by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/8/22

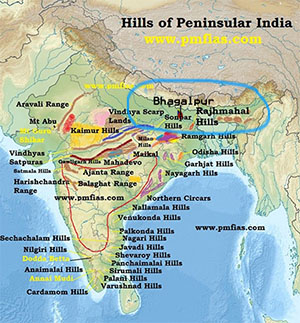

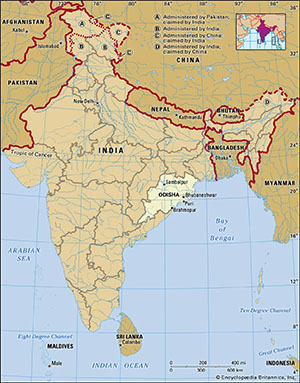

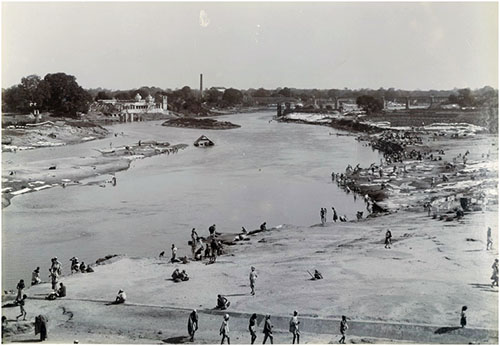

The Prinas and the Cainas (a tributary of the Ganges) are both navigable rivers. The tribes which dwell by the Ganges are the Calingae, nearest the sea, and higher up the Mandei, also the Malli, among whom is Mount Mallus, the boundary of all that region being the Ganges. Some have asserted that this river, like the Nile, rises from unknown sources, and in a similar way waters the country it flows through, while others trace its source to the Skythian mountains. Nineteen rivers are said to flow into it, of which, besides those already mentioned, the Condochates, Erannoboas, Cosoagus, and Sonus are navigable....

It is farther said that the Indians do not rear monuments to the dead, but consider the virtues which men have displayed in life, and the songs in which their praises are celebrated, sufficient to preserve their memory after death. But of their cities it is said that the number is so great that it cannot be stated with precision, but that such cities as are situated on the banks of rivers or on the sea-coast are built of wood instead of brick, being meant to last only for a time,— so destructive are the heavy rains which pour down, and the rivers also when they overflow their banks and inundate the plains, — while those cities which stand on commanding situations and lofty eminences are built of brick and mud; that the greatest city in India is that which is called Palimbothra, in the dominions of the Prasians, where the streams of the Erannoboas and the Ganges unite, — the Ganges being the greatest of all rivers, and the Erannoboas being perhaps the third largest of Indian rivers, though greater than the greatest rivers elsewhere; but it is smaller than the Ganges where it falls into it. Megasthenes informs us that this city stretched in the inhabited quarters to an extreme length on each side of eighty stadia, and that its breadth was fifteen stadia, and that a ditch encompassed it all round, which was six hundred feet in breadth and thirty cubits in depth, and that the wall was crowned with 570 towers and had four-and-sixty gates.

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle, M.A., 1877

The next is the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], or red river: in the Puranas it is constantly called Sona, and I believe never otherwise. In the Amara cosa, and other tracts, I am told, it is called Hiranya-bahu, implying the golden arm, or branch of a river, or the golden canal or channel. These expressions imply an arm or branch of the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], which really forms two branches before it falls into the Ganges. The easternmost, through the accumulation of sand, is now nearly filled up, and probably will soon disappear.

The epithet of golden does by no means imply that gold was found in its sands. It was so called, probably, on account of the influx of gold and wealth arising from the extensive trade carried on through it; for it was certainly a place of shelter for all the large trading boats during the stormy weather and the rainy season.

In the extracts from Megasthenes by Pliny and Arrian, the Sonus and Erannoboas appear either as two distinct rivers, or as two arms of the same river. Be this as it may, Arrian says that the Erannoboas was the third river in India, which is not true. But I suppose that Megasthenes meant only the Gangetick provinces: for he says that the Ganges was the first and largest. He mentions next the Commenasis or Sarayu, from the country of Commanh, as a very large river. The third large river is then the Erannoboas or river Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki].

Ptolemy, finding himself peculiarly embarrassed with regard to this river, and the metropolis of India situated on its banks, thought proper to suppress it entirely. Others have done the same under similar distressful circumstances. It is however well known to this day under the denomination of Hiranya-baha, even to every school boy in the Gangetick provinces, and in them there is no other river of that name....[???!!!]

The Damiadee was first noticed by the Sansons in France, but was omitted since by every geographer, I believe, such as the Sieur Robert, the famous D’Anville, &c; but it was revived by Major Rennell, under the name of Dummody. I think its real name was Dhumyati, from a thin mist like smoke, arising from its bed. Several rivers in India are so named: thus the Hiranya-baha, or eastern branch of the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], is called Cujjhati, or Cuhi† [Commentary on the Geog. of the M. Bh.] from Cuha, a mist hovering occasionally over its bed. As this branch of the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki] has disappeared, or nearly so, this fog is no longer to be seen.

