by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/8/21

Malabar rites is a conventional term for certain customs or practices of the natives of South India, which the Jesuit missionaries allowed their Indian neophytes to retain after conversion but which were afterwards prohibited by Rome.

They are not to be confused with the liturgical rite of the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church (a variant of the East Syriac Rite), for which see Syro-Malabar rite.

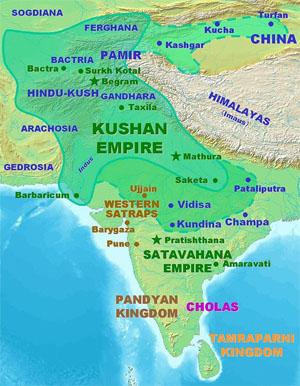

The missions concerned are not those of the coast of southwestern India, to which the name Malabar coast properly belongs, but rather those of nearby inner South India, especially those of the former Hindu "kingdoms" of Madurai, Mysore and the Carnatic.

Origins

The question of Malabar Rites originated in the method followed by the Jesuit mission, since the beginning of the seventeenth century, in evangelizing those countries. The prominent feature of that method was an accommodation to the manners and customs of the people to be converted. Enemies of the Jesuits claim that, in Madura, Mysore and the Karnatic, the Jesuits either accepted for themselves or permitted to their neophytes such practices as they knew to be idolatrous or superstitious. Others reject the claim as unjust and absurd and say that the claim is tantamount to asserting that these men, whose intelligence, at least, was never questioned, were so stupid as to jeopardize their own salvation to save others and to endure infinite hardships to establish among the Hindus a corrupt and sham Christianity.

The popes, while disapproving of some usages hitherto considered inoffensive or tolerable by the missionaries, never charged them with having knowingly adulterated the purity of religion. One of them, who had observed the "Malabar Rites" for seventeen years previous to his martyrdom, was conferred by the Church the honour of beatification. The process for the beatification of Father John de Britto was going on at Rome during the hottest period of the controversy over these "Rites", and the adversaries of the Jesuits asserted that beatification to be impossible because it would amount to approving the "superstitions and idolatries" maintained by the missioners of Madura. Still, the cause progressed, and Benedict XIV, on 2 July 1741, declared "that the rites in question had not been used, as among the Gentiles, with religious significance, but merely as civil observances, and that therefore they were no obstacle to bringing forward the process".[1] The mere enumeration of the Decrees by which the question was decided shows how perplexing it was and how difficult the solution. It was concluded that there was no reason to view the "Malabar rites", as practised generally in those missions, in any other light and that the good faith of the missionaries in tolerating the native customs should not be contested; but on the other hand, they erred in carrying this toleration too far.

Father de Nobili's work

The founder of the missions of the interior of South India, Roberto de Nobili, was born in Rome, in 1577, of a noble family from Montepulciano, which numbered among many distinguished relatives the celebrated Cardinal Roberto Bellarmine. When nineteen years of age, he entered the Society of Jesus. After a few years, he requested his superiors to send him to the missions of India. He embarked at Lisbon, 1604, and in 1606 was serving his apostolic apprenticeship in South India, where Christianity was then flourishing on the coasts. It is well known that St Francis Xavier baptized many thousands there, and from the apex of the Indian triangle the faith spread along both sides, especially on the west, the Malabar coast. But the interior of the vast peninsula remained almost untouched. The Apostle of the Indies himself recognized the insuperable opposition of the "Brahmins and other noble castes inhabiting the interior" to the preaching of the Gospel.[2] Yet his disciples were not sparing of endeavours. A Portuguese Jesuit, Gonsalvo Fernandes, had resided in the city of Madura fully fourteen years, having obtained leave of the king to stay there to watch over the spiritual needs of a few Christians from the coast; and, though a zealous and pious missionary, he had not succeeded, within that long space of time, in making one convert. This painful state of things Nobili witnessed in 1606, when together with his superior, the Provincial of Malabar, he paid a visit to Fernandes. At once his keen eye perceived the cause and the remedy.

It was evident that a deep-rooted aversion to the foreign preachers hindered the Hindus of the interior, not only from accepting the Gospel, but even from listening to its message. The aversion was not to the foreigner, but the Prangui. This name, with which the natives of India designed the Portuguese, conveyed to their minds the idea of an infamous and abject class of men, with whom no Hindu could have any intercourse without degrading himself to the lowest ranks of the population. Now the Prangui were abominated because they violated the most respected customs of India, by eating beef, and indulging in wine and spirits; but much as all well-bred Hindus abhorred those things, they felt more disgusted at seeing the Portuguese, irrespective of any distinction of caste, treat freely with the lowest classes, such as the pariahs, who in the eyes of their countrymen of the higher castes, are nothing better than the vilest animals. Accordingly, since Fernandes was known to be a Portuguese, that is a Prangui, and besides was seen living habitually with the men of the lowest caste, the religion he preached, no less than himself, had to share the contempt and execration attending his neophytes, and made no progress whatever among the better classes. To become acceptable to all, Christianity must be presented to all, Christianity must be presented in quite another way. While Nobili thought over his plan, probably the example just set by his countryman Matteo Ricci, in China, stood before his mind. At all events, he started from the same principle, resolving to become, after the motto of St Paul, all things to all men, and a Hindu to the Hindus, as far as might be lawful.

