Chapter 1: The Aryas and the Anaryas of Vedic India, Excerpt from The Indo-Aryan Races: A Study of The Origin of Indo-Aryan People and Institutions.by

Ramaprasad Chanda, B.A., Honorary Secretary, Varendra Research Society, Rajshahi

1916

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

CHAPTER I. The Aryas and the Anaryas of Vedic India. The dawn of history is heralded in India by the hymns sung by the Rsis and enshrined in the

Rgveda Samhita. These hymns reveal two hostile peoples in the Land of the Seven Rivers now called the Punjab — the deva-worshipping Arya and the deva-less and rite-less Dasyu or Dasa. The first problem that demands the attention of students of the anthropological history of India is, — who were these Dasyus or non-Aryas of Vedic India?

It is commonly assumed that in the four-fold division of castes (varna=colour) the aborigines, who submitted to, or were subdued by, the Aryan invaders, were represented by the Sudras. "It is reasonable to reckon the Sudra of the later texts as belonging to the aborigines who had been reduced to subjection by the Aryans."* [Macdonell and Keith's Vedic Index of Names and Subjects, London, 1912, Vol. II, p. 388.] But this view does not accord well with the data in hand.

[PAGES 2 and 3 MISSING] fourth order of the Vedic society, but to the fifth order, the Nisadas. In the Rgveda the term pancajanah and its synonyms occur very often. According to Yaska (III. 8) the term means, "Gandharvas, manes, gods, demons, and monsters according to some, and the four varnas with the NIsada as the fifth according to the Upamanyus." But in two other places (X. 3. 5, 7) Yaska himself explains panca-krsti of the Rgveda as "panca manusyajatani", 'five classes of men', which is explained by the scholiast as the four varnas with the Nisadas as the fifth. The author of the Brhad-devata attributes this interpretation to Sakatayana also (VII. 69). Nisadas are first named as such in the Rudradhyaya of the

Yajurveda together with the Vratas (nomads), Taksans (carpenters), Rathakaras (chariot-makers), Kulalas (potters), Karmaras (blacksmiths), Punjisthas (fowlers), Svanins (dog-keepers), and Mrgayus (hunters). The Mahabharata (XII. 59. 94-97) contains the following account of the origin of the Nisadas: —

"Vena, a slave of wrath and malice, became unrighteous in his conduct towards all creatures. The Rsis, those utterers of Brahma, slew him with kusa blades (as their weapon) inspired with mantras. Uttering mantras the while, those Rsis pierced the right thigh of Vena. Thereupon, from that thigh, came out a short-limbed person on earth, resembling a charred brand, with blood-red eyes and black hair. Those utterers of Brahma then said unto him,— Nisada, sit here. From him have sprung the Nisadas, viz. those wicked tribes that have the hills and the forests for their abode, as also those hundreds and thousands of others, called Mlecchas, residing on the Vindhya mountains."* [P. C. Ray's translation.]

The same story is repeated in many of the Puranas. In the Visnu Purana (I. 13) the Nisada is described as "of the complexion of a charred stake, with flattened feature and dwarfish stature." The Bhagavata Purana (IV. 14. 44) describes the Nisada as "black like crow, very low statured, short armed, having high cheek bones, low-topped nose, red eyes and copper-coloured hair."* [[Sanscrit]] In the Padma Purana (II. 27. 42—43) it is said, "His (Nisada's) descendants are settled in the hills and forests; the Nisadas, Kiratas, Bhillas, Nahalakas, Bhramaras, Pulindas, and other Mleccha tribes addicted to vices are all sprung from his body." These epic and Puranic legends evidently contain genuine traditions relating to the physical characters of the aborigines whom the Vedic Aryas met in the plains of Northern India. The Nisadas were too numerous to be annihilated and too powerful to be enslaved or expelled en masse. The Aryas were, therefore, compelled to meet them half way. In the Pancavimsa Brahmana (XVI. 6. 7) the performer of the Visvajit sacrifice is required "to live for three days among the Nisadas." In the Srauta Sutra of Katyayana (I. 12) and in the Mimamsa Sutra (VI. 1. 51-52) of Jaimini, Vedic texts are referred to that provided that Brahman priests should make chiefs who were Nisadas by descent offer certain sacrifices.

In the medieval Sanskrit literature, the barbarians of the Vindhya hills, belonging to the Nisada stock according to the Puranas, are called Sabaras, Pulindas, and Kiratas. Bana, who nourished in the first half of the seventh century A.D., thus describes a Savara youth in his Harsacarita: — "The young mountaineer (savara-yuva) had his hair tied into a crest above his forehead with a band of Syamalata creeper dark like lamp black, and his dark forehead was like a night that always accompanied him in his wild exploits . . . . . .; his ear had an ear-ring of grass-like crystal fastened in it, and assumed a green hue from a parrot's wing which ornamented it, his nose was flat, his lower lip thick, his chin low, his jaws full, his forehead and cheekbones projecting."* [Cowell and Thomas, Harsacarita (Eng translation), p. 230.] This agrees fully with the Puranic description of the Nisadas.

