Part 2 of 2

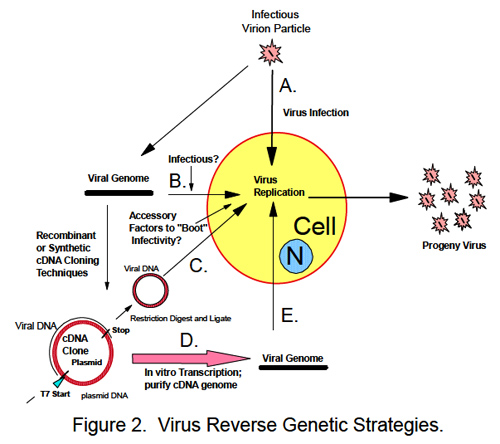

III. Barriers to Synthesizing and Resurrecting Viruses by Synthetic Biology and Reverse GeneticsGenetic engineering of viruses requires the development of infectious clones from which recombinant viruses can be isolated. Two basic strategies exist to develop and molecularly clone a viral genome: classic recombinant DNA approaches or synthetic biology. Although the basic methodology is different, the outcome is the same, a full length DNA copy of the viral genome is constructed which is infectious upon delivery to a permissive host cell. Classic recombinant DNA approaches require the availability of viral nucleic acid, which is normally isolated from infected tissues or cells and used as template for cloning and sequence analysis. For RNA viruses, the approach includes using reverse transcriptase and polymerase chain reaction to clone overlapping pieces of the viral genome and then whole genome assembly and sequence validation before successful recovery of recombinant viruses (10). Virus genome availability is an important issue and until recently, a major bottleneck in constructing a molecular clone to any BW virus. Most, though not all, viral BW agents are not readily available except in high containment BSL3 and BSL4 laboratories throughout the world. The few sites and lack of funding support historically limited access to a small number of researchers, although increased support for BW research has greatly increased the distribution and availability of these agents throughout the world (31). Most viruses are also available in zoonotic reservoirs although successful isolation may require an outbreak or knowledgeable individuals carrying out systematic sampling of hosts in endemic areas. Then, containment facilities for replicating virus are necessary. Some exceptions to this general availability of controlled viruses include early 20th century influenza viruses like the 1918 H1N1 (Spanish flu), the 1957 H2N2 (Asian Flu), smallpox viruses (extinct 1977) and perhaps the 2002-2003 epidemic SARS-CoV strains, all of which are likely extinct in the wild given the lack of recent human disease. With the molecular resurrection of the 1918 H1N1 strain using recombinant DNA techniques (81), these viruses only exist in select laboratories distributed throughout the world.

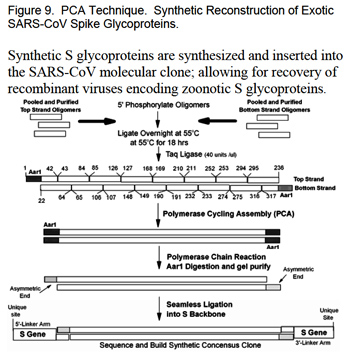

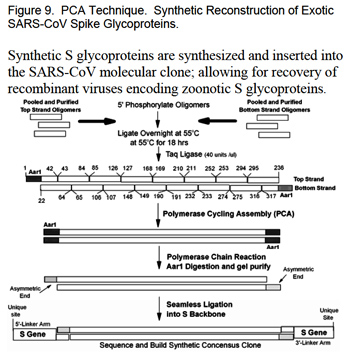

Two general approaches exist for synthetic reconstruction of microbial genomes from published sequence databases: de novo DNA synthesis and polymerase cycling assembly (PCA). Roughly 50 commercial suppliers worldwide provide synthetic DNAs using either approach, mostly in the range of <5.0Kb, although at this time only a few companies can assemble DNAs >30Kb. For example, Blue Heron’s GeneMaker™ is a proprietary, high-throughput gene synthesis platform with a ~3-4 week turnaround time and is reported to be able to synthesize any gene, DNA sequence, mutation or variant-including SNPs, insertions, deletions and domain-swaps with perfect accuracy regardless of sequence or size (

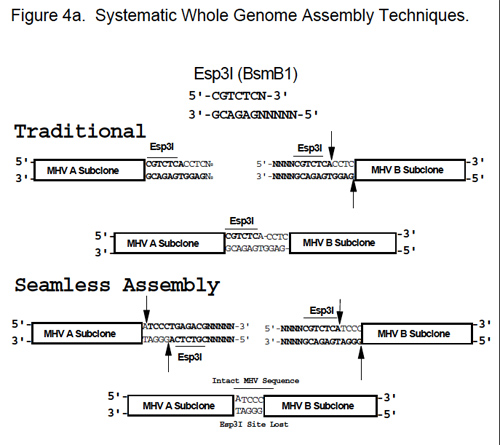

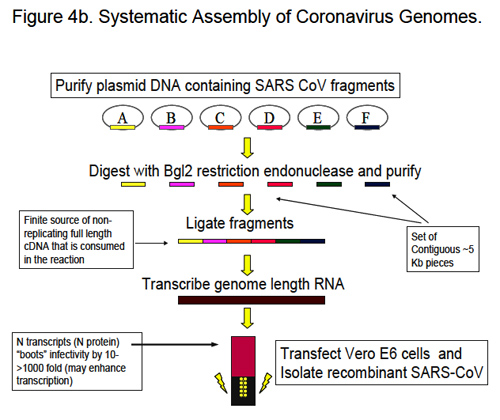

http://www.blueheronbio.com/). Most commercial suppliers, however, use polymerase cycling assembly (PCA), a variation on PCR. Using published sequence, sequential ~42 nucleotide oligomers are synthesized and oriented in both the top and bottom strand, as pioneered for ΦX174 (73) (Figure 9). Top and bottom strand oligomers overlap by ~22 bp. The PCA approach involves: 1) phosphorylation of high purity 42-mers (oligonucleotide strands of DNA) in the top and bottom strand, respectively, 2) annealing of the primers under high stringency conditions and ligation with the Taq ligase at 55oC, 3) assembly by polymerase cycling assembly (PCA) using the HF polymerase mixture from Clontech (N-terminal deletion mutant of Taq DNA polymerase lacking 5’-exonuclease activity and Deep VentR polymerase [NEB] with 3’ exonuclease proofreading activity), 4) PCR amplification and cloning of full length amplicons (Figure 9). The key issue is to use HPLC to maximize oligomer purity and to minimize the numbers of prematurely truncated oligmers used in assemblages. As PCR is an error prone process, the PCA approach is also error prone and it requires sequence verification to ensure accurate sequence. PCA is also limited to DNAs of 5-10 Kb in length which is well within the genome sizes of many viral genomes, although improvements in PCR technologies could extend this limitation. Both approaches, coupled with systematic genome assembly techniques shown in Figure 4, will allow assembly of extremely large viral genomes, including poxviruses and herpes viruses.