Having ripened his design by thorough meditation and by conferring with his superiors, the Archbishop of Cranganore and the provincial of Malabar, who both approved and encouraged his resolution, Nobili began his career by re-entering Madura in the dress of the saniassy (Hindu ascetics). He never tried to make believe that he was a native of India; else he would have deserved the name of impostor; with which he has sometimes been unjustedly branded; but he availed himself of the fact that he was not a Portuguese, to deprecate the opprobrious name Prangui.

He moved from the missionary compound into a hut in the Brahman quarter of the city and shaved his head except for a small tuft of hair. He spoke only Tamil, hired a Brahman cook and houseboy, and became a vegetarian. Like all Brahmans, Roberto limited himself to one meal a day. He abandoned the black cassock and leather sandals of the Jesuits for a saffron robe and wooden clogs. To cover the "nakedness" of his forehead, he put sandalwood paste on his brow to indicate that he was a guru or teacher. He referred to himself not as a priest but as a sannyasi. Eventually, he ate only with Brahmans, and for a brief period he also wore the Brahman thread of three strands of cotton cord draped from the shoulder to the waist as a sign of rank. He bathed daily and cleansed himself ceremonially before saying mass.

-- Roberto de Nobili: Case study in cross-cultural accommodation, by Howard Culbertson

With the changing social pressures of Buddhism, the communal boundaries that the Vedics had created to prevent racial mixing had also weakened, and the number of inter-caste relationships increased. Even Sanskrit, the secret language of the Vedics, the code of their scriptures and their tool of self-empowerment and superiority, was usurped by indigenous groups. This is evident in the hybridization of languages, where the indigenous cultures fused Sanskrit words and sounds with those of their own language.

These transgressions must have infuriated the priest clans, who felt their artificially propped up racial and spiritual superiority weakening. Their response was to tighten the grip of the caste system, and intensify the laws against intermarriage. The need for purity and protection of caste and lineage was emphasized and Brahmin sanctity was urgently buttressed. People were warned that the punishment for threatening or striking a priest, even with a blade of grass, was they they would be born to evil for twenty-one birth cycles and would have other people eat them in the nether world.

The vulnerable position of the low slave caste in particular was reinforced through intimidation, that is, with more stringent rules and punishments, all in the name of sacred laws. A Shudra pretending to be a Brahmin would have his eyes gouged out; for approaching a Brahmin's kitchen, he would have his tongue rooted out; for claiming to know the Vedas better than a Brahmin, he would have boiling oil poured into his mouth and ears; for daring to sit on the seat of an upper caste, he would have his buttocks chopped off; and for verbally abusing a Brahmin, he would get the death sentence.

In the light of increasing inter-caste liaisons, punishments were intensified for sexual violations of the caste hierarchy. Breaking the laws of caste boundaries was declared anti-religion or 'irreligion'. Mixing bloodlines, it was said, would destroy the foundation of both the social and the divine order. The most abhorred alliance was that of a Brahmin woman with a slave man. They would be discarded as outcastes, and their children too would be assigned to the lowest and most despised subdivision of outcastes, 'the fierce untouchables.' The outcastes were driven out of towns and villages and compelled to live on the outskirts of society. They were to wander constantly since they had no right to a piece of land, even to build a home on. They were also to work in cremation grounds to burn dead bodies, and they had to act as the kingdom's executioners, two jobs which generally nobody wanted to do. Since they could not buy things from the town markets they had to make do with clothes they could scavenge from the unclaimed corpses they burned. They also had to be for their food and eat in broken dishes. There were even stipulations on which animals they could domesticate; the cow being sacred was, of course, taboo to them, their choices being limited to the dog and the donkey, animals that were generally despised as being filthy.

-- Sex and Power, by Rita Banerji

As long as caste is mentioned in government forms, a non Brahmin cannot become a Brahmin and vice versa. No never in the present caste system. Caste is determined even in the womb.

