Khalji dynasty

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 11/3/21

I now return to my narrative of the events of Jalalu-d din's reign. In the year 689 H. (1290 A.D.), the Sultan led an army to Rantambhor. Khan-i Jahan his eldest son was then dead, and he appointed his second son Arkali Khan to be his vicegerent at Kilu-ghari in his absence. He took the [BLANK]1 [It is difficult to say what is here intended. The printed text has [x]. One MS. says [x], and the other [x]. Jhain must be Ujjain.] of Jhain, destroyed the idol temples, and broke and burned the idols. He plundered Jhain and Malwa, and obtained great booty, after which his army rested. The Rai of Rantambhor, with his Rawats and followers, together with their wives and children, all took refuge in the fort of Rantambhor. The Sultan wished to invest and take the fort. He ordered manjaniks2 [The word used is "maghribiha" western (engines).] to be erected, tunnels (sabat) to be sunk, and redoubts (gargach) to be constructed, and the siege to be pressed. He arrived from Jhain, carefully reconnoitred the fort, and on the same day returned to Jhain. Next day he called together his ministers and officers, and said that he had intended to invest the fort, to bring up another army, and to levy forces from Hindustan. But after reconnoitring the fort, he found that it could not be taken without sacrificing the lives of many Musulmans * * * and that he did not value the fort so much as the hair of one Musalman. If he took the place and plundered it after the fall of many Muhammadans, the widows and orphans of the slain would stand before him and turn its spoils into bitterness. So he raised the siege, and next day departed for Dehli. When he announced his intention of retreating, Ahmad Chap protested and said. **** The Sultan replied at length. *** He concluded by saying "I am an old man. I have reached the age of eighty years, and ought to prepare for death. My only concern should be with matters that may be beneficial after my decease.'' ***

In the year 691 H. (1292 A.D.), 'Abdu-llah, grandson of the accursed Halu (Hulaku), invaded Hindustan with fifteen tumans of Mughals (150,000!). The Sultan assembled his forces, and marched from Dehli to meet them, with a large and splendid army. When he reached Bar-ram,1 [Briggs says "Beiram," but thinks it an error.] the outposts of the Mughals were descried, and the two armies drew up in face of each other with a river between them. Some few days were passed in arraying their forces, and the advanced parties of the opposing forces had several skirmishes in which the Musulmans were victorious, and made some prisoners, who were conducted to the Sultan. Shortly after the van of the Mughal army crossed the river. The van of the Musulmans hastened to meet them, and a sharp conflict ensued, in which the Musulman forces were victorious. Many Mughals were put to the sword, and one or two commanders of thousands, and several centurions were made prisoners. Negotiations followed, and it was agreed that war was a great evil, and that hostilities should cease. The Sultan and 'Abdu-llah, grandson of Halu the accursed, had an interview. The Sultan called him son, and he addressed the Sultan as father. Presents were exchanged, and after hostilities had ceased, buying and selling went on between the two armies. 'Abdu'llah departed with the Mughal army, but Ulghu, grandson of Changiz Khan, the accursed, with several nobles, commanders of thousands and centurions, resolved to stay in India. They said the creed and became Muhammadans, and a daughter of the Sultan was given in marriage to Ulghu. The Mughals who followed Ulghu, were brought into the city with their wives and children. Provision was made for their support, and houses were provided for them in Kilu-ghari, Ghiyaspur, Indarpat, and Taluka. Their abodes were called Mughalpur. The Sultan continued their allowances for a year or two, but the climate and their city homes did not please them, so they departed with their families to their own country. Some of their principal men remained in India, and received allowances and villages. They mixed with and formed alliances with the Musulmans, and were called "New Musulmans."

Towards the end of the year, the Sultan went to Mandur, reduced it to subjection, plundered the neighbourhood, and returned home. Afterwards he marched a second time to Jhain, and after once more plundering the country, he returned in triumph.

'Alau-d din at this time held the territory of Karra, and with permission of the Sultan he marched to Bhailasan (Bhilsa). He captured some bronze idols which the Hindus worshipped, and sent them on cars with a variety of rich booty as presents to the Sultan. The idols were laid down before the Badaun gate for true believers to tread upon. 'Alau-d din, nephew and son in-law of the Sultan, had been brought up by him. After sending the spoils of Bhailasan to the Sultan, he was made 'Ariz'i mamalik, and received the territory of Oudh in addition to that of Karra. When 'Alau-d din went to Bhailasan (Bhilsa), he heard much of the wealth and elephants of Deogir. He inquired about the approaches to that place, and resolved upon marching thither from Karra with a large force, but without informing the Sultan. He proceeded to Dehli and found the Sultan more kind and generous than ever. He asked for some delay in the payment of the tribute for his territories of Karra and Oudh, saying that he had heard there were countries about Chanderi where peace and security reigned, and where no apprehension of the forces of Dehli was felt. If the Sultan would grant him permission he would march thither, and would acquire great spoil, which he would pay into the royal exchequer, together with the revenues of his territories. The Sultan, in the innocence and trust of his heart, thought that 'Alau-d din was so troubled by his wife and mother-in-law that he wanted to conquer some country wherein he might stay and never return home. In the hope of receiving a rich booty, the Sultan granted the required permission, and postponed the time for the payment of the revenues of Karra and Oudh.

