Donation of Constantine

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/25/21

-- Noble lie [Pious Fiction] [Pious Fraud] [Pious Invention], by Wikipedia

-- Outline of forgery, by Wikipedia

-- Literary forgery, by Wikipedia

-- False document, by Wikipedia

-- Pseudepigrapha, by Wikipedia

-- Donation of Constantine, by Wikipedia

-- A treasured manuscript in a college library that was believed to have been written by Galileo is a forgery, university says, by Aya Elamroussi

-- The Artist Who Got Rich Forging Picasso & Matisse: Real Fake: Elmyr de Hory, by Perspective

-- Forgery, by Wikipedia

Ashoka

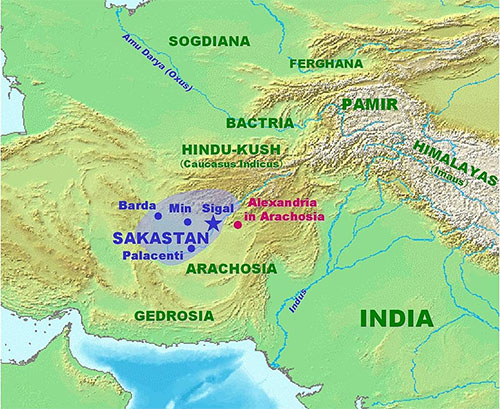

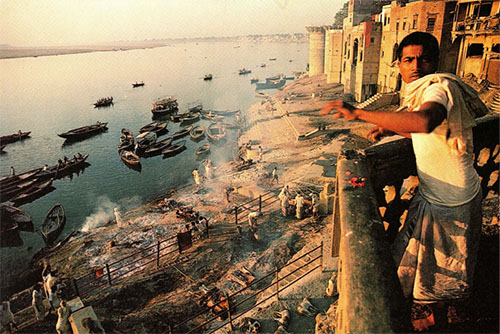

The trappings of government set up in Calcutta to cope with the sudden acquisition of Bengal included not only a judiciary but also a mint. It was as Assistant Assay-Master at this mint that James Prinsep arrived in India in 1819. The post was an undistinguished one; Prinsep, far from being a celebrity like Jones, could expect nothing better. He was barely 20 and, according to his obituarist, "wanting, perhaps, in the finish of classical scholarship which is conferred at the public schools and universities of England''. As a child, the last in a family of seven sons, his passion had been constructing highly intricate working models; "habits of exactness and minute attention to detail'' would remain his outstanding traits. He studied architecture under Pugin, transferred to the Royal Mint when his eyesight became strained, and thence to Calcutta. ''Well grounded in chemistry, mechanics and the useful sciences", he was not an obvious candidate for the mantle of Jones and the distinction of being India's most successful scholar.

In the quarter century between Jones' death and Prinsep's arrival the British position in India had changed radically. The defeats of Tippu Sultan, ruler of Mysore, of the Marathas, and of the Gurkhas had left the British undisputed masters of as much of India as they cared to digest. Indeed the British raj had begun. The sovereignty of the East India Company was almost as much a political fiction as that of their nominal but now helpless overlord, the Moghul emperor. Both, though they lingered on for another 30 years, had become anachronisms.

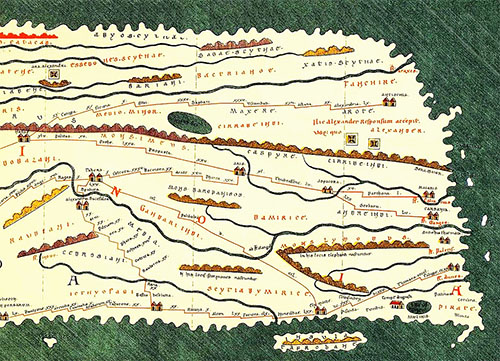

From Calcutta a long arm of British territory now reached up the Ganges and the Jumna to Agra, Delhi and beyond. A thumb prodded the Himalayas between Nepal and Kashmir, while several stubby fingers probed into Punjab, Rajasthan and central India. In the west, Bombay had been expanding into the Maratha homeland; Broach and Baroda were under Britfsh control, and Poona, a centre of Hindu orthodoxy and the Maratha capital, was being transformned into the legendary watering place for Anglo-Indian bores. In the south, all that was not British territory was held by friendly feudatories; the French had been obliterated, Mysore settled, and the limits of territorial expansion already reached.

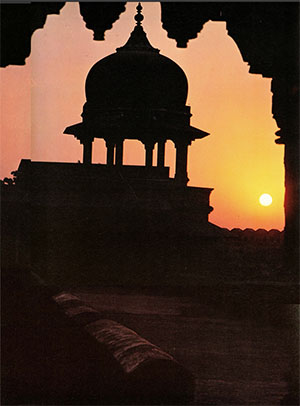

Visitors in search of the real India no longer had to hop around the coastline; they could now march boldly, and safely, across the middle. Bishop Heber of Calcutta (the appointment itself was a sign of the times; in Jones's day there had not been even a church in Calcutta) toured his diocese in the 1820s. The diocese was a big one -- the whole of India -- and ''Reginald Calcutta", as he signed himself, travelled the length of the Ganges to Dehra Dun in the Himalayas, then down through Delhi and Agra into Rajasthan, still largely independent, and came out at Poona and thence down to Bombay.