Can a non-Brahmin become a Brahmin?, by http://www.quora.com

The Brahmens among the Hindus have acquired and maintained an authority, more exalted, more commanding, and extensive, than the priests have been able to engross among any other portion of mankind. As great a distance as there is between the Brahmen and the Divinity, so great a distance is there between the Brahmen and the rest of his species. According to the sacred books of the Hindus, the Brahmen proceeded from the mouth of the Creator, which is the seat of wisdom; the Cshatriya proceeded from his arm; the Vaisya from his thigh, and the Sudra from his foot; therefore is the Brahmen infinitely superior in worth and dignity to all other human beings. The Brahmen is declared to be the Lord of all the classes. He alone, to a great degree, engrosses the regard and favour of the Deity; and it is through him, and at his intercession, that blessings are bestowed upon the rest of mankind. The sacred books are exclusively his; the highest of the other classes are barely tolerated to read the word of God; he alone is worthy to expound it. The first among the duties of the civil magistrate, supreme or subordinate, is to honour the Brahmens. The slightest disrespect to one of this sacred order is the most atrocious of crimes. “For contumelious language to a Brahmen,” says the law of Menu, “a Sudra must have an iron style, ten fingers long, thrust red hot into his mouth; and for offering to give instruction to priests, hot oil must be poured into his mouth and ears.” “If,” says Halhed's code of Gentoo laws, “a Sooder sits upon the carpet of a Brahmen, in that case the magistrate, having thrust a hot iron into his buttock, and branded him, shall banish him the kingdom; or else he shall cut off his buttock.” The following precept refers even to the most exalted classes: “For striking a Brahmen even with a blade of grass, or overpowering him in argument, the offender must soothe him by falling prostrate.” Mysterious and awful powers are ascribed to this wonderful being. “A priest, who well knows the law, needs not complain to the king of any grievous injury; since, even by his own power, he may chastise those who injure him: His own power is mightier than the royal power; by his own might therefore may a Brahmen coerce his foes. He may use without hesitation the powerful charms revealed to Atharvan and Angiras; for speech is the weapon of a Brahmen: with that he may destroy his oppressors.” “Let not the king, although in the greatest distress, provoke Brahmens to anger; for they, once enraged, could immediately destroy him with his troops, elephants, horses, and cars. Who without perishing could provoke those holy men, by whom the all-devouring flame was created, the sea with waters not drinkable, and the moon with its wane and increase? What prince could gain wealth by oppressing those, who, if angry, could frame other worlds and regents of worlds, could give being to other gods and mortals? What man, desirous of life, would injure those, by the aid of whom worlds and gods perpetually subsist; those who are rich in the knowledge of the Veda? A Brahmen, whether learned or ignorant, is a powerful Divinity; even as fire is a powerful Divinity, whether consecrated or popular. Thus, though Brahmens employ themselves in all sorts of mean occupations, they must invariably be honoured; for they are something transcendently divine.” Not only is this extraordinary respect and pre-eminence awarded to the Brahmens; they are allowed the most striking advantages over all other members of the social body, in almost every thing which regards the social state. In the scale of punishments for crimes, the penalty of the Brahmen, in almost all cases, is infinitely milder than that of the inferior castes. Although punishment is remarkably cruel and sanguinary for the other classes of the Hindus, neither the life nor even the property of a Brahmen can be brought into danger by the most atrocious offences. “Neither shall the king,” says one of the ordinances of Menu, “slay a Brahmen, though convicted of all possible crimes: Let him banish the offender from his realm, but with all his property secure, and his body unhurt.” In regulating the interest of money, the rate which may be taken from the Brahmens is less than what may be exacted from the other classes. This privileged order enjoy the advantage of being entirely exempt from taxes: “A king, even though dying with want, must not receive any tax from a Brahmen learned in the Vedas.” Their influence over the government is only bounded by their desires, since they have impressed the belief that all laws which a Hindu is bound to respect are contained in the sacred books; that it is lawful for them alone to interpret those books; that it is incumbent on the king to employ them as his chief counsellors and ministers, and to be governed by their advice. “Whatever order,” says the code of Hindu laws, “the Brahmens shall issue conformably to the Shaster, the magistrate shall take his measures accordingly.” These prerogatives and privileges, important and extraordinary as they may seem, afford, however, but an imperfect idea of the influence of the Brahmens in the intercourse of Hindu Society. As the greater part of life among the Hindus is engrossed by the performance of an infinite and burdensome ritual, which extends to almost every hour of the day, and every function of nature and society, the Brahmens, who are the sole judges and directors in these complicated and endless duties, are rendered the uncontrolable masters of human life. Thus elevated in power and privileges, the ceremonial of society is no less remarkably in their favour. They are so much superior to the king, that the meanest Brahmen would account himself polluted by eating with him, and death itself would appear to him less dreadful than the degradation of permitting his daughter to unite herself in marriage with his sovereign. With these advantages it would be extraordinary had the Brahmens neglected themselves in so important a circumstance as the command of property. It is an essential part of the religion of the Hindus, to confer gifts upon the Brahmens. This is a precept more frequently repeated than any other in the sacred books. Gifts to the Brahmens form always an important and essential part of expiation and sacrifice. When treasure is found, which, from the general practice of concealment, and the state of society, must have been a frequent event, the Brahmen may retain whatever his good fortune places in his hands; another man must surrender it to the king, who is bound to deliver one-half to the Brahmens. Another source of revenue at first view appears but ill assorted with the dignity and high rank of the Brahmens; by their influence it was converted into a fund, not only respectable but venerable, not merely useful but opulent. The noviciates to the sacerdotal office are commanded to find their subsistence by begging, and even to carry part of their earnings to their spiritual master. Begging is no inconsiderable source of priestly power...

To all but the Brahmens, the caste of Cshatriyas are an object of unbounded respect. They are as much elevated above the classes below them, as the Brahmens stand exalted above the rest of human kind. Nor is superiority of rank among the Hindus an unavailing ceremony. The most important advantages are attached to it. The distance between the different orders of men is immense and degrading. If a man of a superior class accuses a man of an inferior class, and his accusation proves to be unjust, he escapes not with impunity; but if a man of an inferior class accuses a man of a superior class, and fails in proving his accusation, a double punishment is allotted him. For all assaults, the penalty rises in proportion as the party offending is low, the party complaining high, in the order of the castes. It is, indeed, a general and a remarkable part of the jurisprudence of this singular people, that all crimes are more severely punished in the subordinate classes; the penalty ascending, by gradation, from the gentle correction of the venerable Brahmen to the harsh and sanguinary chastisement of the degraded Sudra. Even in such an affair as the interest of money on loan, where the Brahmen pays two per cent., three per cent. is exacted from the Cshatriya, four per cent. from the Vaisya, and five per cent. from the Sudra. The sovereign dignity, which usually follows the power of the sword, was originally appropriated to the military class, though in this particular it would appear that irregularity was pretty early introduced. To bear arms is the peculiar duty of the Cshatriya caste, and their maintenance is derived from the provision made by the sovereign for his soldiers...

