French Jesuit Scientists in India: Historical Astronomy in the Discourse on India, 1670-1770

by Dhruv Raina

Economic and Political Weekly

Vol. 34, No. 5

Jan. 30 - Feb. 5, 1999

-- Rules of the Siamese Astronomy, for calculating the Motions of the Sun and Moon, translated from the Siamese, and since examined and explained by M. Cassini, a Member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, Excerpt from "A New Historical Relation of the Kingdom of Siam", Tome II, by Monsieur De La Loubere

-- Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India About A.D. 1080, by Dr. Edward C. Sachau, Professor in the Royal University of Berlin and Principal of the Seminary for Oriental Languages; Member of the Royal Academy of Berlin, and Corresponding Member of the Imperial Academy of Vienna, Honorary Member of the Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, London, and of the American Oriental Society, Cambridge, USA, 1910

-- Ancient Indian Astronomy in Vedic Texts, by R.N. Iyengar

-- Royal Astronomical Society [Astronomical Society of London], by Wikipedia

-- Some Purana References, from "Astronomical Dating of the Mahabharata War, by Dieter Koch"

-- Astronomical Dating of the Mahabharata War, by Dieter Koch

-- Determination of the Date of the Mahabharata: The Possibility Thereof, [Reprinted from Vishveshvaram and Indological Journal, Vol. XI

The intellectual activity finally culminating in the grand theoretical syntheses of the celestial sciences towards the end of the 18th century followed a century's toil undertaken by Jesuit scientists and traveller's posted outside Europe. This essay briefly addressed the endeavour of the French Jesuits who landed in India during the late 17th and first half of the 18th centuries. The Jesuit scientists of the period were inaugurators of a discourse on India and Indian historical astronomy marked by ambiguity, where fascination and dismissal go together; where the enchantment with the new world and its distinct knowledge forms provide the occasion for enriching the self in cognitive and cultural terms, and through an act of distantiation [mental or emotional distance], of redefining the self as superior.

A true man of the church, he intended to prove that the Bible had not lied, but also a man of science, he wanted to make the Sacred Text agree with the results of the research of his own time. And to this end he had collected fossils, explored the lands of the Orient to discover something on the peak of Mount Ararat, and made very careful calculations of the putative dimensions of the Ark.

-- Umberto Eco. The Island of the Day Before.

THE 18th century legacy of the history of science for long ensured that the role of the Jesuits in the advance of modern science was underplayed. This lack of attention was partially the product of an ideological fixation concerning the antagonism between science and religion. In fact, late 19th and early 20th century historiography had been habituated to the idea that science and religion were pathologically opposed to each other. The overplayed Galileo episode has for sometime been interpreted by historians of science as being a specific manifestation of the relation between the views of some natural philosophers and the interests of religious institutions [Wallace 194]. Furthermore, throughout the medieval ages into the age of modernity institutions of Christian religion had evolved with traditional bodies of natural knowledge (Shapin 1996: 136]. The ecumenical Merton thesis has done a great deal to deflect our simplistic fixation with the conflictual model. According to this thesis, where "science prospered in early modern times, it derived important support and reinforcement from organised religion" [Heilbron 199: 11]. A variety of astronomy that emerged in Jesuit institutions in Italy in the 17th century gradually blossomed into an active tradition of Jesuit science in France in the 18th century. This tradition has been little researched (Harris 1989: 41]: despite the fact that the Jesuit writings on the sciences constitute a fairly substantial corpus.

Between the years 1600 and 1773, the year when the Society of Jesus was suppressed, Jesuit scientists had authored more than 4,000 published works, about 600 journal articles appeared after 1700, and about 1,000 manuscripts were available. The society's known publications include 6,000 scientific works covering areas such as Aristotelian natural philosophy, medicine, philosophy, astronomy and mathematics [Harris: 41]. The scientific writing of the Jesuits fall into six broad categories. Of the six, three of immediate concern to us include textbooks and treatises on Euclidean geometry and mixed mathematics, treatises, opuscules and journal articles on observational astronomy, and academic publications on experimental and natural philosophy [Harris: 42]. About 40 percent of the Jesuit literary output from the foreign apostolates dealt with astronomy. These included important eclipse observations, other celestial events such as the transit of Venus, and the correction of longitudes of important places.1 These efforts furthered the determination of the shape of the earth [Harris: 56], and in a less direct way provided the grounding for the finalisation of celestial mechanics, that more or less closed the era of Laplacian physics by the 1830s [Pyenson 1993: 4].

