Part 2 of 2

In the face of these various policies directed against Buddhism, Buddhist leaders undertook measures to demonstrate their importance to the Japanese nation. In 1896 representatives of a number of sects joined together (for the first time in the history of Japanese Buddhism) to form the Alliance of United Sects for Ethical Standards, proclaiming support for the emperor and calling for the expulsion of the truly foreign religion in Japan, Christianity. Such acts met with the approval of the government, and Buddhist priests were allowed to serve in a newly established system of teaching academies for the promulgation of patriotic principles. With the identification of Shinto and the state, priests certified to teach in these academies (located at Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines) were expected to wear Shinto robes and recite Shinto prayers. Buddhist priests who did not receive certification to teach were prohibited from giving public teachings, performing rites or residing at Buddhist temples. The policy to establish teaching academies was soon abandoned, but the reforms of Buddhism continued.

A further assault on Buddhism took place in 1872, when the Meiji government removed any special status from monkhood. Henceforth, monks had to register in the household registry system and were subject to secular education, taxation and military conscription. Most controversially, the government declared that 'from now on Buddhist clerics will be free to eat meat, marry, grow their hair, and so on'. The new regulations, and especially the regulation permitting marriage, were met with alarm by the hierarchs of many of the Buddhist sects of Japan9 They feared that rescinding the law against clerical marriage would destroy the distinction between monk and layperson, bringing chaos to the state. For centuries Buddhist leaders in Japan had represented the dharma as having the power to protect the Japanese nation, a power that derived from the monks' strict observance of their vows, especially the vow of celibacy. The maintenance of the monastic code therefore provided what they regarded as Buddhism's greatest service, and hence its closest link, to the state. The Meiji government, however, sought to remove the marks that distinguished Buddhist monks from other subjects of the emperor, the most obvious of which were the shaved head, the vegetarian diet and celibacy. Indeed, the new law had been requested by a monk of the Zen sect who wished to put an end to the government's suppression of Buddhism by demonstrating the willingness of Buddhist priests to serve the nation. In response to protests from Buddhist leaders, the government subsequently issued an addendum to the law, stating that although meat eating and marriage were no longer criminal offences, the individual sects were free to regulate these activities as they saw fit. Most sects subsequently issued regulations either condemning or prohibiting marriage for its monks. None the less, it became increasingly common for monks to marry, and today less than one per cent of monks in Japan observe the code of monastic discipline of a fully ordained monk.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, Buddhist intellectuals strove to demonstrate the relevance of Buddhism to the interests of the Japanese nation by promoting a new Buddhism that was fully consistent with Japan's attempts to modernize and expand its realm. Buddhism had been attacked in the early years of the Meiji as a foreign and anachronistic institution, riddled with corruption, a parasite on society and the purveyor of superstition, standing in the way of progress and Japan's entry into the modern world. This New Buddhism was represented as both purely Japanese and purely Buddhist, more Buddhist, in fact, than the other forms of Buddhism in Asia. It was also committed to social welfare, urging education for all, and the foundation of hospitals and charities.

New Buddhism was fully consistent with modern science. And it supported the expansion of the Japanese empire. Indeed, Buddhist leaders were united in their call to restore true Buddhism (that they believed to exist only in Japan) throughout the rest of Asia, beginning with the Sino-Japanese War of 1894- 5 and continuing until the defeat of Japan by the Allies in 1945.10

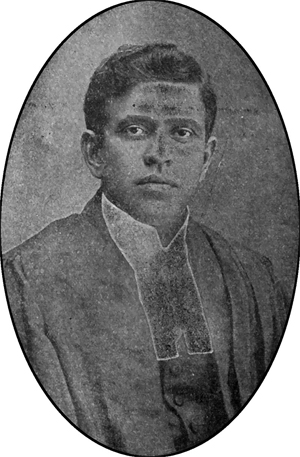

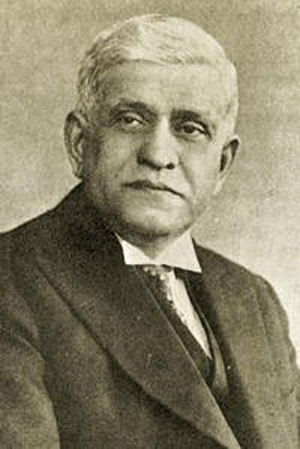

One of the leading figures of the New Buddhism was Shaku Soen (1859-1919). Ordained as a novice of the Rinzai Zen sect at the age of twelve, he studied under the Rinzai master Imakita Kosen (1816- 92), who had served as one of the government-certified teachers during the 1870s. Shaku Soen trained under Imakita at the famous Engakuji monastery in Kamakura, receiving 'dharma transmission', and hence authority to teach, at the age of twenty-four. Seeking to combine both Buddhist training and Western-style education, he attended Keio University, and then travelled to Ceylon to study Pali and live as a Theravada monk. Upon his return, he was chosen by a conference of abbots to be one of the four editors of a book entitled The Essentials of Buddhism -- All Sects. Like many of the leading figures of modern Buddhism, he was devoted to teaching meditation to laypeople, providing instruction both in Tokyo and at his monastery. He was selected to be one of the Japanese representatives to the World's Parliament of Religions in 1893, his address being translated into English by one of his lay disciples, D. T. Suzuki. In his report on the parliament, he described the work of the Japanese delegation:

