XVIII. On the Chronology of the Hindus

by Captain Francis Wilford

Asiatic Researches, Vol. V, P. 241

1799

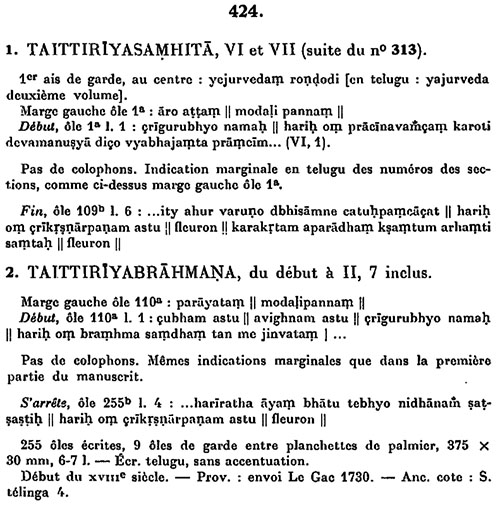

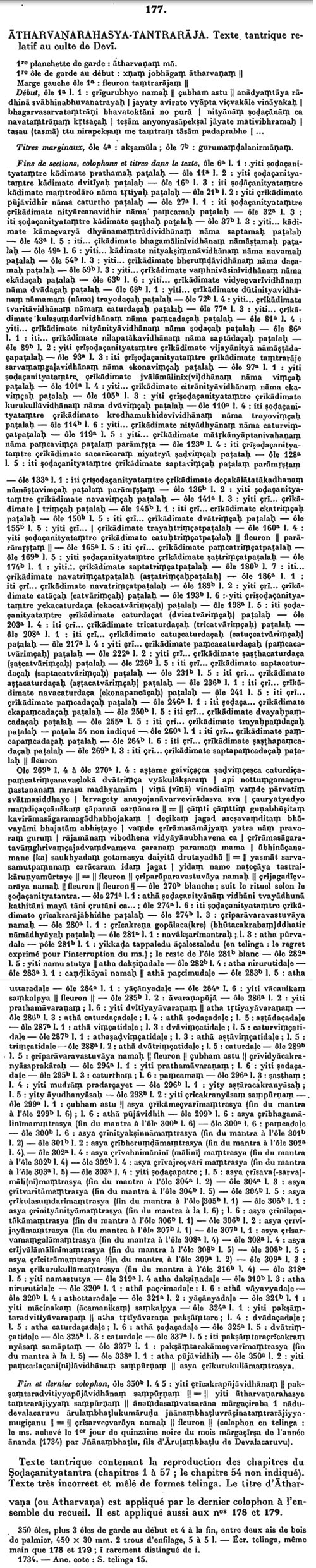

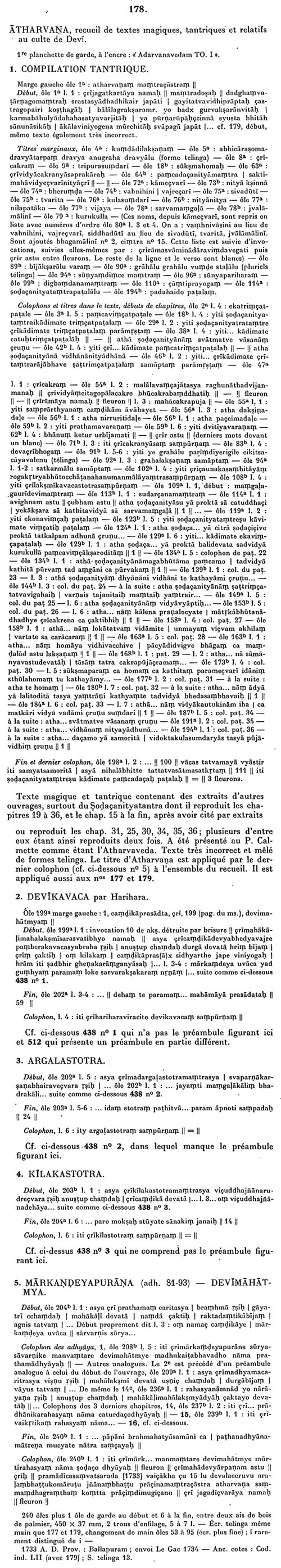

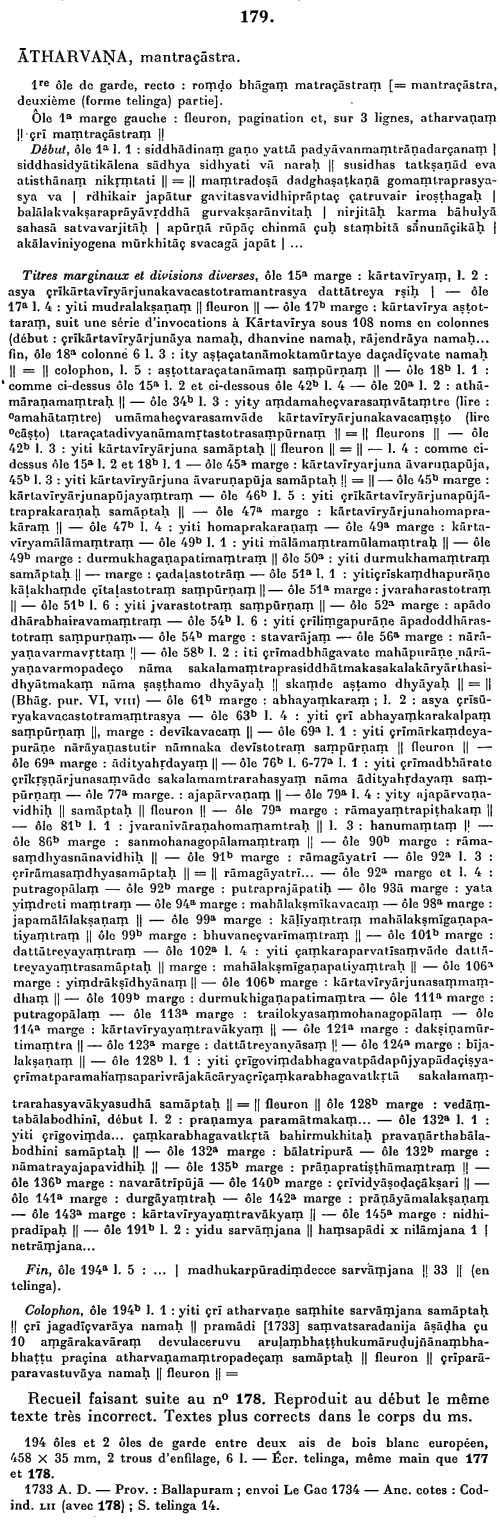

52. Sandrocottus. It was Sir William Jones, the Founder and President of the Society instituted in Bengal for inquiry into the History and Antiquities, the Arts, Sciences and Literature of Asia, who died on 27th April 1794, that suggested for the first time an identification to the notice of scholars. In his 'Tenth Anniversary Discourse' delivered by him on 28th February 1793 on "Asiatic History, Civil and Natural," referred to the so-called discovery by him of the identity of Candragupta, the Founder of the Maurya Dynasty of the Kings Magadha, with Sandrocottus of the Greek writers of Alexander's adventures, thus:"The Jurisprudence of the Hindus and Arabs being the field, which I have chosen for my peculiar toil, you cannot expect, that I should greatly enlarge your collection of historical knowledge, but I may be able to offer you some occasional tribute, and I cannot help mentioning a discovery which accident threw in my way, though my proofs must be reserved for an essay, which I have destined for the fourth volume of your Transactions. To fix the situation of that Palibothra, (for there may have been several of the name) which was visited and described by Megasthenes, had always appeared a very difficult problem, for, though it could not have been Prayaga where no ancient metropolis ever stood, nor Canyacubja which has no epithet at all resembling the word used by the Greeks, nor Gaur, otherwise called Lacshmanavati, which all know to be a town comparatively modern, yet we could not confidently decide that it was Pataliputra, though names and most circumstances nearly correspond, because that renowned capital extended from the confluence of the Sone and the Ganges to the site of Patna, while Palibothra stood at the junction of the Ganges and Erranaboas, which the accurate M. D'Anville had pronounced to be "Yamuna", but this only difficulty was removed when I found in a Classical Sanskrit book near two thousand years old, that Hiranyabahu or golden-armed, which the Greeks changed to Erranaboas, or the river with a lovely murmur, was in fact another name for the Sona itself, though Megasthenes from ignorance or inattention, has named them separately.1 [Asiatic Researches, IV. 10-11.] This discovery led to another of greater moment, for Chandragupta, who, from a military adventurer, became like Sandrocottus, the sovereign of Upper Hindustan, actually fixed the seat of his empire at Pataliputra, where he received ambassadors from foreign princes, and was no other than that very Sandrocottus who concluded a treaty with Seleucus Nicator, so that we have solved another problem to which we before alluded, and may in round numbers consider the twelve and three hundredth years before Christ as two certain epochs between Rama who conquered Silan a few centuries after the flood, and Vicramaditya who died at Ujjayini fifty-seven years before the beginning of our era."

