Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Charles Goethe

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/30/20

Charles Matthias Goethe (March 28, 1875 – July 10, 1966)[1] was an American eugenicist, entrepreneur, land developer, philanthropist, conservationist, founder of the Eugenics Society of Northern California, and a native and lifelong resident of Sacramento, California.

Early life

Charles M. Goethe was born on March 28, 1875 in Sacramento California.[2] He pronounced his last name as GAY-tee.[3] Goethe's grandparents had immigrated to California from Germany in the 1870s.[2] Charles’ father was interested in agriculture and wild life. Both men also pursued careers in real estate as Charles made most of his money as a real estate broker.[2] Charles had passed the bar exam but did not pursue a career in law.[4]

As a child, Charles was interested in agriculture, biology, and the human body. In his diary, he kept a record of his diet and exercise, specifically noting days in which his regimen was not sufficient.[2] Goethe's additional childhood interest in various plants and animals evolved as he pressed and catalogued his findings.[2] His ideas concerning nature tied into his later views on eugenics, as he connected the evolution of nature to heredity.[2] Goethe explained in his memoir Seeking to Serve that his original interest in eugenics began as a child.[2]

Nature guide movement

Goethe (German pronunciation: [ˈɡøːtə] and occasionally incorrectly as "Gaytee") wrote admiringly of California’s Forty-Niners, the State’s giant redwood trees, and loved the outdoors. Goethe worked with organizations including the Sierra Club and the Audubon Society.[2] He and his wife have been called "The father and mother of the Nature Guide Movement,' initiating interpretive programs with the U.S. National Park Service.[5] The National Park Service made Goethe the “Honorary Chief Naturalist” for his work in this field.[2] This was motivated by their experience with nature programs in Europe and desire to educate visitors in the U.S. National Parks.[6] His motto was "Learn to Read the Trail-side as a Book." Goethe encouraged the general public to educate themselves about the evolution of nature as well, personally spending time dedicated to learning about different plants and animals.[2] He later introduced the Boy Scouts to Sacramento, due to his interest in furthering biological education for children.[2] As an adult, Goethe was a conservationist who worked to implement park rangers into national parks.[2]

Founder of Sacramento State College

Goethe founded California State University, Sacramento (Sacramento State College at the time), which in turn treated Goethe with the reverence of a founding father, appointed him chairman of the University's advisory board, dedicated the Goethe Arboretum to him in 1961, and organized an elaborate gala and 'national recognition day' to mark his 90th birthday in 1965, when he received letters of appreciation - solicited by his friends at CSUS - from the president of the Nature Conservancy, then-Governor Edmund G. Brown, and then-President Lyndon B. Johnson. As a result, in 1963, Goethe changed his will to make CSUS his primary beneficiary, bequeathing his residence, eugenics library, papers, and $640,000 to the University.[7]

When Goethe died, CSUS received the largest share of his $24 million estate.

Eugenics controversy

Charles Goethe worked near Arizona, focusing on health conditions in the 1920s.[2] Following his work in Arizona, Goethe desired to understand “the extent of the mestizo peril to the American ‘seed stock.'"[2] Essentially, Goethe was determined to discover the threat of Mexicans to the American population, in a eugenic sense. As a result, Goethe created the Immigration Study Commission.[2][4] With the help of his organization, Goethe hoped to ban Mexican entry into the United States of America. In addition, Goethe portrayed Mexicans as carriers of different diseases and germs. While he believed that certain Mexicans could appear as free of disease, they could in fact be silent carriers due to their health practices.[2] His ideas contributed to 1920s perceptions that the American melting pot had begun to integrate germs from certain races, specifically the Mexican race.[2]

Goethe was a strong proponent of positive eugenics.[4] His mentor was eugenicist Madison Grant, with whom he shared strong anti-immigrant beliefs. Like Grant, Goethe promoted his anti-immigrant and racist ideas through pamphlets and other tracts, and he lobbied with politicians and other bureaucrats.[8] Goethe created tiny pamphlets that he distributed to explain his beliefs concerning specific ethnic groups.[2] In these booklets, he explained the importance of family planning and eugenic practices to ensure the superiority of certain races. He invested nearly 1 million dollars to produce and distribute these pamphlets to increase biological literacy.[2] In addition to investing in these booklets, Goethe also invested in research for plant and biological genetics.[2]

Goethe also recommended compulsory sterilization of the 'socially unfit', opposed immigration, and praised German scientists who used a comprehensive sterilization program to 'purify' the Aryan race before the outbreak of World War II. Goethe also funded anti-Asian campaigns, praised the Nazis before and after World War II, and practiced discrimination in his business dealings, refusing to sell real estate to Mexicans and Asians.

Goethe believed a variety of social successes (wealth, leadership, intellectual discoveries) and social problems (poverty, illegitimacy, crime and mental illness) could be traced to inherited biological attributes associated with 'racial temperament'.

