Kalimpong was situated 4,000 feet above sea level. Here the air was thinner and clearer than in the plains, and the sky a deeper, darker blue. On most days of the year except during the rainy season one could see, high above the foothills to the north-west, the dazzlingly white shape of Mount Kanchenjunga, the second highest peak in the Himalayan Range. I had lived in Kalimpong for fourteen years, ever since the memorable day when Kashyap-ji had left me there with the parting injunction to stay and work for the good of Buddhism. During that time I had become an accepted part of the cultural and religious life of the cosmopolitan little town. Now I had come to say goodbye. I had come to say goodbye to my friends and teachers, some of whom I might never see again. I had come to say goodbye to my hillside hermitage, with its row of Kashmir cypresses, its flowerbeds and terraces, its hundred orange trees, its bamboo grove, and its solitary mango tree. I had come to say goodbye to the shrine room where I had meditated for so many hours, to the study-cum-bedroom where I had started writing the first volume of my memoirs, and to the veranda up and down which, during the rainy season, I had paced deep in reflection. I had come to say goodbye to Kalimpong goodbye to Mount Kanchenjunga and its snows.

But though I had come to say goodbye, my 'homecoming' was in many ways a joyful one. The first to welcome me back to the Triyana Vardhana Vihara, or Monastery Where the Three Ways Flourish, were Hilla Petit and Maurice Freedman, who had been staying there for the last few days. Hilla was the elderly Parsee friend with whom Terry and I had had lunch in Bombay, and diminutive, big-headed Maurice was her long-term house-guest. I had first met the oddly assorted pair in Gangtok, when they were holidaying with our common friend 'Apa Saheb Pant', the then Political Officer of Sikkim, and in later years I had more than once stayed with them at their comfortable Bombay flat. Both were keen followers of J. Krishnamurti, and soon Maurice and I were deep in one of our usual rather inconclusive discussions as to whether Truth was really a 'pathless land' that could be approached only by way of choiceless awareness. Not that I had much time for such discussions that morning -- at least not as much as Maurice probably would have liked. There were letters to be opened, other friends to be seen.

One of the first letters to be opened was from the English Sangha Trust. It was dated 1 November and was signed by George Goulstone in his capacity as one of the Directors of the Trust. After assuring me in the most fulsome terms of the Trust's deep appreciation of my services to the Dharma in England, he went on to inform me that in the opinion of the Trust and my fellow Order members my long absences from the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara, together with what he described as my extra-mural activities, were not in accordance with the Theravãda's high standards of discipline and ethics. Moreover, I had not comported myself in a manner fitting the religious office that I held in the Order. The Trust had therefore decided to seek elsewhere for an incumbent of the Vihara. As my work in India was so dear to my heart, the letter continued blandly, I might think that my allotted task was to remain and serve Buddhism in the East. Should I, on careful reflection, consider that my work lay in the East, this would be acceptable as a reasonable ground for my resignation, and notification to this effect would be made to the Buddhist Authorities in the West. Should I not feel disposed to take this step, the trustees would feel regretfully obliged to withdraw their support from me. In so doing, they felt sure of having the agreement of the Sangha authorities in England.

'Do you know what this means?' I asked Terry, when I had finished reading the letter. 'It means a new Buddhist Movement!' The words sprang spontaneously from my lips. It was as if the Trust's letter, coming as it did like a flash of lightning, had suddenly revealed possibilities that had hitherto been shrouded in darkness or perceived only dimly. Though I had long felt that the Buddhist movement in Britain might need a fresh impetus, and had even discussed with the Three Musketeers and Viriya the feasibility of my giving lectures and holding classes outside the orbit of the Hampstead Vihara and the Buddhist Society, I had certainly never considered the possibility of my taking a step so radical as that of starting a new Buddhist movement, whether in Britain or anywhere else. But I now saw that a new Buddhist movement was what was really needed, and that the Trust's letter had opened the way to my starting it. The movement I was to found some months later may have been born in London, but it was conceived there in Kalimpong on 24 November 1966, at the moment when I addressed to Terry those six fateful words.

