Donald Maclean (spy)by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/25/20

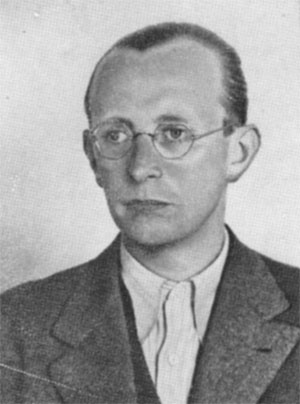

Donald Maclean

Born: Donald Duart Maclean, 25 May 1913, Marylebone, London, England

Died: 6 March 1983 (aged 69), Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union

Nationality: British

Alma mater: Trinity Hall, Cambridge; Gresham's School

Spouse(s): Melinda Maclean

Children: Donald Maclean, Fergus Maclean

Espionage activity

Allegiance: Soviet Union

Service branch: Foreign Office; Rank Counsellor

Donald Duart Maclean (/məˈkleɪn/; 25 May 1913 – 6 March 1983) was a British diplomat and member of the Cambridge Five spy ring which conveyed government secrets to the Soviet Union.

As an undergraduate, Maclean openly proclaimed his left-wing views, and was recruited into the Soviet intelligence service, then known as the NKVD. However, he gained entry to the Civil Service by claiming to have foresworn Marxism. In 1938, he was made Third Secretary at the Paris embassy, where he kept the Soviets informed about Anglo-German diplomacy. He then served in Washington, D.C. from 1944 to 1948, achieving promotion to First Secretary. Here he became Moscow's main source of information about US thermonuclear policy, greatly helping the Soviets to evaluate the relative strength of their own nuclear arsenal.

By the time he was appointed head of the American Department in the Foreign Office, Maclean was widely suspected of being a spy. The Soviets ordered Maclean to defect in 1951. In much later declassified reports, British Intelligence denied to the heads of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) any knowledge of Maclean's activities or whereabouts. In Moscow, Maclean worked as a specialist on British policy and relations between the Soviet Union and NATO. He was reported to have died there on 6 March 1983.

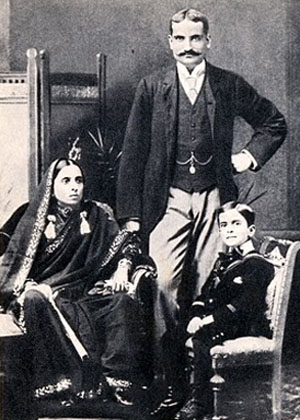

Childhood and schoolBorn in Marylebone, London,[1] Donald Duart Maclean was the son of Sir Donald Maclean and Gwendolen Margaret Devitt. His father was chosen as chairman of the rump of the 23 independent MPs who backed H. H. Asquith in the Liberal Party in the House of Commons whilst the bulk of the Liberal MPs had followed David Lloyd George into the Coalition Liberal party in the November 1918 election. As the Labour Party had no leader and Sinn Féin did not attend, he became titular Leader of the Opposition. Maclean's parents had houses in London (later in Buckinghamshire) as well as in the Scottish Borders, where his father represented Peebles and Southern Midlothian, but the family lived mostly in and around London. He grew up in a very political household, in which world affairs were constantly discussed. In 1931 his father entered the Coalition Cabinet as President of the Board of Education.

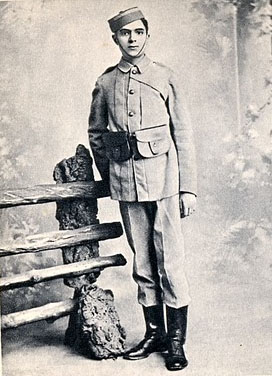

Maclean's education began as a boarder at St Ronan's School, Worthing. At the age of 13, he was sent to Gresham's School in Norfolk,[2] where he remained from 1926 until 1931, when he was 18. At Gresham's, some of his contemporaries were Jack Simon (later Baron Simon, a Law Lord), James Klugmann (1912–1977), Roger Simon (1913–2002), Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) and the scientist and Nobel laureate Sir Alan Lloyd Hodgkin. At Gresham's, all students were required to sign an oath swearing to report on themselves and their fellow students of any and all impure thoughts and actions. Historian Roland Philipps explained to Lapham's Quarterly that Gresham's School is where Donald Maclean as a teenager learned to perfect the traitor's art of duplicity.[3]

Gresham's was then looked on as both liberal and progressive. It had already produced Tom Wintringham (1898–1949) a Marxist military historian, journalist, and author. James Klugmann and Roger Simon both went with Maclean to Cambridge and joined the Communist Party at around the same time. Klugmann became the official historian of the British Communist Party, while Simon was later a left-wing Labour peer.