-- VII. On the ancient Geography of India, by Lieut. Col. F. Wilford

I cannot help mentioning a discovery which accident threw in my way, though my proofs must be reserved for an essay which I have destined for the fourth volume of your Transactions. To fix the situation of that Palibothra (for there may have been several of the name) which was visited and described by Megasthenes, had always appeared a very difficult problem, for though it could not have been Prayaga, where no ancient metropolis ever stood, nor Canyacubja, which has no epithet at all resembling the word used by the Greeks; nor Gaur, otherwise called Lacshmanavati, which all know to be a town comparatively modern, yet we could not confidently decide that it was Pataliputra, though names and most circumstances nearly correspond, because that renowned capital extended from the confluence of the Sone and the Ganges to the site of Patna, while Palibothra stood at the junction of the Ganges and Erannoboas, which the accurate M. D'Anville had pronounced to be the Yamuna; but this only difficulty was removed, when I found in a classical Sanscrit book, near 2000 years old, that Hiranyabahu, or golden armed, which the Greeks changed into Erannoboas, or the river with a lovely murmur, was in fact another name for the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki] itself; though Megasthenes, from ignorance or inattention, has named them separately. This discovery led to another of greater moment, for Chandragupta, who, from a military adventurer, became like Sandracottus the sovereign of Upper Hindustan, actually fixed the seat of his empire at Pataliputra, where he received ambassadors from foreign princes; and was no other than that very Sandracottus who concluded a treaty with Seleucus Nicator...

-- Discourse X. Delivered February 28, 1793, P. 192, Excerpt from "Discourses Delivered Before the Asiatic Society: And Miscellaneous Papers, on The Religion, Poetry, Literature, Etc. of the Nations of India", by Sir William Jones, As. Res. vol. iv. p. 11, 1799

The City of Pataliputra: Its Location and Boundaries.

The geographical position of the city is fixed, by the foregoing data, at a point somewhere in the immediate vicinity of the modern town of Patna. The old city stood on the south bank of the Ganges at the confluence of the latter river with another, called by the Greeks "Erannoboas," a name apparently intended for the river Hiranyabahu or Son,1 [Strabo does not name this river, but Arrian, writing apparently from the same sources (Megasthenes), calls it "Erranoboas," which is usually considered to be intended for the Indian "Hiranya-baha" or "The Golden Armed," a title which Sir W. Jones showed (Asiatic Researches, IV, 10 (1795)) was an ancient name of the river Son, and Colonel Wilford (idem, XIV, 380) quotes Patanjali as writing "Pataliputra on the Son" (anu Sonam Pataliputra) also Ind. Antiquary, 1872, p. 201). But Arrian and Pliny enumerate both the "Erranoboas" and "Son" as distinct rivers. It might also be intended for the Hiranyavati or The "Golden One," which was a title of the Gandak or one of its branches at the time and place where Buddha died; and the Gandak joins the Ganges opposite Patna at the present day.] which formerly joined the Ganges here, and in the accompanying map I have indicated in green the present traces of the old channel of the Son, which seems to be the river in question.

-- Report on the Excavations At Pataliputra (Patna): The Palibothra of the Greeks, by L.A. Waddell, M.B., LL.D., Lieut.-Colonel, Indian Medical Service, 1903

This article has multiple issues. This article needs additional citations for verification. Some of this article's listed sources may not be reliable.

The Amarakosha (Devanagari: अमरकोशः, IAST: Amarakośaḥ , ISO: Amarakōśaḥ) is the popular name for Namalinganushasanam (Devanagari: नामलिङ्गानुशासनम्, IAST: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsanam, ISO: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsanam) a thesaurus in Sanskrit written by the ancient Indian scholar Amarasimha. It may be one of the oldest extant koshas. The author himself mentions 18 prior works, but they have all been lost.

Amarasimha (c. CE 375) was a Sanskrit grammarian and poet from ancient India, of whose personal history hardly anything is known. He is said to have been "one of the nine gems that adorned the throne of Vikramaditya," and according to the evidence of Xuanzang, this is the Chandragupta Vikramaditya (Chandragupta II) who flourished about CE 375. Other sources describe him as belonging to the period of Vikramaditya of 7th century. Most of Amarasiṃha's works were lost, with the exception of the celebrated Amara-Kosha (IAST: Amarakośa) (Treasury of Amara). The first reliable mention of the Amarakosha is in the Amoghavritti of Shakatayana composed during the reign of Amoghavarsha (814-867CE)

The Amarakosha is a lexicon of Sanskrit words in three books, and hence is sometimes called the Trikāṇḍī or the "Tripartite". It is also known as "Namalinganushasana". The Amarakosha contains 10,000 words, and is arranged, like other works of its class, in metre, to aid the memory.

The first chapter of the Kosha was printed at Rome in Tamil character in 1798. An edition of the entire work, with English notes and an index by HT Colebrooke appeared at Serampore in 1808. The Sanskrit text was printed at Calcutta in 1831. A French translation by ALA Loiseleur-Deslongchamps was published at Paris in 1839. B. L. Rice compiled the text in Kannada script with meanings in English and Kannada in 1927.

-- Amarasimha, by Wikipedia

Its form of presentation is of the strangest: a miracle of ingenuity, but of perverse and wasted ingenuity. The only object aimed at in it is brevity, at the sacrifice of everything else — of order, of clearness, of even intelligibility except by the aid of keys and commentaries and lists of words, which then are furnished in profusion. To determine a grammatical point out of it is something like constructing a passage of text out of an index verborum [An index of words.]: if you are sure that you have gathered up every word that belongs in the passage, and have put them all in the right order, you have got the right reading; but only then. If you have mastered Panini sufficiently to bring to bear upon the given point every rule that relates to it, and in due succession, you have settled the case; but that is no easy task. For example, it takes nine mutually limitative rules, from all parts of the text-book, to determine whether a certain aorist shall be ajgarisam or ajagarisam (the case is reported in the preface to Muller's grammar): there is lacking only a tenth rule, to tell us that the whole word is a false and never-used formation....

