by Wikipedia

Accessed 8/6/2022

Fourmont's Dirty Little Secret

When Joseph DE GUIGNES (1721-1800) at the young age of fifteen was placed with Etienne FOURMONT (1683-1745), Fourmont enjoyed a great reputation as one of Europe's foremost specialists of classical as well as oriental languages. As an associate of Abbe Bignon (the man so eager to stock the Royal Library with Oriental texts), Fourmont had met a Chinese scholar called Arcadius HOANG (1679-1716) and had for a short while studied Chinese with him (Elisseeff 1985:133ff.; Abel-Remusat 1829:1.260). In 1715 the thirty-two-year-old Fourmont was elected to the chair of Arabic at the College Royal. Hoang's death in 1716 did not diminish Fourmont's desire to learn Chinese, and in 1719 he followed Nicolas FRERET (1688-1749) in introducing Europe to the 214 Chinese radicals. This is one of the systems used by the Chinese to classify Chinese characters and to make finding them, be it in a dictionary or a printer's shop, easier and quicker.

Thanks to royal funding for his projected grammar and dictionaries, Fourmont had produced more than 100,000 Chinese character types. But in Fourmont's eyes the 214 radicals were far more than just a classification method. Naming them "clefs" (keys), he was convinced that they were meaningful building blocks that the ancient Chinese had used in constructing characters. For example, Fourmont thought that the first radical (-) is "the key of unity, or priority, and perfection" and that the second radical (׀) signifies "growth" (Klaproth 1828:234). Starting with the 214 basic "keys," so Fourmont imagined, the ancient Chinese had combined them to form the tens of thousands of characters of the Chinese writing system. However, as Klaproth and others later pointed out, the Chinese writing system was not "formed from its origin after a general system"; rather, it had evolved gradually from "the necessity of inventing a sign to express some thing or some idea." The idea of classifying characters according to certain elements arose only much later and resulted in several systems with widely different numbers of radicals ranging from a few dozen to over 700 (Klaproth 1828:233-36).

Like many students of Chinese or Japanese, Fourmont had probably memorized characters by associating their elements with specific meanings. A German junior world champion in the memory sport, Christiane Stenger, employs a similar technique for remembering mathematical equations. Each element is assigned a concrete meaning; for example, the minus sign signifies "go backward" or "vomit," the letter A stands for "apple," the letter B for "bear," the letter C for "cirrus fruit," and the mathematical root symbol for a root. Thus, "B minus C" is memorized by imagining a bear vomiting a citrus fruit, and "minus B plus the root of A square" may be pictured as a receding bear who stumbles over a root in which a square apple is embedded.

Stenger's technique, of course, has no connection whatsoever to understanding mathematical formulae, but Fourmont's "keys" can indeed be of help in understanding the meaning of some characters. While such infusion of meaning certainly helped Fourmont and his students Michel-Ange-Andre le Roux DESHAUTERAYES (1724-95) and de Guignes in their study of complicated Chinese characters, it also involved a serious misunderstanding. Stenger understood that bears and fruit were her imaginative creation in order to memorize mathematical formulae and would certainly not have graduated from high school if she had thought that her mathematics teacher wanted to tell her stories about apples and bears.

But mutatis mutandis, this was exactly Fourmont's mistake. Instead of simply accepting the 214 radicals as an artificial system for classifying Chinese characters and as a mnemonic aide, he was convinced that the radicals are a collection of primeval ideas that the Chinese used as a toolset to assemble ideograms representing objects and complex ideas. Fourmont thought that the ancient Chinese had embedded a little story in each character. As he and his disciples happily juggled with "keys," spun stories, and memorized their daily dose of Chinese characters, they did not have any inkling that this fundamentally mistaken view of the genesis of Chinese characters would one day form the root for a mistake of such proportions that it would put de Guignes's entire reputation in jeopardy.

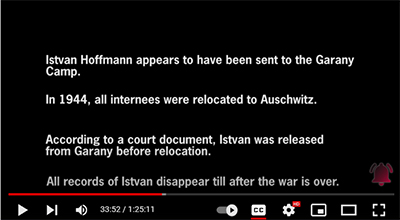

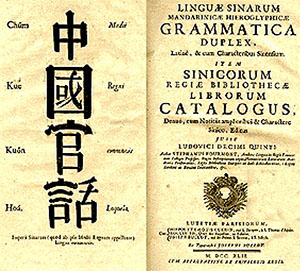

Apart from a series of dictionaries that never came to fruition, Fourmont was also working on a Chinese grammar. He announced its completion in 1728, eight years before the arrival of de Guignes. The first part of this Grammatica sinica with Fourmont's presentation of the 214 "keys" and elements of pronunciation appeared in 1737. The second part, prepared for publication while de Guignes sat at his teacher's feet, contained the grammar proper as well as Fourmont's catalog of Chinese works in the Bibliotheque Royale and was published in 1742. When Fourmont presented the result to the king of France, he had de Guignes accompany him, and the king was so impressed by the twenty-one-year-old linguistic prodigy that he endowed him on the spot with a pension (Michaud 1857:18.126).

