by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

Headlines

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

March 24, 2025

https://www.democracynow.org/2025/3/24/headlines

Columbia [University] Caves to Trump Demands, Outlines Plans to Militarize Campus, Reinforce Censorship

Mar 24, 2025

Education Secretary Linda McMahon said Columbia University is on track to regain $400 million in federal funding after the Ivy League institution yielded to the Trump administration’s demands Friday. Those include banning face masks on campus, hiring 36 new security officers with greater power to arrest and crack down on students and appointing a “senior vice provost” to oversee the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies and the Center for Palestine Studies.

Students say they will continue to fight for Palestinian rights and for Columbia to divest from Israel. Free speech experts are sounding the alarm. This is Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union.

Donna Lieberman: “Unfortunately, it appears that Columbia has capitulated to the bullying of the Trump administration and ceded significant control over academic decisions, like a couple of departments, admissions, discipline, to the Trump administration in return for the Trump administration backing off from its threat to cut off $400 million in grants that have absolutely nothing to do with claims of antisemitism or failure to deal with it.”

Students are returning to classes today after spring break. We will have more on this story later in the show.

Trump Orders DOJ and DHS to Punish Law Firms That Challenge His Agenda

Mar 24, 2025

On Friday night, President Trump issued a memo directing Attorney General Pam Bondi and Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem to punish law firms and lawyers that file what the administration views as frivolous or unreasonable lawsuits against the federal government. The memo is widely seen as a way to target immigration lawyers. Former Justice Department official Vanita Gupta said the memo “attacks the very foundations of our legal system by threatening and intimidating litigants who aim to hold our government accountable to the law and the Constitution.”

Meanwhile, a court battle continues over Trump’s use of the Alien Enemies Act to transfer over 130 Venezuelan men from the United States to El Salvador after they were accused of being gang members. An appeals court will hear oral arguments today on the case. On Friday, U.S. District Judge James Boasberg called Trump’s use of the law to be “incredibly troublesome and problematic.” The Trump administration is appealing Boasberg’s decision to halt flights under the Alien Enemies Act.

Trump to Revoke Temporary Status of 530,000 People from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela

Mar 24, 2025

The Trump administration has announced plans to revoke temporary immigration protections for more than 530,000 people from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela that were granted under a Biden-era humanitarian parole initiative known as CHNV.

WaPo: IRS Could Soon Release Personal Data of Immigrant Taxpayers to DHS

Mar 24, 2025

In other immigration news, The Washington Post is reporting the IRS is close to agreeing to a deal to give addresses and other personal information about suspected undocumented immigrants to the Department of Homeland Security. One former IRS official told the Post, “It is a complete betrayal of 30 years of the government telling immigrants to file their taxes.”

In other related news, DHS has shut down three internal watchdog agencies that advocated for immigrants, including the Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties.

U.S. Judge Blocks ICE from Deporting Activist Jeanette Vizguerra

Mar 24, 2025

A federal judge on Friday blocked Immigration and Customs Enforcement from deporting Jeanette Vizguerra, a well-known immigrant rights activist and mother of four, who was detained in Denver last Monday. U.S. Judge Nina Wang’s order also prevents federal authorities from transferring Vizguerra out of Colorado and gave the government a deadline of today to demonstrate why Vizguerra should not be released.

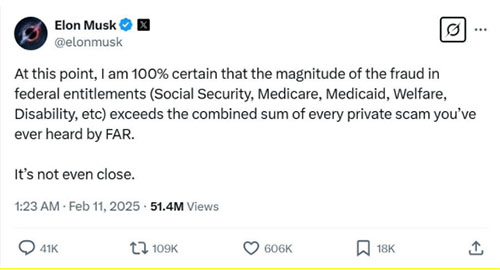

Social Security Head Briefly Threatens to Shut Down Agency

Mar 24, 2025

The head of the U.S. Social Security Administration threatened on Friday to shut down the agency and then backed down from the threat. Trump’s head of Social Security, Leland Dudek, made the initial threat after a federal judge blocked Elon Musk’s DOGE from accessing Social Security records, which the judge likened to a “fishing expedition.”

Meanwhile, Trump’s commerce secretary, billionaire Howard Lutnick, has sparked outrage after suggesting only fraudsters would complain if Social Security checks didn’t go out on time.

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick: “Let’s say Social Security didn’t send out their checks this month. My mother-in-law, who’s 94, she wouldn’t call and complain. She just wouldn’t. She’d think something got messed up, and she’ll get it next month. A fraudster always makes the loudest noise, screaming, yelling and complaining.”

Pentagon Hosts Elon Musk But Skips Briefing on China After Media Reports

Mar 24, 2025

Elon Musk visited the Pentagon Friday for a high-level meeting with Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and others. The New York Times had reported Musk was scheduled to receive a briefing on top-secret U.S. plans for a potential war with China, but the briefing was canceled after it was reported in the press. Musk threatened to go after whoever leaked what he called “maliciously false information” to the Times. Musk has close business ties with China, which is Tesla’s second-largest market. China is also the home of Tesla’s largest factory.

