Part 2 of 2

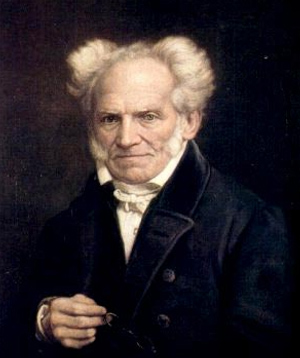

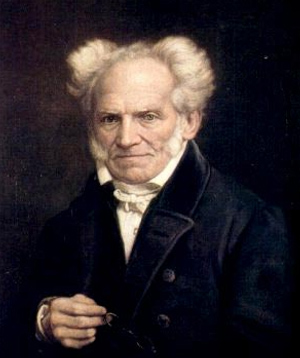

Reception in the West German 19th century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, impressed by the Upanishads, called the texts "the production of the highest human wisdom".

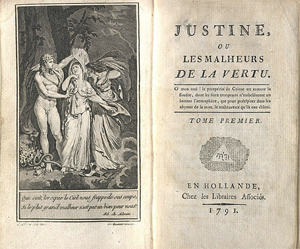

German 19th century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, impressed by the Upanishads, called the texts "the production of the highest human wisdom".The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer read the Latin translation and praised the Upanishads in his main work,

The World as Will and Representation (1819), as well as in his

Parerga and Paralipomena (1851).[205] He found his own philosophy was in accord with the Upanishads, which taught that the individual is a manifestation of the one basis of reality. For Schopenhauer, that fundamentally real underlying unity is what we know in ourselves as "will". Schopenhauer used to keep a copy of the Latin Oupnekhet by his side and commented,

It has been the solace of my life, it will be the solace of my death.[206]

Another German philosopher, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, praised the ideas in the Upanishads,[207] as did others.[208] In the United States, the group known as the Transcendentalists were influenced by the German idealists. Americans, such as Emerson and Thoreau embraced Schelling's interpretation of Kant's Transcendental idealism, as well as his celebration of the romantic, exotic, mystical aspect of the Upanishads. As a result of the influence of these writers, the Upanishads gained renown in Western countries.[209]

The poet T. S. Eliot, inspired by his reading of the Upanishads, based the final portion of his famous poem The Waste Land (1922) upon one of its verses.[210] According to Eknath Easwaran, the Upanishads are snapshots of towering peaks of consciousness.[211]

Juan Mascaró, a professor at the University of Barcelona and a translator of the Upanishads, states that the Upanishads represents for the Hindu approximately what the New Testament represents for the Christian, and that the message of the Upanishads can be summarized in the words, "the kingdom of God is within you".[212]

Paul Deussen in his review of the Upanishads, states that the texts emphasize Brahman-Atman as something that can be experienced, but not defined.[213] This view of the soul and self are similar, states Deussen, to those found in the dialogues of Plato and elsewhere. The Upanishads insisted on oneness of soul, excluded all plurality, and therefore, all proximity in space, all succession in time, all interdependence as cause and effect, and all opposition as subject and object.[213] Max Müller, in his review of the Upanishads, summarizes the lack of systematic philosophy and the central theme in the Upanishads as follows,

There is not what could be called a philosophical system in these Upanishads. They are, in the true sense of the word, guesses at truth, frequently contradicting each other, yet all tending in one direction. The key-note of the old Upanishads is "know thyself," but with a much deeper meaning than that of the γνῶθι σεαυτόν of the Delphic Oracle. The "know thyself" of the Upanishads means, know thy true self, that which underlines thine Ego, and find it and know it in the highest, the eternal Self, the One without a second, which underlies the whole world.

— Max Müller[14]

See also• Hinduism portal

• 100 Most Influential Books Ever Written

• Bhagavad Gita

• Hinduism

• Prasthanatrayi

• Mukhya Upanishads

Notes1. The shared concepts include rebirth, samsara, karma, meditation, renunciation and moksha.[4]

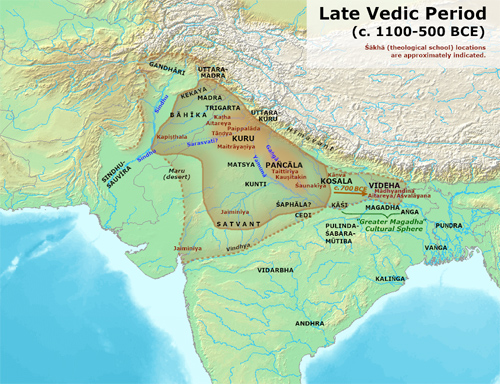

2. The Upanishadic, Buddhist and Jain renunciation traditions form parallel traditions, which share some common concepts and interests. While Kuru-Panchala, at the central Ganges Plain, formed the center of the early Upanishadic tradition, Kosala-Magadha at the central Ganges Plain formed the center of the other shramanic traditions.[5]

3. Advaita Vedanta, summarized by Shankara (788–820), advances a non-dualistic (a-dvaita) interpretation of the Upanishads."[16]

4. "These Upanishadic ideas are developed into Advaita monism. Brahman's unity comes to be taken to mean that appearances of individualities.[17]

5. "The doctrine of advaita (non dualism) has its origin in the Upanishads."

