A dissertation presented by Eyal Aviv

to The Committee on the Study of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of The Study of Religion Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

July, 2008

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Chapter Three: Ouyang’s evaluation and Critique of Chinese Buddhism

3.1 Introduction

3.1.1 Ouyang’s project

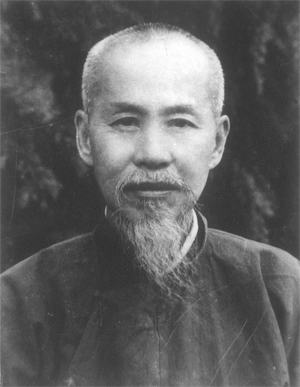

As is evident from Ouyang’s biography, once he decided to dedicate his full attention to Buddhism he began a thorough assessment of its doctrines. Being dissatisfied with the Buddhist thought and practice prevalent in his day, he sought answers in the only place a person with his intellectual background could turn, namely in Buddhist texts themselves.

However, Ouyang chose to study not the texts most frequently studied by his contemporaries and predecessors, but the Yogacara corpus, following the advice of his teacher Yang Wenhui. Now, with the texts that were sent by Nanjio Bunyiu from Japan (see chapter two, pages 37) Ouyang was equipped with commentaries that could elucidate abstract points impenetrable to Chinese Yogacarins since the Tang dynasty. Studying these texts substantiated many of his early doubts regarding the Chinese Buddhist tradition. He became confident that answers could be found in the Yogacara treatises that contained the “authentic” Buddhist teachings of Buddhism and in the idea that it was necessary to distinguish genuine Buddhism from later developments.

Ouyang was in many ways the right person for the task of reassessing Buddhism. He was a new kind of Buddhist intellectual, a lay Buddhist who did not accept monastic authority. Thus he was free of the institutional Sangha’s conventions, both in his teaching and practice. Ouyang, of course, was not the only one who held this new vision of Buddhism but he was a dominant voice in the larger movement, in both China and Japan within which a more critical approach was taken to the Chinese Buddhist tradition. As we saw in my introduction above, while these features were shared by many Buddhists in the late nineteenth early twentieth centuries, Ouyang also represented one unique case in this tapestry of “multiple Buddhist modenrinities” that of the scholastic Buddhists, whose emphasis on a systematic approach to the study of Buddhism had a far reaching influence on East Asian Buddhism and on East Asian intellectual history in general.

3.1.2 The problems of Chinese Buddhism

What exactly were the aspects of Chinese Buddhism that Ouyang found unsatisfactory? In a famous lecture he gave in 1922 on the Cheng weishi lun entitled Expositions and Discussions of Vijnaptyimatra (Chinese), Ouyang outlined ten themes that he identified as most crucial to the text. In each one of the ten expositions or doctrinal schemes1he chose to focus on one of the components of the scheme.2 Before delving into each expositions (a few of which will be discussed in this and later chapters), Ouyang began by saying, “I will first explain the obstacles (Chinese) confronting modern Buddhism. What is [the reason] for these obstacles? Briefly, they have, five causes.”3 The five are:

1. The negative impact of Chan;

2. The vagueness of Chinese thought;

3. The negative impact of Huayan and Tiantai;

4. “Secular” (i.e. Non-Buddhists) scholars’ incorrect judgments of the Buddhist scriptures;

5. The lack of skill among scholars who attempt to study Buddhism;4

In essence, we can divide the five points above into three major areas of critique. (1) is the problematic nature of Chinese thought which is “vague and unsystematic” (Chinese) and “lacks careful investigation” (Chinese); the next (2) is mainstream Buddhism, especially Chan, Tiantai and Huayan (3) is the challenge and risk in the secular study of Buddhism. Beyond the dismissive remark he made about Chinese thought, Ouyang felt that two powers threatened Buddhism in China: internally, the practice and thought of mainstream Chinese Buddhism; and externally, the fact that scholars began to look at Buddhism for the wrong reasons. Ouyang did not specify who he was referring to, but one example of such an intellectual was Hu Shi, who became interested in Buddhism in that period for historical, methodological and political reasons rather than for soteriological ones.5 In other words, intellectuals like Hu Shi ignored the normative value and soteriological potential of Buddhism in favor of “narrower” intellectual concerns.

I will leave aside the criticism of “secular” scholars for the time being as it is less relevant for our concern in this dissertation. Instead, I would like to focus on the second dimension, namely Ouyang’s evaluation of mainstream Chinese Buddhism and his critique of the Chinese schools of Buddhism.

In terms of the scope of his critique, unlike other scholastic Buddhists in twentieth century China, such as Taixu, Yinshun or Lü Cheng, Ouyang never published a systematic historical criticism or an evaluation of Chinese Buddhism. Committed to the continuation of Yang Wenhui’s mission to publish critical editions of Buddhist texts, Ouyang was busy studying the texts he published. His evaluation of the tradition thus appeared then less systematically in many of his lectures, writings and letters. However, it is still crucial for us to discuss his writings about Chinese Buddhist schools since, as we will see below, his critiques, unsystematic as they may be, would guide us to where he considered the main problem of the Chinese Buddhist tradition really was.

3.2 Critique of Chan

3.2.1 The anti-Chan sentiments of late Qing and early ROC

The Chan tradition was one of the most obvious targets for Buddhist reformers and critics in the early part of the twentieth century. Chan had been the single most influential form of Buddhism among members of the Chinese elite since the eighth century, and continued to symbolize for many the essence of Chinese Buddhism. Although in later imperial China sectarian boundaries were not as strong as in the early days of the Chan School, 6 still many of the most eminent monks affiliated themselves with the Chan tradition.7 In the twentieth century we can find among them eminent figures such as Jichan, Xuyun and Laiguo. Many others who did not affiliate themselves with the Chan School still saw it as the crown of Chinese Buddhism or at least as one of its important pillars. One well-known example was the monk Taixu, who wished to revive all Chinese Buddhist schools and saw them all as essential, but still acknowledged that Chan was the most prominent among them.8

In its earlier stages, Chan was a revolutionary school in almost every possible dimension. It had an idiosyncratic rhetoric, a strong self-identity and new methods of religious practice. Chan is famous for its antinomian approach to scriptural authority and for doubting the effectiveness of words and language to express the non-dual nature of reality. At the same time, the Chan School developed one of the most elaborate corpora of literature, including unique genres, with which it communicated its message.

