Re: Freda Bedi, by Wikipedia

Part 1 of 2

Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal [EXCERPT]

by Eric Schlosser

© 2002, 2001 by Eric Schlosser

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

Chapter 1: The American Way

The Founding Fathers

CARL N. KARCHER is one of the fast food industry's pioneers. His career extends from the industry's modest origins to its current hamburger hegemony. His life seems at once to be a tale by Horatio Alger, a fulfillment of the American dream, and a warning about unintended consequences. It is a fast food parable about how the industry started and where it can lead. At the heart of the story is southern California, whose cities became prototypes for the rest of the nation, whose love of the automobile changed what America looks like and what Americans eat.

Carl was born in 1917 on a farm near Upper Sandusky, Ohio. His father was a sharecropper who moved the family to new land every few years .. The Karchers were German-American, industrious, and devoutly Catholic. Carl had six brothers and a sister. "The harder you work." their father always told them, "the luckier you become." Carl dropped out of school after the eighth grade and worked twelve to fourteen hours a day on the farm, harvesting with a team of horses, baling hay, milking and feeding the cows. In 1937, Ben Karcher, one of Carl's uncles, offered him a job in Anaheim, California. After thinking long and hard and consulting with his parents, Carl decided to go west He was twenty years old and six-foot-four, a big strong farm boy. He had never set foot outside of northern Ohio. The decision to leave home felt momentous, and the drive to California took a week. When he arrived in Anaheim - and saw the palm trees and orange groves, and smelled the citrus in the air - Carl said to himself, "This is heaven."

Anaheim was a small town in those days, surrounded by ranches and farms. It was located in the heart of southern California's citrus belt, an area that produced almost all of the state's oranges, lemons, and tangerines. Orange County and neighboring Los Angeles County were the leading agricultural counties in the United States, growing fruits, nuts, vegetables, and flowers on land that only a generation earlier had been a desert covered in sagebrush and cactus. Massive irrigation projects, built with public money to improve private land, brought water from hundreds of miles away. The Anaheim area alone boasted about 70,000 acres of Valencia oranges, as well as lemon groves and walnut groves. Small ranches and dairy farms dotted the land, and sunflowers lined the back roads. Anaheim had been settled in the late nineteenth century by German immigrants hoping to create a local wine industry and by a group of Polish expatriates trying to establish a back-to-the-land artistic community. The wineries flourished for three decades; the art colony collapsed within a few months. After World War I, the heavily German character of Anaheim gave way to the influence of newer arrivals from the Midwest, who tended to be Protestant and conservative and evangelical about their faith. Reverend Leon L. Myers - pastor of the Anaheim Christian Church and founder of the local Men's Bible Club - turned the Ku Klux Klan into one of the most powerful organizations in town. During the early 1920s, the Klan ran Anaheim's leading daily newspaper, controlled the city government for a year, and posted signs on the outskirts of the City greeting newcomers with the acronym "KIGY" (Klansmen I Greet You).

Carl's uncle Ben owned Karcher's Feed and Seed Store, right in the middle of downtown Anaheim. Carl worked there seventy-six hours a week, selling goods to local farmers for their chickens, cattle, and hogs. During Sunday services at St. Boniface Catholic Church, Carl spotted an attractive young woman named Margaret Heinz sitting in a nearby pew. He later asked her out for ice cream, and the two began. dating. Carl became a frequent visitor to the Heinz farm on North Palm Street. It had ten acres of orange trees and a Spanish-style house where Margaret, her parents, her seven brothers, and her seven sisters lived. The place seemed magical. In the social hierarchy of California's farmers, orange growers stood at the very top; their homes were set amid fragrant evergreen trees that produced a lucrative income. As a young boy in Ohio, Carl had been thrilled on Christmas mornings to receive a single orange as a gift from Santa. Now oranges seemed to be everywhere.

Margaret worked as a secretary at a law firm downtown. From her office window on the fourth floor, she could watch Carl grinding feed outside his uncle's store. After briefly returning to Ohio, Carl went to work for the Armstrong Bakery in Los Angeles. The job soon paid $.24 a week, $6 more than he'd earned at the feed store - and enough to start a family. Carl and Margaret were married in 1939 and had their first child within a year.

Carl drove a truck for the bakery, delivering bread to restaurants and markets in west L.A. He was amazed by the number of hot dog stands that were opening and by the number of buns they went through every week. When Carl heard that a hotdog cart was for sale - on Florence Avenue across from the Goodyear factory - he decided to buy it. Margaret strongly opposed the idea, wondering where he'd find the money. He borrowed $311 from the Bank of America, using his car as collateral for the loan, and persuaded his wife to give him $15 in cash from her purse. ''I'm in business for myself now," Carl thought, after buying the cart, "I'm on my way." He kept his job at the bakery and hired two young men to work the cart during the hours he was delivering bread. They sold hot dogs, chili dogs, and tamales for a dime each, soda for a nickel. Five months after Carl bought the cart, the United States entered World War II, and the Goodyear plant became very busy. Soon he had enough money to buy a second hot dog cart, which Margaret often ran by herself, selling food and counting change while their daughter slept nearby in the car.

Southern California had recently given birth to an entirely new lifestyle -- and a new way of eating. Both revolved around cars. The cities back East had been built in the railway era, with central business districts linked to outlying suburbs by commuter train and trolley. But the tremendous growth of Los Angeles occurred at a time when automobiles were finally affordable. Between 1920 and 1940, the population of southern California nearly tripled, as about 2 million people arrived from across the United States. While cities in the East expanded through immigration and became more diverse, Los Angeles became more homogenous and white. The city was inundated with middle-class arrivals from the Midwest, especially in the years leading up to the Great Depression. Invalids, retirees, and small businessmen were drawn to southern California by real estate ads promising a warm climate and a good life. It was the first large-scale migration conducted mainly by car. Los Angeles soon became unlike any other city the world had ever seen, sprawling and horizontal, a thoroughly suburban metropolis of detached homes - a glimpse of the future, molded by the automobile. About 80 percent of the population had been born elsewhere; about half had rolled into town during the previous five years. Restlessness, impermanence, and speed were embedded in the culture that soon emerged there, along with an openness to anything new. Other cities were being transformed by car ownership, but none was so profoundly altered. By 1940, there were about a million cars in Los Angeles, more cars than in forty-one states.

The automobile offered drivers a feeling of independence and control. Daily travel was freed from the hassles of rail schedules, the needs of other passengers, and the location of trolley stops. More importantly, driving seemed to cost much less than using public transport - an illusion created by the fact that the price of a new car did not include the price of building new roads. Lobbyists from the oil, tire, and automobile industries, among others, had persuaded state and federal agencies to assume that fundamental expense. Had the big auto companies been required to pay for the roads - in the same way that trolley companies had to lay and maintain track - the landscape of the American West would look quite different today.

The automobile industry, however, was not content simply to reap the benefits of government-subsidized road construction. It was determined to wipe out railway competition by whatever means necessary. In the late 1920s, General Motors secretly began to purchase trolley systems throughout the United States, using a number of front corporations. Trolley systems in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Montgomery, Alabama, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and El Paso, Texas, in Baltimore, Chicago, New York City, and Los Angeles - more than one hundred trolley systems in all- were purchased by GM and then completely dismantled, their tracks ripped up, their overhead wires torn down. The trolley companies were turned into bus lines, and the new buses were manufactured by GM.

General Motors eventually persuaded other companies that benefited from road building to help pay for the costly takeover of America's trolleys. In 1947, GM and a number of its allies in the scheme were indicted on federal antitrust charges. Two years later, the workings of the conspiracy, and its underlying intentions, were. exposed during a trial in Chicago. GM, Mack Truck, Firestone, and Standard Oil of California were all found guilty on one of the two counts by the federal jury. The investigative journalist Jonathan Kwitny later argued that the case was "a fine example of what can happen when important matters of public policy are abandoned by government to the self-interest of corporations." Judge William J. Campbell was not so outraged. As punishment, he ordered GM and the other companies to pay a fine of $5,000 each. The executives who had secretly plotted and carried out the destruction of America's light rail network were fined $1 each. And the postwar reign of the automobile proceeded without much further challenge.

