directed by Barry Avrich

Documentary Trailer Now on Netflix

Feb 23, 2021

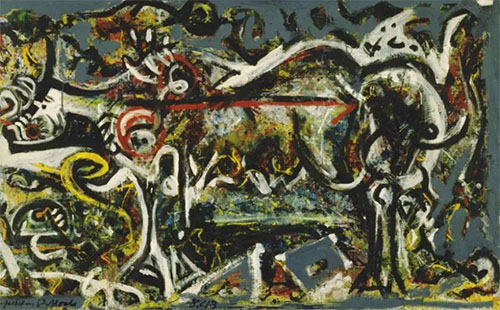

Filmmaker Barry Avrich (David Foster: Off the Record, Prosecuting Evil) explores how one of the most respected art galleries in New York City became the center of the largest art fraud in American history and was ultimately forced to close after 165 years. Knoedler & Company, under its president, Ann Freedman, made millions selling previously unseen works by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, and others that had supposedly come from a secret collection. But when her prestigious clients discovered they had purchased fakes, the scandal rocked the art world. Avrich secured unprecedented access to Freedman, her clients and other key players for the documentary.

*****************************

Pei-Shen Qian Now: Where Is the Accused Knoedler Gallery Art Forger Today in 2021?

by Alyssa Choiniere

heavy.com

Updated Feb 26, 2021 at 9:57am

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

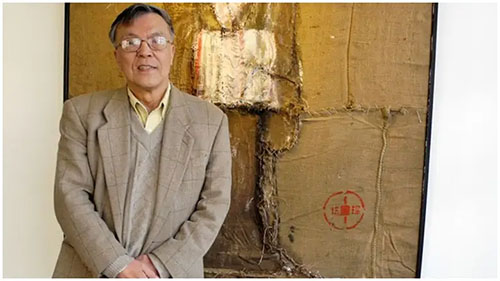

Pei-Shen Qian was accused of forging art by famous artists including Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

Pei-Shen Qian was a struggling Times Square artist when he was approached by Jose Carlos in the late 1980s, asking him if he could replicate Jackson Pollock. He said he could, and soon found himself at the center of an $80.7 million art scandal.

Qian was indicted, but moved back to China where he remains today and escaped prosecution. In 2014, he was indicted on charges of wire fraud, conspiracy to commit wire fraud and lying to the FBI, according to his indictment. He was 75 at the time of his indictment. He could face up to 45 years in prison if he was convicted of the charges. Now in his early 80s, he continues to paint in a small studio outside Shanghai, but no longer sells his art, his wife told documentary filmmakers.

Qian was one of the multifaceted characters at the center of Director Barry Avrich’s “Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art.” It’s release was delayed due to COVID-19 and it was released on Netflix Tuesday, February 23, 2021.

Here’s what you need to know:

Qian Claims He Had No Plans to Con Anyone & Did Not Make Significant Money in the Art Fraud Scheme

Elizabeth Klinck

@eklinck·Follow

Good Review: 'Made You Look: A True Story about Fake Art,' a fascinating $80 million con....proud to have worked on this one with a terrific team ! Now on @Netflix @melbarentgroup #documentary

latimes.com

Review: 'Made You Look: A True Story about Fake Art,' a fascinating $80 million con

The Netflix documentary “Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art” depicts those involved in the largest art fraud in American history.

9:21 PM · Feb 23, 2021

In China, Qian was a successful and classically trained artist and a professor. In the United States, he tried to make ends meet painting on Manhattan street corners and through construction work. He thoroughly studied the works of famous artists in art class and beyond. His friend, Hongtu Zhang, told filmmakers on “Made You Look” that replicating famous works of art is a common practice in Chinese art.

“Nothing from your heart. You only copy others art,” he said.

“He is good. He had some talent,” he added.

Qian claimed innocence in a December 2013 interview with Bloomberg News in Shanghai, China. He said he was an innocent victim of a “very big misunderstanding” and had no intention to pass off his imitations for genuine works of art by famous painters.

“I made a knife to cut fruit,” he said at the time. “But if others use it to kill, blaming me is unfair.”