We invited the attention of the participants, both foreign and Japanese, to the following points at least: that the Japanese are people with abundantly loyal and patriotic spirits; that Buddhism has exercised great influence on Japanese spirituality, and had had influence on successive emperors too; that Buddhism is a universal religion and it closely corresponds to what science and philosophy say today; that we cleared off the prejudice that Mahayana Buddhism was not the true teaching of the Buddha; that Mr Straw, a wealthy merchant in New York, had a conversion ceremony carried on at the congress hall in which he became a Buddhist; that a leading Japanese staying in the United States arranged a Buddhist lecture meeting twice for us in the Exposition building, and so on."

Soen served as a Buddhist chaplain in Manchuria during the Russo- Japanese War of 1904-5. He had become sufficiently well known by that time that Leo Tolstoy sought to enlist his support in condemning the war between their two nations, a request that Soen refused.

Soen had, in a way, entered the lineage of modern Buddhism some years before, when he met Dharmapala during his studies in Ceylon. But Soen's presence in Chicago was an important moment in the history of modern Buddhism, not so much for his address, but for his meeting with Paul Carus, a German immigrant living in Illinois and the proponent of the Religion of Science, something which Carus would see most perfectly embodied in Buddhism. Soen later arranged for D. T. Suzuki to stay with Carus in La Salle, Illinois, a period that was to prove important for Suzuki's representation of Zen, and hence for modern Buddhism.12 According to legend, Zen began when the Buddha silently held up a flower. Only one monk in the audience smiled in recognition, receiving from the Buddha a 'mind-to-mind transmission', allowing him to see into his true nature and become enlightened. This teaching is said to have been passed from teacher to student, from India to China (where it was called Chan, meaning 'meditation') to Japan, where it was called Zen (the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese character Chan). Over the course of his long life after leaving La Salle, Suzuki wrote many words about this tradition that did not rely on words. His books came to play a profound role in the propagation of Zen in the West, especially in intellectual and artistic circles. Indeed, many of the extracts presented in this book are by writers who were inspired by Suzuki. The place of the Beat writers, for example, in the lineage of modern Buddhism, can be traced directly to Suzuki, the disciple of Shaku Soen.

The practice of Zen meditation in the West arrived via different routes. In the first decades of the twentieth century, a Zen priest named Harada Daiun (1871-1961) began giving instruction in Zen meditation to both priests and laypeople in Japan. His meditation retreats became famous for their rigour and for Harada's emphasis on kensho, an experience of enlightenment. Although many in the Zen establishment considered the achievement of kensho to be a rare event, Harada taught that it was within the reach of everyone who received the proper instruction, whether they be ordained priests or ordinary laypeople. Like many New Buddhists, Harada was a strong defender of Japanese imperialism and remained on the far right wing of the Japanese political spectrum after 1945. His successor was Yasutani Hakuun (1885-1973), a Zen priest who worked as a schoolteacher before beginning to practise under Harada in 1925. Harada granted him permission to teach in 1943, and after the war he started a meditation group for laypeople on the northern island of Hokkaido. Despite being a priest of the Soto sect of Zen, he became increasingly critical of the Soto establishment and in 1954 he declared his independence from the sect and founded the Sanbokyodan ('Three Treasures Association'). Yasutani criticized and dispensed with those elements of traditional Zen monastic life that he deemed superfluous, especially the wearing of monastic robes, the performance of liturgies and ceremonial rites, and the study of Buddhist scriptures. His emphasis on a streamlined practice and rapid attainment of kensho was ideally suited to laypeople, and especially to foreigners in Japan who had become interested in Zen through the writings of D. T. Suzuki, but whose knowledge of Japanese was insufficient to allow them to enrol in the traditional Zen training monasteries. Two American disciples of Yasutani, Philip Kapleau (1912- ) and Robert Aitken (1917- ), would become among the first American Zen masters, and Japanese disciples of Yasutani, such as Maezumi Roshi and Eido Roshi, would become prominent Zen teachers. In this way, a relatively marginal Zen teacher in Japan established what would become mainstream Zen practice in America. 13

In the Theravada nations of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia there has been a long tradition of dividing monastic practice into two categories: the vocation of texts and the vocation of meditation. In commentaries dating from as early as the fifth century, a preference was expressed for the former. Strong and able monks were expected to devote themselves to study, with meditation regarded as the vocation of those who were somehow less able, especially those who became monks late in life. It was also widely believed that after the first generations of disciples of the Buddha, it was impossible to achieve nirvana in the human realm. This is not to suggest that meditation was not practised; it remained the vocation of small groups called 'forest monks' who lived in remote areas, but it was not the focus of the majority of monks and monasteries.

