by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/25/23

-- Da Asia De Diogo De Couto. Dos Feitos, Que Os Portuguezes Fizeram Na Conquista, E Descubrimento Das Terras, E Mares Do Oriente. Decada Quinta. Parte Primeira. Anno 1779. Of Asia. Of the feats that the Portuguese did in the conquest and discovery of the lands and seas of the East. Fifth Decade. Part One. Year 1779. By Diogo De Couto.

https://archive.org/stream/daasiadediog ... t_djvu.txt

The First European Account of the Vedas

It was only toward the end of the sixteenth century that the Vedas are first mentioned, by Agostinho de Azevedo, an Augustinian. Azevedo’s biography has been reconstructed by Georg Schurhammer, who thinks it possible he first went to India as a soldier before joining the Augustinian order in Goa in the 1570s. Azevedo was sent back to Portugal to ordain and train, returning to India in 1586. From 1589 to 1600 he was in Hormuz, from where he returned overland to Portugal, where he completed a Relação do Estado da Índia.16 Azevedo’s report provides an overview of Portuguese settlements in Asia from the Arabian Gulf to the spice islands, devoting particular attention to Hormuz and Ceylon. It is notable that in his accounts of both, Azevedo draws on local textual sources. For Hormuz, he claims that he read these sources himself, but for Ceylon he relied on an interpreter’s simultaneous translation of Sinhalese chronicles recited for him when he met Sinhalese princes in Goa around 1587. There is a similar emphasis on textual sources in his section on India, entitled “Of the opinions, rites, and ceremonies of all the gentiles of India between the river Indus and the Ganges and that which is contained in their original scriptures which their learned men teach in their schools.” The Brahmins, the “masters of their religion,” teach a unified doctrine of God, creation, and the corruption of creatures. They have, writes Azevedo,many books in their Latin, which they call Geredão [Grantha] which contain everything they are to believe, and all the ceremonies they are to perform. These books are divided into bodies, limbs, and joints, whose origins are some [books] which they call Veados, which are divided into four parts, and these further into fifty-two parts in the following manner: six are called Xastra, which are the bodies; eighteen are called Purana, which are the limbs; twenty-eight called Agamon which are the joints.

Azevedo’s brief account of the content of the four “origins” makes clear that he had no real access to the Vedas themselves. When he comes to elaborate on the content of the fourfold Veda, he in fact names a series of other texts—all in Tamil. The first part of the Vedas, he writes, deals with the first causeaccording to the books which they have called Tirumantiram and Tiruvācakam, which are summas of their theology which they read in the schools. They say that this first cause is God, and that he is a pure spirit, incorporeal, infinite, full of all power and knowledge and truth, and present everywhere, which they call Carvēsparaṉ [Xarves Zibarum] which means the creator of all.21

For the second part of the Vedas, “dealing with the regents who have dominion over all things,” Azevedo again cites a Tamil text: “They say that this supreme [being] which they call God has infinite names, given in a particular book called Tivākaram.”22 His account of the third part of the Vedas, on moral doctrine, singles out the author of Tirukkuṟaḷ as the great teacher of moral precepts. Like many later missionary authors, Azevedo suggests Tiruvaḷḷuvar had derived these from St Thomas. Finally, Azevedo refers to a further book, Cātikaḷ Tōṭṭam, on castes. This text is difficult to identify, but its southern provenance is confirmed by the names of the four primary castes: kings, brahmins, chettis, and vellalas.

Despite his claim, then, that the Vedas are the original scriptures that prescribe what the gentiles of India are to believe and what rites they are to perform, Azevedo’s actual sources are all much later Tamil sources: Tirumantiram, Tiruvācakam, Tivākaram, Tirukkuṟaḷ, and the text on caste. This combination—identification of the Vedas as the oldest authoritative sources, together with a reliance on quite different texts for the actual details of the religious practices of those who so acknowledged the Vedas—would be repeated in the works of many of those who wrote from India. But the identification of the Vedas as the oldest and most authoritative works meant that it was only the Vedas that gained widespread recognition in Europe as the sacred texts of the Indians.