Nisada characteristics are still conspicuous in the Bhils and Gonds of the Vindhya regions. "The typical Bhil is small, dark, broad-nosed, and ugly, but well-built and active."* [Rajputana Gazetteer (Calcutta, 1908), p. 87.] "The Gonds are of small stature and dark in colour. Their bodies are well proportioned, but their features are ugly, with a round head, distended nostrils, a wide mouth and thick lips, straight and black hair, and scanty beard and moustache."* [Central Provinces Gazetteer (Calcutta, 1908), p. 163.] Dark skin, short stature and broad nose indicate the physical relationship of the Bhils and the Gonds with the old Nisadas on the one hand, and the hill tribes of Chota-Nagpur and Orissa and the Paniyans, the Kadirs, the Kurumbas, the Sholagas, the Irulas, the Mala Vedars and the Kanikars of Southern India, on the other. Sir Herbert Risley classifies these dark, short, and broad-nosed savage tribes of Central and Southern India together with the civilised speakers of Dravidian languages under the head Dravidian type. But the first thing that suggests itself at a glance at the summary of measurements of the castes and tribes of the so-called Dravidian type arranged in order of nasal index in Appendix IV p. cxiii of his work, The People of India (Calcutta, 1908), is that a line should be drawn between Parayan and Irula in this table. The average nasal indices will be found to vary from 69.1 to 80.0 above the line, whereas they vary from 80.9 to 95.1 below it. Mr. Thurston gives 84.1 as the average nasal index of the Irula of the Nilgiris. So if we exclude the Mukkuvan of Malabar, the Moormen of Ceylon and the Dom and Kurmi of Chota Nagpur and Bengal, we are left face to face with twenty-seven broad-nosed jungle tribes with average nasal indices above 84. We are, therefore, hardly justified in classifying these broad-nosed tribesmen with the upper group unless it is admitted that the nose-form of the latter has been modified by the influence of environment. Instances may be cited in which physical environment has produced no change in the shape of the nose. Three of the hill tribes of Southern India, the Toda, the Badaga, and the Kota, are medium-nosed like the civilised speakers of the Dravidian languages, the average nasal index of the Toda being 74.9, of the Badaga 75.6 and the Kota 77.2. The climate of the plains of the United Provinces has failed to modify the nose-form of the Pasi toddy-drawer (average nasal index 85.4), Chamar (86.0), Musahar (86.1) and other lower castes.* [The People of India, appendix iv, p. cxiv.]

In this connection greater weight should be attached to the views of two competent observers who have lived long among the population of Southern India. Mr. Thurston holds that the jungle tribes of Southern India "are the microscopic remnants of a pre-Dravidian people."* [Castes and Tribes of Southern India (Madras, 1904), Vol. I, p. iv.] Robert Sewell writes, "At some very remote period the aborigines of Southern India were overcome by hordes of Dravidian invaders and driven to the mountains and desert tracts, where their descendants are still to be found."* [The Indian Empire, Vol. II (Oxford, 1909), p. 32.] This dark, short and broad-nosed race is termed Pre-Dravidian by the Anthropologists. But since these physical features characterised the Puranic Nisadas and indicate the affinities of the Puranic Nisadas with the so-called Pre-Dravidian, so I should prefer to classify the dark, short-statured and broad-nosed jungle tribes as the modern Nisadas representing the old Nisada race. The modern Nisadas speak dialects belonging to three different linguistic families. The Bhils speak an Indo-Aryan language; the Gonds, the Khands, the Oraons and the jungle tribes of Southern India speak Dravidian languages; and the jungle tribes of Chota Nagpur and the Savaras and Juangs of Orissa speak languages of the Munda family. If our hypothesis relating to the Nisada race is correct, we must assume that Munda was originally spoken by the Nisada race as a whole, and Indo-Aryan and Dravidian dialects have been adopted by some of the Nisada tribes as a result of their contact with their more civilised neighbours.

The physical characters of the Nisadas indicate their affinities with the Veddas of Ceylon and the Sakais and Semangs of the Malay Peninsula Thurston writes in his introduction to Castes and Tribes of Southern India (p. 33): —

"Speaking of the Sakais, the same authorities [Skeat and Blagden] state that 'in evidence of their striking resemblance to the Veddas, it is worth remarking that one of the brothers, Sarasin, who had lived among the Veddas and knew them very well, when shown a photograph of a typical Sakai, at first supposed it to be a photograph of a Vedda. For myself, when I saw the photographs of Sakais published by Skeat and Blagden, it was difficult to realise that I was not looking at pictures of Kadirs, Paniyans, Kurumbas or other jungle folk of Southern India."

The linguistic researches of Schmidt and Sten Konow enable us to trace the affinities of the Nisadas over a still wider range. Pater Schmidt in his Die Mon-Khmer-Volker establishes the intimate relationship between the following groups of languages: — the Munda languages of India; Nikobar spoken in the Nikobar Islands; Khasi spoken in the Khasi hills of Assam; Palong, Wa, and Riang of Salwin basin, Upper Burma; Sakai and Semang languages of the Malay Peninsula; and the Mon-Khmer languages." Dr. Konow, working from the point of view of India proper, has been able to show not only that Munda languages are connected with Mon-Khmer, but that the former must once have extended much more widely over India than they do at the present day. There is a line of dialect of the lower Himalaya, stretching from Kunawar in the Punjab to near Darjeeling, — Tibeto-Burman in character, but nevertheless retaining many surviving traces of an old language of undoubted Munda character." Schmidt calls these allied groups of languages Austro-Asiatic and further postulates the existence of an Austro-Asiatic race characterised by long or medium head, horizontal non-oblique eyes, broad nostrils, dark skin, more or less wavy hair and short or medium stature. As regards the home of the Austro-Asiatic race, Schmidt thinks that the point from which the movement of these peoples began is to be found at the extreme western end of the region which they traversed.* [Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1907, pp. 187-191.]