Yet clearly as I saw that there would be a new Buddhist movement in Britain, I had no idea what form that movement might take. Nor did I need to have any idea. My immediate concern was with the reasons alleged by the Trust for their wanting to replace me as incumbent of the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara. A number of points struck me in this connection. There was the claim that my fellow Order members (who were they?) shared the Trust's opinion that my conduct had been unethical. What evidence was there that they really did share that opinion? According to the Vinaya or Monastic Code a monk could not be charged with an offence in absentia, much less charged, tried, and sentenced as the Trust was actually doing in my case. He had to be charged face-to-face at a formal assembly of the monks. Either the Trust's claim was false or my fellow monks had acted in direct contravention of the Vinaya. In any case, the Trust's charges against me were couched in very general terms. What did they mean by extramural activities, and in what way had I failed to comport myself in a fitting manner? As for my long absences from the Vihara, there had been only one such long absence, when Terry and I were away travelling in Italy and Greece. Before we left Walshe and others had assured me that I deserved a holiday, though a 'holiday' was not quite what I had in mind. Moreover, the trustees seemed to have forgotten that in accepting their invitation to visit England I had stipulated that my mornings should be free for literary work and that, when this proved impracticable, far from minding I had gladly accepted the new situation. Finally, the Trust had overlooked the fact that on the eve of my departure from England I had promised my friends and supporters that I would be returning in four months time. In suggesting I might on reflection consider that my work lay in the East they were proposing not only that I should break my word but that I should cover up the fact that I was breaking it with the downright lie that I had changed my mind. So much for the Theravãda's high standards of discipline and ethics!

Such were the points that occurred to me as I read the Trust's letter. They were all points which would have to be made, I thought, when I replied to Goulstone. But much as I felt like replying immediately, I decided not to do so. Better to wait a few days, and reply when I had had time to think things over and consult with Terry. Meanwhile, there were friends to be visited. Having finished reading my mail I took the rough track up the hillside that led from the Lower to the Upper Cart Road and thence, eventually, to Chakhung House. The modest bungalow so named was the residence of the Kazi Lhendup Dorje-Khangsarpa of Chakhung, a leading politician of Sikkim, and his formidable European wife. I had known them since 1957, the year of their marriage, rather late in life, in New Delhi. The Kazini had come bringing from a common friend at the UK High Commission a letter of introduction in which he asked me to help her should she meet with any difficulties in Kalimpong. She did meet with difficulties and I did help her, and this had led to the development of a friendship between the Kazi and Kazini and me. Though her husband was a leading player in the politics of the tiny Himalayan principality (he became Chief Minister some years later), the Kazini herself was not openly involved in them, but instead pulled strings behind the scenes, maintained contact with a variety of intelligence agencies, and was an unfailing source of information and gossip. During my absence they had kept an eye on the Vihara for me, making sure that Lobsang Norbu and Thubden kept the place clean and tidy and aired my books from time to time, especially during the rainy season, when they were apt to become mildewed. Both were in when I called, and we had a happy meeting. I gave them their presents (the Kazinis was a political biography she had wanted), heard all the news, and stayed for lunch, and it was not until late afternoon that Kazi left for a political meeting in Gangtok and I for the Vihara and further inconclusive discussion with Maurice. That night I slept in the shrine room as Hilla was occupying my own quarters. Thus passed my first day back in Kalimpong.

