Re: Freda Bedi, by Wikipedia

15. CONVERT TO COMPASSION: Allan Bennett, Excerpt from Theravada Buddhism and the British Encounter: Religious, Missionary and Colonial Experience in Nineteenth Century Sri Lanka

by Elizabeth J. Harris

2006

© 2006 Elizabeth J. Harris

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

15. CONVERT TO COMPASSION: Allan Bennett

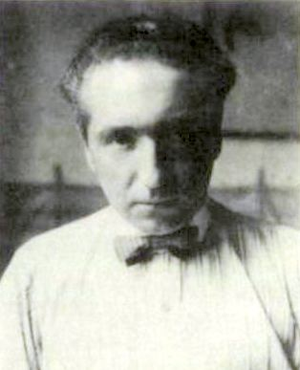

This was Clifford Bax’s impression of Allan Bennett (1872–1923) in 1918. Bennett was then a lay person, and he was sick, incapacitated by asthma for weeks at a time. But ten years earlier, as the venerable Ananda Metteyya, he had led the first Buddhist mission to England, from Myanmar. The Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland had been formed in preparation.

Allan Bennett’s life, after his discovery of Buddhism, was inspired by the conviction that the West needed Buddhism and had only to understand its message to embrace it. He laid down a threefold agenda in the first edition of the journal he edited from Myanmar. First, he imagined a West that was losing both religious and moral awareness:

‘No’, was his answer and he backed this up with reference to the West’s ‘crowded taverns’, ‘overflowing gaols’, ‘sad asylums’ and its neglect of mental culture (Bennett 1903a: 13). Second, he rejected three ‘misconceptions’ about Buddhism: that it was heathen and idolatrous; that it was connected with ‘miracle-mongering and esotericism’; that it was ‘a backboneless, apathetic, pessimistic manner of philosophy’ (Bennett 1903a: 25). Third, he put across what he believed Buddhism to be: rational and optimistic. Later he would contest, in addition, two ‘onlys’: that Buddhism was only a rational philosophy; and that the Buddha was only a remarkable and enlightened teacher.

To this apologetic task, Allan Bennett brought a poetic imagination, a scientific mind and a deep concern for justice and peace. And in Allan Bennett, compassion moves centre stage as Buddhism’s sine qua non.

Bennett’s life

In piecing together the biography of Allan Bennett, I am heavily indebted to the writings of two of his closest friends, Aleister Crowley and Dr Cassius Pereira.1 Bennett was born in London. His father, a civil and electrical engineer, died when he was young. Pereira claimed he was adopted by a Mr McGregor and kept this name until McGregor died, a fact repeated to me by the venerable Balangoda Ananda Metteyya (Harris 1998: 4). Yet, it is possible that his mother was still in contact, since Crowley refers to him being brought up by his mother as a strict Catholic (Symonds and Grant 1989: 180). This might explain his later opposition to any form of religion that placed more importance on ‘sin’ than love. After an education in Bath, he trained as an analytical chemist and was eventually employed by a Dr Bernard Dyer, a public analyst and consulting chemist then based in London (Grant 1972: 82).

The limited information available suggests that Bennett was a sensitive and serious young man, who became alienated from Christianity both because it seemed incompatible with science, and because he could not reconcile the concept of a God of love with the suffering he saw and experienced. The asthma that plagued his life seems to have begun in childhood. It prevented him from holding down a permanent job, meaning that he was at times desperately poor and ill. ‘Allan never knew joy,’ Crowley wrote, ‘he disdained and distrusted pleasure from the womb’ (Symonds and Grant 1989: 234).

Bennett did not, however, distrust the search for truth and goodness. And his two keys to this were science and religion. His religious quest was experimental, even daring. After rejecting Roman Catholicism, he turned first to Asia. At the age of 18, The Light of Asia influenced him, but it was part of a larger exploration that embraced Hindu literature, yogic forms of breath control and meditation (Grant 1972: 85; Symonds and Grant 1989: 246–7) and eventually Western esoteric mysticism.

In 1894, Bennett joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, founded in 1889 by William Wynn Westcott and Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers, taking the name Iehi Aour, Hebrew for ‘let there be light’. He rose to the top rapidly, known for his psychic powers.2 Most of the available information about Bennett at this point comes through Crowley, who joined the Order in 1898. He speaks of Bennett as tall but stooped because of illness, with ‘a shock of wild, black hair’ and a noble head, adding, ‘I did not fully realize the colossal stature of that sacred spirit; but I was instantly aware that this man could teach me more in a month than anyone else in five years’ (Symonds and Grant 1989: 181).

The next stage in Bennett’s life began when he travelled to Sri Lanka in 1900 for health reasons, Crowley paying his passage in the hope that this would save his life and spread Western esotericism in the East. But Bennett was more interested in exploring the local, learning yoga, for instance, from P. Ramanathan, the Solicitor-General.3 According to Pereira, he also went to Kamburugamuwa and studied Pali under an elder Sinhala monk. By the end of six months, Pereira claimed, he could converse in it fluently, adding, ‘Such was the brilliance of his intellect’ (Pereira 1923: 6).

Sri Lanka was a turning point for Bennett. His asthma improved. He gave up the cycle of drugs he had found necessary in England.4 Most of all, he found the answer to his religious quest in Theravada Buddhism, rejecting his former eclectic experimentation with psychic and esoteric power (Symonds and Grant 1989: 237, 249). By the time he addressed the Hope Lodge of the Theosophical Society, Colombo, in July 1901, he had probably decided that he would become a Buddhist monk.

Bennett was ordained a novice in Akyab, Arakan, Myanmar on 12 December 1901, taking the name Ananda Maitreya, which he later changed to the Pali, Metteyya. Higher ordination followed on 21 May 1902, under the venerable Sheve Bya Sayadaw. When Crowley next visited Myanmar, he was in a monastery just outside Rangoon. From there, on 13 March 1903, he inaugurated the Buddhasasana Samagama, an international Buddhist society that aimed at the global networking of Buddhists.5 It soon had official representatives in Austria, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, China, Germany, Italy, America and England. In the same year, he launched Buddhism – An Illustrated Quarterly Review, which, by 1904, was being sent free to between 500 and 600 libraries in Europe.6

The first Buddhist mission to England

Ananda Metteyya arrived in England on 23 April 1908 to an eager welcome from the Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland, formed the previous November. He remained until 2 October, ‘the time allotted to the Mission,’ according to Christmas Humphreys (Humphreys 1968: 7). Although Ananda Metteyya told a Rangoon paper that he was highly gratified with the visit, it was a qualified success. On the positive side there was his grace and dignity, his ‘pleasing voice and beautiful enunciation’ (Humphreys 1968: 6), his knowledge of Buddhism, the scholars he gathered around him through ‘correspondence and constant interviews’ (Humphreys 1968: 6) and his engaging manner in private conversation (Humphreys 1972: 133). Yet, ensuring he could follow his monastic discipline stretched his supporters to the limit (Bell 2000). His orange robes in the streets caused laughter, and his public speaking style was uncharismatic, since he would avoid eye contact, keeping his eye on a prepared script. Nevertheless, the Buddhist Society’s journal, The Buddhist Review (BR), could say in 1909 that he left behind him, ‘golden opinions and the friendship and respect of all who had the privilege of meeting him’.7

Ananda Metteyya hoped he would return to England within three years to establish a permanent Buddhist community in the West. The hope died. One reason for this was his health, which failed rapidly on his return to Myanmar. Pereira records that he underwent two operations and reluctantly agreed to leave the Order on medical advice (Pereira 1923: 6).8 In 1914, Burmese friends sent him to England where he intended to sail from Liverpool to America to stay with his sister, but the ship’s doctor refused him passage.

