Re: Freda Bedi, by Wikipedia

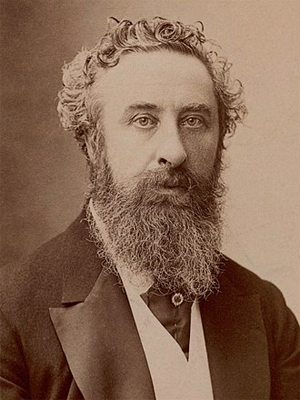

Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 11/3/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

His Excellency, The Right Honourable, The Earl of Lytton, GCB GCIE PC

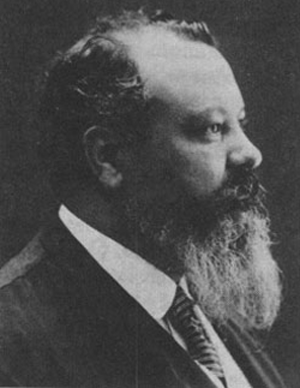

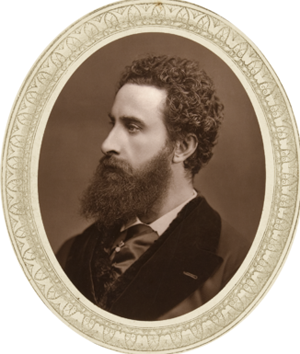

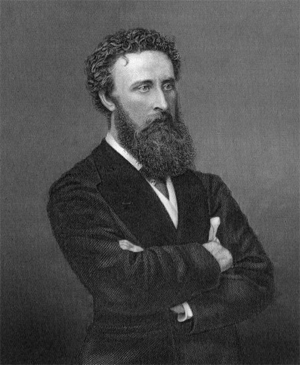

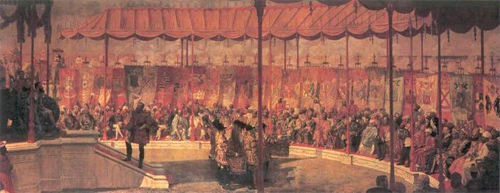

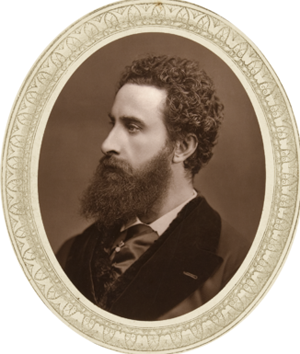

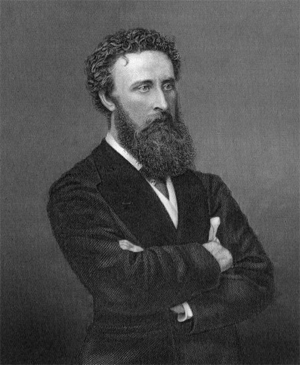

Earl of Lytton, photo by Nadar

British Ambassador to France

In office: 1887–1891

Monarch: Queen Victoria

Preceded by: The Viscount Lyons

Succeeded by: The Marquess of Dufferin and Ava

Viceroy and Governor-General of India

In office: 12 April 1876 – 8 June 1880

Monarch: Queen Victoria

Preceded by: The Earl of Northbrook

Succeeded by: The Marquess of Ripon

Personal details

Born: 8 November 1831

Died: 24 November 1891 (aged 60)

Nationality: British

Political party: Conservative

Spouse(s): Edith Villiers

Children: 7

Parents: Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton; Rosina Doyle Wheeler

Education: Harrow School

Alma mater: University of Bonn

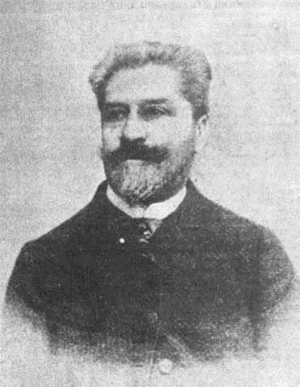

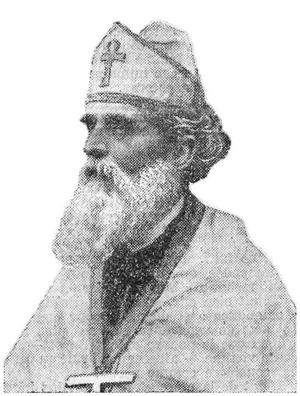

Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton, GCB, GCSI, GCIE, PC (8 November 1831 – 24 November 1891) was an English statesman, Conservative politician, and poet (who used the pseudonym Owen Meredith). He served as Viceroy of India between 1876 and 1880—during his tenure Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India—and as British Ambassador to France from 1887 to 1891.

His tenure as Viceroy was extremely successful, but controversial for its ruthlessness in both domestic and foreign affairs: especially for his response to the Great Famine of 1876–78, and the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Lytton's policies were alleged to be informed by his Social Darwinism. His son Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton, who was born in India, later served as Governor of Bengal and briefly as acting Viceroy, and he was the father-in-law of the architect Sir Edwin Lutyens, who designed New Delhi.

Lytton was a protégé of Benjamin Disraeli in domestic affairs, and of Richard Lyons, 1st Viscount Lyons, who was his predecessor as Ambassador to France, in foreign affairs. His tenure as Ambassador to Paris was successful, and Lytton was afforded the rare tribute – especially for an Englishman – of a French state funeral in Paris.

Childhood and education

Harrow School

Lytton was the son of the novelists Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton and Rosina Doyle Wheeler (who was the daughter of the early women's rights advocate Anna Wheeler). His uncle was Sir Henry Bulwer. His childhood was spoiled by the altercations of his parents,[1] who separated acrimoniously when he was a boy. However, Lytton received the patronage of John Forster - an influential friend of Leigh Hunt, Charles Lamb, Walter Savage Landor, and Charles Dickens - who was generally considered to be the first professional biographer of 19th century England.[2]

Lytton's mother, who lost access to her children, satirised his father in her 1839 novel Cheveley, or the Man of Honour. His father subsequently had his mother placed under restraint, as a consequence of an assertion of her insanity, which provoked public outcry and her liberation a few weeks later. His mother chronicled this episode in her memoirs.[3][4]

After being taught at home for a while, he was educated in schools in Twickenham and Brighton and thence Harrow,[5] and at the University of Bonn.[1]

Diplomatic career

Lytton entered the Diplomatic Service in 1849, when aged 18, when he was appointed as attaché to his uncle, Sir Henry Bulwer, who was Minister at Washington, DC.[6] It was at this time he met Henry Clay and Daniel Webster.[6] He began his salaried diplomatic career in 1852 as an attaché to Florence, and subsequently served in Paris, in 1854, and in The Hague, in 1856 .[6] In 1858, he served in St Petersburg, Constantinople, and Vienna.[6] In 1860, he was appointed British Consul General at Belgrade.[6]