Musk’s PAC Offers Wisconsin Voters $100 as He Pours Millions into Key Supreme Court Race

Mar 24, 2025

Elon Musk’s political action committee is offering voters in Wisconsin $100 to sign a petition opposing what he calls “activist judges” ahead of Wisconsin’s Supreme Court election on April 1. Two Musk-backed groups have spent over $20 million on the race to support Republican Brad Schimel over Democrat Susan Crawford. The race will decide control of the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

FED UP Wisconsin Voters TURN AGAINST Trump at KEY TIME

MeidasTouch

Mar 29, 2025 The MeidasTouch Podcast

MeidasTouch host Ben Meiselas reports on Donald Trump and Elon Musk tanking in Wisconsin right before the key Supreme Court race takes place there and Meiselas speaks with Wisconsin Democratic Chair Ben Wikler about the Wisconsin Supreme Court race.

South African Ambassador Returns Home to Warm Welcome After Expulsion from D.C.

Mar 24, 2025

South African Ambassador Ebrahim Rasool returned home to a hero’s welcome Sunday after being expelled from Washington. Secretary of State Marco Rubio recently declared Rasool to be “persona non grata” in the latest move taken by the Trump administration against South Africa. Speaking in Cape Town on Sunday, Rasool criticized the Trump administration for cutting off aid to South Africa.

Ebrahim Rasool: “We have tried to engage. We have been met with executive orders that cut our aid, cut PEPFAR, and now we sit with the idea that millions could be reinfected with HIV and AIDS. The research for the vaccine may not be one that could be completed. Those are the dangerous things that are happening and why we must mend our relationship or sit out the next four years.”

Ambassador Rasool has also said South Africa will resist pressure from the U.S. and other nations to drop its genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice.

Canadian PM Calls for Snap Election to Take On Trump, “Most Significant Crisis of Our Lifetimes”

Mar 24, 2025

Canada’s new Prime Minister Mark Carney called on Sunday for snap federal elections to be held on April 28.

Prime Minister Mark Carney: “We are facing the most significant crisis of our lifetimes because of President Trump’s unjustified trade actions and his threats to our sovereignty. Our response must be to build a strong economy and a more secure Canada. President Trump claims that Canada isn’t a real country. He wants to break us so America can own us. We will not let that happen.”

Carney, a former central banker with little political experience, is hoping to consolidate his Liberal Party’s power after the popularity of the opposition Conservative Party soared during his predecessor Justin Trudeau’s final months in power.

Greenland Pushes Back on “Highly Aggressive” Planned Visit by Members of Trump White House

Mar 24, 2025

Greenland’s prime minister has expressed outrage over what he called the Trump administration’s “highly aggressive” plan to send second lady Usha Vance, national security adviser Michael Waltz and Energy Secretary Chris Wright to Greenland this week. Over the past two months, President Trump has repeatedly threatened to take control of Greenland “one way or the other.”

34,000 Rallygoers Attend Bernie and AOC’s Denver Stop on “Fighting Oligarchy” Tour

Mar 24, 2025

On Friday, an estimated 34,000 people gathered in Denver for a massive rally to hear Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Congressmember Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York as part of their “Fighting Oligarchy” tour. It was the largest rally of either of their political careers.

Sen. Bernie Sanders: “We will not allow America to become an oligarchy. This nation was built on working people, and we’re not going to let a handful of billionaires run the government.”

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez: “Power and corruption is taking over this country like never before. And we are here, most importantly, because we know that a better world is possible.”

Other speakers at the rally included Alvaro Bedoya, the federal trade commissioner who was fired by Trump last week.

**********************

Headlines

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

March 25, 2025

https://www.democracynow.org/2025/3/25/headlines

Trump’s National Security Team Accidentally Shares Yemen War Plans with Journalist in Signal Chat

Mar 25, 2025

In a stunning breach of security protocol, senior members of Trump’s administration unknowingly shared plans to bomb Yemen with a reporter on an unclassified Signal group chat. Jeffrey Goldberg, editor-in-chief of The Atlantic, revealed the chats in a piece titled “The Trump Administration Accidentally Texted Me Its War Plans.” Goldberg said he did not think the chat could be real until U.S. strikes actually did hit Yemen on March 15.

National security adviser Mike Waltz created the chat, which also included Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and Vice President JD Vance. Vance initially argued against the strikes, saying, “3 percent of US trade runs through the suez. 40 percent of European trade does.” Vance also messaged, “I am not sure the president is aware how inconsistent this is with his message on Europe right now,” before backing down. In response to the first wave of bombings, Waltz posted emojis of a fist, an American flag and fire. Over 50 people were killed during those U.S. strikes on Yemen, including children.

National security experts say using Signal to share classified information likely violates the Espionage Act and federal records law.

U.S. Attacks on Yemen Kills at Least 2 More People in Sana’a

Mar 25, 2025

The U.S. continues to attack Yemen after Houthi fighters threatened to renew strikes on Red Sea vessels over Israel’s resumption of its all-out war on Gaza. On Monday, U.S. airstrikes in Sana’a killed at least two people and wounded over a dozen others, including children. This is a local resident who witnessed the attack.