Prosecutors said in his charging documents that Qian was aware of the scheme, and participated in it with art dealers Jose Carlos and Jesus Angel Bergantinos Diaz, who were brothers, and Diaz’s girlfriend at the time, Glafira Rosales. The indictment said he would use processes to age the paintings such as dyeing them with tea bags, using a blow dryer on them or exposing them to the elements. It further said he would forge the signatures of famous artists on the canvases.

Qian was initially paid a few hundred dollars for each painting, but after learning his paintings were selling for much more, he demanded a higher price and received about $7,000 per painting.

Qian Is Now Laying Low in Shanghai, Avoiding Media Attention & Continues to Paint in a Small Studio But No Longer Sells His Art

“Made You Look” filmmakers tracked down Qian in China. He had aged and walked with a cane. He identified himself, but was not interviewed on film.

His wife politely declined an interview.

“He is old now. He doesn’t want to be interviewed,” she said in a translation. “He is painting for himself and not selling his art anymore.”

Qian moved to a neighborhood outside Shanghai and opened a small art studio. There, he spoke to ABC News in 2014 and said he was not a knowing participant in the fraud scheme.

“My intent wasn’t for my fake paintings to be sold as the real thing,” he said in a translated interview. “They were just copies that can be put up in your home if you like it.”

Dr. Colette Loll

@ArtFraudInsight·Follow

Made You Look, a documentary about the Knoedler scandal is now available on Netflix! I am incredibly amused to see the film producers have used an image of me taken with a fake Knoedler Rothko as a film promo #RealorFake

7:33 AM · Feb 24, 2021

He further pointed to his small fee received for paintings that often sold for millions of dollars apiece.

“If you look at my bank account, you’ll see there’s no income. I’m still a poor artist. You think I could be involved with this?” he said.

“These copies were just supposed to mimic them at a basic level, so I was very shocked that people mixed them up,” he said.

The Guardian reported shortly after Qian’s indictment in 2014 there was little chance of extraditing him from China to face prosecution. He has dual citizenship in both China and the United States.

“There is almost no chance that China would turn their own citizen over,” Professor Julian Ku, an expert on China and international law at Hofstra University, told The Guardian. “They generally don’t have a policy of co-operating, and don’t have any reason to turn anyone over, because the US won’t turn anyone over to China.”

*****************************

What Puts Soul in a Masterpiece?

by Ken Johnson

The New York Times

Dec. 30, 2013

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

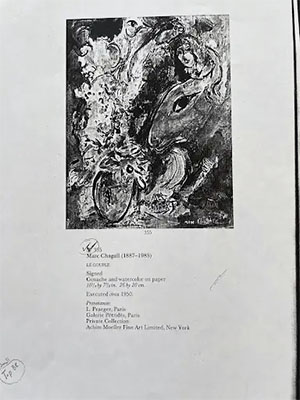

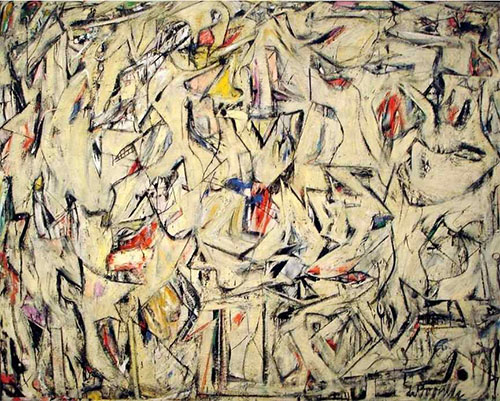

A painting by Pei-Shen Qian shown in a 2006 retrospective in China. Credit...BB Gallery, Shanghai

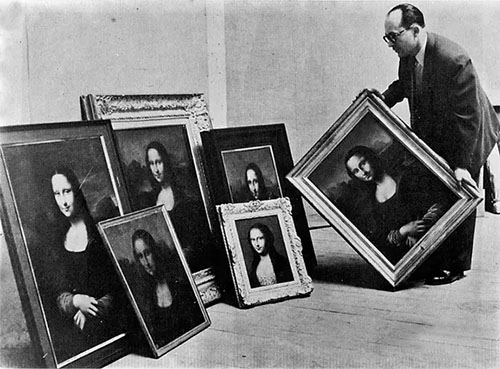

Recently, The Art Newspaper reported that Pei-Shen Qian had some of his paintings included in a group exhibition in a Shanghai gallery last spring. Scandal-following readers will recognize the name as that of a Chinese artist, once living in Queens, whose imitations of paintings by Pollock, de Kooning and other Abstract Expressionists were sold as real for millions of dollars by the New York gallery Knoedler & Company, now defunct.

