Re: Three Years in Tibet, by Ekai Kawaguchi

CHAPTER LVI. Tibetan Punishments.

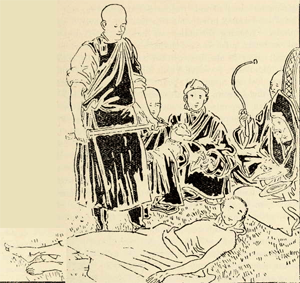

One day early in October I left my residence in Lhasa and strolled toward the Parkor. Parkor is the name of one of the principal streets in that city, as I have already mentioned, and is the place where criminals are exposed to public disgrace. Pillory in Tibet takes various forms, the criminal being exposed sometimes with only handcuffs, or fetters alone, and at others with both. On that particular occasion I saw as many as twenty criminals undergoing punishment, some of them tied to posts, while others were left fettered at one of the street crossings. They were all well-dressed, and had their necks fixed in a frame of thick wooden boards about 1⅕ inches thick, and three feet square. The frame had in the centre a hole just large enough for the neck and was composed of two wooden boards fastened together by means of ridges, and a lock. From this frame was suspended a piece of paper informing the public of the nature of the crime committed by the exposed person, and of the judgment passed upon him, sentencing him to the pillory for a certain number of days and to exile or flogging afterwards. The flogging generally ranges from three hundred to seven hundred lashes. As so many criminals were pilloried on that particular occasion, I could not read all the sentences, even though my curiosity was stronger than the sense of pity that naturally rose in my bosom when I beheld the miserable spectacle. I confess that I read one or two of them, and found that the criminals were men connected with the Tangye-ling monastery, the Lama superior of which is qualified to succeed to the supreme power of the pontificate in case, for one reason or[375] another, the post of the Dalai Lama should happen to fall vacant. The monastery is therefore one of the most influential institutions in the Tibetan Hierarchy and generally contains a large number of inmates, both priests and laymen.

Shortly before my arrival in Lhasa this high post was occupied by a distinguished priest named Temo Rinpoche. His steward went under the name of Norpu Che-ring, and this man was charged with the heinous crime of having secretly made an attempt on the life of the Dalai Lama by invoking the aid of evil deities. Norpu Che-ring’s conjuration was conducted not according to the Buḍḍhist formula, but according to that of the Bon religion. A piece of paper containing the dangerous incantation was secreted in the soles of the beautiful foot-gear worn by the Dalai Lama, which was then presented to his Holiness. The incantation must have possessed an extraordinary potency, for it was said that the Grand Lama invariably fell ill one way or another whenever he put on these accursed objects. The cause of his illness was at last traced to the foot-gear with its invocation paper by the wise men in attendance on the Grand Lama.

This amazing revelation led to the wholesale arrest of all the persons suspected of being privy to the crime, the venerable Temo Rinpoche among the rest. Some people even regarded the latter as the ring-leader in this plot and denounced him as having conspired against the life of the Grand Lama in order to create for himself a chance of wielding the supreme authority. At any rate Temo Rinpoche occupied the pontifical seat as Regent before the present Grand Lama was installed on his throne. Norpu Che-ring was the Prime-Minister to the Regent, and conducted the affairs of state in a high-handed manner. Things were even worse than this, for it is a fact, admitting of no dispute, that Norpu was oppressive, and mer[376]cilessly put to death a large number of innocent persons. He was therefore a persona ingrata with at least a section of the public, and some of his enemies lost no time in giving a detailed denunciation of the despotic rule of the Regent and his Prime-Minister as soon as the present Grand Lama was safely enthroned. Naturally therefore the former Regent and his Lieutenant were not regarded with favor by the Grand Lama, and such being the case, the terrible revelation about the shoes was at once followed by their arrest, and they were thrown into prison.

All this had occurred before my arrival. When I came to Lhasa Temo Rinpoche had been dead for some time, but Norpu Che-ring was still lingering in a stone dungeon which was guarded with special severity, because of the grave nature of his crime. The dungeon had only one narrow hole in the top, through which food was doled out to the prisoner, or he himself was dragged out whenever he had to undergo his examinations, which were always accompanied with torture. Hope of escape was out of the question, and the only opportunity offered him of seeing the sunshine was by no means a source of relief, for it was invariably associated with the infliction of tortures of a terribly excruciating character. The mere description of it chilled my blood. The torture, as inflicted on Norpu Che-ring, was devised with diabolical ingenuity, for it consisted in driving a sharpened bamboo stick into the sensitive part of the finger directly underneath the nail. After the nail had been sufficiently abused as a means of torture, it was torn off, and the stick was next drilled in between the flesh and the skin. As even criminals possess no more than ten fingers on both hands the inquisitor had to make chary use of this stock of torture, and took only one finger at a time, till the whole number was disposed of. Such was the treatment the ex-Prime-Minister received at his hands.