'Alau-d din was on bad terms with his mother in law, Malika-i Jahan, wife of the Sultan, and with his wife, the daughter of the Sultan. He was afraid of the intrigues of the Malika-i Jahan, who had a great ascendancy over her father. He was averse to bringing the disobedience of his wife before the Sultan, and he could not brook the disgrace which would arise from his derogatory position being made public. It greatly distressed him, and he often consulted with his intimates at Karra about going out into the world to make a position for himself. When he made the campaign to Bhailasan, he heard much about the wealth of Deogir. *** He collected three or four thousand horse, and two thousand infantry, whom he fitted out from the revenues of Karra, which had been remitted for a time by the Sultan, and with this force he marched for Deogir. Though he had secretly resolved upon attacking Deogir, he studiously concealed the fact, and represented that he intended to attack Chanderi. Malik 'Alau-l mulk, uncle of the author, and one of the favoured followers of 'Alau-d din, was made deputy of Karra and Oudh in his absence.

'Alau-d din marched to Elichpur, and thence to Ghatilajaura. Here all intelligence of him was lost. Accounts were sent regularly from Karra to the Sultan with vague statements,1 ["Arajif" -- "false rumours,'' but here and elsewhere it seems to rather mean, vague unsatisfactory news.] saying that he was engaged in chastising and plundering rebels, and that circumstantial accounts would be forwarded in a day or two. The Sultan never suspected him of any evil designs, and the great men and wise men of the city thought that the dissensions with his wife had driven him to seek his fortune in a distant land. This opinion soon spread. When 'Alau-d din arrived at Ghati-lajaura, the army of Ram-deo, under the command of his son, had gone to a distance. The people of that country had never heard of the Musulmans; the Mahratta land had never been punished by their armies; no Musulman king or prince had penetrated so far. Deogir was exceedingly rich in gold and silver, jewels and pearls, and other valuables. When Ram-deo heard of the approach of the Muhammadans, he collected what forces he could, and sent them under one of his ranas to Ghati-lajaura. They were defeated and dispersed by 'Alau-d din, who then entered Deogir. On the first day he took thirty elephants and some thousand horses. Ram deo came in and made his submission. 'Alau-d din carried off an unprecedented amount of booty. * * *

In the year 695 H. (1296 A.D.), the Sultan proceeded with an army to the neighbourhood of Gwalior, and stayed there some time. Rumours (ardaif) here reached him that 'Alau-d din had plundered Deogir and obtained elephants and an immense booty, with which he was returning to Karra. The Sultan was greatly pleased, for in the simplicity of his heart he thought that whatsoever his son and nephew had captured, he would joyfully bring to him. To celebrate this success, the Sultan gave entertainments, and drank wine. The news of 'Alau-d din's victory was confirmed by successive arrivals, and it was said that never had so rich a spoil reached the treasury of Dehli. Afterwards the Sultan held a private council, to which he called some of his most trusty advisers * * * and consulted whether it would be advisable to go to meet 'Alau-d din or to return to Dehli. Ahmad Chap, Naib-barbak, one of the wisest men of the day, spoke before any one else, and said, "Elephants and wealth when held in great abundance are the cause of much strife. Whoever acquires them becomes so intoxicated that he does not know his hands from his feet. 'Alau-d din is surrounded by many of the rebels and insurgents who supported Malik Chhaju. He has gone into a foreign land without leave, has fought battles and won treasure. The wise have said 'Money and strife; strife and money' — that is the two things are allied to each other. * * * My opinion is that we should march with all haste towards Chanderi to meet 'Alau-d din and intercept his return. When he finds the Sultan's army in the way, he must necessarily present all his spoils to the throne whether he likes it or not. The Sultan may then take the silver and gold, the jewels and pearls, the elephants and horses, and leave the other booty to him and his soldiers. His territories also should be increased, and he should be carried in honour to Dehli." *** The Sultan was in the grasp of his evil angel, so he heeded not the advice of Ahmad Chap * * * but said "what have I done to 'Alau-d din that he should turn away from me, and not present his spoils?" The Sultan also consulted Malik Fakhru-d din Kuchi (and other nobles). The Malik was a bad man; he knew that what Ahmad Chap had said was right, but he saw that his advice was displeasing to the Sultan, so he advised * * * that the Sultan should return to Dehli to keep the Ramazan. * * *