Hafezallah Saleh Al Hamidi: “A brutal American-Israeli aggression targeted civilians in a residential area that had no weapons or warehouses as the Americans claim, only innocent civilians. They bombed an empty basement with nothing in it. The residents of nearby buildings were harmed. Among them, people, and even children, were injured.”

Trump Threatens 25% Tariffs on Countries That Buy Venezuelan Oil

Mar 25, 2025

President Trump threatened Monday to impose 25% tariffs on any country that imports oil or gas from Venezuela. Trump claimed the move was in retaliation for Venezuela “purposefully and deceitfully” sending “criminals” and gang members to the U.S. Also on Monday, the Treasury Department extended Chevron’s oil production license in Venezuela until late May.

This comes as Trump appeared to retreat from his widely touted threats to impose sweeping tariffs across multiple industries starting April 2. He told reporters, “I may give a lot of countries breaks.”

USPS Chief Louis DeJoy Resigns as DOGE Prepares to Gut Agency

Mar 25, 2025

U.S. Postmaster General Louis DeJoy resigned from his post Monday. DeJoy, who has been head of USPS since 2020 in Trump’s first term, had recently signed a deal with DOGE to help gut the Postal Service, with plans to cut 10,000 workers and billions of dollars from its budget. Unionized postal workers have been out protesting amid reports Trump is attempting to privatize the USPS.

U.S. Judge Reaffirms Order Blocking Trump from Expelling Immigrants Using Wartime Order

Mar 25, 2025

A federal judge has kept in place a ruling that bars the Trump administration from using the Alien Enemies Act to summarily expel Venezuelan immigrants accused, without evidence, of being members of the Tren de Aragua gang. Judge James Boasberg said the order should allow the immigrants to fight the accusations in court.

In related news, Venezuela has announced it will resume accepting U.S. deportation flights amid mounting concerns of human rights violations after Trump officials expelled hundreds of Venezuelans to El Salvador’s maximum-security mega-prison without due process. Venezuela’s National Assembly President Jorge Rodríguez Gómez said, “Migrating is not a crime, and we will not rest until we accomplish the return of all who need it, and until we rescue our brothers [who] are kidnapped in El Salvador.”

Venezuelan immigrants have described harrowing conditions while in U.S. custody.

Venezuelan immigrant: “We have experienced many psychological, emotional and physical traumas, mistreatment in the conditions in which we were held in the facilities, how we were transferred and how we were treated in terms of health. They violated our rights. Many of those here were physically assaulted.”

Columbia Student and Green Card Holder Sues Trump Administration After ICE Attempts to Arrest Her

Mar 25, 2025

A 21-year-old Columbia University student on Monday filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration, which is seeking to deport her for participating in Palestinian rights protests on campus. Yunseo Chung is a legal permanent resident from South Korea who has lived in the U.S. since she was 7 years old. Federal immigration agents searched Chung’s university housing earlier this month as they attempted to arrest her. The Trump administration is targeting Chung under a rarely used provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which gives the secretary of state authority to begin deportation proceedings against any noncitizen deemed a threat to U.S. foreign policy interests — even permanent legal residents like Chung and Mahmoud Khalil, who was detained by federal agents from his Columbia housing earlier this month.

Yesterday, dozens of faculty members gathered to condemn Trump’s and Columbia’s attacks on free speech. This is political science professor Timothy Frye.

Timothy Frye: “Why do autocrats fear higher education? Why are they so hostile to the free expression of ideas? Well, universities are threatening to autocrats because we teach independent and critical thinking, because we train our students to scrutinize evidence and demand rigor, and because we teach students to be skeptical of authority, especially our own authority. If anyone thinks that we can brainwash Columbia students, they’ve never met a Columbia student.”

Click here to see our interview with former Columbia Law professor Katherine Franke.

***************

Headlines

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

March 26, 2025

Israel Kills 6 in Syria as U.S. Launches New Attacks on Yemen

Mar 26, 2025

In other news from the Middle East, an Israeli attack on southern Syria killed at least six people on Tuesday. Meanwhile, the United States reportedly launched another 17 strikes on Yemen. The U.S. has been carrying out near-daily strikes on Yemen after Houthi fighters threatened to renew attacks on Red Sea vessels after Israel broke the ceasefire in Gaza.

Waltz & Hegseth Face Calls to Resign Over Yemen Attack Plans Disclosure on Signal Chat

Mar 26, 2025

In Washington, D.C., several Democratic lawmakers are calling for Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and national security adviser Michael Waltz to resign, after they discussed plans to bomb Yemen on a Signal group chat. Waltz had set up the chat and then accidentally invited Atlantic editor Jeffrey Goldberg to join. On Tuesday, President Trump defended Waltz, saying he had learned his lesson and was a good man.

Democratic senators grilled Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard and CIA Director John Ratcliffe over their involvement in the Signal chat. This is Gabbard responding to a question from Democratic Senator Mark Warner of Virginia.

Tulsi Gabbard: “There was no classified material that was shared in that Signal chat.”

Sen. Mark Warner: “So, then, if there was no classified material, share it with the committee. You can’t have it both ways. These are important jobs. This is our national security.”

Tulsi Gabbard refused to say if she was on the group chat, even though there was a participant with the initials T.G. We’ll have more on this story later in the broadcast.