Norpu Che-ring bore this torture with admirable fortitude; he persisted that the whole plot originated in him alone and was put in execution by his own hands only. His master had nothing to do with it. The inquisitors’ object in subjecting their former superior and colleague to this infernal torture was to extort from him a confession implicating Temo Rinpoche, but they were denied this satisfaction by the unflinching courage of their victim. It is said that this suffering of Norpu Che-ring had so far awakened the sympathy of Temo Rinpoche himself that the latter tried, like the priest of noble heart that he was, to take the whole responsibility of the plot upon his own shoulders, declaring that Norpu was merely a tool who carried out his orders, and that therefore the latter was entirely innocent of the crime. Temo even advised his steward, whenever the two happened to be together at the inquisition, to confess, as he, that is Temo, had done.

The steward, on his part, would reply that his master must have made that baseless confession from the benevolent motive of saving his, the steward’s life, but that he was not so mean and depraved as to seek an unmerited deliverance at the cost of his venerable master’s life. And so he preferred to suffer pain rather than to be released, and baffled all the attempts of the torturers. By the time I reached Lhasa Norpu had already endured this painful existence for two years, and during that long period not one word even in the faintest way implicating his master had passed his lips. From this it may be concluded that Temo had really no hand in the plot. At the same time it must be remembered that Temo was an elder brother of Norpu, and the fraternal affection which the latter entertained towards the other might therefore have been too strong to allow of his implicating Temo, even supposing that the late Regent was really privy to the plot. Be the real circumstances what they might, when[379] I heard all these painful particulars, my sympathy was powerfully aroused for Norpu, whatever hard words others might utter against him; for the mere fact that he submitted so long to such revolting punishments with such persevering fortitude and with such faithful constancy to his master and brother, appealed strongly to my heart.

The pilloried criminals whom I saw on that occasion were all subordinates of Norpu Che-ring. Besides these, sixteen Bon priests had been executed as accomplices, while the number of laymen and priests who had been exiled on the same charge must have been large, though the exact number was unknown to outsiders. The pilloried criminals were apparently minor offenders, for half of them were sentenced to exile and the remaining half to floggings of from three hundred to five hundred lashes. The pillory was to last in each case for three to seven days. Looking at these pitiable creatures I felt as if I were witnessing a sight such as might exist in the Nether World. My heart truly bled for the poor, helpless fellows.

Heavy with this sad reflexion I proceeded further on, and soon arrived at a place to the south of a Buḍḍhist edifice; and there, near the western corner of the building, flooded by sunshine, I beheld another heart-rending sight. It was a beautiful lady in the pillory. Her neck was secured in the regulation frame, just as was that of a rougher criminal, and the ponderous piece of wood was weighing heavily upon her frail shoulders. A piece of red cloth made of Bhūtān silk was upon her head, which hung very low, for the frame around her neck did not allow her to move it freely. Her eyes were closed. Three men, apparently police constables, were near by as guards. A vessel containing baked flour was lying there, and also some small delicacies that must have been sent by relatives or friends. All this food she had to take from the hands of one or other of the three rough attendants, for her own hands were manacled. She was none other than the wife of Norpu Che-ring, whose miserable story I have already told, and was a daughter of the house of Do-ring, one of the oldest and most respected families in the whole of the Tibetan aristocracy.

THE WIFE OF AN EX-MINISTER. PUNISHED IN PUBLIC.

When her husband was arrested, he was at first confined in a cell less terrible than the stone dungeon to which he was afterwards transferred. But this early and apparently more considerate treatment only plunged his family into greater misery. His wife was told that the jailer of the prison in which her husband was incarcerated was not overstrict and that he was open to corruption, and what faithful wife, even though Tibetan, would resist the temptation placed before her under such circumstances, of trying to seek some means of gaining admission to the lonely cell where her dear lord was confined? And so it came to pass that Madame Norpu bribed the jailer, and with his connivance was often at her husband’s side; but somehow her[381] transgression reached the ears of the government, and she also was thrown into prison.