6. The pre-Buddhist Upanishads are: Brihadaranyaka, Chandogya, Kaushitaki, Aitareya, and Taittiriya Upanishads.[21]

7. These are believed to pre-date Gautam Buddha (c. 500 BCE)[68]

8. The Muktika manuscript found in colonial era Calcutta is the usual default, but other recensions exist.

9. Some scholars list ten as principal, while most consider twelve or thirteen as principal mukhya Upanishads.[82][83][84]

10. Parmeshwaranand classifies Maitrayani with Samaveda, most scholars with Krishna Yajurveda[79][90]

11. Oliville: "In this Introduction I have avoided speaking of 'the philosophy of the upanishads', a common feature of most introductions to their translations. These documents were composed over several centuries and in various regions, and it is futile to try to discover a single doctrine or philosophy in them."[95]

12. According to Collins, the breakdown of the Vedic cults is more obscured by retrospective ideology than any other period in Indian history. It is commonly assumed that the dominant philosophy now became an idealist monism, the identification of atman (self) and Brahman (Spirit), and that this mysticism was believed to provide a way to transcend rebirths on the wheel of karma. This is far from an accurate picture of what we read in the Upanishads. It has become traditional to view the Upanishads through the lens of Shankara's Advaita interpretation. This imposes the philosophical revolution of about 700 C.E. upon a very different situation 1,000 to 1,500 years earlier. Shankara picked out monist and idealist themes from a much wider philosophical lineup.[154]

13. For instances of Platonic pluralism in the early Upanishads see Randall.[185]

References1. "Upanishad". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

2. Wendy Doniger (1990), Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism, 1st Edition, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226618470, pages 2-3; Quote: "The Upanishads supply the basis of later Hindu philosophy; they are widely known and quoted by most well-educated Hindus, and their central ideas have also become a part of the spiritual arsenal of rank-and-file Hindus."

3. Wiman Dissanayake (1993), Self as Body in Asian Theory and Practice (Editors: Thomas P. Kasulis et al), State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791410806, page 39; Quote: "The Upanishads form the foundations of Hindu philosophical thought and the central theme of the Upanishads is the identity of Atman and Brahman, or the inner self and the cosmic self.";

Michael McDowell and Nathan Brown (2009), World Religions, Penguin, ISBN 978-1592578467, pages 208-210

4. Olivelle 1998, pp. xx-xxiv.

5. Samuel 2010.

6. Gavin Flood (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521438780, pp. 35–39

7. A Bhattacharya (2006), Hindu Dharma: Introduction to Scriptures and Theology, ISBN 978-0595384556, pp. 8–14; George M. Williams (2003), Handbook of Hindu Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195332612, p. 285

8. Jan Gonda (1975), Vedic Literature: (Saṃhitās and Brāhmaṇas), Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447016032

9. Patrick Olivelle 1998, pp. 3-4.

10. Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanisads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195352429, page 3; Quote: "Even though theoretically the whole of vedic corpus is accepted as revealed truth [shruti], in reality it is the Upanishads that have continued to influence the life and thought of the various religious traditions that we have come to call Hindu. Upanishads are the scriptures par excellence of Hinduism".

11. Max Müller, The Upanishads, Part 1, Oxford University Press, page LXXXVI footnote 1

12. Mahadevan 1956, p. 59.

13. PT Raju (1985), Structural Depths of Indian Thought, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0887061394, pages 35-36

14. WD Strappini, The Upanishads, p. 258, at Google Books, The Month and Catholic Review, Vol. 23, Issue 42

15. Ranade 1926, p. 205.

16. Cornille 1992, p. 12.

17. Phillips 1995, p. 10.

18. Stephen Phillips (2009), Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231144858, pages 25-29 and Chapter 1

19. E Easwaran (2007), The Upanishads, ISBN 978-1586380212, pages 298-299

20. Mahadevan 1956, p. 56.

21. Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, pages 12-14

22. King 1995, p. 52.

23. Olivelle 1992, pp. 5, 8–9.

24. Flood 1996, p. 96.

25. Ranade 1926, p. 12.

26. Varghese 2008, p. 101.

27. Clarke, John James (1997). Oriental Enlightenment: The Encounter Between Asian and Western Thought. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-415-13376-0.

