Part 2 of 2

ClothingMain article: Scythian clothing

Scythian warriors, drawn after figures on an electrum cup from the Kul-Oba kurgan burial near Kerch, Crimea. The warrior on the right strings his bow, bracing it behind his knee; note the typical pointed hood, long jacket with fur or fleece trimming at the edges, decorated trousers, and short boots tied at the ankle. Scythians apparently wore their hair long and loose, and all adult men apparently bearded. The gorytos appears clearly on the left hip of the bare-headed spearman. The shield of the central figure may be made of plain leather over a wooden or wicker base. (Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg)

Scythian warriors, drawn after figures on an electrum cup from the Kul-Oba kurgan burial near Kerch, Crimea. The warrior on the right strings his bow, bracing it behind his knee; note the typical pointed hood, long jacket with fur or fleece trimming at the edges, decorated trousers, and short boots tied at the ankle. Scythians apparently wore their hair long and loose, and all adult men apparently bearded. The gorytos appears clearly on the left hip of the bare-headed spearman. The shield of the central figure may be made of plain leather over a wooden or wicker base. (Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg)According to Herodotus, Scythian costume consisted of padded and quilted leather trousers tucked into boots, and open tunics. They rode without stirrups or saddles, using only saddle-cloths. Herodotus reports that Scythians used cannabis, both to weave their clothing and to cleanse themselves in its smoke (Hist. 4.73–75); archaeology has confirmed the use of cannabis in funerary rituals. Men seemed to have worn a variety of soft headgear—either conical like the one described by Herodotus, or rounder, more like a Phrygian cap.

Costume has been regarded as one of the main identifying criteria for Scythians. Women wore a variety of different headdresses, some conical in shape others more like flattened cylinders, also adorned with metal (golden) plaques.[60]

Scythian women wore long, loose robes, ornamented with metal plaques (gold). Women wore shawls, often richly decorated with metal (golden) plaques.

Based on numerous archeological findings in Ukraine, southern Russia, and Kazakhstan, men and warrior women wore long sleeve tunics that were always belted, often with richly ornamented belts.

Men and women wore long trousers, often adorned with metal plaques and often embroidered or adorned with felt appliqués; trousers could have been wider or tight fitting depending on the area. Materials used depended on the wealth, climate and necessity.[61]

Men and women warriors wore variations of long and shorter boots, wool-leather-felt gaiter-boots and moccasin-like shoes. They were either of a laced or simple slip on type. Women wore also soft shoes with metal (gold) plaques.

Men and women wore belts. Warrior belts were made of leather, often with gold or other metal adornments and had many attached leather thongs for fastening of the owner's gorytos, sword, whet stone, whip etc. Belts were fastened with metal or horn belt-hooks, leather thongs and metal (often golden) or horn belt-plates.[62]

ReligionMain article: Scythian religion

Scythian religion was a type of Pre-Zoroastrian Iranian religion and differed from the post-Zoroastrian Iranian thoughts.[11] The Scythian belief was a more archaic stage than the Zoroastrian and Hindu systems. The use of cannabis to induce trance and divination by soothsayers was a characteristic of the Scythian belief system.[11]

Our most important literary source on Scythian religion is Herodotus. According to him the leading deity in the Scythian pantheon was Tabiti, whom he compared to the Greek god Hestia.[5] Tabiti was eventually replaced by Atar, the fire-pantheon of Iranian tribes, and Agni, the fire deity of Indo-Aryans.[11] Other deities mentioned by Herodotus include Papaios, Api, Goitosyros/Oitosyros, Argimpasa and Thagimasadas, whom he identified with Zeus, Gaia, Apollo, Aphrodite and Poseidon, respectively. The Scythians are also said by Herodotus to have worshipped equivalents of Heracles and Ares, but he does not mention their Scythian names.[5] An additional Scythian deity, the goddess Dithagoia, is mentioned in the a dedication by Senamotis, daughter of King Skiluros, at Panticapaeum. Most of the names of Scythian deities can be traced back to Iranian roots.[5]

Herodotus states that Thagimasadas was worshipped by the Royal Scythians only, while the remaining deities were worshipped by all. He also states that "Ares", the god of war, was the only god to whom the Scythians dedicated statues, altars or temples. Tumuli were erected to him in every Scythian district, and both animal sacrifices and human sacrifices were performed in honor of him. At least one shrine to "Ares" has been discovered by archaeologists.[5]

The Scythians had professional priests, but it is not known if they constituted a hereditary class. Among the priests there was a separate group, the Enarei, who worshipped the goddess Argimpasa and assumed feminine identities.[5]

Scythian mythology gave much importance to myth of the "First Man", who was considered the ancestor of them and their kings. Similar myths are common among other Iranian peoples. Considerable importance was given to the division of Scythian society into three hereditary classes, which consisted of warriors, priests and producers. Kings were considered part of the warrior class. Royal power was considered holy and of solar and heavenly origin.[11] The Iranian principle of royal charisma, known as khvarenah in the Avesta, played a prominent role in Scythian society. It is probable that the Scythians had a number of epic legends, which were possibly the source for Herodotus' writings on them.[5] Traces of these epics can be found in the epics of the Ossetians of the present day.[11]

In Scythian cosmology the world was divided into three parts, with the warriors, considered part of the upper world, the priests of the middle level, and the producers of the lower one.[5]

ArtMain article: Scythian art

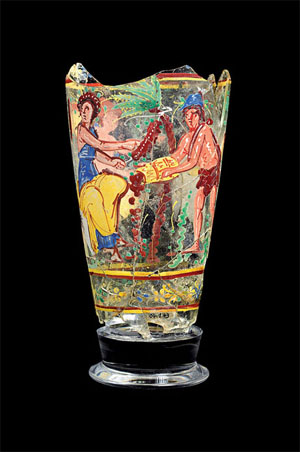

Gold pectoral, or neckpiece, from a royal kurgan in Tovsta Mohyla, Pokrov, Ukraine, dated to the second half of the 4th century BC, of Greek workmanship. The central lower tier shows three horses, each being torn apart by two griffins. Scythian art was especially focused on animal figures.

