by Pietro Zaccaria

From Defining Authorship, Debating Authenticity: Problems of Authority from Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance

Edited by Roberta Berardi, Martina Filosa, and Davide Massimo

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

1 Introduction

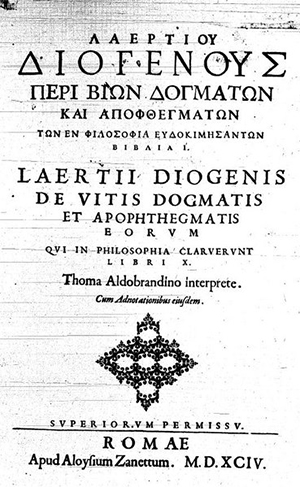

In the context of a discussion about authority, authenticity, and authorship, the figure and work of the 1st century BC scholar Demetrius of Magnesia is surely worthy of consideration.1 Demetrius, a contemporary of Cicero, is the author of a pinacographical/biographical work entitled On Poets and Writers with the Same Name. Even though the work is lost, we can reconstruct, at least to some extent, its content, structure, and character thanks to about 30 fragments preserved by Dionysius of Halicarnassus (fr. 1 Mejer), Plutarch (frr. 2-3, 5 Mejer), the author of the Lives of the Ten Orators (fr. 4 Mejer), Harpocration (fr. 6 Mejer), Athenaeus (fr. 7 Mejer), and Diogenes Laertius (frr. 8-31 Mejer).2

The work was aimed at distinguishing between homonymous writers, providing biographical, bibliographical, and literary information. As the Greeks were aware of the fact that homonymy could lead to misleading attributions of literary works,3 it comes as no surprise that Demetrius also dealt with the problem of pseudepigraphy. However, this aspect of his work has been somewhat overlooked by scholars.4

The aim of this article is to reconstruct Demetrius' method of detecting pseudepigraphic works as much as possible on the basis of the available evidence. It is structured in three parts. First, the content, structure, and aim of Demetrius' work On Poets and Writers with the Same Name are briefly sketched in light of the extant fragments. Then, three fragments testifying to how Demetrius dealt with the problem of pseudepigraphy are analyzed in detail (frr. 14, 10, 1 Mejer). Finally, some general conclusions are drawn about Demetrius' approach to pseudepigraphy and its relationship to the method later developed by his younger contemporary Dionysius of Halicarnassus.

2 Demetrius' On Poets and Writers with the Some Name

Demetrius' On Poets and Writers with the Same Name ([x]) was a pinacographical/biographical work structured in separate alphabetical entries, each of them providing a full list of men (above all writers) who went by the same name. Within each entry, the various homonyms were distinguished on the basis of their biography and literary output. This work, the only one from antiquity devoted to homonyms of which a number of fragments is still extant, was probably intended as a biographical/bibliographical support to be consulted in case of uncertain identifications or attributions.5 We do not know the precise chronology and place of composition of the work, but it seems reasonable to assume that it was written in the second quarter of the 1st century BC and that copies of it circulated in Rome by the mid-1st century BC.6

Our knowledge of its structure mainly depends on two important testimonies provided by Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Diogenes Laertius. in his essay On Dinarchus, Dionysius literally quotes Demetrius' entry on various men called Dinarchus (Din. 1.2-2.1 = fr. 1 Mejer). I will come back to this passage later in this article. For the moment, it is sufficient to recall the structure of Demetrius' entry quoted in it. At the very beginning, the number of men called Dinarchus is given. Then, each namesake is briefly identified, primarily on the basis of the literary output and of short biographical remarks (relative chronology, origin, etc.). Finally, a more detailed description for each namesake is provided separately. On the basis of this fragment, scholars have usually concluded that all entries consisted of a 'general' and a 'detailed' part.7 However, the very fact that Demetrius explicitly declares his intention to speak in detail of the various 'Deinarchoi' ([x]) speaks against the assumption that all entries had a separate detailed part. Diogenes Laertius (1.38 = fr. 8 Mejer) reports Demetrius' entry on men called Thales. Here, only a general characterization is given for each homonym. in this case, however, we do not know whether Diogenes Laertius quoted the entire entry of Demetrius. On the basis of these fragments, we can conclude that the order of the homonyms within the lists was not strictly chronological and that non-writers were included as well. The assumption, based on the book title, that Demetrius only listed writers is patently contradicted by the evidence.8 For example, painters and philosophers who did not write were certainly also included (frr. 8, 25 Mejer).

The extant fragments testify that biographical information played a central role in Demetrius' work (frr. 2-9, 11-13,15-16, 18-24, 27-29, 31 Mejer), but bibliographical information was also important, because the attribution of literary works was one way of distinguishing between homonyms (frr. 1, 7-8, 10, 14, 24- 26, 30 Mejer). Demetrius might have relied on book catalogues, as is suggested by the fact that he sometimes quoted the beginning of literary works (Diog. Laert. 8.85 = fr. 26 Mejer).9 It has reasonably been suggested that Demetrius based his bibliographical information on the pinakes [a lost bibliographic work composed by Callimachus (310/305–240 BCE) that is popularly considered to be the first library catalog in the West; its contents were based upon the holdings of the Library of Alexandria during Callimachus' tenure there during the third century BCE.] of the libraries of Alexandria and Pergamum.10 At any rate, it is uncertain whether or to what extent he himself provided full catalogues of works.11 Dion. Hal. Din. 1.2-2.1 (fr. 1 Mejer) shows that Demetrius could speak of the literary output of a writer without providing a list of works (see below). Closely connected with Demetrius' interest in the literary output of the various homonyms is his concern with the problem of pseudepigraphy. This is testified by three important fragments, preserved by Dionysius of Halicarnassus (fr. 1 Mejer) and Diogenes Laertius (frr. 14, 10 Mejer), that show that Demetrius adopted a conscious, critical attitude towards the problem of spurious writings.

