Part 5 of __

But this success was not to last. The mad sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq died in the year 1351 while out on campaign to crush a Turkic tribe in the mountains of Pakistan. The exact cause of his death is unknown,

but one scholar of the time reported the news with the following quip. The sultan was rid of the people, and the people of the sultan. But despite his erratic and tyrannical ruling style, it's clear that something in the harsh character of Muhammad bin Tughlaq had been acting to hold the empire together. After his death, the sultanate of Delhi

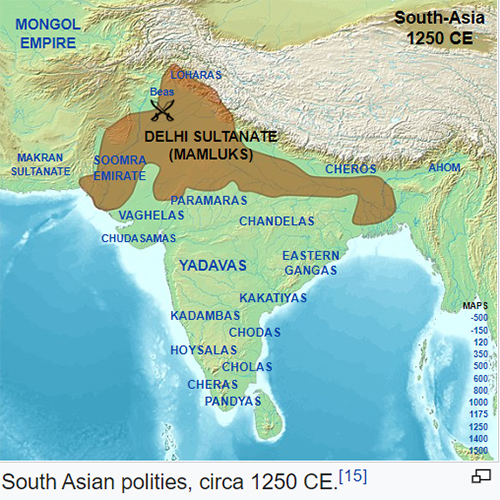

began to disintegrate, and all its newly conquered lands rose up in rebellion. Soon, a war of succession tore the Delhi Sultanate into multiple factions, with nobles across the empire setting up their own states and declaring freedom. The year

1345 is the last year that imperial coins were minted in South India. The following years saw the empire devolve into anarchy and disintegration,

and opportunist enemies waiting behind the mountains to the north soon got word of this.

One of those enemies was the Turko Mongolian warlord and emperor known as

Timur, the last of the great nomadic conquerors of the Eurasian steppe. After hearing of the weakness of the Delhi Sultanate,

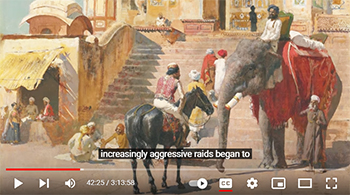

Timur marched his army south to Delhi in the year 1398, plundering and killing all

the way. When he reached the city, he utterly sacked it, looted it, and put its people to the sword. Estimates for the casualties in this

massacre go as high as 200,000 people. Timur himself would later write the following slightly unconvincing account of the atrocity. There was likewise an immense loot of rubies, diamonds, garnets, pearls, and other gems,

vessels of gold and silver, and brocades and silks of great value. Excepting the quarter of the Sayyids, the

scholars, and the other Mussulmans, the whole city was sacked. The pen of fate had written down their destiny for the people of this city. Although I was desirous of sparing them, I could not succeed, for it was the will of god that this calamity should befall the city. Timur had no intention of staying in India.

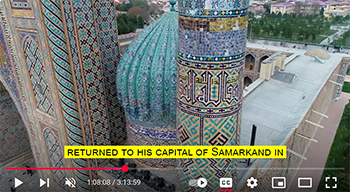

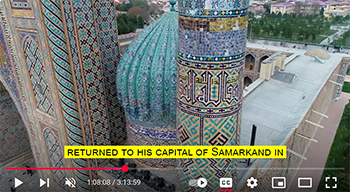

He simply collected up all the wealth he could loot, along with countless enslaved

people, particularly skilled artisans, and

returned to his capital of Samarkand in modern Uzbekistan. Like the sacking of Rome, Timur's sack of

Delhi tore the heart out of this already struggling empire. The dynasties that followed had no

ability to maintain their far-flung territories, and would now be little more than local warlords.

The people and lands that had once been part of the empire were left in a state of anarchy, chaos, and plague. It was a time of immense change, a time of terrible suffering, and for some, a time of enormous opportunity.

