by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/2/23

-- Manu (Hinduism), by Wikipedia

-- Manusmriti, by Wikipedia

-- Institutes of Hindu Law: Or, The Ordinances of Menu, According to the Gloss of Culluca. Comprising the Indian System of Duties, Religious and Civil, Verbally translated from the original Sanscrit, With a Preface, by Sir William Jones

-- Matsya, by Wikipedia

-- Sethona. A Tragedy. As it is Performed at the Theatre-Royal in Drury-Lane, by Alexander Dow

-- Menes [Mneues], by Wikipedia

-- Mannus, by Wikipedia

Menes

Africanus: Mênês

Eusebius: Mênês

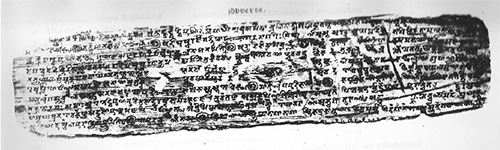

The cartouche of Menes on the Abydos King List

Pharaoh

Reign c. 3200–3000 BC[1] (First Dynasty)

Successor Hor-Aha (possibly)

Royal titulary

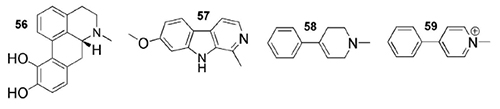

Menes (fl. c. 3200–3000 BC;[1] /ˈmeɪneɪz/; Ancient Egyptian: mnj, probably pronounced */maˈnij/;[6] Ancient Greek: Μήνης[5]) was a pharaoh of the Early Dynastic Period of ancient Egypt credited by classical tradition with having united Upper and Lower Egypt and as the founder of the First Dynasty.[7]

The identity of Menes is the subject of ongoing debate, although mainstream Egyptological consensus identifies Menes with the Naqada III ruler Narmer[2][3][4][8] or First Dynasty pharaoh Hor-Aha.[9] Both pharaohs are credited with the unification of Egypt to different degrees by various authorities.

Name and identity

The commonly-used name Menes derives from Manetho, an Egyptian historian and priest who lived during the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Manetho noted the name in Greek as Μήνης (transliterated: Mênês).[5][10] An alternative Greek form, Μιν (transliterated: Min), was cited by the fifth-century-BC historian Herodotus,[11] but this variant is no longer accepted; it appears to have been the result of contamination from the name of the god Min.[12] The Egyptian form, mnj, is taken from the Turin and Abydos King Lists, which are dated to the Nineteenth Dynasty, whose pronunciation has been reconstructed as */maˈnij/. By the early New Kingdom, changes in the Egyptian language meant his name was already pronounced */maˈneʔ/.[13] The name mnj means "He who endures", which, I.E.S. Edwards (1971) suggests, may have been coined as "a mere descriptive epithet denoting a semi-legendary hero [...] whose name had been lost".[5] Rather than a particular person, the name may conceal collectively the Naqada III rulers: Ka, Scorpion II and Narmer.[5]

Narmer and Menes

Two Horus names of Hor-Aha (left) and a name of Menes (right) in hieroglyphs.

Main article: Narmer

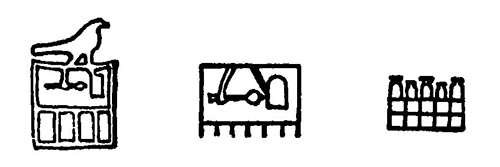

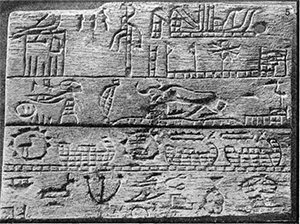

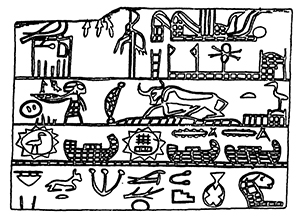

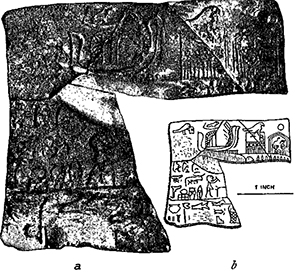

Ivory tablet of Menes

The ivory label mentioning Hor-Aha along with the mn sign.

Reconstructed tablet.

The almost complete absence of any mention of Menes in the archaeological record[5] and the comparative wealth of evidence of Narmer, a protodynastic figure credited by posterity and in the archaeological record with a firm claim[3] to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, has given rise to a theory identifying Menes with Narmer.