3 Xenophon's Constitution of the Athenians and the Spartans (fr. 14 Mejer)

In the bios of Xenophon, Diogenes Laertius mentions Demetrius at the end of the list of the philosopher's writings (2.56-57 = fr. 14 Mejer):12

[x]

[x]

[x]

He (scil. Xenophon) wrote about forty books, which are divided in different ways:

the Anabasis

(for which he composed a proem to each book, but not one to the whole work),

Education of Cyrus,

Hellenica,

Memorabilia,

Symposium,

Oeconomicus,

On Horse Racing,

On Hunting,

On the Duty of a Cavalry General,

Apology of Socrates,

On Revenues,

Hieron or On Tyranny,

Agesilaus, and

Constitution of the Athenians and the Spartans,

about which Demetrius of Magnesia says that it is not by Xenophon.

While it is not certain whether the entire list of Xenophon's works derives from Demetrius, the sentence regarding the contested authenticity of the politeia(i) can be considered a certain fragment of his.13 Demetrius is the only ancient source doubting the authenticity of the Constitution of the Spartans and possibly also of the Constitution of the Athenians. The wording used by Diogenes Laertius is not clear, and its meaning has been greatly debated. The main problems arise from three considerations. First, nowadays it is the Constitution of the Athenians that is usually considered spurious, not that of the Spartans: accordingly, some scholars think that the order of the two Constitutions must have been reversed by Diogenes Laertius or his source, who, they argue, misunderstood Demetrius' text,14 Second, in the manuscripts of Xenophon's works the order of the two Constitutions is Spartans-Athenians.15 Third, the singular forms [x] and [x] might suggest that Diogenes Laertius and/or Demetrius considered the two Constitutions as a single work, the authenticity of which was rejected.16 Furthermore, if the book order was in antiquity the same as in the Mediaeval manuscripts, the fact that we find a [x] in the opening sentence of the Constitution of the Athenians might suggest that this work was thought as the continuation of the Constitution of the Spartans.17 Faced with these problems, scholars argued that Demetrius considered either the Constitution of the Spartans18 or t he Constitution of the Athenians19 or both works20 as non-Xenophontic.

The question cannot be settled on linguistic grounds: since there are no parallel passages in Diogenes Laertius where two or more constitutions are paired together,21 it is not possible to determine whether Demetrius/Diogenes Laertius intended the two works as a single one. Nor there is any reason to claim that the text of Diogenes Laertius, as it stands, is corrupt or that he misunderstood his source. The simple fact that the manuscripts of Xenophon report the order Constitution of the Spartans-Constitution of the Athenians and that the latter has the particle [x] in the first sentence do not necessarily imply that the two Constitutions were considered a single work by Demetrius/Diogenes Laertius.22 Moreover, and more importantly, we should resist the temptation to change the transmitted text in order to ascribe to an ancient scholar a conviction of modern philologists.23 Consequently, the best and most prudent solution is to keep the transmitted text and (leaving open the question of the single work) to assume that Demetrius regarded the Constitution of the Spartans or both Constitutions as spurious. As regards the sequence of the works, another possible scenario might be added to those proposed by scholars thus far: Diogenes Laertius may have found in his source the two Constitutions in the same order as in the Mediaeval manuscripts (Spartans-Athenians), but might have changed their position in order to put the work of which the authenticity was doubted last (Athenians-Spartans).24

Unfortunately, Diogenes Laertius does not report the reason of Demetrius' athetesis [The act or fact of setting aside as spurious; rejection as invalid.], so that we can only speculate. in the case of the Constitution of the Spartans, Demetrius might have had reasons of content: since he probably refuted the tradition of Xenophon's return to Athens from the exile (Diog. Laert. 2.56= fr. 13 Mejer) and presented him as a pro-Spartan (Diog. Laert. 2.52= fr. 12 Mejer), he might not have accepted the criticisms of Spartan society found in chapter 14 of the Constitution of the Spartans as Xenophontic. With Lapini, one might also take into account the possibility that Demetrius did not consider Xenophon as the author of the Constitution of the Spartans because Xenophon himself was not a Spartan.25 This hypothesis is based on a comparison with another fragment of Demetrius in which a certain Hippasus is said to have written a Constitution of the Laconians, being himself a Laconian (Diog. Laert. 8.84= fr. 25 Mejer).26 On the other hand, reasons of style and language might have prompted Demetrius to doubt the authenticity of the Constitution of the Athenians.27 According to Lapini, 'bisogna ammettere che e piuttosto remota la possibilita che un poligrafo del I sec. a.C. abbia divinato ope ingenii la falsa attribuzione dello scritto' [Google translate: it must be admitted that the possibility that a polygraph of the 1st century B.C. has divined ope ingenii the false attribution of the writing];28 however, the analysis of other fragments will show that this possibility cannot be ruled out a priori. All in all, the problem cannot be settled with any certainty. One might thus share Lapini's scepticism and conclude that 'il problema - allo stato attuale delle conoscenze - va dichiarato insolubile' [Google translate: the problem - at the present state of knowledge - must be declared insoluble].29