As much as the Brahmen is an object of intense veneration, so much is the Sudra an object of contempt, and even of abhorrence, to the other classes of his countrymen. The business of the Sudras is servile labour, and their degradation inhuman. Not only is the most abject and grovelling submission imposed upon them as a religious duty, but they are driven from their just and equal share in all the advantages of the social institution. The crimes which they commit against others are more severely punished, than those of any other delinquents, while the crimes which others commit against them are more gently punished than those against any other sufferers. Even their persons and labour are not free. “A man of the servile caste, whether bought or unbought, a Brahmen may compel to perform servile duty; because such a man was created by the Self-existent for the purpose of serving Brahmens.” The law scarcely permits them to own property; for it is declared that “no collection of wealth must be made by a Sudra, even though he has power, since a servile man, who has amassed riches, gives pain even to Brahmens.” “A Brahmen may seize without hesitation the goods of his Sudra slave; for as that slave can have no property, his master may take his goods.” Any failure in the respect exacted of the Sudra towards the superior classes is avenged by the most dreadful punishments. Adultery with a woman of a higher caste is expiated by burning to death on a bed of iron. The degradation of the wretched Sudra extends not only to every thing in this life, but even to sacred instruction and his chance of favour with the superior powers. A Brahmen must never read the Veda in the presence of Sudras. “Let not a Brahmen,” says the law of Menu, “give advice to a Sudra; nor what remains from his table; nor clarified butter, of which part has been offered; nor let him give spiritual counsel to such a man, nor inform him of the legal expiation for his sin: surely he who declares the law to a servile man, and he who instructs him in the mode of expiating sin, sinks with that very man into the hell named Asamvrita.”...

At the head of this government stands the king, on whom the great lords of the empire immediately depend...A Brahmen ought always to be his prime minister. “To one learned Brahmen, distinguished among the rest, let the king impart his momentous counsel.”...

The Brahmens enjoy the undisputed prerogative of interpreting the divine oracles; for though it is allowed to the two classes next in degree to give advice to the king in the administration of justice, they must in no case presume to depart from the sense of the law which it has pleased the Brahmens to impose. The power of legislation, therefore, exclusively belongs to the priesthood. The exclusive right of interpreting the laws necessarily confers upon them, in the same unlimited manner, the judicial powers of government. The king, though ostensibly supreme judge, is commanded always to employ Brahmens as counsellors and assistants in the administration of justice; and whatever construction they put upon the law, to that his sentence must conform. Whenever the king in person discharges not the office of judge, it is a Brahmen, if possible, who must occupy his place. The king, therefore, is so far from possessing the judicial power, that he is rather the executive officer by whom the decisions of the Brahmens are carried into effect.

They who possess the power of making and interpreting the laws by which another person is bound to act, are by necessary consequence the masters of his actions. Possessing the legislative and judicative powers, the Brahmens were, also, masters of the executive power, to any extent, whatsoever, to which they wished to enjoy it. With influence over it they were not contented. They secured to themselves a direct, and no contemptible share of its immediate functions. On all occasions, the king was bound to employ Brahmens, as his counsellors and ministers; and, of course, to be governed by their judgment. “Let the king, having risen early,” says the law, “respectfully attend to Brahmens learned in the three Vedas, and by their decision let him abide.” It thus appears that, according to the original laws of the Hindus, the king was little more than an instrument in the hands of the Brahmens. He performed the laborious part of government, and sustained the responsibility, while they chiefly possessed the power...

The sacred character of the Brahmen, whose life it is the most dreadful of crimes either directly or indirectly to shorten, suggested to him a process for the recovery of debts, the most singular and extravagant that ever was found among men. He proceeds to the door of the person whom he means to coerce, or wherever else he can most conveniently intercept him, with poison or a poignard in his hand. If the person should attempt to pass, or make his escape, the Brahmen is prepared instantly to destroy himself. The prisoner is therefore bound in the strongest chains; for the blood of the self-murdered Brahmen would be charged upon his head, and no punishment could expiate his crime. The Brahmen setting himself down, (the action is called sitting in dherna) fasts; and the victim of his arrest, for whom it would be impious to eat, while a member of the sacred class is fasting at his door, must follow his example. It is now, however, not a mere contest between the resolution or strength of the parties; for if the obstinacy of the prisoner should exhaust the Brahmen, and occasion his death, he is answerable for that most atrocious of crimes—the murder of a priest; he becomes execrable to his countrymen; the horrors of remorse never fail to pursue him; he is shut out from the benefits of society, and life itself is a calamity. As the Brahmen who avails himself of this expedient is bound for his honour to persevere, he seldom fails to succeed, because the danger of pushing the experiment too far is, to his antagonist, tremendous. Nor is it in his own concerns alone that the Brahmen may turn to account the sacredness of his person: he may hire himself to enforce in the same manner the claims of any other man; and not claims of debt merely; he may employ this barbarous expedient in any suit. What is still more extraordinary, even after legal process, even when the magistrate has pronounced a decision against him, and in favour of the person upon whom his claim is made, he may still sit in dherna, and by this dreadful mode of appeal make good his demand...

“The property of a Brahmen shall never be taken as an escheat by the king; this is a fixed law; but the wealth of the other classes, on failure of all heirs, the king may take.”...