28. Deussen 2010, p. 42, Quote: "Here we have to do with the Upanishads, and the world-wide historical significance of these documents cannot, in our judgement, be more clearly indicated than by showing how the deep fundamental conception of Plato and Kant was precisely that which already formed the basis of Upanishad teaching"..

29. Lawrence Hatab (1982). R. Baine Harris (ed.). Neoplatonism and Indian Thought. State University of New York Press. pp. 31–38. ISBN 978-0-87395-546-1.;

Paulos Gregorios (2002). Neoplatonism and Indian Philosophy. State University of New York Press. pp. 71–79, 190–192, 210–214. ISBN 978-0-7914-5274-5.

30. Ben-Ami Scharfstein (1998). A Comparative History of World Philosophy: From the Upanishads to Kant. State University of New York Press. pp. 62–74. ISBN 978-0-7914-3683-7.

31. "Upanishad". Online Etymology Dictionary.

32. Jones, Constance (2007). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 472. ISBN 978-0816073368.

33. Monier-Williams, p. 201.

34. Max Müller, Chandogya Upanishad 1.13.4, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 22

35. Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 85

36. Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 1.13.4, Oxford University Press, page 190

37. Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 185

38. motivation stories on upanishad

39. S Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanishads George Allen & Co., 1951, pages 22, Reprinted as ISBN 978-8172231248

40. Vaman Shivaram Apte, The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary Archived 15 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, see apauruSeya

41. D Sharma, Classical Indian Philosophy: A Reader, Columbia University Press, ISBN, pages 196-197

42. Jan Westerhoff (2009), Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195384963, page 290

43. Warren Lee Todd (2013), The Ethics of Śaṅkara and Śāntideva: A Selfless Response to an Illusory World, ISBN 978-1409466819, page 128

44. Hartmut Scharfe (2002), Handbook of Oriental Studies, BRILL Academic, ISBN 978-9004125568, pages 13-14

45. Mahadevan 1956, pp. 59-60.

46. Ellison Findly (1999), Women and the Arahant Issue in Early Pali Literature, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, Vol. 15, No. 1, pages 57-76

47. Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 301-304

48. For example, see: Kaushitaki Upanishad Robert Hume (Translator), Oxford University Press, page 306 footnote 2

49. Max Müller, The Upanishads, p. PR72, at Google Books, Oxford University Press, page LXXII

50. Patrick Olivelle (1998), Unfaithful Transmitters, Journal of Indian Philosophy, April 1998, Volume 26, Issue 2, pages 173-187;

Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, pages 583-640

51. WD Whitney, The Upanishads and Their Latest Translation, The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 7, No. 1, pages 1-26;

F Rusza (2010), The authorlessness of the philosophical sūtras, Acta Orientalia, Volume 63, Number 4, pages 427-442

52. Mark Juergensmeyer et al. (2011), Encyclopedia of Global Religion, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-0761927297, page 1122

53. Olivelle 1998, pp. 12-13.

54. Olivelle 1998, p. xxxvi.

55. Patrick Olivelle, Upanishads, Encyclopædia Britannica

56. Olivelle 1998, p. xxxvii.

57. Olivelle 1998, p. xxxviii.

58. Olivelle 1998, p. xxxix.

59. Deussen 1908, pp. 35–36.

60. Tripathy 2010, p. 84.

61. Sen 1937, p. 19.

62. Ayyangar, T. R. Srinivasa (1941). The Samanya-Vedanta Upanisads. Jain Publishing (Reprint 2007). ISBN 978-0895819833. OCLC 27193914.

63. Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 556-568.

64. Holdrege 1995, pp. 426.

65. Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes. BRILL Academic. pp. 112–120. ISBN 978-9004107588.

66. Ayyangar, TRS (1953). Saiva Upanisads. Jain Publishing Co. (Reprint 2007). pp. 194–196. ISBN 978-0895819819.

67. M. Fujii, On the formation and transmission of the JUB, Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora 2, 1997

68. Olivelle 1998, pp. 3–4.

69. Ranade 1926, p. 61.

70. Joshi 1994, pp. 90–92.

71. Heehs 2002, p. 85.

72. Rinehart 2004, p. 17.

73. Singh 2002, pp. 3–4.

74. Schrader & Adyar Library 1908, p. v.

75. Olivelle 1998, pp. xxxii-xxxiii.

76. Paul Deussen (1966), The Philosophy of the Upanishads, Dover, ISBN 978-0486216164, pages 283-296; for an example, see Garbha Upanishad

77. Patrick Olivelle (1992), The Samnyasa Upanisads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195070453, pages 1-12, 98-100; for an example, see Bhikshuka Upanishad