From this point onwards, Allan Bennett’s story was a sad one. A doctor who was a member of the Liverpool Branch of the Buddhist Society took him in, but the financial and emotional burden of this proved too great. In 1916, an anonymous group of well-wishers appealed for money through the Buddhist Society to save Bennett from being placed ‘in some institution supported by public charity’.9

Help came, from overseas as well as Britain, and Bennett’s health rallied. In the winter of 1917–1918, he gave a series of papers to a private audience in Clifford Bax’s studio. Then, on Vesak Day (May) 1918, Bennett gave to the Buddhist Society what Christmas Humphreys called ‘a “fighting speech” which aroused the listening members to fresh enthusiasm’ (Humphreys 1968: 14).

According to one account, Bennett moved to London in 1920 (Mullen 1989: 92). Although he was incapacitated for weeks at a time, he took over the editorship of the BR from the Sri Lankan scholar, D.B. Jayatileka. The January 1922 edition was the last he edited and indeed the last that was published. He died on 9 March 1923. A Buddhist funeral service was prepared by Francis Payne, a prominent Buddhist convert from the 1908 mission.10

I will use three main sources to explore Ananda Metteyya/Allan Bennett’s representation of Buddhism. The Religion of Burma and other Papers published by the Theosophical Publishing House of India in 1929 contains talks given in Myanmar, belonging to the first decade of the twentieth century. The Wisdom of the Aryas, published in London in 1923, the year of his death, consists of the lectures delivered in 1917–1918 plus one additional paper on rebirth. Finally, his writing in the journal Buddhism is most important.

A suffering world

Ananda Metteyya’s understanding of Buddhism began with awareness of suffering (dukkha). Speaking of the progression of thought in one who attempted to look at the world with ‘the cold, clear light of Reason’, he wrote:

Ananda Metteyya’s conclusion was that it was sacrifice that pervaded existence, not joy. His phrases were vivid: ‘Life ever offered up to Life on its own altar’ (Bennett 1923: 3); nature as ‘a slaughter-house wherein no thought of pity ever enters’ (Bennett 1929: 156); ‘Life alone can feed life’ (Bennett 1929: 170). And in ‘the Vast Emptiness’ of the cosmos there was a, ‘a horror of living past conceiving, full of the Pain of Being, darkened by Not-Understanding; thrilling with Hope in youth, and ever aging in Despair!’ (Bennett 1929: 142–3).

Part of Buddhism’s attraction for Ananda Metteyya was that it looked the truth of suffering in the eye (Bennett 1923: xiv). ‘To dare to look on life as it really is’ was the first step along the religious path (Bennett 1929: 221). It was into this suffering world that the Buddha came as liberator.

The Buddha

At a time when most Westerners were stressing the humanity and historicity of the Buddha, Ananda Metteyya was pointing out that no comparison with ordinary humanity was possible:

It was compassionate self-sacrifice in innumerable lives preceding Buddhahood that qualified the Buddha for this, according to Ananda Metteyya, a sacrifice, ‘so great, so utterly beyond our ken, that we can only try to dimly represent it in terms of human life and thought and action’ (Bennett 1923: 16–17).

Acts of devotion to the Buddha, therefore, did not seem unnatural or irrational to Ananda Metteyya, and in this he knew he differed from some Western Buddhists (Bennett 1929: 341–2). When, in Myanmar, he came across an atmosphere of worship so intense that the air seemed to vibrate with a ‘palpable’ potency, an ‘immediate’ presence (Bennett 1923: 7), his reaction was not disdain but wonder. His disdain was for those who denied that the Buddha could be present in the lives of the people:

The devotion of dependence and blind faith, however, he did criticize, as something akin to childhood. It could lead to heavenly rebirth but not to the ultimate goal (Bennett 1929: 370). There was a higher devotion connected with questioning, investigation and recognition: ‘the devotion that comes in the train of Understanding’ . . . ‘when we attain some glimpse of the tremendous meaning of the Love that has for us resulted in the knowledge of the Law we have’ (Bennett 1929: 320). Yet, ultimately:

What the Buddha taught

Ananda Metteyya would have agreed with the theosophists that the key to the Buddhist view of the world, as taught by the Buddha, was Law, as shown in the Law of cause and effect (paticcasamuppada). But he did not see this as the exoteric component of an esoteric vision, but as making the need for the esoteric, obsolete. With the Law of Cause and Effect as shown in the Four Noble Truths (Bennett 1929: 320, 356), the need for esoteric knowledge, the goal of his youthful experimentation, was wiped out.

Ananda Metteyya could graphically describe dukkha, the First Noble Truth. His representation of the cause of dukkha varied. Sometimes he stressed tajha, craving, and appealed to science. Take the amoebae, he suggested, and dukkha can be seen. Amoebae move only when irritated, when feeling aversion. When still, they are at peace. From this, he continued, all other animal reactions have developed. By the time human aversion is reached, a thousand complex suffering-creating cravings have arisen. Yet, he preferred to cite avijja, ‘ignorance’, rather than tajha, most particularly ignorance of anatta, non-self.

Without knowledge of Buddhist ideas, he wrote, it is almost impossible to become aware ‘how much every mode of expression of western thought involves the assumption of the existence of a Self’ (Bennett 1908b: 279). The would-be Buddhist, therefore, had to learn:

There are echoes of Arnold and Rhys Davids here, but Ananda Metteyya went further. The message of the Buddha, he believed, was that dukkha was inseparably linked with belief in self. The realization of the falsity of the soul concept was, ‘the darkest hour in all the evolution of a man’. But it was ‘the darkest hour which goes before the dawn’ (Bennett 1904a: 369–70).

Undergirding this in Ananda Metteyya’s vision was cosmic interconnectedness, raised to the status of scientific truth. All life was one. There was ‘One Life’. The simile he most frequently used was of a wave:

Arnold had stressed the interdependence of all. Ananda Metteyya again took the imagery further. All animal and plant life was so fused together that every action, movement or thought affected the whole, rendering meaningless any distinction between good for self and good for others. Non-recognition of this was the main cause of suffering.

When the sense of self was blown out, when the ‘One Life’ was recognized, according to Ananda Metteyya’s reading of the Buddha’s teaching, something ‘immeasurable and indescribable’ was released, taking the place of self (Bax 1968: 26–7). Ananda Metteyya sought continually to define this ‘something’. He sometimes appealed to non-possessive love, but more often to compassion or pity, rooted in the realization:

Compassion was the highest point in human evolution for Ananda Metteyya and it led to a missionary commitment to spread a more humane ethic:

Within the writers I have covered, Ananda Metteyya was the first, as far as I know, to use the phrase, ‘One Life’. But he was not the first Westerner in Myanmar to do so. A civil servant with an empathic understanding of Buddhism similar to Dickson’s, H. Fielding Hall, had used the term in 1898, claiming he had drawn from oral data (Fielding Hall 1906: 250). And Frank Woodward would use it after him, from Sri Lanka (Woodward 1914: 48).

Morality and meditation

Two distinct lines of teaching are present in Ananda Metteyya’s work about how to begin the Buddhist path: act with generosity and it will affect your mind; work on your mind through meditation and it will affect both your mind and your action. He was aware that many Buddhists in Myanmar were generous simply to gain a better rebirth. He did not condemn this, but claimed that the action itself could modify the motivation, by widening, ‘the petty limits of man’s selfhood’ (Bennett 1929: 65). In other words, the Dhamma could teach that, ‘like a flame of fire, Love kindles Love, grows by the mere act of loving’ (Bennett 1929: 66).

If action could be mind-changing, Ananda Metteyya insisted that meditation could be action-changing and that it was essential, even at the beginning of the path. Sila (morality) and dana (generosity)11 were not enough alone (Bennett 1929: 327). Only meditation could give insight into the how and why of the mind and heart, enabling a person to change the constitution of his being through the power of the ‘mental element’ (Bennett 1908b: 284).

Ananda Metteyya’s response to Westerners who branded meditation as selfish was simply that ‘from the Buddhist view-point, all reformation, all attempt to help on life, can best be effected by first reforming the immediate life-kingdom of the “self"’ (Bennett 1929: 232). In other words, if you wanted to help the whole world, there was no better place to start than with the self: ‘Each thought of love, each effort after purity man makes or thinks is gain to all’ (Bennett 1903a: 22). But it had to be the right kind of meditation. If it served only to magnify the ‘I’, it could be worse than the absence of meditation (Bennett 1929: 407–8).

