Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

National Indian Association

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/10/21

Journal of the National Indian Association in 1879

Should not be confused with the Indian National Association

The National Indian Association was formed in Bristol by Mary Carpenter.

The London branch was formed the following year. After the death of Mary Carpenter, Elizabeth Adelaide Manning (E. A. Manning) became secretary and the organisation moved to London where its activities became synonymous with Manning.

History

The National Indian Association in Aid of Social Progress in India was formed by Mary Carpenter in 1870 in Bristol.[1] Its first objective was to improve education for Indian women.[1] Carpenter had visited India in 1866 and she had written about her six months there. She was particularly concerned by the lack of female teachers to educate Hindu girls.[2] The London branch of the association was formed the following year by Charlotte Manning and her step daughter Elizabeth Adelaide Manning.[3] Cities in both the UK and India had local branches of the society.[1]

From 1874 to her death in 1878 Princess Alice was President of the association, she was also the first to subscribe to the Indian Girls' Scholarship Fund, a fund set up by the Association to grant annual scholarships for Indian girls in government inspected schools.[4]

In 1881 the society spawned an offshoot named the Northbrook Indian Society (NIA) after the Earl of Northbrook, ex-viceroy of India, who was the new society's Honorary President. The Northbrook society had been conceived two years before and in 1880 the new society was running a reading room stocked with both English and Indian newspapers. This society grew to also supply lodgings for visiting Indian students.[5] In 1882 the NIA launched Medical Women for India which was an initiative to train female doctors so that they could work on assisting women in India. The NIA also took an interest in students from India who were studying in Britain. E. A. Manning created a book of guidance called Handbook of information relating to university and professional studies etc. for Indian students in the United Kingdom. Manning's help was not just theoretical,[6] in 1888 Cornelia Sorabji wrote to the National Indian Association from India for assistance in completing her education. This was championed by Mary Hobhouse, and Manning contributed funds together with Florence Nightingale, Sir William Wedderburn and others. Sorabji arrived in England in 1889 and stayed with Manning and Hobhouse. Sorabji became the first woman to complete a law degree at Oxford and kept in contact with the NIA during her later career.[7]

In 1904 E. A. Manning was awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal by the King for services to the British Raj.[8] She died the following year and Emma Josephine Beck was appointed as the new secretary. Beck was at an NIA event in 1909 where William Hutt Curzon Wyllie was assassinated by Madan Lal Dhingra.[9]

In 1910 the society was at 21 Cromwell Street in South Kensington where it shared premises with the Northbrook Society and the Bureau for Information for Indian Students.[5]

The association went into a decline in the 1920s but it did not formally end operations until 1966. The organisation had merged with the East India Association after India left the British Empire and it eventually became part of the Royal Society for India, Pakistan and Ceylon.[1]

References

1. National Indian Association, Open University, Retrieved 27 July 2015

2. Carpenter, Mary. Six Months in India. London, Longmans, Green and Co, 1868, 141-148

3. Elizabeth Adelaide Manning, Open University, Retrieved 25 July 2015

4. E. A. MANNING. "Women In India." Times [London, England] 21 Dec. 1878: 6. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 26 July 2015.

5. Northbrook Society, Open University, Retrieved 27 July 2015

6. Gillian Sutherland, ‘Manning, (Elizabeth) Adelaide (1828–1905)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2007 accessed 26 July 2015

7. Mary Hobhouse, Open University, Retrieved 26 July 2015

8. Great Britain. India Office (1819). The India List and India Office List for ... Harrison and Sons. p. 172.

9. EJ Beck, Open University, Retrieved 27 July 2015

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/10/21

This was possibly the lowest ebb in Vinayak’s life, with both his personal and professional lives in the doldrums. But being committed to the revolutionary cause, he was prepared to face such seemingly insurmountable challenges. He shifted out of India House temporarily to deflect the attention the place was gathering in the press. On 3 April, he moved to Bipin Chandra Pal’s residence at 140, Sinclair Road.

