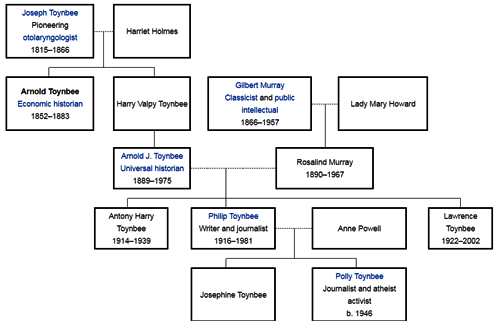

Part 2 of 2

Literary criticismMain article: Samuel Johnson's literary criticism

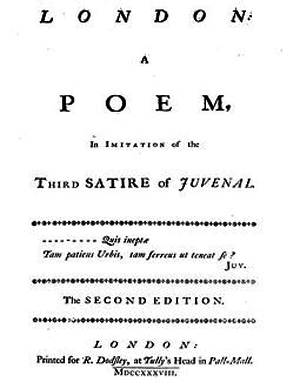

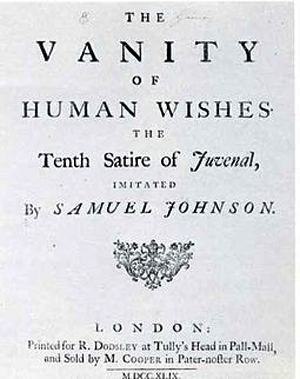

The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749) title page

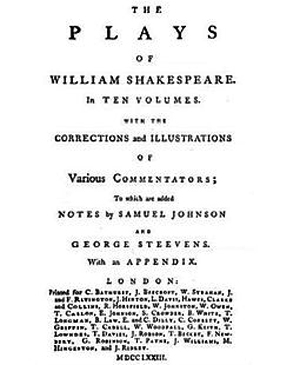

The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749) title pageJohnson's works, especially his Lives of the Poets series, describe various features of excellent writing. He believed that the best poetry relied on contemporary language, and he disliked the use of decorative or purposefully archaic language.[175] He was suspicious of the poetic language used by Milton, whose blank verse he believed would inspire many bad imitations. Also, Johnson opposed the poetic language of his contemporary Thomas Gray.[176] His greatest complaint was that obscure allusions found in works like Milton's Lycidas were overused; he preferred poetry that could be easily read and understood.[177] In addition to his views on language, Johnson believed that a good poem incorporated new and unique imagery.[178]

In his smaller poetic works, Johnson relied on short lines and filled his work with a feeling of empathy, which possibly influenced Housman's poetic style.[179] In London, his first imitation of Juvenal, Johnson uses the poetic form to express his political opinion and, as befits a young writer, approaches the topic in a playful and almost joyous manner.[180] However, his second imitation, The Vanity of Human Wishes, is completely different; the language remains simple, but the poem is more complicated and difficult to read because Johnson is trying to describe complex Christian ethics.[181] These Christian values are not unique to the poem, but contain views expressed in most of Johnson's works. In particular, Johnson emphasises God's infinite love and shows that happiness can be attained through virtuous action.[182]

A caricature of Johnson by James Gillray mocking him for his literary criticism; he is shown doing penance for Apollo and the Muses with Mount Parnassus in the background.

A caricature of Johnson by James Gillray mocking him for his literary criticism; he is shown doing penance for Apollo and the Muses with Mount Parnassus in the background.When it came to biography, Johnson disagreed with Plutarch's use of biography to praise and to teach morality. Instead, Johnson believed in portraying the biographical subjects accurately and including any negative aspects of their lives. Because his insistence on accuracy in biography was little short of revolutionary, Johnson had to struggle against a society that was unwilling to accept biographical details that could be viewed as tarnishing a reputation; this became the subject of Rambler 60.[183] Furthermore, Johnson believed that biography should not be limited to the most famous and that the lives of lesser individuals, too, were significant;[184] thus in his Lives of the Poets he chose both great and lesser poets. In all his biographies he insisted on including what others would have considered trivial details to fully describe the lives of his subjects.[185] Johnson considered the genre of autobiography and diaries, including his own, as one having the most significance; in Idler 84 he explains how a writer of an autobiography would be the least likely to distort his own life.[186]

Johnson's thoughts on biography and on poetry coalesced in his understanding of what would make a good critic. His works were dominated with his intent to use them for literary criticism. This was especially true of his Dictionary of which he wrote: "I lately published a Dictionary like those compiled by the academies of Italy and France, for the use of such as aspire to exactness of criticism, or elegance of style".[187] Although a smaller edition of his Dictionary became the standard household dictionary, Johnson's original Dictionary was an academic tool that examined how words were used, especially in literary works. To achieve this purpose, Johnson included quotations from Bacon, Hooker, Milton, Shakespeare, Spenser, and many others from what he considered to be the most important literary fields: natural science, philosophy, poetry, and theology. These quotations and usages were all compared and carefully studied in the Dictionary so that a reader could understand what words in literary works meant in context.[188]