U.S. Intelligence Agencies Omit Climate Change as National Threat

Mar 26, 2025

Tulsi Gabbard and John Ratcliffe were testifying before the Senate in a hearing focused on the U.S intelligence community’s new annual threat assessment. The annual report cited fentanyl and international drug gangs as top threats to the country, but the report omits climate change as a major threat. This is independent Senator Angus King questioning Gabbard.

Sen. Angus King: “Who decided climate change should be left out of this report, after it’s been in the prior 11? Where was that decision made?”

Tulsi Gabbard: “I gave direction to our team at ODNI to focus on the most extreme and critical national security threats that we face.”

Sen. Angus King: “Did your direction include no comments on climate change?”

Tulsi Gabbard: “Senator, as I said, I focused on the most extreme and critical national security threats that” —

Sen. Angus King: “That’s not a response to my question.”

The Senate hearing was disrupted by the activist Tighe Barry of CodePink, who called on the United States to stop funding Israel.

Kash Patel: “Mr. Chairman, Mr. Vice Chairman” —

Tighe Barry: “The greatest threat to global security is Israel, and the whole world knows it!”

Sen. Tom Cotton: “Witness will suspend.”

Tighe Barry: “The greatest threat to global security is Israel, and the whole world knows it! Stop funding Israel! Stop funding Israel!”

A second CodePink activist, the retired Army colonel and former diplomat Anne Wright, was removed from the hearing and arrested after she stood up to dispute a claim by committee chair Tom Cotton that CodePink was funded by the Chinese government.

JD Vance to Join Delegation Headed to Greenland Amid Trump Threats to Seize Territory

Mar 26, 2025

Vice President JD Vance has announced in a social media video that he will join a high-level Trump delegation going to Greenland this week following President Trump’s threats to seize the semi-autonomous territory from Denmark.

Vice President JD Vance: “Speaking for President Trump, we want to reinvigorate the security of the people of Greenland because we think it’s important to protecting the security of the entire world. Unfortunately, leaders in both America and in Denmark, I think, ignored Greenland for far too long. That’s been bad for Greenland. It’s also been bad for the security of the entire world. We think we can take things in a different direction, so I’m going to go check it out.”

On the delegation, Vance will join his wife, second lady Usha Vance, national security adviser Michael Waltz and Energy Secretary Chris Wright. Greenland and Denmark have accused the United States of putting unacceptable and aggressive pressure on Greenland by sending the uninvited delegation.

ACLU Warns Trump Targeting of Another Law Firm Is “Despotic, Unpresidential”

Mar 26, 2025

The American Civil Liberties Union has accused President Trump of “despotic, unpresidential behavior” after he signed a new executive order targeting the law firm Jenner & Block — the sixth law firm hit with sanctions in recent weeks. The ACLU said, “This is part of a larger effort to knock out the pillars of a free society — journalists, universities, the legal profession and the courts.” Jenner & Block has been involved in several lawsuits against the Trump administration’s policies targeting transgender individuals and asylum seekers. Trump criticized the firm in part for once employing Andrew Weissmann, who served as lead prosecutor in Robert Mueller’s Special Counsel’s Office that investigated Trump’s ties to Russia.

In related news, The Washington Post reports many big law firms are now refusing to represent critics of Trump, including former Biden officials, out of fear the president may target their firms, as well.

AAUP & Middle East Studies Assoc. Sue Trump for Creating Climate of Repression on Campuses

Mar 26, 2025

The American Association of University Professors and the Middle East Studies Association have sued to block the Trump administration from arresting, detaining or deporting international students and faculty involved in Palestinian rights protests. One lawyer involved in the case accused the Trump administration of creating a “climate of repression and fear on university campuses across the country.”

In related news, a judge has blocked the Trump administration from deporting Yunseo Chung, a 21-year-old Columbia University student who participated in pro-Palestine demonstrations on campus. She is a legal permanent resident who has lived in the U.S. since she was 7 years old.

Salvadorans Protest U.S. Sending Venezuelans to “Imperial Prison”

Mar 26, 2025

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem is arriving in El Salvador today, where she will tour the maximum-security mega-prison complex detaining hundreds of Venezuelan immigrants and asylum seekers sent by the United States after the Trump administration accused them, without evidence, of being members of the Tren de Aragua gang. Human rights groups have documented gross violations at the mega-prison, built by the government of Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele in 2022 after he began enforcing a state of emergency. Protesters took to the streets of San Salvador on Tuesday.

Carolina Rivas: “We condemn the use of our land as an imperial prison and the attempt to turn our territory into free zones for neofascist experimentation. We demand the immediate release of all kidnapped Venezuelan migrants. We demand unrestricted respect for their human rights, due process and the right to migrate.”

On Monday, a U.S. federal judge condemned how the Trump administration expelled the Venezuelans to El Salvador without due process. U.S. Circuit Judge Patricia Millett said, “Nazis got better treatment under the Alien Enemies Act than has happened here.” She was citing how the wartime act was invoked during World War II.

UNAIDS Warns Millions Could Die from U.S. Aid Cuts

Mar 26, 2025

The head of UNAIDS is warning the withdrawal of U.S. foreign aid could lead to 2,000 new HIV infections every day around the world. UNAIDS chief Winnie Byanyima says millions could die if U.S. funding is not restored.