Working with the Human Betterment Foundation in Pasadena, California, Goethe lobbied the State to restrict immigration from Mexico and carry out involuntary sterilizations of mostly poor women, defined as 'feeble-minded' or 'socially inadequate' by medical authorities between 1909 and the 1960s.[7][9]

Goethe was also involved in the publication of multiple journals in which he expressed his views on eugenics. Goethe was involved with the journal Survey Graphic, serving as a member of the council. The journal had published information about typhus quarantines in Mexico in both 1916 and 1917.[2] In addition to Survey Graphic, Goethe was also featured in the journal Eugenics and explained his beliefs that Mexicans were the dirt of society.[2] In the journal from the American Eugenics Society, he explained that Mexicans were as low as Negros, and did not understand basic health rules, but also resisted healthy practices.[2] In his articles, Goethe also explained that Mexicans and South Europeans were responsible for stealing jobs from Americans and introducing germs to the people.[2]

Upon return from a trip to Germany 1934, which at the time was sterilizing over 5,000 citizens per month, Goethe reportedly told a fellow eugenicist, "You will be interested to know that your work has played a powerful part in shaping the opinions of the group of intellectuals who are behind Hitler in this epoch-making program. Everywhere I sensed that their opinions have been tremendously stimulated by American thought...I want you, my dear friend, to carry this thought with you for the rest of your life, that you have really jolted into action a great government of 60 million people."[9] The Nazi eugenics movement eventually escalated to become The Holocaust, which claimed the lives of well over 10 million 'undesirables', including 6 million Jews.

In Sacramento, during Goethe's life, the advocacy of eugenics -the social philosophy of attempting to 'improve' the human population by artificial selection - was considered a progressive issue. Though it was opposed by many scientists who thought the understanding of human heredity was too shallow to create solid policy, and by religious leaders who opposed birth control of any form, in the years after the Holocaust it was not considered to be as radical as it is today.[9] Around 20,000 patients in California State psychiatric hospital were sterilized with minimal or non-existent consent given between 1909 and 1950, when the law went into general disuse before its repeal in the 1960s. A favorable report by Human Betterment Foundation workers E.S. Gosney and Paul B. Popenoe, touting the results of the sterilizations in California, was published in the late 1920s, which in turn was often cited by the Nazi government as evidence wide-reaching sterilization programs were feasible and humane.[10] When Nazi administrators went on trial for war crimes in Nuremberg after World War II, they justified their mass-sterilizations by pointing at the United States as their inspiration.

CSUS attempted to name a new science building after him in 1965, but that effort was rebuffed by students and teachers.[7] In 2005, the university changed the name of its arboretum and botanic garden from the Charles M. Goethe Arboretum to the University Arboretum without fanfare because of renewed attention to Goethe's virulently racist views, praise of Nazi Germany, and advocacy for eugenics.

On June 21, 2007, the school board of the Sacramento City Unified School District voted to rename the "Charles M. Goethe Middle School" to the "Rosa Parks Middle School".[11]

On January 29, 2008, the Sacramento Board of Supervisors stripped his name from one of Sacramento County's busiest parks.[12] On April 25, 2008, the Sacramento Bee reported that, with a nod from Internet voters and the county parks commission, the park will be renamed River Bend Park.[13]

Personal life

Charles Goethe married Mary Glide in 1903.[2] Glide came from a wealthy family and Goethe attempted to court Mary nine times before she accepted his offer.[2] According to Goethe, his wife Mary had refused his proposals since she feared that he was solely interested in her wealth. In addition, she rejected his attempts due to the fact that she was struggling with infertility.[2] The Goethes owned multiple ranches and invested money in the stock market, becoming a wealthy and lucrative family.[2] At the time of her death in 1946, Mary's estate was worth 1.5 million.[2] Her husband, Charles Goethe, had an estate worth 24 million when he died on July 10, 1966.[2] Charles Goethe did not have any children, presumably due to Mary's infertility.[citation needed]

Books

• Manuelito of the Red Zerape by C. M. Goethe

See also

• Eugenics in the United States

References

1. Burke, Chloe. "Eugenics in California: Charles Matthias Goethe". Center for Science, History, Policy and Ethics, California State University, Sacramento. Archived from the original on 2015-12-17. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

2. Minna, Alexandra (2016). Eugenic Nation. University of California Press. pp. 69–165.

3. Burke, Chloe S.; Castaneda, Christopher J. (2007). "The Public and Private History of Eugenics: An Introduction". The Public Historian. 29 (3): 5–17. doi:10.1525/tph.2007.29.3.5.

4. Platt, Tony (2005). "Engaging the Past: Charles M. Goethe, American Eugenics, and Sacramento State University". Social Justice. 32: 17–33. JSTOR 29768305.

