by Sean Parker

June 27, 2013

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Editor’s note: Sean Parker is the executive general partner at Founders Fund. Previously he was co-founder of Napster, as well as the founding president of Facebook. He currently serves as a director of Spotify. Follow him on Twitter @sparker.

Our Wedding

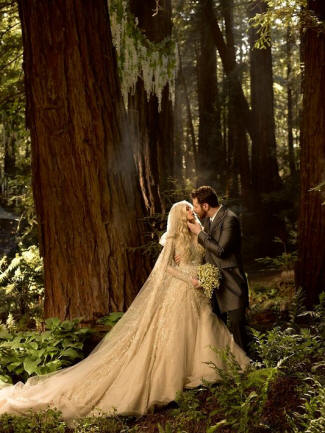

My wife Alexandra and I met five years ago, fell in love, and almost immediately began fantasizing about our wedding day, which, we both agreed, should take place deep within an enchanted forest. (You know, sort of like Lothlórien, the mythical home of Galadriel in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.) We wanted our wedding to begin with “Once upon a time…” and end with “…and they lived happily ever after.” But life rarely works out the way it does in fairy tales, as much as we hoped it would. The story I’m about to tell, ironically, begins where many fairy tales end: with a wedding.

On the day of our wedding, our friends and family walked by foot down a long winding path to the ceremony site. With each step the landscape grew ever more magical, more lush, and more surreal. Eventually our guests reached a beautiful gate in a clearing, just prior to entering the forest. Through that threshold, they left the ordinary world behind and entered an extraordinary world imagined as a kind of collaborative art project between me and my wife-to-be, Alexandra.

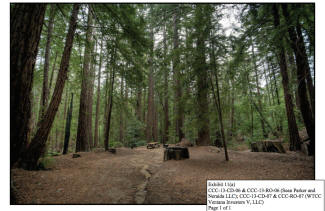

We wanted our wedding to be spiritual, though not overtly religious. Everyone is familiar with man-made cathedrals, but there is another kind of cathedral, built by God. In many old growth forests, redwood trees naturally grow in a circular configuration around the nutrient-rich soil where a dead tree once stood. Standing inside these clusters of trees, engulfed on all sides by the forest canopy, it’s hard not to be moved by the majesty of this natural “cathedral,” an ancient setting of unparalleled beauty.

We spent the better part of two years hiking through redwood forests all over California, trying to find the perfect spot for our wedding. Finding an old-growth redwood grove suitable for a wedding is no easy task. We enlisted the help of Save the Redwoods League, a noted conservation group, to help identify an appropriate site and also to provide advice on how to avoid harming the natural redwood habitat. With their guidance, we ultimately settled on a redwood grove within the campground of the Ventana Hotel & Spa in Big Sur, chosen largely because the site had already been developed, thereby minimizing the impact on the forest and avoiding the issue of a large number of guests trampling a “pristine” forest.

The vision for our wedding was to integrate with nature as much as possible — to bring out the natural beauty of the site while incorporating the kinds of modern amenities that one needs at a wedding. Because we wanted to avoid any harm to the forest, we asked the league to send their Director of Science, Emily Burns, down to the site to advise our landscape architect on “best practices” for working within the forest.

After the ceremony many of us felt as though we never wanted to leave that forest, and indeed many guests remained there until the sun came up the next morning. We lay on the flower-strewn pathway, looking up at the redwood canopy above. The fog rolling in from the ocean enveloped us, imbuing the moment with a feeling of supernatural bliss.

The Monday after our wedding we woke up in our hotel room, newly married, and still buzzing from the most exciting day of our lives. With all the stresses and anxieties of wedding planning behind us, we were finally ready to relax, take a deep breath of ocean air, and enjoy the romance of being together in Big Sur. Many of our friends who lingered recounted their memories of the wedding, describing the event using words like “beautiful,” “tasteful,” “enchanted,” “epic,” and “a fantasy.” There was a kind of magic in the air, and most newlywed couples would have been free to bask in the afterglow of that moment.

The Aftermath

We were not so lucky.

We awoke that morning to a media backlash of epic proportions, a firestorm of press attacking our wedding with the most vitriolic language we’d ever seen in print. At the same time, a mob of Internet trolls, eco-zealots, and other angry folk from every corner of the Internet unleashed a fury of vulgar insults, flooding our email and Facebook pages.

This was the sort of angry invective normally reserved for genocidal dictators.

These reactions were so extreme, so maniacal, so deeply drenched in expletives, they seemed wasted on us; this was the sort of angry invective normally reserved for genocidal dictators. Some of them were so over-the-top that, had the circumstances been different, we might have found them amusing. Of course, it’s hard to find anything amusing when strangers are publicly attacking your wife two days into your marriage. This was supposed to be the most intimate, sacred, precious and romantic event of our lives: our wedding day.

But nothing is sacred on the Internet, not even a wedding. The headlines made a hysterical case for the damage done to the site with such titles as: “Eco-wrecking Wedding“; “Ecological Wedding Disaster“; “$10 Million Destruction of a Park“; and “Tasteless Eco-trashing Wedding.” We were charged and convicted, by the Internet press and the court of public opinion, with every imaginable environmental crime.

Our wedding, it was written, illegally damaged the redwood forest, trashed a Big Sur campground, and threatened the habitat of a special-sounding fish, the “endangered” steelhead trout. The press described how we had “trampled” a “massive ancient redwood grove,” run roughshod over a “pristine” public park, leading to “sedimentation” of a creek that was a spawning ground for steelhead trout. The press claimed that redwood trees had been cut down by bulldozers, and that we had destroyed this very sensitive, fragile, redwood habitat. The wedding was widely derided as “tasteless,” “obnoxious,” and “extravagant.”