Azevedo In Other Authors

Although Azevedo’s work was not published until the twentieth century, it had an extraordinary impact on European understanding of the Vedas in the seventeenth century. Diogo do Couto, who had met Azevedo in Goa, used Azevedo’s work in his continuation of João de Barros’s chronicle of the Portuguese Asian empire, the Décadas da Ásia (see n. 16 above). The third and fourth chapters of the sixth book of Couto’s fifth decade, published at Lisbon in 1612, are taken almost verbatim from Azevedo. Couto’s work, in turn, was used by João de Lucena in his life of Xavier. The Dutch chaplain, Abraham Rogerius, followed one or the other of these works very closely in the account of the Vedas in his De Open-Deure tot het Verborgen Heydendom (1651), adding only the names of the Vedas, which he is the first to report in print in Europe. Through his primary informant, a Tamil Brahmin named Padmanābha, Rogerius was even able to give a paraphrase of part of a Sanskrit text (the Nītiand Vairāgya-śatakas of Bhartṛhari), although he again relies on other sources including some in Tamil. While Rogerius emphasizes that the Brahmins “must submit themselves to the Veda, and cannot contradict it in the least or object when a text from it is cited,” he adds that there are often strong disputes over the sense of the text: “one interprets a word thus, the other so,” so that to resolve such disputes reference is made to the “śāstra, which betokens so much as an explanation or exposition.” This was perhaps suggested to him to explain why texts other than the Vedas were those to which he was referred, despite the Veda’s acknowledged ultimate authority. Burnell suggests that, rather than the Vedas, Rogerius’s work in fact reflects the Tamil Vaiṣṇava canonical collection, the Nālāyira Tiviyappirapantam. Rogerius’s work gives a great deal of detailed information on brahminical Hinduism, but it was his repetition of Azevedo’s summary content of the Vedas that was most important for their reputation in Europe.

Rogerius’s work was quickly translated into German (1663) and French (1670), plagiarized in Dutch by Philip Baldaeus (1672) and Olfert Dapper (1672), and extracted in English and French in the works of John Ogilby (1673) and of Jean-Frédéric Bernard and Bernard Picart (1723, 1731). Each of these included Azevedo’s summary of the Vedas, and in this way it was very widely disseminated in Europe. Even late in the eighteenth century, Azevedo’s account of the Vedas was repeated almost verbatim in the work of the Italian Capuchin, Marco della Tomba. Although Couto, who repeats almost the whole of Azevedo’s account, retained all the references to Tamil texts, none of these subsequent works (with the partial exception of Lucena, who retains only the reference to Tiruvaḷḷuvar) mention any of the Tamil sources, despite Azevedo’s claim that these are the “summas of their theology.” In this way the idea was firmly established in Europe that it was the Vedas, above all and almost to the exclusion of other texts, that were the sacred books of India.

___________

16. Georg Schurhammer, Francis Xavier: His Life, His Times, vol. 2: India 1541–1545 (Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, 1980), 614–16. Two versions of Azevedo’s “Estado da Índia e aonde tem o seu principio,” from manuscripts in the British Library and the Bibliotheca Nacional de Madrid, are printed in António da Silva Rego and Luıś de Albuquerque, eds., Documentação ultramarina portuguesa (Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos, 1960–63), I: 197–263 and II: 40–147. I cite from the first version, except where noted. Schurhammer (Xavier, 2: 616–20) notes that there are close parallels in three sections of these texts with parts of the fifth of Diogo do Couto’s Décadas da Asiá. In the case of the first two—which relate to the history of Hormuz (210–12) and of Ceylon (235– 54)—Azevedo mentions that Couto had asked him to provide information (205, 235). Couto, who elsewhere does mention his sources, nowhere acknowledges Azevedo. There are also close parallels in the section on Indian religion in Azevedo and Couto and also with that which appears in João de Lucena in his life of Xavier. Lucena’s work was published in 1600, Schurhammer dates the final version of Azevedo’s text to 1603 (Xavier, 2: 616), and Couto’s work did not appear until 1612. Nevertheless it appears that Lucena used the manuscript of Couto’s fifth decade, a version of which was sent to Lisbon as early as 1597 (Marcus de Jong, ed., Década quinta da “Asia”: Texte inédit, publ. d’après un manuscrit de la Bibliothèque de l’Univ. de Leyde [Coimbra: Biblioteca da Universidade, 1937], 47). In a letter sent from Goa in November 1603, Couto complained bitterly about Lucena’s use of information which he claimed to have acquired at great effort and expense from the schools of the Brahmins in the kingdom of Vijayanagara (Schurhammer, Xavier, 2: 620). Despite Couto’s claim here that “in all my Decades I have given to each his due,” it seems likely that he had again used without acknowledgment material provided to him by Azevedo. The account of Indian religion was likely prepared by Azevedo during his second period in India between 1586 and 1589, and later incorporated into his Relação do Estado da Índia, completed in Lisbon by 1603....