53. The passage regarding Candragupta's date is found in Justinius, Epitoma Pompet Trogi, xv 4 and Mr. McCrindle translated it as follows:2 [Mendelsohn's edition (Leipzig, 1879), I. 426.]"[Seleucus] carried on many wars in the East after the division of the Macedonian kingdom between himself and the other successor of Alexander, first seizing Babylonia, and then reducing the Bactrians, his power being increased by the first success. Thereafter he passed into India, which had, since Alexander's death, killed his prefects, thinking that the yoke of slavery had been shaken off from its neck. The author of its freedom had been Sandrocottus, but when victory was gained he had changed the name of freedom to that of bondage. For, after he had ascended the throne, he himself oppressed with servitude the very people which he had rescued from foreign dominion. Though of humble birth, he was impelled by innate majesty to assume royal power. When king Nandrus,1 [McCrindle's translation, 114.] whom he had offended by his boldness, ordered him to be killed, he had resorted to speedy flight. Sandrocottus, having thus gained the crown, held India at the time when Seleucus was laying the foundations of his future greatness. Seleucus came to an agreement with him, and, after settling affairs in the East, engaged in the war against Antigonus."

The same transactions are referred to by Appianus:"[Seleucus] crossed the Indus and waged war on Androcottus king of the Indians who dwelt about it, until he made friends and entered into relations of marriage with him."

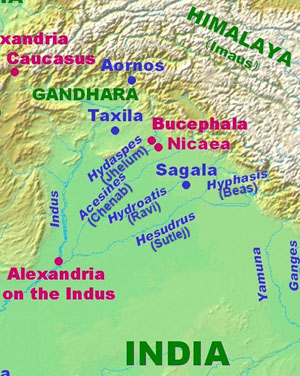

According to Strabo, Seleucus ceded to Chandragupta a tract of land to the west of the Indus and received in exchange five hundred elephants.2 [V. A. Smith, Early History of India, 3rd ed., p 150 f, Krom, Hermes 44, 154 ff.]

The inference drawn is this: Seleucus I Nikator of Syria (BC 312- 280), "arrived in Cappadocia in the autumn of 302 [the year preceding the battle of Ipsos]. The march from India to there must have required at least two summers. Consequently, the peace with Chandragupta has to be placed about the summer of 304, or at the latest in the next winter."3 [Beloch's Gricch, Gesch, 8, 1, 146, n 3.] We know from various sources that Megasthenes became the ambassador of Seleucus at Chandragupta's court.4 [Schwanbeck, Megasthenes Indica (Bonn. 1876), p 19, C. Muller Fragmenta Historcorum Graecorum, vol 11 (Paris 1848), p. 898, McCrindle, IA, VI, 115.]

It follows from these statements that Chandragupta ascended the throne between Alexander's death (BC 323) and the treaty with Seleucus (BC 304)."

54. Earlier in the same discourse Sir William had mentioned his authorities for the statement that Candragupta became sovereign of upper Hindusthan, with his Capital at Pataliputra. "A most beautiful poem," said he "by Somadeva, comprising a long chain of instructive and agreeable stories, begins with the famed revolution at Pataliputra by the murder of king Nanda with his eight sons, and the usurpation of Chandragupta, and the same revolution is the subject of a tragedy in Sanskrit entitled 'The Coronation of Chandra.'"1 [Ibid 6.] Thus he claimed to have identified Palibothra with Pataliputra and Sandrokottus with Candragupta, and to have determined 300 BC "in round numbers" as a certain epoch between two others which he called the conquest of Silan by Rama: "1200 BC," and the death of Vikramaditya at Ujjain in 57 BC.

In the Discourse referred to, Sir William barely stated his discovery, adding "that his proofs must be reserved" for a subsequent essay, but he died before that essay could appear.