But de Guignes's teacher Fourmont had a dirty little secret. He had focused on learning and accumulating data about single Chinese characters, but his knowledge of the Chinese classical and vernacular language was simply not adequate for writing a grammar. By consequence, the man who had let the world know that a genius residing in Europe could master Chinese just as well as the China missionaries decided to plagiarize -- what else? -- the work of a missionary. No one found out about this until Jean-Pierre Abel-Remusat in 1825 carefully compared the manuscript of the Arte de La lengua mandarina by the Spanish Franciscan Francisco Varo with Fourmont's Latin translation and found to his astonishment that Fourmont's ground-breaking Grammatica sinica was a translation of Varo's work (Abel-Remusat 1829:2.298). In an "act of puerile vanity," Abel-Remusat sadly concluded, Fourmont had appropriated Varo's entire text "almost without any change" while claiming that he had never seen it (1826:2.109).2

While de Guignes helped prepare this grammar for publication, Fourmont continued his research on chronology and the history of ancient peoples. During the seventeenth century, ancient Chinese historical sources had become an increasingly virulent threat to biblical chronology and, by extension, to biblical authority. As Fourmont's rival Freret was busy butchering Isaac Newton's lovingly calculated chronology, de Guignes's teacher turned his full attention to the Chinese annals. These annals were in general regarded either as untrustworthy and thus inconsequential or as trustworthy and a threat to biblical authority. However, in a paper read on May 18, 1734, at the Royal Academy of Inscriptions, Fourmont declared with conviction that he could square the circle: the Chinese annals were trustworthy just because they confirmed the Bible.

Dismissing Freret's and Newton's nonbiblical Middle Eastern sources as "scattered scraps," he praised the Chinese annals to the sky as the only ancient record worth studying apart from the Bible (Fourmont 1740:507-8).

But Fourmont's lack of critical acumen is as evident in this paper as in his Critical reflections on the histories of ancient peoples of 1735 and the Meditationes sinicae of 1737. In the "avertissement" to the first volume of the Critical reflections, Fourmont mentions the question of an India traveler, Chevalier Didier, who had conversed with Brahmins and missionaries and came in frustration to Paris to seek Fourmont's opinion about an important question of origins: had Indian idolatry influenced Egyptian idolatry or vice versa? Fourmont delivered his answer after nearly a thousand tedious pages full of chronological juggling:With regard to customs in general, since India is entirely Egyptian and Osiris led several descendants of Abraham there, we have the first cause of that resemblance of mores in those two nations; but with regard to the religion of the Indians, they only received it subsequently through commerce and through the colonies coming from Egypt. (Fourmont 1735:2-499)

For Fourmont the Old Testament was the sole reliable testimony of antediluvian times, and he argued that the reliability of other accounts decreases with increasing distance from the landing spot of Noah's ark. Only the Chinese, whose "language is the oldest of the universe," remain a riddle, as their antiquity "somehow rivals that of Genesis and has caused the most famous chronologists to change their system" (1735:1.lii). But would not China's "hieroglyphic" writing system also indicate Egyptian origins? Though Fourmont suspected an Egyptian origin of Chinese writing, he could not quite figure out the exact mechanism and transmission. He suspected that "Hermes, who passed for the inventor of letters" had not invented hieroglyphs but rather "on one hand more perfect hieroglyphic letters, which were brought to the Chinese who in turn repeatedly perfected theirs; and on the other hand alphabetic letters" (Fourmont 1735:2.500). These "more perfect hieroglyphs" that "seemingly existed with the Egyptian priests" are "quite similar to the Chinese characters of today" (p. 500).

Fourmont was studying whether there was any support for Kircher's hypothesis that the letters transmitted from Egypt to the Chinese were related to Coptic monosyllables (p. 503); but though he apparently did not find conclusive answers to such questions, the problem itself and Fourmont's basic direction (transmission from Egypt to China, some kind of more perfect hieroglyphs) must have been so firmly planted in his student de Guignes's mind that it could grow into the root over which he later stumbled. Fourmont's often repeated view that Egypt's culture was not as old as that of countries closer to the landing spot of Noah's ark made it clear that those who regarded Egypt as the womb of all human culture were dead wrong and that China, in spite of its ancient culture, was a significant step removed from the true origins.