In China, where he regularly returned for extended visits after moving to New York in 1981, Mr. Qian, 73, is known for his own paintings. He first emerged as an artist in the late 1970s, one of a group producing and exhibiting abstract work, which Cultural Revolution authorities deemed bourgeois and decadent. In 2006, he had a 25-year retrospective at the BB Gallery in Shanghai. Some of his works are posted on various websites. Naturally, you wonder, are Mr. Qian’s own paintings any good? Would I like to review them, my editor asked?

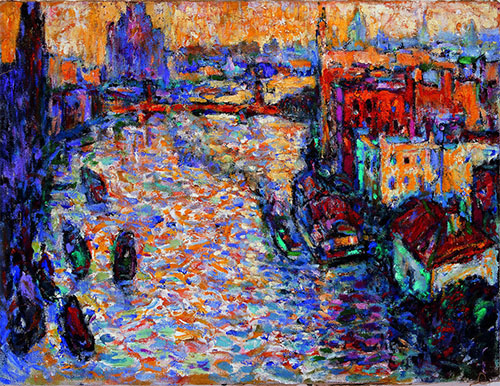

I can’t, in good conscience, review works I’m able to see only online. But I can say, provisionally, that I’m struck by the absence of any singular vision among his pieces. My laptop screen shows earnestly made, colorful landscapes and cityscapes that evoke early Post-Impressionist paintings by Matisse and André Derain. Some mixed-media works represent faceless women in a style that hybridizes classical Chinese painting and early-20th-century Cubism, made on what appear to be surfaces of patched-together burlap.

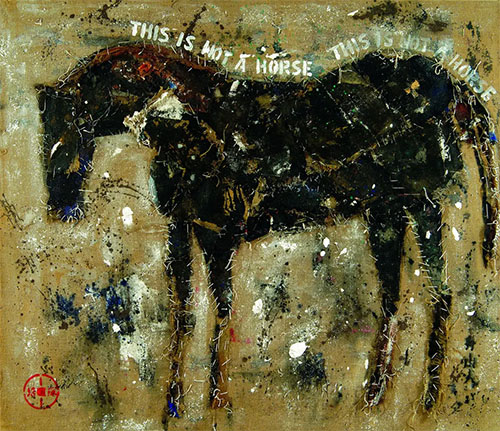

A picture of a horse including stenciled white letters spelling “This is not a horse” echoes Magritte’s painting of a pipe captioned “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”). Several paintings are of large, generalized heads rendered in a soupy, Expressionist manner.

Personal works by Pei-Shen Qian were shown at the BB Gallery in Shanghai in 2006 as part of a 25-year retrospective of his artistic career. Pictured is an example from that show. Credit...BB Gallery, Shanghai

Nostalgia seems to be the unifying mood of Mr. Qian’s paintings. That, alone, is remarkable, because the European works that evidently inspired him were revolutionary in their time. The kind of painting he emulates in his own work and the Abstract Expressionist paintings on which he has based his imitations both depended on originality and expressive authenticity, as opposed to academic tradition and technical polish. Yet Mr. Qian seems to be the opposite of original.

I suppose he works in styles he loves without worrying about whether they’re outmoded. Unless there’s something going on that can’t be seen in online images, it seems unlikely that Mr. Qian’s personal paintings will cause anything like the stir his imitations have.

That is disappointing but not surprising. I like the fantasy of the unjustly neglected genius who gets revenge on the art world by making expert-fooling works that mimic the style of famous painters. (Mr. Qian has not been charged with any crime related to the scandal.) But I think it more likely that the typical copyist will be relatively lacking in originality. Copyists need to be able to muffle their own creative selves, and if those creative selves are weak, all the better.

What they need in abundance are technical knowledge and skill. It’s not easy to make forgeries. However hard it was for Barnett Newman to produce one of his zip paintings, making a convincing fake Newman — reverse-engineering it, in effect, as well as making it look appropriately aged — surely will be more demanding technically, if not spiritually.