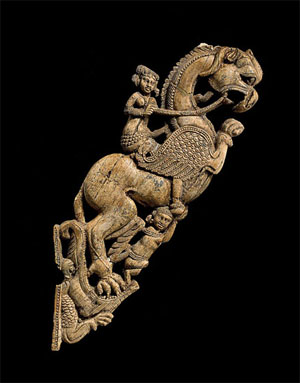

Gold pectoral, or neckpiece, from a royal kurgan in Tovsta Mohyla, Pokrov, Ukraine, dated to the second half of the 4th century BC, of Greek workmanship. The central lower tier shows three horses, each being torn apart by two griffins. Scythian art was especially focused on animal figures.The art of the Scythians and related peoples of the Scythian cultures is known as Scythian art. It is particularly characterized by its use of the animal style.[5]

Scythian animal style appears in an already established form Eastern Europe in the 8th century BC along with the Early Scythian archaeological culture itself. It bears little resemblance to the art of pre-Scythian cultures of the area. Some scholars suggest the art style developed under Near Eastern influence during the military campaigns of the 7th century BC, but the more common theory is that it developed on the eastern part of the Eurasian Steppe under Chinese influence. Others have sought to reconcile the two theories, suggesting that the animal style of the west and eastern parts of the steppe developed independently of each other, under Near Eastern and Chinese influences, respectively. Regardless, the animal style art of the Scythians differs considerable from that of peoples living further east.[5]

Scythian animal style works are typically divided into birds, ungulates and beasts of prey. This probably reflects the tripatriate division of the Scythian cosmos, with birds belonging to the upper level, ungulates to the middle level and beasts of prey in the lower level.[5]

Images of mythological creatures such a griffins are not uncommon in Scythian animal style, but these are probably the result of Near Eastern influences. By the late 6th century BC, as Scythian activity in the Near East was reduced, depictions of mythological creatures largely disappears from Scythian art. It, however, reappears again in the 4th century BC as a result of Greek influence.[5]

Anthropomorphic depictions in Early Scythian art is known only from kurgan stelae. These depict warriors with almond-shaped eyes and mustaches, often including weapons and other military equipment.[5]

Since the 5th century BC, Scythian art changed considerably. This was probably a result of Greek and Persian influence, and possibly also internal developments caused by an arrival of a new nomadic people from the east. The changes are notable in the more realistic depictions of animals, who are now often depicted fighting each other rather than being depicted individually. Kurgan stelae of the time also display traces of Greek influences, with warriors being depicted with rounder eyes and full beards.[5]

The 4th century BC show additional Greek influence. While animal style was still in use, it appears that much Scythian art by this point was being made by Greek craftsmen on behalf of Scythians. Such objects are frequently found in royal Scythian burials of the period. Depictions of human beings become more prevalent. Many objects of Scythian art made by Greeks are probably illustrations of Scythian legends. Several objects are believed to have been of religious significance.[5]

By the late 3rd century BC, original Scythian art disappears through ongoing Hellenization. The creation of anthropomorphic gravestones continued, however.[5]

Works of Scythian art are held at many museums and has been featured at many exhibitions. The largest collections of Scythian art are found at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg and the Museum of Historical Treasures of the Ukraine in Kyiv, while smaller collections are found at the Staatliche Antikensammlungen in Berlin, the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford, and the Louvre of Paris.[5]

LanguageMain article: Scythian languages

The Scythians spoke a language belonging to the Scythian languages, most probably[63] a branch of the Eastern Iranian languages.[10] Whether all the peoples included in the "Scytho-Siberian" archaeological culture spoke languages from this family is uncertain.

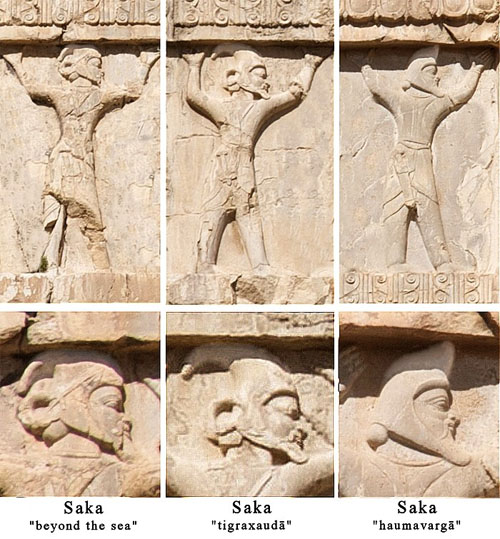

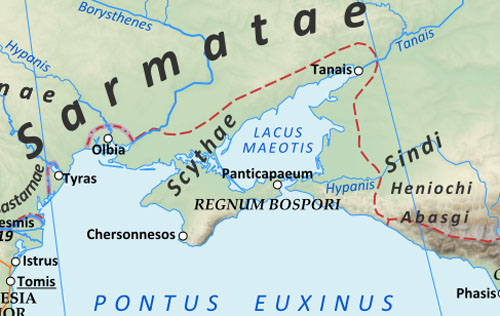

The Scythian languages may have formed a dialect continuum: "Scytho-Sarmatian" in the west and "Scytho-Khotanese" or Saka in the east.[64] The Scythian languages were mostly marginalised and assimilated as a consequence of the late antiquity and early Middle Ages Slavic and Turkic expansion. The western (Sarmatian) group of ancient Scythian survived as the medieval language of the Alans and eventually gave rise to the modern Ossetian language.[65]

AnthropologyPhysical and genetic analyses of ancient remains have concluded that Scythians as a whole possessed predominantly features of Europoids. Mongoloid phenotypes were also present in some Scythians but more frequently in eastern Scythians, suggesting that some Scythians were also descended partly from East Eurasian populations.[66]

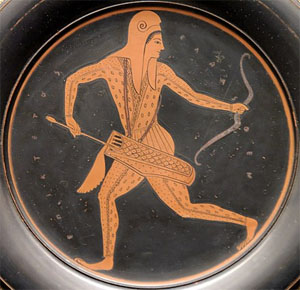

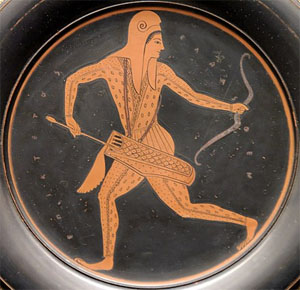

Physical appearance An Attic vase-painting of a Scythian archer (a police force in Athens) by Epiktetos, 520–500 BC