Hilla and Maurice left after breakfast taking with them for posting in Bombay the letters I had written first thing that morning. I did not want to post them in Kalimpong, since they would then be read by the local branch of the Central Intelligence Bureau, as were all letters to and from foreigners living in the town, and might therefore take a long time to reach their destination. Besides writing to Gerald Yorke and Jack Ireland I sent to the New Statesman an advertisement to the effect that I would be returning to England as planned and continuing my lectures on Buddhism. Hilla and Maurice had no sooner left than I received a visit from Durga and Nardeo, two young Nepali friends who had once studied English with me. Durga was particularly close tome, and had more than once stayed at the Vihara while I was away on one of my preaching tours. After I had talked for a while with the two young men, Terry and I went to see Dhardo Rimpoche, on the way stopping first at Chakhung House (Terry did not take to the Kazini, nor she to him) and then at the Frontier Office where I was given a cordial reception by Moitra, the Frontier Inspector, and his staff and where we obtained the application forms for a one-month extension of Terry's Inner Line permit. Dhardo Rimpoche was an eminent tulku or incarnate lama who had lived in Kalimpong since 1950. In 1954 he had started the Indo-Tibet Buddhist Cultural Institute, under whose auspices he was soon running an orphanage and school for Tibetan refugee children. I was associated with these projects from the beginning and this had led to the development of a friendship based on mutual respect and liking and on the fact that we were both working, in our different ways, for the advancement of Buddhism. Our friendship was deepened in 1956, the year of the 2,500th Buddha Jayanti, when with fifty-odd other Eminent Buddhists from the Border Areas, as we were styled, the Rimpoche and I went on pilgrimage to the principal Buddhist holy places as guests of the Government of India. During those nine or ten days we saw much more of each other than usual. Indeed at times we were in each others company uninterruptedly for days together. I do not know what kind of impression I made on the Rimpoche during this period of closer contact, but the impression he made on me certainly served to reinforce the very positive one I had already formed of him. Besides being always mindful and alert, in his dealings with others fellow pilgrims, Indian officials, and railway staff he was invariably kind, patient, and good-humoured and, in short, exhibited all the qualities of a true tulku. To such an extent was this the case, that I eventually came to revere him as a living Bodhisattva, so that when I felt ready to give formal expression to my acceptance of the Bodhisattva ideal by taking the Bodhisattva ordination it was naturally Dhardo Rimpoche whom I asked to be my preceptor. He had given me the ordination in 1962, thus from a friend becoming a teacher, though without ceasing to be a friend. While I was away he had moved his Institute, together with its orphanage and school, to their new home at the edge of the lower bazaar, and it was to this new home, on the other side of the saddleback on which the town was situated, that Terry and I made our way from the Frontier Office. Dhardo Rimpoche received us with his usual cordiality, and I presented him with the maroon and gold table clock I had bought for him in Zurich. Though he had aged a little, his eyes still sparkled with intelligence and good humour, and I saw that Terry was regarding him with a mixture of curiosity and respect. As was his custom when at home, Dhardo Rimpoche wore only a maroon monastic skirt and a sleeveless Chinese style shirt of orange silk so that his arms were bare. After he and I had talked for a while and Terry had been properly introduced and his background explained, it was agreed that Terry and I should return next day and that my friend should take the Rimpoche's photograph. The following afternoon, therefore, we saw the Institute again, and Terry took photographs of the Rimpoche seated on his elevated Dharma seat, wearing full monastic dress, and with his dorje and bell on the table before him.

A few days later Terry photographed the children of the school, of whom there were a hundred or more of all ages. Many of them were poorly clad, but they all looked healthy and well cared for, and it was evident that their relationship with the Rimpoche was a very happy one. Sherab Nangwa, an elderly Tibetan whom I had ordained as a Theravãdin novice, was present on this occasion, and when Terry and I took Dhardo Rimpoche back to the Vihara for lunch he accompanied us. The weather had been cloudy that morning, but in the afternoon it was bright and sunny, and after lunch the four of us were able to sit out in the garden. Before leaving the Rimpoche performed, in the shrine room, a short ceremony of purification and blessing for the benefit of the Vihara and its occupants, scattering rice and ringing his ritual bell as he did so. In the course of the next few weeks he came to see me three or four times, and I visited him still more frequently, sometimes with Terry, but more often on my own. We spent much of our time together working on the translation of a Tibetan sadhana text entitled The Stream of the Immortality-Conferring Nectar of the Esoteric Oral Tradition of the Lamas Bestowal of the White Tãrã Abhiseka. We had started working on it some years earlier, after the Rimpoche had given me the White Tãrã abhiseka, or consecration as it was sometimes called, and were still working on it at the time of my departure for England. As our medium of communication was Hindi, interspersed with words in Tibetan and English, the task of translation was a difficult one, but we both attached great importance to the work and were determined that it should be completed before I left for England a second time.