78. Brooks 1990, pp. 13–14.

79. Parmeshwaranand 2000, pp. 404–406.

80. Paul Deussen (2010 Reprint), Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814691, pages 566-568

81. Peter Heehs (2002), Indian Religions, New York University Press, ISBN 978-0814736500, pages 60-88

82. Robert C Neville (2000), Ultimate Realities, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0791447765, page 319

83. Stephen Phillips (2009), Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231144858, pages 28-29

84. Olivelle 1998, p. xxiii.

85. Patrick Olivelle (1992), The Samnyasa Upanisads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195070453, pages x-xi, 5

86. The Yoga Upanishads TR Srinivasa Ayyangar (Translator), SS Sastri (Editor), Adyar Library

87. AM Sastri, The Śākta Upaniṣads, with the commentary of Śrī Upaniṣad-Brahma-Yogin, Adyar Library, OCLC 7475481

88. AM Sastri, The Vaishnava-upanishads: with the commentary of Sri Upanishad-brahma-yogin, Adyar Library, OCLC 83901261

89. AM Sastri, The Śaiva-Upanishads with the commentary of Sri Upanishad-Brahma-Yogin, Adyar Library, OCLC 863321204

90. Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 217-219

91. Prāṇāgnihotra is missing in some anthologies, included by Paul Deussen (2010 Reprint), Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814691, page 567

92. Atharvasiras is missing in some anthologies, included by Paul Deussen (2010 Reprint), Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814691, page 568

93. Glucklich 2008, p. 70.

94. Fields 2001, p. 26.

95. Olivelle 1998, p. 4.

96. S Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanishads George Allen & Co., 1951, pages 17-19, Reprinted as ISBN 978-8172231248

97. Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli, The Principal Upanishads, Indus / Harper Collins India; 5th edition (1994), ISBN 978-8172231248

98. S Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanishads George Allen & Co., 1951, pages 19-20, Reprinted as ISBN 978-8172231248

99. S Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanishads George Allen & Co., 1951, page 24, Reprinted as ISBN 978-8172231248

100. Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 114-115 with preface and footnotes;

Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 3.17, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 212-213

101. Henk Bodewitz (1999), Hindu Ahimsa, in Violence Denied (Editors: Jan E. M. Houben, et al), Brill, ISBN 978-9004113442, page 40

102. PV Kane, Samanya Dharma, History of Dharmasastra, Vol. 2, Part 1, page 5

103. Chatterjea, Tara. Knowledge and Freedom in Indian Philosophy. Oxford: Lexington Books. p. 148.

104. Tull, Herman W. The Vedic Origins of Karma: Cosmos as Man in Ancient Indian Myth and Ritual. SUNY Series in Hindu Studies. P. 28

105. Mahadevan 1956, p. 57.

106. Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 30-42;

107. Max Müller (1962), Manduka Upanishad, in The Upanishads - Part II, Oxford University Press, Reprinted as ISBN 978-0486209937, pages 30-33

108. Eduard Roer, Mundaka Upanishad[permanent dead link] Bibliotheca Indica, Vol. XV, No. 41 and 50, Asiatic Society of Bengal, pages 153-154

109. Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 331-333

110. "laid those fires" is a phrase in Vedic literature that implies yajna and related ancient religious rituals; see Maitri Upanishad - Sanskrit Text with English Translation[permanent dead link] EB Cowell (Translator), Cambridge University, Bibliotheca Indica, First Prapathaka

111. Max Müller, The Upanishads, Part 2, Maitrayana-Brahmana Upanishad, Oxford University Press, pages 287-288

112. Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pp. 412–414

113. Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pp. 428–429

114. Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 350-351

115. Paul Deussen, The Philosophy of Upanishads at Google Books, University of Kiel, T&T Clark, pages 342-355, 396-412

116. RC Mishra (2013), Moksha and the Hindu Worldview, Psychology & Developing Societies, Vol. 25, No. 1, pages 21-42

117. Mark B. Woodhouse (1978), Consciousness and Brahman-Atman, The Monist, Vol. 61, No. 1, Conceptions of the Self: East & West (JANUARY, 1978), pages 109-124

118. Jayatilleke 1963, p. 32.

119. Jayatilleke 1963, pp. 39.

120. Mackenzie 2012.

121. James Lochtefeld, Brahman, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931798, page 122

122. [a]Richard King (1995), Early Advaita Vedanta and Buddhism, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791425138, page 64, Quote: "Atman as the innermost essence or soul of man, and Brahman as the innermost essence and support of the universe. (...) Thus we can see in the Upanishads, a tendency towards a convergence of microcosm and macrocosm, culminating in the equating of Atman with Brahman".