55. The theme was taken immediately by Col. [Captain Francis] Wilford in Volume V of the Asiatic Researches. Wilford entered into a long and fanciful disquisition on Palibothra, and rejected Sir William's identification of it with Pataliputra, but he accepted the identification of Sandrocottus with Candragupta in the following words: —"Sir William Jones from a poem written by Somadeva and a tragedy called the Coronation of Chandra or Chandragupta discovered that he really was the Indian king mentioned by the historians of Alexander under the name of Sandrocottus. These poems I have not been able to procure, but I have found another dramatic piece entitled Mudra-Rachasa,1 [This spelling shows that Wilford saw not the Sanskrit drama but some vernacular visions of it.] which is divided into two parts, the first may be called the Coronation of Chandra."2 [Asiatic Researches, V, 262. Wilford wrongly names the author of the drama as Amanta (or Ananta).]

[Horace Hayman] Wilson further amended the incorrect authorities relied on by Sir William Jones, and said in his Preface to Mudra-Rakshasa3 [Theatre of the Hindus, Vol. II.] that by Sir William's "a beautiful poem by Somadeva" was "doubtless meant the large collection of tales by Somabhatta the Vrihat-katha."4 [Wilson again is not quite correct in his Bibiography. Somadeva's large collection of tales is entitled Kathasarit sagara and is an adaptation into Sanskrit verse of an original work in the Paisaci language called Brihat Katha, composed by one Gunadhya.]

56. Max Muller then elaborated the discovery of this identity in his Ancient Sanskrit Literature. To him this identity was a settled incontrovertible fact. On the path of further research, he examined the chronology of the Buddhists according to the Northern or the Chinese and the Southern or the Ceylonese traditions, and summed this up:"Everything in Indian Chronology depends upon the date of Chandragupta. Chandragupta was the grand-father of Asoka, and the contemporary of Selukus Nikator. Now, according to the Chinese chronology, Asoka would have lived, to waive the minor differences, 850 or 750 BC, according to Ceylonese Chronology, 315 B.C. Either of these dates is impossible because it does not agree with the chronology of Greece."

'Everything in Indian Chronology depends upon the date of Chandragupta' is the declaration. How is that date to be fixed? The Puranic accounts were of course beneath notice. The Buddhist chronologies were conflicting, and must be ignored. The Greek synchronism comes to his rescue: "There is but one means by which the history of India can be connected with that of Greece, and its chronology must be reduced to its proper limits," that is, by the clue afforded by "the name of Sandrocottus or Sandrocyptus, the Sanskrit Chandragupta."

From classical writers — Justin, Arrian, Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, Quintus Curtius, and Plutarch — a formidable array, all of whom however borrowed their account from practically the same sources — he puts together the various statements concerning Sandrocottus, and tries to show that they all tally with the statements made by Indian writers about the Maurya king Candragupta. "The resemblance of this name," says he, "with the name of Sandrocottus or Sandrocyptus was first, I believe, pointed out by Sir William Jones. [Captain Francis] Wilford, [Horace Hayman] Wilson, and Professor [Christian] Lassen have afterwards added further evidence in confirmation of Sir W. Jones's conjecture, and although other scholars, and particularly M. Troyer in his edition of the Rajatarangini, have raised objections, we shall see that the evidence in favour of the identity of Chandragupta and Sandrocottus or Sandrocyptus is such as to admit of no reasonable doubt." Max Muller only repeats that the Greek accounts of Sandrocottus and the Indian accounts of Chandragupta agree in the main, both speaking of a usurper who either was base-born himself or else overthrew a base-born predecessor, and that this essential agreement would hold whether the various names used by Greek writers — Xandrames, Andramas, Aggraman, Sandrocottus and Sandrocyptus — should be made to refer to two kings, the overthrown and the overthrower, or all to one, namely the overthrower himself, though personally he is inclined to the view that the first three variations refer to the overthrown, and the last two to the overthrower. He explains away the difficulty in identifying the sites of Palibothra and Pataliputra geographically by "a change in the bed of the river Sone." He passes over the apparent differences in detail between the Greek statements on the one hand and the Hindu and Buddhist versions on the other quite summarily, declaring that Buddhist fables were invented to exalt, and the Brahmanic fables to lower Chandragupta's descent! Lastly with respect to chronology the Brahmanic is altogether ignored, and the Buddhist is "reduced to its proper limits," that is, pulled down to fit in with Greek chronology.

-- History of Classical Sanskrit Literature, by Kavyavinoda, Sahityaratnakara M. Krishnamachariar, M.A., M.I., Ph.D., Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of London (Of the Madras Judicial Service), Assisted by His Son M. Srinivasachariar, B.A., B.L., Advocate, Madras, 1937

It may not here be out of place to offer a few observations on the identification of Chandragupta and Sandrocottus. It is the only point on which we can rest with anything like confidence in the history of the Hindus, and is therefore of vital importance in all our attempts to reduce the reigns of their kings to a rational and consistent chronology. It is well worthy, therefore, of careful examination; and it is the more deserving of scrutiny, as it has been discredited by rather hasty verification and very erroneous details.

Sir William Jones first discovered the resemblance of the names, and concluded Chandragupta to be one with Sandrocottus (As. Res. vol. iv. p. 11). He was, however, imperfectly acquainted with his authorities, as he cites "a beautiful poem” by Somadeva, and a tragedy called the coronation of Chandra, for the history of this prince. By the first is no doubt intended the large collection of tales by Somabhatta, the Vrihat-Katha, in which the story of Nanda's murder occurs: the second is, in all probability, the play that follows, and which begins after Chandragupta’s elevation to the throne. In the fifth volume of the Researches the subject was resumed by the late Colonel Wilford, and the story of Chandragupta is there told at considerable length, and with some accessions which can scarcely be considered authentic. He states also that the Mudra-Rakshasa consists of two parts, of which one may be called the coronation of Chandragupta, and the second his reconciliation with Rakshasa, the minister of his father. The latter is accurately enough described, but it may be doubted whether the former exists.

Colonel Wilford was right also in observing that the story is briefly related in the Vishnu-Purana and Bhagavata, and in the Vrihat-Katha; but when he adds, that it is told also in a lexicon called the Kamandaki he has been led into error. The Kamandaki is a work on Niti, or Polity, and does not contain the story of Nanda and Chandragupta. The author merely alludes to it in an honorific verse, which he addresses to Chanakya as the founder of political science, the Machiavel of India.

