Part 2 of 2

Evangelical ChristianityA supporter of the evangelical wing of the Church of England, Wilberforce believed that the revitalisation of the church and individual Christian observance would lead to a harmonious, moral society.[160] He sought to elevate the status of religion in public and private life, making piety fashionable in both the upper- and middle-classes of society.[181] To this end, in April 1797, Wilberforce published A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians in the Higher and Middle Classes of This Country Contrasted With Real Christianity, on which he had been working since 1793. This was an exposition of New Testament doctrine and teachings and a call for a revival of Christianity, as a response to the moral decline of the nation, illustrating his own personal testimony and the views which inspired him. The book proved to be influential and a best-seller by the standards of the day; 7,500 copies were sold within six months, and it was translated into several languages.[182][183]

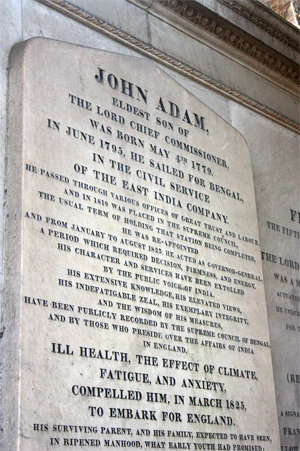

Wilberforce fostered and supported missionary activity in Britain and abroad. He was a founding member of the Church Missionary Society (since renamed the Church Mission Society) and was involved, with other members of the Clapham Sect, in numerous other evangelical and charitable organisations.[184][185] Horrified by the lack of Christian evangelism in India, Wilberforce used the 1793 renewal of the British East India Company's charter to propose the addition of clauses requiring the company to provide teachers and chaplains and to commit to the "religious improvement" of Indians. The plan was unsuccessful due to lobbying by the directors of the company, who feared that their commercial interests would be damaged.[186][187] Wilberforce tried again in 1813, when the charter next came up for renewal. Using petitions, meetings, lobbying and letter writing, he successfully campaigned for changes to the charter.[160][188] Speaking in favour of the Charter Act 1813, he criticised the East India Company and their rule in India for its hypocrisy and racial prejudice, while also condemning aspects of Hinduism including the caste system, infanticide, polygamy and suttee. "Our religion is sublime, pure beneficent", he said, "theirs is mean, licentious and cruel".[188][189]Moral reformGreatly concerned by what he perceived to be the degeneracy of British society, Wilberforce was also active in matters of moral reform, lobbying against "the torrent of profaneness that every day makes more rapid advances", and considered this issue and the abolition of the slave trade as equally important goals.[190] At the suggestion of Wilberforce and Bishop Porteus, King George III was requested by the Archbishop of Canterbury to issue in 1787 the Proclamation for the Discouragement of Vice, as a remedy for the rising tide of immorality.[191][192] The proclamation commanded the prosecution of those guilty of "excessive drinking, blasphemy, profane swearing and cursing, lewdness, profanation of the Lord's Day, and other dissolute, immoral, or disorderly practices".[193] Greeted largely with public indifference, Wilberforce sought to increase its impact by mobilising public figures to the cause,[194] and by founding the Society for the Suppression of Vice.[194][195] This and other societies in which Wilberforce was a prime mover, such as the Proclamation Society, mustered support for the prosecution of those who had been charged with violating relevant laws, including brothel keepers, distributors of pornographic material, and those who did not respect the Sabbath.[160] Years later, the writer and clergyman Sydney Smith criticised Wilberforce for being more interested in the sins of the poor than those of the rich, and suggested that a better name would have been the Society for "suppressing the vices of persons whose income does not exceed £500 per annum".[65][196] The societies were not highly successful in terms of membership and support, although their activities did lead to the imprisonment of Thomas Williams, the London printer of Thomas Paine's The Age of Reason.[84][137] Wilberforce's attempts to legislate against adultery and Sunday newspapers were also in vain; his involvement and leadership in other, less punitive, approaches were more successful in the long-term, however. By the end of his life, British morals, manners, and sense of social responsibility had increased, paving the way for future changes in societal conventions and attitudes during the Victorian era.[1][160][197]

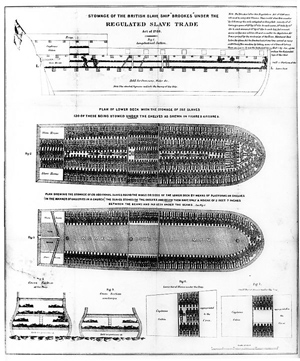

Emancipation of enslaved AfricansThe hopes of the abolitionists notwithstanding, slavery did not wither with the end of the slave trade in the British Empire, nor did the living conditions of the enslaved improve. The trade continued, with few countries following suit by abolishing the trade, and with some British ships disregarding the legislation. Wilberforce worked with the members of the African Institution to ensure the enforcement of abolition and to promote abolitionist negotiations with other countries.[160][198][199] In particular, the US had abolished the slave trade in 1808, and Wilberforce lobbied the American government to enforce its own prohibition more strongly.[200]