The main thing which makes of the grammarians' Sanskrit a special and peculiar language is its list of roots. Of these there are reported to us about two thousand, with no intimation of any difference in character among them, or warning that a part of them may and that another part may not be drawn upon for forms to be actually used; all stand upon the same plane. But more than half — actually more than half — of them never have been met with, and never will be met with, in the Sanskrit literature of any age. When this fact began to come to light, it was long fondly hoped, or believed, that the missing elements would yet turn up in some corner of the literature not hitherto ransacked; but all expectation of that has now been abandoned. One or another does appear from time to time; but what are they among so many? The last notable case was that of the root stigh, discovered in the Maitrayani-Sanhita, a text of the Brahmana period; but the new roots found in such texts are apt to turn out wanting in the lists of the grammarians. Beyond all question, a certain number of cases are to be allowed for, of real roots, proved such by the occurrence of their evident cognates in other related languages, and chancing not to appear in the known literature; but they can go only a very small way indeed toward accounting for the eleven hundred unauthenticated roots. Others may have been assumed as underlying certain derivatives or bodies of derivatives — within due limits, a perfectly legitimate proceeding; but the cases thus explainable do not prove to be numerous. There remain then the great mass, whose presence in the lists no ingenuity has yet proved sufficient to account for. And in no small part, they bear their falsity and artificiality on the surface, in their phonetic form and in the meanings ascribed to them; we can confidently say that the Sanskrit language, known to us through a long period of development, neither had nor could have any such roots. How the grammarians came to concoct their list, rejected in practice by themselves and their own pupils, is hitherto an unexplained mystery. No special student of the native grammar, to my knowledge, has attempted to cast any light upon it; and it was left for Dr. Edgren, no partisan of the grammarians, to group and set forth the facts for the first time, in the Journal of the American Oriental Society (Vol. XI, 1882 [but the article printed in 1879], pp. 1-55), adding a list of the real roots, with brief particulars as to their occurrence.1 [I have myself now in press a much fuller account of the quotable roots of the language, with all their quotable tense-stems and primary derivatives — everything accompanied by a definition of the period of its known occurrence in the history of the language.] It is quite clear, with reference to this fundamental and most important item, of what character the grammarians' Sanskrit is.

-- The Study of Hindu Grammar and the Study of Sanskrit, by William Dwight Whitney

There have been more than 40 commentaries on the Amarakosha.

Etymology

The word "Amarakosha" derives from the Sanskrit words amara ("immortal") and kosha ("treasure, casket, pail, collection, dictionary"). The actual name of the book "Namalinganushasanam" means "instruction concerning nouns and gender".[citation needed]

Author

Main article: Amara Sinha

Narasimha [Amarasimha] is said to have been one of the Navaratnas ("nine gems") at the court of Vikramaditya, the legendary king inspired by Chandragupta II, a Gupta king who reigned around AD 400.

Navaratnas (transl. Nine gems) or Nauratan was a term applied to a group of nine extraordinary people in an emperor's court in India. The well-known Nauratnas include the ones in the courts of the Hindu emperor Vikramaditya, the Mughal emperor Akbar, and the feudal lord Raja Krishnachandra.

Vikramaditya was a legendary emperor, who ruled from Ujjain; he is generally identified with the Gupta emperor Chandragupta II. According to folk tradition, his court had 9 famous scholars.

The earliest source that mentions this legend is Jyotirvidabharana (22.10), a treatise attributed to Kalidasa. According to this text, the following 9 scholars (including Kalidasa himself) attended Vikramaditya's court:

1. Amarasimha

2. Dhanvantari

3. Ghatkharpar

4. Kalidasa

5. Kshapanaka

6. Shanku

7. Varahamihira

8. Vararuchi

9. Vetala-Bhatta

However, Jyotirvidabharana is considered a literary forgery of a date later than Kalidasa by multiple scholars. V. V. Mirashi dates the work to 12th century, and points out that it could not have been composed by Kalidasa, because it contains grammatical faults. There is no mention of such "Navaratnas" in earlier literature. D. C. Sircar calls this tradition "absolutely worthless for historical purposes".

There is no historical evidence to show that these nine scholars were contemporary figures or proteges of the same king. Vararuchi is believed to have lived around 3rd or 4th century CE. The period of Kalidasa is debated, but most historians place him around 5th century CE. Varahamihira is known to have lived in 6th century CE. Dhanavantari was the author of a medical glossary (Nighantu); his period is uncertain. Amarasimha cannot be dated with certainty either, but his lexicon utilizes the works of Dhanavantari and Kalidasa; therefore, he cannot be dated to 1st century BCE, when the legendary Vikramaditya is said to have established the Vikrama Samvat in 57 BCE. Not much is known about Shanku, Vetalabhatta, Kshapanaka and Ghatakarpara. Some Jain writers identify Siddhasena Divakara as Kshapanaka, but this claim is not accepted by historians.