4 Epimenides' Letter to Solon (fr. 10 Mejer)

Another fragment, reported by Diogenes Laertius in the bios of the Archaic poet and seer Epimenides of Crete, is highly revealing of Demetrius' approach to spurious texts (Diog. Laert. 1.112 = fr. 10 Mejer):30

[x] (scil. [x])(FGrHist / BNJ 457 T 1.112) [x]

A letter of his (scil. of Epimenides) to Solon the lawgiver, containing the constitution that Minos assigned to the Cretans, is in Circulation, too. Demetrius of Magnesia, however, in the books On Poets and Writers with the Same Name, tries to reject the authenticity of the letter as being recent and not written in the Cretan language, but in Attic, and even recent Attic.

The passage is preceded by a section devoted to Epimenides' literary output, where Lobon of Argos is mentioned as a source,31 and is followed by the full quotation of another letter allegedly written by Epimenides to Solon that Diogenes Laertius claims to have personally found.32 The letter, the authenticity of which was rejected by Demetrius, is not mentioned anywhere else in the extant sources. Other letters supposedly exchanged between Epimenides and Solon do not deal with the Cretan constitution. The letter reported by Diogenes Laertius immediately after our fragment, in which Epimenides invites Solon to come to Crete, is the reply to another letter by Solon in which the latter tells how Pisistratus became tyrant of Athens (1.64- 66).33 Diogenes Laertius probably found these two letters in a collection of forged letters which he extensively used in his first book.34

That a forger could ascribe to Epimenides a letter to Solon containing the constitution that Minos gave to the Cretans is no surprise. The ancient sources say that Epimenides came to Athens, invited by Solon and the Athenians, in order to purify the City;35 on that occasion, Epimenides 'paved the way' for Solon's legislation.36 Furthermore, Epimenides, a Cretan by birth,37 was known as the author of prose works on the legislation of Crete and on Minos and Rhadamanthys.38 The letter mentioned by Demetrius may have been based on these works.39

In this case, Diogenes Laertius reports the reason that (rightly) prompted Demetrius to consider the letter as spurious: it was not written in the Cretan dialect, but in recent Attic. The very fact that someone could ascribe to Epimenides a letter written in modern Attic shows that not many people could detect a non-authentic work on the basis of the language.40 To hide the nonauthentic character of the work, however, the second letter reported by Diogenes Laertlus (1.113) was written in literary Doric, with some Cretan elements.41

The distinction between old and recent Attic was not a rare one in antiquity.42 It was used, for example, by the Alexandrian grammarians Aristarchus and Herodianus in their Homeric criticism;43 Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a younger contemporary of Demetrius, distinguished the old Attic of Plato and Thucydides from the ordinary language used by Lysias, Andocides and Critias;44 this old Attic differed but slightly from Ionic.45 For Strabo, too, Ionic was the same as ancient Attic.46 According to other later sources, Hippocrates wrote in old Attic,47 while New Comedy was to be distinguished from Old Comedy because it was written in recent Attic.48 Whatever the precise definition of recent Attic that Demetrius had in mind, he could surely distinguish an Archaic text from one written in Hellenistic koine.49 We cannot but follow him in rejecting the authenticity of what most probably was in fact a spurious letter.50

This fragment shows that Demetrius could combine different criteria to detect a spurious work: linguistic (the letter was written in recent Attic instead of ancient Cretan), geographical (Epimenides was a Cretan and must therefore have used the Cretan language), and chronological (since Epimenides was an archaic figure, he could not have expressed himself in a recent language). In this case, we have clear evidence that Demetrius himself inferred ope ingenii [Google translate: with the help of genius ], on the basis of internal reasons, the inauthenticity of a work reporting a constitution. We cannot therefore exclude the possibility that he did the same with Xenophon's Constitution of the Spartans (and of the Athenians).

5 Dinarchus' Against Demosthenes (fr. 1 Mejer)

The last testimony of Demetrius' interest in the problem of pseudepigraphy is preserved by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a younger contemporary of Demetrius who was active in Rome between 30 and 7 BC.51 In his essay On Dinarchus, which was probably written some years after Demetrius' death,52 Dionysius polemically reports a large section of Demetrius' entry on men called Dinarchus. This essay, one of Dionysius' last rhetorical works, represents the summa of his views on the problem of how to distinguish between an author's genuine and spurious works.53 It consists of three sections: 1) the reconstruction of Dinarchus' life and chronology (2-4); 2) the characterization of his style (5-8); 3) the distinction between genuine and spurious speeches (9-13).54 To establish the genuineness or spuriousness of Dinarchus' speeches, Dionysius systematically exploits the stylistic, artistic, chronological, and biographical/psychological criteria.55

The long quotation from Demetrius is reported with polemical aims at the beginning of the essay in a section in which Dionysius aims at showing the insufficiency of earlier scholarly research and at stressing the importance and originality of his own work. Dionysius refers to Callimachus, the grammarians of Pergamum, and Demetrius. Only the latter, however, is extensively quoted and sharply criticized (Din. 1.2-2.1 = fr. 1 Mejer):56