On the very morning of the day on which I came upon this piteous sight of the pillory, she was led out of the prison, as I heard afterwards, not however for liberation, but first to suffer at the gate of the prison a flogging of three hundred lashes, and then to be conducted to a busy thoroughfare to be pilloried for public disgrace.

Poor woman! she seemed to be almost insensible when I saw her, and the mere sight of her emaciated form and death-pale face aroused my strongest sympathy. The sentiment of pity was intensified when I saw a group of idle spectators, among whom I even noticed some aristocratic-looking persons, gazing at the pillory with callous indifference. They were heartless enough to approach her place of torture and read the judgment paper. The sentence, as I heard it read aloud by these fellows, condemned her to so many whippings, then to seven days pillory, and lastly to exile at such-and-such a place, there to remain imprisoned, fettered and manacled. The spectators not only read out the sentence with an air of perfect indifference, but some of them even betrayed their depravity by reviling and jeering at the lady: “Serve her right,” I heard them say; “their hard treatment of others has brought them to this. Serve them right.” These aristocrats were giving sardonic smiles, as if gloating over the misery of the house of Norpu Che-ring.

Really the heartless depravity of these people was beyond description, and I could not help feeling angry with them. These same people, I thought, who seemed to take so much delight in the calamity of the family of Norpu Che-ring, must have vied with each other in courting his favor while he was in power and prosperity. Even if it were beyond the comprehension of these brutes to appreciate the meaning of that merciful principle which bids us “hate the offence[382] but pity the offender,” one would have expected them to be humane enough to show some sympathy towards this woman who was paying so dearly for her excusable indiscretion. But they seemed to be utterly impervious to such sentiments, and so behaved themselves in that shameful manner. I, who knew that political rivalry in Tibet was allowed to run to such an extreme as to involve even innocent women in painful punishment, felt sincerely sorry for the Lady Norpu, and returned to my residence with a heavy heart. My sentiment on that particular occasion is partially embodied in this uta that occurred to me as I retraced my heavy steps:

On my return, when I saw my host, the former Minister of Finance, I related to him what I had seen in the street, and asked him to tell me all he knew about the affair. He fully shared my sympathy for the unfortunate woman.

While Norpu Che-ring was in power, my host told me, he was held in high respect. Nobody dared to whisper one word of blame about him and his wife. Now they were fallen, and he felt really sorry for them. It was true, he continued, that some people used to find fault with the private conduct of Norpu Che-ring, and the former Minister could not deny that there was some reason for that. But Temo Rinpoche was a venerable man, pure in life, pious and benevolent, and had met with such a sad end solely in consequence of the wicked intrigues of his followers. My host was perfectly certain that Temo Rinpoche had absolutely no hand in the plot. He said that he could not talk thus to others; he could be confidential to me alone.

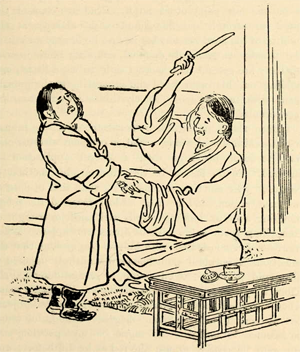

Tortures are carried to the extreme of diabolical ingenuity. They are such as one might expect in hell. One[383] method consists in drilling a sharpened bamboo stick into the tender part of the tip of the fingers, as already described. Another consists in placing ‘stone-bonnets’ on the head of the victim. Each ‘bonnet’ weighs about eight pounds, and one after another is heaped on as the torture proceeds. The weight at first forces tears out of the eyes of the victim, but afterward, as the weight is increased, the very eye-balls are forced from their sockets. Then flogging, though far milder in itself, is a painful punishment, as it is done with a heavy rod, cut fresh from a willow tree, the criminal receiving it on the bared small of his back. The part is soon torn open by the lashing, and the blood that oozes out is scattered right and left as the beater continues his brutal task, until the prescribed number, three hundred or five hundred blows as the case may be, are given. Very often, and perhaps with the object of prolonging the torture, the flogging is suspended, and the poor victim receives a cup of water, after which the painful process is resumed. In nine cases out of ten the victims of this corporeal punishment fall ill, and while at Lhasa I more than once prescribed for persons who, as the result of flogging, were bleeding internally. The wounds caused by the flogging are shocking to see, as I know from my personal observations.

A prison-house is in any case an awful place, but more especially so in Tibet, for even the best of them has nothing but mud walls and a planked floor, and is very dark in the interior, even in broad day. This absence of sunlight is itself a serious punishment in such a cold country.