One practice that Ananda Metteyya recommended as action-changing at the beginning of the path was meditation on a brahmavihara (divine abiding) or an attribute of existence. Meditation on compassion, the second brahmavihara, for instance, could, he believed, open up a path with ‘power to help relieve the sorrow of the world’ (Bennett 1929: 329–30).

Right ‘watchfulness’ or ‘recollectedness’, the translation he gave of sati, more frequently translated as mindfulness, was a further practice Ananda Metteyya recommended to all, including beginners. He defined it as the observation and classification of thought, speech and action and ‘the constant application to each and all of them of the Doctrine of Selflessness’ with the thought, ‘This is not I, this is not Mine, there is no Self herein’ (Bennett 1929: 87).12 This meticulous discipline, Ananda Metteyya taught, could lead to samadhi, which he judged a higher form of meditation that could bring sudden insight.

Ananda Metteyya could find no adequate English translation for the word samadhi, usually defined as concentration, preferring the word ‘ecstacy’. He linked it with non-dual insight into the ‘One Life’. Usually the mind is like a flickering flame, he explained, oscillating continually between consciousness and unconsciousness. In samadhi the flame burns steadily and, ‘the true understanding of the Oneness of Life that makes for Peace, can be won’ (Bennett 1929: 393).

Ananda Metteyya rarely mentioned the jhana, meditative absorptions. But his writings contain one intense description of an experience that he links with entering the first, although its quality speaks more of the attainment of stream-entry (sotapatti), the first of four traditional supermundane paths in Theravada Buddhism. Meditation on compassion came first and then, a burst of liberating consciousness:

Ananda Metteyya did not stress upekkha, equanimity, the quality normally linked with the third and fourth jhana. Yet, there is one interesting definition of it, possibly directed at those who linked the term with apathy: ‘Discrimination or Aloofness from the worldly life’ (Bennett 1923: 104).

Nibbana – inalienable peace

Lying in creative tension within Ananda Metteyya’s work were two images: nibbana as near and attainable; nibbana as distant and indescribable. When new to monastic life, in Myanmar, it was as though he could turn the page of anicca, dukkha, anatta and find nibbana lying on the other side (Bennett 1929: 174). He wrote down his thoughts on it in the first issue of Buddhism (Bennett 1903b). ‘Peace’ was the word he used most frequently at this point to describe it, a peace linked with the death of the ‘I’. ‘It grows but from the ashes of the self outburnt’ (Bennett 1929: 48) he graphically wrote. And those who would equate it with the nihilistic he vehemently challenged:

In 1917, as war raged, however, he was less euphoric:

Yet, in the same talk, he could add that it lay ‘nearer to us than our nearest consciousness; even as, to him who rightly understands, it is dearer than the dearest hope that we can frame’ (Bennett 1923: 125). Struggling to explain it to Clifford Bax, though, he drew on atomic science: what happened at arahantship could be similar to atomic disintegration. Forces that had been bound together were separated and transformed into something completely different (Bax 1968: 28).

The danger of science and rationalism

As a young monk, Ananda Metteyya saw Buddhism and science walking hand in hand to bring hope to the West. Before 1914, he could claim that the knowledge science fostered would pave the way to ‘a grander and more stable civilization than ever the world has known’ through ‘the true comprehension of the nature of life and thought and hence of the universe in which we live’ (Bennett 1904b: 533). It would be a ‘New Civilisation’ in which ‘unerring Reason’ would be substituted for ‘the transitory dreams of the emotions’ (Bennett 1904b: 540).

Reason, he believed, could lead to an appreciation of Truth that would humanize society and break war-generating hatred. He was also convinced that only time was needed for science to uncover the material and psychic secrets of the universe.

Lying behind this hope was an evolutionary theory, not the kind favoured by the theosophists, but a corporate form. He imagined it as a movement from childhood to adulthood with two trajectories: one connected with compassion and the other with wisdom. Within the first, the stage of ‘childhood’ was when good was done from fear of punishment. Adolescence came when the motivation changed to the selfishness that saw the fruit of good deeds. The stage of adulthood was when good was done with no expectation of reward (Bennett 1905: 3). Within the second, childhood was when moral imperatives were accepted without question as the dictates of a hypothetical supreme being. Adolescence was the age of investigation and questioning, and adulthood the age of understanding.

When Ananda Metteyya looked at the West from Myanmar before 1908, he saw the age of investigation. He saw reason beginning to triumph over an ontology based on unquestioning faith, the mark of childhood. He was willing to praise the Western mind for its ‘incomparable achievements’ in science (Bennett 1929: 253) and looked forward to an age of understanding, as science and Buddhism joined hands. Never did he slip into the ‘trope of the child’, as identified by postcolonial writers such as Sugirtharajah: the tendency of orientalists to locate the East in a pre-enlightenment, innocent state of childhood (Sugirtharajah 2003: 31–2, 67–9). It was the West that was emerging from a state of childhood.

The First World War changed this. Ananda Metteya’s belief that the West could be reaching adolescence through severing itself from blind faith was destroyed. So, in 1920, as Allan Bennett, he lamented that scientific advance had not been accompanied by ‘improvement in matters of morality and self-restraint’ and added,

In spite of this, the final writings of Allan Bennett were optimistic. He stood before the Buddhist Society on Vesak Day, 1918, while the war still raged, and admitted that force seemed to be triumphing over reason, hate over truth and love, and heartless greed over charity (Bennett 1920a: 141–2). He recounted the Buddhist narrative of the Sakyans’ willingness to be destroyed rather than fight, and suggested that Britain should have followed that path in 1914 (Bennett 1920a: 142) in stark contrast to words uttered in 1904.13 Yet, he also exhorted everyone to have faith that ‘the Good’ would conquer in the end, and to hold fast to cultivating the ‘Heart’s Kingdom’ where truth and compassion lay. He concluded:

After the war, he urged Buddhists in Britain to move outwards. One thing the war had done, he believed, was to shake people out of apathy and materialism. Therefore, in 1920, he could write, ‘no period could possibly be more propitious to the fulfilment of our aims than that upon which we have entered’ – the aim of building Buddhism up in Britain (Bennett 1920b: 181).14

Concluding thoughts

A progression can be seen in Allan Bennett/Ananda Metteyya’s thought. In his early years as a monk, science, reason and the Dhamma seemed to offer joint hope to the world. In his later years, he realised that it was not scientific advance that would pave the way for Buddhism’s success in the West but the experience of dukkha, suffering. So, eventually, it was the religious life of Myanmar, not the scientific laboratory, that gave Ananda Metteyya his primary inspiration. In his 1917 lectures, the contrasts he wove between the brightness and intensity of Buddhist faith in Myanmar, and the greyness of wartime England were aimed at the heart rather than the intellect, at experience rather than rational argument. ‘Till I went out to the East’, he declared, ‘I did not know what it was to experience the awakening to the Buddhist light of day’ (Bennett 1923: 5). In the West, he added, one cannot find religion as such ‘a vivid, potent, living force’ as in the East (Bennett 1923: ix):

The intensity of this awareness sometimes made the Dhamma appear to him as a bright, almost tangible, external force leading human effort onwards. There is a remarkable passage from his 1917 talks in which the Buddha and the Dhamma are seen as the source of regenerating power. Echoing Edwin Arnold, Allan Bennett stressed that there was a power ‘whereby we may enfranchise that droplet of Life’s ocean which we term ourselves’, a power that moved to good and manifested itself as sympathy and compassion. He located it in the Buddha and the Dhamma, and claimed that it ‘constitutes that force whereby we are ever, so to speak, drawn upwards out of this life in which we live, towards the State Beyond – Nirvana, the Goal towards which all Life is slowly but surely moving’ (Bennett 1923: 119).