21. The names of the texts in Rego’s transcription are “Ferum Mandramole e Trivaxigao” (Azevedo, “Estado da Índia,” 251) or “Tonem, Mandramolé e Trivaxigao” (Silva Rego, Documentação ultramarina portuguesa, II: 134). In the 1612 editio princeps of Couto these appear as “Terúm, Mandramole, Etrivaxigão.” From Couto’s work, Willem Caland was confident in identifying the latter as Tiruvācakam, less so the first as Tirumantiram (De ontdekkingsgeschiedenis van den Veda [Amsterdam: Johannes Müller, 1918], 273). Although neither Tirumantiram nor Tiruvācakam uses carvēsparaṉ, or the more common carvēccuraṉ (Sanskrit, sarveśvara), to refer to God, there can be no doubt that Tiruvācakam is meant here, and good reason to think that Tirumantiram could also have been intended.

22. Azevedo, “Estado da Índia,” 255. In both Rego’s transcriptions, and Couto, the title of the work is given as Tivarum. Although Caland (Veda, 318) suggests Tēvāram, Azevedo’s description of the content leaves little doubt that it is rather Tivākaram, an important early Tamil lexicon that begins with a list of the divine names, which is meant....

135. Caland concluded his 1918 essay by noting the limits of most Brahmins’ knowledge of the Vedas, adding that while it was not that there were no Brahmins who could have given Europeans a better and fuller account of the Vedas “do Couto, Rogerius and all the others knocked on the wrong door” (Veda, 303). Ludo Rocher expressed similar “reservations concerning the weight that has been given to the secrecy argument” (“Orality and Textuality in the Indian Context,” Sino-Platonic Papers, 49 [1994]: 5). Rocher was “convinced that there was, far more often, a second reason why Westerners were denied a knowledge of the Vedas; their Indian contacts, who were supposed to provide them with information on the Vedas, did not possess it themselves, and, therefore, were unable to communicate it” (“Max Müller and the Veda,” in Mélanges d’islamologie: Volume dédié à la mémoire de Armand Abel par ses collègues, ses élèves et ses amis, ed. Armand Abel and Pierre Salmon, vol. 2 [Leiden: Brill, 1974], 223).

-- The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

The text which has served for the following translation comprises the Suktas of the Rig-Veda and the commentary of Sayana Acharya, printed, by Dr. Muller, from a collation of manuscripts, of which he has given an account in his Introduction.

Sayana Acharya was the brother of Madhava Acharya, the prime minister of Vira Bukka Raya, Raja of Vijayanagara in the fourteenth century, a munificent patron of Hindu literature. Both the brothers are celebrated as scholars; and many important works are attributed to them, — not only scholia on the Sanhitas and Brahmanas of the Vedas, but original works on grammar and law; the fact, no doubt, being, that they availed themselves of those means which their situation and influence secured them, and employed the most learned Brahmans they could attract to Vijayanagara upon the works which bear their name, and to which they, also, contributed their own labour and learning. Their works were, therefore, compiled under peculiar advantages, and are deservedly held in the highest estimation.

-- RigVeda Sanhita. A Collection of Ancient Hindu Hymns, Constituting the First Ashtaka, or Book of the Rig-Veda: The Oldest Authority for the Religious and Social Institutions of the Hindus. Translated from the Original Sanskrita by H.H. Wilson

With regard to the twelve MSS. of the Commentary to the first Ashtaka of the Riv-veda, I have only succeeded in reducing them to three independent classes. It is not very likely that MSS. should still be found in India contemporaneous with Sayana, though, if we could trust native authorities, copies of Sayana's works have been buried in the ground near Vidyanagara [Vijayanagara]. Excluding these MSS. the existence of which is extremely problematical, I am convinced that there are no Mss. at present which have any claim to be considered as exhibiting the Commentary exactly such as it came from the hands of Sayana....

