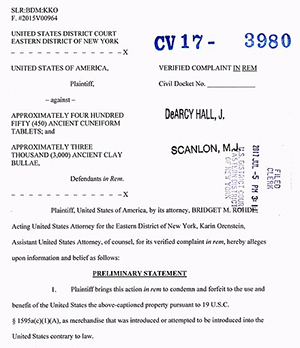

I. The World of the Counterfeiters, from "Stealing Lincoln's Body"

by Thomas J. Craughwell

2009

I. The World of the Counterfeiters

In 1647 the General Court of Rhode Island ordered the confiscation of all counterfeit wampum. The counterfeiters were Indians, members of the Algonquian nation, a large group of tribes that dominated what is now the northeastern United States. Their currency was wampum, strings of beads made from white whelk shells and purple-black quahog shells. In the Indian economy, the quahog shells were worth about twice as much as the whelk. It was an unfamiliar form of money to Europeans; but since the gold and silver coins of the Old Country were scarce in the New World, the English colonists of Rhode Island and the Dutch colonists of New Netherlands agreed among themselves to adopt wampum as legal tender. It wasn't long before the Indians realized that here was an opportunity to take advantage of the newcomers. They hoarded the valuable quahog shells for themselves, dyed the cheaper white shells a dark purplish black, then passed them off as the real thing to the undiscerning Europeans. (The record is sketchy, but it is probable that Europeans also manufactured counterfeit wampum.) It took some time, but eventually the white men discovered that they had been had. Soon thereafter, the colonists went off the "wampum standard" and returned to conducting their business with gold and silver coins.1

The Significance of Wampum

Soon after Henry Hudson claimed the land now know as the Hudson River valley for the Netherlands in 1609, the Dutch tried to exploit the area for a profit. Adventurous merchant traders came to the area as early as 1611-1612 and quickly discovered there was money to be made in the fur trade. From that point the trade in beaver pelts remained the basis of the New Netherland economy throughout the Dutch colonial period.

Furs were acquired from the Indians at a favorable rate and then shipped to Amsterdam where they commanded much higher prices. To be successful in this venture the traders needed to be able to deal with the Indians and therefore they needed to know what the Indians valued and what would be accepted in exchange for furs. From this rather pragmatic approach the Dutch learned the value of wampum. Therefore, even before the arrival of the first permanent New Netherland settlers in 1624, the Dutch had an keen understanding of wampum, which they called seawant and variously spelled as zeewant, zeawant, seawant, seewant, seewan, seawan or sewan.

Significantly, when the first colonists sent their initial shipment of beavers back to Amsterdam on the ship Wapen van Amsterdam (the Arms of Amsterdam), which departed New Amsterdam on September 23, 1626, the cargo included various symbolic gifts as evidence of the success of the colony. Among the items were strings of wampum, a tangible symbol of their command of the fur trade.

Indeed, it was Isaac de Rasiere, Secretary of New Netherland, who first brought wampum to Plymouth Plantation. As part of a diplomatic mission in October of 1627, de Rasiere presented Plymouth's Governor, William Bradford, with some colored cloth and a chest of white sugar; he also sold the governor 50 fathoms of wampum (a fathom was a six foot length containing about 360 beads, see Peña, p. 23). Later, in a letter to Samuel Blommaert, probably written in 1628, de Rasiere explained he had brought the wampum to Plymouth so the Pilgrims would not "seek after" wampum on their own. He felt a quest for wampum would lead to their discovering the fur trade and thus hurt Dutch interests (Narratives, p. 110). De Rasiere did not understand the Pilgrims were not trying to exploit the land for a quick profit but rather considered themselves to be permanent residents. In fact, the Pilgrims were already trading their surplus corn to the Indians for furs, but had no plans to emulate the Dutch and become full time fur traders.

The role of wampum in conducting trade with the Indians is mentioned in a letter of August 11, 1628 by one of the earliest Dutch settlers, the Reverend Jonas Michaelius. Michaelius, having recently arrived in Manhattan from Dutch West Africa, observed the Indians had products to sell, "but one who has no wares, such as knives, beads, and the like, or seewan [i.e. wampum], cannot come to any terms with them" (Narratives, p. 130). This is further elucidated in one of the earlier Dutch new world chronicles which discusses negotiations concerning the acquisition of pelts from the Indians for wampum and cloth. In the winter of 1634 three West India Company employees were sent from Fort Orange to negotiate a price for furs with the Iroquois Indians, located west of the fort. It seems some French traders from Lake Oneida had entered the area and were trying to gain control of the market. One of the three employees, a barber-surgeon named Harmen Meyndertsz van den Bogaert kept a journal of this adventure. On January 3, 1635 he was negotiating with the Iroquois, who offered to sell his company (the Dutch West India Company) all of their beaver pelts if they could agree to a price. Earlier, on December 30th, the Indians mentioned they had previously sold skins to French trappers. The Indians asked for four handfuls of wampum and four hand breaths of duffel cloth for each large beaver. Van den Bogaert replied he would need approval from the Director General in New Amsterdam before he could agree to the deal. Whether this agreement was approved was not related (Bogaert, pp. 15-17).

