Shaun Greenhalgh [Sean Greenhouse] [and George Greenlaugh and Olive Greenlaugh] [George Greenhouse and Olive Greenhouse]by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/22/22

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Shaun Greenhalgh

Shaun Greenhalgh George Greenhalgh

George Greenhalgh Olive Greenhalgh

Olive GreenhalghBorn: 19 September 1961, Bromley Cross, Lancashire, England, UK

Criminal status: Released

Parent(s): George and Olive Greenhalgh

Criminal charge: Conspiracy to commit fraud, money laundering

Penalty: 4 years and 8 months in prison

Shaun Greenhalgh (born 1961) is a British artist and former art forger. Over a seventeen-year period, between 1989 and 2006, he produced a large number of forgeries. With the assistance of his brother and elderly parents, who fronted the sales side of the operation, he successfully sold his fakes internationally to museums, auction houses, and private buyers, accruing nearly £1 million.[1]

The family have been described by Scotland Yard as "possibly the most diverse forgery team in the world, ever". However, when they attempted to sell three Assyrian reliefs using the same provenance as they had previously, suspicions were finally raised.[2]

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London held an exhibition of Greenhalgh's works from 23 January to 7 February 2010.[3]

The Metropolitan Police's Art and Antiques Unit built a replica model of the shed where the works were created. Many of Greenhalgh's fakes, including the Amarna Princess, a version of the Roman Risley Park Lanx, and works supposedly by Barbara Hepworth and Thomas Moran, were displayed.[4]

Family rolesGreenhalgh's family was involved in "the garden shed gang". They established an elaborate cottage industry at his parents' house in The Crescent, Bromley Cross, South Turton, which is about 3.5 miles (6 km) north of Bolton town centre.[3] His parents, George and Olive, approached clients, while his older brother, George Jr., managed the money.[5][6][7]

Other members of the family were invoked to help establish the legitimacy of the fake items. These included Olive's father who owned an art gallery,[8] a great-grandfather who it seemed had had the foresight to buy well at auctions,[2] and an ancestor who had apparently worked for the Mayor of Bolton as a cleaner and was given a Thomas Moran paintng.[5]

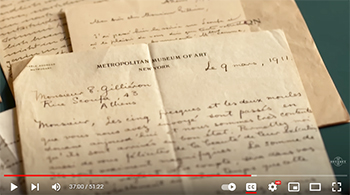

Shaun Greenhalgh left school at 16 with no qualifications.[9] A self-taught artist, undoubtedly influenced by his job as an antiques dealer, he worked up his forgeries from sketches, photographs, art books and catalogues.[2][5][10] He attempted a wide range of crafts, from painting in pastels and watercolours, to sketches, and sculpture, both modern and ancient, busts and statues, to bas-relief and metalwork. He invested in a large range of different materials – silver, stone, marble, rare stone, replica metal, and glass.[2][5] He also did meticulous research to authenticate his items with histories and provenance (for instance, faking letters from the supposed artists) in order to demonstrate his ownership.[11] Completed items were then stored about the house and garden shed. The latter probably served as a workshop as well.

Detective Constable Ian Lawson of Scotland Yard, who searched the house, gave an indication of Greenhalgh's activities:

There were blocks of stone, a furnace for melting silver on top of the fridge, half-finished and rejected sculptures, a watercolour under the bed, a cheque for £20,000 dated 1993, and a bust of an American president in the loft. I’d never seen anything like it.[2]

A next-door neighbour recalled: "I was finding bits of pottery and coins around the edges of the garden over 20 years back – [things like] bits of metal with old kings on."[12] While this sounds as though materials were openly displayed, it was perhaps not quite that obvious. Angela Thomas, a curator from the Bolton Museum, actually visited the family at home prior to the purchase of the Amarna Princess and reported nothing untoward.[11]

Yet for all his daring – he once boasted that he could create a Thomas Moran watercolour in half an hour[5] and claimed to have completed an "Amarna" statue in three weeks – Shaun Greenhalgh needed the help of his parents.[11] At the trial it was said by the lawyer, Brian McKenna, that Greenhalgh's mother, Olive (1925–2016),[13] made the telephone calls "because he was shy and did not like to use the telephone."[14]

Olive may have been a peripheral figure,[14] but Shaun's father, George (1923–2014),[13] was more involved. He was the frontman, who met face-to-face with potential buyers. "He looks honest, he's elderly and he shows up in a wheelchair."[15] For example, George Sr. told the Bolton Museum that he was "thinking about using [the Amarna Princess statue] as a garden ornament".[5]

Greenhalgh's parents helped establish a logical explanation for why the Greenhalghs had possession of such items in the first place, namely as family heirlooms. It allowed them to offload items when they were discovered as fakes, such as the "Eadred Reliquary", and an L.S. Lowry painting, The Meeting House.[2][11][16][17]