-- Navaratnas, by Wikipedia

Some sources indicate that he belonged to the period of Vikramaditya of the 7th century.[1]

Mirashi examines the question of the date of composition of Amarakosha. He finds the first reliable mention in Amoghavritti of Shakatayana composed during the reign of Amoghavarsha (814-867 CE).[2]

Textual organisation

The Amarakośa consists of verses that can be easily memorized. It is divided into three kāṇḍas or chapters. The first, svargādi-kāṇḍa ("heaven and others") has words about heaven and the Gods and celestial beings who reside there. The second, bhūvargādi-kāṇḍa ("earth and others") deals with words about earth, towns, animals, and humans. The third, sāmānyādi-kāṇḍa ("common") has words related to grammar and other miscellaneous words.[citation needed]

Svargādikāṇḍa, the first kāṇḍa of the Amarakośa begins with the verse 'Svar-avyayaṃ-Svarga-Nāka-Tridiva-Tridaśālayāḥ' describing various names of Heaven viz. Svaḥ, Svarga, Nāka, Tridiva, Tridaśālaya, etc. The second verse 'Amarā Nirjarā DevāsTridaśā Vibudhāḥ Surāḥ’ describes various words that are used for the Deva-s (Gods). The fifth and sixth verses give various names of Buddha and Śākyamuni (i.e. Gautam Buddha). The following verses give the different names of Brahmā, Viṣṇu, Vasudeva, Balarāma, Kāmadeva, Lakṣmī, Kṛṣṇa, Śiva, Indra, etc. All these names are treated with great reverence. While Amarasiṃha is regarded to have been a Bauddha (Buddhist),[3][4] Amarakośa reflects the period before the rise of sectarianism. Commentaries on Amarakosha have been written by Brahmanical, Jain and well as Buddhist scholars.[5]

The second kāṇḍa, Bhuvargādikāṇḍa, of the Amarakosha is divided into ten Vargas or parts. The ten Vargas are Bhuvarga (Earth), Puravarga (Towns or Cities), Shailavarga (Mountains), Vanoshadivarga (Forests and medicines), Simhadivarga (Lions and other animals), Manushyavarga (Mankind), Bramhavarga (Brahmin), Kshatriyavarga (Kshatriyas), Vysyavarga (Vysyas) and Sudravarga (Sudras).[citation needed]

The Third Kanda, Sāmānyādikāṇḍa contains Adjectives, Verbs, words related to prayer, business, etc. The first verse Kshemankaroristatathi Shivathathi Shivamkara gives the Nanarthas of the word Shubakara or propitious as Kshemankara, Aristathathi, Shivathathi, and Shivamkara.[citation needed]

Commentaries

• Amarakoshodghātana by Kṣīrasvāmin (11th century CE, the earliest commentary)

• Tīkāsarvasvam by Vandhyaghatīya Sarvānanda (12th century)

• Rāmāsramī (Vyākhyāsudha) by Bhānuji Dīkshita

• Padachandrikā by Rāyamukuta

• Kāshikavivaranapanjikha by Jinendra Bhudhi

• Pārameśwari by Parameswaran Mōsad in Malayalam

• A Telugu commentary by Linga Bhatta (12th century)

Translations

"Gunaratha" of Ujjain translated it into Chinese in the 7th century.

The Pali thesaurus Abhidhānappadīpikā, composed in the twelfth century by the grammarian Moggallāna Thera, is based on the Amarakosha.

References

1. Amarakosha compiled by B.L.Rice, edited by N.Balasubramanya, 1970, page X

2. Literary and Historical Studies in Indology, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1975, p. 50-51

3. Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Devraj to Jyoti, Volume 2, Editor Amaresh Datta, Sahitya Akademi, 1988 p. 1036

4. A History of Indian Literature, Moriz Winternitz, Motilal Banarsidass, 1985, p. 494

5. Anundoram Barooah Makers of Indian literature, Biswanarayan Shastri, Sahitya Akademi, 1984p. 79

Bibliography

• Krsnaji Govinda Oka, Poona City, Law Printing Press, 1913

• Amarakosha at sanskritdocuments.org

• Amarakosha files by Avinash Sathaye

• The Nâmalingânusâsana (Amarakosha) of Amarasimha; with the commentary (Amarakoshodghâtana) of Kshîrasvâmin (1913) at the Internet Archive.

• A web interface to access the knowledge structure in Amarakosha at Department of Sanskrit Studies, University of Hyderabad.

*************************

Kosha or Dictionary of the Sanskrit Language by Umura Singha

With an English Interpretation and Annotations

by H. T. Colebrooke, Esq.

Late of the Bengal Civil Service

Third Edition

1891

PUBLISHER'S NOTICE

The value of Colebrooke's Umura Kosha has never been under-rated and is well known to all Anglo-Sanskrit Scholars. It is a book which appears to be indispensably necessary to the students of the Calcutta University and indeed to all English-knowing students of Sanskrit, as furnishing English synonyms for Sanskrit words and very valuable notes on the text. But as the book has long been out of print and is not now available except at a great cost, it is hoped that the publication of the present edition will bring it within the reach of the general public and the students of the Calcutta University in particular. The publisher sincerely hopes that the undertaking will meet the support of those for whom it is intended.

January, 1891

HARAGOBINDA RAKSHIT

PREFACE

THE compilation of a Sanskrit Dictionary having been undertaken early after the institution of the College of Fort William, it was at the same time thought advisable to print, in Sanskrit and English, the work which has been chosen for the basis of that compilation; as well for the sake of exhibiting an original authority to which reference will be frequently necessary, as with the view of furnishing an useful vocabulary which might serve until an ampler dictionary could be prepared and published.