By the end of the Qing, however, the innovative character was long gone and the tradition was considered by many to be ossified. Both internal and external criticism of Chan was prevalent in the late Qing. One notable example is in the (auto)biography of Xuyun,9 considered by many to be the most eminent Chan figure the twentieth century. Xuyun lamented, “In the Tang and the Song Dynasties, the Chan sect spread to every part of the country and how it prospered at the time! At present, it has reached the bottom of its decadence and only those monasteries like Jinshan, Gaomin and Baoguan, can still manage to present some appearance.”10 Chan was thus “only a name but without spirit”.

For Ouyang and other intellectuals around him Chan’s decadence was inherent within its problematic practices and approach to scriptures. As we saw in the biography chapter (see chapter two, page 30-32) the evidential scholarship tradition, which became widespread in the Qing, preferred a meticulous scholastic approach over metaphysical speculation. Yang Wenhui, Ouyang’s teacher, despite admiring Chan’s achievements, was very critical of this anti-intellectual and antinomian approach to the Buddhist scripture. He said,

If one is attached to the kind of method [embodied] in the concept of ‘not relying on words and letters,’ as a fixed teaching, then he is misleading himself and others. One must know that [although] Mah!k!#yapa became the first patriarch (i.e. of the Chan School) and received the transmission, after the Buddha’s death, he saw the collection of the teaching as an urgent matter. In addition, he transmitted the Chan teaching to no other but $nanda, the preserver of the Buddha’s knowledge and words. Later, generation after generation, everybody wrote commentaries, explained the scriptures and propagated the gist of the teaching. After Bodhidharma came from the West, the receiver of the transmission was Huike, who was familiar with the scriptures but failed to understand their meaning. If Huike did not understand the meaning of the teaching, how could he understand the depth of Bodhidharma’s [mind]? When we get to the Sixth Patriarch [during the Tang dynasty], at first he appeared illiterate, in order to displaying the profundity of the unsurpassable path. [He taught that] the key [to the unsurpassable path] is to separate oneself from words and letters and gain realization by oneself. [However] later generations did not understand this idea and often understood the Sixth Patriarch to be illiterate. What an error!11

In addition to antinomianism the Chan School was also blamed for overemphasizing the quiescence of the mind. Similar criticism was leveled by Qing scholars against the Ming Confucians for appropriating Chan-like quietism. This was thought to in turn have led to detachment from real life, and as a result to the collapse of the dynasty. The connection between the Neo-Confucian Mind School and Chan Buddhism is almost self-evident. Zhang Taiyan, a Yogacara enthusiastic and a one of the last representatives of the Hanxue tradition (i.e. who used evidential research methods) remarked, “[The Chan School] treasures its own mind, it does not yield to spirit of the intellect (Chinese) and is similar to the Chinese [Confucian] Mind School”12 Given the Hanxue scholars’ traditional low esteem of the Mind School of Confucianism, equating them with Chan was by no means a compliment.

3.2.2 Ouyang’s critique

What were the criticisms against the Chan School that led Ouyang to include it as one of the obstacles for Buddhism? Here is what Ouyang has to say about Chan:

Since the School of Chan entered China, its blind adherents [mistakenly] understood the Buddhadharma to mean ‘Point directly to the fundamental mind, do not rely on words and letters, see your nature and become a Buddha.’ Why should one attach oneself to name and words? Little do they realize that the high attainment of the Chan followers only happens when reasoning is matched with those who have sharp faculties and high wisdom. Their seeds were perfumed with prajna words from immemorial aeons. Even after they attained the path, they still do not dispose with the words of all the Buddhas; these [words] are written in the scriptures and they are not subject to a single conjuncture. But blind people do not know it; they pick up one or two Chan cases (i.e. gongans) as a Chan of words, meditating on them like a ‘wild fox’ and repeatedly say that the Buddha nature is not in language. Therefore, they discard the previous scriptures of the sages of yore and the excellent and refined words of the worthy ones of old, which lead to the decline in the true meaning of the Buddhadharma.13

From the above quote it is evident that Ouyang’s main accusation against Chan is similar to that of his teacher, Yang Wenhui, i.e. that it disregards scriptural teaching and relies too much on one’s own mind. Ouyang complains that Chan adherents merely repeat over and over the cliché that Chan’s truth is outside the scriptures and beyond words. They forgot that actually “their seeds were perfumed with prajna words from immemorial aeons,” and that it is only because of that that they are now at a level of attainment.

Ouyang used the well-known Chan fox gongan to illustrate his point. This gongan tells the story of a monk who gave the wrong Chan answer to a question posed by a student of his in the times of the Buddha Kasyapa. The question was whether the laws of causality could still affect a great cultivator of the path. The monk replied wrongly that such a man is not subject to the laws of causality and as a punishment was turned into a fox for five hundreds aeons. The fox-monk later posed the same question to Baizhang, who answered that such a cultivator could not be ignorant about the law of karma. When the fox heard Baizhang’s answer he immediately attained enlightenment and his punishment was lifted.14

Ouyang brilliantly used the Chan gongan as a rhetorical device against Chan adherents themselves, accusing them of being, like the wild fox, attached to literalism without actually understanding the true meaning of the teaching. For Ouyang, even after one reaches a certain level of attainment, it does not mean that one can discard the Buddha’s teaching. One cannot make further progress on the path without the map that the Buddhas and other “worthy ones of old” had drawn for us. Abandonment of the Buddhist scriptures will ultimately lead to an erroneous path and “to the decline in the true meaning of the Buddhadharma”. We will see below how he further developed this idea in his two-fold paradigm theory, which was partially a solution for the anti-canonical tendencies within Chan.