[x] (scil. [x]) [x] FGrHist / BNJ 465 T 1), [x] (FGrHist / BNJ 399 T 1), [x]

Even Demetrius of Magnesia, who was reputed to be a polymath, speaking about this man (scil. Dinarchus), too, in his treatise On Homonyms and giving the impression that he was going to say something accurate about him, did not meet the expectations. There is no reason not to report his own words. He wrote the following: We have come across four men called Dinarchus: one of them is one of the Attic orators; one collected legends about Crete; one, earlier than the latter two and a Delian by birth, wrote both poetry and history; the fourth composed a work on Homer. I want to treat each of them in turn, and first the orator. Now this man, at least in my opinion, is in no way inferior to Hyperides in charm, so that one could say: 'he might even have surpassed him'. For he uses a convincing argumentation and a variety of figures, and is so persuasive as to convince his audience that facts could not have taken place differently from what he says. And one might regard as naive those who assume that the speech Against Demosthenes was written by him, since it is very far from his style. Yet so much obscurity has prevailed that everyone happened to ignore his other speeches -- somewhat more than 160 -- while this one, which was not written by him, is alone considered his. The diction of Dinarchus properly portrays moral character and arouses emotion; maybe it is inferior to Demosthenes' style only in bitterness and intensity, but is in no way deficient in persuasiveness and propriety'. It is not possible to discover anything precise or even true from this description: for he has shown neither the origin of this man, nor the time in which he lived, nor the place in which he spent his life, but has busied himself only with common and current words and reported a number of speeches that is not consonant with any of those generally admitted. He should have rather done the opposite.

This long passage, as said above, represents an invaluable testimony for our knowledge of Demetrius' work. From our perspective, it is worth noting that Demetrius regarded the speech Against Demosthenes ([x]) as spurious.57 As in the case of Xenophon's Constitution of the Spartans (and of the Athenians) and of Epimenides' letter to Solon, Demetrius is the only authority to make this claim. Fortunately, we know the reason that led Demetrius to the athetesis: the speech was too far from Dinarchus' style.58 It Is also worth noting that Demetrius presents his position as being in contrast with others' opinion: once again, he seems to have contested ope ingenii an attribution which was generally accepted. However, Demetrius' view was followed neither by Dionysius59 nor by modern scholars60, who do not consider the speech Against Demosthenes to be very different in style from the other extant orations (Against Aristagiton and Against Philocles) and regard it therefore as genuine.61

The high number of orations reported by Demetrius (more than 160) also strikes us. This figure, according to Dionysius, was in contrast with the common opinion (the lists provided by Callimachus and the grammarians from Pergamum?). Dionysius himself does not explicitly cite any figure, but gives a full list of all genuine and spurious public and private speeches (Din. 10-13). The spurious speeches, however, cannot be counted anymore, since the text of codex F (the only testimony for the text) breaks off in the course of the enumeration of the spurious private speeches.62 Similarly, on account of possible textual corruptions it is no easy task to establish the exact number of the genuine orations, but the list in its original form probably counted around 60 speeches.63 After Dionysius, ps.-Plutarch (X orat. 850e) and Photius (Bibl. cod. 267 p. 496a-b Bekker) spoke of 64 genuine orations that were attributed to Dinarchus, some of which were handed down, however, under the name of Aristogiton.64 The Suda ([x] 333 s.v. [x]) claims that, even though some authors affirmed that Dinarchus wrote 160 orations, he actually wrote only 60 of them.65 In view of the significant discrepancy between the numbers provided by Demetrius (more than 160) and other authors (around 60), one wonders where Demetrius found this piece of information.66

We can see the traces of a debate. Demetrius attacks his predecessors calling them 'naive' for paying too much attention to a spurious oration, the Against Demosthenes, and for overlooking the other (authentic) orations. Dionysius, in turn, criticizes Demetrius for having provided no biographical information on Dinarchus and for having reported empty words concerning his style and an unreliable number of speeches. In Dionysius' eyes, it was not possible to determine the genuineness or spuriousness of an author's works without the support of a precise biographical framework that could reveal the author's chronology, place(s) of residence, literary activity, and political convictions.

In view of Demetrius' entry on Dinarchus, Dionysius' criticism seems to be justified. However, one should note that the biographical element normally played a primary role in Demetrius' work (frr. 2-9, 11-13, 15-16, 18-24, 27-29, 31 Mejer). In the case of Dinarchus, Demetrius probably did not report any information because he could not find any in the available 'secondary' sources (e.g. Callimachus and the grammarians of Pergamum). This is borne out by the fact that Dionysius had to make first-hand research (based on Dinarchus' speech Against Proxenus and the Attidographer Philochorus) in order to reconstruct the orator's life.67 In addition, we know that Demetrius' criteria for establishing the genuineness or spuriousness of a literary work could represent something more than a generic stylistic comparison: the fragment on Epimenides analyzed above (fr. 10 Mejer) shows that Demetrius could combine chronological, geographical, and linguistic criteria. If our knowledge of Demetrius exclusively depended on Dionysius, the consequence would be a negative and unfair picture of Demetrius' work and qualities as a literary critic.