It would have been equally wrong, however, to consider Sayana's commentary as an infallible authority with regard to the interpretation of the Veda. Sayana gives the traditional, but not the original, sense of the Vaidik hymns. These hymns -- originally popular songs, short prayers and thanksgivings, sometimes true, genuine, and even sublime, but frequently childish, vulgar, and obscure -- were invested by the Brahmans with the character of an inspired revelation, and made the basis of a complete system of dogmatic theology. If therefore we wish to know how the Brahmans, from the time of the composition of the first Brahmana to the present day, understood and interpreted the hymns of their ancient Rishis, we ought to translate them in strict accordance with Sayana's gloss. This is the object which Professor Wilson has always kept in view in his translation of the Veda; and for the history of religion, which in India, as elsewhere, represents the gradual corruption of simple truth into hierarchical dogmatism and philosophical hallucination, his work will always remain the most trustworthy guide. Nor could it be said, that the tradition of the Brahmans, which Sayana embodied in his work, after the lapse of at least three thousand years, had changed the character of the whole of the Rig-veda. By far the greater part of these hymns is so simple and straightforward, that there can be no doubt that their original meaning was exactly the same as their traditional interpretation. But no religion, no poetry, no law, no language, can resist the wear and tear of thirty centuries; and in the Veda, as in other works, handed down to us from a very remote antiquity, the sharp edges of primitive thought, the delicate features of a young language, the fresh hue of unconscious poetry, have been washed away by the successive waves of what we call tradition, whether we look upon it as a principle of growth or decay. To restore the primitive outlines of the Vaidik period of thought will be a work of great difficulty....

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

The princely and truly patriotic liberality of His Highness the Maharajah of Vijayanagara has enabled me to take up once more in the evening of my life that work which has occupied me during my youth and during my advancing years....

I received a letter from His Highness the Maharajah of Vijayanagara, offering to defray the whole expense of a new edition, if I were still willing to undertake the labour of revising the text.

-- Rig-Veda-Sanhita: The Sacred Hymns of the Brahmans, Together with the Commentary of Sayanacharya, edited by Dr. Max Muller

Already in Ricci's and de Nobili's time, around the beginning of the seventeenth century, the claim surfaced that the Vedas of India were the repository of ancient Indian monotheism. Of course, the approach of Nobili and his successors in the Jesuit Madurai mission was anchored in the idea that India had once been a land reigned by pure monotheism; but the locus classicus for the monotheism of the Vedas is the description in Diogo do Couto's Decada Quinta da Asia of 1612 (124Vff.). Schurhammer (1977:614-18) has shown that Couto plagiarized the report by the Augustinian missionary Agostinho de Azevedo, but it was through Couto that this view of the Vedas as a monotheistic scripture, hidden by the Brahmans from the people to whom they preached polytheism, became popular. Since Couto's description was a central source for Holwell, I will discuss it in more detail in Chapters 5 and 6; here its summary by Philip Baldaeus will suffice:The first of these Books treated of God and of the Origin and Beginning of the Universe. The second, of those who have the Government and Management thereof. The third, of Morality and true Virtue. The fourth of the Ceremonials in their Temples, and Sacrifices. These four Books of the Vedam are by them call' d Roggo Vedam, Jadura Vedam, Sama Vedam, and Tarawana Vedam; and by the Malabars Icca, Icciyxa, Saman, and Adaravan. The loss of this first Part is highly lamented by the Brahmans. (Baldaeus 1703:891)

Though various descriptions based on Azevedo and Giacomo Fenicio made the rounds, no European had yet managed to get access to more than fragments of these prized Vedas....