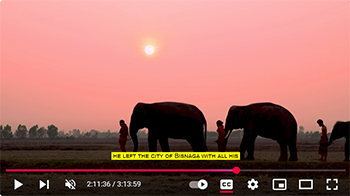

Into this terrain of blood and fire, two brothers would rise from obscure upbringings to change the shape of power in this region,

and it's with these two brothers that the story of Vijayanagara would truly begin. They would move the center of Indian power from the Muslim north to the Hindu south, and build a city there that would stand among the great cities of the medieval world. They were known as the Sangama brothers, and their names were Bukka and Harihara. The exact origins of the Sangama

brothers are wreathed in mystery. Many historians believe that Bukka and Harihara were commanders of the southern Hoysala Empire.

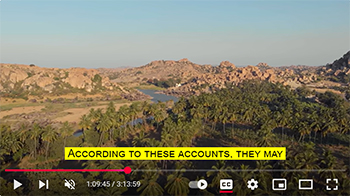

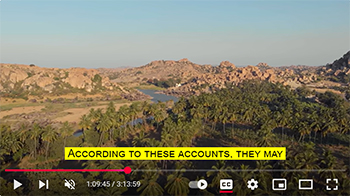

According to these accounts, they may have been stationed on the rocky banks of the Tungabhadra River, with orders to repel any Muslim incursions from the north. Some more dramatic and fanciful stories

recount how the brothers were generals of the conquered Kakatiyas, captured as

prisoners of war, and taken to Delhi where they were forced to convert to Islam, later escaping and converting back to their native faiths. But none of this is mentioned in contemporary sources, meaning that these accounts are likely unreliable. Many of these legends suggest that these

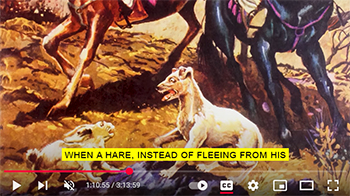

brothers met a Hindu sage named Shri Vidyaranya. One traditional story recalls that Harihara was out hunting one day when he saw a miraculous sight, and the sage advised him on how to interpret it, as

the historian Robert Sewell recounts.

During his reign, this chief was one day hunting amongst the mountains south of the river

when a hare, instead of fleeing from his dogs, flew at them and bit them. The king, astonished at this marvel, was returning homewards, lost in meditation, when he met on the riverbank the sage

named Vidyaranya or Forest of Learning,

who advised the chief to found a city on the spot. So, the king did, and on that very day

began work on his houses, and he enclosed the city roundabout. While this is most likely a fable, it does contain an illuminating image of how the young power of Vijayanagara

would go on to see itself, as the hunted rabbit who had turned around and learned how to bite. As the power of the Delhi Sultanate

collapsed, the two brothers Bukka and Harihara

raised a considerable army made up of angry Hindu lords, but also large cohorts of Muslim mercenaries. These may even have been soldiers who had once fought for the Delhi Sultanate but who were no longer getting paid.

With this force, the brothers set out to capture the areas of South India that the sultanate had left behind. Their offer to Hindu lords in the region was clear; join us, and we will ensure that South

India is run by Hindus,

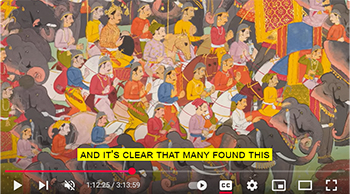

and it's clear that many found this offer irresistible. Within only a few decades, the Sangama

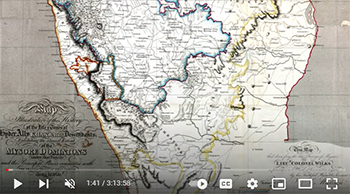

brothers had brought a large part of South India under their control, but many areas in the south were still ruled by Muslim powers,

now cut off and isolated. These included the arid lands of Tamil Nadu, India's southernmost state, which was still ruled by a short-lived Muslim power continuing to fight for its existence in South India, known as the Madurai Sultanate.

