E. Conditions at B-18 and the Denial of Access to Counsel

72. James Pendergraph, former Executive Director of ICE Office of State and Local Coordination once said, “If you don’t have enough evidence to charge someone criminally but you think he’s illegal, we can make him disappear.”62 That ethos is animating Defendants’ Los Angeles operations today.

73. Individuals detained in immigration operations have a right to counsel that is rooted in the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. Usubakunov v. Garland, 16 F.4th 1299, 1304 (9th Cir. 2021); Biwot v. Gonzales, 403 F.3d 1094, 1098 (9th Cir. 2005); see also Torres v. United States Dep’t of Homeland Sec., 411 F. Supp. 3d 1036, 1060-61 (C.D. Cal. 2019). When the government detains individuals as part of immigration enforcement efforts, it cannot impose restrictions on access to attorneys that undermine the opportunity to obtain counsel or communicate with retained counsel. See Orantes-Hernandez v. Thornburgh, 919 F.2d 549, 554, 565 (9th Cir. 1990); see also Usubakunov, 16 F.4th at 1300 (“Navigating the asylum system with an attorney is hard enough; navigating it without an attorney is a Herculean task.”); Comm. of Cent. Am. Refugees v. INS, 795 F.2d 1434, 1439 (9th Cir. 1986) (recognizing that impediments to communication, especially in connection with a difficult-to-access facility, can constitute a “constitutional deprivation” where they obstruct an “established on-going attorney-client relationship.”).

74. Further, civil detainees have “a right to adequate food, shelter, clothing, and medical care.” Youngberg v. Romeo, 457 U.S. 307 (1982). Their conditions of confinement become unconstitutional if they “amount to punishment,” Bell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S. 520, 535 (1979), in other words, when “the harm or disability caused by the government’s action . . . significantly exceed[s], or [is] independent of, the inherent discomforts of confinement[.]” Demery v. Arpaio, 378 F.3d 1020, 1030 (9th Cir. 2004). During the ongoing raids, and as an integral part of the policy and pattern of unlawful stops and arrests described above, Defendants have been taking individuals who are swept up en masse to the basement of the federal building at 300 North Los Angeles Street in Los Angeles, commonly referred to as “B-18.” B-18 is a facility for immigrant detainees designed to hold a limited number of individuals temporarily so they can be processed and released, or processed and transported to a long-term detention facility. It does not have beds, showers, or medical facilities.

75. B-18 was previously the subject of litigation in this District, and a lawsuit over the inhumane treatment of detainees there resulted in a 2009 settlement agreement requiring that individuals not be held at B-18 for more than 12 hours. See Castellano v. Napolitano, No. 2:09-CV-02281 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 16, 2009). Other provisions of the agreement required that detainees at B-18 be allowed to “visit with current or prospective legal representatives and their legal assistants seven days a week, including holidays, for eight hours per day on regular business days (Monday through Friday), and four hours per day on weekends and holidays.”

76. The settlement agreement has since expired. But under the immense pressure to receive individuals arrested in recent weeks, the unlawful conditions that led to the settlement more than a decade ago are recurring today. Individuals taken to B-18 are being kept in overcrowded, inhumane conditions. They are held in small windowless rooms with dozens or more other detainees, in extremely cramped quarters. Some rooms are so cramped that detainees cannot sit, let alone lie down, for hours at a time.

77. As of June 20, 2025, upon information and belief, over 300 individuals were being held at B-18. They are expected to sleep in cold rooms on floors without cots, bedding, or blankets. Some are even forced to sleep in tents outside.

78. When asked why detainees have been forced to sleep in such cramped conditions, an officer at B-18 explained that B-18 is meant to be a processing center, not a detention facility. Historically, processing of individuals in removal proceedings would result in the release of an individual detained pending their next court hearing or, barring release, immediate transfer to a detention facility. But B-18 is not being used that way today, and individuals are being held there far longer than 12 hours, often for days on end.

79. Detainees are also routinely deprived of food. Some have not even been given water other than what comes out of the combined sink and toilet in the group detention room. And upon asking for food, detainees have been told repeatedly that the facility has run out.

80. Detainees are routinely denied access to necessary medical care and medications, too. Individuals with conditions that require consistent medications and treatment are not given any medical attention, even when that information is brought to the attention of the officers on duty. The facility cannot even provide detainees with basic hygiene. Individuals who are menstruating have had to wait long periods before receiving menstrual pads, if they receive them at all.

81. To make matters worse—and, indeed, to keep the true nature and scope of Defendants’ constitutional violations, including those related to stops and arrest, hidden from the outside world—individuals detained at B-18 have had their access to prospective or retained counsel severely and unconstitutionally restricted.

82. On June 6, 2025, attorneys and legal representatives from organizational Plaintiffs CHIRLA and ImmDef attempted to gain access to B-18 to advise detainees of their rights and assess their eligibility for relief, but they were not permitted to enter.

83. When they returned to B-18 the next morning, attorneys identified a handwritten notice on the door of the family and attorney entrance at B-18 indicating that they would not permit any visits that day. Federal officers then deployed an unknown chemical agent against family members, attorneys, and representatives, including CHIRLA and ImmDef legal staff, who were peacefully requesting access to detained individuals. The chemical agent that federal agents sprayed caused everyone to cough and inflicted a burning sensation in the eyes, nose, and throat.

