus tikoua (Waipahu fig)

Ficus tsiela [Leaves]

Ficus religiosa: Ficus religiosa Linn. (Moraceae) commonly known as ‘Peepal tree’ is a large widely branched tree with leathery, heart-shaped, long tipped leaves on long slender petioles and purple fruits growing in pairs 17, 18, 19.

It is a large perennial tree, glabrous when young, found throughout the plains of India up to 170 m altitudes in the Himalayas 20 and is one of the most revered trees in Asia.

FIG. 1: PLANT OF FICUS RELIGIOSA

FIG. 1: PLANT OF FICUS RELIGIOSAIt is also known as, the sacred fig tree or Bo tree and is the most planted tree species near religious or spiritual places in Indian cities and villages. It grows up to elevations of 5,000 feet 21.

History: Ficus religiosa has got mythological, religious and medicinal importance in Indian culture. References to Ficus religiosa are found in several ancient holy texts like Arthasastra, Puranas, Upanisads, Ramayana, Mahabharata, Bhagavadgita and Buddhistic literature, etc. 22 The Brahma Purana and the Padma Purana, relate how once, when the demons defeated the Gods, Vishnu hide in the peepal. The Skanda Purana also considers the peepal, a symbol of Vishnu. He is believed to have been born under this tree. Some believe that the tree houses the Trimurti, the roots being Brahma, the trunk Vishnu and the leaves Shiva. The Gods are said to hold their councils under this tree and so it is associated with spiritual understanding. The peepal is also closely linked to Krishna.

In the Bhagavad Gita, he says: "Among trees, I am the ashvattha." Krishna is believed to have died under this tree, after which the present Kali Yuga is said to have begun. According to the Skanda Purana, if one does not have a son, the peepal should be regarded as one. As long as the tree lives, the family name will continue. To cut down a peepal is considered a sin equivalent to killing a Brahmin, one of the five deadly sins or Panchapataka. According to the Skanda Purana, a person goes to hell for doing so. Some people are particular to touch the peepal only on a Saturday. The Brahma Purana explains why saying that Ashvattha and peepala were two demons who harassed people.

Ashvattha would take the form of a peepal and peepala the form of a Brahmin. The fake Brahmin would advise people to touch the tree, and as soon as they did, Ashvattha would kill them. Later they were both killed by Shani. Because of his influence, it is considered safe to touch the tree on Saturdays. Lakshmi is also believed to inhabit the tree on Saturdays. Therefore it is considered auspicious to worship it. Women ask the tree to bless them with a son tying a red thread or red cloth around its trunk or on its branches 23.Nomenclature: 'Ficus' is the Latin word for 'Fig,' the fruit of the tree. 'Religiosa' refers to 'religion' because the tree is sacred in both Hinduism and Buddhism and is very frequently planted in temples and shrines of both faiths. 'Bodhi' or its short form 'Bo' means 'supreme knowledge' or 'awakening' in the old Indian languages, (Bo-Tree) is a well-known symbol for happiness, prosperity, longevity and good luck. The name ‘Sacred Fig’ was given to it because it is considered sacred by the followers of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism 24.

'Pipal' relates (I believe) to the same ancient roots which give rise to English words like 'Pip' and 'Apple' and therefore mean something like 'fruit-bearing tree.' 'Ashwattha' and 'Ashvattha' come from an ancient Indian root word "Shwa" means 'morning' or 'tomorrow.' This refers to the fact that Ashwattha is the mythical Hindu world tree, both indestructible and yet ever-changing: the same tree will not be there tomorrow 25.

Taxonomy/Botanical Classification: 26

Domain: Eukaryota

Kingdom: Plantae

Subkingdom: Viridaeplantae

Phylum: Tracheophyta

Subphylum: Spermatophytina

Infraphylum: Angiospermae

Class: Magnoliopsida

Subclass: Dilleniidae.

Super order: Urticanae

Order: Urticales

Family: Moraceae

Division: Magnoliophyta

Tribe: Ficeae

Genus: Ficus (FY-kus) L.

Specific epithet: religiosa L.

Common Names: 24

Assamese: Ahant

Bengali: Asvattha, Ashud, Ashvattha.

English: Pipal tree.

Gujrati: Jari, Piparo, Pipalo, Piplo.

Hindi: Pipal, Pipali.