Though the Chinese had received their writing system and probably also the twin ideas that in his view "properly constitute Egyptianism" -- the idea of metempsychosis and the adoration of animals and plants (p. 492) -- Fourmont credited the Chinese with subsequent improvements also in this respect: "My studies have thus taught me that the Chinese were a wise people, the most ancient of all peoples, but the first also, though idolatrous, that rid itself of the mythological spirit" (Fourmont 1735:2.liv). This accounted for their excellent historiography and voluminous literature:I said that the Chinese Annals can be regarded as a respectable work. First of all, as everybody admits, for more than 3,500 years China has been populated, cultivated, and literate. Secondly, has it lacked authors as its people still read books, though few in number, written before Abraham? Thirdly, since few scholars know the Chinese books, let me here point out that the Chinese Annals are not bits and pieces of histories scattered here and there like the Latin and Greek histories which must be stitched together: they consist of at least 150 volumes that, without hiatus and the slightest interruption, present a sequence of 22 families which all reigned for 3, 4, 8, 10 centuries. (p. liv)

While Fourmont cobbled together hypotheses and conjectures, the Bible always formed the backdrop for his speculations about ancient history. A telling example is his critique of the Chinese historian OUYANG Xiu (1007-72), who argued that from the remote past, humans had always enjoyed roughly similar life spans. Lambasting this view as that of a "skeptic," Fourmont furnished the following argument as "proof" of the reliability of ancient Chinese histories:We who possess the sacred writ: must we not on the contrary admire the Chinese annals when they, just in the time period of Arphaxad, Saleh, Heber, Phaleg, Rea, Sarug, Nachor, Abraham, etc., present us with men who lived precisely the same number of years? Now if someone told us that Seth at the age of 550 years married one of his grand-grand-nieces in the fourteenth generation: who of us would express the slightest astonishment? ... It is thus clear that all such objections are frivolous, and furthermore, that attacks against the Chinese annals on account of a circumstance [i.e., excessive longevity] which distinguishes them from all other books will actually tie them even more to Scripture and will be a sure means to increase their authority. (Fourmont 1740:514)

No comment is needed here.

Immediately after Fourmont's death in 1745, the twenty-four-year-old Joseph de Guignes replaced his master as secretary interpreter of oriental languages at the Royal Library. It was the beginning of an illustrious career: royal censor and attache to the journal des Scavans in 1752, member of the Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in 1753, chair of Syriac at the College Royal from 1757 to 1773, garde des antiques at the Louvre in 1769, editor of the Journal des Savants, and other honors (Michaud 1857:18.(27). De Guignes had, like his master Fourmont, a little problem. The pioneer Sinologists in Paris were simply unable to hold a candle to the China missionaries. Since 1727 Fourmont had been corresponding with the figurist China missionary Joseph Henry PREMARE (1666-1736), who, unlike Fourmont, was an accomplished Sinologist (see Chapter 5). Premare was very liberal with his advice and sent, apart from numerous letters, his Notitia Linguae sinicae to Fourmont in 1728. This was, in the words of Abel-Remusat,neither a simple grammar, as the author too modestly calls it, nor a rhetoric, as Fourmont intimated; it is an almost complete treatise of literature in which Father Premare not only included everything that he had collected about the usage of particles and grammatical rules of the Chinese but also a great number of observations about the style, particular expressions in ancient and common idiom, proverbs, most frequent patterns -- and everything supported by a mass of examples cited from texts, translated and commented when necessary. (Abel-Remusat 1829:2.269)

Premare thus sent Fourmont his "most remarkable and important work," which was "without any doubt the best of all those that Europeans have hitherto composed on these matters" (p. 269).

But instead of publishing this vastly superior work and making the life of European students of Chinese considerably easier, Fourmont compared it unfavorably to his own (partly plagiarized) product and had Premare's masterpiece buried in the Royal Library, where it slept until Abel-Remusat rediscovered it in the nineteenth century (pp. 269-73). However, Fourmont's two disciples Deshauterayes and de Guignes could profit from such works since Fourmont for years kept the entire China-related collection of the Royal Library at his home where the two disciples had their rooms; thus Premare was naturally one of the Sinologists who influenced de Guignes.4 So was Antoine GAUBIL (1689-1759), whose reputation as a Sinologist was deservedly great.

