Re: D.T. Suzuki, Zen and the Nazis, by Brian Daizen Victoria

Part 1 of 2

Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D.T. Suzuki

by Brian Victoria

August 2, 2013

The Asia-Pacific Journal, Volume 11 | Issue 30 | Number 4

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

Introduction

The publication of Zen at War in 1997 and, to a lesser extent, Zen War Stories in 2003 sent shock waves through Zen Buddhist circles not only in Japan, but also in the U.S. and Europe.

These books revealed that many leading Zen masters and scholars, some of whom became well known in the West in the postwar era, had been vehement if not fanatical supporters of Japanese militarism. In the aftermath of these revelations, a number of branches of the Zen school, including the Myōshinji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect, acknowledged their war responsibility. A proclamation issued on 27 September 2001 by the Myōshinji General Assembly included the following passage:

On 19 October 2001 the sect’s branch administrators issued a follow-up statement:

In the same year, the smaller Tenryūji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect issued a similar statement, again citing the Japanese edition of Zen at War as a catalyst leading to their belated recognition of war responsibility.

In reading these apologies, one is reminded of the “Stuttgart Confession of Religious Guilt,” issued by Protestant church leaders in postwar Germany, in which they repented their support of Hitler and the Nazis. The Confession’s second paragraph read in part: “With great anguish we state: Through us has endless suffering been brought upon many peoples and countries. . . . We accuse ourselves for not witnessing more courageously, for not praying more faithfully, for not believing more joyously, and for not loving more ardently.”3 Nevertheless, there is one significant difference between religious leaders in Japan and Germany, i.e., while the Stuttgart Confession was also issued on 19 October, it was 19 October 1945 not 2001.

It is also true that a relatively small number of German Christians resisted the Nazis, Father Maximillian Kolbe, Martin Niemöller and Dietrich Bonhoeffer being among the best known. Similarly a small number of Buddhist priests, both within the Zen school and other sects, also opposed Japanese imperialism. The common denominator between the two groups, however, was their overall ineffectiveness.4 This is no doubt because no matter what the faith or country involved, institutional religion, with but few exceptions, staunchly supports its own nation in wartime.

The Background to D.T. Suzuki’s Wartime Role

There is now near universal recognition, including in Japan, that the Zen school, both Rinzai and Sōtō, strongly supported Japanese imperialism. Nevertheless, there is one Zen figure whose relationship to wartime Japan remains a subject of ongoing, sometimes deeply emotional, controversy: Daisetz Teitarō Suzuki, better known as D.T. Suzuki (1870-1966).5

Given Suzuki’s position as the most important figure in the introduction of Zen to the West, it is hardly surprising that the nature of his relationship to Japanese imperialism should prove controversial, for if he, too, were an imperialist supporter, what would this imply about the nature of the Zen he introduced to the West?

If the following discussion of Suzuki’s wartime record appears to lack balance, or shades of gray, it is not done out of ignorance, let alone denial, of exculpatory evidence concerning this period in his life. However, evidence of Suzuki’s alleged anti-war stance is well known and, indeed, readily accessible on the Internet.6 Hence, there is no need to repeat it here. That said, interested readers are encouraged to review all relevant materials related to Suzuki’s wartime record before reaching their own conclusions.

As important as Suzuki may be, the debate goes far beyond either the record or reputation of a single man. As recent scholarship suggests, Suzuki was in fact no more than one part, albeit a significant part, of a much larger movement. Oleg Benesch described Suzuki’s role as follows:

While these comments may not seem particularly controversial, Benesch also provided a detailed history of the manner in which Suzuki and other early twentieth century Japanese intellectuals, including such luminaries as Nitobe Inazō (1862-1933) and Inoue Tetsujirō (1855-1944), essentially invented a unified bushidō tradition for nationalist use both at home and abroad. Benesch writes:

Benesch later added:

As this article reveals, Suzuki’s writings on the newly created bushidō ‘code’ were very much a part of this larger nationalist discourse. His personal contribution to this discourse was the presentation of bushidō, primarily to a Western audience, as the very embodiment of Zen, including the modern Japanese soldier’s alleged “joyfulness of heart at the time of death.” In 1906, the year following Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, Suzuki wrote:

Suzuki’s praise for, and defense of, Japan’s soldiers as “Orientals” is particularly noteworthy in light of the fact that only two years earlier, i.e., in 1904, Suzuki had himself invoked Buddhism in attempting to convince Japanese youth to die willingly for their country: “Let us then shuffle off this mortal coil whenever it becomes necessary, and not raise a grunting voice against the fates. . . . Resting in this conviction, Buddhists carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying until they gain final victory.”11

While comments like these may be interpreted as Suzuki’s ad hoc responses to national events beyond his control, in fact they accurately represent his underlying belief in the appropriate role of religion in a Japan at war. This is clearly demonstrated by the following comments in the very first book Suzuki published in November 1896, entitled A Treatise on the New Meaning of Religion (Shin Shūkyō-ron):

The year 1896 is significant for two reasons, the first of which is that Suzuki’s book appeared in the immediate aftermath of Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War. This was not only Japan’s first major war abroad but, with the resultant acquisition of Taiwan, marked a major milestone in the growth of Japanese imperialism. Thus, Suzuki’s call for Japan’s religionists to resolutely support the state whenever it went to war could not have been more timely. At a personal level, it was also in December of that year, i.e., just one month after his book appeared, that Suzuki had his initial enlightenment experience (kenshō). This occurred at the time of his participation as a layman in an intensive meditation retreat (sesshin) at Engakuji in Kamakura, and shortly before his departure for more than a decade-long period of study and writing in the U.S. (1897-1908).

As Suzuki’s subsequent statements make clear, his kenshō experience did not alter his view of “religion during a [national] emergency.” Again, this is hardly surprising in light of the fact that Suzuki’s own Rinzai Zen master, Shaku Sōen [1860-1919], Engakuji’s abbot, was also a strong supporter of Japan’s war efforts.

In fact, Shaku’s support of Japan was so strong that during the Russo-Japanese War he volunteered to go to the battlefields in Manchuria as a military chaplain. Shaku explained: “. . . I also wished to inspire, if I could, our valiant soldiers with the ennobling thoughts of the Buddha, so as to enable them to die on the battlefield with the confidence that the task in which they are engaged is great and noble.”13

Once Japan had defeated Russia, its imperial rival, it immediately forced Korea to become a Japanese protectorate in November 1905. This was followed by Japan’s complete annexation of Korea in August 1910, thereby cementing the expansion of the Japanese empire onto the Asian continent. For his part, Suzuki avidly supported Japan’s takeover of Korea as revealed by comments he made in 1912 about that “poor country,” i.e., Korea, as he traversed it on his way to Europe via the Trans-Siberian railroad:

Suzuki’s comments reveal not only his support for Japanese colonialism but also his dismissal of the Korean people’s deep desire for independence. For Suzuki, the future of a poverty-stricken Korea depended on Japanese colonial beneficence.

While no doubt many if not most of Suzuki’s countrymen would have agreed with his position at the time, readers of Zen at War will recognize in both Suzuki and Shaku’s comments early examples of the jingoism that characterized Zen leaders’ war-related pronouncements through the end of the Asia-Pacific War in 1945. Not only did Suzuki admonish Buddhist soldiers to “carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying,” they were also directed “not to raise a grunting voice against the fates” as they “shuffle off this mortal coil.” In point of fact, approximately 47,000 young Japanese laid down their lives in the Russo-Japanese War exactly as Suzuki, Shaku and many other Buddhist leaders urged them to do.

