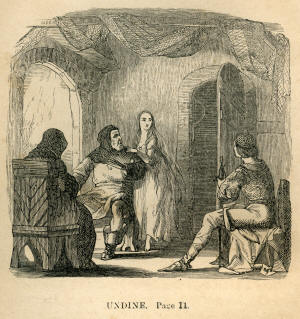

CHAPTER 4: OF THAT WHICH BEFEL THE KNIGHT IN THE WOOD"IT may now be eight days ago when I entered the free city which lies on the other side of the forest. Soon afterwards was held a fair tournament and tiltings, and I spared neither my steed nor my lance. Once, as I was standing still in the lists to rest myself from the joyous labour, my eyes fell on a wondrously fair lady, who, in most splendid attire, was standing in one of the balconies, and looking on. I inquired of those about me, and learnt that the lovely maiden was called Bertalda, and that she was the adopted daughter of a mighty duke who dwelt in that land. I marked that she too saw me, and, as is the wont with us young knights, if I had bravely fought before, now did I fight with higher courage. That evening I was Bertalda's partner in the dance, and so I remained all the days of the festival."

A sharp pain in his left hand, which was hanging down, here interrupted Huldbrand's story, and made him look whence came the smart. Undine had fixed her pearly teeth in his finger, and now seemed gloomy and displeased; but suddenly she looked up at him with gentle sorrowful eyes, and whispered very softly, "It was thine own fault;" then she hid her face; and the knight, perplexed and thoughtful, continued his relation.

"This lady Bertalda is a strange, haughty maiden; she pleased me not so much the second day as the first, and the third still less. But I remained in attendance on her because she seemed more favourable to me than to the other knights; and it even chanced that in sport I begged a glove from her. 'On condition that thou wilt go alone,' she answered, 'to bring me tidings of what passes in the famous forest.' I recked little of her glove, but I had spoken the word, and an honour-loving knight will not require a second summons to give a proof of courage."

"I thought that she loved thee," interrupted Undine.

"So it seemed," answered Huldbrand.

"Now then," cried the maiden laughing, "She must be right foolish, to drive from her him whom she loved, and into a perilous forest! The forest and its mysteries would have waited long enough for me."

"Yester morning I set off on my way," proceeded the knight, smiling fondly at Undine; "the stems of the trees looked so brilliant and graceful in the morning light, which lay brightly on the green grass, the leaves whispered so gaily together, that I laughed in my heart at the people who, in this beautiful spot, could expect something terrific. 'The wood will quickly be passed through, both going and coming,' I said to myself with gay confidence; and before I was aware I had plunged deep into the green shades, and could no longer see the plain which lay behind me. Then first it struck me that I could very easily lose myself in this mighty forest, and that perchance this was the only peril that here threatened the traveller. I therefore stopped, and looked round at the position of the sun, which had now risen higher. As I thus gazed up, I saw a black thing in the branches of a high oak. I at first thought it was a bear, and I felt for my sword; then a man's voice, but most harsh and odious, spoke down to me: 'If I did not now break off twigs up here, how shouldst thou be roasted at midnight, Sir Wiseacre?' And then he grinned, and rustled the branches, till my horse became wild, and carried me away before I had time to see exactly what sort of a devil's beast it was."

"Thou must not name him," said the old fisherman, and crossed himself; his wife did the same, in silence; Undine looked at her lover with sparkling eyes, and said:

"The best of the story is, that they have not roasted him. Go on, thou beautiful youth."

The knight continued his tale:

"I was in danger of being dashed by my terrified horse against the stems and branches of the trees; he was streaming from dread and heat, and yet would not suffer me to hold him in. At length, he took his way straight towards a rocky precipice, when, suddenly, it seemed to me as if a tall white man threw himself directly before the maddened animal. It started from him, and stood still. I recovered the mastery over him, and then first saw that my deliverer was no white man, but a brook of silvery brightness, which rushed down from a hill close by me, impetuously crossing and stemming the course of my steed."

"Thanks, dear brook!" cried Undine, clapping her little hands. But the old man shook his head, and looked down in deep thought.

"I had hardly fixed myself again in my saddle, and properly seized the reins," continued Huldbrand, "when there stood at my side a strange little man, diminutive and hideous beyond measure, of a tawny colour, and with a nose not much smaller than all the rest of his body. He grinned in clownish courtesy with his wide-slit mouth, and scraped his foot, and bowed a thousand times.