The chief archaeological reference to Menes is an ivory label from Naqada which shows the royal Horus-name Aha (the pharaoh Hor-Aha) next to a building, within which is the royal nebty-name mn,[14] generally taken to be Menes.[5][a] From this, various theories on the nature of the building (a funerary booth or a shrine), the meaning of the word mn (a name or the verb endures) and the relationship between Hor-Aha and Menes (as one person or as successive pharaohs) have arisen.[2]

The Turin and Abydos king lists, generally accepted to be correct,[2] list the nesu-bit-names of the pharaohs, not their Horus-names,[3] and are vital to the potential reconciliation of the various records: the nesu-bit-names of the king lists, the Horus-names of the archaeological record and the number of pharaohs in Dynasty I according to Manetho and other historical sources.[3]

Flinders Petrie first attempted this task,[3] associating Iti with Djer as the third pharaoh of Dynasty I, Teti (Turin) (or another Iti (Abydos)) with Hor-Aha as second pharaoh, and Menes (a nebty-name) with Narmer (a Horus-name) as first pharaoh of Dynasty I.[2][3] Lloyd (1994) finds this succession "extremely probable",[3] and Cervelló-Autuori (2003) categorically states that "Menes is Narmer and the First Dynasty begins with him".[4] However, Seidlmayer (2004) states that it is "a fairly safe inference" that Menes was Hor-Aha.[9]

Two documents have been put forward as proof either that Narmer was Menes or alternatively Hor-Aha was Menes. The first is the "Naqada Label" found at the site of Naqada, in the tomb of Queen Neithhotep, often assumed to have been the mother of Horus Aha.[15]

The commonly used name Hor-Aha is a rendering of the pharaoh's Horus-name, an element of the royal titulary associated with the god Horus, and is more fully given as Horus-Aha meaning Horus the Fighter.

Manetho's record Aegyptiaca (translating to History of Egypt) lists his Greek name as Athothis, or "Athotís".

-- Hor-Aha, by Wikipedia

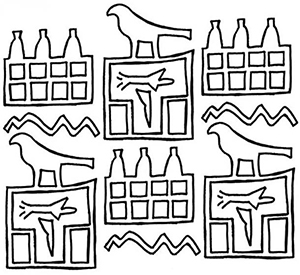

The label shows a serekh of Hor-Aha next to an enclosure inside of which are symbols that have been interpreted by some scholars as the name "Menes". The second is the seal impression from Abydos that alternates between a serekh of Narmer and the chessboard symbol, "mn", which is interpreted as an abbreviation of Menes. Arguments have been made with regard to each of these documents in favour of Narmer or Hor-Aha being Menes, but in neither case is the argument conclusive.[ b]

The second document, the seal impression from Abydos, shows the serekh of Narmer alternating with the gameboard sign (mn), together with its phonetic complement, the n sign, which is always shown when the full name of Menes is written, again representing the name “Menes”. At first glance, this would seem to be strong evidence that Narmer was Menes.[19] However, based on an analysis of other early First Dynasty seal impressions, which contain the name of one or more princes, the seal impression has been interpreted by other scholars as showing the name of a prince of Narmer named Menes, hence Menes was Narmer's successor, Hor-Aha, and thus Hor-Aha was Menes.[20] This was refuted by Cervelló-Autuori 2005, pp. 42–45; but opinions still vary, and the seal impression cannot be said to definitively support either theory.[21]

Herodotus, after having mentioned the first king of Egypt, Min, he wrote that Linus, called by the Egyptians Maneros, was "the only son of the first king of Egypt" and that he died untimely.[22]

Dates

Egyptologists, archaeologists, and scholars from the 19th century have proposed different dates for the era of Menes, or the date of the first dynasty:[23][c]

• John Gardner Wilkinson (1835) – 2320 BC

• Jean-François Champollion (Published posthumously in 1840) – 5867 BC

• August Böckh (1845) – 5702 BC

• Christian Charles Josias Bunsen (1848) – 3623 BC

• Reginald Stuart Poole (1851) – 2717 BC

• Karl Richard Lepsius (1856) – 3892 BC

• Heinrich Karl Brugsch (1859) – 4455 BC

• Franz Joseph Lauth (1869) – 4157 BC

• Auguste Mariette (1871) – 5004 BC

• James Strong (1878) – 2515 BC

• Flinders Petrie (1887) – 4777 BC

Modern consensus dates the era of Menes or the start of the first dynasty between c. 3200–3030 BC; some academic literature uses c. 3000 BC.[1]

