by Wikipedia

Accessed: 10/17/20

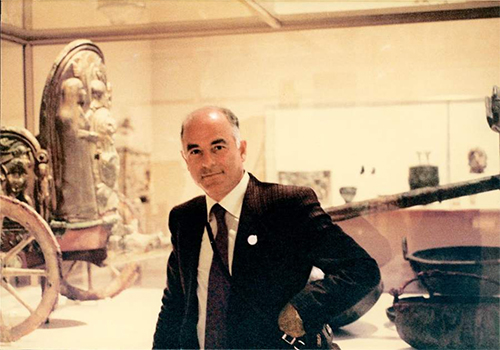

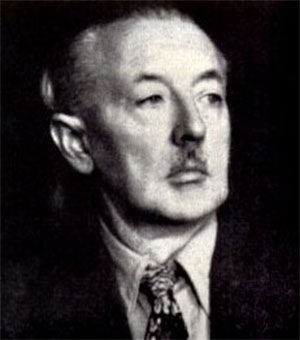

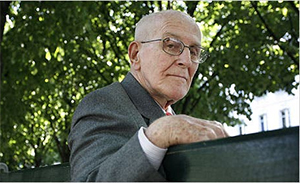

Robert Emmanuel Hecht, Jr. (3 June 1919 – 8 February 2012) was an American antiquities art dealer based in Paris.

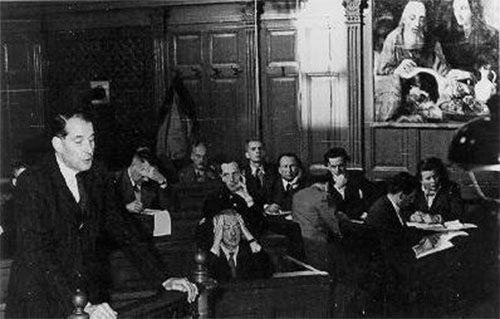

He was on trial in Italy from 2005 to just before his death in 2012, on charges of conspiring to traffic in looted antiquities artifacts.

Personal life

Robert Hecht was born in Baltimore, Maryland. He was a descendant of the family that founded The Hecht Company, a chain of department stores based in Baltimore, where he grew up.

He graduated from Haverford College in 1941, having majored in Latin, was a naval officer during World War II, and after it spent a stint as interpreter at the War Crimes Investigation in Nuremberg and one year at the University of Zurich studying archaeology and classical philology before winning a Rome Prize Fellowship for the American Academy in Rome (1947–49).

In 1953 he married Elizabeth Chase, a graduate student of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Robert Hecht had three daughters: Daphne Howat by his first marriage to Anita Liebman; and Andrea and Donatella Hecht by his marriage to Ms. Chase. He lived for many years in Paris and died at home there.[1]

Career

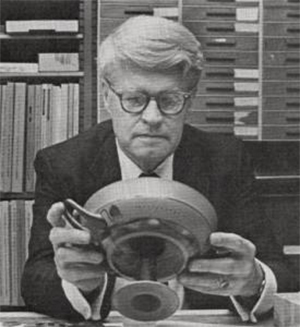

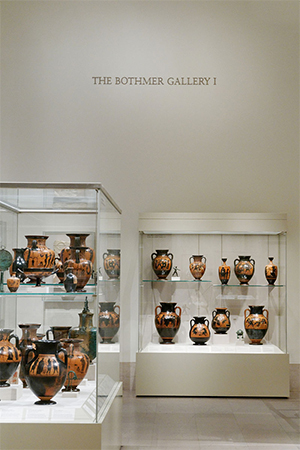

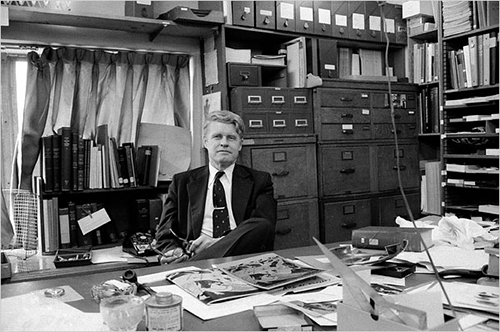

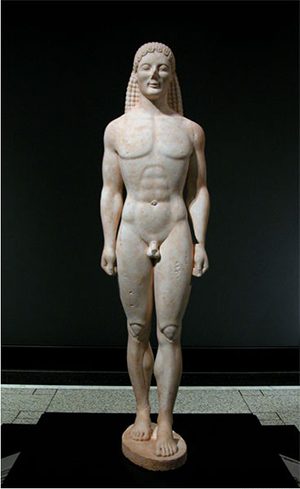

Hecht made his first significant sales in the 1950s, including the dispersal of the collection of Ludwig Curtius, former director of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome, and later the sale of a late 6th century BCE red figure vase to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the 1960s and 1970s he reached a pre-eminent position in the trade. Known throughout the museum world for his scholarship and his 'eye' for antiquities,[citation needed] he sold to all the world's major museums including the British Museum, the Louvre, the Metropolitan, the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and to many private collectors all over the world. Other dealers tended to give him first refusal on their 'finds'.[citation needed]