Kannada: Arlo, Ranji, Basri, Ashvatthanara, Ashwatha, Aralimara, Aralegida, Ashvathamara, Basari, Ashvattha.

Kanarese: Arani, Ashwatha mara, Pippala, Ragi.

Kashmiri: Bad.

Malayalam: Arayal

Marathi: Pimpal, Pipal, Pippal.

Oriya: Aswatha.

Punjabi: Pipal, Pippal

Sanskrit: Ashvattha, Bodhidruma, Pippala, Shuchidruma, Vrikshraj, yajnika.

Tamil: Ashwarthan, Arasamaram, Arasan, Arasu, Arara.

Telgu: Ravichettu.

Habitat: Ficus religiosa is known to be a native Indian tree and thought to be originating mainly in Northern and Eastern India, where it widely found in uplands and plane areas and grows up to about 1650 meters or 5000 ft in the mountainous areas. It is also found growing elsewhere in India and throughout the subcontinent and Southern Asia, especially in Buddhist countries, wild or cultivated.

It is a familiar sight in Hindu temples, Buddhist monasteries and shrines, villages and at roadsides. People also like to grow this sacred tree in their gardens. Ficus religiosa has also been widely planted in many hot countries all over the world from South Africa to Hawai and Florida, but it is not able to naturalize away from its Indian home, because of its dependence on its pollinator wasp, Blastophaga quadraticeps. An exception to this rule is Israel where the wasp has been successfully introduced 27.

Microscopy: An external feature of bark shows that bark differentiated into thick outer periderm and inner secondary phloem. The periderm is differentiated into phellem and phelloderm. Phellem zone is 360 mm thick, wavy, uneven in transection. Phellem cells are organized into thin tangential membranous layers, and older layers exfoliate in the form of thin membranes, whereas phelloderm zone is broad and distinct and are turned into lignified sclereids. Secondary phloem differentiated into inner narrow non collapsed zone which consists of radial files of sieve tube membranes, axial parenchyma, gelatinous fibers, and outer collapsed phloem consists of dilated rays, crushed, obliterated sieve tube membranes, thick walled and lignified fibers, abundant tannin filled parenchyma cells 28.

Transverse section of bark shows rectangular to cubical, thick-walled cork cells and dead elements of the secondary cortex, consist of masses of stone cells; cork cambium distinct with rows of the newly formed secondary cortex, mostly composed of stone cells towards the periphery. Stone cells found scattered in large groups, rarely isolated; most of the parenchymatous cells of secondary cortex contain numerous starch grains and few prismatic crystals of calcium oxalate; secondary phloem a wide zone, consisting of sieve elements, phloem fibers in singles or groups of two and non lignified; numerous crystal fibers also present; in outer region sieve elements mostly collapsed while in inner region intact; phloem parenchyma mostly thick-walled; stone cells present in single or in small groups similar to those in secondary cortex; a number of ray-cells and phloem parenchyma filled with brown pigments; prismatic crystals of calcium oxalate and starch grains present in a number of parenchymatous cells; medullary rays uni to multiseriate, wider towards outer periphery composed of thick-walled cells with simple pits; in tangential section ray cells circular to oval in shape; cambium when present, consists of 2-4 layers of thin-walled rectangular cells 29.

Phytochemistry: Phytochemistry is the chemistry of plants or chemical constituents of plants. Phytochemistry understood in pharmacy as the chemistry of natural products used as drugs or of drugs plants with the emphasis on biochemistry. The constituents are therapeutically active or inactive. The inactive constituents are structural constituents of the plants like starch, sugars, or proteins. The inactive constituents have however pharmaceutical uses. The active constituents are secondary metabolites, like alkaloids glycosides, volatile oils, tannins etc. They are single substances or usually mixtures of several substances. The secondary products of metabolism are formed from primary products and the plant is not able to reutilize them, and they are deposited in the cells and so are called secondary metabolites 30.