Amongst the French members of the Society of Jesus were many astronomers.2 These contributions included the determination of latitudes and longitudes for all of China, the observation of solar and lunar eclipses as well as of eclipses of Jupiter's satellites, the passage of Mercury through the solar disc -- to mention a few. These Jesuit astronomers also initiated studies on ancient Chinese records and observations, in order to analyse Chinese chronology. In fact, it was a similar interest that led them onto the study of Chinese, Indian and Egyptian history [Han 1995: 491]. These astronomical observations in Chinese were often used to determine the accuracy of Chinese history, and hence these Jesuit scientists were the progenitors of Chinese historical astronomy [Han: 492].

The historian of science, S.N. Sen, remarked in an important paper, that unlike the case of China, the Jesuits in India made little contribution to the growth of modern science [Sen 1988: 114]. However, some of Sen's own research into the history of astronomy requires a revision of the hypothesis. The Jesuit project in India was certainly not on as grand a scale as it was in China. Nevertheless, despite internal dissension within the Jesuit order, witnessed both in India and China, the Jesuits inaugurated the historical inquiry into ancient Indian astronomy (as they did in China) by providing both the impetus and material for French savants and astronomers to develop their histoires de l'astronomie. Furthermore, the efforts of French Jesuit astronomers in India and China mutually complemented each other. The institutional and administrative organisation of Jesuit science was ensured through the disciplinary structures of the Society of Jesus that reinforced a 'high level of group coherence and loyalty' [Harris 1989: 39]. Jesuit superiors stationed at foreign apostolates were thus required to send detailed reports and edifying news, in the hope of winning over new apostates, to Rome and western European metropolises [Harris: 57].

Three different interests, Jami points out, converged in the formation of the French Jesuit missions. and subsequently deciding their research agenda. In the first instance the director of the Paris observatory in the 1670s Gian-Domenico Cassini (1624-1712) submitted a proposal to the minister Colbert to send Jesuits to China to make some astronomical observations, and to advance their knowledge of latitudes, longitudes and magnetic declinations. Secondly, the French king was compelled by French Jesuit interests to augment support for Catholic missions abroad, since it was binding upon the "Church's eldest daughter", to do so. The third, was part of a larger proposal to send French embassies to Asian courts [Jami 1995: 495]. One of the missions that was sent to Thailand finally landed up in Pondicherry.

A leading French astronomer stationed in China was Pere Antoine Gaubil (1689-1759), whose astronomical researches had exercised influence on the French astronomer, theorist and mathematical physicist, Pierre Simon Laplace (1749-1827). Gaubil researched into traditional Chinese astronomy, and proposed that the changing obliquity of the ecliptic should be adopted from Chinese astronomical sources. As indicated earlier, Gaubil was instrumental in creating a formation that one could call 'historical astronomy' -- for convenience we shall take the term to designate the project of probing historical records for celestial events that could retrospectively result in the revision or validation of contemporary astronomical practice. This is evidenced in some of his important books such as 'Histoire abregee de l'astronomie chinoise', Paris, 1729; 'Histoire de l'Astronomie chinoise' that first appeared in volume 31 of the Lettres edifiantes; and Traite de la chronologie chinoise -- while this manuscript was sent to Paris in 1749, it was Laplace who discovered a copy in the library of the Bureau des Longitudes [Dieny 1995: 503].