In 1862, Lytton was promoted to Second Secretary in Vienna, but his success in Belgrade made Lord Russell appoint him, in 1863, as Secretary of the Legation at Copenhagen, during his tenure as which he twice acted as Chargé d'Affaires in the Schleswig-Holstein conflict.[6] In 1864, Lytton was transferred to the Greek court to advise the young Danish Prince. In 1865, he served in Lisbon, where he concluded a major commercial treaty with Portugal,[6] and subsequently in Madrid. He subsequently became Secretary to the Embassy at Vienna and, in 1872, to Richard Lyons, 1st Viscount Lyons, who was Ambassador to Paris.[6] By 1874, Lytton was appointed British Minister Plenipotentiary at Lisbon where he remained until being appointed Governor General and Viceroy of India in 1876.[6]

Viceroy of India (1876–1880)

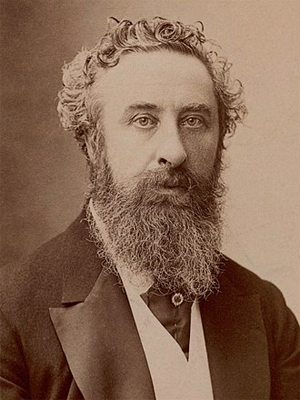

Edward Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton

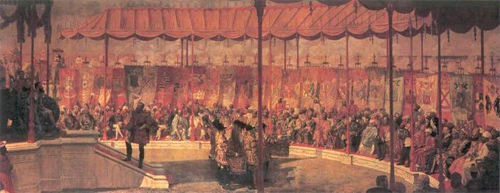

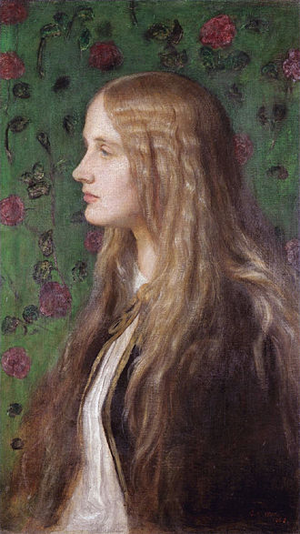

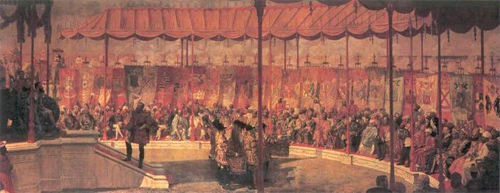

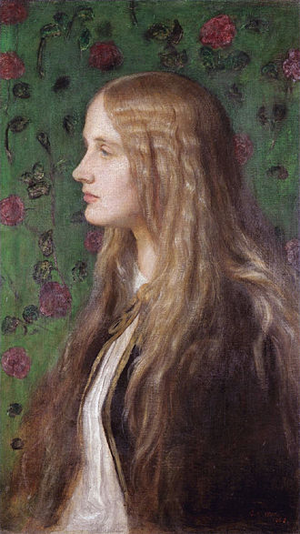

The Delhi Durbar of 1877 at Coronation Park. The Viceroy of India, Lord Lytton is seated on the dais to the left

Midway on his journey [to India] he met, by prearrangement, in Egypt, the Prince of Wales, then returning from his tour through India. Immediately on his arrival in Calcutta he was sworn in as Governor General and Viceroy, and on 1 January 1877, surrounded by all the Princes of Hindustan, he presided at a spectacular ceremony on the plains of Delhi, which marked the Proclamation of her Majesty, Queen Victoria, as Empress of India. After this the Queen conferred upon him the honor of the Grand Cross of the civil division of the Order of the Bath. In 1879 an attempt was made to assassinate Lord Lytton, but he escaped uninjured. The principal event of his viceroyalty was the Afghan war. (The New York Times, 1891)[6]

After turning down an appointment as governor of Madras,[5] Lytton was appointed Viceroy of India in 1875 and served from 1876 to 1880.[1] His tenure was controversial for its ruthlessness in both domestic and foreign affairs.[1] In 1877, Lord Lytton convened a durbar (imperial assembly) in Delhi that was attended by around 84,000 people, including Indian princes and noblemen. In 1878, he implemented the Vernacular Press Act, which enabled the Viceroy to confiscate the press and paper of any Indian Vernacular newspaper that published content that the Government deemed to be "seditious", in response to which there was a public protest in Calcutta that was led by the Indian Association and Surendranath Banerjee.

Lytton's son-in-law, Sir Edwin Lutyens, planned and designed New Delhi.

Indian Famine

Main article: Great Famine of 1876–78

Lord Lytton arrived as Viceroy of India in 1876. In the same year, a famine broke out in south India which claimed between 6.1 million and 10.3 million people.[7]

His implementation of Britain's trading policy has been blamed for increasing the severity of the famine.[7] Critics have contended that Lytton's belief in Social Darwinism determined his policy in response to the starving and dying Indians. He did, however, establish a commission to recommend ways to mitigate the threat of future famines, and he supported its recommendations when they were made in 1880.[5]

Second Anglo-Afghan War, 1878–1880

Main article: European influence in Afghanistan

Britain was deeply concerned throughout the 1870s about Russian attempts to increase its influence in Afghanistan, which provided a Central Asian buffer state between the Russian Empire and British India. Lytton had been given express instructions to recover the friendship of the Amir of Afghanistan, Sher Ali Khan, who was perceived at this point to have sided with Russia above Britain, and made every effort to do so for eighteen months.[5] In September 1878, Lytton sent the general Sir Neville Bowles Chamberlain as an emissary to Afghanistan, but he was refused entry. Considering himself left with no real alternative, in November 1878, Lytton ordered an invasion which sparked the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Britain won virtually all the major battles of this war, and in the final settlement, the Treaty of Gandamak, saw a government installed under a new amir which was both by personality and law receptive to British demands; however, the human and material costs and relative brutality of the brief guerrilla war (the war resulted in great loss of life on all sides, including civilians) provoked extensive controversy.[1] This, and the subsequent massacre of the residents of the Kabul representative Sir Louis Cavagnari and his staff,[5] contributed to the defeat of Disraeli's Conservative government by Gladstone's Liberals in 1880.[8]

The war was seen at the time as an ignominious but barely acceptable end to "the Great Game", closing a long chapter of conflict with the Russian Empire without even a proxy engagement. The Pyrrhic victory of British arms in India was a quiet embarrassment which played a small but critical role in the nascent scramble for Africa; in this way, Lytton and his war helped shape the contours of the 20th century in dramatic and unexpected ways. Lytton resigned at the same time as the Conservative government. He was the last Viceroy of India to govern an open frontier.