Winnie Byanyima: “There will be an additional, in the next four years, 6.3 million AIDS-related deaths — 6.3 million more in the next four years. At the last count, 2023, we had 600,000 deaths globally, AIDS-related deaths. So you’re talking of a tenfold increase.”

Report: DOGE Employee Known as “Big Balls” Once Helped Cybercrime Gang

Mar 26, 2025

Reuters has published a major exposé on one of Elon Musk’s top technologists at DOGE: the 19-year-old Edward Coristine, whose nickname is “Big Balls.” Reuters reports that beginning in 2022, the then-high-school student provided technical support to a cybercrime gang that cyberstalked an FBI agent and trafficked in stolen data.

Senate Committee Advances Nomination of Dr. Mehmet Oz, Backer of Privatizing Medicare

Mar 26, 2025

In other Trump news, the Senate Finance Committee has advanced the nomination of Dr. Mehmet Oz to head the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The former TV host and doctor has a long record of supporting the privatization of Medicare.

The Senate also held a confirmation hearing for Mike Huckabee, Trump’s pick to be U.S. ambassador to Israel. Huckabee is the former governor of Arkansas and a self-described Christian Zionist who has long supported Israel annexing the occupied West Bank.

Trump Signs New Voting Executive Order; Critics Warn Millions Could Be Disenfranchised

Mar 26, 2025

President Trump has signed a sweeping new executive order that would require proof of citizenship to register to vote. Voting rights advocates fear the move could disenfranchise tens of millions of voters. Trump’s order also aims to prohibit any votes from being counted after Election Day, including absentee ballots sent by mail. The ACLU has threatened to sue to block the order, which the group says marks a significant overreach of executive power.

*******************************

Headlines

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

March 27, 2025

ICE Agents Abduct Tufts Ph.D. Student in Escalating Crackdown on Anti-Genocide Campus Protests

Mar 27, 2025

Plainclothes immigration agents have detained another international student without warning, Turkish national and Tufts University Ph.D. student Rumeysa Ozturk. Surveillance video shows six masked agents approaching her on the streets of Somerville, Massachusetts, near her home Tuesday evening. She was with friends, making her way to a meal to break her Ramadan fast.

Tufts University’s president said the school had no prior notice of her arrest and that government officials said Ozturk’s student visa had been revoked. Last March, Ozturk co-wrote a piece in the student newspaper criticizing the Tufts administration’s response to Palestinian solidarity protests on campus which were calling for divestment from Israel. In a statement, Ozturk’s lawyer says she successfully filed a petition to block her client’s removal from Massachusetts, though ICE records indicate Ozturk was transferred to an immigration prison in Louisiana. Her lawyer, who as of yesterday evening had not spoken to her client, called the situation “incredibly bizarre and concerning.”

Over a thousand protesters poured into Powder House Square near the Tufts campus Wednesday. This is Lea Kayali of the Palestinian Youth Movement.

Lea Kayali: “We had hundreds of Bostonians coming out here today because they are angered about what happens when one of our community members was taken by armed agents of the state, who kidnapped her from outside of her home. People are here to stand up for the movement that she was punished for supporting, the movement for a free Palestine and to end the genocide in Gaza. And they’re also here to continue to support our immigrant neighbors, who have been getting picked up by ICE ever since, you know, not just Trump came into office, but Biden before him and every administration. So we are out here to continue to demand a free Palestine, to demand ICE out of our communities and to fight for collective liberation.”

ICE Detains Iranian Ph.D. Student in Alabama and Farmworker Union Leader in Washington

Mar 27, 2025

The detention of Rumeysa Ozturk comes just weeks after the arrest of Columbia graduate Mahmoud Khalil in New York. Another international student was detained by ICE this week: Alireza Doroudi, an Iranian doctoral student at the University of Alabama — though it’s not yet clear why he was targeted.

Meanwhile, in Washington state, authorities arrested farmworker union leader and well-known local immigrant rights activist Alfredo “Lelo” Juarez Zeferino. Protesters have gathered in front of Tacoma’s Northwest Detention Center, where he is being held, to demand his release.

DHS Sec. Noem Parades in Front of El Salvador Supermax Jail as U.S. Courts Block Trump Expulsions

Mar 27, 2025

Back in the U.S., a federal appeals court has denied a request by the Trump administration to lift an order blocking the president from expelling immigrants out of the United States using the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. The court order came on the same day that Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem visited the supermax prison in El Salvador housing over 200 men — mostly Venezuelans — who were sent there by the Trump administration in violation of a judge’s order. Human rights groups have long decried the inhumane conditions inside the Salvadoran prison. Noem posted a video, speaking in front of a group of prisoners.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem: “First of all, do not come to our country illegally. You will be removed, and you will be prosecuted. But know that this facility is one of the tools in our toolkit that we will use if you commit crimes against the American people.”

The Trump administration claims all of the Venezuelans sent to El Salvador were gang members, but the Miami Herald reports at least one of the men had just been granted refugee status weeks before.