At this time, the Sangama brother Bukka was on the throne, and his wife was a

woman named Ganga Devi, a famed poet. She wrote one vaulting, epic poem in the language of Sanskrit entitled Madhura Vijayam, or The Victory of Madurai. In it, she describes how a woman from the holy city of Madurai comes to king

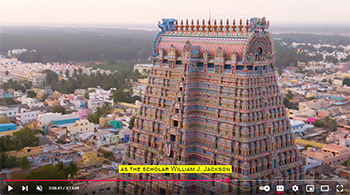

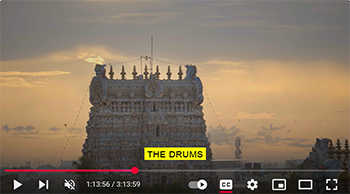

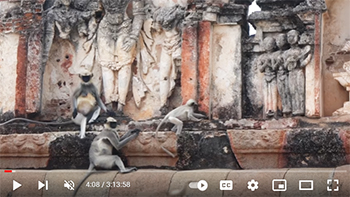

Bukka's court and begs him to take the town back. She describes how the ancient Hindu temples of Madurai had fallen into disrepair under its Muslim rulers. White ants have destroyed the doors.

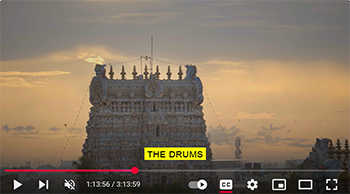

The door frame of the sanctum is broken due to the wild growth of trees, plants, and creepers. The temple premises that formerly echoed the soft beating of the

drums are now full of wild, wallowing jackals. The place once filled with the odor of sacrificial smoke and the melodious chant of Vedic mantras

is now full of the foul smell of meat. The beautiful line of statues that adorn the tall towers of the beautiful buildings in the city are now covered with layers of cobwebs. Whether truly motivated by these religious concerns or not, the Sangama

brothers marched south and quickly conquered the now isolated Madurai Sultanate. With the southern Tamil country now under their control, the Sangama brothers now ruled over a large and wealthy territory.