The other division of the Rgvedic people — the Arya folk — did not constitute a homogeneous body. We discern two different social grades within its pale — the Rsi or priest-poet clans such as the Atharvans, Angirases, Bhrgus (Jamadagnis), Atris, Vasisthas, Bharadvajas, Gotamas, Kasyapas, Agastyas, Kanvas, and Visvamitras (Kusikas); and the other class included the warrior tribes such as the Yadus, Turvasas, Purus, Anus, Druhyus, Trtsus, Bharatas, Srnjayas, Rusamas, Matsyas, Cedis, Krivis and others. These two social grades did not form endogamous castes as yet; nor were the Rsi clans collectively known as Brahmans and the warrior tribes as Ksatriyas. But the former constituted a regular social order with a hereditary calling — that of officiating as sacrificial priests and hymn-making, though they did not eschew other occupations.

Scholars still differ as to whether the hymns of the Rgveda are mere appendages of the soma sacrifice or embody in many cases the sincere outpourings of poets only and not priests. It is not difficult to quote texts supporting either theory.

But no reader of the hymns can deny that in many of them sacrifice overshadows everything else. In the evolution of religion rites come first and hymns of praise after. Yajna or sacrificial rite without hymn was not unknown even in the Rgvedic age.

A Rsi prays in a hymn (X. 105.8), "With Rk verses we shall kill those who are without Rk verses. A sacrifice without hymn (abrahma yajna) cannot be pleasing to you." The soma sacrifice had grown so complicated even in what may be termed the early Rgvedic age that it required the services of seven Rtvijs or sacrificial priests (II. 1. 2). Daksina (sacrificial priest's fee) is deified and identified with Usas (Dawn) and in one verse (I. 126. 6) the giver of daksina is thus extolled: "All kinds (of objects) are intended for the givers of daksina; the Sun in heaven shines for the givers of daksina; the givers of daksina attain long life and immortality." The way in which daksina is spoken of in this and in the other hymns indicates that the giving of daksina, that is to say, the employment of sacrificial priests, was an essential part of a sacrificial ceremony in the Rgvedic age.ASTROLOGY AND DIVINATION.

LIKE most primitive people, the Tibetans believe that the planets and spiritual powers, good and bad, directly exercise a potent influence upon man's welfare and destiny, and that the portending machinations of these powers are only to be foreseen, discerned, and counteracted by the priests.

Such beliefs have been zealously fostered by the Lamas, who have led the laity to understand that it is necessary for each individual to have recourse to the astrologer-Lama or Tsi-pa on each of the three great epochs of life, to wit, birth, marriage, and death: and also at the beginning of each year to have a forecast of the year's ill-fortune and its remedies drawn out for them.

These remedies are all of the nature of rampant demonolatry for the appeasing or coercion of the demons of the air, the earth, the locality, house, the death-demon, etc.

Indeed, the Lamas are themselves the real supporters of the demonolatry. They prescribe it wholesale, and derive from it their chief means of livelihood at the expense of the laity...

The astrologer-Lamas have always a constant stream of persons coming to them for prescriptions as to what deities and demons require appeasing and the remedies necessary to neutralize these portending evils....

The days of the month in their numerical order are unlucky per se in this order. The first is unlucky for starting any undertaking, journey, etc. The second is very bad to travel. Third is good provided no bad combination otherwise. Fourth is bad for sickness and accident (Ch'u-'jag). Eighth bad. The dates counted on fingers, beginning from thumb and counting second in the hollow between thumb and index finger, the hollow always comes out bad, thus second, eighth, fourteenth, etc. Ninth is good for long journeys but not for short (Kut-da). Fourteenth and twenty-fourth are like fourth. The others are fairly good coeteris paribus. In accounts, etc., unlucky days are often omitted altogether and the dates counted by duplicating the preceding day...

The spirits of the seasons also powerfully influence the luckiness or unluckiness of the days. It is necessary to know which spirit has arrived at the particular place and time when an event has happened or an undertaking is entertained. And the very frequent and complicated migrations of these aerial spirits, good and bad, can only be ascertained by the Lamas...

A preliminary fee or present is usually given to the astrologer at the time of applying for the horoscope, in order to secure as favourable a presage as possible...

The Misfortune Account of the Family of __________ For the Earth-Mouse Year (i.e., 1888 A.D.)...

The extravagant amount of worship prescribed in the above horoscope is only a fair sample of the amount which the Lamas order one family to perform so as to neutralize the current year's demoniacal influences on account of the family inter-relations only. In addition to the worship herein prescribed there also needs to be done the special worship for each individual according to his or her own life's horoscope as taken at birth; and in the case of husband and wife, their additional burden of worship which accrues to their life horoscope on their marriage, due to the new set of conflicts introduced by the conjunction of their respective years and their noxious influences; and other rites should a death have happened either in their own family or even in the neighbourhood. And when, despite the execution of all this costly worship, sickness still happens, it necessitates the further employment of Lamas, and the recourse by the more wealthy to a devil-dancer or to a special additional horoscope by the Lama. So that one family alone is prescribed a sufficient number of sacerdotal tasks to engage a couple of Lamas fairly fully for several months of every year!