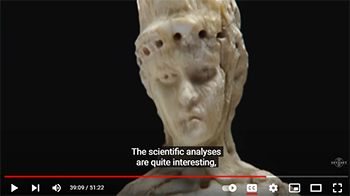

The Amarna Princess The Amarna Princess

The Amarna PrincessMain article: Amarna Princess

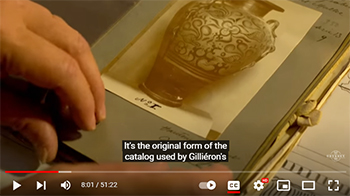

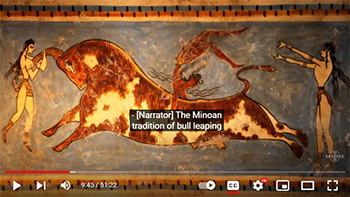

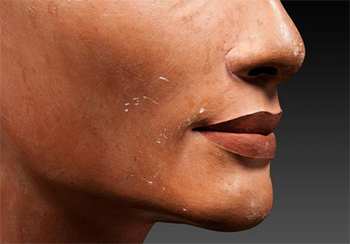

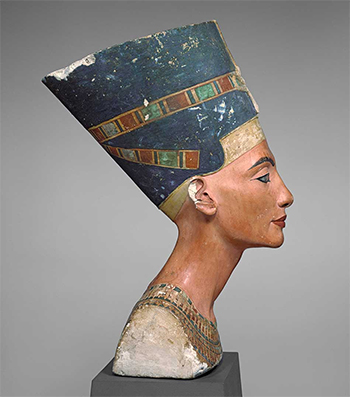

In 1999, the Greenhalghs began their most ambitious project.[5] They bought an 1892 catalogue which listed the contents of an auction in Silverton Park, Devon, the home of the 4th Earl of Egremont. Among the items listed were "eight Egyptian figures."[18] Using the leeway this vague description allowed, Greenhalgh manufactured what became known as the Amarna Princess, a 20-inch statue, apparently made of a translucent alabaster. It later emerged within a Panorama documentary that he had bought the tools to produce this "masterpiece" from B&Q."[16]

Done in the Egyptian "Amarna period" style of 1350 BC, the statue represents one of the daughters of the Pharaoh Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti. At the time, as Greenhalgh had researched, only two other similar statuettes were known to exist in the world.[5][19] He "knocked up" his copy in his shed in three weeks out of calcite, "using basic DIY tools and making it look old by coating it in a mixture of tea and clay".[5][16]

George then approached Bolton Museum in 2002,[14] claiming the Amarna Princess was from his grandfather's "forgotten collection", bought at the Silverton Park auction.[2] He pretended to be ignorant about its true worth or value, but was careful to provide the letters Shaun had also faked, showing how the artefact had been in the family for "a hundred years".[5][16]

In 2003, after consulting experts at the British Museum and Christie's, the Bolton Museum bought the Amarna Princess for £439,767. It remained on display until February 2006. It has been subsequently re-displayed, since September 2018, as part of Bolton Museum's "Bolton's Egypt" Gallery as an example of fake Egyptian artefacts in the "Obsessions" section .[14]

RevenueHad the Greenhalghs managed to sell all 120 artworks they had offered it is estimated that they could have earned as much as £10m.[2][5][20] This would have made the average value of each piece more than £83,000, although money received varied between £100 (for the Eadred Reliquary) and £440,000 (for the Amarna Princess). The Greenhalghs did not manage to offload most of their works. Many which they did sell, such as the Eadred Reliquary, purportedly were undersold, garnering only minimal amounts.[citation needed] Others, such as the Lowry painting The Meeting House, only gained in value from their repeated resale, which would not have benefited the Greenhalghs.

As time went on, more ambitious, expensive pieces of work were produced, some of which did sell, like the Risley Park Lanx. However, these were subject to more scrutiny and indeed it was one of these, the Assyrian reliefs, which led to their exposure and arrests, which suggests that the longevity of their scam was concentrated on the passing-off of lower level items.[21]

Balanced against this must be the success of sales to private individuals. They are unlikely to have had the same level of expertise at their disposal as institutions, and are probably less willing to advertise their losses once the forgeries were detected. Certainly they have not had the same exposure as the debacle surrounding the Bolton Museum, for example.[11] Two individual buyers, "wealthy Americans" have been identified, but only after they donated their purchase to the British Museum.[5]

Another piece sold to an unnamed private buyer came to light when the Art Institute of Chicago announced that The Faun, a ceramic sculpture on display since 1997 as the work of the 19th-century French master Paul Gauguin, was also a forgery by Shaun Greenhalgh. The museum purchased the sculpture from a private dealer in London, who had bought it at a Sotheby's auction in 1994.[22]