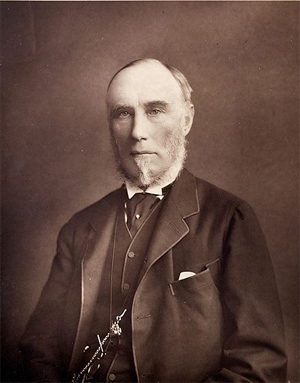

One of the key influencers of the Gray’s Inn decision with regard to Vinayak’s admission was Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie (1848–1909). He was a British Indian Army officer who rose to the position of a lieutenant colonel. He had served as the British resident to Nepal and one of the princely states of Rajputana. On his return to Britain, he was appointed aide-de-camp to the Secretary of State for India, Lord George Hamilton. One of his main tasks was the control of high-ranking Indian visitors to Britain and the continent who were suspected of seditious activities. This included native Indian princes such as Gaekwad, the Maharaja of Baroda. 79 He kept a close watch on their movements, the contacts they made while in Europe and the level of official recognition that they were awarded by continental governments. 80 Wyllie also made personal contacts with several Indian students, on occasion inviting them home for a drink or dinner and craftily extracting information from them, all the while behaving as their well-wisher. If any of this information merited attention, he passed it on to his superiors.81

In late April 1909, Curzon Wyllie had personally written to the benchers of Gray’s Inn dissuading them from calling both Vinayak and Harnam Singh to the Bar. Through May 1909, he wrote several letters and supplied a plethora of information to Gray’s Inn about Vinayak’s ‘undesirable’ activities, terming him a particularly dangerous and seditious force. While Harnam Singh was called to the Bar, it charged Vinayak with ‘condoning assassination, inciting revolution and advocating against the nation’. 82 It is said that Curzon Wyllie even travelled to France to gather information about Vinayak and his associates at India House. He spearheaded a few unsuccessful attempts to establish a boarding house for Indian students sponsored by the India Office. He believed that this master stroke of his would help strip away the uniqueness of India House, wean away new recruits for Vinayak and also help foster loyalty towards the British government in the minds of young students.

The anger and resentment among several Indian students in London had reached its zenith and was all set to explode. It was merely a matter of time. On the evening of 1 July 1909, at about 8 p.m., a young, handsome Indian student left his room on the first floor of a lodging house on 106 Ledbury Road in the Bayswater neighbourhood of London. The National Indian Association (NIA) was holding one of its routine parties to encourage interaction between the British and Indians in London. It was being held at Jehangir Hall in the Imperial Institute at South Kensington. Miss Beck, the honorary secretary of the NIA, greeted him at around half past nine. She had met him a few months back and inquired how his studies were progressing. To this he replied that he had finished his course at the University College and would take up the examination for qualifying as an Associate Member of the Institute of Civil Engineers (AMICE) later in October before heading back home to India. Since he knew quite a few people at the party he told Miss Beck that he would keep himself busy socializing with them. 83 The young man walked around confidently, waiting for the opportune moment. At around 11 p.m. William Curzon Wyllie, the honorary treasurer of the NIA, made his entry into Jehangir Hall. He exchanged pleasantries with a few Indian students and stopped by to have a longer conversation with the young man. Suddenly, the young man fished out a small Colt pistol and fired four shots at pointblank range, right into Curzon Wyllie’s eyes. 84 Wyllie collapsed to the ground and died instantly. Cawas Lalcaca, a forty-six-year-old Parsi doctor from Shanghai, who rushed to Curzon Wyllie’s aid upon hearing the first shot was also inadvertently hit and lay writhing in pain on the ground. He eventually succumbed to his injuries.

Douglas William Thorburn, a journalist of the National Liberal Club, and several others rushed towards the young man, leapt on him and grabbed him tightly, pinning him to chair, to prevent further harm. In the process, his large gold-rimmed glasses fell. The young man placed the revolver to his own temple and was going to kill himself, but he had used all the bullets. People jostled and struggled to get the pistol off him. In the scuffle, one of the guests, Sir Leslie Probyn, fell and injured his nose and ribs. Thorburn asked him why he had committed such a ghastly act. The young man looked at him sternly and stoically responded, ‘Wait, let me just put my spectacles on!’ 85 He seemed unruffled and calm.