If our friends were sending us congratulatory messages, we never saw them. If Alexandra’s friends were complimenting her choice of wedding dress, she missed those messages. Indeed, if anyone was saying anything nice about our wedding, it was completely lost in the noise, drowned in the sea of hateful, spiteful messages. Our marriage announcement and wedding photo on Facebook elicited hundreds of these messages from angry bystanders telling us to “fuck off,” and calling us “selfish,” “contemptible,” “disgusting,” and “hypocrites.” Descriptions of me included the words “douchebag” and “prick,” of my wife, the words “gold-digger” and “whore.” Luckily amongst the rabble were some unusually creative hate-mongers who managed to keep our attention by dispensing inventive insults like “douchemonster,” “jackassery,” “jackwagon” and, my personal favorite, “douche canoe.” (I have no idea what a “douche canoe” or a “jackwagon” is, but I’m assuming they are neither forms of transportation nor compliments.)

We were told that we should be “hung” for our crimes, “preferably on a lamppost since trees are too good [for them].” A number of people thought jail time “to make an example of [him],” was warranted. A more thoughtful commenter suggested that “jail time in Salinas with the Norteños” would be a more appropriate punishment than, you know, regular old jail time. That just wouldn’t do.

We expected the histrionic media backlash to be short-lived. That may have been wishful thinking. The assault continued for days, with wave after wave of articles, each headline more hyperbolic and more scathing than the last, each story further inflating the alleged cost of the wedding, the damages, and the personal attacks.

After days of enduring this public beating, I had reached my limit. I took to the Internet to defend our wedding, hastily penning a letter intended to refute the most damning story, Alexis Madrigal’s post in The Atlantic Wire, which had labeled our wedding “the perfect parable of Silicon Valley excess.” Though not alone in his criticism, Madrigal’s voice stood out among the crowd of voices condemning our wedding, partly because his story was better articulated and came from an otherwise credible writer, and partly because it drew sweeping conclusions about me and Alexandra, our intentions, and the deliberate and wanton nature of our so-called crimes.

Never mind that none of the accusations were actually true. Truth has a funny way of getting in the way of a great story.

Setting the Record Straight

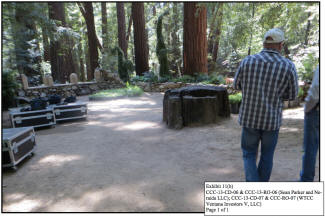

I cannot be too hard on Alexis Madrigal, as he was kind enough to read my email, kind enough to apologize, and had the strength of character and journalistic integrity to post my email publicly along with a sort of retraction, something most reporters would be too prideful to do. As I wrote in my response to him, nobody chooses to get married in a redwood forest unless they love redwood forests. Furthermore, our wedding did not take place in a park, on a nature reserve, or on any other form of protected public land. We rented our wedding site from a company operating a luxury hotel, the Ventana Inn & Spa, owned by two multi-billion-dollar private equity firms, both experienced players in California real estate. The site of the wedding was a private, for-profit, vehicular campground, largely paved over in black asphalt, full of compacted dirt, giant holes dug in the forest floor and mounds of dirt piled up around those holes.

The natural vegetation you would expect to find in a pristine redwood forest had been bulldozed – no sorrel leaf ground cover, no ferns, no wildflowers. While many old growth trees remained on the property, the site had been subjected to a century of logging, and much of the remaining forest was second or third growth. All of the greenery you see in our photos, the ferns and other plants, had to be brought into the site, by us, in order to recreate the look of an undisturbed redwood forest, which this forest was decidedly not.

Many press reports have focused on the notion that we had somehow harmed the environment. This is simply not true. No redwood trees were harmed in any way. No endangered species were harmed, and, in fact, none were resident on the property. Fabric liners were used to protect the ground from our landscaping work. We were careful not to plant directly in the ground – we brought in potted plants instead.

Lisa Haage, the California Coastal Commission’s Chief of Enforcement, said at the Commission hearing last Friday that “the environmental damage from the wedding-related construction work was less serious than we had originally feared, in part due to the fact that the large majority of the development was performed on a campground and existing road, not in a virgin forest.”

From the outset, our goal was to leave the forest in significantly better condition than we found it. Everything on site was built to be temporary. The set pieces were hollow, created off-site and pieced together like Legos on the property. Even the stonework had no mortar inside it to facilitate easy disassembly.

We had no obligation — legal, contractual or otherwise — to apply for permits. We weren’t the property owner, nor were we “leasing” the property from the owner. We had paid the hotel an event fee in order to make use of their campground for the purpose of hosting our wedding. We had no legal standing to apply for permits related to a property we didn’t own. Not only that, we couldn’t have known what permits were required short of asking the property owner, which we had done prior to renting the property, and the management of the hotel had informed us that none were required. It was incumbent upon the property owner to inform us of any land-use restrictions or permit issues related to the property.

From the outset we shared our plans for installing theatrical backdrops and other wedding-related equipment with the hotel. And the hotel was an active participant in the construction process — it wasn’t as if we were making preparations on Mars — this was all happening in the hotel’s backyard, and the hotel management was onsite every day supervising the project. They never hinted at any issues with the California Coastal Commission or any other government agency. In fact, I had not even heard of the California Coastal Commission until this incident. Why would I have? I don’t own any property in the California coastal zone. Had I known about any of these issues prior to renting the site, I would have taken my business elsewhere.