-- The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism With Its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in its Relation to Indian Buddhism, by Laurence Austine Waddell, M.B., F.L.S., F.R.G.S.

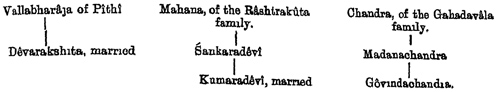

And that the office of the priest was in many cases hereditary is amply demonstrated by the hymns of what are called the family books of the Rgveda — the eight mandalas from the second to the ninth inclusive, attributed respectively to Grtsamada of the Bhrgu clan, Visvamitra, Vamadeva of the Gotama clan, Atri, Bharadvaja, Vasistha, Kanva, and Angiras and their descendants. Most of the hymns of the first book are attributed to poets of one or other of these clans or of other Rsi clans already mentioned. Of course there were exceptions. There is the case of Devapi officiating as the purohita (domestic priest) in the sacrifice of his brother Samtanu (X. 98). In the Rgveda itself Devapi is not stated to be a prince at all. He is called a Kuru prince by Yaska and Saunaka who flourished long after Samtanu' s sacrifice celebrated in the Rgveda. The story is thus told by Saunaka in his Brhad-devata (VII. 155-157; VIII. 1-6):—

"Now Devapi, son of Rstisena, and Samtanu of the race of Kuru were two brothers, princes among the Kurus.

"Now the elder of these two was Devapi, and the younger Samtanu; but the (former) prince, the son of Rstisena, was afflicted with skin-disease.

"When his father had gone to heaven, his subjects offered him the sovereignty. Reflecting for but a moment, he replied to his subjects:

"'I am not worthy of the sovereignty: let Samtanu be your king.' Assenting to this, his subjects anointed Samtanu king.

"When the scion of the Kuru had been anointed, Davapi retired to the forest. Thereupon Parjanya did not reign in (that) realm for twelve years.

"Samtanu accordingly came with his subjects to Devapi and propitiated him with regard to that dereliction of duty.

"Then in company with his subjects, he offered him the sovereignty. To him, as he stood humbly with folded hands, Devapi replied: —

"I am not worthy of the sovereignty, my energy being impaired by skin disease; I will myself officiate, O king, as your priest in a sacrifice for rain.'

"Then Samtanu appointed him to be his chaplain (puro' dhatta) and to act as priest (artvij- yaya). So he (Devapi) duly performed the rites productive of rain."* [Prof. Macdonell's translation.]

This story clearly indicates that the appointment of Devapi as priest was traditionally considered as something exceptional, and the exception proves the rule.

Not only was the office of the sacrificial priests hereditary in the Rgvedic age, but according to traditions preserved in the Taittiriya Samhita, certain functions of the office were hereditary in particular families. Thus in the Taittiriya Samhita (III. 5. 21) we are told: "The Rsis did not see Indra clearly, but Vasistha saw him clearly. Indra said, "I shall tell you a Brahmana, so that all men that are born will have thee for Purohita; but do not tell of me to the other Rsis.' Thus he told him these parts of the hymns; and ever since, men were born having Vasistha for their Purohita. Therefore Vasistha is to be chosen as Brahman priest and the (sacrificer) will have such offspring."* [[Sanskrit]] The same akhyayika

[PAGE 15 MISSING] "The Brahman (superintending priest) himself should perform them, and no other than the Brahman; for the Brahman sits on the right (south) side of the sacrifice, and protects the sacrifice on the right side ... Now as to the meaning of these (formulas) Vasistha "knew the Viraj; Indra coveted it. He spake, 'Rsi, thou knowest the Viraj; teach me it!' He replied, 'What would therefrom accrue to me?' 'I would teach the expiation for the whole sacrifice, I would show thee its form.' ... The Rsi then taught Indra that Viraj ... And Indra then taught the Rsi this expiation from the Agnihotra up to the Great Litany. And formerly, indeed, the Vasisthas alone knew these utterances, hence formerly one of the Vasistha family became Brahman; but since nowadays anybody (may) study them, anybody may now become Brahman. And, indeed, he who thus knows these utterances is worthy to become Brahman, or may reply, when addressed as 'Brahman.'"* [Eggeling's translation, Sacred Books of the East, Vol. xliv.]

Thus efficacious formulas or hymns were originally held as patents by the descendants of the author and thereby hereditability became an essential feature of Vedic sacerdotalism from the earliest times. We may, therefore, hold with Macdonell and Keith "that in the Rgveda this Brahmana, or Brahmin, is already a separate caste, differing from the warrior and agricultural for which divine origin is not claimed are the Visvamitras and the Kanvas, and there is clear traditional evidence to the effect that the founders of these two clans originally belonged to the yajamana class. The Kusikas or Visvamitras were evidently a branch of the Bharata tribe of the yajamana group. In the Aitareya Brahmana (VII. 17.6. 7) Visvamitra is addressed as rajaputra, 'prince,' and bharahi-rsabha, 'bull of the Bharatas.' In the Rgveda (X. 31. n) Nrsad is given as the name of Kanva's father. But according to the Puranas Kanva was originally a Ksatriya. Ajamida was a descendant of Puru, the eponymous ancestor of the Rgvedic Purus. ''From Ajamida was born Kanva, from Kanva Medhatithi, and from Medhatithi the Brahmans of the Kanva clan (kanvayanah) (Visnu P. IV. iq. 10)." "In one passage of the