Dhardo Rimpoche was not my only Tibetan teacher, nor was he the only one to visit the Vihara after my return. Kachu Rimpoche, who was abbot of Pemayangtse Gompa in Sikkim, also came, accompanied by his nephew and one of his lamas. As always, he arrived unexpectedly, just as Terry and I were finishing breakfast, so that I was all the more glad to see him. He was obviously no less glad to see me. Like Dhardo Rimpoche, he was a monk, besides being a tulku, and like Dhardo Rimpoche he wore the maroon monastic robes, but apart from the fact that both were men of rare spiritual attainments and deep commitment to the Dharma, there the resemblance ended. Dhardo Rimpoche belonged to the dominant Gelug, or 'Virtuous', school of Tibetan Buddhism, founded by the reformer Tsongkhapa at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Kachu Rimpoche, on the other hand, was a follower of the Nyingma, or 'Old Style', school inaugurated more than 600 years earlier by the Indian yogin and wonder-worker Padmasambhava in the course of his historic mission to the Land of Snows. The two incarnate lamas also differed in character and manner, as well as in their way of relating to me. If Dhardo Rimpoche was the more urbane and cultivated, Kachu Rimpoche was the more spontaneous and direct. While Dhardo Rimpoche had always responded positively to my requests and had in- variably answered my questions with patience and good humour, so far as I remember he had never given me any direction or instruction of his own accord. Kachu Rimpoche had habitually done just that, and though not one to stand on ceremony he was always very much the guru. Thus he had urged me to ask the celebrated Jamyang Khyentse Rimpoche, his own guru, for the abhiseka of Mañjughoëa, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom; had given me, as instructed by the Rimpoche, the abhiseka of Padmasambhava, together with that of Amitayus, the Buddha of Infinite Life; had started me on the practice of the four mûla or foundation yogas of the Vajrayãna; and had insisted, as a result of a vision, on our having a multicoloured 'banner of victory' on the roof of the Triyana Vardhana Vihara. But now it was my turn to take the initiative. Kachu Rimpoche having had his photograph taken, at his own request, I asked him if he would mind Terry taking pictures of him demonstrating the eight offering mudras, the eight hand gestures representing the flowers, lights, and other items which, in Tibetan ritual worship, were offered to the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. To this he readily agreed, and the pictures were accordingly taken out in the garden, in the sun, and against the background of a white sheet. Next day he came for lunch, as did Sherab Nangwa. After the meal the three of us sat out in the garden, and the Rimpoche explained certain fundamentals of Vajrayãna meditation, so far as those related to the visualization of the figure of Padmasambhava. On his departure I gave hima large bag of oranges to take with him back to Pemayangtse -- oranges that had been gathered from the Viharas own trees that very morning.

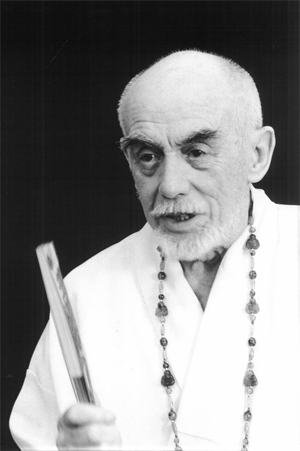

Yogi Chen did not come to see me. He lived as a hermit in a small bungalow at the bottom end of the lower bazaar, never went outside his front door, and rarely received visitors. During my latter years in Kalimpong, however, I had been allowed to visit him from time to time, and this privilege was now extended to include Terry. A short, plump, round-faced man in his middle or late fifties, the yogi had an ebullient manner not usually associated with a hermit, least of all one who spent the greater part of each day engaged in various forms of meditation. Nor was he without his eccentricities. Sometimes he wore the traditional dress of a Chinese scholar, complete with black skullcap, sometimes an anorak and baseball cap. Despite his eccentricities, he possessed a thorough knowledge of the Buddhist scriptures (he had twice read through the entire Chinese Tripitaka), a comprehensive grasp of Buddhist doctrine, and a rich and varied inner life which included in its gamut not only insights and ecstasies of a more spiritual nature but also strange psychic experiences. Over the years I must have asked him hundreds of questions about the Vajrayãna, about Chan, and about Chinese Buddhism in general; and many were the times he had clarified a philosophical doctrine, or explained a meditation practice, in away no one else had been able to do. For this reason I had come to regard Yogi Chen as one of my teachers, though he absolutely refused either to consider himself a guru or to allow others to speak of him as such. But he was always ready to share his knowledge and experience with the few who were allowed to visit him. He certainly shared them very readily with Terry and me, and on one of our visits discoursed to us at length on Vajrayãna sadhana or spiritual practice. He also allowed Terry to take pictures of his thangkas, which for the most part depicted esoteric Tantric divinities of the wrathful kind, many of them in sexual union with their consorts.