As for food, prisoners are fed only once a day with a couple of handfuls of baked flour. This is hardly sufficient to keep body and soul together, so that a prisoner is generally obliged to ask his friends to send him some food. Nothing, however, sent in from outside reaches the[384] prisoners entire, for the gaolers subtract for their own mouths more than half of it, and only a small portion of the whole quantity gets into the prisoners’ hands.

The most lenient form of punishment is a fine; then comes flogging, to be followed, at a great distance, by the extraction of the eye-balls; then the amputation of the hands. The amputation is not done all at once, but only after the hands have been firmly tied for about twelve hours, till they become completely paralysed. The criminals who are about to suffer amputation are generally suspended by the wrists from some elevated object with stout cord, and naughty street urchins are allowed to pull the cord up and down at their pleasure. After this treatment the hands are chopped off at the wrists in public. This punishment is generally inflicted on thieves and robbers after their fifth or sixth offence. Lhasa abounds in handless beggars and in beggars minus their eye-balls; and perhaps the proportion of eyeless beggars is larger than that of the handless ones.

Then there are other forms of mutilation also inflicted as punishment, and of these ear-cutting and nose-slitting are the most painful. Both parties in a case of adultery are visited with this physical deformation. These forms of punishment are inflicted by the authorities upon the accusation of the aggrieved party, the right of lodging the complaint being limited, however, to the husband; in fact he himself may with impunity cut off the ears or slit the noses of the criminal parties, when taken in flagrante delicto. He has simply to report the matter afterwards to the authorities.

With regard to exile there are two different kinds, one leaving a criminal to live at large in the exiled place, and the other, which is heavier, confining him in a local prison.

Capital punishment is carried out solely by immersion in water. There are two modes of this execution: one by[385] putting a criminal into a bag made of hides and throwing the bag with its live contents into the water; and the other by tying the criminal’s hands and feet and throwing him into a river with a heavy stone tied to his body. The executioners lift him out after about ten minutes, and if he is judged to be still alive, down they plunge him again, and this lifting up and down is repeated till the criminal expires. The lifeless body is then cut to pieces, the head alone being kept, and all the rest of the severed members are thrown into the river. The head is deposited in a head vase, either at once, or after it has been exposed in public for three or seven days, and the vase is carried to a building established for this sole purpose, which bears a horrible name signifying “Perpetual Damnation.” This practice comes from a superstition of the people that those whose heads are kept in that edifice will forever be precluded from being reborn in this world.

All these punishments struck me as entirely out of place for a country in which Buḍḍhist doctrines are held in such high respect. Especially did I think the idea of eternal damnation irreconcilable with the principles of mercy and justice, for I should say that execution ought to absolve criminals of their offences. Several other barbarous forms of punishment are in vogue, but these I may omit here, for what I have stated in the preceding paragraphs is enough to convey some idea of criminal procedure as it exists in the Forbidden Land.

I stayed in Lhasa till about the middle of October 1901, when I decided to return to Sera. My host kindly placed at my disposal one of his horses and on this I jogged towards my destination. The snow had been falling since the previous evening, and already the road was covered with a thick layer of its crystal carpet. It was the first snow of the season. On the road from Lhasa to Sera,[386] by Shom-khe-Lamkha (priest’s road), there is a river about half a mile on this side of Sera. This river dries up in winter, and on the day I am speaking of its bed was covered with snow. There I noticed a party of five or six young priestlings of Sera, absorbed in the innocent sport of snowballing. This highly amused me, calling forth in my mind’s eye the sights I had frequently come across at home, and reminding me that human nature is, after all, very much alike the world over. And so these little fellows were pelting each other with soft missiles, running and pursuing, shouting and laughing, forgetting for once the stern reprimanding voices of their exacting masters, and I amused myself with composing an uta, as follows.

While I was watching the snow-fight, a burly fellow coming from the direction of Lhasa overtook me and began to stare at me. I at once recognised in him one of my old acquaintances, the youngest of the three brothers whom I accompanied on the pilgrimage round Lake Mānasarovara, who gave my face a sharp parting smack, as already told. He seemed to be quite astonished, even frightened, when he saw me, his whilom companion of humble attire, now transformed into an aristocratic-looking personage, such as I must have appeared to him. At any rate he avoided my eyes, and was about to walk off with hurried steps, when I bade him stop, and asked him if he had forgotten my face. The man could not but confess that he had not, and told me that he was going to Sera. I made him come along with me, and treated him quite hospitably at my quarters in the monastery, besides giving him a farewell present on parting. When I thanked him for all the trouble he had taken for[387] me during our pilgrimage, the man bowed his head as if in repentance, and even shed tears, no doubt of remorse. Before taking his departure he told me that his brothers were living together at their native place, and that they were all doing well.