In addition, the bank records of the Greenhalghs only went back six years,[19] so in the final analysis the exact amount of monies involved over the seventeen-year scam has not been determined. What is known is that "two Halifax accounts... one containing £55,173 and the other £303,646" were frozen, pending a confiscation hearing in January 2008, and Shaun Greenhalgh was convicted for "conspiracy to conceal and transfer £410,392."[14] Estimates of the amount of money the Greenhalghs actually made vary from £850,000 to £1.5 million.[5][15]

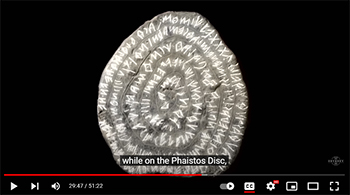

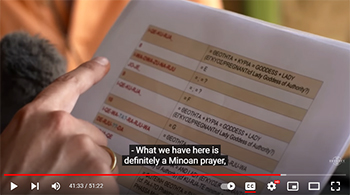

ExposurePossibly encouraged by their success in fooling experts, the Greenhalghs tried again using the same Silverton Park provenance. They produced what were purportedly three Assyrian reliefs of soldier and horses, from the Palace of Sennacherib in 600 BC.[5]

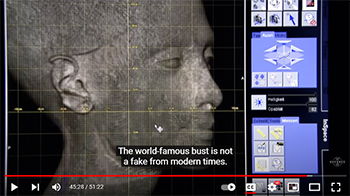

The British Museum examined them in November 2005, concluded that they were genuine, and expressed an interest in buying one of them, which seemed to match a drawing by A. H. Layard in its collection. However, when two of the reliefs were submitted to Bonhams auction house, its antiquities consultant Richard Falkiner spotted "an obvious fake".[23]

Bonhams consulted with the British Museum about various suspicious aspects, and the museum then spotted several improbable anomalies. The horses' reins were "not consistent"[15] or "atypical" with respect to other Assyrian reliefs; and the cuneiform inscription contained a spelling mistake,[5] an absent diacritical mark, which was considered extremely unlikely in a piece "destined for the eyes of the king". These concerns became full blown suspicion when George seemed too willing to part with the items at a low price.[10] The museum contacted the police, who investigated the Greenhalghs for the next 20 months.[24]

Court case, convictions and sentencingAt their trial at Bolton Crown Court in 2007, the three defendants pleaded guilty to creating the forgeries and laundering the money they received.[25] On 16 November, Shaun Greenhalgh was sentenced to 4 years and eight months, while his mother received a 12 month suspended sentence. The parents were using wheelchairs at their appearance for sentencing.[25] Judge William Morris, in sentencing Shaun Greenhalgh, stated: "This was an ambitious conspiracy of long duration based on your undoubted talent and based on the sophistication of the deceptions underpinning the sales and attempted sales. I speak of your talent but not in admiration. Your talent was misapplied to the ends of dishonest gain."[26] George Greenhalgh's sentence was delayed for medical reports in 2007,[25] eventually he received a suspended sentence of two years. If his age had not been grounds for mitigation, Judge William Morris said, he would have been sentenced to 31⁄2 years imprisonment. The prison service was unable to hold someone with his infirmities.[27]

Detective Sergeant Vernon Rapley, from the Metropolitan Police Arts and Antiquities Unit said shortly after the Greenhalgh's were sentenced: "Looking at them now I'm not sure the items would fool anyone, it was the credibility of the provenances that went with them."[16] The list of experts and institutions who were fooled is long, and includes the Tate Modern,[5] the British Museum, the Henry Moore Institute, and auction houses Bonhams, Christie's, Sotheby's and other experts from "Leeds to Vienna."[19] The Faun was displayed at the van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam;[28] while the Amarna Princess went on display at the South Bank Hayward Art Gallery, in an exhibition opened by the Queen.[7] Other unnamed galleries, and various private collectors were fooled as well.[5]

Motivations and aftermathThe Greenhalgh family did not appear to make much use of the money they gained. They lived a "far from lavish life"[2] in a "shabby"[5] council house; among their possessions were "an old TV, battered sofa, and a Ford Focus", but not a computer.[2][16] According to Detective Sgt Rapley of the Metropolitan Police, the conditions were "relatively frugal" even "abject poverty".[19] Olive Greenhalgh claimed that she had "not even travelled outside of Bolton."[16]

As they did not display wealth, explanations other than desire for money have been proposed. Police suggested that Shaun Greenhalgh was motivated less by profit than by resentment at his own lack of recognition as an artist. This "general hatred"[16] became a need to "shame the art world" and "show them up", but this was denied by Greenhalgh in his autobiography, A Forger's Tale. The defence lawyer Andrew Nutall characterized Shaun Greenhalgh as a shy, introverted person, obsessed with "one outlook and that was his garden shed". The forgeries were an attempt to "perfect the love he had for such arts". By implication, the forgeries were a mere unintended, if unfortunate, consequence.[19]

