Re: Neuschwanstein: A fairy tale darling's dark Nazi past

Hubertus Strughold

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/27/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

Hubertus Strughold

Born June 15, 1898

Westtünnen-im-Hamm, Westphalia, Germany

Died September 25, 1986 (aged 88)

San Antonio, Texas, United States

Citizenship German and American (1956)

Alma mater Georg August University of Göttingen; University of Würzburg

Known for Space medicine, Nazi human experimentation

Scientific career

Fields Aviation medicine, space medicine, physiology

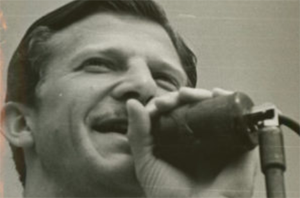

Hubertus Strughold (June 15, 1898 – September 25, 1986) was a German-born physiologist and prominent medical researcher. Beginning in 1935 he served as chief of aeromedical research for the Luftwaffe, holding this position throughout World War II. In 1947 he was brought to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip and held a series of high-ranking medical positions with both the US Air Force and NASA.

For his role in pioneering the study of the physical and psychological effects of manned spaceflight he became known as "The Father of Space Medicine".[1] Following his death, Strughold's activities in Germany during World War II came under greater scrutiny and allegations surrounding his involvement in Nazi-era human experimentation greatly diminished his reputation.

Biography

Early life and career

Strughold was born in the town of Westtünnen-im-Hamm in the Prussian province of Westphalia on 15 June 1898. As a young man he studied medicine and the natural sciences at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and the Georg August University of Göttingen, where he received his doctorate (Dr. med. et phil.) in 1922. He later went on to obtain his medical degree (Dr. med.) from the University of Münster and completed his habilitation (Dr. habil.) at the Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg in 1927. Strughold also worked as a research assistant to the renowned German-Austrian physiologist Dr. Maximilian von Frey. He remained at Würzburg and pursued a career as a professor of physiology.

During this time Strughold's attention was increasingly drawn to the emerging science of aviation medicine and he collaborated with the famed World War I pilot Robert Ritter von Greim to study the effects of high-altitude flight on human biology. In 1928 Strughold traveled to the United States on a year-long research fellowship from the Rockefeller Foundation. He conducted specialized studies into aviation medicine and human physiology at the University of Chicago and Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. He would also visit the medical laboratories at Harvard, Columbia and the Mayo Clinic. Strughold returned to Germany the following year and accepted a teaching position at the Würzburg Physiological Institute, eventually becoming an adjunct professor there in 1933. He would later serve as a professor of physiology at Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin.

Work for Nazi Germany

Through his association with von Greim (Adolf Hitler's personal pilot), Strughold became acquainted socially with various high-ranking members of the Nazi regime and in April 1935, he was appointed Director of the Berlin-based Research Institute for Aviation Medicine, a medical think tank that operated under the auspices of Hermann Göring's Ministry of Aviation. Under Strughold's leadership, the Institute grew to become Germany's foremost aeromedical research establishment, pioneering the study of the medical effects of high-altitude and supersonic speed flight, along with establishing the altitude chamber concept of "time of useful consciousness".

Though Strughold was ostensibly a civilian researcher, the majority of the studies and projects his Institute undertook were commissioned and financed by the German armed forces (principally the Luftwaffe) as part of the ongoing German re-armament. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Strughold's organization was absorbed into the Luftwaffe itself and was attached its medical service. It was renamed the Air Force Institute for Aviation Medicine, and placed under the command of Luftwaffe Surgeon-General (Generaloberstabsarzt) Erich Hippke. Strughold himself was also commissioned as an officer in the German air force, eventually rising to the rank of Colonel (Oberst).