The same year, Wilberforce moved his family from Clapham to a sizable mansion with a large garden in Kensington Gore, closer to the Houses of Parliament. Never strong, and by 1812 in worsening health, Wilberforce resigned his Yorkshire seat, and became MP for the rotten borough of Bramber in Sussex, a seat with little or no constituency obligations, thus allowing him more time for his family and the causes that interested him.[201]

From 1816 Wilberforce introduced a series of bills which would require the compulsory registration of slaves, together with details of their country of origin, permitting the illegal importation of foreign slaves to be detected. Later in the same year he began publicly to denounce slavery itself, though he did not demand immediate emancipation, as "They had always thought the slaves incapable of liberty at present, but hoped that by degrees a change might take place as the natural result of the abolition."[202]In 1820, after a period of poor health, and with his eyesight failing, Wilberforce took the decision to further limit his public activities,[203] although he became embroiled in unsuccessful mediation attempts between King George IV, and his estranged wife Caroline of Brunswick, who had sought her rights as queen.[1] Nevertheless, Wilberforce still hoped "to lay a foundation for some future measures for the emancipation of the poor slaves", which he believed should come about gradually in stages.[204] Aware that the cause would need younger men to continue the work, in 1821 he asked fellow MP Thomas Fowell Buxton to take over leadership of the campaign in the Commons.[203] As the 1820s wore on, Wilberforce increasingly became a figurehead for the abolitionist movement, although he continued to appear at anti-slavery meetings, welcoming visitors, and maintaining a busy correspondence on the subject.[205][206][207]

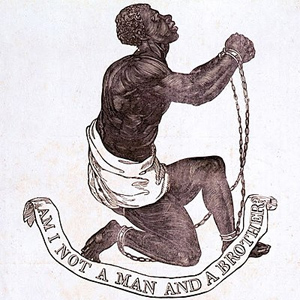

The year 1823 saw the founding of the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery (later the Anti-Slavery Society),[208] and the publication of Wilberforce's 56-page Appeal to the Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire in Behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies.[209] In his treatise, Wilberforce urged that total emancipation was morally and ethically required, and that slavery was a national crime that must be ended by parliamentary legislation to gradually abolish slavery.[210] Members of Parliament did not quickly agree, and government opposition in March 1823 stymied Wilberforce's call for abolition.[211] On 15 May 1823, Buxton moved another resolution in Parliament for gradual emancipation.[212] Subsequent debates followed on 16 March and 11 June 1824 in which Wilberforce made his last speeches in the Commons, and which again saw the emancipationists outmanoeuvred by the government.[213][214]

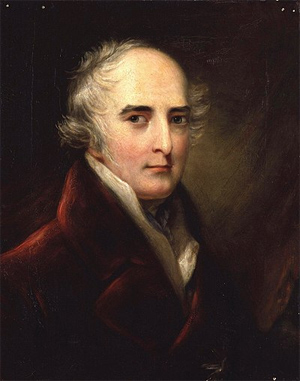

Last yearsWilberforce's health was continuing to fail, and he suffered further illnesses in 1824 and 1825. With his family concerned that his life was endangered, he declined a peerage[215] and resigned his seat in Parliament, leaving the campaign in the hands of others.[175][216] Thomas Clarkson continued to travel, visiting anti-slavery groups throughout Britain, motivating activists and acting as an ambassador for the anti-slavery cause to other countries,[68] while Buxton pursued the cause of reform in Parliament.[217] Public meetings and petitions demanding emancipation continued, with an increasing number supporting immediate abolition rather than the gradual approach favoured by Wilberforce, Clarkson and their colleagues.[218][219]

Wilberforce was buried in Westminster Abbey next to Pitt. This memorial statue, by Samuel Joseph (1791–1850), was erected in 1840 in the north choir aisle.