In fact, institutions proclaimed the works and their achievement in obtaining them. The Art Institute of Chicago described The Faun sculpture as a "major rediscovery" and included it in their "definitive" exhibition on Gauguin.[28] Bolton Museum hailed their purchase of the Amarna Princess as "a coup," calling George Greenhalgh "a nice old man who had no idea of the significance of what he owned."[11]

After the trial, Bolton Museum scrambled to distance itself and described itself as "blameless"[11] insisting that it had followed established procedure.[14] The presiding judge, William Morris, exonerated the institution and any Council staff involved, preferring to focus on what he saw as "misapplied" talent and an "ambitious conspiracy;"[14] while the Metropolitan Police Arts and Antiquities Unit would only admit that Greenhalgh had succeeded "to a degree".[19]

However, the general public was notably more cynical in its reaction, being unimpressed by what they perceived as the experts' incompetence, and the law's heavy-handedness.[2] Richard Falkiner, the antiquities expert from Bonhams said, "I took one look at the relief and said 'don't make me laugh'...It was an obvious fake. It was far too freshly cut, was made of the wrong stone and was stylistically wrong for the period."[23]

Known forgeries Greenhalgh's The Faun, which was passed off for a sculpture by Gauguin

Greenhalgh's The Faun, which was passed off for a sculpture by GauguinDuring the trial, 44 forgeries were discussed, while 120 were known to have been presented to various institutions.[2][14] However, given the family's bank records only extended back for a third of the period they were operating, and Shaun Greenhalgh's high level of productivity, there are probably many more. On raiding the Greenhalgh home police discovered many raw materials and "scores of sculptures, paintings and artifacts, hidden in wardrobes, under their bed and in the garden shed."[15] In fact, "there can be little doubt that there are a number of forgeries still circulating within the art market."[19]

A description of known forgeries includes:

• 1989. Eadred Reliquary. A small 10th century silver vessel, containing a relic of the true cross of Jerusalem. George Greenhalgh turned up "dripping wet" at Manchester University, claiming he'd found it in a river terrace, at Preston. University determined vessel was a fake; but unsure about the wood. Purchased it for £100.[29] The subject of an academic thesis.[19]

• 1990. Samuel Peploe still life painting, purportedly inherited from Olive's grandfather, sold for £20,000. However, paint began to flake off and the buyer cancelled the cheque. Scotland Yard failed to make an arrest at the time due to "organisational restraints."[30][31]

• 1992. The Risley Park Lanx. A Roman silver plate bought for £100,000 by private buyers and donated to the British Museum, who displayed it as a genuine replica.[31][32]

• 1993–1994. Thomas Moran sketch and watercolour acquired by Bolton Museum. "The former was a gift given by the Greenhalghs; the latter was purchased for £10,000."[33]

• 1994. The Faun. A ceramic sculpture by Paul Gauguin. Authenticated by the Wildenstein Institute, sold at Sothebys auction in 1994 for £20,700 to private London dealers, Howie & Pillar. Bought by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1997 for $125,000. On display until October 2007.[28]

• 1995. Anglo-Saxon ring. Tried to sell it through Phillips Auctioneers; determined by British Museum to be a fake.[31]

• 1995. 24 sketches by Thomas Moran sold in New York. Police believe up to 40, worth up to £10,000, were created by Greenhalgh, six or seven of which are unaccounted for. He claimed each one only took him thirty minutes to forge, and that a former mayor of Bolton had given them to an ancestor of his who worked for the mayor as a cleaner.[5][8][34]

• L.S. Lowry. The Meeting House (a pastel, one of a "clutch of paintings").[2][5][16] The Greenhalghs claimed it was a 21st birthday present by Olive's gallery owner father,[8] and even that some were given by Lowry himself. They had copied letters from the artist, inserting their names in to make it look like they were great friends. For example, this letter dated 16 June 1946:

Dear George, Thank you very much for your recent letter and cheque for the paintings. I have about finished the [illegible] but I will hold onto it untill I am(?) ready. I will slip round to the yard on Wed. L S Lowry. Received 45.0.0 for paintings

One of the Lowrys, perhaps the one mentioned above, sold as a replica, for somewhere between "several hundred pounds"[8] and £5,000. Eventually put up for auction by new owners in Kent as genuine item, for £70,000.[2]

• 1999. Two gold Roman ornaments. George Greenhalgh withdrew them from Christie's when the auction house wanted to do a scientific analysis on them.[31]

• Barbara Hepworth goose sculpture. Only a photograph known to exist, before item lost in the late 1920s. The Greenhalghs claimed it was given to the family "by the curator of a museum in Leeds" in the 1950s. Worth approximately £200,000 it was later sold to the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds for £3,000.[5][8][29]

