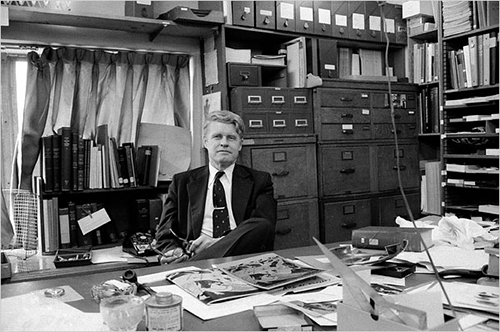

Jiri Frel [Jiri Frohlich]

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 10/17/22

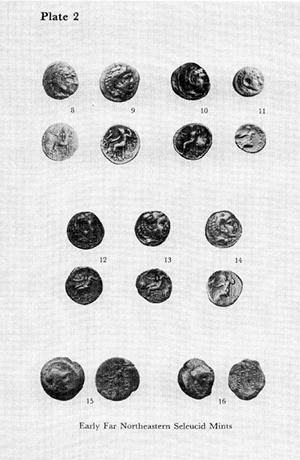

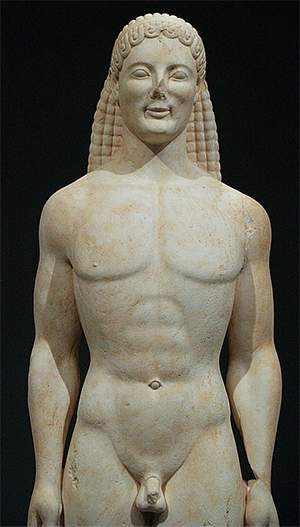

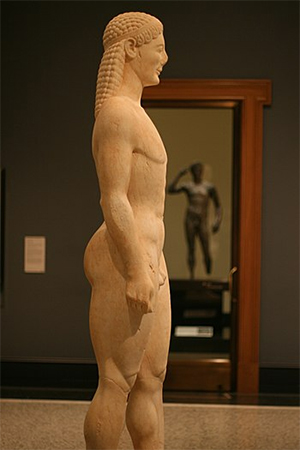

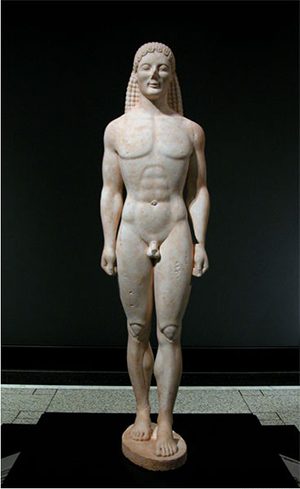

The Getty kouros is an over-life-sized statue in the form of a late archaic Greek kouros. The dolomitic marble sculpture was bought by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, in 1985 for ten million dollars and first exhibited there in October 1986....

The kouros first appeared on the art market in 1983 when the Basel dealer Gianfranco Becchina offered the work to the Getty's curator of antiquities, Jiří Frel. Frel deposited the sculpture (then in seven pieces) at Pacific Palisades along with a number of documents purporting to attest to the statue's authenticity. These documents traced the provenance of the piece to a collection in Geneva of Dr. Jean Lauffenberger who, it was claimed, had bought it in 1930 from a Greek dealer. No find site or archaeological data was recorded. Amongst the papers was a suspect 1952 letter allegedly from Ernst Langlotz, then the preeminent scholar of Greek sculpture, remarking on the similarity of the kouros to the Anavyssos youth in Athens (NAMA 3851). Later inquiries by the Getty revealed that the postcode on the Langlotz letter did not exist until 1972, and that a bank account mentioned in a 1955 letter to an A.E. Bigenwald regarding repairs on the statue was not opened until 1963.

The documentary history of the sculpture was evidently an elaborate fake and therefore there are no reliable facts about its recent history before 1983. At the time of acquisition, the Getty Villa's board of trustees split over the authenticity of the work. Federico Zeri, founding member of board of trustees and appointed by Getty himself, left the board in 1984 after his argument that the Getty kouros was a forgery and should not be bought was rejected.

-- Getty kouros, by Wikipedia

Was Jiri Frel a Spy?

Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino undertook a Freedom of Information Act request for the FBI’s file on former Getty Curator Jiri Frel, and posted the FBI file. The FBI was very interested in Frel, sparking rumors over whether Arthur Houghton was tasked with keeping “an eye on” Frel.

Espionage allegations aside, the Frel file is a fascinating study of a complicated personality. It hints at Frel’s famously chaotic love life. More importantly, it demonstrates how adept the charismatic polymath, connoisseur and political shape-shifter was at manipulating situations and spinning answers for his own survival. Colleagues at the Getty knew Frel as an Old World snob who constantly complained about America, its broken education system, its obsession with pop culture, its hot dogs and unpalatable mustard. Indeed, years later, when he was caught conducting a massive tax fraud scheme and falsifying provenance for million-dollar fakes at the Getty, Frel left America and never looked back. Yet during his 1971 FBI interview, the reporting agent noted how Frel gushed that “he considers the United States to be in his words ‘a great and good country.

-- Was Jiri Frel a Spy?, by Illicit Cultural Property, illicitculturalproperty.com

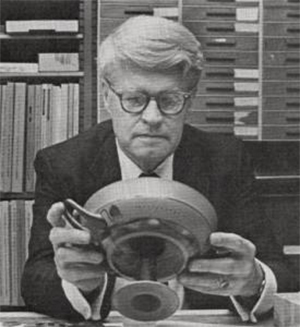

Jiří Frel (often spelled as Jiri Frel, 1923, Dolní Újezd, Czechoslovakia — 29 April 2006, Paris[1][2]) was a Czech and American archaeologist. Between 1973 and 1986 he served as a curator for the J. Paul Getty Museum. He is credited with the expansion of the collection of antiquities of the museum, but he was also involved in a number of controversies, including a tax manipulation scheme to buy artifacts of dubious provenance and purchase of a number of artifacts widely considered to be fake.[3]

Frel was born in Moravia [Moravia is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.] and studied in Paris. He returned to Czechoslovakia after World War II and obtained a doctorate from Charles University in Prague. Subsequently, he was employed by the Greek and Roman art department of Charles University and taught there. In 1969, following the Soviet invasion, Frel emigrated to the United States. For a short period, he taught at Princeton University,

5/24/71

[DELETE] advised there were no records at her institution concerning FREL. His location or activities in the New York City area are unknown to [DELETE]

Inquiry at Princeton University showed he was not employed there.

-- FBI Freedom of Information Act Request on JIRI FREL

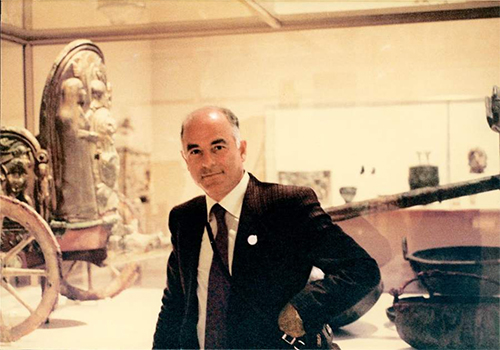

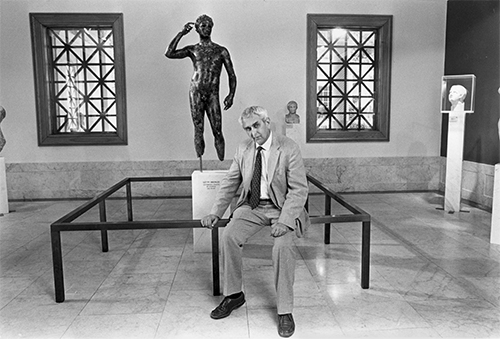

... subsequently worked as an associate curator of Greek and Roman art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in 1973, he became the curator of the department of antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum.[3]

During his tenure as curator, Frel considerably expanded the collection of Greek and Roman artifacts, transforming it to one of the leading museums of the world. He also recruited collectors to donate their items to the museum, apparently frustrated by the refusal of the management to buy new items which were not high-profile. To facilitate this, Frel designed a tax evasion scheme in which fictitious donors paid to an intermediary to get tax reductions for donations of artifact they have never seen.The scam was uncovered by Thomas Hoving, and Frel had to resign in 1984.