When Maclean was 16, his father was elected for the North Cornwall constituency, and he spent some time in Cornwall during vacations.

CambridgeFrom Gresham's, Maclean won a place at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, arriving in 1931 to read modern languages. Even before the end of his first year he began to throw off parental restraints and engage openly in communist agitprop.[4] He also played rugby for his college through the winter of 1932–33.[5] Eventually his ambitions would lead to him joining the Communist Party. In Maclean's second year at Cambridge his father died. Maclean's political views grew much more apparent in the following years in light of "his admiring, if sometimes puzzled, mother".[6]

In his final years Maclean had become a campus figure with most knowing he was a communist. In the winter of 1933–34, he wrote a book review for Cambridge Left, to which other leading communists contributed, such as John Cornford, Charles Madge and the Irish scientist, J. D. Bernal. Donald reviewed Contemporary Literature and Social Revolution by J. D. Charques, praising the book in slightly patronising terms for its readiness "to hint at a Marxist conception of literature". In 1934, he became the editor of the Silver Crescent, the Trinity Hall students' magazine. His editorials stressed the decline in world trade, rearmament and arms trafficking. In one article, he insisted: "England is in the throes of a capitalist crisis....If the analysis in the Editorial: A Personal is correct, there is an excellent reason why everyone of military age should start thinking about politics."[7] His Marxist views pervaded all aspects of his public life, often citing the flaws in the university administration. In a letter to Granta he ascribed the demand for a democratically elected student council, equality for female students and rights to use college premises for political meetings.[8]

In his last year, 1934, Donald Maclean became an agent of the Soviet Union's People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, abbreviated from the Russian as NKVD. Established in 1917 as Cheka of Russian SFSR, the agency was originally tasked with conducting suppression of all "counter-revolutionary" activities and overseeing the country's prisons and labor camps. Maclean was recruited by Theodore "Teddy" Maly, a Hungarian Catholic priest turned Soviet "illegal" (a spy operating without a diplomatic cover). Maly lived in London posing as a businessman, having arrived on a forged Austrian passport.[9] Appropriately enough for a man who had once been a Catholic priest, Maly who was known to the Cambridge Five simply as Theo, acted as a sort of confessional figure for the Cambridge Five.[10]

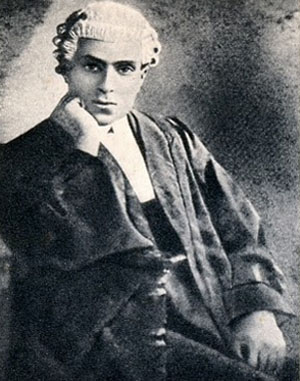

Maclean was then instructed to give up political activity and enter the Diplomatic Service, where at the right moment he would best be able to serve the cause.[11] He graduated with a First in Modern Languages and abandoned his earlier ideas of teaching English in the Soviet Union when pressed by fellow Communists at Cambridge. After spending a year preparing for the Civil Service examinations, Maclean passed with first-class honours.[12] At the Final Board, Maclean was asked by one of the panel interviewing him, whether he had favoured communism while a university student, ostensibly because the panel knew of a trip he had taken to Moscow in his second year at Cambridge. Maclean lied: "At Cambridge, I was initially favourable to it but I am little by little getting disenchanted with it." His apparent sincerity satisfied members of the panel, which included a family friend, Lady Violet Bonham Carter.[citation needed]

LondonIn August 1935, Maclean was examined by the Civil Service Commission and duly admitted to the diplomatic service. In October, he started work at the Foreign Office, and was assigned to the Western department that dealt with the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal, and Switzerland, as well as the League of Nations.[13] In 1936, Maclean became closely involved in the work of the Non-Intervention Committee set up to monitor the activities of the chief powers, Germany, Italy, and the USSR and their involvement in determining the outcome of the Spanish Civil War. To Maclean, his traitorous involvement was a justifiable decision, in hopes of furthering Soviet policy. Just a few years before, in 1935, his fellow Soviet spy Guy Burgess had this to say about their involvement in espionage, "Everyone gives away information. When Churchill was in opposition he used to give away confidential information about what the government was thinking to Maisky, then Russian ambassador." He disastrously thought that Maclean and he were in much the same position as Churchill.[14]

