Degrassis' Edition of the Consular and Triumphal Fasti*

by Lily Ross Taylor

Classical Philology, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Apr., 1950), pp. 84-95

Apr., 1950

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

[*In the preparation of this article I have depended, particularly for architectural details, on a joint paper written in 1945 by Professor L. B. Holland and me, but not published for reasons explained in the article. I was also aided by a discussion in the Forum which he and I and Professor Frank Brown had in July 1949 with Professor Degrassi, and with the Director of Antiquities of the Forum aind Palatine, Dr. Pietro Romanelli, and the architect Italo Gismondi. Professor Holland will publish a note elsewhere on the results of that discussion and of the investigation of the foundations of the Arch of Augustus carried out at that time. For suggestions on other points in the article I am under obligation to Professor Degrassi and also to my colleague Professor T. R. S. Broughton.]

A PLAN for a complete new publication of all Latin inscriptions of the classical period found in Italy was announced by the Union of Italian Academies twenty years ago. The publication was to provide full photographic reproductions such as are available only in the most recent issues of the Corpus of Latin Inscriptions. Of the volumes of this new Inscriptiones Italiae, numbered according to the Augustan regions of Italy, a few fascicles from certain sites have appeared --- from Volume I, Tibur (1936); from Volume IX, Augusta Bagiennorum and Pollentia (1948); from Volume X, Parentium (1934), Histria Septentrionalis (1936), Pola and Nesactium (1947); from Volume XI, Eporedia (1931), and Augusta Praetoria (1932). Further material from Volume X and from one or two other sites is now ready for publication, but there are no plans in prospect now for the completion of the whole project.

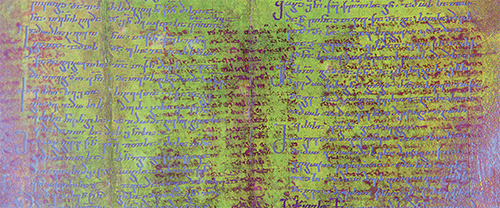

By far the most important and difficult material in the entire undertaking was presented by the consular and triumphal fasti, the calendars, and the elogia, first brought out in CIL, I by Mommsen and Henzen in 1863 and later published in a second edition by Mommsen and Huelsen in 1893. In later years there have been significant new discoveries, and there was a crying need for a new edition illustrated by photographs.

The publication of these important documents, assigned to Volume XIII of the Inscriptiones Italiae, was entrusted to Professor Attilio Degrassi, who had already prepared for the series a portion of the inscriptions of his native Istria (Parentium and Histria Septentrionalis). There could not have been a more fortunate choice of editor, for Degrassi is a remarkable epigraphist, trained in the traditions of the most extraordinary work of co-operative scholarship in the classical field, Mommsen's great Corpus inscriptionum Latinarum. Both at the University of Vienna and in the field Degrassi worked under one of Mommsen's ablest coadjutors, Eugen Bormann, editor of CIL, XI, and he has been able to combine the care and ingenuity that has characterized the best of Latin epigraphists with the modern methods made available through the resources of the Italian Academies.

Degrassi began his task in 1935. Not having a university appointment (which is to be regretted, for he ought to be training a new generation of epigraphists), he was able to put his entire time on the investigation. He read every stone himself and searched out every manuscript record of lost stones. He mastered the vast scholarly literature on the inscriptions. The elogia, increased in scope by the discoveries in the Forum of Augustus, came out in 1937. The work on the calendars is completed but still awaits publication. The fascicle dealing with consular and triumphal fasti, with which I am concerned in this paper, came out late in 1947. Fascicle is a very modest term for this large publication issued in two parts which should, for convenient use, be bound separately.1

The fascicle is beautifully printed on good paper, imported, Degrassi tells me, from the United States. The printer has done his difficult job well, though Degrassi states that in some particulars the art of printing inscriptions has declined. I remembered that many years ago Dessau had made a similar comment to me about the problem of printing CIL, XIII in Germany, and I asked Degrassi for an explanation. The difficulty, he says, is not with the printer's art but with the funds available for the printer's work.

There are excellent photographs of all the inscriptions and sometimes photographs of squeezes which show the letters more clearly than the stones do. There are also numerous drawings in the text and plates, a valuable adjunct to the photographs. The architectural drawings are in most cases the work of Dr. Guglielmo Gatti, architect and archaeologist, now Inspector of Antiquities in Rome. Other drawings are the work of Achilles Capizzano, Rosa Falconi, and Severino Brusa. These illustrations are supplemented by full information on measurements and character of the stone or marble used for the inscriptions-important details that were ignored in the earlier volumes of CIL.