Pere Gaubil was in constant touch with the French Jesuit astronomer and cartographer Pere Claude Stanisla Boudier (1687-1757) stationed at Chandernagor in India. Boudier's reputation as an astronomer earned him an invitation to Jai Singh' s court in 1734. During his journey to and sojourn at Jaipur, he, like his counterparts in China determined the longitude of 63 Indian cities, in addition to measuring the meridional altitudes of a few stars. [Ansari 1985: 372]. In addition, he observed the first satellite of Jupiter on April 2, 1734 at Fatehpur, and again at Jaipur on August 15 of the same year. He also observed the solar eclipse of May 3, 1734 at Delhi and had earlier reported the lunar eclipse of December 1, 1732. Pere Gaubil however considered that Pere Boudier's estimates of the diameter of the sun were on the higher side. It appears, that just as the French Jesuits provided the last accurate figures of the longitudes of the leading Chinese cities, Boudier did the same for Delhi and Agra [Ansari 1985: 372].

The historian of astronomy, Ansari tries to draw a parallel between the perseverance of the Jesuits in India and China. He is right in observing the neglect of scientific textual scholarship of the Jesuits in India; but then the phase of European textual scholarship in and on the sciences of India really commenced much after the Society of Jesus had been suppressed.4 Regarding the place of Jesuit scientists in the court of the Chinese emperor and that of the Moghuls, Ansari's remarks are less conclusive. But the third point that the French Jesuits in India, unlike their Chinese counterparts were not good scientists and were not in contact with the best scientists in Europe is at best an overstatement [Ansari 1985: 374-75] It is true that not all the Jesuit astronomers in India were in touch with the leading French astronomers located at Paris. It is nevertheless incontestably true that their reports and records became the source material for three subsequent generations of French astronomers: Le Gentil, Bailly, Laplace and Delambre. This in any case does not detract from the point that the Jesuits did not bring the Copernican revolution to the east, that its impact on Indian astronomy was minimal [Sharma 1982: 351]. We now come to the specific context of the French Jesuits who came to India, their writing, who they were and what source material they provided on the ancient astronomy of India.

FOUNDING OF THREE FRENCH JESUIT MISSIONS

The tenure of the European Jesuits in India dates back to the 16th century. But our purpose is not an essay that constructs the entire Jesuit corpus as one homogeneous text. On the contrary, internal political and doctrinal differences emerged within the Jesuit order as a consequence, not only of different intellectual traditions and social orderings, but more importantly of the rivalry between different European states.5 In this particular case, we shall not discuss the programme of the Portuguese Jesuits in Goa in the 16th century.6 The focus of our attention are the French Jesuits who arrived in India towards the end of the 17th and the early decades of the 18th centuries.

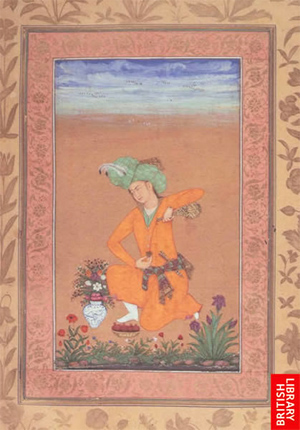

The counter reformation provided the backdrop for the first Portuguese Jesuits who arrived in Goa in the first half of the 16th century; and were propelled by the forceful colonising and evangelising impulse, manifest in rituals of 'slash and burn' evangelisation [Zupanov 1993: 136]. Another interpretive tradition found its expression in the evangelical efforts of the Italian Jesuit, Roberto Nobili, founder of the Madurai Mission. This strategy, Zupanov calls the 'adaptationist method of conversion' -- accomodatio -- was developed by Italian missionaries for Asian countries [Zupanov 1993: 124], and possibly came out of the Collegio Romano where this art of Jesuit conversion was rehearsed. This method was premised upon a humanist theological universalism [Zupanov 1993: 123], that was quite at variance with that of the Portuguese order. This strategy of accomodatio was in measure adopted by the French Jesuits who came to India and founded the Missions at Pondicherry, Mysore and Chandernagore. With the democratisation of knowledge that marked 17th century Europe, the lower literate social orders, from whose ranks some of the Jesuits came, were also engaged in the colonial enterprise. These figures came around to considering themselves "superior to any learned Brahman", and found the "colonial setting fertile ground for this kind of psychological...official promotion" [Zupanov 1993: 143].