The guileless heart of the Sultan relied upon the fidelity of 'Alau-d din, so he followed the advice of Fakhru-d din Kuchi, and returned to Kilu-ghari. A few days after intelligence arrived that 'Alau-d din had returned with his booty to Karra. 'Alau-d din addressed a letter to the Sultan announcing his return with so much treasure and jewels and pearls, and thirty-one elephants, and horses, to be presented to his majesty, but that he had been absent on campaign without leave more than a twelve- month, during which no communications had passed between him and the Sultan, and he did not know, though he feared the machinations of his enemies during his absence. If the Sultan would write to reassure him, he would present himself with his brave officers and spoils before the throne. Having despatched this deceitful letter, he immediately prepared for an attack upon Lakhnauti. He sent Zafar Khan into Oudh to collect boats for the passage of the Saru, and, in consultation with his adherents, he declared that as soon as he should hear that the Sultan had marched towards Karra, he would leave it with his elephants and treasure, with his soldiers and all their families, and would cross the Saru and march to Lakhnauti, which he would seize upon, being sure that no army from Dehli would follow him there. * * * No one could speak plainly to the Sultan, for if any one of his confidants mentioned the subject he grew angry, and said they wanted to set him against his son. He wrote a most gracious and affectionate letter with his own hand, and sent it by the hands of some of his most trusted officers. When these messengers arrived at Karra, they saw that all was in vain, for that 'Alau-d din and all his army were alienated from the Sultan. They endeavoured to send letters informing the Sultan, but they were unable to do so in any way. Meanwhile the rains came on, and the roads were all stopped by the waters. Almas Beg, brother of 'Alau-d din, and like him a son-in-law of the Sultan, held the office of Akhur-bak (Master of the horse). He often said to the Sultan "People frighten my brother, and I am afraid that in his shame and fear of your majesty he will poison or drown himself." A few days afterwards 'Alau-d din wrote to Almas Beg, saying that he had committed an act of disobedience, and always carried poison in his handkerchief. If the Sultan would travel jarida (i.e. speedily, with only a small retinue), to meet him, and would take his hand, he should feel re-assured; if not, he would either take poison or would march forth with his elephants and treasures to seek his fortune in the world. His expectation was that the Sultan would desire to obtain the treasure, and would come with a scanty following to Karra, when it would be easy to get rid of him.*** Almas Beg showed to the Sultan the letter which he had received from his brother, and the Sultan was so infatuated that he believed this deceitful and treacherous letter. Without further consideration he ordered Almas Khan to hasten to Karra, and not to let his brother depart, promising to follow with all speed. Almas Beg took a boat and reached Karra in seven or eight days. When he arrived, 'Alau-d din ordered drums of joy to be beaten, saying that now all his apprehensions and fears were removed.

The crafty counsellors of 'Alau-d din, whom he had promoted to honours, advised the abandonment of his designs upon Lakhnauti, saying that the Sultan, coveting the treasure and elephants, had become blind and deaf, and had set forth to see him in the midst of the rainy season — adding, "after he comes, you know what you ought to do." The destroying angel was close behind the Sultan, he had no apprehension, and would listen to no advice. He treated his advisers with haughty disdain, and set forth with a few personal attendants, and a thousand horse from Kilu-ghari. He embarked in a boat at Dhamai, and proceeded towards Karra. Ahmad Chap, who commanded the army, was ordered to proceed by land. It was the rainy season, and the waters were out. On the 15th Ramazan, the Sultan, arrived at Karra, on the hither side of the Ganges.

'Alau-d din and his followers had determined on the course to be adopted before the Sultan arrived. He had crossed the river with the elephants and treasure, and had taken post with his forces between Manikpur and Karra, the Ganges being very high. When the royal ensign came in sight he was all prepared, the men were armed, and the elephants and horses were harnessed. 'Alau-d din sent Almas Beg in a small boat to the Sultan, with directions to use every device to induce him to leave behind the thousand men he had brought with him, and to come with only a few personal attendants. The traitor Almas Beg, hastened to the Sultan, and perceived several boats full of horsemen around him. He told the Sultan that his brother had left the city, and God only knew where he would have gone to if he, Almas Beg, had not been sent to him. If the Sultan did not make more haste to meet him he would kill himself, and his treasure would be plundered. If his brother were to see these armed men with the Sultan he would destroy himself. The Sultan accordingly directed that the horsemen and boats should remain by the side of the river, whilst he, with two boats and a few personal attendants and friends, passed over to the other side. When the two boats had started, and the angel of destiny had come still nearer, the traitor, Almas Beg, desired the Sultan to direct his attendants to lay aside their arms, lest his brother should see them as they approached nearer, and be frightened. The Sultan, about to become a martyr, did not detect the drift of this insidious proposition, but directed his followers to disarm. As the boats reached mid-stream, the army of 'Alau-d din was perceived all under arms, the elephants and horses harnessed, and in several places troops of horsemen ready for action. When the nobles who accompanied the Sultan saw this, they knew that Almas Beg had by his plausibility brought his patron into a snare, and they gave themselves up for lost. * * * Malik Khuram wakildar asked * * * what is the meaning of all this? and Almas Beg, perceiving that his treachery was detected, said his brother was anxious that his army should pay homage to his master.

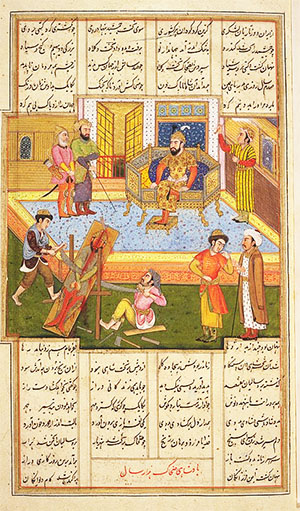

The Sultan was so blinded by his destiny, that although his own eyes saw the treachery, he would not return; but he said to Almas Beg, "I have come so far in a little boat to meet your brother, cannot he, and does not his heart induce him to advance to meet me with due respect." The traitor replied, "My brother's intention is to await your majesty at the landing place, with the elephants and treasure and jewels, and there to present his officers." *** The Sultan trusting implicitly in them who were his nephews, sons-in-law, and foster-children, did not awake and detect the obvious intention. He took the Kuran and read it, and proceeded fearless and confiding as a father to his sons. All the people who were in the boat with him saw death plainly before them, and began to repeat the chapter appropriate to men in sight of death. The Sultan reached the shore before afternoon prayer, and disembarked with a few followers. 'Alau-d din advanced to receive him, he and all his officers showing due respect. When he reached the Sultan he fell at his feet, and the Sultan treating him as a son, kissed his eyes and cheeks, stroked his beard, gave him two loving taps upon the cheek, and said "I have brought thee up from infancy,1 [The Sultan's exact words are expressive enough, but are somewhat too precise and familiar for European taste.[!!!]] why art thou afraid of me?" **** The Sultan took 'Alau-d din's hand, and at that moment the stony-hearted traitor gave the fatal signal. Muhammad Salim, of Samana, a bad fellow of a bad family, struck at the Sultan with a sword, but the blow fell short and cut his own hand. He again struck and wounded the Sultan, who ran towards the river, crying, "Ah thou villian, 'Alau-d din! what hast thou done?" Ikhtiyaru-d din Hud ran after the betrayed monarch, threw him down, and cut off his head, and bore it dripping with blood to 'Alau-d din. **** Some of those persons who accompanied the Sultan had landed, and others remained in the boats, but all were slain. Villainy and treachery, and murderous feelings, covetousness and desire of riches, thus did their work.2 [The writer goes on condemning the murder in strong terms.] ****