The text, written in easy intelligible Latin, has full commentaries on all the inscriptions, with bibliography that is up to date until the beginning of the war and includes German and Italian publications after that date.2 The views of other scholars are considered fairly and dispassionately, and the conclusions are independent and worthy of the most careful consideration. I would note for instance the explanation (p. 142) of the omission of the praenomen of M.' Aemilius' grandfather. The material is arranged with remarkable understanding of the needs of the reader. One of the most valuable features of the volume is the new version of Mommsen's conspectus of the evidence for consuls under each year. In addition to the material from the stones, from the derivatives of the Fasti Capitolini, and from the historians, all of which was presented by Mommsen, there is a heading, alia testimonia, which gives, besides most of the available literary evidence, quotations from inscriptions, many of which have come to light since 1893.3

Of no less importance for the scholar are the indices that seem to have foreseen every need for which I have so often gone through CIL, I. In addition to lists of nomina [GT: appointment] and cognomina [GT: last names] there are both alphabetical and chronological lists (in which it is a pleasure to have B.C. dates given preference over a.u.c.) of chief magistrates, including consules suffecti [GT: the consuls were overpowered], of magistrates who died in office, who abdicated, who were vitio creati [GT: created by vice], of the various types of magistrates who triumphed, of dates of triumphs, and of contradictions between various sets of records.

Naturally the greatest interest attaches to the consular and triumphal lists inscribed under Augustus on a building in the Roman Forum. These lists, known from the fact that they are in the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitoline Hill as the Capitoline Fasti, far surpass in extent and significance any other inscribed list of magistrates. It is with Degrassi's view of the monument to which these Fasti belonged and with the date when they were inscribed that I am mainly concerned in this article. But before proceeding to the discussion I shall consider briefly other consular4 and triumphal fasti published by Degrassi.

Whereas in the second edition of CIL, I Mommsen and Huelsen included with the Capitoline Fasti seventeen other consular and triumphal lists, Degrasssi includes thirty-five. Not all of them are new, for he did not, like the editors of CIL, exclude from his volume post-Augustan records. But there is also a good deal of material both from new lists and from new fragments of old lists discovered since 1893. The most significant new records are the consular lists (and calendar) from Antium, painted on plaster, the Fasti Ostienses and the fasti set up in Rome by vicorum magistri of the Aventine [GT: the masters of the streets of the Aventine.]. The painted fasti of Antium, the only republican consular lists that we possess, are a valuable record of consuls and censors of many years in the period 164-84 B.C. Particularly on the censors they provide important new information. The Fasti Ostienses, a few fragments of which were known before 1893, now number forty-two fragments, (including the fragment in Degrassi's "Additamenta," pp. 571 f.), most of which have come to light in the excavations of Ostia during the last forty years. They cover large sections of the period from 49 B.C. to A.D. 160. These inscriptions are a mine of information for imperial chronology, particularly for the period from Domitian to Antoninus Pius. Degrassi has presented the first complete collection of the inscriptions accompanied by an admirable commentary. He is a master of imperial as well as of republican prosopography. The fasti from the Aventine have provided much new material on consules suffecti of the Augustan period.

Prosopography is an investigation of the common characteristics of a group of people, whose individual biographies may be largely untraceable. Research subjects are analysed by means of a collective study of their lives, in multiple career-line analysis. The discipline is considered to be one of the auxiliary sciences of history. -- Prosopography, by Wikipedia

There is also a new fragment of a triumphal list, a stone from Urbisalvia, which, joined to a small fragment already known, covers certain years between 195 and 158 B.C. This is an important document, for it proves that municipalities sometimes set up lists of triumphatores as well as lists of chief magistrates. With good reason Degrassi (pp. 339 f.) disputes the view of Moretti and Altheim, who attributed these lists to an earlier period than the Fasti Capitolini. The use of Greek marble in these records provides strong reason for believing that they are not earlier than Augustus.

Nor are Degrassi's new contributions confined to new monuments. He has a very interesting discussion (pp. 143 f.) of the marble fragments of the Fasti feriarum Latinarum [GT: Latin holiday fast] which were discovered in the precinct of Juppiter Latiaris on the Alban Mount. He argues against Henzen's reconstruction of the monument to which these fasti belonged, and presents his own tentative restoration. Noting that the fragment covering the years 27-22 differs in form of presentation from the fragments covering earlier years, he concludes that the monument had been inscribed before 27, but probably not long before that date. He also notes the differences between these fasti and the Fasti Capitolini.

To go back to the Fasti Capitolini, Degrassi's work has involved a thorough study of the seven new fragments that have come to light since 1893 and also of all the old fragments belonging to this, the most important record of consuls and triumphs. There are new readings of some importance, for instance under the years 279 and 265 in the consular fasti and under 437 and 291 in the triumphal lists.