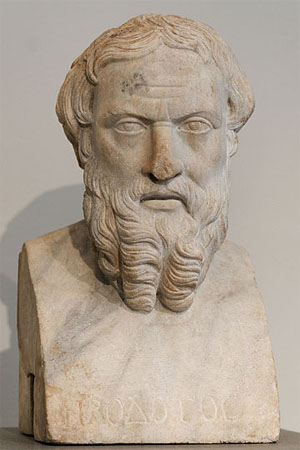

An Attic vase-painting of a Scythian archer (a police force in Athens) by Epiktetos, 520–500 BCIn artworks, the Scythians are portrayed exhibiting Caucasoid traits.[67] In Histories, the 5th-century BC Greek historian Herodotus describes the Budini of Scythia as red-haired and grey-eyed.[67] In the 5th century BC, Greek physician Hippocrates argued that the Scythians were light skinned[67][68] as well as having a particularly high rate of hypermobility, to a point of affecting warfare.[69] In the 3rd century BC, the Greek poet Callimachus described the Arismapes (Arimaspi) of Scythia as fair-haired.[67][70] The 2nd-century BC Han Chinese envoy Zhang Qian described the Sai (Saka), an eastern people closely related to the Scythians, as having yellow (probably meaning hazel or green) and blue eyes.[67] In Natural History, the 1st-century AD Roman author Pliny the Elder characterises the Seres, sometimes identified as Saka or Tocharians, as red-haired, blue-eyed and unusually tall.[67][71] In the late 2nd century AD, the Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria says that the Scythians and the Celts have long auburn hair.[67][72] The 2nd-century Greek philosopher Polemon includes the Scythians among the northern peoples characterised by red hair and blue-grey eyes.[67] In the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD, the Greek physician Galen writes that Scythians, Sarmatians, Illyrians, Germanic peoples and other northern peoples have reddish hair.[67][73] The fourth-century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that the Alans, a people closely related to the Scythians, were tall, blond and light-eyed.[74] The fourth-century bishop Gregory of Nyssa wrote that the Scythians were fair skinned and blond haired.[75] The 5th-century physician Adamantius, who often followed Polemon, describes the Scythians as fair-haired.[67][76]

GeneticsIn 2017, a genetic study of various Scythian cultures, including the Scythians, was published in Nature Communications. The study suggested that the Scythians arose as admixture between European-related groups from the Yamnaya culture and East Asian/Siberian groups. Further they found evidence for massive geneflow from East-Eurasia to West-Eurasia during the early Iron Age. While the origin of the Scythian material culture is disputed, their evidence suggest an origin in the East. Modern populations relative closely related to the ancient Scythians were found to be populations living in proximity to the sites studied, suggesting genetic continuity.[6]

Another 2017 genetic study, published in Scientific Reports, found that the Scythians shared common mithocondrial lineages with the earlier Srubnaya culture. It also noted that the Scythians differed from materially similar groups further east by the absence of east Eurasian mitochondrial lineages. The authors of the study suggested that the Srubnaya culture was the source of the Scythian cultures of at least the Pontic steppe.[39]

Krzewińska et al. (2018) found that the historical Central Asian Steppe population was genetically heterogeneous and carried genetic affinities with populations from several other regions including the Far East and the southern Urals.[40]

In 2019, a genetic study of remains from the Aldy-Bel culture of southern Siberia and proper Scythians from the Pontic–Caspian steppe, which are materially similar to each other, was published in Human Genetics. They identified Scythians as mix of West-Eurasian and East-Eurasian lineages. East Asian admixture was estimated at 26,3%. The samples of Aldy-Bel in contrast revealed increased East-Eurasian ancestry. The results indicated that the Scythians and the Aldy-Bel people were of different origins, with almost no gene flow between them.[77]

Järve et al. (2019) found that the nomadic Scythians were of different genetic origins. They suggested that migrations must have played a role in the emergence of the Scythians as the dominant power on the Pontic steppe.[41]

A 2021 study by Gnecchi-Ruscone et al., concluded that the Scythians were of multiple origin and that they originated from an admixture event in the Bronze Age. They further concluded that their evidence does not support an origin of the Scythian material culture from the Pontic-Caspian Steppe. The Scythians genetically formed from mixture between a steppe_MLBA sources (which could be associated with different cultures such as Sintashta, Srubnaya, and Andronovo) and a specific East-Eurasian source that was already present during the LBA in the neighboring northern Mongolia region.[78]

Legacy

Late AntiquitySee also: Sarmatians, Alans, and Ossetians

In Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the name "Scythians" was used in Greco-Roman literature for various groups of nomadic "barbarians" living on the Pontic-Caspian steppe. This includes Huns, Goths, Ostrogoths, Turkic peoples, Pannonian Avars and Khazars. None of these peoples had any relation whatsoever with the actual Scythians.[25]

Byzantine sources also refer to the Rus' raiders who attacked Constantinople circa 860 in contemporary accounts as "Tauroscythians", because of their geographical origin, and despite their lack of any ethnic relation to Scythians. Patriarch Photius may have first applied the term to them during the siege of Constantinople.[citation needed]

Early Modern usage Scythians at the Tomb of Ovid (c. 1640), by Johann Heinrich Schönfeld

Scythians at the Tomb of Ovid (c. 1640), by Johann Heinrich SchönfeldOwing to their reputation as established by Greek historians, the Scythians long served as the epitome of savagery and barbarism.[citation needed]

The New Testament includes a single reference to Scythians in Colossians 3:11:[79] in a letter ascribed to Paul, "Scythian" is used as an example of people whom some label pejoratively, but who are, in Christ, acceptable to God:

Here there is no Greek or Jew. There is no difference between those who are circumcised and those who are not. There is no rude outsider, or even a Scythian. There is no slave or free person. But Christ is everything. And he is in everything.[79]

Shakespeare, for instance, alluded to the legend that Scythians ate their children in his play King Lear:

The barbarous Scythian

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite, shall to my bosom

Be as well neighbour'd, pitied, and relieved,

As thou my sometime daughter.[80]

Characteristically, early modern English discourse on Ireland, such as that of William Camden and Edmund Spenser, frequently resorted to comparisons with Scythians in order to confirm that the indigenous population of Ireland descended from these ancient "bogeymen", and showed themselves as barbaric as their alleged ancestors.[81][82]

Romantic nationalism: Battle between the Scythians and the Slavs (Viktor Vasnetsov, 1881)Descent claims

Romantic nationalism: Battle between the Scythians and the Slavs (Viktor Vasnetsov, 1881)Descent claims Eugène Delacroix's painting of the Roman poet, Ovid, in exile among the Scythians[83]

Eugène Delacroix's painting of the Roman poet, Ovid, in exile among the Scythians[83]Further information: Sarmatism and Generations of Noah

Some legends of the Poles,[84] the Picts, the Gaels, the Hungarians, among others, also include mention of Scythian origins. Some writers claim that Scythians figured in the formation of the empire of the Medes and likewise of Caucasian Albania.[citation needed]

The Scythians also feature in some national origin-legends of the Celts. In the second paragraph of the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, the élite of Scotland claim Scythia as a former homeland of the Scots. According to the 11th-century Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland), the 14th-century Auraicept na n-Éces and other Irish folklore, the Irish originated in Scythia and were descendants of Fénius Farsaid, a Scythian prince who created the Ogham alphabet.[citation needed]