_______________

Notes:

1 Crowley’s relationship with Bennett began when both were interested in occult mysticism, and petered out when Bennett became a convinced Buddhist. Pereira met Bennett in 1900 and the friendship lasted a lifetime. Together with the Venerable Narada, DrW.A. de Silva and Hema Basnayake, Pereira founded the Servants of the Buddha in 1921 to provide a discussion forum for English-speaking Buddhists. At 65 years he was ordained as the Venerable Kassapa. His father built Maithriya Hall, Bambalapitiya (Colombo) named after Ananda Metteyya.

2 Crowley claimed that he was known all over London ‘as the one Magician who could really do big-time stuff ’ (Grant 1972: 85), which included using a wand to render motionless a sceptic who doubted its power (Symonds and Grant 1989: 180).

3 Pereira later wrote that he had thought all Bennett had taught him about meditation at that time was Buddhist but later realized that it also contained, ‘mystic Christian, Western “occult” and Hindu sources’ (Pereira 1947: 67).

4 In the late 1880s, the remedies prescribed by doctors for asthma included cocaine, opium and morphine. Bennett was heavily dependent on them (Symonds and Grant 1989: 180). See James Adam 1913, which advises the use of cocaine and, with restrictions, morphine; A.C. Wootton 1910, which affirms the beneficial effects of laudanum, an opium-based drug; Thorowgood 1894, which recommends arsenical cigarettes, cocaine, cannabis, and morphine together with less toxic drugs.

5 Ananda Metteyya became General Secretary, with Dr E.R. Rost, a Western convert to Buddhism and member of the Indian Medical Service, the Honorary Secretary. For further information about Rost see Humphreys 1968: 3–5.

6 Editorial comment, Buddhism 1, 3 March 1904: 473.

7 BR, I, 1909: 3.

8 Pereira gives no date for this. See Harris 1998: 14.

9 BR, 8, 1916: 217–9.

10 No gravestone has ever been placed on Allan Bennett’s grave, perhaps because suspicions concerning his link with esotericism continued. See Harris 1998: 17.

11 In Sri Lanka, the traditional threefold classification is: dana, sila, bhavana (giving, morality, meditation). Ananda Metteyya describes his classification, sila, dana, bhavana, as: avoiding evil, charity, meditation.

12 See also Bennett 1923: 94.

13 A 1904 editorial by Ananda Metteyya had commended the war between Japan and Russia as the fight of Japan, a Buddhist power, against ‘the most ruthless of the Christian powers’ (Buddhism, I, 4: 649).

14 He added at the end:

by Elizabeth J. Harris

2006

© 2006 Elizabeth J. Harris

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

-- Honour Thy Fathers: A Tribute to the Venerable Kapilavaddho ... And brief History of the Development of Theravāda Buddhism in the UK, by Terry Shine

-- Ananda Metteyya [Charles Henry Allan Bennett]: The First British Emissary of Buddhism [Excerpt], by Elizabeth J. Harris

-- Convert to Compassion: Allan Bennett, from Theravada Buddhism and the British Encounter: Religious, Missionary and Colonial Experience in Nineteenth Century Sri Lanka [Excerpt], by Elizabeth J. Harris

-- Charles Henry Allan Bennett, by Wikipedia

-- Allan Bennett, by AstrumArgenteum.org

--Allan Bennett, by George Knowles

Behind all this thrilling, hoping life, reigns Death...Nature is a battle-field....all this life is a cheat, a snare, – so long as you look at it from this standpoint of the individual.....

Buddhahood consists not in His humanity, but rather in the fact that, through lives of incredible effort and endurance, He has attained to a spiritual evolution which renders Him as different from a human being as the Sun is different from one of its servient planets; which makes of Him, His personality whilst it endures; His teaching, after that personality has passed away; a focal centre of spiritual power no less mighty in its sphere than that of the Sun in the material realm....

Crowds ... turn their faces to bathe them in the splendour of His very presence...

A follower of The Buddha, rightly will he merit the name of Buddhist, who walks the Way The Buddha found...

Life, so far as it is individualised, enselfed, ensouled is – even as the Reason teaches – evil, coterminous with Pain . . . Give up all hope, all faith in Self . . . Dream no more ‘I am’ or ‘I shall be’ but realise, Life suffers; and only by destruction of life’s cause in Selfhood can that suffering be relieved, and Life pass nearer to the Other Shore....

Just as all the waters of the ocean are one water, and one body of water, so it is with this universal teeming life; and just as, in the great ocean, there is, and can be by the very nature of it, no individual body of water separate from the rest, so in life’s ocean there is – and can be by the very nature of it – no single separate unit or body of life, whether it be the highest or the lowest, most subtle or most gross . . . Each satta – each living being that our Nescience makes us regard as an individual, a real and separate entity, a self or soul or Atma – is in truth only one such wave, whether a billow or a ripple only, upon the surface of life’s ocean....

Pity is the highest Law of Life, – this is in Buddhism accounted the true beginning of all righteousness, – unselfishness that gives all...

Seeing . . . how Life is One . . . let us live no more for self’s fell phantasy, but for the All . . . let us live so that the All, the One, may be the nobler and the greater for our life.....

Mindfulness...as the observation and classification of thought, speech and action and ‘the constant application to each and all of them of the Doctrine of Selflessness’ with the thought, ‘This is not I, this is not Mine, there is no Self herein’....

Samadhi... ‘ecstacy’... non-dual insight into the ‘One Life’....

Suddenly the lightning flashes, and for an instant the unseen world gleams forth in instantaneous light, light penetrating every darkest corner, flushing the clouded sky with momentary glory.... No words, no similes, no highest thought of ours can adequately convey that mighty realisation... we shall realise that all our life has changed of a sudden... the utmost attainment that the mind or the life of man can compass – that is ours at last; we have won, achieved, and entered into the Path of which mere words can never tell....

Annihilation of the threefold fatal fire of Passion, Wrath and Ignorance... the annihilation of conditioned being, of all that has bound and fettered us; the Cessation of the dire delusion of life that has veiled from us the splendour of the Light Beyond... the End of All – the end of the long tortuous pilgrimage through worlds of interminable illusion; the End of Sorrow, of Impermanence, of Self-deceit.... from the torture of selfhood an eternal Liberation......

A Way that all might follow to the Light Beyond all Life....

That force whereby we are ever, so to speak, drawn upwards out of this life in which we live, towards the State Beyond – Nirvana.

-- Convert to Compassion: Allan Bennett, by Elizabeth J. Harris

15. CONVERT TO COMPASSION: Allan Bennett

His face was the most significant that I have ever seen. Twenty years of physical suffering had twisted and scored it: a lifetime of meditation upon universal love had imparted to it an expression that was unmistakable. His colour was almost dusky, and his eyes had the soft glow of dark amber . . . Above all, at the moment of meeting and always thereafter, I was conscious of a tender and far-shining emanation, an unvarying psychic sunlight, that environed his personality.

(Bax 1968: 23)

This was Clifford Bax’s impression of Allan Bennett (1872–1923) in 1918. Bennett was then a lay person, and he was sick, incapacitated by asthma for weeks at a time. But ten years earlier, as the venerable Ananda Metteyya, he had led the first Buddhist mission to England, from Myanmar. The Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland had been formed in preparation.

Allan Bennett’s life, after his discovery of Buddhism, was inspired by the conviction that the West needed Buddhism and had only to understand its message to embrace it. He laid down a threefold agenda in the first edition of the journal he edited from Myanmar. First, he imagined a West that was losing both religious and moral awareness:

Apart altogether from the misery that that civilization has spread in lands beyond its pale, can it be claimed that in its internal polity, that for its own peoples, it has brought with it any diminution of the world’s suffering, any diminution of its degradation, its misery, its crime; above all, has it brought about any general increase of its native contentment, the extension of any such knowledge as promotes the spirit of mutual helpfulness rather than the curse of competition?