In the summer of 1937, the agent that recruited Maclean, Theodore "Teddy" Maly, left for Paris and anxiously debated his future with other non-Soviet illegals. Knowing he was gravely menaced by Stalin's purge, Maly still left for Moscow and was never heard from again.[15] Maly was arrested upon his return, tortured and executed on the spurious charges of spying for Hungary against the Soviet Union.[16] For a time, multiple meetings passed where no one showed to meet Maclean. Then Kitty Harris (wife of the Communist Party of the USA's party leader) arrived in place of his usual controller and gave the recognition phrase. "You hadn't expected to see a lady, had you?" she said. "No, but it's a pleasant surprise," he replied. Maclean would visit Harris's flat in Bayswater after work, with documents to photograph. Over the next two years, 45 boxes of documents were photographed and sent to Moscow. "She was a cut-out between Maclean and his NKVD controller," said Geoffrey Elliott, who wrote a book about her with Igor Damaskin, a former KGB officer.[17] He was then placed under the operational control of GPU rezident, Anatoli Gorsky. Gorsky, who was appointed in 1939 after the entire London rezidentura was liquidated, used Vladimir Borisovich Barkovsky, a recent graduate of Moscow's Intelligence School as the case officer for Maclean.

ParisIn the autumn of 1938, Maclean had nearly completed three years as a junior member of the League of Nations and the Western department of the Foreign Office and he argued that he was overdue for transfer to his first foreign post. There being no lack of drive in Maclean's ego, he was sent to the prestigious post in Paris. On 24 September 1938, he took up his post as Third Secretary at HM Embassy, Paris. Although Maclean strove to closely conform to the normalities representative of the Foreign Office social class, he lacked the funds and savoir-faire of his colleagues. As a striver, he was mocked by the typing pool as Fancy-Pants Maclean.[18] Ronnie Campbell was to have a crucial impact on Maclean as well as his career. Another was Michael Wright, who was the senior First Secretary and always appreciated Maclean's drafting skills.

In the spring of 1939, an Anglo-French attempt was made to include the Soviet Union into the "peace front" that was intended to deter German aggression. Because of the French involvement in these Moscow negotiations, the telegrams passing between embassies allowed Maclean access to a privy of information. Maclean kept Moscow informed in regard to relations between Germany and the British Empire, on the one hand, and Britain and France on the other, as the French foreign minister Georges Bonnet worked to end French security commitments in Eastern Europe. He also kept Moscow informed about the development of Anglo-French plans for intervention in the war between Finland and the Soviet Union.[19]

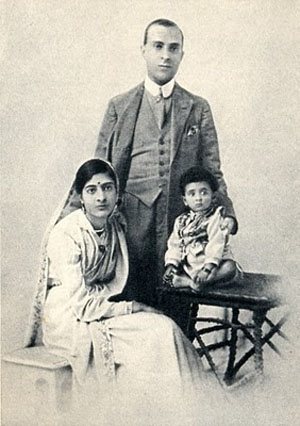

One evening, December 1939 in Paris, Maclean met Melinda Marling. The daughter of a Chicago oil executive, she was a teenager when her parents had divorced, her mother moving to Europe. In October 1929, Melinda and her sisters went to school at Vevey, near Lausanne, where their mother rented a villa, and spent their holidays at Juan-les-Pins in France.[20] Melinda Marling's mother moved to New York, marrying Charles Dunbar, an executive in the paper industry, and brought her daughters to live with them in Manhattan, where Melinda Marling attended the Spence School. After graduation she spent some months in New York City then returned to Paris, where she enrolled at the Sorbonne in Paris to study French literature.[21] Melinda Marling was introduced to Maclean, in the Café Flore in December 1939, possibly by Mark Culme-Seymour. Culme-Seymour later described her as "quite pretty and vivacious, but rather reserved. I thought that she was a bit prim. She was always well-groomed, lipstick bright, hair permed, a double row of pearls around her neck. Her interests seemed limited to family, friends, clothes and Hollywood movies."[22]

In the 1950s, Culme-Seymour tracked down the exiled Macleans in Moscow, and another Melinda emerged. She told him that she knew she would be going to Russia right from the beginning, even before Maclean defected.[22]

Soviet archives confirm this view. As Maclean told Harris, on the evening he met Melinda, he saw more to her "I was very taken by her views. She's a liberal, she's in favour of the Popular Front and doesn't mind mixing with communists even though her parents are well-off. There was a White Russian girl, one of her friends, who attacked the Soviet Union and Melinda went for her. We found we spoke the same language." Maclean had told Melinda Marling about his role as a spy. He told Harris that Marling not only reacted positively, but "actually promised to help me to the extent that she can – and she is well connected in the American community".[22]

On 10 June 1940, as the German Army approached Paris, Donald Maclean and a pregnant Melinda Marling were married at the local Mairie.[20] The British Embassy was evacuated and the Macleans drove south with one of Donald Maclean's colleagues. Few marriages could have begun in greater turmoil. On 13 June, the Military Attaché gave warning that "if the Embassy party did not at once cross the Loire, they might be cut off."[23] They were able to escape France on a small merchant ship and went to London.