Atharvaveda (II. 25) they (the Kanvas) seem to be definitely regarded with hostility."* [Vedic Index, I, p. 134.] Of these two groups of the Rsi clans — the one claiming divine origin and the other sprung from the yajamana class — the former formed the nucleus of the Rsi class and the latter were Rsi by adoption. According to the Rgveda the founders of the Atharvan, Angiras, Bhrgu, and Vasistha clans were the founders of the sacrificial cult and are required to be worshipped as pitrs, manes. In one hymn (X. 14) the Angirases, the Atharvans, and the Bhrgus are called "the soma-loving fathers" and "the makers of the path (pathakrdvyah)." In another hymn (X. 15. 8) the Vasisthas are classed in the same category. Atharvan is said to have extracted sacrificial fire by churning Puskara (VI. 16. 13). "A Rsi named Atharvan first propitiated the gods by sacrifice; the gods and the Bhrgus forced their way (to that place) and learnt the sacrifice (X. 92. 10)." "Like a friend Matarisvan (wind-god) brought this fire to the Bhrgus (I. 60. 1)." "The Ahgiras first prepared food for Indra, and worshipped him by offering oblations to the fire (1. 83. 4)." "Atharvan first discovered the path by sacrifice (I. 83. 5)." Similar traditions relating to Ahgiras, Atharvan and Bhrgu are also found in the Yajurveda. The only rational interpretation that these hoary traditions admit of is that in the early Vedic age three or four Rsi clans, — the Ahgirases, Atharvanas, Bhrgus, and Vasisthas — were regarded as the original Rsi clans among whom the Vedic sacrificial cult originated, and other clans became members of the sacerdotal class by adoption. This early Vedic sacerdotal class afterwards came to be known as Brahmans. In the Parisistabhaga of the Srauta Sutra of Asvalayana it is said, "Visvamitra, Jamadagni Bharadvaja, Gotama, Atri, Vasistha and Kasyapa are the seven Rsis; the descendants of the seven Rsis with Agastya as the eighth are called their gotras (clans)."* [[Sanscrit]] Of these eight founders of the Brahmanic gotras, Bharadvaja is said to have been the grandson of Angiras (Brhad-devata, V. 102); Gotama also belonged to the Angiras clan; and Jamadagni was the son of Bhrgu. A tradition to the effect that the Brahmanic gotras fall into two groups, one representing the original priesthood and the other consisting of priests by adoption, survived down to the time of the Mahabharata. Thus we are told in the Santiparvan (296. 17-18): "Originally only four gotras arose, O King, viz. Angiras, Kasyapa, Vasistha, and Bhrgu. In consequence of good deeds, O ruler of men, many other gotras came into existence in time. These gotras are named on account of the penances of those who have founded them. Good people use them."* [[Sanscrit]]

Vedic legends of the conflict between the Vasisthas and the Visvamitras indicate that the Rsis or priest-poets of the original gotras (mula-gotrani) did not recognise the claims of the aspiring members of the warrior tribes to Rsihood without hard struggle. Vasistha was the priest of Sudas, the king of the Trtsus and Bharatas. According to a hymn of the Rgveda, Sudas won a great victory over ten allied kings with the assistance of Vasistha (VII. 18). In the Aitareya-Brahmana we are told that Vasistha consecrated Sudas, son of Pijavana, to sovereignty. The story of the conflict between Sakti, son of Vasistha, and the Visvamitras as referred to in the Rgveda (III. 53) is thus narrated in the Brhaddevata (IV. 112-120): —

"At a great sacrifice of Sudas, by Sakti Gathi's son (Visvamitra) was forcibly deprived of consciousness. He sank down unconscious. But to him the Jamadagnis gave speech called Sasarpari, daughter of Brahma or of the Sun, having brought her from the dwelling of the Sun. Then that speech dispelled the Kusikas' loss of intelligence (a-matim). And in the (stanza) 'Hither, (upa: iii. 53. 11) Visvamitra restored the Kusikas to consciousness (anubodhayat). And gladdened at heart by receiving speech he paid homage to those seers (the Jamadagnis), himself praising speech with two stanzas 'Sasarpari' (Sasarparih: iii. 53, 15, 16). (With the stanzas) 'strong' (sthirau: iii. 53. 17-20) (he praised) the parts of the cart and the oxen as he started for home. And then going home he deposited (them there) in person (svasarirena). But the four stanzas which follow (iii. 53. 21-24) are traditionally held to be hostile to the Vasisthas. They were pronounced by Visvamitra, they are traditionally held to be 'imprecations' (abhisapa). They are pronounced to be hostile to enemies and magical (abhicarika) incantations. The Vasisthas will not listen to them. This is the unanimous opinion of their authorities (acaryaka): great guilt arises from repeating or listening (to them); by repeating or hearing (them) one's head is broken into a hundred fragments; the children of those (who do so) perish; therefore one should not repeat them."* [Macdonell's translation.]

