History of the Indo-Greek Kingdomby Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/22/21

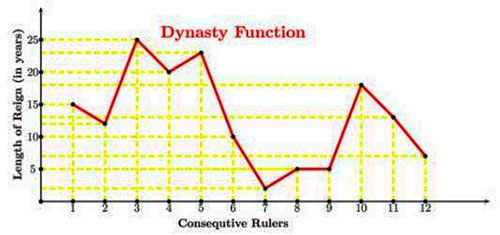

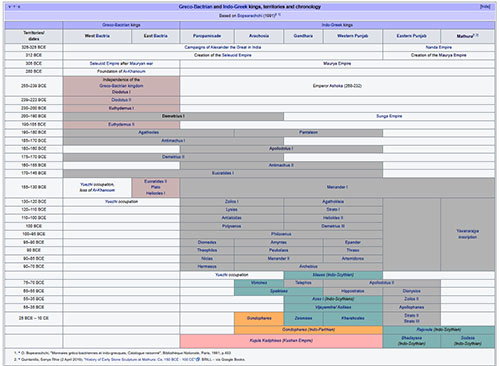

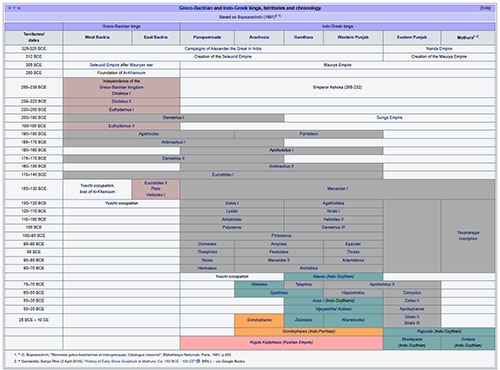

The History of the Indo-Greek Kingdom covers a period from the 2nd century BCE [200-101 B.C.] to the beginning of the 1st century CE in northern and northwestern India. There were over 30 Indo-Greek kings, often in competition on different territories. Many of them are only known through their coins.

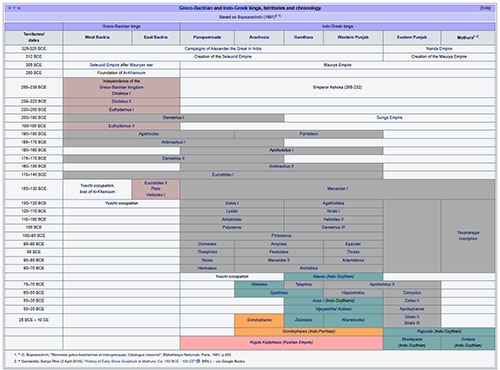

Many of the dates, territories, and relationships between Indo-Greek kings are tentative and essentially based on numismatic analysis (find places, overstrikes, monograms, metallurgy, styles), a few Classical writings, and Indian writings and epigraphic evidence.

The following list of kings, dates and territories after the reign of Demetrius is derived from the latest and most extensive analysis on the subject, by Osmund Bopearachchi and R. C. Senior.

The invasion of northern India, and the establishment of what would be known as the "Indo-Greek kingdom", started around 200 BCE when Demetrius, son of the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus I, led his troops across the Hindu Kush. Apollodotus, may have made advances in the south, while Menander (Reign: 165/155–130 BC), led later invasions further east.

The Periplus explains that coins of the Indo-Greek king Menander I were current in Barigaza.

Location of Barygaza in India

Location of Barygaza in IndiaTo the present day ancient drachmae are current in Barygaza, coming from this country, bearing inscriptions in Greek letters, and the devices of those who reigned after Alexander, Apollodorus [sic] and Menander.— Periplus, §47

-- Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, by Wikipedia

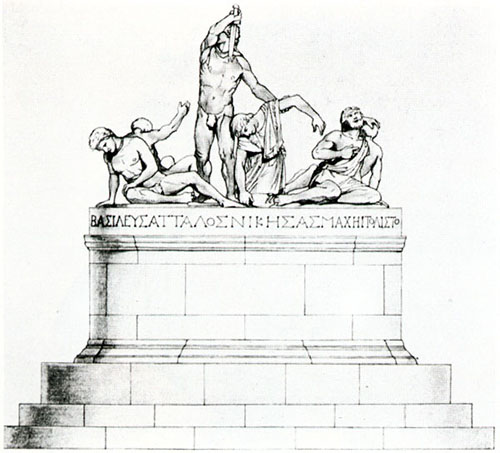

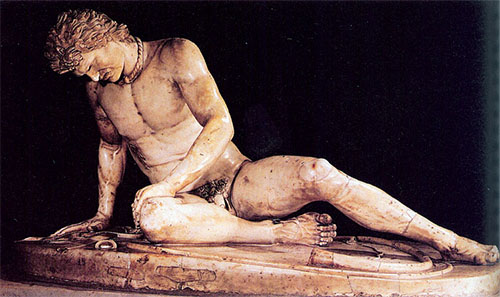

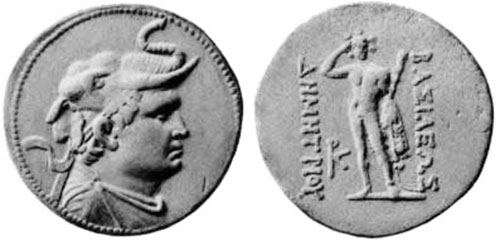

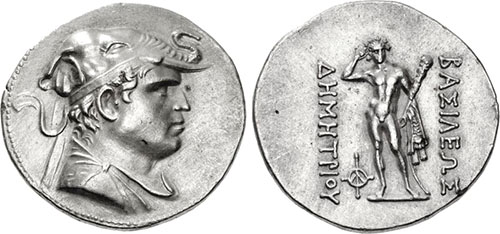

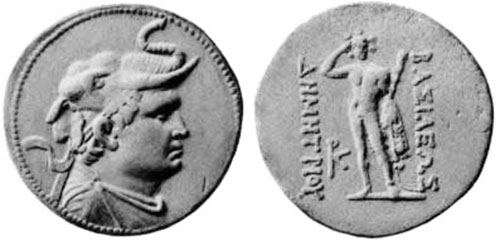

Following his conquests, Demetrius received the title ανικητος ("Anicetus", lit. invincible), a title never given to any king before.[1]

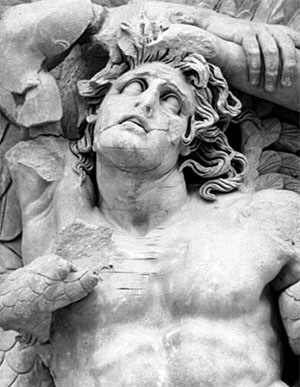

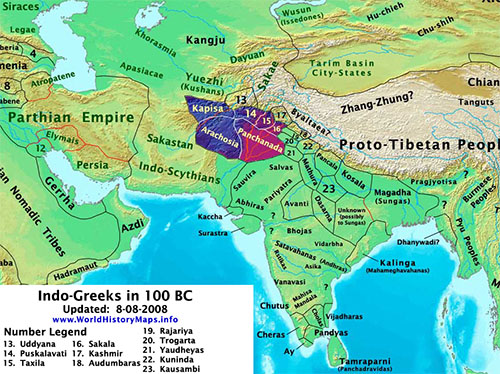

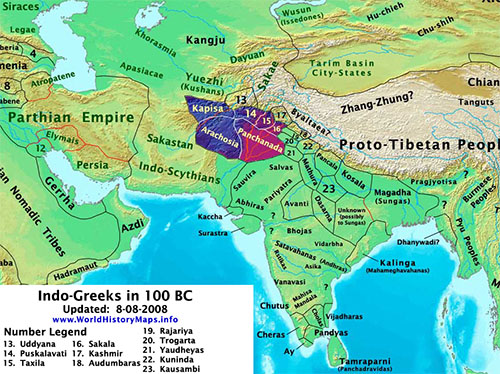

Indo-Greek Kingdoms in 100 BCE.