The importance of wampum to the Indian is best expressed in a letter from the Reverend Johannes Megapolensis, who was assigned to the fur trading center at Fort Orange, an outpost at present day Albany. On August 26, 1644, just over two years after Megapolensis had arrived at the fort, he wrote a short account of the Indians living in the region, the Mohawks. In this account he related the Indian attitude toward money as follows:Their money consists of certain little bones, made of shells or cockles, which are found on the sea-beach; a hole is drilled through the middle of the little bones, and these they string upon thread, or they make of them belts as broad as a hand, or broader, and hang then on their necks, or around their bodies. They have also several holes in their ears, and there they likewise hang some. They value these little bones as highly as Christians do gold, silver and pearls; but they do not like our money, and esteem it no better than iron. I once showed one of their chiefs a rix-dollar; he asked how much it was worth among the Christians; and when I told him, he laughed exceedingly at us, saying we were fools to value a piece of iron so highly; and if he had such money, he would throw it into the river. (Narratives, p. 176)

Clearly the need to understand, use and accumulate wampum was essential if one was to participate in the fur trade. New Netherland Director General Pieter Stuyvesant clearly expressed the importance of wampum to the directors of the West India Company in a letter he sent to them on April 21, 1660, where he stated:wampum is the source and the mother of the beaver trade, and for goods only, without wampum, we cannot obtain beavers from the savages. (Fernow, History, p. 470)

Typically the Dutch traded wampum and commodities, such as cloth, metal utensils and liquor to the Indians for beaver pelts. Also, although there were regulations against it, guns and gunpowder were traded for pelts. When finalizing major agreements or large purchases the commodities would typically be given as gifts, then during the negotiations the Indians would be plied with liquor and a final agreement would specify an amount of wampum to be paid per pelt.

Wampum Production on Long Island

In a fortunate coincidence for the Dutch, the east end of Long Island happened to be the center of wampum production for Indian tribes in the northeastern coastal region. Long Island wampum was well know and circulated widely. Because of the large quantity of wampum the Dutch called the island Seawanhackey, that is, place of seawan. British colonists also visited the area and considered it to be a rich source for beads; John Winthrop thought Long Island was the best location from which Massachusetts Bay would be able to acquire wampum.

The significance of the area was brought out during discussions of the realignment of the borders between New Netherland and the British colonies, which took place at the Hartford Convention in September of 1650. The secretary of New Netherland, Cornelis van Tienhoven, wrote several communications on the disputed lands. In a description of the boundaries of New Netherland written on February 22, 1650 van Tienhoven included a discussion of Long Island, in which he stated, "The greatest part of the Wampum, for which the furs are traded, is manufactured there by the Natives." (O'Callaghan, vol. 1, p. 360). In a supplemental letter written less that two weeks later, on March 4, 1650, he further explained the importance of the area:I begin then at the most easterly point of Long Island ... This point is also well adapted to secure the trade of the Indians in Wampum, (the mine of New Netherland,) since in and about the abovementioned sea and the islands therein situated, lie the cockles whereof Wampum is made, from which great profit could be realized by those who would plant a colony or hamlet at the aforesaid Point, for the cultivation of the land, for raising all sorts of cattle, for fishing and the wampum trade. (O'Callaghan, vol. 1, p. 365)...

The Distribution of Wampum

Although we know where and in what manner wampum beads were produced, very little is understood about how wampum was put into circulation. A few incites [insights]on wampum distributed in New Amsterdam during the 1650's can be gleaned from the New Amsterdam court records. Among the seven volumes of summary records that survive, describing thousands of cases brought before the court from the years 1653-1674, a few cases briefly mention isolated information concerning wampum production and distribution insofar as they were pertinent to the case in question.

From these records we learn some Dutch were employed in stringing loose wampum beads. In a case of December 8, 1653 Madaleen Jansen demanded payment of 21 florin and 15 stuivers "for wages earned in stringing wampum for Andries Kristman deceased" (RNA, vol. 1, p. 137). From the minutes of the court at Fort Orange for February 18, 1659 Baefien Pietersen stated Evert Nolden was to employ her "for a year to string seawan" but let her go after six months (Minutes, Ft. Orange, vol. 2, pp. 117-118). In a New Amsterdam case of January 17, 1665 Adam Onckelbagh (plaintiff) sued Freryck Flipzen (defendant) because:Pltf. says, that his wife strung seawant for the deft. and that the deft. will not pay here for the stringing as much wages, as she gets from others. Deft. says, he agreed with the pltfs. wife to pay four guilders per hundred for the white and two for the black, and that his wife did it again for him after that date. Pltf. denies it,. ...[the court ruled]... that deft. shall pay to the pltf. as wages for stringing according to the custom heretofore, five guilders per hundred guilders of the white, and two guilders ten stivers, of the black sewant. [RNA, vol 5, p. 176]

Clearly these were not isolated events but rather problematic cases in what seems to have been a longstanding business in which some Dutch merchants outsourced work to local women to string loose wampum. Elizabeth Peña lists additional examples in her 1990 dissertation (pp. 29-30), she also mentions a 1662 document that included the name Henry Zeewant ryger (Henry Seawant Stringer), possibly someone who operated (or worked for) one of these businesses.

The merchants who employed wampum stringers most likely obtained their beads from Indian manufacturers, for there is no evidence of large scale Dutch wampum production in early in New Amsterdam. However, we do know in the British colonies some settlers were involved in bead production during the early Seventeenth century. In 1648 John Winthrop, Jr. of Massachusetts acquired 1,000 wampum drills and 12,000 pins from Alexander Bryant and later supplied William Pynchon with wampum for his fur trade along the Connecticut River (see Peña, pp. 67-69). Rather than employing colonists to produce the beads it is more likely Winthrop made some arrangement with Indians whereby he supplied them with tools in exchange for wampum beads. The only suggestive evidence I have found possibly relating to bead production from early New York is a case from the British period. On July 7, 1668 a Mr. Young of Bermuda sold Mr. Isaac Bedloo 400 conch shells, which Bedloo then immediately sold to Fredrick Philips (RNA, vol. 6, p. 141). As conch shells were the preferred material for making wampum, it is possible these 400 shells were purchased with that end in mind.