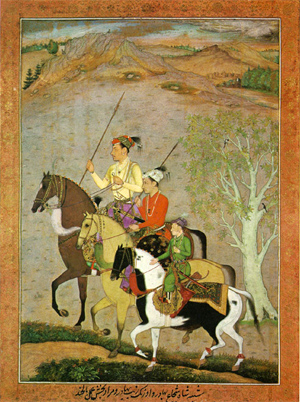

In the late 17th century, there were two distinct phases marking the relationship between French travellers and Jesuits with princes of several Indian states. The first was a period of 20 years, from 1666 to 1686. The French saw the geographical expanse of the Indian subcontinent as politically divided in two: the Mongol ruled India of the north that was more or less independent from 'l'Inde pathane' and 'l'Inde carnatic'. As far as the French were concerned this period coincided with that of the relative prosperity of the Compagnie royale francaise, which indicated that the French had the necessary resources for the creation and extension of their commercial interests [Duarte 1932: 195]. Their first explorations were purely of a territorial nature, and the political leaders adopted a policy of reconciliation [Duarte 1932: 196]. This was reflected even in the Jesuit programme of evangelisation.

The second period also extended over 20 years: from 1686-1706. Difficulties began appearing in 1677 and climaxed in 1679. By 1706 the Compagnie des Indes Orientales had all but disappeared, and was reconstituted in 1719. But this time it did not survive through its own efforts, having sold its monopoly to private societies. During this period French policy was limited to prudently and surreptitiously increasing the number of their posts, while awaiting favourable times [Duarte 1932: 196].

The death of Saint Francis Xavier appeared to have marked the deceleration of the Portuguese proselytising fury in India. It was for Pere Roberto de Nobili to show that the contempt of the indigenous population towards the missionaries was the cause of the decline of missionary effort. He then set about reversing the trend. It was for him to inform Rome that: "We imagine that these people are ignorant, but I assure you that they are not. I am actually reading one of their books in which I learn philosophy anew almost in the same terms as I studied it at Rome, though of course, their philosophy is fundamentally different from ours" [quoted in Zupanov 1993: 126]. This hermeneutic discernment sought to propose that Hindu customs and rites could not only be incorporated into Christianity, but justified within Christian theology [Zupanov 1993: 127]. Zupanov conjectures that Nobili's aristocratic background possibly accounted for his extra-sensitivity "in detecting and acknowledging...non-European analogues". This proto-emic [???] approach of seeing the world through the eyes of the other may have licensed "both epistemic condescension and intellectual curiosity" [Zupanov 1993: 143].

GEODESY AND CHRONOLOGY IN LETTRES OF JESUITS

The French Jesuits arrived in their evangelical role on the Coromandel coast; the French king having sent these missionaries versed in the sciences of Europe to India. Peres Tachard, Fontenay, Bouvet, Gerbillon, Le Comte and Visdelou were the first French missionaries to arrive in India. As the 18th century commenced there were three large French missions located in southern India: the Madurai missions founded by Nobili in 1608: the Mysore mission that was first run by the Dominicans and later by the Franciscans. Neither of them left traces of their work, and it was left to the French Jesuits to refound the mission [Bamboat 1933: 851. The third was the Carnatic mission that commenced at Pondicherry and was founded by members of the Society of Jesus who landed at Pondicherry after they were expelled during the course of a revolution in Thailand. The most notable of these Jesuits were Peres Tachard, Mauduit8 and Bouchet [Bamboat 1933: 85].

Pere Tachard was among the first French missionaries of the Society of Jesus to choose India as the "theater for their apostolic work", having been sent by Louis XIV to Thailand in 1685. He learnt the language of the country and in 1686 accompanied the French ambassador to Thailand to meet Louis XIV and the Sovereign Pontiff. He returned to Thailand in 1687, but two years later following a coup against the king and his minister, he retired to Pondicherry with other missionaries and remained there till 1693. When Pondicherry fell to the Dutch, he was arrested and sent to Europe. He returned to Surat in India in 1696 and later founded a small seminary at Chandernagor [Bamboat 1933: 89]. He went on to found the Carnatic mission and sent Jesuits to the hinterland of the province. He had a reputation for making accurate astronomical observations that are contained in his diary and letters; in addition to which there are important remarks on the geography of the region [Bamboat 1933: 90-91].