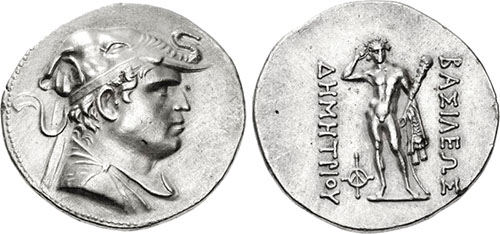

Indo-Greek Kingdoms in 100 BCE. The founder of the Indo-Greek Kingdom Demetrius I "the Invincible" (205–171 BCE), wearing the scalp of an elephant, symbol of his conquests in India.

The founder of the Indo-Greek Kingdom Demetrius I "the Invincible" (205–171 BCE), wearing the scalp of an elephant, symbol of his conquests in India.Written evidence of the initial Greek invasion survives in the Greek writings of Strabo and Justin, and in Sanskrit in the records of Patanjali, Kālidāsa, and in the Yuga Purana, among others. Coins and architectural evidence also attest to the extent of the initial Greek campaign.

Evidence of the initial invasion

Greco-Roman sourcesThe Greco-Bactrians went over the Hindu Kush and also started to re-occupy the area of Arachosia, where Greek populations had been living since before the acquisition of the territory by Chandragupta from Seleucus. Isidore of Charax describes Greek cities there, one of them called Demetrias, probably in honour of the conqueror Demetrius.[2]

According to Strabo, Greek advances temporarily went as far as the Shunga capital Pataliputra (today Patna) in eastern India:

"Of the eastern parts of India, then, there have become known to us all those parts which lie this side of the Hypanis, and also any parts beyond the Hypanis of which an account has been added by those who, after Alexander, advanced beyond the Hypanis, to the Ganges and Pataliputra."

— Strabo, 15-1-27[3]

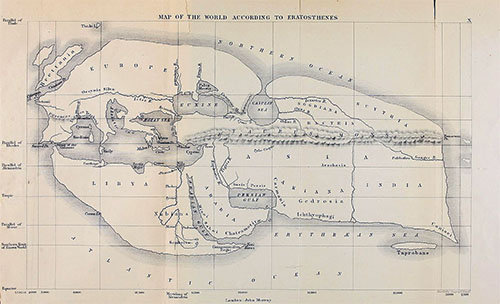

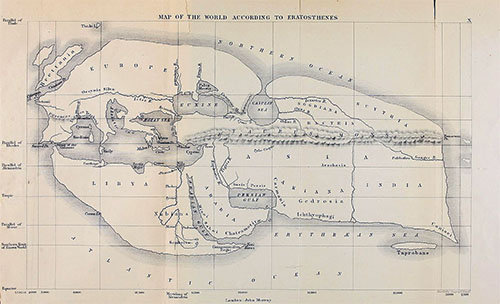

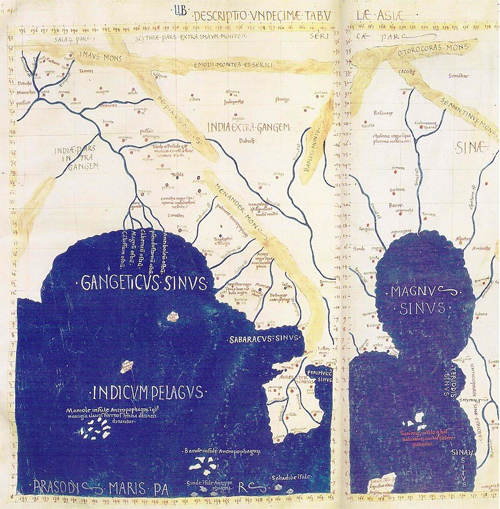

The Hellenistic world view just before the Indo-Greek conquests. India appears fully formed, with the Ganges and Palibothra (Pataliputra) in the east. (19th-century reconstruction of the ancient world map of Eratosthenes (276–194 BCE).[4])

The Hellenistic world view just before the Indo-Greek conquests. India appears fully formed, with the Ganges and Palibothra (Pataliputra) in the east. (19th-century reconstruction of the ancient world map of Eratosthenes (276–194 BCE).[4])The 1st century BCE Greek historian Apollodorus, quoted by Strabo, affirms that the Bactrian Greeks, led by Demetrius I and Menander, conquered India and occupied a larger territory than the Greeks under Alexander the Great, going beyond the Hypanis towards the Himalayas:[5]

"The Greeks became masters of India and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander—by Menander in particular, for some were subdued by him personally and others by Demetrius, the son of Euthydemus the king of the Bactrians."

— Apollodorus, quoted in Strabo 11.11.1[6]

The Roman historian Justin also mentioned the Indo-Greek kingdom, describing a "Demetrius, King of the Indians" ("Regis Indorum"), and explaining that after vanquishing him Eucratides in turn "put India under his rule" ("Indiam in potestatem redegit")[7] (since the time of the embassies of Megasthenes in the 3rd century BCE "India" was understood as the entire subcontinent, and was mapped by geographers such as Eratosthenes). Justin also mentions Apollodotus and Menander as kings of the Indians.[8]

Greek and Indian sources tend to indicate that the Greeks campaigned as far as Pataliputra until they were forced to retreat. This advance probably took place under the reign of Menander, the most important Indo-Greek king (A.K. Narain and Keay 2000) and was likely only of a military advance of temporary nature, perhaps in alliance with native Indian states. The permanent Indo-Greek dominions extended only from the Kabul Valley to the eastern Punjab or slightly further east.

An Indo-Greek stone palette showing Poseidon with attendants. He wears a chiton tunic, a chlamys cape, and boots. 2nd–1st century BCE, Gandhara, Ancient Orient Museum.

An Indo-Greek stone palette showing Poseidon with attendants. He wears a chiton tunic, a chlamys cape, and boots. 2nd–1st century BCE, Gandhara, Ancient Orient Museum.To the south, the Greeks occupied the areas of the Sindh and Gujarat down to the region of Surat (Greek: Saraostus) near Mumbai (Bombay), including the strategic harbour of Barigaza (Bharuch),[9] as attested by several writers (Strabo 11; Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Chap. 41/47) and as evidenced by coins dating from the Indo-Greek ruler Apollodotus I:

"The Greeks... took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis."

— Strabo 11.11.1[10]

The 1st century CE Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes numerous Greek buildings and fortifications in Barigaza, although mistakenly attributing them to Alexander, and testifies to the circulation of Indo-Greek coinage in the region:

"The metropolis of this country is Minnagara, from which much cotton cloth is brought down to Barygaza. In these places there remain even to the present time signs of the expedition of Alexander, such as ancient shrines, walls of forts and great wells."

— Periplus, Chap. 41

"To the present day ancient drachmae are current in Barygaza, coming from this country, bearing inscriptions in Greek letters, and the devices of those who reigned after Alexander, Apollodorus (sic) and Menander."

— Periplus Chap. 47[11]

From ancient authors (Pliny, Arrian, Ptolemy and Strabo), a list of provinces, satrapies, or simple regional designations, and Greek cities from within the Indo-Greek Kingdom can be discerned (though others have been lost), ranging from the Indus basin to the upper valley of the Ganges.[12]

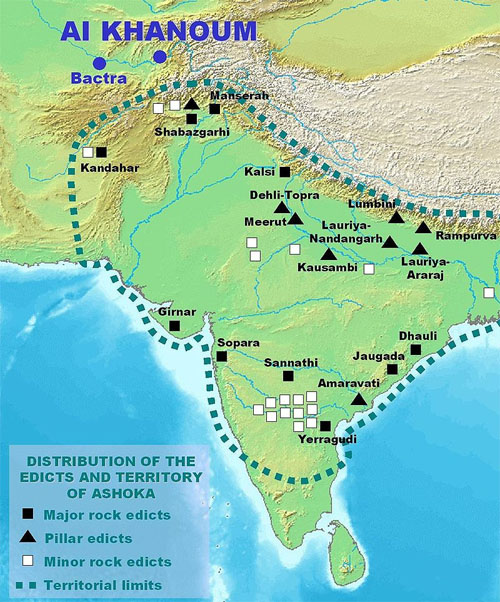

Indian sourcesVarious Indian records describe Yavana attacks on Mathura, Panchala, Saketa, and Pataliputra. The term Yavana is thought to be a transliteration of "Ionians" and is known to have designated Hellenistic Greeks (starting with the Edicts of Ashoka, where Ashoka writes about "the Yavana king Antiochus"), but may have sometimes referred to other foreigners as well, especially in later centuries.