The acquisition of all this new territory brought the British into contact with the country's architectural heritage. Two centuries earlier Elizabethan envoys had marvelled at the cities of Moghul India ''of which the like is not to be found in all Christendom". The famous buildings of Agra, Fatehpur Sikri and Delhi, ''either of them much greater than London and more populous", they had described in detail. When, therefore, the first generation of British administrators arrived in upper India they showed genuine reverence for the architectural relics of Moghul power. Instead of the landscapes of Hodges and the Daniells their souvenirs of India would be detailed drawings of the Taj Mahal and the Red Fort. Their curiosity also extended to buildings sacred to the non-Mohammedan population; Khajuraho, Abu and many other sites were discovered between 1810 and 1830. The raw materials for a new investigation of India's past were accumulating. But it was another class of monuments, predating the Mohammedan invasions and with unmistakable signs of extreme antiquity, which would become Prinsep's speciality.

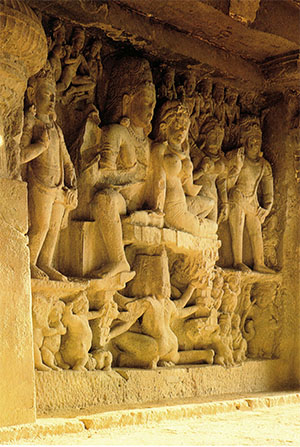

The first of these monuments -- one could scarcely call them buildings -- to attract European attention were the cave temples in the vicinity of Bombay. The island of Elephanta in Bombay harbour had been known to the Portuguese and became the subject of one of the earliest archaeological reports received by Jones's new Asiatic Society.The cave is about three-quarters of a mile from the beach; the path leading to it lies through a valley; the hills on either side beautifully clothed and, except when interrupted by the dove calling to her absent mate, a solemn stillness prevails; the mind is fitted for contemplating the approaching scene.

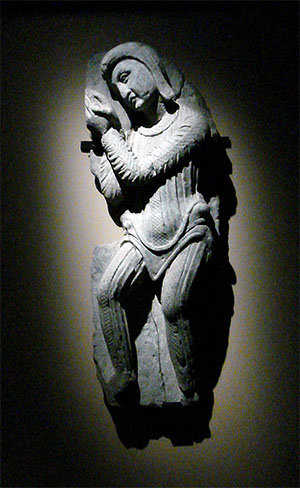

The approaching scene was not of some natural cave with a few prehistoric scratchings, but of a spacious pillared hall, with delicate sculptural details and colossal stone figures -- an architectural creation in all but name; for the whole thing was hacked, hewn, carved and sculpted out of solid rock.

North of Bombay, the island of Salsette boasted more groups of such caves. In 1806 Lord Valentia, a young Englishman whose greatest claim to fame must be the sheer weight of his travelogue (four quarto volumes of just on half a hundredweight), set out to explore them. He took with him Henry Salt, his companion and artist, to help clear a path through the jungle that surrounded the caves. Outside the Jogeshwar caves they hesitated before the fresh pug marks of a tiger; according to the villagers, tigers actually lived in the caves for part of the year.

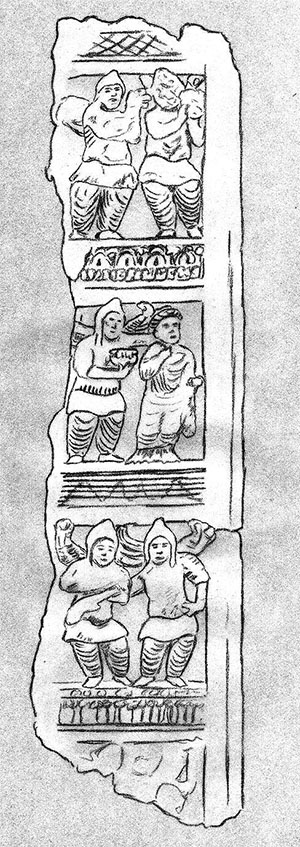

Salt found that the other Salsette caves at Kanheri and Montpezir had also been recently occupied. To the Portuguese, the pillared nave and the trahsepts had spelt basilica; there was even a hole in the facade for a rose window. They had just smothered the fine, but pagan, carving in stucco and consecrated the place. Salt chipped away at the stucco and observed how well it had preserved the sculpture.Though these figures are by no means well proportioned, yet their air, size and general management give an expression of grandeur that the best sculptors have often failed in attaining; the laziness of attitude, the simplicity of drapery, the suitableness of their situation and the plainness of style in which they are executed . . . all contribute towards producing this effect.

He was getting quite a feeling for ancient art treasures. In Lord Valentia's train he would move on to Egypt, stay on there as British consul, and become so successful at appropriating and selling the art treasures of the Pharoahs that he rivalled the great tomb-robber Belzoni.

Meanwhile in India more rock-cut temples had come to light. The free-standing Kailasa temple at Ellora, cut into the rock from above like a gigantic intaglio, was discovered in the late 18th century. It was followed by the famous caves at Ajanta and Bagh. "Few remains of antiquity," wrote William Erskine in 1813, "have excited greater curiosity. History does not record any fact that can guide us in fixing the period of their execution, and many opposite opinions have been formed regarding the religion of the people by whom they were made." From the statuary at Elephanta and Ellora, particularly the figures with several heads and many arms, it was clear that these at least were Hindu.[???] But why were they in such remote locations and why had they been so long neglected? What, too, of the plainer caves like Kanheri and the largest of all, Karli in the Western Ghats? Lord Valentia was pretty sure that the sitting figure, surrounded by devotees, at Karli was ''the Boddh''; he had just come from Ceylon where Buddhism was still a living religion, though it appeared to be almost unknown in India.