(Bennett 1903a: 12)

‘No’, was his answer and he backed this up with reference to the West’s ‘crowded taverns’, ‘overflowing gaols’, ‘sad asylums’ and its neglect of mental culture (Bennett 1903a: 13). Second, he rejected three ‘misconceptions’ about Buddhism: that it was heathen and idolatrous; that it was connected with ‘miracle-mongering and esotericism’; that it was ‘a backboneless, apathetic, pessimistic manner of philosophy’ (Bennett 1903a: 25). Third, he put across what he believed Buddhism to be: rational and optimistic. Later he would contest, in addition, two ‘onlys’: that Buddhism was only a rational philosophy; and that the Buddha was only a remarkable and enlightened teacher.

To this apologetic task, Allan Bennett brought a poetic imagination, a scientific mind and a deep concern for justice and peace. And in Allan Bennett, compassion moves centre stage as Buddhism’s sine qua non.

Bennett’s life

In piecing together the biography of Allan Bennett, I am heavily indebted to the writings of two of his closest friends, Aleister Crowley and Dr Cassius Pereira.1 Bennett was born in London. His father, a civil and electrical engineer, died when he was young. Pereira claimed he was adopted by a Mr McGregor and kept this name until McGregor died, a fact repeated to me by the venerable Balangoda Ananda Metteyya (Harris 1998: 4). Yet, it is possible that his mother was still in contact, since Crowley refers to him being brought up by his mother as a strict Catholic (Symonds and Grant 1989: 180). This might explain his later opposition to any form of religion that placed more importance on ‘sin’ than love. After an education in Bath, he trained as an analytical chemist and was eventually employed by a Dr Bernard Dyer, a public analyst and consulting chemist then based in London (Grant 1972: 82).

The limited information available suggests that Bennett was a sensitive and serious young man, who became alienated from Christianity both because it seemed incompatible with science, and because he could not reconcile the concept of a God of love with the suffering he saw and experienced. The asthma that plagued his life seems to have begun in childhood. It prevented him from holding down a permanent job, meaning that he was at times desperately poor and ill. ‘Allan never knew joy,’ Crowley wrote, ‘he disdained and distrusted pleasure from the womb’ (Symonds and Grant 1989: 234).

Bennett did not, however, distrust the search for truth and goodness. And his two keys to this were science and religion. His religious quest was experimental, even daring. After rejecting Roman Catholicism, he turned first to Asia. At the age of 18, The Light of Asia influenced him, but it was part of a larger exploration that embraced Hindu literature, yogic forms of breath control and meditation (Grant 1972: 85; Symonds and Grant 1989: 246–7) and eventually Western esoteric mysticism.

In 1894, Bennett joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, founded in 1889 by William Wynn Westcott and Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers, taking the name Iehi Aour, Hebrew for ‘let there be light’. He rose to the top rapidly, known for his psychic powers.2 Most of the available information about Bennett at this point comes through Crowley, who joined the Order in 1898. He speaks of Bennett as tall but stooped because of illness, with ‘a shock of wild, black hair’ and a noble head, adding, ‘I did not fully realize the colossal stature of that sacred spirit; but I was instantly aware that this man could teach me more in a month than anyone else in five years’ (Symonds and Grant 1989: 181).

The next stage in Bennett’s life began when he travelled to Sri Lanka in 1900 for health reasons, Crowley paying his passage in the hope that this would save his life and spread Western esotericism in the East. But Bennett was more interested in exploring the local, learning yoga, for instance, from P. Ramanathan, the Solicitor-General.3 According to Pereira, he also went to Kamburugamuwa and studied Pali under an elder Sinhala monk. By the end of six months, Pereira claimed, he could converse in it fluently, adding, ‘Such was the brilliance of his intellect’ (Pereira 1923: 6).

Sri Lanka was a turning point for Bennett. His asthma improved. He gave up the cycle of drugs he had found necessary in England.4 Most of all, he found the answer to his religious quest in Theravada Buddhism, rejecting his former eclectic experimentation with psychic and esoteric power (Symonds and Grant 1989: 237, 249). By the time he addressed the Hope Lodge of the Theosophical Society, Colombo, in July 1901, he had probably decided that he would become a Buddhist monk.

Bennett was ordained a novice in Akyab, Arakan, Myanmar on 12 December 1901, taking the name Ananda Maitreya, which he later changed to the Pali, Metteyya. Higher ordination followed on 21 May 1902, under the venerable Sheve Bya Sayadaw. When Crowley next visited Myanmar, he was in a monastery just outside Rangoon. From there, on 13 March 1903, he inaugurated the Buddhasasana Samagama, an international Buddhist society that aimed at the global networking of Buddhists.5 It soon had official representatives in Austria, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, China, Germany, Italy, America and England. In the same year, he launched Buddhism – An Illustrated Quarterly Review, which, by 1904, was being sent free to between 500 and 600 libraries in Europe.6

The first Buddhist mission to England

Ananda Metteyya arrived in England on 23 April 1908 to an eager welcome from the Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland, formed the previous November. He remained until 2 October, ‘the time allotted to the Mission,’ according to Christmas Humphreys (Humphreys 1968: 7). Although Ananda Metteyya told a Rangoon paper that he was highly gratified with the visit, it was a qualified success. On the positive side there was his grace and dignity, his ‘pleasing voice and beautiful enunciation’ (Humphreys 1968: 6), his knowledge of Buddhism, the scholars he gathered around him through ‘correspondence and constant interviews’ (Humphreys 1968: 6) and his engaging manner in private conversation (Humphreys 1972: 133). Yet, ensuring he could follow his monastic discipline stretched his supporters to the limit (Bell 2000). His orange robes in the streets caused laughter, and his public speaking style was uncharismatic, since he would avoid eye contact, keeping his eye on a prepared script. Nevertheless, the Buddhist Society’s journal, The Buddhist Review (BR), could say in 1909 that he left behind him, ‘golden opinions and the friendship and respect of all who had the privilege of meeting him’.7

Ananda Metteyya hoped he would return to England within three years to establish a permanent Buddhist community in the West. The hope died. One reason for this was his health, which failed rapidly on his return to Myanmar. Pereira records that he underwent two operations and reluctantly agreed to leave the Order on medical advice (Pereira 1923: 6).8 In 1914, Burmese friends sent him to England where he intended to sail from Liverpool to America to stay with his sister, but the ship’s doctor refused him passage.

From this point onwards, Allan Bennett’s story was a sad one. A doctor who was a member of the Liverpool Branch of the Buddhist Society took him in, but the financial and emotional burden of this proved too great. In 1916, an anonymous group of well-wishers appealed for money through the Buddhist Society to save Bennett from being placed ‘in some institution supported by public charity’.9

Help came, from overseas as well as Britain, and Bennett’s health rallied. In the winter of 1917–1918, he gave a series of papers to a private audience in Clifford Bax’s studio. Then, on Vesak Day (May) 1918, Bennett gave to the Buddhist Society what Christmas Humphreys called ‘a “fighting speech” which aroused the listening members to fresh enthusiasm’ (Humphreys 1968: 14).

According to one account, Bennett moved to London in 1920 (Mullen 1989: 92). Although he was incapacitated for weeks at a time, he took over the editorship of the BR from the Sri Lankan scholar, D.B. Jayatileka. The January 1922 edition was the last he edited and indeed the last that was published. He died on 9 March 1923. A Buddhist funeral service was prepared by Francis Payne, a prominent Buddhist convert from the 1908 mission.10

I will use three main sources to explore Ananda Metteyya/Allan Bennett’s representation of Buddhism. The Religion of Burma and other Papers published by the Theosophical Publishing House of India in 1929 contains talks given in Myanmar, belonging to the first decade of the twentieth century. The Wisdom of the Aryas, published in London in 1923, the year of his death, consists of the lectures delivered in 1917–1918 plus one additional paper on rebirth. Finally, his writing in the journal Buddhism is most important.