Patanjali, a grammarian and commentator on Pāṇini around 150 BCE, describes in the Mahābhāsya,[13] the invasion in two examples using the imperfect tense of Sanskrit, denoting a recent event:

• "Arunad Yavanah Sāketam" ("The Yavanas (Greeks) besieged Saketa")

• "Arunad Yavano Madhyamikām" ("The Yavanas were besieged Madhyamika" (the "Middle country")).

The Anushasanaparava of the Mahabharata affirms that the country of Mathura, the heartland of India, was under the joint control of the Yavanas and the Kambojas.[14] The Vayupurana asserts that Mathura was ruled by seven Greek kings over a period of 82 years.[15]

Accounts of battles between the Greeks and the Shunga in Central India are also found in the Mālavikāgnimitram, a play by Kālidāsa which describes an encounter between Greek forces and Vasumitra, the grandson of Pushyamitra, during the latter's reign.[16]

Also the Brahmanical text of the Yuga Purana, which describes Indian historical events in the form of a prophecy,[17] relates the attack of the Indo-Greeks on the capital Pataliputra, a magnificent fortified city with 570 towers and 64 gates according to Megasthenes,[18] and describes the ultimate destruction of the city's walls:

"Then, after having approached Saketa together with the Panchalas and the Mathuras, the Yavanas, valiant in battle, will reach Kusumadhvaja ("The town of the flower-standard", Pataliputra). Then, once Puspapura (another name of Pataliputra) has been reached and its celebrated mud[-walls] cast down, all the realm will be in disorder."

— Yuga Purana, Paragraph 47–48, 2002 edition.

According to the Yuga Purana a situation of complete social disorder follows, in which the Yavanas rule and mingle with the people, and the position of the Brahmins and the Sudras is inverted:

"Sudras will also be utterers of bho (a form of address used towards an equal or inferior), and Brahmins will be utterers of arya (a form of address used towards a superior), and the elders, most fearful of dharma, will fearlessly exploit the people. And in the city the Yavanas, the princes, will make this people acquainted with them: but the Yavanas, infatuated by war, will not remain in Madhyadesa."

— Yuga Purana, Paragraph 55–56, 2002 edition.

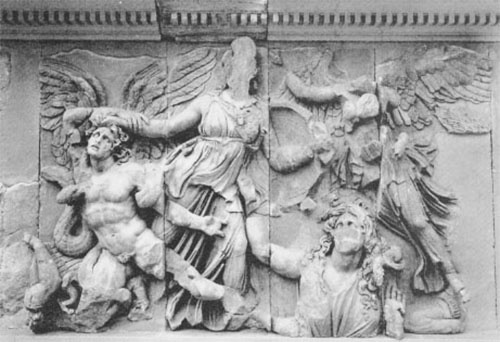

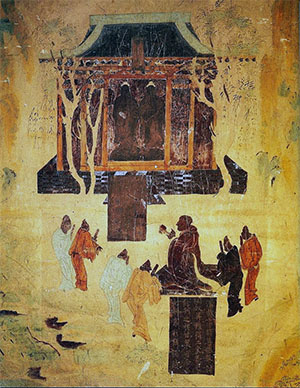

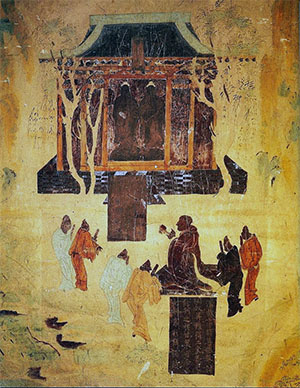

Epigraphic remainsSeveral depictions of Greeks in Central India dated to the 2nd-1st century BCE are known, such as the Greek soldier in Bharhut, or a frieze in Sanchi which describes Greek-looking foreigners honouring the Sanchi stupa with gifts, prayers and music (image above). They wear the chlamys cape over short chiton tunics without trousers, and have high-laced sandals. They are beardless with short curly hair and headbands, and two men wear the conical pilos hat. They play various instruments, including two carnyxes, and one aulos double-flute.[19] This is near Vidisa, where an Indo-Greek monument, the Heliodorus pillar, is known.

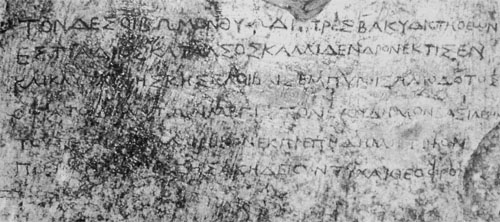

A pillar discovered in Reh, in the Ganges valley 350 km south-east of Mathura mentions Menander:

"The great king of kings, the great king Menander, saviour, steadfast in the Law (dharma), victorious and unvanquished..."

— Reh inscription.[20]

Another inscription 17mk from Mathura, the Maghera inscription, contains the phrase "In the 116th year of the Greek kings...", suggesting Greek rule in the area until around 70 BCE, as the "Greek era" is thought to have started around 186 BCE.[21]

Archaeological remains

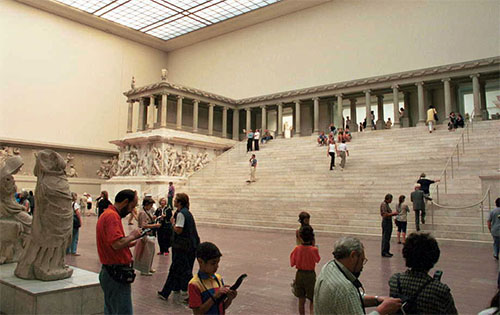

Urban remainsThe city of Sirkap, today in northwestern Pakistan near Taxila, was built according to the "Hippodamian" grid-plan characteristic of Greek cities, and was a Hellenistic fortress of considerable proportions, with a 6,000 meter wall on the circumference, of a height of about 10 meters. The houses of the Indo-Greek level are "the best planned of all the six strata, and the rubble masonry of which its walls are built is also the most solid and compact".[22] It is thought that the city was built by Demetrius.

Artifacts Main archaeological artifacts from the Indo-Greek strata at ancient Taxila. Source: John Marshall "Taxila, Archaeological excavations".

Main archaeological artifacts from the Indo-Greek strata at ancient Taxila. Source: John Marshall "Taxila, Archaeological excavations".Several Hellenistic artifacts have been found, in particular coins of Indo-Greek kings, stone palettes representing Greek mythological scenes, and small statuettes. Some of them are purely Hellenistic, others indicate an evolution of the Greco-Bactrian styles found at Ai-Khanoum towards more indianized styles. For example, accessories such as Indian ankle bracelets can be found on some representations of Greek mythological figures such as Artemis.

The excavations of the Greek levels at Sirkap were however very limited and made in peripheral areas, out of respect for the more recent archeological strata (those of the Indo-Scythian and especially Indo-Parthian levels) and the remaining religious buildings, and due to the difficulty of excavating extensively to a depth of about 6 meters. The results, although interesting, are partial and cannot be considered as exhaustive.[23] Beyond this, no extensive archaeological excavation of an Indo-Greek city has ever essentially been done.