A painting by Pei-Shen Qian. Credit...BB Gallery, Shanghai

Mr. Qian’s creations, which were not copies of actual works but in the style of famous artists, intrigue me more than his personal work, but not for technical reasons. They raise interesting philosophical questions: Why should we value a painting known to be made by a certain esteemed artist more than a painting that is phony but is nevertheless practically indistinguishable from the authentic work? Why is a real Motherwell worth millions of dollars more than a fake one that looks just as good?

The dynamics of supply and demand are what make any artwork worth its price. Real things are worth more than fake ones simply because they are more rare.

Demand is more fluid and variable than supply because it’s influenced by vagaries of taste and fashion; it’s less rational. Demand is partly animated by some quasi-magical beliefs about art and artists, like the idea that there’s a sort of organic connection between artists and the things they make. The artist’s soul is somehow in the work, and because great artists are supposed to have great souls, there’s more soul in their creations than there is in mediocre efforts.

From there, it’s a short leap of faith to the belief that market valuation reflects soul value — not perfectly, but at least roughly and in the long term. The most expensive works have the most soul. That’s why, if you can afford it, you buy the real Motherwell. There’s no magic, no soul, in fake artworks, so they are worth less, if not completely worthless.

A work by Pei-Shen Qian. Credit...BB Gallery, Shanghai

Mr. Qian told Bloomberg Businessweek that he thought he was being commissioned to make paintings for art lovers who could not afford the genuine works but were willing to buy imitations. I don’t know if such people really exist, but Mr. Qian seems to have thought they did. He didn’t imagine that there was anything ethically or legally wrong with what he was doing. He was a copyist but not a forger, if intention to deceive is part of the definition of a forger.

Mr. Qian told a reporter that he was shocked to learn what art dealers actually did with his simulations, for which they paid him a few thousand dollars per piece. He also said that he thought that it was impossible to make fakes that would be undetectable as such. Apparently, he didn’t even try: Signs of age and forged signatures, prosecutors say, were added by the man who ordered the paintings, the art dealer Jose Carlos Bergantiños Diaz.

The art market depends on the belief, expressed by Mr. Qian, that fakes can always be detected. Collective wisdom supposes that the forgery must, at some level, betray itself, and much connoisseurial scrutiny and forensic investigation goes into ensuring that as many deceptions as possible are ultimately exposed. Forgeries flooding the market unchecked would throw relations between supply and demand out of whack, causing economic chaos.

That’s what makes stories like that of Mr. Qian and the people he worked for so compelling. They are players in contemporary morality tales, myth-saturated chronicles about the upset and the restoration of order in the capitalist universe. It would make a more thrilling story if Mr. Qian turned out to be a great artist in his own right. Judging from what we can see online, however, that happy ending isn’t going to happen.

Wouldn’t it be great, however, if we could see an exhibition of all his fake paintings?

Correction: Jan. 2, 2014: A critic’s notebook article on Tuesday about Pei-Shen Qian, a Chinese artist whose imitations of paintings by Abstract Expressionists were sold as real for millions of dollars, referred incorrectly to him at several points. He is Mr. Qian, not Mr. Pei-Shen. (He has not been charged with any crime in connection with the case.)

A version of this article appears in print on Dec. 31, 2013, Section C, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: What Puts Soul in a Masterpiece?

Inside the World of Forgery and Fake Art

• Archival detective work helped prove that “one of the great treasures” in the University of Michigan Library — a Galileo manuscript — is the work of a prolific early-20th-century forger.

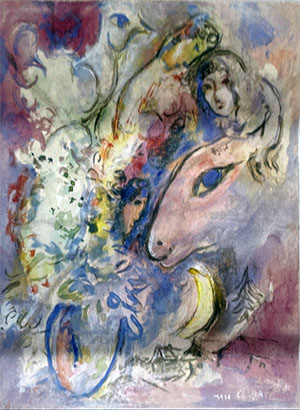

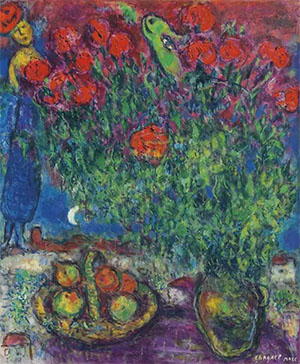

• An art collector paid $90,000 for a Marc Chagall painting at a Sotheby’s auction in 1994. Now an expert panel in France wants to destroy it as a fake.