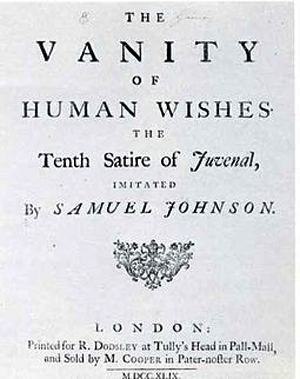

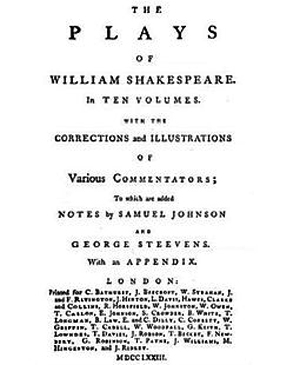

Plays of William Shakespeare (1773 expanded edition) title page

Plays of William Shakespeare (1773 expanded edition) title pageJohnson did not attempt to create schools of theories to analyse the aesthetics of literature. Instead, he used his criticism for the practical purpose of helping others to better read and understand literature.[189] When it came to Shakespeare's plays, Johnson emphasised the role of the reader in understanding language: "If Shakespeare has difficulties above other writers, it is to be imputed to the nature of his work, which required the use of common colloquial language, and consequently admitted many phrases allusive, elliptical, and proverbial, such as we speak and hear every hour without observing them".[190]

His works on Shakespeare were devoted not merely to Shakespeare, but to understanding literature as a whole; in his Preface to Shakespeare, Johnson rejects the previous dogma of the classical unities and argues that drama should be faithful to life.[191] However, Johnson did not only defend Shakespeare; he discussed Shakespeare's faults, including his lack of morality, his vulgarity, his carelessness in crafting plots, and his occasional inattentiveness when choosing words or word order.[192] As well as direct literary criticism, Johnson emphasised the need to establish a text that accurately reflects what an author wrote. Shakespeare's plays, in particular, had multiple editions, each of which contained errors caused by the printing process. This problem was compounded by careless editors who deemed difficult words incorrect, and changed them in later editions. Johnson believed that an editor should not alter the text in such a way.[193]

Character sketchFurther information: Political views of Samuel Johnson and Religious views of Samuel Johnson

After we came out of the church, we stood talking for some time together of Bishop Berkeley's ingenious sophistry to prove the non-existence of matter, and that every thing in the universe is merely ideal. I observed, that though we are satisfied his doctrine is not true, it is impossible to refute it. I never shall forget the alacrity with which Johnson answered, striking his foot with mighty force against a large stone, till he rebounded from it, 'I refute it thus.'[194]

-- Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson

Johnson's tall[a] and robust figure combined with his odd gestures were confusing to some; when William Hogarth first saw Johnson standing near a window in Samuel Richardson's house, "shaking his head and rolling himself about in a strange ridiculous manner", Hogarth thought Johnson an "ideot, whom his relations had put under the care of Mr. Richardson".[196] Hogarth was quite surprised when "this figure stalked forwards to where he and Mr. Richardson were sitting and all at once took up the argument ... [with] such a power of eloquence, that Hogarth looked at him with astonishment, and actually imagined that this ideot had been at the moment inspired".[196] Beyond appearance, Adam Smith claimed that "Johnson knew more books than any man alive",[197] while Edmund Burke thought that if Johnson were to join Parliament, he "certainly would have been the greatest speaker that ever was there".[198] Johnson relied on a unique form of rhetoric, and he is well known for his "refutation" of Bishop Berkeley's immaterialism, his claim that matter did not actually exist but only seemed to exist:[199] during a conversation with Boswell, Johnson powerfully stomped a nearby stone and proclaimed of Berkeley's theory, "I refute it thus!"[194]

Johnson was a devout, conservative Anglican and a compassionate man who supported a number of poor friends under his own roof, even when unable to fully provide for himself.[39] Johnson's Christian morality permeated his works, and he would write on moral topics with such authority and in such a trusting manner that, Walter Jackson Bate claims, "no other moralist in history excels or even begins to rival him".[200] However, Johnson's moral writings do not contain, as Donald Greene points out, "a predetermined and authorized pattern of 'good behavior'", even though Johnson does emphasise certain kinds of conduct.[201] He did not let his own faith prejudice him against others, and had respect for those of other denominations who demonstrated a commitment to Christ's teachings.[202] Although Johnson respected John Milton's poetry, he could not tolerate Milton's Puritan and Republican beliefs, feeling that they were contrary to England and Christianity.[203] He was an opponent of slavery on moral grounds, and once proposed a toast to the "next rebellion of the negroes in the West Indies".[204] Beside his beliefs concerning humanity, Johnson is also known for his love of cats,[205] especially his own two cats, Hodge and Lily.[205] Boswell wrote, "I never shall forget the indulgence with which he treated Hodge, his cat.[206]

Johnson was also known as a staunch Tory; he admitted to sympathies for the Jacobite cause during his younger years but, by the reign of George III, he came to accept the Hanoverian Succession.[203] It was Boswell who gave people the impression that Johnson was an "arch-conservative", and it was Boswell, more than anyone else, who determined how Johnson would be seen by people years later. However, Boswell was not around for two of Johnson's most politically active periods: during Walpole's control over British Parliament and during the Seven Years' War. Although Boswell was present with Johnson during the 1770s and describes four major pamphlets written by Johnson, he neglects to discuss them because he is more interested in their travels to Scotland. This is compounded by the fact that Boswell held an opinion contradictory to two of these pamphlets, The False Alarm and Taxation No Tyranny, and so attacks Johnson's views in his biography.[207]