“If a man strikes a Bramin with his hand, the magistrate shall cut off that man's hand; if he strikes him with his foot, the magistrate shall cut off the foot; in the same manner, with whatever limb he strikes a Bramin, that limb shall be cut off; but if a Sooder strikes either of the three casts, Bramin, Chehteree, or Bice, with his hand or foot, the magistrate shall cut off such hand or foot.” “If a man has put out both the eyes of any person, the magistrate shall deprive that man of both his eyes, and condemn him to perpetual imprisonment, and fine him.” The punishment of murder is founded entirely upon the same principle. “If a man,” says the Gentoo code, “deprives another of life, the magistrate shall deprive that person of life.” “A once-born man, who insults the twice-born with gross invectives, ought to have his tongue slit. If he mention their names and classes with contumely, as if he say, ‘Oh thou refuse of Brahmens,’ an iron style, ten fingers long, shall be thrust red-hot into his mouth. Should he through pride give instruction to priests concerning their duty, let the king order some hot oil to be dropped into his mouth and his ear.”...

Among the Hindus, whatever be the crime committed, if it is by a Brahmen, the punishment is in general comparatively slight; if by a man of the military class, it is more severe; if by a man of the mercantile and agricultural class, it is still increased; if by a Sudra, it is violent and cruel. For defamation of a Brahmen, a man of the same class must be fined 12 panas; a man of the military class, 100; a merchant, 150 or 200; but a mechanic or servile man is whipped...

For perjury, it is only in favor of the Brahmen, that any distinction seems to be admitted. “Let a just prince,” says the ordinance of Menu, “banish men of the three lower classes, if they give false evidence, having first levied the fine; but a Brahmen let him only banish.” The punishment of adultery, which on the Brahmens is light, descends with intolerable weight on the lowest classes. In regard to the inferior cases of theft, for which a fine only is the punishment, we meet with a curious exception, the degree of punishment ascending with the class. “The fine of a Sudra for theft, shall be eight fold; that of a Vaisya, sixteen fold; that of a Cshatriya, two and thirty fold; that of a Brahmen, four and sixty fold, or a hundred fold complete, or even twice four and sixty fold.” No corporal punishment, much less death, can be inflicted on the Brahmen for any crime. “Menu, son of the Self-existent, has named ten places of punishment, which are appropriated to the three lower classes; the part of generation, the belly, the tongue, the two hands; and fifthly, the two feet, the eye, the nose, both ears, the property; and in a capital case, the whole body; but a Brahmen must depart from the realm unhurt in any one of them.”

-- The History of British India, vol. 1 of 6, by James Mill

He introduced himself as a Roman raja (prince), desirous of living at Madura in practising penance, in praying and studying the sacred law. He carefully avoided meeting with Father Fernandes and took his lodging in a solitary abode in the Brahmins' quarter obtained from the benevolence of a high officer. At first he called himself a raja, but soon he changed this title for that of brahmin (Hindu priest), better suited to his aims: the rajas and other kshatryas, the second of the three high castes, formed the military class; but intellectual avocations were almost monopolized by the Brahmins. They held from time immemorial the spiritual if not the political government of the nation, and were the arbiters of what the others ought to believe, to revere, and to adore. Yet they were in no wise a priestly caste; they were possessed of no exclusive right to perform functions of a religious nature. Nobili remained for a long time shut up in his dwelling, after the custom of Indian penitents, living on rice, milk, and herbs with water. Once a day he received attendance but only from Brahmin servants. Curiosity could not fail to be raised, and all the more as the foreign saniassy was very slow in satisfying it. When, after two or three refusals, he admitted visitors, the interview was conducted according to the strictest rules of Hindu etiquette. Nobili charmed his audience by the perfection with which he spoke their own language, Tamil; by the quotations of famous Indian authors with which he interspersed his discourse, and above all, by the fragments of native poetry which he recited or even sang with exquisite skill.

Having thus won a benevolent hearing, he proceeded step by step on his missionary task, labouring first to set right the ideas of his auditors with respect to natural truth concerning God, the soul, etc., and then instilling by degrees the dogmas of the Christian faith. He took advantage also of his acquaintance with the books revered by the Hindus as sacred and divine. These he contrived, the first of all Europeans, to read and study in the Sanskrit originals. For this purpose he had engaged a reputed Brahmin teacher, with whose assistance and by the industry of his own keen intellect and felicitous memory he gained such a knowledge of this recondite literature as to strike the native doctors with amazement, very few of them feeling themselves capable of vying with him on the point. In this way also he was enabled to find in the Vedas many truths which he used in testimony of the doctrine he preached. By this method, and no less by the prestige of his pure and austere life, the missionary had soon dispelled the distrust. Before the end of 1608, he conferred baptism on several persons conspicuous for nobility and learning. While he obliged his neophytes to reject all practices involving superstition or savouring in any wise of idolatrous worship, he allowed them to keep their national customs, in as far as these contained nothing wrong and referred to merely political or civil usages. Accordingly, Nobili's disciples continued for example, wearing the dress proper to each one's caste; the Brahmins retaining their codhumbi (tuft of hair) and cord (cotton string slung over the left shoulder); all adorning as before, their foreheads with sandalwood paste, etc. yet, one condition was laid on them, namely, that the cord and sandal, if once taken with any superstitious ceremony, be removed and replaced by others with a special benediction, the formula of which had been sent to Nobili by the Archbishop of Cranganore.