• For decades, the owner of a Manhattan gallery mass-produced objects that he passed off as ancient artifacts. Then he sold his fake antiquities to undercover federal investigators.

• What happens when a work of art is discredited? Experts say many have second lives that resemble their first, as they resurface on the market again and again.

• With high-tech instruments and the periodic table, a Sotheby’s “detective” digs deep to discover what’s real and what’s not.

***********************

New York Art Con Busted

by Ana Bambic

Widewalls

May 2, 2014

After he was accused by the US authorities of having gained around $33million after forging artwork by such luminaries as Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, Pei-Shen Qian fled to his homeland, China, avoiding the anticipated imprisonment of 45 years. This Chinese painter was indicted on Monday, as the creative link in the wire deception organized by two brothers - gallerists from Spain, who sold the bogus works Qian was producing for enormous prices to American and European art collectors. Apparently, the trio had an elaborated scheme functioning for years, through which they accumulated an incredible wealth, at the expense of galleries and art aficionados they swindled.

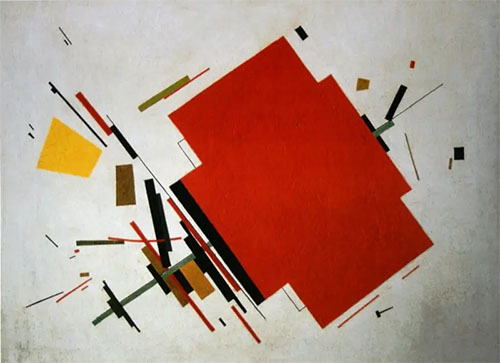

Robert Motherwell, a work Qian allegedly forged

The International Art Swindle

Although the two Spanish gallerists, Jose Carlos and Jesus Angel Bergantinos Diaz, are arrested and waiting extradition to Spain, Pei-Shen Qian is likely to escape the American judicial system, since China is not likely to cooperate in extradition process. Glafira Rosales, an art dealer and a former girlfriend of one of the Diaz brothers, participated in the international scheme as well, helping the party place their forged pieces in Europe.

Wilem de Kooning - Excavation

Pei-Shen Qian: The Art Forger

In an interview of last year, Qian claimed he was the victim of the fraud as well, stating that even if he painted the works, he did not participate in the sales, which, according to him, is enough to have him exempted from the indictment. However, the case documentation clearly points he participated willingly in the entire con.

Qian was a painter in China, where he worked creating portraits of Mao Tse Tung for Chinese schools and offices. He came to the USA in 1981 as a student, and remained in the country. He lived in New York, and was “discovered” by Jose Carlos later in the 1980s while he was easel painting on a Manhattan street corner. He started making copies of Keith Haring and Jean Michel Basquiat.

The Chinese foger was very active in the production of signed fakes in the early 1990s, painted on old canvases and with old paint, supplied by the gallerists, or staining newer canvases with tea bags to make them appear older. The range of artists Qian forged slowly expanded to Modernists and Abstract Expressionists.

At first, the fraudulent gallerists paid Qian several hundred dollars per painting, but soon he started demanding more money and in the late 2000s, he was receiving as much as $7,000 per painting, for regular “work”. When the more complex deceits against acclaimed New York galleries were planned, much higher sums, up to several million dollars per painting, were in question.

Justice for All?

The Bergantinos Diaz brothers and Rosales were all arrested, and Rosales pleaded guilty to nine criminal charges last September, facing up to 99 years of confinement.

Jose Carlos is facing around 114 years in prison, and his brother is looking at a sentence of as much as 80 years. Their illegally gained property was forfeited to the authorities, while their criminal careers were rightfully stopped. The only figure who seems to have escaped, perhaps permanently, is Pei-Shen Qian, due to China’s and the US unwillingness to cooperate on this (and similar) matter. Qian has dual citizenship and neither of the countries was ever known to handover their citizens to be persecuted abroad. He will not be able to travel to any countries with which the United States have signed the extradition treaty, which is the Americas, most of Europe and Hong Kong, but there is still a large chunk of the planet for this Chinese conman to move freely through.

In the light of the evidence offered against Qian and his collaborators, the true talent of this Chinese artist remains in the shadow. It’s a pity he never turned to original painting, which could have made him a respectable career.

