by Keirissa Lawson, Tilly Brooks

CSIROscope

March 2, 2020

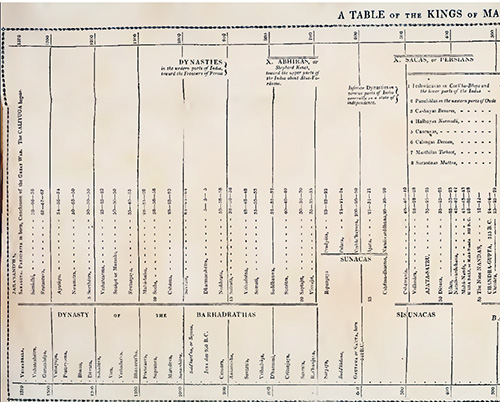

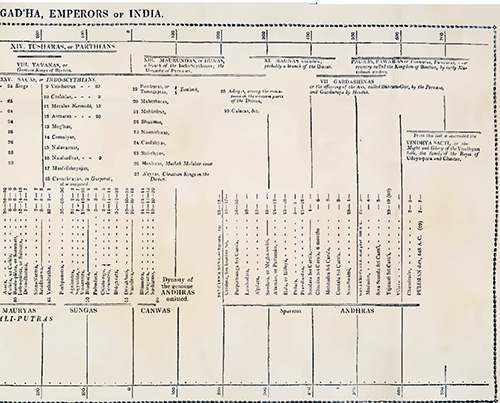

BOOK II.

Fragm. XXV.

Strab. XV. i. 35. 36,— p. 702.

Of the city Pataliputra.

According to Megasthenes the mean breadth (of the Ganges) is 100 stadia, and its least depth 20 fathoms. At the meeting of this river and another is situated Palibothra, a city eighty stadia in length and fifteen in breadth. It is of the shape of a parallelogram, and is girded with a wooden wall, pierced with loopholes for the discharge of arrows. It has a ditch in front for defence and for receiving the sewage of the city. The people in whose country this city is situated is the most distinguished in all India, and is called the Prasii. The king, in addition to his family name, must adopt the surname of Palibothros, as Sandrakottos, for instance, did, to whom Megasthenes was sent on an embassy. (This custom also prevails among the Parthians, for all are called Arsakai, though each has his own peculiar name, as Orodes, Phraates, or some other.)

Then follow these words: —

"All the country beyond the Hupanis is allowed to be very fertile, but little is accurately known regarding it. Partly from ignorance and the remoteness of its situation, everything about it is exaggerated or represented as marvellous: for instance, there are the stories of the gold-digging ants, of animals and men of peculiar shapes, and possessing wonderful faculties; as the Seres, who, they say, are so long-lived that they attain an age beyond that of two hundred years.

"They mention also an aristocratical form of government consisting of five thousand councillors, each of whom furnishes the state with an elephant."

According to Megasthenes the largest tigers are found in the country of the Prasii, &c. (Cf. Fragm. XII.)...

Fragm. XXXIX.

Strab. XV. 1. 44,— p. 706.

Of Gold-digging Ants.

Megasthenes gives the following account of those ants. Among the Derdai, a great tribe of Indians, who inhabit the mountains on the eastern borders, there is an elevated plateau about 3,000 stadia in circuit. Beneath the surface there are mines of gold, and here accordingly are found the ants which dig for that metal. They are not inferior in size to wild foxes. They run with amazing speed, and live by the produce of the chase. The time when they dig is winter.

They throw up heaps of earth, as moles do, at the mouth of the mines. The gold-dust has to be subjected to a little boiling. The people of the neighbourhood, coming secretly with beasts of burden, carry this off. If they came openly the ants would attack them, and pursue them if they fled, and would destroy both them and their cattle. So, to effect the robbery without being observed, they lay down in several different places pieces of the flesh of wild beasts, and when the ants are by this device dispersed they carry off the gold-dust. This they sell to any trader they meet with while it is still in the state of ore, for the art of fusing metals is unknown to them....