• Work by Otto Dix. Stolen from Dresden in 1939. Apparently recovered by the Greenhalghs then presented to the Tate Gallery .[12]

• Work by Man Ray.[12]

• Another Paul Gauguin, a vase.[35]

• An ancient Celtic fibula (or brooch)[15]

• Horatio Greenough. Bust of Thomas Jefferson,[5] sold at Sotheby's for £48,000.[31] And/or Thomas Chatterton[34]

• Henry Moore. A carved stone head by Henry Moore, which Greenhalgh Snr tried to convince the Tate Modern, London to buy, claiming to have got it via his grandmother.[5]

• 2003 Amarna Princess, a statuette. In the family for "a hundred years." Authenticated by the British Museum and Sothebys, bought by Bolton Museum for £440,000, it was on display for three years. A police raid on the Greenhalgh home discovered two more copies.[2][5][16][30]

• 2005. Three Assyrian marble reliefs from Nineveh, including one of an eagle-headed genie and another of soldiers and horses. They were dated by the British Museum at around 681BC, supposedly from the Palace of Sennacherib, and thought to be worth around £250,000 to £300,000. But alerted by Bonhams, their discrepancies were revealed, and the forgery exposed.[5][9][16][23]

Career after releaseFollowing Shaun Greenhalgh's release in early 2010, he launched a website selling his artworks. These comprise works the website describes as "examples of my old style of work...'fakes'," signed and sold as works by him, as well as sculptures in his own style. A member of the Metropolitan Police Art and Antique Squad stated "If a work is not copyrighted, it is not illegal to copy that work and sell that copy, as long as it is made very clear the work is not an original."[36]

La Bella Principessa claim La Bella Principessa on display at Villa Reale Monza in 2015

La Bella Principessa on display at Villa Reale Monza in 2015In November 2015 as part of the publicity for the upcoming A Forger's Tale, an article in The Sunday Times put forward Greenhalgh's claim that he was the creator of La Bella Principessa attributed to Leonardo da Vinci.[37]

A December 2015 article in The New York Times also promoted Greenhalgh's claimed authorship of the work, which it said he had made in the late 1970s, around the age of 20, using vellum recycled from a 16th-century land deed and the face of a supermarket check-out girl named "Alison" who worked in Bolton.[38]

Greenhalgh repeated his claim to be the creator in a May 2017 interview with Simon Parkin in The Guardian, observing that he had studied the work again when it was exhibited at the Villa Reale di Monza in 2015.[39] The Postscript chapter in Greenhalgh's 2017 autobiography provided further details about his claim, identifying the sitter as "Bossy Sally from the Co-Op" (p. 356).

Art historian Martin Kemp said he found the claim hilarious and ridiculous.[40]

Television programmesOn 4 January 2009, BBC Two broadcast a dramatisation of the Greenhalgh story called The Antiques Rogue Show, a play on the title of the BBC series Antiques Road Show,[41] already used by headline writers. In a letter from prison to the Bolton News, Shaun Greenhalgh complained about the depiction of himself and his family, calling the drama "character assassination".[42]

Shaun Greenhalgh appeared in the 2012 BBC documentary The Dark Ages: An Age of Light and is listed as "Craftsman" in the credits.[43]

In October 2019, he appeared in Handmade in Bolton on BBC2, a short documentary series fronted by Janina Ramirez, directed and narrated by Waldemar Januszczak, in which he remade four objects from the past using traditional materials and methods.[44]

AutobiographyHis autobiography A Forger's Tale: Confessions of the Bolton Forger was originally published in a limited edition in 2015 by ZCZ Editions. The first full edition was published on 1 June 2017 with an Introduction by Waldemar Januszczak.[45] It won The Observer's Best Art Book of the Year, 2018.

References1. The Guardian "How garden shed fakers fooled the art world", 16 November 2007.

2. O’Neill, Sean; Jenkins, Russell (17 November 2007). "The £10m art collection that was forged by a family in their garden shed in Bolton". The Times. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011.

3. "Armana Pricess: "I dismantled art forgers work without realising"". Bolton News. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

4. "The Metropolitan Police Service's Investigation of Fakes and Forgeries – V&A future exhibitions". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

5. "The artful codgers: pensioners who conned British museums with £10m forgeries". This is London. 16 November 2007.

6. Smith, Amanda (21 April 2007). "£1m fake statue: family charged". The Bolton News.

7. Stokes, Paul (1 August 2007). "Family sells fake Egyptian statue for £400,000". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007.

8. Chadwick, Edward (17 November 2007). "Antiques Rogues Show: Update 3". The Bolton News.

9. Chadwick, Edward (21 November 2007). "Con artist set to appeal". The Bolton News.

10. Milmo, Cahal (19 November 2007). "Family of forgers fool art world with beautifully crafted fakes". New Zealand Herald.