Wilberforce was buried in Westminster Abbey next to Pitt. This memorial statue, by Samuel Joseph (1791–1850), was erected in 1840 in the north choir aisle.In 1826, Wilberforce moved from his large house in Kensington Gore to Highwood Hill, a more modest property in the countryside of Mill Hill, north of London,[175] where he was soon joined by his son William and family. William had attempted a series of educational and career paths, and a venture into farming in 1830 led to huge losses, which his father repaid in full, despite offers from others to assist. This left Wilberforce with little income, and he was obliged to let his home and spend the rest of his life visiting family members and friends.[220] He continued his support for the anti-slavery cause, including attending and chairing meetings of the Anti-Slavery Society.[221]

Wilberforce approved of the 1830 election victory of the more progressive Whigs, though he was concerned about the implications of their Reform Bill which proposed the redistribution of parliamentary seats towards newer towns and cities and an extension of the franchise. In the event, the Reform Act 1832 was to bring more abolitionist MPs into Parliament as a result of intense and increasing public agitation against slavery. In addition, the 1832 slave revolt in Jamaica convinced government ministers that abolition was essential to avoid further rebellion.[222] In 1833, Wilberforce's health declined further and he suffered a severe attack of influenza from which he never fully recovered.[1]

He made a final anti-slavery speech in April 1833 at a public meeting in Maidstone, Kent.[223] The following month, the Whig government introduced the Bill for the Abolition of Slavery, formally saluting Wilberforce in the process.[224] On 26 July 1833, Wilberforce heard of government concessions that guaranteed the passing of the Bill for the Abolition of Slavery.[225] The following day he grew much weaker, and he died early on the morning of 29 July at his cousin's house in Cadogan Place, London.[226][227]

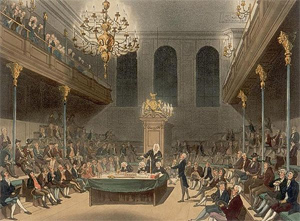

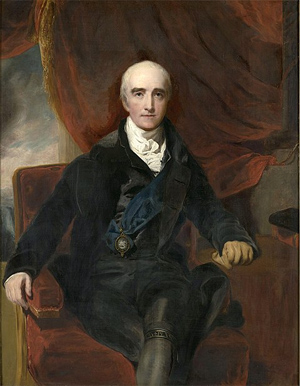

One month later, the House of Lords passed the Slavery Abolition Act, which abolished slavery in most of the British Empire from August 1834.[228] They voted plantation owners £20 million in compensation, giving full emancipation to children younger than six, and instituting a system of apprenticeship requiring other enslaved peoples to work for their former masters for four to six years in the British West Indies, South Africa, Mauritius, British Honduras and Canada. Nearly 800,000 African slaves were freed, the vast majority in the Caribbean.[229][230]FuneralWilberforce had requested that he was to be buried with his sister and daughter at Stoke Newington, just north of London. However, the leading members of both Houses of Parliament urged that he be honoured with a burial in Westminster Abbey. The family agreed and, on 3 August 1833, Wilberforce was buried in the north transept, close to his friend William Pitt the Younger.[231] The funeral was attended by many Members of Parliament, as well as by members of the public. The pallbearers included the Duke of Gloucester, the Lord Chancellor Henry Brougham and the Speaker of the House of Commons Charles Manners-Sutton.[232][233][234]

While tributes were paid and Wilberforce was laid to rest, both Houses of Parliament suspended their business as a mark of respect.[235]

Legacy The Wilberforce Monument in the grounds of Hull College, Hull, erected in 1834.

The Wilberforce Monument in the grounds of Hull College, Hull, erected in 1834.Five years after his death, sons Robert and Samuel Wilberforce published a five-volume biography about their father, and subsequently a collection of his letters in 1840. The biography was controversial in that the authors emphasised Wilberforce's role in the abolition movement and played down the important work of Thomas Clarkson. Incensed, Clarkson came out of retirement to write a book refuting their version of events, and the sons eventually made a half-hearted private apology to him and removed the offending passages in a revision of their biography.[236][237][238] However, for more than a century, Wilberforce's role in the campaign dominated the history books. Later historians have noted the warm and highly productive relationship between Clarkson and Wilberforce, and have termed it one of history's great partnerships: without both the parliamentary leadership supplied by Wilberforce and the research and public mobilisation organised by Clarkson, abolition could not have been achieved.[68][239][240]

As his sons had desired and planned, Wilberforce has long been viewed as a Christian hero, a statesman-saint held up as a role model for putting his faith into action.[1][241][242] More broadly, he has also been described as a humanitarian reformer who contributed significantly to reshaping the political and social attitudes of the time by promoting concepts of social responsibility and action.[160] In the 1940s, the role of Wilberforce and the Clapham Sect in abolition was downplayed by historian Eric Williams, who argued that abolition was motivated not by humanitarianism but by economics, as the West Indian sugar industry was in decline.[58][243] Williams' approach strongly influenced historians for much of the latter part of the 20th century. However, more recent historians have noted that the sugar industry was still making large profits at the time of the abolition of the slave trade, and this has led to a renewed interest in Wilberforce and the Evangelicals, as well as a recognition of the anti-slavery movement as a prototype for subsequent humanitarian campaigns.[58][244]

In 1942, Wilberforce was portrayed by John Mills in the biographical film about the life of William Pitt the Younger, The Young Mr. Pitt.