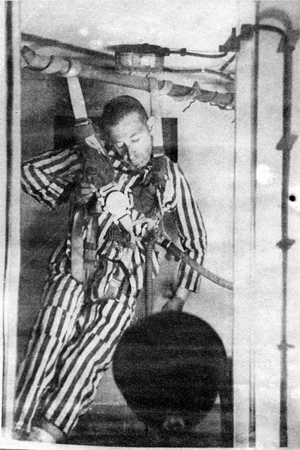

Human experimentation

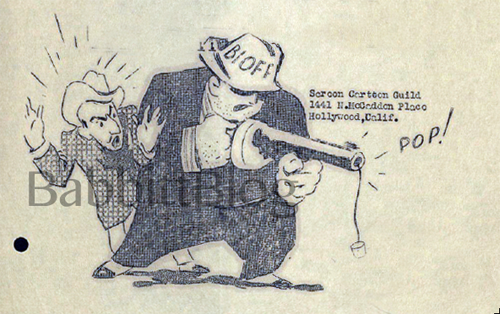

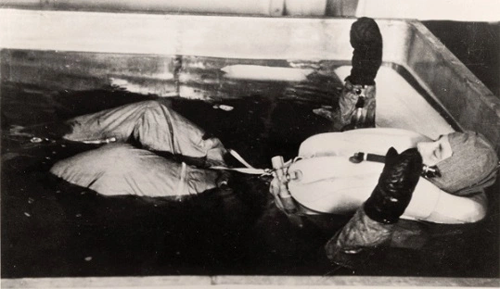

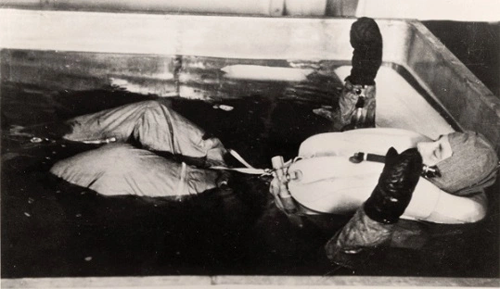

In October 1942, Strughold and Hippke attended a medical conference in Nuremberg at which SS physician Sigmund Rascher delivered a presentation outlining various medical experiments he had conducted, in conjunction with the Luftwaffe, in which prisoners from the Dachau concentration camp were used as human test subjects. These experiments included physiological tests during which camp inmates were immersed in freezing water, placed in air pressure chambers and made to endure invasive surgical procedures without anesthetic. Many of the inmates forced to participate died as a result.[2] Various Luftwaffe physicians had participated in the experiments and several of them had close ties to Strughold, both through the Institute for Aviation Medicine and the Luftwaffe Medical Corps.

Following the German defeat in May 1945, Strughold claimed to Allied authorities that, despite his influential position within the Luftwaffe Medical Service and his attendance at the October 1942 medical conference, he had no knowledge of the atrocities committed at Dachau. He was never subsequently charged with any wrongdoing by the Allies. However, a 1946 memorandum produced by the staff of the Nuremberg Trials listed Strughold as one of thirteen "persons, firms or individuals implicated" in the war crimes committed at Dachau. Also, several of the former Luftwaffe physicians associated with Strughold and the Institute for Aviation Medicine (among them Strughold's former research assistant Hermann Becker-Freyseng) were convicted of crimes against humanity in connection with the Dachau experiments at the 1947 Nuremberg Doctor's Trial. During these proceedings, Strughold contributed several affidavits for the defense on behalf of his accused colleagues.

Work for the United States

In October, 1945 Strughold returned to academia, becoming director of the Physiological Institute at Heidelberg University. He also began working on behalf of the US Army Air Force, becoming Chief Scientist of its Aeromedical Center, located on the campus of the former Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research. In this capacity Strughold edited German Aviation Medicine in World War II, a book-length summary of the knowledge gained by German aviation researchers during the war.

In 1947 Strughold was brought to the United States, along with many other highly valuable German scientists, as part of Operation Paperclip. With another former Luftwaffe physician, Richard Lindenberg, Strughold was assigned to the US Air Force School of Aviation Medicine at Randolph Field near San Antonio, Texas.[3] It was while at Randolph Field that Strughold began conducting some of the first research into the potential medical challenges posed by space travel, in conjunction with fellow "Paperclip Scientist" Dr. Heinz Haber.[4][5]

Strughold coined the terms "space medicine" and "astrobiology" to describe this area of study in 1948. The following year he was appointed as the first and only Professor of Space Medicine at the US Air Force's newly established School of Aviation Medicine (SAM), one of the first institutions dedicated to conducting research on "astrobiology" and the so-called "human factors" associated with manned spaceflight.