Commemoration

A permanent exhibition in Knebworth House, Hertfordshire, is dedicated to his diplomatic service in India.

Domestic politics

In 1880, Lytton resigned his Viceroyalty at the same time that Benjamin Disraeli resigned the premiership. Lytton was created Earl of Lytton, in the County of Derby, and Viscount Knebworth, of Knebworth in the County of Hertford.[6] On 10 January 1881, Lytton made his maiden speech in the House of Lords, in which he censured in Gladstone's devolutionist Afghan policy. In the summer session of 1881, Lytton joined others in opposing Gladstone's second Irish Land Bill.[9] As soon as the summer session was over, he undertook "a solitary ramble about the country". He visited Oxford for the first time, went for a trip on the Thames, and then revisited the hydropathic establishment at Malvern, where he had been with his father as a boy".[10] He saw this as an antidote to the otherwise indulgent lifestyle that came with his career, and used his sojourn there to undertake a critique of a new volume of poetry by his friend Wilfrid Blunt.[11]

Ambassador to Paris: 1887–1891

Lytton was Ambassador to France from 1887 to 1891. During the second half of the 1880s, before his appointment as Ambassador in 1887, Lytton served as Secretary to the Ambassador to Paris, Lord Lyons.[12] He succeeded Lyons, as Ambassador, subsequent to the resignation of Lyons in 1887.[12][6] Lytton had previously expressed an interest in the post and enjoyed himself "once more back in his old profession".[13]

Lord Lytton died in Paris on 24 November 1891, where he was given the rare honour of a state funeral. His body was then brought back for interment in the private family mausoleum in Knebworth Park.

Writings as "Owen Meredith"

The Right Honourable The Lord Lytton

When Lytton was twenty-five years old, he published in London a volume of poems under the name of Owen Meredith.[1] He went on to publish several other volumes under the same name. The most popular is Lucile, a story in verse published in 1860. His poetry was extremely popular and critically commended in his own day. He was a great experimenter with form. His best work is beautiful, and much of it is of a melancholy nature, as this short extract from a poem called "A Soul's Loss" shows, where the poet bids farewell to a lover who has betrayed him:

Child, I have no lips to chide thee./ Take the blessing of a heart/ (Never more to beat beside thee!)/ Which in blessing breaks. Depart./ Farewell! I that deified thee/ Dare not question what thou art.

Lytton underesteemed his poetic ability: in his Chronicles and Characters (1868), the poor response to which distressed him, Lytton states, 'Talk not of genius baffled. Genius is master of man./Genius does what it must, and Talent does what it can'.[1] However, Lytton's poetic ability was highly esteemed by other literary personalities of the day, and Oscar Wilde dedicated his play Lady Windermere's Fan to him.

Lytton's publications included:[6]

• Clytemnestra, The Earl's Return, The Artist and Other Poems (1855)[1]

• The Wanderer (1859), a Byron-esque lyric of Continental adventures that was popular on its release[1]

• Lucile (1860). Lytton was accused of plagiarizing George Sand's novel Lavinia for the story.[14][15]

• Serbski Pesme (1861). Plagiarized from a French translation of Serbian poems.[16][17]

• The Ring of Ainasis (1863)

• Fables in Song (1874)

• Speeches of Edward Lord Lytton with some of his Political Writingss, Hitherto unpublished, and a Prefactory Memoir by His Son (1874)

• The Life Letters and Literary Remains of Edward Bulwer, Lord Lytton (1883)

• Glenaveril (1885)

• After Paradise, or Legends of Exile (1887)

• King Poppy: A Story Without End (partially composed in early 1870s: only first published in 1892),[1] an allegorical romance in blank verse that was Lytton's favourite of his verse romances[1]

Vanity Fair Print 1875 editors text

Further reading

There is a detailed biography of Lytton by A. B. Harlan (1946).[1]

Marriage and children

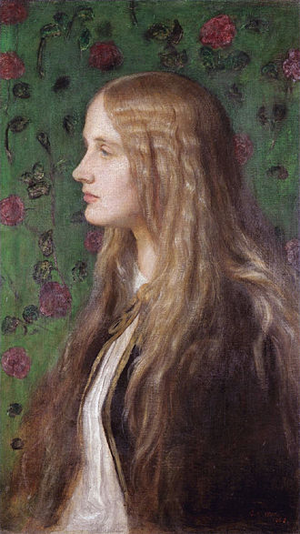

Edith Villiers, Countess of Lytton

On 4 October 1864 Lytton married Edith Villiers. She was the daughter of Edward Ernest Villiers (1806–1843) and Elizabeth Charlotte Liddell and the granddaughter of George Villiers.[18] In 1897, she was one of the guests at the Duchess of Devonshire's Diamond Jubilee Costume Ball.[19]

They had at least seven children:

• Edward Rowland John Bulwer-Lytton (1865–1871)

• Lady Elizabeth Edith "Betty" Bulwer-Lytton (12 June 1867 – 28 March 1942).[18] Married Gerald Balfour, 2nd Earl of Balfour, brother of Prime Minister Arthur Balfour.

• Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton (1869–1923)[18]

• Hon. Henry Meredith Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1872–1874)

• Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton (1874–1964). Married Edwin Lutyens. Associate of Krishnamurti

• Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton (1876–1947)[18]

• Neville Bulwer-Lytton, 3rd Earl of Lytton (6 February 1879 – 9 February 1951)[18]

References

1. Birch, Dinah (2009). The Oxford Companion to English Literature; Seventh Edition. OUP. p. 614.

2. Birch, Dinah (2009). The Oxford Companion to English Literature; Seventh Edition. OUP. p. 385.

3. Lady Lytton (1880). A Blighted Life. London: The London Publishing Office. Retrieved 28 November 2009. Online text at wikisource.org

4. Devey, Louisa (1887). Life of Rosina, Lady Lytton, with Numerous Extracts from her Ms. Autobiography and Other Original Documents, published in vindication of her memory. London: Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey & Co. Retrieved 28 November 2009. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

5. Stephen, Herbert (1911). "Lytton, Edward Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–187.

6. New York Times, 25 November 1891, Wednesday, Death of Lord Lytton—A Sudden Attack of Heart Disease in Paris—No Time for Assistance—His Long Career as a Diplomat in England's Service—His Literary Work as Owen Meredith

7. Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts. 1. Verso, 2000. ISBN 1-85984-739-0pg 7

8. David Washbrook, 'Lytton, Edward Robert Bulwer-, first earl of Lytton (1831–1891)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 29 September 2008

9. Balfour, Lady Betty, ed. (1906). Personal & Literary Letters of Robert First Earl of Lytton. Vol.2 of 2 (2nd ed.). London: Longmans, Green & Co. pp. 225–226. Retrieved 27 November 2009. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

10. Balfour, Lady Betty (1906) p.234

11. Balfour, Lady Betty (1906) pp.236–238

12. Jenkins, Brian. Lord Lyons: A Diplomat in an Age of Nationalism and War. McGill-Queen’s Press, 2014.

13. Balfour, Lady Betty (1906) pp.329–320

14. Bulwer-Lytton, V.A.G.R. (1913). The Life of Edward Bulwer: First Lord Lytton. 2. Macmillan and Company. p. 392.

15. "Mr. Owen Meredith's "Lucile"". The Literary Gazette. New Series. London. 140 (2300): 201–204. 2 March 1861.