84. That same morning, numerous unmarked white vans quickly departed B-18 with a group of detainees. CHIRLA and ImmDef attorneys and representatives attempted to loudly share know your rights information with the detainees in the vans. To prevent the detainees from hearing their rights, and therefore exercising them, the federal agents blasted their horns to drown them out.

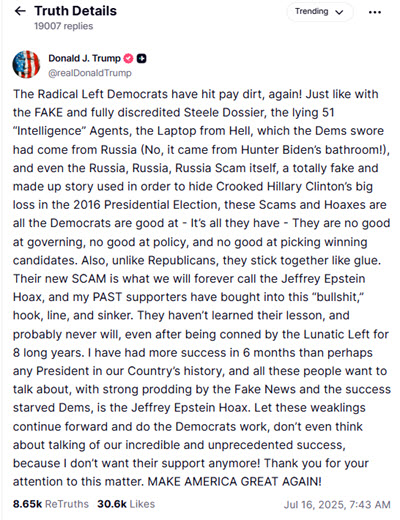

85. On June 7, 2025, another ImmDef attorney arrived at B-18 to find a handwritten notice that the facility was closed to visitation, as shown below:63

[x]

[x]

86. As a result, attorneys and family members were unable to access B-18 the entire weekend during the first few days of the raids.

87. On the rare occasions when attorneys and family members have been allowed access to their clients or loved ones, they have been made to wait hours at a time to see them, and the resulting visits have been limited to a mere five to 10 minutes. Detention officers screen the very limited phone calls that detainees are permitted to make, and phone calls cannot be used for confidential legal communications.

88. In many cases, attorneys and family members have been unable to determine whether a particular individual is even detained at B-18, or whether they have been transferred to another facility. B-18 officers have refused to provide clear answers to questions about detainees’ whereabouts, or refused to answer questions altogether. ICE’s online locator, which provides information about detainees’ location, is not updated in a timely manner.

89. The severe access restrictions have persisted as Defendants’ mass arrests continue to occur across Southern California.

90. On June 16, 2025, ImmDef attorneys, as well as Congressman Jimmy Gomez, arrived at B-18 around 3:00 p.m. on a day when B-18 was purportedly open for visiting between 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. But they were denied access, along with family members who had been instructed to go to B-18 to pick up their loved ones’ possessions.

91. On June 19, 2025, an ImmDef attorney arrived at B-18 to meet with detainees, including one who was scheduled for a chemotherapy appointment the next day. Despite showing a doctor’s note confirming the appointment and specifying that missing the appointment would be detrimental to the detainee’s health, the guards repeatedly would not allow the attorney to meet with the ill detainee. One officer told the attorney that he had no way to find the individual because hundreds of people were detained in the facility.

92. B-18 officers have and continue to consistently close the doors to detainees’ prospective or retained counsel at unexpected and unexplained times.

93. The use of B-18 as a makeshift, long-term detention center for hundreds of individuals has and continues to cause significant, ongoing harm. Defendants have intentionally restricted detainees’ access to those who may be able to intervene on their behalf at a critical time when they are likely to face imminent government action in their case. Indeed, one of ImmDef’s clients who has been granted asylum and who should never have been arrested was picked up at a Home Depot looking for work. He would have disappeared into the detention system if not for an ImmDef attorney’s last minute intervention at B-18 on June 19, 2025.

94. In fact, some individuals have accepted voluntary departure from this country under 8 U.S.C. § 1229c(a)(1), without having had the opportunity to consult with counsel, even though due process requires that any waiver of a right to a hearing be knowing and voluntary. See, e.g., United States v. Ramos, 623 F.3d 672, 682–83 (9th Cir. 2010). Upon information and belief, the inhumane conditions at B-18 create a coercive environment that pressures some of those detained individuals to take voluntary departure without first consulting with counsel and despite potential deportation relief because they fear lengthy detention in deplorable conditions.

95. Combined with the continued deplorable conditions at B-18—lack of food, medical care, basic hygiene, and overcrowding—B-18 is a disaster continuing to happen. And until these issues are resolved, the true scale of the legal violations Defendants are engaged in will remain unknown.

F. Defendants’ Pattern of Illegal Conduct Is Officially-Sanctioned

96. Defendants’ unlawful stops, arrests, denial of access to counsel and conditions at B-18 are the predictable result of directives from top officials to agents and officers.