One day early in October I left my residence in Lhasa and strolled toward the Parkor. Parkor is the name of one of the principal streets in that city, as I have already mentioned, and is the place where criminals are exposed to public disgrace. Pillory in Tibet takes various forms, the criminal being exposed sometimes with only handcuffs, or fetters alone, and at others with both. On that particular occasion I saw as many as twenty criminals undergoing punishment, some of them tied to posts, while others were left fettered at one of the street crossings. They were all well-dressed, and had their necks fixed in a frame of thick wooden boards about 1⅕ inches thick, and three feet square. The frame had in the centre a hole just large enough for the neck and was composed of two wooden boards fastened together by means of ridges, and a lock. From this frame was suspended a piece of paper informing the public of the nature of the crime committed by the exposed person, and of the judgment passed upon him, sentencing him to the pillory for a certain number of days and to exile or flogging afterwards. The flogging generally ranges from three hundred to seven hundred lashes. As so many criminals were pilloried on that particular occasion, I could not read all the sentences, even though my curiosity was stronger than the sense of pity that naturally rose in my bosom when I beheld the miserable spectacle. I confess that I read one or two of them, and found that the criminals were men connected with the Tangye-ling monastery, the Lama superior of which is qualified to succeed to the supreme power of the pontificate in case, for one reason or[375] another, the post of the Dalai Lama should happen to fall vacant. The monastery is therefore one of the most influential institutions in the Tibetan Hierarchy and generally contains a large number of inmates, both priests and laymen.

Shortly before my arrival in Lhasa this high post was occupied by a distinguished priest named Temo Rinpoche. His steward went under the name of Norpu Che-ring, and this man was charged with the heinous crime of having secretly made an attempt on the life of the Dalai Lama by invoking the aid of evil deities. Norpu Che-ring’s conjuration was conducted not according to the Buḍḍhist formula, but according to that of the Bon religion. A piece of paper containing the dangerous incantation was secreted in the soles of the beautiful foot-gear worn by the Dalai Lama, which was then presented to his Holiness. The incantation must have possessed an extraordinary potency, for it was said that the Grand Lama invariably fell ill one way or another whenever he put on these accursed objects. The cause of his illness was at last traced to the foot-gear with its invocation paper by the wise men in attendance on the Grand Lama.

This amazing revelation led to the wholesale arrest of all the persons suspected of being privy to the crime, the venerable Temo Rinpoche among the rest. Some people even regarded the latter as the ring-leader in this plot and denounced him as having conspired against the life of the Grand Lama in order to create for himself a chance of wielding the supreme authority. At any rate Temo Rinpoche occupied the pontifical seat as Regent before the present Grand Lama was installed on his throne. Norpu Che-ring was the Prime-Minister to the Regent, and conducted the affairs of state in a high-handed manner. Things were even worse than this, for it is a fact, admitting of no dispute, that Norpu was oppressive, and mer[376]cilessly put to death a large number of innocent persons. He was therefore a persona ingrata with at least a section of the public, and some of his enemies lost no time in giving a detailed denunciation of the despotic rule of the Regent and his Prime-Minister as soon as the present Grand Lama was safely enthroned. Naturally therefore the former Regent and his Lieutenant were not regarded with favor by the Grand Lama, and such being the case, the terrible revelation about the shoes was at once followed by their arrest, and they were thrown into prison.

All this had occurred before my arrival. When I came to Lhasa Temo Rinpoche had been dead for some time, but Norpu Che-ring was still lingering in a stone dungeon which was guarded with special severity, because of the grave nature of his crime. The dungeon had only one narrow hole in the top, through which food was doled out to the prisoner, or he himself was dragged out whenever he had to undergo his examinations, which were always accompanied with torture. Hope of escape was out of the question, and the only opportunity offered him of seeing the sunshine was by no means a source of relief, for it was invariably associated with the infliction of tortures of a terribly excruciating character. The mere description of it chilled my blood. The torture, as inflicted on Norpu Che-ring, was devised with diabolical ingenuity, for it consisted in driving a sharpened bamboo stick into the sensitive part of the finger directly underneath the nail. After the nail had been sufficiently abused as a means of torture, it was torn off, and the stick was next drilled in between the flesh and the skin. As even criminals possess no more than ten fingers on both hands the inquisitor had to make chary use of this stock of torture, and took only one finger at a time, till the whole number was disposed of. Such was the treatment the ex-Prime-Minister received at his hands.