The Carolingian kings of the Franks traced Merovingian ancestry to the Germanic tribe of the Sicambri. Gregory of Tours documents in his History of the Franks that when Clovis was baptised, he was referred to as a Sicamber with the words "Mitis depone colla, Sicamber, adora quod incendisti, incendi quod adorasti." The Chronicle of Fredegar in turn reveals that the Franks believed the Sicambri to be a tribe of Scythian or Cimmerian descent, who had changed their name to Franks in honour of their chieftain Franco in 11 BC.[citation needed]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, foreigners regarded the Russians as descendants of Scythians. It became conventional to refer to Russians as Scythians in 18th-century poetry, and Alexander Blok drew on this tradition sarcastically in his last major poem, The Scythians (1920). In the 19th century, romantic revisionists in the West transformed the "barbarian" Scyths of literature into the wild and free, hardy and democratic ancestors of all blond Indo-Europeans.[citation needed]

Based on such accounts of Scythian founders of certain Germanic as well as Celtic tribes, British historiography in the British Empire period such as Sharon Turner in his History of the Anglo-Saxons, made them the ancestors of the Anglo-Saxons.[citation needed]

The idea was taken up in the British Israelism of John Wilson, who adopted and promoted the idea that the "European Race, in particular the Anglo-Saxons, were descended from certain Scythian tribes, and these Scythian tribes (as many had previously stated from the Middle Ages onward) were in turn descended from the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel."[85] Tudor Parfitt, author of The Lost Tribes of Israel and Professor of Modern Jewish Studies, points out that the proof cited by adherents of British Israelism is "of a feeble composition even by the low standards of the genre."[86]

Legends about the origin of the population from the Scythian ancestor Targitai – son of Borisfen's daughter (that was the name of the Dnipro river in antiquity) – are popular in Ukraine. In Ukraine, which territory Herodotus described in his work on the Scythians, there are discussions about how serious the influence of the Scythians was on the ethnogenesis of Ukrainians.[87] Currently, there are studies that indicate the relationship of Slavic tribes living in Ukraine with the Scythian plowmen (plough man) and farmers who belonged to the Proto-Slavic Chernoles or Black Forest culture.[88][89] The description of Scythia by Herodotus is also called the oldest description of Ukraine.[90] Despite the absolute dissimilarity of modern Ukrainian and hypothetical Scythian languages, researchers claim it still left some marks,[91] such as the fricative pronunciation of the letter "г", the specific alternation, etc.[92]

Related ancient peoplesHerodotus and other classical historians listed quite a number of tribes who lived near the Scythians, and presumably shared the same general milieu and nomadic steppe culture, often called "Scythian culture", even though scholars may have difficulties in determining their exact relationship to the "linguistic Scythians". A partial list of these tribes includes the Agathyrsi, Geloni, Budini, and Neuri.

• Abii

• Agathyrsi

• Amardi

• Amyrgians

• Androphagi

• Budini

• Cimmerians

• Dahae

o Parni

• Gelae

• Gelonians

• Hamaxobii

• Huns

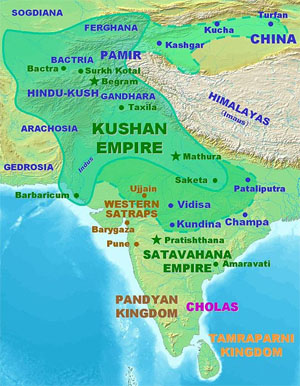

• Indo-Scythians

o Apracharajas

o Kambojas

• Massagetae

o Apasiacae

• Melanchlaeni

• Orthocorybantians

• Saka

• Sarmatians

• Sindi

• Spali

• Tapur

• Tauri

• Thyssagetae

See also• Scythia

• Scythian art

• Scythian languages

• Eurasian nomads

• Nomadic empire

• Pre-Achaemenid Scythian kings of Iran

References1. Scythian /ˈsɪθiən/ or /ˈsɪðiən/, Scyth /ˈsɪθ/, but note Scytho- /ˈsaɪθoʊ/ in composition (OED).

2. * Dandamayev 1994, p. 37: "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

Cernenko 2012, p. 3: "The Scythians lived in the Early Iron Age, and inhabited the northern areas of the Black Sea (Pontic) steppes. Though the 'Scythian period' in the history of Eastern Europe lasted little more than 400 years, from the 7th to the 3rd centuries BC, the impression these horsemen made upon the history of their times was such that a thousand years after they had ceased to exist as a sovereign people, their heartland and the territories which they dominated far beyond it continued to be known as 'greater Scythia'."

Melykova 1990, pp. 97–98: "From the end of the 7th century B.C. to the 4th century B.C. the Central- Eurasian steppes were inhabited by two large groups of kin Iranian-speaking tribes – the Scythians and Sarmatians [...] "[ I]t may be confidently stated that from the end of the 7th century to the 3rd century B.C. the Scythians occupied the steppe expanses of the north Black Sea area, from the Don in the east to the Danube in the West."

Ivantchik 2018: "Scythians, a nomadic people of Iranian origin who flourished in the steppe lands north of the Black Sea during the 7th–4th centuries BCE (Figure 1). For related groups in Central Asia and India, see [...]"

Sulimirski 1985, pp. 149–153: "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock [...] The main Iranian-speaking peoples of the region at that period were the Scyths and the Sarmatians [...] [T]he population of ancient Scythia was far from being homogeneous, nor were the Scyths themselves a homogeneous people. The country called after them was ruled by their principal tribe, the "Royal Scyths" (Her. iv. 20), who were of Iranian stock and called themselves "Skolotoi" (iv. 6); they were nomads who lived in the steppe east of the Dnieper up to the Don, and in the Crimean steppe [...] The eastern neighbours of the "Royal Scyths", the Sauromatians, were also Iranian; their country extended over the steppe east of the Don and the Volga."

Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 547: "The name 'Scythian' is met in the classical authors and has been taken to refer to an ethnic group or people, also mentioned in Near Eastern texts, who inhabited the northern Black Sea region."

West 2002, pp. 437–440: "Ordinary Greek (and later Latin) usage could designate as Scythian any northern barbarian from the general area of the Eurasian steppe, the virtually treeless corridor of drought-resistant perennial grassland extending from the Danube to Manchuria. Herodotus seeks greater precision, and this essay is focussed on his Scythians, who belong to the North Pontic steppe [...] These true Scyths seems to be those whom he calls Royal Scyths, that is, the group who claimed hegemony [...] apparently warrior-pastoralists. It is generally agreed, from what we know of their names, that these were people of Iranian stock [...]"

Jacobson 1995, pp. 36–37: "When we speak of Scythians, we refer to those Scytho-Siberians who inhabited the Kuban Valley, the Taman and Kerch peninsulas, Crimea, the northern and northeastern littoral of the Black Sea, and the steppe and lower forest steppe regions now shared between Ukraine and Russia, from the seventh century down to the first century B.C [...] They almost certainly spoke an Iranian language [...]"