97. In January, the administration gave ICE field offices an arrest quota of 75 arrests a day.64 As offices attempted to carry out such a mandate, workplace raids increased,65 ICE check-ins became traps,66 and courthouse arrests surged.67

98. Also, to help meet the quota, the administration granted agencies outside of DHS immigration enforcement powers.68

99. Meanwhile, the administration began systematically dismantling internal accountability mechanisms and restraints on immigration agents’ and officers’ conduct. The administration shut down multiple oversight agencies (retaining only a version of their former selves after the administration was sued).69 Investigations were closed.70 Officers no longer had to abide by enforcement priorities.71 Long-standing guidance restricting enforcement operations in sensitive locations—schools, hospitals, places of worship and public demonstrations—was rescinded.72

100. But these changes were not enough, according to the administration. In late May, Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller summoned 25 ERO Field Office Directors and 25 HSI Special Agents to a meeting to demand that “everybody” be targeted.73 Under Miller’s directive, agents no longer needed to develop vetted target lists of individuals suspected of being in the United States unlawfully.74 ICE agents were instructed in an email to “turn the creativity knob up to 11” and aggressively “push the envelope,” including by pursuing “collaterals”—individuals that by definition would not have warrants.75 As another e-mail put it: “If it involves handcuffs on wrists, it’s probably worth pursuing.”76

101. The administration set a new arrest quota of 3,000 arrests per day and reportedly threatened job consequences if officials failed to meet arrest quotas.77

102. The overriding message to agents and officers carrying out immigration operations on the ground was to prioritize arrest numbers, regardless of the law. Agents and officers were granted sweeping discretion to achieve this goal.

G. Defendant Agencies Have a History of Unconstitutional and Unlawful Conduct

103. The agencies involved in the Los Angeles area immigration raids include DHS and its components, ICE ERO, ICE HSI, and the U.S. Border Patrol, as well as DOJ law enforcement agencies including the FBI78 and others (including ATF79 and DEA).80 A number of these agencies have a history of engaging in unconstitutional and unlawful stops and arrests.

104. For example, the U.S. Border Patrol has a documented history of Fourth Amendment violations in the U.S. interior: U.S. Border Patrol agents have relied on perceived race or ethnicity to select who to stop, conducted suspicionless stops, executed warrantless home raids, and carried out illegal worksite operations. Courts have repeatedly intervened to curb these practices. See LaDuke v. Nelson, 762 F.2d 1318 (9th Cir. 1985), amended, 796 F.2d 309 (9th Cir. 1986), affirmed, 799 F.2d 547, 551 (9th Cir. 1986) (upholding permanent classwide injunction against warrantless raids on farmworker housing in Washington, Idaho, and Montana); International Molders’ and Allied Workers’ Local Union No. 164 v. Nelson, 643 F. Supp. 884, 887-89, 899-901 (N.D. Cal. 1986) (granting preliminary injunction barring the now-defunct Livermore Border Patrol Sector from replicating the unlawful practices it had used in “Operation Jobs,” a weeklong series of about 50 workplace raids across Northern California where agents stopped workers for questioning without reasonable suspicion and arrested people who refused to answer questions, including U.S. citizens).

105. Most recently, the El Centro Sector of the U.S. Border Patrol, one of the key participants in the raids being challenged in this suit, was the focus of a suit filed in the Eastern District of California over a Kern County operation called “Operation Return to Sender.” The tactics challenged here—including widespread racial profiling, suspicionless stops, and warrantless arrests without determination of flight risk—bear the unmistakable hallmarks of “Operation Return to Sender.”81 Like the raids challenged here, “Operation Return to Sender” spread through agricultural communities and also targeted day laborer pick up sites. On April 29, 2025, the court granted a preliminary injunction barring the U.S. Border Patrol from engaging in these unlawful practices. United Farm Workers v. Noem, No. 1:25-CV-00246 JLT CDB, 2025 WL 1235525, at *1 (E.D. Cal. Apr. 29, 2025). The ruling recognizes that, in the Ninth Circuit, “Hispanic appearance is of little or no use in determining which particular individuals among the vast Hispanic populace should be stopped.” Id. at *46 (quoting United States v. Montero-Camargo, 208 F.3d 1122, 1134 (9th Cir. 2000)). And the El Centro Sector Chief Bovino, who led “Operation Return to Sender,” is now at the helm of operations in the Los Angeles area, inviting him to replicate his tactics in this District.

106. ICE, which typically handles immigration enforcement in the interior and “manag[es] all aspects of the immigration enforcement process, including the identification, arrest, detention, and removal of [noncitizens],”82 has likewise been found to violate the Fourth Amendment, statutory, and regulatory rights of individuals it encounters in the field.

107. For instance, in 2008, ICE HSI agents conducted a workplace raid in Van Nuys, California. Agents executed a search warrant but also engaged in detentive stops of workers without individualized reasonable suspicion. The Ninth Circuit eventually ruled that this was unlawful and invalidated the ensuing removal proceedings. Perez Cruz v. Barr, 926 F.3d 1128, 1137 (9th Cir. 2019) (citing 8 C.F.R. § 287.8(b)).

108. In Nava v. DHS, a plaintiff class in Chicago challenged a pattern and practice of ICE conducting warrantless arrests without making required determinations under 8 U.S.C. § 1357. Nava v. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., 435 F. Supp. 3d 880, 885 (N.D. Ill. 2020). The case resulted in a settlement that included a nationwide policy about warrantless arrests and vehicle stops.83 In June 2025, despite a pending motion to enforce the settlement agreement and motion to extend the settlement agreement, ICE terminated its policy under the settlement that required officers to document the circumstances of warrantless arrests and vehicle stops.84

109. Meanwhile, in this District, in May 2024, plaintiffs secured a summary judgment order in Kidd v. Mayorkas, 734 F. Supp. 3d 967, 982 (C.D. Cal. 2024), holding unlawful ICE’s practice of entering onto the curtilage of homes during “knock and talks” for the purpose of carrying out arrests without a judicial warrant. Public reports confirm that in late May, Defendant Essayli, instead directed DOJ law enforcement agencies to take over door knocking tasks.85

110. In sum, Defendants in this case have demonstrated a willingness to bypass basic constitutional, statutory, and regulatory requirements when it comes to immigration enforcement, even before top-down pressure demanded adherence with dramatically higher arrest quotas. When their practices have come under scrutiny, rather than take the opportunity to conform their conduct to the law, they have evaded accountability by replicating those practices in another geographic area, declining to document what they do, and directing other federal partners not under court order to take over tasks that have been found to be unconstitutional. It is therefore no surprise that the immigration raids in the Los Angeles area have been marked by systematic disregard of the law.