Little is know about wampum manufacture by the european colonists during the Seventeenth century, but more information is available on the later periods. From archaeological excavations and various extant records we do know that from the 1690's through the mid Eighteenth century there were several British factories in the colony of New York producing wampum for the Indian trade, with some surviving into the Nineteenth century. (see Peña, pp. 29, 78-84 and 150-160)

Although there is no direct evidence of New Netherland colonists mass producing wampum it is probable some individuals produced what may be called "counterfeit" wampum. A New Netherland ordinance of May 30, 1650 mentioned there had been problems with loose wampum for a long time and that imitation beads of "Stone, Bone, Glass, Muscle-shells, Horn, yea even of Wood" were found in circulation (Laws, p. 115). The ordinance suggested these beads came from New England, and no doubt several did, however, it is also possible some were locally produced. Most probably these "counterfeit" beads were made by colonists hoping to turn a quick profit. Similar problems were recorded in the Plantation of New Haven for, in the New Haven General Court session of October 16, 1648 it was stated any stone wampum offered in payment of a debt should be destroyed. (New Haven Records, p. 405)

Thus, although some illegal or "counterfeit" loose wampum was probably produced by colonists, it seems during the Dutch period the wampum stringers used beads produced by the Indians. Unfortunately New Netherland court records do not mention specific lengths of strung wampum. One of the few references to wampum string lengths in New Netherland is from a letter of Director General Pieter Stuyvesant dated July 23, 1659, where it stated wampum was, "not now bartered by counting so many for a guilder or a stiver, but by the handful, length or fathom." (Fernow, History, pp. 438 439) This implied at some earlier point individual beads had been counted out but by 1659 bead counting was replaced by simply trading quantities of wampum; loose wampum was traded by the handful while strung wampum was traded by the length or fathom. Peña suggested the fathom, equal to a six foot string of about 360 beads, was the standard length in New Netherland (Peña, p. 23). Indeed that may have been the case, however it is likely bead strings of varying lengths were also traded. In an ordinance of January 3, 1657 it was stated there were several complaints of miscounting which the council intended to remidy by issuing stamped measures of wampum in strings of a quarter, a half and one guilder, that is: 5, 10 and 20 stuivers. This implies non standard lengths had been in use and often were represented as having more beads than were actually on the string. The desire was to replace both "short or long" wampum, that is lengths that were either shorter or longer than the standard. The ordinance stated:in order to prevent in future the complaints of miscounting of the Wampum, with regard to which no few mistakes have been experienced, to the loss of the Honorable Company's Treasury; also, the taking out of short or long Wampum ... from this time forward, after the publication and posting hereof, Wampum shall not be paid out or received ... by the tale or stiver, but only by a stamped measure, authorized to be made and stamped for that purpose, by the Director General and Council, the smallest of which measures shall be five stivers; the whole ten, and the double 20 stivers. (Laws, pp. 290-291)

Based on the use of merchantable white beads this would calculate to lengths of 30, 60 and 120 beads. The ordinance also stated small change under 2.5 stuivers would be paid in loose wampum (that is, by the tale or piece). Thus clarifying the statement in the law that loose wampum would "not be paid out or received" as meaning it was not to be used in large quantities but only as small change. Other portions of this ordinance, discussed below in the section on regulating wampum, were vehemently opposed by local merchants so the entire law was suspended six days later on January 9, 1657 and never seems to have gone into effect.

In daily trade sums of wampum were usually expressed in guilders rather than by the number of strings of wampum or the string length, thus for the most part we only know that so many guilders worth of wampum were traded for an item. However, a few references exist that mention string length and the majority of those citations refer to the fathom. Many, but not all, of these references are in the context of dealings with Indians, as guilder amounts were meaningless to native americans. The one exception is the earliest surviving reference to fathoms of wampum, which does not involve Indians; it is in the ca. 1628 letter of Isaac de Rasiere, Secretary of New Netherland, discussed above, in which he mentioned he had sold Plymouth's Governor, William Bradford, 50 fathoms of wampum. However, even here de Rasiere anticipated the wampum would be traded to the Indians for other goods. Fathoms of wampum are also mentioned in the administrative minutes of the court of Fort Orange for July 15, 1654, where eleven prominent citizens offered amounts of between three to six fathoms of wampum each to be given to the Indians during treaty negotiations (Fort Orange Court Minutes, vol. 1, pp. 170-171). Also, in the New Amsterdam court minutes for March 20, 1656 we discover Pieter Monfoort purchased a canoe from an Indian for 10 fathoms of wampum (RNA, vol. 2, p. 67). Both the fathom and handfull (or a hand length) were mentioned in the ordinance of November 11, 1658. In the context of a discussion on increasing the number of beads needed to equal a stuiver, the ordinance stated, "the more Beads the Traders receive for a stiver, the greater length of hands or fathoms they will give for a Beaver" (Laws, p. 358). Clearly in this context the phrase refers to the beads given by the traders to the Indians. What may represent some non standard length strings are mentioned in the court minutes from Fort Orange on June 16, 1657. In these minutes we learn of a meeting between local officials and three Indian sachems. During this meeting the three sachems offered three strings of wampum amounting to gl. 16:12, 16:9 and 13:10. Based on the then current valuation of beads at 6 white or 3 black per stuiver, the three lengths would be at least 996, 987 and 810 beads long, if exclusively black, or just under three fathoms in length or up to a maximum of 1,922; 1,974 and 1,620 beads long, if exclusively white, or over five fathoms in length. This assumes the word "string" in the text refers to a long strand of single beads rather than a belt or band with multiple rows of beads. (Fort Orange Court Minutes, vol. 2, p. 45). In the wampum charts included in this site, the guilder value of a fathom length of wampum has been included in tables 1a and 1b.

In daily New Netherland commerce strung wampum was often presented in a bag or a box. In a New Amsterdam case of September 1, 1653 we learn, "one bag of wampum labeled fl. 51:18, was deposited at the Secretary's office," (RNA, vol. 1, p. 112, the amount mentioned is 51 florin and 18 stuivers). In a case of June 28, 1665 the court was asked to rule if some wampum was good merchantable wampum valid for payment. The summary stated, "The deposited Seawan being produced in Court, the Court pronounced it good and merchantable. Two parcels, black, of fl. 22.4 and fl. 19.1, and one parcel white, of fl. 65.4." (RNA, vol. 1, p. 326). In another court case concerned with wampum quality from January 17, 1656, "a certain box of white stringed Zeewan to the amount of fl. 84.3" was presented in court. The ruling was, "that the Zeewan, exhibited by the petitioner is good merchantable Zeewan, and has, therefore, sealed the same [that is, sealed the box] in Court." (RNA, vol. 2, p. 12). In a letter from the company directors in Amsterdam sent to New Amsterdam on December 22, 1659 the complaint was made that wampum was not profitable as it could not be quickly exchanged, rather merchants and storekeepers had to hold onto "their boxes full of wampum" (Fernow, History, p.450) until the annual trading auctions. Again, on July 3, 1663 we read Marshal Mattheus de Vos deposited with the city 88 guiders 12 and a half stuivers from the goods of Nicholaas Langevlthuyzen (probably his estate) consisting of three boxes of seawan (one containing 8 florin and 8 stuivers; another containing 30 florin and 2.8 stuivers; and a third containing 30 florin) as well as one paper containing 20 florin and 8 stuivers of wampum (RNA, vol. 4, 272).