Quantities of Hellenistic artifacts and ceramics can also be found throughout Northern India.[24] Clay seals depicting Greek deities, and the depiction of an Indo-Greek king thought to be Demetrius were found at Benares.[25]

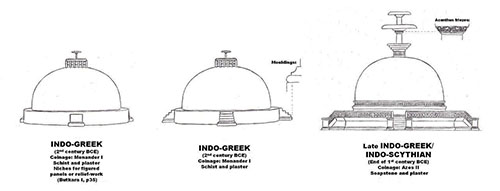

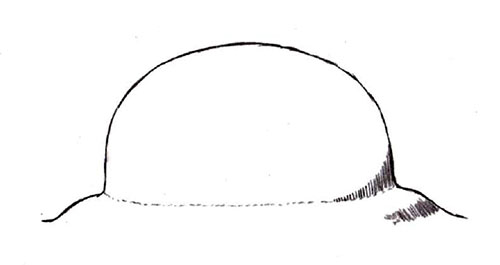

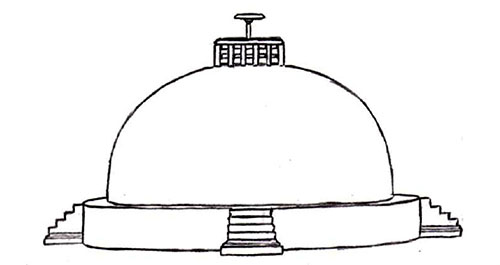

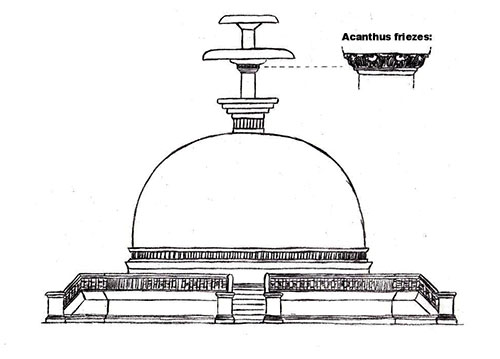

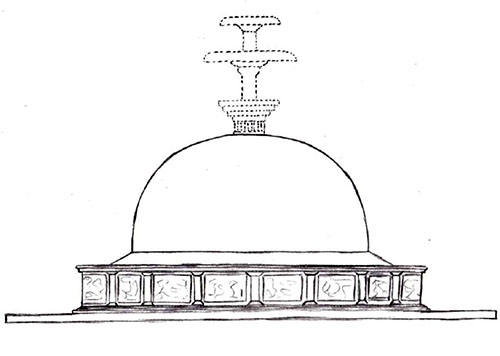

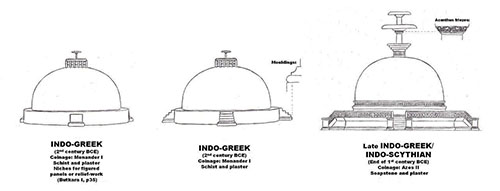

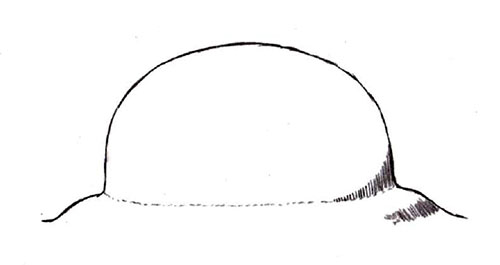

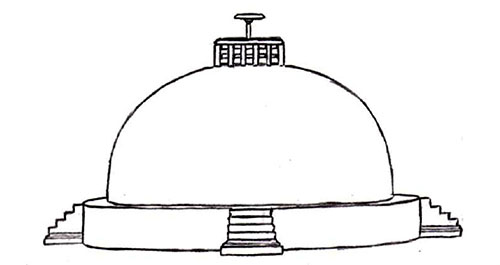

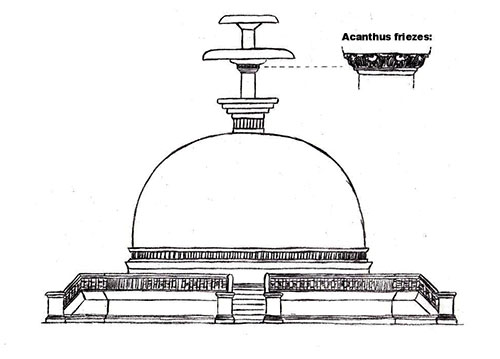

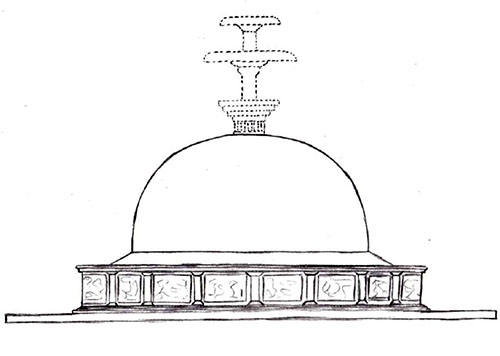

Stupas Evolution of the Butkara stupa (Swat) during the Indo-Greek period.[26]

Evolution of the Butkara stupa (Swat) during the Indo-Greek period.[26] Stupa decorated with acanthus leaves, Level III, Sirkap, 1st century BCE. Diameter: 2.5 meters.[27]

Stupa decorated with acanthus leaves, Level III, Sirkap, 1st century BCE. Diameter: 2.5 meters.[27]When the Indo-Greeks settled in the area of Taxila, large Buddhist structures were already present, such as the stupa of Dharmarajika built by Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE. These structures were reinforced in the following centuries, by building rings of smaller stupas and constructions around the original ones. Numerous coins of the Indo-Greek king Zoilos II were found under the foundation of a 1st-century BCE rectangular chapel near the Dharmarajika stupa.[28]

Also, various Buddhist structures, such as the Butkara Stupa in the area of Swat were enlarged and decorated with Hellenistic architectural elements in the 2nd century BCE, especially during the rule of Menander.[29] Stupas were just round mounds when the Indo-Greeks settled in India, possibly with some top decorations, but soon they added various structural and decorative elements, such as reinforcement belts, niches, architectural decorations such as plinthes, toruses and cavettos, plaster painted with decorative scrolls. The niches were probably designed to place statues or friezes, an indication of early Buddhist descriptive art during the time of the Indo-Greeks.[30] Coins of Menander were found within these constructions dating them to around 150 BCE. By the end of Indo-Greek rule and during the Indo-Scythian period (1st century BCE), stupas were highly decorated with colonnaded flights of stairs and Hellenistic scrolls of Acanthus leaves.

Consolidation

The end of the first conquestsBack in Bactria a king named Eucratides managed to topple the Euthydemid dynasty around 170 BCE and some years later made himself ruler of the westernmost Indian territories as well, thus weakening the Indo-Greek kingdom and putting a stop to their expansion.

Coin of Menander. Greek legend, BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROY lit. "Saviour King Menander".

Coin of Menander. Greek legend, BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROY lit. "Saviour King Menander".There may also have been setbacks in the east. The Hathigumpha inscription, written by the king of Kalinga, Kharavela, also describes the presence of the Yavana king whose name has been identified as "Demetrius" with his army in eastern India, apparently as far as the city of Rajagriha about 70 km southeast of Pataliputra and one of the foremost Buddhist sacred cities, but claims that this Demetrius ultimately retreated to Mathura on hearing of Kharavela's military successes further south:

"Then in the eighth year, (Kharavela) with a large army having sacked Goradhagiri causes pressure on Rajagaha (Rajagriha). On account of the loud report of this act of valour, the Yavana (Greek) King Dimi[ta] retreated to Mathura having extricated his demoralized army and transport."

— Hathigumpha inscription, in Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XX.[31]

The interpretation has been challenged, and a presence this far east seems difficult to attest to Demetrius I, who issued no Indian coins whatsoever.

In any case, Eucratides seems to have occupied territory as far as the Indus, between c. 170 BCE and 150 BCE. His advances were ultimately checked by the Indo-Greek king Menander I who asserted himself in the Indian part of the empire, and began the last expansions eastwards.