The hymn (III. 53) read with this passage of the Brhaddevata seems to indicate that in a sacrifice, evidently

horse-sacrifice, performed by Sudas, Rsis of the Kusika family including Vismamitra were invited to take part. Sakti, son of Vasistha, the family priest of the king, resented this intrusion and made them unconscious by means of a charm. Visvamitra and his kinsmen were no match for Vasistha's son in the use of magical incantations. But the Jamadagnis, who like the Vasisthas, belonged to the older group of Rsi clans and were as skilful in magic, came to the rescue of the Kusikas. Visvamitra thanked the Jamadagnis, started for home in his bullock cart and uttered four imprecatory stanzas against the Vasisthas. Perhaps this led to a sanguinary conflict between Sudas and Vasistha which is thus referred to in the Taittiriya Samhita (VII. 4. 7, 1), "Vasistha, when his sons were killed, desired that he might beget children and humble the sons of Sudas. Then he saw this (sattra called) ekonapancasadratra, adopted it and performed it. Then he (Vasistha) obtained children and humbled the sons of Sudas."* [[Sanskrit]]

Some scholars do not admit that there is any reference to the strife of Visvamitra and Vasistha in the hymn. But in the absence of a more satisfactory explanation we have no other course to follow than to fall back upon the traditional explanation preserved by Saunaka and referred to by Katyayana in his Sarvanukramani. Yaska (II. 24) also states that "Visvamitra was the Purohita of Sudasa, son of Paijavana" in connection with Rgveda III. 33. The suggestion made by Macdonell and Keith* [Vedic Index, ii. 275-276.] that Visvamitra originally held the office of the Purohita of Sudas and was afterwards deposed by Vasistha does not accord with the statement of the Aitareya Brahmana that Vasistha consecrated Sudas to sovereignty and the statement of the Pancavimsa Brahmana (XV. 5. 24) that the Bharatas adopted Vasisthas as their domestic priests as soon as they came into being. The fact seems to have been that the Vasisthas were originally the Purohitas of the Trtsus and Bharatas and so of their king Sudas. In the time of Sudas there flourished a number of poets in the Kusika clan of the Bharata tribe including Visvamitra, who claimed the office of the Purohita of their tribal chief. This led to a quarrel with Sakti, the head of the Vasistha clan. Though Sudas was not loth to recognize their claims, it were the Saudasas (sons of Sudas) who espoused their cause with zeal and put to death their opponents.

The two sections of the sacerdotal class, Brahmans by descent and Brahmans by adoption, were of different physical types. In the Rgveda (VII. 33. 1) the Vasisthas, who represent the first group, are described as svityam, 'white', while Kanva (X. 31. 11), representing the second group, is Svava or krsna, 'dark.' In the Gopatha Brahmana (I. 1. 223) the Brahman's colour is white (Sukla). The tradition of the existence of a group of Brahmans with white complexion and yellow hair survived down to the time of the grammarian Patanjali (about 150 B.C.) who writes in his Mahabhasya (on Panini V. 1. 115): "Penance, knowledge of the Veda, and birth make a Brahman. He who is without penance and knowledge of the Veda is a Brahman by birth only. White complexion, pure conduct, yellow or red hair, etc. are also characteristics that constitute Brahmanhood."* [[Sanskrit]] The Brahman with white complexion and yellow hair seems so strange a being to Kaiyata, the scholiast of Patanjali, that he assigns him to a previous cycle of existence. He writes, "White complexion, etc., were seen in Brahmans who flourished in a previous cycle of existence and whose descendants are rarely met with even now.* [[Sanskrit]]

The second division of the Rgvedic Aryas, the Yadus (yadva jana), Purus, Druhyus, Anus, Turvasas, Bharatas (bharata jana) and other Yajamana tribes were traditionally akin to the dark section of the Rsis, the Kanvas and the Visvamitras. The Kathaka Samhita (XI. 6) calls the Vaisya 'white' (Sukla), the Rajanya 'swarthy' (dhumra).* [Vedic Index, Vol. II, p. 247, note 2.] To explain the difference of colour of skin and hair between the two groups of Vedic Aryas we have to assume that the ancestors of the "white and yellow-haired" group migrated to India from the temperate region in the far North, and the dark section had their home in the tropics. There is clear traditional evidence in the Rgveda to show that two at least of the tribes of the latter group, the Turvasas and the Yadus, came to India from South-Western Asia. We are told in one stanza (VI. 20. 12): "O hero (Indra)! when you crossed the sea (samudra), you brought Turvasa and Yadu over the sea." Another stanza (VI. 45. 1) tells us, "Indra, who brought Turvasa and Yadu from afar by his wise policy, is our youthful friend." In X. 62. 10 Yadu and Turva (Turvasa) are called Dasas or barbarians. According to some scholars samudra in the Rgveda does not mean sea, for the Aryas had not yet reached the sea, but only the lower course of the Indus. This interpretation of samudra may be traced to the preconceived notion that the Rgvedic Aryas were a homogeneous body of men who came from, the North-West. But once this notion is dismissed from the mind, there is left nothing to prevent us from accepting samudra in its usual sense. The sea that lies nearest to the country of the Rgvedic Aryas is the Arabian Sea. So if we are to attach any value to this Vedic tradition, we are forced to assume that the Yadus and the Turvasas came across the Arabian Sea. The evidences contained in the later Vedic and epic literatures relating to the Indian home of one of these two folks, the Yadus, lend support to this hypothesis.