Then there was this question of a certain fish, the “steelhead trout,” that was purportedly threatened by our wedding preparation. The media reported that this fish was an “endangered” species whose spawning ground was a creek near our wedding site. Yet a simple Google query of “steelhead trout” reveals that this fish is not, as the media had reported, a truly “endangered” species, but rather a fancy variant of the common “rainbow trout” that is abundant across North America — so abundant, in fact, that it is sometimes considered a pest species. (The steelhead, like salmon, travels upstream and spends its life in the ocean. This variant of the rainbow trout has seen its populations fall in some areas of California where it is protected, but it’s hardly the endangered species the press made it out to be. In fact, the National Wildlife Federation reports that rainbow trout is “not at risk of extinction.”)

The California Coastal Commission’s own publicly available report on the matter refers to a stream, called the Post Creek, that apparently runs through the property, although they were noncommittal about whether or not the trout was actually present in the stream, or even if the stream contained enough water for the trout to spawn. There was a chance, the report stated, that our construction “could” have led to sedimentation of this stream, which in turn “could” have prevented fish from getting on with their business. In the days leading up to the wedding, multiple biologists visited the site and their reports confirmed “no increased turbidity” in the stream, meaning no “sedimentation” had occurred. Even more ridiculous, the part of the creek where these fish, if they existed in the creek at all, would have been spawning, was not on the part of the property where the wedding construction had taken place.

If only the media had read the documents, perhaps this public crucifixion would have abated. But no, the media couldn’t be bothered with any of these facts, hidden as they were in plain view, especially since they were engaged in the serious business of reputation assassination against a “disgusting,” “appalling,” “eco-trashing,” rich guy. So it’s not surprising that the media also conveniently failed to mention the most important detail of all.

The campground, which was supposed to be open to the public as a for-profit venture of the hotel, had actually been closed since 2007, largely due to a rather unfortunate, and literally stinking incident. It turns out that Monterey County inspectors had discovered the presence of human waste leaking into Post Creek. The nearly dry, putative spawning ground of the steelhead trout, had, in fact, become a bath of human waste stemming from the faulty, or otherwise inadequate, wastewater treatment facility on the hotel property. This led Monterey County to issue an order, for obvious public health reasons, to close the campground pending the remediation of this wastewater treatment facility.

This was a big part of what the media had missed in its rush to judgment. Due to the publicity around our wedding, the commission began looking into the site and discovered, unbeknownst to us, that the campground had been illegitimately closed to the public for six years. The major infraction, from the perspective of the California Coastal Commission, was not damage to the redwood habitat caused by the wedding, but rather the fact that development had occurred on the site without the property owner (the hotel) seeking a permit, and, moreover, that the hotel was obligated to keep the site open to the public as a commercial campground. This issue — the closure of the campground to the public — was not caused by us, it was in no way our fault, but it was unearthed when the commission began investigating the hotel due to our wedding.

In order to understand the importance of this issue, one must first understand that the California Coastal Commission is charged with two primary responsibilities: first, regulating development in the coastal zone in order to protect coastal resources; and second, ensuring public and recreational access to the coast, considered to be a public resource in California. The commission is empowered to protect that public access via fines levied against property owners, but, technically speaking, it needs to take property owners to court in order to do that. The commission largely settles these disputes through contracts called “consent orders.” Even the name of these contracts emphasizes the fact that they are not so much “orders” as they are, strictly speaking, consensual. Only when the commission is unable to reach these settlements do they refer the matter to the court system, an expensive process for California taxpayers, and one that, in practice, rarely happens.

So the commission’s biggest issue turned out to have nothing to do with the wedding itself: The commission was upset that the low-cost campground had been closed to the public since 2007. In a settlement agreement dating back to 1982 between the California Coastal Commission and the Ventana, the hotel was required, as a condition of its permit to operate a luxury hotel, to maintain this public camping facility. That plan was derailed when noxious human waste started showing up in the creek some years later and Monterey County shut down the campground.

The commission claimed they were never properly notified, effectively pitting the desires of these two government agencies against each other. The Ventana was, in the eyes of the commission, liable for damages related to the campground closure from 2007 onward. This was acknowledged publicly on June 12th by commission spokeswoman Sarah Christie who told the Monterey County Weekly: “Mr. Parker, in essence, leased an ongoing Coastal Act violation when he leased the campground.”

The Media Reaction

“It does not do to leave a dragon out of your calculations—if you live near him.” –J.R.R. Tolkien

The biggest mistake we made in wedding planning was forgetting about the media: that silent, invisible dragon breathing down our necks all along. Nothing has been more shocking to me than the media’s handling of this “controversy”: there were hundreds of articles written, and yet — incredibly — there was only one reporter who bothered to ask us for comment prior to publishing their story.

While not every publication operates this way (some abstained from participating in a public lynching, and a few traditional journalists such as this publication and this one published accurate rebuttals afterwards), the fact that so many did engage in the misinformed attacks, even credible outlets like The Atlantic, stands as a stunning testament to the state of online journalism. How could nearly every single reporter have failed to conduct any interviews with anyone at all, let alone ask the very subject of their stories for comment? We would have gladly responded and perhaps much of this anguish could have been avoided.