The murder was perpetrated on the 17th Ramazan, and the venerable head of the Sultan was placed on a spear and paraded about. When the rebels returned to Karra-Manikpur it was also paraded there, and was afterwards sent to be exhibited in Oudh. **** While the head of the murdered sovereign was yet dripping with blood, the ferocious conspirators brought the royal canopy and elevated it over the head of 'Alau-d din. Casting aside all shame, the perfidious and graceless wretches caused him to be proclaimed king by men who rode about on elephants. Although these villains were spared for a short time, and 'Alau-d din for some years, still they were not forgotten, and their punishments were only suspended. At the end of three or four years Ulugh Khan (Almas Beg), the deceiver, was gone, so was Nusrat Khan, the giver of the signal, so also was Zafar Khan, the breeder of the mischief, my uncle, 'Alau-l Mulk, kotwal, and *** and ***. The hell-hound Salim, who struck the first blow, was a year or two afterwards eaten up with leprosy. Ikhtiyaru-d din, who cut off the head, very soon went mad, and in his dying ravings cried that Sultan Jalalu-d din stood over him with a naked sword, ready to cut off his head. Although 'Alau-d din reigned successfully for some years, and all things prospered to his wish, and though he had wives and children, family and adherents, wealth and grandeur, still he did not escape retribution for the blood of his patron. He shed more innocent blood than ever Pharaoh was guilty of. Fate at length placed a betrayer in his path, by whom his family was destroyed, *** and the retribution which fell upon it never had a parallel even in any infidel land. ***

When intelligence of the murder of Sultan Jalalu-d din reached Ahmad Chap, the commander of the army, he returned to Dehli. The march through the rain and dirt had greatly depressed and shaken the spirits of the men, and they went to their homes. The Malika-i Jahan, wife of the late Sultan, was a woman of determination, but she was foolish and acted very imprudently. She would not await the arrival from Multan of Arkali Khan, who was a soldier of repute, nor did she send for him. Hastily and rashly, and without consultation with any one, she placed the late Sultan's youngest son, Ruknu-d din Ibrahim, on the throne. He was a mere lad, and had no knowledge of the world. With the nobles, great men, and officers she proceeded from Kilu-ghari to Dehli, and, taking possession of the green palace, she distributed offices and fiefs among the maliks and amirs who were at Dehli, and began to carry on the government, receiving petitions and issuing orders. When Arkali Khan heard of his mother's unkind and improper proceedings, he was so much hurt that he remained at Multan, and did not go to Dehli. During the life of the late Sultan there had been dissensions between mother and son, and when 'Alau-d din, who remained at Karra, was informed of Arkali Khan's not coming to Dehli, and of the opposition of the Malika-i Jahan, he saw the opportunity which this family quarrel presented. He rejoiced over the absence of Arkali Khan, and set off for Dehli at once, in the midst of the rains, although they were more heavy than any one could remember. Scattering gold and collecting followers, he reached the Jumna. He then won over the maliks and amirs by a large outlay of money, and those unworthy men, greedy for the gold of the deceased, and caring nothing for loyalty or treachery, deserted the Malika-i Jahan and Ruknu-d din and joined 'Alau-d din. Five months after starting, 'Alau-d din arrived with an enormous following within two or three kos of Dehli. The Malika-i Jahan and Ruknu-d din Ibrahim then left Dehli and took the road to Multan. A few nobles, faithful to their allegiance, left their wives and families and followed them to Multan. Five months after the death of Jalalu-d din at Karra, 'Alau-d din arrived at Dehli and ascended the throne. He scattered so much gold about that the faithless people easily forgot the murder of the late Sultan, and rejoiced over his accession. His gold also induced the nobles to desert the sons of their late benefactor, and to support him. * * *

Iskandar-i sani Sultanu-l'azam 'Alaud-d dunya wau-d din Muhammad Shah Tughlik.

Sultan 'Alau-d din ascended the throne in the year 695 H. (1296 A.D.). He gave to his brother the title Ulugh Khan, to Malik Nusrat Jalesari that of Nusrat Khan, to Malik Huzabbaru-d din t hat of Zafar Khan, and to Sanjar, his wife's brother, who was amir-i majlis, that of Alp Khan. He made his friends and principal supporters amirs, and the amirs he promoted to be maliks [a chief or leader (as in a village) in parts of the subcontinent of India.]. Every one of his old adherents he elevated to a suitable position, and to the Khans, maliks, and amirs he gave money, so that they might procure new horses and fresh servants. Enormous treasure had fallen into his hands, and he had committed a deed unworthy of his religion and position, so he deemed it politic to deceive the people, and to cover the crime by scattering honours and gifts upon all classes of people.