In his preface to the Yogacarabhumi, published in 1919, Ouyang indicated that one of the problems of Mahayana followers is attachment to the notion of emptiness , and that the word “only” in the compound consciousness-only indicates the correction of this attachment that might lead to nihilism.15 Ouyang did not mention Chan explicitly, but he did allude to Chan’s tendency to negate everything. This tendency to reject the Buddha’s authority and his teaching is undermines the metaphysical foundations of the Buddhist practice. We will see below that for Ouyang it is impossible to practice the genuine teaching if one is not familiar with the path.

Interestingly, for Ouyang, as for his teacher Yang Wenhui, the adherents of the Chan tradition, despite their erroneous approach to texts, did not follow nonauthentic Buddhism as their fellows from the Huayan and Tiantai schools did (see section 3.3 below). In September 1924, Ouyang gave another lecture titled “Discussing the Research of Inner Studies,” in which he explained the importance of the research conducted in his institution. Here he argued that “Although the Chan School mingles indigenous Chinese elements in its thought, its principle coincides with that of the School of Emptiness (i.e. Madhyamaka), and it still originated from the West (i.e. India).16 In addition, in the quote above we can see that despite his critique, Ouyang still considered Chan practitioners to be at the stage of the Path of Vision (Skt. darsanamarga Ch., Chinese, i.e. very advanced on the path, having already achieved the lower stages of sainthood). Ouyang, therefore, connected the Chan tradition to the School of Emptiness and did not make a clear connection between Chan and tathagatagarbha Buddhism, of which he was very critical. As in the case of the Madhyamaka, he saw Chan’s flaws as relatively minor compared with the flaws of the other Chinese schools he criticized. In that sense, Ouyang did not go as far as some Japanese scholars from the “Critical Buddhism” (Hihan Bukkyo) movement, who argue that “Zen is not Buddhism.”17

3.3 Critique of Huayan and Tiantai

Ouyang’s critique of Huayan and Tiantai was much sharper but again suffered from lack of clarity. He did not systematically treat the Huayan or Tiantai positions. Instead, his comments are scattered throughout his lectures and letters, and they are very different in nature from the treatment he gave to the texts he chose to publish, both in scope and in depth. There is no serious evaluation of the “flaws” he found in the two traditions. In addition, Ouyang often lumped Huayan and Tiantai together as if they represent one tradition, without differentiating between them, or being sensitive to how their thought and practices developed over time. However, from the little that he did write, I will argue, that we can detect indicators that point to where he thought the problem in fact lies.

3.3.1 Tiantai and Huayan founders lack true attainments

In his Expositions and Discussions of Vijnaptyimatra, Ouyang has this to say about the two schools:

Since Tiantai and Huayan began to prosper, the light of Buddhism has weakened. Among the founders of those traditions none have attained the level of sainthood (Zhiyi himself admitted that he attained [only] the five ranks),18 the views that they held were inferior to those of the Indian masters. But their followers believed that their master is a Buddha born again in the world, they confined themselves within [limited] boundaries, and satisfied themselves with attaining only a little; indeed there are good reasons why the Buddhadharma is not understood.19

As the above passage indicates, Ouyang blamed the teachers of both schools for no less than dimming the light of Buddhism, failing to achieve the level of sainthood, satisfying themselves in achieving little and being inferior to the Indian Buddhists saints.20 But what was exactly was his argument against the Tiantai and Huayan traditions? In what way were they “dimming the light of Buddhism”?

3.3.2 Tiantai and Huayan’s panjiao as creating a division in the one teaching

One specific problem that Ouyang raised is the two schools’ doxographical practice, i.e. their panjiao differentiation of teachings:

The cause and condition of this great matter (i.e. the Buddha’s appearance in the world) is also the Buddha’s only teaching (Chinese). Although the Buddha turned the wheel three times,21 and divided the teaching into three vehicles, yet there is in fact only one single teaching. [The teaching] is to lead all sentient beings into nirvana without remainder and liberate them. Ignorant people talk about sudden, gradual, incomplete and complete [teachings]. For example, in Tiantai there is a division into four teachings, and in Huayan, there is also a claim for a five teachings theory. The Tiantai School’s basis for their division in the Sutra of Immeasurable Meanings (Chinese) and the Huayan School seeks the basis for its foundation in the Sutra of the Bodhisattva Necklace-like Deeds (Chinese). Both schools differentiate [between the teachings] based on [different] concepts, [But, in fact] there is no difference between the teachings [themselves]. Therefore it is acceptable to differentiate between four or five teachings in terms of concepts and words but it is impossible to do so with the teaching 22.23

In other words, one of the main problems of the Tiantai and Huayan thinkers is that they created divisions within the teaching of the Buddha, a teaching that is fundamentally one. The only goal of the Buddha’s teaching is to deliver sentient beings and to help them attain nirvana. The rest is all conceptual differentiations for the same purpose of delivering sentient beings.

3.3.3 The flaws of Tiantai and Huayan cultivation methods

In 1924, Ouyang published an essay on meditation practice entitled The General Meaning of Mind Studies (Chinese) in which he outlined his critique of the two schools’ meditation practices. The essay as a whole is a lengthy treatment of the Buddhist theory of meditation, and his critique of the Chinese schools’ meditation practices appears briefly before he presents the classical meditation theory in depth.

First, he describes the types of meditation practice according to Tiantai’s three main manuals of meditation, all written by Zhiyi: (1) The Six Mysterious Gates (Chinese) (2) The Dharma Gate of Explaining the Sequence of the Perfection of Dhyana (Chinese) and (3) the Mohe zhiguan (Chinese). Ouyang explained briefly the methods discussed in each one of the treatises, especially that of the mohe zhiguan, on which he remarked:

The Mohe zhiguan is this school’s most important treatise; the heart of this treatise is based on the verse from the fundamental text of the Prajna School, the Mulamadhyamaka-karika of Nagarjuna, [which explains the] correct meaning of dependent co-arising. The verse says, ‘[Dharmas] which are arise based on causes and conditions, I say that they are empty; they are also called provisional designations and they are also what I mean by the middle path’.24 Based on this [the Mohe zhiguan] established the three "amathas and the three vipasyanas. At first, both "amathas and vipasyanas operate, then the three penetrate into each other just like [the three truths teaching i.e.] emptiness, the provisional and the mean. These three become one in one moment and the meaning of complete penetration (Chinese) is thus established. Especially when examining this [theory] based on the Yogacara’s school notion of the perfected and real,25 then [we see that] the perfect [penetration] is [indeed] perfect, but it is not real (Chinese). These three "amathas and three vipasyanas [i.e. the practice of the Mohe zhiguan], only possesses the general characteristics (Chinese),26 but if we analyze seeking what is real then [we will realize that] they do not exist. [This theory] should be further discussed.27

It seems that Ouyang’s main concern here is that Zhiyi’s meditation theory is perfect as an expedient means i.e. it is a useful category but it is not real (dravya).