The birth of Nanda and of Chandragupta, and the circumstances of Nanda’s death, as given in Colonel Wilford’s account, are not alluded to in the play, the Mudra-Rakshasa, from which the whole is professedly taken, but they agree generally with the Vrihat-Katha and with popular versions of the story. From some of these, perhaps, the king of Vikatpalli, Chandra-Dasa, may have been derived, but he looks very like an amplification of Justin's account of the youthful adventures of Sandrocottus. The proceedings of Chandragupta and Chanakya upon Nanda's death correspond tolerably well with what we learn from the drama, but the manner in which the catastrophe is brought about (p. 268), is strangely misrepresented. The account was no doubt compiled for the translator by his pandit, and it is, therefore, but indifferent authority.

It does not appear that Colonel Wilford had investigated the drama himself, even when he published his second account of the story of Chandragupta (As. Res. vol. ix. p. 93 [p. 94-100]), for he continues to quote the Mudra-Rakshasa for various matters which it does not contain. Of these, the adventures of the king of Vikatpalli, and the employment of the Greek troops, are alone of any consequence, as they would mislead us into a supposition, that a much greater resemblance exists between the Grecian and Hindu histories than is actually the case.

Discarding, therefore, these accounts, and laying aside the marvellous part of the story, I shall endeavour, from the Vishnu and Bhagavata-Puranas, from a popular version of the narrative as it runs in the south of India, from the Vrihat-Katha, [For the gratification of those who may wish to see the story as it occurs in these original sources, translations are subjoined; and it is rather important to add, that in no other Purana has the story been found, although most of the principal works of this class have been carefully examined.] and from the play, to give what appear to be the genuine circumstances of Chandragupta's elevation to the throne of Palibothra.

-- Select Specimens of the Theatre of the Hindus, Translated from Original Sanskrit in Two Volumes, by Horace Hayman Wilson, Volume II, 1871

The accession of Chandragupta to the throne, and more particularly the famous expiation of Chanacya, after the massacre of the Sumalyas, is a famous era in the Chronology of the Hindus; and both may be easily ascertained from the Puranas, and also from the historians of Alexander. In the year 328 B.C. that conqueror defeated Porus; and as he advanced* [Diodor. Sic. lib. XVII. c. 91. Arrian also, &c.] the son of the brother of that prince, a petty king in the eastern parts of the Panjab, fled at his approach, and went to the king of the Gangaridae, who was at that time king Nanda of the Puranas. In the Mudra-rachasa, a dramatic poem, and by no means a rare book, notice is taken of this circumstance. There was, says the author, a petty king of Vicatpalli, beyond the Vindhyan mountains, called Chandra-dasa, who, having been deprived of his kingdom by the Yavanas, or Greeks, left his native country, and assuming the garb of a penitent, with the name of Suvidha, came to the metropolis of the emperor Nanda, who had been dangerously ill for some time. He seemingly recovered; but his mind and intellects were strangely affected. It was supposed that he was really dead, but that his body was re-animated by the soul of some enchanter, who had left his own body in the charge of a trusty friend. Search was made immediately, and they found the body of the unfortunate dethroned king, lying as if dead, and watched by two disciples, on the banks of the Ganges. They concluded that he was the enchanter, burned his body, and flung his two guardians into the Ganges. Perhaps the unfortunate man was sick, and in a state of lethargy, or otherwise intoxicated. Then the prince's minister assassinated the old king soon after, and placed one of his sons upon the throne, but retained the whole power in his own hands. This, however, did not last long; for the young king, disliking his own situation, and having been informed that the minister was the murderer of his royal father, had him apprehended, and put to a most cruel death. After this, the young king shared the imperial power with seven of his brothers; but Chandragupta was excluded, being born of a base woman. They agreed, however, to give him a handsome allowance, which he refused with indignation; and from that moment his eight brothers resolved upon his destruction. Chandragupta fled to distant countries; but was at last seemingly reconciled to them, and lived in the metropolis: at least it appears that he did so; for he is represented as being in, or near, the imperial palace, at the time of the revolution, which took place, twelve years after, Porus's relation made his escape to Palibothra, in the year 328, B.C. and in the latter end of it. Nanua was then assassinated in that year; and in the following, or 327, B. C. Alexander encamped on the banks of the Hyphasis. It was then that Chandragupta visited that conqueror's camp; and, by his loquacity and freedom of speech, so much offended him, that he would have put Chandragupta to death, if he had not made a precipitate retreat, according to Justin* [Lib. xv. c, 4.]. The eight brothers ruled conjointly twelve years, or till 315 years B.C. when Chandragupta was raised to the throne, by the intrigues of a wicked and revengeful priest called Chanacya. It was Chandragupta and Chanacya, who put the imperial family to death; and it was Chandragupta who was said to be the spurious offspring of a barber, because his mother, who was certainly of a low tribe, was called Mura, and her son of course Maurya, in a derivative from; which last signifies also the offspring of a barber: and it seems that Chandragupta went by that name, particularly in the west; for be is known to Arabian writers by the name of Mur, according to the Nubian geographer, who says that he was defeated and killed by Alexander; for these authors supposed that this conqueror crossed the Ganges: and it is also the opinion of some ancient historians in the west.

In the Cumarica-chanda, it is said, that it was the wicked Chanacya who caused the eight royal brothers to be murdered; and it is added, that Chanacya, after his paroxism of revengeful rage was over, was exceedingly troubled in his mind, and so much stung with remorse for his crime, and the effusion of human blood, which took place in consequence of it, that he withdrew to the Sucla-Tirtha, a famous place of worship near the sea on the bank of the Narmada, and seven coss to the west of Baroche, to get himself purified. There, having gone through a most severe course of religious austerities and expiatory ceremonies, he was directed to sail upon the river in a boat with white sails, which, if they turned black, would be to him a sure sign of the remission of his sins; the blackness of which would attach itself to the sails. It happened so, and he joyfully sent the boat adrift, with his sins, into the sea.

This ceremony, or another very similar to it, (for the expense of a boat would be too great), is performed to this day at the Sucla-Tirtha; but, instead of a boat, they use a common earthen pot, in which they light a lamp, and send it adrift with the accumulated load of their sins.

In the 63d section of the Agni-purana, this expiation is represented in a different manner. One day, says the author, as the gods, with holy men, were assembled in the presence of Indra, the sovereign lord of heaven, and as they were conversing on various subjects, some took notice of the abominable conduct of Chanacya, of the atrocity and heinousness of his crimes. Great was the concern and affliction of the celestial court on the occasion; and the heavenly monarch observed, that it was hardly possible that they should ever be expiated.