An interesting case of April 24, 1656 sheds some further light on distribution. It seems individuals purchased boxes of wampum from the wampum stringers. In this case Adriaen Blommart charged, "he received from deft. a box of Zeewan for fl. 142:3. And that only fl. 100 were found therein;" The defendant, Jacob Hendrik Varvanger stated, "he received it so counted from the Zeewan-Stringers..." Varvanger suggested the defendant's wife removed some wampum but Blommart's wife took an oath that she had not taken any. When the court asked Varvanger to take an oath that the full amount had been in the box when he handed it over, he stated he could not swear to it. In the end the court required Varvanger to pay the additional fl. 42:3.

From these few gleaning is seems some dealers obtained wampum beads at a wholesale or bulk purchase rate from the Indian bead makers. Local woman were then hired to string these beads, probably in fathom lengths, then the dealers sold boxes or bags of stringed wampum to the public.

In addition to locally made wampum the sources often mention poorer quality wampum brought into New Amsterdam from the outside, especially from the New England colonies. Indeed, the influx of poor unpolished wampum was given as a reason for the need to regulate wampum value in the ordinance of April 18, 1641, discussed below. This poorer quality wampum was strung but it sometimes circulated as loose wampum beads. Frequently loose wampum contained several broken beads that could not be strung. These broken beads, like the unpolished, chipped or blemished beads, were unacceptable to the Indians and thus were deemed unmerchantable. Sometimes individuals had the court inspect wampum to resolve a dispute as to whether the beads were of good merchantable quality or not. A few instances have been mentioned above in the context of wampum bags and boxes. In those cases the wampum was declared to be good but in a case of May 11, 1654 Willem Albertson deposited two bundles of wampum with the court in payment of a 100 guilder debt. The court ruled the wampum was unacceptable and would be sold to make partial payment. Albertson would be required to pay the balance of his debt in either beaver or good current wampum (RNA, vol. 1, p. 197). The problems caused by poor wampum are discussed below in the section on wampum regulations.

-- Money Substitutes in New Netherland and Early New York: Wampum

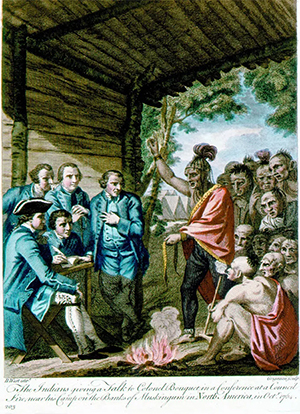

The Indians giving a Talk to Colonel Bouquet in a Conference at a Council Fire, near his Camp on the Banks of Muskingum in North, America, in Oct. 1764.

When William Penn first settled in America, his primary task was to establish a peaceful rapport with the Lenape people native to the land. As part of their agreement of friendship, a precious belt of wampum was produced, with figures in purple clasping hands against a background of white; it was a physical reminder of their accordance. George Washington, as a young officer, found himself in possession of one of these shell bead belts -– a gift from the French to their Indian allies -– and the meaning of the belt was grim. Four houses were laid out in the beads, symbolizing the four posts the native tribe had agreed to defend. Washington would negotiate with the Indians and persuade them to return the belt to the French, in essence dissolving the treaty between them. Wampum or wampumpeag, though simple beads woven together with cord, carried enormous significance and played a pivotal role in the alliances and interactions between people throughout it’s history.

In the waters off Cape Cod stretching down through to New York, a variety of mollusk called the quahog is quite plentiful. What is remarkable about this particular clam is that after the meat is removed from the shells, brilliant purple or black striations ring the edges of the shell. To the native people whose lands covered the areas of the Northeastern shores, these shells were considered precious. Through an unfortunate series of events, wampum became recognized as a currency by European colonists and traders and to this day is still wrongfully described as “shell money”.

The Role of Wampum Prior to the Arrival of Europeans

Iroquois Wampum Belt in the collection of the British Museum -– 1600-1800.

The coastal Algonquin speaking tribes have been making wampum from as early as 2500 BC -– this prehistoric form was a flat, disc-like bead. Later, tube shaped wampum would dominate the historic era.

The technique for producing wampum was one that had to be acquired through patience and practice, as the shells were very delicate when they were cut into beads. Using a stone drill called a puckwhegonnautick, was used to bore a hole into each bead for stringing -– drilling halfway on one end before flipping the bead to drill the rest of the way. The layers of calcium carbonate that compose the clam’s shell are brittle and while seemingly hard they could shatter into pieces if not worked carefully. Once completed, the wampum was strung on animal sinews or vegetable fibers and made into “belts” of solid beads, often with symbolic designs to record historical events.

White beads, called wampi, were made from whelks called Meteauhock in Algonquin. Purple of Black beads, called mercenaria, were made from quahog clam shells. This is known by the Haudenosaunee Confederacy by several names: “the Remembrance belt”, “the Defeat of the French Record belt” or “the Peacemaker belt”.