16. "Owen Meredith". The Illustrated American. 9: 165. 12 December 1891.

17. "Robert Bulwer Lytton". The Brownings' Correspondence.

18. David Washbrook, 'Lytton, Edward Robert Bulwer-, first earl of Lytton (1831–1891)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 2 Nov 2015

19. Walker, Dave. "Costume Ball 4: Ladies only". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

External links

• Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl of Lytton

• Works by Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton at Internet Archive

• Works by Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• The LUCILE Project an academic effort to recover the publishing history of Lucile (which went through at least 2000 editions by nearly 100 publishers).

• His profile in ancestry.com

*************************

Edith Bulwer-Lytton, Countess of Lytton [Edith Villiers]

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/10/21

The Right Honourable, The Countess of Lytton

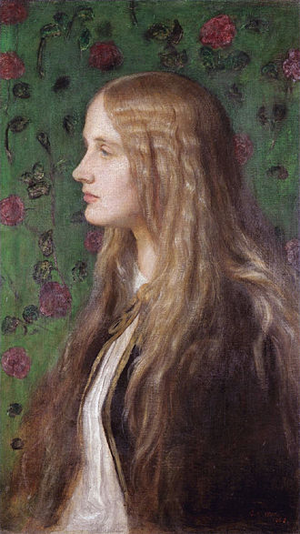

Portrait by George Frederic Watts (1862)

Born: Edith Villiers, 1841

Died: 17 September 1936 (aged 94–95)

Resting place: Knebworth[1]

Nationality: British

Other names: Edith Bulwer-Lytton, Lady Lytton

Known for: Vicereine of India

Spouse(s): Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton

Children: 7

Parent(s): Edward Ernest Villiers; Elizabeth Charlotte Liddell

Relatives: Villiers family

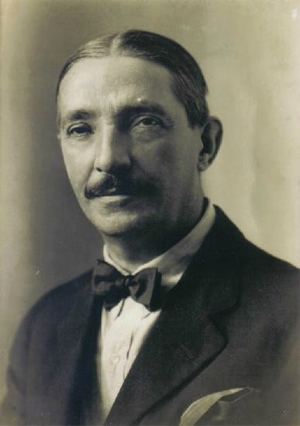

Edith Bulwer-Lytton, Countess of Lytton (née Villiers; 15 September 1841 – 17 September 1936) was a British aristocrat. Wife of Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton, she led the Indian Imperial court as Vicereine of India. She was later a court-attendant of Queen Victoria. Her children included the suffragette Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton.

Life

Edith Villiers was born on 15 September 1841, into the aristocratic Villiers family. She was the daughter of Edward Ernest Villiers (1806–1843) and Elizabeth Charlotte Liddell. She was the granddaughter of George Villiers,[1] and the niece of George Villiers, 4th Earl of Clarendon. The Pre-Raphaelite portrait of her by George Frederic Watts was painted when she was 21.[2] She was then the only unmarried daughter as her twin sister Elizabeth had married Henry Loch, 1st Baron Loch in 1862. (There is a tale that Henry proposed to the wrong girl by mistake and then refused to admit it.[2]) Edith was living with her widowed mother at the home of her uncle, the Earl of Clarendon. She had been trained in dancing, music and art, but she had not received a structured education.[2]

Villiers married Robert Bulwer-Lytton (later 1st Earl of Lytton) on 4 October 1864. She brought her new husband an income of £6,000 per year. Robert, an aspiring diplomat, was relatively poor for a member of the British upper classes, although his father Edward Bulwer-Lytton was a well-known writer and was raised to the peerage in 1866. His father controlled his son and it was his choice for his son to become a diplomat. Having previously broken up a match between Robert and another girl, he also disapproved of the marriage to Edith. For the first year he refused to speak to her but eventually warmed to the marriage.[3]

Edith accompanied her husband during his diplomatic career, and several of their children were born abroad. The children were:

• Edward Rowland John Bulwer-Lytton (1865–1871)

• Lady Elizabeth Edith "Betty" Bulwer-Lytton[1] (12 June 1867 – 28 March 1942) who married Gerald Balfour, 2nd Earl of Balfour

• Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton, born at Vienna (1869–1923),[1] British suffragette activist.

• Hon. Henry Meredith Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1872–1874)

• Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton (1874–1964) who married the architect Edwin Lutyens.

• Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton, (1876–1947)[1]

• Neville Bulwer-Lytton, 3rd Earl of Lytton (6 February 1879 – 9 February 1951)[1]

India

The Delhi Durbar of 1877. The Viceroy of India is seated on the dais to the left.

Her husband served as Viceroy of India between 1876 and 1880.[4] Edith would be the Vicereine.[5] In 1876 she gave birth at Shimla to her son Victor. He was the third of her sons but Edward and Henry had died as infants in 1871 and 1874. Victor and her last child Neville who was born in 1879 would in time inherit the Earldom.[1]

The Delhi Durbar of 1877 was held beginning on 1 January 1877 to proclaim Queen Victoria as Empress of India. The following year Edith, as Vicereine, was invested in the Imperial Order of the Crown of India.[6] Edith was also decorated with the honorific Lady, Royal Order of Victoria and Albert. Edith and her daughters restyled the court which they considered inferior to the courts of Europe. Fashions were ordered from Paris. Edith was noted for her support of the education of women in India.[1] Her daughter Emily retained an interest in Indian culture after the family's return to England and was converted to theosophy. When Edith's husband resigned in 1880 he was made an Earl by Benjamin Disraeli.[4]

Paris

Lady Edith Villiers dressed as Lady Melbourne for a costume party at Devonshire House[7] (1897)