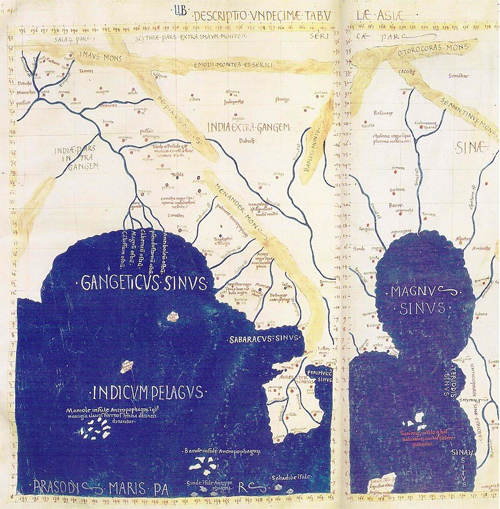

Consolidation and rise of Menander I Detail of Asia in the Ptolemy world map. The "Menander Mons" are in the center of the map, at the east of the Indian subcontinent, beyond the Ganges, right above the Malaysian Peninsula.

Detail of Asia in the Ptolemy world map. The "Menander Mons" are in the center of the map, at the east of the Indian subcontinent, beyond the Ganges, right above the Malaysian Peninsula.Menander is considered as probably the most successful Indo-Greek king, and the conqueror of the vastest territory.[32] The finds of his coins are the most numerous and the most widespread of all the Indo-Greek kings. In Antiquity, from at least the 1st century CE, the "Menander Mons",[citation needed] or "Mountains of Menander", came to designate the mountain chain at the extreme east of the Indian subcontinent, today's Naga hills and Arakan, as indicated in Ptolemy's world map of the 1st century CE geographer Ptolemy. Menander is also remembered in Buddhist literature, where he called Milinda, and is described in the Milinda Panha as a convert to Buddhism: he became an arhat whose relics were enshrined in a manner reminiscent of the Buddha. He also introduced numismatic reforms, such as issuing coins with portraits, which had hitherto been unknown in India. His most common coin reverse Athena Alkidemos ("Protector of the people") became a common type for his successors in the East.

Conquests east of the Punjab region were most likely made during the second half of the century by the king Menander I, but his eastern conquests were brief. The following passage may allude to the return of Menander to his home territories, perhaps due to a civil war with the competing king Zoilos I, or the nomad invasion of Bactria:

"The Yavanas, infatuated by war, will not remain in Madhadesa (the Middle Country). There will be mutual agreement among them to leave, due to a terrible and very dreadful war having broken out in their own realm."

— Yuga Purana, paragraphs 56–57, 2002 edition.

Following Menander's reign, about twenty Indo-Greek kings are known to have ruled in succession in the eastern parts of the Indo-Greek territory. Upon his death, Menander was succeeded by his infant son Thraso, but he was apparently murdered and further civil wars ensued. Judging from their coins, many of the later kings claimed descendance from either the Euthydemids or Menander, but the details remain uncertain due to the lack of sources.

The fall of BactriaFrom 130 BCE, the Scythians and then the Yuezhi, following a long migration from the border of China, started to invade Bactria from the north. Around 125 BCE, the Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles, was probably killed during the invasion and the Greco-Bactrian kingdom proper ceased to exist. The Indo-Greek kingdom, now entirely isolated from the Hellenistic world,[33] did nevertheless maintain itself, if we can judge from the vast number of coins issued from the following kings, such as Lysias and Antialcidas.

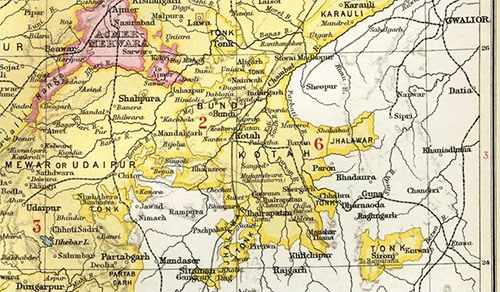

During this time, the Indo-Greek territory seems to have extended from the Paropamisadae and Arachosia in the west, to eastern Punjab, perhaps even with further eastern strongholds such as Mathura (see below). It is uncertain when the coastal provinces along the mouth of the Indus and further east were lost, or how tightly they were ever integrated with the kingdom.

Later historyThroughout the 1st century BCE, the Indo-Greeks progressively lost ground to the Indians in the east, and the Scythians, the Yuezhi, and the Parthians in the West. About 20 Indo-Greek king are known during this period, down to the last known Indo-Greek king Strato II, who ruled in the Punjab region until around 10 CE.

Loss of Mathura and eastern territories (after 100 BCE) Coin of the Yaudheyas.

Coin of the Yaudheyas. Coin of Philoxenus, unarmed, making a blessing gesture with the right hand.

Coin of Philoxenus, unarmed, making a blessing gesture with the right hand.The Indo-Greeks may have ruled as far as the area of Mathura until sometime in the 1st century BCE: the Maghera inscription, from a village near Mathura, records the dedication of a well "in the one hundred and sixteenth year of the reign of the Yavanas", which could be as late as 70 BCE.[34] Soon however Indian kings recovered the area of Mathura and south-eastern Punjab, west of the Yamuna River, and started to mint their own coins. The Arjunayanas (area of Mathura) and Yaudheyas mention military victories on their coins ("Victory of the Arjunayanas", "Victory of the Yaudheyas"). During the 1st century BCE, the Trigartas, Audumbaras and finally the Kunindas (closest to Punjab) also started to mint their own coins, usually in a style highly reminiscent of Indo-Greek coinage.

The Western king Philoxenus briefly occupied most of the remaining Greek territory from the Paropamisadae to Western Punjab c. 100 BCE, after which the territories fragmented again. The following decades saw fierce internal fighting between several kings, such as Heliokles II, Strato I and Hermaeus, which contributed to the downfall in a manner perhaps reminiscent of how the Seleucid and Ptolemaic states were torn apart by dynastic wars at the same period.

The Yuezhi expansion (70 BCE–)Main article: Yuezhi

Philoxenus was succeeded by Diomedes, probably his son or younger brother, in the west, but his reign was short and he was succeeded by Hermaeus, a king married to the princess Calliope who was likely a daughter of Philoxenus.[35] After a reign of at least one decade, Hermaeus was overthrown by nomad tribes, either the Yuezhi or Sakas [36] When Hermaeus is depicted on his coins riding a horse, he is equipped with the recurve bow and bow-case of the steppes.

In any case, these nomads became the new rulers of the Paropamisadae, and minted vast quantities of posthumous issues of Hermaeus up to around 40 CE, when they blend with the coinage of the Kushan king Kujula Kadphises. The first documented Yuezhi prince, Sapalbizes, ruled around 20 BCE, and minted in Greek and in the same style as the western Indo-Greek kings, probably depending on Greek mints and celators.

Scythian invasions (80 BCE – 50 CE) Tetradrachm of Hippostratos, reigned c. 65–55 BCE.

Tetradrachm of Hippostratos, reigned c. 65–55 BCE. Silver coin of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II (r. c. 35–12 BCE).

Silver coin of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II (r. c. 35–12 BCE).Main article: Indo-Scythians

Around 80 BCE, an Indo-Scythian king named Maues, possibly an ally of some of the Indo-Greeks kings, captured Taxila and ruled Gandhara for a few years. The king he dethroned was probably Archebius. After Maues' death, the Indo-Greeks were able to regain control of Taxila, but at this time the line between Greeks and Sakas may not have been that clear. Among the kings who emerged in Gandhara after Maues' death, Artemidoros who was seemingly a regular Indo-Greek king, presents himself as "son of Maues" on a bronze. This discovery caused a small sensation and has led scholars such as Senior [37] to assume that also Hermaeus may have been of partly Saka origin.

Another important king during this period was Amyntas, who issued the last Attic coins found in Bactria and may have attempted to reunite the Indo-Greek territories. It was however the king Apollodotus II, seemingly a descendant of Menander, who managed to regain Gandhara from remaining Greek strongholds in eastern Punjab. After the death of Apollodotus II the kingdom fragmented once more.

In the west, he was succeeded by Hippostratos who was initially a successful ruler, but he was the last western ruler: around 55–50 BCE he was defeated by the Indo-Scythian Azes I, who established his own Indo-Scythian dynasty.