But the tiger the Indians regard as a much more powerful animal than the elephant. Nearchos tells us that he had seen the skin of a tiger, though the tiger itself he had not seen. The Indians, however, informed him that the tiger equals in size the largest horse, but that for swiftness and strength no other animal can be compared with it: for that the tiger, when it encounters the elephant, leaps up upon the head of the elephant and strangles it with ease; but that those animals which we ourselves see and call tigers are but jackals with spotted skins and larger than other jackals.

In the same way with regard to ants also, Nearchos says that he had not himself seen a specimen of the sort which other writers declared to exist in India, though he had seen many skins of them which had been brought into the Makedonian camp. But Megasthenes avers that the tradition about the ants is strictly true, -- that they are gold-diggers, not for the sake of the gold itself, but because by instinct they burrow holes in the earth to lie in, just as the tiny ants of our own country dig little holes for themselves, only those in India being larger than foxes make their burrows proportionately larger. But the ground is impregnated with gold, and the Indians thence obtain their gold. Now Megasthenes writes what he had heard from hearsay, and as I have no exacter information to give I willingly dismiss the subject of the ant.

[Notes: See Ind. Ant. vol. IV. pp. 225 seqq. whom cogent arguments are adduced to prove that the 'gold-digging ants' were originally neither, as the ancients supposed, real ants, nor, as so many eminent men of learning have supposed, larger animals mistaken for ants on account of their appearance and subterranean habits, but Tibetan miners, whose mode of life and dress was in the remotest antiquity exactly what they are at the present day.Tibet contains considerable deposits of gold, but modern methods of mining are unknown. Since ancient times they have been scooping out the soil in the Changthang with gazelle horns. An Englishman once told me that it would probably pay to treat by modern methods soil that has already been sieved by the Tibetans. Many provinces must today pay their taxes in gold-dust. But there is no more digging than is absolutely necessary, for fear of disturbing the earth-gods and attracting reprisals, and thus once more progress is retarded.

Many of the great rivers of Asia have their source in Tibet and carry down with them the gold from the mountains. But not till the rivers have reached neighbouring countries is their gold exploited. Washing for gold is only practised in a few parts of Tibet where it is particularly profitable. There are rivers in Eastern Tibet where the stream has scooped out bath-shaped cavities. Gold-dust collects in these places by itself and one has only to go and get it from time to time. As a rule the district governor takes possession of these natural gold-washings for the Government.

I always wondered why no one had thought of exploiting these treasures for personal profit. When you swim under water in any of the streams round Lhasa, you can see the gold-dust glimmering in the sunlight. But as in so many other parts of the country this natural wealth remains unexploited, mainly because the Tibetans consider this comparatively easy work too laborious for them.

-- Seven Years in Tibet, by Heinrich Harrer

"The miners of Thok-Jalung, in spite of the cold, prefer working in winter; and the number of their tents, which in summer amounts to three hundred, rises to nearly six hundred in winter. They prefer the winter, as the frozen soil then stands well, and is not likely to trouble them much by falling in."— Id.

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle, M.A., 1877

It was my intention to have described the western boundary of Anugangam [Ganges: Wiki] in the same manner as I have described the others, but I find it impossible, at least for the present. A description of the country on both sides of the said boundary would certainly prove very interesting, but the chief difficulty is that the natives of these countries insist that the Setlej formerly ran into the Caggar, or Drishadvati, and formed a large river called in Sanscrit Dhutpapa, and by Megasthenes Tutapus. This is also my opinion, but I am not sufficiently prepared at present to lay an account of it before the society.

As the Caggar, or some river falling into it, is supposed by our ancient writers to have been also the boundary of the excursions of the gold making ants toward the east, I shall give an account of them, as possibly I may not have hereafter an opportunity of resuming the subject; the legends are certainly puerile and absurd, but as they occupy a prominent place in the writings of the naturalists and geographers of classical antiquity, they may be regarded as worthy of our attention, and it may at least be considered as a not uninteresting enquiry to endeavour to ascertain their source.

Our ancient authors in the west mention certain ants in India, which were possessed of much gold in desert places amongst mountains, and which they watched constantly with the utmost care. Some even asserted that these ants were of the size of a fox, or of a Hyrcanian dog, and Pliny gives them horns and wings.