Other critics who looked to the west for an explanation of anything they found admirable in Indian art, insisted that the excellence of the sculpture indicated the presence of a Greek, Phoenician or even Jewish colony in western India. Yet others looked to Africa: who but the builders of the pyramids could have achieved such monolithic wonders? These theories, were based on the idea that such monuments were exclusive to western India, which had a long history of maritime contacts with the West. They became less credible with the discovery of the so-called Seven Pagodas at Mahabalipuram near Madras. Here, a thousand miles away and on the other side of the Indian peninsula, were a group of temples cut not out of solid rock, but sculpted out of boulders. At first glance they looked like true buildings, a little rounded like old stone cottages, but well proportioned -- up to 55 feet long and 35 feet high -- with porches, pillars and statuary. It was only on closer inspection that one realised that each was a single gigantic stone sculpted into architecture. "Stupendous," declared William Chambers who twice visited the place in the 1770s (though his report had to wait for the Asiatic Society's first publication in 1789), ''of a style no longer in use, indeed closer to that of Egypt''.

Five years later, a further account of the boulder temples, or raths, was submitted by a man who had also seen Elephanta. To his mind there was no question that in style and technique the two were closely related. Had he also seen the intaglio temple of Ellora he might have been tempted to postulate some theory of architectural development; first the cave temple, then the free-standing excavation, and finally the boulder style, freed at last from solid rock. It was as if India's architecture had somehow evolved out of the earth's crust. Elsewhere, stone buildings have always evolved from wooden ones; but in India it was as if architecture was a development of sculpture. The distinctive characteristic of all truly Indian buildings is their sculptural quality. The great Hindu temples look like mountainous accumulations of figures and friezes; even the Taj Mahal, for all its purity of line, stays in the mind as a masterpiece of sculpture rather than of construction.

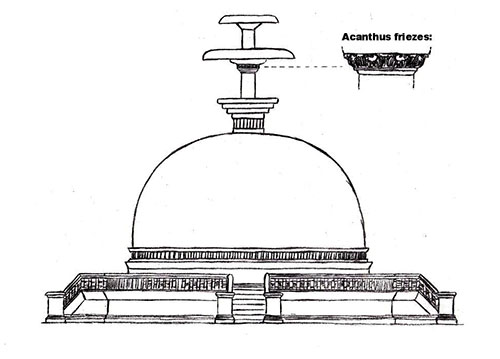

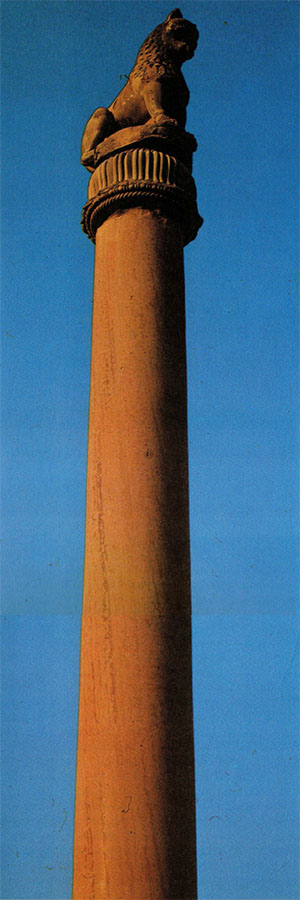

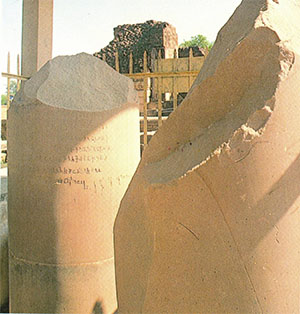

There was yet one other type of ancient monument which had intrigued early visitors. Thomas Coryat, an English eccentric who turned up in Delhi in 1616, was probably the first to take notice of it. South of the Moghul city of Delhi (now Old Delhi) lay the abandoned tombs and forts of half a dozen earlier Delhis (now, confusingly, the site of New Delhi). The ruins stretched for ten miles, overgrown, inhabited by bats and monkeys. But in the middle of this jungle of crumbling masonry Coryat saw something that made him stop; it did not belong. A plain circular pillar, 40 feet high, stuck up through the remains of some dying palace and, in the evening light so proper to ruins, it shone. At a distance he took it for brass, closer up for marble; it is in fact polished sandstone. Of a weight later estimated at 27 tons, it is a single, finely tapered stone, another example of highly developed monolithic craftsmanship. But what intrigued Coryat was the discovery that it was inscribed. Of the two principal inscriptions one was in a script consisting of simple erect letters, a bit like pin-men, which Coryat was sure were Greek. The pillar must then, he thought, have been erected by Alexander the Great, probably "in token of his victorie" over the Indian king Porus in 326 BC.

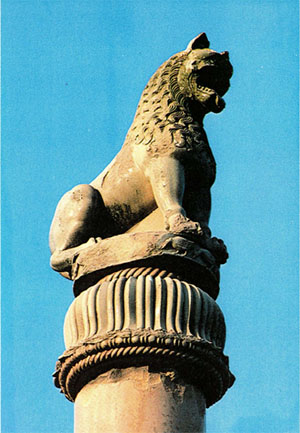

Fifty years later another such pillar was discovered by John Marshall, an East India Company factor who has been called "the first Englishman who really studied Indian antiquities". He was certainly less inclined to jump to wild conclusions. His pillar was "nine yards nine inches high" [27' 9"] and boasted a remarkable capital: ''at the top of this pillar ... is placed a tyger engraven, the neatliest that I have seene in India''. It was actually a lion. But perhaps the most interesting thing about this pillar was that it was in Bihar, a thousand miles from Delhi and many more from the rock-cut monuments around Bombay and Madras.