In fact, in the year 1687 he visited Louis XIV in Paris with the French ambassador to Siam, M de la Loubere, and carried a Sanskrit manuscript from Thailand. This manuscript contained rules for the computation of the longitudes of the sun and the moon. In its own time, it was to exercise the scientific skills of Gian-Dominique Cassini, then heading the Paris observatory, before he could translate the computational rules contained therein into the language of modern astronomy [Sen 1985: 49]. Cassini's computations were presented in the Memoires of French Royal Academy. Based on the ratio of omitted lunar days to the total number of days, that Cassini took to be 11/703, he calculated the synodic month to be 29 days, 12 hours 44 minutes and 2.39 seconds. Having established that 228 solar months were equivalent to 235 lunar months, Cassini showed that the metonic cycles were known to the Indians who had generated these astronomical rules [Sen 1985: 50]. The sun underwent 800 revolutions over a computed period of 2,92,207 days, and Cassini estimated the length of the sidereal year to be 365 days, 6 hours, 12 minutes and 36 seconds. Since this figure agreed with the value obtained in the Paulisa Siddhanta of Varahamihira, it was much later argued that these computational rules were derived from the latter text [Sen 1985: 50].

Pere Papin was one of the first missionaries in India and was appointed Superior in Bengal in 1711. His letters and writings provide important information on the industry and medical practices of the region.9 Like Pere Tachard, Pere Bouchet was a member of the expedition to Thailand in 1687. But the revolution of 1688 brought him to the province of Malabar. He was later sent to the Madurai mission. [Bamboat 1933: 93]. Bouchet opened up a discussion on metempsychosis and, shall we say, comparative philosophy. His detailed letter to M Huet, the former Bishop of Avranches [Lettres, 1810, Tome 12: 136-93], discussed the points of convergence of Pythagorean and Indian metempsychosis. As a Catholic, he was naturally perplexed by the doctrine of transmigration of the soul, and so embarked on a comparative discussion on the doctrine of the soul amongst the Indians, Pythagoreans, the Platonists and the Christians, and naturally sets up a distance between the former three and the latter [Lettres 1810, Tome 12: 145-53]. But what is most significant, is the preoccupation with, on the one hand eschatology [the part of theology concerned with death, judgment, and the final destiny of the soul and of humankind.], and on the other Indian cosmology, the theory of the beginning and the end of the world, the Indian book of genesis [Lettres 1810, Tome 12: 155]. This interest persists into the secular history of astronomy produced by non-Jesuit French savants, and is possibly the signature of the 18th century fascination with the origin of the universe, the commencement of terrestrial time. In astronomical terms, this preoccupation moves along a fluid boundary between the scriptural and the scientific, and is reflected in the second preoccupation of the 18th century mind that is articulated even within the archive of French Jesuit science, and this has to do with chronology.

This engagement with chronology is not to be disassociated from traditional cosmology. For if chronology dealt with the unfolding of time, it temporally situated the unfurling of human history. For those nurtured in Catholic doctrine, human time, like history, began after the Deluge. Consequently, the search for analogues of the Noahic Deluge figures in their reading of other scriptural traditions, as if the Deluge was a mythopoeic universal that informed our meditations on celestial time [Lettres 1810, Tome 12: 157]. In terms of the scientific interpretation of the Bible, as the history of science moved towards becoming a secular discipline, the Dispersion of Nations and the Deluge were to be dated. Hence these preoccupations were not specific to Antoine Gaubil for whom answering these questions required the study of the history of astronomy in China [Dieny 1995: 504], but of the Jesuits in India and the mental landscape of the 18th century scientific imagination, rooted both in history and the Bible.