A revival of meditation practice began in Burma in the late nineteenth century. Like Sri Lanka, Burma was formerly a British colony and had been under British control since 1885. Without its traditional royal patronage, the monastic community lost much of its state support, yet Buddhism became strongly associated with Burmese national identity, with leadership provided by both monks and laymen during and after the struggle for independence, achieved in 1948. One of the key figures in the resurgence of meditation practice was Mahasi Sayadaw (1904-82). He became a novice monk at the age of twelve, deciding not to return to lay life when he became an adult (as was commonly done in Burma) but to become a fully ordained monk, taking his vows at the age of nineteen. After completing advanced scriptural studies in Mandalay, he returned to a monastery in the countryside to teach. Shortly afterwards he met the famous monk Mingun Jetavan Sayadaw, who was teaching a form of meditation known as vipassana.

Buddhist meditation is traditionally divided into two forms. The first is called samatha, or serenity meditation, and is intended to lead to a deep level of concentration, in which one is able to focus the mind one-pointedly on an object, without distraction. Serenity is generally presented as a prerequisite for the second form of meditation, vipassana or insight meditation. Here, the concentrated mind is used to analyse the constituents of experience in an effort to discover their true nature. Insight into this nature is a form of wisdom which, when deepened, results in enlightenment and liberation from future rebirth. Mingun Sayadaw was teaching a form of meditation that he had learned from a forest monk, based on teachings ascribed to the Buddha in a text called the Discourse on the Establishment of Mindfulness (Satipatthana Sutta).

According to the technique that Mahasi Sayadaw learned from his teacher, the formal practice of serenity is dispensed with, and one begins immediately with the development of insight by focusing attention on the rising and falling of the abdomen that occurs with each inhalation and exhalation of the breath. In 1941 Mahasi began teaching this technique to both monks and laypeople in his native village, located in a region that did not suffer greatly during the Japanese invasion and occupation of Burma. In [947 a wealthy lay disciple of Mahasi donated land for a meditation centre in Rangoon. By this time Mahasi Sayadaw's fame was such that the prime minister of the newly independent Burma, U Nu, invited him to be the resident teacher at this new meditation centre in the capital. Over the next decade, Mahasi established similar centres throughout Burma and in Thailand and Ceylon, providing meditation instruction (in what came to be known as 'the Burmese method', also taught, with some variations, by the Burmese lay teacher U Ba Khin) to hundreds of thousands of Buddhist monks and laypeople in the Theravada countries, and later in Europe and America. 'Insight meditation' would (together with Zen meditation) become a primary practice of modern Buddhism, and Mahasi Sayadaw is honoured in the lineage of modern Buddhism as the teacher who brought it to the world.

Modern Buddhism did not come to Tibet. There were no movements to ordain women, no publication of Buddhist magazines, no formation of lay Buddhist societies, no establishment of orphanages, no liberal critique of Buddhism as contrary to scientific progress, no Tibetan delegates to the World's Parliament of Religions, no efforts by Tibetans to found (or join) world Buddhist organizations. Tibet remained relatively isolated from the forces of modern Buddhism, in part because it never became a European colony. Christian missionaries never became a significant presence, Buddhist monks were not educated in European languages, European educational institutions were not established, the printing press was not introduced. Indeed, because of its relative isolation, many, both in Asia and the West, considered Tibet to be a pure abode of Buddhism, unspoiled by the forces of modernity. There was, however, one Tibetan who might be considered a modern Buddhist. He was the monk Gendun Chopel (Dge 'dun chos 'phel, 1903- 51), who spent the years 1934-46 travelling in rndia and Ceylon, where he encountered many of the constituents of modern Buddhism, writing about them in his travel journals. There one finds scathing criticisms of the avaricious European colonial powers, speculations on

the compatibility of Buddhism and science, and even an assessment of Madame Blavatsky. In describing the pilgrimage site of Bodh Gaya in 1939, he writes:

Then, because of the troubled times, the place [Bodh Gaya] fell into the hands of heretical [i.e. Hindu] yogins. They did many unseemly things such as building a non-Buddhist temple in the midst of the stupas, erecting a statue of Shiva in the temple, and performing blood sacrifices. The novice Dharmapala was not able to bear this. He died as a result of his great efforts to bring lawsuits in order that the Buddhists could once again gain possession [of Bodh Gaya]. Still, despite his efforts in the past and the passage of laws, his noble vision has not yet come to fruition. Therefore, Buddhists from all of our governments must unite and make all possible effort so that this special place of blessings, which is like the heart inside us, will come into the hands of the Buddhists who are its rightful owners.14

Here Gendun Chopel belatedly adds a Tibetan voice in support of the goals of Dharmapala's Maha Bodhi Society, founded almost fifty years earlier. Adopting the stance of a modern Buddhist, he calls on Tibetans to join with Buddhists from around the world in the crusade to return the most sacred Buddhist site to Buddhist control. But he was an exception among Tibetans. He was imprisoned by the Tibetan government shortly after returning to Tibet in 1946 and died in 1951. Tibet was invaded by China in 1950, and after a decade of increasing tensions, the young Dalai Lama escaped to India during a popular uprising against the Chinese army in Lhasa. Since then, he has become an eloquent spokesman for many of the concerns of modern Buddhism, including

the compatibility of Buddhism and science, the rights of women, concern for the environment, and the role of Buddhism in the promotion of world peace.