Writing similar to that found on the Delhi pillar was also found on some of the cave temples; and at Karli there was actually a small pillar outside the cave. Clearly all these monuments were somehow connected. But it was doubtful whether Alexander had ever reached Delhi, let alone Bihar. The existence of a similar pillar there put paid to Coryat's idea of their commemorating Alexander's victories, although the possibility that the letters were some corrupt form of Greek would linger on for many years.

With the foundation of the Asiatic Society there was at last a forum in which a concerted investigation into all these monuments could take place. Reports of more pillars and caves were soon trickling in. Jones himself was rightly convinced that the mystery of who created them, when and why, could be solved only if the inscriptions could be translated. Some ancient civilisation, some foreign conqueror perhaps, or some master craftsman, seemed to be crying out for recognition. Another breakthrough seemed imminent; and with it another chunk of India's lost history might be restored.

Thanks to Charles Wilkins, the man who preceded Jones as a Sanskritist, progress was at first encouraging. At one of the earliest meetings of the Society he reported on a new pillar, also in Bihar.Sometime, in the month of November in the year 1780 I discovered in the vicinity of the Town of Buddal, near which the Company has a factory, and which at that time was under my charge, a decapitated monumental pillar which at a little distance had very much the appearance of the trunk of a coconut tree broken off in the middle. It stands in a swamp overgrown with weeds near a small temple .... Upon my getting close enough to the monument to examine it, I took its dimensions and made a drawing of it. ... At a few feet above the ground is an inscription, engrained in the stone, from which I took two reversed impressions with printer's ink. I have lately been so fortunate as to decipher the character.

Though very different from Devanagari, the modern script used for Sanskrit, it was clearly related to it and Wilkins was not surprised to discover that the language was in fact Sanskrit. To historians the translation was a disappointment; the Buddal pillar told them nothing of interest. But the deciphering was an important development. Nowadays it is recognised that the modern Devanagari script has passed through three distinct stages; first the pin-men script that Coryat thought was Greek (Ashoka Brahmi); second a more ornate, chunky script (Gupta Brahmi); and third, a more curved and rounded script (Kutila) from which springs the washing-on-the-line script of Devanagari. The Buddal pillar was Kutila, and once Wilkins had established that it had some connection with Devanagari, the possibility of working backwards to the earlier scripts was dimly perceived.

As if to illustrate this, Wilkins next surprised his colleagues by teasing some sense out of an inscription written in Gupta Brahmi. It came from a cave near Gaya which had been known for some time though never visited; a Mr Hodgekis, who tried, "was assassinated on his way to it''. Encouraged by Warren Hastings, John Harrington, the secretary of the Asiatic Society, was more successful and found the cave hidden behind a tree near the top of a hill. The character of the inscription, according to Wilkins, was ''undoubtedly the most ancient of any that have hitherto come under my inspection. But though the writing is not modern, the language is pure Sanskrit.'' Wilkins, tantalising as ever about how he made his breakthrough, apparently divined that the inscription was in verse. It was the discovery of the metre that somehow helped him to the successful decipherment. But again, there was little in this new translation to satisfy the historian's thirst for facts.

A far more promising approach to the problem, indeed a short cut, seemed to be heralded in a letter to Jones from Lieutenant Francis Wilford, a surveyor and an enthusiastic student of all things oriental, who was based at Benares. Jones had been sent copies of inscriptions found at Ellora and written in Ashoka Brahmi, the still undeciphered pin-men. He had probably sent them to Wilford because Benares, the holy city of the hindus, was the most likely place to find a Brahmin who might be able to read them. In 1793 Wilford announced that he had found just such a man.I have the honour to return to you the facsimile of several inscriptions with an explanation of them. I despaired at first of ever being able to decipher them ... However, after many fruitless attempts on our part, we were so fortunate as to find at lazst an ancient sage, who gave us the key, and produced a book in Sanskrit, containing a great many ancient alphabets formerly in use in different parts of India. This was really a fortunate discovery, which hereafter may be of great service to us.

According to the ancient sage, most of Wilford's inscriptions related to the wanderings of the five heroic Pandava brothers from the Mahabharata. At the unspecified time in question they were under an obligation not to converse with the rest of mankind; so their friends devised a method of communicating with them by writing short and obscure sentences on rocks and stones in the wilderness and in characters previously agreed upon betwixt them". The sage happened to have the key to these characters in his code book; obligingly he transcribed them into Devanagari Sanskrit and then translated them.

To be fair to Wilford, he was a bit suspicious about this ingenious explanation of how the inscriptions got there. But he had no doubts that the deciphering and translation were genuine. ''Our having been able to decipher them is a great point in my opinion, as it may hereafter lead to further discoveries, that may ultimately crown our labours with success.'' Above all, he had now located the code book, ''a most fortunate circumstance''.

Poor Wilford was the laughing stock of the Benares Brahmins for a whole decade. They had already fobbed him off with Sanskrit texts, later proved spurious, on the source of the Nile and the origin of Mecca. After the code book there was a geographical treatise on The Sacred Isles of the West, which included early Hindu reference to the British Isles. The Brahmins, to whom Sanskrit had so long remained a sacred prerogative, were getting their own back. One wonders how much Wilford paid his "ancient sage".

Jones was already a little suspicious of Wilford's sources, but on the code book, which was as much a fabrication as the translations supposedly based on it, he reserved judgement until he might see it. He never did. In fact it was never heard of again. But in spite of these disappointments Jones continued to believe that in time this oldest script would be deciphered. He had been sent a copy of the writings on the Delhi pillar and told a correspondent that they ''drive me to despair; you are right, I doubt not, in thinking them foreign; I believe them to be Ethiopian and to have been imported a thousand years before Christ". It was not one of his more inspired guesses and at the time of his death the mystery of the inscriptions and of the monoliths was as dark as ever.