London in World War IIMaclean continued to report to Moscow from London, where he was assigned by the British Foreign Office to work on economic warfare matters. Maclean became the Foreign Office's expert in economic warfare, civil air matters, military base negotiations and natural resources useful in the war, such as tungsten. It was in 1940, after the fall of France, that Maclean had two meetings with Philby, their first encounter since the mid-1930s.[24] Three days before Christmas 1940, Melinda Maclean went to New York to have her baby, which died shortly after its birth. Some weeks later she flew back to London and went to work in the BBC bookstore. It was here that Gorsky became closely involved in Maclean's career in espionage.[25] It was also around this time that Maclean began to show his debauchery at Victor Rothschild's home where Blunt and Burgess were living.[26]

The Macleans became part of the social set that circulated between the Café Royal, the Gargoyle Club and the country house weekends of the Liberal establishment. Donald Maclean was promoted and given the prestigious assignment as Second Secretary at the British Embassy in Washington.[27] Towards the end of April 1944, the Macleans set sail in convoy for New York, where they arrived on 6 May.

WashingtonMaclean served in Washington from 1944 to 1948, achieving promotion to First Secretary. In 1944, Maclean provided a copy of every cable to and from Sir Anthony Eden, the Foreign Secretary, to Lord Halifax, the ambassador, to the NKVD.[28] Melinda Maclean was again pregnant, giving birth to a son in New York City. The Macleans frequently visited Melinda Maclean's mother and stepfather in Manhattan and at Dunbar's country place in the Berkshires. They vacationed on Long Island and Cape Cod with Mrs. Dunbar and Melinda Maclean's sisters. The Macleans became part of the liberal Georgetown social set in Washington, which included Katharine Graham,[29][30] as well as participating in the diplomatic life of the city.[31] Maclean never passed on any information to his handler in Washington, instead going to New York on a weekly basis, and so frequent were his trips to New York that his colleges believed he had a mistress there.[32] Maclean was considered to be an exceptionally hard worker at the embassy as his fellow diplomat Robert Cecil remembered in 1989: "No task was too hard for him; no hours were too long. He gained the reputation of one who would always take over a tangled skein from a colleague who was sick, or going on leave, or simply less zealous. In this way he was able to manoeuvre himself into the hidden places that were of the most interest to the NKVD".[33]

On 15 June 1945, the American columnist Drew Pearson in his 'Washington Merry-Go-Round' column published details of a secret letter sent from Churchill to President Truman together with details of talks between Harry Hopkins and Stalin.[34] In response, the FBI, which suspected that the leak came from someone within the British Embassy began an investigation, which led them to place Maclean under surveillance after he was observed going into a gay bar.[35] The FBI believed that Maclean was a homosexual being blackmailed into leaking information by Pearson and discovered that Maclean was a heavy drinker who often engaged in random sexual encounters with various men, but failed to discover that he was a Soviet spy.[36]

Towards the end of that period Donald Maclean acted as Secretary of the Combined Policy Committee on atomic energy matters.[37] He was Moscow's main source of information about US/UK/Canada atomic energy policy development. Although Maclean did not transmit technical data on the atom bomb, he reported on its development and progress, particularly the amount of plutonium (used in the Fat Man bombs) available to the United States. As the British representative on the American-British-Canadian Council on the sharing of atomic secrets, he was able to provide the Soviet Union with information from Council meetings. This gave Soviet scientists the ability to predict the number of bombs that could be built by the Americans. Coupled with the efforts of Los Alamos-based scientists Alan Nunn May, Klaus Fuchs and Theodore Hall (who had been identified but was allowed to remain at large), Maclean's reports to his NKVD controller gave the Soviets a basis to estimate their nuclear arsenal's relative strength against that of the United States and Britain. In addition to atomic energy matters, Maclean's responsibilities at the Washington embassy included civil aviation, bases, post-hostilities planning, Turkey and Greece, NATO and Berlin.[38] It has been reported that Maclean suggested to Moscow that the goal of the Marshall Plan was to ensure American economic domination in Europe.[39] Maclean's cover name was Homer.[40]