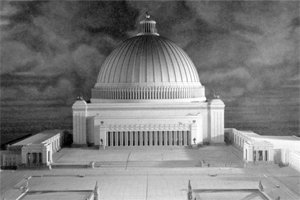

Under Strughold, the School of Aviation Medicine conducted pioneering studies on issues such as atmospheric control, the physical effects of weightlessness and the disruption of normal time cycles.[4][5] In 1951 Strughold revolutionized existing notions concerning spaceflight when he co-authored the influential research paper Where Does Space Begin? in which he proposed that space was present in small gradations that grew as altitude levels increased, rather than existing in remote regions of the atmosphere. Between 1952 and 1954 he would oversee the building of the space cabin simulator, a sealed chamber in which human test subjects were placed for extended periods of time in order to view the potential physical, astrobiological, and psychological effects of extra-atmospheric flight.

Strughold obtained US citizenship in 1956 and was appointed Chief Scientist of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) Aerospace Medical Division in 1962. While at NASA, Strughold played a central role in designing the pressure suit and onboard life support systems used by both the Gemini and Apollo astronauts. He also directed the specialized training of the flight surgeons and medical staff of the Apollo program in advance of the planned mission to the Moon. Strughold retired from his position at NASA in 1968.

Evidence of experimentation on Dachau inmates and epileptic children

During his work on behalf of the Air Force and NASA, Strughold was the subject of three separate US government investigations into his suspected involvement in war crimes committed under the Nazis. A 1958 investigation by the Justice Department fully exonerated Strughold, while a second inquiry launched by the Immigration and Naturalization Service in 1974 was later abandoned due to lack of evidence. In 1983 the Justice Department's Office of Special Investigations reopened his case but withdrew from the effort when Strughold died in September 1986.

Following his death, Strughold's alleged connection to the Dachau experiments became more widely known following the release of US Army Intelligence documents from 1945 that listed him among those being sought as war criminals by US authorities. These revelations did significant damage to Strughold's reputation and resulted in the revocation of various honors that had been bestowed upon him over the course of his career. In 1993, at the request of the World Jewish Congress, his portrait was removed from a mural of prominent physicians displayed at Ohio State University. Following similar protests by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the Air Force decided in 1995 to rename the Hubertus Strughold Aeromedical Library at Brooks Air Force Base, which had been named in Strughold's honor in 1977. His portrait, however, still hangs there. Further action by the ADL also led to Strughold's removal from the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo, New Mexico in May 2006.

Further questions about Strughold's activities during World War II emerged in 2004 following an investigation conducted by the Historical Committee of the German Society of Air and Space Medicine. The inquiry uncovered evidence of oxygen deprivation experiments carried out by Strughold's Institute for Aviation Medicine in 1943. According to these findings six epileptic children, between the ages of 11 and 13, were taken from the Nazi's Brandenburg Euthanasia Centre to Strughold's Berlin laboratory where they were placed in vacuum chambers to induce epileptic seizures in an effort to simulate the effects of high-altitude sicknesses, such as hypoxia. While, unlike the Dachau experiments, all the test subjects survived the research process, this revelation led the Society of Air and Space Medicine to abolish a major award bearing Strughold's name. A similar campaign by American scholars prompted the US branch of the Aerospace Medical Association to announce in 2012 that it would also consider rechristening a similar award, also named in Strughold's honor, which it had been bestowing since 1963. The move was met with opposition from defenders of Strughold, citing his massive contributions to the American space program and the lack of any formal proof of his direct involvement in war crimes.[6]

Awards and honors

Known as The Father of Space Medicine[7]

• Theodore C. Lyster Award, Aerospace Medical Association, 1958

• Louis H. Bauer Founders Award, Aerospace Medical Association, 1965

Hubertus Strughold Award

The Hubertus Strughold Award was established by the Space Medicine Branch, known today as the Space Medicine Association, a member organization of the Aerospace Medical Association. In 1962 the Award was established in honor of Dr. Hubertus Strughold, also known as "The Father of Space Medicine".[8] The award was presented every year from 1963 through 2012 to a Space Medicine Branch member for outstanding contributions in applications and research in the field of space-related medical research.