In his Life of Samuel Johnson Boswell referred to Johnson as 'Dr. Johnson' so often that he would always be known as such, even though he hated being called such. Boswell's emphasis on Johnson's later years shows him too often as merely an old man discoursing in a tavern to a circle of admirers.[208] Although Boswell, a Scotsman, was a close companion and friend to Johnson during many important times of his life, like many of his fellow Englishmen Johnson had a reputation for despising Scotland and its people. Even during their journey together through Scotland, Johnson "exhibited prejudice and a narrow nationalism".[209] Hester Thrale, in summarising Johnson's nationalistic views and his anti-Scottish prejudice, said: "We all know how well he loved to abuse the Scotch, & indeed to be abused by them in return."[210]

HealthMain article: Samuel Johnson's health

Johnson had several health problems, including childhood tuberculous scrofula resulting in deep facial scarring, deafness in one ear and blindness in one eye, gout, testicular cancer, and a stroke in his final year that left him unable to speak; his autopsy indicated that he had pulmonary fibrosis along with cardiac failure probably due to hypertension, a condition then unknown. Johnson displayed signs consistent with several diagnoses, including depression and Tourette syndrome.

There are many accounts of Johnson suffering from bouts of depression and what Johnson thought might be madness. As Walter Jackson Bate puts it, "one of the ironies of literary history is that its most compelling and authoritative symbol of common sense—of the strong, imaginative grasp of concrete reality—should have begun his adult life, at the age of twenty, in a state of such intense anxiety and bewildered despair that, at least from his own point of view, it seemed the onset of actual insanity".[211] To overcome these feelings, Johnson tried to constantly involve himself with various activities, but this did not seem to help. Taylor said that Johnson "at one time strongly entertained thoughts of Suicide".[212] Boswell claimed that Johnson "felt himself overwhelmed with an horrible melancholia, with perpetual irritation, fretfulness, and impatience; and with a dejection, gloom, and despair, which made existence misery".[213]

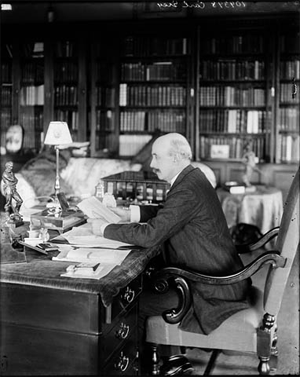

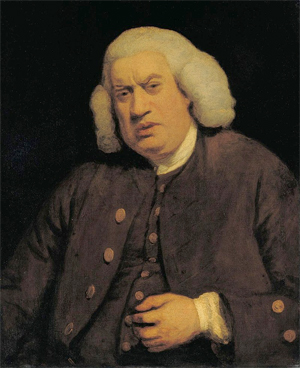

Reynolds' 1769 portrait depicting Johnson's "odd gesticulations"[214]

Reynolds' 1769 portrait depicting Johnson's "odd gesticulations"[214]Early on, when Johnson was unable to pay off his debts, he began to work with professional writers and identified his own situation with theirs.[215] During this time, Johnson witnessed Christopher Smart's decline into "penury and the madhouse", and feared that he might share the same fate.[215] Hester Thrale Piozzi claimed, in a discussion on Smart's mental state, that Johnson was her "friend who feared an apple should intoxicate him".[126] To her, what separated Johnson from others who were placed in asylums for madness—like Christopher Smart—was his ability to keep his concerns and emotions to himself.[126]

Two hundred years after Johnson's death, the posthumous diagnosis of Tourette syndrome became widely accepted.[216] The condition was unknown during Johnson's lifetime, but Boswell describes Johnson displaying signs of Tourette syndrome, including tics and other involuntary movements.[217][218] According to Boswell "he commonly held his head to one side ... moving his body backwards and forwards, and rubbing his left knee in the same direction, with the palm of his hand ... [H]e made various sounds" like "a half whistle" or "as if clucking like a hen", and "... all this accompanied sometimes with a thoughtful look, but more frequently with a smile. Generally when he had concluded a period, in the course of a dispute, by which time he was a good deal exhausted by violence and vociferation, he used to blow out his breath like a Whale."[219] There are many similar accounts; in particular, Johnson was said to "perform his gesticulations" at the threshold of a house or in doorways.[220] When asked by a little girl why he made such noises and acted in that way, Johnson responded: "From bad habit."[219] The diagnosis of the syndrome was first made in a 1967 report,[221] and Tourette syndrome researcher Arthur K. Shapiro described Johnson as "the most notable example of a successful adaptation to life despite the liability of Tourette syndrome".[222] Details provided by the writings of Boswell, Hester Thrale, and others reinforce the diagnosis, with one paper concluding:

[Johnson] also displayed many of the obsessional-compulsive traits and rituals which are associated with this syndrome ... It may be thought that without this illness Dr Johnson's remarkable literary achievements, the great dictionary, his philosophical deliberations and his conversations may never have happened; and Boswell, the author of the greatest of biographies would have been unknown.[223]

Legacy Statue of Dr Johnson erected in 1838 opposite the house where he was born at Lichfield's Market Square. There are also statues of him in London and Uttoxeter.[224]