TABLE 1: CHEMICAL COMPOUNDS CONTAINED BY DIFFERENT PARTS OF F. RELIGIOSA

S. no Plant part Compound present

1 Roots Tannins, wax, saponin, leucoanthocyanins, delphinindin-3-O-α-Lrhamnoside (II), Pelargonidin-3-O-α-Lrhamnoside, Leucocyanidine-3-O-β-D-galactosyl-cellobioside (III), Leucoanthocyanidin-20-tetratriaconten-2-one, pentatriacontan-5-one, 6 heptatria content-10-one, mesoanisosital 31

2 Bark Phenols, tannins, steroids, alkaloids, flavonoids, β-sitosteryl-d-glucoside, vitamin K, noctacosanol, methyl oleanolate, lanosterol, stigmasterol, lupen-3-one 31

3 Fruits Proteins (4.9 %), essential amino acids (isoleucine and phenylalanine), flavonols (kaempeferol, quercetine, myricetin), also contain good amount of total phenolic contents, total flavonoids, percent inhibition of linoleic acid 32, asgaragine, tyrosine, undecane, tridecane, tetradecane, (e)-β-ocimene, α-thujene, α-pinene, β-pinene, α-terpinene, limonene, dendrolasine, α-ylangene, α-copaene, β-bourbonene, β-caryophyllene, α-trans bergamotene, aromadendrene, α-humulene, alloaromadendrene, germacrene, δ-cadinene, γ-cadinene

4 Seeds Phytosteroline, β-sitosterol and its glycoside, albuminoids, carbohydrates, fatty matter, colouring matter, caoutchoue 0.7-1.5% 33

5 Leaves Campestrol, stigmasterol, isofucosterol, α-amyrin, lupeol, tannic acid, arginine, serine, aspartic acid, glycine, threonine, alanine, proline, tryptophan, tyrosine, methionine, , valine, isoleucine, leucine, n-nonacosane, n-hentricontanen, hexa-cosanol 34-36

F. religiosa releases oxygen all the time, which makes it different from other plants. Most of the plants largely uptake Carbon dioxide (CO2) and release oxygen during the day (photosynthesis) and uptake oxygen and release CO2 during the night (respiration). Some plants such as F. religiosa (peepal) can uptake CO2 during the night also like a day because of their ability to perform a type of photosynthesis called Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM). Peepal is a hemiepiphyte in its native habitat, i.e. the seeds germinate and grow as an epiphyte on other trees and then when the host tree dies, they establish on the soil. It has been suggested that when they live as an epiphyte, they use CAM pathway to produce carbohydrates and when they live on soil, they switch to C3 type photosynthesis 37.

Ethnopharmacology:TABLE 2: ETHNOMEDICINAL USES OF DIFFERENT PARTS Plant parts Traditional uses (as/in)

Bark Astringent, cooling, aphrodisiac, antibacterial against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, gonorrhea, diarrhea, dysentery, hemorrhoids, gastrohelcosis, anti-inflammatory, burns 38

Leaves and tender shoots Purgative, wounds, skin diseases 38

Fruits Asthma, laxative, digestive 38

Seeds Refrigerants, laxative 38

Latex Neuralgia, inflammation, haemorrhages 38

Leaf juice Asthma, cough, sexual disorders, diarrhea, haematuria, toothache, migraine, eye troubles, gastric problems, scabies 38-40

Dry fruit Tuberculosis, fever, paralysis, hemorrhoids 41

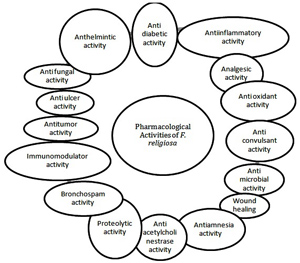

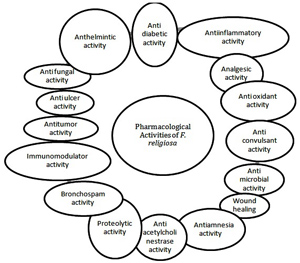

Pharmacological Activities: FIG. 2: PHARMACOLOGICAL ACTIVITIES OF FICUS RELIGIOSAAnti-diabetic Activity:

FIG. 2: PHARMACOLOGICAL ACTIVITIES OF FICUS RELIGIOSAAnti-diabetic Activity: Aqueous extract in a dose of 50 and 100 mg/kg shows pronounced reduction in blood glucose levels in normal, glucose-loaded hyperglycemic and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and effect was compared with glibenclamide (a well known hypoglycaemic drug). Aqueous extract of F. religiosa showed a significant increase in serum, insulin, body weight, glycogen content in liver and skeletal muscle of STZ induced diabetic rats. The results suggested potential traditional use of F. religiosa 42.