While the idea of making beads suggests that wampum was for jewelry, for natives of the Atlantic shore these beads transcended mere ornamentation. Wampum was used as a means of communication, remembrance, or as a means to bestow honor. Tribes would call each other to meetings by sending a wampum belt. Treaties were made and recorded in wampum, as physical proof of the contract made between parties -– cutting up a belt of wampum meant that the treaty was violated or rejected. An exchange of wampum would constitute an engagement between a man and a woman. The dead would be buried with wampum. It was essential for conflict resolutions between individuals -– a gift of wampum would turn away the wrath of the wronged party. Wampum also denoted the status of the individuals wearing it within their sachem’s social strata. Belts of wampum recorded historical events. Foreigners describe the scenes at some of the great tournaments the Natives played -– games that were similar to soccer or rugby that lasted for days -– and they mention that enormous numbers of wampum strings were hung upon rafters or posts to be received by the winning team.

The Monetary Worth of Wampum Realized

It was only during an encounter with the Dutch that wampum would take on a sense of monetary value in the eyes of Europeans. In 1622, a trader from the Dutch West Indies Company took a high ranking member of the Pequot sachem hostage, threatening to kill him if a hefty ransom was not received. Over 280 yards of wampum was the ransom deemed appropriate for the status of the captive -– to the Dutch trader, it seemed that the most prized possession of the native Americans were shell beads. While the reciprocal exchange of the wampum was not capitalistic exchange, the Europeans soon began to use the beads like currency to purchase beaver pelts and other valuable furs.“After two years of trader persistence, wampum became an item of mass consumption, and Plymouth had effectively eliminated most of its small-scale competitors.… [Once] a symbol of prestige, wampum had become a medium of exchange and communication available to all, leading Indians through-out New England toward greater dependence on their ties with Europeans.”

— NEAL SALISBURY – MANITOU AND PROVIDENCE

The Power Struggles Behind Mass Production Of Wampum

The Dutch encouraged tribes to devote themselves solely to the production of wampum (called Zeewant in Dutch, so the Pequot and the Narragansett tribes busied themselves with the manufacture of what would be known for centuries following as “Indian money”. Tribes that were left out of this monopoly on wampum production would pay tribute to the more influential tribes, to keep their alliances strong and ensure their protection. Later, the tensions and power struggles between English and Dutch colonies and these two influential tribes producing wampum would result in the Pequot War, where the main wampum production or wampum storage villages were targeted and the entire Pequot tribe would be destroyed. With the Pequots being removed from the trade, the Narragansetts gladly stepped into the void left in the market.Wampum was considered legal tender from 1637 to 1661 (and even up through the 1670’s in some colonies) with a set exchange rate against the Dutch stuiver.… It answers all occasions, as gold and silver doth with us.

— DANIEL GOOKIN, MASSACHUSETTS MISSIONARY TO THE WAMPONOAG

[As] This wampum’s value as currency [was] realized, the culture behind the production of the beads altered. The Dutch were already using Venetian glass beads for trading with other indigenous peoples they interacted with in Africa and India, and the natives living in North America were amiable to innovative products, to the idea of acquiring new spiritual power and to engaging socially and making alliances with newcomers, expecting that there would be balance and reciprocity as it existed within their own culture. In some wampum belts, glass beads are mixed with authentic shell beads as part of a repair -– or simply used as interchangeable in meaning and power with the shell beads.

An 18th c wampum belt in the collection of the Penn Museum, showing a single blue glass bead incorporated.

Wampum Looses Monetary Status

A change that took effect when wampum was used as currency is one that most everyone familiar with minted currencies: counterfeit.4 The rates for beads were based on their rarity -– the white beads begin [being] most prevalence [prevalent] and least costly, the purple being rarer and more costly and the black beads being the rarest and highest in rate of exchange. The temptation to dye inexpensive white beads with black dye to pass them off as more expensive black beads was too much for some enterprising souls, so the market was flooded with counterfeit currency. Laws were passed to try to curb the influx of counterfeit wampum, stating: “All wampum was to be strung in uniform units of one, three, and twelve pence in white and blacke at values of a pence 6 pence, 2 shillings 6, and 10 shillings…“5 Connecticut ordered that “no peaque, white or blacke, be paid or received but what is strung in some measure, suitably, and not small. great. uncomely. or disorderly mixt, as formerly it hath been.“6

A 18th c. portrait of Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, one of the four Mohawk “kings”, holding a belt of wampum.

Around this same time, the lucrative business of the American fur trade died down as the West Indies imports of sugar, molasses, indigo, tobacco and cloth became highly profitable -– as was the timber exported from the colonies for shipbuilding. Minted silver coins were being used in exchange for goods in the islands, and in the 1650’s they ended up in the American colonies as well. The Massachusetts Bay Company set up a mint in Boston, and began producing their own coinage, the Boston or Bay Shilling. The sudden abundance of coin and the shifting market demands caused wampum to become obsolete as a legal tender. In 1661, the wampum valuation laws were repealed and wampum would no longer have a set exchange rate, only that agreed on by the parties involved in the transaction. Tribes like the Narragansetts, who had focused their communal efforts so completely on the production of wampum, would find they had no other enterprise to fall back on. While the once precious shell beads were still made in following years, their ancient spiritual and communicative powers remained somewhat undermined and their monetary value was completely diminished.

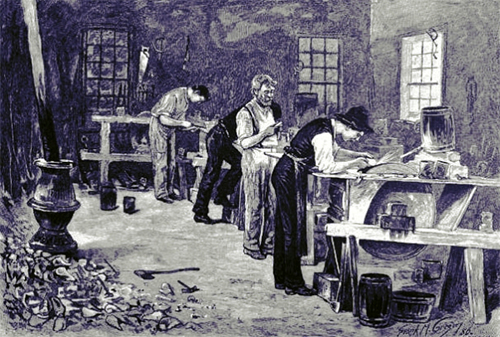

Inside Jahon. W. Campbell’s wampum factory set up in 1810 to supply the demand for wampum among plains tribes.