While the missionary was winning more and more esteem, not only for himself, but also for the Gospel, even among those who did not receive it, the fanatical ministers and votaries of the national gods, whom he was going to supplant, could not watch his progress quietly. By their assaults, indeed, his work was almost unceasingly impeded, and barely escaped ruin on several occasions; but he held his ground in spite of calumny, imprisonment, menaces of death and all kinds of ill-treatment. In April, 1609, the flock which he had gathered around him was too numerous for his chapel and required a church; and the labour of the ministry had become so crushing that he entreated the provincial to send him a companion. At that point a storm fell on him from an unexpected place. Fernandes, the missioner already mentioned, may have felt no mean jealousy, when seeing Nobili succeed so happily where he had been so powerless; but certainly he proved unable to understand or to appreciate the method of his colleague; probably, also, as he had lived perforce apart from the circles among which the latter was working, he was never well informed of his doings. However, that may be, Fernandes directed to the superiors of the Jesuits in India and at Rome a lengthy report, in which he charged Nobili with simulation, in declining the name of Prangui; with connivance at idolatry, in allowing his neophytes to observe heathen customs, such as wearing the insignia of castes; lastly, with schismatical proceeding, in dividing the Christians into separate congregations. This denunciation at first caused an impression highly unfavourable to Nobili. Influenced by the account of Fernandes, the provincial of Malabar (Father Laerzio, who had always countenanced Nobili, had then left that office), the Visitor of the India Missions and even the General of the Society at Rome sent severe warnings to the missionary innovator. Cardinal Bellarmine, in 1612, wrote to his relative, expressing the grief he felt on hearing of his unwise conduct.

Things changed as soon as Nobili, being informed of the accusation, could answer it on every point. By oral explanations, in the assemblies of missionaries and theologians at Cochin and at Goa, and by an elaborate memoir, which he sent to Rome, he justified the manner in which he had presented himself to the Brahmins of Madura. He then showed that the national customs he allowed his converts to keep were such as had no religious meaning. The latter point, the crux of the question, he elucidated by numerous quotations from the authoritative Sanskrit law-books of the Hindus. Moreover, he procured affidavits of one hundred and eight Brahmins, from among the most learned in Madura, all endorsing his interpretation of the native practices. He acknowledged that the infidels used to associate those practices with superstitious ceremonies; but, he observed,

"these ceremonies belong to the mode, not to the substance of the practices; the same difficulty may be raised about eating, drinking, marriage, etc., for the heathens mix their ceremonies with all their actions. It suffices to do away with the superstitious ceremonies, as the Christians do".

As to schism, he denied having caused any such thing:

"he had founded a new Christianity, which never could have been brought together with the older: the separation of the churches had been approved by the Archbishop of Cranganore; and it precluded neither unity of faith nor Christian charity, for his neophytes used to greet kindly those of F. Fernandes. Even on the coast there are different churches for different castes, and in Europe the places in the churches are not common for all."

Nobili's apology was effectually seconded by the Archbishop of Cranganore, who, as he had encouraged the first steps of the missionary, continued to stand firmly by his side, and pleaded his cause warmly at Goa before the archbishop, as well as at Rome. Thus the learned and zealous primate of India, Alexis de Menezes, though a synod held by him had prohibited the Brahmin cord, was won over to the cause of Nobili. His successor, Christopher de Sa, remained almost the only opponent in India.

At Rome the explanations of Nobili, of the Archbishop of Cranganore, and of the chief Inquisitor of Goa brought about a similar effect. In 1614 and 1615 Cardinal Bellarmine and the General of the Jesuit Society wrote again to the missionary, declaring themselves fully satisfied. At last, after the usual examination by the Holy See, on 31 January 1623, Gregory XV, by his Apostolic Letter "Romanae Sedis Antistes", decided the question provisionally in favour of Father de Nobili. Accordingly, the codhumbi, the cord, the sandal, and the baths were permitted to the Indian Christians, "until the Holy See provide otherwise"; only certain conditions are prescribed, in order that all superstitious admixture and all occasion of scandal may be averted. As to the separation of the castes, the pope confines himself to "earnestly entreating and beseeching (etiam atque etiam obtestamur et obsecramus) the nobles not to despise the lower people, especially in the churches, by hearing the Divine word and receiving the sacraments apart from them. Indeed, a strict order to this effect would have been tantamount to sentencing the new-born Christianity of Madura to death. The pope understood, no doubt, that the customs connected with the distinction of castes, being so deeply rooted in the ideas and habits of all Hindus, did not admit an abrupt suppression, even among the Christians. They were to be dealt with by the Church, as had been slavery, serfdom, and the like institutions of past times. The Church never attacked directly those inveterate customs; but she inculcated meekness, humility, charity, love of the Saviour who suffered and gave His life for all, and by this method slavery, serfdom, and other social abuses were slowly eradicated.

While imitating this wise indulgence to the feebleness of new converts, Father de Nobili took much care to inspire his disciples with the feelings becoming true Christians towards their humbler brethren. At the very outset of his preaching, he insisted on making all understand that

"religion was by no means dependent on caste; indeed it must be one for all, the true God being one for all; although [he added] unity of religion destroys not the civil distinction of the castes nor the lawful privileges of the nobles".

Explaining then the commandment of charity, he inculcated that it extended to the pariahs as well as others, and he exempted nobody from the duties it imposes; but he might rightly tell his neophytes that, for example, visiting pariahs or other of low caste at their houses, treating them familiarly, even kneeling or sitting by them in the church, concerned perfection rather than the precept of charity, and that accordingly such actions could be omitted without any fault, at least where they involved so grave a detriment as degradation from the higher caste. Of this principle the missionaries had a right to make use for themselves. Indeed, charity required more from the pastors of souls than from others; yet not in such a way that they should endanger the salvation of the many to relieve the needs of the few. Therefore, Nobili, at the beginning of his apostolate, avoided all public intercourse with the lower castes; but he failed not to minister secretly even to pariahs. In the year 1638, there were at Tiruchirapalli (Trichinopoly) several hundred Christian pariahs, who had been secretly taught and baptized by the companions of Nobili. About this time he devised a means of assisting more directly the lower castes, without ruining the work begun among the higher.