The Background to Suzuki’s Article

While the preceding material introduces Suzuki’s attitude to the Russo-Japanese War and his country’s early colonial efforts, it fails to clarify his attitude toward Japan’s subsequent military activities, especially Japan’s aggression against China initiated by the Manchurian Incident of 1931. This aggression would continue and expand for a full fifteen years thereafter, i.e., until Japan’s defeat in August 1945. Suzuki did, however, write an article, “Bushidō to Zen” (Bushidō and Zen), that was included in a 1941 government-endorsed anthology entitled Bushidō no Shinzui (Essence of Bushidō). With additional articles contributed by leading army and navy figures, this book clearly sought to mobilize support for the war effort, both military and civilian. While not originally written for the book, the fact that Suzuki allowed his article to be included indicated at least a sympathetic attitude to this endeavor though it only indirectly referenced the war with China.15

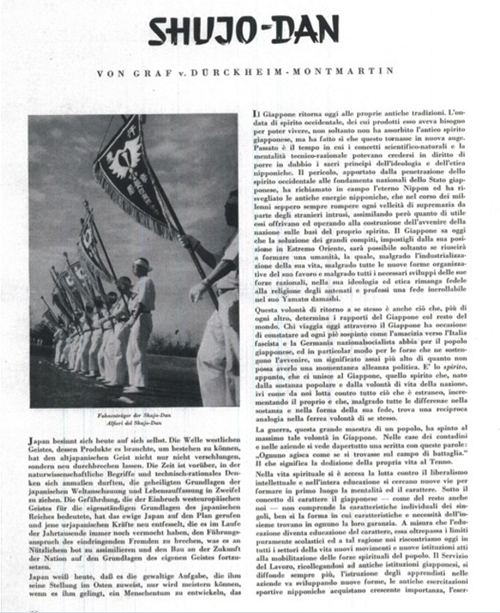

There is, however, yet another lengthy article that appeared in June 1941 in the Imperial Army’s premier journal for its officer corps. The journal, taking its name in part from its parent organization, was entitled: Kaikō-sha Kiji (Kaikō Association Report). Although not formally a government organization, the parent Kaikō-sha (lit. “let’s join the military together”) had been created in 1877 for the purpose of creating Imperial Army officers who were to be of “one mind and body.”16

The Kaikō Association Report was a monthly professional journal dating from July 1888. The journal contained articles on such topics as the latest developments in weaponry, mechanization and aviation but also featured yearly special editions devoted to such military events as the Russo-Japanese War and the Manchurian Incident of 1931. In addition, it regularly devoted substantial space to articles on “thought warfare” (shisō-sen), Japanese spirit (Yamato-damashii), national polity of Japan (kokutai), and “spiritual education” (seishin kyōiku), all key components of wartime ideology.

The journal’s ideological orientation can be seen in the articles that both preceded and followed Suzuki’s own contribution. The article preceding his was entitled “The Philosophical Basis of Spiritual Culture,” and included such statements as: “By comparison with Western laws based on rights, our laws are based on duties. By comparison with a [Western] world that operates according to individualism (kobetsusei), we have created a Japan that operates according to the principles of totality (zentaisei).”17 The article following his, entitled “Concerning the Indispensable Spiritual Elements of Military Aviators,” consisted of a speech by officer candidate Yamaguchi Bunji delivered at the graduation ceremony for the fifty-first class of the Japan Army Aviation Officer Candidate School on March 28, 1941.

As will be seen, Suzuki’s article fit in perfectly with the strong emphasis on “spirit” in this military journal. “Spiritual education” was one of the most important duties for Imperial Army officers. Officers were required to hold regular sessions with the troops under their command in order to introduce examples from Japanese history of the utterly loyal, fearless, and self-sacrificial warrior spirit. That the historical figures Suzuki introduced had acquired their fearlessness in the face of death through Zen practice was clearly welcomed by the journal’s editors, as it was by the leadership of the Imperial Army.18

The article was published in June 1941, i.e., less than six months before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. By then Japan had been fighting in China for four years, and while Japanese forces held most major Chinese cities, they were unable, to their great frustration, to either pacify the countryside or defeat the Nationalist and Communist forces deployed against them. The war was effectively stalemated, yet the death tolls, both Japanese and Chinese, continued to rise relentlessly as Japanese forces took the offensive in a bid to force surrender.

Suzuki Addresses Imperial Army Officers

Suzuki’s contribution took as its title the well-known Zen phrase: “Makujiki Kōzen,” i.e., Rush Forward Without Hesitation!19 Note that the complete English translation of Suzuki’s article is included in Appendix I. Some readers may wish to read the translation prior to reading the following commentary though this is not necessary. In addition, Appendix II contains the entire text of the original article in Japanese.

In the article’s opening paragraphs we find that Suzuki, like his Zen contemporaries, faced an awkward problem. That is to say, on the one hand he could not help but acknowledge that the Zen (Ch., Chan) school had come to fruition, if not created, in China, a country with which Japan had been at war for some four years. Given the massive death and destruction Japan’s invasion of China had caused, including its priceless Buddhist heritage, how could Japanese Zen leaders justify the ongoing destruction of the very country that had contributed so much to their school of Buddhism?

Suzuki addresses this issue by positing Japanese Zen’s superiority to Chinese Zen (Chan) Buddhism. That is to say, Suzuki notes that Zen’s “real efficacy” had only been realized after its arrival in Japan. One proof of this is that in Chinese monasteries meditation monitors use only one hand to hold a short ‘waking stick,’ while their Japanese counterparts hold long waking sticks with both hands just as warriors of old held their long single sword with both hands.

“The meaning of the fact that the waking stick is employed with two hands is that one is able to pour one’s entire strength into its use,” Suzuki claims.

Pouring one’s entire strength into the effort, whether it be waking a dozing meditator or cutting down an opponent, was, for Suzuki, the critical element that Zen and the warrior shared in common. There was no hint of an ethical distinction between the two. Nor did Suzuki acknowledge that in the Sōtō Zen sect, masters continue to employ the short, ‘Chinese-style’ waking stick (tansaku). This last omission is not surprising in that Suzuki typically either ignored, or dismissed, the practice and teachings of this sect.

Suzuki was, furthermore, not content with simply identifying the deficiencies in Chinese Zen, but went on to identify related deficiencies in the “world at large,” including Europe with its single-handed rapiers. That is to say, when non-Japanese fighters wield the sword they do so holding a sword in only one hand in order to hold a shield in the other hand. In so doing, they seek not only to slay their enemy but also to protect themselves, hoping to emerge both victorious and alive from the contest. By contrast, a Japanese warrior holds his sword with two hands because: “There is no attempt to defend oneself. There is only striking down the other.”

Was Suzuki accurate in his implied criticism of non-Japanese fighters for attempting to defend themselves in the midst of combat? While Suzuki didn’t name the “countries other than Japan” he was referring to, when discussing this question with undergraduates in my Japanese culture class, a student well versed in the history of European knighthood replied, “As far as Europe is concerned, there is a long history of employing duel-edged “long swords” with both hands just as in Japan. Further, if Japanese warriors were so unconcerned about their own lives, why did they develop what was at the time some of the strongest armor in the world to protect themselves?”

I had to agree with this student inasmuch as I had observed the same two-handed long swords when visiting the European sword exhibit housed in Edinburgh Castle in the spring of 2012. In any event, by elevating the alleged fearlessness of Japan’s warriors above that of their non-Japanese counterparts, Suzuki clearly demonstrates his nationalistic stance. A nationalism, it must be noted, that was deeply seeped in blood, both in the past and the war then underway.

It should also be noted that the Japanese military had long believed, dating from their victory in the Russo-Japanese War, that they could emerge victorious over a militarily superior (in terms of industrial capacity and weaponry) opponent. In this view, victory over a superior Western opponent, let alone China, was possible exactly because of the willingness of Japanese soldiers to die selflessly and unhesitatingly in battle. By contrast, the soldiers of other countries were seen as desiring nothing so much as to return home alive, thereby weakening their fighting spirit. Suzuki’s words could not have but lent credence to the Japanese military’s (over)confidence.

The themes introduced in his article, especially concerning the relationship of Zen to bushidō and samurai, are all topics that Suzuki had previously written about in both Japanese and English. For example, readers familiar with Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture (published in 1938 and reprinted in the postwar period as Zen and Japanese Culture) will recall that at the beginning of Chapter IV, “Zen and the Samurai,” Suzuki wrote:

While Suzuki’s officer readers probably would not have welcomed his reference to their “comparatively simple” military minds, the preceding quote nevertheless accurately summarizes the article under discussion here. And to his credit, unlike most other wartime Japanese Zen leaders, Suzuki did not actively incite his officer readers to carry on their violent profession. By contrast, for example, in 1943 Sōtō Zen master Yasutani Haku’un [1885–1973] wrote:

While these kinds of bellicose statements are notably absent from Suzuki’s writings, the current article, when read in its entirety, makes it clear that Suzuki did in fact seek to passively sustain Japan’s officers and men through his repeated advocacy of such things as “not look[ing] backward once the course is decided upon” and “treat[ing] life and death indifferently.” This leads to the question of just how different Suzuki was from someone like Yasutani given that Suzuki’s officer readers were also encouraged to “pour their entire body and mind into the attack” in the midst of an unprovoked invasion of China that resulted in the deaths of many millions of its citizens?