Statue of Dr Johnson erected in 1838 opposite the house where he was born at Lichfield's Market Square. There are also statues of him in London and Uttoxeter.[224]Johnson was, in the words of Steven Lynn, "more than a well-known writer and scholar";[225] he was a celebrity for the activities and the state of his health in his later years were constantly reported in various journals and newspapers, and when there was nothing to report, something was invented.[226] According to Bate, "Johnson loved biography," and he "changed the whole course of biography for the modern world. One by-product was the most famous single work of biographical art in the whole of literature, Boswell's Life of Johnson, and there were many other memoirs and biographies of a similar kind written on Johnson after his death."[3] These accounts of his life include Thomas Tyers's A Biographical Sketch of Dr Samuel Johnson (1784);[227] Boswell's The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (1785); Hester Thrale's Anecdotes of the Late Samuel Johnson, which drew on entries from her diary and other notes;[228] John Hawkins's Life of Samuel Johnson, the first full-length biography of Johnson;[229] and, in 1792, Arthur Murphy's An Essay on the Life and Genius of Samuel Johnson, which replaced Hawkins's biography as the introduction to a collection of Johnson's Works.[230] Another important source was Fanny Burney, who described Johnson as "the acknowledged Head of Literature in this kingdom" and kept a diary containing details missing from other biographies.[231] Above all, Boswell's portrayal of Johnson is the work best known to general readers. Although critics like Donald Greene argue about its status as a true biography, the work became successful as Boswell and his friends promoted it at the expense of the many other works on Johnson's life.[232]

In criticism, Johnson had a lasting influence, although not everyone viewed him favourably. Some, like Macaulay, regarded Johnson as an idiot savant who produced some respectable works, and others, like the Romantic poets, were completely opposed to Johnson's views on poetry and literature, especially with regard to Milton.[233] However, some of their contemporaries disagreed: Stendhal's Racine et Shakespeare is based in part on Johnson's views of Shakespeare,[191] and Johnson influenced Jane Austen's writing style and philosophy.[234] Later, Johnson's works came into favour, and Matthew Arnold, in his Six Chief Lives from Johnson's "Lives of the Poets", considered the Lives of Milton, Dryden, Pope, Addison, Swift, and Gray as "points which stand as so many natural centres, and by returning to which we can always find our way again".[235]

More than a century after his death, literary critics such as G. Birkbeck Hill and T. S. Eliot came to regard Johnson as a serious critic. They began to study Johnson's works with an increasing focus on the critical analysis found in his edition of Shakespeare and Lives of the Poets.[233] Yvor Winters claimed that "A great critic is the rarest of all literary geniuses; perhaps the only critic in English who deserves that epithet is Samuel Johnson".[7] F. R. Leavis agreed and, on Johnson's criticism, said, "When we read him we know, beyond question, that we have here a powerful and distinguished mind operating at first hand upon literature. This, we can say with emphatic conviction, really is criticism".[236] Edmund Wilson claimed that "The Lives of the Poets and the prefaces and commentary on Shakespeare are among the most brilliant and the most acute documents in the whole range of English criticism".[7]

The critic Harold Bloom placed Johnson's work firmly within the Western canon, describing him as "unmatched by any critic in any nation before or after him...Bate in the finest insight on Johnson I know, emphasised that no other writer is so obsessed by the realisation that the mind is an activity, one that will turn to destructiveness of the self or of others unless it is directed to labour."[237] It is no wonder that his philosophical insistence that the language within literature must be examined became a prevailing mode of literary theory during the mid-20th century.[238]

Bust of Johnson by Joseph Nollekens, 1777.

Bust of Johnson by Joseph Nollekens, 1777.There are many societies formed around and dedicated to the study and enjoyment of Samuel Johnson's life and works. On the bicentennial of Johnson's death in 1984, Oxford University held a week-long conference featuring 50 papers, and the Arts Council of Great Britain held an exhibit of "Johnsonian portraits and other memorabilia". The London Times and Punch produced parodies of Johnson's style for the occasion.[239] In 1999, the BBC Four television channel started the Samuel Johnson Prize, an award for non-fiction.[240]

Half of Johnson's surviving correspondence, together with some of his manuscripts, editions of his books, paintings and other items associated with him are in the Donald and Mary Hyde Collection of Dr. Samuel Johnson, housed at Houghton Library at Harvard University since 2003. Materials in the collection may be accessed through the Houghton Reading Room. The collection includes drafts of his Plan for a Dictionary, documents associated with Hester Thrale Piozzi and James Boswell (including corrected proofs of his Life of Johnson) and a teapot owned by Johnson.[241]

A Royal Society of Arts blue plaque, unveiled in 1876, commemorates his Gough Square house.[242]

On 18 September 2017 Google commemorated Johnson's 308th birthday with a Google Doodle.[243][244]

Major works

Essays, pamphlets, periodicals, sermons1732–33 Birmingham Journal

1747 Plan for a Dictionary of the English Language

1750–52 The Rambler

1753–54 The Adventurer

1756 Universal Visiter

1756- The Literary Magazine, or Universal Review

1758–60 The Idler

1770 The False Alarm

1771 Thoughts on the Late Transactions Respecting Falkland's Islands

1774 The Patriot

1775 A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland

Taxation No Tyranny

1781 The Beauties of Johnson

Poetry1728 Messiah, a translation into Latin of Alexander Pope's Messiah

1738 London

1747 Prologue at the Opening of the Theatre in Drury Lane

1749 The Vanity of Human Wishes

Irene, a Tragedy

Biographies, criticism1735 A Voyage to Abyssinia, by Jerome Lobo, translated from the French

1744 Life of Mr Richard Savage

1745 Miscellaneous Observations on the Tragedy of Macbeth

1756 "Life of Browne" in Thomas Browne's Christian Morals

Proposals for Printing, by Subscription, the Dramatick Works of William Shakespeare