A suffering world

Ananda Metteyya’s understanding of Buddhism began with awareness of suffering (dukkha). Speaking of the progression of thought in one who attempted to look at the world with ‘the cold, clear light of Reason’, he wrote:

Firstly, he sees Life, – the interminable waves of Life’s great Ocean all around him; the pulsing, breathing, gleaming waters of the Sea of Being; and, at first thought and sight of this, he thinks: this Life is Joy.

He lives. Living, he learns. Learning, he presently comes to know – for Learning is Suffering, and Suffering is Life. He sees beneath this so fair-seeming face of Nature lies everywhere corruption. Behind all this thrilling, hoping life, reigns Death; certain, inevitable, and by all life abhorred . . . He looks deeper into life, hoping that thus he may find the secret of happiness . . . Learning more, he sees that this Nature is a battle-field.

He sees each living creature fighting for its life, Self against the Universe . . . He sees at last how all this life is a cheat, a snare, – so long as you look at it from this standpoint of the individual. If he had had faith in God, – in some great Being who had devised the Universe, he can no longer hold it; for any being, now he clearly sees, who could have devised a Universe wherein which was all this wanton war, this piteous mass of pain coterminous with life, must have been a Demon, not a God.

(Bennett 1908a: 183–4)

Ananda Metteyya’s conclusion was that it was sacrifice that pervaded existence, not joy. His phrases were vivid: ‘Life ever offered up to Life on its own altar’ (Bennett 1923: 3); nature as ‘a slaughter-house wherein no thought of pity ever enters’ (Bennett 1929: 156); ‘Life alone can feed life’ (Bennett 1929: 170). And in ‘the Vast Emptiness’ of the cosmos there was a, ‘a horror of living past conceiving, full of the Pain of Being, darkened by Not-Understanding; thrilling with Hope in youth, and ever aging in Despair!’ (Bennett 1929: 142–3).

Part of Buddhism’s attraction for Ananda Metteyya was that it looked the truth of suffering in the eye (Bennett 1923: xiv). ‘To dare to look on life as it really is’ was the first step along the religious path (Bennett 1929: 221). It was into this suffering world that the Buddha came as liberator.

The Buddha

At a time when most Westerners were stressing the humanity and historicity of the Buddha, Ananda Metteyya was pointing out that no comparison with ordinary humanity was possible:

but his Buddhahood consists not in His humanity, but rather in the fact that, through lives of incredible effort and endurance, He has attained to a spiritual evolution which renders Him as different from a human being as the Sun is different from one of its servient planets; which makes of Him, His personality whilst it endures; His teaching, after that personality has passed away; a focal centre of spiritual power no less mighty in its sphere than that of the Sun in the material realm.

(Bennett 1923: 111)

It was compassionate self-sacrifice in innumerable lives preceding Buddhahood that qualified the Buddha for this, according to Ananda Metteyya, a sacrifice, ‘so great, so utterly beyond our ken, that we can only try to dimly represent it in terms of human life and thought and action’ (Bennett 1923: 16–17).

Acts of devotion to the Buddha, therefore, did not seem unnatural or irrational to Ananda Metteyya, and in this he knew he differed from some Western Buddhists (Bennett 1929: 341–2). When, in Myanmar, he came across an atmosphere of worship so intense that the air seemed to vibrate with a ‘palpable’ potency, an ‘immediate’ presence (Bennett 1923: 7), his reaction was not disdain but wonder. His disdain was for those who denied that the Buddha could be present in the lives of the people:

There, into the daily lives, the very speech and household customs of the common folk, this ever-present sun-light of the Teaching penetrated; there, hearing at a fiesta the gathered crowds take refuge in the Buddha, you could all but see them turn their faces to bathe them in the splendour of His very presence – till one could understand how, instead of getting angry when they hear the Christian missionaries tell them they are taking refuge in a Being whom their own religion tells them has passed utterly away, they always answer, as they do answer, only with a wise and a compassionate smile.

(Bennett 1923: 6)

The devotion of dependence and blind faith, however, he did criticize, as something akin to childhood. It could lead to heavenly rebirth but not to the ultimate goal (Bennett 1929: 370). There was a higher devotion connected with questioning, investigation and recognition: ‘the devotion that comes in the train of Understanding’ . . . ‘when we attain some glimpse of the tremendous meaning of the Love that has for us resulted in the knowledge of the Law we have’ (Bennett 1929: 320). Yet, ultimately:

The true worship of the Buddhas is not even in divinest-seeming outer offering or praise; rightly that one shall be called a follower of The Buddha, rightly will he merit the name of Buddhist, who walks the Way The Buddha found; that is, the Way, that He, the Master of Compassion, walked first Himself, twenty-five centuries ago in India.

(Bennett 1929: 320)

What the Buddha taught

Ananda Metteyya would have agreed with the theosophists that the key to the Buddhist view of the world, as taught by the Buddha, was Law, as shown in the Law of cause and effect (paticcasamuppada). But he did not see this as the exoteric component of an esoteric vision, but as making the need for the esoteric, obsolete. With the Law of Cause and Effect as shown in the Four Noble Truths (Bennett 1929: 320, 356), the need for esoteric knowledge, the goal of his youthful experimentation, was wiped out.

Ananda Metteyya could graphically describe dukkha, the First Noble Truth. His representation of the cause of dukkha varied. Sometimes he stressed tajha, craving, and appealed to science. Take the amoebae, he suggested, and dukkha can be seen. Amoebae move only when irritated, when feeling aversion. When still, they are at peace. From this, he continued, all other animal reactions have developed. By the time human aversion is reached, a thousand complex suffering-creating cravings have arisen. Yet, he preferred to cite avijja, ‘ignorance’, rather than tajha, most particularly ignorance of anatta, non-self.

Without knowledge of Buddhist ideas, he wrote, it is almost impossible to become aware ‘how much every mode of expression of western thought involves the assumption of the existence of a Self’ (Bennett 1908b: 279). The would-be Buddhist, therefore, had to learn:

Life, so far as it is individualised, enselfed, ensouled is – even as the Reason teaches – evil, coterminous with Pain . . . Give up all hope, all faith in Self . . . Dream no more ‘I am’ or ‘I shall be’ but realise, Life suffers; and only by destruction of life’s cause in Selfhood can that suffering be relieved, and Life pass nearer to the Other Shore.

(Bennett 1908a: 186–7)

There are echoes of Arnold and Rhys Davids here, but Ananda Metteyya went further. The message of the Buddha, he believed, was that dukkha was inseparably linked with belief in self. The realization of the falsity of the soul concept was, ‘the darkest hour in all the evolution of a man’. But it was ‘the darkest hour which goes before the dawn’ (Bennett 1904a: 369–70).

Undergirding this in Ananda Metteyya’s vision was cosmic interconnectedness, raised to the status of scientific truth. All life was one. There was ‘One Life’. The simile he most frequently used was of a wave:

Just as all the waters of the ocean are one water, and one body of water, so it is with this universal teeming life; and just as, in the great ocean, there is, and can be by the very nature of it, no individual body of water separate from the rest, so in life’s ocean there is – and can be by the very nature of it – no single separate unit or body of life, whether it be the highest or the lowest, most subtle or most gross . . . Each satta – each living being that our Nescience makes us regard as an individual, a real and separate entity, a self or soul or Atma – is in truth only one such wave, whether a billow or a ripple only, upon the surface of life’s ocean.

(Bennett 1904a: 165–7)

Arnold had stressed the interdependence of all. Ananda Metteyya again took the imagery further. All animal and plant life was so fused together that every action, movement or thought affected the whole, rendering meaningless any distinction between good for self and good for others. Non-recognition of this was the main cause of suffering.

When the sense of self was blown out, when the ‘One Life’ was recognized, according to Ananda Metteyya’s reading of the Buddha’s teaching, something ‘immeasurable and indescribable’ was released, taking the place of self (Bax 1968: 26–7). Ananda Metteyya sought continually to define this ‘something’. He sometimes appealed to non-possessive love, but more often to compassion or pity, rooted in the realization:

that we ourselves are but as transitory waves upon the Ocean of existence, – that all the good we do, the love we have, the wisdom that we garner and the help we give is wrought but for the reaping of the Universe, wrought because Pity is the highest Law of Life, – this is in Buddhism accounted the true beginning of all righteousness, – unselfishness that gives all, whilst knowing yet that it shall never reap the gain.