I have known the media to be irresponsible at times, but this represents a new low. The media should not get a free pass for publishing erroneous information, making baseless allegations, and impugning the sanctity of a private wedding, especially without conducting any investigation or interviews. Rather than basing their reporting on primary source material, the online tabloid press just piled onto the story, sourcing each other, and churning out increasingly sensational and exaggerated headlines as fast as they could type them. I’ve never seen a story get so much play where nearly every reporter did no original reporting.

They literally couldn’t be bothered with it: Hundreds of reporters called exactly zero sources, asked exactly zero questions, did exactly zero research, and even managed to ignore the information contained in readily available public documents. In the fast-and-loose world of “blogging for dollars,” it probably feels like a waste of time to do original reporting when writing snarky stories with a paucity of facts is a more efficient way to generate traffic. Regardless, it was astonishing to see this volume of inaccurate, derivative stories written without any concern for fact checking or sourcing.

When I got started in this industry almost 20 years ago, things were different. Back then there were no blogs, no Twitter or Facebook, and the editorial world was still a growing business. The reporters I interacted with diligently researched their stories, tracked down sources, conducted interviews, and even fact-checked their stories before publication. The trouble with online media is that there’s no incentive for them to do any of this. It’s easier to generate traffic with snarky stories than hard news, and there’s no downside for getting the facts of a story wrong, or even making it up entirely. The law offers no recourse, since being a “public figure” denies you, for all intents and purposes, any protection under libel laws. The blogs attack you, do their damage, and then move on to their next target. Now, because of the permanence of the Internet and the ease of Google, these vicious online attacks leave behind a reputational stain that is very difficult to wash out.

Anatomy Of A Crisis

The story of how we ended up stuck with a $1 million bill for infractions that were not, legally, our responsibility, and how we decided to make an additional $1.5 million in charitable contributions, begins as most things do, with a leak. Alexandra and I had been working towards the vision of our perfect fairy-tale wedding for close to two years.

A slightly embarrassing confession is in order: My wife and I are huge nerds. And as the press has speculated, we threw something of a big fat nerd wedding. Alexandra and I have always been fantasy buffs, in particular devotees of “high fantasy.” We both devoured books in the genre growing up and we both reserved a special place in our hearts for Tolkien, seeing as how fantasy, or as Tolkien puts it “fairy stories,” could be a device for exploring big archetypal human themes with a strong moral compass. Good and evil. Power and responsibility. Death and immortality. As a young girl, Alexandra was a member of a fantasy writing society. She’s loathe to admit it, but she even celebrated a few recent birthdays at Medieval Times.

One of the most salient themes of our ceremony, and also of our vows, was the notion of “sanctuary” – finding a literal and existential place of solace where my wife and I could be together, alone with our thoughts, at peace with ourselves, able to express ourselves openly without fear of judgment or social scrutiny. In this sense, “sanctuary” is about the freedom to express our “true” selves to each other, which is fundamental to intimacy. Such a place is increasingly difficult to find in our technologically supercharged and hyper-connected world. Unless you’ve chosen to lead a monastic life, apart from society, then you are undoubtedly subjected to socially reinforced notions of who you are and what you represent within your society. For those cursed with celebrity or notoriety, the imposition of external assumptions about your identity is only exaggerated.

We chose a setting for our wedding that was a literal expression of our search for sanctuary — a place that was safe, private, and intimate. We chose a remote location (Big Sur), invited no press, and did our best to conceal that location from the press. We didn’t court attention — quite the opposite, we asked guests to check their cell phones and cameras at the door and we didn’t sell our photos to tabloids. It’s possible that the backlash which compromised the sanctity of the event was exacerbated by our desire to preserve the privacy of our special day. (The monsters of the tabloid press, like dragons, are happier when fed.) In the frenzy to cover our wedding the press had nothing to run but construction photos of the wedding and nothing to talk about but this bogus eco-destroying theme.

Our wedding was the antithesis of the technology-infested world we live in; a world that I have played a role in creating. It was an homage to the natural environment. It was also a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to force 364 otherwise self-respecting adults to dress up in elaborate fantasy-inspired costumes, a feat of mischief that we were delighted to attempt. The Academy Award winning costume designer (for “Lord of the Rings”), Ngila Dickson, was our co-conspirator, and her brilliant designs exceeded even our wildest dreams.

This emphasis on privacy was why it came as such a surprise when the tabloid news outlet TMZ began making claims about our wedding, including wholly exaggerated claims related to the money we were spending on it. These fictional rumors raised questions in the local community about our wedding. This was our first clue that there might be issues with the media, yet with a couple of months to go before the wedding, things seemed to be on track. My relationship with the Ventana was cordial, and I had no reason to expect any major glitches.

Then disaster struck. Just 20 days prior to our wedding, the hotel received a call from the California Coastal Commission asking us to stop work. The media attention around the wedding had incited the curiosity of the local community who had referred the matter to Monterey County, who in turn had referred the matter to the commission. We’d never heard of the commission at that point. Naturally we complied with the request and I scrambled to find someone who knew something about this mysterious government agency.

After two years of wedding planning we were now within weeks of the big day. By that point, all of our guests were already booked into hotels and all of the preparations had already been made. The weeks preceding a wedding are critical; they’re the busiest weeks for the planners, designers, and staff. There were hundreds of creative people working on the project who had poured their hearts into it, just as we had. Now my bride-to-be was in danger of losing her wedding. I didn’t want to let her down.