5. "The World's Largest Summer Camp," Yosemite Nature Notes 37(7):89-94 (July 1958) by Charles M. Goethe. Traces the origin of nature guiding in National Parks; reprinted from Nature Magazine

6. "Nature Study in National Parks Interpretive Movement," Yosemite Nature Notes 39(7):156-158 (July 1960) by Charles M. Goethe

7. Platt, Tony (February 29, 2004). "Curious historical bedfellows: Sac State and its racist benefactor: After receiving honors aplenty from university, C. M. Goethe left most of his big estate to it". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on 1 July 2004. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

8. Allen, Garland E. (2013). "'Culling the Herd': Eugenics and the Conservation Movement in the United States, 1900-1940". Journal of the History of Biology. 46: 31–72.

9. Beckner, Chrisanne (February 19, 2004). "Darkness on the edge of campus". Sacramento News and Review.

10. SFGate.com - 'Eugenics and the Nazis -- the California connection', Edwin Black, San Francisco Chronicle (November 9, 2003)

11. News10.net - Search Results[permanent dead link]

12. News - Goethe name is gone from park - sacbee.com[permanent dead link]

13. - River Bend favored as new name for Goethe Park - sacbee.com[permanent dead link]

External links

• StateHornet.com[permanent dead link] - 'Online petition seeks to change name of arboretum', David Martin Olson, State Hornet (February 4, 2005)

• TimesOnline.co.uk - 'Liberal California confronts years of forced sterilisation', Chris Ayres, Sunday Times (July 11, 2003)

• 'School to erase Goethe name? Staffers say honoring man with racist views insults the students.', Dorothy Korber, "The Sacramento Bee" (February 15, 2007)

• 'Ugly side of philanthropist divides (California State University, Sacramento)', Eric Stern, Bee Staff Writer, "The Sacramento Bee" (March 1, 2007)

• 'Goethe recalled fondly by some', Eric Stern, Bee Staff Writer, "The Sacramento Bee" (March 2, 2007)

********************************

California’s ‘number one citizen’ was a white supremacist, and he founded a state university: Charles M. Goethe, a wealthy eugenicist, was praised by the governor

by Stephanie Buck

Timeline

Sep 17, 2017

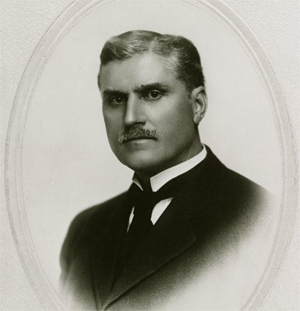

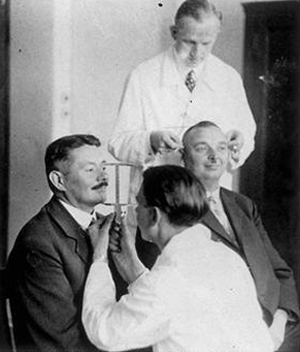

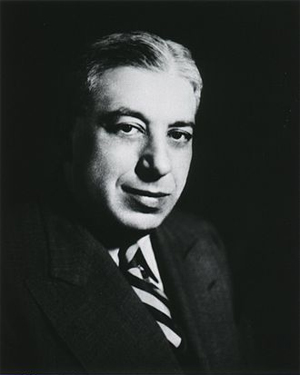

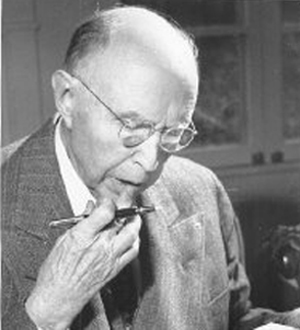

Like his counterparts in Nazi Germany, Charles Goethe espoused eugenic methods of birth control as a means to preserve the aryan race. (Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

Charles M. Goethe invested a lot of money and philanthropy into Northern California. His environmental work earned him a prestigious park in his name, not to mention a school and some shiny plaques. He did good. He also believed white people were the superior race and needed to biologically quarantine themselves from diseased, delinquent Mexicans. If he could prevent brown people from procreating all together, even better.

At the time, this version of white supremacy didn’t stop politicians, educators, and community leaders from singing his praises. In fact, by mid century, Goethe’s name (pronounced “gay-tee”) was everywhere, enshrined in public parks and schools around the state capital. But after his death, and after decades of sanitizing the past, Goethe’s troubling legacy tumbled out.

American eugenics simmered in the early 20th century, then boiled into the 1920s and 1930s. Goethe was a strong force in advancing the conversation. He feared that Nordic people’s historical “contributions to all mankind” were under threat by “the coming of heterogeneity.” Under a guise of protecting this group, who, in California he interpreted as the state’s earliest pioneers, he founded the Immigration Study Commission in the early 1920s. Its target was “low powers,” otherwise known as Mestizos and Mexicans, that were infecting the nation’s “germ plasm,” according to Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (2015).

In 1927, he wrote to the Santa Cruz Sentinel, “The Anglo-Saxon birthrate is low. Peons multiply like rabbits….If race remains absolutely pure, and if an old American-Nordic family averages three children while an incoming Mexican peon family averages seven, by the fifth generation, the proportion of white Nordics to Mexican peons descended from these two families would be as 243 to 16,807.”