Housing Dept. Collaborating with DHS to Identify Undocumented Residents in Subsidized Housing

Mar 27, 2025

In other immigration news, CBS News reports the Trump administration has paused the processing of green card applications for immigrants who had been granted refugee or asylum status.

Meanwhile, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD, has begun helping the Department of Homeland Security identify undocumented immigrants living in publicly subsidized housing.

Canada and several European countries have updated their travel advisories for the U.S. in recent days in response to Trump’s escalating crackdown on immigration and transgender rights.

White House Announces Scaled-Down Trip to Greenland Even as Trump Insists “We Need Greenland”

Mar 27, 2025

Members of Trump’s circle have scaled down a planned trip to Greenland on Friday, restricting their visit to a U.S. military base, after major backlash from Greenland and Denmark. Vice President JD Vance announced on Tuesday he would join his wife Usha Vance on the trip. It is unclear if national security adviser Mike Waltz and Energy Secretary Chris Wright are still going. On Wednesday, Trump reiterated his desire to take control over Greenland while speaking to the press.

President Donald Trump: “We need Greenland for national security and international security. So, we’ll — I think we’ll go as far as we have to go. We need Greenland, and the world needs us to have Greenland, including Denmark. Denmark has to have us have Greenland.”

SCOTUS Backs Regulations on Ghost Guns; Trump Tries to Cancel $65M Teacher-Training Grants

Mar 27, 2025

The U.S. Supreme Court voted 7 to 2 to uphold a Biden-era regulation that requires ghost guns to have serial numbers, be sold by licensed vendors, and for buyers to undergo a background check. Ghost guns are assembled by users from DIY kits that are typically sold online and had previously been untrackable.

In other Supreme Court news, the Trump administration has filed an emergency application seeking to cancel $65 million in congressionally appropriated teacher-training grants it says will be used for diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives.

“Capitulation Is the Wrong Way to Go”: Dir. Julie Cohen Resigns from duPont-Columbia Award Jury

Mar 27, 2025

In news from Columbia University, Oscar-nominated documentary filmmaker Julie Cohen has stepped down from the selection committee of the prestigious duPont-Columbia journalism awards. Cohen, who co-directed the documentary ”RBG,” said the decision came after Columbia “so readily caved to the Trump Administration.” Three other jurors joined Cohen in resigning Tuesday. Julie Cohen said in her resignation letter, “Any thoughtful analysis of how institutions respond to creeping authoritarianism makes it clear: capitulation is the wrong way to go.”

UC Davis Suspends Law Student Association over Its Vote to Divest from Israel

Mar 27, 2025

In California, UC Davis has suspended its Law Student Association and seized its funding in retaliation for the group’s vote backing the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement against Israel amid its war on Gaza.

USAID to Cancel Funding for Global Vaccine Alliance, a Possible Death Sentence for 1.2M Children

Mar 27, 2025

USAID is moving to end U.S. funding for Gavi, a global vaccine alliance that has procured lifesaving vaccines for millions of children in poor countries for decades. Other cuts planned by USAID in a newly shared document include anti-malaria initiatives. Less than 900 active employees are currently staffing the agency, down from 6,000 before the Trump administration. Over 5,000 USAID projects have been eliminated. The gutting of USAID programs is being challenged in the courts. Gavi estimates the withdrawal of U.S. funding could lead to more than 1.2 million child deaths from preventable diseases.

Calls Mount for Hegseth and Waltz Resignations as More Signal Chats from Yemen Attack Emerge

Mar 27, 2025

Calls for Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and national security adviser Michael Waltz to resign are increasing after The Atlantic magazine revealed both officials had discussed precise information about the U.S. bombing of Yemen on a group Signal chat that accidentally included Atlantic editor Jeffrey Goldberg. Hegseth posted detailed information on the timing and weapons used in the March 15 bombing. Waltz revealed the U.S. killed one target by bombing the building where the target’s girlfriend lived.

The White House has downplayed the growing scandal, describing it as a hoax while claiming no classified information was shared — a claim widely disputed by former intelligence officials. Several Republican lawmakers are now calling for an investigation.

During a House hearing Wednesday, Democratic Congressmember Raja Krishnamoorthi called for Hegseth to resign.

Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi: “This text message is clearly classified information. Secretary Hegseth has disclosed military plans, as well as classified information. He needs to resign immediately. He needs to resign immediately, and a full investigation needs to be undertaken with regard to whether other similar Signal chats are occurring in this administration.”

“Fire Elon, Not Elmo”: Democrats Ridicule GOP Hearing Aimed at Defunding Public Media

Mar 27, 2025

On Capitol Hill, far-right Republican Congressmember Marjorie Taylor Greene held a hearing Wednesday as part of a campaign to defund public media. She called NPR and PBS — whose heads were called in to testify — “radical left-wing echo chambers” with a “communist agenda,” as she attacked, among other things, LGBTQ+ programming.

Democrats on the panel highlighted Republicans’ hypocrisy and called to “Fire Elon, not Elmo,” in reference to the beloved children’s program “Sesame Street.” This is Texas Democrat Greg Casar.