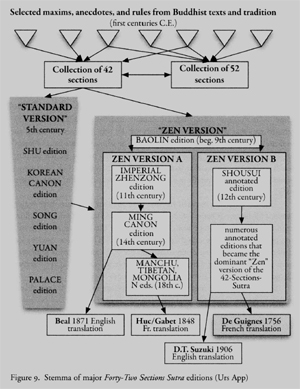

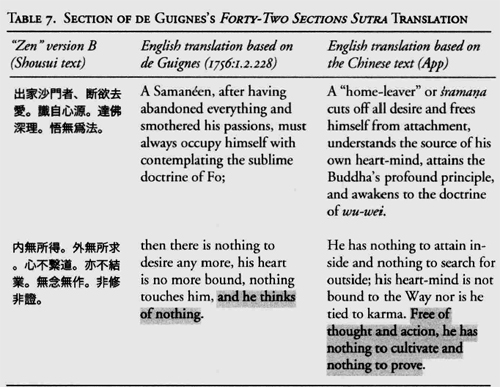

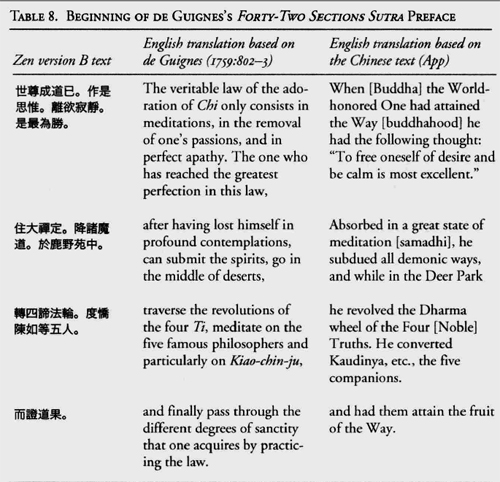

De Guignes's "Indian Religion"

....

De Guignes from the outset based his view on two specific texts. He devoted the entire second part of his 1753 paper to their analysis and included partial translations from the Arabic and Chinese (de Guignes 1759:791-804). The first of these texts, the so-called Anbertkend (sometimes also spelled Ambertkend), is today known as the Amrtakunda (Pool of Nectar), a Hatha Yoga text of Indian origin that has nothing to do with Buddhism.... For him the Anbertkend was an important text of the so-called "Indian religion" that "contains the principles admitted by the Yogis, particularly those related to magic" (p. 791)." The second text discussed by de Guignes is presented as "the work of Fo himself that includes all the moral teachings he bequeathed to his disciples" (p. 791). While this second text is well known under the title Forty-Two Sections Sutra and is extant in Chinese, the Anbertkend or Amrtakunda is not exactly a household word. De Guignes described it as an Indian book that was "translated into the Persian language by the Imam Rokneddin Mohammed of Samarkand who had received it from a Brahmin called Behergit of the sect of the Yogis" and was subsequently translated into Arabic by Mohieddin-ben-al-arabi. D'Herbelot's Bibliotheque Orientale features the following information under the heading "Anbertkend" (1697:114):Book of the Brachmans or Bramens which contains the religion and philosophy of the Indians; this word signifies the cistern where one draws the water of life. It is divided into fifty Beths or Treatises of which each has ten chapters. A Yogi or Indian dervish called Anbahoumatah, who converted to Islam, translated it from the Indian into Arabic under the title Merat al maani, The Mirror of Intelligence; but though it was translated, this book cannot be understood without the help of a Bramen or Indian Doctor.

Four decades after d'Herbelot, Abbe Antoine BANIER (1673-1741) widely disseminated the idea that the four Vedas contain "all the sciences and all religious ceremonies" whereas the Anbertkend "contains the doctrines of the Indians" (Banier 1738:1.128-29). De Guignes also thought that "this book is not at all the Vedam of the Indians" but regarded it as "a work of the contemplative philosophers who, far from accepting the Vedam, reject it as useless based on the great perfection they believe to have attained" (de Guignes 1759:791-92). This description very much resembles the one given by Bartholomaus Ziegenbalg and La Croze of the Gnanigol [Ganiguels] and their (Tamil Siddha) literature including the Civaviikkiyam. According to de Guignes, the Anbertkend is a "summary of the contemplatives of India" (p. 796) that advocates that "to become happy one must annihilate all one's passions, not let oneself be seduced by the senses, and be in the kind of universal apathy that is so much recommended in the book of Fo" (p. 793). Apart from this, the only apparent connection to Fo or Buddha is a mantra connected with the contemplation of the planet "Boudah or Mercury" (p. 800)....

Relying on several authors of European antiquity whose view of Indian religions La Croze had popularized, de Guignes accepted that in ancient India there were two main factions: the "ancient Brakhmanes," and the "Germanes, Sarmanes, or Samaneens" (p. 770). Supplementing the sparse information from Greek and Roman authors, de Guignes proposed to "make use of clarifications from Chinese and Arab authors in order to provide a more exact idea about the sect of the Samaneens by examining who their founder is, in which country it originated, and what doctrine he left to his disciples at his death" (p. 770)....What I have reported based on the Greek and Latin writers compels me to believe that there is little difference between the Samaneens and the Brachmanes, or rather, that they are two sects of the same religion. In effect, one still finds in the Indies a crowd of Brachmanes who appear to have the same doctrine and live in the same manner [as the Samaneens described by Greek and Latin writers]; but those who resemble the ancient Samaneens most perfectly are the Talapoins of Siam: like them, they live retired in rich cloisters, have no personal possessions, and enjoy great reputation at court; but more austere ones exclusively live in woods and forests, and there are also women under the direction of these Talapoins. (p. 773)...