As a perfect method it is useful up until a certain point, but it will not lead us to see reality as it is, nor will it help us to attain the higher fruits of the path.

The problem of the Huayan School is similar to that of the Tiantai:

This School follows the Huayan sutra, which is no different from following the Yogacarabhumi sastra.28 To this extent this school should talk about the immeasurable samadhis, but instead they practice the [method of] “contemplation of the dharmadhatu,” which again is also merely [concerned with] the general characteristics. Their doctrine discusses the notion that the one contains the whole and that the one is the whole in order to expound the doctrines of the four non-obstructed understandings,29 four methods for attracting people30 and the four kinds of complete identity” To that extent this doctrine is indeed subtle and thorough, but at the same time there is no clarity in regard to each one of the immeasurable samadhis. Therefore, the followers of this [tradition] confined themselves within the abstract teachings that are wayward and baseless. In the end, they do not find the gateway to the teaching of meditation (Chinese).31

Thus, in Ouyang’s mind both schools share the same problem. Their categories are only provisional and cannot lead to higher attainments. Both schools do not offer a meditation practice with a clear path and correct categories on which one should meditate, but they differ in the acuteness of the problem. While in the Tiantai case it leads to limited attainments in the Huayan it leads to a theory which is “wayward and without basis” and to a failior to find “the gateway to the teaching of meditation.”

3.3.4 Summary of the critique

As already stated, it is difficult to obtain a systematic picture from Ouyang’s writings of what exactly were in his opinion the doctrinal and practice-related problems of the two traditions. It seems that in regard to the complexity of these two traditions, Ouyang himself committed the same errors with which he charged his opponents, that is, providing an explanation with only “general characteristics.” We get the impression that his critique is too general and unfounded. But even from these few examples we can extract the gist of his contention:

(1) The Huayan and Tiantai doctrinal classifications create unnecessary divisions within the Buddhist teaching, which is essentially unified.

(2) Their meditation method is flawed and relies on general and unspecified categories, which are good skilful means at best, but will not lead us to see things as they really are.

(3) Taking into account the flawed understanding of the unity of teaching together with the school’s practice, there is little wonder that followers of those schools and even their patriarchs attained merely lower levels of attainments.

During the late Ming dynasty there was an attempt to revive the Yogacara studies in China. One would think that Ouyang would welcome a turn toward the teaching of the Yogacara School, but instead of welcoming the development, Ouyang was again very critical. Why was he so critical toward an earnest attempt to study the same tradition he propagated almost four hundreds years later? As we will see below his critique was concerned with the motives of the Ming Yogacarans and the inherited flaws outlined above, which tainted the Ming attempt to revive the old teaching.

3.4 Critique of the Ming dynasty’s Yogacara studies

During the late Tang, the three traditions mentioned above, namely Chan, Tiantai and Huayan, established themselves as the acme of Buddhism, while other forms of Buddhism, including the hallmarks of Indian Mahayana i.e. Madhyamaka and Yogacara, were marginalized. These two were thought of as merely partial or nascent Mahayana teachings. Almost a millennium later, during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), however, serious attempts were made by the most eminent monks of the period to revive Chinese Yogacara. What was the nature of these attempts, why did they fail and what was the reason Ouyang was critical of them? These are the questions that will be discussed briefly in this section.

Given the importance of Yogacara to Ouyang’s overall project, it is not surprising that he treated the history of Yogacara in his writings. One place to learn about how Ouyang viewed the development of the school in China is his preface to the Yogacarabhumi. In this text, Ouyang carefully scrutinized the different approaches to Yogacara throughout Chinese history, stratified the historical layers of Yogacara history in Indian and China, and criticized the mistakes of the past.

Regarding the pre-Xuanzang (i.e. old) translations, Ouyang’s major complaint is that they are “not smooth” and “not good,” and that the low quality of the translation made the “sweet dew [of the Buddha’s teaching] undrinkable.”32 The situation changed dramatically with Xuanzang and his school, which improved the quality, quantity and the precision of the translation of Yogacara texts. But this phase was short lived. After the end of the Tang the authentic Yogacara teaching ceased to exist in China. In the late Tang, Ouyang tells us, “Master Yongming Yanshou systematically presented the Faxiang teaching when he wrote the Record of the Mirror of [The Chan] School (Zongjinglu, Chinese). Despite the fact that he did not establish the teaching,33 he was still able to explain it.”34 But this short transition period was followed by the decline of the teaching in China, and Ouyang tells us that at the end of the Yuan dynasty many Yogacara texts were lost and study of Yogacara ceased until the late Ming.

The attempt to revive Yogacara during the Ming is of greater interest to us since it was the Ming revivalists who set the path of Yogacara studies for later generations, a path that was still the only available approach in the republican era in which Ouyang lived. Yet, contrary to what one would expect Ouyang was critical of his Ming predecessors. Shengyan’s article about Yogacara in the Ming may provide us with an explanation. He says, “Late Ming Yogacara, despite the fact that it originated from the treatises translated by Xuanzang, had different features from the [Yogacara] of Kuiji’s period. The old texts were lost, and there was no way to study them. [In addition,] the demands of Buddhism at that time were different from those of Kuiji’s era. Kuiji established Yogacara as the sole philosophical system, which explains the entirety of the Buddhist teaching, while the late Ming Buddhists used Yogacara to tie the entirety of the Buddhist teaching to what was not sufficient and needed correction in the Buddhism of their own days.”35 If anyone during the late Ming bothered to study Yogacara at all, it was through the lenses of the Ming revivalists, and it was those lenses that Ouyang wished to replace. In order to better contextualize his critique, a brief description of Yogacara studies of the Ming is needed.