Edith's husband became the British Ambassador in Paris in 1887 although he was weakened by heart disease. He seemed to make a good impression as when he died suddenly in Paris in 1891 he was given, unusually, a state funeral in France. Edith was the chief mourner along with her surviving five children. The funeral was attended by ministers of state and the French government arranged for 3,500 soldiers to serve at the funeral, before his body was taken by rail to England.[4]

At court

Edith had a much reduced income. She became Queen Victoria's Lady-in-Waiting (Lady of the Bedchamber) in 1895 taking the post left vacant by Susanna, Duchess of Roxburghe. She was asked personally by the Queen and she received £300 per year and served with eight other aristocratic maids of honour.[8] In 1897, she was one of the guests at the Duchess of Devonshire's Diamond Jubilee Costume Ball on 2 July 1897.[7]

When the Queen died, Edith rode with the body on the funeral journey from London to Windsor.[9] She then held the office of "Lady of the Bedchamber" to Queen Alexandra until she retired in 1905.[1]

Retirement

Her retirement lasted more than thirty years. She lived at Homewood, a dower house on the family estate at Knebworth, Hertfordshire. The house was designed c. 1901 by her son-in-law Sir Edwin Lutyens, in Arts and Crafts style.[10] Her daughter Constance suffered a stroke in 1912 and returned to live at Homewood,[11] remaining there until shortly before her death in 1923.[12]

Bibliography

Her granddaughter Mary Lutyens published a book Lady Lytton's Court Diary, based on Edith's experiences at the court of Queen Victoria.[13] Mary's other publications include The Lyttons in India: An account of Lord Lytton's Viceroyalty, 1876–1880.[14] Another granddaughter, Elisabeth Lutyens, mentioned Edith's life at Homewood when recalling her own childhood in her autobiography A Goldfish Bowl (1972).

Legacy

Edith and Robert had five children, who led influential lives. She also sat for the noted painting by George Frederic Watts. Some have deprecated her contribution as she had no formal education and her husband's biographers have thought her lightweight.[2]

References

1. Washbrook, D. (2008, January 03). Lytton, Edward Robert Bulwer-, first earl of Lytton [pseud. Owen Meredith (1831–1891), viceroy of India and poet]. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 6 Mar. 2020. Subscription or UK public library membership required.

2. Lyndsey Jenkins (12 March 2015). Lady Constance Lytton: Aristocrat, Suffragette, Martyr. Biteback Publishing. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-1-84954-892-2.

3. Leslie George Mitchell (2003). Bulwer Lytton: The Rise and Fall of a Victorian Man of Letters. A&C Black. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-1-85285-423-2.

4. Obituaries of Lord Lytton, Lucille Project, Retrieved 3 November 2015

5. Vicereine, Definition by OxfordDictionaries, Retrieved 3 November 2015

6. "No. 24539". The London Gazette. 4 January 1878. p. 113.

7. Walker, Dave. "Costume Ball 4: Ladies only". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

8. Greg King (4 June 2007). Twilight of Splendor: The Court of Queen Victoria During Her Diamond Jubilee Year. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-0-470-04439-1.

9. Votes for Women By June Purvis, Sandra Stanley Holton

10. Homewood, Knebworth http://www.parksandgardens.org.

11. Jenkins (2015), pp. 195–6.

12. Jenkins (2015), pp. 228–30.

13. Lady Lytton's Court Diary, 1895–1901. R. Hart-Davis. 1961.

14. London: John Murray, 1979, ISBN 0-7195-3677-4

External links

• Edith Bulwer-Lytton, ODNB (subscription or UK public library membership required)

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 11/3/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

-- Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton, by Wikipedia

-- A Strange Story, by Edward Bulwer Lytton

-- The Coming Race, by Edward Bulwer-Lytton

-- Zanoni: A Rosicrucian Tale, by Edward Bulwer Lytton

-- Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton, by Wikipedia

-- Edith Bulwer-Lytton, Countess of Lytton [Edith Villiers], by Wikipedia

-- Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton, by Wikipedia

His Excellency, The Right Honourable, The Earl of Lytton, GCB GCIE PC

Earl of Lytton, photo by Nadar

British Ambassador to France

In office: 1887–1891

Monarch: Queen Victoria

Preceded by: The Viscount Lyons

Succeeded by: The Marquess of Dufferin and Ava

Viceroy and Governor-General of India

In office: 12 April 1876 – 8 June 1880

Monarch: Queen Victoria

Preceded by: The Earl of Northbrook

Succeeded by: The Marquess of Ripon

Personal details

Born: 8 November 1831

Died: 24 November 1891 (aged 60)

Nationality: British

Political party: Conservative

Spouse(s): Edith Villiers

Children: 7

Parents: Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton; Rosina Doyle Wheeler

Education: Harrow School

Alma mater: University of Bonn

Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton, GCB, GCSI, GCIE, PC (8 November 1831 – 24 November 1891) was an English statesman, Conservative politician, and poet (who used the pseudonym Owen Meredith). He served as Viceroy of India between 1876 and 1880—during his tenure Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India—and as British Ambassador to France from 1887 to 1891.

His tenure as Viceroy was extremely successful, but controversial for its ruthlessness in both domestic and foreign affairs: especially for his response to the Great Famine of 1876–78, and the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Lytton's policies were alleged to be informed by his Social Darwinism. His son Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton, who was born in India, later served as Governor of Bengal and briefly as acting Viceroy, and he was the father-in-law of the architect Sir Edwin Lutyens, who designed New Delhi.

Lytton was a protégé of Benjamin Disraeli in domestic affairs, and of Richard Lyons, 1st Viscount Lyons, who was his predecessor as Ambassador to France, in foreign affairs. His tenure as Ambassador to Paris was successful, and Lytton was afforded the rare tribute – especially for an Englishman – of a French state funeral in Paris.