These gold making ants are not absolutely unknown in India, but the ant in the shape and of the size of a Hyrcanian dog was known only on the borders of India and in Persia. The gold making ants of the Hindus are truly ants, and of that sort called Termites. To those, however, birds are generally substituted in India; they are mentioned in the institutes of Menu* [P. 353.] and there called Hemacaras, or gold makers. They are represented as of a vast size, living in the mountains to the N.W. of India, and whose dung, mixing with a sort of sand peculiar to that country, the mixture becomes gold. The learned here made the same observation to me as they did to Ctesias formerly, that these birds, having no occasion for gold, did not care for it, and of course did not watch it; but that the people, whose business it was to search for gold, were always in imminent danger from the wild and ferocious animals which infested the country. This was also the opinion of St. Jerome in one of his epistles to Rusticus.

These birds are called Hemacaras, or gold makers; but Garuda, or the eagle, is styled Swarna-chura, or he who steals gold, in common with the tribes of magpies and crows who will carry away gold, silver, and any thing bright and shining.

Garuda is often represented somewhat like a griffin with the head, and wings of an eagle, the body and legs of a man, but with the talons of the eagle. He is often painted upon the walls of houses, and generally about the size of a man. This is really the griffin of the Hindus, but he is never even suspected of purloining the gold of the Hemacara birds.

The large ant of the size of a fox, or of a Hyrcanian dog, is the Yuz of the Persians, in Sanscrit Chittraca-Vyaghra, or spotted tyger in Hindi Chitta, which denomination has some affinity with Cheunta, or Chyonta, a large ant. This has been, in my opinion, the cause of this ridiculous and foolish mistake of some of our ancient writers. The Yuz is thus described in the Ayin Acberi.(3) "This animal, who is remarkable for his provident and circumspect conduct, is an inhabitant of the wilds, and has three different places of resort. They feed in one place, rest in another, and sport in another, which is their most frequent resort. This is generally under the shade of a tree, the circuit of which they keep very clean, and enclose it with their dung. Their dung, in the Hindovee language, is called Akhir.”

Abul-Fazil, it is true, does not say positively that their dung, mixing with sand, becomes gold, and probably he did not believe it. However, when he says that this dung was called Akhir in Hindi, it implies the transmutation of the mixture into gold. Akhir is for Chir in the spoken dialects, from the Sanscrit Cshira; from this are derived the Arabic words Acsir, and El-acsir-Elixir is water, milk also, and a liquid in general. To effect this transmutation of bodies the Hindus have two powerful agents, one liquid called emphatically Cshir, or the water. The other is solid, and is called Mani, or the jewel; and this is our philosopher’s stone, generally called Spars a-mani, the jewel of wealth; Hiranya-mani, the golden jewel. There are really lumps of gold dust, consolidated together by some unknown substance, which was probably supposed to be the indurated dung of large birds.I cannot help mentioning a discovery which accident threw in my way, though my proofs must be reserved for an essay which I have destined for the fourth volume of your Transactions. To fix the situation of that Palibothra (for there may have been several of the name) which was visited and described by Megasthenes, had always appeared a very difficult problem, for though it could not have been Prayaga, where no ancient metropolis ever stood, nor Canyacubja, which has no epithet at all resembling the word used by the Greeks; nor Gaur, otherwise called Lacshmanavati, which all know to be a town comparatively modern, yet we could not confidently decide that it was Pataliputra, though names and most circumstances nearly correspond, because that renowned capital extended from the confluence of the Sone and the Ganges to the site of Patna, while Palibothra stood at the junction of the Ganges and Erannoboas, which the accurate M. D'Anville had pronounced to be the Yamuna; but this only difficulty was removed, when I found in a classical Sanscrit book, near 2000 years old, that Hiranyabahu, or golden armed, which the Greeks changed into Erannoboas, or the river with a lovely murmur, was in fact another name for the Sona itself; though Megasthenes, from ignorance or inattention, has named them separately. This discovery led to another of greater moment, for Chandragupta, who, from a military adventurer, became like Sandracottus the sovereign of Upper Hindustan, actually fixed the seat of his empire at Pataliputra, where he received ambassadors from foreign princes; and was no other than that very Sandracottus who concluded a treaty with Seleucus Nicator...