[ b] Chad Meister (2010), The Oxford Handbook of Religious Diversity, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195340136, page 63; Quote: "Even though Buddhism explicitly rejected the Hindu ideas of Atman ("soul") and Brahman, Hinduism treats Sakyamuni Buddha as one of the ten avatars of Vishnu."

[c] David Lorenzen (2004), The Hindu World (Editors: Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby), Routledge, ISBN 0-415215277, pages 208-209, Quote: "Advaita and nirguni movements, on the other hand, stress an interior mysticism in which the devotee seeks to discover the identity of individual soul (atman) with the universal ground of being (brahman) or to find god within himself".

123. PT Raju (2006), Idealistic Thought of India, Routledge, ISBN 978-1406732627, page 426 and Conclusion chapter part XII

124. Mariasusai Dhavamony (2002), Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Theological Soundings and Perspectives, Rodopi Press, ISBN 978-9042015104, pages 43-44

125. For dualism school of Hinduism, see: Francis X. Clooney (2010), Hindu God, Christian God: How Reason Helps Break Down the Boundaries between Religions, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199738724, pages 51-58, 111-115;

For monist school of Hinduism, see: B Martinez-Bedard (2006), Types of Causes in Aristotle and Sankara, Thesis - Department of Religious Studies (Advisors: Kathryn McClymond and Sandra Dwyer), Georgia State University, pages 18-35

126. Jeffrey Brodd (2009), World Religions: A Voyage of Discovery, Saint Mary's Press, ISBN 978-0884899976, pages 43-47

127. Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 91

128. [a] Atman, Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press (2012), Quote: "1. real self of the individual; 2. a person's soul";

[ b] John Bowker (2000), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0192800947, See entry for Atman;

[c] WJ Johnson (2009), A Dictionary of Hinduism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0198610250, See entry for Atman (self).

129. Soul is synonymous with self in translations of ancient texts of Hindu philosophy

130. Alice Bailey (1973), The Soul and Its Mechanism, ISBN 978-0853301158, pages 82-83

131. Eknath Easwaran (2007), The Upanishads, Nilgiri Press, ISBN 978-1586380212, pages 38-39, 318-320

132. John Koller (2012), Shankara, in Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion, (Editors: Chad Meister, Paul Copan), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415782944, pages 99-102

133. Paul Deussen, The Philosophy of the Upanishads at Google Books, Dover Publications, pages 86-111, 182-212

134. Nakamura (1990), A History of Early Vedanta Philosophy, p.500. Motilall Banarsidas

135. Mahadevan 1956, pp. 62-63.

136. Paul Deussen, The Philosophy of the Upanishads, p. 161, at Google Books, pages 161, 240-254

137. Ben-Ami Scharfstein (1998), A Comparative History of World Philosophy: From the Upanishads to Kant, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791436844, page 376

138. H.M. Vroom (1996), No Other Gods, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 978-0802840974, page 57

139. Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty (1986), Dreams, Illusion, and Other Realities, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226618555, page 119

140. Archibald Edward Gough (2001), The Philosophy of the Upanishads and Ancient Indian Metaphysics, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415245227, pages 47-48

141. Teun Goudriaan (2008), Maya: Divine And Human, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120823891, pages 1-17

142. KN Aiyar (Translator, 1914), Sarvasara Upanishad, in Thirty Minor Upanishads, page 17, OCLC 6347863

143. Adi Shankara, Commentary on Taittiriya Upanishad at Google Books, SS Sastri (Translator), Harvard University Archives, pages 191-198

144. Radhakrishnan 1956, p. 272.

145. Raju 1992, p. 176-177.

146. Raju 1992, p. 177.

147. Ranade 1926, pp. 179–182.

148. Mahadevan 1956, p. 63.

149. Encyclopædia Britannica.

150. Radhakrishnan 1956, p. 273.

151. King 1999, p. 221.

152. Nakamura 2004, p. 31.

153. King 1999, p. 219.

154. Collins 2000, p. 195.

155. Radhakrishnan 1956, p. 284.

156. John Koller (2012), Shankara in Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion (Editors: Chad Meister, Paul Copan), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415782944, pages 99-108

157. Edward Roer (translator), Shankara's Introduction, p. 3, at Google Books to Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad at pages 3-4; Quote - "(...) Lokayatikas and Bauddhas who assert that the soul does not exist. There are four sects among the followers of Buddha: 1. Madhyamicas who maintain all is void; 2. Yogacharas, who assert except sensation and intelligence all else is void; 3. Sautranticas, who affirm actual existence of external objects no less than of internal sensations; 4. Vaibhashikas, who agree with later (Sautranticas) except that they contend for immediate apprehension of exterior objects through images or forms represented to the intellect."