Goethe lobbied to close the border and instructed his real-estate brokers not to sell to Mexican people, who he viewed as sub-intelligent criminals.

Eugenics gave “the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable,” according to one of its founders, Francis Galton. Eugenicists inferred that heredity proved humans were inherently unequal, and race was the primary marker of not only inferior and superior genes but also of social supremacy. Leaders in the movement claimed brown and black populations suffered from inferior health due primarily to intrinsically flawed biology. But the wealth and social influence enjoyed by Anglo-Saxon populations was proof of a vast intellectual edge, too. To protect whites from “contamination” was considered, by eugenicists, a noble cause in the purification of the human race.

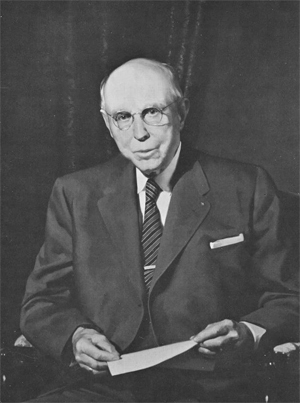

Charles M. Goethe (1875–1966) lived as a respected member of California society. In recent years his bigotry has become a public embarrassment. (CSU Sacramento)

Already a member of several influential eugenics organizations, in 1933 Goethe organized and funded the Eugenics Society of Northern California. Over two decades, he lectured and lobbied with the goal of “reducing biological illiteracy.” During this time, he invested an estimated $1 million to publish pamphlets on racial superiority, family planning, tantrums against racial diversity, and other topics he considered related. In a 1936 presidential address to the national Eugenics Research Association, Goethe publicly defended Nazi Germany’s “honest yearnings for a better population” and proclaimed the country’s sterilization strategy as “administered wisely, and without racial cruelty.” (Two years earlier, Germany had sterilized roughly 5,000 people per month. Hitler praised America’s forced sterilization campaigns, such as Goethe’s, for the idea.) In his speech, Goethe emphasized the duty of Nordic nations to sterilize the “markedly social inadequate, such as those insane, blind, criminal by inheritance.” Between 1907 and 1940, tens of thousands of mostly poor women were involuntarily sterilized in the U.S. At least 20,000 Californians residing in state prisons and hospitals were sterilized before 1964, with laws supported by Goethe.

What made Goethe unique at the time wasn’t necessarily his white supremacist beliefs; it was the fact that he interwove racial pseudoscience with progressive tentpole issues, such as conservation and public education. Throughout his lifetime, he designated several redwood preserves, built playgrounds, financed an orphanage, established ranger programs, contributed to San Francisco’s Academy of Sciences planetarium, and, with his wife Mimi, was considered the founder of the interpretive parks movement. Each of these he considered a step toward the purification of a safer, cleaner, more wholesome, and white America.

His ideologies would conflict modern thinkers for decades, especially after Goethe’s name became the backbone of some of Northern California’s crowning establishments. Students at the California State University, Sacramento, with its commitment to diversity, stroll a campus that may not have existed without a white supremacist benefactor. The school’s arboretum, nestled behind a thicket of trees adjacent to the campus entrance, was named the “C.M. Goethe Arboretum.” The elder benefactor presented personal gifts to faculty members, sometimes via grants but also in the form of travel and “other matters.” In the mid-1960s, Sacramento Mayor James B. McKinney proclaimed March 28 “Dr. Charles M. Goethe Day” in honor of one of the city’s “most outstanding citizens.” The county board of supervisors named Goethe “Sacramento’s most illustrious citizen” and designated a portion of the American River Parkway in his honor; Goethe Park boasted 444 acres of oak trees and wild turkeys. And then there was Charles M. Goethe Middle School.

Praise poured in from media and politicians. In February of 1965, in Goethe’s 90th year, the California State Assembly honored the eugenicist with a resolution. The Sacramento Bee called him a “devoted Sacramentan who has brought national recognition to his city through a lifetime of unlimited contribution.” A telegram from President Lyndon Johnson praised “an American whose life has been so richly dedicated to the service of humanity.” Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren remembered Goethe’s “remarkable career of public service.” Governor Edmund Brown called him “our number one citizen.”