As soon as the Ventana found out there was an issue they threatened to cancel the wedding unless I entered into a broad indemnification agreement. We had nowhere to turn at that point, no backup plan, and there was no place in the Big Sur area that could accommodate 360 guests. We had all of our equipment, materials, decorations, and other items on site and we would not have been able to relocate them without a commission settlement. Ironically, if the process of placing everything on the site constituted “development,” then so would the process of removing it. I was caught in the middle of this dispute between the Ventana ownership and the CCC, doing my best to help them resolve the issues so the wedding could proceed.

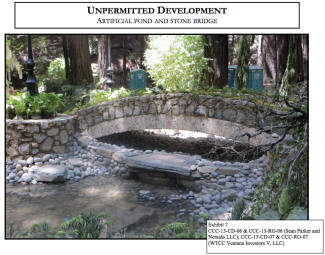

The commission provides a “temporary event exemption” which should, in theory, cover the kind of temporary development that goes into a wedding. (Although the modifications we made to the site were all temporary, our wedding involved some heavy landscaping, such as stonemasonry, the installation of a small fake pond, and other theatrical flourishes that might have disqualified it.) All of the work we did, it should be noted, was placed on the existing paved or cleared areas of the campground, and it was all designed from the outset to be removed immediately after the wedding.

We were backed up against a wall. Ultimately, the Ventana was unwilling to accept any financial responsibility and preferred to cancel our wedding rather than work things out with the commission. We had no choice but to step in and pay for all of their violations, both the un-permitted construction and also past liability related to the campground closure.

Those 20 nail-biting days leading up to the wedding were some of the most stressful days of my life; we had no assurance the wedding would even take place. At the lowest point in the whole process I had to inform Alexandra that there was a very good chance we would not be getting married on June 1. The anxiety of moving forward with a production this big and this important without certainty was dreadfully taxing.

The commission alleged that un-permitted development had been undertaken. Not wanting to appear “soft” on rich people in a high-profile case, the commission took a hard line in its staff report on the possible harm caused. As much as I respect the mission and hard work done by the California Coastal Commission, it is important to note that the world of “consent orders” is a world of hypotheticals. Everything in a consent order is alleged, not proven, and the commission generally takes a “kitchen sink” sort of approach toward creating these consent orders and accompanying staff reports. The key to writing an effective one is to pick out every imaginable, conceivable, possible argument one could make, no matter how far-fetched, in order to justify the largest possible fine against the alleged infringer. Without direct effective enforcement power, the commission is forced to take this aggressive stance, laying out their allegations in much the same way that a plaintiff drafts a lawsuit.

This point is illustrated in the words of Mary Shallenberger, chairwoman of the commission: “If Mr. Parker had not been willing to settle with us, if he had dug his heels in and said, ‘Heck no,’ you know, the only option would have been to go to court on this issue. So I thank him for doing it voluntarily and working with our staff; but had he not been willing to do that, we would not have the authority to impose or even require that he negotiate with us and accept any kind of penalty.” (The commission probably needs greater power to impose fines like most other commissions, but along with this power they need to temper the ferocity of their approach.)

Some media reports took the position that wealthy people “can buy their way out of anything.” And yet my settlement was the largest settlement in the history of the commission. The reason it was so large was not because my violations were so heinous, but because I was backed into a corner and had no choice but to give in to any demands made of me by the hotel or the commission.

So-called “rich guys” don’t get any special treatment with the commission. If anything they get a worse deal. The commission is sensitive about appearances; they can’t be seen letting a “rich guy” off too easy. And there was nothing special about the fact that I settled with them rather than going to court. Since the commission cannot impose fines directly (they need to refer matters to the court system), they are highly motivated to settle cases. In fact, most cases are settled with “consent orders” and never make their way to court. This is good for the commission and it’s also good for the people of California — litigation is expensive and settlements bring in funds that can be used for coastal conservation and restoration projects. In a press release after the settlement was announced Mary Shallenberger states: “Any time we can settle a violation and avoid litigation, we consider that a good outcome.”

I spent five hours with CCC staff at their headquarters, and we worked out the terms of the settlement. I would be covering the $1 million in fines for un-permitted construction that was technically the hotel’s responsibility, covering their past violations, and also providing “mitigation” far beyond what would be normal in a case like this. The consent orders and staff reports are customarily written to sound harsh in order to justify the fines. This was part of what led the press, largely unfamiliar with the inner-workings of the commission, to draw such extreme conclusions. In its defense, the commission was kind enough to offer language in its press release about how I had “been cooperative,” but this was generally overlooked by reporters who chose to focus on the alleged infractions as though they were hard facts and, unfortunately, as though they were my fault.

Our wedding was set to occur on Saturday, June 1. We endured 18 days of brutal negotiation — a three-way negotiation between us, the hotel, and the California Coastal Commission. The tension grew with each passing day, and throughout this process we mentally prepared ourselves for the worst — that we would not reach agreement with all parties and that the wedding would be cancelled. The week of the wedding things were still unsettled. Finally, on the Thursday before the wedding we reached agreement, and by 6 a.m., the morning before our wedding, I signed the consent order. That settlement would cover not only the hotel’s liability for the un-permitted development but also a host of prior infractions that predated our use of the site. I also volunteered a rather large charitable contribution — $1.5 million — which would be used for coastal-related projects in the local community.

The wedding was going to happen. I was getting married. I would be able to see the look on Alexandra’s face when she walked down the aisle.

Our wedding day was a beautiful dream come true. After all the stress of the preceding 19 days, the wedding itself went off without a hitch. Afterwards we were excited to run away on our honeymoon and forget about everything.