Besides the Brahmin saniassy, there was another grade of Hindu ascetics, called pandaram, enjoying less consideration than the Brahmins, but who were allowed to deal publicly with all castes. They were not excluded from relations with the higher castes. On the advice of Nobili, the superiors of the mission with the Archbishop of Cranganore resolved that henceforward there should be two classes of missionaries, the Brahmin and the pandaram. Father Balthasar da Costa was the first, in 1540, who took the name and habit of pandaram, under which he effected a large number of conversions, of others as well as of pariahs. Nobili had then three Jesuit companions. After the comforting decision of Rome, he had hastened to extend his preaching beyond the town of Madura, and the Gospel spread by degrees over the whole interior of South India. In 1646, exhausted by forty-two years of toiling and suffering, he was constrained to retire, first to Jafnapatam in Ceylon, then to Mylapore, where he died 16 January 1656. He left his mission in full progress. To give some idea of its development, note that the superiors, writing to the General of the Society, about the middle and during the second half of the seventeenth century, record an annual average of five thousand conversions, the number never being less than three thousand a year even when the missioners' work was most hindered by persecution. At the end of the seventeenth century, the total number of Christians in the mission, founded by Nobili and still named Madura mission, though embracing, besides Madura, Mysore, Marava, Tanjore, Gingi, etc., is described as exceeding 150,000. Yet the number of the missionaries never went beyond seven, assisted however by many native catechists.

The Madura mission belonged to the Portuguese assistance of the Society of Jesus, but it was supplied with men from all provinces of the Order. Thus, for example, Father Beschi (c. 1710–1746), who won respect from the Hindus, heathen and Christian, for his writings in Tamil, was an Italian, as the founder of the mission had been. In the last quarter of the seventeenth century, the French Father John Venantius Bouchet worked for twelve years in Madura, chiefly at Trichinopoly, during which time he baptized about 20,000 infidels. The catechumens, in these parts of India, were admitted to baptism only after a long and a careful preparation. Indeed, the missionary accounts of the time bear frequent witness to the very commendable qualities of these Christians, their fervent piety, their steadfastness in the sufferings they often had to endure for religion's sake, their charity towards their brethren, even of lowest castes, their zeal for the conversion of pagans. In the year 1700 Father Bouchet, with a few other French Jesuits, opened a new mission in the Karnatic, north of the River Kaveri. Like their Portuguese colleagues of Madura, the French missionaries of the Karnatic were very successful, in spite of repeated and almost continual persecutions by the idolaters. Moreover, several of them became particularly conspicuous for the extensive knowledge they acquired of the literature and sciences of ancient India. From Father Coeurdoux the French Academicians learned the common origin of the Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin languages; to the initiative of Nobili and to the endeavours of his followers in the same line is due the first disclosure of a new intellectual world in India. The first original documents, enabling the learned to explore that world, were drawn from their hiding-places in India, and sent in large numbers to Europe by the same missionaries. But the Karnatic mission had hardly begun when it was disturbed by the revival of the controversy, which the decision of Gregory XV had set at rest for three quarters of a century.

The Decree of Tournon

This second phase, which was much more eventful and noisy than the first, originated in Pondicherry. Since the French had settled at that place, the spiritual care of the colonists was in the hands of the Capuchin Fathers, who were also working for the conversion of the natives. With a view to forwarding the latter work, the Bishop of Mylapore or San Thome, to whose jurisdiction Pondicherry belonged, resolved, in 1699, to transfer it entirely to the Jesuits of the Karnatic mission, assigning to them a parochial church in the town and restricting the ministry of the Capuchins to the European immigrants, French or Portuguese. The Capuchins were displeased by this arrangement and appealed to Rome. The petition they laid before the Pope, in 1703, embodied not only a complaint against the division of parishes made by the Bishop, but also an accusation against the methods of the Jesuit mission in South India. Their claim on the former point was finally dismissed, but the charges were more successful. On 6 November 1703, Charles-Thomas Maillard de Tournon, a Piedmontese prelate, Patriarch of Antioch, sent by Clement XI, with the power of legatus a latere, to visit the new Christian missions of the East Indies and especially China, landed at Pondicherry. Being obliged to wait there eight months for the opportunity of passing over to China, Tournon instituted an inquiry into the facts alleged by the Capuchins. He was hindered through sickness, as he himself stated, from visiting any part of the inland mission; in the town, besides the Capuchins, who had not visited the interior, he interrogated a few natives through interpreters; the Jesuits he consulted rather cursorily, it seems.

Less than eight months after his arrival in India, he considered himself justified in issuing a decree of vital import to the whole of the Christians of India. It consisted of sixteen articles concerning practices in use or supposed to be in use among the neophytes of Madura and the Karnatic; the legate condemned and prohibited these practices as defiling the purity of the faith and religion, and forbade the missionaries, on pain of heavy censures, to permit them any more. Though dated 23 June 1704, the decree was notified to the superiors of the Jesuits only on 8 July, three days before the departure of Tournon from Pondicherry. During the short time left, the missionaries endeavoured to make him understand on what imperfect information his degree rested, and that nothing less than the ruin of the mission was likely to follow from its execution. They succeeded in persuading him to take off orally the threat of censures appended, and to suspend provisionally the prescription commanding the missionaries to give spiritual assistance to the sick pariahs, not only in the churches, but in their dwellings.