The nation's car culture reached its height in southern California, inspiring innovations such as the world's first motel and the first drive-in bank. A new form of eating place emerged. "People with cars are so lazy they don't want to get out of them to eat!" said Jesse G. Kirby, the founder of an early drive-in restaurant chain. Kirby's first "Pig Stand" was in Texas, but the chain soon thrived in Los Angeles, alongside countless other food stands offering "curb service." In the rest of the United States, drive-ins were usually a seasonal phenomenon, closing at the end of every summer. In southern California, it felt like summer all year long, the drive-ins never closed, and a whole new industry was born.

The southern California drive-in restaurants of the early 1940s tended to be gaudy and round, topped with pylons, towers, and flashing signs. They were "circular-meccas of neon," in the words of drive-in historian Michael Witzel, designed to be easily spotted from the road. The triumph of the automobile encouraged not only a geographic separation between buildings, but also a manmade landscape that was loud and bold. Architecture could no longer afford to be subtle; it had to catch the eye of motorists traveling at high speed. The new drive-ins competed for attention, using all kinds of visual lures, decorating their buildings in bright colors and dressing their waitresses in various costumes. Known as "carhops," the waitresses - who carried trays of food to patrons in parked cars - often wore short skirts and dressed up like cowgirls, majorettes, Scottish lasses in kilts. They were likely to be attractive, often received no hourly wages, and earned their money through tips and a small commission on every item they sold. The carhops had a strong economic incentive to be friendly to their customers, and drive-in restaurants quickly became popular hangouts for teenage boys. The drive-ins fit perfectly with the youth culture of Los Angeles. They were something genuinely new and different, they offered a combination of girls and cars and late-night food, and before long they beckoned from intersections all over town.

Speedee Service

BY THE END OF 1944, Carl Karcher owned four hot dog carts in Los Angeles. In addition to running the carts, he still worked full-time for the Armstrong Bakery. When a restaurant across the street from the Heinz farm went on sale, Carl decided to buy it. He quit the bakery, bought the restaurant, fixed it up, and spent a few weeks learning how to cook. On January 16, 1945, his twenty-eighth birthday, Carl's Drive-In Barbeque opened its doors. The restaurant was small, rectangular, and unexceptional, with red tiles on the roof. Its only hint of flamboyance was a five-pointed star atop the neon sign in the parking lot. During business hours, Carl did the cooking, Margaret worked behind the cash register, and carhops served most of the food. After closing time, Carl stayed late into the night, cleaning the bathrooms and mopping the floors. Once a week, he prepared the "special sauce" for his hamburgers, making it in huge kettles on the back porch of his house, stirring it with a stick and then pouring it into one-gallon jugs.

After World War II, business soared at Carl's Drive-In Barbeque, along with the economy of southern California. The oil business and the film business had thrived in Los Angeles during the 1920s and 1930s. But it was World War II that transformed southern California into the most important economic region in the West. The war's effect on the state, in the words of historian Carey McWilliams, was a "fabulous boom." Between 1940 and 1945, the federal government spent . nearly $20 billion in California, mainly in and around Los Angeles, building airplane factories and steel mills, military bases and port facilities. During those six years, federal spending was responsible for nearly half of the personal income in southern California. By the end of World War II, Los Angeles was the second-largest manufacturing center in America, with an industrial output surpassed only by that of Detroit. While Hollywood garnered most of the headlines, defense spending remained the focus of the local economy for the next two decades, providing about one-third of its jobs.

The new prosperity enabled Carl and Margaret to buy a house five blocks away from their restaurant. They added more rooms as the family grew to include twelve children: nine girls and three boys. In the early 1950s Anaheim began to feel much less rural and remote. Walt Disney bought 160 acres of orange groves just a few miles from Carl's Drive-In Barbeque, chopped down the trees, and started to build Disneyland. In the neighboring town of Garden Grove, the Reverend Robert Schuller founded the nation's first Drive-in Church, preaching on Sunday mornings at a drive-in movie theater, spreading the Gospel through the little speakers at each parking space, attracting large crowds with the slogan "Worship as you are ... in the family car." The city of Anaheim started to recruit defense contractors, eventually persuading Northrop, Boeing, and North American Aviation to build factories there. Anaheim soon became the fastest-growing city in the nation's fastest-gr-owing state. Carl's Drive-In Barbeque thrived, and Carl thought its future was secure. And then he heard about a restaurant in the "Inland Empire." sixty miles east of Los Angeles, that was selling high-quality hamburgers for 15 cents each - 20 cents less than what Carl charged. He drove to E Street in San Bernardino and saw the shape of things to come. Dozens of people were standing in line to buy bags of "McDonald's Famous Hamburgers."

Richard and Maurice McDonald had left New Hampshire for southern California at the start of the Depression, hoping to find jobs in Hollywood. They worked as set builders on the Columbia Film Studios back lot, saved their money, and bought a movie theater in Glendale. The theater was not a success. In 1937 they opened a drive-in restaurant in Pasadena, trying to cash in on the new craze, hiring three carhops and selling mainly hot dogs. A few years later they moved to a larger building on E Street in San Bernardino and opened ,the McDonald Brothers Burger Bar Drive-In. The new restaurant was located near a high school, employed twenty carhops, and promptly made the brothers rich. Richard and "Mac" McDonald bought one of the largest houses in San Bernardino, a hillside mansion with a tennis court and a pool.

By the end of the 1940s the McDonald brothers had grown dissatisfied with the drive-in business. They were tired of constantly looking for new carhops and short-order cooks - who were in great demand - as the old ones left for higher-paying jobs elsewhere. They were tired of replacing the dishes, glassware, and silverware their teenage customers constantly broke or ripped off. And they were tired of their teenage customers. The brothers thought about selling the restaurant. Instead, they tried something new.

The McDonalds fired all their carhops in 1948, closed 'their restaurant, installed larger grills, and reopened three months later with a radically new method of preparing food. It was designed to increase .the speed, lower prices, and raise the volume of sales. The brothers eliminated almost two-thirds of the items on their old menu. They got rid of everything that had to be eaten with a knife, spoon, or fork. The only sandwiches now sold were hamburgers or cheeseburgers. The brothers got rid of their dishes and glassware, replacing them with paper cups, paper bags, and paper plates. They divided the food preparation into separate tasks performed by different workers. To fill a typical order, one person grilled the. hamburger; another "dressed" and wrapped it; another prepared the milk shake; another made the fries; and another worked the counter. For the first time, the guiding principles of a factory assembly line were applied to a commercial kitchen. The new division of labor meant that a worker only had to be taught how to perform one task. Skilled and expensive short-order cooks were no longer necessary. All of the burgers were sold with the same condiments: ketchup, onions, mustard, and two pickles. No substitutions were allowed. The McDonald brothers' Speedee Service System revolutionized the restaurant business. An ad of theirs seeking franchisees later spelled out the benefits of the system: "Imagine -- No Carhops - No Waitresses - No Dishwashers "- No Bus Boys - The McDonald's System is Self-Service!"

Richard McDonald designed a new building for the restaurant, hoping to make it easy to spot from the road. Though untrained as an architect, he came up with a design that was simple, memorable, and archetypal. On two sides of the roof he put golden arches, lit by neon at night, that from a distance formed the letter M. The building effortlessly fused advertising with architecture and spawned one of the most famous corporate logos in the world.

The Speedee Service System, however, got off to a rocky start. Customers pulled up to the restaurant and honked their horns, wondering what had happened to the carhops, still expecting to be served. People were not yet accustomed to waiting in line and getting their own food. Within a few weeks, however, the new system gained acceptance, as word spread about the low prices and good hamburgers. The McDonald brothers now aimed for a much broader clientele. They . employed only young men, convinced that female workers would attract teenage boys to the restaurant and drive away other customers. Families soon lined up to eat at McDonald's. Company historian John F. Love explained the lasting significance of McDonald's new self-service system: "Working-class families could finally afford to feed their kids restaurant food."