Even readers who haven’t served in the military can readily appreciate the fact that there are two fundamental questions that engulf a soldier’s mind prior to going into battle. First and foremost is the question of self-preservation, i.e., will I return alive? And a close second is - am I prepared to die if necessary? It is in answering the second question, i.e., in providing the mental preparation necessary for possible death, that a soldier’s religious faith is typically of paramount importance. Suzuki was well aware of this, for in promoting Zen training for warriors he wrote elsewhere: “Death now loses its sting altogether, and this is where the samurai training joins hands with Zen.”22

In short, read in its entirety Suzuki seeks in this article to prepare his officer readers, and through them ordinary soldiers, for death by weaponizing Zen, i.e., turning Zen into nothing less than a cult of death. The word ‘cult’ is used here to refer to one of its many meanings, i.e., a religious system devoted to only one thing -- death in this instance. On no less that six occasions throughout his article Suzuki stresses just how important being “prepared to die” (shineru) is, noting that Zen is “the best shortcut to acquire this frame of mind.”

Even if it could be demonstrated that this article was not written specifically for Japan’s Imperial Army officers, little would change, for there cannot be the slightest doubt that Suzuki’s words were intended for a wartime Japanese audience. This is made clear by Suzuki’s statement later in the article that “I think the extent of the crisis experienced then cannot be compared with the ordeal we are undergoing today.” As revealed in Zen at War, by 1941, if not before, all Japanese, young and old, civilian and military, were subject to a massive propaganda campaign, promulgated by government, Buddhist and educational leaders, to accept the death-embracing values of bushidō as their own. Or as expressed by Suzuki in this article: “. . . in undertaking any work one should be prepared to die.” (Italics mine)

Here, the question must be asked as to where this Zen shortcut to being prepared to die came from? Did it come from India, Buddhism’s birthplace, or China, Zen (Chan)’s sectarian home? It most definitely did not, for, as already noted, Suzuki tells us that Zen’s “real efficacy was supplied to a great extent after coming to Japan.” And as he further notes, it was only after arrival in Japan “that Zen became united with the sword.” Unlike the studied ambiguity that typically characterized his war and warrior-related writings in English, and oft-times in Japanese as well, Suzuki was clearly not speaking in this article of some metaphysical sword cutting through mental illusion.

Instead, Suzuki was referring to real swords wielded by some of Japan’s greatest Zen-trained warlords as, over the centuries, they and their subordinates cut through the flesh and bones of many thousands of their opponents on the battlefield, fully prepared to die in the process, using Zen as “the best shortcut to acquire this frame of mind.”

Interestingly, Suzuki admits in this article that some of the famous Zen-related anecdotes associated with Kamakura Regent Hōjō Tokimune (1251-84) may not have taken place.

He writes: “The following story has been handed down to us though I don’t know how much of this legend is actually true.” Compare this admission with Suzuki’s presentation of the same material in Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture. Addressing his English readers, Suzuki wrote that while the exchange between Tokimune and National Master Bukkō (1226-86) is “not quite authenticated,” it nevertheless “gives support to our imaginative reconstruction of his [Tokimune’s] attitude towards Zen.”23

One is left to speculate what Suzuki’s officer readers knew about these allegedly Zen-related anecdotes that his Western readers didn’t know (or perhaps more accurately, weren’t supposed to know).

In any event, when reading Suzuki’s repeated claims about the similarities between Zen and the Japanese, one is left to wonder whether it was Zen that shaped “the characteristics of the Japanese people” or, on the contrary, was it “the characteristics of the Japanese people” that shaped Zen? Or perhaps there was some mystical karmic connection that led both of them down the same path – a path in which to “rush forward without hesitation” and “cease discriminating thought” came to mean “one should abandon life and rush ahead”?

Furthermore, Suzuki is quite willing to privilege his fellow Japanese with a national character that almost inherently disposes them to Zen. For example, Suzuki claims “there are things about the Japanese character that are amazingly consistent with Zen.” That is to say, the Japanese people “rush forward to the heart of things without meandering about” and “go directly forward to that goal without looking either to the right or to the left.” In so doing they “forget where they are.”

If only in hindsight, in reading words like these, it is difficult not be reminded of the infamous and tactically futile “banzai charges” of the wartime Imperial Army let alone the tactics of kamikaze pilots and the manned torpedoes (kaiten) of the Imperial Navy.

Yet, is it fair to interpret Suzuki’s words as expressions of support for such suicidal acts?

One of Suzuki’s defenders who strongly opposes such an interpretation is Kemmyō Taira Satō, a Shin (True Pure Land) Buddhist priest who identifies himself as one of Suzuki’s postwar disciples. Satō writes: “Apart from his silence on Bushido after the early 1940s, Suzuki was active as an author during all of the war years, submitting to Buddhist journals numerous articles that conspicuously avoided mention of the ongoing conflict.” (Italics mine)

As further proof, Sato cites an article written by the noted Suzuki scholar Kirita Kiyohide:

On the one hand, these statements inevitably raise the question of Suzuki’s attitude to Japan’s attack on the U.S. in December 1941. That is to say, what was it that caused Suzuki to stop writing about such war-related topics as bushidō in the early 1940s? Could it have been his opposition to war with the U.S. versus his earlier support for Japan’s full-scale invasion of China from 1937 onwards? Setting this topic aside for further exploration below, the question remains, inasmuch as Suzuki, at least in June 1941, affirmed such things as the acceptability of a dog’s, i.e., meaningless, death, and noted that “in undertaking any work one should be prepared to die” what basis would he have had for opposing such suicidal attacks?

Yet another of Chan’s deficiencies is that in China, Chan had been almost entirely bereft of a military connection. By contrast, it was only after Chan became Zen in Japan that it was linked to Zen-practicing warriors. In fact, Suzuki claims that from the Kamakura period onwards, all Japanese warriors practiced Zen. Suzuki makes this claim despite the fact that the greatest of all Japan’s medieval warriors, i.e., Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), was an adherent of the Pure Land sect (J. Jōdo-shū) Buddhism, not Zen. Suzuki also urges his readers to pay special attention to the fact that “Zen became united with the sword” only after its arrival in Japan.

For Suzuki it was such great medieval warlords as Hōjō Tokimune, Uesugi Kenshin (1530-78), and Takeda Shingen (1521-73) who demonstrated the impact the unity of Zen and the sword had on the subsequent development of Japan. It was their Zen training that allowed these men to “rush forward without hesitation” and “cease discriminating thought.” If, in the case of Hōjō Tokimune, it can be said that at least his was a defensive war against invading Mongols, the same cannot be said for such warlords as Uesugi and Takeda. They were responsible for the deaths of thousands of their enemies and their own forces, each one of them attempting to conquer Japan. Suzuki lumps these warlords together as exemplars of what can be accomplished with the proper mental attitude acquired through Zen training. Suzuki does not even hint at the possibility that in the massive carnage these warlords collectively reaped, the Buddhist precept against the taking of life might have been violated.

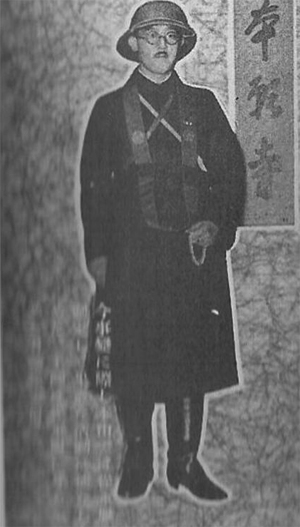

It is instructive here to compare Suzuki’s words with those of Japan’s most celebrated, Zen-trained “god of war” (gunshin) of the Asia-Pacific War. I refer to Lt. Col. Sugimoto Gorō, whose posthumous book, Taigi (Great Duty), first published in 1938, sold over a million copies, a far greater number than I first realized when writing Zen at War.

Sugimoto provided the following rationale for Zen’s importance to the Imperial military: “Through my practice of Zen I am able to get rid of my ego. In facilitating the accomplishment of this, Zen becomes, as it is, the true spirit of the Imperial military.”25 Suzuki was clearly in basic agreement with Sugimoto’s claim.