But what is this religion of which the Brachmanes and the Samaneens supposedly constitute two separate sects? De Guignes simply calls it "the Indian religion" (la religion Indienne; p. 779). It is likely that de Guignes was also inspired by Johann Jacob Brucker's treatise on Asian philosophy (Brucker 1744:4B.804-26) and by Nicolas FRERET (1688-1749), who had studied Chinese even before Fourmont and had read a paper in 1744 that advanced exactly this opinion (see the beginning of Chapter 7). Freret asserted that "La religion indienne" is extremely widespread in Asia; reigning in India as "la religion des Brahmes," "Indian religion" has also conquered Tibet, Bhutan, China since the year 64 C.E., Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Siam, Burma, and so on (Freret 1753:36). But while Freret sought the doctrine of this religion in Diogo do Couto's description of the Vedas and combined it with some Buddhist elements, de Guignes decided to take the Buddhist track and identified the founder of his "religion Indienne" as Buddha who is venerated under various names in different countries of Asia....

The Shastah and the Vedas

...

[H]ere we will concentrate on Couto whose report about sacred Indian literature, unlike Azevedo's, was used by Holwell who could handle Portuguese. Couto's report of 1612 describes Indian sacred literature as follows:They possess many books in their Latin, which they call Geredaom, and which contain everything they have to believe and all ceremonies they have to perform. These books are divided in bodies, members, and articulations. The fundamental texts are those they call Vedas which form four parts, and these again form fifty-two in the following manner: Six that they call Xastra which are the bodies; eighteen they call Purana which are the members; and twenty-eight called Agamon which are the articulations. (Couto 1612:125r)

TABLE 11. Do COUTO'S VEDAS AND HOLWELL'S SACRED SCRIPTURES OF INDIA

Couto / Holwell (1767)

4 Vedas / I / 4 scriptures of divine words of the mighty spirit (Chartah Bhade Shastah of Bramah)

6 Xastras / II / 6 scriptures of the mighty spirit (Chatah Bhade of Bramah)

18 Puranas / III / 18 books of divine words (Aughtorrah Bhade Shastah)

28 Agamon / IV / Divine words of the mighty spirit (Viedam of Brummah)

The numbers four, six, and eighteen first made me think that Holwell's weird history of Indian sacred literature might be modeled on Couto's report. As we have seen, Holwell also mentioned four textual bodies. The number of scriptures of the first three bodies thus correspond exactly to Couto's, as shown in Table II....

[Holwell] must have preferred Couto's description of the Veda's content:To better understand these [Vedaos] we will briefly distinguish all of them. The first part of the four fundamental texts treats of the first cause, the first matter [materia prima], the angels, the souls, the recompense of good, the punishment of evil, the generation of creatures, their corruption, what sin is, how one can attain remission and be absolved, and why. The second part treats of the regents and how they exert dominion over all things. The third part is all about moral doctrine, advice exhorting to virtue and obliging to avoid vice, and also for monastic and political life, i.e., active and contemplative life. The fourth part treats of temple ceremonies, offerings, and their festivals; and also about enchantment, witchcraft, divination, and the art of magic since they are much taken by this kind of thing. (Couto 1612:125r)

TABLE 12. CONTENTS OF Do COUTO'S FIRST VEDA AND THE FIRST BOOK OF HOLWELL'S SHASTAH

Couto's first Veda in Decada Quinta (1612:125r) / First book of Holwell's Shastah (1767:30)

first cause, materia prima / God and his attributes

angels / creation of angelic beings

souls (of angels in human bodies) / lapse of angelic beings

punishment, recompense / punishment, mitigation

remission, absolution / final sentence leading to remission

The comparison of this description with Holwell's summary (1767=30) of the contents of his Shastah (see Table 12) shows that they are also quite a good match. This common inspiration may explain another contradiction in Holwell's portrayal of Indian sacred literature, namely, why -- in spite of his rantings against the Veda as a late and degenerate text -- Holwell claimed that both his Shastah (Text I) and the Viedam (Text IV) were "originally one":Both these books [the Viedam and Shastah] contain the institutes of their respective religions and worships, often couched under allegory and fable; as well as the history of their ancient Rajahs and Princes -- their antiquity is contended for by the partisans of each -- but the similitude of their names, idols, and a great part of their worship, leaves little room to doubt, nay plainly evinces, that both these scriptures were originally one. (Holwell 1765:1.12)