Anti-inflammatory Activity: A study was investigated for the effect of methanol extract of F. religiosa leaf on lipopolysaccharide-induced production of NO and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin beta (IL) and IL-6 in BV-2 microglial cells, a microglial mouse line. The methanol extract of leaf inhibited LPS-induced production of NO and proinflammatory cytokines in a dose-dependent manner 43. The methanolic extract of stem bark has shown significant anti-inflammatory activities orally. A significant anti-inflammatory effect has been observed in acute and chronic models of inflammation, the extract also protected mast cells from degradation induced by various degranulators 44, a paste of powdered bark is a good absorbent for inflammatory swellings and can be used to treat burns 45, 46.

Analgesic Activity: This activity of stem bark methanolic extract using the acetic acid-induced writhing (extension of the hind paw) model in mice. Aspirin was used as standard drugs. It exhibited a reduction in the number of writhing. This suggested that extract showed the analgesic effect probably by inhibiting synthesis or action of prostaglandins 47.

Antioxidant Activity: The ethanolic extract of leaves of Ficus religiosa was evaluated for antioxidant (DPPH) activity. The tested extract of different dilutions in the range 200 µg/ml to 1000 µg/ml shows antioxidant activity in a range of 6.34% to 13.35% 48. Root extracts showed significant antioxidant activity against carbon tetrachloride induced liver injury in rats 49. A recent study has also revealed that the methanol extract contains high total phenolic and total flavonoids contents, exhibits high antioxidant activity 50.

The antioxidant activity of the aqueous extract of F. religiosa was investigated in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Since the oxidative stress is the major cause and consequence of Type 2 diabetes. Free radicals generated during oxidative stress damage the insulin receptors and thereby decrease the number of sites available for insulin function. The aqueous extract drug reported to contain tannins, flavonoids, and polyphenols. At doses 100 and 200 mg/kg of aqueous extracts of F. religiosa shows significant decrease in fasting blood glucose and an increase in body weight of diabetic rats as compared to untreated rats. The results are suggesting that the F. religiosa, a Rasayana group of plant drug having antidiabetic along with antioxidant potential, was beneficial in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes 51.

Anticonvulsant Activity: The methanol extract of figs (fruits) exhibits dose-dependent anticonvulsant activity against maximum electroshock and picrotoxin-induced convulsions through serotonergic pathways modulation. The anticonvulsant activity of the extract is studied in strychnine-, pentylenetetrazole, picrotoxin- and isoniazid-induced seizures in mice 52. Acute toxicity, neurotoxicity, and potentiation of phenobarbitone induced sleep by extract were also studied 53.

Antimicrobial Activity: The antimicrobial activity of ethanolic extracts of F. religiosa (leaves) was examined using the agar well diffusion method. The test was performed against four bacteria: Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and against two fungi: Candida albicans and Aspergillus niger. The results showed that 25mg/ml of the extract was active against all bacterial strains and effect against the two fungi was comparatively much less 54. F. religiosa (leaves) demonstrated the more antibacterial activity with less antifungal activity 55. F. religiosa bark methanolic extract was 100% lethal for Haemonchus. contortus worms during in vitro testing 56. The chloroform extracts of F. religiosa showed a strong inhibitory activity against growth infectious Salmonella typhi, Salmonella typhimurium and Proteus vulgaris at a MIC of 39, 5 and 20 µg/ml respectively 57.

Wound Healing: The wound healing activity was investigated by excision and incision wound models using F. religiosa leaf extracts, prepared as an ointment (5 and 10%) were applied on Wistar albino strain rats. Povidine iodine 5% was used as a Standard drug. The high rate of wound contraction, decrease in the period for epithelialization, high skin breaking strength were observed in animals treated with 10% leaf extract ointment when compared to the control group of animals. It has been reported that tannins possess the ability to increase the collagen content, which is one of the factors for the promotion of wound healing 48, 2. The ethanol bark extract was reported to possess wound healing 58.

Anti-amnesia Activity: The anti-amnesic activity was investigated using methanol extract of figs on scopolamine-induced anterograde and retrograde amnesia in mice. Figs were known to contain a high serotonergic content, and modulation of serotonergic neurotransmission plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of amnesia 59.