-- Wampumpeag, The Bead Of The Realm: America’s First Currency, by Niobe, hitorforum.com

From Pascack To The Plains: The Story Of Campbell Wampum

by Pascack Historical Society

February 14, 2016

The Pascack’s Campbell connection started when John W. Campbell (1747-1826) of Closter moved with his wife Letitia Van Valen to a farm they purchased on Kinderkamack Road North in Montvale, close to the New York State border. John W., like many farmers of his day, found a second job during the long winter months. He chose to create wampum, beads made out of clam shells, that the Indians used for a medium of exchange.

John W. is credited with inventing the shell “hairpipe” wampum made from Caribbean queen conch shells that came as ballast on trade ships heading for New York City. These tubular beads can be seen in early photographs on the breastplates of Indian warriors. These shell hair pipes put the Campbells on the map.

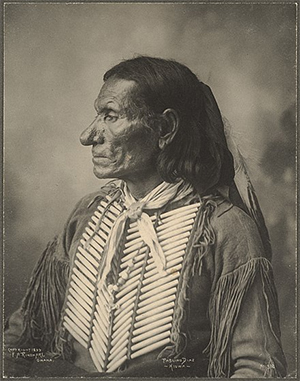

Pablino Diaz (Kiowa) wearing a hair pipe breastplate, 1899

In 1878, Joseph H. Sherburne became a trader to the Ponca people. The Ponca purchased great quantities of corn cob pipes from Sherburne, but only used the stem of the pipes as beads. White Eagle showed the trader a necklace made of the pipestems and asked if they could be ordered in bulk. Sherburne contacted S. A. Frost in New York about producing tubular bone beads and within a year, he had enough hair pipe beads to sell to the Ponca as well as other Indian traders.

-- Hair pipe, by Wikipedia

In 1808 John W.’s son Abraham (1782-1847) moved to Main Street (Pascack Road) Park Ridge, where he opened a blacksmith shop and wampum bead business. Abraham’s sons John A., James A., David A., and Abraham Jr. eventually became partners in the blacksmithing business and expanded the production of wampum.

The four weathered ledgers, never before seen by the public, were donated to the museum by Campbell descendants Linda Gifford VanOrden of Allendale and Susan Accardi of Simsbury, Connecticut. The sisters, who were raised in Hillsdale, inherited the ledgers from their uncle, the late Howard I. Durie (1919-1990), noted historian, genealogist and author of the Kakiat Patent.

To most people a wampum belt means any beaded belt made by Indians. Glass beads were introduced by white traders, and with these the Indian people did beautiful embroidery work. Before the introduction of glass beads, embroidery work was made with porcupine quills. The long hair from the bell or chin whiskers of moose was also used. With the introduction of the crude glass bead, the far more artistic porcupine quill and moose hair embroidery became a lost skill.

The true wampum bead was not made of glass. Along the Atlantic coastal waters from Cape Cod to Florida is found the quahog or round clam shell. Using this material the coastal Indian peoples made wampum beads. These were long, cylinder-shaped beads about one-fourth inch long and one-eighth of an inch in diameter in both white and purple. In ancient times wampum was strung on thread made of twisted elm bark. The word wampum is an Algonquin Indian term for these shell beads used by the Indians of the New England states. In the Seneca language it is called Ote-ko-a, a word that is the name of a small fresh water spiral shell. “Wampum” is the name that has survived to the present day. The early Indians of the Atlantic seaboard used this white and purple wampum for personal decorations as well as for trading purposes. Belts, wrist bands, earrings, necklaces, and headbands of wampum were observed by early white colonists while visiting New England Indians. The Indian people originally drilled this wampum shell with stone or reed drills. Later, iron drills were substituted.

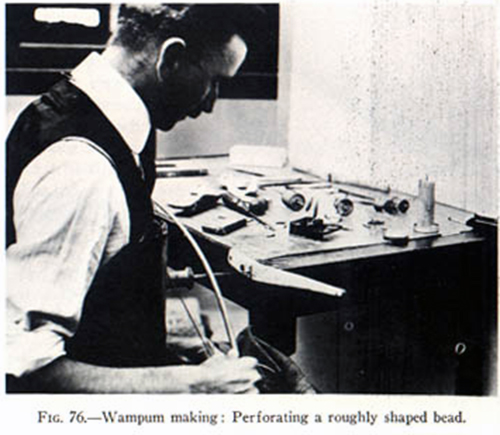

Long Island Indians were especially skilled at manufacturing wampum. The process was simple, but it took long hours of practice before one was good at it. It took a great deal of patience and labor to make these beads. First the shell had to be broken into white or purple cubes. These cubes were clamped into a fissure split of a narrow stick. This was placed into a larger sapling splint in the same way. They were put on a firm support and a weight adjusted to cause the split to grip the shell firmly, holding it securely. A drill was braced against a solid object on the worker’s chest and adjusted to the center of the cubes. A pump or bow drill rotated the drill. From a container placed over the closely clamped shell cube drops of water fell on the drill to keep it cool. One had to be careful that the shell did not break because of overheating caused by friction. According to Iroquois tradition, peach pits were broken and boiled in water. The resulting liquid made the shell soft during the drilling process. When a hole was drilled half way through the shell, it was reversed and a hole was drilled from the other side. The next part of the process was to shape and smooth the outside of the wampum bead. The beads were strung on lengths of thread or string and worked back and forth in a grooved stone. Five- to ten-foot lengths of wampum could be made in one day.

Even European settlers became wampum makers, and the first money of the American colonists was wampum. Wampum has often been called the money of Indians, but this is not true. Indians did not use it as currency in any way. By 1627 the Dutch were busy making counterfeit wampum. As late as the year 1875, a German community in Bergen, New Jersey, was busy making wampum for trade with the Indians.

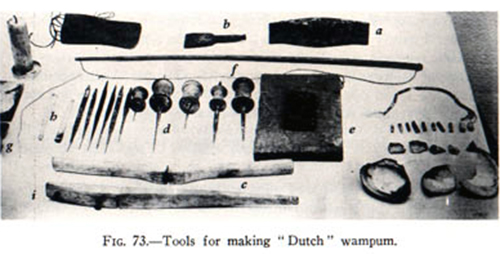

Fig. 73. Tools for making "Dutch" wampum.