If Couto's summary of Veda content does not seem overly concerned with angels, the more detailed explanations (Couto 1612:125v) provide details that were certainly of great interest to a man so thoroughly converted to Jacob Ilive's system as Holwell. Couto wrote that Indian manuals of theology portray God as first cause and as "a pure, incorporal, infinite spirit, endowed with all might, all knowledge, and all truth" who "is everywhere, which is why they call him Xarues Zibaru which signifies creator of all" (p. 125v). According to Couto, the first Veda then describes three kinds of angels: the good angels that remain in heaven with God; the delinquent angels who must go through rehabilitation imprisoned in human bodies on earth; and the angels shut in hell. It furthermore treats of the immortality of souls and their transmigration during the rehabilitation process on earth: "They believe that the souls are immortal; but they think that a sinner's soul at death passes into the body of some living being where it continues purification until it merits rising to heaven" (p. 125v). Couto goes into considerable detail about the meaning of transmigration and its deep connection with the punishment of evil and recompense of good: the souls of the worst sinners transmigrate after death into the most terrible animals, and those of the good into an ever better body. In this way they can purify themselves and atone until they become ready to regain their original state before the fall (pp. 125v-126r)....

If Holwell was trying to find the Vedas, he was not alone; but Couto's description of the first Veda, which seemed so similar to Ilive's ideas, certainly brought more motivation and focus to his search. He knew that he was looking for an extremely ancient scripture treating of God, the creation Story, angels and their fall, the immortality of souls, the purification of delinquent angels in human bodies, transmigration, the punishment of evil and reward of good, and remission and salvation.

-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

Diogo do Couto

Born c. 1542

Lisbon, Kingdom of Portugal

Died 1616

Goa, Portuguese India

Nationality Portuguese

Occupation Historian

Diogo do Couto (Lisbon, c. 1542 – Goa, 10 December 1616) was a Portuguese historian.

Biography

He was born in Lisbon in 1542 to Gaspar do Couto and Isabel Serrão Calvos. He studied Latin and Rhetoric at the College of Saint Anthony the Great (Colégio de Santo Antão), an important Jesuit-run educational institution in Lisbon. He also studied philosophy at the Convent of Saint Dominic (Convento de São Domingos de Benfica) in Benfica.[1]

In March 1559 (Armada of Pêro Vaz de Sequeira) he traveled to Portuguese India. As a soldier he took part in the Surat campaign in March 1560, living in Bharuch in 1563.

He returned to Lisbon with D. António de Noronha in 1569.

He was a close friend of the poet Luís de Camões, and described him in Ilha de Moçambique in 1569, as indebted and unable to fund his return to Portugal. Couto and other friends took it upon themselves to help Camões, who was thus enabled to take his most significant work, the Lusiads, to the capital.

Couto arrived in Lisbon on board the Santa Clara in April 1570, only to discover that the port was closed due to plague. Upon receiving permission from the King of Portugal (who he met in Almeirim), the ship docked in Tejo.

Shortly after Couto returned to Goa in the Armada of D. António de Noronha, he married Luisa de Melo and worked in a supply warehouse.

In 1595, Couto was invited to organize the Goa archive (being appointed "Guarda-Mor do Tombo da India") and to continue writing the Décadas (a history of the Portuguese in India, Asia, and southeast Africa) of João de Barros.

The 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th Décadas were published during his lifetime. After Couto died, his other works were in the hands of his brother-in-law, the priest Deodato da Trindade.

Works

• Decada Quarta (Dos feitos que os portugueses fizeram na conquista e descobrimento das terras e mares do Oriente, em quanto governaram na India Lopo Vaz de Sampaio e parte de Nuno da Cunha), Lisboa 1602;

• Decada Quinta (Dos feitos...em quanto governaram na India Nuno da Cunha, Garcia de Noronha, Estevão da Gama e Martim Afonso de Sousa), Lisboa 1612

• Decada Sexta (Dos feitos...em quanto governaram na India João de Castro, Garcia de Sá, Jorge Cabral e Afonso de Noronha), Lisboa 1614

• Decada Setima (Dos feitos... em quanto governaram na India Pedro de Mascarenhas, Francisco Barreto, Constantino Conde de Redondo, Francisco Coutinho e João de Mendonça), Lisboa 1616;