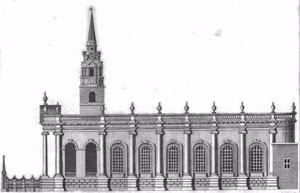

MemorialsWilberforce's life and work have been widely commemorated. In Westminster Abbey, a seated statue of Wilberforce by Samuel Joseph was erected in 1840, bearing an epitaph praising his Christian character and his long labour to abolish the slave trade and slavery itself.[245]

In Wilberforce's home town of Hull, a public subscription in 1834 funded the Wilberforce Monument, a 31-metre (102 ft) Greek Doric column topped by a statue of Wilberforce, which now stands in the grounds of Hull College near Queen's Gardens.[246] Wilberforce's birthplace was acquired by the city corporation in 1903 and, following renovation, Wilberforce House in Hull was opened as Britain's first slavery museum.[247] Wilberforce Memorial School for the Blind in York was established in 1833 in his honour,[248] and in 2006 the University of Hull established the Wilberforce Institute for the study of Slavery and Emancipation in Oriel Chambers, a building adjoining Wilberforce's birthplace.[249] Various churches within the Anglican Communion commemorate Wilberforce in their liturgical calendars,[250] and Wilberforce University in Ohio, United States, founded in 1856, is named after him. The university was the first owned by African-American people, and is a historically black college.[251][252] In Ontario, Canada, Wilberforce Colony was founded by black reformers, and inhabited by free slaves from the United States.[253] In 2019, St. Clements University, which is registered in the Turks and Caicos Islands (British West Indies), founded the William Wilberforce International Human Rights Law Centre.[254]

Amazing Grace, a film about Wilberforce and the struggle against the slave trade, directed by Michael Apted and starring Ioan Gruffudd and Benedict Cumberbatch was released in 2007 to coincide with the 200th anniversary of Parliament's anti-slave trade legislation.[255][256]

Bibliography• Wilberforce, William (1797), A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Middle and Higher Classes in this Country, Contrasted with Real Christianity, London: T. Caddell

• Wilberforce, William (1807), A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade, Addressed to the Freeholders of Yorkshire, London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, J. Hatchard

• Wilberforce, William (1823), An Appeal to the Religion, Justice, and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire in behalf of the Negro slaves in the West Indies, London: J. Hatchard and Son

See also• List of abolitionist forerunners

• List of civil rights leaders

• The Wilberforce Institute for the study of Slavery and Emancipation

• The Wilberforce Society

Notes1. Wolffe, John; Harrison, B. (May 2006) [online edition; first published September 2004]. "Wilberforce, William (1759–1833)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29386. ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

2. Pollock 1977, p. 6

3. Stott 2012, p. 16

4. Lead, cotton, tools and cutlery were among the more frequent exports from Hull to the Baltic countries, with timber, iron ore, yarns, hemp, wine and manufactured goods being imported to Britain on the return journey.Hague 2007, p. 3

5. Jackson 1972, p. 196

6. Young, Angus (12 January 2020). "The forgotten tragedy now hidden by a car park in Hull city centre". Hull Daily Mail / Hull Live.

7. Mawer, Bryan (2011). From Sweat to Sweetness. London: AGFHS Publications. ISBN 978-09547632-7-5.

8. Pollock 1977, p. 3

9. Tomkins 2007, p. 9

10. Pollock 1977, p. 4

11. Hague 2007, p. 5

12. Hague 2007, pp. 6–8

13. Hague 2007, pp. 14–15

14. Pollock 1977, pp. 5–6

15. Hague 2007, p. 15

16. Hague 2007, pp. 18–19

17. Pollock 1977, p. 7

18. Hague 2007, p. 20

19. Pollock 1977, pp. 8–9

20. Hague 2007, p. 23

21. Hague, William (2004), William Pitt the Younger, London: HarperPerennial, p. 29, ISBN 978-1-58134-875-0

22. Pollock 1977, p. 9

23. "Wilberforce, William (WLBR776W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