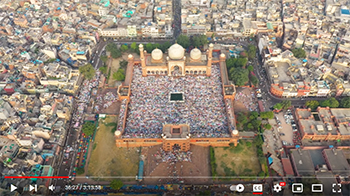

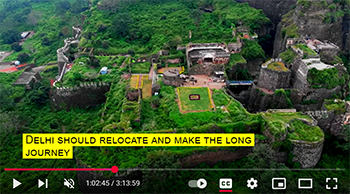

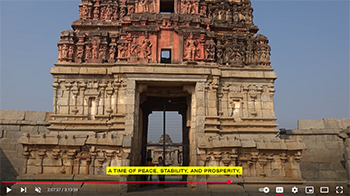

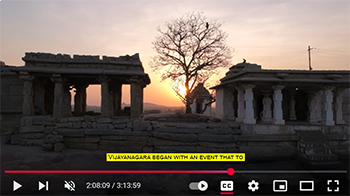

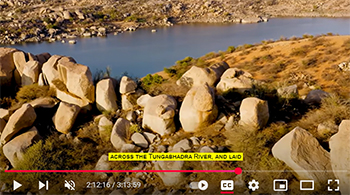

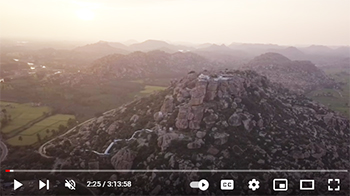

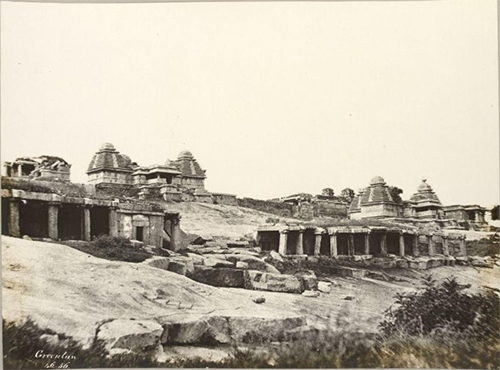

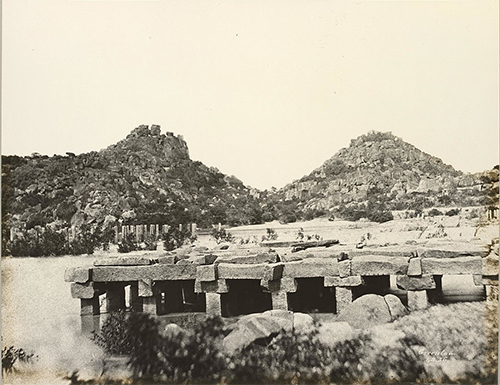

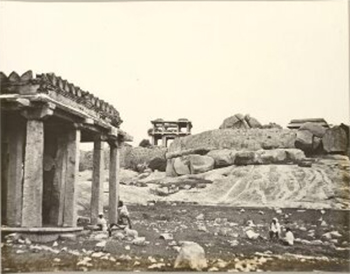

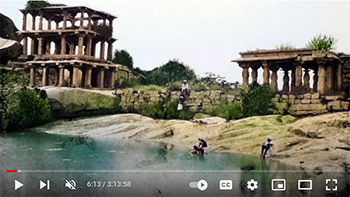

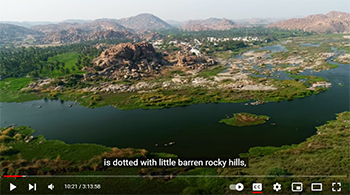

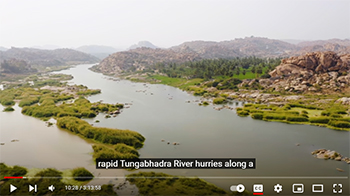

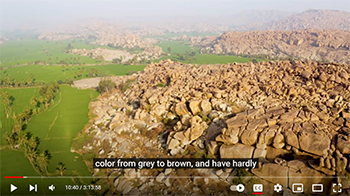

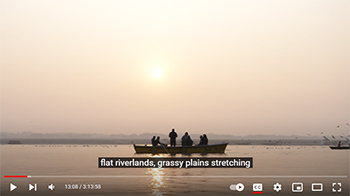

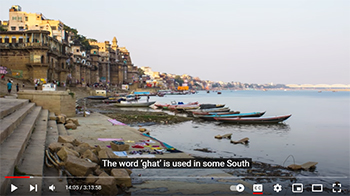

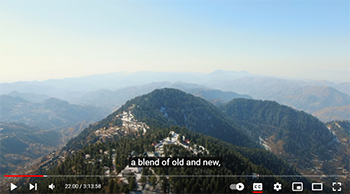

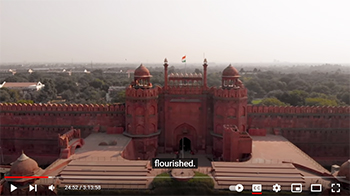

They returned to their former post on the rocky granite banks of the

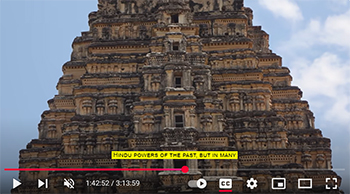

Tungabhadra River. It was an unassuming sight, just a small and fairly insignificant village known only for its shrine to Shiva, a focal point of pilgrimage. But here, they began to build a city that would announce in its size and ambition the arrival of a new confident power in the south of India. They named this city Vijayanagara, from the Sanskrit ‘vijaya’, meaning victory, and ‘nagara’, meaning city, the city of victory.

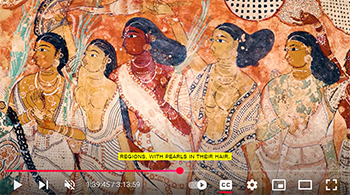

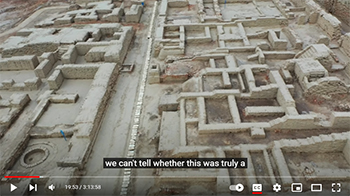

The city that the Sangamas built on the banks of the Tungabhadra River testified to the ambitions that they held for their new kingdom. It would be a city of soaring temples and wide avenues built with an impressive grasp of urban planning, but

the city was also a testament to the dangerous world that they now found themselves at the heart of. They would build Vijayanagara as a