Anti-acetylcholinesterase Activity: Methanolic extract of the stem bark of F. religiosa found to inhibit the acetylcholinesterase enzyme, thereby prolonging the half-life of acetylcholine. It was reported that most accepted strategies in Alzheimer's diseases treatment are the use of cholinesterase inhibitors. The calculated 50% inhibitory dose (ID50) value was 73.69 µg/ml, respectively. The results confirm and justify the popular traditional use of this plant for the treatment of Alzheimer's diseases 60.

Proteolytic Activity: A comparison of the proteolytic activity of the latex of 46 species of Ficus has been done by electrophoretic and chromatographic properties of the protein components, and F. religiosa has shown a significant proteolytic activity 61.

Bronchospasm Activity: The in-vivo studies of histamine-induced bronchospasm in guinea pigs and in vitro isolated guinea pig tracheal chain and ileum preparation were performed. Pre-treatment of guinea pigs with ketotifen (1 mg/kg, p.o.), has significantly delayed the onset of histamine aerosol-induced pre convulsive dyspnea, compared with vehicle control (281.8 ± 11.7 vs112.2 ± 9.8). The administration of the methanolic extract (125, 250, and 500 mg/kg, p.o.) did not produce any significant effect on latency to develop histamine-induced pre-convulsive dyspnea. Methanolic extract of fruits at doses (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/ml) has significantly potentiated the EC50 doses of both histamine and acetylcholine in isolated guinea pig tracheal chain and ileum preparation. HPLC analysis of methanolic extract showed the presence of high amounts of serotonin (2.89% w/w) 62.

Immunomodulatory Activity: The immuno-modulatory effect of alcoholic extract of the bark of F. religiosa (Moraceae) in mice was investigated. The study was carried out by various hematological and serological tests. Administration of extract remarkably ameliorated both cellular and tic rats while there was humoral antibody response. It is concluded that the test extract possessed promising immunostimulant properties 63.

Antibacterial and Antitumor Activity: The aqueous, methanol and chloroform extracts of the leaves of Ficus religiosa were evaluated for their antibacterial and antitumor activities. These extracts showed an elevated level of antibacterial activity and reduced antifungal activity. The most sensitive organisms S. typhi, P. vulgaris, S. typhimurium, and E. coli were inhibited even at lowest concentrations of the chloroform extracts. Aqueous and methanolic extracts were found to be less active. The antitumor activity conducted by crown gall potato disc assay proved that all the three extracts are efficient in reducing the tumors formed 64.

Antiulcer Activity: The antiulcer potential of the ethanol extract of stem bark of Ficus religiosa against in vivo indomethacin, cold restrained stress-induced gastric ulcer, and pylorus ligation assays were validated. The extract (100, 200, and 400 mg/kg) significantly (P<0.05) reduced the ulcer index in all assays used. The extract also significantly increased the pH of gastric acid while at the same time reduced the volume of gastric juice, free and total acidities. The study provides preliminary data on the antiulcer potential of Ficus religiosa stem bark and supports the traditional uses of the plant for the treatment of gastric ulcer 65.

Antifungal Activity: The benzene extract of both the plants, i.e. Ficus infectoria Roxb. and Ficus religiosa Linn. afforded furanocoumarins, bergapten, and bergaptol. The isolated compounds of both the plants were assayed against its microorganisms Staphylococcus aureus, E scherichia coli, Penicillium gluacum, and Paramecium at a concentration of 0.2% for aqueous bark extracts and 1x10-2 M for the isolated compounds. The results indicate bacterial activity of both the compounds bergapten and bergaptol against S. aureus and E. coli. Antifungal activity of the compounds against P. gluacum was also observed 66.

Anthelmintic Activity: Ficus religiosa has been used to treat parasitic infections in man and animals. The anthelmintic effect of methanolic bark extract of F. religiosa on the adult Haemonchus contortus Worm. Adult motile H. Contortus was collected from the gastrointestinal tract of sheep slaughtered at Faisalabad slaughterhouse. It was found that ficin is responsible for the anthelmintic effect in the methanolic extract of F. religiosa 67. Further, studies show that the aqueous extract of the fruit of F. religiosa has shown potent Anthelmintic activity as compared to other species of Ficus against Pheretima posthuma (earthworms).

CONCLUSION: India is the largest producer of medicinal herbs and is rightly called the botanical garden of the world. The study of herbal medicine spans the knowledge of pharmacology, history, source, physical and chemical nature, mechanism of action, traditional medicinal, and therapeutic use of the drug.