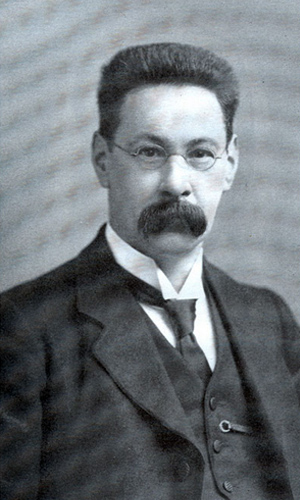

The Evening Telegraph described this trait of his in its report of him: ‘. . . not only being an expert revolver shot, but was the calmest man in the room after the tragedy, coolly inquiring if he might have his glasses’. 86 A fellow Indian, Madan Mohan Sinha, who was at the party, questioned him in Hindustani but the young man remained silent. The former wondered if the young man was under the influence of intoxicants as he appeared in a half-dazed and dreamy condition. Captain Charles Rolleston who held the young man tightly asked him repeatedly what his name was. Finally, he shouted: ‘Madan Lal Dhingra.’

-- Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past: 1883-1924, by Vikram Sampath

Journal of the National Indian Association in 1879

Should not be confused with the Indian National Association

The National Indian Association was formed in Bristol by Mary Carpenter.

Mary Carpenter (3 April 1807 – 14 June 1877) was an English educational and social reformer. The daughter of a Unitarian minister, she founded a ragged school and reformatories, bringing previously unavailable educational opportunities to poor children and young offenders in Bristol.

She published articles and books on her work and her lobbying was instrumental in the passage of several educational acts in the mid-nineteenth century. She was the first woman to have a paper published by the Statistical Society of London. She addressed many conferences and meetings and became known as one of the foremost public speakers of her time. Carpenter was active in the anti-slavery movement; she also visited India, visiting schools and prisons and working to improve female education, establish reformatory schools and improve prison conditions. In later years she visited Europe and America, carrying on her campaigns of penal and educational reform.

Carpenter publicly supported women's suffrage in her later years and also campaigned for female access to higher education. She is buried in Arnos Vale Cemetery in Bristol and has a memorial in the North transept of Bristol Cathedral...

In 1833 she met Ram Mohan Roy, a founder of the Brahmo Samaj movement which reformed social Hinduism, and was influenced by his philosophy during his short stay with Miss Castle and Miss Kiddel at Beech House in Stapleton before Roy died of meningitis in September of that year. Later that year she also met Joseph Tuckerman, an American Unitarian who had founded the Ministry-at-Large to the Poor in Boston, Massachusetts. He is said to have directly inspired her start on the path of social reform, partly by a chance remark made when walking with Carpenter through a slum district of Bristol. A small boy in rags ran across their path and Tuckerman remarked, "That child should be followed to his home and seen after." He had established a Farm School in Massachusetts, which became the model for later reformatories. Carpenter's later writings are based upon ideas she developed from her correspondence with Tuckerman...

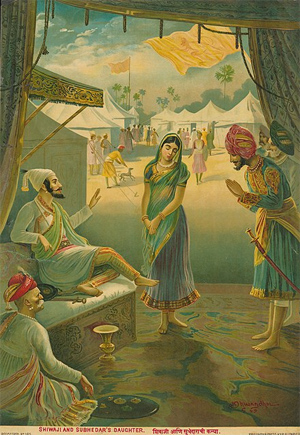

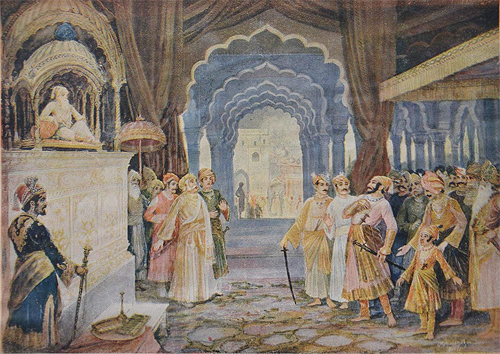

In 1866 Carpenter visited India, which had been an ambition of hers since her meeting with Raja Ram Mohan Roy in 1833. She visited Calcutta, Madras and Bombay, finding that for the most part girls were not educated past the age of twelve years, mainly due to a lack of educated female teachers. During her visit Carpenter met Keshab Chandra Sen, the leader of Brahmo Samaj. Sen asked her to form an organisation in Britain to improve communication between British and Indian reformers, which she did in 1870, establishing the National Indian Association. She visited many schools, hospitals and gaols and encouraged both Indian and British colonial administrators to improve and fund these. She was particularly concerned that the lack of good female education led to a shortage of women teachers, nurses and prison attendants. The Mary Carpenter Hall at the Brahmo Girls school in Calcutta was erected as a memorial to this work.