1765 Preface to the Plays of William Shakespeare

The Plays of William Shakespeare

1779–81 Lives of the Poets

Dictionary1755 Preface to a Dictionary of the English Language

A Dictionary of the English Language

Novellas1759 The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia

Notes1. Johnson was 180 cm (5 feet 11 inches) tall when the average height of an Englishman was 165 cm (5 feet 5 inches).[195]

2. Bate (1977) comments that Johnson's standard of effort was very high, so high that Johnson said he had never known a man to study hard.[33]

References

Specific1. Meyers 2008, p. 2

2. Rogers, Pat (2006). "Johnson, Samuel (1709–1784)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14918. Retrieved 25 August 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

3. Bate 1977, p. xix

4. Bate 1977, p. 240

5. Lynch 2003, p. 1

6. Murray 1979 and Stern, Burza & Robertson 2005

7. Winters 1943, p. 240

8. Bate 1977, p. 5

9. Lane 1975, pp. 15–16

10. Watkins 1960, p. 25

11. Lane 1975, p. 16

12. Bate 1977, pp. 5–6

13. Lane 1975, pp. 16–17

14. Lane 1975, p. 18

15. Lane 1975, pp. 19–20

16. Lane 1975, pp. 20–21

17. Boswell 1986, p. 38

18. Bate 1977, pp. 18–19

19. Bate 1977, p. 21

20. Lane 1975, pp. 25–26

21. Lane 1975, p. 26

22. DeMaria 1994, pp. 5–6

23. Bate 1977, p. 23, 31

24. Lane 1975, p. 29

25. Wain 1974, p. 32

26. Lane 1975, p. 30

27. Lane 1975, p. 33

28. Bate 1977, p. 61

29. Lane 1975, p. 34

30. Bate 1977, p. 87

31. Lane 1975, p. 39

32. Bate 1977, p. 88

33. Bate 1977, pp. 90–100.

34. Boswell 1986, pp. 91–92

35. Bate 1977, p. 92

36. Bate 1977, pp. 93–94

37. Bate 1977, pp. 106–107

38. Lane 1975, pp. 128–129

39. Bate 1955, p. 36

40. Bate 1977, p. 99

41. Bate 1977, p. 127

42. Wiltshire 1991, p. 24

43. Bate 1977, p. 129

44. Boswell 1986, pp. 130–131

45. Hopewell 1950, p. 53

46. Bate 1977, pp. 131–132

47. Bate 1977, p. 134

48. Boswell 1986, pp. 137–138

49. Bate 1977, p. 138

50. Boswell 1986, pp. 140–141

51. Bate 1977, p. 144

52. Bate 1977, p. 143

53. Boswell 1969, p. 88

54. Bate 1977, p. 145

55. Bate 1977, p. 147

56. Wain 1974, p. 65

57. Bate 1977, p. 146

58. Bate 1977, pp. 153–154

59. Bate 1977, p. 154

60. Bate 1977, p. 153

61. Bate 1977, p. 156

62. Bate 1977, pp. 164–165

63. Boswell 1986, pp. 168–169

64. Wain 1974, p. 81; Bate 1977, p. 169

65. Boswell 1986, pp. 169–170

66. Bate 1955, p. 14

67. Lynch 2003, p. 5

68. Bate 1977, p. 172

69. Bate 1955, p. 18

70. Bate 1977, p. 182

71. Watkins 1960, pp. 25–26

72. Watkins 1960, p. 51

73. Bate 1977, pp. 178–179

74. Bate 1977, pp. 180–181

75. Hitchings 2005, p. 54

76. Winchester 2003, p. 33

77. Lynch 2003, p. 2

78. Lynch 2003, p. 4

79. Lane 1975, p. 109

80. Hawkins 1787, p. 175

81. Lane 1975, p. 110

82. Lane 1975, pp. 117–118

83. Lane 1975, p. 118

84. Lane 1975, p. 121

85. Bate 1977, p. 257

86. Bate 1977, pp. 256, 318

87. "Currency Converter", The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, retrieved 24 July 2008