[Geraldine Norman] The number of Japanese tourists who come to worship at the van Gogh shrine in Auvers, got a big boost when Yasuda bought the sunflowers in 1987. It will be a terrible disappointment to the nation if they discover their famous sunflower picture is not really by Van Gogh.

[To Tom Hoving, Ex-Director Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC] What do you think Yasuda is going to say if they actually have to face the fact that they are landed with a fake?

[Tom Hoving, Ex-Director Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC] Oh, I don't think they'll face it. I think they hope it'll go away. I do not think that the people in charge of the insurance company are going to let regiments of experts in to take it off the exhibition, and look at it, and maybe even do some analysis, and so on. I just don't think they're gonna do that. I think it would be a very great loss of face. I think the picture was purchased because the only other Vincent van Gogh in Japan prior to the United States firebombing of Tokyo, was a sunflowers, which was destroyed.

[Geraldine Norman] It is said that the painting was relined after its arrival in Japan, which may mean that important evidence has been lost. We asked Yasuda if we could talk to them about this, and our views on the sunflowers problem. Yasuo Goto, the chairman of the company, replied, "We have no intention of participating in any discussion of sunflowers' authenticity, as we hold no doubts whatsoever that it is genuine. We also have no intention of answering the questions mentioned in your letter." I personally find it impossible to believe that the Yasuda sunflowers is by Van Gogh. There's too much evidence against it. It's not mentioned in the letters, or other early documents. It first appears in the hands of Emile Schuffenecker, whose name has long been linked with faking. And it is generally agreed that it is visually inferior to the other two. It does disturb me, however, that so many experts still think it genuine. They aren't talking to each other, and don't know each other's arguments. Which is why the muddle persists. If the experts, the Van Gogh Foundation, and Mr. Goto from Yasuda, could be persuaded to divulge what they know, the truth about the Yasuda picture could be found. Using secrecy to protect their reputations and huge investments just won't do. Christie's has both money and reputation at stake, and has opted for silence. They refused to be interviewed, and issued a statement saying, "We see no reason, on the evidence so far produced, to alter our original opinion that the sunflowers is an authentic work by Van Gogh."

[Tom Hoving, Ex-Director Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC] You don't ever get a concert of opinion in art. Very seldomly you get it. And so this, I think, will just kind of go on forever. And since it's not going to ever be for resale, does it matter?

[Dr. Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, Prof. History of Art, University of Toronto] Most of us who know Van Gogh -- and I think a lot of us do, or profess to know a lot about Van Gogh -- know that this very simple man, filled with great humility and compassion for mankind, saw these works as different legacies than financial ones. I think he would be horrified, and distraught beyond anything you can imagine, to see himself somersaulted to such tremendous value, and such crass commercialism. I think it would have been something that he couldn't have ever tolerated.

[url]-- Is Van Gogh's 'Sunflowers' A Fake?: The Fake Van Gogh's, Narrated by Geraldine Norman, World History Documentaries[/url]

Before leaving the Getty Museum in 1986 he hired Marion True, the new curator, who was later charged with laundering stolen artifacts.[3]

References

1. Kennedy, Randy (17 May 2006). "Jiri Frel, Getty's Former Antiquities Curator, Dies at 82". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

2. Bouzek, Jan (2006). "Jiří Frel" (PDF). Classical Tradition and Czech Culture. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

3. Frammolino, Ralph (13 May 2006). "Jiri Frel, 82; Colorful Curator Who Left Getty Under a Cloud". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

*****************************

Jiri Frel: Scholar, Refugee, Curator…Spy?

by Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino

Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities in the World's Museums

September 12, 2011

[The Authors

This blog is written and maintained by Jason Felch. The book Chasing Aphrodite was written by Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino.

Jason Felch

Ralph Frammolino

Jason is an award-winning author and investigative reporter who has spent a decade researching the illicit antiquities trade. He has also written on topics such as arms trafficking, forensic DNA, disaster fraud, money laundering, and public education.