It remains for the damaged to have faith in the US justice system, and for the rest of the bystanders to hope this kind of criminal behavior will come to some kind of just closure.

**********************

A good question. Are paintings by Pollock, Malevich and Rothko that easy to fake?

by Natalya Azarenko

arthive.com

October 29, 2019

Paintings of the 20th century are truly a great temptation for fraudsters specializing in fake art. The canvases, frames and paints of the period are easier to find than those of the paintings by old masters. It is often technically easier to copy directly the image itself — due to the features of avant-garde styles. The question is, rather, if it is possible to sell the fake subsequently at the price of the original.

Cover illustration: Kazimir Severinovich Malevich. Composition, 1932

Good chance comes at once

Regarding the Russian avant-garde, this branch of painting has a rather deplorable status in the art market. On the one hand, the high demand for Soviet modernists among the Western public led to the fact that they began to be faked on an industrial scale. And due to the fact that no one carefully monitored provenance, that is, the direct history of the canvases moving from one hand to another, during the times of the USSR (due to the specifics of the then art market, or rather, its legal absence, it was impossible), the authentication is problematic. After all, it is impeccable provenance that traditionally plays a decisive role in the attribution of paintings in the West.

Since it wasn’t customary to officially record transactions for the sale of works of art in all of the USSR, in order to restore the history of a picture, one does not have to study archives, but contact relatives who could confirm or deny its authorship. However, even in such cases, it is difficult to accurately determine the authenticity of the work.

Composition. Nikolai Suetin. 1920-th , 65×48 cm

The architect Nina Suetina, the daughter of Nikolai Suetin, one of Malevich's colleagues in Suprematist experiments, recalled how she once had failed to establish the truth: "Now they sometimes come and bring me works: ‘Sign that this is Suetin.' They tell me absolutely ridiculous stories of these works, there are a lot of fakes. In America, they showed me one work with a signature; I looked at it — it seemed to be the authentic Suetin, and I signed the authentication, and then it turned out that it was a fake, so now I’m more careful."

Very often all that experts have in store to authenticate artworks is a flair of style. Having worked with the pieces by a particular artist for a long time (compiling catalogues or writing monographs), experts begin to see distinctive features that help to notice fakes: they understand whether the well-known to him/her artist could paint in such a manner or not.

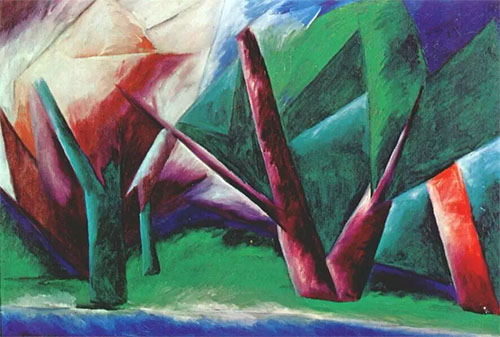

Aristarkh Vasilyevich Lentulov. Portrait of Artist's Wife and Daughter, 1915

Ivan Vasilievich Kliun. Self-Portrait with Saw, 1914

It comes to funny things. So, in 2014, Italy hosted the exhibition "Russian Avant-Garde: from Cubo-Futurism to Suprematism", where, according to the organizers, the works by Malevich, Goncharova, Lentulov and Kliun from private collections, many of which have never been exhibited before, were presented. Russian experts, such as art critic Andrey Sarabyanov, one of the authors of the Encyclopedia of Russian Avant-Garde, and Tatyana Goryacheva from the Tretyakov Gallery questioned the authenticity of the paintings at the exhibition. And although the curators claimed that it was confirmed by the laboratories of the Polytechnic Institute of Milan, they delicately glossed over the origin of certain works.

Aristarkh Lentulov. Woman with Harmonica, 1913

Forest. Red-green. Natalia Goncharova. 1914

Natalia Goncharova is especially liked by forgers. In 2011, a catalogue raisonné of the Russian artist was published in France; according to Andrey Sarabyanov, more than 400 paintings claim the title of fakes. Whatever it be, there are so many fake works of Russian avant-garde that serious auction houses only accept paintings by Russian modernists if there is a strong provenance that leaves no doubt about their authenticity.