It is clear from this desultory series of vignettes of modern Buddhist figures from Sri Lanka, China, Thai land, Japan, Burma and Tibet that each of these nations has its own history and its own Buddhism, suggesting that it may be a mistake to speak of something called 'modern Buddhism', at least in the singular. At the same time, there are a remarkable number of links and connections among the figures whose words appear in this anthology. And although it may be misleading to speak of a single form of modern Buddhism in the traditionally Buddhist nations of Asia, the various trends that began at disparate locations throughout the continent of Asia over the past 150 years have made their way, through a variety of conduits, to Europe and America, where they have been combined, sometimes uneasily, and condensed not into a particular variety of Buddhism, such as Burmese Buddhism or Korean Buddhism, but rather something simply called Buddhism. This Buddhism has a number of characteristics, many of which originated not with the Buddha but with Buddhist reformers of the nineteenth century who were themselves responding to the colonial situation.

In 1909, before she found magic and mystery in Tibet, Alexandra David-Neel published a book in Paris entitled Le modernisme Bouddhist et Ie Bouddhisme du Bouddha. She was not contrasting Buddhist modernism and the Buddhism of the Buddha but rather equating them. Like all Buddhist reform movements over the centuries, modern Buddhism has been represented as a return to the teachings of the Buddha, or better, to his ineffable experience beneath the Bodhi tree on that night of the full moon in May. Implicit in this most traditional of claims, however, was a criticism of traditional Buddhism, of the Buddhism of Asia in 1909. The call to return to original Buddhism allowed modern Buddhists like David-Nee! to concede many of the charges made by its critics, whether they were Orientalists, colonial officials, Christian missionaries, or Asian secularists, who found contemporary Buddhists to be benighted idolaters, crushed by centuries of superstition, exploited by an effete and corrupt monastic order. Such charges were made with a remarkable consistency in European accounts of societies as different as Ceylon, Tibet, China, and Japan. Rather than seeking co defend the Buddhism that they knew, many of the leading figures of modern Buddhism sought to accept the claim that Buddhism had suffered an inevitable decline since the master passed into nirvana. The time was ripe to remove the encrustations of the past centuries and return to the essence of Buddhism.

This Buddhism is above all a religion of reason dedicated to bringing an end to suffering. Suffering was often interpreted by modern Buddhists to mean not the sufferings of birth, ageing, sickness and death, but the sufferings caused by poverty and social injustice. The Buddha's ambiguous statements on caste (he did not reject the caste system but regarded caste as irrelevant to success on the path) were selectively read by Victorian readers, both in Europe and in South Asia, to portray him as a crusader against inequality and a social hierarchy based on birth rather than merit. One of the constituents of modern Buddhism is, therefore, the promotion of the social good, whether it be in the form of rebellion against political oppression (especially by colonial powers), of projects on behalf of the poor, or in the more general claim that Buddhism is the religion most compatible with the technological and economic benefits that result from modernization.

Efforts on behalf of the poor were often made in direct response to the criticisms levelled at Buddhist monks by Christian missionaries. With some important exceptions, Buddhist monks had not traditionally been concerned with the needs of laypeople in this life. Their talents (the performance of rituals, the chanting of scriptures) were better directed towards the needs of the future life. Monks were not meant to provide charity to laypeople, their vocation instead was to receive charity from them, serving as a pure 'field of merit' for their donations, thereby causing the donors to accumulate the good karma that would result in a happy rebirth for them and their departed loved ones. These were deemed more important concerns than the vicissitudes of this life, which were caused by not having accumulated such good karma in the past. As a result, and again with some exceptions, Buddhist charitable organizations have been founded by reformist monks or by laypeople, a trend that continues today in 'Engaged Buddhism'.

The Buddhism of the Buddha was also said to be free from the veneration of images. To the extent that reverence was offered to an image of the Buddha, it was a simple expression of thanksgiving for his teachings, given in full recognition that the Buddha had long ago entered into nirvana. This modern portrayal of Buddhist icons was also at odds with traditional practice. In the first centuries of its introduction into China, Buddhism was known as 'the religion of images', suggesting the central importance that images of the Buddha have held, and continue to hold, throughout Buddhist Asia. Although there is no historical evidence of images of the Buddha being made until centuries after h is death, there are a number of images whose sanctity derives from the belief that the Buddha posed for the artists who created them, and these are among the most venerated images in Asia, serving as important actors in the histories of those kings and emperors who possessed them. Relics of the Buddha are believed to be infused with his living presence and thus capable of bestowing all manner of blessings upon those who venerate them. That modern Buddhists (especially in the West) either ignored this most pervasive of Buddhist practices or dismissed it as superstition again demonstrates the importance of the colonial legacy of Christian missionaries (who consistently labelled Buddhists as idolaters) in the formation of modern Buddhism.