24. Hague 2007, pp. 24–25

25. Pollock 1977, p. 11

26. Hochschild 2005, p. 125

27. Hague 2007, p. 36

28. Hague 2007, p. 359

29. Oldfield 2007, p. 44

30. Hochschild 2005, pp. 125–26

31. Pollock 1977, p. 15

32. Wilberforce, Robert Isaac; Wilberforce, Samuel (1838), The Life of William Wilberforce, John Murray

33. "Sickly shrimp of a man who sank the slave ships", The Sunday Times, London: The Times, 25 March 2005, retrieved 27 November 2007

34. Hague 2007, pp. 44–52

35. Hague 2007, pp. 53–55

36. Pollock 1977, p. 23

37. Pollock 1977, pp. 23–24

38. Hague 2007, pp. 52–53, 59

39. Pollock 1977, p. 31

40. Hague 2007, pp. 70–72

41. Hague 2007, pp. 72–74

42. Pollock 1977, p. 37

43. Hague 2007, pp. 99–102

44. Hague 2007, pp. 207–10

45. Brown 2006, pp. 380–82

46. Pollock 1977, p. 38

47. Brown 2006, p. 383

48. Brown 2006, p. 386

49. Bradley, Ian (1985), "Wilberforce the Saint", in Jack Hayward (ed.), Out of Slavery: Abolition and After, Frank Cass, pp. 79–81, ISBN 978-0-7146-3260-5

50. Hague 2007, p. 446

51. Hague 2007, p. 97

52. Hague 2007, pp. 97–99

53. Pollock 1977, pp. 40–42

54. Hague 2007, pp. 116, 119

55. D'Anjou 1996, p. 97

56. Hochschild 2005, pp. 14–15

57. Hochschild 2005, p. 32

58. Pinfold, John (2007), "Introduction", in Bodleian Library (ed.), The Slave Trade Debate: Contemporary Writings For and Against, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, ISBN 978-1-85124-316-7

59. Ackerson 2005, p. 9

60. Pollock 1977, p. 17

61. Hague 2007, pp. 138–39

62. Brown 2006, pp. 351–52, 362–63

63. Brown 2006, pp. 364–66

64. Pollock 1977, p. 48

65. Tomkins 2007, p. 55

66. Hague 2007, p. 140

67. Pollock 1977, p. 53

68. Brogan, Hugh; Harrison, B. (October 2007) [online edition; first published September 2004]. "Clarkson, Thomas (1760–1846)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5545. ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

69. Metaxas, Eric (2007), Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery, New York: HarperSanFrancisco, p. 111, ISBN 978-0-06-128787-9

70. Pollock 1977, p. 55

71. Hochschild 2005, pp. 123–24

72. Clarkson, Thomas (1836), The History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade, Online – Project Gutenberg

73. Hochschild 2005, p. 122

74. D'Anjou 1996, pp. 157–158

75. Pollock 1977, p. 56

76. Hochschild 2005, pp. 122–124

77. Tomkins 2007, p. 57

78. Pollock 1977, p. 58 quoting Harford, p. 139

79. Brown 2006, pp. 26, 341, 458–459

80. Hague 2007, pp. 143, 119

81. Pinfold 2007, pp. 10, 13

82. Pollock 1977, p. 69

83. Piper, John (2006), Amazing Grace in the Life of William Wilberforce, Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books, p. 35, ISBN 978-1-58134-875-0

84. Brown 2006, pp. 386–387

85. Ackerson 2005, pp. 10–11

86. Ackerson 2005, p. 15

87. Fogel, Robert William (1989), Without Consent Or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery, W. W. Norton & Company, p. 211, ISBN 978-0-393-31219-5

88. Oldfield 2007, pp. 40–41

89. Ackerson 2005, p. 11

90. Hague 2007, pp. 149–151

91. Crawford, Neta C. (2002), Argument and Change in World Politics: Ethics, Decolonization, and Humanitarian Intervention, Cambridge University Press, p. 178, ISBN 0-521-00279-6

92. Hochschild 2005, p. 127

93. Hochschild 2005, pp. 136, 168

94. Brown 2006, p. 296

95. Fisch, Audrey A (2007), The Cambridge Companion to the African American Slave Narrative, Cambridge University Press, p. xv, ISBN 978-0-521-85019-3

96. Hochschild 2005, pp. 5–6

97. Pollock 1977, pp. 78–79

98. Hague 2007, pp. 149–157

99. Hochschild 2005, p. 139

100. Pollock 1977, pp. 79–81

101. Pollock 1977, p. 82

102. Hague 2007, p. 159

103. D'Anjou 1996, p. 166

104. Hague 2007, pp. 178–183

105. Hochschild 2005, p. 160

106. Hague 2007, pp. 185–186

107. Hochschild 2005, pp. 161–162

108. Hague 2007, pp. 187–189

109. Hochschild 2005, pp. 256–267, 292–293

110. Hague 2007, pp. 189–190

111. Hochschild 2005, p. 188

112. Hague 2007, pp. 201–202

113. Hansard, T.C. (printer) (1817), The Parliamentary history of England from the earliest period to the year 1803, XXIX, London: Printed by T.C. Hansard, p. 278