Norpu Che-ring bore this torture with admirable fortitude; he persisted that the whole plot originated in him alone and was put in execution by his own hands only. His master had nothing to do with it. The inquisitors’ object in subjecting their former superior and colleague to this infernal torture was to extort from him a confession implicating Temo Rinpoche, but they were denied this satisfaction by the unflinching courage of their victim. It is said that this suffering of Norpu Che-ring had so far awakened the sympathy of Temo Rinpoche himself that the latter tried, like the priest of noble heart that he was, to take the whole responsibility of the plot upon his own shoulders, declaring that Norpu was merely a tool who carried out his orders, and that therefore the latter was entirely innocent of the crime. Temo even advised his steward, whenever the two happened to be together at the inquisition, to confess, as he, that is Temo, had done.

The steward, on his part, would reply that his master must have made that baseless confession from the benevolent motive of saving his, the steward’s life, but that he was not so mean and depraved as to seek an unmerited deliverance at the cost of his venerable master’s life. And so he preferred to suffer pain rather than to be released, and baffled all the attempts of the torturers. By the time I reached Lhasa Norpu had already endured this painful existence for two years, and during that long period not one word even in the faintest way implicating his master had passed his lips. From this it may be concluded that Temo had really no hand in the plot. At the same time it must be remembered that Temo was an elder brother of Norpu, and the fraternal affection which the latter entertained towards the other might therefore have been too strong to allow of his implicating Temo, even supposing that the late Regent was really privy to the plot. Be the real circumstances what they might, when[379] I heard all these painful particulars, my sympathy was powerfully aroused for Norpu, whatever hard words others might utter against him; for the mere fact that he submitted so long to such revolting punishments with such persevering fortitude and with such faithful constancy to his master and brother, appealed strongly to my heart.

The pilloried criminals whom I saw on that occasion were all subordinates of Norpu Che-ring. Besides these, sixteen Bon priests had been executed as accomplices, while the number of laymen and priests who had been exiled on the same charge must have been large, though the exact number was unknown to outsiders. The pilloried criminals were apparently minor offenders, for half of them were sentenced to exile and the remaining half to floggings of from three hundred to five hundred lashes. The pillory was to last in each case for three to seven days. Looking at these pitiable creatures I felt as if I were witnessing a sight such as might exist in the Nether World. My heart truly bled for the poor, helpless fellows.

Heavy with this sad reflexion I proceeded further on, and soon arrived at a place to the south of a Buḍḍhist edifice; and there, near the western corner of the building, flooded by sunshine, I beheld another heart-rending sight. It was a beautiful lady in the pillory. Her neck was secured in the regulation frame, just as was that of a rougher criminal, and the ponderous piece of wood was weighing heavily upon her frail shoulders. A piece of red cloth made of Bhūtān silk was upon her head, which hung very low, for the frame around her neck did not allow her to move it freely. Her eyes were closed. Three men, apparently police constables, were near by as guards. A vessel containing baked flour was lying there, and also some small delicacies that must have been sent by relatives or friends. All this food she had to take from the hands of one or other of the three rough attendants, for her own hands were manacled. She was none other than the wife of Norpu Che-ring, whose miserable story I have already told, and was a daughter of the house of Do-ring, one of the oldest and most respected families in the whole of the Tibetan aristocracy.

THE WIFE OF AN EX-MINISTER. PUNISHED IN PUBLIC.

When her husband was arrested, he was at first confined in a cell less terrible than the stone dungeon to which he was afterwards transferred. But this early and apparently more considerate treatment only plunged his family into greater misery. His wife was told that the jailer of the prison in which her husband was incarcerated was not overstrict and that he was open to corruption, and what faithful wife, even though Tibetan, would resist the temptation placed before her under such circumstances, of trying to seek some means of gaining admission to the lonely cell where her dear lord was confined? And so it came to pass that Madame Norpu bribed the jailer, and with his connivance was often at her husband’s side; but somehow her[381] transgression reached the ears of the government, and she also was thrown into prison.

On the very morning of the day on which I came upon this piteous sight of the pillory, she was led out of the prison, as I heard afterwards, not however for liberation, but first to suffer at the gate of the prison a flogging of three hundred lashes, and then to be conducted to a busy thoroughfare to be pilloried for public disgrace.