In view of Demetrius' fame as an erudite and of his interest in the problem of pseudepigraphy, I argue that Dionysius' polemic was not limited to the mere content of Demetrius' entry on Dinarchus. The scope and position of the textual quotation and the length of Dionysius' critical remarks may best be explained by assuming that Dionysius wanted to stress the differences, rather than the continuity, between his own work and that of Demetrius, an influential writer and a respected authority whose opinions in the field of literary criticism were probably well known in 1st. century BC Rome.68 A few years before Dionysius, Demetrius had concerned himself with the problem of pseudepigraphy and had written about the life and literary output of Attic orators and writers, such as Dinarchus, Demosthenes (frr. 2-5 Mejer), Isaeus (fr. 6 Mejer), and Xenophon (frr. 12-14 Mejer).69 In On Dinarchus, we may conclude, Dionysius sharply criticized his predecessor with the aim of enhancing his role as a literary critic, thereby presenting himself as the inventor of a systematic method for detecting spurious works.

6 Conclusions

The above analysis has shown that detecting (supposedly) spurious works must have been an important aspect of Demetrius' work. In his criticism, Demetrius does not appear to have followed others' opinions, but to have developed his own critical method. He is the only known authority to have considered Xenophon's Constitution of the Spartans (and perhaps also the Constitution of the Athenians), Epimenides' letter to Solon, and Dinarchus' Against Demosthenes as spurious. In the latter case, he even attacked his predecessors for considering Dinarchus' oration authentic. The fact that he himself regarded as spurious some texts that were usually considered genuine should prevent us from considering Demetrius a mere erudite compiler.70 Demetrius not only employed stylistic, but also chronological, geographical, and linguistic criteria, thus revealing a conscious, critical approach that in a way seems to have served as a prelude to the systematic literary criticism of his younger contemporary Dionysius of Halicarnassus.

_______________

Notes:

1 I would like to thank Prof. Stefan Schorn for reading and discussing with me the content of this article.

2 The fragments of Demetrius of Magnesia have been edited by Sheurleer (1858) and Mejer (1981). On Demetrius, cf. also Schwartz (1901), Gigante (1984), Aronadio (1990), Mejer (1994) and Ascheri (2013). Besides On Poets and Writers with the Same Name ([x]) Demetrius penned a work On Concord ([x]: T 1a-d Mejer) and On Cities with the Same Name ([x]: for a list of passages, see Mejer [1981)449 n. 5). In this article, I only take into account those passages that are explicitly ascribed to Demetrius by the citing authors. The question of whether all the lists of homonyms reported by Diogenes Laertius at the end of numerous bioi of philosophers derive from Demetrius is still open: stotus quaestionis in Mejer (1981) 450-1; Aronadio (1990) 235-7; Ascheri (2013). I am currently preparing a new edition of and a commentary on the fragments of Demetrius for the series Die Fragmente der Griechischen Historiker Continued Part IV.

3 See e.g. Plut. Arist. 1.6= Dem. Phal. fr.102 Stork-Ophuijsen-Dorandi= Panaet. T 153 Alessi; Diog. Laert. 7.163= Panaet. T 151 Alessi = Sosicr. Hist. fr.12 Giannattasio Andria; Suet. Gramm. 1; Quint. Inst. 3.5.14; Elias in Cat. p. 128, 9-18 Busse; Phlp. in Cat. p. 7, 16-19 Busse, Cf. Speyer (1971) 37-39; D'Ippolito (2000) 311; Speciale (2000) 513-4.

4 No specific studies, as far as I know, have dealt with this aspect of Demetrius' work. Scattered references to Demetrius' criticism can be found in Speyer (1971) 37-39, 118, 124-6.

5 In the Imperial period, a similar work [x] was authored by a certain Agresphon/Agreophon (FGrHist 1081). This obscure writer is only mentioned in an entry of the Suda that ascribes him a book [x]: see Suda a 3421, s.v. [x] = Agreophon, FGrHist 1081:[x]. Being cited as a source on a philosopher called Apollonius who supposedly lived under Hadrian (117-138 AD), he is generally considered to have lived in the 2nd or 3rd century AD: see Nietzsche (1869) 227 (2nd/3rd century AD); Cronert (1906) 134 (2nd century AD); Meier (1981) 450 (2nd century AD); Radicke on FGrHist 1081 (3rd/4th century AD). The hypothesis that his work was based on or was a continuation of that of Demetrius is neither contradicted nor supported by the evidence. For this hypothesis, see Nietzsche (1869) 227-8; Cronert (1906) 134; Radicke on FGrHist 1081.

6 From three letters by Cicero to Atticus (49 BC), we know that Cicero was familiar with Demetrius' work On Concord, which was probably dedicated to Atticus (T 1a-d Mejer). Furthermore, Cicero seems to have used Demetrius' work On Poets and Writers with the Same Name to write the Tusculanae disputatianes and De natura deorum in 45 BC (Tusc. 5.36.104 recalls fr.29 Meier; Nat D. 1.26.72 recalls fr.31 Meier). In addition, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who was active in Rome between 30 and 7 BC. says that he was reputed to be a polymath ([x], cf, fr.1 Mejer). As for Demetrius' chronology, the terminus ante quem is provided by the fact that a work of his (probably On Concord or On Poets and Writers with the Same Name) had already been published by 55 BC (T 1d Meier). The terminus post quem is given by the mention of Zeno of Sidon, who became head of the Epicurean school at Athens around 110/5 BC and was old when Cicero and Atticus attended his lectures in 79/8 BC (fr. 7 Meier). The way in which Dionysius of Halicarnassus refers to Demetrius in fr.1 Mejer ([x]) implies that the latter was already dead when the former wrote his book On Dinarchus.