114. Hague 2007, p. 193

115. Pollock 1977, pp. 105–108

116. D'Anjou 1996, p. 167

117. Hague 2007, pp. 196–198

118. Walvin, James (2007), A Short History of Slavery, Penguin Books, p. 156, ISBN 978-0-14-102798-2

119. Pollock 1977, p. 218

120. D'Anjou 1996, p. 140

121. Wolffe, John; Harrison, B.; Goldman, L. (May 2007). "Clapham Sect (act. 1792–1815)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/42140. ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

122. Hague 2007, pp. 218–219

123. Turner, Michael (April 1997), "The limits of abolition: Government, Saints and the 'African Question' c 1780–1820", The English Historical Review, Oxford University Press, 112 (446): 319–357, doi:10.1093/ehr/cxii.446.319, JSTOR 578180

124. Hochschild 2005, p. 150

125. Hague 2007, pp. 223–224

126. Rashid, Ismail (2003), "A Devotion to the idea of liberty at any price: Rebellion and Antislavery in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Upper Guinea Coast", in Sylviane Anna Diouf (ed.), Fighting the Slave Trade: West African Strategies, Ohio University Press, p. 135, ISBN 0-8214-1516-6

127. Ackerson 2005, p. 220

128. Pollock 1977, p. 114

129. Pollock 1977, p. 115

130. Pollock 1977, pp. 122–123

131. Hague 2007, p. 242

132. Pollock 1977, pp. 121–122

133. Hague 2007, pp. 247–249

134. Hague 2007, pp. 237–239

135. Ackerson 2005, p. 12

136. Hague 2007, p. 243

137. Hochschild 2005, p. 252

138. Hague 2007, p. 511

139. Hague 2007, p. 316

140. Hague 2007, pp. 313–320

141. Hague 2007, pp. 328–330

142. Pollock 1977, p. 201

143. Hague 2007, pp. 332–334

144. Hague 2007, pp. 335–336

145. Drescher, Seymour (Spring 1990), "People and Parliament: The Rhetoric of the British Slave Trade", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, MIT Press, 20 (4): 561–580, doi:10.2307/203999, JSTOR 203999

146. Pollock 1977, p. 211

147. Hague 2007, pp. 342–344

148. Hochschild 2005, pp. 304–306

149. Hague 2007, p. 348

150. Hague 2007, p. 351

151. Tomkins 2007, pp. 166–168

152. Hague 2007, p. 354

153. Hague 2007, p. 355

154. Pollock 1977, p. 214

155. Hochschild 2005, p. 251

156. Pollock 1977, p. 157

157. Hague 2007, pp. 294–295

158. Hague 2007, pp. 440–441

159. Cobbett, William (1823), Cobbett's Political Register, Cox and Baylis, p. 516

160. Hind, Robert J. (1987), "William Wilberforce and the Perceptions of the British People", Historical Research, 60 (143): 321–335, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1987.tb00500.x

161. Hague 2007, pp. 250, 254–256

162. Hague 2007, p. 286

163. Hague 2007, pp. 441–442

164. Hague 2007, p. 442

165. Tomkins 2007, pp. 195–196

166. Hazlitt, William (1825), The spirit of the age, London: C. Templeton, p. 185

167. Hochschild 2005, pp. 324–327

168. Hague 2007, p. 487

169. Tomkins 2007, pp. 172–173

170. Hague 2007, pp. 406–407

171. Hague 2007, p. 447

172. Pollock 1977, pp. 92–93

173. Stott 2003, pp. 103–105, 246–447

174. Hague 2007, pp. 74, 498

175. Tomkins 2007, p. 207

176. "RNLI Our History". RNLI. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