Poor woman! she seemed to be almost insensible when I saw her, and the mere sight of her emaciated form and death-pale face aroused my strongest sympathy. The sentiment of pity was intensified when I saw a group of idle spectators, among whom I even noticed some aristocratic-looking persons, gazing at the pillory with callous indifference. They were heartless enough to approach her place of torture and read the judgment paper. The sentence, as I heard it read aloud by these fellows, condemned her to so many whippings, then to seven days pillory, and lastly to exile at such-and-such a place, there to remain imprisoned, fettered and manacled. The spectators not only read out the sentence with an air of perfect indifference, but some of them even betrayed their depravity by reviling and jeering at the lady: “Serve her right,” I heard them say; “their hard treatment of others has brought them to this. Serve them right.” These aristocrats were giving sardonic smiles, as if gloating over the misery of the house of Norpu Che-ring.

Really the heartless depravity of these people was beyond description, and I could not help feeling angry with them. These same people, I thought, who seemed to take so much delight in the calamity of the family of Norpu Che-ring, must have vied with each other in courting his favor while he was in power and prosperity. Even if it were beyond the comprehension of these brutes to appreciate the meaning of that merciful principle which bids us “hate the offence[382] but pity the offender,” one would have expected them to be humane enough to show some sympathy towards this woman who was paying so dearly for her excusable indiscretion. But they seemed to be utterly impervious to such sentiments, and so behaved themselves in that shameful manner. I, who knew that political rivalry in Tibet was allowed to run to such an extreme as to involve even innocent women in painful punishment, felt sincerely sorry for the Lady Norpu, and returned to my residence with a heavy heart. My sentiment on that particular occasion is partially embodied in this uta that occurred to me as I retraced my heavy steps:

You, everchanging foolish herds of men,

As fickle as the dew upon the trees,

To blooming flowers your smiling welcome give;

Why should your tears of pity cease to flow

When blooms or withering flowers pass away?

On my return, when I saw my host, the former Minister of Finance, I related to him what I had seen in the street, and asked him to tell me all he knew about the affair. He fully shared my sympathy for the unfortunate woman.

While Norpu Che-ring was in power, my host told me, he was held in high respect. Nobody dared to whisper one word of blame about him and his wife. Now they were fallen, and he felt really sorry for them. It was true, he continued, that some people used to find fault with the private conduct of Norpu Che-ring, and the former Minister could not deny that there was some reason for that. But Temo Rinpoche was a venerable man, pure in life, pious and benevolent, and had met with such a sad end solely in consequence of the wicked intrigues of his followers. My host was perfectly certain that Temo Rinpoche had absolutely no hand in the plot. He said that he could not talk thus to others; he could be confidential to me alone.

Tortures are carried to the extreme of diabolical ingenuity. They are such as one might expect in hell. One[383] method consists in drilling a sharpened bamboo stick into the tender part of the tip of the fingers, as already described. Another consists in placing ‘stone-bonnets’ on the head of the victim. Each ‘bonnet’ weighs about eight pounds, and one after another is heaped on as the torture proceeds. The weight at first forces tears out of the eyes of the victim, but afterward, as the weight is increased, the very eye-balls are forced from their sockets. Then flogging, though far milder in itself, is a painful punishment, as it is done with a heavy rod, cut fresh from a willow tree, the criminal receiving it on the bared small of his back. The part is soon torn open by the lashing, and the blood that oozes out is scattered right and left as the beater continues his brutal task, until the prescribed number, three hundred or five hundred blows as the case may be, are given. Very often, and perhaps with the object of prolonging the torture, the flogging is suspended, and the poor victim receives a cup of water, after which the painful process is resumed. In nine cases out of ten the victims of this corporeal punishment fall ill, and while at Lhasa I more than once prescribed for persons who, as the result of flogging, were bleeding internally. The wounds caused by the flogging are shocking to see, as I know from my personal observations.

A prison-house is in any case an awful place, but more especially so in Tibet, for even the best of them has nothing but mud walls and a planked floor, and is very dark in the interior, even in broad day. This absence of sunlight is itself a serious punishment in such a cold country.

As for food, prisoners are fed only once a day with a couple of handfuls of baked flour. This is hardly sufficient to keep body and soul together, so that a prisoner is generally obliged to ask his friends to send him some food. Nothing, however, sent in from outside reaches the[384] prisoners entire, for the gaolers subtract for their own mouths more than half of it, and only a small portion of the whole quantity gets into the prisoners’ hands.