The domain in which modern Buddhists most consistently proclaimed the superiority of their religion over Christianity was that of science. The compatibility of Buddhism and science has been asserted by such disparate figures as Dharmapala in Ceylon, T'ai Hsu in China, Shaku Soen in Japan, and more recently by the Dalai Lama. The focus is again on the Buddha himself, who is seen as denying the existence of a creator deity, rejecting a world view in which the universe is controlled by the sacraments of priests, and setting forth instead a rational approach in which the universe operates through the mechanisms of causation. These and other factors make Buddhism, more than any other religion, compatible with modern science and hence able to thrive in the modern age. Elements of traditional cosmology that did not accord with science (such as a flat earth) were generally dismissed as cultural accretions that were incidental to the Buddha's original teaching.Eastern Monachism opened with an unequivocal statement of the historical humanity of Gautama. “About two thousand years before the thunders of Wycliffe were rolled against the mendicant orders of the west, Gotama Budha [sic] commenced his career as a mendicant in the east, and established a religious system that has exercised a mightier influence upon the world than the doctrines of any other uninspired teacher." By opening with a reference to the fourteenth-century reformer John Wycliffe, Hardy immediately introduced two now familiar features of Western interpretation: the origin of Buddhism as a reaction against the priestcraft and ritual of institutionalized religion, and the role of the Buddha as a social reformer.

The body of the work, as the title suggested, compared the Ceylonese sangha (clerical community) to the Roman Catholic clergy and implied that the modern Buddhist teachings are as far removed from the teachings of the Founder, as in his Wesleyan view, the Church of Rome is from the teachings of Jesus. Buddhism, as it is practiced in Ceylon, he wrote, is a degeneration from and ritual elaboration of the Buddha’s original teaching...This historical displacement between the life of the Buddha and the texts of Buddhism was crucial for T. W. Rhys Davids. The great value of Buddhism to him was that the vast collection of its extant sacred texts preserved a record of the evolution of its religious thought from its development out of Brahmanism in the fifth century BCE right through to the present. He first presented this theme, one that would inform his life’s work, in a public lecture in 1877 titled “What Has Buddhism Derived from Christianity?” which Mrs. Rhys Davids chose to publish in the memorial volume of the Journal of the Pāli Text Society following her husband’s death in 1922.

After explaining in detail the extraordinary similarities between the two great religions, he established that, not only did Buddhism derive nothing from Christianity, there could have been very little influence in either direction. The similarities therefore were the result of the working out of a universal principle, “the same laws acting under similar conditions”. His lesson was that

the transformation of Gautama into the Buddha that could be so clearly traced through the texts allowed Christians to see more clearly how Jesus had been transformed into the Christ. In particular, the Buddhist texts showed how a charismatic human being, a great humanist philosopher who had risen up against the ritual, priestcraft, and institutional religion of his time, had over time been deified by his followers. The extraordinary similarities in their lives, the parallel events, strengthened his case. Buddhism was a “religion whose development runs entirely parallel with that of Christianity, every episode, every line of whose history seems almost as if it might have been created for the very purpose of throwing the clearest light on the most difficult and disputed questions of the origins of the European faith”.This was not only the theme of the first lecture, Mrs. Rhys Davids relays, but a passion he retained throughout his life. She recalls that only weeks before his death he encouraged three Japanese students who visited him to follow the path: “Can you trace in the history of your Buddhism,” he asked, “at what time its votaries began to ascribe divine attributes and status to the Buddha? This is worth your investigating.” It was the basis of the Hibbert Lectures and recurs throughout his work.

Both Rhys Davids use the name Gautama (alternately Gotama) very pointedly to emphasize that the hero was a man. The title “Buddha” was for them evidence of precisely the deification process they worked to expose, the process whereby “Jesus, who recalled man from formalism to the worship of God, His Father and Their Father, became the Christ, the only begotten son of God Most High, while Gotama, the Apostle of Self-Control and Wisdom and Love, became the Buddha, the Perfectly Enlightened, Omniscient one, the Saviour of the World.” Buddhism was, to use T. W. Rhys Davids’s expression, “a mirror which allowed Christians to see themselves more clearly.” As a foreign religion its very “otherness” provided the emotional distance, the unfamiliarity, and the lack of attachment necessary for people to be able to see how the process of the deification of a great man and the manufacture of sacred texts operated. The principle could then be applied to reveal how the words of Jesus, his humanist morality, had similarly become obscured and sacralized through the well-intentioned, and thoroughly natural, elaborations of his disciples.It was a call for reform within his own society and offered a solution to the question of the time: what does Christianity mean in an age of science that calls into question “its divine origin and supernatural growth”? His consistent refrain was that Christianity, like any other religion, should be able to stand scientific scrutiny.