Then the media backlash began. The next thing I knew the media was portraying me as a crass, insensitive, eco-trashing billionaire, cartoonishly driving a gigantic hell-razing bulldozer, gleefully plowing down what remained of “Fern Gully: The Last Rainforest.” The Sacramento Bee literally turned me into a political cartoon.

I had become the media’s latest whipping boy, an icon of the newly minted Silicon Valley elite gone bad, and now the media was clearly trying to peg me as the sort of symbol of excess who needs to make an appearance in popular mythology every so often. The 80s had Milken, the 90s had Ebbers, and the financial crisis of the last few years gave us an entire cast of villains, including the infamous Madoff. Maybe the media was growing impatient with the lack of recent criminal behavior from the super rich?

I was pegged as the latest in a long line of public figures who fit this tired old stereotype, a corrupt, villainous businessman who co-opts the political system, shadily buys his way out of problems, and tramples a protected ecological zone in the process. For the media, I was just a convenient example of a next-generation business leader gone to the dark side. Yet I couldn’t escape the feeling that I was terribly miscast in the role I was being asked to play. For starters, the facts of the case didn’t support this portrayal, and my own attitudes and beliefs couldn’t have been more contradictory. My infatuation with redwood forests and conscientious approach to selecting and decorating the site were at odds with the depiction. And given my progressive politics, idealism, and general anti-establishment bias, I had the distinct feeling that, had any of these reporters actually met me, they might have been sorely disappointed by their choice of candidate; perhaps the way the Republicans had felt about Mitt Romney.

I’ve been used as a plot device before — the film The Social Network established this caricature of me in the media’s imagination: the morally reprehensible “brogrammer” douchebag. I had been mythologized. The more I thought about this notion, the more I began to realize that myths are stories that have a life of their own, stories so good that people keep telling and re-telling them, even if they’re not true. I suppose the myth that was created about me was too good of a story for people, including the media, to stop telling it. This myth about me lives on in spite of me, and after I’m gone, it may even live on without me.

If I was such a callous jerk, then why was the commission lauding me for my efforts? Shortly after the brunt of the backlash, on June 14, the public hearing of the California Coastal Commission took place and the Chairwoman, Mary Shallenberger, thanked me for the role I played in exposing the longstanding violations of the hotel: “I thank Mr. Parker for having his wedding there so we discovered all the violations and the six years where the public has not had access,” said Shallenberger.

Protecting the Redwoods

There are very real threats facing the redwood forests. Our wedding was not one of them. The media, in referring to the redwood forest, consistently used adjectives like “fragile” and “sensitive,” implying that the kind of work we were doing in the forest amongst these towering giants could somehow harm them.

The reality is that the redwood forest is a robust and resilient ecosystem, able to survive all manner of insults hurled at them by nature and humans alike, from fire, to insect infestations, and even drought. “Redwood forests are hearty places,” writes Emily Burns, Director of Science at the Save the Redwoods League and a specialist in redwood ecology. The hollowed-out shell of a burnt redwood tree, somehow still alive, is a familiar sight for anyone who has spent time hiking amongst redwood trees. There is even a popular tourist attraction, the Chandelier Tree, that lives on despite a massive hole cut in it the base of its trunk, a hole so large you can drive a car through it.

There is, however, one thing certain to destroy a redwood forest, and that is logging. The practice of logging redwood forests for their lumber continues in California to this day, and old-growth redwood trees are given no exception. Roughly one-third of all remaining old-growth redwood forest is owned by timber companies and, contrary to what one might expect, these trees are offered no protection under California or Federal law.

Prior to logging, it is believed there were at least 2,100,000 acres of coast redwood forest in California. Today only 5 percent of that original forest remains, and roughly 133,000 acres of that is preserved in California’s Redwood State and National Parks. At least 100,000 acres of old-growth coast redwood is in the hands of commercial timber companies, and therefore at risk, and very little is being done about it. In an email after the media backlash began, Emily Burns, of Save the Redwoods League, pointed to the flagrant absurdity of the response: “It’s amusing that people focus their attention on this event when the redwoods face actual threats elsewhere that are much more worthy of gossip!”

The League is one of the few organizations that is actually doing something about these threats, largely by raising money to purchase land, either to place conservation easements on that land, or contribute it to the state park system. During the introduction of enhanced logging technology in the early 20th century, which led to more rapid deforestation, the league played a vital role in saving what few redwood forests remain. They were early leaders in the conservation movement, founding the California State Park system and then purchasing as much old-growth redwood forest as they could for the past century. It’s largely because of their efforts that we still have any of the original old-growth redwoods left at all.

I strongly believe that redwood forest should be a protected ecosystem, but that is not true today. A variety of media reports related to our wedding stated that the area we were in was a “protected” ecosystem. The campground we rented was subject to land-use restrictions imposed by the California Coastal Commission, but, regrettably, redwood forests, themselves, have no special legal status in California.

I would argue that they should, that what remains of old growth forest should be protected from logging and development. (Despite the label given to California’s redwoods, “coast redwoods,” most of these forests are not located in the coastal zone and therefore they enjoy no protection by the Coastal Commission or any other state agency.) All of the misleading press about our wedding does nothing but reinforce the unhelpful misconception that old-growth redwood forests are actually a protected ecosystem when they are not.