158. Edward Roer (Translator), Shankara's Introduction, p. 3, at Google Books to Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad at page 3, OCLC 19373677

159. KN Jayatilleke (2010), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge, ISBN 978-8120806191, pages 246-249, from note 385 onwards;

Steven Collins (1994), Religion and Practical Reason (Editors: Frank Reynolds, David Tracy), State Univ of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791422175, page 64; Quote: "Central to Buddhist soteriology is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the [Buddhist] doctrine that human beings have no soul, no self, no unchanging essence.";

Edward Roer (Translator), Shankara's Introduction, p. 2, at Google Books, pages 2-4

Katie Javanaud (2013), Is The Buddhist 'No-Self' Doctrine Compatible With Pursuing Nirvana?, Philosophy Now;

John C. Plott et al (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Axial Age, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120801585, page 63, Quote: "The Buddhist schools reject any Ātman concept. As we have already observed, this is the basic and ineradicable distinction between Hinduism and Buddhism".

160. Panikkar 2001, p. 669.

161. Panikkar 2001, pp. 725–727.

162. Panikkar 2001, pp. 747–750.

163. Panikkar 2001, pp. 697–701.

164. Olivelle 1998.

165. Klostermaier 2007, pp. 361–363.

166. Chari 1956, p. 305.

167. Stafford Betty (2010), Dvaita, Advaita, and Viśiṣṭādvaita: Contrasting Views of Mokṣa, Asian Philosophy, Vol. 20, No. 2, pages 215-224, doi:10.1080/09552367.2010.484955

168. Jeaneane D. Fowler (2002). Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 298–299, 320–321, 331 with notes. ISBN 978-1-898723-93-6.

169. William M. Indich (1995). Consciousness in Advaita Vedanta. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–2, 97–102. ISBN 978-81-208-1251-2.

170. Bruce M. Sullivan (2001). The A to Z of Hinduism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-8108-4070-6.

171. Stafford Betty (2010), Dvaita, Advaita, and Viśiṣṭādvaita: Contrasting Views of Mokṣa, Asian Philosophy: An International Journal of the Philosophical Traditions of the East, Volume 20, Issue 2, pages 215-224

172. Edward Craig (2000), Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415223645, pages 517-518

173. Sharma, Chandradhar (1994). A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 373–374. ISBN 81-208-0365-5.

174. J.A.B. van Buitenen (2008), Ramanuja - Hindu theologian and Philosopher, Encyclopædia Britannica

175. Jon Paul Sydnor (2012). Ramanuja and Schleiermacher: Toward a Constructive Comparative Theology. Casemate. pp. 20–22 with footnote 32. ISBN 978-0227680247.

176. Joseph P. Schultz (1981). Judaism and the Gentile Faiths: Comparative Studies in Religion. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 81–84. ISBN 978-0-8386-1707-6.

177. Raghavendrachar 1956, p. 322.

178. Jeaneane D. Fowler (2002). Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 978-1-898723-93-6.

179. Stoker, Valerie (2011). "Madhva (1238-1317)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

180. Bryant, Edwin (2007). Krishna : A Sourcebook (Chapter 15 by Deepak Sarma). Oxford University Press. pp. 358–359. ISBN 978-0195148923.

181. Sharma, Chandradhar (1994). A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 374–375. ISBN 81-208-0365-5.

182. Bryant, Edwin (2007). Krishna : A Sourcebook (Chapter 15 by Deepak Sarma). Oxford University Press. pp. 361–362. ISBN 978-0195148923.

183. Chousalkar 1986, pp. 130-134.

184. Wadia 1956, p. 64-65.

185. Collins 2000, pp. 197–198.

186. Urwick 1920.

187. Keith 2007, pp. 602-603.

188. RC Mishra (2013), Moksha and the Hindu Worldview, Psychology & Developing Societies, Vol. 25, No. 1, pages 21-42; Chousalkar, Ashok (1986), Social and Political Implications of Concepts Of Justice And Dharma, pages 130-134

189. Sharma 1985, p. 20.

190. Müller 1900, p. lvii.

191. Müller 1899, p. 204.

192. Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 558-59.

193. Müller 1900, p. lviii.

194. Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 558-559.

195. Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 915-916.

196. See Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1858), Essays on the religion and philosophy of the Hindus. London: Williams and Norgate. In this volume, see chapter 1 (pp. 1–69), On the Vedas, or Sacred Writings of the Hindus, reprinted from Colebrooke's Asiatic Researches, Calcutta: 1805, Vol 8, pp. 369–476. A translation of the Aitareya Upanishad appears in pages 26–30 of this chapter.