-- Defining Modern Buddhism: Mr. and Mrs. Rhys Davids and the Pali Text Society, by Judith Snodgrass

Despite general agreement that

the Buddha had long ago anticipated the discoveries of modern science, modern Buddhists were not unanimous in their views of science. Some saw Buddhism, with its denial of a creator deity and emphasis on causation, to anticipate theories of a mechanistic universe. Others predicted that the East would receive technology from the West and the West would receive spiritual peace from the East, because the West excelled in investigating the external world of matter while the East excelled in investigating the inner world of consciousness. One finds here yet another characteristic of modern Buddhism. It had become a commonplace of European colonial discourse that the West was more advanced than the East because Europeans were extroverted, active and curious about the external world, while Asians were introverted, passive and obsessed with the mystical. It was therefore the task of Europeans to bring Asians into the modern world. In modern Buddhism this apparent shortcoming is transformed into a virtue, with Asia, and especially Buddhists, endowed with a peace, a contentment and an insight that the acquisitive and distracted Western mind sorely needs.

Prior to the development of modern Buddhism, the many forms of Buddhism in Asia had developed regionally, with contacts among various traditions occurring across local borders. The lineage of monastic ordination in the Theravada had been established in Burma by monks from Sri Lanka, spreading from Burma to Thailand. When that lineage became threatened in Sri Lanka as a result of wars, a delegation of monks was invited from Burma around 1070 and later from Siam in 1753 to ordain Sinhalese monks, thereby reviving the lineage in the nation from whence it had come. In the early centuries of Japanese Buddhism, monks would often make the perilous sea voyage to China to retrieve texts and teachings. Tibetans invited Indian Buddhist masters to Tibet and Indian masters would sail to Sumatra to study. Yet, as each national tradition developed, the importance placed on such contacts diminished, and each type of Buddhism developed its own character and its own sense of being the repository of the true teaching. Monks from Sri Lanka regarded monks from East Asia as inauthentic because they did not hold the Theravada ordination. Monks from East Asia or Tibet regarded the Theravada monks as lacking the full dispensation of the Buddha's teachings found in the Mahayana sutras, texts that Theravada monks considered spurious. Yet such characterizations were largely rhetorical, since travel over long distances was difficult and India, the common place of pilgrimage for all Buddhists, had long since lost its own Buddhist tradition.

All of this changed with the advent of modern Buddhism and the modern age, with greater opportunities for foreign travel. As we have seen, Dharmapala's vision was to develop a world Buddhist mission, one which would restore the great pilgrimage places of India to Buddhist control. But this immediately raised the question of what was meant by 'Buddhism'. Dharmapala regarded the Theravada, especially as it was practised in Ceylon, to be the true Buddhism, the Buddhism of the Buddha, a view supported by many of the scholars of the day. Hence, there is a tendency in some branches of modern Buddhism to represent the Theravada, despite its considerable regional variations in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Burma and Cambodia, as a monolith and as the purest form of Buddhism. Consequently, foreign monks from East Asia who visited Ceylon were often encouraged to take a second ordination there, to return them to the original monastic order. At the same time, modern Buddhists from China and Japan were intent on demonstrating that the Mahayana or, as it was often referred to at that time, 'Northern Buddhism', was the word of the Buddha. D. T. Suzuki's first book in English, Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism (1907), was essentially an apology for the Mahayana. His teacher, Shaku Soen, as we have seen, had defended its authenticity at the World's Parliament of Religions.

But the question of the authenticity of the Mahayana and the historical primacy of the Theravada was not to be resolved by the modern Buddhists. Instead, many sought to identify something that had not existed before, a Buddhism that was free of sectarian concerns and historical developments. There was a sense among many that the various forms of Buddhism in Asia had been polluted by all manner of cultural influences, making them more and more distant from the original teachings of the Buddha. This was not a new idea. Indeed, from early on in India there was the doctrine of the 'decline of the dharma', that in the centuries that followed the death of the Buddha it would become harder and harder to maintain the precepts and follow the path that the Buddha had set forth. In the Pure Land schools of Japanese Buddhism, it was deemed impossible to follow the path of the great saints of the past during the present degenerate age; the only recourse was to accept the grace of the buddha Amitabha and be delivered upon death into h is pure land. In much of the Theravada world, it was held that it was no longer possible to attain nirvana. Instead, one should accumulate merit in order to be reborn as a disciple of the next buddha, Maitreya, in the far future.

What was different about modern Buddhism was the conviction that centuries of cultural and clerical ossification could be stripped from the teachings of the Buddha to reveal a Buddhism that was neither Theravada or Mahayana, neither monastic or lay, neither Sinhalese, Japanese, Chinese or Thai. This was a form of Buddhism whose essential teachings could be encompassed within the pages of a single book. Hence, for the first time in the history of Buddhism, we find in modern Buddhism the tendency to summarize Buddhism in one volume. And it is noteworthy that the first attempts to do so were made not by Buddhist monks in Asia, but by Americans. In 1881, when Colonel Olcott published the first edition of The Buddhist Catechism, it was immediately translated into Sinhala by Dharmapala. In the preface to the thirty-sixth edition he wrote: 'It has always seemed incongruous that an American making no claims at all to scholarship, should be looked to by the Sinhalese nation to help them teach the Dharma to their children, and as I believe I have said in an earlier edition, I only consented to write the Buddhist Catechism after I found that no Bhikkhu [monk] would undertake it.'15 That no such monk was forthcoming suggests more about Olcott's assumptions about Buddhism than it does about any deficiencies in the Sinhalese clergy. In 1894 Paul Carus published The Gospel of the Buddha According to Old Records, a work that D. T. Suzuki, on the instructions of Shaku Soen, translated into Japanese for use in Buddhist seminaries in Japan. In T938 Dwight Goddard published A Buddhist Bible, in which he included texts of his own composition. Thus, when Christmas Humphreys, who had founded the Buddhist Society in London in 1924 (originally as a branch of the Theosophical Society), published the third edition of his Buddhism (1962), he would explain that his 'interest is in world Buddhism as distinct from any of its various Schools', believing 'that only in a combination of all Schools can the full grandeur of Buddhist thought be found'. 16 Such a 'world Buddhism', transcending all regional designation and sectarian affiliation, had not existed prior to the advent of modern Buddhism. The contact of the various forms of Buddhism in Asia during the nineteenth century required the quest to separate what was essential from what was merely cultural, to create something simply called Buddhism.