And so it remained until the labours of James Prinsep. Jones had given oriental studies a strongly literary bias and his successors continued to concentrate on Sanskrit manuscripts. Archaeological studies were ignored in consequence, and so were inscriptions. Wilkins' few translations had led nowhere and the most intriguing of the scripts remained undeciphered. Indeed even the translation of the Gupta Brahmi script from the cave at Gaya was forgotten in the general waning of interest; it would have to be deciphered all over again.

During his first twelve years in India Prinsep confined his attention to scientific matters. He was sent to Benares to set up a second mint and while there redesigned the city's sewers. He also contributed a few articles to the Asiatic Society's journal (''Descriptions of a Pluviometer and Evaporameter", ''Note on the Magic Mirrors of Japan", etc).

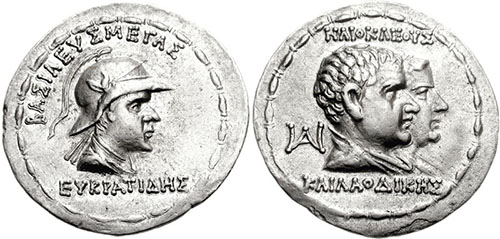

But in 1830 he was recalled to Calcutta as assistant to the Assay-Master, Horace Hayman Wilson, who was also secretary of the Asiatic Society and an eminent Sanskrit scholar. At the time Wilson was puzzling over the significance of various ancient coins that had recently been found in Rajasthan and the Punjab. Prinsep helped to catalogue and describe them, and it was in attempting to decipher their legends that his interest in the whole question of ancient inscriptions was aroused. Although his ignorance of Sanskrit was undoubtedly a handicap, here, in the deciphering of scripts, was a field in which his quite exceptional talent for minute and methodical study could be deployed to brilliant advantage.

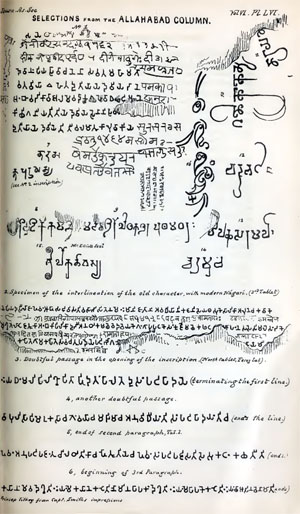

Since Jones' day another pillar like that at Delhi had been found at Allahabad; in addition to a Persian inscription of the Moghul period, it displayed a long inscription in each of the two older scripts (Ashoka Brahmi and Gupta Brahmi). A report had also been received of a rock in Orissa covered with the same two scripts. In 1833 Prinsep prevailed on a Lieutenant Burt, one of several enthusiastic engineers and surveyors, to take an exact impression of the Allahabad pillar inscription.

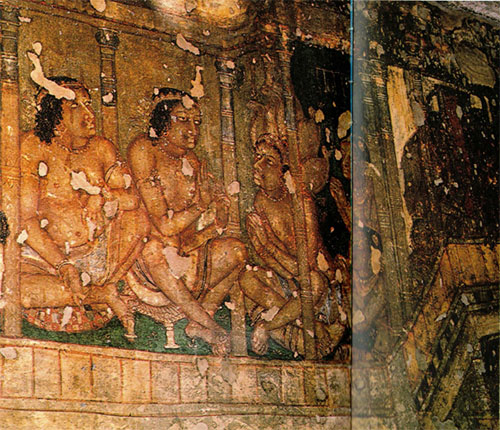

The facsimiles reached Prinsep in early 1834. With an eminent Sanskritist, the Rev W. H. Mill, he soon resolved the problem of the Gupta Brahmi. This was the script that Wilkins had deciphered nearly 50 years before, though his achievement had since been forgotten. The same thing was not likely to happen again; for this time the inscription had something to tell. Evidently it had been engraved on the instructions of a king called Samudragupta. It recorded his extensive conquests and it mentioned that he was the son of Chandragupta. The temptation to assume that this Chandragupta was the same as Jones' Chandragupta, the Sandracottus of the Greeks, was almost irresistible. But not quite. For one thing Jones' Chandragupta had not, according to the Sanskrit king lists, been succeeded by a Samudragupta; they did, however, mention several other Chandraguptas. But if Prinsep and Mill were disappointed at having to deny themselves the simplest and most satisfying of identifications, there would be compensation. They had raised the veil on a dynasty now known as the Imperial Guptas. According to the Allahabad inscriptions Samudragupta had ''violently uprooted'' nine kings and annexed their kingdoms. His rule stretched right across northern India and deep into the Deccan. Politically, here was an empire to rival that of Jones' Chandragupta. But, more important, the Gupta period, about AD 320-460, would soon come to be recognised as the golden age of classical Indian culture. To this period belong many of the frescoes of Ajanta, the finest of the Sarnath and Mathura sculptures, and the plays and poems of Kalidasa, ''the Indian Shakespeare".

But at the time Prinsep and Mill knew no more about these Guptas than what the pillar told them -- and much of that they were inclined to regard as royal hyperbole and therefore unreliable. Prinsep, anyway, was more interested in the scripts than in their historical interpretation. Unlike Jones, he did not indulge in grand theories. He was not a classical scholar, not even a Sanskritist, but a pragmatic, dedicated scientist.