Suzuki argues that it isn’t sufficient to simply discard life and death. Instead, one should “live on the basis of something larger than life and death. That is to say, one must live on the basis of great affirmation.” But what did this “great affirmation” consist of? Suzuki fails to elaborate beyond stating that it is “faith that is great affirmation.” Yet, what should the object of one’s faith be?

Once again Suzuki remains silent on this critical question apart from stating that the way to encounter this great affirmation is to dig ever deeper to the bottom of one’s mind, digging until there is nothing left to dig. It was only then, he claims, that “one can, for the first time, encounter great affirmation.” Suzuki admits, however, that this great affirmation is not a single entity but “takes on various forms for the peoples of every country.” Yet, what form does or should it take in a Japan that had invaded and was fighting a long and bitter war with China?

As in many other instances of his wartime writings, and as alluded to above, Suzuki maintains a studied ambiguity that makes it impossible to state with certainty what he was referring to. That said, it is clear that nothing in his article would have served to dissuade his readers from fulfilling, let alone questioning, their duties as Imperial Army officers or soldiers in China or elsewhere. Had there been the slightest question that anything Suzuki wrote might have negatively impacted Imperial Army officers who were to be of “one mind and body,” it is inconceivable that the editors of the Kaikō Association Report would have published it.

In asserting this, let me express my appreciation to Sueki Fumihiko, one of Japan’s leading historians of modern Japanese Buddhism. In an article entitled “Daisetsu hihan saikō” (Rethinking Criticisms of Daisetsu [Suzuki]), Sueki first presented the arguments made by some of Suzuki’s most prominent defenders, namely, that when some of Suzuki’s wartime writings are closely parsed it is possible to interpret them as containing criticisms of the Imperial Army’s recklessness as well as its abuse of the alleged magnanimity and compassion of the true bushidō spirit. Further, Sueki acknowledges, as do I, that in the days leading up to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor Suzuki opposed war with the U.S. Nevertheless, Sueki came to the following conclusion: “When we frankly accept Suzuki’s words at face value, we must also consider how, in the midst of the [war] situation as it was then, his words would have been understood.”26

As for Suzuki’s opposition to war with the U.S., it is significant that his one and only public warning did not come until September 1941, i.e., only three months before Pearl Harbor. The unlikely occasion was a guest lecture Suzuki delivered at Kyoto University entitled “Zen and Japanese Culture.” Upon finishing his lecture, Suzuki initially stepped down from the podium but then returned to add:

As his words clearly reveal, Suzuki’s opposition to the approaching war with the U.S. had nothing to do with his Buddhist faith or a commitment to peace. Rather, having lived in America for more than a decade, Suzuki knew only too well that Japan was no match for such a large and powerful industrial nation. In short, Suzuki’s words might best be described as a statement of “common sense” though by 1941 this was clearly a commodity in short supply in Japan.

Be that as it may, when we ask how Suzuki’s Imperial Army officer readers would have interpreted the “great affirmation” he referred to, there can be no doubt they would have understood this to be an affirmation, if not an exhortation, for total loyalty unto death to an emperor who was held to be the divine embodiment of the state. The following calligraphic statement, displayed prominently in every Imperial Army barracks, testified to this: “We are the arms and legs of the emperor.” Due to its ubiquitous nature, Suzuki could not help but have been aware of this “affirmation.” Thus, whatever Suzuki’s personal opinion may have been, he would have been well aware that his officer readers would understand his words to mean absolute loyalty to the emperor.

Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that in one important aspect Suzuki did part way with other wartime Zen enthusiasts, for not withstanding his emphasis on “great affirmation,” Suzuki does not explicitly link Zen to the emperor. Compare this absence to the previously introduced Lt. Col. Sugimoto who wrote: “The reason that Zen is important for soldiers is that all Japanese, especially soldiers, must live in the spirit of the unity of sovereign and subjects, eliminating their ego and getting rid of their self. It is exactly the awakening to the nothingness (mu) of Zen that is the fundamental spirit of the unity of sovereign and subjects.”28

By not engaging in emperor adulation in his wartime writings, Suzuki was unique among his Zen contemporaries. Yet this does not mean that he either opposed the emperor system per se or lacked respect for the emperor. This is revealed by the following statement Suzuki made to Gerhard Rosenkrantz, a German missionary visiting Japan in 1939, in the library of Otani University:

Thus, even while denying the emperor’s divinity, Suzuki nevertheless justified bowing to the emperor’s image inasmuch he was a personage “in an area high above all religions.”

Nor should it be forgotten that Suzuki’s article was not written exclusively on behalf of Imperial Army officers alone. As previously noted, a key responsibility of the officer corps was to provide “spiritual education” for their soldiers. Thus, they were in constant need of additional historical examples of the attitude that all Imperial subjects, starting with Imperial soldiers, were expected to possess, i.e., an unquestioning, unhesitant and unthinking willingness to die in the war effort. Suzuki’s writings clearly contributed to this effort though it is, of course, impossible to quantify the impact his writings had.

Conclusion

Let me begin this section in something of an unusual manner, i.e., by offering a “defense” of what Suzuki has written in this and similar articles dealing with warriors, bushidō, and the alleged unity of Zen and the sword. That said, while a genuine defense is offered, it is one that nevertheless has a “hook in the tail.”

My contention is that Suzuki should not be blamed for having distorted or mischaracterized Zen history or practice, especially in Japan, to make it a useful tool in the hands of Japanese militarists. That is to say, on the one hand Suzuki can and should be held responsible for the purely nationalistic elements in his writings, including collaboration in the modern fabrication of an ancient and unified bushidō tradition with Zen as its core. Yet, on the other hand, the seven hundred year long history of the close relationship between Zen and the warrior class, hence Zen and the sword, was most definitely not a Suzuki fabrication. There are simply too many historical records of this close relationship to claim that Suzuki simply invented the relationship out of whole cloth.

Thus, Suzuki might best be described as a skilled, modern day, nationalistic proponent of that close relationship in the deadly context of Japan’s invasion of China. Further, in his English writings, Suzuki did his best to convince gullible Westerners that the so-called “unity of Zen and the sword” he described was an authentic expression of Buddhist teachings. In this effort, it must be said, Suzuki has been, at least until recently, eminently successful.

Some Suzuki scholars attempt to defend the most egregious aspects of Suzuki’s nationalist and wartime writings by pointing out that he may have been coerced into writing them by the then totalitarian state. Certainly, there can be no doubt that Suzuki wrote in an era of intense governmental censorship, with authorities ever vigilant against the slightest ideological deviancy. Nevertheless, the most striking features of Suzuki’s substantive wartime writings are, first of all, that they were never censored, and, secondly, their consistency with his earlier writings, dating back to 1896. That is to say, over a span of forty-five years Suzuki repeatedly yoked religion, Buddhism and Zen to the Japanese soldiers’ willingness to die. Certainly no one would claim that Suzuki was writing under fear of government censorship or imprisonment in 1896.

Where Suzuki did break with the past close relationship of Zen to the warrior class was in transmuting this feudal relationship into one encompassing Zen and the modern Japanese state albeit not specifically with the personage of the emperor. It is in having done this that he can rightly be identified as a “Zen nationalist.”30 Needless to say, he was only one of many such Zen leaders, and when compared with the likes of Yasutani Haku’un, Suzuki was clearly less extreme.31

When we inquire as to the cause or reason for the close relationship between Zen, violence, and the modern state that Suzuki promoted, the answer is not hard to find. In his book, Buddhism without Beliefs, Stephan Bachelor [Stephen Batchelor] provides the following explanation regarding not just Zen but all faiths, i.e., "the power of organized religion to provide sovereign states with a bulwark of moral legitimacy. . .”32 To which I would add in this instance, the power of Zen training to mentally prepare warriors/soldiers to both kill and be killed. Or as Suzuki would have it, to “passively sustain” them on the battlefield.