One of the assembly took the liberty to ask him, as it was still possible, what mode of expiation was requisite in the present case? and Indra answered, the Carshagni. There was present a crow, who, from her friendly disposition, was surnamed Mitra Caca: she flew immediately to Chanacya, and imparted the welcome news to him. He had applied in vain to the most learned divines; but they uniformly answered him, that his crime was of such a nature, that no mode of expiation for it could be found in the ritual. Chanacya immediately performed the Carshagni, and went to heaven. But the friendly crow was punished for her indiscretion: she was thenceforth, with all her tribe, forbidden to ascend to heaven; and they were doomed on earth to live upon carrion.

The Carshagni consists in covering the whole body with a thick coat of cow-dung, which, when dry, is set on fire. This mode of expiation, in desperate cases, was unknown before; but was occasionally performed afterwards, and particularly by the famous Sancaracharya. It seems that Chandragupta, after he was firmly seated on the imperial throne, accompanied Chanacya to the Suclatirtha, in order to get himself purified also.

This happened, according to the Cumarica-chanda, after 300 and 10 and 3000 years of the Cali-yuga were elapsed, which would place this event 210 years after Christ. The fondness of the Hindus for quaint and obscure expressions, is the cause of many mistakes. But the ruling epocha of this paragraph is the following: "After three thousand and one hundred years of the Cali-yuga are elapsed (or in 3101) will appear king Saca (or Salivahana) to remove wretchedness from the world. The first year of Christ answers to 3101 of the Cali-yuga, and we may thus correct the above passage: "Of the Caliyuga, 3100 save 300 and 10 years being elapsed (or 2790), then will Chanacya go to the Suclatirtha."

This is also confirmed in the 63d and last section of the Agni-purana, in which the expiation of Chanacya is placed 312 years before the first year of the reign of Saca or Salivahana, but not of his era. This places this famous expiation 310, or 312 years before Christ, either three or five years after the massacre of the imperial family.

My Pandit, who is a native of that country, informs me, that Chanacya's crimes, repentance, and atonement, are the subject of many pretty legendary tales, in verse, current in the country; part of some he repeated to me.

Soon after, Chandragupta made himself master of the greatest part of India, and drove the Greeks out of the Punjab. Tradition says, that he built a city in the Deccan, which he called after his own name. It was lately found by the industrious and active Major Mackenzie, who says that it was situated a little below Sri-Salam, or Purwutum, on the bank of the Crishna; but nothing of it remains, except the ruins. This accounts for the inhabitants of the Deccan being so well acquainted with the history of Chandragupta. The authors of the Mudra- Rakshasa, and its commentary, were natives of that country.

In the mean time, Seleucus, ill brooking the loss of his possessions in India, resolved to wage war, in order to recover them, and accordingly entered India at the head of an army; but finding Chandragupta ready to receive him, and being at the same time uneasy at the increasing power of Antigonus and his son, he made peace with the emperor of India, relinquished his conquests, and renounced every claim to them. Chandragupta made him a present of 50 elephants; and, in order to cement their friendship more strongly, an alliance by marriage took place between them, according to Strabo, who does not say in what manner it was effected. It is not likely, however, that Seleucus should marry an Indian princess; besides, Chandragupta, who was very young when he visited Alexander's camp, could have no marriageable daughter at that time. It is more probable, that Seleucus gave him his natural daughter, born in Persia. From that time, I suppose, Chandragupta had constantly a large body of Grecian troops in his service, as mentioned in the Mudra-Racshasa.

It appears, that this affinity between Seleucus and Chandragupta took place in the year 302 B.C. at least the treaty of peace was concluded in that year. Chandragupta reigned four-and-twenty years; and of course died 292 years before our era.

-- Essay III. Of the Kings of Magadha; their Chronology, by Captain Wilford, Asiatic Researches, Volume 9, 1809. pgs. 94-100.

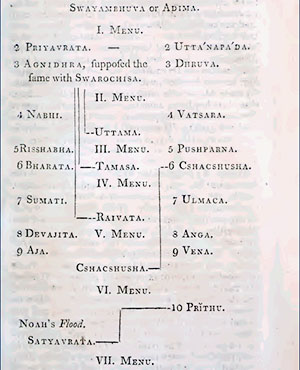

The accompanying genealogical table is faithfully extracted from the Vishnu purana, the Bhagavat, and other puranas, without the least alteration whatever. I have collected numerous MSS. and with the assistance of some learned Pundits of Benares, who are fully satisfied of the authenticity of this table, I exhibit it as the only genuine chronological record of Indian history that has hitherto come to my knowledge. It gives the utmost extent of the chronology of the Hindus; and as a certain number of years only can be allowed to a generation, it overthrows at once their monstrous system, which I have rejected as absolutely repugnant to the course of nature, and human reason.

Indeed their systems of geography, chronology, and history, are all equally monstrous and absurd. The circumference of the earth is said to be 500,000,000 yojanas, or 2,456,000,000 British miles: the mountains are asserted to be 100 yojanas, or 491 British miles high. Hence the mountains to the south of Benares are said, in the puranas, to have kept the holy city in total darkness, till Matra-deva, growing angry at their insolence, they humbled themselves to the ground, and their highest peak now is not more than 500 feet high. In Europe similar notions once prevailed; for we are told that the Cimmerians were kept in continual darkness by the interposition of immensely high mountains. In the Calica purana, it is said that the mountains have sunk considerably, so that the highest is not above one yojana, or five miles high.

When the Puranas speak of the kings of ancient times, they are equally extravagant. According to them, King Yudhishthir reigned seven and twenty thousand years; king Nanda, of whom I shall speak more fully hereafter, is said to have possessed in his treasury above 1,584,000,000 pounds sterling, in gold coin alone: the value of the silver and copper coin, and jewels, exceeded all calculation; and his army consisted of 100,000,000 men. These accounts, geographical, chronological, and historical, as absurd and inconsistent with reason, must be rejected. This monstrous system seems to derive its origin from the ancient period of 12,000 natural years, which was admitted by the Persians, the Etruscans, and, I believe, also by the Celtic tribes; for we read of a learned nation in Spain, which boasted of having written histories of above six thousand years.

The hindus still make use of a period of 12,000 divine years, after which a periodical renovation of the world takes place. It is difficult to fix the time when the Hindus, forsaking the paths of historical truth, launched into the mazes of extravagance and fable. Megasthenes, who had repeatedly visited the court of Chandra Gupta [No, Sandrocottus], and of course had an opportunity of conversing with the best informed persons in India, is silent as to this monstrous system of the Hindus: on the contrary, it appears, from what he says, that in his time they did not carry back their antiquities much beyond six thousand, or even five thousand years, as we read in some MSS. He adds also, according to Clemens of Alexandria, that the Hindus and the Jews were the only people, who had a true idea of the creation of the world, and the beginning of things.