Whether Terry and I happened to be on our way to see Dhardo Rimpoche or Yogi Chen, or were walking through the High Street, or investigating the Tibetan pavement stalls at the top end of the Lower Bazaar, we could not go more than a few yards without my bumping into, or being accosted by, someone I knew or who, at least, knew me. I was particularly glad to meet my old protégé Budha Kumar, now a civil engineer in Gangtok after making a romantic runaway marriage, and loyal, devoted Mrs King, a Tamang Buddhist married to a Chinese, with whom I had to have tea, and at whose house I met Durga's pretty young wife Meera, whom I had once taught English and who had not been the brightest of my pupils. People also came to see me at the Vihara. They included Joseph E. Cann ('Uncle Joe'), the prickly, chain-smoking Canadian Buddhist, now in his seventies, who had arrived in Kalimpong shortly after me, and who according to my diary 'talked almost without stopping for about two hours; worried-looking Dawa Tsering, one of the most faithful and helpful of my old students; the plump, teenage Sogyal Rimpoche; monks from the Tharpa Choling Gompa at Tirpai; and the head of the local branch of the Central Intelligence Bureau, one Mr Das Gupta. Terry and I also paid several more visits to Chakhung House. On one occasion the Kazini insisted on giving gruesome details of the Delhi communal riots of 1947,which rather upset Terry, while Uncle Joe, who also happened to be there, was no less negative. Both seemed to enjoy the horrors they were denouncing, my diary comments.

Meetings with my friends and teachers thus occupied much of my time, as to a lesser extent they did Terry's likewise, so that within ten or twelve days of my return to Kalimpong I had seen practically all those who were not out of station, as the phrase went. But precious as these occasions were, and greatly as I appreciated being with my teachers and friends again, the thought of Goulstones' letter, and of what I should say by way of reply, was never far from my mind, especially as other letters were arriving from London as well as from other parts of the little world of British Buddhism. These letters were of a very different kind. From them it was evident that word of the Trust's decision to replace me as incumbent of the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara had somehow leaked out and that members of the Sangha Association had reacted to the news first with incredulity and then with mounting astonishment and indignation. Why did they have to behave in such an underhand manner? wrote one correspondent, Could they not have talked to you while you were here? There was also a sad, affectionate letter from Ruth Walshe, and a personal one from Maurice in which he sought to justify the action the Trust had taken on the grounds that like Caesars wife I had to be above suspicion and that, despite my talents, I was emotionally unbalanced and immature and in need of psychological and spiritual help. Though I had originally intended to reply to Goulstone at length, making the points that had occurred to me when I first read his letter, after several abortive attempts along these lines I realized that trying to rebut charges that had not been made in good faith, and of which in any case I had already been found guilty, was really a waste of time. I therefore wrote him a short letter, but not before I had consulted Dhardo Rimpoche and Yogi Chen (Kachu Rimpoche was consulted later), as well as the Kazi and Kazini. They agreed in thinking that I should return to England as planned, and there continue working for the Dharma, though probably only the Kazini understood the kind of difficulties I would have to face. My letter read, in part, as follows:

Dear Goulstone,

Having considered the contents of your letter dated 1st November, I do not propose to deal with spurious accusations through the medium of correspondence. My main concern at this juncture is to safeguard the Buddhist activities at Hampstead, which the Trust has now placed in an extremely difficult and unfortunate position. The charges you mention are so easily refuted as to suggest the possibility of their having been fabricated with an ulterior motive. Even if the Trust withdraws its support from me, my own allegiance to and responsibility towards the Buddhist movement in England does not permit me to retract promises made or -- more disastrous still -- to abandon Buddhism to those incapable of recognizing the promising nature of the movement which has been built up at the Vihara during the last two years.

Having now lived with your letter for a few days, and having received from various prominent members of our movement letters protesting against the Trust's behaviour and promising support, I am not sufficiently alarmed to curtail my stay here and will return as planned early in the New Year.

Yours sincerely,

Sangharakshita

Once the letter had been sent I realized that the die had indeed been cast and that there would be no turning back, even if I wanted to do so.