Cats. Natalia Goncharova. 1913, 85.1×85.7 cm

One Chagall, two Chagalls

Fraudsters don’t usually risk making copies of famous paintings, the location of which is well known — for sure, no one will take a direct offer to buy, say, the original "Black Square" for serious. But some run the risk of duplicating less known works, hoping that they would never hit the market from a private collection, and the copy would not be exposed.

That’s what Ely Sakhai, a US dealer, did. He made copies of the paintings he acquired and sold them to Japanese collectors, attaching a real certificate of authenticity to them. He hoped that the fakes would settle in the Far East and would never intersect with the original. So he bought the The Purple Tablecloth by Marc Chagall for 312 thousand dollars, sold its copy to a Japanese collector for more than half a million, and then got rid of the original by selling it several years later for 626 thousand dollars.

The businessman got burned with Gauguin. In 2000, Christie’s and Sotheby’s suddenly put up two same pictures of the Frenchman at the auction. One of them, the fake, was exhibited for sale by the Japanese client of Sakhai, and the second one, the original, was put up by Sakhai himself. So he came to the attention of the FBI with all the ensuing consequences: he returned 11 paintings to his fraud victims, paid 12.5 million dollars and spent several years in prison.

Made by Chinese

One of the most grandiose scams in the art world turned out to be lucky from 1994 to 2009 for the former art dealer Glafira Rosales. She managed to sell fake paintings by Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko and other artists through the infamous Knoedler Gallery. When the truth surfaced, it led to the closure of the gallery and the arrest of the go-getter lady. However, by that time, she sold 31 works worth more than $ 80 million.

The real author of the works was the Chinese Pei-Shen Qian, who lived in New York. He copied the originals so skilfully that his paintings were borrowed for exhibitions by curators from the National Gallery of Art and the Guggenheim Museum. In their defence, we can only note that the Knoedler gallery at that time had a one and a half centuries history and an impeccable reputation, which contributed the possibility of such frauds.

Detail of the picture, which was said to be Jackson Pollock’s. Source: apnews.com

Auction houses Christie’s and Sotheby’s, who refused to accept Pollock’s work in 2011, that had been acquired by a London collector Pierre Lagrange from the Knoedler gallery for $ 17 million, exposed the fake. The results of the examination showed that the pigments used in the painting did not exist at the time of Pollock. Pei-Shen Qian managed to escape to his home in China, but Glafira Rosales faced the trial.

There is another extravagant way to determine the authenticity of Pollock’s paintings or other pictures that have the properties of fractal painting. According to the research of the American scientist Richard Taylor, such a parameter as the coefficient of fractal dimension of a pattern can help to identify a fake with an accuracy of more than 90 percent.

The producers of fake masterpieces sometimes turn out to be so talented that their paintings occupy places in special exhibition halls intended for the best fakes, and individual museums are engaged in their collecting.

One of the works by Pei-Shen Qian, performed "à la Rothko", was honoured to open the exhibition "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum (Delaware, USA). Thus, for some artists, the path to their 15 minutes of fame goes through deception.

Photo of the Pei-Shen Qian painting in the manner of Mark Rothko: winterthur.org

*************************

Knoedler case forger protests innocence in interview

by phaidon.com

July 21, 2014

A fake Jackson Pollock, painted by Pei-Shen Qian

Pei-Shen Qian tells ABC’s Nightline he was surprised anyone fell for his abstract expressionist forgeries

If you painted a canvas with dripped paint, signed it 'Jackson Pollok' rather than Pollock and received a few thousand dollars in return, are you guilty of forgery? The FBI certainly believe so, and charged septuagenarian Chinese-born artist Pei-Shen Qian with a number of offences relating to the abstract expressionist canvases Qian created, some of which were sold via the Knoedler gallery in New York.

Qian moved back to China just before the FBI’s charges were brought last April, and is unlikely to return to the US to face justice. However, he has just given this interview to ABC’s Nightline, wherein he protests his innocence.

The channel’s investigative team, headed by reporter Brian Ross, tracked the artist down to a suburb outside Shanghai, where Qian now lives. “My intent was not for paintings to be sold as the real thing,” he claims. “They were just copies to be put up in your home if you liked them.”