Di Cosmo 1999, p. 924: "The first historical steppe nomads, the Scythians, inhabited the steppe north of the Black Sea from about the eight century B.C."

Rice, Tamara Talbot. "Central Asian arts: Nomadic cultures". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved October 4, 2019. [Saka] gold belt buckles, jewelry, and harness decorations display sheep, griffins, and other animal designs that are similar in style to those used by the Scythians, a nomadic people living in the Kuban basin of the Caucasus region and the western section of the Eurasian plain during the greater part of the 1st millennium bc.

3. Jacobson 1995, p. [page needed].

4. Cunliffe, Barry (26 September 2019). The Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe. Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-19-255186-3.

5. Ivantchik 2018

6. Unterländer, Martina (March 3, 2017). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. 8: 14615. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814615U. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537. Genomic inference reveals that Scythians in the east and the west of the steppe zone can best be described as a mixture of Yamnaya-related ancestry and an East Asian component. Demographic modelling suggests independent origins for eastern and western groups with ongoing gene-flow between them, plausibly explaining the striking uniformity of their material culture. We also find evidence that significant gene-flow from east to west Eurasia must have occurred early during the Iron Age. The origin of the widespread Scythian culture has long been debated in Eurasian archaeology. The northern Black Sea steppe was originally considered the homeland and centre of the Scythians3 until Terenozhkin formulated the hypothesis of a Central Asian origin4. On the other hand, evidence supporting an east Eurasian origin includes the kurgan Arzhan 1 in Tuva5, which is considered the earliest Scythian kurgan5. Dating of additional burial sites situated in east and west Eurasia confirmed eastern kurgans as older than their western counterparts6,7. Additionally, elements of the characteristic ‘Animal Style’ dated to the tenth century BCE1,4 were found in the region of the Yenisei river and modern-day China, supporting the early presence and origin of Scythian culture in the East.

7. Di Cosmo 1999, p. 891: "Even though there were fundamental ways in which nomadic groups over such a vast territory differed, the terms "Scythian" and "Scythic" have been widely adopted to describe a special phase that followed the widespread diffusion of mounted nomadism, characterized by the presence of special weapons, horse gear, and animal art in the form of metal plaques. Archaeologists have used the term "Scythic continuum" in a broad cultural sense to indicate the early nomadic cultures of the Eurasian steppe. The term "Scythic" draws attention to the fact that there are elements – shapes of weapons, vessels, and ornaments, as well as lifestyle – common to both the eastern and western ends of the Eurasian steppe region. However, the extension and variety of sites across Asia makes Scythian and Scythic terms too broad to be viable, and the more neutral "early nomadic" is preferable, since the cultures of the Northern Zone cannot be directly associated with either the historical Scythians or any specific archaeological culture defined as Saka or Scytho-Siberian."

8. Kramrisch, Stella. "Central Asian Arts: Nomadic Cultures". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved September 1, 2018. The Śaka tribe was pasturing its herds in the Pamirs, central Tien Shan, and in the Amu Darya delta. Their gold belt buckles, jewelry, and harness decorations display sheep, griffins, and other animal designs that are similar in style to those used by the Scythians, a nomadic people living in the Kuban basin of the Caucasus region and the western section of the Eurasian plain during the greater part of the 1st millennium bc.

9. * Ivantchik 2018: "Scythians, a nomadic people of Iranian origin [...]"

Harmatta 1996, p. 181: "[ b]oth Cimmerians and Scythians were Iranian peoples."

Sulimirski 1985, pp. 149–153: "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock [...] [T]he population of ancient Scythia was far from being homogeneous, nor were the Scyths themselves a homogeneous people. The country called after them was ruled by their principal tribe, the "Royal Scyths" (Her. iv. 20), who were of Iranian stock and called themselves "Skolotoi" [...]"

West 2002, pp. 437–440: "[T]rue Scyths seems to be those whom [Herodotus] calls Royal Scyths, that is, the group who claimed hegemony [...] apparently warrior-pastoralists. It is generally agreed, from what we know of their names, that these were people of Iranian stock [...]"

Rolle 1989, p. 56: "The physical characteristics of the Scythians correspond to their cultural affiliation: their origins place them within the group of Iranian peoples."

Rostovtzeff 1922, p. 13: "The Scythian kingdom [...] was succeeded in the Russian steppes by an ascendancy of various Sarmatian tribes — Iranians, like the Scythians themselves."

Minns 2011, p. 36: "The general view is that both agricultural and nomad Scythians were Iranian."

10. * Dandamayev 1994, p. 37: "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

Davis-Kimball, Bashilov & Yablonsky 1995, p. 91: "Near the end of the 19th century V.F. Miller (1886, 1887) theorized that the Scythians and their kindred, the Sauromatians, were Iranian-speaking peoples. This has been a popular point of view and continues to be accepted in linguistics and historical science [...]"

Melykova 1990, pp. 97–98: "From the end of the 7th century B.C. to the 4th century B.C. the Central- Eurasian steppes were inhabited by two large groups of kin Iranian-speaking tribes – the Scythians and Sarmatians [...]"

Melykova 1990, p. 117: "All contemporary historians, archeologists and linguists are agreed that since the Scythian and Sarmatian tribes were of the Iranian linguistic group [...]"

Sulimirski 1985, pp. 149–153: "During the first half of the first millennium B.C., c. 3,000 to 2,500 years ago, the southern part of Eastern Europe was occupied mainly by peoples of Iranian stock [...] The main Iranian-speaking peoples of the region at that period were the Scyths and the Sarmatians [...]"

Jacobson 1995, pp. 36–37: "When we speak of Scythians, we refer to those Scytho-Siberians who inhabited the Kuban Valley, the Taman and Kerch peninsulas, Crimea, the northern and northeastern littoral of the Black Sea, and the steppe and lower forest steppe regions now shared between Ukraine and Russia, from the seventh century down to the first century B.C [...] They almost certainly spoke an Iranian language [...]"

11. Harmatta 1996, pp. 181–182

12. "Scythian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

13. Hambly, Gavin. "History of Central Asia: Early Western Peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

14. Beckwith 2009, p. 117: "The Scythians, or Northern Iranians, who were culturally and ethnolinguistically a single group at the beginning of their expansion, had earlier controlled the entire steppe zone."

15. Beckwith 2009, pp. 377–380: "The preservation of the earlier form. *Sakla. in the extreme eastern dialects supports the historicity of the conquest of the entire steppe zone by the Northern Iranians—literally, by the 'Scythians'—in the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age [...]"