San Bernardino at the time was an ideal setting for all sorts of cultural experimentation. The town was an odd melting-pot of agriculture and industry located 'on the periphery of the southern California boom, a place that felt out on the edge. Nicknamed "San Berdoo," it was full of citrus' groves, but sat next door to the smokestacks and steel mills of Fontana. San Bernardino had just sixty thousand inhabitants;· but millions of people passed through there every year. It was the last stop on Route 66, end of the line for truckers, tourists, and migrants from the East. Its main street was jammed with drive-ins and cheap motels. The same year the McDonald brothers opened their new self-service restaurant, a group of World War II veterans in San Berdoo, alienated by the dullness of civilian life, formed a local motorcycle club, borrowing the nickname of the U.S. Army's Eleventh Airborne Division: "Hell's Angels." The same town that gave the world the golden arches also gave it a biker gang that stood for a totally antithetical set of values. The Hell's Angels flaunted their dirtiness, celebrated disorder, terrified families and small children instead of trying to sell them burgers, took drugs, sold drugs, and injected into American pop culture an anger and a darkness and a fashion statement - T-shirts and tom jeans, black leather jackets and boots, long hair, facial hair, swastikas, silver skull rings and other satanic trinkets, earrings, nose rings, body piercings, and tattoos - that would influence a long line of rebels from Marlon Brando to Marilyn Manson. The Hell's Angels were the anti-McDonald's, the opposite of clean and cheery. They didn't care if you had a nice day, and yet were as deeply American in their own way as any purveyors of Speedee Service. San Bernardino in 1948 supplied the nation with a new yin and yang, new models of conformity and rebellion. "They get angry when they read about how filthy they are," Hunter Thompson later wrote of the Hell's Angels, "but instead of shoplifting some deodorant, they strive to become even filthier."

Burgerville USA

AFTER VISITING SAN BERNARDINO and seeing the long lines at McDonald's, Carl Karcher went home to Anaheim and decided to open his own self-service restaurant. Carl instinctively grasped that the new car culture would forever change America. He saw what was coming, and his timing was perfect. The first Carl's Jr. restaurant opened' in 1956 - the same year that America got its first shopping mall and that Congress passed the Interstate Highway Act. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had pushed hard for such a bill; during World War II, he'd been enormously impressed by Adolf Hitler's Reichsautobahn, the world's first superhighway system. The Interstate Highway Act brought autobahns to the United States and became the largest public works project in the nation's history, building 46,000 miles of road with more than $130 billion of federal money. The new highways spurred car sales, truck sales, and the construction of new suburban homes. Carl's first self-service restaurant was a success, and he soon opened others near California's new freeway off-ramps. The star atop his drive-in sign became the mascot of his fast food chain. It was a smiling star in little booties, holding a burger and a shake.

Entrepreneurs from all over the country went to San Bernardino, visited the new McDonald's, and built imitations of the restaurant in their hometowns. "Our food was exactly the same as McDonald's." the founder of a rival chain later admitted. "If I had looked at McDonald's . and saw someone flipping hamburgers while he was hanging by his feet, I would have copied it." America's fast food chains were not launched by large corporations relying upon focus groups and market research. They were started by door-to-door salesmen, short-order cooks, orphans, and dropouts, by eternal optimists looking for a piece of the next big thing. The start-up costs of a fast food restaurant were low, the profit margins promised to be high, and a wide assortment of ambitious people were soon buying grills and putting up signs.

William Rosenberg dropped out of school at the age of fourteen, delivered telegrams for Western Union, drove an ice cream truck, worked as a door-to-door salesman, sold sandwiches and coffee to factory workers in Boston, and then opened a small doughnut shop in 1948, later calling it Dunkin' Donuts. Glen W. Bell, Jr., was a World War II veteran, a resident of San Bernardino who ate at the new McDonald's and decided to copy it, using the assembly-line system to make Mexican food and founding a restaurant chain later known as Taco Bell. Keith G. Cramer, the owner of Keith's Drive-In Restaurant in Daytona Beach, Florida, heard about the McDonald brothers' new restaurant, flew to southern California, ate at McDonald's, returned to Florida, and with his father-in-law, Matthew Burns, opened the first Insta-Burger-King in 1953. Dave Thomas started working in a restaurant at the age of twelve, left his adoptive father, took a room at the YMCA, dropped out of school at fifteen, served as a busboy and a cook, and eventually opened his own place in Columbus, Ohio, calling it Wendy's Old-Fashioned Hamburgers restaurant. Thomas S. Monaghan spent much of his childhood in a Catholic orphanage and a series of foster homes, worked as a soda jerk, barely graduated from high school, joined the Marines, and bought a pizzeria in Ypsilanti, Michigan, with his brother, securing the deal through a down payment of $75. Eight months later Monaghan's brother decided to quit and accepted a used Volkswagen Beetle for his share of a business later known as Domino's.

The story of Harland Sanders is perhaps the most remarkable. Sanders left school at the age of twelve, worked as a farm hand, a mule tender, and a railway fireman. At various times he worked as a lawyer without having a law degree, delivered babies as a part-time obstetrician without having a medical degree, sold insurance door to door, sold Michelin tires, and operated a gas station in Corbin, Kentucky. He served home-cooked food at a small dining-room table in the back, later opened a popular restaurant and motel, sold them to pay off debts, and at the age of sixty-five became a traveling salesman once again, offering restaurant owners the "secret recipe" for his fried chicken. The first Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant opened in 1952, near Salt Lake City, Utah. Lacking money to 'promote the new chain, Sanders dressed up like a Kentucky colonel, sporting a white suit and a black string tie. By the early 19605, Kentucky Fried Chicken was the largest restaurant chain in the United States, and Colonel Sanders was a household name. In his autobiography, Life As I Have Known It Has Been "Finger-lickin' Good," Sanders described his ups and downs, his decision at the age of seventy-four to be rebaptized and born again, his lifelong struggle to stop cursing. Despite his best efforts and a devout faith in Christ, Harland Sanders admitted that it was still awfully hard "not to call a no-good, lazy, incompetent, dishonest s.o.b. by anything else but his rightful name."

For every fast food idea that swept the nation, there were countless others that flourished briefly - or never had a prayer. There were chains with homey names, like Sandy's, Carrol's, Henry's, Winky's, and Mr. Fifteen's. There were chains with futuristic names, like the Satellite Hamburger System and Kelly's Jet System. Most of all, there were chains named after their main dish: Burger Chefs, Burger Queens, Burgerville USAs, Yumy Burgers, Twitty Burgers, Whataburgers, Dundee Burgers, Biff-Burgers, O.K. Big Burgers, and Burger Boy Food-O-Ramas.

Many of the new restaurants advertised an array of technological wonders. Carhops were rendered obsolete by various remote-control ordering systems, like the Fone-A-Chef, the Teletray, and the ElectroHop. The Motormat was an elaborate rail system that transported food and beverages from the kitchen to parked cars. At the Biff-Burger chain, Biff-Burgers were "roto-broiled" beneath glowing quartz tubes that worked just like a space heater. Insta-Burger-King restaurants featured a pair of "Miracle Insta Machines," one to make milk shakes, the other to cook burgers. "Both machines have been thoroughly perfected," the company assured prospective franchisees, "are of foolproof design - can be easily operated even by a moron." The InstaBurger Stove was an elaborate contraption. Twelve hamburger patties entered it in individual wire baskets: circled two electric heating elements, got cooked on both sides, and then slid down a chute into a pan of sauce, while hamburger buns toasted in a nearby slot. This Miracle Insta Machine proved overly complex, frequently malfunctioned, and was eventually abandoned by the Burger King chain.

The fast food wars in southern California - the birthplace of Jack in the Box, as well as McDonald's, Taco Bell, and Carl's Jr. - were especially fierce. One by one, most of the old drive-ins closed, unable to compete against the less expensive, self-service burger joints. But Carl kept at it, opening new restaurants up and down the state, following the new freeways. Four of these freeways - the Riverside, the Santa Ana, the Costa Mesa, and the Orange - soon. passed through Anaheim. Although Carl's Jr. was a great success, a few of Carl's other ideas should have remained on the drawing board. Carl's Whistle Stops featured employees dressed as railway workers, "Hobo Burgers," and toy electric trains that took orders to the kitchen. Three were built in 1966 and then converted to Carl's Jr. restaurants a few years later. A coffee shop chain with a Scottish theme also never found its niche. The waitresses at "Scot's" wore plaid skirts, and the dishes had unfortunate names, such as "The Clansman."