Awardees

1960s

• 1963 Cpt. Ashton Graybiel, Cpt. M.D., USN

• 1964 Maj. Gen. Otis O. Benson, Jr., USAF, M.C.

• 1965 Hans-Georg Clamann, M.D.

• 1966 Hermann J. Schaefer, Ph.D.

• 1967 Charles Alden Berry, M.D.

• 1968 David G. Simons, M.D.

• 1969 Col. Stanley C. White, M.D., USAF, M.C.

1970s

• 1970 RearAdm Frank Burkhart Voris, MC, USN

• 1971 Dr. Donald Davis Flickinger, M.D.

• 1972 Col. Paul A. Campbell, USAF (Ret.)

• 1973 Andres Ingver Karstens, M.D.

• 1974 Cdr. Joseph P. Kerwin, MC, USN

• 1975 Lawrence F. Dietlein, M.D.

• 1976 Harald J. von Beckh

• 1977 William Kennedy Douglas

• 1978 Walton L. Jones, Jr., M.D.

• 1979 Col. John E. Pickering, USAF (Ret.)

1980s

• 1980 Rufus R. Hessberg, M.D.

• 1981 Maj. Gen. Heinz S. Fuchs, GAF, MC (Ret.)

• 1982 Sidney D. Leverett, Jr., Ph.D.

• 1983 Sherman Vonograd P., M.D.

• 1984 Arnauld E. Nicogossian, M.D.

• 1985 Philip C. Johnson, Jr., M.D.

• 1986 Carolyn Leach Huntoon, Ph.D.

• 1987 Karl E. Klein, M.D.

• 1988 Anatoly Ivanovich Grigoriev, M.D.

• 1989 Brig. Gen. Eduard C. Burchard, GAF, MC

1990s

• 1990 Joan Vernikos-Danellis, M.D.

• 1991 Stanley R. Mohler, M.D.

• 1992 Roberta Lynn Bondar, M.D.

• 1993 George Wyckliffe Hoffler, M.D.

• 1994 Emmett B. Ferguson, M.D.

• 1995 Mary Anne Bassett Frey, Ph.D.

• 1996 Norman E. Thagard, M.D.

• 1997 Shannon Matilda Wells Lucid, Ph.D.

• 1998 Valeri V. Polyakov, M.D.

• 1999 Sam Lee Pool, M.D.

2000s

• 2000 Franklin Story Musgrave, M.D.

• 2001 John B. Charles, Ph.D.

• 2002 Earl Howard Wood, M.D., Ph.D.

• 2003 Jonathan Clark (for STS 107 crew)

• 2004 No award

• 2005 William S. Augerson, M.D.

• 2006 Jeffrey R. Davis, M.D.

• 2007 Clarence A. Jernigan, M.D.

• 2008 Richard Jennings, M.D.

• 2009 Jim Vanderploeg, M.D.

2010s

• 2010 Irene Duhart Long, M.D.

• 2011 Michael Barratt, M.D.

• 2012 Smith L. Johnston III, M.D.

• 2013 Award retired by the Space Medicine Association

See also

• Aerospace Medical Association

• Human factors and ergonomics

• Nazi human experimentation

• Sigmund Rascher

References

1. Walker, Andrew (November 21, 2005). "Project Paperclip: Dark side of the Moon". BBC News.

2. Campbell, Mark R.; Mohler, Stanley R.; Harsch, Viktor A.; Baisden, Denise (2007-07-01). "Hubertus Strughold: the "Father of Space Medicine"" (PDF). Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 78 (7): 716–719, discussion 719. ISSN 0095-6562. PMID 17679572. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-03.

3. PRESENTATION OF AN AWARD FOR MERITORIOUS CONTRIBUTIONS TO NEUROPATHOLOGY to RICHARD LINDENBERG, M.D. by KENNETH M. EARLE, M.D. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1981 Nov;40(6):583-584.

4. Jump up to:a b Strughold, Hubertus. (1954). Atmospheric space equivalence. Journal of Aviation Medicine. 25(4): 420-424.

5. Jump up to:a b Strughold, H. (1956). The US Air Force experimental sealed cabin. Journal of Aviation Medicine. (27): 50-52.