(Bennett 1904a: 363)

Compassion was the highest point in human evolution for Ananda Metteyya and it led to a missionary commitment to spread a more humane ethic:

Understanding how all of it is doomed to sorrow – wrought of the very warp and woof of Pain and Suffering and Despair – let the divine emotion of Compassion that wakes in us at the thought of it kill out all Hatred from our hearts and ways. Seeing . . . how Life is One . . . let us live no more for self’s fell phantasy, but for the All . . . let us live so that the All, the One, may be the nobler and the greater for our life.

(Bennett 1929: 177)

Within the writers I have covered, Ananda Metteyya was the first, as far as I know, to use the phrase, ‘One Life’. But he was not the first Westerner in Myanmar to do so. A civil servant with an empathic understanding of Buddhism similar to Dickson’s, H. Fielding Hall, had used the term in 1898, claiming he had drawn from oral data (Fielding Hall 1906: 250). And Frank Woodward would use it after him, from Sri Lanka (Woodward 1914: 48).

Morality and meditation

Two distinct lines of teaching are present in Ananda Metteyya’s work about how to begin the Buddhist path: act with generosity and it will affect your mind; work on your mind through meditation and it will affect both your mind and your action. He was aware that many Buddhists in Myanmar were generous simply to gain a better rebirth. He did not condemn this, but claimed that the action itself could modify the motivation, by widening, ‘the petty limits of man’s selfhood’ (Bennett 1929: 65). In other words, the Dhamma could teach that, ‘like a flame of fire, Love kindles Love, grows by the mere act of loving’ (Bennett 1929: 66).

If action could be mind-changing, Ananda Metteyya insisted that meditation could be action-changing and that it was essential, even at the beginning of the path. Sila (morality) and dana (generosity)11 were not enough alone (Bennett 1929: 327). Only meditation could give insight into the how and why of the mind and heart, enabling a person to change the constitution of his being through the power of the ‘mental element’ (Bennett 1908b: 284).

Ananda Metteyya’s response to Westerners who branded meditation as selfish was simply that ‘from the Buddhist view-point, all reformation, all attempt to help on life, can best be effected by first reforming the immediate life-kingdom of the “self"’ (Bennett 1929: 232). In other words, if you wanted to help the whole world, there was no better place to start than with the self: ‘Each thought of love, each effort after purity man makes or thinks is gain to all’ (Bennett 1903a: 22). But it had to be the right kind of meditation. If it served only to magnify the ‘I’, it could be worse than the absence of meditation (Bennett 1929: 407–8).

One practice that Ananda Metteyya recommended as action-changing at the beginning of the path was meditation on a brahmavihara (divine abiding) or an attribute of existence. Meditation on compassion, the second brahmavihara, for instance, could, he believed, open up a path with ‘power to help relieve the sorrow of the world’ (Bennett 1929: 329–30).

Right ‘watchfulness’ or ‘recollectedness’, the translation he gave of sati, more frequently translated as mindfulness, was a further practice Ananda Metteyya recommended to all, including beginners. He defined it as the observation and classification of thought, speech and action and ‘the constant application to each and all of them of the Doctrine of Selflessness’ with the thought, ‘This is not I, this is not Mine, there is no Self herein’ (Bennett 1929: 87).12 This meticulous discipline, Ananda Metteyya taught, could lead to samadhi, which he judged a higher form of meditation that could bring sudden insight.

Ananda Metteyya could find no adequate English translation for the word samadhi, usually defined as concentration, preferring the word ‘ecstacy’. He linked it with non-dual insight into the ‘One Life’. Usually the mind is like a flickering flame, he explained, oscillating continually between consciousness and unconsciousness. In samadhi the flame burns steadily and, ‘the true understanding of the Oneness of Life that makes for Peace, can be won’ (Bennett 1929: 393).

Ananda Metteyya rarely mentioned the jhana, meditative absorptions. But his writings contain one intense description of an experience that he links with entering the first, although its quality speaks more of the attainment of stream-entry (sotapatti), the first of four traditional supermundane paths in Theravada Buddhism. Meditation on compassion came first and then, a burst of liberating consciousness:

As from the heart of a dark thundercloud at night time when nought or but a little of earth or heaven can be seen, suddenly the lightning flashes, and for an instant the unseen world gleams forth in instantaneous light, light penetrating every darkest corner, flushing the clouded sky with momentary glory – so then, at that great moment, will come the realisation of all our toil. No words, no similes, no highest thought of ours can adequately convey that mighty realisation; but then, at that time, we shall know and see; we shall realise that all our life has changed of a sudden, and what of yore we deemed Compassion – what of old we deemed the utmost attainment that the mind or the life of man can compass – that is ours at last; we have won, achieved, and entered into the Path of which mere words can never tell.

(Bennett 1929: 333–4)

Ananda Metteyya did not stress upekkha, equanimity, the quality normally linked with the third and fourth jhana. Yet, there is one interesting definition of it, possibly directed at those who linked the term with apathy: ‘Discrimination or Aloofness from the worldly life’ (Bennett 1923: 104).

Nibbana – inalienable peace

Lying in creative tension within Ananda Metteyya’s work were two images: nibbana as near and attainable; nibbana as distant and indescribable. When new to monastic life, in Myanmar, it was as though he could turn the page of anicca, dukkha, anatta and find nibbana lying on the other side (Bennett 1929: 174). He wrote down his thoughts on it in the first issue of Buddhism (Bennett 1903b). ‘Peace’ was the word he used most frequently at this point to describe it, a peace linked with the death of the ‘I’. ‘It grows but from the ashes of the self outburnt’ (Bennett 1929: 48) he graphically wrote. And those who would equate it with the nihilistic he vehemently challenged:

If I am asked, ‘Is the Nibbana Annihilation? Is it Cessation? Is it the End of All?’ I reply, thus even have we learned. It is Annihilation – the annihilation of the threefold fatal fire of Passion, Wrath and Ignorance. It is Annihilation – the annihilation of conditioned being, of all that has bound and fettered us; the Cessation of the dire delusion of life that has veiled from us the splendour of the Light Beyond. It is the End of All – the end of the long tortuous pilgrimage through worlds of interminable illusion; the End of Sorrow, of Impermanence, of Self-deceit. From the torment of the sad Dream of Life an everlasting Awakening, – from the torture of selfhood an eternal Liberation; – a Being, an Existence, that to name Life were sacrilege, and to name Death a lie: – unnameable, unthinkable, yet even in this life to be realised and entered into.

(Bennett 1903b: 133)

In 1917, as war raged, however, he was less euphoric:

Nirvana stands for the Ultimate, the Beyond, and the Goal of Life – a State so utterly different from this conditioned ever-changing being of the Self-dream that we know as to lie not only quite Beyond all naming and describing; but far past even Thought itself.

(Bennett 1923: 124)

Yet, in the same talk, he could add that it lay ‘nearer to us than our nearest consciousness; even as, to him who rightly understands, it is dearer than the dearest hope that we can frame’ (Bennett 1923: 125). Struggling to explain it to Clifford Bax, though, he drew on atomic science: what happened at arahantship could be similar to atomic disintegration. Forces that had been bound together were separated and transformed into something completely different (Bax 1968: 28).

The danger of science and rationalism

As a young monk, Ananda Metteyya saw Buddhism and science walking hand in hand to bring hope to the West. Before 1914, he could claim that the knowledge science fostered would pave the way to ‘a grander and more stable civilization than ever the world has known’ through ‘the true comprehension of the nature of life and thought and hence of the universe in which we live’ (Bennett 1904b: 533). It would be a ‘New Civilisation’ in which ‘unerring Reason’ would be substituted for ‘the transitory dreams of the emotions’ (Bennett 1904b: 540).