The celebrated Umura Kosha, or Vocabulary of Sanskrit by Umura singha, is, by the unanimous suffrage of the learned, the best guide to the acceptations of nouns in Sanskrit. The work of Panini on etymology is rivalled by other grammars, some of which have even obtained the preference in the opinion of the learned of particular provinces: but Umura's vocabulary has prevailed wherever the Sanskrit language is cultivated; and the numerous other vocabularies, which remain, are consulted only where Umura's is either silent or defective. It has employed the industry of innumerable commentators, while none of the others (with the single exception of Hemachandra's have been interpreted even by one annotator. Such decided preference for the Umura Kosha, and the consequent frequency of quotations from it, determined the selection of this as the basis of an alphabetical dictionary, and suggested the expediency of also publishing the original text with an English interpretation. Like other vocabularies of Sanskrit, that of Umura is in metre; and a considerable degree of knowledge of the language becomes requisite to discriminate the words from their interpretations and to separate them from contiguous terms which affect their initials and finals. On this account, and to adapt the work to the use of the English student, the words, of which the sense is exhibited, are disjoined from their interpretation (which is included between crotchets); and the close of each word is marked by a Italic letter over it indicating the gender of the noun. Where a letter has been permuted according to the Sanskrit system of orthography, a dot is placed under the line to intimate that a letter is there altered or omitted: and a marginal note is added, exhibiting the radical final of the noun, or its initial, in every instance where either of them is so far disguised by permutation as not to be easily recognized upon a slight knowledge of the rudiments of the language, and of its orthography. An explanation in English is given in the margin, and completed when necessary, at the foot of the page. The different interpretations proposed by the several commentators, and the variations in orthography remarked by them, are also specified in the same place.

According to the original plan of the present publication, the variations in the reading of the text (for which a careful collation has been made of several copies and of numerous commentaries) are noticed only where they affect the interpretation of a word or its orthography. It was not at first intended to insert those differences which are remarked by commentators upon other authority, and not upon the ground of any variation in the text itself. However, the utility of indicating such differences was afterwards thought to counterbalance any inconvenience attending it: and after some progress had been made at the press, this* [These additions are incorporated with the text in the present edition.] and other additions to the original design were admitted, which have rendered a supplement necessary to supply omissions in the first chapters and complete the work upon an uniform plan.

To avoid too great an increase of the volume, the various readings and interpretations are rather hinted than fully set forth: it has been judged sufficient to state the result, as the notes would have been too much lengthened, if the ground of disagreement had been everywhere exhibited and explained. For the same reason, authorities have not been cited by name. The mention of the particular commentator in each instance would have enlarged the notes, with very little advantage, as the means of verifying authorities are as effectually furnished by an enumeration of the works which have been employed and consulted. They are as follow: —

I. The text of the Umura Kosha:

This vocabulary comprised in three books, is frequently cited under the title of Trikanda;* [ i e. The three books. But that name properly appertains to a more ancient vocabulary, which is mentioned by the commentaries on the Umura Kosha among the works from which this is supposed to have been compiled.] sometimes under the denomination of Abhidhana (nouns), from its subject; often under that of Umura Kosha, from the name of the author. The commentators are indeed unanimous in ascribing it to Umura Singha. He appears to have belonged to the sect of Buddha, (though this be denied by some of his scholiasts;) and is reputed to have lived in the reign of Vikramaditya; and he is expressly named among the ornaments of the Court of Raja Bhoja,† [In the Bhoja Prabandha.] one of the many princes to whom that title has been assigned. If this mention of him be accurate, he must have lived not more than eight hundred years ago; for a poem entitled Subahshita ratna sandoha, by a Jaina author named Amitakati, is dated in the year 1050 from the death of Vikramaditya, and in the reign of Munja who was uncle and predecessor of Raja Bhoja. It, however, appears inconsistent with the inscription at Buddhagaya which is dated in the year 1005 of the era of Vikramaditya, and in which mention is made of Umura Deva, probably the same with the author of the vocabulary. From the frequent instances of anachronism both in sacred and profane story as current among the Hindus, more confidence seems due to the inscription, than to any popular tales concerning Raja Bhoja; and the Umura Kosha may be considered as at least nine hundred years old; and possibly more ancient.

It is intimated in the author's own preface that the work was compiled from more ancient vocabularies: his commentators instance the Trikanda,* [See a preceding note.] Utpalini, Rabhasa and Katyayana as furnishing information on the nouns; and Vyadi and Vararuchi on the genders. The last mentioned of these authors is reputed contemporary with Vikramaditya and consequently with Umura Singha himself.

The copies of the original, which have been employed in the correction of the text, in the present publication, are,

1st. A transcript made for my use from an ancient corrected copy in the Tirhutiya character, and collated by me with a copy in Devanagari, which had been carefully examined by Sir William Jones. He had inserted in it an English interpretation; of which also I reserved a copy and have derived great assistance from it in the present publication.

2d. A transcript in Devanagari character, with a commentary and notes in the Kanara dialect. It contains numerous passages, which are unnoticed in the most approved commentaries, and which are accordingly omitted in the present edition.

3rd. Another copy in the Devanagari character, with a brief and imperfect interpretation in Hindi.

4th. A copy in the Bengali character with marginal notes explanatory of the text.

5th. A copy in duplicate, accompanied by a Sanskrit commentary, which will be forthwith mentioned (that of Ramasrama). It contains a few passages not noticed by most of the commentators. They have been, however, retained on the authority of this scholiast. A like remark is applicable to certain other passages expounded in some commentaries but not in others. All such have been retained, where the authority itself has been deemed good.

6th. Recourse has been occasionally had to other copies of the text in the possession of natives, whenever it has been thought any ways requisite.