-- Discourse X. Delivered February 28, 1793, P. 192, Excerpt from "Discourses Delivered Before the Asiatic Society: And Miscellaneous Papers, on The Religion, Poetry, Literature, Etc. of the Nations of India", by Sir William JonesScholar-Shit!

These are to be met with in the N.W. of India, where gold dust is to be found. They contain much gold, it is said, and are sold by the weight.

In Sanscrit these lumps are called Swarna-macshicas, because they are supposed to be the work of certain Macshicas, or flies, called by us flying ants, because in the latter end of the rains they spring up from the ground in the evening, flying about in vast numbers, so as to fill up every room in which there are candles lighted, to the great annoyance of the people in them. These flies are one of the three orders of termites, apparently of a very different, though really of the same, species. This third order consists of winged and perfect insects, which alone are capable of propagation. These never work, nor fight, and of course if they can be said to make gold it must be through the agency of their own offspring, the labourers, or working termites, which in countries abounding with gold dust are supposed to swallow some of this dust and to void it, either along with their excrements, or to throw it up again at the mouth. According to the Geographical Comment on the Maha-Bharata, the Suvarna-Macshica mountains are on the banks of the Vitasta. There are also Macshicas producing silver, brass, &c. I never saw any, but Mr. Wilson informs me that they are only pyrites, and indeed, according to Pliny, there were gold and silver and copper pyrites. Alchemists, who see gold everywhere, pretended formerly that there was really gold and silver in them, though not easily extracted. If so, it must have been accidentally. These were called Pyrites auriferi, argentei, and Chalco-pyrites. The pyrites argentei are called, in a more modern language, Marcassita-argentea.

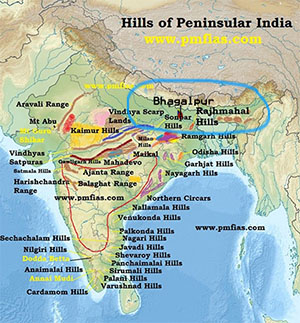

These gold making birds, flies, and spotted tygers, are by the Hindus confined to the N.W. parts of India; and the Yuz, according to the Ayin Acberi, begins to be seen about forty Cos beyond Agra. Elian is of that opinion also, when he says that the gold making ants never went beyond the river Campylis, and Ctesias, I believe, with MEGASTHENES likewise, places them in that part of India. The Campylis, now Cambali, is a considerable stream, four miles to the west of Ambala toward Sirhind, and it falls into the Drishadvati, now the Caggar, which is the common boundary of the east and north-west divisions of India, according to a curious passage from the commentaries on the Vedas, and kindly communicated to me by Mr. Colebrooke, our late President.

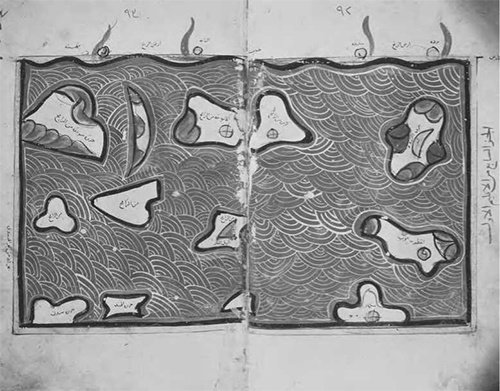

Plate IX

-- VII. On the ancient Geography of India, by Lieut. Col. F. Wilford

On January 29 we find Max Muller writing to Burnouf to inquire about the Prix Volney, a prize founded by Volney for the best work on language, written in any language during the year, and sent in for competition. He asks if his paper on the relation of Bengali to the other Indian languages, read before the British Association, was of sufficient importance to have any chance of winning the prize. Burnouf had noticed the little article very favourably in the Journal Asiatique. Max Muller ends his letter thus: —'The printing of the Rig-veda goes on very slowly, and yet I give up nearly all the day to it, and often the night also. Ninety sheets are printed, up to half of the sixth Adhyaya, but I have undertaken a little too much, and I find I have not much time to study for myself, and arrange in some sort the results of my researches, I shall have to be content with presenting only the materials to the learned world, and all I wish is that they may find the text of my edition correct according to the MSS., and that others who are more worthy, and more skilful than I am for discoveries in the highest philology, may draw the inferences. In any case the mines of the Rig-veda are not the mines of California; the grains of gold are not to be found so near the surface that the pipilakas1 [Gold-finding ants in the Mahabharata.] can find them without any effort. It is for me to act as miner and for others to sift the ore; for it is given to few persons to do both, as you have done for the Zend-Avesta.'