In 2006, Felch and Frammolino were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting for exposing the role of the J. Paul Getty Museum and other American museums in the black market for looted antiquities. Their book on the topic, Chasing Aphrodite, was a Los Angeles Times best-seller and has been awarded the California Book Award, the SAFE Beacon Award and the ARCA Award for Art Crime Scholarship.

SPEAKING

Jason is available for speaking engagements on topics including museum ethics; the illicit antiquities trade; art crime and international law enforcement; the ethics and law of collecting; the history of the J. Paul Getty Museum; crisis management; and investigative journalism.

The museum scandals described in the book have local relevance for cities including Los Angeles, New York, Boston, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Toledo, Princeton, Dallas/Ft. Worth, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Denver, New Haven, and Washington DC.

CONTACT

Please send inquiries to: chasingaphrodite@gmail.com]

In the early 1980s, the antiquities department at the J. Paul Getty Museum was a hotbed of whispered political intrigue.

Rumors swirled that the department’s Czech curator, Jiri Frel, was a Communist spy. And many believed the deputy curator, former State Department official Arthur Houghton, was a CIA plant tasked with keeping an eye on Frel’s activities.

Frel’s once-classified FBI file, obtained by the authors under the Freedom of Information Act, reveals that the US Government asked similar questions about Frel in 1971, when an investigation was conducted into his “possible intelligence connections.”

As part of our Hot Documents series, we’ve posted the entire FBI file here.

Frel was born in Czechoslovakia 1923 as Jiri Frohlich to a Czech father and Austrian mother, the FBI records show. (The family changed the surname to Frel in 1940s, possibly to hide Jewish roots.) Frel entered the United States in 1969 as a visiting scholar at Princeton University’s Institute for Advanced Studies. The Institute had long been an intellectual home base for leading scholars, including Albert Einstein.

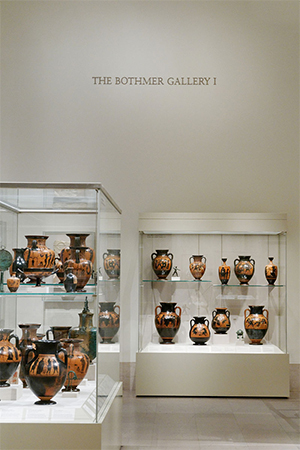

After a year at the Institute, Frel was granted political asylum with the help of lawyers at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he had begun working as an research associate in the Greek and Roman Department under Dietrich von Bothmer. Interestingly, Frel cites additional assistance from George Kennan, the former US Ambassador to the Soviet Union and a leading historian at the IAS.

Unknown to the public, Gene Sharp formulated a theory on non violence as a political weapon. Also he first helped NATO and then CIA train the leaders of the soft coups of the last 15 years. Since the 50s, Gene Sharp studied Henry D. Thoreau and Mohandas K. Gandhi’s theory of civil disobedience. For these authors, obedience and disobedience were religious and moral matters, not political ones. However, to preach had political consequences; what could be considered an aim could be perceived as a mean. Civil disobedience can be considered then as a political, even military, action technique.

In 1983, Sharp designed the Non Violent Sanctions Program in the Center for International Affairs of Harvard University where he did some social sciences studies on the possible use of civil disobedience by Western Europe population in case of a military invasion carried out by the troops of the Warsaw Pact. At the same time, he founded in Boston the Albert Einstein Institution with the double purpose of financing his own researches and applying his own models to specific situations. In 1985, he published a book titled "Making Europe Unconquerable " whose second edition included a preface by George Kennan, the Father of the Cold War. In 1987, the association was funded by the U.S. Institute for Peace and hosted seminars to instruct its allies on defense based on civil disobedience. General Fricaud-Chagnaud, on his part, introduced his "civil deterrence" concept at the Foundation of National Defense Studies.

General Edward B Atkeson, seconded by the US Army to the Director of the CIA, integrates the institute into the apparatus of the US stay-behind network interfering in the affairs of allied states. Focusing on the morality of the means of action avoids debate on the legitimacy of the action. Non-violence, accepted as good in itself and an integral part of democracy, facilitates whitewashing of covert actions which are intrinsically non-democratic.