Although the Indo-Scythians clearly ruled militarily and politically, they remained respectful of Greek and Indian cultures. Their coins were minted in Greek mints, continued using proper Greek and Kharoshthi legends, and incorporated depictions of Greek deities, particularly Zeus. The Mathura lion capital inscription attests that they adopted the Buddhist faith, as do the depictions of deities forming the vitarka mudra on their coins. Greek communities, far from being exterminated, probably persisted under Indo-Scythian rule. The Buner reliefs show Indo-Greeks and Indo-Scythians reveling in a Buddhist context.

The last eastern kingdom (50 BCE – 10 CE)The Indo-Greeks continued to maintain themselves in the eastern Punjab for several decades, until the kingdom of the last Indo-Greek king Strato II was taken over by the Indo-Scythian ruler Rajuvula around 10 CE. The coins of these Indo-Greek rulers deteriorated constantly, both in terms of artistic quality (due to the long isolation) and in silver content. Still, the last Strato had the honour of ruling the last pocket of an independent Hellenistic state; when he disappeared, Cleopatra, usually seen as the last of the rulers who followed Alexander the Great, was already gone.

Indo-Parthian rule (10–60 CE) Indo-Parthian king and attendants. Ancient Orient Museum.

Indo-Parthian king and attendants. Ancient Orient Museum.Main article: Indo-Parthian Kingdom

The Parthians, represented by the Suren, a noble Parthian family of Arsacid descent, started to make inroads into the territories which had been occupied by the Indo-Scythians and the Yuezhi, until the demise of the last Indo-Scythian emperor Azes II around 12 BCE. The Parthians ended up controlling all of Bactria and extensive territories in Northern India, after fighting many local rulers such as the Kushan Empire ruler Kujula Kadphises, in the Gandhara region. Around 20, Gondophares, one of the Parthian conquerors, declared his independence from the Parthian empire and established the Indo-Parthian kingdom in the conquered territories, with his capital in ancient Taxila.

Kushan supremacy A Yuezhi/ Kushan man in traditional costume with tunic and boots, 2nd century CE, Gandhara.

A Yuezhi/ Kushan man in traditional costume with tunic and boots, 2nd century CE, Gandhara.Main article: Kushan Empire

The Yuezhi expanded to the east during the 1st century CE, to found the Kushan Empire. The first Kushan emperor Kujula Kadphises ostensibly associated himself with Hermaeus on his coins, suggesting that he may have been one of his descendants by alliance, or at least wanted to claim his legacy. The Yuezhi (future Kushans) were in many ways the cultural and political heirs to the Indo-Greeks, as suggested by their adoption of the Greek culture (writing system, Greco-Buddhist art) and their claim to a lineage with the last western Indo-Greek king Hermaeus.

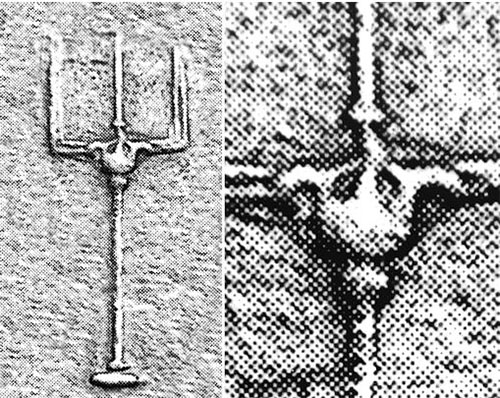

The last known mention of an Indo-Greek ruler is suggested by an inscription on a signet ring of the 1st century CE in the name of a king Theodamas, from the Bajaur area of Gandhara, in modern Pakistan. No coins of him are known, but the signet bears in kharoshthi script the inscription "Su Theodamasa", "Su" being explained as the Greek transliteration of the ubiquitous Kushan royal title "Shau" ("Shah", "King").

The Indo-Greek rulers"Indo-Greek" kings are distinguished from "Bactrian" kings in that they issued dominantly bilingual coinage, meant for circulation outside the Hindu Kush. However, Demetrius I is usually included (though he issued no such coins) and some mainly Bactrian kings who also held Indian territories. The chronology is tentative, as are the territories. This overview largely gives the chronology of Senior (2004) while most of the territories are adapted from Bopearachchi (1991). The views of both authors, as well as other alternatives, are given under each king.

The Bactrian period (c. 200–130 BCE)

Territories of Arachosia, Paropamisadae, Gandhara?Euthydemus I and Demetrius I (c. 200–175 BCE) Coins. Demetrius was the first Indo-Greek king to gain territories in India. It is possible that he made his first conquests as general for his father, a view supported by the Heliodorus inscription.

Demetrius I, founder of the Indo-Greek kingdom (r. c. 205–171 BCE).Territories of Paropamisadae, Gandhara

Demetrius I, founder of the Indo-Greek kingdom (r. c. 205–171 BCE).Territories of Paropamisadae, Gandhara• Pantaleon

• Agathocles Coins. These two Bactrian kings, likely father and son, ruled between c. 190–175 BCE.

Territories of Gandhara, western Punjab• Apollodotus I (c. 180–160 BCE)

• Antimachus II (c. 174–165 BCE or 160–155 BCE). Coins R.C Senior (2004) has suggested that this king was possibly identical with Antimachus I, but an Antimachus, who was the co-regent (and presumably son) of Antimachus I is known from a preserved tax-receipt.

Territories of Gandhara, western and eastern Punjab• Menander I (reigned c. 165/155 – 135/130 BCE), though with some interruption in the western territories. Legendary for the size of his kingdom, and his support of the Buddhist faith. Coins

Territories of Arachosia, Paropamisadae, Gandhara• Eucratides managed to eradicate the Euthydemid dynasty and occupy territory as far as he Indus, between c. 160–145 BCE. Eucratides was then murdered by his son, thereafter Menander I seems to have regained all of the territory as far west as the Hindu-Kush.

• Zoilos I This king may have fought against Menander I around 150–140 BCE.

• (Demetrius III possibly c. 150 BCE). This ephemeral ruler was possibly identical with the Demetrius, king of the Indians, who fought with Eucratides.[38]

Civil wars and nomad invasions (c. 130 BCE – 50 CE)

Territories of Gandhara or western PunjabA smaller kingdom seems to have emerged in the Kabul valley, between c. 130–115/110 BCE.

• Thrason Son of Menander, ruled very briefly c. 130 BCE.

• Nicias

• Theophilos Coin

• Philoxenus

Territories of Arachosia, Paropamisadae, Gandhara, western and eastern Punjab• Lysias Coins and

• Antialcidas Coins were the most important successors of Menander. They ruled most of the Indo-Greek kingdom, though perhaps as co-rulers, c. 130–110 BCE.

• Philoxenus (c. 115–105 or 100–95 BCE) Coins. Philoxenus temporarily united the major kingdom with the smaller state in the Kabul valley.

Territories of Arachosia and the Paropamisadae• Diomedes (c. 105–95 BCE) Coin

• Hermaeus (reigned c. 95–80 BCE).

• ( Yuezhi or Saka rulers)

Territories of Gandhara, western and eastern Punjab A number of kings fought for hegemony during the period after Philoxenus' death to the advent of Maues.

• Agathokleia (c. 110–105 BCE), Probably widow of another king, she was presumably regent for her son Strato I. Coins

• Strato I (c. 110–85 BCE) Coin

The territory of Mathura and eastern Punjab may have been lost after Strato's death.

• Heliokles II (c. 95–80 BCE) Coins

• Archebios (c. 90–80 BCE) Coins

• Amyntas Nikator (c. 80–65 BCE) Coins

The following minor kings ruled parts of the kingdom:

• Polyxenos (c. 80 BCE - possibly in Gandhara)

• Peukolaos (c. 90 BCE)

• Demetrius III Aniketos (possibly c. 75 BCE)

• Epander (c. 95–90 BCE) Coins

Territories of the Paropamisadae and Gandhara During the 1st century BCE, the Indo-Greeks progressively lost ground against the invasion of the Indo-Scythians. After the invasion of (Maues), the following kings maintained themselves in the Paropamisadae or Gandhara:

• Menander II (c. 70–65 BCE) Coins

• Artemidoros (c. 75–65 BCE) Coins.