In between experimenting with rust-proof treatments for the new steamboats to be employed on the Ganges, he wrestled next with the Ashoka Brahmi pin-men on the Allahabad column. Coryat's idea that it was some kind of Greek was back in fashion. One scholar claimed to have identified no less than seven letters of the Greek alphabet and another had actually read a Greek name written in this script on an ancient coin. Prinsep was sceptical. The Greek name was only Greek if read upside down. [???!!!] Turn it round and the pinmen letters were just like those on the pillars.

But as yet he had no solution of his own. ''It would require an accurate acquaintance with many of the languages of the East, as well as perfect leisure and abstraction from other pursuits to engage upon the recovery of this lost language.'' He guessed that it must be Sanskrit and thought the script looked simpler than the Egyptian hieroglyphs. It was still beyond him, though, and he could only hope that someone else in India would take up the challenge ''before the indefatigable students of Bonn and Berlin''.

No one reacted directly to this appeal, but in far away Kathmandu the solitary British resident at the Court of Nepal, Brian Houghton Hodgson, read his copy of the Society's journal and immediately dashed off a pained note. No man made more contributions to the discovery of India than Hodgson, or researched in so many different fields. From his outpost in the Himalayas he deluged the Asiatic Society with so many reports that it is hardly surprising some were mislaid. This was a case in point. "Eight or ten years ago" (so some time in the mid 1820s), he had sent in details of two more inscribed pillars. Prinsep could not find them. But Hodgson also disclosed that he had now found yet a third. It was at Bettiah (Lauriya Nandangarh) in northern Bihar and, like the others, very close to the Nepalese frontier. Could they then have been erected as boundary markers?

More intriguing was the facsimile of the inscription on this pillar which Hodgson thoughtfully enclosed. It was Ashoka Brahmi and Prinsep placed it alongside his copies of the Delhi and Allahabad inscriptions. Again he started to look for clues, concentrating this time on separating the shapes of the individual consonants from the vowels which were in the form of little marks festooning them. Darting from one facsimile to the other to verify these, he suddenly experienced that shiver down the spine that comes with the unexpected revelation. "Upon carefully comparing them, [the three inscriptions] with a view to finding any other words that might be common to them ... I was led to a most important discovery; namely that all three inscriptions were identically the same.''

Any surprise that he had not noticed this before must be tempered by the fact that the inscriptions, all of 2,000 years old, were far from perfect. Many letters had been worn away and in one case much of the original inscription had been obliterated by a later one written on top of it. The copies from which Prinsep worked also left much to be desired. Apart from the errors inevitable when someone tried to copy a considerable chunk of writing in totally unfamiliar characters, one copyist working his way round the pillar had managed to transpose the first and second halves of every line.

By correlating all three versions it was now possible to obtain a near perfect fair copy. At the same time even the cautious Prinsep could not resist offering a few conjectures ''on the origin and nature of these singular columns, erected at places so distant from each other and all bearing the same inscription''.Whether they mark the conquests of some victorious raja; -- whether they are, as it were, the boundary pillars of his dominions; -- or whether they are of a religious nature ... can only be satisfactorily solved by the discovery of the language.

Clearly this people, this kingdom, this religion, was of significance to the whole of north India. It was altogether too big a subject to be left to chance. Prinsep, well placed now as Secretary of the Asiatic Society to assess the various materials (Wilson had retired to England), resolved to undertake the translation himself. In 1834 he tried the obvious line of relating this script to that of the Gupta Brahmi which he had just deciphered. For each, he drew up a table showing the frequency with which individual letters occurred, the idea being that those which occurred approximately the same number of times in each script might be the same letters.[???!!!] It was worth a try, but obviously would work only if both were in the same language and dealt with the same sort of subject. They did not, in fact they were not even in the same language, and Prinsep soon gave up this approach.[???!!!]

Next he tried relating the individual letters from each of the two scripts which had a similar conformation. This was more encouraging. He tentatively identified a handful of consonants and heard from a correspondent in Bombay, who was working on the cave temple inscriptions, that he too had identified these and five others. Armed with these few identifications, he attempted a translation, hoping that the sense might reveal the rest. But some of his letters were wrongly identified, and anyway he was still barking up the wrong tree in imagining that the language was pure Sanskrit. The attempt was a dismal failure. Discouraged, but far from defeated, Prinsep returned to the drawing board.

For the next four years he pushed himself physically and mentally towards the brink. Outside his office Calcutta was changing. The Governor-General had a new residence modelled on Kedleston Hall, but considerably grander: the dining-room could seat 200 and over 500 sometimes attended the Government House balls. Society was less boorish than in Jones' day. The hookah had gone out and so had most of the ''sooty bibis''; the memsahibs were taking over. But the only innovation Prinsep would have been aware of was the flapping punkah, or fan, above his desk. Now the Assay-Master, he spent all day at the mint and all evening with his coins and inscriptions or conferring with his pandits. By seven in the morning he was back at his desk. There is no record, as with Jones, of an early morning walk or ride, no mention of leisure. Instead he lived vicariously, through the endeavours and successes of his correspondents.

Jones, as president and founder of the Asiatic Society, and the most respected scholar of his age, had both inspired and dominated his fellows. Prinsep was just the opposite. He was the secretary of the Society, not the President, a plain Mr with few pretensions other than his total dedication. But this in itself was enough. His enthusiasm communicated itself to others and was irresistible. When he asked for coins and inscriptions they came flooding in from every corner of India. Painstakingly he acknowledged, translated and commented upon them. By 1837 he had an army of enthusiasts -- officers, engineers, explorers, political agents and administrators -- informally collecting for him. Colonel Stacy at Chitor, Udaipur and Delhi, Lieutenant A. Connolly at Jaipur, Captain Wade at Ludhiana, Captain Cautley at Sahranpur, Lieutenant Cunningham at Benares, Colonel Smith at Patna, Mr Tregear at Jaunpur, Dr Swiney in Upper India .... the list was long.