-- The Life and Letters of The Right Honourable Friedrich Max Muller, In Two Volumes, With Portraits and Other Illustrations, Edited by His Wife [Georgina Adelaide Grenfell Muller], 1902

Zinc isotopes found in manganese crust samples of soils and termite mounds are helping mineral explorers find hidden deposits of critical metals below the surface.

The blue shimmer of manganese crust on this termite mound in the southern Pilbara region of WA [Western Australia], contains zinc isotopes.

Metallic blue manganese crusts are showing up on termite mounds in the Pilbara region of WA [Western Australia]. It looks like the mound has bling growing on it. So why are these termite mounds shining? Our researchers found the blue-grey shading may be secret signposts, revealing the presence of base metals. It’s more than a home improvement for this termite colony.

I saw the sign(post)

The hunt is on globally to find critical metals like nickel and cobalt, to not only build electric vehicles, but also batteries to store renewable energy. Finding new deposits of these metals is crucial to meet this rising demand. Our researchers found that the manganese crusts on termite mounds and in soils, could reveal the presence of these metals beneath the surface.

Has anyone seen my metal detector?

While we might not fit the image of your average metal detectorist, we do have some super-fly high-tech kit! Our latest exploration toolkit takes a 21st century twist, it’s sub-atomic! Our scientists recently used techniques which can examine the heart of an atom.

Isotopes are variations of the same element which differ in the number of a sub-atomic particles called a neutron, that are contained in the atom. We discovered heavy isotopes of zinc were binding to samples of manganese crusts found on termite mounds, and also in soil. This created an ‘anomalous’ signal which acts as a signpost for metal deposits hidden underground.

The manganese crust visible on the ground in the Pilbara.

How does zinc help us find other metals?

In mineral exploration, zinc is often considered a pathfinder element that occurs in close association with other sought-after elements. Zinc is often found in combination with other metals, like cobalt and nickel. It’s also mobile in the environment, dissolving in water and moving around to interact with other chemicals.

Our senior research geoscientist, Sam Spinks, explained the level of accuracy they can achieve. “This new research shows we can now measure zinc variations, or isotopes, so accurately, we can identify what metal deposit lies deep underground,” he said. “Australian explorers need new, cost-effective techniques to find the next generation of deposits below the surface.”

In recent years, Australian exploration companies have been analysing samples from termite mounds while digging for gold. Now zinc offers another technique mineral explorers can use to find a range of metals.

The research findings have been published in the journal Chemical Geology, and available for our partners to use in exploration.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen signs of minerals below on the Earth’s surface. We also discovered gold digging fungi.

************************

Termites produce what semiconductor industry needs

by K. S. Jayaraman

Published online 13 January 2014

The popular image of termites as major agricultural pests and destroyer of buildings may have to change.

Termites, nature's metallurgical engineers. © Dinodia Photos/Alamy

Some 1500 years ago Varaha Mihira an Indian astronomer, mathematician, and astrologer, in his treatise "Brihat Samhita" refers to termite mounds as indicators of underground water. Now researchers report1 that termites are also nature's metallurgical engineers. They have found that the hills which they build are an excellent source of quartz (SiO2) — a raw material for the semiconductor industry.

Through their routine activities, termites infuse substantial modifications to the soil on which the hill is built. The mounds are generally made up of sand grains and fine cellulose materials, which are coated with some sticky but readily hardening materials secreted by termites through their mouth or rectum.

The sculptured mounds shaped like mushroom, pyramid or cone created by these insects can be as big as five meters tall and eight meters in diameter. Termite hill soils become as hard as rocks on drying and their strength grows with time. They are well known for their high refractory properties since ancient times and find applications in brick making and house building.