6. A Scientist's Nazi-Era Past Haunts Prestigious Space Prize, By LUCETTE LAGNADO, Wall Street Journal, December 1, 2012

7. Campbell, M., and Harsch, V. (2013) Hubertus Strughold: Life and Work in the Fields of Space Medicine. Rethra Verlag: Norderstedt, Germany, 235.

8. Campbell, Mark R., et al. (July 2007), "Hubertus Strughold: The 'Father of Space Medicine'", Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine; Vol. 78, No. 7; pp 716–9.

Bibliography

• Musgrave, S (2000). "Hubertus Strughold Award". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 71 (8) (published Aug 2000). p. 874. PMID 10954370

• "Hubertus Strughold Award. Earl H. Wood, M.D., Ph.D". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 73 (9) (published Sep 2002). 2002. pp. 948–9. PMID 12234052

External links

• Additional references and photograph at [1] and [2]

• February 22, 1982, March 8, 1982, March 15, 1982, April 19, 1982, April 27, 1982, Interview with Hubertus Strughold, May 23, 1982, University of Texas at San Antonio: Institute of Texan Cultures: Oral History Collection, UA 15.01, University of Texas at San Antonio Libraries Special Collections.

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/27/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Hubertus Strughold

Born June 15, 1898

Westtünnen-im-Hamm, Westphalia, Germany

Died September 25, 1986 (aged 88)

San Antonio, Texas, United States

Citizenship German and American (1956)

Alma mater Georg August University of Göttingen; University of Würzburg

Known for Space medicine, Nazi human experimentation

Scientific career

Fields Aviation medicine, space medicine, physiology

Hubertus Strughold (June 15, 1898 – September 25, 1986) was a German-born physiologist and prominent medical researcher. Beginning in 1935 he served as chief of aeromedical research for the Luftwaffe, holding this position throughout World War II. In 1947 he was brought to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip and held a series of high-ranking medical positions with both the US Air Force and NASA.

For his role in pioneering the study of the physical and psychological effects of manned spaceflight he became known as "The Father of Space Medicine".[1] Following his death, Strughold's activities in Germany during World War II came under greater scrutiny and allegations surrounding his involvement in Nazi-era human experimentation greatly diminished his reputation.

Biography

Early life and career

Strughold was born in the town of Westtünnen-im-Hamm in the Prussian province of Westphalia on 15 June 1898. As a young man he studied medicine and the natural sciences at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and the Georg August University of Göttingen, where he received his doctorate (Dr. med. et phil.) in 1922. He later went on to obtain his medical degree (Dr. med.) from the University of Münster and completed his habilitation (Dr. habil.) at the Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg in 1927. Strughold also worked as a research assistant to the renowned German-Austrian physiologist Dr. Maximilian von Frey. He remained at Würzburg and pursued a career as a professor of physiology.

During this time Strughold's attention was increasingly drawn to the emerging science of aviation medicine and he collaborated with the famed World War I pilot Robert Ritter von Greim to study the effects of high-altitude flight on human biology. In 1928 Strughold traveled to the United States on a year-long research fellowship from the Rockefeller Foundation. He conducted specialized studies into aviation medicine and human physiology at the University of Chicago and Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. He would also visit the medical laboratories at Harvard, Columbia and the Mayo Clinic. Strughold returned to Germany the following year and accepted a teaching position at the Würzburg Physiological Institute, eventually becoming an adjunct professor there in 1933. He would later serve as a professor of physiology at Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin.

Work for Nazi Germany

Through his association with von Greim (Adolf Hitler's personal pilot), Strughold became acquainted socially with various high-ranking members of the Nazi regime and in April 1935, he was appointed Director of the Berlin-based Research Institute for Aviation Medicine, a medical think tank that operated under the auspices of Hermann Göring's Ministry of Aviation. Under Strughold's leadership, the Institute grew to become Germany's foremost aeromedical research establishment, pioneering the study of the medical effects of high-altitude and supersonic speed flight, along with establishing the altitude chamber concept of "time of useful consciousness".