CairoIn 1948, Maclean was appointed head of Chancery at the British embassy in Cairo. He was at that time the youngest Counsellor in the British foreign service. As soon as he arrived, Maclean had problems with his MGB contact, who arranged their meetings in an unsatisfactory manner. Maclean suggested that Melinda should simply pass his information to the wife of the Soviet resident at the hairdresser. "Melinda was quite prepared to do this," Modin reports.[41]

Cairo was an important post, the key to British power in the area and a central point in Anglo-American planning for war with the Soviet Union.[42] At this time Britain was the major power in the Middle East with troops in both the Canal Zone and nearby Palestine and airbases in the Canal Zone from which American atomic bombers could reach the Soviet Union. In regard to Egypt itself, British policy was one of laissez-faire or non-interference with the corruption surrounding King Farouk. Maclean disagreed strongly and felt that Britain should encourage reform which alone, in his opinion, could save the country from communism. "And, except to stress its dangers, that was all I ever heard Donald say about communism." recalls Geoffrey Hoare, the News Chronicle Cairo correspondent.[43]

Maclean was considered the key official in the Cairo Embassy, specifically responsible for coordinating US/UK war planning and, under the Ambassador, relations with the Egyptian government.[44] By now, his double life was beginning to affect Maclean. He began drinking, brawling and talking about his life. After a drunken episode which resulted in the wrecking of an American embassy staffer's apartment, Melinda told the ambassador that Donald was ill and needed leave to see a London doctor.[45] It is possible that this series of events was contrived to provide a way for Maclean to return to England as American intelligence was getting close to identifying Maclean as a Soviet agent by means of the VENONA messages. At this time Melinda Maclean was having an affair with an Egyptian aristocrat, with whom she travelled to Spain when Donald Maclean went to England.[46]

London deskboundAfter a few months rest Maclean recovered from the troubles of his Egyptian period and Melinda Maclean agreed to return to the marriage, immediately becoming pregnant. Maclean's career did not seem to suffer from the events in Egypt. He was promoted and made head of the American Department in the Foreign Office, perhaps its most important assignment for an officer at Maclean's level. This allowed him to continue to keep Moscow informed about Anglo-American relations and planning. The most important report Maclean sent to Moscow concerned the emergency summit in Washington in December 1950 between the British Prime Minister Clement Attlee and U.S President Harry S. Truman.[47] After China entered the Korean War, there were demands both outside and inside the U.S. government, most notably by General Douglas MacArthur, that the U.S attack China with nuclear weapons. The British were strongly opposed to both the use of nuclear weapons and escalating the war by attacking China, and Attlee had gone to Washington with the aim of stopping both. Truman reassured Attlee at the Washington summit that he would not allow the use of nuclear weapons or take the war outside of Korea.[48] Maclean provided a transcript of what was said at the Truman-Attlee summit to Yuri Modin, the "control" of the Cambridge spy ring.[49] Meanwhile, the American and British governments were concluding that Maclean was indeed a Soviet agent, a process carefully tracked by Kim Philby in Washington.

The journalist Cyril Connolly described him vividly as he struck him in London in 1951. "He had lost his serenity, his hands would tremble, his face was usually a livid yellow ... he was miserable and in a very bad way. In conversation, a kind of shutter would fall as if he had returned to some basic and incommunicable anxiety."[50]

DetectionMaclean's role was discovered when the VENONA decryption was carried out at Arlington Hall, Virginia and Eastcote in London between 1945 and 1951. These related to coded messages between New York, Washington and Moscow for which Soviet code clerks had re-used one-time pads. The cryptanalysts working as part of the Venona project, discovered that twelve coded cables had been sent, six from New York from June to September 1944 and six from Washington in April 1945, by an agent named Gomer. The first cable sent but not the first to be deciphered described a meeting with Sergei on 25 June and Gommer's (sic) forthcoming trip to New York where his wife was living with her mother awaiting the birth of a child. This was decoded in April 1951. A short list of nine men was identified as possible Homers (Gomer is the Russian form of Homer),[51] one of whom was Maclean.[52]