-- The Albert Einstein Institution: non-violence according to the CIA, by Thierry Meyssan, Voltaire Network

During an interview with FBI agents in September 1971, Frel was “extremely cooperative,” the records show. Frel denied ever being a spy but he admitted to providing Communist government officials with the names, background information and psychological assessments of those he met on his scholarly travels throughout Europe during the Cold War. “He stated that while he was never aware of this information being used for intelligence purposes, he often suspected that the Chechoslovak [sic] Intelligence Service reviewed copies of this form,” the report notes.

The FBI seemed particularly interested in Frel’s ties to his mentor at Charles University, a woman whose name is redacted in the FBI file. We shared the FBI file with an expert on academic life under Communist Prague, UC Berkeley Associate Professor John Connelly, who was able to identify the woman as Ruzena Vackova, a professor of classical architecture in Prague who was condemned to 22 yrs. prison in 1952.

According to Connelly, Vackova was one of the few in academia to speak openly against the Communist regime and was the only professor in Prague to march with student protesters. In Connelly’s book “Captive University,” he describes Vackova telling a group in March 1948, “…if a criteria for dismissing these students was participation in these demonstrations, then I would like to share their fate.” (p.194) Vackova spent 16 years in prison and her dissent continued after her release, Connelly told us in an email.

“She was an extraordinary, outstanding person,” he said.

The FBI had picked up on whispers that Frel may have been a Communist agent who turned Vackova in to the authorities. “Since he was one of her protégés at Charles University in Prague, a rumor began to spread of which he was aware, that he had somehow cooperated with the Communist government in her demise,” the report notes.

Frel denied the claim and railed against the Soviet overlords in his Czech homeland, saying he “vehemently disagrees with the Communist regime.” Yet the curator also volunteered (we imagine somewhat sheepishly, but the bland FBI prose doesn’t say) how he cultivated the regime’s approval by once applying for the Communist party. Frel said he applied “to keep his position at the university,” and was rejected because of his incompatible political views.

Connelly believes that it is unlikely that Frel had any role in Vackova’s arrest. “He was probably a conformist (like the overwhelming majority) who tried to anticipate the will of the regime,” Connelly wrote to us. Few who knew him at the Getty would think of Frel as a conformist, but during his years there he certainly showed a flare for telling those in power what they wanted to hear while doing what he damn well pleased.

Espionage allegations aside, the Frel file is a fascinating study of a complicated personality. It hints at Frel’s famously chaotic love life. More importantly, it demonstrates how adept the charismatic polymath, connoisseur and political shape-shifter was at manipulating situations and spinning answers for his own survival. Colleagues at the Getty knew Frel as an Old World snob who constantly complained about America, its broken education system, its obsession with pop culture, its hot dogs and unpalatable mustard. Indeed, years later, when he was caught conducting a massive tax fraud scheme and falsifying provenance for million-dollar fakes at the Getty, Frel left America and never looked back. Yet during his 1971 FBI interview, the reporting agent noted how Frel gushed that “he considers the United States to be in his words ‘a great and good country.”

The story told by the documents is not complete: 10 pages were redacted, citing exemptions for national security and privacy. But it’s clear the FBI closed its case in 1971, concluding Frel had no ties to foreign intelligence services. Frel died in Paris on April 29, 2006.

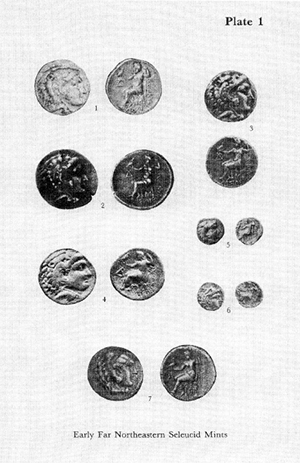

As for Houghton and his ties to the CIA, the rumors were not far off. Before coming to the Getty in 1982, he had spent a decade working for the State Department, including time in its bureau of intelligence and research as a Mid East analyst. Houghton was fond of cultivating his image as a man of mystery. In truth, he had burned out on the diplomatic bureaucracy and chose a career that brought him closer to his long time passion — ancient coins. Houghton remains active in the field to this day.