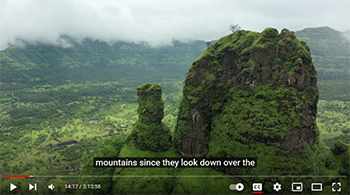

formidable fortress. The impassible granite hills already provided excellent defense while the

wide, torrential Tungabhadra River protected it on the north side, almost impossible for an army to ford. The brothers enhanced these natural defenses by fortifying the passes

between the hills with strong gates and towers, and these massive walls can still be traced in the landscape today,

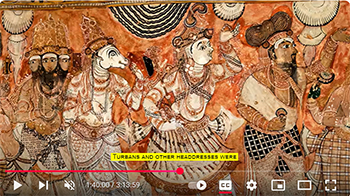

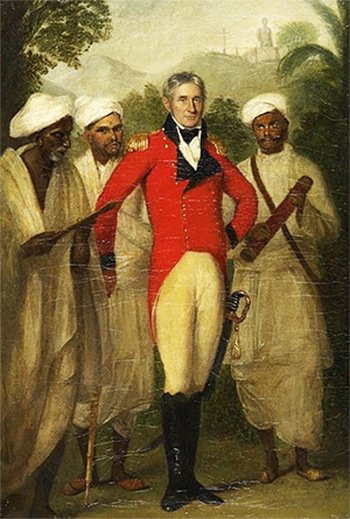

enclosing an area of more than 650 square kilometers. The Afghan envoy Abdur Razzak, who visited

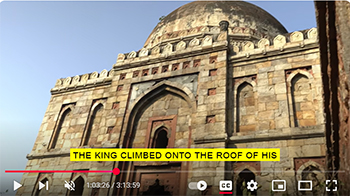

in the 15th century, wrote the following description of the city. It is built in such a manner that seven

citadels and the same number of walls enclose each other. The seventh fortress, which is placed in

the center of the other, occupies an area ten times larger than the marketplace of the city of Herat. It is the place which is used as the residence of the king.

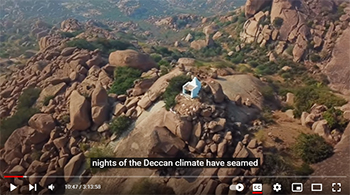

These walls were manned by soldiers who watched from the ramparts, operating watch posts on the broad roads that ran in and out of the city, and in between the layers of walls were areas filled with boulders known as horse stones, designed to disrupt the movement of cavalry and guarantee that any attacking army would have a difficult time advancing while the soldiers of Vijayanagara rained arrow fire down on their heads. When you look at the situation that

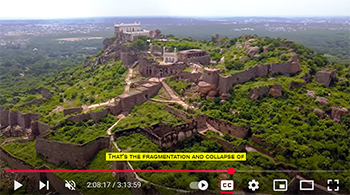

surrounded the city and the new empire of Vijayanagara, it's not hard to see why these defensive fortifications were considered necessary.

That's because the collapse of the Delhi Sultanate had left a number of

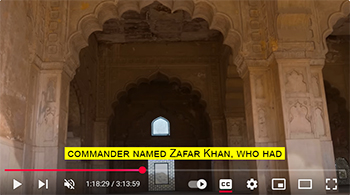

fragmented kingdoms behind, who, like Vijayanagara, rose out of the chaos of the collapsing empire. The most powerful of these in South India was the society known as the Bahmani Sultanate. According to tradition, the Bahmani Sultanate was founded by an army

commander named Zafar Khan, who had served under the erratic sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq. It's clear that at some point he felt the waning power of the Delhi Sultanate in its final years, and in the year 1347, declared himself an independent king in

South India, seizing a large portion of the rocky Deccan Plateau for himself. His gamble paid off;

the weakened Delhi Sultanate, beset with problems on all sides, was no longer able to project its power south of the Vindhya mountains, and it did nothing to stop him. This newly independent power had to fight for its survival from its first days. After defeating one local Hindu ruler,