II. Commentaries on the Umura Kosha.

1. At the head of the commentaries which have been used, must be placed that of Rayamukuta, (or Vrihaspati surnamed Rayamukutamani.) This work entitled Padachandrika, was compiled, as the author himself informs us, from sixteen earlier commentaries, to many of which he repeatedly refers: especially those of Kshira Swami, Subhuti, Hadda Chandra, Kalinga, Konkat a, Sarvadhara, and the Vyakhyamrita Tikasarvasva, &c.* [The following names may be selected from Mukuta's quotations, to complete the number of sixteen: Madhavi, Madhumadhavi, Sarvananda, Abhinanda, Rajadeva, Goverdhana, Dravida, Bh'ja Raja. But some of these appear to be separate works, rather than commentaries on the Umura Kosha. Mukuta occasionally cites the most celebrated grammarians as Panini, Jayaditya, Jinendra, Maitreya, Rakshita, Pubushottama, Madhava, &c.]

Its age is ascertained from the incidental mention of a date: viz. 1353 Saka, or 4532 of the Kaliyuga, corresponding to A.D. 1431.

Though the derivations in Mukuta's commentary be often inaccurate, and other errors also have been remarked by later compilers, its authority is in general great; and, accordingly, it has been carefully consulted under every article of the present work.

2. Among the earlier commentaries named by Raya Mukuta, that of Kshira Swami is the only one, which has been examined in the progress of this compilation. It is a work of considerable merit; and is still in general use in some provinces of India, although the interpretations not unfrequently differ from those commonly received.

3. The Vyakhyasudha, a modern commentary by Ramasrama or by Bhanudikshita (for copies differ as to the name of the author) is the work of a grammarian of the school of Benares. He continually refers to Rayamukuta and to Sami; and his work serves to confirm their scholia where accurate, and to correct them where erroneous. It has been consulted at every line.

4. The Vyakhya Pradipa by Achyuta Upadhyaya is a concise and accurate exposition of the text: but adds little to the information furnished by the works above-mentioned. It has been, however, occasionally consulted.

In these four commentaries, the derivations are given according to Panini's system. In others, which are next to be enumerated, various popular grammars are followed for the etymologies. But, as the derivations of the words are not included in the plan of the present work, being reserved for a place in the intended alphabetical dictionary of Sanskrit, those commentaries have not been the less useful in regard to the information which was sought in them.

5. The commentary of Bharata Malla (entitled Mugdhabodhini) has been as regularly consulted as those of Mukuta and Ramasrama. It is indeed a very excellent work; copious and clear, and particularly full upon the variations of orthography according to different readings or different authorities; the etymologies are given conformably with Vopadeva's system of grammar. The author flourished in the middle of last century.

6. The Sara Sundari by Mathuresa has been much used. It is perspicuous and abounds in quotations from other commentaries; and is therefore a copious source of information on the various interpretations and readings of the text. The Supadma is the grammar followed in the derivations stated by this commentator. Mathuresa is author likewise of a vocabulary in verse entitled Sabdaratnavali, arranged in the same order with the Umura Kosha, and which might serve therefore as a commentary on that work. It was compiled under the patronage of a Mussulman Chieftain Murehha Khan, whose name is prefixed to it. The author wrote not more than 150 years ago.* [His work contains the date 1588 Saka or A.D. 1666.]

7. The Padartha Kaumudi by Narayana Chakravarti is another commentary of considerable merit, which has been frequently consulted. The Kalapa is the grammar followed in the etymologies here exhibited.

8. A commentary by Ramanatha Vidyavachaspati entitled Trikandaviveca, is peculiarly copious on the variations of orthography, and is otherwise a work affording much useful information.

9. Another commentary which has been constantly employed, is that by Nilakantha. It is full and satisfactory on most points for which reference is usually made to the expositors of the Umura Kosha.

10. The commentary of Rama Tarkavagisa has been uniformly consulted throughout the work. It was recommended for its accuracy; but has furnished little information; being busied chiefly with etymology. This, like the preceding, follows the grammar entitled Kalapa.

Other commentaries were also collected for occasional reference in the progress of this work; but have not been employed, being found to contain no information which was not also furnished, and that more amply, by the scholiasts above mentioned. The list of them, contained in the subjoined note, may therefore suffice.* [Kaumudi by Nayanananda; Trikanda chintamani by Raghunatha Chakravarti; both according to Panini's system of etymology. Vatihamya kaumudi by Ramaprasada Tarkalankara; Padamanjari by Lokanatha; both following the grammatical system of the Kalapa. Pradipamanjari by Ramasrama, a jejune interpretation of the text. Vrihat Haravali by Rameswara. Also commentaries, by Krishnadasa, Trilochanadasa, Sundarananda, Vanadiyabhatta, Viswanatha, Gopal Chacravarti, Govindananda, Ramanda Bholanatha, &c.]

III. Sanskrit dictionaries and vocabularies by other authors.

Throughout the numerous commentaries on the Umura Kosha, the text itself is corrected or confirmed, and the interpretation and remarks of the Commentators supported, by references to other Sanskrit vocabularies. They are often cited by the scholiasts for the emendation of the text in regard to the gender of a noun, and not less frequently for a variation of orthography, or for a difference of interpretation. The authority quoted has been in general consulted before any use has been made of the quotations; or, where the original work cannot now be procured, the agreement of commentators has been admitted as authenticating the passage. This has been particularly attended to, in the chapter containing homonymous words; it having been judged useful to introduce into that chapter, the numerous additional acceptations stated in other Dictionaries, and understood to be alluded to in the Umura Kosha.