Reason, he believed, could lead to an appreciation of Truth that would humanize society and break war-generating hatred. He was also convinced that only time was needed for science to uncover the material and psychic secrets of the universe.

Lying behind this hope was an evolutionary theory, not the kind favoured by the theosophists, but a corporate form. He imagined it as a movement from childhood to adulthood with two trajectories: one connected with compassion and the other with wisdom. Within the first, the stage of ‘childhood’ was when good was done from fear of punishment. Adolescence came when the motivation changed to the selfishness that saw the fruit of good deeds. The stage of adulthood was when good was done with no expectation of reward (Bennett 1905: 3). Within the second, childhood was when moral imperatives were accepted without question as the dictates of a hypothetical supreme being. Adolescence was the age of investigation and questioning, and adulthood the age of understanding.

When Ananda Metteyya looked at the West from Myanmar before 1908, he saw the age of investigation. He saw reason beginning to triumph over an ontology based on unquestioning faith, the mark of childhood. He was willing to praise the Western mind for its ‘incomparable achievements’ in science (Bennett 1929: 253) and looked forward to an age of understanding, as science and Buddhism joined hands. Never did he slip into the ‘trope of the child’, as identified by postcolonial writers such as Sugirtharajah: the tendency of orientalists to locate the East in a pre-enlightenment, innocent state of childhood (Sugirtharajah 2003: 31–2, 67–9). It was the West that was emerging from a state of childhood.

The First World War changed this. Ananda Metteya’s belief that the West could be reaching adolescence through severing itself from blind faith was destroyed. So, in 1920, as Allan Bennett, he lamented that scientific advance had not been accompanied by ‘improvement in matters of morality and self-restraint’ and added,

For stability, it is essential that every advance in the conquest over nature should be accompanied by an equal advance in the conquest over self; – over the spirits of greed and passion and ambition, which have brought this late calamity upon our Western world.

(Bennett 1920b: 3)

In spite of this, the final writings of Allan Bennett were optimistic. He stood before the Buddhist Society on Vesak Day, 1918, while the war still raged, and admitted that force seemed to be triumphing over reason, hate over truth and love, and heartless greed over charity (Bennett 1920a: 141–2). He recounted the Buddhist narrative of the Sakyans’ willingness to be destroyed rather than fight, and suggested that Britain should have followed that path in 1914 (Bennett 1920a: 142) in stark contrast to words uttered in 1904.13 Yet, he also exhorted everyone to have faith that ‘the Good’ would conquer in the end, and to hold fast to cultivating the ‘Heart’s Kingdom’ where truth and compassion lay. He concluded:

When, then, the dark clouds of the sad world’s dreaming gather thick around us . . . when the vast agony of life about us grips our hearts well-nigh to suffocation; even when death itself draws near; in each and every bitter circumstance of life we can find solace and new inspiration in the Law our Master left . . . And so, remembering, remembering how that great hope came to us; how He that won it was no God, but one just like ourselves, who suffered through life after life, yet ever strove to find a Way that all might follow to the Light Beyond all Life.

(Bennett 1920a: 147–8)

After the war, he urged Buddhists in Britain to move outwards. One thing the war had done, he believed, was to shake people out of apathy and materialism. Therefore, in 1920, he could write, ‘no period could possibly be more propitious to the fulfilment of our aims than that upon which we have entered’ – the aim of building Buddhism up in Britain (Bennett 1920b: 181).14

Concluding thoughts

A progression can be seen in Allan Bennett/Ananda Metteyya’s thought. In his early years as a monk, science, reason and the Dhamma seemed to offer joint hope to the world. In his later years, he realised that it was not scientific advance that would pave the way for Buddhism’s success in the West but the experience of dukkha, suffering. So, eventually, it was the religious life of Myanmar, not the scientific laboratory, that gave Ananda Metteyya his primary inspiration. In his 1917 lectures, the contrasts he wove between the brightness and intensity of Buddhist faith in Myanmar, and the greyness of wartime England were aimed at the heart rather than the intellect, at experience rather than rational argument. ‘Till I went out to the East’, he declared, ‘I did not know what it was to experience the awakening to the Buddhist light of day’ (Bennett 1923: 5). In the West, he added, one cannot find religion as such ‘a vivid, potent, living force’ as in the East (Bennett 1923: ix):

For you must understand that this is no mere cut-and-dried philosophy – as it may seem to one who reads of it out here in books – but a living, breathing Truth; a mighty power able to sweep whomsoever casts himself wholeheartedly into its great streams, far and beyond the life we know and live.

(Bennett 1923: 7)

The intensity of this awareness sometimes made the Dhamma appear to him as a bright, almost tangible, external force leading human effort onwards. There is a remarkable passage from his 1917 talks in which the Buddha and the Dhamma are seen as the source of regenerating power. Echoing Edwin Arnold, Allan Bennett stressed that there was a power ‘whereby we may enfranchise that droplet of Life’s ocean which we term ourselves’, a power that moved to good and manifested itself as sympathy and compassion. He located it in the Buddha and the Dhamma, and claimed that it ‘constitutes that force whereby we are ever, so to speak, drawn upwards out of this life in which we live, towards the State Beyond – Nirvana, the Goal towards which all Life is slowly but surely moving’ (Bennett 1923: 119).

_______________

Notes:

1 Crowley’s relationship with Bennett began when both were interested in occult mysticism, and petered out when Bennett became a convinced Buddhist. Pereira met Bennett in 1900 and the friendship lasted a lifetime. Together with the Venerable Narada, DrW.A. de Silva and Hema Basnayake, Pereira founded the Servants of the Buddha in 1921 to provide a discussion forum for English-speaking Buddhists. At 65 years he was ordained as the Venerable Kassapa. His father built Maithriya Hall, Bambalapitiya (Colombo) named after Ananda Metteyya.

2 Crowley claimed that he was known all over London ‘as the one Magician who could really do big-time stuff ’ (Grant 1972: 85), which included using a wand to render motionless a sceptic who doubted its power (Symonds and Grant 1989: 180).

3 Pereira later wrote that he had thought all Bennett had taught him about meditation at that time was Buddhist but later realized that it also contained, ‘mystic Christian, Western “occult” and Hindu sources’ (Pereira 1947: 67).

4 In the late 1880s, the remedies prescribed by doctors for asthma included cocaine, opium and morphine. Bennett was heavily dependent on them (Symonds and Grant 1989: 180). See James Adam 1913, which advises the use of cocaine and, with restrictions, morphine; A.C. Wootton 1910, which affirms the beneficial effects of laudanum, an opium-based drug; Thorowgood 1894, which recommends arsenical cigarettes, cocaine, cannabis, and morphine together with less toxic drugs.

5 Ananda Metteyya became General Secretary, with Dr E.R. Rost, a Western convert to Buddhism and member of the Indian Medical Service, the Honorary Secretary. For further information about Rost see Humphreys 1968: 3–5.

6 Editorial comment, Buddhism 1, 3 March 1904: 473.

7 BR, I, 1909: 3.

8 Pereira gives no date for this. See Harris 1998: 14.

9 BR, 8, 1916: 217–9.

10 No gravestone has ever been placed on Allan Bennett’s grave, perhaps because suspicions concerning his link with esotericism continued. See Harris 1998: 17.

11 In Sri Lanka, the traditional threefold classification is: dana, sila, bhavana (giving, morality, meditation). Ananda Metteyya describes his classification, sila, dana, bhavana, as: avoiding evil, charity, meditation.

12 See also Bennett 1923: 94.

13 A 1904 editorial by Ananda Metteyya had commended the war between Japan and Russia as the fight of Japan, a Buddhist power, against ‘the most ruthless of the Christian powers’ (Buddhism, I, 4: 649).

14 He added at the end:

These facts, we consider, justify us in our conclusion that in the extension of this great Teaching lies not only the solution of the ever-growing religious problems of the West; but even, perhaps, the only possible deliverance of the western civilization from that condition of fundamental instability which now so obviously and increasingly prevails.

(Bennett 1920b: 187)