Rep. Greg Casar: “My Republican colleagues don’t want to talk about the corporate waste, fraud and abuse, because those corporations fund the Republicans’ campaigns. So, instead, they want to shut down educational programming for kids and their families, and they want to shut down local radio stations. To borrow a phrase from 'Sesame Street,' the letter of the day is C, and it stands for 'corruption.'”

Trump Announces 25% Tariffs on Imported Cars and Auto Parts

Mar 27, 2025

Trump announced a new 25% tariff on imported cars and auto parts. It’s set to take effect April 2, which Trump’s been referring to as “liberation day.” The tariffs will also apply to U.S. brands that have been assembled outside the country. Consumers could see car prices shoot up by $4,000 to $12,000.

Kennedy Center Fires Social Impact Employees, Including Artistic Director Marc Bamuthi Joseph

Mar 27, 2025

The Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts has fired at least five members of its social impact team, including its artistic director, the renowned artist Marc Bamuthi Joseph. The team aimed to expand the art center’s reach to diverse audiences and to commission new works by Black composers. The job terminations come weeks after President Trump took over the Kennedy Center, named himself chair and fired most of the board of trustees. Marc Bamuthi Joseph recorded this video from his office after learning of his firing.

Marc Bamuthi Joseph: “Well, I am sitting in my office at the Kennedy Center one last time. It’s funny. I’m taking things down, like this red, black and green American flag and this extraordinary piece of artwork that my man Greg made that honors Stevie Wonder and this poster from BAM and a commemorative album that was organized by Swizz Beatz. Basically, I’m taking down everything Black in my office, just as the new leadership of the Kennedy Center is doing its best to disavow much of the literal color that has made this place special.”

Marc Bamuthi Joseph, speaking after being fired as artistic director of social impact at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, after President Trump took over as chair of the board. This past weekend, Marc Bamuthi Joseph performed his piece “Carnival of the Animals,” an allegory to January 6 and the insurrection. He performed it Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center here in New York.

************************

Headlines

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

March 28, 2025

https://www.democracynow.org/2025/3/28/headlines

Marco Rubio Says Rumeysa Ozturk Is One of “More Than 300” Visa Holders Targeted by Trump

Mar 28, 2025

Secretary of State Marco Rubio confirmed he revoked the visa of Rumeysa Ozturk, a Tufts Ph.D. student who was abducted on the streets of Somerville, Massachusetts, this week by plainclothes federal agents. Ozturk was targeted for writing a student op-ed about Tufts’s response to Gaza solidarity protests. Rubio told reporters her case is part of a much larger scheme.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio: “It might be more than 300 at this point. We do it every day. Every time I find one of these lunatics, I take away their visa.”

Hümeyra Pamuk: “You’re saying it could be more than 300 people?”

Secretary of State Marco Rubio: “Sure, I hope. I mean, at some point, I hope we run out because we’ve gotten rid of all of them. But we’re looking every day for these lunatics that are tearing things up. And by the way, we want to get rid of gang members, too.”

U.S. Court in New Jersey Hearing Arguments in Mahmoud Khalil Case

Mar 28, 2025

A federal court in Newark is hearing arguments from the lawyers of Mahmoud Khalil today as they argue for his case to be transferred to New Jersey and for his release from federal custody. Khalil, a former student protest leader at Columbia’s encampments, was first detained in New Jersey after he was arrested by ICE agents at his home in Manhattan earlier this month.

U.S. and Colombia [Govt.] Agree to Share Biometric Data of Immigrants

Mar 28, 2025

The U.S. has reached an agreement with the Colombian government that would allow the two countries to share biometric data collected from immigrants and asylum seekers. Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem praised the deal, claiming the measure would target members of criminal organizations. Colombia has become a hub for Venezuelan immigrants and others as they journey north to the United States. The agreement signals a major shift within the government of Colombian President Gustavo Petro, who had previously signaled he would not collaborate with Trump’s inhumane immigration crackdown.

Protesters in El Salvador Denounce Nayib Bukele’s Human Rights Abuses, Collaboration with Trump

Mar 28, 2025

In El Salvador, protesters took to the streets of the capital San Salvador to mark three years since President Nayib Bukele enacted a state of exception that limits constitutional protections and grants unlimited powers to Salvadoran armed forces to arrest people suspected of being gang members. The policy has also been used to target human rights advocates, land and water defenders, and others critical of Bukele’s government.

Some 85,000 Salvadorans have been arrested and jailed over the past three years, without due process, as their relatives demand their release. Human rights groups have documented gross violations, with dozens of Salvadorans reported dead in police custody. Tens of thousands are being indefinitely held at the same maximum-security mega-prison complex where the Trump administration unlawfully sent hundreds of Venezuelan immigrants and asylum seekers from the U.S.

Marcela Ramírez: “We condemn arbitrary actions taken by President Donald Trump and followed by de facto President Nayib Bukele. We think it’s a policy to criminalize poverty, a xenophobic policy. The fact that the Salvadoran state submits to these kinds of measures is an absurd submission to the criminalizing policy of the U.S.”