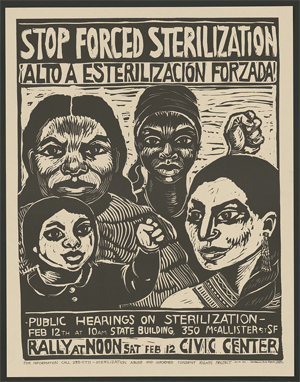

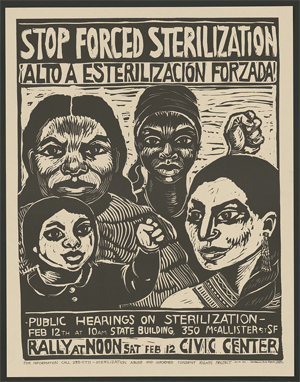

Poster for a 1977 rally against forced sterilization in California. (Rachael Romero/SF Poster Brigade via Library of Congress)

After his death in 1966, CSU Sacramento received a sizable portion of Goethe’s $24 million estate. Yet, in a 2004 paper for the university’s Division of Social Work, Professor Tony Platt reported that the university knew about Goethe’s views on race from the start. “Once his bigotry became a public embarrassment, especially in the context of the anti-racism movements of the mid-1960s and 1970s, the administration tried to surgically separate Goethe-the-conservationist from Goethe-the-eugenicist.” For several decades, the matter of benefitting from and decorating a white supremacist went mostly unaddressed.

Then Platt published some of Goethe’s long-buried tracts, which he discovered during his research at CSUS. The issue erupted. Sacramento activists fought to tear down Goethe’s name from the park and the middle school. Opponents claimed that removal was akin to historical erasure and would set a slippery precedent in political correctness. Nevertheless, Goethe Park is now River Bend, and Charles M. Goethe Middle School became Rosa Parks.

Today, another Sacramento elementary school still gets its mail delivered to Goethe Road. Some people would just as soon forget, as if it were that simple.

This article is part of our White Terror U.S.A. collection, covering the shameful history of white supremacy in America.

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/30/20

Charles Matthias Goethe (March 28, 1875 – July 10, 1966)[1] was an American eugenicist, entrepreneur, land developer, philanthropist, conservationist, founder of the Eugenics Society of Northern California, and a native and lifelong resident of Sacramento, California.

Early life

Charles M. Goethe was born on March 28, 1875 in Sacramento California.[2] He pronounced his last name as GAY-tee.[3] Goethe's grandparents had immigrated to California from Germany in the 1870s.[2] Charles’ father was interested in agriculture and wild life. Both men also pursued careers in real estate as Charles made most of his money as a real estate broker.[2] Charles had passed the bar exam but did not pursue a career in law.[4]

As a child, Charles was interested in agriculture, biology, and the human body. In his diary, he kept a record of his diet and exercise, specifically noting days in which his regimen was not sufficient.[2] Goethe's additional childhood interest in various plants and animals evolved as he pressed and catalogued his findings.[2] His ideas concerning nature tied into his later views on eugenics, as he connected the evolution of nature to heredity.[2] Goethe explained in his memoir Seeking to Serve that his original interest in eugenics began as a child.[2]

Nature guide movement

Goethe (German pronunciation: [ˈɡøːtə] and occasionally incorrectly as "Gaytee") wrote admiringly of California’s Forty-Niners, the State’s giant redwood trees, and loved the outdoors. Goethe worked with organizations including the Sierra Club and the Audubon Society.[2] He and his wife have been called "The father and mother of the Nature Guide Movement,' initiating interpretive programs with the U.S. National Park Service.[5] The National Park Service made Goethe the “Honorary Chief Naturalist” for his work in this field.[2] This was motivated by their experience with nature programs in Europe and desire to educate visitors in the U.S. National Parks.[6] His motto was "Learn to Read the Trail-side as a Book." Goethe encouraged the general public to educate themselves about the evolution of nature as well, personally spending time dedicated to learning about different plants and animals.[2] He later introduced the Boy Scouts to Sacramento, due to his interest in furthering biological education for children.[2] As an adult, Goethe was a conservationist who worked to implement park rangers into national parks.[2]

Founder of Sacramento State College

Goethe founded California State University, Sacramento (Sacramento State College at the time), which in turn treated Goethe with the reverence of a founding father, appointed him chairman of the University's advisory board, dedicated the Goethe Arboretum to him in 1961, and organized an elaborate gala and 'national recognition day' to mark his 90th birthday in 1965, when he received letters of appreciation - solicited by his friends at CSUS - from the president of the Nature Conservancy, then-Governor Edmund G. Brown, and then-President Lyndon B. Johnson. As a result, in 1963, Goethe changed his will to make CSUS his primary beneficiary, bequeathing his residence, eugenics library, papers, and $640,000 to the University.[7]

When Goethe died, CSUS received the largest share of his $24 million estate.

Eugenics controversy

Charles Goethe worked near Arizona, focusing on health conditions in the 1920s.[2] Following his work in Arizona, Goethe desired to understand “the extent of the mestizo peril to the American ‘seed stock.'"[2] Essentially, Goethe was determined to discover the threat of Mexicans to the American population, in a eugenic sense. As a result, Goethe created the Immigration Study Commission.[2][4] With the help of his organization, Goethe hoped to ban Mexican entry into the United States of America. In addition, Goethe portrayed Mexicans as carriers of different diseases and germs. While he believed that certain Mexicans could appear as free of disease, they could in fact be silent carriers due to their health practices.[2] His ideas contributed to 1920s perceptions that the American melting pot had begun to integrate germs from certain races, specifically the Mexican race.[2]