Examination of the Malabar Rites at Rome

Tournon's decree, interpreted by prejudice and ignorance as representing, in the wrong practices if condemned, the real state of the India missions, affords to this day a much-used weapon against the Jesuits. At Rome it was received with reserve. Clement XI, who perhaps overrated the prudence of his zealous legate, ordered, in the Congregation of the Holy Office, on 7 January 1706, a provisional confirmation of the decree to be sent to him, adding that it should be executed "until the Holy See might provide otherwise, after having heard those who might have something to object". And meanwhile, by an oraculum vivae vocis granted to the procurator of the Madura mission, the pope decree, "in so far as the Divine glory and the salvation of souls would permit". The objections of the missionaries and the corrections they desired were propounded by several deputies and carefully examined at Rome, without effect, during the lifetime of Clement XI and during the short pontificate of his successor Innocent XIII. Benedict XIII grappled with the case and even came to a decision, enjoining "on the bishops and missionaries of Madura, Mysore, and the Karnatic " the execution of Tournon's decree in all its parts (12 December 1727). Yet it is doubted whether that decision ever reached the mission, and Clement XII, who succeeded Benedict XIII, commanded the whole affair to be discussed anew. In four meetings held from 21 January to 6 September 1733, the cardinals of the Holy Office gave their final conclusions upon all the articles of Tournon's decree, declaring how each of them ought to be executed, or restricted and mitigated. By a Brief dated 24 August 1734, pope Clement XII sanctioned this resolution; moreover, on 13 May 1739, he prescribed an oath, by which every missionary should bind himself to obeying and making the neophytes obey exactly the Brief of 24 August 1734.

Many hard prescriptions of Tournon were mitigated by the regulation of 1734. As to the first article, condemning the omission of the use of saliva and breathing on the candidates for baptism, the missionaries, and the bishops of India with them, are rebuked for not having consulted the Holy See previously to that omission; yet, they are allowed to continue for ten years omitting these ceremonies, to which the Hindus felt so strangely loath. Other prohibitions or precepts of the legate are softened by the additions of a Quantum fieri potest, or even replaced by mere counsels or advices. In the sixth article, the taly, "with the image of the idol Pulleyar", is still interdicted, but the Congregation observes that "the missionaries say they never permitted wearing of such a taly". Now this observation seems pretty near to recognizing that possibly the prohibitions of the rather overzealous legate did not always hit upon existing abuses. And a similar conclusion might be drawn from several other articles, e.g. from the fifteenth, where we are told that the interdiction of wearing ashes and emblems after the manner of the heathen Hindus, ought to be kept, but in such a manner, it is added, "that the Constitution of Gregory XV of 31 January 1623, Romanae Senis Antistes, be observed throughout". By that Constitution, as we have already seen, some signs and ornaments, materially similar to those prohibited by Tournon, were allowed to the Christians, provided that no superstition whatever was mingled with their use. Indeed, as the Congregation of Propaganda explains in an Instruction sent to the Vicar Apostolic of Pondicherry, 15 February 1792, "the Decree of Cardinal de Tournon and the Constitution of Gregory XV agree in this way, that both absolutely forbid any sign bearing even the least semblance of superstition, but allow those which are in general use for the sake of adornment, of good manners, and bodily cleanness, without any respect to religion".

The most difficult point retained was the twelfth article, commanding the missionaries to administer the sacraments to the sick pariahs in their dwellings, publicly. Though submitting dutifully to all precepts of the Vicar of Christ, the Jesuits in Madura could not but feel distressed, at experiencing how the last especially, made their apostolate difficult and even impossible amidst the upper classes of Hindus. At their request, Benedict XIV consented to try a new solution of the knotty problem, by forming a band of missionaries who should attend only to the care of the pariahs. This scheme became formal law through the Constitution "Omnium sollicitudinum", published 12 September 1744. Except this point, the document confirmed again the whole regulation enacted by Clement XII in 1734. The arrangement sanctioned by Benedict XIV benefited greatly the lower classes of Hindu neophytes; whether it worked also to the advantage of the mission at large, is another question, about which the reports are less comforting. Be that as it may, after the suppression of the Society of Jesus (1773), the distinction between Brahmin and pariah missionaries became extinct with the Jesuit missionaries. Henceforth conversions in the higher castes were fewer and fewer, and nowadays the Christian Hindus, for the most part, belong to the lower and lowest classes. The Jesuit missionaries, when re-entering Madura in the 1838, did not come with the dress of the Brahmin saniassy, like the founders of the mission; yet they pursued a design which Nobili had also in view, though he could not carry it out, as they opened their college of Negapatam, now at Trichinopoly. A wide breach has already been made into the wall of Brahminic reserve by that institution, where hundreds of Brahmins send their sons to be taught by the Catholic missionaries. Within recent years, about fifty of these young men have embraced the faith of their teachers, at the cost of rejection from their caste and even from their family; such examples are not lost on their countrymen, either of high or low caste.

Notes

1. Brief of Beatification of John de Britto, 18 May 1852

2. Monumenta Xaveriana, I, 54

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Malabar Rites". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.