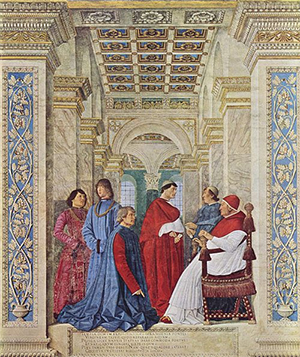

But the great discovery concerns the architectural character and the identification of the monument to which the Fasti belonged. The marble monument on which these lists were inscribed was found accidentally in 1546 somewhere between the temple of Antoninus and Faustina and the east side of the temple of Castor. It was discovered accidentally in 1546 in a search for marble to be used for lime. Cardinal Alexander Farnese heard about the inscribed fragments that were found, gathered together all of them that could be discovered, and had the site searched for additional stones. A decree of the Roman Consiglio of 1548, which Degrassi has found in the archives of the Campidoglio,5 charged the epigraphist Gentile Delphino and Tommaso Cavalieri with the arrangement of stones in the Palazzo dei Conservatori. In Degrassi's view Cavalieri was probably responsible for calling on Michelangelo, who designed the wall in which the fragments were placed. There were additional insertions of inscriptions in the wall after Carlo Fea in 1816-17 unearthed stones from both consular and triumphal fasti in an excavation beside the temple of Castor. Stones discovered later were placed in the Sala della Lupa, where the wall now is, or were stored in the magazzino of the Museum.

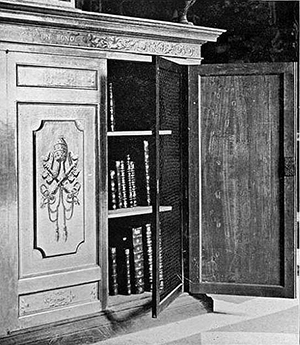

Through the co-operation of the Director of the Museum, Dr. Settimo Bocconi, Degrassi's work has resulted in a rearrangement of the material in the Museum. Stones from extraneous lists, erroneously inserted in the wall, have been removed and transferred to the Capitoline Museum.6 Various fragments discovered since 1816 have been placed in the wall, and the other existing fragments are all now collected in the room. Thus all the stones can be studied together.

It was a great gain for Degrassi's work that he was able for purposes of study to have certain fragments removed temporarily from the wall. The examination of these fragments, in which Gatti cooperated with Degrassi, has led to important results for the character of the monument.

It was recognized by epigraphists of the time that Michelangelo's wall did not represent the monument that was discovered in the Forum. Onofrio Panvinio makes it clear that four "tablets" of consular fasti were found, three in fragmentary state, but one, the third tablet, in a much better state of preservation. That third tablet, the lower part of which is intact in the central portion of Michelangelo's wall, consists of a central aedicula with lists inside it of chief magistrates of the years 292-154, and with flanking pilasters on which were inscribed the triumphatores from Romulus to the year 222. The fourth tablet also had flanking pilasters on which were inscribed the names of triumphatores through the year 19 B.C. Tablets one and two, with lists of kings, consuls, and chief magistrates from the beginning of the Roman state, were not flanked by inscribed pilasters.

The careful work of Degrassi and Gatti has shown that Huelsen's calculations on the distribution of the material in the four tablets were incorrect in many details.7 It is now clear that, contrary to the view of Huelsen, the four tablets were of equal height, and that all of them, and not simply the third and fourth, were enclosed aediculae.

Degrassi's important new discovery concerns the building to which the Fasti belonged. It was not the Regia but the triple Arch of Augustus, whose foundations are preserved beside the temple of Divus Julius at the northeast corner of the temple of Castor. The inscriptions were in the two lateral openings of the triple arch; the third and fourth tablets with their inscribed pilasters are assumed to have been in the opening next to the temple of Divus Julius, while the first and second tablet are assigned to the other opening which was always at least partly blocked by the temple of Castor. Degrassi's discovery was not made until after the volumes were in proof. The evidence, briefly stated in the text, is fully discussed in the Rendiconti della Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia, XXI (1945-46), pp. 57-104; in an article that follows Degrassi's (pp. 105-22), Gatti discusses the reconstruction of the Arch of Augustus.

The suggestion that the tablets were on an arch is not new. It goes back to the architect, Pirro Ligorio, who as early as 1553 described the monument as a Iano [?]. Ligorio, whose imagination was never limited by the evidence he had observed, restored a Janus Quadrifrons [?] (Degrassi, Rendiconti, Figs. 1 and 2) inscribed inside the openings and outside with consular and triumphal records and other lists suggested to him by his active mind.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the creation of epigraphic forgeries became more and more frequent. Well-known forgers, like Annio da Viterbo and Pirro Ligorio, produced thousands of false inscriptions, both on paper and on durable materials, like stone or metal...

In a letter written to the young Danish scholar Olaus Kellerman, in 1835, the great Italian Epigraphist Bartolomeo Borghesi, complimented on the former's intention of setting up a corpus of Latin inscriptions. In the first place, because such a work would eventually help scholars to get rid of thousands of impostures and forged texts, which were still circulating in their days. Kellerman died young, and his project was revived by Theodor Mommsen, who gave way to a new science, namely "Epigraphic Criticism." Mummson fully described this method in his proposal for a Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, which he addressed to the Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1847. A full paragraph of his text was devoted to the critique of authenticity. In Mommsen's view, there were three different kinds of epigraphic forgeries. 1) Those deceitfully produced by antique dealers, 2) those created by local scholars, usually just on paper, to celebrate their homeland, and 3) those fabricated by professional forgers, which were also the most difficult to detect. And this was the case of Ligorio, towards whom both Borghesi and Mommsen had developed a real aversion.