Pei-Shen Qian speaking to ABC's Nightline

Moreover, the painter thinks the sums he was paid – about $6000 per canvas - indicate that he was never part of a larger conspiracy to sell the works as genuine works, often for many millions of dollars. “Look at my bank account,” he says. “ I’m still a poor artist.”

Qian also tells the reporters that he was shocked that his versions of Pollock, Rothko and others ever fooled anyone. “These copies were supposed to mimic them on a very basic level,” he claims. “I was very surprised people mixed them up.”

The footage, shot in what looks like a modest Chinese apartment, doesn’t portray Qian as a masterful art criminal, but rather a minor player in a larger scandal, designed to pass off 60 or so works as paintings by 20th century artists including Robert Motherwell and Willem de Kooning.

One of Pei-Shen Qian's original works, Shanghai Landscape no. 4 (2000)

Qian was part of Shanghai’s avant-garde art scene in the 1970s before relocating to New York in an attempt to make it within the gallery system. Though he's returned to China, he continues to paint; however, Nightline notes, the artist no longer adds anyone else’s name to his canvases.

***

Accused Master Art Forger Tracked Down in Shanghai: U.S. says artist created fake Rothkos and Pollocks that fooled art experts.

by Megan Chuchmach and Brian Ross

ABC News

July 15, 2014, 7:28 AM

In his first television interview, the elderly artist whose look-alike paintings in the styles of Abstract Expressionists including Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock fooled experts and sent shock waves through the art world claims he was ”shocked” to learn that his works were sold as newly discovered masterpieces to wealthy collectors for tens of millions of dollars.

“When I made these paintings, I had no idea they would represent them as the real thing to sell,” said Pei Shen Qian in an interview to be broadcast Tuesday on “World News With Diane Sawyer” and “Nightline” as part of an ABC News investigation of the fake art industry and the Long Island fraud ring that flooded the market with over $80 million in forged work.

Now under federal indictment in New York on charges of fraud, Qian has moved from his studio in the New York borough of Queens to a small apartment on the outskirts of Shanghai where ABC News found him.

“My intent wasn’t for my fake paintings to be sold as the real thing,” Qian said. “They were just copies to put up in your home if you like it.”

But according to the federal grand jury indictment, Qian created some 63 look-alike versions of the abstract work of Rothko and Pollock and others and lied to FBI agents about his role in the fraud.

Authorities said this is work, purportedly by Mark Rothko, is actually a fake, used in an art fraud ring.

Obtained by ABC News

The indictment charges that Qian claimed he was unfamiliar with the names of certain artists “whose names Qian had repeatedly and fraudulently signed on paintings Qian created.”

Federal authorities say Qian was recruited to create the paintings by a Long Island, New York couple who began the fraud scheme in the early 1990s. U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara, of the Southern District of New York, called the defendants “modern masters of forgery and deceit” and said they “tricked victims into paying more than $33 million for worthless paintings, which they fabricated in the names of world-famous artists.”

One of those charged, Glafira Rosales, pleaded guilty to fraud, tax and money laundering charges last year and is reported to be cooperating with authorities in the ongoing investigation.

Her boyfriend and alleged partner, Jose Carlos Bergantinos Diaz, was arrested in Spain earlier this year on federal charges and the U.S. has asked for his extradition.

Authorities say Diaz discovered Qian’s talent as he painted on a Manhattan street corner in the early 1990s and began commissioning his works.

But Qian remains beyond the reach of American law because the U.S. has no extradition treaty with China.

When ABC News found him in Shanghai late last year, prior to the federal indictment, he said he was paid much less than the Long Island art dealers who hired him. They made millions off the paintings by telling galleries they represented a mystery man who had inherited a treasure trove of masterpieces and wished to remain anonymous. The indictment says Qian was often paid between $5,000 to $8,000 for a look-alike work.

“If you look at my bank account, you’ll see there is no income,” Qian said.

Painting a work in the style of a particular artist and signing a signature is not in itself a crime, however passing it off as an authentic work is illegal.

Qian says he no longer creates look-alike works and spends his time in a small, one bedroom apartment surrounded by hundreds of paintings signed in his own name. He was a well-known artist in China years before the Long Island ring was revealed, with frequent exhibitions and even a hardcover book published devoted to his life and work. Now, that work continues.

“Painting. Painting. Painting,” Qian said of how he spends his days. “Everything is done for painting.”