The leading fast food chains spread nationwide; between 1960 and 1973, the number of McDonald's restaurants grew from roughly 250 to 3,000. The Arab oil embargo of 1973 gave the fast food industry a bad scare, as long lines at gas stations led many to believe that America's car culture was endangered. Amid gasoline shortages, the value of McDonald's stock fell. When the crisis passed, fast food stock prices recovered, and McDonald's intensified its efforts to open urban, as well as suburban, restaurants. Wall Street invested heavily in the fast food chains, and corporate managers replaced many of the early pioneers. What had begun as a series of small, regional businesses became a fast food industry, a major component of the American economy.

Progress

IN 1976, THE NEW HEADQUARTERS of Carl Karcher Enterprises, Inc. (CKE) was built on the same land in Anaheim where the Heinz farm had once stood. The opening-night celebration was one of the high points of Carl's life. More than a thousand people gathered for a black-tie party at a tent set up in the parking lot. There was dinner and dancing on a beautiful, moonlit night. Thirty-five years after buying his first hot dog cart, Carl Karcher now controlled one of the largest privately owned fast food chains in the United States. He owned hundreds of restaurants. He considered many notable Americans to be his friends, including Governor Ronald Reagan, former president Richard Nixon, Gene Autry, Art Linkletter, Lawrence Welk, and Pat Boone. Carl's nickname was "Mr. Orange County." He was a benefactor of Catholic charities, a Knight of Malta, a strong supporter of right-to-life causes. He attended private masses at the Vatican with the Pope. And then, despite all the hard work, Carl's luck began to change.

During the 1980s CKE went public, opened Carl's Jr. restaurants in Texas, added higher-priced dinners to the menu, and for the first time began to expand by selling franchises. The new menu items and the restaurants in Texas fared poorly. The value of CKE's stock fell. In 1988, Carl and half a dozen members of his family were accused of insider trading by the Securities, and Exchange Commission (SEC). They had sold large amounts of CKE stock right before its price tumbled. Carl vehemently denied the charges and felt humiliated by the publicity surrounding the case. Nevertheless, Carl agreed to a settlement with the SEC - to avoid a long and expensive legal battle, he said - and paid more than half a million dollars in fines.

During the early 1990s, a number of Carl's real estate investments proved unwise. When new subdivisions in Anaheim and the Inland Empire went bankrupt, Carl was saddled with many of their debts. He had allowed real estate developers to use his CKE stock as collateral for their bank loans. He became embroiled in more than two dozen lawsuits. He suddenly owed more than $70 million to various banks. The falling price of CKE stock hampered his ability to repay the loans. In May of 1992, his brother Don - a trusted adviser and the president of CKE - died. The new president tried to increase sales at Carl's Jr. restaurants by purchasing food of a lower quality and cutting prices. The strategy began to drive customers away.

As the chairman of CKE, Carl searched for ways to save his company and payoff his debts. He proposed selling Mexican food at Carl's Jr. restaurants as part of a joint venture with a chain called Green Burrito. But some executives at CKE opposed the plan, arguing that it would benefit Carl much more than the company. Carl had a financial stake in the deal; upon its acceptance by the board of CKE, he would receive a $6 million personal loan from Green Burrito. Carl was outraged that his motives were being questioned and that his business was being run into the ground. CKE now felt like a much different company than the one he'd founded. The new management team had ended the longtime practice of starting every executive meeting with the prayer of St. Francis of Assisi and the pledge of allegiance to the flag. Carl insisted that the Green Burrito plan would work and demanded that the board of directors vote on it. When the board rejected the plan, Carl tried to oust its members. Instead, they ousted him. On March 1, 1993, CKE's board voted five to two to fire Carl N. Karcher. Only Carl and his son Carl Leo opposed the dismissal. Carl felt deeply betrayed. He had known many of the board members for years; they were old friends; he had made them rich. In a statement released after the firing, Carl described the CKE board as "a bunch of turncoats" and called it "one of the saddest days" of his life. At the age of seventy-six, more than five decades after starting the business, Carl N. Karcher was prevented from entering his own office, and new locks were put on the doors.

The headquarters of CKE is still located on the property where the Heinz family once grew oranges. Today there's no smell of citrus in the air, no orange groves in sight. In a town that once had endless rows of orange and lemon trees, stretching far as the eye could see, there's not an acre of them left, not a single acre devoted to commercial citrus growing. Anaheim's population is now about three hundred thousand, roughly thirty times what it was when Carl first arrived. On the comer where Carl's Drive-In Barbeque once stood, there's a strip mall. Near the CKE headquarters on Harbor Boulevard, there's an Exxon station, a discount mattress store, a Shoe City, a Las Vegas Auto Sales store, and an off-ramp of the Riverside Freeway. The CKE building has a modern, Spanish design, with white columns, red brick arches, and dark plate-glass. windows. When I visited recently, it was cool and quiet inside. After passing a life-size wooden statue of St. Francis of Assisi on a stairway landing, I was greeted at the top of the stairs by Carl N. Karcher.

Carl looked like a stylish figure from the big-band era, wearing a brown checked jacket, a white shirt, a brown tie, and jaunty two-tone shoes. He was tall and strong, and seemed in remarkably good shape. The walls of his office were covered with plaques and mementos, with photographs of Carl beside presidents, famous ballplayers, former employees, grandchildren, priests, cardinals, Mikhail Gorbachev, the Pope. Carl proudly removed a framed object from the wall and handed it to me. It was the original receipt for $326, confirming the purchase of his first hot dog cart.

Eight weeks after being locked out of his office in 1993, Carl engineered a takeover of the company. Through a complex series of transactions, a partnership headed by financier William P. Foley II assumed some of Carl's debts, received much of his stock in return, and took control of CKE. Foley became the new chairman of the board. Carl was named chairman emeritus and got his old office back. Almost all of the executives and directors who had opposed him subsequently left the company. The Green Burrito plan was adopted and proved a success. The new management at CKE seemed to have turned the company around, raising the value of its stock. In July of 1997, CKE purchased Hardee's for $327 million, thereby becoming the fourth-largest hamburger chain in the United States, joining· McDonald's, Burger King, and Wendy's at the top. And signs bearing the Carl's Jr. smiling little star started going up across the United States.

Carl seemed amazed by his own life story as he told it. He'd been married to Margaret for sixty years. He'd lived in the same Anaheim house for almost fifty years. He had twenty granddaughters and twenty grandsons. For a man of eighty, he had an impressive memory, quickly rattling off names, dates, and addresses from half a century ago. He exuded the genial optimism and good humor of his old friend Ronald Reagan. "My whole philosophy is - never give up," Carl told me. "The word 'can't' should not exist ... Have a great attitude ... Watch the pennies and the dollars will take care of themselves ... Life is beautiful, life is fantastic, and that is how I feel about every day of my life." Despite CKE's expansion, Carl remained millions of dollars in debt. He'd secured new loans to payoff the old ones. During the worst of his financial troubles, advisers pleaded with him to declare bankruptcy. Carl refused; he'd borrowed more than $8 million from family members and friends, and he would not walk away from his obligations. Every weekday he was attending Mass at six o'clock in the morning and getting to the office by seven. "My goal in the next two years," he said, "is to payoff all my debts."

1 looked out the window and asked how he felt driving through Anaheim today, with its fast food restaurants, subdivisions, and strip malls. "Well, to be frank about it." he said, "I couldn't be happier." Thinking that he'd misunderstood the question, 1 rephrased it, asking if he ever missed the old Anaheim, the ranches and citrus groves.

"No," he answered. "I believe in Progress."

Carl grew up on a farm without running water or electricity. He'd escaped a hard rural life. The view outside his office window was not disturbing to him, I realized. It was a mark of success.

"'When I first met my wife." Carl said, "this road here was gravel ... and now it's blacktop."