Figure 9. PCA Technique. Synthetic Reconstruction of Exotic SARS-CoV Spike Glycoproteins.

Figure 9. PCA Technique. Synthetic Reconstruction of Exotic SARS-CoV Spike Glycoproteins.Consequently, knowledgeable experts can theoretically reconstruct full length synthetic genomes for any of the high priority virus pathogens, although technical concerns may limit the robustness of these approaches. It is conceivable that a bioterrorist could order genome portions from various synthesis facilities distributed in different countries throughout the world and then assemble an infectious genome without ever having access to the virus. To our knowledge, no international regulatory group reviews the body of synthetic DNAs ordered globally to determine if a highly pathogenic recombinant virus genome is being constructed.

What, then, are the technical barriers to the reconstruction of viral genomes? Three major issues are generally recognized: sequence accuracy, genome size and stability, and expertise. They are discussed in this order below.

Sequence databases record submissions from research facilities throughout the world. However, they have limited ability to review the accuracy of the sequence submission. Consequently, these databases are littered with mistakes ranging from 1 in 500 to 1 in 10,000 base pairs. In general, large sequencing centers are more accurate than independent research laboratories (18, 36). Accurate sequence is absolutely essential for rescuing recombinant viruses that are fully pathogenic (7, 10, 30, 85, 86) as even a single nucleotide change can result in viable virus that are completely attenuated in vivo (74). Sequence accuracy represents a significant barrier to the synthetic reconstruction of these highly pathogenic viruses. RNA viruses exist in heterogeneous “swarms” of “microspecies,” thus requiring the identification of a “master sequence;” i.e., the predominant sequence identified after sequencing the genome numerous times. Consequently, full length sequence information may have been reported, but the published sequence may actually not be infectious. Problems with sequence accuracy are proportional to genome size, as reported sequence for large viral genomes will more likely include a higher number of mutations than small genomes. In many instances, sequence errors will reside at the ends of viral genomes because the ends are oftentimes more difficult to clone and sequence.

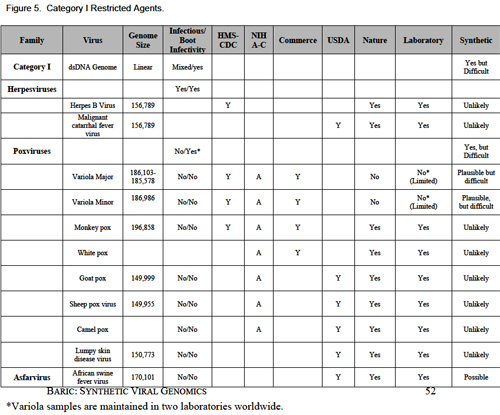

Using state of the art facilities, the smallpox genome from a Bangladesh 1975 strain was sequenced (47). However, an error rate of 1:10,000 would result in about 19-20 mistakes and 10-14 amino acid changes in the recombinant genome. Should these mistakes occur within essential viral proteins or occur in virulence alleles, recovery of highly pathogenic recombinant viruses might be impossible. More recently, another genome sequence of Variola major (India 1967) has been reported in the literature (Bangladesh 75, and India 67; Accession # X69198 and L22579). These full length genomes differ in size by 525 base pairs, contain ~1500 other allelic changes scattered throughout the genomes, and also differ in size and sequence with the Variola minor genome (Figure 5). Although roughly 99.1% identical, which of these reported sequences are correct? Will pathogenic virus be recovered from a putative molecular clone of either, both or neither? If neither is infectious, which changes are responsible for the lethal phenotype? In the absence of documentation of the infectivity of a reported sequence, it becomes difficult to accurately predict the correct sequence that will allow for the recovery of infectious virus. At best, a combination of bioinformatics, evolutionary genetic and phylogenetic comparisons among family members may identify likely codon and nucleotide inconsistencies, simultaneously suggesting the appropriate nucleotide/codon at a given position. In the case of poxviruses, only two full length sequences of Variola major have been reported, hampering such sequence comparisons. Ultimately this approach only allows informed guesses that may not result in the production of recombinant virus. Obviously, reported full length genomic sequences that have been demonstrated to generate infectious viral progeny provide an exact sequence design for synthetic resurrection of a recombinant virus, greatly increasing the probability of success. In the absence of this data, multiple full length submissions are needed to enhance the probability of success.

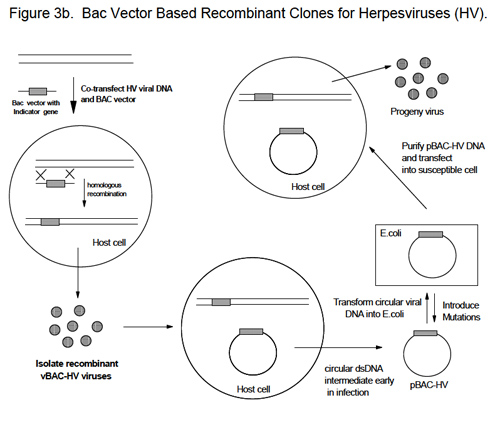

Another problem hampering the development of synthetic DNA genomes for genetic manipulation are genome size and sequence stability in microbial vectors. Many viral full-length cDNAs, including coronavirus genomes and certain flavivirus genomes like yellow fever virus are unstable in microbial vectors (10). Low copy BAC vectors and stable cloning plasmids oftentimes reduce the scope of this problem although instability has been reported with large inserts following passage (1, 85). Plasmid instability might be caused by sequence toxicity associated with the expression of viral gene products in microbial cells or the primary sequence might simply be unstable in microbial vectors, especially sequences that are A:T rich. To circumvent this problem, plasmid vectors have been developed that contain poly-cloning regions flanked by several transcriptional and translational stops to attenuate potential expression of toxic products (86). The development of wide host range, low copy vectors that can be used in Gram positive or lactic acid bacteria may also allow amplification of sequences that are unstable in E. coli hosts. Alternatively, theta-replicating plasmids that are structurally more stable and that accommodate larger inserts than plasmids that replicate by rolling circle models may alleviate these concerns in the future (3, 35, 58). Poxvirus vectors also provide an alternative approach for stably incorporating large viral genome inserts, although long-term stability of these vectors is unknown (1, 77).

The technical skill needed to develop full length infectious cDNAs of viruses is not simple and requires a great deal of expertise and support: technically trained staff, the availability of state of the art research facilities, and funding. Theoretically, the ability to purchase a full length DNA of many viral biodefense pathogens is now possible, especially for those virus genomes that are less than 10 kb in length. In addition, defined infectious sequences are documented and methods have been reported in the literature. Infectious genomes of many Class IV viruses could be purchased and the need for trained staff becomes minimized. Today, a picornavirus or flavivirus genome could be purchased for as little as $15,000, a coronavirus genome for less than $40,000. It is much more difficult to reconstruct large viral genomes, meaning that trained staff and state of the art facilities become very essential to the process.