3.4.1 The Yogacara Studies revival in the Ming

As we previously saw, during the Tang dynasty the Yogacara teaching faded into the background, and very few Buddhist scholars were interested in pursuing a path that had lost its doctrinal primacy and imperial patronage. A revival of interest in Yogacara occurred only toward the end of the Ming dynasty, when, according to Shengyan, seventeen prominent monk-scholars turned their attention again to Yogacara. Among those monks we can find the most prominent names of the day, Zibo Zhenke (Chinese, 1543-1603), Ouyi Zhixu (1599-1655) and Hanshan Deqing (Chinese, 1546-1623).36

Shengyan argues that, while a minority of those monks (only two) were genuinely interested in Yogacara qua Yogacara, the rest were Huayan or Tiantai scholars, 37 or in the majority of cases Chan monks. These monks used Yogacara to support and give a doctrinal foundation to their sectarian systems or, in the case of Chan, to the school’s soteriological path. The Chan followers became aware of the fact that the Chan of their generation was in decline compared to that of the golden age of the Tang and the Song. The Ming dynasty Chan masters felt that they could only imitate the past masters’ gestures but were lacking in true understanding regarding the foundational teaching of their own tradition. They felt that the rigorousness of the Yogacara tradition might be a gateway for a better understanding of the Buddhist tradition.

Another problem for the Ming Yogacarans was that they understood Yogacara through the lenses of texts such as the *Suramgama sutra, The Sutra of Complete Awakening and the Awakening of Faith in Mahayana. It was this interpretation of his predecessors and contemporaries that, I argue, was the driving force behind Ouyang’s critique of Chinese Buddhism, especially what he saw as the erroneous views expressed in the Awakening of Faith. The full breadth of this critique will be treated in our next chapter.

But why Yogacara and not other forms of Buddhism? In his article on Buddhist logic in Ming China, Wu Jiang provides one possible explanation. According to Wu, Ming Buddhists used Buddhist logic as a tool in their anti- Christian polemics. The rise of Buddhist logic is closely linked to the Yogacara school in China, as both were branches of Buddhist knowledge translated and propagated by Xuanzang and Kuiji. When Christian missionaries began frequenting China in the sixteenth century, their usage of logic to prove the existence of a creator-god triggered the need to find an adequate response to repudiate Christian claims.38

3.4.2 Ouyang’s critique of the Ming Yogacara revival

What were Ouyang’s contentions against the Ming revivalists?

[The] Ming revivalists tried to [re]build the wall of the [Faxiang’s] teaching. They worked hard but had no achievements (Chinese). Then, for over the course of several centuries, those who wish to have a command of this teaching did not carefully study any other [Yogacara] text than the Eight Essentials Text of the Faxiang School39 and The Core Teaching of Weishi.40 Their discourse was a disunified shambles, and [they achieved only] a narrow sectarian view,41 whereas [the scope of Faxiang] is as broad as heaven and earth and they did not know it; it has the excellence of being well structured but they did not make good use of it. They only cast their eyes over the surface, and then left it at that, who [among them] bothered with [the challenges of] the Yogacarabhumi?42

In a way, it was not the revivalists’ fault. Despite their genuine interest, how could they have revived the teaching after so many texts were lost? How could they understand the different voices of the tradition and be sensitive enough to the differences between Yogacara and later Chinese Buddhism? But as the text quoted above stated, they did not even try. There was no “careful study” that attempted to understand Yogacara on its own terms, only interpretations based on sectarian views, whether Chan, Tiantai or Huayan.

According to Ouyang, this sectarian approach to Yogacara can be traced back to the Tang. It was in the Tang that monks such as Fazang (Chinese, 643-712), Chengguan (Chinese, 738-83)43 and Yongming Yanshou (Chinese, 904-975) began to approach Yogacara not as an end but as a means to establish their own teaching.

Beyond the general attitude and the wrong motives involved, one specific problem with the Ming revivalists was their disregard of the most important text in the Yogacara corpus, the Yogacarabhumi. Both Yang Wenhui and Ouyang attached great importance to the Yogacarabhumi. We already saw that completing the printing of the whole Yogacarabhumi was a part of Yang’s will before he died. How could a serious study of Yogacara be conducted without a serious study of its root text?

According to Ouyang, the big change happened only when Yang Wenhui retrieved the commentaries on the Yogacarabhumi from Japan. Then interested Buddhists reacquainted themselves with the genuine Yogacara teaching, and critical methods for reading the text were applied for its study. Consequently, the flaws of mainstream Chinese Buddhism could be exposed and treated.

Another criticism against the Ming revivalists appeared in Ouyang’s Expositions and Discussions of Vijnaptyimatra. As noted above this was a lecture that Ouyang gave five years after he published his preface to the Yogacarabhumi.44 The problems of the Ming Yogacarans are discussed in the third section of this text, when Ouyang investigates the theory of two wisdoms, of which he focused on “acquired knowledge.”

Discussing the two wisdoms or knowledges i.e. “fundamental knowledge” (Skt. mulajnana Ch., Chinese) and “acquired knowledge” (Skt. prsthalabdhajñana Ch., Chinese),45 Ouyang wished to counter the over-emphasis of Chinese Buddhist tradition on fundamental knowledge. This focus on fundamental knowledge was the result of the widespread acceptance of tathagatagarbha thought in China and the doctrines associated with the Awakening of Faith. For Ouyang this emphasis on fundamental knowledge meant lack of sufficient attention to the importance of acquired knowledge. Acquired knowledge is a unique and important feature of Mahayana, because whereas fundamental knowledge is ineffable and cannot give rise to words for the benefit of others (Chinese), acquired knowledge does just that. It is the means by which the truth of Buddhism can be communicated, and therefore it has a subtle function (Chinese) that fundamental knowledge lacks.