Chapter 2: Your Trusted Friends

BEFORE ENTERING the Ray A. Kroc Museum, you have to walk through McStore. Both sit on the ground floor of McDonald's corporate headquarters, located at One McDonald's Plaza in Oak Brook, Illinois. The headquarters building has oval windows and a gray concrete facade - a look that must have seemed space-age when the building opened three decades ago. Now it seems stolid and drab, an architectural relic of the Nixon era. It resembles the American embassy compounds that always used to attract antiwar protesters, student demonstrators, flag burners. The eighty-acre campus of Hamburger University, McDonald's managerial training center, is a short drive from headquarter~. Shuttle buses constantly go back and forth between the campus and McDonald's Plaza, ferrying clean-cut young men and women in khakis who've come to study for their "Degree in Hamburgerology." The course lasts two weeks and trains a few thousand managers, executives, and franchisees each year. Students from out of town stay at the Hyatt on the McDonald's campus. Most of the classes are devoted to personnel issues, teaching lessons in teamwork and employee motivation, promoting "a common McDonald's language" and "a common McDonald's culture." Three flagpoles stand in front of McDonald's Plaza, the heart of the hamburger empire. One flies the Stars and Stripes, another flies the Illinois state flag, and the third flies a bright red flag with golden arches.

You can buy bean-bag McBurglar dolls at McStore, telephones shaped like french fries, ties, clocks, key chains, golf bags and duffel bags, jewelry, baby clothes, lunch boxes, mouse pads, leather jackets, postcards, toy trucks, and much more, all of it bearing the stamp of McDonald's. You can buy T-shirts decorated with a new version of the American flag. The fifty white stars have been replaced by a pair of golden arches.

At the back of McStore, past the footsteps of Ronald McDonald stenciled on the floor, past the shelves of dishes and glassware, a bronze bust of Ray Kroc marks the entrance to his museum. Kroc was the founder of the McDonald's Corporation, and his philosophy of QSC and V - Quality, Service, Cleanliness, and Value - still guide it. The man immortalized in ,bronze is balding and middle-aged, with smooth cheeks and an intense look in his eyes. A glass display case nearby holds plaques, awards, and letters of praise. "One of the highlights of my sixty-first birthday celebration." President Richard Nixon wrote in 1974, "was when Tricia suggested we needed a 'break' on our drive to Palm Springs, and we turned in at McDonald's. I had heard for years from our girls that the 'Big Mac' was really something special, and while I've often credited Mrs. Nixon with making the best hamburgers in the world, we -are both convinced that McDonald's runs a close second ... The next time the cook has a night off we will know where to go for fast service, cheerful hospitality - and probably one of the best food buys in America." Other glass cases contain artifacts of Kroc's life, mementos of his long years of struggle and his twilight as a billionaire. The museum is small and dimly lit, displaying each object with reverence. The day I visited, the place was empty and still. It didn't feel like a traditional museum, where objects are coolly numbered, catalogued, and described. It felt more like a shrine.

Many of the exhibits at the Ray A. Kroc Museum incorporate neat technological tricks. Dioramas appear and then disappear when certain buttons are pushed. The voices of Kroc's friends and coworkers - one of them identified as a McDonald's "vice president of individuality" - boom from speakers at the appropriate cue. Darkened glass cases are suddenly illuminated from within, revealing their contents. An artwork on the wall, when viewed from the left, displays an image of Ray Kroc. Viewed from the right, it shows the letters QSC and V. The museum does not have a life-size, Audio-Animatronic version of McDonald's founder telling jokes and anecdotes. But one wouldn't be out of place. An interactive exhibit called "Talk to Ray" shows video clips of Kroc appearing on the Phil Donahue Show, being interviewed by Tom Snyder, and chatting with Reverend Robert Schuller at the altar of Orange County's Crystal Cathedral. "Talk to Ray" permits the viewer to ask Kroc as many as thirty-six predetermined questions about various subjects; old videos of Kroc supply the answers. The exhibit wasn't working properly the day of my visit. Ray wouldn't take my questions, and so I just listened to him repeating the same speeches.

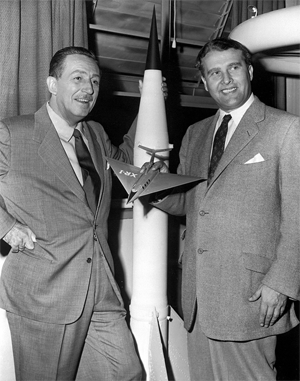

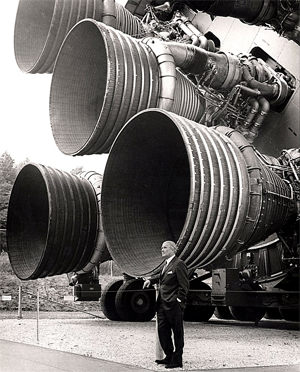

The Disneyesque tone of the museum reflects, among other things, many of the similarities between the McDonald's Corporation and the Walt Disney Company. It also reflects the similar paths of the two men who founded these corporate giants. Ray Kroc and Walt Disney were both from Illinois; they were born a year apart, Disney in 1901, Kroc in 1902; they knew each other as young men, serving together in the same World War I ambulance corps; and they both fled the Midwest and settled in southern California, where they played central roles in the creation of new American industries. The film critic Richard Schickel has described Disney's powerful inner need "to order, control, and keep clean any environment he inhabited." The same could easily be said about Ray Kroc, whose obsession with cleanliness and control became one of the hallmarks of his restaurant chain. Kroc cleaned the holes in his mop wringer with a toothbrush.

Kroc and Disney both dropped out of high school and later added the trappings of formal education to their companies. The training school for Disney's theme-park employees was named Disneyland University. More importantly, the two men shared the same vision of America, the same optimistic faith in technology, the same conservative political views. They were charismatic figures who provided an overall corporate vision and grasped the public mood, relying on others to handle the creative and financial details. Walt Disney neither wrote, nor drew the animated classics that bore his name. Ray Kroc's attempts to add new dishes to McDonald's menu - such as Kolacky, a Bohemian pastry, and the Hulaburger, a sandwich featuring grilled pineapple and cheese - were unsuccessful. Both men, however, knew how to find and motivate the right talent. While Disney was much more famous and achieved success sooner, Kroc may have been more influential. His company inspired more imitators, wielded more power over the American economy - and spawned a mascot even more famous than Mickey Mouse.

Despite all their success as businessmen and entrepreneurs, as cultural figures and advocates for a particular brand of Americanism, perhaps the most significant achievement of these two men lay elsewhere. Walt Disney and Ray Kroc were masterful salesmen. They perfected the art of selling things to children. And their success led many others to aim marketing efforts at kids, turning America's youngest consumers into a demographic group that is now avidly studied, analyzed, and targeted by the world's largest corporations.

Walt and Ray

RAY KROC TOOK THE McDonald brothers' Speedee Service System and spread it nationwide, creating a fast food empire. Although he founded a company that came to symbolize corporate America, Kroc was never a buttoned-down corporate type. He was a former jazz musician who'd played at speakeasies - and at a bordello, on at least one occasion - during Prohibition. He was a charming, funny, and indefatigable traveling salesman who endured many years of disappointment, a Willy Loman who finally managed to hit it big in his early sixties. Kroc grew up in Oak Park, Illinois, not far from Chicago. His father worked for Western Union. As a high school freshman, Ray Kroc discovered the joys of selling while employed at his uncle's soda fountain. "That was where I learned you could influence people with a smile and enthusiasm." Kroc recalled in his autobiography, Grinding It Out, "and sell them a sundae when what they'd come for was a cup of coffee."

Over the years, Kroc sold coffee beans, sheet music, paper cups, Florida real estate, powdered instant beverages called "Malt-a-Plenty" and "Shake-a-Plenty," a gadget that could dispense whipped cream or shaving lather, square ice cream scoops, and a collapsible table-and-bench combination called "Fold-a-Nook" that retreated into the wall like a Murphy bed. The main problem with square scoops of ice cream, he found, was that they slid off the plate when you tried to eat them. Kroc used the same basic technique to sell all these things: he tailored his pitch to fit the buyer's tastes. Despite one setback after another, he kept at it, always convinced that success was just around the corner. "If you believe in it, and you believe in it hard." Kroc later told audiences, "it's impossible to fail. I don't care what it is - you can get it!"