Mommsen put in place his principles in the addition of the Latin Inscriptions from the Kingdom of Naples, published in 1852. In his introduction to the work, which was dedicated to Borghesi, he developed his own set of rules for dealing with untrustworthy epigraphic documents. Mommsen's assumption was that inscriptions are, in the first place, fundamental documents for the study of the past. In his positivist view, history had to be an exact science. But in order to be so, it had to be written using objective and reliable primary sources. The latter included the text of Greek and Latin authors, but also, and perhaps above all, the text of ancient inscriptions which have come to us directly without the mediation of medieval copyists.

It is well worth reading the rules which Mommsen set in treating epigraphic forgeries, because after over 150 years, they're still very, very influential. So I will perhaps read them in English translation, but you have the original text in front of you.

The first I included in my corpus -- all the inscriptions -- the ones that I saw, and the ones that I did not see: the unpublished ones, and the ones that were previously published, no matter in what way. The genuine ones, the suspect ones, and the fake ones.

Second Rule: the very first goal of the volume was to separate genuine inscriptions from forgeries.

In the third rule, uh, Mommsen, who was a jurist, recognized the principle of the so-called presumption of innocence, dolum nom praesumi. But he also stated that once the deceitful intent of an author had been proven, his entire credibility as a source, was invalidated, and his whole production must be labeled as forged. This is really a crucial point, which comes in also in the following point.

In point number four, he says, "I did not prosecute single inscriptions, but single authors." Meaning, that he challenged the trustworthiness of the whole production of those who had transcribed inscriptions. We can call it the principle of the "unreliability of the first witness." If the earliest transcription of an inscription comes from an author who had been identified as a forger, then no matter its contents, such an inscription must be false. So, in other words, Mommsen discarded the whole production of certain authors, like Ligorio, because he simply had no time for checking that all the inscriptions that these authors had copied, were genuine, or or false. He states that very clearly. And his conclusion is semel fur, semper ful: once a thief, always a thief. And also that it is better to to keep a genuine inscription among the forgeries, than the other way around.

-- Epigraphic Criticism and the Study of Forgeries: A Historical Perspective, by Lorenzo Calvelli

The epigraphist Onofrio Panvinio also attributed the fragments to a Iano, but abandoned the idea in favor of his theory that the monument was the hemicycle of Verrius Flaccus.8 The illustration that he published, of which I shall speak later, provides support for the theory of an arch. Carlo Fea, in the publication of his discoveries of 1816-17, accepted the view that the inscriptions belonged to an arch.9 The Italian architect Luigi Canina took up the idea and published a reconstruction of the arch (Gatti, Rendiconti, Fig. 6). He placed the inscriptions on the outer face.

But the attribution of the Fasti to the Regia practically obliterated the memory of these earlier assignments of the inscriptions to an arch. This attribution, first proposed by Piale in 1832, was not seriously considered until Detlefsen, without knowledge of Piale's work, suggested it to Henzen when the two men were working on the first edition of CIL, I. Detlefsen was himself skeptical, but Henzen took up the idea and set forth his arguments fully in CIL, 1, published in 1863. His views obtained general acceptance after Mommsen added his authority to the attribution. The Regia, where the pontifex maximus in earlier times posted each year a tablet giving names of magistrates and lists of important events, seemed eminently the right place for the official annalistic record of Rome. When in 1886 Nichols identified the remains of the Regia in front of the temple of Antoninus and Faustina, Huelsen, who had been working with Henzen on the revision of CIL, I and assumed charge of the work after Henzen's death, held firmly to the Regia as the place for the Fasti, and decided that Carlo Fea's discoveries beside the temple of Castor represented a dump of material that was not in situ [situated in the original place]. In the second edition of CIL, I and in subsequent articles published after new fragments of the Fasti were found, Huelsen presented his restorations of the Regia. There were, to be sure, some differences of opinion between Huelsen and Schon on the position that the Fasti were thought to occupy on the Regia, but no one any longer questioned the attribution. The inscriptions are constantly referred to as the Fasti of the Regia, and Huelsen's curious restorations of the Regia's wall have been widely reproduced in handbooks.