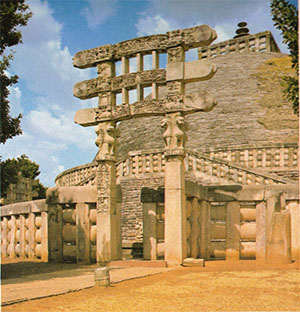

It was from one of these correspondents, Captain Edward Smith, an engineer at Allahabad, that in 1837 there came the vital clue to the mysterious script. On Prinsep's suggestion, Smith had made the long journey into Central India to visit an archaeological site of exceptional interest at Sanchi near Bhopal. Prinsep wanted accurate drawings of its sculptural wonders and facsimiles of an inscription in Gupta Brahmi which had not yet been translated. Smith obliged with both of these and, noticing some further very short inscriptions on the stone railings round the main shrine, took copies of them just for good measure.These apparently trivial fragments of rude writing [wrote Prinsep] have led to even more important results than the other inscriptions. They have instructed us in the alphabet and language of these ancient pillars and rock inscriptions which have been the wonder of the learned since the days of Sir William Jones, and I am already nearly prepared to render the Society an account of the writing on the lat [pillar] at Delhi. With no little satisfaction that, as I was the first to analyse these unknown symbols ... so I should now be rewarded with the completion of a discovery I then despaired of accomplishing for want of a competent knowledge of the Sanskrit language.

Typically, Prinsep then launched into a long discussion of the sculpture and other inscriptions, keeping his audience and readers on tenterhooks for another 10 pages. But to Lieutenant Alexander Cunningham, his protege in Benares, he had already announced the discovery in a letter.23 May 1837.

My dear Cunningham, Hors de department de mes etudes! [Out of my department studies!] [a reference to a Mohammedan coin that Cunningham had sent him]. No, but I can read the Delhi No. 1 which is of more importance; the Sanchi inscriptions have enlightened me. Each line is engraved on a separate pillar or railing. Then thought I, they must be the gifts of private individuals where names will be recorded. All end in danam [in the original characters] -- that must mean 'gift' or 'given'.[???!!!] Let's see ...Table 1. John Marshall's phasing at Sanchi.

Phase / Date range / Monuments / Inscriptions / Sculptures

I / 3rd century BC / Stupa 1: brick core; Pillar 10; Temple 40 (apsidal); Temple 18 (apsidal) / Ashokan inscription (c. 269-232 BC) / Elephant capital from Temple 40 (?)

Sanchi Pillar 10

Sanchi Temple 40

Sanchi Temple 18

Elephant capital from East Gate of Stupa 1

Elephant capital from Sankissa, one of the Pillars of Ashoka, 3rd century BCE

II / 2nd-1st century BC / Stupas 2, 3, 4; Stupa 1: casing and railings; Temples 18 and 40 (enlargements); Building 8 (platformed monastery) / Donative inscriptions on Stupa 1, 2, and 3 railings; reliquary inscriptions from Stupas 2 and 3. / Pillar by Stupa 2; Pillar 25.

III / 1st-3rd century AD / Stupa 1: gateway carvings. / Southern gateway inscription of Shatakarni (c. AD 25)....

-- Sanchi as an archaeological area, by Julia Shaw, 2013

He proved his point by immediately translating four such lines, and then turned to the first line of the famous pillar inscriptions: Devam piya piyadasi raja hevam aha, "the most-particularly-loved-of-the-gods raja declareth thus". He was not quite right; the r should have been l, laja not raja. But he was near enough. Danam giving him the d, the n and the m, all very common and hitherto unidentified, had been just enough to tip the balance.

With the help of a distinguished pandit he immediately set about the long pillar inscriptions. It was June, the most unbearable month of the Calcutta year; to concentrate the mind even for a minute is a major achievement. By now the Governor-General and the rest of Calcutta society were in the habit of taking themselves off to the cool heights of Simla at such a time. Prinsep stayed at his desk. The deciphering was going well but he had at last acknowledged the unexpected difficulty of the language not being Sanskrit.[???] As Hodgson had suggested, it was closer to Pali, the sacred language of Tibet, or in other words it was one of the Prakrit languages, vernacular derivations of the classical Sanskrit. This made it difficult to pin down the precise meaning of many phrases. Prinsep also had, himself, to engrave all the plates for the script that would illustrate his account. Nevertheless, in the incredibly short space of six weeks, his translation was ready and he announced it to the Society. As usual he treated them to a long preamble on the discoveries that had led up to it and on the difficulties it still presented. But, unlike other inscriptions, these had one remarkable feature in their favour. There was an almost un-Indian frankness about the language, no exaggeration, no hyperbole, no long lists of royal qualities. Instead there was a bold and disarming directness:[???!!!]Thus spake King Devanampiya Piyadasi. In the twenty-seventh year of my annointment I have caused this religious edict to be published in writing. I acknowledge and confess the faults that have been cherished in my heart ...

The king had obviously undergone a religious conversion and, from the nature of the sentiments expressed, it was clearly Buddhism that he had adopted. The purpose of his edicts was to promote this new religion, to encourage right thinking and right behaviour, to discourage killing, to protect animals and birds, and to ordain certain days as holy days and certain men as religious administrators. The inscriptions ended in the same style as they had begun.In the twenty-seventh year of my reign I have caused this edict to be written; so sayeth Devanampiya; ''Let stone pillars be prepared and let this edict of religion be engraven thereon, that it may endure into the remotest ages."