She also participated in the inauguration of the Bengal Social Science Association, and addressed a paper to the governor-general on proposals for female education, reformatory schools and improving the conditions of gaols. She returned to India in 1868 and achieved funding to set up a Normal School to educate female Indian teachers. In 1875 she made a final visit and was able to see many of her schemes in operation. She also presented proposals for Indian prison reform to the Secretary of the Indian Government.

-- Mary Carpenter, by Wikipedia

The London branch was formed the following year. After the death of Mary Carpenter, Elizabeth Adelaide Manning (E. A. Manning) became secretary and the organisation moved to London where its activities became synonymous with Manning.

Elizabeth Adelaide Manning (1828 – 10 August 1905) was a British writer and editor. She championed kindergartens. She was one of the first students to attend Girton College. Manning was active for the National Indian Association which championed education and the needs of women in India....

In February 1871, Manning and her stepmother [Charlotte Manning (nee Solly)] started the London branch of the National Indian Association. Her stepmother died the following month and Manning increasingly became the society's main proponent. She edited its magazine, whose title shifted from The Journal of the National Indian Association to The Indian Magazine in 1886, and then in 1891 The Indian Magazine and Review, still under Manning's leadership.

In 1882, the NIA launched Medical Women for India, an initiative to train women doctors so that they could work in part on caring for women in India. (See Zenana missions.) The NIA also took an interest in students from India who were studying in Britain. Manning created a book of guidance called Handbook of information relating to university and professional studies etc. for Indian students in the United Kingdom. Manning had an open house policy and she cared particularly for students from India...

In July 1904, Manning was awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal, first class, by the King for services to the British Raj.The Kaisar-i-Hind Medal for Public Service in India was a medal awarded by the Emperor/Empress of India between 1900 and 1947, to "any person without distinction of race, occupation, position, or sex ... who shall have distinguished himself (or herself) by important and useful service in the advancement of the public interest in India."...

The name "Kaisar-i-Hind" literally means "Emperor of India" in the Hindustani language. The word kaisar, meaning "emperor" is a derivative of the Roman imperial title Caesar, via Persian (see Qaysar-i Rum) from Greek Καίσαρ Kaísar, and is cognate with the German title Kaiser, which was borrowed from Latin at an earlier date. Based upon this, the title Kaisar-i-Hind was coined in 1876 by the orientalist G.W. Leitner as the official imperial title for the British monarch in India. The last ruler to bear it was George VI.[4]

Kaisar-i-Hind was also inscribed on the obverse side of the India General Service Medal (1909), as well as on the Indian Meritorious Service Medal.

-- Kaisar-i-Hind Medal, by Wikipedia

Manning left bequests to the NIA, The Froebel Society, the Royal Free Hospital and Charles Voysey's unorthodox church in Piccadilly.

-- Adelaide Manning, by Wikipedia

History

The National Indian Association in Aid of Social Progress in India was formed by Mary Carpenter in 1870 in Bristol.[1] Its first objective was to improve education for Indian women.[1] Carpenter had visited India in 1866 and she had written about her six months there. She was particularly concerned by the lack of female teachers to educate Hindu girls.[2] The London branch of the association was formed the following year by Charlotte Manning and her step daughter Elizabeth Adelaide Manning.[3] Cities in both the UK and India had local branches of the society.[1]

From 1874 to her death in 1878 Princess Alice was President of the association, she was also the first to subscribe to the Indian Girls' Scholarship Fund, a fund set up by the Association to grant annual scholarships for Indian girls in government inspected schools.[4]

Princess Alice Maud Mary of the United Kingdom VA CI (25 April 1843 – 14 December 1878) was the Grand Duchess of Hesse and by Rhine from 1877 to 1878. She was the third child and second daughter of Queen Victoria and Albert, Prince Consort. Alice was the first of Queen Victoria's nine children to die, and one of three to be outlived by their mother, who died in 1901. Her life had been enwrapped in tragedy since her father's death in 1861.