As far as I know, the first person in this century to doubt the attribution was Professor Frank Brown, and he did not put his doubts into print. As Fellow of the American Academy in Rome in 1931-33 Brown undertook a study of the Regia. Although he said nothing of the Fasti in his publication,10 the careful reader can see that there is no place for the inscriptions on his reconstruction of the monument. Degrassi proved to be a very careful reader, and Brown's work on the Regia was important in leading him to his new view. Meantime I had had indirect reports of Brown's work and knew that he was disposed to assign the Fasti to the Arch of Augustus. My knowledge of Brown's ideas, confirmed by correspondence with him, contributed to the new dating of the Fasti (21-17 B.C.) which I proposed in a paper presented at the Philadelphia Archaeological Society in May 1945 and published in this journal in 1946.11

Professor Leicester B. Holland became interested in the architectural problem of the monument to which the Fasti could have belonged. He and I had prepared a joint article in which, with acknowledgment to Brown, we argued for the attribution of the Fasti to the arch, when in September 1945 I received a letter from Degrassi informing me of his new results. They had been announced the previous spring at the Pontifical Academy, and thus had priority over our findings, as well as the advantage of work on the spot and in archives not available to us. Our paper was not published; our work and Brown's contribution to it were referred to in generous terms in a note that Degrassi added to the proof of his article (Rendiconti, p. 104).

In reaching the conclusion that the Fasti were on the arch and not on the Regia, Degrassi, with more definite evidence than we had, was influenced by much the same considerations that led Holland and me to the same result:

1. There is no place for the Fasti on the Regia as interpreted by Brown. Huelsen's familiar restoration cannot be adapted to the remains of the building.

2. Two groups of fragments of the Fasti, for the discovery of which we have specific evidence, were found at the northeast corner of the temple of Castor. These include the fragments found by Carlo Fea in 1816-17 (the stones that Huelsen argued were not found in situ) and several other fragments discovered in 1872-73. For the spot where the first group came to light Degrassi cited a drawing of the architect Gau in a communication of Niebuhr to the Prussian Academy, dated March 26, 1817.12 He might also have cited the star by which Fea on Plate II of his Frammenti dei Fasti consolari e trionfali [GT: A fragment of the fast god to be comforted from the triumphal] (Rome, 1820) indicated the site of his finds.13 For the discoveries of 1872-73 Degrassi has been able to produce unpublished archival material which proves definitely that the stones, including a fragment that Henzen and Huelsen attributed to the site of the Regia, were found close to the northeast corner of the temple of Castor.14

3. On no building to the northeast of the temple of Castor except the Arch of Augustus is it architecturally possible to restore the Fasti.

FIG. 1

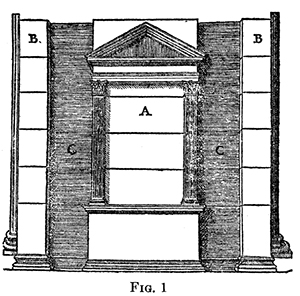

4. The foundations of the Arch of Augustus are on the very site where fragments of the Fasti were found in 1816-17 and again in 1872-73. Gau's drawing and Fea's star indicate that the spot where the stones came to light in 1816-17 corresponds to the north lateral opening of the arch. In 1546-47 sculptured decorations that would fit an arch were found in the excavation. Panvinio speaks of ornamental details15 and Metellus is more explicit in his description of sculptures: tanquam tropaea quaedam barbarorum, scuta pugiones et galeae et alia ornamenta [GT: as some trophies of the barbarians, shields, daggers, and helmets, and other ornaments.].16 The section of the third tablet, with flanking pilasters, that forms the center of Michelangelo's wall, does not appear to be a part of a long wall such as he constructed or such as Huelsen posited for the Regia; it is rather an independent unit such as was assumed by Ligorio and also, as Holland realized, though Degrassi and Gatti did not, by the unknown man who made the drawing in Panvinio's publication of the Fasti (Fig. 1). The illustration is adapted to the idea that Panvinio originally had that the building was a Iano, and not to his later view that it was a hemicyclium [sundial].17 The reproduction clearly shows a pylon with an engaged column just beyond the inscribed pilasters on either side.

As Degrassi and Gatti discovered, and as Holland concluded independently, the only place for the Fasti is inside the openings of the arch. As Gatti has shown, the width of the third tablet fits the lateral openings of the arch.18 As Degrassi has recently pointed out,19 a parallel for such inscriptional adornment of the passage-way of an arch is to be found in the quadrifront arch of A.D. 203 at Theveste.

Degrassi, aided by the important architectural contribution of Gatti, has proved beyond doubt that the Capitoline Fasti were in the lateral openings of the Arch of Augustus whose base stands beside the temple of Divus Julius. I have thought it worth while to add to the evidence he has presented the confirmation of the attribution which Holland found in the published work of Panvinio and Fea. The credit for the new discovery belongs partly to Brown. His study of the Regia, which, with the report of his unpublished results, formed the basis on which Holland and I worked, also contributed indirectly to Degrassi's investigation.