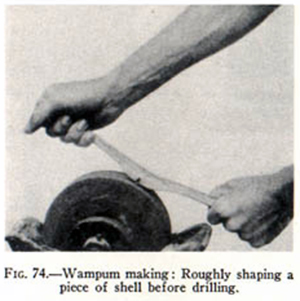

Fig. 74. Wampum making: Roughly shaping a piece of shell before drilling.

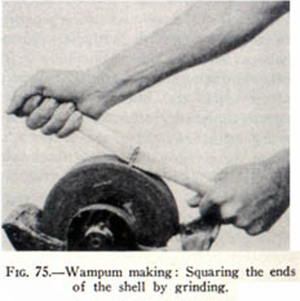

Fig. 75. Wampum making: Squaring the ends of the shell by grinding.

Fig. 76. Wampum making: Perforating a roughly shaped bead.

From: Beads and Beadwork of the American Indians, by William C. Orchard, 1975, Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation (pp. 84-86.

At first only the coastal Indians had wampum. The east end of Long Island was the original seat of wampum trade. The Narragansett Indians who were related to these Long Island people soon controlled the wampum trade. They supplied the nations of the interior with their wampum, which was exchanged for furs from the western Indians.

-- Wampum Belts, by Indian Time

But hard money was still in short supply, so in 1652 the government of Massachusetts authorized the first mint in British North America. The Massachusetts mint issued a series of silver coins, some stamped simply "NE," for "New England," others engraved with images of oak, pine, or willow trees. Today, collectors covet these coins as the first examples of American-made money. But coins from Massachusetts bear another distinction -- among them were the first coins counterfeited in America, beginning around 1674, when John du Plessis was found guilty of turning out pewter imitations.2 Alas, the du Plessis case was not an isolated incident. Very quickly, counterfeiting became rife in the colonies.

In 1682 William Penn complained that he could not bring his "holy experiment" in Pennsylvania to fruition when half the coinage in his colony was phony. Counterfeit shillings were so common in Connecticut in 1721 that the colonial government despaired of ever getting them out of circulation. Delegates from the lower house of the Connecticut legislature suggested they accept the bogus coins as legitimate currency and assign them an actual value of two pence. In 1735 the governing council of South Carolina conceded that the colony's paper money was so debased by counterfeits that the colony had no choice but to recall all the fifteen-, ten-, four-, and three-pound notes. Making the matter worse was the English custom of transporting felons to America. In 1770 the convict ship Trotman docked in Maryland. Among the exiles were a number of counterfeiters, who within days of coming ashore were back in business.3

Poverty and illiteracy allowed counterfeiting to flourish. Since few colonists had ever seen a gold coin, they would accept any shiny, circular, gold-colored piece of metal as the genuine article. In the case of paper currency, so few colonists could read that sloppily printed counterfeit currency bearing such absurd spelling errors as "Instice" for "Justice," or "Two Crowes" for "Two Crowns," passed undetected through the hands of the unlettered. Consequently, colonists who were barely scraping by suffered the most from bad money, while the literate and well-to-do spotted these crude jobs at once and refused to accept them.4

Initially, the courts treated counterfeiting as a misdemeanor. A New York silversmith caught producing false coins in 1703 was punished with a small fine. But as counterfeit money took a greater toll on America's economy, the judges' sentences became harsher. In 1720 a Philadelphia counterfeiter was hanged, and in Newport, Rhode Island, a counterfeiter had his ears sliced off as a prelude to being sold into indentured servitude. To show that it meant business, New Jersey's colonial government adopted a motto for its three-shilling note: "To Counterfeit is Death."5

In spite of the shoddy coins and paper money in circulation, some ambitious counterfeiters understood that they would realize greater profits by turning out a superior product. In the early part of the eighteenth century two of the most successful counterfeiters in America were women. In 1712 Freelove Lippencott, the wife of a Rhode Island sailor, traveled to England, where she had plates engraved, patterned on the paper money of Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Back home she recruited a gang of men known as shovers to put her false currency into circulation.6

The most ingenious of the eighteenth-century American counterfeiters was Mary Butterworth, the wife of a prosperous house builder in Rehoboth, Massachusetts. She was thirty years old and the mother of seven children in 1716, when she started making paper currency in her kitchen. Butterworth's method was breathtakingly original. First, she placed a piece of damp muslin over the bill she planned to counterfeit, then ran over it with a hot iron -- the one she used to press clothes. The heat, by causing some of the ink to adhere to the muslin, created a pattern. Next, Butterworth laid the pattern on a blank piece of paper and ran the iron over the muslin again, a process that transferred the ink to the paper. With a fine pen she filled in the rest of the details of the bill, then burned the muslin pattern, thereby eliminating the evidence. It was a brilliant method, one that worked so well that Mary Butterworth turned her counterfeiting into a cottage industry employing three of her brothers, Israel, Steven, and Nicholas Peck, as well as Nicholas's wife Hannah, to help her produce high-quality forgeries of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut currency. Mary Butterworth sold her product (she never used her bogus money herself) at half its face value to her shovers, among whom were a neighborhood innkeeper, some of the carpenters who worked for her husband, and the local deputy sheriff.