History

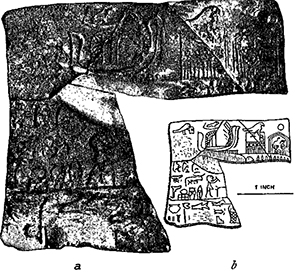

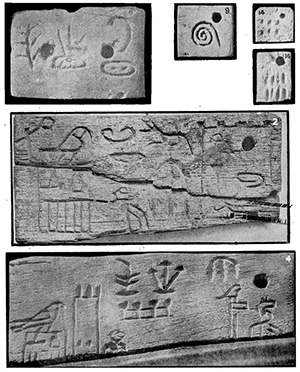

Ebony plaque of Menes in his tomb of Abydos

By 500 BC, mythical and exaggerated claims had made Menes a culture hero, and most of what is known of him comes from a much later time.[24]

Ancient tradition ascribed to Menes the honour of having united Upper and Lower Egypt into a single kingdom[25] and becoming the first pharaoh of the First Dynasty.[26] However, his name does not appear on extant pieces of the Royal Annals (Cairo Stone and Palermo Stone), which is a now-fragmentary king's list that was carved onto a stela during the Fifth Dynasty. He typically appears in later sources as the first human ruler of Egypt, directly inheriting the throne from the god Horus.[27] He also appears in other, much later, king's lists, always as the first human pharaoh of Egypt. Menes also appears in demotic novels of the Hellenistic period, demonstrating that, even that late, he was regarded as an important figure.[28]

Menes was seen as a founding figure for much of the history of ancient Egypt, similar to Romulus in ancient Rome.[29] Manetho records that Menes "led the army across the frontier and won great glory".[10][26]

Capital

Manetho associates the city of Thinis with the Early Dynastic Period and, in particular, Menes, a "Thinite" or native of Thinis.[10][26] Herodotus contradicts Manetho in stating that Menes founded the city of Memphis as his capital[30] after diverting the course of the Nile through the construction of a levee.[31] Manetho ascribes the building of Memphis to Menes' son, Athothis,[26] and calls no pharaohs earlier than Third Dynasty "Memphite".[32]

Herodotus and Manetho's stories of the foundation of Memphis are probably later inventions: in 2012 a relief mentioning the visit to Memphis by Iry-Hor—a predynastic ruler of Upper Egypt reigning before Narmer—was discovered in the Sinai Peninsula, indicating that the city was already in existence in the early 32nd century BC.[33]

Cultural influence

Labels from the tomb of Menes

Diodorus Siculus stated that Menes had introduced the worship of the gods and the practice of sacrifice[34] as well as a more elegant and luxurious style of living.[34] For this latter invention, Menes' memory was dishonoured by the Twenty-fourth Dynasty pharaoh Tefnakht and Plutarch mentions a pillar at Thebes on which was inscribed an imprecation against Menes as the introducer of luxury.[34]

In Pliny's[clarification needed] account, Menes was credited with being the inventor of writing in Egypt.

[T]he date and the mechanism of the creation of hieroglyphs are much harder to determine.

An obvious point for the date would be the beginning of the first dynasty. Here, according to Egyptian tradition, Menes of This in Upper Egypt conquered the Delta, unified the country, founded Memphis as his capital, and introduced many of the traits of classical Pharaonic culture; although, interestingly, he is not credited with the invention of hieroglyphs. A minimalist modern interpretation of what happened at the beginning of Egyptian history would be that there was no Menes, the search for him among the historical records is therefore meaningless, and that there was probably no unification either; all that happened was that the Egyptians invented writing and began to record their history systematically. The date for this can be obtained by a combination of astronomical data and dead reckoning from later king-lists such as the Turin canon: 3089 + x B.C., where x is the length of the obscure 'first intermediate period'. Considerable attempts have been made by historians to reduce this figure, but it is rather supported by some of the most recent Carbon-14 calibrations (see most cautiously Shaw 1984). A date of 3100 would not be far wrong, therefore, in which case there is a suitable time-lag behind the Mesopotamian introduction of writing.