Now that the attribution of the Fasti Capitolini to the arch is definitely established, it seems curious that, in spite of the views of Ligorio, Panvinio (in his first interpretation of the monument), Fea, and Canina, the mistaken assignment of the Fasti to the Regia should have been so long accepted. Topographers and architects who have puzzled over the problem of the arch or arches of Augustus might well have shown the right way, for they have quoted Metellus on the discovery, with the inscriptions, of architectural ornaments that might have belonged to an arch.20 The real obstacle to a proper understanding of the facts was that lists of consuls seemed entirely suitable as inscribed decoration of the Regia. That was the basis of Huelsen's strange obstinacy in interpreting the evidence of the stones, and that was the reason why Schon, who saw the impossibility of Huelsen's reconstruction,21 never questioned the attribution of the Fasti to the Regia.22

The dating of the arch and the inscriptions is discussed by Degrassi very briefly in the volume (19 f.) and in great detail in the Rendiconti. The foundations beside Divus Julius have been attributed to two different arches, to the one which the senate voted to erect in 31-30 after Actium, and to the arch with which Augustus was honored after the return of the Parthian standards in 20.23 A Vergilian scholiast makes it clear that the arch commemorating the success over the Parthians stood iuxta aedem divi Iulii [GT: next to the house of the god Julius ],24 and that would have settled the date of the arch if there were not conflicting evidence from coins.

Triple arches that differ from each other in important details are represented on two series of Augustan coins;25 one of these arches on a coin from a Spanish mint is clearly associated by its inscription with the return of the standards from Parthia. The other arch, of a very peculiar type, found on a coin of the Roman mint, has no such definite association. The arch represented on it would seem to be better suited for the base found beside Divus Julius. 26 Richter solved the problem by restoring a second arch north of Divus Julius, but when no traces of that arch were found in the region he abandoned his restoration.27 Since then topographers have puzzled over the question of the arch or arches of Augustus in the Forum. On the whole, the weight of opinion has been in favor of the view that the Spanish coins contain architectural inaccuracies, that the arch decreed in 31-30 never was erected, and that the foundations we have belong to the Parthian arch.28

Degrassi and Gatti have revived Richter's earlier view of two arches close to Divus Julius, though in the absence of recognizable remains they make no attempt to fix the location of the second arch. For them the arch whose foundations we have is the one voted by the senate after Actium.29 This identification of the arch accords with the date which Degrassi assigns to the inscriptions.

The date of the inscriptions is to be determined by the time when the names of the Antonii [GT: Anthony] were cancelled in the consular lists. Holding to a view first proposed by Borghesi and since then generally accepted, Degrassi believes that the Antonii were cancelled when by decree of the senate Antony's honors were annulled in September or October of 30. Degrassi rejects my suggestion30 that the names of the Antonii were removed after the disgrace and death of Mark Antony's son Iullus in 2 B.C. The reason for the rejection is that the Antonii were left intact in the triumphal lists.31 Those lists, as Hirschfeld showed, were inscribed between 19 and 11 B.C., for they are carefully planned to fill the space, and they end with a triumph of 19 B.C. and do not include the ovatio of Drusus in 11 B.C. Degrassi accepts the view of Mommsen that the pilasters were not inscribed until after the names of the Antonii had been erased and then restored in the consular lists.

In support of this dating Degrassi and Gatti find slight palaeographical differences that indicate a change of hand between the sections of the Fasti dealing with the period immediately before and after the year 30. From the form of the letter V, clearly shown on photographs of squeezes (P1. XLIV-XLVII), they hold that the fragment dealing with the years 26-22 was not inscribed by the stone cutter who was responsible for the years 44-36. Degrassi emphasizes the slightness of the differences and suggests that the stone cutters who carried on the work after 30 came from the officina charged with the original inscription. I agree with him about the change of hand, but, as he points out, several men seem to have worked on the inscriptions, and I find a similar V in earlier sections.32 The difference may mean nothing more than that one workman from the officina was replaced by another to finish the job.

When the Fasti were assigned to the Regia, rebuilt from the spoils of Domitius Calvinus' victory, for which he triumphed in 36 B.C., there was a period of six years during which the monument could have been built and the inscriptions could have been placed on it. That period, as Degrassi recognizes, must be radically reduced if the inscriptions were on an arch built in 31-30.

Degrassi assumes that the senators, as soon as they heard the news of Actium, fought on September 2, 31, passed a decree voting the erection of an arch to Octavian, and that work was begun at once on the arch. Although all the decoration may not have been in place, Degrassi holds that the arch had been erected and its lateral openings had been inscribed with the consular lists before the senate received news of Antony's death and voted to annul his honors. That vote took place when Cicero's son Marcus was consul suffectus, between September 13 and November 1 of 30 B.C.33 At that time, in Degrassi's view, the names of the Antonii were erased.