H. Experiences of Individual Plaintiffs

Petitioner-Plaintiff Pedro Vasquez Perdomo

111. In the early morning of June 18, 2025, in Pasadena, California, Petitioner-Plaintiff Vasquez Perdomo was waiting at a bus stop across the street from Winchell’s Donuts with several co-workers to be picked up for a job.

112. Suddenly, about four cars converged on his location, and about half a dozen masked agents jumped out on either side of him. They had weapons and masks, and did not identify themselves.

113. To Petitioner-Plaintiff Vasquez Perdomo, it felt like a kidnapping. He tried to leave but was swiftly surrounded, grabbed, handcuffed, and put into one of the vehicles.

114. At the time he was handcuffed, agents did not have reasonable suspicion of a violation of immigration law.

115. It was only after he was brought to a nearby CVS parking lot that agents checked Petitioner-Plaintiff Vasquez Perdomo’s identification.

116. No warrant was shown. Upon information and belief, agents did not have a warrant of any kind for Petitioner-Plaintiff Vasquez Perdomo’s arrest.

117. Agents proceeded with a warrantless arrest of Petitioner-Plaintiff Vasquez Perdomo without making an individualized determination of risk of flight.

118. If agents had evaluated Petitioner-Plaintiff Vasquez Perdomo for risk of flight, they would have learned he had lived in Pasadena for decades.

119. Agents did not inform Petitioner-Plaintiff Vasquez Perdomo that they were immigration officers authorized to make an arrest or of the basis for his arrest.

120. At the time this action was filed, Petitioner-Plaintiff Vasquez Perdomo had been transported to and was being held at the federal building at 300 North Los Angeles St. in B-18. There he experienced extremely crowded and unsanitary conditions, was given little to eat or drink, and slept on the floor. Today he remains in custody at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center.

121. Petitioner-Plaintiff has representation in his removal proceedings. His counsel is located in Pasadena, California.

122. Petitioner-Plaintiff’s family is located in Pasadena, California.

123. Petitioner-Plaintiff is diabetic and has felt increasingly ill since his arrest. He has felt depressed since his arrest and reasonably fears being racially profiled again if he is released from detention.

Petitioner-Plaintiff Carlos Alexander Osorto

124. In the early morning of June 18, 2025, in Pasadena, California, Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto was waiting to be picked up for work with his co-worker Petitioner-Plaintiff Vasquez Perdomo.

125. When federal agents approached, Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto was terrified. He had seen videos of what had been happening around Los Angeles and also had heard of masked people who were not even government agents taking community members away. He tried to run, but one of the agents caught up to him and pointed a taser at his head and said “stop or I’ll use it!” Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto stopped immediately.

126. Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto was handcuffed and put into a vehicle.

127. At the time he was handcuffed, agents did not have reasonable suspicion of a violation of immigration law.

128. It was only after he was brought to a nearby CVS parking lot that agents asked Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto if he had papers.

129. No warrant was shown. Upon information and belief, agents did not have a warrant of any kind for Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto’s arrest.

130. Agents proceeded with a warrantless arrest of Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto without making an individualized determination of risk of flight.

131. If agents had evaluated Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto for risk of flight, they would have learned he had built homes all around Los Angeles, lived in Pasadena for more than a decade, and had 7 grandchildren who are U.S. citizens.

132. Agents did not inform Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto that they were immigration officers authorized to make an arrest or of the basis for his arrest.

133. At the time this action was filed, Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto had been transported to and was being held at the federal building at 300 North Los Angeles St. in B-18. The facility was full and when people asked for help officers told them there was no food, no water, and no medicine. Today he remains in custody at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center.

134. Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto has representation in his removal proceedings. His counsel is located in Pasadena, California.

135. Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto’s family is located throughout Los Angeles County, including in Pasadena, California.

136. Petitioner-Plaintiff Osorto has developed high blood pressure, he believes as a result of the stress he has experienced. He has been scared and overwhelmed by what happened and fears being targeted again, if he is released, for being a Latino person in construction clothes.

Petitioner-Plaintiff Isaac Antonio Villegas Molina

137. In the early morning of June 18, 2025, in Pasadena, California, Petitioner-Plaintiff Villegas Molina was waiting to be picked up for work with his co-workers Petitioner-Plaintiff Vasquez Perdomo and Petitioner-Plaintiff Alexander Osorto.

138. When federal agents approached, Petitioner-Plaintiff Villegas Molina was also afraid but tried his best to stay calm.