Childhood and education

Harrow School

Lytton was the son of the novelists Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton and Rosina Doyle Wheeler (who was the daughter of the early women's rights advocate Anna Wheeler). His uncle was Sir Henry Bulwer. His childhood was spoiled by the altercations of his parents,[1] who separated acrimoniously when he was a boy. However, Lytton received the patronage of John Forster - an influential friend of Leigh Hunt, Charles Lamb, Walter Savage Landor, and Charles Dickens - who was generally considered to be the first professional biographer of 19th century England.[2]

Lytton's mother, who lost access to her children, satirised his father in her 1839 novel Cheveley, or the Man of Honour. His father subsequently had his mother placed under restraint, as a consequence of an assertion of her insanity, which provoked public outcry and her liberation a few weeks later. His mother chronicled this episode in her memoirs.[3][4]

After being taught at home for a while, he was educated in schools in Twickenham and Brighton and thence Harrow,[5] and at the University of Bonn.[1]

Diplomatic career

Lytton entered the Diplomatic Service in 1849, when aged 18, when he was appointed as attaché to his uncle, Sir Henry Bulwer, who was Minister at Washington, DC.[6] It was at this time he met Henry Clay and Daniel Webster.[6] He began his salaried diplomatic career in 1852 as an attaché to Florence, and subsequently served in Paris, in 1854, and in The Hague, in 1856 .[6] In 1858, he served in St Petersburg, Constantinople, and Vienna.[6] In 1860, he was appointed British Consul General at Belgrade.[6]

In 1862, Lytton was promoted to Second Secretary in Vienna, but his success in Belgrade made Lord Russell appoint him, in 1863, as Secretary of the Legation at Copenhagen, during his tenure as which he twice acted as Chargé d'Affaires in the Schleswig-Holstein conflict.[6] In 1864, Lytton was transferred to the Greek court to advise the young Danish Prince. In 1865, he served in Lisbon, where he concluded a major commercial treaty with Portugal,[6] and subsequently in Madrid. He subsequently became Secretary to the Embassy at Vienna and, in 1872, to Richard Lyons, 1st Viscount Lyons, who was Ambassador to Paris.[6] By 1874, Lytton was appointed British Minister Plenipotentiary at Lisbon where he remained until being appointed Governor General and Viceroy of India in 1876.[6]

Viceroy of India (1876–1880)

Edward Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton

The Delhi Durbar of 1877 at Coronation Park. The Viceroy of India, Lord Lytton is seated on the dais to the left

Midway on his journey [to India] he met, by prearrangement, in Egypt, the Prince of Wales, then returning from his tour through India. Immediately on his arrival in Calcutta he was sworn in as Governor General and Viceroy, and on 1 January 1877, surrounded by all the Princes of Hindustan, he presided at a spectacular ceremony on the plains of Delhi, which marked the Proclamation of her Majesty, Queen Victoria, as Empress of India. After this the Queen conferred upon him the honor of the Grand Cross of the civil division of the Order of the Bath. In 1879 an attempt was made to assassinate Lord Lytton, but he escaped uninjured. The principal event of his viceroyalty was the Afghan war. (The New York Times, 1891)[6]

After turning down an appointment as governor of Madras,[5] Lytton was appointed Viceroy of India in 1875 and served from 1876 to 1880.[1] His tenure was controversial for its ruthlessness in both domestic and foreign affairs.[1] In 1877, Lord Lytton convened a durbar (imperial assembly) in Delhi that was attended by around 84,000 people, including Indian princes and noblemen. In 1878, he implemented the Vernacular Press Act, which enabled the Viceroy to confiscate the press and paper of any Indian Vernacular newspaper that published content that the Government deemed to be "seditious", in response to which there was a public protest in Calcutta that was led by the Indian Association and Surendranath Banerjee.

Lytton's son-in-law, Sir Edwin Lutyens, planned and designed New Delhi.

Indian Famine

Main article: Great Famine of 1876–78

Lord Lytton arrived as Viceroy of India in 1876. In the same year, a famine broke out in south India which claimed between 6.1 million and 10.3 million people.[7]

His implementation of Britain's trading policy has been blamed for increasing the severity of the famine.[7] Critics have contended that Lytton's belief in Social Darwinism determined his policy in response to the starving and dying Indians. He did, however, establish a commission to recommend ways to mitigate the threat of future famines, and he supported its recommendations when they were made in 1880.[5]

Second Anglo-Afghan War, 1878–1880

Main article: European influence in Afghanistan

Britain was deeply concerned throughout the 1870s about Russian attempts to increase its influence in Afghanistan, which provided a Central Asian buffer state between the Russian Empire and British India. Lytton had been given express instructions to recover the friendship of the Amir of Afghanistan, Sher Ali Khan, who was perceived at this point to have sided with Russia above Britain, and made every effort to do so for eighteen months.[5] In September 1878, Lytton sent the general Sir Neville Bowles Chamberlain as an emissary to Afghanistan, but he was refused entry. Considering himself left with no real alternative, in November 1878, Lytton ordered an invasion which sparked the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Britain won virtually all the major battles of this war, and in the final settlement, the Treaty of Gandamak, saw a government installed under a new amir which was both by personality and law receptive to British demands; however, the human and material costs and relative brutality of the brief guerrilla war (the war resulted in great loss of life on all sides, including civilians) provoked extensive controversy.[1] This, and the subsequent massacre of the residents of the Kabul representative Sir Louis Cavagnari and his staff,[5] contributed to the defeat of Disraeli's Conservative government by Gladstone's Liberals in 1880.[8]

The war was seen at the time as an ignominious but barely acceptable end to "the Great Game", closing a long chapter of conflict with the Russian Empire without even a proxy engagement. The Pyrrhic victory of British arms in India was a quiet embarrassment which played a small but critical role in the nascent scramble for Africa; in this way, Lytton and his war helped shape the contours of the 20th century in dramatic and unexpected ways. Lytton resigned at the same time as the Conservative government. He was the last Viceroy of India to govern an open frontier.

Commemoration

A permanent exhibition in Knebworth House, Hertfordshire, is dedicated to his diplomatic service in India.

Domestic politics

In 1880, Lytton resigned his Viceroyalty at the same time that Benjamin Disraeli resigned the premiership. Lytton was created Earl of Lytton, in the County of Derby, and Viscount Knebworth, of Knebworth in the County of Hertford.[6] On 10 January 1881, Lytton made his maiden speech in the House of Lords, in which he censured in Gladstone's devolutionist Afghan policy. In the summer session of 1881, Lytton joined others in opposing Gladstone's second Irish Land Bill.[9] As soon as the summer session was over, he undertook "a solitary ramble about the country". He visited Oxford for the first time, went for a trip on the Thames, and then revisited the hydropathic establishment at Malvern, where he had been with his father as a boy".[10] He saw this as an antidote to the otherwise indulgent lifestyle that came with his career, and used his sojourn there to undertake a critique of a new volume of poetry by his friend Wilfrid Blunt.[11]

Ambassador to Paris: 1887–1891

Lytton was Ambassador to France from 1887 to 1891. During the second half of the 1880s, before his appointment as Ambassador in 1887, Lytton served as Secretary to the Ambassador to Paris, Lord Lyons.[12] He succeeded Lyons, as Ambassador, subsequent to the resignation of Lyons in 1887.[12][6] Lytton had previously expressed an interest in the post and enjoyed himself "once more back in his old profession".[13]

Lord Lytton died in Paris on 24 November 1891, where he was given the rare honour of a state funeral. His body was then brought back for interment in the private family mausoleum in Knebworth Park.