Ray Kroc was selling milk-shake mixers in 1954 when he first visited the new McDonald's Self-Service Restaurant in San Bernardino. The McDonald brothers were two of his best customers. The Multi~ mixer unit that Kroc sold could make five milk shakes at once. He wondered why the McDonald brothers needed eight of the machines. Kroc had visited a lot of restaurant kitchens, out on the road, demonstrating the Multimixer - and had never seen anything like the McDonald's Speedee Service System. "When I saw it." he later wrote, "I felt like some latter-day Newton who'd just had an Idaho potato caromed off his skull." He looked at the restaurant "through the eyes of a salesman" and envisioned putting a McDonald's at busy intersections all across the land.

Richard and "Mac" McDonald were less ambitious. They were clearing $100,000 a year in profits from the restaurant, a huge sum in those days. They already owned a big house and three Cadillacs. They didn't like to travel. They'd recently refused an offer from the Carnation Milk Company, which thought that opening more McDonald's would increase the sales of milk shakes. Nevertheless, Kroc convinced the brothers to sell him the right to franchise McDonald's nationwide. The two could stay at home, while Kroc traveled the country, making them even richer. A deal was signed. Years later Richard McDonald described his first memory of Kroc, a moment that would soon lead to the birth of the world's biggest restaurant chain: "This little fellow comes in, with a high voice, and says, 'hi.'"

After finalizing the agreement with the McDonald brothers, Kroc sent a letter to Walt Disney. In 1917 the two men had both lied about their ages to join the Red Cross and see battle in Europe. A long time had clearly passed since their last conversation. "Dear Walt," the letter said. "I feel somewhat presumptuous addressing you in this way yet I feel sure you would not want me to address you any other way. My name is Ray A. Kroc ... I look over the Company A picture we had taken at Sound Beach, Conn., many times and recall a lot of pleasant memories." After the warm-up came the pitch: "I have very recently taken over the national franchise of the McDonald's system. I would like to inquire if there may be an opportunity for a McDonald's in your Disneyland Development."

Walt Disney sent Kroc a cordial reply and forwarded his proposal to an executive in charge of the theme park's concessions. Disneyland was still under construction, its opening was eagerly awaited by millions of American children, and Kroc may have had high hopes. According to one account, Disney's company asked Kroc to raise the price of McDonald's french fries from ten cents to fifteen cents; Disney would keep the extra nickel as payment for granting the concession; and the story ends with Ray Kroc refusing to gouge his loyal customers. The account seems highly unlikely, a belated effort by someone at McDonald's to put the best spin on a sales pitch that went nowhere. When Disneyland opened in July of 1955 - an event that Ronald Reagan cohosted for ABC - it had food stands run by Welch's, Stouffer's, and Aunt Jemima's, but no McDonald's. Kroc was not yet in their league. His recollection of Walt Disney as a young man, briefly mentioned in Grinding It Out, is not entirely flattering. "He was regarded as a strange duck," Kroc wrote of Disney, "because whenever we had time off and went out on the town to chase girls, he stayed in camp drawing pictures."

Whatever feelings existed between the two men, Walt Disney proved in many respects to be a role model for Ray Kroc. Disney's success had come much more quickly. At the age of twenty-one he'd left the Midwest and opened his own movie studio in Los Angeles. He was famous before turning thirty. In The Magic Kingdom (1997) Steven Watts describes Walt Disney's efforts to apply the techniques of mass production to Hollywood moviemaking. He greatly admired Henry Ford and introduced an assembly line and a rigorous division of labor at the Disney Studio, which was soon depicted as a "fun factory." Instead of drawing entire scenes, artists were given narrowly defined tasks, meticulously sketching and inking Disney characters while supervisors watched them and timed how long it took them to complete each cel. During the 1930s the production system at the studio was organized to function like that of an automobile plant. "Hundreds of young people were being trained and fitted," Disney explained, "into a machine for the manufacture of entertainment."

The working conditions at Disney's factory, however, were not always fun. In 1941 hundreds of Disney animators went on strike, expressing support for the Screen Cartoonists Guild. The other major cartoon studios in Hollywood had already signed agreements with the union. Disney's father was an ardent socialist, and Disney's films had long expressed a populist celebration of the common man. But Walt's response to the strike betrayed a different political sensibility. He fired employees who were sympathetic to the union, allowed private guards to rough up workers on the picket line, tried to impose a phony company union, brought in an organized crime figure from Chicago to rig a settlement, and placed a full-page ad in Variety that accused leaders of the Screen Cartoonists Guild of being Communists. The strike finally ended when Disney acceded to the union's demands. The experience left him feeling embittered. Convinced that Communist agents had been responsible for his troubles, Disney subsequently appeared as a friendly witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee, served as a secret informer for the FBI, and strongly supported the Hollywood blacklist. During the height of labor tension at his studio, Disney had made a speech to a group of employees, arguing that the solution to their problems rested not with a labor union, but with a good day's work. "Don't forget this," Disney told them, "it's the law of the universe that the strong shall survive and the weak must fall by the way, and I don't give a damn what idealistic plan is cooked up, nothing can change that."

Decades later, Ray Kroc used similar language to outline his own political philosophy. Kroc's years on the road as a traveling salesman - carrying his own order forms and sample books, knocking on doors, facing each new customer alone, and having countless doors slammed in his face - no doubt influenced his view of humanity. "Look, it is ridiculous to call this an industry," Kroc told a reporter in 1972, dismissing any high-minded analysis of the fast food business. "This is not. This is rat eat rat, dog eat dog. I'll kill 'em, and I'm going to kill 'em before they kill me. You're talking about the American way of survival of the fittest."

While Disney backed right-wing groups and produced campaign ads for the Republican Party, Kroc remained aloof from electoral politics - with one notable exception. In 1972, Kroc gave $250,000 to President Nixon's reelection campaign, breaking the gift into smaller donations, funneling the money through various state and local Republican committees. Nixon had every reason to like McDonald's, long before tasting one of its hamburgers. Kroc had never met the president; the gift did not stem from any personal friendship or fondness. That year the fast food industry was lobbying Congress and the White House to pass new legislation - known as the "McDonald's bill" - that would allow employers to pay sixteen- and seventeen- year-old kids wages 20 percent lower than the minimum wage. Around the time of Kroc's $250,000 donation, McDonald's crew members earned about $1.60 an hour. The subminimum wage proposal would reduce some wages to $1.28 an hour.

The Nixon administration supported the McDonald's bill and permitted McDonald's to raise the price of its Quarter Pounders, despite the mandatory wage and price controls restricting other fast food chains. The size and the timing of Kroc's political contribution sparked Democratic accusations of influence peddling. Outraged by the charges, Kroc later called his critics "sons of bitches." The uproar left him wary of backing political candidates. Nevertheless, Kroc retained a soft spot for Calvin Coolidge, whose thoughts on hard work and self-reliance were prominently displayed at McDonald's corporate headquarters.

Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal [EXCERPT]

by Eric Schlosser

© 2002, 2001 by Eric Schlosser

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Chapter 1: The American Way

The Founding Fathers

CARL N. KARCHER is one of the fast food industry's pioneers. His career extends from the industry's modest origins to its current hamburger hegemony. His life seems at once to be a tale by Horatio Alger, a fulfillment of the American dream, and a warning about unintended consequences. It is a fast food parable about how the industry started and where it can lead. At the heart of the story is southern California, whose cities became prototypes for the rest of the nation, whose love of the automobile changed what America looks like and what Americans eat.

Carl was born in 1917 on a farm near Upper Sandusky, Ohio. His father was a sharecropper who moved the family to new land every few years .. The Karchers were German-American, industrious, and devoutly Catholic. Carl had six brothers and a sister. "The harder you work." their father always told them, "the luckier you become." Carl dropped out of school after the eighth grade and worked twelve to fourteen hours a day on the farm, harvesting with a team of horses, baling hay, milking and feeding the cows. In 1937, Ben Karcher, one of Carl's uncles, offered him a job in Anaheim, California. After thinking long and hard and consulting with his parents, Carl decided to go west He was twenty years old and six-foot-four, a big strong farm boy. He had never set foot outside of northern Ohio. The decision to leave home felt momentous, and the drive to California took a week. When he arrived in Anaheim - and saw the palm trees and orange groves, and smelled the citrus in the air - Carl said to himself, "This is heaven."