But there is a third, extremely competent Jesuit Sinologist who remained in the shadows, though his knowledge of Chinese far surpassed that of de Guignes and all other Europe-based early Sinologists (and, one might add, even many modern ones). His works suffered a fate resembling that of the man who was in many ways his predecessor, Joao Rodrigues (see Chapter 1) in that they were used but rarely credited. The man in question was Claude de VISDELOU (1656-1737), who spent twenty-four years in China (1685-1709) and twenty-eight years in India (1709-37). One can say without exaggeration that the famous Professor de Guignes owed this little-known missionary a substantial part of his fame -- and this was his dirty little secret.

-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

Arcadio Huang

Traditional Chinese 黃嘉略

Simplified Chinese 黄嘉略

Arcadio Huang (Chinese: 黃嘉略, born in Xinghua, modern Putian, in Fujian, 15 November 1679, died on 1 October 1716 in Paris)[1][2] was a Chinese Christian convert, brought to Paris by the Missions étrangères [Paris Foreign Missions Society]. He took a pioneering role in the teaching of the Chinese language in France around 1715. He was preceded in France by his compatriot Michael Shen Fu-Tsung, who visited the country in 1684.

His main works, conducted with the assistance of young Nicolas Fréret, are the first Chinese-French lexicon, the first Chinese grammar of the Chinese, and the diffusion in France of the Kangxi system with two hundred fourteen radicals, which was used in the preparation of his lexicon.

His early death in 1716 prevented him from finishing his work, however, and Étienne Fourmont, who received the task of sorting his papers, assumed all the credit for their publication.

Only the insistence of Nicolas Fréret, as well as the rediscovery of the memories of Huang Arcadio have re-established the pioneering work of Huang, as the basis which enabled French linguists to address more seriously the Chinese language.

Origins

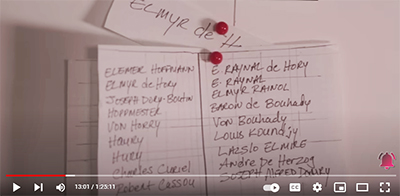

Here is the genealogy of Arcadio Huang (originally spelled Hoange) according to Stephen Fourmont:

"Paul Huang, of the Mount of the Eagle, son of Kian-khin (Kiam-kim) Huang, Imperial assistant of the provinces of Nâne-kin (Nanjing) and Shan-ton (Shandong), and lord of the Mount of the Eagle, was born in the city of Hin-houa (Xinghua), in the province of Fò-kién (Fujian), Feb. 12, 1638; was baptized by the Jesuit Father Antonio de Govea, Portuguese, and was married in 1670 with the Miss Apollonie la Saule, named Léou-sien-yâm (Leù-sièn-yam) in the local language, daughter of Mr. Yâm, nicknamed Lou-ooue (Lû-ve), lord Doctor of Leôu-sièn (Leû-sièn) and governor of the city of Couan-sine (Guangxin), in the province of Kiam-si (Jiangxi). Arcadio Huang, interpreter of the King of France, son of Paul Huang, was born in the same city of Hin-Houa, on November 15, 1679, and was christened on November 21 of that year by the Jacobin Father Arcadio of ..., of Spanish nationality. Through his marriage, he had a daughter who is still alive; he added to his genealogy Marie-Claude Huang, of the Eagle Mountain, daughter of Mr. Huang, interpreter to the king, and so on.; She was born March 4, 1715."

He received the education of a Chinese literatus under the protection of French missionaries. The French missionaries saw in Arcadio an opportunity to create a "literate Chinese Christian" in the service of the evangelization of China. In these pioneer years (1690–1700), it was urgent to present to Rome examples of perfectly Christianized Chinese, in order to reinforce the Jesuits' position in the [Chinese] Rites controversy.

Journey to the West

Artus de Lionne (1655–1713), here in 1686, brought Arcadio Huang to Europe and France in 1702.

On 17 February 1702, under the protection of Artus de Lionne, Bishop of Rosalie,[3] Arcadio embarked on a ship of the English East India Company in order to reach London. By September or October 1702, Mr. de Rosalie and Arcadio left England for France, in order to travel to Rome.

On the verge of being ordained a priest in Rome and being presented to the pope to demonstrate the reality of Chinese Christianity, Arcadio Huang apparently renounced and declined ordination. Rosalie preferred to return to Paris to further his education, and wait for a better answer.