16. Beckwith 2009, p. 11

17. Young, T. Cuyler. "Ancient Iran: The kingdom of the Medes". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

18. Beckwith 2009, p. 49

19. "Sarmatian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

20. Brzezinski & Mielczarek 2002, p. 39: "Indeed, it is now accepted that the Sarmatians merged in with pre-Slavic populations."

21. Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 523: "In their Ukrainian and Polish homeland the Slavs were intermixed and at times overlain by Germanic speakers (the Goths) and by Iranian speakers (Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans) in a shifting array of tribal and national configurations."

22. Davis-Kimball, Bashilov & Yablonsky 1995, p. 165: "Iranian-speaking nomadic tribes, specifically the Scythians and Sarmatians, are special among the North Caucasian peoples. The Scytho-Sarmatians were instrumental in the ethnogenesis of some of the modern peoples living today in the Caucasus. Of importance in this group are the Ossetians, an Iranian-speaking group of people who are believed to have descended from the North Caucasian Alans."

23. Beckwith 2009, pp. 58–70

24. "Scythian art". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

25. Dickens 2018, p. 1346: "Greek authors [...] frequently applied the name Scythians to later nomadic groups who had no relation whatever to the original Scythians"

26. Szemerényi 1980

27. K. E. Eduljee. "Histories by Herodotus, Book 4 Melpomene [4.6]". Zoroastrian Heritage. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

28. Lendering, Jona (February 14, 2019). "Scythians / Sacae". Livius.org. Retrieved October 4,2019.

29. Unterländer, Martina (March 3, 2017). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. 8: 14615. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814615U. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537. During the first millennium BC, nomadic people spread over the Eurasian Steppe from the Altai Mountains over the northern Black Sea area as far as the Carpathian Basin [...] Greek and Persian historians of the 1st millennium BCE chronicle the existence of the Massagetae and Sauromatians, and later, the Sarmatians and Sacae: cultures possessing artefacts similar to those found in classical Scythian monuments, such as weapons, horse harnesses and a distinctive ‘Animal Style' artistic tradition. Accordingly, these groups are often assigned to the Scythian culture [...]

30. Davis-Kimball, Bashilov & Yablonsky 1995, pp. 27–28

31. West 2002, pp. 437–440

32. Watson 1972, p. 142: "The term 'Scythic' has been used above to denote a group of basic traits which characterize material culture from the fifth to the first century B.C. in the whole zone stretching from the Transpontine steppe to the Ordos, and without ethnic connotation. How far nomadic populations in central Asia and the eastern steppes may be of Scythian, Iranic, race, or contain such elements makes a precarious speculation."

33. David & McNiven 2018: "Horse-riding nomadism has been referred to as the culture of 'Early Nomads'. This term encompasses different ethnic groups (such as Scythians, Saka, Massagetae, and Yuezhi) [...]"

34. Davis-Kimball, Bashilov & Yablonsky 1995, p. 33

35. Herodotus 1910, 4.11

36. Drews 2004, p. 92: "Ever since critical history began, scholars have recognized that much of what Herodotos gives us is silly."

37. Mallory 1991, pp. 51–53

38. Dolukhanov 1996, p. 125

39. Juras, Anna (March 7, 2017). "Diverse origin of mitochondrial lineages in Iron Age Black Sea Scythians". Nature Communications. 7: 43950. Bibcode:2017NatSR...743950J. doi:10.1038/srep43950. PMC 5339713. PMID 28266657.

40. Krzewińska, Maja (October 3, 2018). "Ancient genomes suggest the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe as the source of western Iron Age nomads". Nature Communications. 4 (10): eaat4457. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.4457K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat4457. PMC 6223350. PMID 30417088. The nomadic populations were heterogeneous and carried genetic affinities with populations from several other regions including the Far East and the southern Urals. Genetic analyses of maternal lineages of Scythians suggest a mixed origin and an east-west admixture gradient across the Eurasian steppe (10–12). The genomics of two early Scythian Aldy-Bel individuals (13) showed genetic affinities to eastern Asian populations (12).

41. Järve, Mari (July 22, 2019). "Shifts in the Genetic Landscape of the Western Eurasian Steppe Associated with the Beginning and End of the Scythian Dominance". Current Biology. 29 (14): 2430–2441. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.019. PMID 31303491. S2CID 195887262. The Early Iron Age nomadic Scythians have been described as a confederation of tribes of different origins, based on ancient DNA evidence [1, 2, 3]. All samples of this study also possessed at least one additional eastern component, one of which was nearly at 100% in modern Nganasans (orange) and the other in modern Han Chinese (yellow; Figure S2). The eastern components were present in variable proportions in the samples of this study.

42. Cernenko 2012, pp. 3–4

43. Schmitt, Rüdiger (March 20, 1912). "Haumavargā". Encyclopædia Iranica.

44. Cernenko 2012, pp. 21–29

45. Cernenko 2012, pp. 29–32

46. Hughes 1991, pp. 64–65, 118

47. Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, pp. 547–591

48. Tsetskhladze 2002

49. Tsetskhladze 2010

50. Curry, Andrew (22 May 2015). "Gold Artifacts Tell Tale of Drug-Fueled Rituals and "Bastard Wars"". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

51. Traces of the Iranian root xšaya – "ruler" – may persist in all three names.

52. Herodotus 1910, 4.5–4.7

53. Herodotus 1910, 4.20

54. Belier 1991, p. 69

55. Potts 1999, p. 345

56. Cernenko 2012, p. 20

57. Anthony 2010, p. 329

58. Armbruster, Barbara (2009-12-31). "Gold technology of the ancient Scythians – gold from the kurgan Arzhan 2, Tuva". ArcheoSciences. Revue d'archéométrie (33): 187–193. doi:10.4000/archeosciences.2193. ISSN 1960-1360.

59. Jettmar, Karl (1971). "Metallurgy in the Early Steppes" (PDF). Artibus Asiae. 33 (1/2): 5–16. doi:10.2307/3249786. JSTOR 3249786.

60. Margarita Gleba. "You Are What You Wear: Scythian Costume as Identity". Dressing the Past. Academia. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

61. Youngsoo Yi-Chang (2016). "The Study on the Scythian Costume III -Focaused on the Scythian of the Pazyryk region in Altai-". Fashion & Textile Research Journal (한국의류산업학회지). Korea Institute of Science and Technology. 18 (4). doi:10.5805/SFTI.2016.18.4.424. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

62. Esther Jacobson (1995). The Art of the Scythians: The Interpenetration of Cultures at the Edge of the Hellenic World. BRILL. pp. 11–. ISBN 90-04-09856-9.