"These interesting features of termite hill soils motivated us to study their physical and chemical properties using various analytical techniques," the researchers said. Although there are many reports about the beneficial qualities of termite hills, according to the scientists, "only a few mention or discuss the elemental composition and microstructures of the termite hills."

For their work, they collected termite mound soil samples from two different places: from a village near Dehradun in Uttarakhand and from a forest in Hauz Khas close to the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Delhi. They characterized the samples using powder X-ray diffraction, transmission electron microscope and field emission scanning electron microscopy. Quartz was found in both the samples. The Delhi sample also contained the rare 'cristobalite' phase of SiO2.

Quartz which is a source for silicones, silicon and many other compounds of commercial importance, is crucial for a variety of applications in the semiconductor and software industry. Because of its outstanding thermal and chemical stability, quartz is widely used in many large-scale applications concerned with abrasives, ceramics and cement industry.

In nature quartz is found in igneous rocks like granite, sedimentary rocks like sandstone and shale. It is also present in sand and carbonate rocks. However, according to the report, natural quartz crystals contain too many chemical impurities and physical flaws and so are unsuitable for direct applications in industry. "The process of separation and extraction of quartz from sand and rocks is a multi-step process which includes physical and chemical methods of purification." Furthermore, the commercial processes of manufacturing pure, flawless, electronics-grade quartz called "cultured quartz" used in industry, involves highly controlled laboratory conditions.

According to the researchers, the termite mounds are source of quartz, available as SiO2 and also as the less common 'cristobalite' form of silica depending on their location. They found that apart from silica (as the major constituent), the termite hill soils also contain oxides of iron, magnesium and aluminum in considerable amounts. It has been earlier reported by other groups that termite hill soil contains as much as 20% of the total nitrogen as inorganic nitrogen, an average organic carbon content of 9.3% and 2.25 times more phosphorus than normal soil besides essential plant nutrients like potassium and calcium. The researchers said that all this suggests that "termite hill soils can be used over agricultural lands deficient in these elements."

While the studies highlight the possibility of producing quartz from all termite hills, "the soils need to be analysed before being used for any specific application, as composition and morphology may vary from location to location."

The authors of this work are from: the Institute of Nano Science and Technology, Mohali; Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi and Hindu College, University of Delhi, India.

References

Ganguli, A. K. et al. Nanocrystalline silica from termite mounds. Current Science. 106, 83-88 (2014) Article

************************

Why Indians worship the mound of the much-hated termite: The misunderstood termite can teach many lessons to architects and fans of sustainable living.

by Geetha Iyer

Scroll.in

Mar 09, 2017 · 03:30 pm

The Perumpanarruppatai, a poetic work in Tamil from the Sangam period between 300 BCE and 100 CE, has a stanza that compares freshly sprouting rice grain with the termites found in their mounds. These lines sprang to my mind when I first saw the television commercial for Century Ply, a company that manufactures plywoods – fat, padded termite bodies on the insides of a kitchen cupboard. Living in a 175-year-old house made of mud and wood, termites and cockroaches are a familiar sight. Every time I see ads for insect repellents which tell the public how good their products are, I marvel at how little humans know about the creatures we share space with.

Perish the thought that termites are fat or ugly. The only fat, obese termite is the queen, when she is filled with eggs. The rank and file of termites who feed, clean and take care of her, working to expand the colony, are smart, lean and mean, despite the fact that termites feed on a carbo-rich diet of wood, soil, grass, litter and even animal dung. Concrete is no barrier either, a small crack is all they need to start occupying space. The greatest secret to their success, is their choice of food: they exploit an exclusive and abundant food source, a biomolecule called lignocellulose, which no other creature, not even other insects, can eat. Since lignocellulose does not degrade easily, termites can access it from living plants and dead wood or soil too.

To consider termites plunderers is unfair. They are the most important animals in a forest ecosystem, single-handedly decomposing 40% to 100% of the decaying wood and thereby enriching the soil. Subterranean termites, which are among the ones that bothers us humans, serve us well too. As they tunnel through the soil, building swarming tubes to forage for food, they increase the soil’s porosity, facilitating greater percolation of water. Termites are known to dig as deep as over 100 feet in search of water to maintain the humidity of their mounds. As early as 500 CE, Indian astronomer Varahamihira wrote in the Brihat-Samhita that termite mounds were indicators of ground water and mineral deposits.