F. religiosa is a widely branched deciduous tree with leathery, heart-shaped, long tipped leaves used in the Indian system of medicine since very ancient times. It is one of the versatile plant having a wide variety of medicinal activities therefore used in the treatment of several types of diseases, for example, Diarrhoea, diabetes, urinary disorders, burns, hemorrhoids, gastrohelcosis, skin diseases, convulsion, tuberculosis, fever, paralysis, oxidative stress, bacterial infection, etc.

Presently, there is an increasing interest worldwide in herbal medicines accompanied by increased laboratory investigation into the pharmacological properties of the bioactive ingredients and their ability to treat various diseases. With the availability of primary information, further studies can be carried out like phyto pharmacology of different extracts, standardization of the extracts, identification and isolation of active principles and pharmacological studies of isolated compound. These may be followed by development of lead molecules as well as it may serve for the purpose of use of specific extract in specific herbal formulation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: The authors would like to thank Bundelkhand Central Library and Department of Pharmacognosy, Bundelkhand University, Jhansi, India.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Nil

REFERENCES:1.

Ramakrishnan G and Hariprasad T: In-vitro antimicriobial activity of leaves and bark extracts of religiosa (Linn.); International Research Journal of Pharmacy 2012; 3(9): 178-179.

2. Roy K, Kumar S and Sarkar S; Wound healing potential of leaf extracts of religiosa on wistar albino strain rats; International Journal of Pharma Tech Research 2009; 1: 506-508.

3. Satyavati GV, Raina MK and Sharma M: Medicinal plants of India. Indian Council of Medicinal Research, New Delhi, Vol. I, 201-06.

4. Lewis WH and Elvin-Lewis MPH: Medicinal botany plants affecting Man’s health; John wiley and sons, New York; 1977.

5. Lakshmi Himabindu MR, Angala Paramoswari S and Gopinath C: Determination of flavonoid content of religiosa Linn. leaf extract by TLC and HPTLC; International Journal of Pharmacognosy and phytochemical Research 2013; 5(2): 120-127.

6. H, Amin Mat N, Bunwan NS, Baharum Nataqain S and Noor Mohd N: F. deltoidea Jack: A review on its phytochemical and pharmacological importance; Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2014; 1-9.

7. Chawla A, Kaur R and Sharma AK; carica Linn.: A review on its pharmacognostic, phytochemical and pharmacological aspects. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Phytopharmacological Research 2012; 1(14): 215-232.

8. Foye WO, Lemke TL and Williams DA: Foye’s principle of Medicinal chemistry, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Edition 6th, 2008: 44.

9. Gordon MC and David JN: Natural product drug discovery in the next millennium. Pharmaceutical Biology 2001; 39: 8-17.

10. Hamed MA: Beneficial effect of Ficus religiosa on high fat-induced hypercholesterolemia in rats; Food Chem 2011; 129: 162-170.

11. Salem MZM, Salem AZM, Camacho LM and Ali HM: Antimicrobial activities and phytochemical composition of extracts of Ficus species: An overview; African Journal of Microbiology Research 2013; 7(33): 4207-4219.

12. Singh D, Singh B and Goel RK: Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Ficus religiosa. J Ethnopharmacol 2011; 134: 565-583.

13. Trivedi P, Hinde S and Sharma RC: Preliminary phytochemical and pharmacological studies on racemosa. Journal of Medicinal Research 1969; 56: 1070-1074.

14. Sirisha N, Sreenivasulu M, Sangeeta K and Chetty CM: Antioxidant properties of Ficus species- A review; International J Pharma Tech Research 2010; 3: 2174-2182.

15. Joseph B and Raj SJ: Phytopharmacological and phytochemical properties of three Ficus species- An overview; International Journal of Pharma and Bioscience 2010; 1(4): 246-253.

16. Wong M: Ficus plants for Hawaii landscapes, ornamentals and flowers 2007; 34: 1-13.

17. Ghani A: Medicinal plants of Bangladesh with chemical constituents and uses; Asiatic society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, 1998, 236.

18. Singh D and Goel RK: J Ethnopharmacol 2009; 123: 330-334.

19. Prasad PV, Subhaktha PK, Narayan A and Rao MM: Bull Indian Inst Hist Med. Hyderabad 2006; 36: 1-20.

20. Anonymous Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India: New Delhi: Department of Ayush, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2001; 17-20.