11. Linton, Deborah. "Family con that fooled the art world", Manchester Evening News, 16 November 2007.

12. Grove, Sophie. "Fake It Till You Make It", Newsweek, 15 December 2007.

13. "Guardian interview for A Forger's Tale". Retrieved 15 November 2020.

14. Chadwick, Edward. "Antiques rogues show update", The Bolton News, 17 November 2007.

15. "Elderly couple, son sentenced for creating knockoff art and antiques for 17 years". International Herald Tribune. 16 November 2007.

16. Kelly, James (17 November 2007). "Fraudsters who resented the art market". BBC News.

17. See also discussion of this in Reactions section.

18. Malvern, Jack. "The ancient Egypt statue from Bolton (circa 2003)", Times Online, 27 March 2006.

19. Ward, David (17 November 2007). "How garden shed fakers fooled the art world". The Guardian.

20. "Authentication in Art List of Unmasked Forgers".

21. Thompson, Clive. "How to make a fake", New York Magazine, 24 May 2004; accessed 26 December 2007.

22. Artner, Alan. "Art Institute of Chicago discloses Gauguin sculpture in fact a forgery", Chicago Tribune, 12 December 2007.

23. Macquisten, Ivan. "It was Bonhams and ATG columnist who first raised alarm over Greenhalgh fakes", Antiques Trade Gazette, 3 December 2007.

24. Hundley, Tom (11 February 2008). "A masterpiece of deception". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

25. Lovell, Jeremy (16 November 2007). "82-year-old art forger sentenced". Reuters. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

26. "British art forger jailed for four years". The Irish Times. PA. 16 November 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

27. Pallister, David; Carter, Helen (29 January 2008). "Curtain falls on antiques rogue show as last of family forgers convicted". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

28. Bailey, Martin (12 December 2007). "Revealed: Art Institute of Chicago Gaugain sculpture is fake". The Art Newspaper.

29. Bunyan, Paul (18 November 2007). "Downfall of council house art fakers". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007.

30. Flynn, Tom. "Faking It" (PDF). Art Quarterly (Summer 2007). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2011.

31. Pallister, David. "Background:'The antique road show,", Guardian, 28 January 2008.

32. British Museum: The Risley Park Lanx (copy), replica, lanx, Romano-British, Risley Park

33. Bolton Museum, (no byline). "Amarna Princess statement" Archived 20 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Bolton Museum, 29 November 2007.

34. Milmo, Cahal (17 November 2007). "Family of forgers fooled art world with array of finely crafted". The Independent. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

35. Lovell, Jeremy (17 November 2007). "Octogenarian British art forger sentenced". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

36. "Bolton Evening News article". 2 December 2011.

37. Boswell, Josh; Rayment, Tim (29 November 2015). "'It's not a da Vinci, it's Sally from the Co-op'". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 1 December 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

38. Reyburn, Scott (4 December 2015). "An Art World Mystery Worthy of Leonardo". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

39. 'I wasn’t cock-a-hoop that I’d fooled the experts': Britain's master forger tells all

40. Kemp, Martin (29 November 2015). "La Bella Principessa is a "forgery"!!!". Martin Kemp's This and That.

41. "BBC programme details".

42. Paul Keavaney (27 January 2009). "I do not believe my family has been portrayed fairly". The Bolton News.

43. The Dark Ages: An Age of Light, episode # 4.

44. BBC: Handmade in Bolton

45. Greenhalgh, Shaun (2017). A Forger's Tale: Confessions of the Bolton Forger (first ed.). London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781760295271.

Sources• Artner, Alan. "Art Institute of Chicago discloses Gauguin sculpture in fact a forgery", Chicago Tribune, 12 December 2007; accessed 13 December 2007.

• Bolton Museum, (no byline). "Amarna Princess statement", Bolton Museum, 29 November 2007; accessed 15 December 2007.

• Bailey, Martin. "Revealed: Art Institute of Chicago Gaugain sculpture is fake", The Art Newspaper, 12 December 2007; accessed 13 December 2007.

• Bunyan, Nigel. "Downfall of council house art fakers", Telegraph, 18 November 2007; accessed 13 December 2007.

• Chadwick, Edward. "Antiques rogues show update", The Bolton News, 17 November 2007; accessed 18 November 2007.

• Chadwick, Edward. "Antiques rogues show: update 3", The Bolton News, 17 November 2007; accessed 30 November 2007.

• Chadwick, Edward. "Con artist set to appeal", The Bolton News, 21 November 2007; accessed 30 November 2007.

• Fenton, James. "Fakes and counterfeits", The Guardian, 24 November 2007; accessed 30 November 2007.