The second cable on 2–3 August 1944 was a description, but not a transcript, of a message from Churchill to Roosevelt, which Homer claimed to have decrypted. It suggested that Churchill was trying to persuade Roosevelt to abandon plans for Operation Anvil, the invasion of Provence, in favour of an attack through Venice and Trieste into Austria. This was typical of Churchill's strategic thinking since he was always looking for a flanking move. But it was rejected outright by both American and British generals.[53]

Shortly after the VENONA investigation began, Kim Philby, another member of the Cambridge Five, was assigned to Washington, serving as Britain's CIA-FBI-NSA liaison. He saw the VENONA material, and recognised that Maclean was Homer, which was confirmed by his KGB control.[39]

Believing that Maclean would confess to MI5, Philby and Guy Burgess decided that Burgess would travel to London, where Maclean was head of the Foreign Office's American desk, to warn him. Burgess received three speeding tickets in a single day. The Governor complained to the British Ambassador and Burgess went back to London, in disgrace.

The Soviets were desperate for Maclean to get out, fearful that in his current state he would crack immediately under interrogation. Maclean sounded out Melinda about the defection. According to Modin, she responded: "They're quite right – go as soon as you can, don't waste a single moment."[41]

DefectionThe day eventually earmarked for Maclean to make his escape happened to be his thirty-eighth birthday: 25 May 1951. He came home by train from the Foreign Office to their house in Kent as usual that evening, and soon after Guy Burgess, who had just been persuaded to get out too, turned up. After eating the birthday supper that Melinda had prepared, Maclean said goodbye to his wife and children, got into Burgess's car and left. They drove to Southampton, took a ferry to France, then disappeared from view, sparking a media and intelligence furore. It was five years before Khrushchev finally admitted that they were in the Soviet Union.

The following Monday, Melinda Maclean telephoned the Foreign Office to ask coolly if her husband was around. Her pose of total ignorance convinced them; MI5 put off interviewing her for nearly a week, and the Maclean house was never searched. No doubt their readiness to see her merely as the ignorant wife was enhanced by the fact that she was heavily pregnant at the time – three weeks after Donald left, she gave birth to a daughter, their third child. Francis Marling, Melinda's father, flew from New York to help. Friends in the State Department gave him Foreign Office contacts who proved unhelpful. He returned to New York with a low opinion of Foreign Office officials. He felt then, as others felt later, that no serious effort was being made.[54]

MoscowMaclean, unlike Burgess, assimilated into the Soviet Union and became a respected citizen, learning Russian, earning a doctorate and serving as a specialist on the economic policy of the West and British foreign affairs. Burgess learned only enough Russian to just manage to get by in Moscow while Maclean worked very hard at becoming fluent in Russian.[55] After a brief period of teaching English in Kuybyshev (now Samara) at a Russian provincial school, Maclean joined the staff of International Affairs in early 1956 as a specialist on British home and foreign policy and relations between the Soviet Union and NATO. He shared a small room with his new Soviet colleagues on the second floor of the journal's premises on Gorokhovsky Pereulok.[56] He also worked for the Soviet Foreign Ministry and the Institute of World Economy and International Relations.[57] In 1956, the Soviet government first revealed that Maclean and Burgess were living in Moscow, though the TASS statement denied that they were spies, claiming that they had gone behind the Iron Curtain to "further understanding between East and West" for the sake of world peace.[58]

He was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour and the Order of Combat. His publications for IMEMO were under the name of S. Madzoevsky. In the 1970s, Maclean used his prestige with the KGB to protect members of the early dissident movement. He seems to have had some contact with Sakharov and Roy and Zhores Medvedev and shortly before his death wrote a critique of the retrograde development of Soviet society.

Melinda Maclean and their children joined Maclean in Moscow more than a year after his defection. Melinda was aware of her risks as a collaborator to her husband; two months earlier, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg had been executed for spying. But Melinda usually concealed her thoughts behind an expressionless look. "I will not admit that my husband, the father of my children, is a traitor to his country", she would say in outraged tones.[22]

Extramarital affairs and later family lifeThe Macleans had three surviving children: Fergus, born in 1944, Donald, in 1946, and Melinda, in 1951.[59] The Maclean marriage came under pressure in Moscow as Donald Maclean continued to drink heavily until the mid-1960s, becoming violent when drunk. Kim Philby and Melinda Maclean became lovers during a ski trip in 1964, while Eleanor Philby, Philby's American wife, was on an extended visit to the US. Maclean found out and broke with Philby. Eleanor Philby discovered the affair on her return and left Moscow, for good. Melinda moved in with Philby in 1966, but within three years tired of him and left. She returned to her husband, and remained with him until she left Moscow for good in 1979.[41] Melinda returned to the West to be with her mother and sisters; her children soon followed her. She died in New York in 2010 without saying a single word to the media.[60][61]

The three Maclean children all married Russians, but left Moscow to live in London and the U.S, as they still had the right to British or American passports. Fergus, the eldest son, enrolled at University College London in 1974, prompting a question in Parliament.[62] Donald's son, Donald, married firstly Lucy, daughter of George Hanna, an English man who worked for the BBC and was a friend of the family.[63] They had a son, Donald Duart Maclean's only grandson (who was born in 1970),[63] who resides in the UK.