He set out on his journey to Dehli, but the heavy rains and the mire and dirt delayed his march. His desire was to reach the capital after the rising of Canopus, as he felt very apprehensive of the late Sultan's second son, Arkali Khan, who was a brave and able soldier. News came from Dehli that Arkali Khan had not come, and 'Alau-d din considered this absence as a great obstacle to his (rival's) success. He knew that Ruknu-d din Ibrahim could not keep his place upon the throne, for the royal treasury was empty and he had not the means of raising new forces, 'Alau-d din accordingly lost no time, and pressed on to Dehli, though the rains were at their height. In this year, through the excessive rain, the Ganges and the Jumna became seas, and every stream swelled into a Ganges or a Jumna; the roads also were obstructed with mud and mire. At such a season 'Alau-d din started from Karra with his elephants, his treasures, and his army. His khans, maliks, and amirs were commanded to exert themselves strenuously in enlisting new horsemen, and in providing of all things necessary without delay. They were also ordered to shower money freely around them, so that plenty of followers might be secured. As he was marching to Dehli a light and moveable manjanik was made. Every stage that they marched five mans of gold stars1 [[x]] were placed in this manjanik, which were discharged among the spectators from the front of the royal tent. People from all parts gathered to pick up "the stars," and in the coarse of two or three weeks the news spread throughout all the towns and villages of Hindustan that 'Alau-d din was marching to take Dehli, and that he was scattering gold upon his path and enlisting horsemen and followers without limit. People, military and unmilitary, flocked to him from every side, so that when he reached Badaun, notwithstanding the rains, his force amounted to fifty-six thousand horse and sixty thousand foot. ****

When 'Alau-d din arrived at Baran, he placed a force under Zafar Khan, with orders to march by way of Kol, and to keep pace while he himself proceeded by way of Badaun and Baran. Taju-d din Kuchi, and ** and ** other maliks and amirs who were sent from Dehli to oppose the advancing forces, came to Baran and joined 'Alau-d din, for which they received twenty, thirty, and some even fifty mans of gold. All the soldiers who were under these noblemen received each three hundred tankas, and the whole following of the late Jalala-d din was broken up. The nobles who remained in Dehli wavered, while those who had joined 'Alau-d din loudly exclaimed that the people of Dehli maligned them, charging them with disloyalty, with having deserted the son of their patron and of having joined themselves to his enemy. They complained that their accusers were unjust, for they did not see that the kingdom departed from Jalalu-d din on the day when he wilfully and knowingly, with his eyes wide open, left Dehli and went to Karra, jeopardizing his own head and that of his followers. What else could they do but join 'Alau-d din?

When the maliks and amirs thus joined 'Alau-d din the Jalali party broke up. The Malika-i Jahan, who was one of the silliest of the silly, then sent to Multan for Arkali Khan. She wrote to this effect — "I committed a fault in raising my youngest son to the throne in spite of you. None of the maliks and amirs heed him, and most of them have joined 'Alau-d din. The royal power has departed from our hands. If you can, come to us speedily, take the throne of your father and protect us. You are the elder brother of the lad who was placed upon the throne, and are more worthy and capable of ruling. He will acknowledge his inferiority. I am a woman, and women are foolish. I committed a fault, but do not be offended with your mother's error. Come and take the kingdom of your father. If you are angry and will not do so, 'Alau-d din is coming with power and state; he will take Dehli, and will spare neither me nor you." Arkali Khan did not come, but wrote a letter of excuse to his mother, saying, "Since the nobles and the army have joined the enemy, what good will my coming do?" When 'Alau-d din heard that Arkali Khan would not come, he ordered the drums of joy to be beaten.

'Alau-d din had no boats, and the great height of the Jumna delayed his passage. While he was detained on the banks of the river, Canopus rose, and the waters as usual decreased. He then transported his army across at the ferries, and entered the plain of Judh.1 [The print has "Judh." One MS. writes "Khud" t he other omits the name.] Ruknu-d din Ibrahim went out of the city in royal state with such followers as remained to oppose 'Alau-d din, but in the middle of the night all the left wing of his army deserted to the enemy with great uproar. Ruknu-d din Ibrahim turned back, and at midnight he caused the Badaun gate (of Dehli) to be opened. He took some bags of gold tankas from the treasury, and some horses from the stables. He sent his mother and females on in front, and in the dead of the night he left the city by the Ghazni gate, and took the road to Multan. Malik Kutbu-d din 'Alawi, with the sons of Malik Ahmad Chap Turk, furnished the escort, and proceeded with him and the Malika-i Jahan to Multan. Next day 'Alau-d din marched with royal state and display into the plain of Siri,2 [See Cunningham's Archaeological Report for 1862-3, page 38.] where he pitched his camp. The throne was now secure, and the revenue officers, and the elephant keepers with their elephants, and the kotwah with the keys of the forts, and the magistrates and the chief men of the city came out to 'Alau-d din, and a new order of things was established. His wealth and power were great; so whether individuals paid their allegiance or whether they did not, mattered little, for the khutba was read and coins were struck in his name.