EXPEDITION OF PERES PONS AND BOUDIER TO JAIPUR

Pere Pons arrived in India in 1726 and after spending a few years in Thanjavur was appointed superior of the French Mission in Bengal. Other than compiling a Sanskrit grammar, and a treatise on Sanskrit poetics that was sent to Europe, he visited Delhi and Jaipur with Pere Boudier, mentioned earlier, to make some astronomical observations [Bamboat 1933: 95]. We find an account of this in a note entitled 'Observations: Geographic Expedition Undertaken in 1734 by Jesuit Fathers During Their Voyage from Chandernagor to Delhi to Jaipur' in the Lettres Edifiantes [Lettres, 1810, 15:269-91]. [Lettres, 1810, 15:269-91]. [Lettres, 1781, 15:337-349] In fact, this is a report on the very observations mentioned earlier in our discussion on Gaubil. The report begins by pointing out that the raja of Amber, Sawai Jai Singh, a savant [learned person] in astronomy, for whom the Jesuits had undertaken this expedition, had a number of astronomers working for him [Lettres 1810. 15: 269]. Jai Singh had requested the superior general of the church at Chandernagore, Boudier, to send Jesuit fathers stationed at Chandernagore to make some observations; and so Pres Pons and Boudier set out for Delhi and Jaipur.

The motivations behind this expedition have been recorded by Eric Forbes [Forbes 1982].10 Jai Singh's first contact with European astronomy appeared to reinforce his conviction that his large masonry observatories yielded more accurate results than iron astrolabes and sextants. He failed initially to appreciate the point that the source of his error was a faulty theoretical basis for computing lunar and planetary motions adopted by La Hire. In his letter to Pere Boudier, Jai Singh informed the former that he recognised this failing on mastering La Hire's book, and then wished to investigate whether other tables existed, and if so its underlying theoretical principles [Forbes 1982: 238]. And while Boudier was a "skilled telescopic observer", he was not equipped to answer Jai Singh's queries [Forbes 1982: 238]. Peres Boudier and Pons agreed to undertake the 1,000 mile journey to Jaipur on January 6, 1734 in the hope that they could establish a Christian mission at Jaipur. They reached Jaipur nine months later, but were forced to return shortly on account of ill health. When they were not making their observations, Forbes writes, they spent their time trying to convince the local brahmins of "Indian astronomy's indebtedness to ancient Greek culture" [Forbes 1982: 240].

The Bracmanes cultivated almost every part of mathematics; algebra was not unknown to them: but astronomy, the end of which was astrology, was always the principal object of their mathematical studies, because the superstition of the great and the people made it more useful to them. They have several methods of astronomy. A Greek scholar, who, like Pythagoras, once traveled in India, having learned the sciences of the Bracmanas, taught them in his turn his method of astronomy; and in order that his disciples might make it a mystery to others, he left them in his work the Greek names of the planets, the signs of the zodiac, and several terms[???] like hora (twenty-fourth part of a day), Kendra (center), etc. I had this acquaintance at Dely, and it served me to make the astronomers of Raja Jaesing, who are in large numbers in the famous observatory which he had built in this capital, feel that formerly masters had come to them [from] Europe.[!!!]

When we arrived at Jaëpur, the prince, to convince himself of the truth of what I had advanced[???], wanted to know the etymology of these Greek words, which I gave him. I also learned from the Bracmanas of Hindustan, that the most esteemed of their authors had placed the sun at the center of the movements of Mercury and Venus. Raja Jaësing will be regarded in the centuries to come as the restorer of Indian astronomy. The tables of M. de la Hire, under the name of this Prince,[!!!] will be current everywhere in a few years.[!!!]