21. Prasad PV, Subhakttha PK, Narayan A and Rao MM: Medico-historical study of “asvatha” (sacred fig tree). Bulletin of the Indian Institute of History of Medicine (Hyderabad) 2006; 36: 1-20.

22. Starr F, Starr K and Loope L: Ficus religiosa Bo tree Moraceae; Website:

http://www_hear.org/starr/hiplants/ reports/pdf/ficus_religiosa.pdf; 2003.

23. Shastri NK and Chaturvedi: Charak Samhita, vol.1, Varanasi: Chaukhambha Bharati Academy; Edition 6th, 1985: 5.

24. Kala CP: Prioritization of Medical plants based on available knowledge; Existing practices and use value status in Uttaranchal, Ethnobotany and Biodiversity Conservation 2004; 12: 453-459.

25. Yadav YC, Srivastava DN, Saini V and Sighal S: Experimental studies of Ficus religiosa (L) latex for preventive and curative effect against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in wistar rats. J Chem Pharma Res 2011; 3(1): 621-627.

26. Whittaker RH and Margulis L: Prolist classification and kingdoms of organisms. Biosystems 1978; 10(1- 2): 3-18.

27. the_tree.org.uk/sacredgrove/buddhism/#habitat.

28. Babu K, Shankar RG and Rai S: Turk J Bot 2010; 34: 215-224.

29. Brickell C and Zuk JD: The American Horticulture Society, A-Z, Encyclopedia of Garden Plants, New York, USA, 1997.

30. Shah SC and Quadry A: Textbook of Pharmacognosy, B.S. Prakashan, Ahmedabad, Edition 8th, 1991: 8.

31. Asolakar VL, Kakkar K K and Chakre JO: Glossary of Indian-Medical plants with active principles, Part I (A-K). Publication and Information directorate, C.S.I.R., New Delhi, 1992: 312-313.

32. Oliver Bever B: Oral hypoglycaemic plants in West Africa. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 1980; 2(2): 119-127.

33. Bushra S and Farooq A; Flavonols (Kaempeferol, quercetin, myricetin) contents of selected fruits, vegetables and medical plants. Food Chemistry 2008; 108(3): 879-884.

34. Panda SK, Panda NC and Sahue BK: Phytochemistry and pharmacological properties of Ficus religiosa: an overview. Indian Veterinary Journal 1976; 60: 660-664.

35. Verma RS and Bhatia KS: Chromatographic study of amino acids of the leaf protein concentrates of Ficus religiosa and Mimusops-Elengi Linn. The Indian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 1986; 23: 231-232.

36. Behari M, Rani K, Usha MT and Shimiazu N: Curr Agri 8, 1984; 73.

37. Gautam S, Meshram A, Bhagyawant SS and Srivastava N: Ficus religiosa – Potential role in pharmaceuticals. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2014; 5(5): 1616-1623.

38. Warrier PK: Indian medicinal plants- A compendium of 500 species; Orient Longman ltd., Chennai, Vol, III, 1996: 38-39.

39. Kapoor LD: Handbook of Ayurvedic Medicinal plants; CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1990; 149-150.

40. Kunwar RM and Bussmann WR: Lyonia. J Ecol Appl 2006; 11: 85-97.

41. Khanom F, Kayahara H and Tadasa K: Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2000; 64: 837-840.

42. Pandit R, Phadke A and Jagtap A: J Ethnopharmacol 2010; 128: 462-466.

43. Jung HW, Son HY, Min HCV, Kim YH and Park YK: Phytother Res 2008; 22: 1064-1068.

44. Viswanthan SP, Thirugnanasambantham M, Reddy KS, Narasimhan G and Subramaniam A; Anti-inflammatory and mast cell protective effect of religiosa. Ancient Science of Life 1990; 10: 122-125.

45. Joy PP, Thomas J, Mathew S and Skaria BP: Medicinal plants; Kerela Agricultural University, Kerela, India, 1998: 3-8.