The problem, however, is complicated by the known existence of Egyptian kings before Menes. The Palermo Stone, essentially a fifth-dynasty composition (although almost certainly a much later copy), clearly shows, on a separate fragment, the existence of kings wearing the crown of united Egypt well before 'Menes' and the supposed unification. Names of nine kings of Lower Egypt are also preserved, and outlandish they are, at least by later standards; this may be explicable by their Lower Egyptian origin, or more likely some form of oral tradition has been at work, but the very existence of these names must make us cautious (Sethe 1903). More disturbing are the contemporary monuments of kings, principally from the royal cemetery at Abydos but also from elsewhere, with names such as the increasingly attested Ro or Iry, the obscure Ka or Sekhen, and the better-known Scorpion (reading uncertain), who seems to be almost a prototype of Menes in his achievements (Barta 1982). The embarrassment caused by the existence of these kings is reflected in the term 'Dynasty O' which is frequently applied to them. Names of these kings appear clearly on contemporary monuments such as jars, and even the Scorpion macehead, and this leaves us in no doubt that writing existed in Egypt before the first king of Dynasty I. Our date of 3100 must therefore be raised to 3150 or even slightly earlier, and it is always possible that archaeological discovery will upset this picture even more. 'Menes', therefore, was not the inventor of hieroglyphs.

-- The emergence of writing in Egypt, by John D. Ray

Crocodile episode

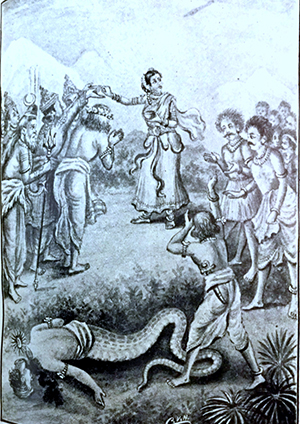

Diodorus Siculus recorded a story of Menes related by the priests of the crocodile god Sobek at Crocodilopolis, in which the pharaoh Menes, attacked by his own dogs while out hunting,[35] fled across Lake Moeris on the back of a crocodile and, in thanks, founded the city of Crocodilopolis.[35][36][37]

Gaston Maspero (1910), while acknowledging the possibility that traditions relating to other kings may have become mixed up with this story, dismisses the suggestions of some commentators[38] that the story should be transferred to the Twelfth Dynasty pharaoh Amenemhat III and sees no reason to doubt that Diodorus did not correctly record a tradition of Menes.[35] Later, Edwards (1974) states that "the legend, which is obviously filled with anachronisms, is patently devoid of historical value".[36]

Death

According to Manetho, Menes reigned for either 30, 60 or 62 years and was killed by a hippopotamus.[10][39]

In popular culture

Alexander Dow (1735/6–79), a Scottish orientalist and playwright, wrote the tragedy Sethona, set in ancient Egypt. The lead part of Menes is described in the dramatis personæ as "next male-heir to the crown" now worn by Seraphis, and was played by Samuel Reddish in a 1774 production by David Garrick at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.[40]

-- Sethona. A Tragedy. As it is Performed at the Theatre-Royal in Drury-Lane, by Alexander Dow

https://archive.org/stream/sethonatrage ... a_djvu.txt

-- History of Hindostan; From the Earliest Account of Time, To the Death of Akbar; Translated From the Persian of Mahummud Casim Ferishta of Delhi: Together With a Dissertation Concerning the Religion and Philosophy of the Brahmins; With an Appendix, Containing the History of the Mogul Empire, From Its Decline in the Reign of Mahummud Shaw, to the Present Times,(1768), by Alexander Dow.

-- History of Hindostan, Translated from the Persian. To Which are Prefixed Two Dissertations; The First Concerning the Hindoos, and the Second on the Origin and Nature of Despotism in India, A New Edition. In Three Volumes, Volume I (1812), by Alexander Dow, Esq.

See also

• First Dynasty of Egypt family tree

• Mannus, ancestral figure in Germanic mythology

• Minos, king of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa

• Manu (Hinduism), Progenitor of humanity

• Nu'u, Hawaiian mythological character who built an ark and escaped a Great Flood

• Nüwa, goddess in Chinese mythology best known for creating mankind

• Min (god)

• Hor-Aha

Notes

1. Originally, the full royal title of a pharaoh was Horus name x nebty name y Golden-Horus name z nesu-bit name a Son-of-Ra name b. For brevity's sake, only one element might be used, but the choice varied between circumstances and period. Starting with Dynasty V, the nesu-bit name was the one regularly used in all official documents. In Dynasty I, the Horus-name was used for a living pharaoh, the nebty-name for the dead.[3]

2. In the upper right hand quarter of the Naqada label is a serekh of Hor-Aha. To its right is a hill-shaped triple enclosure with the “mn” sign surmounted by the signs of the “two ladies”, the goddesses of Upper Egypt (Nekhbet) and Lower Egypt (Wadjet). In later contexts, the presence of the “two ladies” would indicate a “nbty” name (one of the five names of the king). Hence, the inscription was interpreted as showing that the “nbty” name of Hor-Aha was “Mn” short for Menes.[16] An alternative theory is that the enclosure was a funeral shrine and it represents Hor-Aha burying his predecessor, Menes. Hence Menes was Narmer.[17] Although the label generated a lot of debate, it is now generally agreed that the inscription in the shrine is not a king’s name, but is the name of the shrine “The Two Ladies Endure,” and provide no evidence for who Menes was.[18]