Letter From Father Pons, Missionary of the Company of Jesus, to Father Du Halde, of the same Company. At Careical, on the coast of Tanjaour; in the East Indies, November 23, 1740. From "Lettres Edifiantes Et Curieuses, Ecrites Des Missions Etrangeres", by Charles Le Gobien

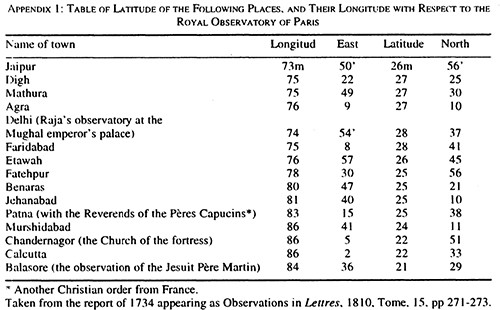

The document in the Lettres reports their observations of latitudes and longitudes of about 60 Indian towns and cities, the course of rivers they encountered during the course of their journey, the occultation of the Jovian satellites, and finally their observation regarding two eclipses that occurred in 1734. Appendix I provides a list of the latitudes and longitudes of some of the cities and towns obtained by them. However, there is an error of 35" in his latitude measurements of the observatory sites at Jaipur and Delhi [Sharma 1982: 347].

Throughout the 18th century one of the crucial obstacles for reconstructing the geography of India was the paucity of data on geographical latitudes and longitudes. The condition was further exacerbated by the non-standardisation of the Indian mile vis-a-vis the European mile, given the fact that the Indian mile varied from region to region of the country [Sen 1982: 1]. The Jesuits set about mapping this terrain. The method employed for determining these parameters required that the latitude and longitude of Chandernagor be known through a large number of astronomical observations. The route followed was carefully mapped as they travelled from one station to a neighbouring one. All along, the time was scrupulously noted with a time piece on hand, that was calibrated for the Paris meridian. The time spent was then compared with the speed of the vehicle. In addition, the detours along the route were carefully marked, and the speed of the air noted, a compass provided the directional readings [Lettres 1810, 15: 273]. This procedure was repeated all the way from Chandernagor to Kassimbazar to Patna to Agra to Delhi till they reached Jaipur. From Patna to Agra they could not use the compass since they were travelling by cart. Their observations had thus to be supplemented by surveying the course of the sun. Furthermore, throughout the voyage, as is done on sea, they had to correct their estimates by obtaining the latitudes of several locations [Lettres 1810. 15: 274]. No observations were made between Chandernagor and Kassimbazar since they covered this distance by the waterway, and the meandering path of the Ganges would have required that they spend a great deal of time to obtain a just estimate. In addition, they spent some time covering the distance at night [Lettres 1810, 15: 274.] On examining a number of naval maps, they found that Calcutta was marked more towards the east than Chandernagor, while in fact it was more to the west. Boudier and Pons found it surprising that the pilots sailing on the Ganges from one town to the next had not corrected this error. In addition, the report contains observations of the meridional heights of stars in 1734 taken from several towns [Lettres 1810, 15: 280-83].