U.S. Escalates Yemen Airstrikes, Bringing Total Deaths Since March 15 to at Least 57

Mar 28, 2025

U.S. airstrikes pounded at least 40 locations across Yemen early today, including in the capital Sana’a, as the Trump administration continues its military campaign against the Houthis. At least seven people were injured, according to early on-the-ground reports. A coalition of advocacy groups — DAWN, Action Corps and Just Foreign Policy — are demanding an end to the U.S. attacks, saying they violate the U.N. Charter and that “Congress should stop strikes on Yemen and uphold its sole authority to declare war under Article I of the Constitution and the 1973 War Powers Resolution.” At least 57 people have been killed since the U.S. bombing started on March 15 after Houthi fighters said they would resume Red Sea cargo attacks over Israel’s renewed all-out war on Gaza.

U.S. Judge Orders Waltz, Vance, Rubio to Preserve Messages from Signal War Group Chat

Mar 28, 2025

Federal Judge James Boasberg has ordered top officials, including Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, national security adviser Michael Waltz, Vice President JD Vance and Secretary of State Marco Rubio, to preserve all communications sent on a Signal group chat in the lead-up to the March 15 attack on Yemen. The watchdog group American Oversight sued over the officials’ use of Signal for the exchange, which accidentally included the editor of The Atlantic. Attorney General Pam Bondi has indicated the Justice Department is not planning to investigate the matter despite growing bipartisan calls.

Meanwhile, Axios is reporting Minnesota Democrat Ilhan Omar is planning to introduce articles of impeachment against Pete Hegseth, Michael Waltz and CIA Director John Ratcliffe.

HHS Cutting 10,000 More Jobs as DOGE Carries Out Mission to Gut the Government

Mar 28, 2025

The Department of Health and Human Services announced it’s cutting 10,000 jobs. Combined with the wave of early retirements and buyouts since Trump came to power, the department will lose roughly a quarter of its workforce, going from 82,000 down to 62,000 employees. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said agencies will also be consolidated as part of the plan. The cuts will gut key agencies, including the CDC, FDA and NIH, and set back decades of advances in public health. Washington Democratic Senator Patty Murray said, “In the middle of worsening nationwide outbreaks of bird flu and measles, not to mention a fentanyl epidemic, Trump is wrecking vital health agencies with the precision of a bull in a china shop.”

This comes as a leaked White House memo shows the Trump administration is preparing to lay off between 8% to 50% of federal workers across 22 agencies under the “first phase” of DOGE cuts. The plan includes axing half the staff at Housing and Urban Development, 30% of staff at the IRS and 8% of Justice Department staff.

“We Can Eliminate an Entire District Court”: Mike Johnson Escalates Attack on Courts That Defy Trump

Mar 28, 2025

On Tuesday, House Speaker Mike Johnson escalated Republican attacks on judges and the court system, telling reporters Congress could attempt to “eliminate” federal courts it disagrees with.

Speaker Mike Johnson: “We do have authority over the federal courts, as you know. We can — we can eliminate an entire district court. We have power — funding over the courts and all these other things.”

Trump Withdraws Elise Stefanik Nom for U.N. Ambassador as GOP Frets Over Slim House Majority

Mar 28, 2025

President Trump on Thursday withdrew New York Congressmember Elise Stefanik’s nomination for U.N. ambassador, citing fears Republicans could come closer to losing their narrow margin in the House if Stefanik’s seat goes up for a special election. This comes after Pennsylvania Democrats won two state elections this week, including a Senate seat in a district that voted for Trump over Kamala Harris by more than 15 points in November. Republicans now hold 218 seats, Democrats have 213, and there are four vacant House seats.

New York County Clerk Refuses to Enforce Texas Penalty Against NY Abortion Provider

Mar 28, 2025

A New York county clerk refused to enforce a fine from Texas, issued to penalize a New York doctor for prescribing online abortion pills to a Texas patient. The Ulster County clerk cited New York state’s shield laws. The case is expected to eventually land at the U.S. Supreme Court.

Trump EO Orders Gov’t Agencies to End Collective Bargaining with Federal Unions

Mar 28, 2025

In labor news, Trump has signed an executive order stripping union rights from hundreds of thousands of federal workers, ordering 18 departments to stop engaging in any collective bargaining. Trump cited so-called national security concerns. The American Federation of Government Employees is challenging the order in court and said in a statement, “Trump’s threat to unions and working people across America is clear: fall in line or else. These threats will not work.”

EPA Created Email So Polluters Can More Easily Obtain Exemptions from Environmental Rules

Mar 28, 2025

The Environmental Protection Agency has created a direct email address for industrial polluters like coal-fired power plants to easily request exemptions from the federal government to Clean Air Act rules. The rules include limits on mercury production and other pollutants known to damage human health and the environment. Climate Action Campaign likened the process to a “gold-plated, 'get-out-of-permitting free' card.”

New Trump EO Aims to Gut Smithsonian Institution

Mar 28, 2025

In his latest attack on cultural institutions, President Trump signed an executive order Thursday appointing JD Vance to eliminate “divisive race-centered ideology” from Smithsonian museums, research centers and the National Zoo. The order, called “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” aims to remove exhibits and programs that portray U.S. history and values as “inherently harmful and oppressive.” It cites in particular the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opened in 2016. The Smithsonian operates independently since it was established as a public-private partnership by Congress in 1846. It receives roughly 60% of its funding from the federal government.