The last two weeks have demonstrated just how cruel and senseless the online community can be. But Alexandra and I are pretty resilient people, and like the redwood trees we were married under, we’ve survived worse insults. There is no point pouting about what happened; we’re better off making the best of a bad situation. One way is by calling attention to the real crimes being committed against the redwood forest. We will continue to support organizations like Save the Redwoods League. We’re also going to do everything we can to make the $1.5 million charitable contribution we’ve offered really count. We are open to your creative suggestions as to how that donation should be spent. The project must be conservation or public access-related, and must be based on the Monterey Peninsula.

In the End, What’s the Lesson, Really?

If our wedding wasn’t “the perfect parable of Silicon Valley excess” as Alexis Madrigal originally claimed, then what kind of parable was it? What lesson, if any, should we, collectively, take from this saga? The perfect parable of our dehumanized detachment from each other, a result of the distance technology has created between us? The perfect parable of a broken, malfunctioning media? Or is it the modern version of the myth of Icarus, who dared fly too close to the sun?

This is the question for pundits. It may be that there is no lesson at all, at least not one that’s broadly applicable. Speaking personally, this entire experience has prompted me to think about the state of journalism, in particular the way in which social media, blogging, the acceleration of the news cycle, and the flattening of the media landscape have altered journalism over the past decade. One could easily write off what happened with a blanket criticism of the media: They’ve become link-baiting jackals who believe that “truth” is whatever drives clicks.

Yet this simplistic characterization overlooks the deeper structural changes the media has undergone in recent years, some of which I helped instigate. I have often wondered if we’re better off as a society now that the media has “opened up,” with fewer barriers to entry, less friction, and more voices included in the debate. Have the changes wrought by the Internet (broadly) and social media (narrowly) been helpful to civil society, harmful, or some combination of both? This is a question that must be posed to journalists themselves. As someone who is often the subject of press reports, I have only one part of the requisite experience to make that determination.

Regardless, I can’t escape the feeling that there is a kind of cosmic irony at work here. Readers of this publication are likely familiar with my career in the technology sector. I have spent more than a decade creating products built on the premise that the democratization of media was a good thing, that self-publishing, the free sharing of information, and the removal of the media “gatekeepers” would all lead to a freer, more open media — with the implied assumption that this was a “better” media. I practiced what I preached, both talking about and designing systems around the core belief that empowering people with the tools to more freely access and share information — be it music, links, photos, text, or any other form of media — could only make the world a better place.

Two of my companies, Plaxo and Facebook, were built around the idea that “identity” was a cornerstone of online discourse. I believed that introducing real identity — names and faces — into the anonymous free-for-all of the Internet, would lead to accountability, and that this was a necessary, if not sufficient condition for online discourse. Accountability would help enable civility and responsibility, facilitate the creation of systems that would allow the cream to rise naturally to the top. This, combined with clever algorithmic filters, might diminish the importance of human editors. I never believed “identity” was some kind of panacea, but it certainly seemed as though it was an essential deterrent to bad actors in a medium that had few, if any, standards of conduct.

And yet, as if by some process of karmic retribution, the mediums I dedicated my life to building have all too often become the very weapon by which my own character and reputation has been mercilessly attacked in public. No thanks to the moderating powers of identity and accountability, users of these mediums are happy to attack me publicly, in plain view, using their real names and identities, no veil of anonymity required. I have watched as these new mediums helped foment revolutions, overturn governments, and give otherwise invisible people a voice, and I have also watched them used to extend the impact of real-world bullying from physical interactions into the online world, so kids growing up today can now be tormented from anywhere. I have also witnessed these mediums used to form massive digital lynch mobs, which I have been at the mercy of more than once. I guess it’s only fitting that I would be; the universe has a funny way of returning these things in kind.

Economically speaking I came out on top. I have been one of the greatest individual beneficiaries of this seismic shift in media. I have made, quite literally, “a billion dollars,” which, as I’m constantly reminded by the media, is “cool.” But I’m the first to admit that this shift away from a centralized, top-down media towards a decentralized bottom-up media did not come without a cost. At some point in time everyone, whether they engage actively with these new mediums or not, will experience a violation of their privacy, will find their reputation besmirched publicly, and may even find their sanity challenged by some combination of these factors. (The story of Jason Russell, co-founder of Invisible Children, comes to mind.)

A kind of mob mentality reigns supreme in the unrestricted, uncivilized world of social media: whether it is found on Facebook, on Twitter, in blogs, or even in the remnants of traditional journalism, where the old guard is now forced to compete with the instantaneous news cycle of the “real-time web” and the blogosphere. The economics of this new media have, in so many ways, rendered obsolete the economics of the old journalism and the value system that went along with it. The ethics of journalism, a commitment to objectivity, accuracy, and civility, formed a kind of loose social contract between the creators and consumers of news.

This code was embraced by the entire news-making industry, indoctrinated into students at journalism schools, and reinforced by the editorial boards of respected news outlets. This value system was hard-earned over the last century. Born out of the corrupt politics of the early 20th century and the “yellow” journalism of Hearst and Pulitzer, it was only gradually displaced by the values of a new generation of publishers that adhered to higher standards of journalistic integrity. Eventually this led to the era of the professional journalist as we once knew her, with her code of ethics and the institutions that supported her — the great bastions of journalism: the newspaper empires built by the Grahams and Sulzbergers and the giants of the broadcast journalism world, people like Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite, who cast penumbral shadows across the careers of every news anchorman who followed them.

By the late 1990s the system was beginning to show signs of wear. The loss of revenue from newspaper classified advertising to companies like Craigslist, Monster.com, eBay, and other listings sites was only the first shot across the bow. The massive shift in advertising revenue toward Google, and later Facebook, was the cannon fire that followed. But the real war over journalism was a war of attrition, as the web, blogs, and advertising technology gradually ate away at what remained of journalism.