63. Lubotsky 2002, p. 190

64. Lubotsky 2002, pp. 189–202

65. Testen 1997, p. 707

66. "Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk Burials of Iron Age Horsemen". Archived from the original on 15 October 2014.

67. Day 2001, pp. 55–57

68. Hippocrates 1886, 20 "The Scythians are a ruddy race because of the cold, not through any fierceness in the sun's heat. It is the cold that burns their white skin and turns it ruddy."

69. Beighton PH, Grahame R, Bird HA (2011). Hypermobility of Joints. Springer. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84882-085-2. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

70. Callimachus 1921, Hymn IV. To Delos. 291 "The first to bring thee these offerings fro the fair-haired Arimaspi [...]"

71. Pliny 1855, Book VI, Chap. 24 ". These people, they said, exceeded the ordinary human height, had flaxen hair, and blue eyes [...]"

72. Clement 1885, Book 3. Chapter III "Of the nations, the Celts and Scythians wear their hair long, but do not deck themselves. The bushy hair of the barbarian has something fearful in it; and its auburn (ξανθόν) colour threatens war [...]"

73. Galen 1881, De Temperamentis. Book 2 "Ergo Aegyptii, Arabes, & Indi, omnes denique qui calidam & siccam regionem incolunt, nigros, exiguique incrementi, siccos, crispos, & fragiles pilos habent. Contra qui humidam, frigidamque regionem habitant, Illyrii, Germani, Sarmatae, & omnis Scytica plaga, modice auctiles, & graciles, & rectos, & rufos optinent. Qui uero inter hos temperatum colunt tractum, hi pilos plurimi incrementi, & robustissimos, & modice nigros, & mediocriter crassos, tum nec prorsus crispos, nec omnino rectos edunt."

74. Marcellinus 1862, Book XXI, II, 21 "Nearly all the Alani are men of great stature and beauty; their hair is somewhat yellow, their eyes are terribly fierce"

75. Gregory 1995, p. 124: "[T]he Ethiopian's son black, but the Scythian white-skinned and with hair of a golden tinge."

76. Adamantius. Physiognomica. 2. 37

77. Mary, Laura (March 28, 2019). "Genetic kinship and admixture in Iron Age Scytho-Siberians". Human Genetics. 138 (4): 411–423. doi:10.1007/s00439-019-02002-y. PMID 30923892. S2CID 85542410. Mitochondrial lineages in the NPR Scythians analyzed in this study appear to consist of a mixture of west and east Eurasian haplogroups. West Eurasian lineages were represented by subdivisions of haplogroup U5 (U5a2a1, U5a1a1, U5a1a2b, U5a2b, U5a1b, U5b2a1a2, six individuals total, 31.6%), H (H and H5b, three individuals total, 15.8%), J (J1c2 and J2b1a6, two individuals, 10.5%), as well as haplogroups N1b1a, W3a and T2b (one individual each, 5.3% each specimen). East Eurasian mt lineages were represented by haplogroups A, D4j2, F1b, M10a1a1a, and H8c (represented by a single individual), in total, comprising 26.3% of our sample set. The absence of R1b lineages in the Scytho-Siberian individuals tested so far and their presence in the North Pontic Scythians suggest that these 2 groups had a completely different paternal lineage makeup with nearly no gene flow from male carriers between them.

78. Gnecchi-Ruscone, Guido Alberto; Khussainova, Elmira; Kahbatkyzy, Nurzhibek; Musralina, Lyazzat; Spyrou, Maria A.; Bianco, Raffaela A.; Radzeviciute, Rita; Martins, Nuno Filipe Gomes; Freund, Caecilia; Iksan, Olzhas; Garshin, Alexander (March 2021). "Ancient genomic time transect from the Central Asian Steppe unravels the history of the Scythians". Science Advances. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe4414. PMC 7997506. PMID 33771866. Our findings shed new light onto the debate about the origins of the Scythian cultures. We do not find support for a western Pontic-Caspian steppe origin, which is, in fact, highly questioned by more recent historical/archeological work (1, 2). The Kazakh Steppe origin hypothesis finds instead a better correspondence with our results, but rather than finding support for one of the two extreme hypotheses, i.e., single origin with population diffusion versus multiple independent origins with only cultural transmission, we found evidence for at least two independent origins as well as population diffusion and admixture (Fig. 4B). In particular, the eastern groups are consistent with descending from a gene pool that formed as a result of a mixture between preceding local steppe_MLBA sources (which could be associated with different cultures such as Sintashta, Srubnaya, and Andronovo that are genetically homogeneous) and a specific eastern Eurasian source that was already present during the LBA in the neighboring northern Mongolia region (27).

79. "Colossians 3:11 New International Version (NIV)". BibleGateway.com. Zondervan. Retrieved October 4, 2019. Here there is no Gentile or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave or free, but Christ is all, and is in all.

80. King Lear Act I, Scene i.

81. Spenser 1970

82. Camden 1701

83. Lomazoff & Ralby 2013, p. 63

84. Waśko 1997

85. Parfitt 2003, p. 54

86. Parfitt 2003, p. 61

87. "Чиїми предками були скіфи?". tyzhden.ua. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

88. "Сегеда Сергій. Антропологія. Антропологічні особливості давнього населення України".

89.

http://resource.history.org.ua/cgi-bin/ ... orysfenity90. "§ 8. Begin research in Ukraine | Physical Geography of Ukraine, Grade 8". geomap.com.ua. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

91. "Античне коріння "шароварщини"". Історична правда. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

92. "Астерікс і Обелікс – французи, а скіфи – не українці? – Всеукраїнський незалежний медійний простір "Сіверщина"". siver.com.ua. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

Early sources• Callimachus (1921). Callimachus, Hymns and Epigrams. Lycophron. Aratus. Translated by Mair, A. W.; Mair, G. W. Heinemann.

• Camden, William (1701). Camden's Britannia. J. B.

• Clement (1885). Roberts, Alexander; Donaldson, James (eds.). The Instructor. Ante-Nicene Christian Library. Translated by Wilson, William. T&T Clark.

• Galen (1881). Galeni pergamensis de temperamentis, et de inaequali intemperie (in Latin). Translated by Linacre, Thomas. Cambridge University Press.

• Gregory (1995). "Book II". Against Eunomius. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Second series. Translated by Wilson, Rev. H. A. Hendrickson. pp. 101–135. ISBN 1-56563-121-8.

• Herodotus (1910). The History of Herodotus. Translated by Rawlinson, George. J. M. Dent.

• Hippocrates (1886). Περί αέρων, υδάτων, τόπων [Airs, Waters, Places]. Translated by Jones, W. H. S. Harvard University Press.

• Marcellinus, Ammianus (1862). Roman History. Translated by Yonge, Charles Duke. Bohn.