Fragm. XLII.

Clem. Alex. Strom. I. p. 305 D (ed. Colon. 1688).

That the Jewish race is by far the oldest of all these, and that their philosophy, which has been committed to writing, preceded the philosophy of the Greeks, Philo the Pythagorean shows by many arguments, as does also Aristoboulos the Peripatetic, and many others whose names I need not waste time in enumerating. Megasthenes, the author of a work on India, who lived with Seleukos Nikator, writes most clearly on this point, and his words are these: — "All that has been said regarding nature by the ancients is asserted also by philosophers out of Greece, on the one part in India by the Brachmanes, and on the other in Syria by the people called the Jews."

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle, M.A., Principal of the Government College, Patna, Member of the General Council of the University of Edinburgh, Fellow of the University of Calcutta, With Introduction, Notes and Map of Ancient India, Reprinted (with additions) from the "Indian Antiquary," 1876-77, 1877

There was then an obvious affinity between the chronological system of the Jews and the Hindus. We are well acquainted with the pretensions of the Egyptians and Chaldeans to antiquity. This they never attempted to conceal. It is natural to suppose, that the Hindus were equally vain: they are so now; and there is hardly a Hindu who is not persuaded of, and who will not reason upon, the supposed antiquity of his nation. Megasthenes, who was acquainted with the antiquities of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Jews, whilst in India, made inquiries into the history of the Hindus, and their antiquity: and it is natural to suppose that they would boast of it as well as the Egyptians or Chaldeans, and as much then as they do now. Surely they did not invent fables to conceal them from the multitude, for whom, on the contrary, these fables were framed.

At all events, long before the ninth century the chronological system of the Hindus was as complete, or rather, perfectly the same as it is now; for Albumazar, who was contemporary with the famous Almamun, and lived at his court at Balac or Balkh, had made the Hindu antiquities his particular study. He was also a famous astronomer and astrologer, and had made enquiries respecting the conjunctions of the planets, the time of the creation of the world, and its duration, for astrological purposes; and he says, that the Hindus reckoned from the Flood to the Hejira [Muhammad's departure from Mecca to Medina in AD 622.] 720,634,442,715 days, or 3725 years.* [See Bailly's Astron. Anc. p. 30. and Mr. Davis's Essay in the second volume of the Asiatick Researches, p. 274.]

Here is a mistake, which probably originates with the transcriber or translator, but it may be easily rectified. The first number, though somewhat corrupted, is obviously meant for the number of days from the creation to the Hejira; and the 3725 years are reckoned from the beginning of the Cali-yug to the Hejira. It was then the opinion of Albumazar, about the middle of the ninth century, that the aera of the Cali-yug coincided with that of the Flood. He had, perhaps, data which no longer exist, as well as Abul-Fazil in the time of Akbar. Indeed, I am sometimes tempted to believe, from some particular passages in the Puranas, which are related in the true historical style, that the Hindus have destroyed, or at least designedly consigned to oblivion, all genuine records, as militating against their favourite system. In this manner the Romans destroyed the books of Numa, and consigned to oblivion the historical books of the Etrurians, and I suspect also those of the Turdktani in Spain.

Albumazar, also spelled Albumasar, orAbū Maʿshar, (born Aug. 10, 787, Balkh, Khorāsān [now in Afghanistan]—died March 9, 886, al-Wāsit, Iraq), leading astrologer of the Muslim world, who is known primarily for his theory that the world, created when the seven planets were in conjunction in the first degree of Aries, will come to an end at a like conjunction in the last degree of Pisces.

Albumazar’s reputation as an astrologer was immense, both among his contemporaries and in later times. He was the archetype of the knavish astrologer in the play Lo astrologo (1606) by the Italian philosopher and scientist Giambattista della Porta. This play was the basis for Albumazar by Thomas Tomkis [No, John Tomkis], which was revived by the English poet John Dryden in 1668. Albumazar’s principal works include Kitāb al-Madkhal al-Kabīr ʿalā ʿilm aḥkām al-nujūm (“Great Introduction to the Science of Astrology”), Kitāb al-qirānāt (“Book of Conjunctions”), and Kitāb taḥāwīl sinī al-ʿālam (“Book of Revolutions of the World-Years”).

-- Albumazar, by Britannica

ALBUMAZAR.

Alb. Come, brave mercurials, sublim'd in cheating;

My dear companions, fellow-soldiers

I' th' watchful exercise of thievery:

Shame not at your so large profession,

No more than I at deep astrology;

For in the days of old, Good morrow, thief,

As welcome was received, as now your worship.

The Spartans held it lawful, and the Arabians;

So grew Arabia felix, Sparta valiant...

Your patron, Mercury, in his mysterious character

Holds all the marks of the other wanderers,

And with his subtle influence works in all,

Filling their stories full of robberies.

Most trades and callings must participate

Of yours, though smoothly gilt with th' honest title

Of merchant, lawyer, or such like—the learned

Only excepted, and he's therefore poor.

Har. And yet he steals, one author from another.

This poet is that poet's plagiary.

And he a third's, till they end all in Homer.

Alb. And Homer filch'd all from an Egyptian priestess,

The world's a theatre of theft. Great rivers

Rob smaller brooks, and them the ocean;

And in this world of ours, this microcosm,

Guts from the stomach steal, and what they spare,

The meseraics filch, and lay't i' the liver:

Where, lest it should be found, turn'd to red nectar,

'Tis by a thousand thievish veins convey'd,

And hid in flesh, nerves, bones, muscles, and sinews:

In tendons, skin, and hair; so that, the property

Thus alter'd, the theft can never be discover'd.

Now all these pilf'ries, couch'd and compos'd in order,

Frame thee and me. Man's a quick mass of thievery.

Ron. Most philosophical Albumazar!

Har. I thought these parts had lent and borrowed mutual.

Alb. Say, they do so: 'tis done with full intention

Ne'er to restore, and that's flat robbery.

Therefore go on: follow your virtuous laws,

Your cardinal virtue, great necessity;

Wait on her close with all occasions;

Be watchful, have as many eyes as heaven,

And ears as harvest: be resolv'd and impudent:

Believe none, trust none; for in this city

(As in a fought field, crows and carcases)

No dwellers are but cheaters and cheatees.