Anaheim was a small town in those days, surrounded by ranches and farms. It was located in the heart of southern California's citrus belt, an area that produced almost all of the state's oranges, lemons, and tangerines. Orange County and neighboring Los Angeles County were the leading agricultural counties in the United States, growing fruits, nuts, vegetables, and flowers on land that only a generation earlier had been a desert covered in sagebrush and cactus. Massive irrigation projects, built with public money to improve private land, brought water from hundreds of miles away. The Anaheim area alone boasted about 70,000 acres of Valencia oranges, as well as lemon groves and walnut groves. Small ranches and dairy farms dotted the land, and sunflowers lined the back roads. Anaheim had been settled in the late nineteenth century by German immigrants hoping to create a local wine industry and by a group of Polish expatriates trying to establish a back-to-the-land artistic community. The wineries flourished for three decades; the art colony collapsed within a few months. After World War I, the heavily German character of Anaheim gave way to the influence of newer arrivals from the Midwest, who tended to be Protestant and conservative and evangelical about their faith. Reverend Leon L. Myers - pastor of the Anaheim Christian Church and founder of the local Men's Bible Club - turned the Ku Klux Klan into one of the most powerful organizations in town. During the early 1920s, the Klan ran Anaheim's leading daily newspaper, controlled the city government for a year, and posted signs on the outskirts of the City greeting newcomers with the acronym "KIGY" (Klansmen I Greet You).

Carl's uncle Ben owned Karcher's Feed and Seed Store, right in the middle of downtown Anaheim. Carl worked there seventy-six hours a week, selling goods to local farmers for their chickens, cattle, and hogs. During Sunday services at St. Boniface Catholic Church, Carl spotted an attractive young woman named Margaret Heinz sitting in a nearby pew. He later asked her out for ice cream, and the two began. dating. Carl became a frequent visitor to the Heinz farm on North Palm Street. It had ten acres of orange trees and a Spanish-style house where Margaret, her parents, her seven brothers, and her seven sisters lived. The place seemed magical. In the social hierarchy of California's farmers, orange growers stood at the very top; their homes were set amid fragrant evergreen trees that produced a lucrative income. As a young boy in Ohio, Carl had been thrilled on Christmas mornings to receive a single orange as a gift from Santa. Now oranges seemed to be everywhere.

Margaret worked as a secretary at a law firm downtown. From her office window on the fourth floor, she could watch Carl grinding feed outside his uncle's store. After briefly returning to Ohio, Carl went to work for the Armstrong Bakery in Los Angeles. The job soon paid $.24 a week, $6 more than he'd earned at the feed store - and enough to start a family. Carl and Margaret were married in 1939 and had their first child within a year.

Carl drove a truck for the bakery, delivering bread to restaurants and markets in west L.A. He was amazed by the number of hot dog stands that were opening and by the number of buns they went through every week. When Carl heard that a hotdog cart was for sale - on Florence Avenue across from the Goodyear factory - he decided to buy it. Margaret strongly opposed the idea, wondering where he'd find the money. He borrowed $311 from the Bank of America, using his car as collateral for the loan, and persuaded his wife to give him $15 in cash from her purse. ''I'm in business for myself now," Carl thought, after buying the cart, "I'm on my way." He kept his job at the bakery and hired two young men to work the cart during the hours he was delivering bread. They sold hot dogs, chili dogs, and tamales for a dime each, soda for a nickel. Five months after Carl bought the cart, the United States entered World War II, and the Goodyear plant became very busy. Soon he had enough money to buy a second hot dog cart, which Margaret often ran by herself, selling food and counting change while their daughter slept nearby in the car.

Southern California had recently given birth to an entirely new lifestyle -- and a new way of eating. Both revolved around cars. The cities back East had been built in the railway era, with central business districts linked to outlying suburbs by commuter train and trolley. But the tremendous growth of Los Angeles occurred at a time when automobiles were finally affordable. Between 1920 and 1940, the population of southern California nearly tripled, as about 2 million people arrived from across the United States. While cities in the East expanded through immigration and became more diverse, Los Angeles became more homogenous and white. The city was inundated with middle-class arrivals from the Midwest, especially in the years leading up to the Great Depression. Invalids, retirees, and small businessmen were drawn to southern California by real estate ads promising a warm climate and a good life. It was the first large-scale migration conducted mainly by car. Los Angeles soon became unlike any other city the world had ever seen, sprawling and horizontal, a thoroughly suburban metropolis of detached homes - a glimpse of the future, molded by the automobile. About 80 percent of the population had been born elsewhere; about half had rolled into town during the previous five years. Restlessness, impermanence, and speed were embedded in the culture that soon emerged there, along with an openness to anything new. Other cities were being transformed by car ownership, but none was so profoundly altered. By 1940, there were about a million cars in Los Angeles, more cars than in forty-one states.

The automobile offered drivers a feeling of independence and control. Daily travel was freed from the hassles of rail schedules, the needs of other passengers, and the location of trolley stops. More importantly, driving seemed to cost much less than using public transport - an illusion created by the fact that the price of a new car did not include the price of building new roads. Lobbyists from the oil, tire, and automobile industries, among others, had persuaded state and federal agencies to assume that fundamental expense. Had the big auto companies been required to pay for the roads - in the same way that trolley companies had to lay and maintain track - the landscape of the American West would look quite different today.

The automobile industry, however, was not content simply to reap the benefits of government-subsidized road construction. It was determined to wipe out railway competition by whatever means necessary. In the late 1920s, General Motors secretly began to purchase trolley systems throughout the United States, using a number of front corporations. Trolley systems in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Montgomery, Alabama, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and El Paso, Texas, in Baltimore, Chicago, New York City, and Los Angeles - more than one hundred trolley systems in all- were purchased by GM and then completely dismantled, their tracks ripped up, their overhead wires torn down. The trolley companies were turned into bus lines, and the new buses were manufactured by GM.

General Motors eventually persuaded other companies that benefited from road building to help pay for the costly takeover of America's trolleys. In 1947, GM and a number of its allies in the scheme were indicted on federal antitrust charges. Two years later, the workings of the conspiracy, and its underlying intentions, were. exposed during a trial in Chicago. GM, Mack Truck, Firestone, and Standard Oil of California were all found guilty on one of the two counts by the federal jury. The investigative journalist Jonathan Kwitny later argued that the case was "a fine example of what can happen when important matters of public policy are abandoned by government to the self-interest of corporations." Judge William J. Campbell was not so outraged. As punishment, he ordered GM and the other companies to pay a fine of $5,000 each. The executives who had secretly plotted and carried out the destruction of America's light rail network were fined $1 each. And the postwar reign of the automobile proceeded without much further challenge.

The nation's car culture reached its height in southern California, inspiring innovations such as the world's first motel and the first drive-in bank. A new form of eating place emerged. "People with cars are so lazy they don't want to get out of them to eat!" said Jesse G. Kirby, the founder of an early drive-in restaurant chain. Kirby's first "Pig Stand" was in Texas, but the chain soon thrived in Los Angeles, alongside countless other food stands offering "curb service." In the rest of the United States, drive-ins were usually a seasonal phenomenon, closing at the end of every summer. In southern California, it felt like summer all year long, the drive-ins never closed, and a whole new industry was born.

The southern California drive-in restaurants of the early 1940s tended to be gaudy and round, topped with pylons, towers, and flashing signs. They were "circular-meccas of neon," in the words of drive-in historian Michael Witzel, designed to be easily spotted from the road. The triumph of the automobile encouraged not only a geographic separation between buildings, but also a manmade landscape that was loud and bold. Architecture could no longer afford to be subtle; it had to catch the eye of motorists traveling at high speed. The new drive-ins competed for attention, using all kinds of visual lures, decorating their buildings in bright colors and dressing their waitresses in various costumes. Known as "carhops," the waitresses - who carried trays of food to patrons in parked cars - often wore short skirts and dressed up like cowgirls, majorettes, Scottish lasses in kilts. They were likely to be attractive, often received no hourly wages, and earned their money through tips and a small commission on every item they sold. The carhops had a strong economic incentive to be friendly to their customers, and drive-in restaurants quickly became popular hangouts for teenage boys. The drive-ins fit perfectly with the youth culture of Los Angeles. They were something genuinely new and different, they offered a combination of girls and cars and late-night food, and before long they beckoned from intersections all over town.