Since the Ming revivalists followed the tendency of Chinese Buddhists to emphasize fundamental knowledge, they failed to appreciate the “purpose of the excellent function of acquired knowledge.” This is again another dimension of the former contention. The Ming revivalists did not study critically the Yogacara corpus, but mirrored former understandings of Buddhism in their reading of Yogacara texts.

3.5 The Problem of “the branches and the root”

If Ouyang’s teaching is to be understood as a response to the flaws he outlined in his Expositions and Discussions of Vijnaptyimatra, why did he never fully develop those critiques? One of the main reasons was that he saw the critique of the tradition not as an end, but only as a means to continue Yang Wenhui’s mission to revive Buddhism and make it relevant for the modern age. The practical reason that Ouyang did not elaborate on his critique of the Chinese school was the mission he inherited, i.e. to publish texts in the canon that were no longer available in China and to correct texts with major editorial problems. Consequently, combining his commitment to publish texts and to scholarship, Ouyang included most of his views and assessments of Buddhism in his prefaces to the scriptural text that he published. Since he published mostly early Indian scriptures, which he deemed important, he naturally treated them in depth at the expense of later Chinese Buddhist innovations, which were more widely available and were considered by him flawed. The problems with the Chinese Buddhist schools came up mostly in the context of his treatment of old Indian teachings and texts.

The other, more significant reason that Ouyang did not elaborate on his problems with the East Asian schools was that Ouyang identified a root problem that is responsible for many later problems in the teaching of Chinese schools, especially those of Tiantai and Huayan schools. Using a metaphor often employed in Chinese philosophy, for Ouyang Chinese schools were like branches that were nourished by a problematic root. Historically, both Tiantai and Huayan Schools in late Imperial China followed the tathagatagarbha teaching, especially as outlined in the Awakening of Faith in Mahayana.46 And indeed, while he devoted much less attention to the “branches,” he elaborated much more on the “root” of the problem i.e. the problematic nature of the Awakening of Faith doctrine.

3.6 Conclusions

This chapter focused on the problems Ouyang identified within Chinese Buddhism. As we saw in the second chapter, the Buddhist tradition was a key to addressing Ouyang’s existential concerns and his path of salvation. However, it was not an easy path. One needed to be careful when seeking the “right understanding” of Buddhist teaching, and to be systematic in the study of what Buddhism “really” means. The way to understand the path was through a critical study of the Buddhist texts, which was what the Chinese tradition has failed to do.

According to Ouyang, Chinese have a disadvantage when approaching Buddhism, since they are exposed to Buddhism through translations, a large part of which are of poor quality. Luckily, Chinese also have reliable translations of texts that expose the path as reflected in the Indian heyday of Buddhism, such as the texts in Xuanzang’s corpus. Through study of those texts, with the later commentaries of reliable commentators, they can gain access to “real” Buddhism.

The problem of Chinese Buddhism was that it did not take the path described above. According to Ouyang, shortly after Xuanzang translated the texts, his teaching was forgotten, the Yogacara School declined, and many commentaries disappeared. Two dangerous developments followed: (1) the total rejection of scriptures in the Chan tradition in a way that led to a “decline in the true meaning of the Buddhadharma.”; (2) the wrong understanding and misguided interpretation of the teaching, as happened in the case of the philosophical schools of East Asian Buddhism, namely the Tiantai and Huayan Schools.

We have also seen that the above two paths in Chinese Buddhism were so ingrained in the way Chinese understood Buddhism that even in the Ming, when Buddhists felt that their traditions reached stagnation and attempted to revive it with the teaching of the Yogacara, it was too little, too late. By that time, texts were missing, transmission of the teaching was cut off, and there was no way to understand the orthodox meaning of the tradition. In addition, the Ming revivalists’ motives were not always genuine, and as happened in the twentieth century with monks such as Taixu, the Ming Yogacarans only wished to use Yogacara in order to reaffirm their own understanding of Buddhism.

This chapter, therefore, is merely a pointer to the root of the problem, having dealt as it did with Ouyang’s critique of what he considered deviations from the true teaching. What unified those cases of deviation was a reliance on fundamental doctrine that constitutes the root problem. The treatment of this root of the problem will be the main theme of the next chapter.

_______________

Notes:

1 The term he used for those dominant schemes is expositions (Skt. viniscaya Ch., Chinese), which can also mean “determination” or further analysis.

2 For example when discussing the notion of two truths he focused on conventional truth. In another section where he discussed the substance and function, he focused on the function, etc.

3 Ouyang Jingwu, “Expositions and Discussions of Vijnaptyimatra [Chinese],” in Collected Writings of Master Ouyang [Chinese] (Taibei: Xinwenfeng Press, 1976), 1359.

4 Ouyang Jingwu, Expositions and Discussions of Vijnaptyimatra, 1359-60.

5 Hu Shi studied especially the Chan School and was concern with the historical study of Chan as an historical phenomena and not spiritual (see Hu Shi’s famous debate with D.T. Suzuki in Hu Shih, “Ch'an (Zen) Buddhism in China its History and Method,” Philosophy East and West 3, No. 1 (1953): 3- 24).

6 Sectarian boundaries were never as tight in Chinese Buddhism as they were in Japanese Buddhism. For years, scholars in the West, influenced by Japanese scholars and Buddhists who introduced East Asian Buddhism to the west, tended to understand the meaning of the term “school” (Ch: zong, Chinese) in the Japanese sense of a different set of teachings, key texts and separate institutions. Scholars thus tended to view Chinese Buddhism as the predecessor of later Japanese Buddhism. Whenever aspects of Chinese Buddhism seemed not to fit the sectarian model it was often considered to be a sign of degeneration of the “pure” model. We now know that the meaning of “school” in China was different and more flexible than in Japan. However we are far from fully understanding the complexity and array of meanings of the term zong. What sense of identity a Buddhist felt when she was identified herself as belonging to a certain zong or school and how this notion changed over time. (For more see Robert Sharf’s appendix “On Esoteric Buddhism in China” in Robert Sharf, Coming to Terms with Chinese Buddhism: A Reading of the Treasure Store Treatise. (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2002), 263-78.