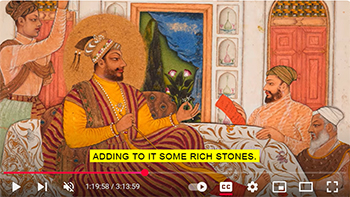

the Bahmani Sultanate received as tribute a magnificent gift, an ornate throne decorated with turquoise enamel that would become a

symbol of their new empire,

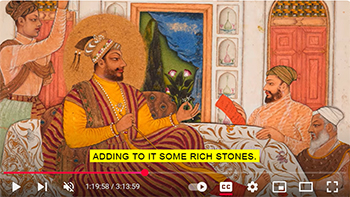

as the chronicler Ferishta recalls. The throne was in length nine feet and three in breadth, made of ebony covered with plates of pure gold, and set with

precious stones of immense value. Every prince of the House of Bahmani who possessed this throne made a point of

adding to it some rich stones. I learned that it was called the Turquoise Throne from being partly enameled of a sky colour, which was in time totally concealed by the number of

jewels. This would become known as the Turquoise

Throne of the Bahmanis, and it would become a symbol of Muslim power in the south of India. Above this throne, they affixed an umbrella, which the scholar Ferishta also gushes about. He fixed a golden ball set with jewels, on which was a bird of paradise composed of precious stones at the top of the umbrella. On the bird's head was a ruby inestimable in value, which had been presented to the late sultan by the king of Vijayanagara.

When this first sultan of the Bahmanis died, with his last words, he declared that his son Mohammed Shah Bahmani would take his throne, and he entreated his sons to stand united and build a kingdom that would stand the test of time, as the chronicler Ferishta writes. I conjure you, as you value the performance of this kingdom, to agree with each other. Mohammed is my successor. Esteem submission and loyalty to him as your duty in this world, and you’re surely for happiness

in the next.

The Bahmani Sultanate was a powerful Muslim kingdom in the heart of South

India that would last for the best part of the next two centuries.

For the Hindu people of Vijayanagara, it represented a constant looming threat on their border. Historians in India and in the West who subscribed to a nationalist idea of history have often framed the conflict

between these two medieval kingdoms in terms of a clash of cultures. In this conception of history, they imagine the Hindu kingdom of

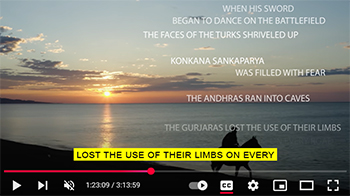

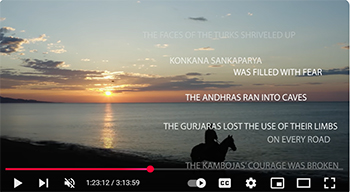

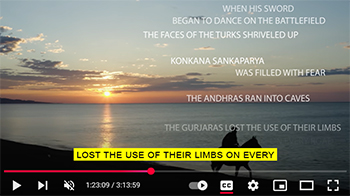

Vijayanagara as a bastion defending Hindu culture from Islamic invaders. But there's little evidence to be found that the people or the rulers of Vijayanagara thought of the situation in this way. One inscription from the time of the Sangama brothers celebrates the victories of the Vijayanagara king Bukka Raya,

and in it, we can see that they thought

of the Turkic Bahmani Sultanate as just one of the many enemies that the kingdom of Vijayanagara faced.

Its other enemies were all Hindu kingdoms.

When his sword began to dance on the battlefield, the faces of the Turks shriveled up, Konkaya Sankaparya was filled with fear, the Andhras ran into caves, the Gurjaras lost the use of their limbs

on every road, the Kambojas’ courage was broken, the Kalingas suffered defeat. Here, there is no mention of religion, and neither is there any hint that the Muslim Bahmanis were any more despicable to the kings of Vijayanagara than say

the Hindu kings of Kalinga on the east coast. There's little evidence that the kings of Vijayanagara thought of themselves as defending Hinduism, and indeed, the idea of a unified Hindu identity simply didn't exist in the 14th century. While the two powers did fight long and bitter wars, the kings of Vijayanagara fought equally bitter wars with the

Hindu Gajapatis, whose kings ruled over

the humid, elephant-filled forest regions to the east. When religious divisions emerged within the kingdom of Vijayanagara, it was overwhelmingly between the followers of Vishnu and Shiva among the Hindus, or between Hindus and Jains. In fact, conflicts between the Bahmani