Speedee Service

BY THE END OF 1944, Carl Karcher owned four hot dog carts in Los Angeles. In addition to running the carts, he still worked full-time for the Armstrong Bakery. When a restaurant across the street from the Heinz farm went on sale, Carl decided to buy it. He quit the bakery, bought the restaurant, fixed it up, and spent a few weeks learning how to cook. On January 16, 1945, his twenty-eighth birthday, Carl's Drive-In Barbeque opened its doors. The restaurant was small, rectangular, and unexceptional, with red tiles on the roof. Its only hint of flamboyance was a five-pointed star atop the neon sign in the parking lot. During business hours, Carl did the cooking, Margaret worked behind the cash register, and carhops served most of the food. After closing time, Carl stayed late into the night, cleaning the bathrooms and mopping the floors. Once a week, he prepared the "special sauce" for his hamburgers, making it in huge kettles on the back porch of his house, stirring it with a stick and then pouring it into one-gallon jugs.

After World War II, business soared at Carl's Drive-In Barbeque, along with the economy of southern California. The oil business and the film business had thrived in Los Angeles during the 1920s and 1930s. But it was World War II that transformed southern California into the most important economic region in the West. The war's effect on the state, in the words of historian Carey McWilliams, was a "fabulous boom." Between 1940 and 1945, the federal government spent . nearly $20 billion in California, mainly in and around Los Angeles, building airplane factories and steel mills, military bases and port facilities. During those six years, federal spending was responsible for nearly half of the personal income in southern California. By the end of World War II, Los Angeles was the second-largest manufacturing center in America, with an industrial output surpassed only by that of Detroit. While Hollywood garnered most of the headlines, defense spending remained the focus of the local economy for the next two decades, providing about one-third of its jobs.

The new prosperity enabled Carl and Margaret to buy a house five blocks away from their restaurant. They added more rooms as the family grew to include twelve children: nine girls and three boys. In the early 1950s Anaheim began to feel much less rural and remote. Walt Disney bought 160 acres of orange groves just a few miles from Carl's Drive-In Barbeque, chopped down the trees, and started to build Disneyland. In the neighboring town of Garden Grove, the Reverend Robert Schuller founded the nation's first Drive-in Church, preaching on Sunday mornings at a drive-in movie theater, spreading the Gospel through the little speakers at each parking space, attracting large crowds with the slogan "Worship as you are ... in the family car." The city of Anaheim started to recruit defense contractors, eventually persuading Northrop, Boeing, and North American Aviation to build factories there. Anaheim soon became the fastest-growing city in the nation's fastest-gr-owing state. Carl's Drive-In Barbeque thrived, and Carl thought its future was secure. And then he heard about a restaurant in the "Inland Empire." sixty miles east of Los Angeles, that was selling high-quality hamburgers for 15 cents each - 20 cents less than what Carl charged. He drove to E Street in San Bernardino and saw the shape of things to come. Dozens of people were standing in line to buy bags of "McDonald's Famous Hamburgers."

Richard and Maurice McDonald had left New Hampshire for southern California at the start of the Depression, hoping to find jobs in Hollywood. They worked as set builders on the Columbia Film Studios back lot, saved their money, and bought a movie theater in Glendale. The theater was not a success. In 1937 they opened a drive-in restaurant in Pasadena, trying to cash in on the new craze, hiring three carhops and selling mainly hot dogs. A few years later they moved to a larger building on E Street in San Bernardino and opened ,the McDonald Brothers Burger Bar Drive-In. The new restaurant was located near a high school, employed twenty carhops, and promptly made the brothers rich. Richard and "Mac" McDonald bought one of the largest houses in San Bernardino, a hillside mansion with a tennis court and a pool.

By the end of the 1940s the McDonald brothers had grown dissatisfied with the drive-in business. They were tired of constantly looking for new carhops and short-order cooks - who were in great demand - as the old ones left for higher-paying jobs elsewhere. They were tired of replacing the dishes, glassware, and silverware their teenage customers constantly broke or ripped off. And they were tired of their teenage customers. The brothers thought about selling the restaurant. Instead, they tried something new.

The McDonalds fired all their carhops in 1948, closed 'their restaurant, installed larger grills, and reopened three months later with a radically new method of preparing food. It was designed to increase .the speed, lower prices, and raise the volume of sales. The brothers eliminated almost two-thirds of the items on their old menu. They got rid of everything that had to be eaten with a knife, spoon, or fork. The only sandwiches now sold were hamburgers or cheeseburgers. The brothers got rid of their dishes and glassware, replacing them with paper cups, paper bags, and paper plates. They divided the food preparation into separate tasks performed by different workers. To fill a typical order, one person grilled the. hamburger; another "dressed" and wrapped it; another prepared the milk shake; another made the fries; and another worked the counter. For the first time, the guiding principles of a factory assembly line were applied to a commercial kitchen. The new division of labor meant that a worker only had to be taught how to perform one task. Skilled and expensive short-order cooks were no longer necessary. All of the burgers were sold with the same condiments: ketchup, onions, mustard, and two pickles. No substitutions were allowed. The McDonald brothers' Speedee Service System revolutionized the restaurant business. An ad of theirs seeking franchisees later spelled out the benefits of the system: "Imagine -- No Carhops - No Waitresses - No Dishwashers "- No Bus Boys - The McDonald's System is Self-Service!"

Richard McDonald designed a new building for the restaurant, hoping to make it easy to spot from the road. Though untrained as an architect, he came up with a design that was simple, memorable, and archetypal. On two sides of the roof he put golden arches, lit by neon at night, that from a distance formed the letter M. The building effortlessly fused advertising with architecture and spawned one of the most famous corporate logos in the world.

The Speedee Service System, however, got off to a rocky start. Customers pulled up to the restaurant and honked their horns, wondering what had happened to the carhops, still expecting to be served. People were not yet accustomed to waiting in line and getting their own food. Within a few weeks, however, the new system gained acceptance, as word spread about the low prices and good hamburgers. The McDonald brothers now aimed for a much broader clientele. They . employed only young men, convinced that female workers would attract teenage boys to the restaurant and drive away other customers. Families soon lined up to eat at McDonald's. Company historian John F. Love explained the lasting significance of McDonald's new self-service system: "Working-class families could finally afford to feed their kids restaurant food."

San Bernardino at the time was an ideal setting for all sorts of cultural experimentation. The town was an odd melting-pot of agriculture and industry located 'on the periphery of the southern California boom, a place that felt out on the edge. Nicknamed "San Berdoo," it was full of citrus' groves, but sat next door to the smokestacks and steel mills of Fontana. San Bernardino had just sixty thousand inhabitants;· but millions of people passed through there every year. It was the last stop on Route 66, end of the line for truckers, tourists, and migrants from the East. Its main street was jammed with drive-ins and cheap motels. The same year the McDonald brothers opened their new self-service restaurant, a group of World War II veterans in San Berdoo, alienated by the dullness of civilian life, formed a local motorcycle club, borrowing the nickname of the U.S. Army's Eleventh Airborne Division: "Hell's Angels." The same town that gave the world the golden arches also gave it a biker gang that stood for a totally antithetical set of values. The Hell's Angels flaunted their dirtiness, celebrated disorder, terrified families and small children instead of trying to sell them burgers, took drugs, sold drugs, and injected into American pop culture an anger and a darkness and a fashion statement - T-shirts and tom jeans, black leather jackets and boots, long hair, facial hair, swastikas, silver skull rings and other satanic trinkets, earrings, nose rings, body piercings, and tattoos - that would influence a long line of rebels from Marlon Brando to Marilyn Manson. The Hell's Angels were the anti-McDonald's, the opposite of clean and cheery. They didn't care if you had a nice day, and yet were as deeply American in their own way as any purveyors of Speedee Service. San Bernardino in 1948 supplied the nation with a new yin and yang, new models of conformity and rebellion. "They get angry when they read about how filthy they are," Hunter Thompson later wrote of the Hell's Angels, "but instead of shoplifting some deodorant, they strive to become even filthier."

Burgerville USA