The dictionaries, which have been consulted, are 1st. The Medini, an alphabetical dictionary of homonymous terms by Medinikara. 2nd. The Viswaprakasa, by Maheswara Vaidya, a similar dictionary, but less accurate and not so well arranged. It is the ground-work of the Medini which is an improved and corrected work of great authority. Both are very frequently cited by the Commentators.

3. The Haima, a dictionary by Hema Chandra, in two parts; one containing synonymous words arranged in six chapters; the other containing homonymous terms in alphabetical order. Both are works of great excellence.

4. The Abhidana Ratnamala, a vocabulary by Halayudha in five chapters; the last of which relates to words having many acceptations. It is too concise for general use; but is sometimes quoted.

5. The Dharani, a vocabulary of words bearing many senses. It is less copious than the Medini and Haima: but being frequently cited by Commentators, has been necessarily consulted.

6. The Trikandasesha, or supplement to the Umura Kosha by Purushottama Deva.

7. The Haravali of the same author.

The last of these two supplements to Umura, being a collection of uncommon words, has not been much employed for the present publication. The other has been more used. Both are of considerable authority.

The reader will find in the notes a list of other dictionaries quoted by the Commentators, but the quotations of which have not been verified by reference to the originals, as these have not been procurable.* [Umuramala, Umura Datta, Sabdarnava, Saswata, Varnadesana, Dwirupa, Unadikosha, Ratnakosha, Ratnamala, Rantideva, Rudra, Vyadi, Rabhasa, Vopalita, Bhaguri, Ajaya, Vachaspati, Tabapala, Arunadatta.]

Works under the title of Varnadesana Dwirupa and Unadi have indeed been procured: but not the same with the books cited; many different compilations being current under those titles. The first relates to words the orthography of which is likely to be mistaken from a confusion of similar letters; the second exhibits words which are spelt in more than one way; the third relates to a certain class of derivatives, separately noticed by grammarians.

IV. Grammatical works.

Grammar is so intimately connected with the subject of this publication, that it has been of course necessary to advert to the works of Grammarians. But as they are regularly cited by the commentators, it is needless to name them as authorities, since nothing will be found to have been taken from this source, which is not countenanced by some passage in the commentaries on the Umura Kosha.

V. Treatises on the roots of Sanskrit.

Verbs not being exhibited in the Umura Kosha, which is a vocabulary of nouns only, the treatises of Maitreya, Madhava, and others on Sanskrit roots, though furnishing important materials towards a complete dictionary of the language, have been very little employed in the present work; and a particular reference to them was unnecessary, as authority will be found in the commentaries on Umura, for any thing which may have been taken from those treatises.

VI. The Scholia of classic writings.

Passages from the works of celebrated writers are cited by the commentators on the Umura Kosha; and the scholiasts of classic poems frequently quote dictionaries in support of their interpretation of difficult passages. In the compilation of a copious Sanskrit dictionary an ample use may be made of the Scholia. They have been employed for the present publication so far only as they are expressly cited by the principal commentaries on the Umura Kosha itself.

Should the reader be desirous of verifying the authorities, upon which the interpretation and notes are grounded, he will in general find the information sought by him in some one of the ten commentaries of Umura, which have been before named; and will rarely have occasion to proceed beyond those which have been specified as the works regularly consulted.

In regard to plants and animals and other objects of natural history, noticed in different chapters of this vocabulary, and especially in the 4th, 5th and 9th chapters of the 2nd book, it is proper to observe, that the ascertainment of them generally depends on the correctness of the corresponding vernacular names. The commentators seldom furnish any description or other means of ascertainment besides the current denomination in a provincial language. A view of the animal, or an examination of the plant, known to the vulgar under that denomination, enables a person conversant with natural history to determine its name according to the received nomenclature of European Botany and Zoology: but neither my inquiries, nor those of other Gentlemen, who have liberally communicated the information collected by them,* [Drs. Roxburgh, F. Buchanan, and W. Hunter, and Mr. William Carey.] nor the previous researches of Sir William Jones, have yet discovered all the plants and animals, of which the names are mentioned by the Commentaries on the Umura Kosha; and even in regard to those which have been seen by us, a source of error remains in the inaccuracy of the Commentators themselves, as is proved by the circumstance of their frequent disagreement. It must be, therefore, understood, that the correspondence of the Sanskrit names with the generic and specific names in Natural History is in many instances doubtful. When the uncertainty is great, it has usually been so expressed; but errors may exist where none have been apprehended.

It is necessary likewise to inform the reader that many of the plants, and some animals (especially fish), have not been described in any work yet published. Of such, the names have been taken from the manuscripts of Dr. Roxburgh and Dr. F. Buchanan.

Having explained the plan and design of this edition of the Umura Kosha, I have only further to state, that the delay which has arisen since it was commenced (now more than five years) has been partly occasioned by my distance from the press (the work being printed by Mr. Carey at Serampoor), and partly by avocations which have retarded the progress of collating the different copies of the text and commentaries: a task the labour of which may be judged by those who have been engaged in similar undertakings.

H. T. COLEBROOKE.

Calcutta, Dec. 1807.

***

CONTENTS

• Introduction of the Umura Kosha

• BOOK I.

o CHAPTER I.

Sect. I. Heaven, Gods, Demons; their arms, ornaments, symbols or vehicles, and other attributes. Fire; Air. Velocity. Eternity. Much.

Sect. II. Sky; weather; planets; stars.

Sect. III. Time; its divisions. Phases of the moon; eclipses.