Though Strughold was ostensibly a civilian researcher, the majority of the studies and projects his Institute undertook were commissioned and financed by the German armed forces (principally the Luftwaffe) as part of the ongoing German re-armament. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Strughold's organization was absorbed into the Luftwaffe itself and was attached its medical service. It was renamed the Air Force Institute for Aviation Medicine, and placed under the command of Luftwaffe Surgeon-General (Generaloberstabsarzt) Erich Hippke. Strughold himself was also commissioned as an officer in the German air force, eventually rising to the rank of Colonel (Oberst).

Human experimentation

In October 1942, Strughold and Hippke attended a medical conference in Nuremberg at which SS physician Sigmund Rascher delivered a presentation outlining various medical experiments he had conducted, in conjunction with the Luftwaffe, in which prisoners from the Dachau concentration camp were used as human test subjects. These experiments included physiological tests during which camp inmates were immersed in freezing water, placed in air pressure chambers and made to endure invasive surgical procedures without anesthetic. Many of the inmates forced to participate died as a result.[2] Various Luftwaffe physicians had participated in the experiments and several of them had close ties to Strughold, both through the Institute for Aviation Medicine and the Luftwaffe Medical Corps.

Following the German defeat in May 1945, Strughold claimed to Allied authorities that, despite his influential position within the Luftwaffe Medical Service and his attendance at the October 1942 medical conference, he had no knowledge of the atrocities committed at Dachau. He was never subsequently charged with any wrongdoing by the Allies. However, a 1946 memorandum produced by the staff of the Nuremberg Trials listed Strughold as one of thirteen "persons, firms or individuals implicated" in the war crimes committed at Dachau. Also, several of the former Luftwaffe physicians associated with Strughold and the Institute for Aviation Medicine (among them Strughold's former research assistant Hermann Becker-Freyseng) were convicted of crimes against humanity in connection with the Dachau experiments at the 1947 Nuremberg Doctor's Trial. During these proceedings, Strughold contributed several affidavits for the defense on behalf of his accused colleagues.

Work for the United States

In October, 1945 Strughold returned to academia, becoming director of the Physiological Institute at Heidelberg University. He also began working on behalf of the US Army Air Force, becoming Chief Scientist of its Aeromedical Center, located on the campus of the former Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research. In this capacity Strughold edited German Aviation Medicine in World War II, a book-length summary of the knowledge gained by German aviation researchers during the war.

In 1947 Strughold was brought to the United States, along with many other highly valuable German scientists, as part of Operation Paperclip. With another former Luftwaffe physician, Richard Lindenberg, Strughold was assigned to the US Air Force School of Aviation Medicine at Randolph Field near San Antonio, Texas.[3] It was while at Randolph Field that Strughold began conducting some of the first research into the potential medical challenges posed by space travel, in conjunction with fellow "Paperclip Scientist" Dr. Heinz Haber.[4][5]

"Aero Medical Problems of Space Travel", Journal of Aviation Medicine, December 1949, authored by Henry G. Armstrong, Heinz Haber, and Hubertus Strughold.

Strughold coined the terms "space medicine" and "astrobiology" to describe this area of study in 1948. The following year he was appointed as the first and only Professor of Space Medicine at the US Air Force's newly established School of Aviation Medicine (SAM), one of the first institutions dedicated to conducting research on "astrobiology" and the so-called "human factors" associated with manned spaceflight.

Under Strughold, the School of Aviation Medicine conducted pioneering studies on issues such as atmospheric control, the physical effects of weightlessness and the disruption of normal time cycles.[4][5] In 1951 Strughold revolutionized existing notions concerning spaceflight when he co-authored the influential research paper Where Does Space Begin? in which he proposed that space was present in small gradations that grew as altitude levels increased, rather than existing in remote regions of the atmosphere. Between 1952 and 1954 he would oversee the building of the space cabin simulator, a sealed chamber in which human test subjects were placed for extended periods of time in order to view the potential physical, astrobiological, and psychological effects of extra-atmospheric flight.

Strughold obtained US citizenship in 1956 and was appointed Chief Scientist of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) Aerospace Medical Division in 1962. While at NASA, Strughold played a central role in designing the pressure suit and onboard life support systems used by both the Gemini and Apollo astronauts. He also directed the specialized training of the flight surgeons and medical staff of the Apollo program in advance of the planned mission to the Moon. Strughold retired from his position at NASA in 1968.