DeathMaclean was reported seriously ill with pneumonia in December 1982,[64] and was housebound after his recovery.[65] The Institute of World Economy and International Relations, Maclean's workplace, reported his death at the age of 69 on 6 March 1983.[66] He was cremated and his ashes were scattered on his parents' grave in the churchyard of Holy Trinity Church, Penn, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom. Twenty years previously, Guy Burgess's ashes had also been scattered on his family grave in England.[67]

LegacyIn May 1970, Hodder & Stoughton published Maclean's book British Foreign Policy since Suez which he wrote for a British readership. Maclean told journalists that he set out to analyse the subject rather than to attack it, but criticised British diplomatic support for the United States in the Vietnam War. He stated that he would donate the British royalties to the British Committee for Medical Aid to Vietnam.[68] He foresaw a strengthening of British influence in the 1970s and 1980s as a result of economic recovery. Interviewed live by a BBC Radio reporter who detected a nostalgia for Britain in the book, Maclean refused to be drawn on whether he would like to return to London, for further research for his next book. After his death, his body was cremated and per his will, his ashes were buried in Britain.[69]

Of the five spies that made up the Cambridge Spy Ring, Maclean was not the best known, but he provided the most intelligence of value to the Soviet Union as his position as a senior diplomat in the Foreign Office gave access to more information that could be accessed by Philby, Cairncross, Blunt or Burgess as he able to provide the Soviets with "the most intimate details" of Anglo-American decision-making on such matters as the future of nuclear energy and the founding of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.[70] In an official American appraisal concluded: "In the fields of US/UK/Canada planning on atomic energy, US/UK post-war planning and policy in Europe, all information up the date of Maclean's defection undoubtedly reached Soviet hands".[71]

Honours• Order of the Red Banner of Labour

See also• Cambridge Five

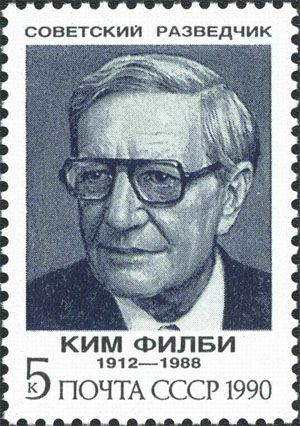

• Kim Philby (1912–1988)

• Guy Burgess (1911–1963)

• Anthony Blunt (1907–1983)

• James Klugmann (1912–1977)

• John Cairncross (1913–1995)

References1. GRO Register of Births:SEP 1913 1a 899 MARYLEBONE – Donald D. Maclean, mmn = Devitt

2. S.G.G. Benson and Martin Crossley Evans, I Will Plant Me a Tree: an Illustrated History of Gresham's School, London: James & James, 2002.

3. Philipps, Roland (13 July 2018). "The World in Time". Lapham's Quarterly. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

4. Cecil, Robert, A Divided Life: A Personal Portrait of the Spy Donald Maclean, New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, 1989, pp. 22–23.

5. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), p. 28.

6. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), p. 23.

7. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), pp. 27–30.

8. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), p. 32.

9. Polmer and Allen, The Spy Book, p. 352.

10. Polmer and Allen, The Spy Book, p. 352.

11. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), pp. 35–36.

12. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), p. 37.

13. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), pp. 39–43.

14. Spender, Sir S., Journals: 1939–83, London: Faber, 1985, p. 215.

15. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), p. 48.

16. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 352.

17. Elliott, Geoffrey, and Igor Damaskin, Kitty Harris: The Spy with Seventeen Names, London: St Ermin's Press, 2001.

18. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), pp. 50–51.

19. Michael Holzman, Donald and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage, Briarcliff Manor, New York: The Chelmsford Press, 2014.

20. Jump up to:a b Geoffrey Hoare, The Missing Macleans, New York: The Viking Press, 1955.

21. 'Holzman: Donald and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage, '2014.