3. Other dates typical of the era are found cited in Capart, Jean, Primitive Art in Egypt, pp. 17–18.

References

1. Kitchen, KA (1991). "The Chronology of Ancient Egypt". World Archaeology. 23 (2): 201–8. doi:10.1080/00438243.1991.9980172.

2. Edwards 1971, p. 13.

3. Lloyd 1994, p. 7.

4. Cervelló-Autuori 2003, p. 174.

5. Edwards 1971, p. 11.

6. Loprieno, Antonio (1995). Ancient Egyptian: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge University press. ISBN 0-521-44384-9.

7. Beck et al. 1999.

8. Heagy 2014.

9. Seidlmayer 2010.

10. Manetho, Fr. 6, 7a, 7b. Text and translation in Manetho, translated by W.G. Waddell (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1940), pp.26–35

11. Herodotus: 2.4.1, 2.99.1ff.

12. Lloyd 1994, p. 6.

13. Loprieno 1995, p. 38.

14. Gardiner 1961, p. 405.

15. Naqada Label | The Ancient Egypt Site

16. Borchardt 1897, pp. 1056–1057.

17. Newberry 1929, pp. 47–49.

18. Kinnear 2003, p. 30.

19. Newberry 1929, pp. 49–50.

20. Helck 1953, pp. 356–359.

21. Heagy 2014, pp. 77–78.

22. Herodotus (1958). The Histories of Herodotus of Halicarnassus. Translated by Harry Carter. Haarlem, Netherlands: Joh. Enschedé en Zonen. p. 122. OCLC 270617466.

23. Budge, EA Wallis (1885), The Dwellers on the Nile: Chapters on the Life, Literature, History and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, p. 54, Many dates have been fixed by scholars for the reign of this king: Champollion-Figeac thought about BC 5867, Bunsen 3623, Lepsius 3892, Brugsch 4455, and Wilkinson 2320.

24. Frank Northen Magill; Alison Aves (1998). Dictionary of World Biography. Taylor & Francis. pp. 726–. ISBN 978-1-57958-040-7.

25. Maspero 1903, p. 331.

26. Verbrugghe & Wickersham 2001, p. 131.

27. Shaw & Nicholson 1995, p. 218.

28. Ryholt 2009.

29. Manley 1997, p. 22.

30. Herodotus: 2.99.4.

31. Herodotus: 2.109

32. Verbrugghe & Wickersham 2001, p. 133.

33. P. Tallet, D. Laisnay: Iry-Hor et Narmer au Sud-Sinaï (Ouadi 'Ameyra), un complément à la chronologie des expéditios minière égyptiene, in: BIFAO 112 (2012), 381–395, available online

34. Elder 1849, p. 1040.

35. Maspero 1910, p. 235.

36. Edwards 1974, p. 22.

37. Diodorus: 45

38. Elder 1849, p. 1040, ‘in defiance of chronology’.

39. "Comparing the King Lists of Manetho".

40. Dow 1774.

Bibliography

• Beck, Roger B; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S; Naylor, Phillip C; Shabaka, Dahia Ibo (1999), World history: Patterns of interaction, Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell, ISBN 0-395-87274-X

• Cervelló-Autuori, Josep (2003), "Narmer, Menes and the seals from Abydos", Egyptology at the dawn of the twenty-first century: proceedings of the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists, vol. 2, Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 978-977-424-714-9.

• Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, vol. 1

• Dow, Alexander (1774), Sethona: a tragedy, as it is performed at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, Collection of plays. [1767-1802] ;v. 1, no. 5, London: T. Becket, hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t2z31pr8f

• Edwards, IES (1971), "The early dynastic period in Egypt", The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 1, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

• Elder, Edward (1849), "Menes", in Smith, William (ed.), Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, vol. 2, Boston: Charles C. Little & James Brown.

• Faber, George Stanley (1816), "The origin of pagan idolatry: ascertained from historical testimony and circumstantial evidence", 3, London: F&C Rivingtons, vol. 2.

• Gardiner, Alan (1961), Egypt of the Pharaohs, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

• of Halicarnassus, Herodotus, The Histories.