Having said this, I would ask readers to reflect on the historical relationship of their own faith, should they have one, to the state, and state-initiated violence. Was Batchelor correct in his observation with regard to the reader’s faith? That is to say, have not all of the world’s major religions, like Buddhism, provided moral legitimacy for the state’s use of violence? Is Buddhism unique in having done this or only one further example of Chicago University Martin Marty’s insightful comment that “one must note the feature of religion that keeps it on the front page and on prime time -- it kills”?33

To answer yes to any of these questions is not to excuse, let alone justify, Zen or any other school of Buddhism’s moral lapses in this or any instance. Yet, it does suggest the enormity of the problem facing all faiths if they are to remain true to their tenets, all of which number love and compassion among their highest ideals. At the end of his life Buddha Shakyamuni is recorded as having urged his followers to “work out your salvation with diligence.” In the face of continuing, if not increasing, religious violence in today’s world, is his advice any less relevant to all who, if only in terms of their own faith, seek to create a religion truly dedicated to world peace and our shared humanity?

Brian Daizen Victoria is a Visiting Research Fellow, International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken) in Kyoto, Japan.

Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D.T. Suzuki

by Brian Victoria

August 2, 2013

The Asia-Pacific Journal, Volume 11 | Issue 30 | Number 4

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Introduction

The publication of Zen at War in 1997 and, to a lesser extent, Zen War Stories in 2003 sent shock waves through Zen Buddhist circles not only in Japan, but also in the U.S. and Europe.

These books revealed that many leading Zen masters and scholars, some of whom became well known in the West in the postwar era, had been vehement if not fanatical supporters of Japanese militarism. In the aftermath of these revelations, a number of branches of the Zen school, including the Myōshinji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect, acknowledged their war responsibility. A proclamation issued on 27 September 2001 by the Myōshinji General Assembly included the following passage:

As we reflect on the recent events [of 11 September 2001] in the U.S. we recognize that in the past our country engaged in hostilities, calling it a “holy war,” and inflicting great pain and damage in various countries. Even though it was national policy at the time, it is truly regrettable that our sect, in the midst of wartime passions, was unable to maintain a resolute anti-war stance and ended up cooperating with the war effort. In light of this we wish to confess our past transgressions and critically reflect on our conduct.1

On 19 October 2001 the sect’s branch administrators issued a follow-up statement:

It was the publication of the book Zen to Sensō [i.e., the Japanese edition of Zen at War], etc. that provided the opportunity for us to address the issue of our war responsibility. It is truly a matter of regret that our sect has for so long been unable to seriously grapple with this issue. Still, due to the General Assembly’s adoption of its recent “Proclamation” we have been able to take the first step in addressing this issue. This is a very significant development.2

In the same year, the smaller Tenryūji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect issued a similar statement, again citing the Japanese edition of Zen at War as a catalyst leading to their belated recognition of war responsibility.

In reading these apologies, one is reminded of the “Stuttgart Confession of Religious Guilt,” issued by Protestant church leaders in postwar Germany, in which they repented their support of Hitler and the Nazis. The Confession’s second paragraph read in part: “With great anguish we state: Through us has endless suffering been brought upon many peoples and countries. . . . We accuse ourselves for not witnessing more courageously, for not praying more faithfully, for not believing more joyously, and for not loving more ardently.”3 Nevertheless, there is one significant difference between religious leaders in Japan and Germany, i.e., while the Stuttgart Confession was also issued on 19 October, it was 19 October 1945 not 2001.

It is also true that a relatively small number of German Christians resisted the Nazis, Father Maximillian Kolbe, Martin Niemöller and Dietrich Bonhoeffer being among the best known. Similarly a small number of Buddhist priests, both within the Zen school and other sects, also opposed Japanese imperialism. The common denominator between the two groups, however, was their overall ineffectiveness.4 This is no doubt because no matter what the faith or country involved, institutional religion, with but few exceptions, staunchly supports its own nation in wartime.

The Background to D.T. Suzuki’s Wartime Role

There is now near universal recognition, including in Japan, that the Zen school, both Rinzai and Sōtō, strongly supported Japanese imperialism. Nevertheless, there is one Zen figure whose relationship to wartime Japan remains a subject of ongoing, sometimes deeply emotional, controversy: Daisetz Teitarō Suzuki, better known as D.T. Suzuki (1870-1966).5

Given Suzuki’s position as the most important figure in the introduction of Zen to the West, it is hardly surprising that the nature of his relationship to Japanese imperialism should prove controversial, for if he, too, were an imperialist supporter, what would this imply about the nature of the Zen he introduced to the West?

If the following discussion of Suzuki’s wartime record appears to lack balance, or shades of gray, it is not done out of ignorance, let alone denial, of exculpatory evidence concerning this period in his life. However, evidence of Suzuki’s alleged anti-war stance is well known and, indeed, readily accessible on the Internet.6 Hence, there is no need to repeat it here. That said, interested readers are encouraged to review all relevant materials related to Suzuki’s wartime record before reaching their own conclusions.

As important as Suzuki may be, the debate goes far beyond either the record or reputation of a single man. As recent scholarship suggests, Suzuki was in fact no more than one part, albeit a significant part, of a much larger movement. Oleg Benesch described Suzuki’s role as follows:

[Suzuki’s] writings on bushidō and Zen during the period immediately after the Russo-Japanese War [1904-05] are not extensive, but are significant in light of his role in spreading the concept of the connection of Zen and bushidō, especially during the last four decades of his life. Suzuki can be seen as the most significant figure in this context, especially with regard to the dissemination of a Zen-based bushidō outside of Japan.7 (Italics mine)

While these comments may not seem particularly controversial, Benesch also provided a detailed history of the manner in which Suzuki and other early twentieth century Japanese intellectuals, including such luminaries as Nitobe Inazō (1862-1933) and Inoue Tetsujirō (1855-1944), essentially invented a unified bushidō tradition for nationalist use both at home and abroad. Benesch writes:

The development and dissemination of bushidō from the 1880s onward was an organic process initiated by a diverse group of thinkers who were more strongly influenced by the dominant Zeitgeist and Japan’s changing geopolitical position than by any traditional moral code. These individuals were concerned less with Japan’s past than the nation’s future, and their interest in bushidō was prompted primarily by their considerable exposure to the West, pronounced shifts in the popular perception of China, and an apprehensiveness regarding Japan’s relative strength among nations.8

Benesch later added:

The bushidō that developed in Meiji [1868-1912] was not a continuation of any earlier ethic, but it contained factual elements that were carefully selected and reinterpreted by its promoters. . . .concepts such as loyalty, self-sacrifice, duty, and honor, all of which existed in considerably different forms and contexts to those in which they were incorporated into modern bushidō theories. . . .The most important factor in the relatively rapid dissemination of bushidō was the growth of nationalistic sentiments around the time of the Sino-Japanese [1894-95] and Russo-Japanese wars.9

As this article reveals, Suzuki’s writings on the newly created bushidō ‘code’ were very much a part of this larger nationalist discourse. His personal contribution to this discourse was the presentation of bushidō, primarily to a Western audience, as the very embodiment of Zen, including the modern Japanese soldier’s alleged “joyfulness of heart at the time of death.” In 1906, the year following Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, Suzuki wrote:

The Lebensanschauung of Bushidō is no more nor less than that of Zen. The calmness and even joyfulness of heart at the moment of death which is conspicuously observable in the Japanese, the intrepidity which is generally shown by the Japanese soldiers in the face of an overwhelming enemy; and the fairness of play to an opponent, so strongly taught by Bushidō – all of these come from the spirit of the Zen training, and not from any such blind, fatalistic conception as is sometimes thought to be a trait peculiar to Orientals.10

Suzuki’s praise for, and defense of, Japan’s soldiers as “Orientals” is particularly noteworthy in light of the fact that only two years earlier, i.e., in 1904, Suzuki had himself invoked Buddhism in attempting to convince Japanese youth to die willingly for their country: “Let us then shuffle off this mortal coil whenever it becomes necessary, and not raise a grunting voice against the fates. . . . Resting in this conviction, Buddhists carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying until they gain final victory.”11

While comments like these may be interpreted as Suzuki’s ad hoc responses to national events beyond his control, in fact they accurately represent his underlying belief in the appropriate role of religion in a Japan at war. This is clearly demonstrated by the following comments in the very first book Suzuki published in November 1896, entitled A Treatise on the New Meaning of Religion (Shin Shūkyō-ron):

At the time of the commencement of hostilities with a foreign country, marines fight on the sea and soldiers fight in the fields, swords flashing and cannon smoke belching, moving this way and that. In so doing, our soldiers regard their own lives as being as light as goose feathers while their devotion to duty is as heavy as Mount Tai [in China]. Should they fall on the battlefield they have no regrets. This is what is called “religion during a [national] emergency.”12

The year 1896 is significant for two reasons, the first of which is that Suzuki’s book appeared in the immediate aftermath of Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War. This was not only Japan’s first major war abroad but, with the resultant acquisition of Taiwan, marked a major milestone in the growth of Japanese imperialism. Thus, Suzuki’s call for Japan’s religionists to resolutely support the state whenever it went to war could not have been more timely. At a personal level, it was also in December of that year, i.e., just one month after his book appeared, that Suzuki had his initial enlightenment experience (kenshō). This occurred at the time of his participation as a layman in an intensive meditation retreat (sesshin) at Engakuji in Kamakura, and shortly before his departure for more than a decade-long period of study and writing in the U.S. (1897-1908).