Thus only about a year would have been available for the work, and, while that might have been adequate for the actual building, it would hardly have been sufficient for the planning of the monument and the preparation of the lists. The responsible authorities in Rome34 would have had to obtain the permission of Octavian for the erection of a structure that altered radically the character of the region beside the temple that he was building for his deified father. It would have taken time to obtain Octavian's approval, for, except for a brief stay at Brundisium early in 30,35 he was in the East during this year. Even if Octavian gave his approval promptly, and the construction of the monument could proceed at once, the adornment of the arch would have required time. Degrassi does not think that the adornment would necessarily have been completed by 30; in fact, there is an inscription dated in the year of Octavian's triumph, 29, that may, in Degrassi's view, have been placed over one of the lateral arches.36 Yet he would have us believe that, although the space over the lateral openings in the front of the arch was left vacant, the more inconspicuous interior of the openings was hastily inscribed with the consular lists. The preparation of the consular lists would have taken a great deal of time. Even if, as Degrassi believes, a list that had already been prepared was adopted, there would have had to be additions and adaptations to present the offices and titles of Octavian and also of Caesar. The period from 49 to 30 was treated in great detail in the Fasti, and one may be sure that the text was not inscribed without the full consent of Octavian. And that could not have been secured without considerable delay.

What, it may be asked, was the reason for hurry in the completion of the monument? Degrassi believes (Rendiconti, pp. 95, 97) that the arch had to be ready in order that Octavian might pass beneath it in his triumph. It is true that the decree passed after Actium, as reported by Dio, provided at the same time for triumph and arch.

But it is also true that there is no evidence that any of the so-called triumphal arches (better described by the German term, Ehrenbeigen) was erected for a triumphal procession. The general in triumph passed through the Porta Triumphalis. If he was also honored with an arch, the monument in every case for which we have specific information was set up afterwards in commemoration of the event.37 The relation of the arch to the triumphal return of the victorious commander is well illustrated by the Parthian arch. That was apparently voted as soon as news came of the restoration of the standards, presumably in the summer of 20. At the same time Augustus was voted an ovatio [GT: standing ovation] which he did not accept.38 But, although his return on October 12, 19 B.C. was celebrated with pomp and ceremony worthy of a triumph, the arch was not dedicated until many months later. The inscription on the Spanish coin, which has been recognized as a copy of the inscription on the arch, fixes the dedication in the sixth tribunitial power of Augustus, that is, between June 26, 18 and June 25, 17.39

That is the arch to which I assign the Fasti and the foundations beside Divus Julius. The identification is supported by the Vergilian scholiast. If the legend on the coin records the dedication of the arch, the Fasti were inscribed during Augustus' sixth tribunitial power. That is a more exact dating than the limits 21-17 which I proposed before the Fasti were assigned to the arch.40

As for the name of the Antonii, I am still convinced that they were erased by unauthorized action after the scandal attending the death of Iullus Antonius. I concede the validity of Degrassi's criticism that, if my date were correct, the Antonii should have been removed from the triumphal lists, which were written in larger letters than the consular records. But in a damnatio memoriae [GT: damnation of memory], official or unofficial, the main point was to remove the names from the fasti, ex fastis evellere [GT: to pull out of the fasts], and the triumphal lists are never in ancient terminology described as fasti. As Mommsen recognized, there can be no doubt from Tacitus' statement about Iullus (Ann. iii. 18) that the erasure of his name was considered.41

Iullus Antonius (43–2 BC) was a Roman magnate and poet. A son of Mark Antony and Fulvia, he was spared by the emperor Augustus after the civil wars of the Republic, and was married to the emperor's niece. He was later condemned as one of the lovers of Augustus's daughter, Julia, and committed suicide.

Early life

Born in Rome, and named after his father's benefactor Iullus and his elder brother had a disruptive childhood. His mother Fulvia gained many enemies including Octavian (nephew and adopted son of Julius Caesar). His half-sister, Claudia, had been Octavian's first wife; however, in 41 BC, Octavian divorced Clodia without having consummated the marriage and married Scribonia, the mother of Julia the Elder, Octavian's only child. Fulvia saw this as an insult on her family and, together with Iullus' uncle Lucius Antonius, they raised eight legions in Italy to fight for Antonius' rights against Octavian. The army occupied Rome for a short time, but eventually retreated to Perusia (modern Perugia). Octavian besieged Fulvia and Lucius in the winter of 41-40 BC, starving them into surrender. Fulvia was exiled to Sicyon, where she died of a sudden illness.

In the same year of Fulvia's death, Antonius' father Mark Antony married Octavian's full sister, Octavia Minor. The marriage had to be approved by the Senate as Octavia was pregnant with her first husband's child at the time. The marriage was for political purposes to cement an alliance between Octavian and Mark Antony. Octavia appears to have been a loyal and faithful wife who was good and treated her husband's children with the same kindness as her own. Between 40 BC–36 BC, Octavia lived with him in his Athenian mansion. She raised both of Mark Antony's sons and her children by her first husband together for the years of her marriage to their father. They all traveled with him to various provinces. During the marriage Octavia produced two daughters, who became Iullus' half-sisters, Antonia Major and Antonia Minor. Antonia Major was the paternal grandmother of the Emperor Nero and maternal grandmother of the Empress Valeria Messalina. Antonia Minor was the sister-in-law of the Emperor Tiberius, paternal grandmother of the Emperor Caligula and Empress Agrippina the Younger, mother of the Emperor Claudius, and maternal great-grandmother/paternal great-aunt of the Emperor Nero.