139. An agent yelled at Petitioner-Plaintiff Villegas Molina not to run, even though he was still and calm. He was told to provide his ID and he provided his California ID, but the agent kept questioning him. At this point, he did not feel free to leave.

140. When they were questioning him, agents did not have reasonable suspicion of a violation of immigration law.

141. No warrant was shown. Upon information and belief, agents did not have a warrant of any kind for Petitioner-Plaintiff Villegas Molina’s arrest.

142. Agents proceeded with a warrantless arrest of Petitioner-Plaintiff Villegas Molina without making an individualized determination of risk of flight.

143. If agents had evaluated Petitioner-Plaintiff Villegas Molina for risk of flight, they would have learned he had lived in Pasadena for 13 years and had worked at restaurants across Los Angeles.

144. Agents did not inform Petitioner-Plaintiff Villegas Molina that they were immigration officers authorized to make an arrest or of the basis for his arrest.

145. At the time this action was filed, Petitioner-Plaintiff Villegas Molina had been transported to and was being held at the federal building at 300 North Los Angeles St. in B-18. He slept on the floor and was given almost nothing to eat. Today he remains in custody at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center.

146. Petitioner-Plaintiff has representation in his removal proceedings. His counsel is located in Pasadena, California.

147. Petitioner-Plaintiff has had a difficult time in detention. He fears being targeted again because of his race.

Plaintiff Jorge Hernandez Viramontes

148. On the morning of June 18, 2025, Plaintiff Hernandez Viramontes was working at a car wash in Orange County, where he has worked for approximately 10 years, when immigration agents arrived. This was the third time that agents had raided the carwash since June 9, 2025. 149. During this visit by agents, like with previous visits, agents did not identify themselves. They did not show a warrant. They simply went from person to person interrogating them about their identity and immigration status.

150. Agents questioned Plaintiff Hernandez Viramontes’ co-worker, a U.S. citizen, about his citizenship three separate times in one visit.

151. When agents got to Plaintiff Hernandez Viramontes, they asked him if he was a citizen, and he replied yes and explained he was a dual citizen of the U.S. and Mexico. They asked for an ID, which he provided. Agents then explained that his ID wasn’t enough and since he didn’t have his passport, they were taking him.

152. Agents placed Plaintiff Hernandez Viramontes in a vehicle and transported him away. During this time, Plaintiff Hernandez Viramontes did not know if they were going to take him to a detention center.

153. Agents verified his citizenship and about 20 minutes later, brought him back to the car wash, but not before his brother called his wife, who had become deeply worried.

154. When agents brought Plaintiff Hernandez Viramontes back to the car wash, they did not apologize.

155. Shortly after agents returned Plaintiff Hernandez Viramontes to the car wash, yet another group of agents raided the carwash again.

156. Plaintiff Hernandez Viramontes is shaken by what happened and fears being targeted again on the basis of his Latino appearance and accent.

Plaintiff Jason Brian Gavidia

157. In the afternoon of June 12, 2025, Plaintiff Gavidia, a U.S. citizen, was at a tow yard in Los Angeles County that was visited by immigration agents conducting a roving patrol.86

158. Around 4:30 p.m., upon hearing someone say immigration agents may be at the premises, Plaintiff Gavidia went outside to confirm this. At the time, his clothes were dirty from working on his car.

159. On the sidewalk outside the gate, Plaintiff Gavidia saw a federal agent between two cars step forward. Soon after, Plaintiff Gavidia saw several other agents wearing similar vests with the words “Border Patrol Federal Agent.” He also noticed the agents were carrying handguns and at least two of the agents had a military-style rifle.

160. As Plaintiff Gavidia attempted to head back inside the tow yard premises, an agent said, “Stop right there.” At this point, Plaintiff Gavidia did not feel that he could leave. The agent was masked.

161. While the agent approached Plaintiff Gavidia, another unmasked agent ran towards him and asked if he was American. Plaintiff Gavidia told the agent that he is American multiple times. The agent responded by asking, “What hospital were you born in?” Plaintiff Gavidia calmly replied that he did not know. The agent repeated the same question two more times, and each time Plaintiff Gavidia provided the same answer. At that point, the agents forcefully pushed Plaintiff Gavidia up against the metal gated fence, put his hands behind his back, and twisted his arm. Plaintiff Gavidia had been on his phone, and the masked agent also took his phone from his hand at that point.

162. Plaintiff Gavidia explained that the agents were hurting him and that he was American. The unmasked agent asked a final time, “What hospital were you born in?” Plaintiff Gavidia responded again that he did not know and said East L.A. Plaintiff Gavidia then told the agents that he could show them his Real ID. The agents had not asked to see Plaintiff Gavidia’s identification.

163. When Plaintiff Gavidia showed his Real ID to the agents, one of them took it from him. It ultimately took about 20 minutes for -Plaintiff Gavidia to get his phone back. But the agents never returned Plaintiff Gavidia’s Real ID.

164. Plaintiff Gavidia’s interaction with the federal agents was one of the worst experiences he has ever had. He is disturbed and deeply concerned about being targeted again because of his race.