• Pliny (1855). The Natural History. Translated by Bostock, John. Taylor & Francis.

• Spenser, Edmund (1970). A View of the Present State of Ireland. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-812408-5.

Modern sources• Anthony, David W. (2010). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3110-4.

• Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2994-1.

• Belier, Wouter W. (1991). Decayed Gods: Origin and Development of Georges Dumézil's "Idéologie Tripartie". BRILL. ISBN 9004094873.

• Brzezinski, Richard; Mielczarek, Mariusz (2002). The Sarmatians 600 BC–AD 450. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 1-84176-485-X.

• Cernenko, E. V. (2012). The Scythians 700–300 BC. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-773-8.

• Dandamayev, Muhammad (1994). "Media and Achaemenid Iran". In Harmatta, János Harmatta(ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. D. 250. 1. UNESCO. pp. 35–64. ISBN 9231028464.

• David, Bruno; McNiven, Ian J. (2018). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-060735-7.

• Davis-Kimball, Jeannine; Bashilov, Vladimir A.; Yablonsky, Leonid T. (1995). Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age. Zinat Press. ISBN 978-1-885979-00-1.

• Day, John V. (2001). Indo-European Origins: The Anthropological Evidence. Institute for the Study of Man. ISBN 0-941694-75-5.

• Dickens, Mark (2018). "Scythians". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. pp. 1346–1347. ISBN 978-0-19-174445-7. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

• Di Cosmo, Nicola (1999). "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China (1,500 – 221 BC)". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L.(eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 885–996. ISBN 0-521-47030-7.

• Dolukhanov, Pavel Markovich (1996). The Early Slavs: Eastern Europe from the Initial Settlement to the Kievan Rus. Longman. ISBN 0-582-23618-5.

• Drews, Robert (2004). Early Riders: The Beginnings of Mounted Warfare in Asia and Europe. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-203-07107-7.

• Harmatta, János (1996). "The Scythians". In Herrmann, Joachim; Zürcher, Erik (eds.). History of Humanity: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. 3. UNESCO. pp. 181–182. ISBN 923102812X.

• Hughes, Dennis D. (1991). Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece. Psychology Press. ISBN 0-415-03483-3.

• Ivantchik, Askold (April 25, 2018). "Scythians". Encyclopædia Iranica.

• Jacobson, Esther (1995). The Art of the Scythians: The Interpenetration of Cultures at the Edge of the Hellenic World. BRILL. ISBN 9004098569.

• Lomazoff, Amanda; Ralby, Aaron (2013). "Scythians and Sarmatians". The Atlas of Military History. Simon & Schuster. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-60710-985-3.

• Lubotsky, Alexander (2002). "Scythian Elements In Old Iranian" (PDF). Proceedings of the British Academy. Oxford University Press. 116(2): 189–202.

• Mallory, J. P. (1991). "The Iranians". In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language Archeology and Myth. Thames & Hudson. pp. 48–56.

• Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-884964-98-2.

• Melykova, A. I. (1990). "The Scythians and Sarmatians". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–117. ISBN 978-1-139-05489-8.

• Minns, Ellis Hovell (2011). Scythians and Greeks: A Survey of Ancient History and Archaeology on the North Coast of the Euxine from the Danube to the Caucasus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-02487-7.

• Nicholson, Oliver (2018). "Scythians (Saka)". The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. pp. 1346–1347. ISBN 978-0-19-256246-3.

• Parfitt, Tudor (2003). The Lost Tribes of Israel: The History of a Myth. Phoenix. ISBN 1-84212-665-2.

• Potts, Daniel T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56496-4.

• Rolle, Renate (1989). The World of the Scythians. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06864-5.

• Rostovtzeff, Michael (1922). Iranians & Greeks In South Russia. Clarendon Press.

• Sulimirski, T. (1985). "The Scyths". In Gershevitch, I. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran: The Median and Achaemenian Periods. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 149–199. ISBN 978-1-139-05493-5.

• Sulimirski, T.; Taylor, T. (1991). "The Scythians". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Sollberger, E.; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC. 3 (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 547–590. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

• Szemerényi, Oswald (1980). Four old Iranian ethnic names: Scythian – Skudra – Sogdian – Saka (PDF). Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 0-520-06864-5.

• Testen, David (1997). "Ossetic Phonology". In Kaye, Alan S. (ed.). Phonologies of Asia and Africa: (including the Caucasus). 2. Eisenbrauns. pp. 707–733. ISBN 1-57506-019-1.

• Tsetskhladze, Gocha R. (December 17, 2002) [1998]. "Who Built the Scythian and Thracian Royal and Elite Tombs?". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. Wiley. 17 (1): 55–92. doi:10.1111/1468-0092.00051.

• Tsetskhladze, Gocha R. (2010). North Pontic Archaeology: Recent Discoveries and Studies. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004120419.

• Watson, William (October 1972). "The Chinese Contribution to Eastern Nomad Culture in the Pre-Han and Early Han Periods". World Archaeology. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. 4 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1080/00438243.1972.9979528. JSTOR 123972.

• Waśko, Andrzej (April 1997). "Sarmatism or the Enlightenment: The Dilemma of Polish Culture". Sarmatian Review. Oxford University Press. XVII (2).

• West, Stephanie (2002). "Scythians". In Bakker, Egbert J.; de Jong, Irene J. F.; van Wees, Hans (eds.). Brill's Companion to Herodotus. Brill. pp. 437–456. ISBN 978-90-04-21758-4.

Further reading• Baumer, Christoph (2012). The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-060-5.

• Davis-Kimball, Jeannine (2003). Warrior Women: An Archaeologist's Search for History's Hidden Heroines. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 0-446-67983-6.

• Gamkrelidze, Thomas V.; Ivanov, Vjaceslav V.(2010). Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-081503-0.

• Humbach, Helmut; Faiss, Klauss (2012). Herodotus's Scythians and Ptolemy's Central Asia: Semasiological and Onomasiological Studies. Reichert Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89500-887-0.

• Jaedtke, Wolfgang (2008). Steppenkind: Ein Skythen-Roman (in German). Piper. ISBN 978-3-492-25146-4.

• Johnson, James William (April 1959). "The Scythian: His Rise and Fall". Journal of the History of Ideas. University of Pennsylvania Press. 20 (2): 250–257. doi:10.2307/2707822. JSTOR 2707822.

• Lebedynsky, Iaroslav (2001). Les Scythes (in French). Ed. Errance. ISBN 2877722155.

• Rostovtzeff, Michael (1993). Skythien und der Bosporus (in German). 2. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 3-515-06399-4.

• Torday, Laszlo (1998). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham Academic Press. ISBN 1-900838-03-6.

External links• Scythians at Encyclopædia Iranica