88. Lynch 2003, pp. 8–11

89. Bate 1955, p. 25

90. Lane 1975, p. 113

91. Lane 1975, p. 115

92. Lane 1975, p. 116

93. Lynn 1997, p. 241

94. Boswell 1986, p. 67

95. Bate 1955, p. 22

96. Weinbrot 1997, p. 49

97. Bate 1977, p. 281

98. Lane 1975, pp. 113–114

99. Lane 1975, p. 114

100. Bate 1955, p. 17

101. Bate 1977, pp. 272–273

102. Bate 1977, pp. 273–275

103. Bate 1977, p. 321

104. Bate 1977, p. 324

105. Murray 1979, p. 1611

106. Bate 1977, pp. 322–323

107. Martin 2008, p. 319

108. Bate 1977, p. 328

109. Bate 1977, p. 329

110. Clarke 2000, pp. 221–222

111. Clarke 2000, pp. 223–224

112. Bate 1977, pp. 325–326

113. Bate 1977, p. 330

114. Bate 1977, p. 332

115. Bate 1977, p. 334

116. Bate 1977, pp. 337–338

117. Bate 1977, p. 337

118. Bate 1977, p. 391

119. Bate 1977, p. 356

120. Boswell 1986, pp. 354–356

121. Bate 1977, p. 360

122. Bate 1977, p. 366

123. Boswell 1986, p. 135

124. Bate 1977, p. 393

125. Wain 1974, p. 262

126. Keymer 1999, p. 186

127. Bate 1977, p. 395

128. Bate 1977, p. 397

129. Wain 1974, p. 194

130. Bate 1977, p. 396

131. Boswell 1986, p. 133

132. Boswell 1986, p. 134

133. Yung 1984, p. 14

134. Bate 1977, p. 463

135. Bate 1977, p. 471

136. Johnson 1970, pp. 104–105

137. Wain 1974, p. 331

138. Bate 1977, pp. 468–469

139. Bate 1977, pp. 443–445

140. Boswell 1986, p. 182

141. Griffin 2005, p. 21

142. Bate 1977, p. 446

143. Johnson, Samuel, TAXATION NO TYRANNY; An answer to the resolutions and address of the American congress (1775)

144. Ammerman 1974, p. 13

145. DeMaria 1994, pp. 252–256

146. Griffin 2005, p. 15

147. Boswell 1986, p. 273

148. Bate 1977, p. 525

149. Bate 1977, p. 526

150. Bate 1977, p. 527

151. Clingham 1997, p. 161

152. Bate 1977, pp. 546–547

153. Bate 1977, pp. 557, 561

154. Bate 1977, p. 562

155. Rogers, Pat (1996), The Samuel Johnson Encyclopedia, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-29411-2

156. Martin 2008, pp. 501–502

157. Bate 1977, p. 566

158. Bate 1977, p. 569

159. Boswell 1986, p. 284

160. Bate 1977, p. 570

161. Bate 1977, p. 575

162. Wiltshire 1991, p. 51

163. Watkins 1960, p. 71

164. Watkins 1960, pp. 71–72

165. Watkins 1960, p. 72

166. Watkins 1960, p. 73

167. Watkins 1960, p. 74

168. Watkins 1960, pp. 76–77

169. Watkins 1960, p. 78

170. Boswell 1986, p. 341

171. Watkins 1960, p. 79

172. Bate 1977, p. 599

173. Hill 1897, p. 160 (Vol. 2)

174. Boswell 1986, pp. 341–342

175. Needham 1982, pp. 95–96

176. Greene 1989, p. 27

177. Greene 1989, pp. 28–30

178. Greene 1989, p. 39

179. Greene 1989, pp. 31, 34

180. Greene 1989, p. 35

181. Greene 1989, p. 37

182. Greene 1989, p. 38

183. Greene 1989, pp. 62–64

184. Greene 1989, p. 65

185. Greene 1989, p. 67

186. Greene 1989, p. 85

187. Greene 1989, p. 134

188. Greene 1989, pp. 134–135

189. Greene 1989, p. 140

190. Greene 1989, p. 141

191. Greene 1989, p. 142

192. Needham 1982, p. 134

193. Greene 1989, p. 143

194. Boswell 1986, p. 122

195. Meyers 2008, p. 29

196. Bate 1955, p. 16 quoting from Boswell

197. Hill 1897, p. 423 (Vol. 2)

198. Bate 1955, pp. 15–16

199. Bate 1977, p. 316

200. Bate 1977, p. 297

201. Greene 1989, p. 87

202. Greene 1989, p. 88

203. Bate 1977, p. 537

204. Boswell 1986, p. 200

205. Skargon 1999

206. Boswell 1986, p. 294

207. Greene 2000, p. xxi

208. Boswell 1986, p. 365

209. Rogers 1995, p. 192

210. Piozzi 1951, p. 165

211. Bate 1955, p. 7

212. Bate 1977, p. 116

213. Bate 1977, p. 117

214. Lane 1975, p. 103

215. Pittock 2004, p. 159

216. Stern, Burza & Robertson 2005

217. Pearce 1994, p. 396

218. Murray 1979, p. 1610

219. Hibbert 1971, p. 203

220. Hibbert 1971, p. 202

221. McHenry 1967, pp. 152–168 and Wiltshire 1991, p. 29

222. Shapiro 1978, p. 361

223. Pearce 1994, p. 398

224. "Notes and Queries – Oxford Academic" (PDF). OUP Academic.

225. Lynn 1997, p. 240

226. Lynn 1997, pp. 240–241

227. Hill 1897, p. 335 (Vol. 2)

228. Bloom 1998, p. 75

229. Davis 1961, p. vii

230. Hill 1897, p. 355

231. Clarke 2000, pp. 4–5

232. Boswell 1986, p. 7

233. Lynn 1997, p. 245

234. Grundy 1997, pp. 199–200

235. Arnold 1972, p. 351

236. Wilson 1950, p. 244

237. Bloom 1995, pp. 183, 200

238. Greene 1989, p. 139

239. Greene 1989, pp. 174–175

240. Samuel Johnson Prize 2008, BBC, retrieved 25 August2008

241. The Donald and Mary Hyde Collection of Dr. Samuel Johnson and Early Modern Books and Manuscripts, Harvard College Library, archived from the original on 24 December 2009, retrieved 10 January 2010

242. "Johnson, Dr Samuel (1709–1784)". English Heritage. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

243. "Samuel Johnson's 308th Birthday". 18 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

244. Cole, Brendan (18 September 2017). "Google marks birthday of Samuel Johnson, pioneer of the 1st 'search tool' the dictionary". International Business Times. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

General• Ammerman, David (1974), In the Common Cause: American Response to the Coercive Acts of 1774, New York: Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-00787-9.