I. Harms to Organizational Plaintiffs and/or Their Members

165. Since they began on June 6, 2025, federal immigration raids have led to the arrest of over 1,500 people and counting, many of whom have been stopped without reasonable suspicion, and/or arrested without probable cause. For those who have been arrested, many have been denied the right to consult with their attorneys, and have been held under conditions with insufficient food, shelter, clothing, and medical care. These conditions, of both arrests and detentions, have caused profound harm to individuals and families, and destabilized entire communities. The chilling effect extends beyond directly impacted individuals. For example, the Mayor of Pasadena described seeing a “huge drop in attendance at local community programs,” once “vibrant neighborhoods” now “eerily quiet” and business owners “concerned that their workers and customers alike are too afraid to show up.”87

166. These harms have extended to organizational Plaintiffs and/or their members.

Plaintiff Los Angeles Worker Center Network (LAWCN)

167. LAWCN is a regional organization made up of eight worker centers and labor organizations that work together to build power and develop worker leadership organizing with Black, immigrant, and refugee workers and other workers of color in the Los Angeles region. LAWCN’s member organizations work to improve conditions in low-wage industries, including car wash, garment, home care, restaurant, retail, warehouse, and other low-wage sectors. LAWCN’s members each have at least one representative on its Executive Committee, and the Committee has regular standing meetings in which the member organizations provide input on LAWCN’s strategic planning and goals, including by having the voting members cast votes on key strategic questions.

168. LAWCN improves conditions for low-wage workers through capacity building, organizing, services, and policy advocacy at the city, county, and state level. In pursuing LAWCN’s mission to build the power and grow the capacity of local worker centers to organize and advocate for low-wage workers, LAWCN has a long term and sustained focus on issues related to immigration and immigrant workers. LAWCN has engaged in policy reform and advocacy aimed at increasing immigrant workers’ access to governmental services. Additionally, through its capacity-building efforts, LAWCN’s work supports immigrant justice by improving the conditions and dignity of immigrant workers in Southern California.

169. LAWCN brings this suit on behalf of its member organizations, worker centers that organize and advocate for low-wage workers in the greater Los Angeles region. At least one of LAWCN’s member organizations, CLEAN Carwash Worker Center (CLEAN), has been harmed by the ongoing raids in Southern California. CLEAN is a grassroots worker center that fights for the self-determination of immigrant and working-class people by empowering carwash workers to make lasting changes in the carwash industry and their communities.

170. CLEAN has approximately 1,800 members who are carwash workers from the greater Los Angeles area. Its members are predominantly Latino and many are immigrants or the children of immigrants. CLEAN has three tiers of membership available to workers, depending on how much each member wishes to participate in CLEAN’s organizing work. CLEAN’s members help set the priorities for the organization. It holds standing membership meetings during which members provide feedback and input into CLEAN’s goals and work.

171. CLEAN’s mission includes fighting for the self-determination of immigrants. A consistent focus of CLEAN’s work is to provide its members access to immigration-related support and resources. Some of this work involves providing training and support to members about immigration issues. CLEAN has also organized programming and events, including attending rallies and events, in support of immigration reform.

172. Carwashes have been a consistent and ongoing target of immigration agents during the course of the raids—at least two dozen have been raided so far.88 Some carwashes have closed because so many workers have either been detained or fear future raids.89

173. Dozens of CLEAN’s members have been detained by immigration agents while at work. At least one identifiable CLEAN member, Jesus Aristeo Cruz Utiz, has been subjected to Defendants’ unlawful stop and arrest practices.

174. Many CLEAN members, regardless of the stability or permanence of their immigration status, fear that immigration agents will subject them to unlawful stops and arrests. They are terrified that masked and unidentifiable immigration agents will invade their workplaces without a warrant, grab them, handcuff them, and take them away. They are fearful of being racially profiled and stopped by immigration agents while in public or at their places of employment.

Plaintiff United Farm Workers (UFW)

175. Founded in 1962 by Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, Larry Itliong and other labor leaders, UFW is the largest farm worker union in the country. UFW’s mission is to improve the lives, wages, and working conditions of agricultural workers and their families. UFW is dedicated to the cause of eliminating discrimination against farm workers, immigrants, people of color, and any other groups that have been the target of unfair or unlawful treatment. As part of this work, UFW is a national leader in the movement for immigration reform and immigrants’ rights.

176. UFW has approximately 10,000 members. California is home to more UFW members than any other state, with members in counties across the Central District of California, such as Los Angeles County, Orange County, Riverside County, Ventura County, and San Bernardino County. UFW membership is voluntary and consists of various categories of members. Among these, contributing or associate members are individuals who make a monthly or annual contribution of a designated amount to UFW. Dues-paying members are those who benefit from a UFW collective bargaining agreement.

177. UFW members play an important role in deciding what activities UFW engages in as an organization. At the UFW’s quadrennial Constitutional Convention, members introduce and vote on motions to govern and guide the union’s work, and to elect the Union Executive Board. On an ongoing basis, UFW members respond to surveys, provide feedback, and participate in advisory meetings (known as “consejo de base” in Spanish) to actively participate in the Union’s decisions. UFW has created various programs in response to members’ feedback and requests.