Ron. If all the houses in the town were prisons,

The chambers cages, all the settles stocks,

The broad-gates, gallowses, and the whole people

Justices, juries, constables, keepers, and hangmen,

I'd practise, spite of all; and leave behind me

A fruitful seminary of our profession,

And call them by the name of Albumazarians...

Alb. Why, bravely spoken:

Fitting such generous spirits! I'll make way

To your great virtue with a deep resemblance

Of high astrology. Harpax and Ronca,

List to our project: I have new-lodg'd a prey

Hard by, that (taken) is, so fat and rich,

'Twill make us leave off trading, and fall to purchase...

'Tis a rich gentleman, as old as foolish;

The poor remnant of whose brain, that age had left him,

The doting love of a young girl hath dried:

And, which concerns us most, he gives firm credit

To necromancy and astrology...

Pandolfo is the man...

Then Furbo sings this song.

Bear up thy learned brow, Albumazar;

Live long, of all the world admir'd,

For art profound and skill retir'd,

To cheating by the height of star:

Hence, gipsies, hence; hence, rogues of baser strain,

That hazard life for little gain:

Stand off and, wonder, gape and gaze afar

At the rare skill of great Albumazar...

Ron. Sir, you must know my master's heavenly brain,

Pregnant with mysteries of metaphysics,

Grows to an embryo of rare contemplation

Which, at full time brought forth, excels by far

The armed fruit of Vulcan's midwif'ry,

That leap'd from Jupiter's mighty cranium...

With a wind-instrument my master made,

In five days you may breathe ten languages,

As perfect as the devil or himself...

The great Albumazar, by wondrous art,

In imitation of this perspicil,

Hath fram'd an instrument that magnifies

Objects of hearing, as this doth of seeing;

That you may know each whisper from Prester John

Against the wind, as fresh as 'twere delivered

Through a trunk or Gloucester's list'ning wall...

Ron. Sir, this is called an autocousticon.

Pan. Autocousticon!

Why, 'tis a pair of ass's ears, and large ones.

Ron. True; for in such a form the great Albumazar

Hath fram'd it purposely, as fitt'st receivers

Of sounds, as spectacles like eyes for sight....

Cri. What 'strologer?

Pan. The learned man I told thee,

The high Almanac of Germany; an Indian

Far beyond Trebisond and Tripoli,

Close by the world's end: a rare conjuror

And great astrologer. His name, pray, sir?

Ron. Albumazarro Meteoroscopico.

Cri. A name of force to hang him without trial.

Pan. As he excels in science, so in title.

He tells of lost plate, horses, and stray'd cattle

Directly, as he had stol'n them all himself.

Cri. Or he or some of his confederates....

Alb. Ronca, the bunch of planets new found out,

Hanging at the end of my best perspicil,

Send them to Galileo at Padua:

Let him bestow them where he please. But the stars,

Lately discover'd 'twixt the horns of Aries,

Are as a present for Pandolfo's marriage,

And hence styl'd Sidera Pandolfaea....

My almanac, made for the meridian

And height of Japan, give't th' East India Company;

There may they smell the price of cloves and pepper,

Monkeys and china dishes, five years ensuing.

And know the success of the voyage of Magores;

For, in the volume of the firmament,

We children of the stars read things to come,

As clearly as poor mortals stories pass'd

In Speed or Holinshed. The perpetual motion

With a true 'larum in't, to run twelve hours

'Fore Mahomet's return, deliver it safe

To a Turkey factor: bid him with care present it

From me to the house of Ottoman...

Pan. Why stare you?

Are you not well?

Alb. I wander 'twixt the poles

And heavenly hinges, 'mongst excentricals,

Centres, concentrics, circles, and epicycles,

To hunt out an aspect fit for your business....

Now, then, declining from Theourgia,

Artenosaria Pharmacia rejecting

Necro-puro-geo-hydro-cheiro-coscinomancy,

With other vain and superstitious sciences,

We'll anchor at the art prestigiatory,

That represents one figure for another,

With smooth deceit abusing th' eyes of mortals....

And, since the moon's the only planet changing,

For from the Neomenia in seven days

To the Dicotima, in seven more to the Panselinum,

And in as much from Plenilunium

Thorough Dicotima to Neomenia,

'Tis she must help us in this operation...

Why, here's a noble prize, worth vent'ring for.

Is not this braver than sneak all night in danger,

Picking of locks, or hooking clothes at windows?

Here's plate, and gold, and cloth, and meat, and wine,

All rich and eas'ly got....

Trin. Give me a looking-glass

To read your skill in these new lineaments.

Alb. I'd rather give you poison; for a glass,

By secret power of cross reflections

And optic virtue, spoils the wond'rous work

Of transformation; and in a moment turns you,

Spite of my skill, to Trincalo as before.

We read that Apuleius was by a rose

Chang'd from an ass to man: so by a mirror

You'll lose this noble lustre, and turn ass.

I humbly take my leave; but still remember

T' avoid the devil and a looking-glass.

Newborn Antonio, I kiss your hands....

How? not a single share of this great prize,

That have deserv'd the whole? was't not my plot

And pains, and you mere instruments and porters?

Shall I have nothing?

Ron. No, not a silver spoon.

Fur. Nor cover of a trencher-salt.

Har. Nor table-napkin.

Alb. Friends, we have kept an honest truth and faith

Long time amongst us: break not the sacred league,

By raising civil theft: turn not your fury

'Gainst your own bowels. Rob your careful master!

Are you not asham'd?

Ron. 'Tis our profession,

As yours astrology. "And in the days of old,

Good morrow, thief, as welcome was receiv'd,

As now Your worship." 'Tis your own instruction.

Fur. "The Spartans held it lawful, and th' Arabians,

So grew Arabia happy, Sparta valiant."

Har. "The world's a theatre of theft: great rivers

Rob smaller brooks; and them the ocean."

Alb. Have not I wean'd you up from petty larceny,

Dangerous and poor, and nurs'd you to full strength

Of safe and gainful theft? by rules of art

And principles of cheating made you as free

From taking as you went invisible;

And do ye thus requite me? this the reward

For all my watchful care?

Ron. We are your scholars,

Made by your help and our own aptness able

To instruct others. 'Tis the trade we live by.

You that are servant to divine astrology,

Do something worth her livery: cast figures,

Make almanacs for all meridians.

Fur. Sell perspicils and instruments of hearing:

Turn clowns to gentlemen; buzzards to falcons,

'ur-dogs to greyhounds; kitchen-maids to ladies.