However, it is conceivable that technical advances over the next decade may even render large viral genomes commercially available for use by legitimate researchers, but perhaps also by bioterrorists.

IV. Risk and Benefits of Synthetic Organisms

A. Benefits to SocietyThe benefits of recombinant DNA have been heavily reviewed in the literature and include the development of safe and effective virus platform technologies for vaccine design and gene therapy, the production of large quantities of drugs and other human and animal medicines, and agricultural and other products key to robust national economies. Genetic engineering of bacteria and plants may allow for the production of large quantities of clean burning fuels, produce complex drugs, design highly stable biomolecules with new functions, and develop organisms that rapidly degrade complex pollutants (52, 56, 64, 78). Comparative genomics also provides numerous insights into the biology of disease-causing agents and is allowing for the development of new diagnostic approaches, new drugs and vaccines (27). Synthetic biology enhances all of the opportunities provided by recombinant DNA research. The main advantages of synthetic genomics over classic recombinant DNA approaches are speed and a mutagenesis capacity that allow for whole genome design in a cost effective manner (6). How will synthetic biology protect the overall public health?

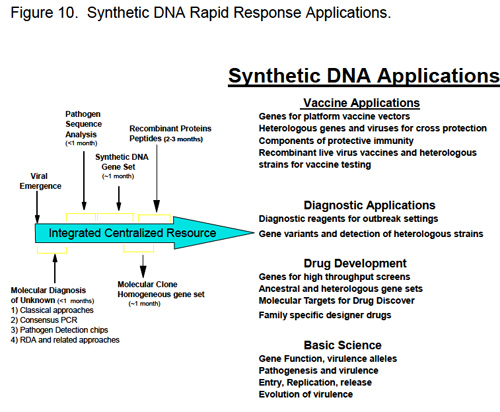

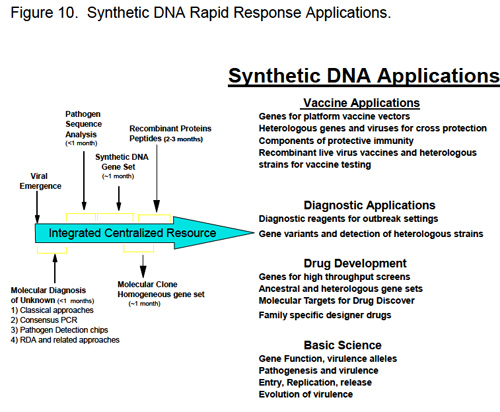

A major advantage is in the development of rapid response networks to prevent the spread of new emerging diseases. Platform technologies allow for rapid detection and sequencing of new emerging pathogens. The SARS-CoV was rapidly identified as a new coronavirus by gene discovery arrays and whole genome sequencing techniques within a month after spread outside of China (37, 46, 83, 84). Similar advances were also made in the identification of highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza strains, hendra virus and in other outbreaks. Sequence information allowed for immediate synthesis of SARS and H5N1 structural genes for vaccines and diagnosis and the rapid development of candidate vaccines and diagnostic tools within a few months of discovery. Classic recombinant DNA approaches requires template nucleic acid from infected cells and tissues (limited supply), followed by more tedious cloning and sequence analysis in independent labs throughout the world. As access to viral nucleic acids historically limited response efforts to only a few groups globally, research productivity was stifled. Synthetic biology results in a true paradigm shift in virus vaccine, therapeutic and diagnostic discovery, resulting in the near simultaneously engagement of multiple laboratories as genome sequence becomes available (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Synthetic DNA Rapid Response Applications.

Figure 10. Synthetic DNA Rapid Response Applications. Genome sequence provides for rapid incorporation of synthetic genes into platform technologies that allow for rapid diagnosis and epidemiologic characterization of the incidence, prevalence and distribution of new pathogens in human and animal hosts. Synthetic genes can be immediately incorporated into recombinant virus or bacterial vaccine platforms and tested in animal models and/or humans. Synthetic genes and proteins become essentially immediately available for structural studies, for high throughput identification of small molecule inhibitors and for the rational design of drugs. Synthetic full length molecular clones become available for genetic analysis of virus pathogenicity and replication, construction of heterotypic strains for vaccine and drug testing, rapid development of recombinant viruses containing indicator genes for high-throughput screens and for the development of live attenuated viruses as vaccines or seed stocks for killed vaccines.

Thus, the availability of synthetic genes and genomes provides for rapid development of candidate drugs and vaccines, although significant bureaucratic hurdles must be overcome to allow for rapid use in vulnerable human populations. We note that highly pathogenic respiratory viruses can be rapidly distributed worldwide, providing only limited opportunities and time for the prevention of global pandemics and the preservation of the overall public health.

B. Risks to Society

1. BioterrorismThe historical record clearly shows that many nations have had biological weapons programs (of varying degrees of development) throughout the 20th century including many European nations, the USSR and the United States, Japan and Iraq. From relatively unscientific programs early in the 20th century, progressively more sophisticated scientific programs developed during WWI and the Cold War. There is little doubt that the genomics revolution could stimulate a new generation of potential program development (27, 76). It is also well established that the biological revolution, coupled with advances in biotechnology could be used to enhance the offensive biological properties of viruses simply by altering resistance to antiviral agents (e.g., herpes viruses, poxviruses, influenza), modifying antigenic properties (e.g, T cell epitopes or neutralizing epitopes), modifying tissue tropism, pathogenesis and transmissibility, “humanizing” zoonotic viruses, and creating designer super pathogens (27, 59). These bioweapons could be targeted to humans, domesticated animals or crops, causing a devastating impact on human civilization. Moreover, applications of these approaches are certainly not limited to the list of pathogens recorded throughout this report—well developed engineering tools have been developed for only a few BW agents, making them relatively poor substrates for biodesign. A clever bioterrorist might start with a relatively benign, easily obtainable virus (BSL2) and obtain an existing molecular clone by simply requesting it from the scientists who work with these agents. Then, using the expanding database of genomic sequences and identified virulence genes, the benign viral genome could be modified into more lethal combinations for nefarious use.

As recombinant DNA approaches, infectious DNA clones and the general methods needed to bioengineer RNA and DNA viruses have been available since the 1980-1990’s, what new capabilities does synthetic biology bring to a biowarrior’s arsenal? Clearly, recombinant viral genomes and bioweapon design can be accomplished using either or a combination of both approaches, suggesting that synthetic biology will have little impact on the overall capabilities of bioweapons research. However, synthetic biology provides several attractive advantages as compared with standard recombinant DNA approaches; specifically 1) speed, 2) mutagenic superiority, 3) ease of genome construction and 4) low cost. The main paradigm shift may be that the approach is less technically demanding and more design-based, requiring only limited technical expertise because the genome can be synthesized and purchased from commercial vendors, government sponsored facilities, or from rogue basement operations (e.g., bioterrorist sponsored or private entrepreneur). Main technical support might include a competent research technician and minimal equipment to isolate recombinant pathogens from the recombinant DNAs.