[t was only in this sense that Buddhism could be regarded as a universal religion. As such, many of the distinctions of other forms of Buddhism faded. For example, whereas it was traditionally held that Buddhism could not exist without the presence of an ordained clergy, many of the leaders of modern Buddhism were laypeople and many of the monks who became leaders of modern Buddhism did not always enjoy the respect, and sometimes not even the cognizance, of the monastic establishment. Indeed, one of the characteristics of modern Buddhism is that teachers who were marginal figures in their own cultures became central on the international scene. Freed from the sexism that has traditionally pervaded the Buddhist monastic orders, women played key roles in the development of modern Buddhism. But modern Buddhism did not dispense with monastic concerns. Instead, it blurred the boundary between the monk and the layperson, with laypeople taking on the vocations of the traditionally elite monks: the study and interpretation of scriptures and the practice of meditation. Each of these factors contributes to a sense of modern Buddhism as shifting emphasis away from the corporate community (especially the community of monks) to the individual, who was able to define for him- or herself a new identity that had not existed before, sometimes even designing new robes that marked a status between the categories of monk and layperson.

The essential practice of modern Buddhism was meditation. In keeping with the quest to return to the origin, modern Buddhists looked back to the central image of the tradition, the Buddha seated in silent meditation beneath a tree, contemplating the ultimate nature of the universe. This silent practice allowed modern Buddhism generally to dismiss the rituals of consecration, purification, expiation and exorcism so common throughout Asia as extraneous elements that had crept into the tradition in response to the needs of those unable to follow the higher path. Silent meditation allowed modern Buddhism once again to transcend local expressions, which required form and language. At the same time, its very silence provided a medium for moving beyond sectarian concerns of institutional and doctrinal formulations by making Buddhism, above all, an experience. Although found in much of modern Buddhism, this view was put forth most strongly in the case of Zen, moving it outside the larger categories of Buddhism and even religion into a universal sensibility of the sacred in the secular.

The strong emphasis on meditation as the central form of Buddhist practice marked one of the most extreme departures of modern Buddhism from previous forms. The practice of meditation had been throughout Buddhist history the domain of monks, and even here meditation was merely one of many vocations within the monastic institution. In China it is estimated that 80 per cent of Buddhist monks resided not in the large training monasteries but in hereditary temples where they earned their livelihood by performing funeral rites and memorial services, and rarely practised meditation. In modern Japan the great majority of Zen priests are the sons of Zen priests and administer the family temple, again devoting much of their energies to services for the dead. They would have received instruction in meditation (as well as other ritual forms) during a stay of one month to three years at a Zen training monastery, usually when they were in their early twenties. During their stay they would receive 'dharma transmission' and hence permission to serve as the head priest of a Zen temple. In Sri Lanka monks who are scholars have traditionally been regarded more highly than meditators. In modern Buddhism, however, meditation is a practice recommended for all, with the goal of enlightenment moved from the distant future to the immediate present.

What, then, is modern Buddhism? The question of the extent to which it is authentically Buddhist is difficult to answer, without first defining what authentic Buddhism might be, a question that has occupied so many modern Buddhists. It seems clear that much of what we regard as Buddhism today is, in fact, modern Buddhism. And modern Buddhism seems to have begun, at least in part, as a response to the threat of modernity, as perceived by certain Asian Buddhists, especially those who had encountered colonialism. Yet these modern Buddhists were very much products of modernity, with the rise of the middle class, the power of the printing press, the ease of international travel. Many of these leaders were deeply involved in independence movements and identified Buddhism with the interests of the state; one thinks of Dharma pal a in Ceylon, T'ai hsu in China, Shaku Soen in Japan, Ledi Sayadaw in Burma and, more recently, the Dalai Lama in exile from Tibet. Yet together they have forged an international Buddhism that transcends cultural and national boundaries, creating in the following generation a cosmopolitan network of intellectuals, writing most often in English.