7 See e.g. Mejer (1981) 451; Aronadio (1990) 238; Ascheri (2013).

8 For this influential assumption, see Maass (1880) 24-27.

9 See Duhrsen (2005) 262-3.

10 See Scheurleer (1858) 8; Nietzsche (1869) 183; Blum (1991) 197, 201; Jacob (2000) 97.

11 Cf. Mejer (1981) 451.

12 Ed. Dorandi (2013).

13 The hypothesis that the entire list derives from Demetrius was put forward by von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (1881) 334; Roquette (1884) 34; Munscher (1920) 106-7; Mejer (1981) 460; Canfora (2004) 245 n. 53. The fragment of Demetrius Is followed by the famous remark about the 'edition' of Thucydides' books by Xenophon. This sentence has been considered part of Demetrius' fragment by Adcock (1963) 137-8 and Canfora (1970) 73 n. 24; (2004) 210-1, 245. However, this assumption is uncertain, since the passage is introduced by [x]: cf. Gomme et al. (1945-81) V 438; Natalicchio (1992) 87 n. 57.

14 This argument was first proposed by Diels in Pierleoni (1905) 1. See also Treu (1967) 1928-82; Schutrumpf (2002) 641; Ramirez Vidal (2005) xxxiv-lv; Marr/Rhodes (2008) 6-12. However, some scholars still think that the author might be Xenophon: see Fontana (1968) 84- 102; Sordi (2002) 17-24; (2005) 19-22; Serra (2012-3) 161-89. Others think that the work was written in the 4th century BC: see Roscalla (1995) 105-30; Hornblower (2000) 363-84. For a status quaestionis [Google translate: the status of the problem], see Searzot (2011) 3-24; Tuci (2011) 29-71; Lenfant (2017) iv-xxvii. The Constitution a/the Spartans is nowadays ascribed to Xenophon: see Breitenbach (1967) 1746-53; Ollier (1979) vii-xi; Luppino Manes (1988) 19-31; Rebenich (1998) 14-35; Schutrumpf (2002) 638; Lipka (2002) 5-9. Its authenticity was refuted by Chrimes (1948) 17-30 and Lana (1992) 17-26.

15 On the manuscripts transmitting the Constitution of the Athenians, see Lenfant (2017) cxxiii-cxxxvii.

16 This view was first put forward by Casaubon: see Treu (1967) 1931. See also Roquette (1884) 34; Frisch (1942) 38-39; Masqueray (1964) xiii n. 1; Lenfant (2017) xvii. Cf. also Lapini (1991) 21- 22.

17 Xen. Ath. pol. 1.1: [x]. See Pierleoni (1905) 1; Richards (1907) 55; Sordi (2002) 18; Marr/Rhodes (2008) 60; Weber (2010) 65. Status quaestionis in Lenfant (2017) 24-25.

18 See Kalinka (1913) 18-20; Munscher (1920) 106-7; Masqueray (1964) xiii; Treu (1967) 1930-2; Ollier (1979) vii-viii; Lipka (2002) 6-7.

19 See Diels in Pierleoni (1905) 1; Frisch (1942) 38-39; Gigante (1953) 81- 82; Natalicchio (1992) 86 n. 56.

20 See Roquette (1884) 34; Frisch (1942) 38-39; Lapini (1991) 21-22; Sordi (2002) 17-18; Humble (2004) 217; Ramirez Vidal (2005) xxxv-xxxvi; Marr/Rhodes (2008) 6-7; Serra (2012-3) 161-2; Lenfant (2017) xvii.

21 As a book title, politeia is always found either alone or with the specification of a single land or people: see Diog. Laert. 1.61: [x]; 1.112: [x]; 3.60: [x]; 4.12: [x] 5.22: [x]: 5.27: [x]; 5,43: [x]: 5.45: [x]: 5.81: [x]: 6.16: [x]; 6.80: [x]; 7.4: [x]; 7.36: [x]; 7.178:[x]; 8.84: [x]; 9.55: [x]; 7.34: [x]; 8.13: [x].

22 Lenfant (2017) 25 rightly notes that the Apology of Socrates and the Oeconomicus also have the particle [x] in the first sentence, which might be regarded as a feature of oral style.

23 As rightly remarked by Lapini (1991) 21. If the Constitution of the Athenians was actually mentioned by Demetrius, this fragment would be the most ancient testimony for the existence and the attribution of the text to Xenophon. Scholars think that the text (if non authentic) was attributed to Xenophon either soon after his death or by the Alexandrian scholars: see Kalinka (1913) 18-20; Munscher (1920) 106-7; Frisch (1942) 38-39; Gigante (1953) 81-82; Marr/Rhodes (2008) 6-7; Serra (2012-3) 169.