Standard recombinant DNA techniques are hands-on, laborious and slow, requiring multiple rounds of mutagenesis and sequence validation of the final product. At the end of this effort, there is no guarantee that the designer or synthetic genome will function as intended (see other sections), dictating the need for high throughput strategies.

Synthetic genomes can be devised fairly rapidly using a variety of bioinformatics tools and purchased fairly cheaply ($1.10/base at current rates), allowing for rapid production of numerous candidate bioweapons that can be simultaneously released (e.g., survival of the fittest approach) or lab tested and then the best candidate used for nefarious purposes. The latter approach assumes that an organization has funded the development of a secure facility, has provided trained personnel and is willing to test the agents and/or passage them in humans, as animal models may be unreliable predictors of human pathogenesis. Assuming the technology continues to advance and spread globally, synthetic biology will allow for rapid synthesis of large designer genomes (e.g., ~30 Kb genome in less than a couple of weeks); larger genomes become technically more demanding. It seems likely that a standard approach could be designed for recovering each synthetic virus, further minimizing the need for highly trained personnel.

Will synthetic or recombinant bioweapons be developed for BW use? If the main purpose is to kill and inspire fear in human populations, natural source pathogens likely provide a more reliable source of starting material. Stealing the BW agent from a laboratory or obtaining the pathogen from natural outbreak conditions is still easier than the synthetic reconstruction of a pathogenic virus. These conditions, however, change as 1st and 2nd generation candidate vaccines and drugs are developed against this select list of pathogens, limiting future attempts to newly emerged viruses. If notoriety, fear and directing foreign government policies are principle objectives, then the release and subsequent discovery of a synthetically derived virus bioweapon will certainly garner tremendous media coverage, inspire fear and terrorize human populations and direct severe pressure on government officials to respond in predicted ways.

2. Prospects for Designer Super PathogensAdvances in genomics may provide new approaches for mixing and matching genetic traits encoded from different viral pathogens, as over 1532 genome length sequences are available in Genbank. A large number of recombinant viruses have been assembled using reverse genetic approaches including chimeric flaviviruses, chimeric enteroviruses and coronaviruses, HIV, lentiviruses and others usually for the purposes of generating vaccines or dissecting basic questions about, e.g., viral metabolism (29, 34, 39, 40, 50). Importantly, recombinant viruses are actively being designed with programmed pathogenic traits as a means of controlling certain insect and animal pests, providing both theoretical and practical strategies for conducting effective biowarfare (53, 69). More importantly, the identification of numerous virus virulence genes that target the innate immune response (e.g., interferons, tumor necrosis factors, interleukins, complement, chemokines, etc.), apoptosis (programmed cell death) and other host signaling pathways provides a gene repository that can be used to potentially manage virus virulence (5, 8, 9, 26, 70). Poxviruses and Herpes viruses, for example, encode a suite of immune evasion genes and pro-apoptotic genes (48, 54). More recently, virus encoded microRNAs were identified in Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) and other herpes viruses, which function to silence specific cellular mRNAs or repress translation of host genes that function in cell proliferation, apoptosis, transcription regulators and components of signal transduction pathways (62). Although the function of many viral micro-RNAs are unknown, it is likely that they regulate protein coding gene expression in animals and influence pathogenesis (61). Moreover, microRNAs could also be designed and targeted to downregulate specific human signaling pathways.

The identification of virulence alleles is traditionally a first step to attenuating virus virulence. However, highly virulent murine pox virus (ectromelia) were recovered after the host IL-4 gene was incorporated into the genome. IL-4 expression altered the host Th1/Th2 immune response leading to severe immunosuppression of cellular immune responses, high viremias, and increased pathogenesis following infection. The recombinant virus was lethal in both control and in immunized or therapeutically treated mice (33, 67). More troubling was the belated recognition that this outcome could have been predicted based on our understanding of pox molecular virology and pathogenesis, suggesting that increased virulence can be rationally modeled into existing pathogens (55) and subsequent extension of these findings to other, but not all animal poxviruses (75). Many key questions remain unanswered regarding the ability to translate results with inbred mouse strains and murine poxviruses to outcome responses in outbred human populations infected with recombinant human poxviruses. Today, these outcomes cannot be predicted. Is it possible to enhance virulence by recombinant DNA approaches in other virus families and animal models? The influenza NS1 gene (an interferon antagonist gene) also enhances the replication efficiency of avian Newcastle disease virus in human cells (57), although the in vivo pathogenesis of these isolates has not been evaluated.

More recently the SARS-CoV ORF6, but not the ORF3a group specific antigens (specific proteins of the virus) were shown to enhance mouse hepatitis virus virulence in inbred mice strains. The mechanism by which the SARS-CoV ORF6 product enhances MHV virulence is not known at this time (60). Finally, viral gene discovery and sequence recovery using DNA microarrays will greatly increase the electronic availability of sequences from many novel human, animal and insect viruses (83, 84). This revolution in pathogen detection, coupled with rapid genome sequencing, provides a rich parts list for designing novel features into the genome of viruses.

Another approach might be to “humanize” zoonotic viruses by inserting mutations into virus attachment proteins or constructing chimeric proteins that regulate virus species specificity (viral attachment proteins bind receptors, mediating virus docking and entry into cells). For example, the mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) attachment protein, the S glycoprotein, typically targets murine cells and is highly species specific. Recombinant viruses contain chimeric S glycoproteins that are composed of the ecto-domain of a feline coronaviruses fused with the c-terminal domain of MHV S glycoproteins targets feline, not murine cells for infection. The pathogenicity of these chimeric coronaviruses is unknown (39). As information regarding the structure and interactions between virus attachment proteins and their receptors accumulate, data will provide detailed predictions regarding easy approaches to humanize zoonotic strains by retargeting the attachment proteins to recognize human, not the animal receptors (43-45). Conversely, it is not clear whether species retargeting mutations will result in viruses that produce clinical disease in the human host.

Synthetic DNAs and systematic assembly approaches also provide unparalleled power for building genomes of any given sequence, simultaneously providing novel capabilities for nefarious use. For example, genome sequences represent fingerprints that allow geographic mapping of the likely origin of a given virus. Recombinant viruses generated from classic recombinant DNA techniques will carry the signature of the parental virus used in the process as well as novel restriction sites that were engineered into the genome during the cloning process. In contrast, synthetic viral genomes can be designed to be identical with exact virus strains circulating in any given location from any year. This powerful technique provides the bioterrorist with a “scapegoat” option; leaving a sequence signature that misdirects efforts at tracking the true originators of the crime. Even better, the approach could be used to build mistrust and/or precipitate open warfare between nations. A simple example might involve the use of the picornavirus foot and mouth disease virus, which is not present on the North American continent, yet is endemic in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and South America. North American herds are not vaccinated against this pathogen, the virus is highly contagious, and the disease is subject to international quarantine. Geographically distinct FMDV strains contain unique sequence signatures allowing ready determination of origin. A North American outbreak of an infectious “synthetic” FMDV virus containing signature sequences reminiscent of strains found in select Middle East or Asian nations that are viewed as terrorist states by the US government would inflame worsening tensions and could provide a ready excuse for military retaliation. Project costs would likely be less than $50K, including synthesis, recovery and distribution. Another possibility may be to optimize replication efficiency by optimizing for human codon use, especially useful in “humanizing” zoonotic viruses although to our knowledge codon optimization has never been linked to increased replication or pathogenesis. In both examples, standard recombinant DNA approaches would be difficult and tedious, while synthetically derived genomes could be readily manufactured within weeks.