• Flynn, Tom. "Faking It", Art Quarterly, Summer 2007; accessed 13 December 2007.

• International Herald Tribune (no byline). "Elderly couple, son sentenced for creating knockoff art and antiques for 17 years", International Herald Tribune, 16 November 2007; accessed 18 November 2007.

• Grove, Sophie. "Fake It Till You Make It", Newsweek, 15 December 2007; accessed 17 December 2007.

• Kelly, James. "Fraudsters who resented the art market", BBC News, 16 November 2007; accessed 17 November 2007.

• Linton, Deborah. "Family con that fooled the art world", Manchester Evening News, 16 November 2007; accessed 18 November 2007.

• Lovell, Jeremy. "Octogenarian British art forger sentenced", New Zealand Herald, 17 November 2007; accessed 20 November 2007.

• Macquisten, Ivan. "It was Bonhams and ATG columnist who first raised alarm over Greenhalgh fakes", Antiques Trade Gazette, 3 December 2007; accessed 17 December 2007.

• Milmo, Cahal. "Family of forgers fool art world with beautifully crafted fakes", New Zealand Herald, 19 November 2007; accessed 20 November 2007.

• Milmo, Cahal. "Family of forgers fooled art world with array of finely crafted", Independent, 17 November 2007; accessed 13 December 2007.

• Smith, Amanda. "£1m fake statue: family charged", The Bolton News, 21 April 2007; accessed 30 November 2007.

• Stokes, Paul. " Family sells fake Egyptian statue for £400,000", Telegraph, 1 August 2007. Accessed 30 November 2007.

• This Is London, (no byline). "The artful codgers: pensioners who conned British museums with £10m forgeries", This Is London, 16 November 2007; accessed 18 November 2007.

• Times Online, (no byline). "Octogenarian art-forgers bought to justice", Times Online, 16 November 2007; accessed 22 November 2007.

• Thompson, Clive. "How to make a fake", New York Magazine, 24 May 2004; accessed 26 December 2007.

• Ward, David. "How garden shed fakers fooled the art world", The Guardian, 17 November 2007; accessed 17 November 2007.

*************************

Art Institute of Chicago discloses Gauguin sculpture in fact a forgery: Sculpture sold as a Gauguin is fakeBy Alan G. Artner

Tribune art critic

December 12, 2007

Faun Sculpture Chicago Art Institute. The Art Institute of Chicago has discovered that a sculpture alleged to be a 19th Century work by Paul Gauguin is a forgery. (Photo courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago / December 11, 2007)

Faun Sculpture Chicago Art Institute. The Art Institute of Chicago has discovered that a sculpture alleged to be a 19th Century work by Paul Gauguin is a forgery. (Photo courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago / December 11, 2007)For about a decade, “The Faun,” a ceramic sculpture, has been at the Art Institute of Chicago, presented as a work of the 19th Century French master Paul Gauguin.

On Tuesday, the museum announced that the work, which it bought in 1997, is a forgery. “The Faun” has been confirmed to be one of a long string of contemporary forgeries by the Greenhalgh family, which Scotland Yard had been investigating for 20 months.

The museum purchased the sculpture from a private dealer in London, who had bought it at a Sotheby’s auction in 1994.

“Everyone who bought and sold [the work] did so in good faith,” said Erin Hogan, director of public affairs at the institute.

“No one could think of any other instance in which anything like this happened here,” Hogan said. “So we don’t have experience in this area. We’re talking to both Sotheby’s and the private dealer about how to proceed” to get compensated for the money it spent to buy the work. As is customary, the institute did not reveal the purchase price.

The piece was the object of art historical research upon acquisition, but there was no reason to believe it was anything other than represented, Hogan said.

The sculpture was on display at the museum until October. Shaun Greenhalgh, who made all the objects forged by the family, confessed to authorities that “The Faun” was his handiwork. The family had consigned it to Sotheby’s.

Buyers at major auctions generally are protected by an indemnification clause that allows the sale to be rescinded if the works turn out to be inauthentic. Sotheby’s might go back to the Greenhalgh family to refund the purchase price.

Shaun Greenhalgh received a prison sentence of 4 years and 8 months last month. His mother, Olive, 83, was given a 12-month suspended sentence. The father, George, 84, salesman of all the forged objects, had a deferred sentence pending medical reports.

For 17 years, the family carried on one of the most sophisticated forgery operations in modern history, faking scores of objects including antiquities, watercolors, paintings and modern sculpture, authorities said. Many of the pieces were copies of ancient objects or artworks thought to be lost.

Their “reappearance” caused great excitement. Family members brought several pieces to experts and museums with elaborate stories of inheritance. Detailed accounts of previous owners also were supplied — and also were invented.

According to the Daily Mail in London, “the conspiracy secured them around 1.2 million [euros],” or about $1.77 million. “Had all the items forged been sold, experts estimated the family could have earned as much as 14 million [euros],” or about $20.6 million.