It is generally assumed that the Yadus and Turvasas must have been settled somewhere in the Punjab in the Rgvedic age. In the list of tribes dwelling in the land of the Five Rivers and in the valleys of the Ganges and the Jumna as given in the later Vedic and early Buddhist literatures neither the Yadus nor the Turvasas find any mention. Where were they then? According to the Mahabharata and the Puranas the Satvatas or the Bhojas were a branch of the Yadus. Though the Yadus are not mentioned in the Bramhana texts, the Satvats and the Bhojas are. In the Satapatha Brahmana (XIII. 5. 4. 21) a verse is quoted wherein it is said that Bharata seized the sacrificial horse of the Satvats. In the Aitareya Brahmana (VIII. 14) it is said, "Therefore in that southern region all the Kings of the Satvats are consecrated for the enjoyment of pleasures and are called Bhojas." The country of the Satvats and Bhojas is called southern region from the view point of the land in the middle (asyam dhruvayam madhyamayam pratisthayam disi) or the midland where dwelt the Usinaras, the Kurus, the Pancalas and the Vasas.

The Harivamsa and the Puranas enable us to define the early Indian home of the Yadus in the south with greater precision. The Harivamsa or the supplementary book of the Mahabharata is the chief repository of legends and traditions relating to the Andhakas and the Vrsnis, the two chief branches of the Yadu stock. The Harivamsa in its present form may not be very old, but it must have existed in an embryonic stage even in the time of the grammarian Panini. Suffixes and accents are as a rule prescribed for names of persons according to the actual forms of the words denoting those names and not according to tribes or clans to which the persons named might belong. And yet this is what is done by Panini in two of his aphorisms (IV. 1. 115; VI. 2. 34.) In the former aphorism it is prescribed that the affix an denoting descendant is added to a word "denoting the name of a Rsi, or the name of a person belonging to the Andhaka, Vrsni or Kuru clans"; and the latter aphorism provides, — "The first part of a dvandva compound formed of names denoting Ksatriya clans in the plural number retains its original accent when the warrior belongs to the Andhaka or Vrsni clans." Panini could hardly have made such rules unless he had before him names of descendants of persons of the Andhaka and Vrsni clans of all possible forms formed by adding an and of dvandva compounds thus accented. And where could he get materials for such lists except in the narrative literature of his time? The Mahabharata, of which the Harivamsa forms an integral part, is named in the Grhya Sutra of Asvalayana and in Panini VI. 2.38 Panini very probably flourished in the fourth century B.C.,* [Vide Keith's Introduction to Aitareya Aranyaka (Oxford, 1909), p. 24.] when genuine traditions of the early Vedic age may be expected to still survive in the Vedic schools. So the legends and traditions relating to the Andhakas and the Vrsnis preserved in the Harivamsa may be considered as genuine traditions coming down from the Vedic age.

Two conflicting legends are given in the Harivamsa relating to the origin of the Yadus or Yadavas. In chapter 3 Yadu, the eponymous ancestor of the Yadavas, is represented as a son of King Yayati of the lunar race. But in chapter 94 it is said that Yadu belonged to the solar Iksvaku race. As the original Indian home of the Yadavas is very clearly indicated in this version of the legendary history of the Yadava clans and princes, I shall reproduce it in substance. There was a raja named Haryasva, the son of Iksvaku, in Manu's line. Madhumati, daughter of the demon Madhu, was Haryasva's wife. He was driven out of Ayodhya by his elder brother Madhava, and, at the instance of his wife, took shelter with his father-in-law at Madhupura, the chief town of Madhuvana. "In a short time his (Haryasva's) kingdom known as Anarta and Saurastra enriched by cattle, and also called Anupa adorned by the sea beach and forest, became very prosperous." By his queen Madhumati Haryasva had a son named Yadu, from whom sprung the Yadava clans, viz. Bhaima, Kakkura, Bhoja, Andhaka, Yadava, Dasarha and Vrsni. Yadu's son was Madhava; Madhava's son was Satvata; Satvata's son was Bhima. From Satvata one section of the Yadavas came to be known as Satvatas and from Bhima as Bhaimas. While Bhima was reigning over Surastra, Satrughna, half-brother of Rama, the hero of the Ramayana, killed Lavana, son of the demon Madhu, destroyed Madhuvana, and there founded a new city called Mathura. After the death of Satrughna, Andhaka, son of Bhima, succeeded him to the throne of Mathura.