Virus pathogenesis is a complex phenotype governed by multiple genes and is heavily influenced by the host genetic background. Virus genes influence virus-receptor interaction, tissue tropism, virus-host interactions within cells, spread throughout the host, virion stability and transmission between hosts. Colonization of hosts is influenced by ecologic factors including herd immunity, cross immunity and host susceptibility alleles. In general, the rules governing virulence shifts are hard to predict because of the lack of research and ethical concerns that have historically limited this type of research. In fact, the research itself promotes an emerging conundrum as to the limits of biodefense research: the need to know to protect the overall public health versus the development of models to elucidate the fundamental principles of pathogen design (4). Synthetic biology and recombinant DNA approaches provide numerous opportunities to construct designer pathogens encoding a repertoire of virulence genes from other pathogens, while simultaneously providing a rapid response network for preventing the emergence and spread of new human and animal diseases. The state of knowledge prevents accurate predictions regarding the pathogenic potential of designer viruses; most likely, replication and pathogenesis would be attenuated. As a principle goal of bioterrorism is to inspire fear, highly pathogenic outcomes may not be necessary as large scale panic would likely result after the release of designer pathogens in US cities. Given the reported findings and the large repertoire of host, viral and microbial virulence genes identified in the literature, the most robust defense against the development of designer viral pathogens for malicious use is basic research into the mechanisms by which viral pathogenesis might be manipulated and applied counter measures that ameliorate these pathogenic mechanisms. This justification, however, blurs the distinction between fundamental academic research and bio-weapon development.

3. Ancient Pathogen ResurrectionPaleomicrobiology is an emerging field dedicated to identifying and characterizing ancient microorganisms in fossilized remains (25). Mega-genomic high throughput large scale sequencing of DNA isolated from mammoths preserved in the permafrost not only identified over 13 million base pairs of mammoth DNA sequence, but also identified novel bacterial and 278 viral sequences that could be assigned to dsDNA viruses, retroviruses and ssRNA viruses (63). Although DNA genomes can survive for almost 20,000 years (25), RNA virus fossil records do not exist beyond a ~90-100 year window, making it difficult to understand the evolution of virulence, molecular evolution, and the function of modern day viral genes. Among RNA viruses, the current record is the molecular resurrection of the highly pathogenic 1918 influenza virus, which required almost 10 years of intensive effort using standard recombinant DNA approaches from many laboratories (81). Obviously, synthetic reconstruction of ancient viral genomes may provide a rapid alternative as sequence database grow more robust over the next few decades. How pathogenic are these ancient pathogens? Will vaccines and anti-virals protect humans from ancient virus diseases?

Moreover, alternative approaches also exist to regenerate ancient viral sequences. Ancestral gene resurrection using bioinformatics approaches offers a powerful approach to experimentally test hypotheses about the function of genes from the deep evolutionary past (79). Using phylogenetic methods (38), ancestral sequences can be inferred but the approach suffers from the lack of empirical data to refute or corroborate the robustness of the method. More recently, the sequence of ancestral genes was accurately predicted as evidenced by the synthetic reconstruction of a functional ancestral steroid receptor, Archosaur visual pigment and other genes (15, 16, 79, 80). To our knowledge, phylogenic reconstruction of ancient virus sequences has not been tested empirically but it may be possible to construct replacement viruses encoding ancient structural genes from inferred sequence. Such viruses would have unpredictable pathogenicity, but would likely be highly resistant to vaccines and therapeutics targeted to modern day strains.

4. SummaryChemical synthesis of viral genomes will become less tedious over the coming years. Costs will likely decrease as synthesis capabilities increase. Moreover, the technology to synthesize DNA and reconstruct whole viral genomes is spreading across the globe with dozens of commercial outfits providing synthetic DNAs for research purposes. DNA synthesizers can be purchased through on-line sites such as eBay. It is likely that engineering design improvements will allow for simple construction of larger genomes. The technology to synthetically reconstruct genomes is fairly straightforward and will be used, if not by the United States, then by other Nations throughout the world. It is also likely that synthetic genes and synthetic life forms will be constructed for improving the human condition and they will be released into the environment. As with most technology, synthetic biology contains risks and benefits ranging from a network to protect the public health from new emerging diseases to the development of designer pathogens. Synthetic genome technology will certainly allow for greater access to rare viral pathogens and allow for the opportunity to attempt rationale design of super pathogens. It is likely that the threat grows over time, as technology and information provide for more rational genome design. The most robust defense against the development of designer viral pathogens for malicious use may be basic research into the mechanisms by which viral pathogenesis might be manipulated so that applied counter- measures can be developed.

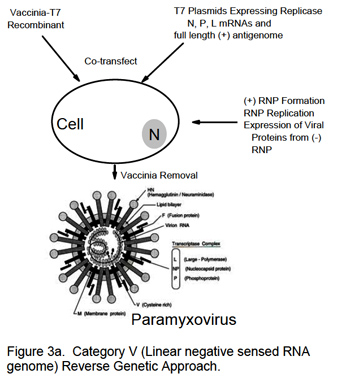

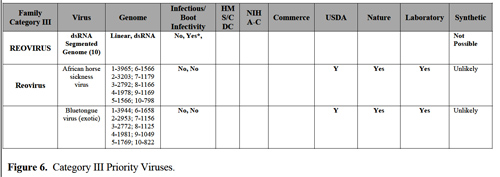

Addendum (November 2007): Since the writing of this initial report, recent studies have demonstrated the availability of a reverse genetic systems for reovirus, a group III dsRNA virus (Kobayashi T, Antar AA, Boehme KW, Danthi P, Eby EA, Guglielmi KM, Holm GH, Johnson EM, Maginnis MS, Naik S, Skelton WB, Wetzel JD, Wilson GJ, Chappell JD, Dermody TS. A plasmid-based reverse genetics system for animal double-stranded RNA viruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2007 Apr 19;1(2):147-57) and for additional group V single stranded negative polarity RNA viruses like Rift Valley Fever Virus (Ikegami T, Won S, Peters CJ, Makino S. Rescue of infectious rift valley fever virus entirely from cDNA, analysis of virus lacking the NS gene, and expression of a foreign gene. J Virol. 2006 Mar;80(6):2933-40.)