This long cold war was fought and lost over measurement: The old guard finally gave in to the commoditization and sensationalization of news when “clicks” became the ultimate and determinative measure of value in the news ecosystem. The public had always mildly distrusted the business of journalism, believing that headlines sold papers, but they at least believed in the purpose of those papers — in their importance. Now no higher purpose remains; headlines drive clicks, and clicks sell ads. Only the most dogmatic, or perhaps idealistic, reporters remain capable of believing in a higher set of motivations. Many writers, who once would have self-identified as journalists, are now just as happy to be called writers, or even “entertainers.”

At best their job is to produce original content, generating stories in the hope that someone will read and enjoy them. At worst it has become the repackaging of content into the digital drivel known as “click-bait,” the nearly automatic rehashing and regurgitating of nonsense news, contrived to tell whatever seems to be the most sensational story, and repeated endlessly within the “echo chamber” of social media. This new media opines and remarks on everything, contributes precious few objective facts to the debate, and reports on precisely nothing at all. It took a century to establish the economic, social, and legal frameworks that supported journalism. In under a decade those systems have been largely dismantled, abandoned and rendered obsolete.

Economically speaking, I profited handsomely from the destruction of the media as we knew it. The rest of the world did not make out so well, and society certainly got the worse end of the bargain. The decentralization of media got off to a promising start, but like so many other half-baked revolutions, it never fulfilled its early promise. In its present form, social media may be doing more harm than good. Perhaps we should have expected this — technology always leads the way, society and government inevitably play catch-up.

Now that social media has collapsed the traditional media roles of content producer, editor, publisher, and consumer into one and assigned those roles to literally everyone, it’s clear we need to collectively evolve our social norms to reflect this new reality. And wherever you stand on the questions of privacy and the Faustian pact struck between the federal government, technology companies and Congress over digital surveillance, it’s increasingly clear that our legal frameworks for dealing with these new mediums are outmoded at best. It’s natural for innovators, especially those creating entirely new industries, to have a laissez-faire bias, and they are right to think that way.

While new technologies will inevitably present new challenges that society must someday deal with, the “rush to regulate” risks smothering the infant in the cradle. Technologies first need to be allowed to grow up, mature, and become a part of an institutional social fabric before governments intervene. However, now that so many new mediums seem to be nearing adulthood, it may be time to start rethinking our collective relationship to these mediums.

In particular, we need to consider stronger privacy laws here in the U.S., a basic right to privacy along the lines of the laws enjoyed by the citizens of most Western European nations. We are all at risk of becoming “public figures” in a world where the media has expanded to include nearly everyone. In such a world, our defamation laws need to be updated to provide individuals with the protection from public persecution that they deserve. We also need to reinforce our personal privacy by beefing up the intellectual property laws that govern the personal content that we generate and share via services like Facebook.

The more we depend on social networks and other online services to share content with friends and family, the more we risk that our content inadvertently becomes public. The enforceability of intellectual property laws around user-generated content — our photos, videos, and other content — is one of the best protections we have. The media has, in many cases, chosen to broadly construe all content shared via these networks as “public” when in fact much of it is private, and the copyright on that private material belongs to the creator. Sharing photos on Facebook should no more constitute a public license to use those photos than sending them over email.

The ubiquitous license agreements and privacy policies that online services force their users to enter into should be scrutinized by the courts around the principle of adhesion, and if the courts are unwilling to reconsider the status quo then congress should intervene with legislation limiting the scope and enforceability of these agreements. We also need to be willing to consider that only Congress can prevent the abuse of governmental power that is used to coerce online services into to turning over data in a wholesale manner.

I am certain that social networks, technology companies, and telecommunications companies would prefer not to kowtow to governments around the world, but operating a service on the scale of Facebook or Google puts these companies in the crosshairs of governmental agencies of all kinds. Once a company has reached this scale, only governments pose a meaningful existential threat. It is therefore incumbent upon the legislature to craft appropriate boundaries that strike a balance between the valid needs of governmental authorities and the equally valid privacy demands of Internet users.

In the end, the lesson learned from my wedding was something much less obvious than the “parable of excess” that was claimed. Rather, the democratization of the media that I idealized in my youth when it was just a distant, blurry dream, suddenly seems much less worthy of idolatry now that it’s become a stark reality. The lesson for me, felt acutely over the past two weeks, ended up being a familiar moral to a familiar story: “Be careful what you wish for — you might just get it.”

Summary Points

• The wedding site was chosen because it had been previously developed, so there was no environmental impact. The site was not public property, it was a private, for-profit, campground, which was mostly paved in asphalt and or cleared of all foliage. Development only occurred in cleared dirt and asphalt areas.

• The natural environment was not harmed, despite widespread claims to the contrary. There was no harm done to redwood trees, other plants, or animals. There were no endangered species on or near the property.

• We were conscientious about protecting the environment, locating the site with the help of Save the Redwoods League and soliciting advice about how to avoid harming the redwood habitat.

• Hundreds of articles were written in the days following the wedding, yet only one reporter contacted us for comment.Most of the information contained in these articles was erroneous. No original reporting was done, no interviews were conducted, and no fact checking occurred.

• We voluntarily agreed to cover $1 million in penalties related to the Ventana’s lack of development permits and past violations. We also volunteered to contribute $1.5 million in charitable contributions serving the coastal region of the Monterey Peninsula.