Evidence of experimentation on Dachau inmates and epileptic children

During his work on behalf of the Air Force and NASA, Strughold was the subject of three separate US government investigations into his suspected involvement in war crimes committed under the Nazis. A 1958 investigation by the Justice Department fully exonerated Strughold, while a second inquiry launched by the Immigration and Naturalization Service in 1974 was later abandoned due to lack of evidence. In 1983 the Justice Department's Office of Special Investigations reopened his case but withdrew from the effort when Strughold died in September 1986.

Following his death, Strughold's alleged connection to the Dachau experiments became more widely known following the release of US Army Intelligence documents from 1945 that listed him among those being sought as war criminals by US authorities. These revelations did significant damage to Strughold's reputation and resulted in the revocation of various honors that had been bestowed upon him over the course of his career. In 1993, at the request of the World Jewish Congress, his portrait was removed from a mural of prominent physicians displayed at Ohio State University. Following similar protests by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the Air Force decided in 1995 to rename the Hubertus Strughold Aeromedical Library at Brooks Air Force Base, which had been named in Strughold's honor in 1977. His portrait, however, still hangs there. Further action by the ADL also led to Strughold's removal from the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo, New Mexico in May 2006.

Further questions about Strughold's activities during World War II emerged in 2004 following an investigation conducted by the Historical Committee of the German Society of Air and Space Medicine. The inquiry uncovered evidence of oxygen deprivation experiments carried out by Strughold's Institute for Aviation Medicine in 1943. According to these findings six epileptic children, between the ages of 11 and 13, were taken from the Nazi's Brandenburg Euthanasia Centre to Strughold's Berlin laboratory where they were placed in vacuum chambers to induce epileptic seizures in an effort to simulate the effects of high-altitude sicknesses, such as hypoxia. While, unlike the Dachau experiments, all the test subjects survived the research process, this revelation led the Society of Air and Space Medicine to abolish a major award bearing Strughold's name. A similar campaign by American scholars prompted the US branch of the Aerospace Medical Association to announce in 2012 that it would also consider rechristening a similar award, also named in Strughold's honor, which it had been bestowing since 1963. The move was met with opposition from defenders of Strughold, citing his massive contributions to the American space program and the lack of any formal proof of his direct involvement in war crimes.[6]

Awards and honors

Known as The Father of Space Medicine[7]

• Theodore C. Lyster Award, Aerospace Medical Association, 1958

• Louis H. Bauer Founders Award, Aerospace Medical Association, 1965

Hubertus Strughold Award

The Hubertus Strughold Award was established by the Space Medicine Branch, known today as the Space Medicine Association, a member organization of the Aerospace Medical Association. In 1962 the Award was established in honor of Dr. Hubertus Strughold, also known as "The Father of Space Medicine".[8] The award was presented every year from 1963 through 2012 to a Space Medicine Branch member for outstanding contributions in applications and research in the field of space-related medical research.

Awardees

1960s

• 1963 Cpt. Ashton Graybiel, Cpt. M.D., USN

• 1964 Maj. Gen. Otis O. Benson, Jr., USAF, M.C.

• 1965 Hans-Georg Clamann, M.D.

• 1966 Hermann J. Schaefer, Ph.D.

• 1967 Charles Alden Berry, M.D.

• 1968 David G. Simons, M.D.

• 1969 Col. Stanley C. White, M.D., USAF, M.C.

1970s

• 1970 RearAdm Frank Burkhart Voris, MC, USN

• 1971 Dr. Donald Davis Flickinger, M.D.

• 1972 Col. Paul A. Campbell, USAF (Ret.)

• 1973 Andres Ingver Karstens, M.D.

• 1974 Cdr. Joseph P. Kerwin, MC, USN

• 1975 Lawrence F. Dietlein, M.D.

• 1976 Harald J. von Beckh

• 1977 William Kennedy Douglas

• 1978 Walton L. Jones, Jr., M.D.

• 1979 Col. John E. Pickering, USAF (Ret.)

1980s

• 1980 Rufus R. Hessberg, M.D.

• 1981 Maj. Gen. Heinz S. Fuchs, GAF, MC (Ret.)