***

Appendix 1. EHS/CDC Select Agent List (Viruses)1. African horse sickness virus 1

2. African swine fever virus 1

3. Akabane virus 1

4. Avian influenza virus (highly pathogenic) 1

5. Blue tongue virus (exotic) 1

6. Camel pox virus 1

7. Cercopithecine herpes virus (Herpes B virus) 3

8. Classical swine fever virus 1

9. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus 3

10. Eastern equine encephalitis virus 2

11. Ebola viruses 3

12. Foot and mouth disease virus 1

13. Goat pox virus1

14. Japanese encephalitis virus 1

15. Lassa fever virus 3

16. Lumpy skin disease virus 1

17. Malignant catarrhal fever 1

18. Marburg virus 3

19. Menangle virus 1

20. Monkey pox virus 1

21. Newcastle disease virus (exotic) 1

22. Nipah and Hendra complex viruses 2

23. Peste des petits ruminants 1

24. Plum pox potyvirus4

25. Rift Valley fever virus 2

26. Rinderpest virus 1

27. Sheep pox 1

28. South American haemorrhagic fever viruses (Junin, Machupo, Sabia, Flexal, Guanarito) 3

29. Swine vesicular disease virus 1

30. Tick-borne encephalitis complex (flavi) viruses (Central European Tick-borne encephalitis, Far Eastern Tick-borne encephalitis, Russian Spring and Summer encephalitis, Kyasanur Forest disease, Omsk Hemorrhagic Fever) 3

31. Variola major virus (Smallpox virus) and Variola minor (Alastrim) 3

32. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus 2

33. Vesicular stomatitis virus (exotic) 1

34. Reconstructed replication competent forms of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus containing any portion of the coding regions of all eight gene segments (Reconstructed 1918 Influenza virus)

Prions1. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy agent (USDA High Consequence Livestock Pathogens or Toxin)

_______________

Notes:1USDA High Consequence Livestock Pathogens or Toxin

2USDA/HSS Overlap Agent

3HHS Select Infectious Agent

4APHIS Plant Pathogens (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, a division of USDA)

***

Appendix II. US Department of Commerce-Pathogen and Zoonotic virus list a. Viruses:a.1. Chikungunya virus;

a.2. Congo-Crimean haemorrhagic fever virus;

a.3. Dengue fever virus;

a.4. Eastern equine encephalitis virus;

a.5. Ebola virus;

a.6. Hantaan virus;

a.7. Japanese encephalitis virus;

a.8. Junin virus;

a.9. Lassa fever virus

a.10. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus;

a.11. Machupo virus;

a.12. Marburg virus;

a.13. Monkey pox virus;

a.14. Rift Valley fever virus;

a.15. Tick-borne encephalitis virus (Russian Spring-Summer encephalitis virus);

a.16. Variola virus;

a.17. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus;

a.18. Western equine encephalitis virus;

a.19. White pox; or

a.20. Yellow fever virus.

***

References1. Almazon F, G. J., Penzes Z, Izeta A, Calvo E, Plana-Durin J, Enjuanes L. 2000. Engineering the largest RNA virus genome as an infectious bacterial artifical chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:5516-5521.

2. Alquist, P., and e. al. 1984. PNAS USA 81:7066-7070.

3. Anthony, L. C., H. Suzuki, and M. Filutowicz. 2004. Tightly regulated vectors for cloning and expression of toxic genes. J. Microbiol. Methods 58:243-250.

4. Atlas, R. M. 2005. Biodefense research: an emerging conundrum. Curr Opinion in Biotechnology 16:239-242.

5. Aubert, M., and K. R. Jerome. 2003. Apoptosis prevention as a mechanism of immune evasion. Int Rev Immunol 22:361-371.

6. Ball, P. 2004. Starting from Scratch. Nature 431:624-626.

7. Baric, R., Yount, B, Lindesmith, L., Harrington, PR, Greene, SR, Tseng, F-C, Davis, N., Johnston, RE, Klapper, DG and Moe, CL. 2002. Expression and self-assembly of norwalk virus capsid protein from venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicons. Journal of Virology 76:3023-3030.

8. Basler, C. F., and A. Garcia-Sastre. 2002. Viruses and the type I interferon antiviral system: induction and evasion. Int Rev Immunol 21:305-337.

9. Basler, C. F., A. Mikulasova, L. Martinez-Sobrido, J. Paragas, E. Muhlberger, M. Bray, H. D. Klenk, P. Palese, and A. Garcia-Sastre. 2003. The Ebola virus VP35 protein inhibits activation of interferon regulatory factor 3. J Virol 77:7945-7956.

10. Boyer JC, H. C. 1994. Infectious transcripts and cDNA clones of RNA viruses. Virology 198.

11. Brune, W., M. Messerie, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2000. Forward with Bacs: new tools for herpesvirus genomics. Trends in Genomics 16:254-259.

12. Brune, W., M. Messerle, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2000. Forward with BACs: new tools for herpesvirus genomes. Trends in Genetics 16:254-258.

13. Casais R, T. V., Siddell SG, Cavanagh D, Britton P. 2001. Reverse genetic system for the avian coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. J Virol 75:12359-12369.

14. Cello J., P. A., Wimmer E. 2002. Chemical synthesis of poliovirus cDNA: generation of infectious virus in the absence of natural template. Science 297:1016-1018.

15. Chang, B. S., M. A. Kazmi, and T. P. Sakmar. 2002. Synthetic gene technology: applications to ancestral gene reconstruction and structure-function studies of receptors. Methods Enzymology 343:274-294.

16. Chang, B. S. W., Jonsson K., M. A. Kazmi, M. J. Donoghue, and T. P. Sakmar. 2002. Recreating a functional ancestral archosaur visual pigment. Mol. Biol. Envol. 19:1483-1489.

17. Chang, W. L. W., and P. A. Barry. 2003. Cloning of the full length Rhesus cytomegalovirus genome as an infectious and self-excisable BAC for analysis of viral pathogenesis. J. Viro. 77:5073-5083.

18. Clark, A. G., and T. S. Whittam. 1992. Sequencing errors and molecular evolutonary analysis. Mol. Biol. Envol. 9:744-752.

19. Consortium, C. S. M. E. 2004. Molecular Evolution of the SARS Coronavirus during the course of the SARS Epidemic in China. Science 303:1666-1669.

20. Conzelmann, K. K., and G. Meyers. 1996. Genetic engineering of animal RNA viruses. Trends in Microbiology 10:386-393.

21. Dara, S. I., R. W. Ashton, J. C. Farmer, and P. K. Carlton. 2005. Worldwide disaster medical response: an historic perspective. Crit Care med 33:S2-S6.

22. Dennis, C. 2001. The Bugs of War. Nature 411:232-235.

23. Domi, A., and B. Moss. 2002. Cloning the vaccinia virus genome as a BAC in E.coli and recovery of infectious virus in mammalian cells. PNAS USA 99:12415-12420.