178. UFW membership comes with a variety of benefits. Dues-paying members receive protections from collective bargaining in which UFW engages on their behalf. Contributing or associate members (also called “direct” members) receive UFW photographic identification, accidental life insurance of $4,000, access to UFW discounts with private businesses, and other benefits. For services that prioritize agricultural workers, UFW direct membership establishes membership.

179. UFW brings this action on behalf of its members. UFW’s members have been harmed by the ongoing immigration raids in Southern California and fear being subjected to unlawful stops, arrests, and detention practices in the future. At least one UFW member—Angel—has been subjected to Defendants’ stop and arrest practices.

180. Despite UFW’s lawsuit against DHS and the Border Patrol, filed on February 26, 2025,90 these concerns remain today.

181. Many UFW members, regardless of the stability or permanence of their immigration status, fear that immigration agents will continue to subject farm workers and day laborers to unlawful immigration stops and arrests, especially those who appear non-white. These members face irreparable harm from Defendants’ unlawful practices.

Plaintiff the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA)

182. CHIRLA was founded in 1986, and its mission is to advance the human and civil rights of immigrants and refugees. CHIRLA ensures immigrant communities are fully integrated into our society with full rights and access to resources.

183. As a membership organization, CHIRLA has approximately 50,000 members across California, including both U.S. citizens and noncitizens of varying immigration status. CHIRLA has members in every county in this District. Many of CHIRLA members are day laborers, car wash workers, and street vendors. CHIRLA’s membership is predominantly Latino.

184. CHIRLA is the largest statewide immigrant rights organization in California, with over 185 staff members who provide services to thousands of Californians each year. Its legal department has assisted approximately 30,000 people with direct services and legal education, including numerous CHIRLA members.

185. Some of CHIRLA’s members pay dues to the organization, and those dues help fund the organization’s operations. Other CHIRLA members have become members by virtue of their participation in the organization’s meetings, programs, and policy campaigns.

186. CHIRLA’s members regularly meet with each other in regional committees. Committee meetings can range from a small handful of people to hundreds. In addition, CHIRLA’s student members hold regional statewide conference calls and meetings throughout the year. During these meetings, CHIRLA’s members plan local advocacy campaigns, share information, and discuss issues that affect them, their families, and their local communities. Information from these meetings is reported to CHIRLA’s leadership and used to guide CHIRLA’s programmatic agenda.

187. CHIRLA also holds quarterly membership retreats at which coreleaders discuss issues they are seeing in their communities and set priorities for the organization.

188. CHIRLA also coordinates the Los Angeles Rapid Response Network (LARRN) and educates its membership as well as the broader community through know your rights programming, workshops, social media, and educational literature about a variety of social services and benefits, including immigration law, financial literacy, workers’ rights, and civic engagement. CHIRLA is often a first point of contact for individuals seeking direct assistance and accurate information about policy changes impacting immigrants.

189. CHIRLA brings this action on behalf of its members who reasonably fear being subject to the stop and arrest practices challenged in this case and subsequent detention at B-18. Since immigration authorities began arresting and detaining predominately Latino people across Southern California, including in places where CHIRLA members live and go, they have become terrified that they too will be taken from their families and communities. Indeed, some CHIRLA members, including those with legal status, have begun carrying around their passports, have refrained from being at bus stops, and have reduced how much they go out in public because they are afraid of being stopped and detained unlawfully.

190. As a result of Defendants’ actions, CHIRLA’s mission to serve the immigrant community, including through the provision of legal advice and services, is being frustrated. Throughout the last month, CHIRLA’s attorneys and representatives have attempted to communicate with individuals at B-18, were denied access, and were thwarted in their efforts to offer legal advice to even those detainees they saw at a distance as government officials used car horns to drown them out. Defendants’ actions are also thwarting CHIRLA’s work to coordinate the LARRN as other attorneys and representatives summoned by CHIRLA to B-18 have been similarly denied access.

Plaintiff Immigrant Defenders Law Center (ImmDef)

191. ImmDef was founded in 2015 with the mission of protecting the due process rights of immigrants facing deportation. At its inception, it sought to achieve this goal through implementation of the universal representation model—i.e., ensuring that every immigrant appearing before the immigration court was represented by an attorney. ImmDef is now the largest removal defense nonprofit organization in Southern California, providing full-scale deportation defense, legal representation, legal education, and social services to approximately 30,150 detained and non-detained children and adults annually.

192. ImmDef’s Welcoming Project provides “Know Your Rights” trainings throughout ImmDef’s service area, which includes the counties of Los Angeles, Orange, Kern, Riverside, San Bernardino, and San Diego. These trainings aim to educate immigrant community members about the immigration system and about their due process and civil rights.

193. ImmDef’s Rapid Response team is also part of LARRN, with CHIRLA, and monitors a hotline and responds to notifications about individuals detained in enforcement actions. When possible, ImmDef takes referrals to represent detained individuals in their removal proceedings within ImmDef’s service area. If ImmDef is unable to represent an individual referred through LARRN, ImmDef attempts to connect that individual with pro bono representation.

194. ImmDef’s attorneys and representatives have been denied access to people in detention, including those being held at B-18. As a result of Defendants’ actions, ImmDef’s mission to serve the immigrant community, including through the provision of legal advice and services, is being fundamentally frustrated.