For seven years Mary churned out her bad money without attracting the attention of the law. Then, in 1723, she came under suspicion of counterfeiting. The authorities searched her house, but they found not a scrap of evidence against her. After all, there is nothing incriminating about a clothes iron and a fine pen. Nonetheless, the episode unnerved Mary; she gave up counterfeiting and lived quietly until her death in 1775 at eighty-nine years of age.7

The undisputed king of eighteenth-century American counterfeiters was a Morristown, New Jersey, engraver named Samuel Ford. In the I760s and 1770s he produced imitations of New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania currency so good that even the provincial treasurers of those colonies could not tell the difference between a forgery by Ford and the real thing. Small wonder that he was never caught.8

With the outbreak of the American Revolution, the Continental Congress authorized a national paper currency -- popularly known as continentals -- backed by the credit of the United States. This was a problematic claim, for no European power had recognized that the American rebellion marked the birth of a legitimate new nation, let alone that the rebels possessed the type of credit international bankers would respect. There was also the matter of the American treasury -- in essence, none existed. The thirteen states collected customs duties and taxes, and precious little of what they took in made its way to the congressional coffers in Philadelphia. Realizing that the new American currency had an unstable foundation, the British concluded that it would not take much to depreciate it. So around January 1776 a printing press was hauled out to the warship HMS Phoenix in New York harbor; the ship became a British-sanctioned counterfeiting workshop. The British counterfeits of continentals were excellent -- so good, in fact, that in April 1777 the king's counterfeiters ran an ad in a New York newspaper offering to sell their false currency to loyal subjects of the Crown at a rock-bottom price -- the cost of the paper it was printed on. The counterfeiters boasted about their bills: "[They] are so neatly and exactly executed that there is no Risque ... it being almost impossible to discover, that they are not genuine."9

The British found an indigenous distribution network for their phony money among the Tories, Americans who remained loyal to King George. One such loyalist, Colonel Stephen Holland, operated a network of shovers that extended from his home in New Hampshire down to the colonies in the South. Two other distributors, David Farnsworth and John Blair, were arrested by supporters of the American cause in Danbury, Connecticut, with ten thousand dollars' worth of false continentals on their persons. They tried to excuse themselves, saying that they were petty criminals compared with other members of their gang, who had passed forty thousand or fifty thousand dollars in bad currency elsewhere.10

The British lost the war, but they won the campaign to undermine America's finances. By 1779, less than three years after it was first issued, the continental currency was so debased that Congress declined to print any more. Fortunately for the new United States, its finances were rescued by the timely arrival of loans from France and the creative accounting of Robert Morris, the financial wizard of the Revolution.11

After the continental currency debacle, the general trend after the Revolution was toward establishing a monetary system based on gold and silver coins, a movement that gained momentum in 1792 when Congress authorized the establishment of the U.S. Mint. This did not stop the counterfeiters, however: they simply acquired new equipment to manufacture coins. A story has come down to us of an English counterfeiter named Peach who set up shop in the basement of a house on James Street on Manhattan's East Side, in what is now Chinatown. Peach manufactured "gold" Spanish doubloons, which had been esteemed good money in America since colonial times and were still in circulation in the 1820s. He was a man who took pride in his work; his false doubloons were of exactly the same weight and stamped with precisely the same design as authentic doubloons. Peach even took the trouble to "age" his coins. He churned his finished product in a barrel of sawdust, which rubbed the shine off the new coins and gave them a much-handled appearance. Next, he scattered the coins on a sheet of iron, then held the iron over a fire until the doubloons were slightly tarnished around the edges. This was a nice, authentic touch, because genuine doubloons really were tarnished, as a result of the coins' soaking in bilgewater in the hold of the Spanish treasure ships that distributed doubloons to Spain's colonies in the New World.12

Although the United States shied away from instituting a national paper currency, individual banks issued their own paper money known as banknotes. Unlike a national currency, the banknotes had no uniform design -- bankers adopted whatever style they found appealing. This absence of a single, universally accepted banknote proved a bonanza for counterfeiters. By 1859, the eve of the Civil War, nearly four thousand different types of counterfeit bills were in circulation. Some were authentic banknotes whose denomination had been tampered with -- a one-dollar bill became a ten; a five-dollar bill became a fifty. Others were outright counterfeits, ostensibly drawn against real or imaginary banks.13

Like all criminal professions, counterfeiting had its own vocabulary. Coney and queer were terms for counterfeit currency. The person who manufactured the false money was a coney man or a koniacker. Boodle meant bundles of counterfeit bills. A boodle carrier sold the counterfeit currency to distributors known as shovers. To shove meant to pass counterfeits in public as real money. As for real currency itself, that was rhino, nails, putty, or spondulics.14

In the years before the Civil War, counterfeiters began to congregate in carefully selected urban areas. Before 1820 counterfeiters had set up shop in any place that suited them; some were in small towns, others out in rural areas. Some even operated out of Canada. After 1820 almost all counterfeiters relocated to cities -- especially cities that had a substantial printing industry and were major transportation hubs. Since there were more printing and engraving businesses in the lower Manhattan neighborhood bounded by Broadway, the Bowery, Houston, and Chatham Streets than anywhere else in the country, this area became the unofficial capital of American counterfeiting. St. Louis did not have many printing businesses, but it enjoyed two other assets that counterfeiters prized. First, its location on the Mississippi River and its proximity to the Ohio and Missouri Rivers made it a natural distribution center for channeling the queer into the Midwest and the Far West. Second, Missourians hated banks. Time and again voters had rejected proposals to charter a state bank. As a result, the only paper currency in Missouri was banknotes from out-of-state banks, a situation that made the citizens of St. Louis and the rest of the state especially easy marks for counterfeiters.15

Yet in the years before the Civil War, as counterfeiting spread across the United States, it met with only haphazard resistance from local law enforcement. Certainly arrests were made: nineteen counterfeiters were arrested in New York City in 1830; thirty-one were picked up in 1840. Arrests dropped, inexplicably, to thirteen in 1850, then skyrocketed to ninety in 1860. In spite of these statistics, neither New York nor any other American metropolis ever launched an all-out campaign to eliminate counterfeiting from its jurisdiction. City police forces of the pre-Civil War era were not designed to fight counterfeiters. City cops were not trained as detectives. They were patrolmen who walked an assigned area of the city, the rationale being that the presence of a uniformed officer on the streets would make the criminals of the neighborhood think twice. A different type of lawman was required to track down counterfeiters, someone who had informants among the criminal underclass, who perhaps could work effectively undercover, and whose duties permitted him to spend months closing in on a suspect. No such crime-fighting organization existed in the United States of the 1860s. It took the crisis of civil war to bring such an agency into existence.16