Goethe was a strong proponent of positive eugenics.[4] His mentor was eugenicist Madison Grant, with whom he shared strong anti-immigrant beliefs. Like Grant, Goethe promoted his anti-immigrant and racist ideas through pamphlets and other tracts, and he lobbied with politicians and other bureaucrats.[8] Goethe created tiny pamphlets that he distributed to explain his beliefs concerning specific ethnic groups.[2] In these booklets, he explained the importance of family planning and eugenic practices to ensure the superiority of certain races. He invested nearly 1 million dollars to produce and distribute these pamphlets to increase biological literacy.[2] In addition to investing in these booklets, Goethe also invested in research for plant and biological genetics.[2]

Goethe also recommended compulsory sterilization of the 'socially unfit', opposed immigration, and praised German scientists who used a comprehensive sterilization program to 'purify' the Aryan race before the outbreak of World War II. Goethe also funded anti-Asian campaigns, praised the Nazis before and after World War II, and practiced discrimination in his business dealings, refusing to sell real estate to Mexicans and Asians.

Goethe believed a variety of social successes (wealth, leadership, intellectual discoveries) and social problems (poverty, illegitimacy, crime and mental illness) could be traced to inherited biological attributes associated with 'racial temperament'.

Working with the Human Betterment Foundation in Pasadena, California, Goethe lobbied the State to restrict immigration from Mexico and carry out involuntary sterilizations of mostly poor women, defined as 'feeble-minded' or 'socially inadequate' by medical authorities between 1909 and the 1960s.[7][9]

Goethe was also involved in the publication of multiple journals in which he expressed his views on eugenics. Goethe was involved with the journal Survey Graphic, serving as a member of the council. The journal had published information about typhus quarantines in Mexico in both 1916 and 1917.[2] In addition to Survey Graphic, Goethe was also featured in the journal Eugenics and explained his beliefs that Mexicans were the dirt of society.[2] In the journal from the American Eugenics Society, he explained that Mexicans were as low as Negros, and did not understand basic health rules, but also resisted healthy practices.[2] In his articles, Goethe also explained that Mexicans and South Europeans were responsible for stealing jobs from Americans and introducing germs to the people.[2]

Upon return from a trip to Germany 1934, which at the time was sterilizing over 5,000 citizens per month, Goethe reportedly told a fellow eugenicist, "You will be interested to know that your work has played a powerful part in shaping the opinions of the group of intellectuals who are behind Hitler in this epoch-making program. Everywhere I sensed that their opinions have been tremendously stimulated by American thought...I want you, my dear friend, to carry this thought with you for the rest of your life, that you have really jolted into action a great government of 60 million people."[9] The Nazi eugenics movement eventually escalated to become The Holocaust, which claimed the lives of well over 10 million 'undesirables', including 6 million Jews.

In Sacramento, during Goethe's life, the advocacy of eugenics -the social philosophy of attempting to 'improve' the human population by artificial selection - was considered a progressive issue. Though it was opposed by many scientists who thought the understanding of human heredity was too shallow to create solid policy, and by religious leaders who opposed birth control of any form, in the years after the Holocaust it was not considered to be as radical as it is today.[9] Around 20,000 patients in California State psychiatric hospital were sterilized with minimal or non-existent consent given between 1909 and 1950, when the law went into general disuse before its repeal in the 1960s. A favorable report by Human Betterment Foundation workers E.S. Gosney and Paul B. Popenoe, touting the results of the sterilizations in California, was published in the late 1920s, which in turn was often cited by the Nazi government as evidence wide-reaching sterilization programs were feasible and humane.[10] When Nazi administrators went on trial for war crimes in Nuremberg after World War II, they justified their mass-sterilizations by pointing at the United States as their inspiration.

CSUS attempted to name a new science building after him in 1965, but that effort was rebuffed by students and teachers.[7] In 2005, the university changed the name of its arboretum and botanic garden from the Charles M. Goethe Arboretum to the University Arboretum without fanfare because of renewed attention to Goethe's virulently racist views, praise of Nazi Germany, and advocacy for eugenics.

On June 21, 2007, the school board of the Sacramento City Unified School District voted to rename the "Charles M. Goethe Middle School" to the "Rosa Parks Middle School".[11]

On January 29, 2008, the Sacramento Board of Supervisors stripped his name from one of Sacramento County's busiest parks.[12] On April 25, 2008, the Sacramento Bee reported that, with a nod from Internet voters and the county parks commission, the park will be renamed River Bend Park.[13]

Personal life

Charles Goethe married Mary Glide in 1903.[2] Glide came from a wealthy family and Goethe attempted to court Mary nine times before she accepted his offer.[2] According to Goethe, his wife Mary had refused his proposals since she feared that he was solely interested in her wealth. In addition, she rejected his attempts due to the fact that she was struggling with infertility.[2] The Goethes owned multiple ranches and invested money in the stock market, becoming a wealthy and lucrative family.[2] At the time of her death in 1946, Mary's estate was worth 1.5 million.[2] Her husband, Charles Goethe, had an estate worth 24 million when he died on July 10, 1966.[2] Charles Goethe did not have any children, presumably due to Mary's infertility.[citation needed]