Towards the end of the year 695 H. (1296) 'Alau-d din entered Dehli in great pomp and with a large force. He took his seat upon the throne in the daulat-khana-i julus, and proceeded to the Kushk'i l'al (red palace), where he took up his abode. The treasury of 'Alau-d din was well filled with gold, which he scattered among the people, purses and bags filled with tankas and jitals were distributed, and men gave themselves up to dissipation and enjoyment. [Public festivities followed.] 'Alau-d din, in the pride of youth, prosperity, and boundless wealth, proud also of his army and his followers, his elephants and his horses, plunged into dissipation and pleasure. The gifts and honours which he bestowed obtained the good will of the people. Out of policy he gave offices and fiefs to the maliks and amirs of the late Sultan. Khwaja Khatir, a minister of the highest reputation, was made wazir, etc., etc. *** Malik 'Alau-l Mulk, uncle of the author, was appointed to Karra and Oudh, and Muyidu-l Mulk, the author's father, received the deputyship and khwajagi of Baran. * * * People were so deluded by the gold which they received, that no one ever mentioned the horrible crime which the Sultan had committed, and the hope of gain left them no care for anything else. ****

After 'Alau-d din had ascended the throne, the removal of the late king's sons engaged his first attention. Ulugh Khan and Zafar Khan, with other maliks and amirs, were sent to Multan with thirty or forty thousand horse. They besieged that place for one or two months. The kotwal and the people of Multan turned against the sons of Jalalu-d din, and some of the amirs came out of the city to Ulugh Khan and Zafar Khan. The sons of the late Sultan then sent Shaikhu-l Islam Shaikh Ruknu-d din to sue for safety from Ulugh Khan, and received his assurances. The princes then went out with the Shaikh and their amirs to Ulugh Khan. He received them with great respect and quartered them near his own dwelling. News of the success was sent to Dehli. There the drums were beaten. Kabas1 [Booths erected for the distribution of food and drink on festive occasions.] were erected, and the despatch was read from the pulpit and was circulated in all quarters. The amirs of Hindustan then became submissive to 'Alau-d din, and no rival remained. Ulugh Khan and Zafar Khan returned triumphant towards Dehli, carrying with them the two sons of the late Sultan, both of whom had received royal canopies. Their maliks and amirs were also taken with them. In the middle of their journey they were met by Nusrat Khan, who had been sent from Dehli, and the two princes, with Ulghu Khan, son in law of the late Sultan, and Ahmad Chap, Naib-amir-i hajib, were all blinded. Their wives were separated from them, and all their valuables and slaves and maids, in fact everything they had was seized by Nusrat Khan. The princes1 [Both the MSS. say "sons," while the print incorrectly uses the singular.] were sent to the fort of Hansi, and the sons of Arkali Khan were all slain. Malika-i Jahan, with their wives, and Ahmad Chap were brought to Dehli and confined in his house.

In the second year of the reign Nusrat Khan was made wazir. 'Alau-l Mulk, the author's uncle, was summoned from Karra, and came with the maliks and amirs and one elephant, bringing the treasure which 'Alau-d din had left there. He was become exceedingly fat and inactive, but he was selected from among the nobles to be kotwal of the city. In this year also the property of the maliks and amirs of the late Sultan was confiscated, and Nusrat Khan exerted himself greatly in collecting it. He laid his hands upon all that he could discover, and seized upon thousands, which he brought into the treasury. Diligent inquiry was made into the past and present circumstances of the victims. In this same year, 696 H. (1296), the Mughals crossed the Sind and had come into the country. Ulugh Khan and Zafar Khan were sent with a large force, and with the amirs of the late and the present reign, to oppose them. The Musulman army met the accursed foe in the vicinity of Jalandhar2 [So in the print; but the MSS. have "Jadawa o Manjur" and "Jarat-mahud."] and gained a victory. Many were slain or taken prisoners, and many heads were sent to Dehli. The victory of Multan and the capture of the two princes had greatly strengthened the authority of 'Alau-d din; this victory over the Mughals made it still more secure. * * * The maliks of the late king, who deserted their benefactor and joined 'Alau-d din, and received gold by mans and obtained employments and territories, were all seized in the city and in the army, and thrown into forts as prisoners. Some were blinded and some were killed. The wealth which they had received from 'Alau-d din, and their property, goods, and effects were all seized. Their houses were confiscated to the Sultan, and their villages were brought under the public exchequer. Nothing was left to their children; their retainers and followers were taken in charge by the amirs who supported the new regime, and their establishments were overthrown. Of all the amirs of the reign of Jalalu-d din, three only were spared by 'Alau-d din. *** These three persons had never abandoned Sultan Jalalu-d din and his sons, and had never taken money from Sultan 'Alau-d din. They alone remained safe, but all the other Jalali nobles were cut up root and branch. Nusrat Khan, by his fines and confiscations, brought a kror of money into the treasury.