24. Domi, A., and B. Moss. 2005. Engineering of a vaccinia virus bacterial artificial chromosome in E.coli by bacteriophage lamda-based recombination. Nature Methods 2:95-97.

25. Drancourt, M., and D. Raoult. 2005. Palaeomicrobiology: current issues and perspectives. Nature Reviews Microbiology 3:23-35.

26. Dunlop, L. R., K. A. Oehlberg, J. J. Reid, D. Avci, and A. M. Rosengard. 2003. Variola virus immune evasion proteins. Microbes Infect 5:1049-1056.

27. Fraser, C. M., and M. R. Dando. 2001. Genomics and future biological weapons: the need for preventive action by the biomedical community. Nature Genetics 29:253-256.

28. Goff, S. P., and P. Berg. 1976. Construction of hybrid viruses containing SV40 and lambda phage DNA segments and their propagation in cultured monkey cell. Cell 9:659-705.

29. Haijema, B. J., H. Volders, and P. J. Rottier. 2003. Switching species tropism: an effective way to manipulate the feline coronavirus genome. J. Virol. 77:4528-4538.

30. Harrington, P., Yount, B, Johnston, RE, Davis, N., Moe, C, and Baric, RS. 2002. Systemic, mucosal and heterotypic immune induction in mice inoculated with venezuelan equine encephalitis replicons expressing norwalk virus like particles. Journal of Virology 76:730-742.

31. Heymann, D. L., R. B. Aylward, and C. Wolff. 2004. Dangerous pathogens in the laboratory: from smallpox to today's SARS setacks and tomorrow's polio-free world. Lancet 363:1566-1568.

32. Hilleman, M. 2002. Overview: cause and prevention in biowarfare and bioterrorism. Vaccine 20:3055-3067.

33. Jackson, R. J., A. J. Ramsay, C. D. Christensen, S. Beaton, D. F. Hall, and I. A. Ramshaw. 2001. Expression of mouse interleukin-r by a recombinant ectromelia virus suppresses cytolytic lymphocyte responses and overcomes genetic resistance to mousepox. J Virol 75:1205-1210.

34. Khan, M., L. Jin, M. B. Huang, L. Miles, V. C. Bond, and M. D. Powell. 2004. Chimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) virions containing HIV-2 or simian immunodeficiency virus Nef are resistant to cyclosporine treatment. J. Virol. 78:1843-1850.

35. Kiewiet, K., J. Kok, J. F. M. L. Seegers, G. Venema, and S. Bron. 1993. The mode of replication is a major factor in segregational plasmid instability in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:358-364.

36. Krawetz, S. A. 1989. Sequence errors described in GenBank: a means to determine the accuracy of DNA sequence interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res 17:3951-3957.

37. Ksiazek TG, E. D., goldsmith C, Zaki SR, Peret T, emery S, Tong S, Urgani C, et al. 2003. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine:epub.

38. Kunin, V., and C. A. Ouzounis. 2003. GeneTRACE-reconstruction of gene content of ancestral species. Bioinformatics 19:1412-1416.

39. Kuo, L., G. J. Godeke, M. J. Raamsman, P. S. Masters, and P. J. Rottier. 2000. Retargeting of coronavirus by substitution of the spike glycoprotein ectodomain: crossing the host cell species barrier. J Virol 74:1393-406.

40. Lai, C. J., and T. P. Monath. 2003. Chimeric flaviviruses: novel vaccines against dengue fever, tick-borne encephalitis, and Japanese encephalitis. Adv. Virus Res. 61:469-509.

41. Lau, S. K., P. C. Woo, K. S. Li, Y. Huang, H. W. Tsoi, B. H. Wong, S. S. Wong, S. Y. Leung, K. H. Chan, and K. Y. Yuen. 2005. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. PNAS USA 102:14040-14045.

42. Li, F., W. Li, M. Farzan, and S. C. Harrison. 2005. Structure of SARS Coronavirus Spike Receptor-Binding Domain Complexed with Receptor. Science 309:1864-1868.

43. Li, W., T. Greenough, M. Moore, N. Vasilieva, M. Somasundaran, J. Sullivan, M. Farzan, and H. Choe. 2004. Efficient replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in mouse cells is limited by murine angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Virol. 78:11429-33.

44. Li, W., M. Moore, N. Vasilieva, J. Sui, S. K. Wong, M. A. Berne, M. Somasundaran, J. L. Sullivan, K. Luzuriaga, T. C. Greenough, H. Choe, and M. Farzan. 2003. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426:450-454.

45. Li, W., C. Zhang, J. Sui, J. H. Kuhn, M. J. Moore, S. Luo, S.-K. Wong, I.-C. Huang, K. Xu, N. Vasilieva, A. Murakami, Y. He, W. A. Marasco, Y. Guan, H. Choe, and M. Farzan. 2005. Receptor and viral determinants of SARS-coronavirus adaptation to human ACE2. Embo J March 24, Epub:1-10.

46. Marra MA, J. S., Astell CR, Holt RA, Brooks-Wilson A, Butterfield YSN, Khattra J, Asano JK et al. 2003. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science 300:1399-404.

47. Massung, R. F., J. J. Esposito, L.-I. Liu, J. Qi, T. R. Utterback, J. C. Knight, L. Aubin, T. E. Yuran, J. M. Parsons, V. N. Loparev, N. A. Selivanov, K. F. Cavallaro, A. R. Keriavage, B. W. J. Mahy, and J. C. Venter. 1993. Potential virulence determinants in terminal regions of variola smallpox virus genome. Nature:748-751.

48. McFadden, G., and P. M. Murphy. 2000. Host related immunomodulators encoded by poxviruses and herpes viruses. Curr Opinion in Microbiology 3:371-378.

49. McGregor, A., and M. R. Schleiss. 2001. Recent Advances in Herpes virus Genetics using Bacterial Artifical Chromosomes. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 72:8-14.

50. McKnight, K. L., S. Sandefur, K. M. Phipps, and B. A. Heinz. 2003. An adenine to guanine nucleotide change in the IRES SL-IV domain of picoronavirus/hepatitis C chimeric viruses leads to a nonviable phenotype. Virology 317:345-358.

51. Morens, D. M., G. K. Fokers, and A. S. Fauci. 2004. The challenge of emerging and reemerging infectious diseases. Nature 430:242-249.

52. Moroziewicz, D., and H. L. Kaufman. 2005. Gene therapy with poxvirus vectors. curr Opin Mol Ther. 4:317-325.

53. Moscardi, F. 1999. Assessment of the application of baculoviruses for control of Lepidoptera. Annu Rev Entomol 44:257-289.

54. Moss, B., and J. L. Shisler. 2001. Immunology 101 at poxvirus U: Immune evasion genes. Seminars in Immunology 13:59-66.

55. Mullbacher, A., and M. Lobigs. 2001. Creation of Killer Poxvirus Could have been predicted. J. Virology 75:8353-8355.