Not all termites build those iconic mounds. Many reside in carton nests. Some are open-air processional column termites, foraging on tree trunks or living off leaf litter and nesting on tree branches or decaying roots. Carton or mounds – over a period of 55 million years of existence – termites have learnt how to manage their constructions efficiently, keeping them well ventilated and maintaining the temperatures needed for their survival.

The open-air foragers nest on tree branches or decaying roots. To avoid predation by ants and other arthropods, termites squirt sticky fluids onto foraging surfaces. Spiders or ants who venture too close get stuck and are also affected by these chemicals. If they move, the workers will bite or hold them down, until other termite-soldiers can come and spray some some more before finishing them off. The squirting apparatus of the termite-soldier is precise and efficient.

The carton nests of termites from the sub-family, Nasutitermitinae, can be seen at the Kanyakumari wildlife sanctuary. The Kani tribe feed these termites to their chickens. In the desert ecosystem, termite species live on the dung of hoofed mammals, besides feeding on leaf litter.

Every time the termite feeds or builds, it modifies the habitat for the benefit of other organisms including humans. This might explain why termite mounds, mistakenly called ant hills, are worshipped – the clay from termite mounds was used to build Vedic fire altars and included in the Rajasuya yagna performed by kings.

Termite soldiers guarding the nest. Credit: Geetha Iyer

What makes termites so successful? Their food source, caste system and their ability to produce large colonies.[!!!] There is no realistic account of how large a subterranean colony of termites can be because most data is extrapolated from limited studies. A termite colony has a king and queen who pair for life, mating repeatedly to build their vast empire. Other social insects do not pair for life. Apart from workers and soldiers, the colony also has secondary reproductives capable of laying eggs and expanding their colony. Should the king or the queen die, the secondaries step into their roles, yet another reason for the dominance of termites. Sometimes even when the queen is active, the secondary reproductives produce eggs. The colony prospers and humans despair.

Alates or winged termites emerge during the monsoon to establish new colonies. A tiny crack in the wall or floor is enough for them to enter an underground world. Alates die if they do not find a mate. In rural India they are gathered to be eaten, the fat, juicy termite queen in particular, is considered nutritious and a delicacy. It is only the alates who see well – the workers and soldiers are either blind or have poor vision. The way termites communicate can help humans fine-tune communication technology. If you watch a procession of termites in the forest, you can actually hear them move – they do so by hitting their head on the soil. The sound is so rhythmic, that in the silence of a forest it sounds like a march-past.

Termite alate. Credit: Geetha Iyer

Termites process cellulose and lignin by the exclusive army of microbes found nowhere but in the gut of a termite. Evolutionary scientists have hailed the diversity of termite-gut microbes as a sterling example of co-evolution. These microbes are acquired through a unique process called anal trophallaxis – or anal to mouth feeding. Every time a termite moults, it sheds its outer skin as well as its gut lining, where the microbes reside. Newly moulted termites feed from the delicious anal fluids secreted by other adult termites to re-inoculate their gut. The workers must eat constantly, the soldiers cannot eat as their mandibles (a pair of appendages near the mouth) are modified for defence. They and the reproductive castes obtain their nutrients from the workers through oral or anal trophallaxis.

Anal feeding is a common practice in lower groups of termites. The more evolved ones from the family Termitidae cultivate a variety of fungi in their nests. These fungi grow on the faeces of the termite and in turn provide food for them. Termites believe in sustainable living – they re-cycle or consume everything from dead nest mates, moults to excreta. Faeces are used to build quarantines, construct swarming and often gravity-defying exploratory tubes. These tubes provide moisture for subterranean termites when they forage outside their nests.

Termites have also inspired African architect Mick Pearce – two buildings designed by him, the Eastgate Centre in Harare, Zimbabwe, and the Council House in Melbourne are a testimony to what one can learn from these tiny, visually challenged yet fiendishly clever and socially adaptive insects.

************************