At the beginning of the third year of the reign, Ulugh Khan and Nusrat Khan, with their amirs, and generals, and a large army, marched against Gujarat. They took and plundered Nahrwala and all Gujarat. Kuran, Rai of Gujarat, fled from Nahrwala and went to Ram Deo of Deogir. The wives and daughters, the treasure and elephants of Rai Karan, fell into the hands of the Muhammadans. All Gujarat became a prey to the invaders, and the idol which, after the victory of Sultan Mahmud and his destruction of (the idol) Manat, the Brahmans had set up under the name of Somnath, for the worship of the Hindus, was removed and carried to Dehli, where it was laid down for people to tread upon. Nusrat Khan proceeded to Kambaya1 [The printed text has [x], but there can be no doubt that Cambay is the place.] (Cambay), and levied large quantities of jewels and precious articles from the merchants of that place, who were very wealthy. He also took from his master (a slave afterwards known as) Kafur Hazar-dinari, who was made Malik-naib, and whose beauty captivated 'Alau-d din. Ulugh Khan and Nusrat Khan returned with great booty; but on their way they provoked their soldiers to revolt by demanding from them a fifth of their spoil, and by instituting inquisitorial inquiries about it. Although the men made returns (of the amount), they would not believe them at all, but demanded more. The gold and silver, and jewels and valuables, which the men had taken, were all demanded, and various kinds of coercion were employed. These punishments and prying researches drove the men to desperation. In the army there were many amirs and many horsemen who were "new Muhammadans." They held together as one man, and two or three thousand assembled and began a disturbance. They killed Malik A'zzu-d din, brother of Nusrat Khan, and amir-i hajib of Ulugh Khan, and proceeded tumultuously to the tent of Ulugh Khan. That prince escaped, and with craft and cleverness reached the tent of Nusrat Khan; but the mutineers killed a son of the Sultan's sister, who was asleep in the tent, whom they mistook for Ulugh Khan. The disturbance spread through the whole army, and the stores narrowly escaped being plundered. But the good fortune of the Sultan prevailed, the turmoil subsided, and the horse and foot gathered round the tent of Nusrat Khan. The amirs and horsemen of "the new Musulmans" dispersed; those who had taken the leading parts in the disturbance fled, and went to join the Rais and rebels. Further inquiries about the plunder were given up, and Ulugh Khan and Nusrat Khan returned to Dehli with the treasure, and elephants, and slaves, and spoil, which they had taken in Gujarat.

When intelligence of this outbreak of the new Muhammadans reached Dehli, the crafty cruelty which had taken possession of 'Alau-d din induced him to order that the wives and children of all the mutineers, high and low, should be cast into prison. This was the beginning of the practice of seizing women and children for the faults of men. Up to this time no hand had ever been laid upon wives and children on account of men's misdeeds. At this time also another and more glaring act of tyranny was committed by Nusrat Khan, the author of many acts of violence at Dehli. His brother had been murdered, and in revenge he ordered the wives of the assassins to be dishonoured and exposed to most disgraceful treatment; he then handed them over to vile persons to make common strumpets of them. The children he caused to be cut to pieces on the heads of their mothers. Outrages like this are practised in no religion or creed. These and similar acts of his filled the people of Dehli with amazement and dismay, and every bosom trembled.

In the same year that Ulugh Khan and Nusrat Khan were sent to Gujarat, Zafar Khan was sent to Siwistan, which Saldi,1 [So in the print, and supported by one MS. The other has "Sadari."] with his brother and other Mughals, had seized upon. Zafar Khan accordingly proceeded to Siwistan with a large army, and besieged the fort of Siwistan, which he took with the axe and sword, spear and javelin, without using either Westerns (maghribe), manjaniks or balistas ('aradah), and without resorting to mines (sabat), mounds (pashib), or redoubts (gargaj). This fort had been taken by the Mughals, and they maintained such a continuous discharge of arrows that no bird could fly by. For all this Zafar Khan took it with the axe and sword. Saldi and his brother, with all the Mughals and their wives and children, were taken prisoners, and sent in chains to Dehli. This victory inspired awe of Zafar Khan in every heart, and the Sultan also looked askance at him in consequence of his fearlessness, generalship, and intrepidity, which showed that a Rustam had been born in India. Ulugh Khan, the Sultan's brother, saw that he had been surpassed in bravery and strategy, and so conceived a hatred and jealousy of Zafar Khan. In the same year he (Zafar Khan) received the fief of Samana, and as he had become famous the Sultan, who was very jealous, began to revolve in his mind what was best to be done. Two modes of dealing with him seemed open for the Sultan's choice. One was to send him, with a few thousand horse, to Lakhnauti to take that country, and leave him there to supply elephants and tribute to the Sultan; the other was to put him out of the way by poison or by blinding.

At the end of this year Katlagh Khwaja, son of the accursed Zud,1 [Firishta (vol. i., p. 329) says "son of Amir Daud Khan, king of Mawarau-n nahr."] with twenty tumans of Mughals, resolved upon the invasion of Hindustan. He started from Mawarau-n Nahr, and passing the Indus with a large force he marched on to the vicinity of Dehli. In this campaign Dehli was the object of attack, so the Mughals did not ravage the countries bordering on their march, nor did they attack the forts. * * * Great anxiety prevailed in Dehli, and the people of the neighbouring villages took refuge within its walls. The old fortifications had not been kept in repair, and terror prevailed, such as never before had been seen or heard of. All men, great and small, were in dismay. Such a concourse had crowded into the city that the streets and markets and mosques could not contain them. Everything became very dear. The roads were stopped against caravans and merchants, and distress fell upon the people.