• Decada Oitava (Dos feitos...em quanto governaram na India Antão de Noronha e Luis de Ataíde), Lisboa 1673 (edited by Joao da Costa e Diogo Soares);

• Decada Nona (written in 1614, and stolen, with the OITAVA);

• Decada Décima (Dos feitos...em quanto governaram na India Fernão Telles, Francisco de Mascarenhas e Duarte de Menezes), Lisboa 1778

• Decada Undecima (lost or stolen, during the lifetime of the author);

• Decada Duodecima ("Tratado os Cinco Livros da Década XII"), Paris 1645;

• "Fala que fez em nome da Câmara de Goa ... a André Furtado Mendonça, em dia do Espírito Santo de 1609" (Lisboa 1810);

• Vida de Paulo de Lima Ferreira, Capitão Mor das Armadas do Estado da India

• O Soldado Prático (the original was stolen, and the author re-made it in 1610, and sent it to Manuel Severim de Faria), Lisboa 1790 (2nd ed. 1954, 3rd ed. 1980);

• Tratado de todas as cousas socedidas ao valeroso Capitão Dom Vasco da Gama primeiro conde da Vidigueira: almirante do mar da India: no descobrimento,e conquista dos mares, e terras do Oriente: e de todas as vezes que ha India passou, e das cousas que socederão nella a todos seus filhos, Lisboa 1998.

References

1. Couto, Diogo do; Caminha, Antonio Lourenço (1808). Obras ineditas de Diogo do Couto [New works by Diogo do Couto] (in Portuguese). Imperial e Real.

Bibliography

Loureiro, Rui Manuel, A biblioteca de Diogo do Couto, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1998.

Diogo do Couto orador. Discursos oficiais proferidos na Câmara de Goa, edited by Maria Augusta Lima Cruz, Nuno Vila-Santa and Rui Manuel Loureiro, Portimão, Arandis/ISMAT, 2016.

Vila-Santa, Nuno, "O Primeiro Soldado Prático de Diogo do Couto e os seus contemporâneos" in Memórias 2017, Lisboa, Academia de Marinha, vol. XLVII, 2018, pp. 171–190. [1]

Vila-Santa, Nuno, "Diogo do Couto e Belchior Nunes Barreto: similitudes e diferenciações de dois interventores políticos contemporâneos" in Diogo do Couto. História e intervenção política de um escritor polémico, Edições Humus, Vila Nova de Famalicão, 2019, pp. 191–220. [2]

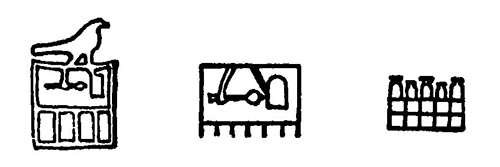

was mani or Mannus, the progenitor of humanity, which once more forms a special section in the

was mani or Mannus, the progenitor of humanity, which once more forms a special section in the  for Mannus or Mene, the spiritual Moon (Psychomena).

for Mannus or Mene, the spiritual Moon (Psychomena). is Tyr, Zio, also Zeizzo or Erich, the one-armed sword-god, the "generator." His hieroglyph also consists of the sign of Ur

is Tyr, Zio, also Zeizzo or Erich, the one-armed sword-god, the "generator." His hieroglyph also consists of the sign of Ur  and the Tyr-rune

and the Tyr-rune  , which symbolizes the solar ray, the solar arrow as impregnator (phallus). His sword, his one-arm, his phallus erectus, clearly designates him as the provider of increase, the multiplier or generator under whose guardianship marriages stood, but war as well, since war increased property through the taking of booty and drove out vermin. The fourth, Mercury

, which symbolizes the solar ray, the solar arrow as impregnator (phallus). His sword, his one-arm, his phallus erectus, clearly designates him as the provider of increase, the multiplier or generator under whose guardianship marriages stood, but war as well, since war increased property through the taking of booty and drove out vermin. The fourth, Mercury  , is Wuotan, whose rune (othil

, is Wuotan, whose rune (othil  ) is in this instance reversed

) is in this instance reversed  and connected to the sign of increase

and connected to the sign of increase  to form

to form  , indicating the increaser, bringer of luck, the wish-god.

, indicating the increaser, bringer of luck, the wish-god.  , and means primeval generation, or "the one who generates things out of the Ur"

, and means primeval generation, or "the one who generates things out of the Ur"