As Suzuki’s subsequent statements make clear, his kenshō experience did not alter his view of “religion during a [national] emergency.” Again, this is hardly surprising in light of the fact that Suzuki’s own Rinzai Zen master, Shaku Sōen [1860-1919], Engakuji’s abbot, was also a strong supporter of Japan’s war efforts.

In fact, Shaku’s support of Japan was so strong that during the Russo-Japanese War he volunteered to go to the battlefields in Manchuria as a military chaplain. Shaku explained: “. . . I also wished to inspire, if I could, our valiant soldiers with the ennobling thoughts of the Buddha, so as to enable them to die on the battlefield with the confidence that the task in which they are engaged is great and noble.”13

Once Japan had defeated Russia, its imperial rival, it immediately forced Korea to become a Japanese protectorate in November 1905. This was followed by Japan’s complete annexation of Korea in August 1910, thereby cementing the expansion of the Japanese empire onto the Asian continent. For his part, Suzuki avidly supported Japan’s takeover of Korea as revealed by comments he made in 1912 about that “poor country,” i.e., Korea, as he traversed it on his way to Europe via the Trans-Siberian railroad:

They [Koreans] don’t know how fortunate they are to have been returned to the hands of the Japanese government. It’s all well and good to talk independence and the like, but it’s useless for them to call for independence when they lack the capability and vitality to stand on their own. Looked at from the point of view of someone like myself who is just passing through, I think Korea ought to count the day that it was annexed to Japan as the day of its revival.14

Suzuki’s comments reveal not only his support for Japanese colonialism but also his dismissal of the Korean people’s deep desire for independence. For Suzuki, the future of a poverty-stricken Korea depended on Japanese colonial beneficence.

While no doubt many if not most of Suzuki’s countrymen would have agreed with his position at the time, readers of Zen at War will recognize in both Suzuki and Shaku’s comments early examples of the jingoism that characterized Zen leaders’ war-related pronouncements through the end of the Asia-Pacific War in 1945. Not only did Suzuki admonish Buddhist soldiers to “carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying,” they were also directed “not to raise a grunting voice against the fates” as they “shuffle off this mortal coil.” In point of fact, approximately 47,000 young Japanese laid down their lives in the Russo-Japanese War exactly as Suzuki, Shaku and many other Buddhist leaders urged them to do.

The Background to Suzuki’s Article

While the preceding material introduces Suzuki’s attitude to the Russo-Japanese War and his country’s early colonial efforts, it fails to clarify his attitude toward Japan’s subsequent military activities, especially Japan’s aggression against China initiated by the Manchurian Incident of 1931. This aggression would continue and expand for a full fifteen years thereafter, i.e., until Japan’s defeat in August 1945. Suzuki did, however, write an article, “Bushidō to Zen” (Bushidō and Zen), that was included in a 1941 government-endorsed anthology entitled Bushidō no Shinzui (Essence of Bushidō). With additional articles contributed by leading army and navy figures, this book clearly sought to mobilize support for the war effort, both military and civilian. While not originally written for the book, the fact that Suzuki allowed his article to be included indicated at least a sympathetic attitude to this endeavor though it only indirectly referenced the war with China.15

There is, however, yet another lengthy article that appeared in June 1941 in the Imperial Army’s premier journal for its officer corps. The journal, taking its name in part from its parent organization, was entitled: Kaikō-sha Kiji (Kaikō Association Report). Although not formally a government organization, the parent Kaikō-sha (lit. “let’s join the military together”) had been created in 1877 for the purpose of creating Imperial Army officers who were to be of “one mind and body.”16

The Kaikō Association Report was a monthly professional journal dating from July 1888. The journal contained articles on such topics as the latest developments in weaponry, mechanization and aviation but also featured yearly special editions devoted to such military events as the Russo-Japanese War and the Manchurian Incident of 1931. In addition, it regularly devoted substantial space to articles on “thought warfare” (shisō-sen), Japanese spirit (Yamato-damashii), national polity of Japan (kokutai), and “spiritual education” (seishin kyōiku), all key components of wartime ideology.

The journal’s ideological orientation can be seen in the articles that both preceded and followed Suzuki’s own contribution. The article preceding his was entitled “The Philosophical Basis of Spiritual Culture,” and included such statements as: “By comparison with Western laws based on rights, our laws are based on duties. By comparison with a [Western] world that operates according to individualism (kobetsusei), we have created a Japan that operates according to the principles of totality (zentaisei).”17 The article following his, entitled “Concerning the Indispensable Spiritual Elements of Military Aviators,” consisted of a speech by officer candidate Yamaguchi Bunji delivered at the graduation ceremony for the fifty-first class of the Japan Army Aviation Officer Candidate School on March 28, 1941.

As will be seen, Suzuki’s article fit in perfectly with the strong emphasis on “spirit” in this military journal. “Spiritual education” was one of the most important duties for Imperial Army officers. Officers were required to hold regular sessions with the troops under their command in order to introduce examples from Japanese history of the utterly loyal, fearless, and self-sacrificial warrior spirit. That the historical figures Suzuki introduced had acquired their fearlessness in the face of death through Zen practice was clearly welcomed by the journal’s editors, as it was by the leadership of the Imperial Army.18

The article was published in June 1941, i.e., less than six months before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. By then Japan had been fighting in China for four years, and while Japanese forces held most major Chinese cities, they were unable, to their great frustration, to either pacify the countryside or defeat the Nationalist and Communist forces deployed against them. The war was effectively stalemated, yet the death tolls, both Japanese and Chinese, continued to rise relentlessly as Japanese forces took the offensive in a bid to force surrender.

Suzuki Addresses Imperial Army Officers

Suzuki’s contribution took as its title the well-known Zen phrase: “Makujiki Kōzen,” i.e., Rush Forward Without Hesitation!19 Note that the complete English translation of Suzuki’s article is included in Appendix I. Some readers may wish to read the translation prior to reading the following commentary though this is not necessary. In addition, Appendix II contains the entire text of the original article in Japanese.

In the article’s opening paragraphs we find that Suzuki, like his Zen contemporaries, faced an awkward problem. That is to say, on the one hand he could not help but acknowledge that the Zen (Ch., Chan) school had come to fruition, if not created, in China, a country with which Japan had been at war for some four years. Given the massive death and destruction Japan’s invasion of China had caused, including its priceless Buddhist heritage, how could Japanese Zen leaders justify the ongoing destruction of the very country that had contributed so much to their school of Buddhism?

Suzuki addresses this issue by positing Japanese Zen’s superiority to Chinese Zen (Chan) Buddhism. That is to say, Suzuki notes that Zen’s “real efficacy” had only been realized after its arrival in Japan. One proof of this is that in Chinese monasteries meditation monitors use only one hand to hold a short ‘waking stick,’ while their Japanese counterparts hold long waking sticks with both hands just as warriors of old held their long single sword with both hands.

“The meaning of the fact that the waking stick is employed with two hands is that one is able to pour one’s entire strength into its use,” Suzuki claims.

Pouring one’s entire strength into the effort, whether it be waking a dozing meditator or cutting down an opponent, was, for Suzuki, the critical element that Zen and the warrior shared in common. There was no hint of an ethical distinction between the two. Nor did Suzuki acknowledge that in the Sōtō Zen sect, masters continue to employ the short, ‘Chinese-style’ waking stick (tansaku). This last omission is not surprising in that Suzuki typically either ignored, or dismissed, the practice and teachings of this sect.