Writings as "Owen Meredith"

The Right Honourable The Lord Lytton

When Lytton was twenty-five years old, he published in London a volume of poems under the name of Owen Meredith.[1] He went on to publish several other volumes under the same name. The most popular is Lucile, a story in verse published in 1860. His poetry was extremely popular and critically commended in his own day. He was a great experimenter with form. His best work is beautiful, and much of it is of a melancholy nature, as this short extract from a poem called "A Soul's Loss" shows, where the poet bids farewell to a lover who has betrayed him:

Child, I have no lips to chide thee./ Take the blessing of a heart/ (Never more to beat beside thee!)/ Which in blessing breaks. Depart./ Farewell! I that deified thee/ Dare not question what thou art.

Lytton underesteemed his poetic ability: in his Chronicles and Characters (1868), the poor response to which distressed him, Lytton states, 'Talk not of genius baffled. Genius is master of man./Genius does what it must, and Talent does what it can'.[1] However, Lytton's poetic ability was highly esteemed by other literary personalities of the day, and Oscar Wilde dedicated his play Lady Windermere's Fan to him.

Lytton's publications included:[6]

• Clytemnestra, The Earl's Return, The Artist and Other Poems (1855)[1]

• The Wanderer (1859), a Byron-esque lyric of Continental adventures that was popular on its release[1]

• Lucile (1860). Lytton was accused of plagiarizing George Sand's novel Lavinia for the story.[14][15]

• Serbski Pesme (1861). Plagiarized from a French translation of Serbian poems.[16][17]

• The Ring of Ainasis (1863)

• Fables in Song (1874)

• Speeches of Edward Lord Lytton with some of his Political Writingss, Hitherto unpublished, and a Prefactory Memoir by His Son (1874)

• The Life Letters and Literary Remains of Edward Bulwer, Lord Lytton (1883)

• Glenaveril (1885)

• After Paradise, or Legends of Exile (1887)

• King Poppy: A Story Without End (partially composed in early 1870s: only first published in 1892),[1] an allegorical romance in blank verse that was Lytton's favourite of his verse romances[1]

Vanity Fair Print 1875 editors text

Further reading

There is a detailed biography of Lytton by A. B. Harlan (1946).[1]

Marriage and children

Edith Villiers, Countess of Lytton

On 4 October 1864 Lytton married Edith Villiers. She was the daughter of Edward Ernest Villiers (1806–1843) and Elizabeth Charlotte Liddell and the granddaughter of George Villiers.[18] In 1897, she was one of the guests at the Duchess of Devonshire's Diamond Jubilee Costume Ball.[19]

They had at least seven children:

• Edward Rowland John Bulwer-Lytton (1865–1871)

• Lady Elizabeth Edith "Betty" Bulwer-Lytton (12 June 1867 – 28 March 1942).[18] Married Gerald Balfour, 2nd Earl of Balfour, brother of Prime Minister Arthur Balfour.

• Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton (1869–1923)[18]

• Hon. Henry Meredith Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1872–1874)

• Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton (1874–1964). Married Edwin Lutyens. Associate of Krishnamurti

• Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton (1876–1947)[18]

• Neville Bulwer-Lytton, 3rd Earl of Lytton (6 February 1879 – 9 February 1951)[18]

References

1. Birch, Dinah (2009). The Oxford Companion to English Literature; Seventh Edition. OUP. p. 614.

2. Birch, Dinah (2009). The Oxford Companion to English Literature; Seventh Edition. OUP. p. 385.

3. Lady Lytton (1880). A Blighted Life. London: The London Publishing Office. Retrieved 28 November 2009. Online text at wikisource.org

4. Devey, Louisa (1887). Life of Rosina, Lady Lytton, with Numerous Extracts from her Ms. Autobiography and Other Original Documents, published in vindication of her memory. London: Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey & Co. Retrieved 28 November 2009. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

5. Stephen, Herbert (1911). "Lytton, Edward Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–187.

6. New York Times, 25 November 1891, Wednesday, Death of Lord Lytton—A Sudden Attack of Heart Disease in Paris—No Time for Assistance—His Long Career as a Diplomat in England's Service—His Literary Work as Owen Meredith

7. Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts. 1. Verso, 2000. ISBN 1-85984-739-0pg 7

8. David Washbrook, 'Lytton, Edward Robert Bulwer-, first earl of Lytton (1831–1891)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 29 September 2008

9. Balfour, Lady Betty, ed. (1906). Personal & Literary Letters of Robert First Earl of Lytton. Vol.2 of 2 (2nd ed.). London: Longmans, Green & Co. pp. 225–226. Retrieved 27 November 2009. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

10. Balfour, Lady Betty (1906) p.234

11. Balfour, Lady Betty (1906) pp.236–238

12. Jenkins, Brian. Lord Lyons: A Diplomat in an Age of Nationalism and War. McGill-Queen’s Press, 2014.

13. Balfour, Lady Betty (1906) pp.329–320

14. Bulwer-Lytton, V.A.G.R. (1913). The Life of Edward Bulwer: First Lord Lytton. 2. Macmillan and Company. p. 392.

15. "Mr. Owen Meredith's "Lucile"". The Literary Gazette. New Series. London. 140 (2300): 201–204. 2 March 1861.

16. "Owen Meredith". The Illustrated American. 9: 165. 12 December 1891.

17. "Robert Bulwer Lytton". The Brownings' Correspondence.

18. David Washbrook, 'Lytton, Edward Robert Bulwer-, first earl of Lytton (1831–1891)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 2 Nov 2015

19. Walker, Dave. "Costume Ball 4: Ladies only". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

External links

• Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl of Lytton

• Works by Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton at Internet Archive

• Works by Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• The LUCILE Project an academic effort to recover the publishing history of Lucile (which went through at least 2000 editions by nearly 100 publishers).

• His profile in ancestry.com

*************************

Edith Bulwer-Lytton, Countess of Lytton [Edith Villiers]

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/10/21

The Right Honourable, The Countess of Lytton

Portrait by George Frederic Watts (1862)

Born: Edith Villiers, 1841

Died: 17 September 1936 (aged 94–95)

Resting place: Knebworth[1]

Nationality: British

Other names: Edith Bulwer-Lytton, Lady Lytton

Known for: Vicereine of India

Spouse(s): Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton

Children: 7

Parent(s): Edward Ernest Villiers; Elizabeth Charlotte Liddell

Relatives: Villiers family

Edith Bulwer-Lytton, Countess of Lytton (née Villiers; 15 September 1841 – 17 September 1936) was a British aristocrat. Wife of Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton, she led the Indian Imperial court as Vicereine of India. She was later a court-attendant of Queen Victoria. Her children included the suffragette Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton.