• Arnold, Matthew (1972), Ricks, Christopher (ed.), Selected Criticism of Matthew Arnold, New York: New American Library, OCLC 6338231

• Bate, Walter Jackson (1977), Samuel Johnson, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, ISBN 978-0-15-179260-3.

• Bate, Walter Jackson (1955), The Achievement of Samuel Johnson, Oxford: Oxford University Press, OCLC 355413.

• Bloom, Harold (1998), "Hester Thrale Piozzi 1741–1821", in Bloom, Harold (ed.), Women Memoirists Vol. II, Philadelphia: Chelsea House, pp. 74–76, ISBN 978-0-7910-4655-5.

• Bloom, Harold (1995), The Western Canon, London: Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-64813-1.

• Boswell, James (1969), Waingrow, Marshall (ed.), Correspondence and Other Papers of James Boswell Relating to the Making of the Life of Johnson, New York: McGraw-Hill, OCLC 59269.

• Boswell, James (1986), Hibbert, Christopher (ed.), The Life of Samuel Johnson, New York: Penguin Classics, ISBN 978-0-14-043116-2.

• Clarke, Norma (2000), Dr Johnson's Women, London: Hambledon, ISBN 978-1-85285-254-2.

• Clingham, Greg (1997), "Life and literature in the Lives", in Clingham, Greg (ed.), The Cambridge companion to Samuel Johnson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 161–191, ISBN 978-0-521-55625-5

• Davis, Bertram (1961), "Introduction", in Davis, Bertram (ed.), The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL. D, New York: Macmillan Company, pp. vii–xxx, OCLC 739445.

• DeMaria, Robert, Jr. (1994), The Life of Samuel Johnson, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-55786-664-6.

• Greene, Donald (1989), Samuel Johnson: Updated Edition, Boston: Twayne Publishers, ISBN 978-0-8057-6962-3.

• Greene, Donald (2000), "Introduction", in Greene, Donald (ed.), Political Writings, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, ISBN 978-0-86597-275-9.

• Griffin, Dustin (2005), Patriotism and Poetry in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-00959-1.

• Grundy, Isobel (1997), "Jane Austen and literary traditions", in Copeland, Edward; McMaster, Juliet (eds.), The Cambridge companion to Jane Austen, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 189–210, ISBN 978-0-521-49867-8.

• Hawkins, John (1787), Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D, London: J. Buckland, OCLC 173965.

• Hibbert, Christopher (1971), The Personal History of Samuel Johnson, New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 978-0-06-011879-2.

• Hitchings, Henry (2005), Dr Johnson's Dictionary: The Extraordinary Story of the Book that Defined the World, London: John Murray, ISBN 978-0-7195-6631-8.

• Hill, G. Birkbeck, ed. (1897), Johnsonian Miscellanies, London: Oxford Clarendon Press, OCLC 61906024.

• Hopewell, Sydney (1950), The Book of Bosworth School, 1320–1920, Leicester: W. Thornley & Son, OCLC 6808364.

• Johnson, Samuel (1970), Chapman, R. W. (ed.), Johnson's Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland and Boswell's Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-281072-4.

• Keymer, Thomas (1999), "Johnson, Madness, and Smart", in Hawes, Clement (ed.), Christopher Smart and the Enlightenment, New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-21369-5.

• Lane, Margaret (1975), Samuel Johnson & his World, New York: Harper & Row Publishers, ISBN 978-0-06-012496-0.

• Lynch, Jack (2003), "Introduction to this Edition", in Lynch, Jack (ed.), Samuel Johnson's Dictionary, New York: Walker & Co, pp. 1–21, ISBN 978-0-8027-1421-3.

• Lynn, Steven (1997), "Johnson's critical reception", in Clingham, Greg (ed.), Cambridge Companion to Samuel Johnson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55625-5

• Martin, Peter (2008), Samuel Johnson:A Biography, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, ISBN 978-0-674-03160-9.

• McHenry, LC Jr (April 1967), "Samuel Johnson's tics and gesticulations", Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 22(2): 152–168, doi:10.1093/jhmas/XXII.2.152, PMID 5341871

• Meyers, J (2008), Samuel Johnson: The Struggle, Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group, ISBN 978-0-465-04571-6

• Murray, TJ (16 June 1979), "Dr Samuel Johnson's movement disorder", British Medical Journal, 1 (6178), pp. 1610–1614, doi:10.1136/bmj.1.6178.1610, PMC 1599158, PMID 380753.

• Needham, John (1982), The Completest Mode, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-85224-387-9.

• Pearce, JMS (July 1994), "Doctor Samuel Johnson: 'the Great Convulsionary' a victim of Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome", Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 87 (7): 396–399, PMC 1294650, PMID 8046726.

• Piozzi, Hester (1951), Balderson, Katharine (ed.), Thraliana: The Diary of Mrs. Hester Lynch Thrale (Later Mrs. Piozzi) 1776–1809, Oxford: Clarendon, OCLC 359617.

• Pittock, Murray (2004), "Johnson, Boswell, and their circle", in Keymer, Thomas; Mee, Jon (eds.), The Cambridge companion to English literature from 1740 to 1830, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 157–172, ISBN 978-0-521-00757-3.

• Rogers, Pat (1995), Johnson and Boswell: The Transit of Caledonia, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-818259-7.

• Shapiro, Arthur K (1978), Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, New York: Raven Press, ISBN 978-0-89004-057-7.

• Skargon, Yvonne (1999), The Importance of Being Oscar: Lily and Hodge and Dr. Johnson, London: Primrose Academy, OCLC 56542613.