At Kassimbazar, the French Jesuits carried out observations to calculate longitudes in 1734. These observations related to the immersion of the first satellite of Jupiter on January 30 at 15 hours, 41. On the same day, the passage of Beta Polaris was noted at 14 hours, 2 minutes and a fraction of a second [Lettres 1810, 15: 284-85]. At that moment a second star passed the vertical of the North Star at 16 hours 21 minutes and 30 seconds. From the passage of these two stars across the vertical of the North Star the time of the immersion of the satellite was obtained. During this period the time elapsed was 2 minutes and 50 seconds, and the hour of immersion was corrected to 15 hours 38 minutes and 30 seconds. At Fatehpour, the immersion of the first satellite on April 2 commenced at 13 hours 45 minutes and a fraction of a second. On the same day, the height of the tail of Leo towards the west was 46 degrees 9 minutes at 13 hours 50 minutes and a fraction of a second, and the height of the brightest star in Aquila towards the east, was 19 degrees 1 minute 30 seconds at 13 hours 57 minutes and about 10 seconds [Lettres 1810. 15: 285]. From the height of the two stars it was concluded that the time elapsed was 1 minute 26 seconds, the corrected hour of immersion was 13 hours 43 minutes and 34 seconds. Based on Pere Gaubil's observation of the time of immersion in Beijing on the April 11, 1734 [Lettres 1810. 15: 285], the difference between the meridian at Paris and Fatehpur was calculated at 5 hours and 13 minutes. This could be calculated differently. At a known time, the interval between the immersion on April 2 and 11, was 8 degrees 20 hours and 25 minutes, that could be subtracted from the time of observation at Beijing. On April 2, 16 hours 6 minutes and 57 seconds was the time of immersion at Beijing. But at Fatehpur it was observed at 13 hours 43 minutes 34 seconds. This gives a difference of 2 hours 23 minutes and 23 seconds, that must be subtracted from the longitude of Beijing, which was 7 hours 36 minutes: The difference between the meridians at Paris and Fatehpur was 5 hours 12 minutes 37 seconds or 5 hours 13 minutes [Lettres 1810, 15: 286]. A similar exercise was carried out in the case of Agra [Lettres 1810 15: 287]. Gaubil responded to the longitude measurements based on the observations of the occultation of the Jovian satellites, pointing out the errors in Boudier's calculations and that Boudier was unaware of stellar aberration [Gaubil, cited in Sharma. 1982: 347]. However, in the case of Delhi a solar eclipse that occurred on May 3, 1734 was used to obtain the longitude. The eclipse commenced at 3 hours 57 minutes and 11 seconds, but it was difficult to decide the end of the eclipse since the sky was cloudy. The corrected time for the eclipse was 3 hours 59 minutes and 59 seconds and finished at 5 hours 58 minutes and 3 seconds [Lettres 1810. 15: 268]. In a letter Pere Gaubil had mentioned that the Swedish astronomer Celsius had observed the end of this eclipse at Rome at 11 hours 52 minutes and 1 second. Using the method developed by La Hire, the eclipse commenced at Delhi, when the time in Rome was 11 hours 40 minutes and 5 seconds in the morning, and finished at 1 hour 39 minutes 40 seconds in the afternoon. This gives the difference between the meridians at Rome and Delhi as 4 hours 19 minutes and 4 seconds for the commencement of the eclipse and 4 hours 18 minutes and 18 seconds for the end of the eclipse. These differ by 46 seconds, half of which is 23 seconds. Adding this to the smaller of the two figures, we get the mean difference of 4 hours 18 minutes and 41 seconds, to which we add the difference between the meridians of Rome and Paris, which is 41 minutes and 20 seconds. Thus the difference between the meridians of Paris and Delhi is 5 hours and 1 second [Lettres 181-0, 15: 288].

On December 1, 1732 there was a total immersion of the moon at 22 'gharis' (the Indian unit ghari = 24 minutes, and each ghari = 60 'palas' ) 7 'pols' after sun set was observed at Jaipur. The emersion commenced at 26 gharis 13 pols and a half after sun set. Thus the middle of the eclipse was at 9 hours 41 minutes 24 seconds after the sun set. In their calculation the brahmins had not taken account of the effects of refraction, and the fact that the sun set at 5 hours 12 minutes 48 seconds, consequently the middle of the eclipse was at 14 hours 54 minutes 12 seconds [Lettres 1810. 15: 289]. According to Cassini's observation at the Paris Observatory, the middle of the eclipse was 9 hours 58 minutes 38 seconds. Hence, the difference between the meridians of Paris and Jaipur was 4 hours 55 minutes 34 seconds [Lettres 1810. 15: 290]. While Gaubil had made his observations of the satellite of Jupiter using a 20-foot focal length telescope, the Jesuits during their expedition used one that was a refracting telescope of focal length 17-feet [Lettres 1810. 15: 290].

Perusing these records, we recognise firstly the importance and authority of Gaubil among the Jesuit astronomers in India, for he appeared to be providing them the numbers that they considered standard, and thus aided their calibration. It was Gaubil who forwarded their results to Cassini, and thus the latter was the final authority certifying the results of the expedition. Secondly, the study of the motion of the stars and the planets, enabled the savants, through the Jesuits to map the co-ordinates of the globe, symbolically weaving Paris, Rome, Delhi, Jaipur and Beijing into the new fabric of modern science of which the Jesuits were the prominent cultural vectors, and subsequently the agents of cultural imperialism.