• Heagy, Thomas C. (2014), "Who was Menes?", Archeo-Nil, 24: 59–92. Available online "[1]"..

• Lloyd, Alan B. (1994) [1975], Herodotus: Book II, Leiden: EJ Brill, ISBN 90-04-04179-6.

• Maspero, Gaston (1903), Sayce, Archibald Henry (ed.), History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria, vol. 9, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 9780766135017.

• ——— (1910) [1894], Sayce, Archibald Henry (ed.), The dawn of civilization: Egypt and Chaldæa, translated by McClure, M L, London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, ISBN 978-0-7661-7774-1.

• Manley, Bill (1997), The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Egypt, London: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-051331-0.

• Rachewiltz, Boris de (1969), "Pagan and magic elements in Ezra Pound's works", in Hesse, Eva (ed.), New approaches to Ezra Pound, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

• Ryholt, Kim (2009), "Egyptian historical literature from the Greco-Roman period", in Fitzenreiter, Martin (ed.), Das Ereignis, Geschichtsschreibung zwischen Vorfall und Befund, London: Golden House.

• Schulz, Regine; Seidel, Matthias (2004), Egypt: The World of the Pharaohs, HF Ullmann, ISBN 978-3-8331-6000-4.

• Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul (1995), The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, Harry N Abrams, ISBN 0-8109-9096-2.

• Seidlmayer, Stephan (2010) [2004], "The Rise of the State to the Second Dynasty", Egypt: The World of the Pharaohs, ISBN 978-3-8331-6000-4.

• Verbrugghe, Gerald Paul; Wickersham, John Moore (2001) [1996], Berossos and Manetho, introduced and translated: Native Traditions in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-08687-0.

• Waddell, Laurence A (1930), Egyptian civilization: Its Sumerian origin, London, ISBN 978-0-7661-4273-2.

External links

• Menes, Ancient Egypt.

• "The Contendings of Horus and Seth", Egypt, IL: Reshafim, archived from the original on 2010-09-24, retrieved 2007-07-22.

• "Menes", Ancient Egyptian Civilization (image), Aldokkan.

• "Menes" . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

**************

Menes, king of Egypt [Alternate titles: Aha, Mena, Meni, Min, Narmer, Scorpion

by Britannica

Accessed: 3/2/23

Alternate titles: Aha, Mena, Meni, Min, Narmer, Scorpion

Flourished: c.2930 BCE - c.2900 BCE

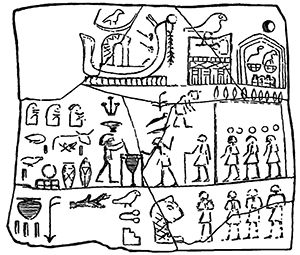

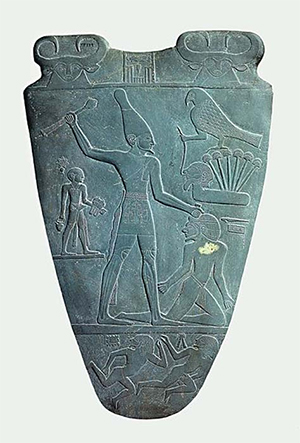

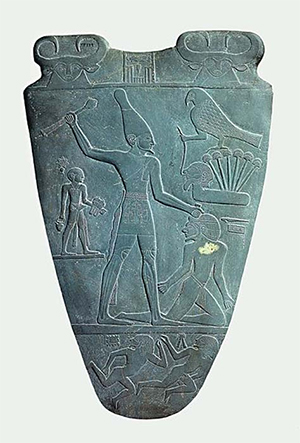

Figure perhaps representing Menes on a victory tablet of Egyptian King Narmer, c. 2925–c. 2775 BCE. Courtesy of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo; photograph, Hirmer Fotoarchiv, Munich

Menes, also spelled Mena, Meni, or Min, (flourished c. 2925 BCE), legendary first king of unified Egypt, who, according to tradition, joined Upper and Lower Egypt in a single centralized monarchy and established ancient Egypt’s 1st dynasty. Manetho, a 3rd-century-BCE Egyptian historian, called him Menes, the 5th-century-BCE Greek historian Herodotus referred to him as Min, and two native-king lists of the 19th dynasty (13th century BCE) call him Meni. Modern scholars have inconclusively identified the legendary Menes with one or more of the archaic Egyptian kings bearing the names Scorpion, Narmer, and Aha.