• Telephos (c. 65–60 BCE) Coins

Despite his Greek name, Artemidoros was the son of Maues and therefore formally a Scythian king, and the ethnicity of Telephus is unknown as well.

Tetradrachm of Hippostratus.Territories of Gandhara, western and eastern Punjab

Tetradrachm of Hippostratus.Territories of Gandhara, western and eastern Punjab• Apollodotus II (c. 65–55 BCE) Coins

Apollodotus II temporarily united most of the Indo-Greek kingdom, but after his death it fragmented again.

Territories of Gandhara and western Punjab• Hippostratos (c. 60–50 BCE)Coins, who was defeated by the Indo-Scythian King Azes I.

• (Azes I). Indo-Scythian king.

Last eastern kingdom

Territories of eastern PunjabThe last Indo-Greek kings ruled in eastern Punjab from around 55 BCE – 10 CE

• Dionysios

• Zoilos II

• Apollophanes

• Strato IICoin with Strato III, who was overthrown by

• (Rajuvula), Indo-Scythian king.

Indo-Greek princelets (Gandhara)After the Indo-Scythian Kings became the rulers of northern India, remaining Greek communities were probably governed by lesser Greek rulers, without the right of coinage, into the 1st century CE, in the areas of the Paropamisadae and Gandhara:

• Theodamas (c. 1st century CE) Indo-Greek ruler of the Bajaur area, northern Gandhara.

The Indo-Greeks may have kept a significant military role towards the 2nd century CE as suggested by the inscriptions of the Satavahana kings.

References1. The title "Anicetus" for Demetrius is visible on the pedigree coins minted by Agathocles.

2. In the 1st century BCE, the geographer Isidorus of Charax mentions Parthians ruling over Greek populations and cities in Arachosia: "Beyond is Arachosia. And the Parthians call this White India; there are the city of Biyt and the city of Pharsana and the city of Chorochoad and the city of Demetrias; then Alexandropolis, the metropolis of Arachosia; it is Greek, and by it flows the river Arachotus. As far as this place the land is under the rule of the Parthians." "Parthians stations", 1st century BCE. Mentioned in Bopearachchi, "Monnaies Greco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques", p52. Original text in paragraph 19 of Parthian stations.

3. The word for "advance" is "προελθοντες", meaning a military expedition. Strabo 15-1-27

4. Source

5. Strabo quoting Apollodorus on the extent of Greek conquests:

"Apollodorus, for instance, author of the Parthian History, when he mentions the Greeks who occasioned the revolt of Bactriana from the Syrian kings, who were the successors of Seleucus Nicator, says, that when they became powerful they invaded India. He adds no discoveries to what was previously known, and even asserts, in contradiction to others, that the Bactrians had subjected to their dominion a larger portion of India than the Macedonians; for Eucratides (one of these kings) had a thousand cities subject to his authority." Strabo 15-1-3 Full text

"The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Ariana, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander—by Menander in particular (at least if he actually crossed the Hypanis towards the east and advanced as far as the Imaüs), for some were subdued by him personally and others by Demetrius, the son of Euthydemus the king of the Bactrians." (Strabo 11.11.1 Full text)

6. Strabo 11.11.1

7. Justin on Demetrius "King of the Indians": "Multa tamen Eucratides bella magna uirtute gessit, quibus adtritus cum obsidionem Demetrii, regis Indorum, pateretur, cum CCC militibus LX milia hostium adsiduis eruptionibus uicit. Quinto itaque mense liberatus Indiam in potestatem redegit." ("Eucratides led many wars with great courage, and, while weakened by them, was put under siege by Demetrius, king of the Indians. He made numerous sorties, and managed to vanquish 60,000 enemies with 300 soldiers, and thus liberated after four months, he put India under his rule") Justin XLI,6

8. "Indicae quoque res additae, gestae per Apollodotum et Menandrum, reges eorum": "Also included are the exploits in India by Apollodotus and Menander, their kings" Justin, quoted in E.Seldeslachts, p284

9. "Menander became the ruler of a kingdom extending along the coast of western India, including the whole of Saurashtra and the harbour Barukaccha. His territory also included Mathura, the Punjab, Gandhara and the Kabul Valley", Bussagli p101)

10. Strabo on the extent of the conquests of the Greco-Bactrians/Indo-Greeks: "They took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis. In short, Apollodorus says that Bactriana is the ornament of Ariana as a whole; and, more than that, they extended their empire even as far as the Seres and the Phryni." Strabo 11.11.1 (Strabo 11.11.1)

11. Periplus

12. Greek provinces in India according to Classical sources:

Patalene - the whole Indus delta region, with an apparent capital in "Demetrias-in-Patalene;" presumably founded by Demetrius (Ptolemy, Geographia, VII 1, 55/ Strabo 11.11.1)

Abiria - North of the Indus delta and apparently named for the Ahbira peoples, presumably in residence of the region. (Ptolemy, Geographia, VII 1, 55).

Prasiane - North of Abiria and East of the main Indus channel. (Pliny, Natural history, VI 71)

Surastrene - Southeast of Patalene, comprising the Kathiawar peninsula and parts of Gujarat to Bharuch (modern Saurashtra and Surat), with the city of "Theophila". (Ptolemy, Geographia, VII 1, 55/ Strabo 11.11.1/ Periplus, Chap.41–47).

Sigerdis - a coastal region beyond Patalene and Surastrene, thought to correspond to Sindh. (Strabo 11.11.1)

Souastene - subdivision of Gandhara, comprising the Swat Valley (Ptolemy, Geographia, VII 1, 42).

Goryaea - smaller district located between the lower Swat river and the Kunar (Bajaur), with the city of "Nagara, also called Dionysopolis". (Ptolemy, Geographia, VII 1, 42).

Peucelaitas - denotes the immediate district around Pushkalavati (Greek: Peucela). (Arrian, On India, IV 11)

Kaspeiria - comprising the upper valleys of the Chenab, Ravi, and Jhelum (i.e., southern Kashmir). (Ptolemy, Geographia, VII 1, 42).

Pandouorum - Region of the Punjab along the Hydaspes river, with the "city of Sagala, also called Euthydemia" and another city named "Bucephala" (Ptolemy, Geographia, VII 1), or "Bucephalus Alexandria" (Periplus, 47).

Kulindrene - as related by Ptolemy, a region comprising the upper valleys of the Sutlej, Jumna, Beas, and Ganges. This report may be inaccurate, and the contents of the region somewhat smaller. (Ptolemy, Geographia, VII 1, 42).

13. "Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian institution", Bopearachchi, p16.

14. "tatha Yavana Kamboja Mathuram.abhitash cha ye./ ete ashava.yuddha.kushaladasinatyasi charminah."//5—(MBH 12/105/5, Kumbhakonam Ed)

15. "Asui dve ca varsani bhoktaro Yavana mahim/ Mathuram ca purim ramyam Yauna bhoksyanti sapta vai" Vayupurana 99.362 and 383, quoted by Morton Smith 1973: 370. Morton Smith thinks occupation lasted from 175 to 93 BCE.

16. "Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian institution", Bopearachchi, p16. Also: "Kalidasa recounts in his Mālavikāgnimitra (5.15.14–24) that Puspamitra appointed his grandson Vasumitra to guard his sacrificial horse, which wandered on the right bank of the Sindhu river and was seized by Yavana cavalrymen- the later being thereafter defeated by Vasumitra. The "Sindhu" referred to in this context may refer the river Indus: but such an extension of Shunga power seems unlikely, and it is more probable that it denotes one of two rivers in central India -either the Sindhu river which is a tributary of the Yamuna, or the Kali-Sindhu river which is a tributary of the Chambal." The Yuga Purana, Mitchener, 2002.