The most lenient form of punishment is a fine; then comes flogging, to be followed, at a great distance, by the extraction of the eye-balls; then the amputation of the hands. The amputation is not done all at once, but only after the hands have been firmly tied for about twelve hours, till they become completely paralysed. The criminals who are about to suffer amputation are generally suspended by the wrists from some elevated object with stout cord, and naughty street urchins are allowed to pull the cord up and down at their pleasure. After this treatment the hands are chopped off at the wrists in public. This punishment is generally inflicted on thieves and robbers after their fifth or sixth offence. Lhasa abounds in handless beggars and in beggars minus their eye-balls; and perhaps the proportion of eyeless beggars is larger than that of the handless ones.

Then there are other forms of mutilation also inflicted as punishment, and of these ear-cutting and nose-slitting are the most painful. Both parties in a case of adultery are visited with this physical deformation. These forms of punishment are inflicted by the authorities upon the accusation of the aggrieved party, the right of lodging the complaint being limited, however, to the husband; in fact he himself may with impunity cut off the ears or slit the noses of the criminal parties, when taken in flagrante delicto. He has simply to report the matter afterwards to the authorities.

With regard to exile there are two different kinds, one leaving a criminal to live at large in the exiled place, and the other, which is heavier, confining him in a local prison.

Capital punishment is carried out solely by immersion in water. There are two modes of this execution: one by[385] putting a criminal into a bag made of hides and throwing the bag with its live contents into the water; and the other by tying the criminal’s hands and feet and throwing him into a river with a heavy stone tied to his body. The executioners lift him out after about ten minutes, and if he is judged to be still alive, down they plunge him again, and this lifting up and down is repeated till the criminal expires. The lifeless body is then cut to pieces, the head alone being kept, and all the rest of the severed members are thrown into the river. The head is deposited in a head vase, either at once, or after it has been exposed in public for three or seven days, and the vase is carried to a building established for this sole purpose, which bears a horrible name signifying “Perpetual Damnation.” This practice comes from a superstition of the people that those whose heads are kept in that edifice will forever be precluded from being reborn in this world.

All these punishments struck me as entirely out of place for a country in which Buḍḍhist doctrines are held in such high respect. Especially did I think the idea of eternal damnation irreconcilable with the principles of mercy and justice, for I should say that execution ought to absolve criminals of their offences. Several other barbarous forms of punishment are in vogue, but these I may omit here, for what I have stated in the preceding paragraphs is enough to convey some idea of criminal procedure as it exists in the Forbidden Land.

I stayed in Lhasa till about the middle of October 1901, when I decided to return to Sera. My host kindly placed at my disposal one of his horses and on this I jogged towards my destination. The snow had been falling since the previous evening, and already the road was covered with a thick layer of its crystal carpet. It was the first snow of the season. On the road from Lhasa to Sera,[386] by Shom-khe-Lamkha (priest’s road), there is a river about half a mile on this side of Sera. This river dries up in winter, and on the day I am speaking of its bed was covered with snow. There I noticed a party of five or six young priestlings of Sera, absorbed in the innocent sport of snowballing. This highly amused me, calling forth in my mind’s eye the sights I had frequently come across at home, and reminding me that human nature is, after all, very much alike the world over. And so these little fellows were pelting each other with soft missiles, running and pursuing, shouting and laughing, forgetting for once the stern reprimanding voices of their exacting masters, and I amused myself with composing an uta, as follows.

On yonder fields of snow the children play,

And fight with snow-balls in great glee.

They throw and scatter these amongst themselves,

And in these heated contests melts the snow.

While I was watching the snow-fight, a burly fellow coming from the direction of Lhasa overtook me and began to stare at me. I at once recognised in him one of my old acquaintances, the youngest of the three brothers whom I accompanied on the pilgrimage round Lake Mānasarovara, who gave my face a sharp parting smack, as already told. He seemed to be quite astonished, even frightened, when he saw me, his whilom companion of humble attire, now transformed into an aristocratic-looking personage, such as I must have appeared to him. At any rate he avoided my eyes, and was about to walk off with hurried steps, when I bade him stop, and asked him if he had forgotten my face. The man could not but confess that he had not, and told me that he was going to Sera. I made him come along with me, and treated him quite hospitably at my quarters in the monastery, besides giving him a farewell present on parting. When I thanked him for all the trouble he had taken for[387] me during our pilgrimage, the man bowed his head as if in repentance, and even shed tears, no doubt of remorse. Before taking his departure he told me that his brothers were living together at their native place, and that they were all doing well.