24 Another solution has been proposed by Serra (2012-3) 161-2: 'E curioso che Demetria, se la citazione di Diogene e fedele, unifichi le due Costitulioni (solo se e cosi, il suo dubbio colpisce la nostra Costituziane), ma anche inverta - si direbbe normalizzi -l'ordine in cui esse compaiono nella tradizione diretta ... Quest'ordine non 'classico' ha un senso solo se pensiamo alla posizione del 'cavaliere' Senofonte, per il quale la costituzione spartana verrebbe idealmente prima di quella ateniese [ ...]' [Google translate: And curious that Demetria, if the quotation of Diogenes is faithful, unifies them two Constitutions (only if so, his doubt affects our Constitutions), but also reverses - one would say normalizes - the order in which they appear in direct tradition ... This non-'classical' order it only makes sense if we think about the position of the 'knight' Xenophon, for whom the Spartan constitution would ideally come before the Athenian one [...]].

25 See Lapini (1991) 22.

26 Diog. Laert. 8.84 = fr. 25 Mejer: [x] (scil.[x]) (18 A 1 D.-K.) [x]; (FGrHist / BNJ 589 T 1) [x].

27 See e.g. Richards (1907) 55-56. Cf. Lapini (1997) 9, who speaks of an 'irrimediabile diversita dello stile edel pensiero' [Google translate: irremediable diversity of style and thought]. See also Lapini (1998) 118: 'Se si rida voce alla traditio e si restituisce l'opera a Senofonte, come si spiegano gli ionismi dell'anonimo?' [Google translate: If one laughs at the traditio and returns the work to Xenophon, how do you explain the ionisms of the anonymous?]. On the Ionisms, see Caballero Lopez (1997) 8-27. As regards the Constitution of the Spartans, stylistic evaluations of modern scholars vary: see e.g. Kohler (1896) 376: 'Die [x], was die Klarheit der Gedanken und des Ausdrucks anlangt, hinter anderen Schriften Xenophon's zuruck; dieser nicht zu verkennende Unterschied muss es gewesen sein, welcher den Kritiker Dionysios [sic] Magnes bewogen hatte, die Schrift Xenophon abzusprechen' [Google translate: The [x] what the in clarity of thought and expression, behind others Xenophon's writings back; this unmistakable one It must have been a difference which made the critic Dionysios [sic] had persuaded Magnes to deny the writing Xenophon.]; Richards (1907) 55: 'in the case of the R.L. there is no reason on grounds of style for denying X.'s authorship'; Ollier (1979) viii: 'On peut affirmer que jamais ouvrage ne porta mieux que celui-la la signature de son auteur' [Google translate: We can affirm that never work carried better than this one the signature of its author]; Lipka (2002) 7: 'Many arguments could be put forward to explain why Demetrius doubted X.'s authorship, starting from the work's stylistic simplicity, unevenness, and linguistic obscurity'.

28 Lapini (1991) 21-22.

29 Lapini (1991) 22.

30 Ed. Dorandi (2013).

31 Diog. Laert. 1.111-2 = Lobo Argivus fr. 16 Cronert = fr. 8 Garulli.

32 Dlog. Laert. 1.112-3: [x].

33 Cf. Gigante (2001) 19. See also Suda E 2471, s.v. [x]; (FGrHist I BNJ 457 T 2 = 3 A 1 D.- K. = T 2 Bernabe): [x].

34 See Demoulin (1901) 116, 133; Gigante (2001) 10. According to Duhrsen (1994). these letters were part of a Briefroman. Cf. also Portulas (2002) 219-20; Gomez (2002); Holzberg (2006) 31.

35 See e.g. Plut. Sal. 12 (FGrHist / BNJ 457 T 4c = 4 A 1 D.-K. = T 3 Bernabe); Diog. Laert. l.110-1.

36 Plut. Sol. 12.8 (FGrHist / BNJ 457 T 4c = 4 A 1 D.-K. = T 3 Bernabe): [x].

37 On Epimenides' link with Crete, see especially Tortorelli Ghidini (2000) and Tortorelli Ghidini (2001); Mele (2001).

38 Diog. Laert. 1.112 = Lobo Argivus fr. 16 Cronert = fr. 8 Garulli: [x]. The list of Epimenides' works probably comes from Lobon of Argos: see Demoulin (1901) 74-75; West (1983) 52; Gigante (2001) 21; Mele (2001) 231-232; Toye on BNJ 457 T 1.

39 See Demoulin (1901) 133; Mele (2001) 231-2. According to West (1983) 52 and Toye on BNJ 457 T 1, the two works may even have been identical. Eratosth. Cat. 27 = Epimenid., FGrHist / BNJ 457 T 9 also mentions a work called Kretika: see West (1983) 52; Toye on BNJ 457 T 1.

40 For a similar case, see Paus. 2.37.2-3. Cf. also Ath. 13.72.599c-d = Chamael. fr. 28 Martano. For a Similar kind of criticism by Eratosthenes, see Blum (1991) 241, referring to Strecker (1884) 16.