It was a period when major museums and serious collectors in Europe, the U.S., and Japan did not feel it their responsibility to enforce the export laws of southern European countries.[citation needed] Hecht always worked on the assumption that it was the preservation and study of ancient art that really mattered, not provenance.[citation needed] In the 1970s Bruce McNall was his "secret United States partner."[2]

Provenance issues

The Euphronios Krater, or "Sarpedon krater"

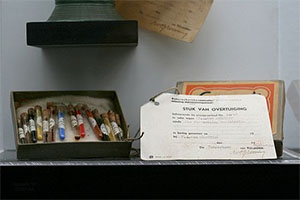

The sale of a Euphronios Krater to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for $1 million in 1972 catapulted Hecht into instant fame and international problems. The Italian authorities claimed that the vase was excavated illegally in Cerveteri, north of Rome. An American Grand Jury, investigating the Euphronios Krater at the request of the Italian authorities — whose evidence came from a tomb robber — found the provenance unproven. In 2000, the Italian authorities found Hecht’s handwritten memoir in his house in Paris and those were used as evidence against him at his Italian criminal trial. In 2006, continuing pressure from Italy led Philippe de Montebello, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, to negotiate a deal that gave the Italian Republic ownership of the vase.

Hecht had wrangles with both the Italian and Turkish authorities but was acquitted in the only lawsuit to reach Italy's Supreme Court of Cassation (Suprema Corte di Cassazione).

After his death in 2012, a stolen Roman stone coffin (Sarcofago delle Quadriglie) returned from his private collection in London to the town of Aquino, Italy.[3] The coffin was stolen from the “Madonna della Libera” church in Aquino in September 1991. After 21 years of investigations, the artifact came back to the collection of the municipal museum of Aquino.

J. Paul Getty Museum controversy

In 2005 Hecht was indicted by the Italian government, together with Marion True, the former curator of antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, for conspiracy to traffic in illegal antiquities. The primary evidence in the case came from the 1995 raid of a Geneva, Switzerland warehouse which had contained a fortune in stolen artifacts.

Italian art dealer Giacomo Medici was eventually arrested in 1997; his operation was thought to be "one of the largest and most sophisticated antiquities networks in the world, responsible for illegally digging up and spiriting away thousands of top-drawer pieces and passing them on to the most elite end of the international art market".[4] Medici was sentenced in 2004 by a Rome court to ten years in prison and a fine of 10 million euros, "the largest penalty ever meted out for antiquities crime in Italy".[4]

The court hearings of the case against Hecht and True ended in 2012 and 2010, respectively, as the statute of limitations, under Italian law, for their alleged crimes had expired.[5]

See also

• Illicit antiquities trade

• Looted art

• Art and cultural repatriation

References

1. Weber, Bruce. "Robert Hecht, Antiquities Dealer, Dies at 92." The New York Times. 19 February 2012.

2. Hoving, Thomas, Making the Mummies Dance, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-73854-2

3. FABIO TONACCI, FRANCESCO VIVIANO. "[https://www.repubblica.it/speciali/arte/2012/07/19/news/sarcofago_quadrighe_aquino-39309683/Torna a casa il Sarcofago delle Quadrighe fu rubato ad Aquino nel 1991: vale milioni]." La Repubblica. 19 July 2012

4. Men's Vogue, Nov/Dec 2006, Vol. 2, No. 3, pg. 46.

5. Povoledo, Elisabetta. "Italian Trial of American Antiquities Dealer Comes to an End." The New York Times. 18 January 2012.

Bibliography

• Questions for Philippe de Montebello Stolen Art? Interview by Deborah Solomon. The New York Times Feb. 19, 2006

• The New York Times June 21, 2006. Antiquities Dealer on Trial in Getty Case Is Vexed but Unbowed. By Elisabetta Povoledo

• The New York Times January 14, 2006. Defendant in Antiquities Case Speaks Up, Angrily. By Elisabetta Povoledo

• Peter Watson and Cecilia Todeschini, 2006. The Medici Conspiracy: The Illicit Journey of Looted Antiquities: From Italy's Tomb Raiders to the World's Greatest Museums (New York:Public Affairs, 2006)

• The New York Review of Books Volume 53, Number 9 • May 25, 2006. Review Notes from Underground by Hugh Eakin

• The New York Times April 5, 2006. A Clash Over Antiquities by John Henry Merryman

• The New York Times February 28, 2006. Met Chief, Unbowed, Defends Museum's Role. By Randy Kennedy and Hugh Eakin

• The New York Review of Books Volume 53, Number 12 • July 13, 2006 by Cecilia Todeschini, Peter Watson, Reply by Hugh Eakin In response to Notes from Underground (May 25, 2006)

• Eleanor Robson, Luke Treadwell and Chris Gosden (eds), 2006. "Who Owns Objects:The Ethics and Politics of Collecting Cultural Artefacts" (Oxford:Oxbow Books)

• Thomas Hoving, 1993. Making the Mummies Dance (New York: Simon and Schuster)

• John L. Hess, 1974. The Grand Acquisitors (New York: Houghton Mifflin) Two chapters are devoted to the Metropolitan Museum's cautious acquisition of the Euphronios krater.