56. Nabel, G. J. 2004. Genetic, cellular and immune approaches to disease therapy: past and future. Nat Med 10:135-141.

57. Park, M. S., A. Garcia-Sastre, J. F. Cros, and P. Palese. 2003. Newcastle disease virus V protein is a determiant of host range restriction. J. Virol. 77:9522-9532.

58. Perez-Arellano, I., M. Zuniga, and G. Perez-Martinez. 2001. Construction of compatible wide host range shuttle vectos for lactic acid bacteria and E.coli. Plasmid 46:106-116.

59. Petro, J. B., T. R. Plasse, and J. A. McNulty. 2003. biotechnology: Impact on biological warfare and biodefense. Biosecurity and bioterrorism: Biodefense strategy, practice and science 1:161-168.

60. Pewe, L., H. Zhou, J. Netland, C. Tangudu, H. Olivares, L. Shi, D. Look, T. Gallagher, and S. Perlman. 2005. A severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus specific protein enhances virulence of an attenuated murine coronavirus. J. Virol. 79:11335-11342.

61. Pfeffer, S., A. Sewer, M. Lagos-Quintana, R. Sheridan, C. Sander, F. A. Grasser, L. F. van Dyke, C. K. Ho, and e. al. 2005. Identification of microRNAs of the herpesvirus family. Nature Methods 2:269-275.

62. Pfeffer, S., M. Zavolan, F. A. Grasser, M. Chien, J. J. Russo, J. Ju, B. John, A. J. Enright, D. Marks, C. Sandler, and T. Tuschl. 2004. Identification of virus encoded microRNAs. Science 304:734-736.

63. Poinar, H. N., C. Schwarz, J. Qi, B. Shapiro, R. D. E. MacPhee, B. Buigues, A. Tithonov, D. H. Huson, L. P. Tomsho, A. Auch, M. Rampp, W. Miller, and S. C. Schuster. 2006. Metagenomicsw to paleogenomics: large scale sequencing of mammoth DNA. Science 311:392-394.

64. Raab, R. M., K. Tyo, and G. Stephanopoulos. 2005. Metabolic engineering. Adv. biochem. Eng. biotechnol. 100:1-7.

65. Racaniello, V. R., and D. Baltimore. 1981. Cloned poliovirus complementary DNA is infectious in mammalian cells. Science 214:916-919.

66. Racaniello, V. R., and D. Baltimore. 1981. Molecular cloning of poliovirus cDNA and determination of the complete nucleotide sequence of the viral genome. PNAS USA 78:4887-4891.

67. Robbins, S. J., R. J. Jackson, F. Fenner, S. Beaton, j. Medveczky, I. A. Ramshaw, and A. J. Ramsay. 2005. The efficacy of cidofovir treatment of mice infected with ectromelia (mousepox) virus encoding interleukin-4. Antiviral Res 66:1-7.

68. Schnell, M. J., T. Mebatsion, and K. K. Conzelmann. 1994. Infectious rabies viruses from cloned cDNA. Embo J 13:4195-4205.

69. Seamark, R. F. 2001. Biotech prospects for the control of introduced mammals in Australia. Reprod Fertil Dev 13:705-711.

70. Seet, B. T., J. B. Johnston, C. R. Brunetti, J. W. Barrett, H. Everett, C. Cameron, J. Sypula, S. H. Nazarian, A. Lucas, and G. McFadden. 2003. Poxviruses and immune evasion. Annu Rev Immunol 21:377-423.

71. Smith, G. A., and L. W. Enquist. 1999. Construction and transposon mutagenesis in e.coli of a full-length infectious clone of pseudorabies virus, an alphavherpesvirus. J. Virol. 73:6405-6414.

72. Smith, G. A., and L. W. Enquist. 2000. A self-recombining BAC and its application for analysis of herpesvirus pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:4873-4878.

73. Smith HO., H. C., Pfannkoch C., Venter JC. 2003. Generating a synthetic genome by whole genome assembly: phiX174 bacteriophage from synthetic oligonucleotides. PNAS USA 100:15440-15445.

74. Sperry, S. M., L. Kazi, R. L. Graham, R. S. Baric, S. Weiss, and M. R. Denison. 2005. Single amino acid substitutions in open reading frame 1b and orf2 proteins of the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus are attenuating in mice. J. Viro. 79:3391-4000.

75. Stanford, M. M., and G. Mcfadden. 2005. The 'supervirus'? Lessons from IL-4 expressing poxviruses. Trends in Biotechnology 26:339-345.

76. Szinicz, L. 2005. History of chemical and biological warfare agents. Toxicology 214:167-181.

77. Thiel, V., J. Herold, B. Schelle, and S. G. Siddell. 2001. Infectious RNA transcribed in vitro from a cDNA copy of the human coronavirus genome cloned in vaccinia virus. J Gen Virol 82:1273-81.

78. Thomas, W. R., B. J. Hales, and W. A. Smith. 2005. Genetically engineered vaccines. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 3:197-203.

79. Thornton, J. W. 2004. Ressurecting ancient genes: experimental analysis of extinct molecules. Nat Rev Genet 5:366-375.

80. Thornton, J. W., E. Need, and D. Crews. 2003. Resurrecting the ancestral steroid receptor: ancient origin of estrogen signaling. Science 301:1714-1717.

81. Tumpey, T. M., C. F. Basler, P. V. Aguilar, H. Zeng, A. Solórzano, D. E. Swayne, N. J. Cox, J. M. Katz, J. K. Taubenberger, P. Palese, and A. García- Sastre. 2005. Characterization of the Reconstructed 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic Virus. Science 310:77-80.

82. Walpita, P., and R. Flick. 2005. Reverse genetics of negative strand RNA viruses: A global perspective. FEMS Microbiology Letters 244:9-18.

83. Wang, D., L. Coscoy, M. Zylberberg, P. C. Avila, H. a. Boushey, D. Ganem, and J. L. DeRisi. 2002. Microarray-based detection and genotyping of viral pathogens. PNAS USA 99:15687-15692.

84. Wang, D., A. Urisman, Y.-T. Liu, T. G. Ksiazek, D. D. Erdman, E. R. Mardis, M. Hickenbotham, and et. al. 2003. Viral discovery and sequence recovery using DNA microarrays. PLoS Biology 1:257-260.

85. Yount, B., C. Curtis, and R. S. Baric. 2000. A strategy for the assembly of large RNA and DNA genomes: the transmissible gastroenteritis virus model. J. Virology 74.

86. Yount, B., Denison MR, Weiss, SR and Baric RS. 2002. Systematic assembly of a full-length infectious cDNA of mouse hepatitis virus strain A59. J. Virol. 76:11065-11078.

87. Yount, B., K Curtis, E Fritz, L Hensley, PJahrling, E Prentice, M Denison, T Geisbert and R Baric. 2003. Reverse genetics with a full length infectious cDNA of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:12995-13000.

_______________

Notes:1 Named for the virologist David Baltimore, who proposed the system.