Alice spent her early childhood in the company of her parents and siblings, travelling between the British royal residences. Her education was devised by Albert's close friend and adviser, Baron Stockmar, and included practical activities such as needlework and woodwork and languages such as French and German. When her father, Prince Albert, became fatally ill in December 1861, Alice nursed him until his death. Following his death, Queen Victoria entered a period of intense mourning and Alice spent the next six months acting as her mother's unofficial secretary. On 1 July 1862, while the court was still at the height of mourning, Alice married the minor German Prince Louis of Hesse, heir to the Grand Duchy of Hesse. The ceremony—conducted privately and with unrelieved gloom at Osborne House—was described by the Queen as "more of a funeral than a wedding". The Princess's life in Darmstadt was unhappy as a result of impoverishment, family tragedy and worsening relations with her husband and mother.

Alice showed an interest in nursing, especially the work of Florence Nightingale. When Hesse became involved in the Austro-Prussian War, Darmstadt filled with the injured; the heavily pregnant Alice devoted a lot of her time to the management of field hospitals. One of her organisations, the Princess Alice Women's Guild, took over much of the day-to-day running of the state's military hospitals. As a result of this activity, Queen Victoria became concerned about Alice's directness about medical and, in particular, gynaecological, matters. In 1871, she wrote to Alice's younger sister, Princess Louise, who had recently married: "Don't let Alice pump you. Be very silent and cautious about your 'interior'". In 1877, Alice became Grand Duchess upon the accession of her husband, her increased duties putting further strains on her health. In late 1878, diphtheria infected the Hessian court. Alice nursed her family for over a month before falling ill herself, dying later that year.

Princess Alice was the sister of Edward VII of the United Kingdom and Empress Victoria of Germany (wife of Frederick III), mother of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia (wife of Nicholas II), maternal grandmother of Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (the last Viceroy of India), and maternal great-grandmother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (consort of Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom). Another daughter, Elisabeth, who married Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia, was, like Alexandra and her family, killed by the Bolsheviks in 1918.

-- Princess Alice of the United Kingdom, by Wikipedia

In 1881 the society spawned an offshoot named the Northbrook Indian Society (NIA) after the Earl of Northbrook, ex-viceroy of India, who was the new society's Honorary President. The Northbrook society had been conceived two years before and in 1880 the new society was running a reading room stocked with both English and Indian newspapers. This society grew to also supply lodgings for visiting Indian students.[5] In 1882 the NIA launched Medical Women for India which was an initiative to train female doctors so that they could work on assisting women in India. The NIA also took an interest in students from India who were studying in Britain. E. A. Manning created a book of guidance called Handbook of information relating to university and professional studies etc. for Indian students in the United Kingdom. Manning's help was not just theoretical,[6] in 1888 Cornelia Sorabji wrote to the National Indian Association from India for assistance in completing her education. This was championed by Mary Hobhouse, and Manning contributed funds together with Florence Nightingale, Sir William Wedderburn and others. Sorabji arrived in England in 1889 and stayed with Manning and Hobhouse. Sorabji became the first woman to complete a law degree at Oxford and kept in contact with the NIA during her later career.[7]

In 1904 E. A. Manning was awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal by the King for services to the British Raj.[8] She died the following year and Emma Josephine Beck was appointed as the new secretary. Beck was at an NIA event in 1909 where William Hutt Curzon Wyllie was assassinated by Madan Lal Dhingra.[9]

In 1910 the society was at 21 Cromwell Street in South Kensington where it shared premises with the Northbrook Society and the Bureau for Information for Indian Students.[5]

The association went into a decline in the 1920s but it did not formally end operations until 1966. The organisation had merged with the East India Association after India left the British Empire and it eventually became part of the Royal Society for India, Pakistan and Ceylon.[1]

References

1. National Indian Association, Open University, Retrieved 27 July 2015

2. Carpenter, Mary. Six Months in India. London, Longmans, Green and Co, 1868, 141-148

3. Elizabeth Adelaide Manning, Open University, Retrieved 25 July 2015

4. E. A. MANNING. "Women In India." Times [London, England] 21 Dec. 1878: 6. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 26 July 2015.

5. Northbrook Society, Open University, Retrieved 27 July 2015

6. Gillian Sutherland, ‘Manning, (Elizabeth) Adelaide (1828–1905)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2007 accessed 26 July 2015

7. Mary Hobhouse, Open University, Retrieved 26 July 2015

8. Great Britain. India Office (1819). The India List and India Office List for ... Harrison and Sons. p. 172.

9. EJ Beck, Open University, Retrieved 27 July 2015