It is perhaps best to consider modern Buddhism not as a universal religion beyond sectarian borders, but as itself a Buddhist sect. There is Thai Buddhism, there is Tibetan Buddhism, there is Korean Buddhism, and there is Modern Buddhism. Unlike previous forms of national Buddhism, this new Buddhism does not stand in a relation of mutual exclusion to these other forms. One may be a Chinese Buddhist and also be a modern Buddhist. Yet one may also be a Chinese Buddhist without being a modern Buddhist. Like other Buddhist sects, modern Buddhism has its own lineage, its own doctrines, its own practices, some of which have been outlined above. And like other Buddhist sects, modern Buddhism has its own canon of sacred scriptures, many of which appear in the pages that follow.

This book presents selections from the works of thirty-one figures -- monks and laymen, nuns and laywomen, poets and missionaries, meditation masters and social revolutionaries - who have figured in the formation of modern Buddhism. Each extract is preceded by a short introduction, providing a biographical sketch of the author in question and brief comment on the reading. What is remarkable about the lives of these figures is the degree of their interconnection. There is not a single author included here who was not acquainted with at least one other, thus creating the lineage so essential to modern Buddhism. In order to emphasize the development of this lineage, the authors are presented chronologically, in order of the year of their birth. The passages from their works are presented as they appear in the editions from which they are drawn, preserving the variant spellings, transliteration and punctuation (or lack of it). A few misprints have been silently emended, and some elements of presentation (such as footnote markers) made consistent.

This anthology is very much a preliminary work. The lives and works of the authors included here deserve much more comment and analysis than I have been able to provide. And many other figures might have been included. For example, none of the major scholars in the development of the academic discipline of Buddhist Studies are discussed, despite their great importance in the formation of popular conceptions of Buddhism. And many of the more recent leaders of modern Buddhism deserve study. The present work seeks more modestly to offer a small sample of the remarkable group of men and women whose works and lives -- some peripherally, some directly -- have created a form of Buddhism that is both so new, and so familiar.

_______________

Notes:1. A Full Account if the Buddhist Controversy, held at Pantura, in August, 1873. By the 'Ceylon Times' Special Reporter: with the Addresses Revised and Amplified by the Speakers (Colombo: Ceylon Times Office, 1873), p. 2.

2. For a detailed study of the debate, its antecedents and aftermath, see R. F. Young and G. P.V Somaratna, Vain Debates: The Buddhist-Christian Controversies of Nineteenth-Century Ceylon (Vienna: de Nobili Research Library, 1996).

3. A Full Account of the Buddhist Controversy, held at Pantura, i,n August, 1873, pp. 10-11.

4. Ibid., p. 13.

5. Ibid., pp. 2-3.

6. Cited in Stephen Prothero, The White Buddhist: The Asian Odyssey if Henry Steel Olcott (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), P.96.

7. This description of Chinese Buddhism is drawn from what remains the standard work on the subject: Holmes Welch, The Buddhist Revival in China (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968).

8. The biography of the Venerable Voramai Kabilsingh was drawn from Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, 'Voramai Kabilsingh' in Spring Wind: Buddhist Cultural Forum, vol. 6, nos. 1-3: pp. 202-9.

9. On the debates over clerical marriage, see Richard Jaffe, Neither Monk Nor Layman: Clerical Marriage in Modern Japanese Buddhism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001).

10. On Meiji policies regarding Buddhism and Buddhist responses, see Richard Jaffe, Neither Monk Nor Layman: Clerical Marriage in Modern Japanese Buddhism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001); James Edward Ketelaar, Of Heretics and Martyrs in Meiji Japan (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990); and Brian Victoria, Zen at War (New York: Weatherhill, 1997).

11. Shokin Furuta, 'Shaku Soen: The Footsteps of a Modern Japanese Zen Master' in The Modernization of Japan, a Special Edition in the Philosophical Studies of Japan series, vol. 7 (Tokyo: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, 1967), p. 76. The biography of Soen presented here is drawn largely from this source.

12. See Robert Sharf, 'The Zen of Japanese Nationalism' in Donald S. Lopez, Jr (ed.), Curators of the Buddha: The Study of Buddhism Under Colonialism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), pp. 107-60.

13. On Yasutani and his influence, see Robert Sharf, 'Sanbokyodan: Zen and Way of the New Religions,' Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 22, 3- 4 (Autumn 1995): pp. 417- 58.

14. Dge 'dun chos 'phel, Rgya gar gyi gnas chen khag la bgrod pa'i lam yig (Guide to the Holy Places of India) in Hor khang bsod nams dpal 'bar (ed.), Dge 'dun chos 'phel gyi gsung rtsom, vol. 2 (Gang can rig mdzod 12; Lhasa: Bod ljongs bod yig dpe rnying dpe skrun khang, 1990), p. 319.

15. Henry S. Olcott, The Buddhist Catechism, 44th edition (Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1947), p. xii. It is important to note that Gunananda, who had fallen out with Olcott over matters both financial and ideological, wrote his own 'catechism' in 1887 (see Young and Somaratna, pp. 206-9). Gunananda particularly objected to Olcott's condemnation of traditional forms of Buddhist devotion. In 1888 he denounced Theosophy as a heresy and a threat to Buddhism (see Young and Somaratna, p. 212).

16. Christmas Humphreys, Buddhism, 3rd edition (London: Penguin, 1962), p. i.