• 1982 Sidney D. Leverett, Jr., Ph.D.

• 1983 Sherman Vonograd P., M.D.

• 1984 Arnauld E. Nicogossian, M.D.

• 1985 Philip C. Johnson, Jr., M.D.

• 1986 Carolyn Leach Huntoon, Ph.D.

• 1987 Karl E. Klein, M.D.

• 1988 Anatoly Ivanovich Grigoriev, M.D.

• 1989 Brig. Gen. Eduard C. Burchard, GAF, MC

1990s

• 1990 Joan Vernikos-Danellis, M.D.

• 1991 Stanley R. Mohler, M.D.

• 1992 Roberta Lynn Bondar, M.D.

• 1993 George Wyckliffe Hoffler, M.D.

• 1994 Emmett B. Ferguson, M.D.

• 1995 Mary Anne Bassett Frey, Ph.D.

• 1996 Norman E. Thagard, M.D.

• 1997 Shannon Matilda Wells Lucid, Ph.D.

• 1998 Valeri V. Polyakov, M.D.

• 1999 Sam Lee Pool, M.D.

2000s

• 2000 Franklin Story Musgrave, M.D.

• 2001 John B. Charles, Ph.D.

• 2002 Earl Howard Wood, M.D., Ph.D.

• 2003 Jonathan Clark (for STS 107 crew)

• 2004 No award

• 2005 William S. Augerson, M.D.

• 2006 Jeffrey R. Davis, M.D.

• 2007 Clarence A. Jernigan, M.D.

• 2008 Richard Jennings, M.D.

• 2009 Jim Vanderploeg, M.D.

2010s

• 2010 Irene Duhart Long, M.D.

• 2011 Michael Barratt, M.D.

• 2012 Smith L. Johnston III, M.D.

• 2013 Award retired by the Space Medicine Association

See also

• Aerospace Medical Association

• Human factors and ergonomics

• Nazi human experimentation

• Sigmund Rascher

References

1. Walker, Andrew (November 21, 2005). "Project Paperclip: Dark side of the Moon". BBC News.

2. Campbell, Mark R.; Mohler, Stanley R.; Harsch, Viktor A.; Baisden, Denise (2007-07-01). "Hubertus Strughold: the "Father of Space Medicine"" (PDF). Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 78 (7): 716–719, discussion 719. ISSN 0095-6562. PMID 17679572. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-03.

3. PRESENTATION OF AN AWARD FOR MERITORIOUS CONTRIBUTIONS TO NEUROPATHOLOGY to RICHARD LINDENBERG, M.D. by KENNETH M. EARLE, M.D. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1981 Nov;40(6):583-584.

4. Jump up to:a b Strughold, Hubertus. (1954). Atmospheric space equivalence. Journal of Aviation Medicine. 25(4): 420-424.

5. Jump up to:a b Strughold, H. (1956). The US Air Force experimental sealed cabin. Journal of Aviation Medicine. (27): 50-52.

6. A Scientist's Nazi-Era Past Haunts Prestigious Space Prize, By LUCETTE LAGNADO, Wall Street Journal, December 1, 2012

7. Campbell, M., and Harsch, V. (2013) Hubertus Strughold: Life and Work in the Fields of Space Medicine. Rethra Verlag: Norderstedt, Germany, 235.

8. Campbell, Mark R., et al. (July 2007), "Hubertus Strughold: The 'Father of Space Medicine'", Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine; Vol. 78, No. 7; pp 716–9.

Bibliography

• Musgrave, S (2000). "Hubertus Strughold Award". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 71 (8) (published Aug 2000). p. 874. PMID 10954370

• "Hubertus Strughold Award. Earl H. Wood, M.D., Ph.D". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 73 (9) (published Sep 2002). 2002. pp. 948–9. PMID 12234052

External links

• Additional references and photograph at [1] and [2]

• February 22, 1982, March 8, 1982, March 15, 1982, April 19, 1982, April 27, 1982, Interview with Hubertus Strughold, May 23, 1982, University of Texas at San Antonio: Institute of Texan Cultures: Oral History Collection, UA 15.01, University of Texas at San Antonio Libraries Special Collections.