7 For example the great Ming dynasty monks Hanshan Deqing (Chinese, 1546-1623) and Ouyi Zhixu (Chinese, 1599-1656).

8 See Taixu, “The Characteristic Feature of Chinese Buddhism is Chan [Chinese],” in The Complete Works of Taixu [Chinese] (Taibei Shi: Hai chao yin she, 1950), 549. (Hereafter TXQS).

9 The biography of Xuyun belongs to the genre of nianpu or yearly chronicle. It was not written by Xuyun himself but compiled by Xuyun’s disciple Cen Xuelü (Chinese,1882-1963) out of notes and stories collected by his disciples and was supposedly later approved by Xuyun. The third edition of the nianpu includes a letter from Xuyun saying that his eyesight and hearing prevented him from reading Cen’s manuscript thoroughly and that there were some mistakes in it that he asked his disciples to correct. See the section with the attached materials before the table of content in Xuyun, Revised and Extended Version of Master Xuyun’s Chronological Biography and Sermons Collection [Chinese] (Taibei: Xiuyuan Chanyuan, 1997).

10 Charles Luk (trans.). Empty Cloud: The Autobiography of the Chinese Zen Master Xu Yun (Dorset: Element Books, 1988), 157.

11 [Chinese! Cited in Fang Guangchang, “Yang Wenhui’s Philosophy of Editing the Canon [Chinese],” Zhonghua foxue xuebao. 13, (2005): 179-205.

12 See Deng Zimei, 20th Century Chinese Buddhism, 228.

13 Chinese, Ouyang Jingwu, Expositions and Discussions of Vijnaptyimatra, 1359.

14 See the second case in the Wumenguan Chinese, T48.2005.0293a15-b29.

15 See Ouyang Jingwu, "Preface to the Yogacarabhumi [Chinese]," in Collected Writings of Master Ouyang [Chinese] (Taibei: Xinwenfeng Press, 1976), 317. More on this topic in Chapter Five below.

16 See Ouyang "Discussing the Research of the Inner Studies,” [Chinese]," Neixue neikan 2 (1924): 5.

This was not the case with his own disciple Lü Cheng, who argues that Chan was born out of the same kind of philosophy can be found in the Awakening of Faith. See Lü Cheng, “The Awakening of Faith and Chan: A Study in the Historical Background of the Awakening of Faith [Chinese]," in Investigating the Awakening of Faith and the Suramgama Sutra [Chinese], ed. Zhang Mantao, (Taibei: Da sheng wen hua chu ban she, 1978).

17 This is a famous and controversial argument leveled by scholars such as Hakamaya Noriaki and Matsumoto Shiro. Despite the radical claim, even Hakamaya made a clear distinction between the Japanese tradition, which is not Buddhism, and the Chinese Chan Buddhism, which does have a “critical philosophy” approach. See Paul Swanson, "Why They Say Zen Is Not Buddhism: Recent Japanese Critiques of Buddha-Nature," in Pruning the Bodhi Tree: The Storm over Critical Buddhism, ed. Paul Swanson and Jamie Hubbard, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997), 19.

18 For more about the five grades in Tiantai thought see T33.1716.733.a12-b28 and Leon Hurvitz, “Chih-I (538-597): An Introduction to the Life and Ideas of a Chinese Buddhist Monk,” PhD Diss., Columbia Unuversity, 1959, 409. The reason Ouyang argues that Zhiyi attained “only” the five stages can be found in the colophon for Mohe zhiguan (Chinese). Guangding, Zhiyi’s disciple, tells us that Zhiyi “died while meditating, having attained the level of the five grades.”

19 (Chinese), See Ouyang Jingwu, Discussing the Research of the Inner Studies, 1360.

20 Leveling such serious accusations without providing any systematic and rational account for this criticism led some scholars, such as Jiang Canteng, to argue that the only motive behind Ouyang’s attack was nothing more than a wish to propagate his own vision of Yogacara while using weak and arbitrary argumentation; see Jiang Canteng, Controversies and Developments in Chinese Modern Buddhist Thought [Chinese] (Taibei: Nantian Press, 1998), 544-552. Although I think that his motives were more genuine and that he did have some specific critiques regarding those schools, which Jiang completely ignores, I agree that in contrast to his more careful analysis of the Indian texts his critiques of the Chinese schools were somewhat “weak and arbitrary.”

21 A reference to the Samdhinirmocana sutra which discusses the Buddha’s three turnings of the wheels. The first turning is in Benaras where he preached his first sermons on the four noble truths, the second is his teaching of emptiness in the Prajnaparamita sutras and the third time is when he proclaimed the middle path of representation-only which is the middle path between the first two turnings of the wheel.

22 A rather convoluted way to suggest that one can use concepts to differentiate between different dimensions and nuances within the teaching, but one cannot claim that there are several “teachings.” The Buddhist teaching is just one.

23 [Chinese] See Ouyang Jingwu, Discussing the Research of the Inner Studies, 1365.

24 yah pratityasamutpada( sunyatam tam pracaksmahe | sa prajñaptir upadaya pratipat saiva madhyam! || MMK 24,18.

25 Here Ouayng refers to the perfected nature (Skt. parinispanna), part of the three natures theory of the Yogacara School. The Chinese rendering that he uses literally means “the perfect and real” (Chinese) and Ouyang is playing on the two notions when he determines that the Tiantai meditation can get us only to what is “perfect” (Ch. Yuan, Chinese) but not to what is “real” (Ch. Shi, Chinese).

26 Originally general and shared characteristics (Skt. samanyalaksana Ch. ....) however according to the Tang Tiantai teacher Zhanran (Chinese, 711–782) the general characteristics are also called shared characteristics (see T46.1912.299.a01, Chinese). Usually this concept appears together with its opposite ,the “specific characteristics” of a phenomena (Skt. svalaksana Ch., Chinese). While the general characteristics include characteristics shared by a larger group, such as all phenomena are non-self or impermanent, the specific characteristic for water will be wetness and for earth solidity etc. Here it seems that Ouyang refer to a fuzzy and confused usage of categories and an incoherent teaching that follows from that.