22. Jump up to:a b c d The Guardian (Manchester and London), 10 May 2003.

23. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), p. 62.

24. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), p. 64.

25. Cecil, A Divided Life (1989), p. 66.

26. Roland Philipps (2018). A Spy Named Orphan: The Enigma of Donald Maclean. W. W. Norton. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-393-60858-8.

27. Holzman: Donald and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage, 2014.

28. Polmar and Allen, The Spy Book, p. 348.

29. Roland Philipps (2018). A Spy Named Orphan: The Enigma of Donald Maclean. W. W. Norton. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-393-60858-8.

30. Katharine Graham (1997). Personal History. A.A. Knopf. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-394-58585-7. Donald Maclean relieving himself on the front lawn the nightmare.

31. Holzman, Donald and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage, 2014.

32. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 348.

33. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 348.

34. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 348.

35. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 348.

36. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 348.

37. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 348.

38. Holzman, Donald and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage, 2014.

39. Moynihan, Daniel Patrick (1998). Secrecy : The American Experience. Yale University Press. pp. 54. ISBN 0-300-08079-4. "In these coded messages the spies' identities were concealed beneath aliases, but by comparing the known movements of the agents with the corresponding activities described in the intercepts, the FBI and the code-breakers were able to match the aliases with the actual spies."

40. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 348.

41. Modin, Yuri Ivanovitch, My Five Cambridge Friends, Headline Book Publishing, London, 1994. ISBN 0-374-21698-3

42. Holzman, Donald and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage, 2014.

43. Hoare, The Missing Macleans, 1955.

44. Holzman, and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage, 2014.

45. Hoare, The Missing Macleans, 1955.

46. Holzman, and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage, 2014.

47. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 349

48. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 349.

49. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 349.

50. Cyril Connolly: The Missing Diplomats. London: The Queen Anne Press, 1952.

51. Philby, Kim (2002). My Silent War. Modern Library. p. 170. ISBN 9780375759833. Retrieved 5 January2015.

52. Lamphere, Robert, and Tom Shactman, The FBI-KGB War, New York: Random House, 1986, pp. 232–237.

53. S. J. Hamrick, Publisher Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1999, p. 233.

54. Hoare, The Missing Macleans, 1955.

55. Polmar and Allen, The Spy Book, p. 349.

56. "Secret Agent Donald Maclean at "International Affairs" Author(s): Tatyana IEVLEVA; Source International Affairs, No. 1, Vol. 41, 1995, pp. 97–98.

57. Polmar and Allen, The Spy Book, p. 349.

58. Polmar and Allen, The Spy Book, p. 349.

59. Little Lost Lambs (accessed 12 August 2007)

60. Melindia Maclean died in February 2010. Kim Philby Was Here Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine by Ambassador Richard Carlson and Buckley Carlson in Foundation for Defense of Democracies (accessed 12 August 2007)

61. Ivanova, Rufina et al., The Private Life of Kim Philby: The Moscow Years (2000).

62. Hansard, 25 January 1974, vol. 867 c377W.

63. Cecil, Robert, A Divided Life: A biography of Donald Maclean, Bodley Head, 1988, p. 178.

64. Lucy Hodges, "Maclean may have pneumonia", The Times, 6 December 1982, p. 1.

65. "Death of Maclean rumoured", The Times, 11 March 1983, p. 1.

66. The New York Times (1923-Current file); 11 March 1983, p. A5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

67. Cecil, Robert. A Divided Life: A Personal Portrait of the Spy Donald Maclean. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1989.

68. "Maclean: European manqué" (The Times Diary), The Times, 30 April 1970, p. 10.

69. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 349.

70. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 349.

71. Polmer and Allen The Spy Book, p. 349.

Further reading• Cyril Connolly, The Missing Diplomats. This contemporary account was published by Ian Fleming's Queen Anne Press in 1952.

• Miranda Carter, Anthony Blunt: His Lives, Macmillan, 2001.

• Christopher Andrew and Vasily Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive, volume 1, 1999.

• Richard C.S. Trahair and Robert Miller, Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations, Enigma Books, 2009. ISBN 978-1-929631-75-9.

• Michael Holzman, Donald and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage, Briarcliff Manor, New York: Chelmsford Press, 2014.

External links• Donald Maclean (BBC)

• File release: Cold War Cambridge spies Burgess and Maclean, The National Archives, 23 October 2015

• Donald Maclean at Find a Grave