Sect. IV. Sin; virtue; happiness. Destiny; cause. Nature. Intellect; reasoning knowledge. Senses; tastes; odours; colours

Sect. V. Speech. Language. Compositions. Modifications and circumstances of speech.

Sect. VI. Sound

Sect. VII. Music; notes, tones; instruments. Dancing. Dramatic exhibition; actors, gestures, passions. Indications of passion. Festival.

o CHAPTER II.

Sect. I. Internal regions; holes; darkness. Serpents; poison

Sect. II. Hell; departed souls; misery, pain.

Sect. III. Seas; Water, Islands; shores. Boats, ships. Fish. Lakes; ponds, wells. Rivers. Aquatic plants.

• BOOK II.

o CHAPTER I.

Earth, soil. Countries. Roads. Measures of distance.

o CHAPTER II.

Towns; buildings, habitations

o CHAPTER III.

Mountains, rocks; fountains, caves, mines. Minerals.

o CHAPTER IV.

Sect. I. Forests. Groves: gardens, avenues. Trees, plants. Trunk; root; wood; leaf; fruit

Sect. II. Trees of various kinds.

Sect. III. Plants, mostly medicinal, or with sensible qualities.

Sect. IV. Useful Plants.

Sect. V. Drugs and potherbs. Grasses and palms.

o CHAPTER V.

Lions and other quadrupeds. Insects. Birds. Pairs, flocks, heaps.

o CHAPTER VI.

Sect. I. Man. Woman. Characters, relations, circumstances of women. Kinsmen, relatives. Person, as thin, fat, &c. Freckles, moles.

Sect. II. Health. Medicine. Diseases. Diseased. Parts of the body.

Sect. III. Dress, ornaments, clothes, perfumes, garlands. Furniture.

o CHAPTER VII.

Race. Tribe. Order. Priest. Characters 'and descriptions of priests; their occupations and observances. Sacrifice; its requisites. Alms; worship; austerity; study. Hypocrisy. Marriage. Human pursuits, and objects.

o CHAPTER VIII.

Sect. I. Military tribe. Kings; ministers; officers; servants. Enemies; allies. Requisites of government; means of defence; and of success. Revenue. Foresight. Insignia of Royalty.

Sect. II. Camp; army. Elephants; horses. Chariots. Litters. Warriors. Arms and weapons. War. Slaughter, Funeral. Prison. Life.

o CHAPTER IX.

Third tribe. Professions, Husbandman. Field. Implements of husbandry. Corn, pulse, oil-seeds, &c. Granary. Kitchen. Vessels. Condiments. Prepared food. Dairy. Cattle. Traffick; weights and measures. Commodities.

o CHAPTER X.

Fourth tribe. Mixed classes. Artisans. Jugglers. Dancers. Musicians. Hunters. Servants. Barbarians. Dogs. Hogs. Chace. Theft. Nets, snares, ropes. Loom. Pole for burden. Wrought leather. Tools. Art. Images. Wages. Spirituous liquor. Gaming.

• BOOK III.

o CHAPTER I.

Epithets of persons.

o CHAPTER II.

Qualities of things

o CHAPTER III.

Miscellaneous.

o CHAPTER IV.

Sect. I. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. II. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. III. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. IV. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. V. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. VI. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. VII. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. VIII. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. IX. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. X. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XI. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XII. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XIII. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XIV. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XV. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XVI. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XVII. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XVIII. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XIX. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XX. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XXI. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XXII. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XXIII. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XXIV. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XXV. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XXVI. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XXVII. Homonymous words, Ending in [x].

Sect. XXVIII. Indeclinables (Homonyma) 371

o CHAPTER V.

Indeclinables (Synonyma).

o CHAPTER VI.

Genders.

Sect. I. Feminine.

Sect. II. Masculine.

Sect. III. Neuter.

Sect. IV. Masculine and Neuter.

Sect. V. Masculine and Feminine.

Sect. VI. Feminine and Neuter.

Sect. VII. Three genders.

Sect. VIII. Variation of gender.

Search for "Hiranya-bahu" = "O" results

****************************

Amara's Namalinganusasanam (Text), A Sanskrit Dictionary in Three Chapters Critically Edited with Introduction and English Equivalents for each word and English Word-Index

by Dr. N.G. Sardesai, L.M. & S and D.G. Padhye, Sanskrit Teacher, Modern High School, Poona

1940

Search for "Hiranya-bahu" = "O" results

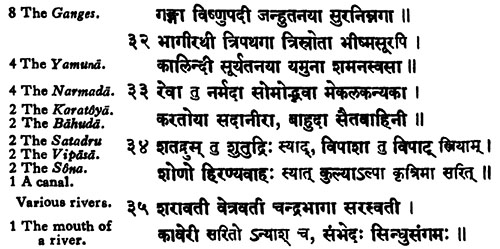

The Ganges

The Yamuna

The Narmada

The Koratoya

The Bahudd

The Satadru

The Vipasa

The Sona

A Canal.

Various rivers

The mouth of a river

Search for "gold" =

Gold, 88, 110, 120, 121,

129, 131, 132, 135, 153

„ ornament, 88

,, wrought, 88

,, image, 117

Golden age, 120

Gold-smith, 90

One made of gold.

Gold.

Gold for ornament.

A goldsmith.

Gold.

Gold.

Gold.

The golden age.

Gold.

Wrought silver and gold.

Golden necklace.

Pala of gold.

Goldsmith

Throne, golden.

Vase, golden.