27 (Chinese?) See Ouyang Jingwu, “The General Meaning of Mind Studies” [Chinese] in Ouyang Jingwu Writing Collection [Chinese], edited by Hong Qisong and Huang Qilin (Taibei: Wenshu chu ban she, 1988), 180-181.

28 In the sense that both are legitimate texts in the Yogacara tradition.

29 The four unobstructed understandings of a Bodhisattva (Skt. pratisamvida Ch., Chinese). These are the four skills or powers of a Bodhisattva which enable him to naturally grasp and expresse the truth of the doctrine. The four are (1) dharma or the ability to grasp and express the Dharma (2) artha or the ability to grasp and express the meaning of the teaching and make judgment about it (3) nirukti the ability to grasp and express the doctrine in any language and understand the different dialects (4) pratibhana or the ability to speak skillfully to others according to their own needs and level; see Foguang dictionary, 1778.

30 Skt. catuh samgraha vastu Ch., Chinese. These are four methods of cultivation, which attract people to the Buddhist path and can lead them to enlightenment. The four are (1) Giving (Skt. dana samgraha Ch., Chinese) (2) Sweet words (Skt. priya vadita samgraha Ch., Chinese) (3) Beneficial conduct (Skt arthacariya samgraha Ch., Chinese) and (4) Sympathizing with others (Skt. samanartha samgraha Ch., Chinese) see Foguang dictionary, 1853.

31 (Chinese) See Ouyang Jingwu, The General Meaning of Mind Studies, 181.

32 Ouyang Jingwu, "Preface to the Yogacarabhumi [Chinese]," in Collected Writings of Master Ouyang [Chinese] (Taibei: Xinwenfeng Press, 1976), 350.

33 In the sense that he did not propagate it in its own right but only to support his own teaching.

34 Ouyang Jingwu, Preface to the Yogacarabhumi, 352. Indeed the Zongjinglu quotes heavily from the writings of Kuiji, Xuanzang’s disciple. The role of Yogacara in the thought of Yanshou, a well known Chan teacher and a master of doctrine of the later Tang period, is an important link from the earlier Yogacara to the way Yogacara was later perceived in East Asia, especially in China. Traces of Yanshou can be seen in Ouyang’s writing as well, and it is evident from his comments regarding Yanshou that Ouyang perceived him as the last stand of Yogacara teaching in China before its long period of dormancy.

35 Shi Shengyan. "Late Ming Yogacara Thinkers and Their Thought [Chinese]," Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal [Chinese] 2 (1987): 4.

36 Although lately there is a growing interest in later Chinese Buddhism, there is still a serious lacuna in the study of these figures. For a general introduction see Yu Chun-fang, "Ming Buddhism," in The Cambridge History of China, ed. D.C. Twitchet (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 893-952.

37 For example the lineage that started with Shaojue Guangcheng (Chinese, ??~1600) who was Zhuhong’s disciple and wrote a lexicon of the Cheng weishi lun, Chinese. Shengyan quotes Shaoguan as using terminologies from the two schools in his writings. For example, when he says, “The esteemed theory of [Tiantai’s] Four Teachings is exactly the three Buddha lands [of the Faxing School]. The Four teachings which live together, the skillful means and the two teachings are in fact the one perfect teaching.” (Shi Shengyan. Late Ming Yogacara Thinkers and Their Thought, 27). Other examples he gives are Dazhen and the eminent Ming monk Ouyi, who also studied both traditions at the same time.

38 Wu Jiang, Buddhist Logic and Apologetics in Seventeenth-Century China.

39 A one-fascicle work by the late Ming monk Xuelang Hongwen. Xuelang prescribed the 8 essentials work of the Faxiang School and summarize their content. See X55.899.

40 A ten fascicles work of Ouyi Zhixu on the Cheng weishi lun see X51.824. Also known as Cheng weishi lun guanxin fayao (Chinese) X51.824.

41 Literally “they had a view through a hole in the door or a window,” but by extension it implies also narrow sectarian views.

42 (Chinese) ? Ouyang Jingwu, Preface to the Yogacarabhumi, 352.

43 Especially in Chengguan sub-commentary on the Huayan Sutra (Chinese).

44 His treatment of the Ming revivalists was less comprehensive in this text, compared with his preface to the Yogacarabhumi. Cheng Gongrang argues convincingly that the reason Ouyang treated the Ming predecessors less in this text is that while in his preface to the Yogacarabhumi Ouyang was interested in reforming the Weishi school per se, at this stage, five years later, he had expanded his objective to reform Chinese Buddhism, and even the course of the general intellectual development of China as a whole (Cheng Gongrang, Studies in Ouyang Jingwu's Buddhist Thought, 149).

45 To the best of my knowledge this pair of concepts appears for the first time together in Vasubandhu’s commentary on the Mahayanasamgraha (see T31.1597.366a15-29). It is later often used in Chinese commentaries including in the Cheng weishi lun, and other thinkers often used by Ouyang such as Kuiji or Dunlun.

46 According to Gong Jun, the Awakening of Faith did not attract the attention of Zhiyi, Tiantai’s foremost thinker. Acceptance of the Awakening of Faith as a part of Tiantai tradition that began with Zhanran in the Tang dynasty, who gave his own interpretation to the Awakening of Faith’s claim that sunchness and phenomenal world are “neither same nor different”. Zhanran did this in order to make a clear distinction between the Tiantai tradition he wished to revive and the Huayan tradition, which gain popularity during his lifetime. In the Song dynasty the well-known debate between the shanjia and shanwai factions continue to debate the Awakening of Faith where Zhili of the shanjia faction continued Zhanran’s interpretation and Wuen from the shanwai interpreted in a manner that came much closer to the Huayan interpretation. Ouyang, who rejected the notion of a monistic approach to the problem of the relationship between suchness and the phenomenal world, disregarded the inner disagreements within the Tiantai school in order to reject the doctrinal foundation of Chinese Buddhism altogether. See furthe Gong Jun, The Awakening of Faith and Sinification of Buddhism [Chinese] (Wen jin chu ban she, 1995, 158-163.