Har. Discover more new stars and unknown planets:

Vent them by dozens, style them by the names

Of men that buy such ware. Take lawful courses,

Rather than beg.

Alb. Not keep your honest promise?

Ron. "Believe none, credit none: for in this city

No dwellers are but cheaters and cheatees."

Alb. You promis'd me the greatest share.

Ron. Our promise!

If honest men by obligations

And instruments of law are hardly constrain'd

T' observe their word, can we, that make profession

Of lawless courses, do't?

Alb. Amongst ourselves!

Falcons, that tyrannise o'er weaker fowl,

Hold peace with their own feathers.

Har. But when they counter

Upon one quarry, break that league, as we do.

Alb. At least restore the ten pound in gold I lent you.

Ron. "'Twas lent in an ill second, worser third,

And luckless fourth:" 'tis lost, Albumazar.

Fur. Saturn was in ascension, Mercury

Was then combust, when you delivered it.

'Twill never be restor'd.

Ron. "Hali, Abenezra,

Hiarcha, Brachman, Budda Babylonicus,"

And all the Chaldees and the Cabalists,

Affirm that sad aspect threats loss of debts.

Har. Frame by your azimuth Almicantarath,

An engine like a mace, whose quality

Of strange retractive virtue may recall

Desperate debts, and with that undo serjeants.

Alb. Was ever man thus baited by's own whelps?

Give me a slender portion, for a stock

To begin trade again.

Ron. 'Tis an ill course,

And full of fears. This treasure hath enrich'd us,

And given us means to purchase and live quiet

Of th' fruit of dangers past. When I us'd robbing,

All blocks before me look'd like constables,

And posts appear'd in shape of gallowses;

Therefore, good tutor, take your pupil's counsel:

'Tis better beg than steal; live in poor clothes

Than hang in satin.

Alb. Villains, I'll be reveng'd,

And reveal all the business to a justice!

Ron. Do, if thou long'st to see thy own anatomy.

Alb. This treachery persuades me to turn honest.

Fur. Search your nativity; see if the Fortunates

And Luminaries be in a good aspect,

And thank us for thy life. Had we done well,

We had cut thy throat ere this.

Alb. Albumazar,

Trust not these rogues: hence, and revenge.

-- Albumazar, by John Tomkis

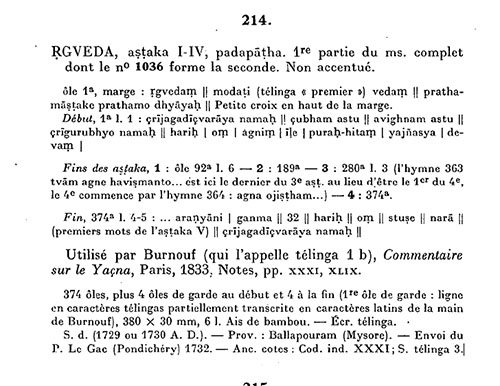

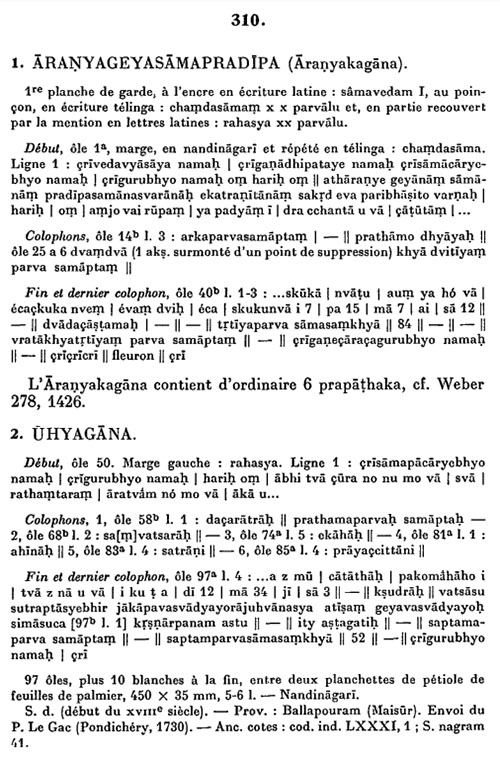

The Puranas are certainly a modern compilation from valuable materials, which I am afraid no longer exist: an astronomical observation of the heliacal rising of Canopus, mentioned in two of the Puranas, puts this beyond doubt. It is declared there, that certain religious rites are to be performed on the 27th of Bhadra, when Canopus, disengaged from the rays of the sun, becomes visible. It rises now on the 18th of the same months. The 18th and 27th of Bhadra answer this year to the 29th of August and 7th of September. I had not leisure enough to consult the two Puranas above mentioned on this subject. But as violent disputes have obtained among the learned Pandits, some insisting that these religious rites ought to be performed on the 27th of Bhadra, as directed in the Puranas, whilst others insist, it should be at the time of the udaya, or appearance of Canopus; a great deal of paper has been wasted on this subject, and from what has been written upon it, I have extracted the above observations. As I am not much used to astronomical calculations, I leave to others better qualified than I am to ascertain from these data the time in which the Puranas were written.

Newly discovered Puranas manuscripts from the medieval centuries has attracted scholarly attention and the conclusion that the Puranic literature has gone through slow redaction and text corruption over time, as well as sudden deletion of numerous chapters and its replacement with new content to an extent that the currently circulating Puranas are entirely different from those that existed before 11th century, or 16th century.

For example, a newly discovered palm-leaf manuscript of Skanda Purana in Nepal has been dated to be from 810 CE, but is entirely different from versions of Skanda Purana that have been circulating in South Asia since the colonial era. Further discoveries of four more manuscripts, each different, suggest that document has gone through major redactions twice, first likely before the 12th century, and the second very large change sometime in the 15th-16th century for unknown reasons. The different versions of manuscripts of Skanda Purana suggest that "minor" redactions, interpolations and corruption of the ideas in the text over time.

Rocher states that the date of the composition of each Purana remains a contested issue. Dimmitt and van Buitenen state that each of the Puranas manuscripts is encyclopedic in style, and it is difficult to ascertain when, where, why and by whom these were written.

Many of the extant manuscripts were written on palm leaf or copied during the British India colonial era, some in the 19th century. The scholarship on various Puranas, has suffered from frequent forgeries, states Ludo Rocher, where liberties in the transmission of Puranas were normal and those who copied older manuscripts replaced words or added new content to fit the theory that the colonial scholars were keen on publishing.

-- Puranas, by Wikipedia