Books

• Manuelito of the Red Zerape by C. M. Goethe

See also

• Eugenics in the United States

References

1. Burke, Chloe. "Eugenics in California: Charles Matthias Goethe". Center for Science, History, Policy and Ethics, California State University, Sacramento. Archived from the original on 2015-12-17. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

2. Minna, Alexandra (2016). Eugenic Nation. University of California Press. pp. 69–165.

3. Burke, Chloe S.; Castaneda, Christopher J. (2007). "The Public and Private History of Eugenics: An Introduction". The Public Historian. 29 (3): 5–17. doi:10.1525/tph.2007.29.3.5.

4. Platt, Tony (2005). "Engaging the Past: Charles M. Goethe, American Eugenics, and Sacramento State University". Social Justice. 32: 17–33. JSTOR 29768305.

5. "The World's Largest Summer Camp," Yosemite Nature Notes 37(7):89-94 (July 1958) by Charles M. Goethe. Traces the origin of nature guiding in National Parks; reprinted from Nature Magazine

6. "Nature Study in National Parks Interpretive Movement," Yosemite Nature Notes 39(7):156-158 (July 1960) by Charles M. Goethe

7. Platt, Tony (February 29, 2004). "Curious historical bedfellows: Sac State and its racist benefactor: After receiving honors aplenty from university, C. M. Goethe left most of his big estate to it". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on 1 July 2004. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

8. Allen, Garland E. (2013). "'Culling the Herd': Eugenics and the Conservation Movement in the United States, 1900-1940". Journal of the History of Biology. 46: 31–72.

9. Beckner, Chrisanne (February 19, 2004). "Darkness on the edge of campus". Sacramento News and Review.

10. SFGate.com - 'Eugenics and the Nazis -- the California connection', Edwin Black, San Francisco Chronicle (November 9, 2003)

11. News10.net - Search Results[permanent dead link]

12. News - Goethe name is gone from park - sacbee.com[permanent dead link]

13. - River Bend favored as new name for Goethe Park - sacbee.com[permanent dead link]

External links

• StateHornet.com[permanent dead link] - 'Online petition seeks to change name of arboretum', David Martin Olson, State Hornet (February 4, 2005)

• TimesOnline.co.uk - 'Liberal California confronts years of forced sterilisation', Chris Ayres, Sunday Times (July 11, 2003)

• 'School to erase Goethe name? Staffers say honoring man with racist views insults the students.', Dorothy Korber, "The Sacramento Bee" (February 15, 2007)

• 'Ugly side of philanthropist divides (California State University, Sacramento)', Eric Stern, Bee Staff Writer, "The Sacramento Bee" (March 1, 2007)

• 'Goethe recalled fondly by some', Eric Stern, Bee Staff Writer, "The Sacramento Bee" (March 2, 2007)

********************************

California’s ‘number one citizen’ was a white supremacist, and he founded a state university: Charles M. Goethe, a wealthy eugenicist, was praised by the governor

by Stephanie Buck

Timeline

Sep 17, 2017

Like his counterparts in Nazi Germany, Charles Goethe espoused eugenic methods of birth control as a means to preserve the aryan race. (Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

Charles M. Goethe invested a lot of money and philanthropy into Northern California. His environmental work earned him a prestigious park in his name, not to mention a school and some shiny plaques. He did good. He also believed white people were the superior race and needed to biologically quarantine themselves from diseased, delinquent Mexicans. If he could prevent brown people from procreating all together, even better.

At the time, this version of white supremacy didn’t stop politicians, educators, and community leaders from singing his praises. In fact, by mid century, Goethe’s name (pronounced “gay-tee”) was everywhere, enshrined in public parks and schools around the state capital. But after his death, and after decades of sanitizing the past, Goethe’s troubling legacy tumbled out.

American eugenics simmered in the early 20th century, then boiled into the 1920s and 1930s. Goethe was a strong force in advancing the conversation. He feared that Nordic people’s historical “contributions to all mankind” were under threat by “the coming of heterogeneity.” Under a guise of protecting this group, who, in California he interpreted as the state’s earliest pioneers, he founded the Immigration Study Commission in the early 1920s. Its target was “low powers,” otherwise known as Mestizos and Mexicans, that were infecting the nation’s “germ plasm,” according to Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (2015).

In 1927, he wrote to the Santa Cruz Sentinel, “The Anglo-Saxon birthrate is low. Peons multiply like rabbits….If race remains absolutely pure, and if an old American-Nordic family averages three children while an incoming Mexican peon family averages seven, by the fifth generation, the proportion of white Nordics to Mexican peons descended from these two families would be as 243 to 16,807.”