J. Defendants’ Illegal Conduct Will Continue if Not Enjoined

195. The federal government has repeatedly made clear its intent to continue its operations and unlawful stops, arrests, and detentions. Defendants have been candid about their determination to continue pursuing these unlawful policies and practices, unless this Court enjoins them from doing so.

196. Indeed, federal officials have been open about the ongoing and expanding nature of these unlawful immigration raids.

197. White House official Tom Homan recently maligned Los Angeles as a sanctuary city and vowed, “We’re going to send a whole boatload of agents. . . . We’re going to swamp the city.91 He has stated, “This operation is not going to end,”92 and, “Every day in LA we’re going to enforce immigration law. I don’t care if they like it or not.”93 Kristi Noem has also said, “We’re going to stay here and build our operations until we make sure that we liberate the city of Los Angeles.”94 Noem told agents “your performance will be judged every day by how many arrests you, your teammates and your office are able to effectuate. Failure is not an option.”95

198. While immigration enforcement may be done lawfully, these statements demonstrate a commitment to continue operations at any cost, including at the expense of individuals’ constitutional and legal rights. Plaintiffs have already been harmed, and they face a reasonable likelihood of continuing harm, as a result of Defendants’ unlawful policies and practices described herein. Plaintiffs have no plain, adequate, or complete remedy at law to address the wrongs described herein. Injunctive and declaratory relief is necessary to redress their ongoing injuries.

CLASS ACTION ALLEGATIONS

199. The Stop/Arrest Plaintiffs bring this action on behalf of themselves, and in the case of the organizational Stop/Arrest Plaintiffs, their members. In addition, the Stop/Arrest Plaintiffs bring this action under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 23(a) and (b)(2), on behalf of classes of persons similarly situated to themselves and their members. Plaintiffs seek to represent three classes of individuals who have been or will be subjected to several of the unlawful practices this lawsuit challenges: suspicionless stops; warrantless arrests without evaluations of flight risk; and the failure to identify authority and the reason for arrest.

The Suspicionless Stop Class

The Stop/Arrest Plaintiffs seek to represent a class under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 23(b)(2) consisting of:

All persons who, since June 6, 2025, have been or will be subjected to a detentive stop by federal agents in this District without a pre-stop, individualized assessment of reasonable suspicion concerning whether the person (1) is engaged in an offense against the United States or (2) is a noncitizen unlawfully in the United States.

200. Numerosity. The proposed class meets the numerosity requirements of Rule 23(a)(1) because it consists of a large number of similarly situated individuals located within this District, such that joinder of all members of the class is impracticable. Although the number of individuals who have been or will be subject to unconstitutional detentive stops by federal agents is not known with precision, class members number in the thousands. Since June 6, 2025, federal agents have arrested more than 1,500 people within the District, and likely conducted unconstitutional detentive stops on many more.

201. Common Questions of Law and Fact. The proposed class meets the commonality requirements of Rule 23(a)(2) because all members of the proposed class have been or will be subjected to the same unconstitutional practices. Thus, there are numerous questions of law and fact common to the proposed class, which predominate over any individual questions, including:

(a) Whether Defendants have a policy, pattern, or practice of conducting stops without regard to whether reasonable suspicion exists that the person

(1) is engaged in an offense against the United States or (2) is a noncitizen unlawfully in the United States; and

(b) Whether Defendants’ policy, pattern, or practice of conducting stops without regard to whether reasonable suspicion exists that the person (1) is engaged in an offense against the United States or (2) is a noncitizen unlawfully in the United States violates the Fourth Amendment or applicable regulations.

The Warrantless Arrest Class

202. The organizational Stop/Arrest Plaintiffs—LAWCN, UFW, and CHIRLA—also seek to represent a class consisting of:

All persons, since June 6, 2025, who have been arrested or will be arrested in this District by federal agents without a warrant and without a pre-arrest, individualized assessment of probable cause that the person poses a flight risk.

203. Numerosity. The proposed class meets the numerosity requirements of Rule 23(a)(1) because it consists of a large number of similarly situated individuals located within this District, such that joinder of all members of the class is impracticable. Although the number of individuals who have been or will be subject to unlawful warrantless arrests by Defendants is not known with precision, class members number in the thousands. Since June 6, 2025, federal agents have arrested more than 1,500 people within the District, with no indications of possessing a warrant or conducting any sort of pre-arrest, individualized assessment of probable cause that the person poses a flight risk.

204. Common Questions of Law and Fact. The proposed class meets the commonality requirements of Rule 23(a)(2) because all members of the proposed class have been or will be subjected to the same unconstitutional practices. Thus, there are numerous questions of law and fact common to the proposed class, which predominate over any individual questions, including:

(a) Whether Defendants have a policy, pattern, or practice of conducting warrantless arrests without probable cause that an individual is likely to escape before a warrant can be obtained for the arrest;

(b) Whether Defendants’ policy, pattern, or practice of conducting stops without probable cause that an individual is likely to escape before a warrant can be obtained for the arrest violates 8 U.S.C. § 1357(a)(2); and

(c) Whether Defendants’ policy, pattern, or practice of conducting stops without probable cause that an individual is likely to escape before a warrant can be obtained for the arrest violates 8 C.F.R. § 287.8(c)(2)(ii).