Something about both the language and the contents was immediately familiar: it was Old Testament. Even Prinsep could not resist the obvious analogy -- "we might easily cite a more ancient and venerable example of thus fixing the law on tablets of stone". Perhaps it was just out of reverence that he called them edicts rather than commandments. But the message was clear enough. Here was an Indian king uncannily imitating Moses[???!!!], indeed going one better; as well as using tablets of stone, he had created these magnificent pillars to bear his message through the ages.

But who was this king? "Devanampiya Piyadasi" could be a proper name but it was not one that appeared in any of the Sanskrit king lists. Equally it could be a royal epithet, "Beloved of the Gods and of gracious mien''. At first Prinsep thought the former. In Ceylon a Mr George Turnour had been working on the Buddhist histories preserved there and ad just sent in a translation that mentioned a king Piyadasi who was the first Ceylon king to adopt Buddhism. This fitted well; but what was a king of Ceylon doing scattering inscriptions all over northern India? One of the edicts actually claimed that the king had planted trees along the highways, dug wells, erected traveller's rest houses etc. How could a Sinhalese king be planting trees along the Ganges?

A few weeks later Turnour himself came up with the answer. Studying another Buddhist work he discovered that Piyadasi was also the normal epithet of a great Indian sovereign, a contemporary of the Ceylon Piyadasi, and that this king was otherwise known as Ashoka. It was further stated that Ashoka was the grandson of Chandragupta and that he was consecrated 218 years after the Buddha's enlightenment.

Suddenly it all began to make sense. Ashoka was already known from the Sanskrit king lists as a descendant of Chandragupta Maurya (Sandracottus) and, from Himalayan Buddhist sources, as a legendary patron of early Buddhism. Now his historicity was dramatically established. Thanks to the inscriptions, from being just a doubtful name, more was suddenly known about Ashoka than about any other Indian sovereign before AD 1100. As heir to Chandragupta it was not surprising that his pillars and inscriptions were so widely scattered. The Mauryan empire was clearly one of the greatest ever known in India, and here was its noblest scion speaking of his life and work through the mists of 2,000 years. It was one of the most exciting moments in the whole story of archaeological discovery.

-- "Ashoka," Excerpt from India Discovered, by John Keay

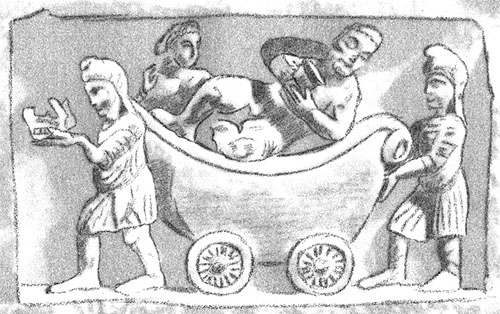

A 13th-century fresco of Sylvester I and Constantine the Great, showing the purported Donation (Santi Quattro Coronati, Rome)

The Donation of Constantine (Latin: Donatio Constantini) is a forged Roman imperial decree by which the 4th-century emperor Constantine the Great supposedly transferred authority over Rome and the western part of the Roman Empire to the Pope. Composed probably in the 8th century, it was used, especially in the 13th century, in support of claims of political authority by the papacy.[1] In many of the existing manuscripts (handwritten copies of the document), including the oldest one, the document bears the title Constitutum domini Constantini imperatoris.[2] The Donation of Constantine was included in the 9th-century collection Pseudo-Isidorean Decretals.

Lorenzo Valla, an Italian Catholic priest and Renaissance humanist, is credited with first exposing the forgery with solid philological arguments in 1439–1440,[3] although the document's authenticity had been repeatedly contested since 1001.[1]

The text is purportedly a decree of Roman Emperor Constantine I, dated 30 March—a year mistakenly said to be both that of his fourth consulate (315) and that of the consulate of Gallicanus (317).[4] In it "Constantine" professes Christianity (confessio) and entitles to Pope Sylvester several imperial insignia and privileges (donatio), as well as the Lateran Palace. Rome, the rest of Italy, and the western provinces of the empire are made over to the papacy.[5]

The text recounts a narrative founded on the 5th-century hagiography the Acts of Sylvester. This fictitious tale describes the sainted Pope Sylvester's rescue of the Romans from the depredations of a local dragon and the pontiff's miraculous cure of the emperor's leprosy by the sacrament of baptism.[5] The story was rehearsed by the Liber Pontificalis; by the later 8th century the dragon-slayer Sylvester and his apostolic successors were rewarded in the Donation of Constantine with temporal powers never in fact exercised by the historical Bishops of Rome under Constantine.

In his gratitude, "Constantine" determined to bestow on the seat of Peter "power, and dignity of glory, vigor, and imperial honor," and "supremacy as well over the four principal sees: Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Constantinople, as also over all the churches of God in the whole earth". For the upkeep of the church of Saint Peter and that of Saint Paul, he gave landed estates "in Judea, Greece, Asia, Thrace, Africa, Italy and the various islands". To Sylvester and his successors he also granted imperial insignia, the tiara, and "the city of Rome, and all the provinces, places and cities of Italy and the western regions".[6][7]

The Donation sought reduction in the authority of Constantinople; if Constantine had elevated Sylvester to imperial rank before the 330 inauguration of Constantinople, then Rome's patriarch had a lead of some fifteen years in the contest for primacy among the patriarchates. Implicitly, the papacy asserted its supremacy and prerogative to transfer the imperial seat; the papacy had consented to the translatio imperii to Byzantium by Constantine and it could wrest back the authority at will.[5]