The Sultan marched out of Dehli with great display and pitched his tent in Siri. Maliks, amirs, and fighting men were summoned to Dehli from every quarter. At that time the anther's uncle, 'Alau-l Mulk, one of the companions and advisers of the Sultan, was kotwal of Dehli, and the Sultan placed the city, his women and treasure, under his charge. **** 'Alau-l Mulk went out to Siri to take leave of the Sultan, and in private consultation with him [advised a temporising policy.] The Sultan listened and commended his sincerity. He then called the nobles together and said * * * yon have heard what 'Alau-l Malk has urged * * * now hear what I have to say. *** If I were to follow your advice, to whom could I show my face? how could I go into my harem? of what account would the people hold me? and where would be the daring and courage which is necessary to keep my turbulent people in submission? Come what may I will to-morrow march into the plain of Kili.*** 'Alau-d din marched from Siri to Kili and there encamped. Katlagh Khwaja, with the Mughal army, advanced to encounter him. In no age or reign had two such vast armies been drawn up in array against each other, and the sight of them filled all men with amazement. Zafar Khan, who commanded the right wing, with the amirs who were under him, drew their swords and fell upon the enemy with such fury that the Mughals were broken and forced to fall back. The army of Islam pursued, and Zafar Khan, who was the Rustam of the age and the hero of the time, pressed after the retreating foe, cutting them down with the sword and mowing off their heads. He kept up the pursuit for eighteen kos, never allowing the scared Mughals to rally. Ulugh Khan commanded the left wing, which was very strong, and had under him several distinguished amirs. Through the animosity which he bore to Zafar Khan he never stirred to support him.

Targhi, the accursed, had been placed in ambush with his tuman. His Mughals mounted the trees and could not see any horse moving up to support Zafar Khan. When Targhi ascertained that Zafar Khan had gone so far in pursuit of the Mughals without any supporting force in his rear, he marched after Zafar Khan, and, spreading out his forces on all sides, he surrounded him as with a ring, and pressed him with arrows. Zafar Khan was dismounted. The brave hero then drew his arrows from the quiver and brought down a Mughal at every shaft. At this juncture, Katlagh Khwaja sent him this message, "Come with me and I will take thee to my father, who will make thee greater than the king of Dehli has made thee." Zafar Khan heeded not the offer, and the Mughals saw that he would never be taken alive, so they pressed in upon him on every side and despatched him. The amirs of his force were all slain, his elephants were wounded, and their drivers killed. The Mughals thus, on that day, obtained the advantage, but the onslaught of Zafar Khan had greatly dispirited them. Towards the end of the night they retreated, and marched to a distance of thirty kos from Dehli. They then continued their retreat by marches of twenty kos, without resting, until they reached their own confines. The bravery of Zafar Khan was long remembered among the Mughals, and if their cattle refused to drink they used to ask if they saw Zafar Khan.1 [See D'Ohsson Hist. des Mongols, iv., 560.] No such army as this has ever since been seen in hostile array near Dehli. 'Alau-d din returned from Kili, considering that he had won a great victory: the Mughals had been put to flight, and the brave and fearless Zafar Khan had been got rid of without disgrace.

In the third year of his reign 'Alaud-d din had little to do beyond attending to his pleasures, giving feasts, and holding festivals. One success followed another; despatches of victory came in from all sides; every year he had two or three sons born, affairs of State went on according to his wish and to his satisfaction, his treasury was overflowing, boxes and caskets of jewels and pearls were daily displayed before his eyes, he had numerous elephants in his stables and seventy thousand horses in the city and environs, two or three regions were subject to his sway, and he had no apprehension of enemies to his kingdom or of any rival to his throne. All this prosperity intoxicated him. Vast desires and great aims, far beyond him, or a hundred thousand like him, formed their germs in his brain, and he entertained fancies which had never occurred to any king before him. In his exaltation, ignorance, and folly, he quite lost his head,2 [Lit, "hands and feet." Here, and occasionally elsewhere, I have been obliged to prune the exuberant eloquence of the author.] forming the most impossible schemes and nourishing the most extravagant desires. He was a man of no learning and never associated with men of learning. He could not read or write a letter. He was bad tempered, obstinate, and hard-hearted, but the world smiled upon him, fortune befriended him, and his schemes were generally successful, so he only became the more reckless and arrogant.

During the time that he was thus exalted with arrogance and presumption, he used to speak in company about two projects that he had formed, and would consult with his companions and associates upon the execution of them. One of the two schemes which he used to debate about he thus explained, ''God Almighty gave the blessed Prophet four friends, through whose energy and power the Law and Religion were established, and through this establishment of law and religion the name of the Prophet will endure to the day of judgment. Every man who knows himself to be a Musulman, and calls himself by that name, conceives himself to be of his religion and creed. God has given me also four friends, Ulugh Khan, Zafar Khan, Nusrat Khan, and Alp Khan, who, through my prosperity, have attained to princely power and dignity. If I am so inclined, I can, with the help of these four friends, establish a new religion and creed; and my sword, and the swords of my friends, will bring all men to adopt it. Through this religion, my name and that of my friends will remain among men to the last day like the names of the Prophet and his friends." *** Upon this subject he used to talk in his wine parties, and also to consult privately with his nobles. * * * His second project he used to unfold as follows: "I have wealth, and elephants, and forces, beyond all calculation. My wish is to place Dehli in charge of a vicegerent, and then I will go out myself into the world, like Alexander, in pursuit of conquest, and subdue the whole habitable world." Over-elated with the success of some few projects, he caused himself to be entitled "the second Alexander" in the khutba and on his coins. In his convivial parties he would vaunt, "Every region that I subdue I will intrust to one of my trusty nobles, and then proceed in quest of another. Who is he that shall stand against me?" His companions, although they saw his * * * folly and arrogance, were afraid of his violent temper, and applauded him. * * * These wild projects became known in the city; some of the wise men smiled, and attributed them to his folly and ignorance; others trembled, and said that such riches had fallen into the hands of a Pharaoh who had no knowledge or sense. * * *

(cont'd below)