Goethe lobbied to close the border and instructed his real-estate brokers not to sell to Mexican people, who he viewed as sub-intelligent criminals.

Eugenics gave “the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable,” according to one of its founders, Francis Galton. Eugenicists inferred that heredity proved humans were inherently unequal, and race was the primary marker of not only inferior and superior genes but also of social supremacy. Leaders in the movement claimed brown and black populations suffered from inferior health due primarily to intrinsically flawed biology. But the wealth and social influence enjoyed by Anglo-Saxon populations was proof of a vast intellectual edge, too. To protect whites from “contamination” was considered, by eugenicists, a noble cause in the purification of the human race.

Charles M. Goethe (1875–1966) lived as a respected member of California society. In recent years his bigotry has become a public embarrassment. (CSU Sacramento)

Already a member of several influential eugenics organizations, in 1933 Goethe organized and funded the Eugenics Society of Northern California. Over two decades, he lectured and lobbied with the goal of “reducing biological illiteracy.” During this time, he invested an estimated $1 million to publish pamphlets on racial superiority, family planning, tantrums against racial diversity, and other topics he considered related. In a 1936 presidential address to the national Eugenics Research Association, Goethe publicly defended Nazi Germany’s “honest yearnings for a better population” and proclaimed the country’s sterilization strategy as “administered wisely, and without racial cruelty.” (Two years earlier, Germany had sterilized roughly 5,000 people per month. Hitler praised America’s forced sterilization campaigns, such as Goethe’s, for the idea.) In his speech, Goethe emphasized the duty of Nordic nations to sterilize the “markedly social inadequate, such as those insane, blind, criminal by inheritance.” Between 1907 and 1940, tens of thousands of mostly poor women were involuntarily sterilized in the U.S. At least 20,000 Californians residing in state prisons and hospitals were sterilized before 1964, with laws supported by Goethe.

What made Goethe unique at the time wasn’t necessarily his white supremacist beliefs; it was the fact that he interwove racial pseudoscience with progressive tentpole issues, such as conservation and public education. Throughout his lifetime, he designated several redwood preserves, built playgrounds, financed an orphanage, established ranger programs, contributed to San Francisco’s Academy of Sciences planetarium, and, with his wife Mimi, was considered the founder of the interpretive parks movement. Each of these he considered a step toward the purification of a safer, cleaner, more wholesome, and white America.

His ideologies would conflict modern thinkers for decades, especially after Goethe’s name became the backbone of some of Northern California’s crowning establishments. Students at the California State University, Sacramento, with its commitment to diversity, stroll a campus that may not have existed without a white supremacist benefactor. The school’s arboretum, nestled behind a thicket of trees adjacent to the campus entrance, was named the “C.M. Goethe Arboretum.” The elder benefactor presented personal gifts to faculty members, sometimes via grants but also in the form of travel and “other matters.” In the mid-1960s, Sacramento Mayor James B. McKinney proclaimed March 28 “Dr. Charles M. Goethe Day” in honor of one of the city’s “most outstanding citizens.” The county board of supervisors named Goethe “Sacramento’s most illustrious citizen” and designated a portion of the American River Parkway in his honor; Goethe Park boasted 444 acres of oak trees and wild turkeys. And then there was Charles M. Goethe Middle School.

Praise poured in from media and politicians. In February of 1965, in Goethe’s 90th year, the California State Assembly honored the eugenicist with a resolution. The Sacramento Bee called him a “devoted Sacramentan who has brought national recognition to his city through a lifetime of unlimited contribution.” A telegram from President Lyndon Johnson praised “an American whose life has been so richly dedicated to the service of humanity.” Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren remembered Goethe’s “remarkable career of public service.” Governor Edmund Brown called him “our number one citizen.”

Poster for a 1977 rally against forced sterilization in California. (Rachael Romero/SF Poster Brigade via Library of Congress)

After his death in 1966, CSU Sacramento received a sizable portion of Goethe’s $24 million estate. Yet, in a 2004 paper for the university’s Division of Social Work, Professor Tony Platt reported that the university knew about Goethe’s views on race from the start. “Once his bigotry became a public embarrassment, especially in the context of the anti-racism movements of the mid-1960s and 1970s, the administration tried to surgically separate Goethe-the-conservationist from Goethe-the-eugenicist.” For several decades, the matter of benefitting from and decorating a white supremacist went mostly unaddressed.

Then Platt published some of Goethe’s long-buried tracts, which he discovered during his research at CSUS. The issue erupted. Sacramento activists fought to tear down Goethe’s name from the park and the middle school. Opponents claimed that removal was akin to historical erasure and would set a slippery precedent in political correctness. Nevertheless, Goethe Park is now River Bend, and Charles M. Goethe Middle School became Rosa Parks.

Today, another Sacramento elementary school still gets its mail delivered to Goethe Road. Some people would just as soon forget, as if it were that simple.

This article is part of our White Terror U.S.A. collection, covering the shameful history of white supremacy in America.