17. "For any scholar engaged in the study of the presence of the Indo-Greeks or Indo-Scythians before the Christian Era, the Yuga Purana is an important source material" Dilip Coomer Ghose, General Secretary, The Asiatic Society, Kolkata, 2002

18. "The greatest city in India is that which is called Palimbothra, in the dominions of the Prasians [...] Megasthenes informs us that this city stretched in the inhabited quarters to an extreme length on each side of eighty stadia, and that its breadth was fifteen stadia, and that a ditch encompassed it all round, which was six hundred feet in breadth and thirty cubits in depth, and that the wall was crowned with 570 towers and had four-and-sixty gates." Arr. Ind. 10. "Of Pataliputra and the Manners of the Indians.", quoting Megasthenes Text Archived 2008-12-10 at the Wayback Machine

19. Source: "A guide to Sanchi" John Marshall. These "Greek-looking foreigners" are also described in Susan Huntington, "The art of ancient India", p100.

20. "Original prakrit: "Maharajasa Rajarajasa/ Mahamtasa Tratarasa Dhammi/kasa Jayamtasa ca Apra/[jitasa] Minada[de?]rasa....", in R. C. Senior, 2004, p.xiv

21. R. C. Senior, 2006, p.xv

22. Marshall, "Sirkap Archeological Report", p 15–16

23. The excavations by John Marshall at Taxila are the only significant excavations ever done, but only a small and peripherical portion of the city of Sirkap has been excavated to the Greek level ("The chief area in which digging has been carried down to the Greek strata is a little to the West of the main street near the northern gateway (...) Had it been practicable, I should have preferred to choose an area nearer to the city's center, where more interesting structures may be expected than in the outlying quarters near the city wall" ("Taxila", p120). Overall, the Greek excavations only represented a small part of the excavations: "And let me say that seven-eighths of the digging in this area has been devoted to Saka-Parthian structures of the second stratum; one-eight only to the earlier Saka and Greek remains below" ("Taxila", p119)

24. Narain "The Indo-Greeks"

25. "An ancient reference to Menander's invasion" The Indian Historical Quarterly XXIX/1 Agrawala 1953, p180–182.

26. Reference: Domenico Faccenna, "Butkara I, Swat Pakistan, 1956–1962), Part I, IsMEO, ROME 1980.

27. Marshall, "Taxila", p.120

28. Chapel H, about 50 meters near the Dharmarajika stupa, in Marshall, "Excavations at Taxila", "The only minor antiquities of interest found in this building were twenty-five debased silver coins of the Greek king Zoilus II, which were brought to light beneath the foundations of the earliest chapel", p248

29. "From Butkara I we know that building activities never ceased. The stupa was enlarged in a second phase under Menander, and again when the coins of Azes II were in circulation." Harry Falk "Afghanistan, ancien carrefour entre l'Est et l'Ouest", p.347. "The diffusion, from the second century BCE, of Hellenistic influences in the architecture of Swat is also attested by the archaeological searches at the sanctuary of Butkara I, which saw its stupa "monumentalized" at that exact time by basal elements and decorative alcoves derived from Hellenistic architecture", in "De l'Indus a l'Oxus: archaeologie de l'Asie Centrale" 2003, Pierfrancesco Callieri, p212

30. "They were intended to hold a figured panel, relief-work, or something of the kind" Domenico Facenna, "Butkara I"

31. Full text of the Hathigumpta inscription Archived 2006-11-17 at the Wayback Machine

32. "Numismats and historians are unanimous in considering that Menander was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, and the most famous of the Indo-Greek kings. The coins to the name of Menander are incomparably more abundant than those of any other Indo-Greek king" Bopearachchi, "Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques", p76.

33. Jakobsson, Jens (2009). "Who Founded the Indo-Greek Era of 186/5 B.C.E.?". The Classical Quarterly. 59 (2): 505–510. doi:10.1017/S0009838809990140. ISSN 0009-8388. JSTOR 20616702.

34. The Sanskrit inscription reads "Yavanarajyasya sodasuttare varsasate 100 10 6". R.Salomon, "The Indo-Greek era of 186/5 B.C. in a Buddhist reliquary inscription", in "Afghanistan, ancien carrefour entre l'est et l'ouest", p373

35. Senior, 2004

36. Bopearachchi's and Senior's views, respectively. See for instance Bopearachchi, 1998, and Senior, 1998,

37. R. C. Senior, 2004 [1] and 1998. See also this source Archived 2007-10-15 at the Wayback Machine.

38. Jakobsson, J. Relations between the Indo-Greek kings after Menander I, part 1, Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society 191, 2007

Sources• Bopearachchi, Osmund (1991). Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (in French). Bibliothèque Nationale de France. ISBN 2-7177-1825-7.

• Bopearachchi, Osmund (1998). SNG 9. New York: American Numismatic Society. ISBN 0-89722-273-3.

• Senior, R. C, New Indo Greek Coins, Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society 186

• Senior, R. C. and MacDonald, D, The decline of the Indo-Greeks, Monographs of the Hellenic Numismatic Society, Athens, 1998

• Senior, R. C., Indo-Greek–The Indo-Greek and Indo-Scythian King Sequences in the Second and First Centuries BC, 2004, Supplement to Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter, no. 179

Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kings, territories and chronologyThe Indo-Greeks and Buddhism: chronological markers

Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kings, territories and chronologyThe Indo-Greeks and Buddhism: chronological markersMAURYA EMPIRE (315–180 BCE) Periods/MarkersARTIFACTS:

Pillars of Ashoka (c. 250 BCE)

EPIGRAPHY:

Edicts of Ashoka (c. 250 BCE)

BUDDHA STATUES:

None

STUPAS: (Butkara stupa)[2]

Simple stupas

Simple stupas

INDO-GREEK KINGDOM (180 BCE–20 CE) Periods/MarkersARTIFACTS:

Buddhist coins of Menander I (c. 150 BCE)

EPIGRAPHY:

Milinda Panha

Chinese Buddhist accounts of Golden statues from Central Asia in 120 BCE

Chinese Buddhist accounts of Golden statues from Central Asia in 120 BCEBUDDHA STATUES:

Greco-Buddhist statuary (Pre-Kushan)[1]

Greco-Buddhist statuary (Pre-Kushan)[1]STUPAS: (Butkara stupa)[2]

Improved stupas with niches for statues or friezes.

Improved stupas with niches for statues or friezes.

INDO-SCYTHIAN KINGDOM (80 BCE–20 CE) Periods/MarkersARTIFACTS:

Butkara stupa pillar (20 BCE)

Butkara stupa pillar (20 BCE) Bimaran casket (30 BCE–60 CE)

Bimaran casket (30 BCE–60 CE)Sirkap statuary (1–60 CE)

EPIGRAPHY:

Mathura lion capital (20 CE)

Mathura lion capital (20 CE)BUDDHA STATUES:

Greco-Buddhist statuary (Pre-Kushan)[1]

Greco-Buddhist statuary (Pre-Kushan)[1]STUPAS: (Butkara stupa)[2]

Colonated stupas

Colonated stupas

INDO-PARTHIAN KINGDOM (20–60 CE) Periods/MarkersARTIFACTS:

Bimaran casket (30 BCE–60 CE)

Bimaran casket (30 BCE–60 CE)

Sirkap statuary (1–60 CE)EPIGRAPHY:

None

BUDDHA STATUES:

Greco-Buddhist statuary (Pre-Kushan)[1]

Greco-Buddhist statuary (Pre-Kushan)[1]STUPAS: (Butkara stupa)[2]

None

KUSHAN EMPIRE (60–240 CE) Periods/MarkersARTIFACTS:

Mahayana Buddhist triads

Mahayana Buddhist triadsEPIGRAPHY:

Buddhist coinage of Kanishka, derived from free-standing Buddha statues (120 CE)

Buddhist coinage of Kanishka, derived from free-standing Buddha statues (120 CE)BUDDHA STATUES:

Kushan Buddhist friezes

Kushan Buddhist friezesSTUPAS: (Butkara stupa)[2]

Stupas with narrative friezes

Stupas with narrative friezes