Suzuki was, furthermore, not content with simply identifying the deficiencies in Chinese Zen, but went on to identify related deficiencies in the “world at large,” including Europe with its single-handed rapiers. That is to say, when non-Japanese fighters wield the sword they do so holding a sword in only one hand in order to hold a shield in the other hand. In so doing, they seek not only to slay their enemy but also to protect themselves, hoping to emerge both victorious and alive from the contest. By contrast, a Japanese warrior holds his sword with two hands because: “There is no attempt to defend oneself. There is only striking down the other.”

Was Suzuki accurate in his implied criticism of non-Japanese fighters for attempting to defend themselves in the midst of combat? While Suzuki didn’t name the “countries other than Japan” he was referring to, when discussing this question with undergraduates in my Japanese culture class, a student well versed in the history of European knighthood replied, “As far as Europe is concerned, there is a long history of employing duel-edged “long swords” with both hands just as in Japan. Further, if Japanese warriors were so unconcerned about their own lives, why did they develop what was at the time some of the strongest armor in the world to protect themselves?”

I had to agree with this student inasmuch as I had observed the same two-handed long swords when visiting the European sword exhibit housed in Edinburgh Castle in the spring of 2012. In any event, by elevating the alleged fearlessness of Japan’s warriors above that of their non-Japanese counterparts, Suzuki clearly demonstrates his nationalistic stance. A nationalism, it must be noted, that was deeply seeped in blood, both in the past and the war then underway.

It should also be noted that the Japanese military had long believed, dating from their victory in the Russo-Japanese War, that they could emerge victorious over a militarily superior (in terms of industrial capacity and weaponry) opponent. In this view, victory over a superior Western opponent, let alone China, was possible exactly because of the willingness of Japanese soldiers to die selflessly and unhesitatingly in battle. By contrast, the soldiers of other countries were seen as desiring nothing so much as to return home alive, thereby weakening their fighting spirit. Suzuki’s words could not have but lent credence to the Japanese military’s (over)confidence.

The themes introduced in his article, especially concerning the relationship of Zen to bushidō and samurai, are all topics that Suzuki had previously written about in both Japanese and English. For example, readers familiar with Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture (published in 1938 and reprinted in the postwar period as Zen and Japanese Culture) will recall that at the beginning of Chapter IV, “Zen and the Samurai,” Suzuki wrote:

In Japan, Zen was intimately related from the beginning of its history to the life of the samurai. Although it has never actively incited them to carry on their violent profession, it has passively sustained them when they have for whatever reason once entered into it. Zen has sustained them in two ways, morally and philosophically. Morally, because Zen is a religion which teaches us not to look backward once the course is decided upon; philosophically because it treats life and death indifferently. . . . Therefore, morally and philosophically, there is in Zen a great deal of attraction for the military classes. The military mind, being – and this is one of the essential qualities of the fighter – comparatively simple and not at all addicted to philosophizing finds a congenial spirit in Zen. This is probably one of the main reasons for the close relationship between Zen and the samurai.20 (Italics mine)

While Suzuki’s officer readers probably would not have welcomed his reference to their “comparatively simple” military minds, the preceding quote nevertheless accurately summarizes the article under discussion here. And to his credit, unlike most other wartime Japanese Zen leaders, Suzuki did not actively incite his officer readers to carry on their violent profession. By contrast, for example, in 1943 Sōtō Zen master Yasutani Haku’un [1885–1973] wrote:

Of course one should kill, killing as many as possible. One should, fighting hard, kill every one in the enemy army. The reason for this is that in order to carry [Buddhist] compassion and filial obedience through to perfection it is necessary to assist good and punish evil. . . . Failing to kill an evil man who ought to be killed, or destroying an enemy army that ought to be destroyed, would be to betray compassion and filial obedience, to break the precept forbidding the taking of life. This is a special characteristic of the Mahāyāna precepts.21

While these kinds of bellicose statements are notably absent from Suzuki’s writings, the current article, when read in its entirety, makes it clear that Suzuki did in fact seek to passively sustain Japan’s officers and men through his repeated advocacy of such things as “not look[ing] backward once the course is decided upon” and “treat[ing] life and death indifferently.” This leads to the question of just how different Suzuki was from someone like Yasutani given that Suzuki’s officer readers were also encouraged to “pour their entire body and mind into the attack” in the midst of an unprovoked invasion of China that resulted in the deaths of many millions of its citizens?

Even readers who haven’t served in the military can readily appreciate the fact that there are two fundamental questions that engulf a soldier’s mind prior to going into battle. First and foremost is the question of self-preservation, i.e., will I return alive? And a close second is - am I prepared to die if necessary? It is in answering the second question, i.e., in providing the mental preparation necessary for possible death, that a soldier’s religious faith is typically of paramount importance. Suzuki was well aware of this, for in promoting Zen training for warriors he wrote elsewhere: “Death now loses its sting altogether, and this is where the samurai training joins hands with Zen.”22

In short, read in its entirety Suzuki seeks in this article to prepare his officer readers, and through them ordinary soldiers, for death by weaponizing Zen, i.e., turning Zen into nothing less than a cult of death. The word ‘cult’ is used here to refer to one of its many meanings, i.e., a religious system devoted to only one thing -- death in this instance. On no less that six occasions throughout his article Suzuki stresses just how important being “prepared to die” (shineru) is, noting that Zen is “the best shortcut to acquire this frame of mind.”

Even if it could be demonstrated that this article was not written specifically for Japan’s Imperial Army officers, little would change, for there cannot be the slightest doubt that Suzuki’s words were intended for a wartime Japanese audience. This is made clear by Suzuki’s statement later in the article that “I think the extent of the crisis experienced then cannot be compared with the ordeal we are undergoing today.” As revealed in Zen at War, by 1941, if not before, all Japanese, young and old, civilian and military, were subject to a massive propaganda campaign, promulgated by government, Buddhist and educational leaders, to accept the death-embracing values of bushidō as their own. Or as expressed by Suzuki in this article: “. . . in undertaking any work one should be prepared to die.” (Italics mine)

Here, the question must be asked as to where this Zen shortcut to being prepared to die came from? Did it come from India, Buddhism’s birthplace, or China, Zen (Chan)’s sectarian home? It most definitely did not, for, as already noted, Suzuki tells us that Zen’s “real efficacy was supplied to a great extent after coming to Japan.” And as he further notes, it was only after arrival in Japan “that Zen became united with the sword.” Unlike the studied ambiguity that typically characterized his war and warrior-related writings in English, and oft-times in Japanese as well, Suzuki was clearly not speaking in this article of some metaphysical sword cutting through mental illusion.

Instead, Suzuki was referring to real swords wielded by some of Japan’s greatest Zen-trained warlords as, over the centuries, they and their subordinates cut through the flesh and bones of many thousands of their opponents on the battlefield, fully prepared to die in the process, using Zen as “the best shortcut to acquire this frame of mind.”

Interestingly, Suzuki admits in this article that some of the famous Zen-related anecdotes associated with Kamakura Regent Hōjō Tokimune (1251-84) may not have taken place.

He writes: “The following story has been handed down to us though I don’t know how much of this legend is actually true.” Compare this admission with Suzuki’s presentation of the same material in Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture. Addressing his English readers, Suzuki wrote that while the exchange between Tokimune and National Master Bukkō (1226-86) is “not quite authenticated,” it nevertheless “gives support to our imaginative reconstruction of his [Tokimune’s] attitude towards Zen.”23

One is left to speculate what Suzuki’s officer readers knew about these allegedly Zen-related anecdotes that his Western readers didn’t know (or perhaps more accurately, weren’t supposed to know).

In any event, when reading Suzuki’s repeated claims about the similarities between Zen and the Japanese, one is left to wonder whether it was Zen that shaped “the characteristics of the Japanese people” or, on the contrary, was it “the characteristics of the Japanese people” that shaped Zen? Or perhaps there was some mystical karmic connection that led both of them down the same path – a path in which to “rush forward without hesitation” and “cease discriminating thought” came to mean “one should abandon life and rush ahead”?

Furthermore, Suzuki is quite willing to privilege his fellow Japanese with a national character that almost inherently disposes them to Zen. For example, Suzuki claims “there are things about the Japanese character that are amazingly consistent with Zen.” That is to say, the Japanese people “rush forward to the heart of things without meandering about” and “go directly forward to that goal without looking either to the right or to the left.” In so doing they “forget where they are.”