Installation in Paris

According to his memoirs, Arcadio moved to Paris in 1704 or 1705 at the home of the Foreign Missions [Paris Foreign Missions Society]. There, his protectors continued his religious and cultural training, with plans to ordain him for work in China. But Arcadio preferred life as a layman. He settled permanently in Paris as a "Chinese interpreter to the Sun King" and began working under the guidance and protection of abbot Jean-Paul Bignon.[3] It is alleged that he also became the king's librarian in charge of cataloging Chinese books in the Royal library.[2]

Huang encountered Montesquieu, with whom he had many discussions about Chinese customs.[4] Huang is said to have been Montesquieu's inspiration for the narrative device in his Persian Letters, an Asian who discusses the customs of the West.[5]

Huang became very well-known in Parisian salons. In 1713 Huang married a Parisian woman named Marie-Claude Regnier.[2] In 1715 she gave birth to a healthy daughter, also named Marie-Claude, but the mother died a few days later. Discouraged, Huang himself died a year and a half later, and their daughter died a few months after that.[2]

Work on the Chinese language

Helped by the young Nicolas Fréret (1688–1749), he began the hard work of pioneering a Chinese-French dictionary, a Chinese grammar, employing the Kangxi system of 214 character keys.

In this work, they were joined by Nicolas Joseph Delisle (1683–1745), a friend of Fréret, who gave a more cultural and geographical tone to their work and discussions. Deslisle's brother, Guillaume Delisle, was already a renowned geographer. Delisle encouraged Arcadio Huang to read Europe's best known and popular writings dealing with the Chinese Empire. Huang was surprised by the ethnocentric approach of these texts, reducing the merits of the Chinese people and stressing the civilizing role of the European peoples.

A third apprentice, by the name of Étienne Fourmont (imposed by Abbé Bignon), arrived and profoundly disturbed the team. One day, Fourmont was surprised copying Huang's work.[6]

Debate after his death

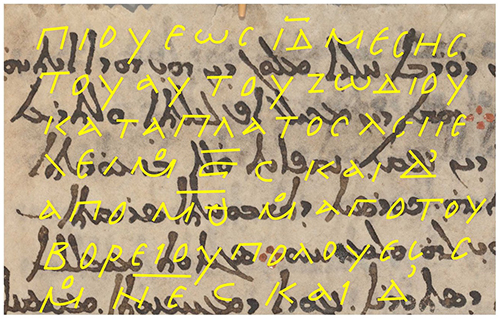

The Chinese grammar published by Étienne Fourmont in 1742

After the death of Huang on 1 October 1716, Fourmont became officially responsible for classifying papers of the deceased. He made a very negative report on the contents of these documents and continued to criticize the work of Huang. Continuing his work on the languages of Europe and Asia (and therefore the Chinese), he took all the credit for the dissemination of the 214 key system in France, and finally published a French-Chinese lexicon and a Chinese grammar, without acknowledging the work of Huang, whom he was continuing to denigrate publicly.

Meanwhile, Fréret, also an Academician, and above all a friend and first student of Arcadio Huang, wrote a thesis on the work and role of Arcadio in the dissemination of knowledge about China in France. Documents saved by Nicolas-Joseph Delisle, Arcadio's second student, also helped to publicize the role of the Chinese subject of the king of France.

Since then, other researchers and historians investigated his role, including Danielle Elisseeff who compiled Moi, Arcade interprète chinois du Roi Soleil in 1985.

See also

• Shen Fo-tsung, another Chinese person who visited France in 1684.

• Fan Shouyi, yet another Chinese person who lived in Europe in the early eighteenth century.

• Chinese diaspora in France

• China–France relations

• Jesuit China missions

Notes

1. First name also given as Arcadius (Latin) or Arcade (French); family name as Hoange, Ouange, Houange, etc...

2. Mungello, p.125

3. Barnes, p.82

4. Barnes, p.85

5. Conn, p.394

6. Danielle Elisseeff, Moi Arcade, interprète du roi-soleil, édition Arthaud, Paris, 1985.

References

• Barnes, Linda L. (2005) Needles, Herbs, Gods, and Ghosts: China, Healing, and the West to 1848 Harvard University Press ISBN 0-674-01872-9

• Conn, Peter (1996) Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Biography Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-56080-2

• Elisseeff, Danielle, Moi, Arcade, interprète chinois du Roi Soleil, Arthaud Publishing, Paris, 1985, ISBN 2-7003-0474-8 (Main source for this article, 189 pages)

• Fourmont, Etienne (1683–1745), Note on Arcadius Hoang.

• Mungello, David E. (2005) The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500-1800 Rowman & Littlefield ISBN 0-7425-3815-X

• Spence, Jonathan D. (1993). "The Paris Years of Arcadio Huang". Chinese Roundabout: Essays in History and Culture. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30994-2.

• Xu Minglong (2004) 许明龙 Huang Jialüe yu zao qi Faguo Han xue 黃嘉略与早期法囯汉学, Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.