———–

[email protected]***************************

Jailed for Fake Statue: Forgery factory run from council houseFamily's 17-year con with forged paintings, documents and artifacts Worth Millions

by The Bolton News

17th November 2007

AN elderly couple and their son who tricked Bolton Council into parting with £440,000 for a fake statue conned the art world with a string of elaborate schemes for nearly two decades.Shaun Greenhalgh was a talented artist and sculptor who used his skills to create copies of rare and sought-after masterpieces at the family's home in The Crescent, Bromley Cross.

His wheelchair-bound father, George, aged 84, acted as a convincing salesman and provided carefully researched stories about the origins of every fake they passed off as real.

Olive Greenhalgh, aged 83, made phone calls to unwitting buyers to arrange meetings.

The artworks included a copy of the 3,300-year-old Amarna Princess statue bought by Bolton Council in 2003 after being convinced by George Greenhalgh that it was a family heirloom.

Instead, it was the family's most elaborate and audacious con - and even fooled Egyptology experts at the British Museum.It was revealed at Bolton Crown Court yesterday that Shaun Greenhalgh, aged 47 - a self-taught artist - had carved it himself in a garden shed in just three weeks.

The deceit was exposed only when other stone carvings, purported to date from 900BC, were spotted to be modern copies.The court heard about 44 other items which the family sold or attempted to sell between 1989 and 2006 - among them copies of work by LS Lowry, Paul Gaugin and Bolton-born painter Thomas Moran.

Detectives say dozens of fakes may still be in circulation.Shaun Greenhalgh was jailed for four years and eight months after admitting defrauding art institutions between 1989 and 2006 and conspiracy to conceal and transfer £410,392.

His mother was given a 12-month suspended sentence and her husband will be sentenced at a later date pending medical reports.

But Judge William Morris made it clear the pensioner was facing a jail term.

Both admitted the same charges as their son.

The judge told Shaun Greenhalgh: "This was an ambitious conspiracy of long duration based on your undoubted talent and based on the sophistication of the deceptions underpinning the sales and attempted sales.

"I speak of your talent but not in admiration. Your talent was misapplied to the ends of dishonest gain."

Judge Morris said the fraud had cheated private collectors and galleries out of £850,000.Bolton Museum was approached by George Greenhalgh in 2002. He asked staff if they would like to view the 20-inch statue which he said had been passed down from his great-grandfather.

He told them he knew little of Egyptian antiquities and said the item had been valued at £500 before allowing the member of staff to take it away for examination.

His claims were backed up by a catalogue from the sale of a house and its contents in 1892.

Shaun Greenhalgh used details in the catalogue to manufacture a copy of the statue, said Peter Cadwallader, prosecuting.

The figure was taken to Christie's and the British Museum where experts said it was genuine after comparing it to a similar item at the Louvre in Paris.

After Bolton Council paid £439,767 to the family, the purchase was hailed as a coup as the statue was believed to be worth £1 million.

It was said to represent one of the daughters of Pharaoh Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti, the mother of Tutankhamun.It remained on show until February, 2006.

Curators at the British Museum called police when they became suspicious about three pieces of stone with raised "reliefs" which were offered to them by George Greenhalgh in October, 2005.

Although they were initially believed to be genuine and worth as much as £250,000, experts at the museum and Bonham's auctioneers realised they were fakes and phoned police.

In February, 2006, Bolton Museum was contacted by the Metropolitan Police's arts and antiques unit which raised doubts about the Amarna Princess.

The purchase was funded by grants as well as a donation of £4,000 from the Friends of Bolton Museum.

Judge Morris said there could be no criticism of anybody within the council or museum for falling for the con.

Andrew Nuttall, defending Shaun Greenhalgh, said: "As an artist, Shaun Greenhalgh does not have a style of his own. What he can do is copy.

"He was completely self-taught. In some respects that may make him unique."

Brian McKenna, defending Mrs Greenhalgh, said she had made phonecalls on behalf of her son because he was shy and did not like to use the telephone.

"In terms of involvement in this conspiracy, she was on the periphery, but it would be wrong of me to suggest that she did not know what was going on," he said.

Outside court, Stephanie Crossley, assistant director of adult services at Bolton council, said the incident had been "regrettable but the council carefully followed established practice.

She added: "We welcome the judge's comments. He said that we were victims of the most clever deception'.

"The museum did not rely on its own judgment. He said that he could see no criticism of Bolton Museum in what it had done and no criticism of any individual."

No council money had been contributed towards the sale, she added.

Two Halifax accounts in the name of Shaun Greenhalgh, one containing £55,173 and the other £303,646, have been frozen and a confiscation hearing will be held at Bolton Crown Court on January 25 next year.