197. Zastoupil, L (2010). Rammohun Roy and the Making of Victorian Britain, By Lynn Zastoupil. ISBN 9780230111493. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

198. "The Upanishads, Part 1, by Max Müller".

199. Hume, Robert Ernest (1921), The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press

200. Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997.

201. Radhakrishnan, Sarvapalli (1953), The Principal Upanishads, New Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers (1994 Reprint), ISBN 81-7223-124-5

202. Olivelle 1992.

203. "AAS SAC A.K. Ramanujan Book Prize for Translation". Association of Asian

204. "William Butler Yeats papers". library.udel.edu. University of Delaware. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

205. Schopenhauer & Payne 2000, p. 395.

206. Schopenhauer & Payne 2000, p. 397.

207. Herman Wayne Tull (1989). The Vedic Origins of Karma: Cosmos as Man in Ancient Indian Myth and Ritual. State University of New York Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-7914-0094-4.

208. Klaus G. Witz (1998). The Supreme Wisdom of the Upaniṣads: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 35–44. ISBN 978-81-208-1573-5.

209. Versluis 1993, pp. 69, 76, 95. 106–110.

210. Eliot 1963.

211. Easwaran 2007, p. 9.

212. Juan Mascaró, The Upanishads, Penguin Classics, ISBN 978-0140441635, page 7, 146, cover

213. Paul Deussen, The Philosophy of the Upanishads University of Kiel, T&T Clark, pages 150-179

Sources• Brooks, Douglas Renfrew (1990), The Secret of the Three Cities: An Introduction to Hindu Shakta Tantrism, The University of Chicago Press

• Brown, Rev. George William (1922), Missionary review of the world, 45, Funk & Wagnalls

• Deussen, Paul; Bedekar, V.M. (tr.); Palsule (tr.), G.B. (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1467-7.

• Deussen, P. (2010), The Philosophy of the Upanishads, Cosimo, ISBN 978-1-61640-239-6

• Chari, P. N. Srinivasa (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western

• Chousalkar, Ashok (1986), Social and Political Implications of Concepts Of Justice And Dharma, Mittal Publications

• Collins, Randall (2000), The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-00187-7

• Cornille, Catherine (1992), The Guru in Indian Catholicism: Ambiguity Or Opportunity of Inculturation, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8028-0566-9

• Deussen, Paul (1908), The philosophy of the Upanishads, Alfred Shenington Geden, T. & T. Clark, ISBN 0-7661-5470-X

• Easwaran, Eknath (2007), The Upanishads, Nilgiri Press, ISBN 978-1-58638-021-2

• Eliot, T. S. (1963), Collected Poems, 1909-1962, New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, ISBN 0-15-118978-1

• Encyclopædia Britannica, Advaita, retrieved 10 August 2010

• Farquhar, John Nicol (1920). An outline of the religious literature of India. H. Milford, Oxford university press. ISBN 81-208-2086-X.

• Fields, Gregory P (2001), Religious Therapeutics: Body and Health in Yoga, Āyurveda, and Tantra, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-4916-5

• Flood, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521438780

• Glucklich, Ariel (2008), The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-531405-2

• Heehs, Peter (2002), Indian religions: a historical reader of spiritual expression and experience, NYU Press, ISBN 978-0-8147-3650-0

• Holdrege, Barbara A. (1995), Veda and Torah, Albany: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1639-9

• Jayatilleke, K.N. (1963), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge (PDF) (1st ed.), London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

• Joshi, Kireet (1994), The Veda and Indian culture: an introductory essay, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0889-8

• Keith, Arthur Berriedale (2007). The Religion and Philosophy of the Veda and Upanishads. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-0644-3.

• King, Richard (1999), Indian philosophy: an introduction to Hindu and Buddhist thought, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0-87840-756-1

• King, Richard (1995), Early Advaita Vedānta and Buddhism: the Mahāyāna context of the Gauḍapādīya-kārikā, Gauḍapāda, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2513-8

• Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2007), A survey of Hinduism, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-585-04507-8

• Lanman, Charles R (1897), The Outlook, 56, Outlook Co.

• Lal, Mohan (1992), Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: sasay to zorgot, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 978-81-260-1221-3

• Mackenzie, Matthew (2012), "Luminosity, Subjectivity, and Temporality: An Examination of Buddhist and Advaita views of Consciousness", in Kuznetsova, Irina; Ganeri, Jonardon; Ram-Prasad, Chakravarthi (eds.), Hindu and Buddhist Ideas in Dialogue: Self and No-Self, Routledge

• Mahadevan, T. M. P (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

• Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, ISBN 0-8426-0286-0, retrieved 10 August 2010

• Müller, F. Max (1899), The science of language founded on lectures delivered at the royal institution in 1861 AND 1863, ISBN 0-404-11441-5

• Müller, Friedrich Max (1900), The Upanishads Sacred books of the East The Upanishads, Friedrich Max Müller, Oxford University Press

• Nakamura, Hajime (2004), A history of early Vedānta philosophy, 2, Trevor Leggett, Motilal Banarsidass

• Patrick Olivelle (1998). The Early Upanisads. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195124354.

• Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195070453.

• Olivelle, Patrick (1998), Upaniṣads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0192835765

• Panikkar, Raimundo (2001), The Vedic experience: Mantramañjarī : an anthology of the Vedas for modern man and contemporary celebration, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1280-2

• Parmeshwaranand, Swami (2000), Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Upanisads, Sarup & Sons, ISBN 978-81-7625-148-8

• Phillips, Stephen H. (1995), Classical Indian metaphysics: refutations of realism and the emergence of "new logic", Open Court Publishing, ISBN 978-81-208-1489-9, retrieved 24 October 2010

• Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

• Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

• Raghavendrachar, Vidvan H. N (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western

• Ranade, R. D. (1926), A constructive survey of Upanishadic philosophy, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan

• Rinehart, Robin (2004), Robin Rinehart (ed.), Contemporary Hinduism: ritual, culture, and practice, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8

• Schopenhauer, Arthur; Payne, E. F.J (2000), E. F. J. Payne (ed.), Parerga and paralipomena: short philosophical essays, Volume 2 of Parerga and Paralipomena, E. F. J. Payne, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-924221-4

• Schrödinger, Erwin (1992). What is life?. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42708-1.

• Schrader, Friedrich Otto; Adyar Library (1908), A descriptive catalogue of the Sanskrit manuscripts in the Adyar Library, Oriental Pub. Co

• Sen, Sris Chandra (1937), "Vedic literature and Upanishads", The Mystic Philosophy of the Upanishads, General Printers & Publishers

• Sharma, B. N. Krishnamurti (2000). A history of the Dvaita school of Vedānta and its literature: from the earliest beginnings to our own times. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-1575-9.

• Sharma, Shubhra (1985), Life in the Upanishads, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-202-4

• Singh, N.K (2002), Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, Anmol Publications PVT. LTD, ISBN 978-81-7488-168-7

• Slater, Thomas Ebenezer (1897), Studies in the Upanishads ATLA monograph preservation program, Christian Literature Society for India

• Smith, Huston (1995). The Illustrated World's Religions: A Guide to Our Wisdom Traditions. New York: Labyrinth Publishing. ISBN 0-06-067453-9.

• Tripathy, Preeti (2010), Indian religions: tradition, history and culture, Axis Publications, ISBN 978-93-80376-17-2

• Urwick, Edward Johns (1920), The message of Plato: a re-interpretation of the "Republic", Methuen & co. ltd, ISBN 9781136231162

• Varghese, Alexander P (2008), India : History, Religion, Vision And Contribution To The World, Volume 1, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 978-81-269-0903-2

• Versluis, Arthur (1993), American transcendentalism and Asian religions, Oxford University Press US, ISBN 978-0-19-507658-5

• Wadia, A.R. (1956), "Socrates, Plato and Aristotle", in Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, vol. II, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

• Raju, P. T. (1992), The Philosophical Traditions of India, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

Further reading• Edgerton, Franklin (1965). The Beginnings of Indian Philosophy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

• Embree, Ainslie T. (1966). The Hindu Tradition. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-71702-3.

• Hume, Robert Ernest. The Thirteen Principal Upanishads. Oxford University Press.

• Johnston, Charles (1898). From the Upanishads. Kshetra Books (Reprinted in 2014). ISBN 9781495946530.

• Müller, Max, translator, The Upaniṣads, Part I, New York: Dover Publications (Reprinted in 1962), ISBN 0-486-20992-X

• Müller, Max, translator, The Upaniṣads, Part II, New York: Dover Publications (Reprinted in 1962), ISBN 0-486-20993-8

• Radhakrishnan, Sarvapalli (1953). The Principal Upanishads. New Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers India (Reprinted in 1994). ISBN 81-7223-124-5.

External links• Complete set of 108 Upanishads, Manuscripts with the commentary of Brahma-Yogin, Adyar Library

• Upanishads, Sanskrit documents in various formats

• The Upaniṣads article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

• The Theory of 'Soul' in the Upanishads, T. W. Rhys Davids (1899)

• Spinozistic Substance and Upanishadic Self: A Comparative Study, M. S. Modak (1931)

• W. B. Yeats and the Upanishads, A. Davenport (1952)

• The Concept of Self in the Upanishads: An Alternative Interpretation, D. C. Mathur (1972)