177. Hague 2007, pp. 287–288

178. Hochschild 2005, p. 299

179. Hochschild 2005, p. 315

180. Hague 2007, pp. 211–212, 295, 300

181. Brown 2006, pp. 385–386

182. Hague 2007, pp. 271–272, 276

183. Pollock 1977, pp. 146–153

184. Pollock 1977, p. 176

185. Hague 2007, pp. 220–221

186. Tomkins 2007, pp. 115–116

187. Hague 2007, pp. 221, 408

188. Tomkins 2007, pp. 187–188

189. Keay, John (2000), India: A History, New York: Grove Press, p. 428, ISBN 0-8021-3797-0

190. Tomkins 2007, pp. 54–55

191. Pollock 1977, p. 61

192. Brown 2006, p. 346

193. Hochschild 2005, p. 126

194. Hague 2007, p. 108

195. Brown 2006, p. 385

196. Hague 2007, p. 109

197. Hague 2007, p. 514

198. Tomkins 2007, pp. 182–183

199. Ackerson 2005, pp. 142, 168, 209

200. Hague 2007, pp. 393–394, 343

201. Hague 2007, pp. 377–379, 401–406

202. Hague 2007, pp. 415, 343

203. Pollock 1977, p. 279

204. Hague 2007, p. 474

205. Ackerson 2005, p. 181

206. Oldfield 2007, p. 48

207. Hague 2007, pp. 492–493, 498

208. Pollock 1977, p. 286

209. Pollock 1977, p. 285

210. Hague 2007, pp. 477–479

211. Hague 2007, p. 481

212. Tomkins 2007, p. 203

213. Pollock 1977, p. 289

214. Hague 2007, p. 480

215. According to George W. E. Russell, on the grounds that it would exclude his sons from intimacy with private gentlemen, clergymen and mercantile families, (1899), Collections & Recollections, revised edition, Elder Smith & Co, London, p. 77.

216. Oldfield 2007, p. 45

217. Blouet, Olwyn Mary; Harrison, B. (October 2007) [online edition; first published September 2004]. "Buxton, Sir Thomas Fowell, first baronet (1786–1845)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4247. ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

218. Hague 2007, pp. 486–487

219. Tomkins 2007, pp. 206–207

220. Hague 2007, p. 494

221. Tomkins 2007, p. 213

222. Hague 2007, p. 498

223. Tomkins 2007, p. 217

224. Hague 2007, pp. 498–499

225. Hague 2007, p. 502

226. Pollock 1977, p. 308

227. Hague 2007, pp. 502–503

228. The legislation specifically excluded the territories of the Honourable East India Company which were not then under direct Crown control.

229. Kerr-Ritchie, Jeffrey R. (2007), Rites of August First: Emancipation Day in the Black Atlantic World, LSU Press, pp. 16–17, ISBN 978-0-8071-3232-6

230. Britain, Great; Evans, William David; Hammond, Anthony; Granger, Thomas Colpitts (1836), Slavery Abolition Act 1833, W. H. Bond

231. Hague 2007, p. 304

232. Hague 2007, p. 504

233. Pollock 1977, pp. 308–309

234. "Funeral of the Late Mr. Wilberforce", The Times (15235), pp. 3, col. C, 5 August 1833

235. Hague, William. Wilberforce Address, Conservative Christian Fellowship(November 1998)

236. Clarkson, Thomas (1838), Strictures on a Life of William Wilberforce, by the Rev. W. Wilberforce and the Rev. S. Wilberforce, London

237. Ackerson 2005, pp. 36–37, 41

238. Hochschild 2005, pp. 350–351

239. Hague 2007, pp. 154–155, 509

240. Hochschild 2005, pp. 351–352

241. "William Wilberforce", The New York Times, 13 December 1880, retrieved 24 March 2008

242. Oldfield 2007, pp. 48–49

243. Williams, Eric (1944), Capitalism and Slavery, University of North Carolina Press, p. 211, ISBN 978-0-8078-4488-5

244. D'Anjou 1996, p. 71

245. William Wilberforce, Westminster Abbey, retrieved 21 March 2008

246. The Wilberforce Monument, BBC, retrieved 21 March 2008

247. Oldfield 2007, pp. 70–71

248. Oldfield 2007, pp. 66–67

249. "Centre for slavery research opens". BBC News. London: BBC. 6 July 2006. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

250. Bradshaw, Paul (2002), The New SCM Dictionary of Liturgy and Worship, SCM-Canterbury Press Ltd, p. 420, ISBN 0-334-02883-3

251. Ackerson 2005, p. 145

252. Beauregard, Erving E. (2003), Wilberforce University in "Cradles of Conscience: Ohio's Independent Colleges and Universities" Eds. John William. Oliver Jr., James A. Hodges, and James H. O'Donnell, Kent State University Press, pp. 489–490, ISBN 978-0-87338-763-7

253. Richard S. Newman (2008), Freedom's prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black founding fathers, NYU Press, p. 271, ISBN 978-0-8147-5826-7

254.

http://www.stclementsinnofcourt.com255. Langton, James; Hastings, Chris (25 February 2007), "Slave film turns Wilberforce into a US hero", Daily Telegraph, retrieved 16 April 2008