These legends, by indicating that the Yadavas were originally settled in Saurastra or the Kathiwar peninsula and then spread to Mathura, lend indirect support to the Rgvedic tradition that the Yadus, together with the Turvasas, came from beyond the sea. There are strong evidences to show that in the sixteenth and the fifteenth centuries B.C., in Syria and Upper Mesopotamia, there were several colonies of men of Aryan speech, some of whom at least worshipped Vedic gods. In the cuneiform tablets discovered at Tell-el-Amarna in Upper Egypt containing letters from the tributary Kings of Western Asia to Egyptian Pharaohs, we find the servant of ( . . . . ).' The seal dates from about 2000 B.C., the period of the first dynasty of Babylon."* [Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. X (1914), p. 462.] As the find-place of the seal is unknown, it is difficult to base any conclusion upon it. But had not the seal with a golden handle been found in India, and presumably in Central India, it could hardly have found its way to the Nagpore Museum. The Aryas of the Rg vedic age were not unfamiliar with sea voyage. "There are references," observe Macdonell and Keith, "to the treasures of the ocean, perhaps pearls or the gains of trade, and the story of Bhujyu seems to allude to marine navigation."* [Vedic Index, Vol. II, p. 432.] There are references to sea voyage in the Brahmanas also indicating the maritime activity of the Aryas in the later Vedic age. In the Pancavimsa-Brahmana (XIV. 5. 17) it is said, "Those who go to the sea without boat (aplavah) do not come out of that."* [[Sanskrit]] Again in the Aitareya Brahmana (VI. 21) we are told, "Know that this tristup formula is the first among the hymns that I am to recite. Those who perform the annual satra or Dvadasaha are like men who wish to cross the sea. As men who desire to cross the sea get into boat full of provisions, so these performers of satra use tristup formula."* [[Sanskrit]] So we may assume a continuous maritime connection of

Aryavarta with Western Asia from the Rgvedic period till the time of the Baveru Jataka of the Pali canon.

The Arya immigrants from Mesopotamia must have absorbed a good deal of Semitic blood in their Syrian home and were probably dark like the Semites. The Purus, Druhyus and Anus, mentioned in the Rgveda along with the Yadusand Turvasas, may have come from the same quarters and were probably of the same physical type. The fair and fair-haired invaders who formed the nucleus of the Brahman caste came earlier direct from the cradle of the Aryan folk in the far north and elaborated the vedic sacrificial cult in their Indian home from the primitive worship of Indra, Varuna and the other gods of nature. They were probably akin to the Athravans and Magi of Ancient Iran, for the Iranians, like the Indo-Aryans, but unlike all other Indo-Germanic peoples, had, and the Parsis still have in their Dasturs, a hereditary priesthood. The ancestors of the Rsi clans probably came earlier. When later on the ancestors of the Rgvedic warrior tribes entered India and came in contact with the Rsi clans, the former recognized the cultural superiority of the latter and accepted them as their religious guides.

Fair and fair-haired Rsi clans from the north, dark or brown yajamana tribes from South-western Asia, and the very dark aboriginal Nisadas were the ethnic elements out of which grew up the five primary varnas or castes, viz. the Brahmans, Rajanyas (Ksatriyas), Vaisyas, Sudras, and . Now the question is, how did this transformation take place. The earliest account of the origin of varnas is found in the following stanzas of the Purusa hymn of the Rgveda (X. 90. 11-12): —

"When they divided the Purusa, into how many parts did they divide him? What was his mouth? What were his arms? What were his thighs and feet called?

"The Brahman was his mouth; of his arms, the Rajanya was made; the Vaisyas were his thighs; the Sudra sprang from his feet."

The Vedic theory of the origin of castes finds a clearer expression in a Yajus text (Taittiriya Samhita, VII. 1. I. 4-6) wherein we read: —

"Prajapati, desirous of offspring [performed the Agnistoma sacrifice] and created trivrt hymn, god Agni, Gayatri metre, Rathantara saman, Brahman among men and goats among brutes from his mouth. As they were created from the mouth, therefore they are superior to all others.

"[He] created Pancadasa hymn, god Indra, Tristup metre, Vrhat saman, Rajanya among men and sheep among brutes from his chest and arms. Therefore they are strong because they have been created from strength (strong arms). [He] created Saptadasa hymn, Visvadevas among the gods, Jagati metre, Vairupa Saman, Vaisya among men and the cows among brutes from the belly. As they have been created from the storehouse of food (belly), so they are the food (or intended to be enjoyed by others). Therefore they (Vaisyas) are more numerous than others (among men) because many gods were created.

"[He] created ekavimsa hymn, anustup metre, Vairaja Saman, Sudra among men and horse among brutes from his feet. Therefore the Sudra and the horse are dependent on other (castes). As no god was created from the feet, so the Sudra is not competent to perform sacrifice. As the Sudra and the horse were created from the feet, so they live by exerting their feet."* [[Sanskrit]]

Here the four varnas are recognized as separate creations of the creator, differing as widely as do goat, sheep, cow and horse; or in the language of natural history, the four varnas were considered as four different species of animals and not merely four different groups of the same species. The conception that the difference between the different groups of men is congenital and not artificial was founded on the fact that the earliest social groups known to the Aryas, — the priests, the yajamanas, and the godless aborigines actually differed from one another in colour (varna) and other prominent physical characters. This, "the sense of distinctions of race indicated by differences of colour," to use the language of Risley, is "the basis of fact" in the development of caste system. When the slaves came to be recognized as a separate group termed Sudra, and the tax-paying subject section of the yajamana tribes as a separate social group termed Vaisya, as distinguished from the ruling or Raj any a section, the conception of the identity of racial or colour difference and social difference was extended to them by fiction, and the Vaisyas and Sudras were recognized as separate varnas or colours. With these two elements, fact and fiction, was combined a third element, heredity of function, copied from the Rsi clans. Colour or race differences, real and fancied, together with hereditary function, gave birth to the caste system. But as newer groups formed or attached themselves to the Arya nations, the absurdity of regarding them all as distinct colours or varnas was recognized, and the theory of varna-sankara or mixed caste was started to explain their origins.