Life

Edith Villiers was born on 15 September 1841, into the aristocratic Villiers family. She was the daughter of Edward Ernest Villiers (1806–1843) and Elizabeth Charlotte Liddell. She was the granddaughter of George Villiers,[1] and the niece of George Villiers, 4th Earl of Clarendon. The Pre-Raphaelite portrait of her by George Frederic Watts was painted when she was 21.[2] She was then the only unmarried daughter as her twin sister Elizabeth had married Henry Loch, 1st Baron Loch in 1862. (There is a tale that Henry proposed to the wrong girl by mistake and then refused to admit it.[2]) Edith was living with her widowed mother at the home of her uncle, the Earl of Clarendon. She had been trained in dancing, music and art, but she had not received a structured education.[2]

Villiers married Robert Bulwer-Lytton (later 1st Earl of Lytton) on 4 October 1864. She brought her new husband an income of £6,000 per year. Robert, an aspiring diplomat, was relatively poor for a member of the British upper classes, although his father Edward Bulwer-Lytton was a well-known writer and was raised to the peerage in 1866. His father controlled his son and it was his choice for his son to become a diplomat. Having previously broken up a match between Robert and another girl, he also disapproved of the marriage to Edith. For the first year he refused to speak to her but eventually warmed to the marriage.[3]

Edith accompanied her husband during his diplomatic career, and several of their children were born abroad. The children were:

• Edward Rowland John Bulwer-Lytton (1865–1871)

• Lady Elizabeth Edith "Betty" Bulwer-Lytton[1] (12 June 1867 – 28 March 1942) who married Gerald Balfour, 2nd Earl of Balfour

• Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton, born at Vienna (1869–1923),[1] British suffragette activist.

• Hon. Henry Meredith Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1872–1874)

• Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton (1874–1964) who married the architect Edwin Lutyens.

• Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton, (1876–1947)[1]

• Neville Bulwer-Lytton, 3rd Earl of Lytton (6 February 1879 – 9 February 1951)[1]

India

The Delhi Durbar of 1877. The Viceroy of India is seated on the dais to the left.

Her husband served as Viceroy of India between 1876 and 1880.[4] Edith would be the Vicereine.[5] In 1876 she gave birth at Shimla to her son Victor. He was the third of her sons but Edward and Henry had died as infants in 1871 and 1874. Victor and her last child Neville who was born in 1879 would in time inherit the Earldom.[1]

The Delhi Durbar of 1877 was held beginning on 1 January 1877 to proclaim Queen Victoria as Empress of India. The following year Edith, as Vicereine, was invested in the Imperial Order of the Crown of India.[6] Edith was also decorated with the honorific Lady, Royal Order of Victoria and Albert. Edith and her daughters restyled the court which they considered inferior to the courts of Europe. Fashions were ordered from Paris. Edith was noted for her support of the education of women in India.[1] Her daughter Emily retained an interest in Indian culture after the family's return to England and was converted to theosophy. When Edith's husband resigned in 1880 he was made an Earl by Benjamin Disraeli.[4]

Paris

Lady Edith Villiers dressed as Lady Melbourne for a costume party at Devonshire House[7] (1897)

Edith's husband became the British Ambassador in Paris in 1887 although he was weakened by heart disease. He seemed to make a good impression as when he died suddenly in Paris in 1891 he was given, unusually, a state funeral in France. Edith was the chief mourner along with her surviving five children. The funeral was attended by ministers of state and the French government arranged for 3,500 soldiers to serve at the funeral, before his body was taken by rail to England.[4]

At court

Edith had a much reduced income. She became Queen Victoria's Lady-in-Waiting (Lady of the Bedchamber) in 1895 taking the post left vacant by Susanna, Duchess of Roxburghe. She was asked personally by the Queen and she received £300 per year and served with eight other aristocratic maids of honour.[8] In 1897, she was one of the guests at the Duchess of Devonshire's Diamond Jubilee Costume Ball on 2 July 1897.[7]

When the Queen died, Edith rode with the body on the funeral journey from London to Windsor.[9] She then held the office of "Lady of the Bedchamber" to Queen Alexandra until she retired in 1905.[1]

Retirement

Her retirement lasted more than thirty years. She lived at Homewood, a dower house on the family estate at Knebworth, Hertfordshire. The house was designed c. 1901 by her son-in-law Sir Edwin Lutyens, in Arts and Crafts style.[10] Her daughter Constance suffered a stroke in 1912 and returned to live at Homewood,[11] remaining there until shortly before her death in 1923.[12]

Bibliography

Her granddaughter Mary Lutyens published a book Lady Lytton's Court Diary, based on Edith's experiences at the court of Queen Victoria.[13] Mary's other publications include The Lyttons in India: An account of Lord Lytton's Viceroyalty, 1876–1880.[14] Another granddaughter, Elisabeth Lutyens, mentioned Edith's life at Homewood when recalling her own childhood in her autobiography A Goldfish Bowl (1972).

Legacy

Edith and Robert had five children, who led influential lives. She also sat for the noted painting by George Frederic Watts. Some have deprecated her contribution as she had no formal education and her husband's biographers have thought her lightweight.[2]

References

1. Washbrook, D. (2008, January 03). Lytton, Edward Robert Bulwer-, first earl of Lytton [pseud. Owen Meredith (1831–1891), viceroy of India and poet]. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 6 Mar. 2020. Subscription or UK public library membership required.

2. Lyndsey Jenkins (12 March 2015). Lady Constance Lytton: Aristocrat, Suffragette, Martyr. Biteback Publishing. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-1-84954-892-2.

3. Leslie George Mitchell (2003). Bulwer Lytton: The Rise and Fall of a Victorian Man of Letters. A&C Black. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-1-85285-423-2.

4. Obituaries of Lord Lytton, Lucille Project, Retrieved 3 November 2015

5. Vicereine, Definition by OxfordDictionaries, Retrieved 3 November 2015

6. "No. 24539". The London Gazette. 4 January 1878. p. 113.

7. Walker, Dave. "Costume Ball 4: Ladies only". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

8. Greg King (4 June 2007). Twilight of Splendor: The Court of Queen Victoria During Her Diamond Jubilee Year. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-0-470-04439-1.

9. Votes for Women By June Purvis, Sandra Stanley Holton

10. Homewood, Knebworth http://www.parksandgardens.org.

11. Jenkins (2015), pp. 195–6.

12. Jenkins (2015), pp. 228–30.

13. Lady Lytton's Court Diary, 1895–1901. R. Hart-Davis. 1961.

14. London: John Murray, 1979, ISBN 0-7195-3677-4

External links

• Edith Bulwer-Lytton, ODNB (subscription or UK public library membership required)