"As this fool's-play pleased me very ill, I thanked him shortly, and turned around my still trembling horse, thinking to seek out for myself some other adventure; or, if I found none, to take my homeward way; for during my wild flight, the sun had gone down from its mid-day height towards the west. But the little fellow sprang round with the quickness of lightning, and still stood before my horse. 'Make room there,' I cried, angrily; 'the animal is fiery, and will easily run you down.'

"'Ay!' growled the wretch, and laughed yet more stupidly and fearfully; 'give me first a drink-money, for I stopped your little horse; but for me, you and your little horse would now be lying in the rocky chasm yonder. Ha!'

"'Make no more faces,' I said, 'and take thy gold, although thou liest; for see, the good brook yonder saved me, but not thou, thou most miserable wight!"

"And at the same time I let fall a piece of gold into his strange-shaped cap, which he had held before me, as if begging. Then I rode on; but he still shrieked behind me, and suddenly, with inconceivable swiftness, he was at my side. I urged my horse to a gallop; he galloped with me, although it seemed to become very painful to him, and he took strange springs, half laughable, half horrible, ever holding up the piece of gold, and shrieking out at every spring, "False gold! false coin! false coin! false gold!' and this came with so cracked a sound out of his hollow breast, that it seemed as if, at each shriek, he must fall dead to the ground. His hideous red tongue hung out of his cavern of a mouth. I stopped bewildered and asked: 'What wilt thou have, with thy cries? Take another piece of gold, take two, but then leave me.' He began anew his horribly courteous greetings, and growled out: 'Not gold; it shall not be gold, young sir; I have myself too much of that sport; I will show you.'

"All at once it seemed that I could see through the solid green ground, as it had been green glass; and the flat earth became round, and, within, a group of goblins were taking their pastime with silver and gold. They played at ball, some standing on their heads, some on their heels; they pelted each other in jest with the precious metals, and threw gold-dust in each other's faces. My hateful companion stood half on the ground, half within it; he made the others give him handfuls of gold, showed it to me laughing, and then flung it again clattering down the bottomless chasm. Then he showed the piece of gold which I had given him to the goblins within, and they laughed to death at it, and hissed out at me. At length, they all stretched out their sharp blackened fingers towards me, and up climbed the swarm, more and more wild, more and more dense, more and more maddening. Then a terror seized me, as before it had seized my horse. I plunged my spurs into him, and know not how far I was, for the second time, desperately carried away into the forest.

"But when at length I stopped, the coolness of evening was around me. I saw a white footpath shining through the branches, and deemed that it must lead from the forest back to the town. I was about to force my way through it, but a white indistinct face, with ever-varying features, looked out at me from between the leaves; I endeavoured to avoid it, but wherever I went there was the face. I grew angry, and at length spurred my horse against it; but then the phantom dashed a white foam upon me and my horse, and we turned away from it half blinded. Thus it drove us, step by step, back from the footpath, and only in one direction did it leave the way open to us; but when we took that, although it followed us close, it did not do us the least injury. When I looked around at it, from time to time, I marked well that the white foamy face belonged to an equally white body of gigantic stature. Often I even thought that it was a wandering torrent: but I never could gain any certainty on this.

"Horse and knight, both wearied out, yielded to the white man who urged us forward, and ever nodded his head, as if to say, 'Quite right! quite right!' So we at length came to the end of the wood, and out here, where I saw grass, and lake, and your little hut, and the white man vanished."

"It is well that he is gone," said the fisherman; and then he began to discourse as to how his guest might best return to the city and to his followers. Thereupon Undine began to laugh to herself very softly. Huldbrand remarked it, and said:

"I thought that thou wast glad to see me here; why art thou then rejoicing when the talk is of my departure?"

"Because thou canst not go forth," answered Undine. "Try only to pass that overflowing stream in a boat, either with thy horse or alone, as thou pleasest -- or rather try it not, for thou wouldst be crushed by the rushing down of the uprooted trees and shivered rocks; and as to the lake, I know that father dares not venture far enough out upon it in his boat."

Huldbrand rose, smiling, to see whether it was as Undine said; the old man accompanied him, and the maiden frolicked gaily beside them. They found, in fact, that Undine had spoken truly, and that the knight must consent to remain on the peninsula, now turned into an island, until the waters were abated. As they all three returned to the cottage, the knight whispered in the maiden's ear:

"How is it, little Undine? Art thou angry that I stay?"

"Ah!" answered she, peevishly, "do not talk to me. If I had not bitten thee, who knows what more might have been told of Bertalda in thy tale ?"