46. Madhav CK, Sivaji K and Rao KT: Flowering plants of Chittor District, A.P., India, 2008; 330-333.

47. Sreelekshmi R, Latha PG, Arafat MM, Shyamal S, Shine VJ, Anuja GI, Suja SR and Rajasekharam S: Anti-inflammatory, analgesic and anti-lipid peroxidation studies on stem bark of religiosa Linn. Natural Product Radiance 2007; 6(5): 377-381.

48. Charde RM, Dhongade HJ, Charde MS and Kasture AV: Int J Pharma Sci Research 2010; 1(5): 73-82.

49. Gupta VK, Gupta M and Sharma SK: Evaluation of the antioxidant potential of religiosa (Linn.) roots against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 2011; 5(9): 1582-1588.

50. Krishanti MP, Rathinam X, Marimuthu K, Diwakar A, Ramanathan S, Kathiresan S and Subramaniam: A comparative study on the antioxidant activity of methanolic extracts of leaf of F. religiosa, Chromolaena odorata (L.); King and Robinson, Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. and Tridax procumbens L. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine 2010; 3(5): 348-350.

51. Irana H and Agarwal SS: Indian J Exp Bio 2009; 47: 822-826.

52. Singh D and Goel RK: Anticonvulsant effect of religiosa: role of serotonergic pathways. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2009; 123: 330-334.

53. Makhija IK, Sharma IP and Khamar D: Phytochemistry and pharmacological properties of Ficus religiosa: an overview. Scholars Research Library 2010; 1(4): 171-180.

54. Farrukh A and Ahmad J: J Microbiol 2003; 19: 653-657.

55. Iqbal Z, Nadeem QK, Khan MN, Akhtar MS and Waarich FN: Int J Agr Biol 2001; 3: 454-457.

56. Hemaiswarya S, Poonkotha M, Raja R and Anbazhagan C: Egyptian J Bio 2009; 11: 52-57.

57. Chaudhary GP: Evaluation of ethanolic extract of Ficus religiosa bark on incision and excision wounds in rats. Planta Indica 2006; 2(3): 17-19.

58. Kaur H, Singh D, Singh B and Goel RK: Anti amnesic effect of Ficus religiosa in scopolamine-induced anterograde and retrograde amnesia. Pharmaceutical Biology 2010; 48: 234-240.

59. Vintha B, Prashanth D, Salma K, Sreeja SL, Pratiti D, Padmaja R, Radhika S, Amit A, Venkateshwarlu K and Deepak M: J Ethnopharmacol 1968; 109: 1083-1088.

60. William DC: Proteolytic activity in the genus Ficus. Plant Physiology 1968; 43: 1083-1088.

61. Ahuja D, Bijjem KRV and Kalia AN: Bronchospasm potentiating the effect of methanolic extract of Ficus religiosa fruits in guinea pigs. J Ethnopharmacol 2011; 133(2): 324-328.

62. Malluwar VR and Pathak AK: Studies on immuno-modulatory activity of Ficus religiosa. Ind J Pharm Edu Res 2008; 42(4): 341-343.

63. Hemaiswarya S and Anbazhagan RR: Antimicrobial and antitumor properties of the leaves of Ficus religiosa. Plant Arch 2008; 8(1): 279-282.

64. Khan MSA, Hussain SA, Jais AMM, Zakaria ZA and Khan M: Antiulcer activity of Ficus religiosa stem bark ethanolic extract in rats. J Medicinal Plants Research 2011; 5(3): 354-359.

65. Swami KD and Bisht NPS: Constituents of Ficus religiosa and Ficus infectoria and their biological activity. J Ind Chem Soc 1996; 73(5): 631.

66. Akhtar MS, Iqbal Z, Khan MN and Lateef M: Antihelmintic activity of medicinal plants with particular reference to their use in animals in the indo-Pakistan subcontinent; Small Ruminant Research 2000; 38: 99-107.

67. Sawarkar HA, Singh MK, Pandey AK and Biswas D; In-vitro anthelmintic activity of Ficus bengalhensis, Ficus carica and Ficus religiosa: A comparative anthelmintic activity. International J Pharma Tech Research 2011; 3: 152-153.

How to cite this article:Singh S, Jain SK, Alok S, Chanchal D and Rashi S: A review on Ficus religiosa - An important medicinal plant. Int J Life Sci & Rev 2016; 2(1): 1-11. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.IJLSR.2(1).1-11.

All © 2015 are reserved by International Journal of Life Sciences and Review. This Journal licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.