• Stern, JS; Burza, S; Robertson, MM (January 2005), "Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome and its impact in the UK", Postgrad Med J, 81 (951): 12–19, doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.023614, PMC 1743178, PMID 15640424, It is now widely accepted that Dr Samuel Johnson had Tourette's syndrome.

• Wain, John (1974), Samuel Johnson, New York: Viking Press, OCLC 40318001.

• Watkins, WBC (1960), Perilous Balance: The Tragic Genius of Swift, Johnson, and Sterne, Cambridge, MA: Walker-deBerry, Inc., OCLC 40318001.

• Weinbrot, Howard D. (1997), "Johnson's Poetry", in Clingham, Greg (ed.), Cambridge Companion to Samuel Johnson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55625-5.

• Wilson, Edmund (1950), "Reexamining Dr. Johnson", in Wilson, Edmund (ed.), Classics and Commercials, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, OCLC 185571431.

• Wiltshire, John (1991), Samuel Johnson in the Medical World, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-38326-4.

• Winchester, Simon (2003), The Meaning of Everything, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517500-4.

• Winters, Yvor (1943), The Anatomy of Nonsense, Norfolk, Conn.: New Directions, OCLC 191540.

• Yung, Kai Kin (1984), Samuel Johnson, 1709–84, London: Herbert Press, ISBN 978-0-906969-45-8.

Further reading[edit]

• Broadley, A. M. (1909). Doctor Johnson and Mrs Thrale : Including Mrs Thrale's unpublished Journal of the Welsh Tour Made in 1774 and Much Hitherto Unpublished Correspondence of the Streatham Coterie. London: John Lane The Bodley Head.

• Bate, W. Jackson (1998). Samuel Johnson. A Biography. Berkeley: Conterpoint. ISBN 978-1-58243-524-4.

• Fine, LG (May–June 2006), "Samuel Johnson's illnesses", J Nephrol, 19 (Suppl 10): S110–114, PMID 16874722.

• Gopnik, Adam (8 December 2008), "The Critics: A Critic at Large: Man of Fetters: Dr. Johnson and Mrs. Thrale", The New Yorker, 84 (40): 90–96, retrieved 9 July 2011.

• Johnson, Samuel (1952), Chapman, R. W. (ed.), Letters, Oxford: Clarendon, ISBN 0-19-818538-3.

• Johnson, Samuel (1968), Bate, W. Jackson (ed.), Selected Essays from the Rambler, Adventurer, and Idler, New Haven - London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-00016-0.

• Johnson, Samuel (2000), Greene, Donald (ed.), Major Works, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-284042-8.

• Johnston, Freya, "I'm Coming, My Tetsie!" (review of Samuel Johnson, edited by David Womersley, Oxford, 2018, ISBN 978 0 19 960951 2, 1,344 pp.), London Review of Books, vol. 41, no. 9 (9 May 2019), pp. 17–19. ""His attacks on [the pursuit of originality in the writing of literature] were born of the conviction that literature ought to deal in universal truths; that human nature was fundamentally the same in every time and every place; and that, accordingly (as he put it in the 'Life of Dryden'), 'whatever can happen to man has happened so often that little remains for fancy or invention.'" (p. 19.)

• Kammer, Thomas (2007), "Mozart in the Neurological Department: Who has the Tic?", in Bogousslavsky, Julien; Hennerici, M (eds.), Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists, Part 2, Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience, 22, Basel: Karger, pp. 184–92, doi:10.1159/000102880, ISBN 978-3-8055-8265-0, PMID 17495512.

• Leavis, FR (1944), "Johnson as Critic", Scrutiny, 12: 187–204.

• Murray, TJ (July–August 2003), "Samuel Johnson: his ills, his pills and his physician friends", Clin Med, 3 (4): 368–72, doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.3-4-368, PMC 5351955, PMID 12938754.

• Sacks, Oliver (19–26 December 1992), "Tourette's syndrome and creativity", British Medical Journal, 305 (6868): 1515–1516, doi:10.1136/bmj.305.6868.1515, PMC 1884721, PMID 1286364, ... the case for Samuel Johnson having the syndrome, though [...] circumstantial, is extremely strong and, to my mind, entirely convincing.

• Stephen, Leslie (1898), "Johnsoniana", Studies of a Biographer, 1, London: Duckworth and Co., pp. 105–146

• Uglow, Jenny, "Big Talkers" (review of Leo Damrosch, The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age, Yale University Press, 473 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 9 (23 May 2019), pp. 26–28.

External links• Samuel Johnson at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

• Samuel Johnson and Hodge his Cat

• Works by Samuel Johnson at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Samuel Johnson at Internet Archive

• Works by or about Dr Johnson at Internet Archive

• Works by Samuel Johnson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• Full text of Johnson's essays arranged chronologically

• BBC Radio 4 audio programs:In Our Time and Great Lives

• A Monument More Durable Than Brass: The Donald and Mary Hyde Collection of Dr. Samuel Johnson – online exhibition from Houghton Library, Harvard University

• The Samuel Johnson Sound Bite Page, comprehensive collection of quotations

• Samuel Johnson at the National Portrait Gallery, London

• Life of Johnson at Project Gutenberg by James Boswell, abridged by Charles Grosvenor Osgood in 1917 "... omitt[ing] most of Boswell's criticisms, comments and notes, all of Johnson's opinions in legal cases, most of the letters, ..."