41 See Cassio (2000) 153: 'Diogene Laerzio quindi riporta per esteso (1.113) una pretesa lettera di Epimenide a Solone scritta in un dorico letterario con alcune caratteristiche che potrebbero essere cretesi (passaggio [e]> [ i] in [x]) accanto altre che non lo sono affatto (p. es. dativi in -[x] in [x])' [Google translate: Diogenes Laertius then reports in full (1.113) an alleged letter from Epimenides to Solon written in a Doric literary with some characteristics that could be Cretan (step [e]> [i] in [x]) alongside others that are not at all (e.g. datives in - [x] in [x])]. See also Demoulin (1901) 133; Gomez (2002) 201-2. According to Duhrsen (1994) 86, Diogenes Laertius regarded this letter as genuine because of the language.

42 Cf. Cassio (1993) 36 n. 2 and Cassio (2000) 154 n. 1, with literature.

43 See Stephan (1889) 25-26; Pfeiffer (1968) 228; Cassio (1993) 36 n. 2; Cassio (2000) 154 n. 1.

44 Dion. Hal. Lys. 2: [x].

45 Dion. Hal. Thuc. 23: [x].

46 Strab. 8.1.2 p. 333C:[x]).

47 Gal. vol. XVIII B p. 322 Kuhn.

48 Prolegomena de Comoedia V 5, XI b 53 Koster.

49 Cassio (2000) 154; Mele (2001) 231-2.

50 Demoulin (1901) 116; Mejer (1981) 458.

51 We do not know the absolute chronology of this work, but scholars usually assume that Dionysius' rhetorical works were written in Rome between 30 and 7 BC and that the book On Dinarchus was one of his last treatises, if not the very last: see Bonner (1939) 37-38; Pavano (1942) 335-6, 353; Untersteiner (1959) 81-82; Marenghi (1969) 4, 11; Shoemaker (1971) 393-4; Aujac (1992) 104; Galan Vioque/Guerrero (2001) 133.

52 This is revealed by the words [x] at the beginning of the passage quoted below: see Scheurleer (1858) 3; Mejer (1981) 449; Duhrsen (2005) 249; Ascheri (2013).

53 Dionysius has been considered by Untersteiner (1959) the 'fondatore della critica pseudepigrafica' [Google translate: founder of pseudepigraphic criticism].

54 Manuscript F (Laurentianus LIX 15), the only testimony of the text, breaks off in the course of the enumeration of Dinarchus' spurious private speeches.

55 On these criteria, see especially Untersteiner (1959); Marenghi (1970) 36-42; D'Ippolito (2000) 297.

56 Ed. Aujac (1992). The conjecture [x], not reported by Aujac, was put forward by Radermacher in Usener/Radermacher (1899).

57 Demetrius' statement does not imply that other scholars attributed only the oration Against Demosthenes to Dinarchus, but rather that the speech was by far the most famous: see Shoemaker (1968) 65-66. Demetrius was probably thinking of Dinarchus' [x] (Dion. Hal. Din. 10.27) and not of [x], which is said by Dionysius to be spurious (Dion. Hal. Din. 11.18), In fact. it was because of the speeches written on the occasion of the Harpalus affair that Dinarchus was well known: cf. Shoemaker (1968) 65- 66.

58 The style (charakter) of an author was commonly involved in questions of authenticity: see Ritchie (1964) 11-15; Speyer (1971) 124-5; Hunter (2002) 94-95; Fries (2014) 22.

59 See Dion. Hal. Din. 10.27.

60 See e.g. Schaefer (1885-1887) III 339-40; Blass (1887-1898) III/2, 331; Marenghi (1970) 40, 70 n. 22; Worthington (1992) 12 n. 28; Aujac (1992) 166 n. 3.

61 See Marenghi (1970) 70 n. 22; Mejer (1981) 454.

62 Dion. Hal. Din. 13.8. There are 27 extant spurious titles in Dionysius' list: see Shoemaker (1968) 68-69.

63 Scholars put forward numbers varying from 59 to 64: see Shoemaker (1968) 78. The list printed by Shoemaker, followed by Worthington (1992) 11, counts 61 speeches, with 29 genuine public and 32 genuine private speeches. According to Galan Vioque/Guerrero (2001) 137, Dionysius considered 28 public and 31 private speeches as genuine.

64 [Plut.] X orat. 850e: [x]; Phot. Bibl. cod. 267 p. 496a- b Bekker: [x].

65 Suda [x] 333, s.v. [x]. A family of six Mediaeval manuscripts from the 10th to the 15th century reports the figure of 410 or 400 orations, which is clearly incorrect: see Shoemaker (1968) 84-86.

66 Cf. Worthington (1992) 11. According to Nietzsche (1869) 183, Demetrius added the number of orations he found in the Alexandrian Pinakes to the figure he found in the Pergamenian catalogues.

67 Dion. Hal. Din. 3.1 . Other later sources on the orator's life are [Plut.] X orat. 850c-e and Phot. Bibl. cod. 267 p. 496a-b Bekker. Suda [x] 333, s.v. [x] confuses the orator with a homonymous Corinthian politician. On Dinarchus' life and biographical sources, see especially Shoemaker (1968) 8-60; Worthington (1992) 3-12.

68 This procedure is typical in historiography: cf. e.g. Schepens (2000) 11-12.

69 On Demetrius' Atticist attitude, see especially Schwartz (1901) 2815, followed by Mejer (1981) 452; Gigante (1984) 101. See also Duhrsen (2005) 260-2, 265.

70 Of course, our knowledge of Demetrius is completely dependent upon the citing authors; therefore, we should not conclude that Demetrius always contradicted the common opinion.