Civil war

In 36 BC Mark Antony abandoned Octavia and her children in Rome and sailed to Alexandria to rejoin his former lover Cleopatra VII (they had already met in 41 BC and were parents of twin children). Mark Antony divorced Octavia circa 32 BC. Iullus and his half-sisters returned to Rome with Octavia while Antyllus remained with his father in Egypt. Antyllus was raised by Cleopatra beside his father's children by her, Ptolemy Philadelphus, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II, and their stepbrother Caesarion.

In the Battle of Actium the fleets of Antony and Cleopatra were destroyed, and they fled to Egypt. In August 30 BC Octavian, assisted by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, invaded Egypt. With no other refuge to escape to, Mark Antony committed suicide by falling on his sword, having been tricked into thinking that Cleopatra had already done so. A few days later, Cleopatra did actually commit suicide.

Octavian and his army seized control of Egypt and claimed it as part of the Roman Empire. While Iullus' elder brother Marcus Antonius Antyllus and his stepbrother Caesarion were murdered by Octavian, he showed some mercy to the half siblings Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene II and Ptolemy Philadelphus. They were given to Iullus' first stepmother Octavia to be raised as Roman citizens. In 27 BC they returned to Rome, and Octavian was given the title of Augustus.

Career and marriage

Following the civil wars, Iullus was granted high favours from Augustus, through Octavia's influence. In 21 BC Augustus wanted his daughter Julia the Elder to marry Agrippa, who at the time was married to Iullus' stepsister Claudia Marcella Major. Agrippa agreed to the marriage and so divorced Marcella. Marcella consequently obliged Iullus to marry her. Iullus and Marcella's children were the sons Iullus Antonius, Lucius Antonius and a daughter Iulla Antonia.

Iullus became praetor in 13 BC, consul in 10 BC, and Asian proconsul in 7/6 BC, and was highly regarded by Augustus. Horace refers to him in a poem, speaking of an occasion when Iullus intended to write a higher kind of poetry praising Augustus for his success in Gaul. Iullus was also a poet and is credited with having written twelve volumes of poetry on Diomedia some time before 13 BC, which has not survived.

Scandal and death

Although when their relationship began is uncertain, Iullus Antonius became a lover of Julia the Elder. Agrippa died in 12 BC and Julia had been forced to marry her stepbrother, Tiberius. Julia's marriage to her stepbrother had become a disaster and she was desperate to divorce him if not satisfy her desires, and Iullus was open to do so. Tiberius had left Rome in 8 BC leaving Julia and her five children by Agrippa, Gaius Caesar, Lucius Caesar, Julia the Younger, Agrippina the Elder, and Agrippa Postumus, in Rome. Julia felt that her children were unprotected and may have approached Iullus to be a protector for her children, especially her two elder sons, Gaius Caesar and Lucius Caesar, who were Augustus' joint heirs.

Both contemporary and modern historians have suggested Iullus had designs upon the monarchy and wanted to marry Julia before her children Gaius and Lucius came of age possibly to form some sort of regency. It is unlikely, however, that Julia would have put her father or her sons at risk. It is possible that she planned to divorce Tiberius and make Iullus Antonius protector of her sons.

The scandal finally broke in 2 BC. When Augustus took action on his daughter Julia's copious promiscuity, Antonius was exposed as her prominent lover. The other men accused of adultery with Julia were exiled but Iullus was not so lucky. He was charged with treason and sentenced to death; subsequently, he committed suicide. Modern scholars have speculated that Iullus Antonius is one of the figures represented on the north face of the Ara Pacis, a Roman altar.

-- Iullus Antonius, by Wikipedia

I have questioned Degrassi's dating of the arch because a year, though perhaps adequate for the construction and inscription of the arch, does not seem long enough if one takes into account the planning, of the monument and the preparation of the lists. I have questioned it also because it is based on a mistaken idea of the purpose of the monumental arch. But in this paper I have not considered the evidence on date supplied by the text of the Fasti. Before the Fasti were shown to have been on the arch that evidence led me to assign the inscriptions to a period after Augustus had consolidated his power. Degrassi and I differ only about a decade in our dates, but it is a very important decade. If Degrassi is right, the Fasti represent not an official Augustan list but an earlier list, which, with some adaptation, was based on the Liber annalis of Atticus.42 If I am right, the Fasti are an official Augustan version of Roman annals. In the paper published in 1946 I presented arguments from the text of the Fasti for my view. Now I have additional evidence which I expect to present in a subsequent paper.

It is to Degrassi's splendid publication of the stones and to his masterly presentation of the material that I owe the fresh evidence. From intensive study of Degrassi's text I can testify that the student of these great records of the Roman past will find in his pages a clarity and an objectivity that are beyond all praise. Here is an enduring work of a great scholar.43

BRYN MAWR COLLEGE