In addition to crediting Menes with the unification of Egypt by war and administrative measures, a tradition appearing in the Turin Papyrus and the History of Herodotus credits him with diverting the course of the Nile in Lower Egypt and founding Memphis—the capital of ancient Egypt during the Old Kingdom—on the reclaimed land. Excavations at Ṣaqqārah, the cemetery for Memphis, revealed that the earliest royal tomb located there belongs to the reign of Aha. Manetho called Menes a Thinite—i.e., a native of the nome (province) of Thinis in Upper Egypt—and, in fact, monuments belonging to the kings Narmer and Aha, either of whom may be Menes, have been excavated at Abydos, a royal cemetery in the Thinite nome. Narmer also appears on a slate palette (a decorated stone on which cosmetics were pulverized) alternately wearing the red and white crowns of Lower and Upper Egypt (see crowns of Egypt), a combination symbolic of unification, and shown triumphant over his enemies. Actually, the whole process probably required several reigns, and the traditional Menes may well represent the kings involved. According to Manetho, Menes reigned for 62 years and was killed by a hippopotamus.

**************************************

Menes: Legends Say He United Egypt Under its First Dynasty … But Did He Even Exist?

by Alicia McDermott

Ancient Greece (ancient-origins.net)

December 21, 2018

Much like the ancient Romans had Romulus and Remus to thank for the foundation of their civilization, so too did the ancient Egyptians have a legendary figure that united the Upper and Lower lands – King Menes. And like the Roman brothers, there is much mythology tied into Menes’ story. Controversy also surrounds the king, with scholars questioning if Menes was his real name, or if he even existed.

He Who Endures

Menes appears in several ancient texts. He is the first human king after the divine and demi-god rulers in the Turin Canon and has the first cartouche in the Abydos King List of Seti I. The Ramesseum Min reliefs also name Menes as the first king of Egypt. It’s worth noting that Menes is, however, absent on a seal listing the first six rulers of the First Dynasty that was found at Umm el-Qaab. In fact, nothing that has been found from the time Menes would have lived names him as a king. One explanation is that kings in the Early Dynastic period were identified by a Horus name, not a private name.

The cartouche of Menes on the Abydos King List. (Olaf Tausch/ CC BY 3.0 )

And Menes was a man of many names; Manetho's Chronology from the 3rd century BC names him as Menes, but two Egyptian 19th dynasty king lists write his name as Meni. The Greek historian Herodotus called him Min and he was Manas to another Greek historian - Diodorus Siculus. Jewish historian Josephus gives him yet another name – Minaios.

Many modern scholars suggest that the name Menes, which means “He Who Endures”, may actually be a reference to Menes being a figure that encompassed all the kings that worked to unify Egypt. But not everyone agrees.

Limestone head of a man thought to be the 1st Dynastic King of Egypt, Menes or Narmer. Egyptologist Flinders Petrie believed it was the latter. (Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg)/CC BY SA 4.0)

Who was King Menes?

There is little that can be said of Menes’ life for certain, however it is generally agreed that if he existed, he was born in either Hierakonpolis (Nekhen) or Thinis and he ruled sometime between about 3000 BC to 3100 BC. Ancient sources also tend to agree that he ruled for more than 60 years.

An ancient Nekhen tomb painting in plaster with barques, staffs, goddesses, and animals - possibly the earliest example. (Francesco Raffaele/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

Apart from those aspects of his life, there are many stories that seem to mix fact with myth. Combine that with a lack of archaeological evidence and it is near impossible to ascertain more details of Menes’ life. This had led some to question if he even was a real historical figure, or if King Menes solely acted as a legendary founding father and hero for ancient Egyptians.

I another theory, as others suggest, Menes was the personification of the Naqada III rulers Ka, Scorpion II and Narmer. Narmer in particular has been singled out as the pharaoh who inspired the story of Menes, or who really was Menes. Aha, possibly Narmer’s son and the second dynastic king, has also been proposed as the true identity of Menes due to the appearance of ‘Mn’ (signifying ‘Menes’) in some ancient Egyptian sources beside the names of both men.

The ivory label mentioning Hor-Aha along with the mn sign. (Public Domain)

Reconstruction of the Narmer-Menes Seal impression from Abydos. (Heagy1/ CC BY SA 4.0)

The well-known Egyptologist Flinders Petrie believed that ‘Menes’ was actually a title, not a personal name, and said Narmer was the first real Egyptian pharaoh. It is true that some of the stories line up. For example, Narmer is also credited with having completed the process of unifying Upper and Lower Egypt. (Although some ancient sources have also credited Aha with this.)