256. Riding, Alan (14 February 2007), "Abolition of slavery is still an unfinished story", International Herald Tribune, retrieved 16 April 2008

References• Ackerson, Wayne (2005), The African Institution (1807–1827) and the Antislavery Movement in Great Britain, Lewiston, New York: E. Mellen Press, ISBN 978-0-7734-6129-1, OCLC 58546501

• Bayne, Peter (1890), Men Worthy to Lead; Being Lives of John Howard, William Wilberforce, Thomas Chalmers, Thomas Arnold, Samuel Budgett, John Foster, London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Ltd, Reprinted by Bibliolife, ISBN 1-152-41551-4

• Belmonte, Kevin (2002), Hero for Humanity: A Biography of William Wilberforce, Colorado Springs, Colorado: Navpress Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-57683-354-4, OCLC 49952624

• Brown, Christopher Leslie (2006), Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 978-0-8078-5698-7, OCLC 62290468

• Carey, Brycchan (2005), British Abolitionism and the Rhetoric of Sensibility: Writing, Sentiment, and Slavery, 1760–1807, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-4039-4626-3, OCLC 58721077

• Coupland, Reginald. Wilberforce: A Narrative (1923) online

• D'Anjou, Leo (1996), Social Movements and Cultural Change: The First Abolition Campaign Revisited, New York: Aldine de Gruyter, ISBN 978-0-202-30522-6, OCLC 34151187

• Furneaux, Robin (2006) [1974], William Wilberforce, London: Hamish Hamilton, ISBN 978-1-57383-343-1, OCLC 1023912

• Hague, William (2007), William Wilberforce: The Life of the Great Anti-Slave Trade Campaigner, London: HarperPress, ISBN 978-0-00-722885-0, OCLC 80331607 online free to borrow

• Hennell, Michael (1950), William Wilberforce, 1759–1833: the Liberator of the Slave, London: Church Book Room, OCLC 8824569

• Hochschild, Adam (2005), Bury the Chains, The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery, London: Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-330-48581-4, OCLC 60458010

• Jackson, Gordon (1972), Hull in the Eighteenth Century: A Study in Economic and Social History, Oxford: University Press

• Metaxas, Eric (2007), Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery, New York: HarperSanFrancisco, ISBN 978-0-06-117300-4, OCLC 81967213

• Oldfield, John (2007), Chords of Freedom: Commemoration, Ritual and British Transatlantic Slavery, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-6664-1, OCLC 132318401

• Pollock, John (1977), Wilberforce, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-09-460780-4, OCLC 3738175

• Pura, Murray Andrew (2002), Vital Christianity: The Life and Spirituality of William Wilberforce, Toronto: Clements, ISBN 1-894667-10-7, OCLC 48242442

• Reed, Lawrence W. (2008). "Wilberforce, William (1759–1833)". In Hamowy, Ronald(ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 544–545. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n330. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

• Rodriguez, Junius (2007), Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-0-7656-1257-1, OCLC 75389907

• Stott, Anne (2003), Hannah More: The First Victorian, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-924532-1, OCLC 186342431

• Stott, Anne (2012), Wilberforce: Family and Friends, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-969939-1

• Tomkins, Stephen (2007), William Wilberforce – A Biography, Oxford: Lion, ISBN 978-0-09-460780-4, OCLC 72149062

• Vaughan, David J. (2002), Statesman and Saint: The Principled Politics of William Wilberforce, Nashville, Tennessee: Cumberland House, ISBN 978-1-58182-224-3, OCLC 50464553

• Walvin, James (2007), A Short History of Slavery, London: Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-102798-2, OCLC 75713230

• Wilberforce, R. I; Wilberforce, S. (1838), The Life of William Wilberforce, London: John Murray, OCLC 4023508 online free

• Wolffe, John. "Wilberforce, William (1759–1833)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(2009)

https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/29386External links• Definitions from Wiktionary

• Media from Wikimedia Commons

• News from Wikinews

• Quotations from Wikiquote

• Texts from Wikisource

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Wilberforce, William .

• 200th Anniversary of the Abolition of the British and U.S. Slave Trade

• BBC historic figures: William Wilberforce

• BBC Humber articles on Wilberforce and abolition

• Wilberforce Institute for the study of Slavery and Emancipation

• "WILBERFORCE, William (1759-1833), of Hull, Yorks. and Wimbledon, Surr". The History of Parliament.

• Works by William Wilberforce at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about William Wilberforce at Internet Archive

• Works by William Wilberforce at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• William Wilberforce – The Great Debate on YouTube

• Wilberforce, BBC Radio 4 In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg (22 February 2007)