If only in hindsight, in reading words like these, it is difficult not be reminded of the infamous and tactically futile “banzai charges” of the wartime Imperial Army let alone the tactics of kamikaze pilots and the manned torpedoes (kaiten) of the Imperial Navy.

Yet, is it fair to interpret Suzuki’s words as expressions of support for such suicidal acts?

One of Suzuki’s defenders who strongly opposes such an interpretation is Kemmyō Taira Satō, a Shin (True Pure Land) Buddhist priest who identifies himself as one of Suzuki’s postwar disciples. Satō writes: “Apart from his silence on Bushido after the early 1940s, Suzuki was active as an author during all of the war years, submitting to Buddhist journals numerous articles that conspicuously avoided mention of the ongoing conflict.” (Italics mine)

As further proof, Sato cites an article written by the noted Suzuki scholar Kirita Kiyohide:

During this [war] period one of the journals Suzuki contributed to frequently, Daijōzen [Mahayana Zen], fairly bristled with pro-militarist articles. In issues filled with essays proclaiming “Victory in the Holy War!” and bearing such titles as “Death Is the Last Battle,” “Certain Victory for Kamikaze and Torpedoes,” and “The Noble Sacrifice of a Hundred Million,” Suzuki continued with contributions on subjects like “Zen and Culture.”24

On the one hand, these statements inevitably raise the question of Suzuki’s attitude to Japan’s attack on the U.S. in December 1941. That is to say, what was it that caused Suzuki to stop writing about such war-related topics as bushidō in the early 1940s? Could it have been his opposition to war with the U.S. versus his earlier support for Japan’s full-scale invasion of China from 1937 onwards? Setting this topic aside for further exploration below, the question remains, inasmuch as Suzuki, at least in June 1941, affirmed such things as the acceptability of a dog’s, i.e., meaningless, death, and noted that “in undertaking any work one should be prepared to die” what basis would he have had for opposing such suicidal attacks?

Yet another of Chan’s deficiencies is that in China, Chan had been almost entirely bereft of a military connection. By contrast, it was only after Chan became Zen in Japan that it was linked to Zen-practicing warriors. In fact, Suzuki claims that from the Kamakura period onwards, all Japanese warriors practiced Zen. Suzuki makes this claim despite the fact that the greatest of all Japan’s medieval warriors, i.e., Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), was an adherent of the Pure Land sect (J. Jōdo-shū) Buddhism, not Zen. Suzuki also urges his readers to pay special attention to the fact that “Zen became united with the sword” only after its arrival in Japan.

For Suzuki it was such great medieval warlords as Hōjō Tokimune, Uesugi Kenshin (1530-78), and Takeda Shingen (1521-73) who demonstrated the impact the unity of Zen and the sword had on the subsequent development of Japan. It was their Zen training that allowed these men to “rush forward without hesitation” and “cease discriminating thought.” If, in the case of Hōjō Tokimune, it can be said that at least his was a defensive war against invading Mongols, the same cannot be said for such warlords as Uesugi and Takeda. They were responsible for the deaths of thousands of their enemies and their own forces, each one of them attempting to conquer Japan. Suzuki lumps these warlords together as exemplars of what can be accomplished with the proper mental attitude acquired through Zen training. Suzuki does not even hint at the possibility that in the massive carnage these warlords collectively reaped, the Buddhist precept against the taking of life might have been violated.

It is instructive here to compare Suzuki’s words with those of Japan’s most celebrated, Zen-trained “god of war” (gunshin) of the Asia-Pacific War. I refer to Lt. Col. Sugimoto Gorō, whose posthumous book, Taigi (Great Duty), first published in 1938, sold over a million copies, a far greater number than I first realized when writing Zen at War.

Sugimoto provided the following rationale for Zen’s importance to the Imperial military: “Through my practice of Zen I am able to get rid of my ego. In facilitating the accomplishment of this, Zen becomes, as it is, the true spirit of the Imperial military.”25 Suzuki was clearly in basic agreement with Sugimoto’s claim.

Suzuki argues that it isn’t sufficient to simply discard life and death. Instead, one should “live on the basis of something larger than life and death. That is to say, one must live on the basis of great affirmation.” But what did this “great affirmation” consist of? Suzuki fails to elaborate beyond stating that it is “faith that is great affirmation.” Yet, what should the object of one’s faith be?

Once again Suzuki remains silent on this critical question apart from stating that the way to encounter this great affirmation is to dig ever deeper to the bottom of one’s mind, digging until there is nothing left to dig. It was only then, he claims, that “one can, for the first time, encounter great affirmation.” Suzuki admits, however, that this great affirmation is not a single entity but “takes on various forms for the peoples of every country.” Yet, what form does or should it take in a Japan that had invaded and was fighting a long and bitter war with China?

As in many other instances of his wartime writings, and as alluded to above, Suzuki maintains a studied ambiguity that makes it impossible to state with certainty what he was referring to. That said, it is clear that nothing in his article would have served to dissuade his readers from fulfilling, let alone questioning, their duties as Imperial Army officers or soldiers in China or elsewhere. Had there been the slightest question that anything Suzuki wrote might have negatively impacted Imperial Army officers who were to be of “one mind and body,” it is inconceivable that the editors of the Kaikō Association Report would have published it.

In asserting this, let me express my appreciation to Sueki Fumihiko, one of Japan’s leading historians of modern Japanese Buddhism. In an article entitled “Daisetsu hihan saikō” (Rethinking Criticisms of Daisetsu [Suzuki]), Sueki first presented the arguments made by some of Suzuki’s most prominent defenders, namely, that when some of Suzuki’s wartime writings are closely parsed it is possible to interpret them as containing criticisms of the Imperial Army’s recklessness as well as its abuse of the alleged magnanimity and compassion of the true bushidō spirit. Further, Sueki acknowledges, as do I, that in the days leading up to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor Suzuki opposed war with the U.S. Nevertheless, Sueki came to the following conclusion: “When we frankly accept Suzuki’s words at face value, we must also consider how, in the midst of the [war] situation as it was then, his words would have been understood.”26

As for Suzuki’s opposition to war with the U.S., it is significant that his one and only public warning did not come until September 1941, i.e., only three months before Pearl Harbor. The unlikely occasion was a guest lecture Suzuki delivered at Kyoto University entitled “Zen and Japanese Culture.” Upon finishing his lecture, Suzuki initially stepped down from the podium but then returned to add:

Japan must evaluate more calmly and accurately the awesome reality of America’s industrial productivity. Present-day wars will no longer be determined as in the past by military strategy and tactics, courage and fearlessness alone. This is because of the large role now played by production capacity and mechanical power. 27

As his words clearly reveal, Suzuki’s opposition to the approaching war with the U.S. had nothing to do with his Buddhist faith or a commitment to peace. Rather, having lived in America for more than a decade, Suzuki knew only too well that Japan was no match for such a large and powerful industrial nation. In short, Suzuki’s words might best be described as a statement of “common sense” though by 1941 this was clearly a commodity in short supply in Japan.

Be that as it may, when we ask how Suzuki’s Imperial Army officer readers would have interpreted the “great affirmation” he referred to, there can be no doubt they would have understood this to be an affirmation, if not an exhortation, for total loyalty unto death to an emperor who was held to be the divine embodiment of the state. The following calligraphic statement, displayed prominently in every Imperial Army barracks, testified to this: “We are the arms and legs of the emperor.” Due to its ubiquitous nature, Suzuki could not help but have been aware of this “affirmation.” Thus, whatever Suzuki’s personal opinion may have been, he would have been well aware that his officer readers would understand his words to mean absolute loyalty to the emperor.

Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that in one important aspect Suzuki did part way with other wartime Zen enthusiasts, for not withstanding his emphasis on “great affirmation,” Suzuki does not explicitly link Zen to the emperor. Compare this absence to the previously introduced Lt. Col. Sugimoto who wrote: “The reason that Zen is important for soldiers is that all Japanese, especially soldiers, must live in the spirit of the unity of sovereign and subjects, eliminating their ego and getting rid of their self. It is exactly the awakening to the nothingness (mu) of Zen that is the fundamental spirit of the unity of sovereign and subjects.”28