Pharaoh Menes Unifies Egypt

The biggest accomplishment that has been credited to Menes is the unification of Egypt. It has been said that King Menes used both political strategy and force to do so. A possible marriage with a member of the southern royal family has been named as one of the ways he unified Upper and Lower Egypt. And once the lands were joined, policies were put in action to maintain peace and bring order to his realm.

While it sounds great for one king to have managed such an incredible feat, most historians agree that there were probably several rulers who worked over time to eventually reach that goal. Yet the naming of one central figure as having completed the arduous task would have been important to the ancient Egyptians. In this light, Menes acts as a beginning in history for the ancient Egyptians.

The smiting side of the Narmer Palette. ( Public Domain ) Scholars have interpreted this as a representation of the pharaoh conquering Lower Egypt.

Menes’ Other Achievements

Menes has been credited with many other accomplishments in the ancient Egyptian culture, including the introduction of sacrifice and worshipping the gods. It has been said that a ‘Golden Age’ set in after Egypt was unified and that positive period has also been attributed to Menes. For example, Pliny claims Menes introduced papyrus and written script to the ancient Egyptians. And Diodorus Siculus wrote that he was the first Egyptian law-giver. Manetho wrote of Menes as a strong warrior that expanded his kingdom’s borders and then provided a sense of order.

In the Turin Papyrus and also Herodotus’ ‘ History’, Menes is said to have had a dam constructed in the Nile to divert the flow over the land where Memphis lies. He is credited with founding the city and making it luxurious. But a 2012 discovery of a relief describing the visit of a pre-dynastic ruler to Memphis in the early 32nd century BC means that this story is nothing more than a tall tale.

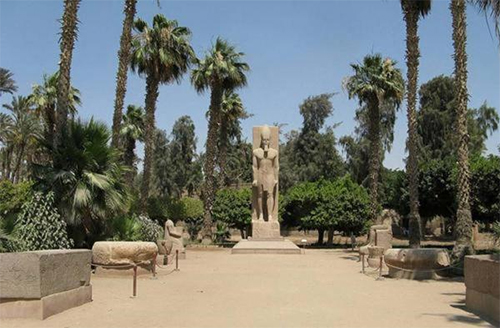

Monuments from the ancient city of Memphis. (Gabriel Indurskis/ CC BY NC 2.0)

Regardless, Memphis as a capital for Egypt was a good choice. The land around it was fertile and its location was strategic. In that city, Menes allegedly taught the residents to live elegant, luxurious lives – ones that included less work and more time for hobbies, and even beautiful cloths covering couches and tables. For many of Menes’ people, life was good, food was plenty, and peace was prevalent.

A Crocodile and a Hippopotamus – The End of a Legend

No article on Menes would be complete without mention of two tales involving the king and iconic ancient Egyptian animals.

In the first, Menes is given credit for founding the city of Crocodilopolis. All because he rode a crocodile to safety when his hunting dogs turned on him. The king decided a city was a suitable way to honor the animal for saving his life.

Crocodiles of various ages mummified in honor of the crocodile god Sobek. The Crocodile Museum, Aswan. (JMCC1/ CC BY SA 3.0)

But it is another well-known Egyptian animal that ended that life. Manetho and others write that Menes was either killed or carried off by a hippopotamus. This was considered one of the worst ways to die in ancient Egypt. His tomb lies in Saqqara – Memphis’ necropolis.

View of Saqqara necropolis, including Djoser's step pyramid (center), the Pyramid of Unas (left) and the Pyramid of Userkaf (right). (Hajor/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

Following the tragic event, Djer, Menes’ son, ascended the throne as an infant and his widowed wife, Queen Neithotepe, acted as regent until the child came of age.

_______________

References

Boddy-Evans, A. (2018) ‘The Story of Menes, the First Pharaoh of Egypt.’ ThoughtCo. Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/who-was-the-f ... gypt-43717

Gill, N.S. (2017) ‘Menes-First King of Egypt.’ ThoughtCo. Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/menes-first-k ... ypt-119800

Heagy, T. ( 2014) ‘Who Was Menes?’ Archéo-Nil 24, pp. 59-92. Available at: https://www.narmer.org/menes

KingtutOne.com (n.d.) ‘Menes the 1st Pharaoh.’ KingtutOne.com. Available at: http://kingtutone.com/pharaohs/menes/

Kinnaer, J. (2014) ‘Menes.’ The Ancient Egyptian Site. Available at: http://www.ancient-egypt.org/who-is-who/m/menes.html

New World Encyclopedia. (2014) ‘Menes.’ New World Encyclopedia. Available at: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Menes

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2018) ‘Menes: King of Egypt.’ Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Menes