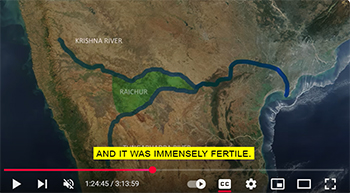

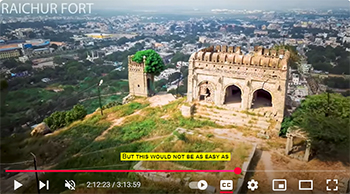

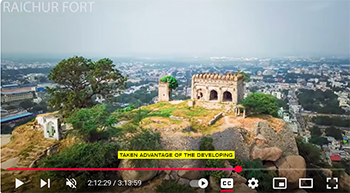

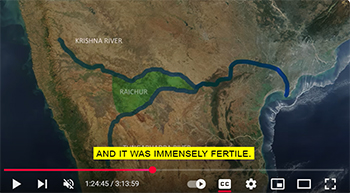

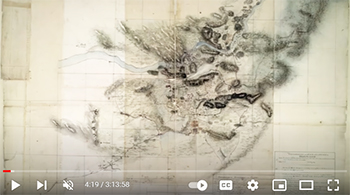

Sultans and Vijayanagara often occurred due to greatly practical economic matters, like access to resources, supply lines, and trade routes. One bitter issue of contention was a rich tract of land

between them known as the Raichur Doab. This was a triangle of land formed at the point where the rivers Krishna and Tungabhadra met,

and it was immensely fertile. But it also held great deposits of iron

and even diamonds. Other conflicts would

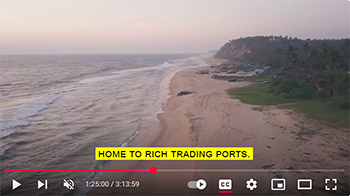

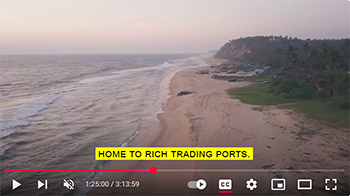

break out over the rich river deltas to the east and the western coast of India,

home to rich trading ports. These ports controlled traffic by sea with the Muslim world, and were a crucial

conduit for the most important strategic military supply of the time; the powerful

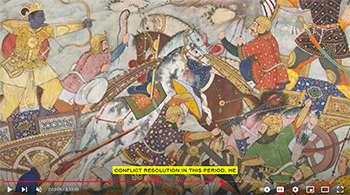

war horses imported from Arabia, Persia, and Central Asia. With these contentious territorial issues always on the minds of their rulers, wars between the Bahmani Sultanate and Vijayanagara broke out constantly.

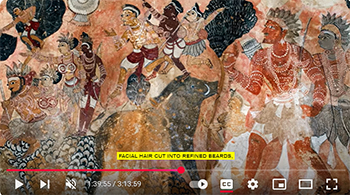

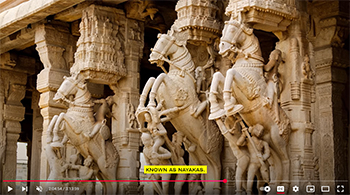

With their connections to the Muslim world, the Bahmanis had the advantage for much of this region's history. Well-supplied with horses, the sultan of the Bahmanis became known as Ashvapati, or the Lord of Horses, while the kings of Vijayanagara were known as or Narapati, or the Lord of Men, alluding to their armies made up of largely massed infantry.

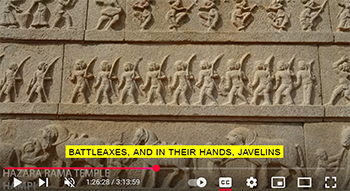

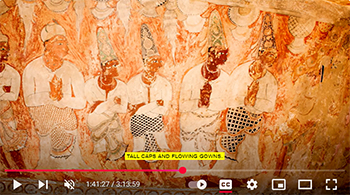

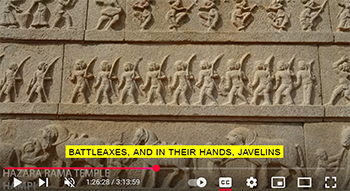

The king of the Hindu Gajapatis in the east, with their vast stables of elephants, completed the triangle and became known as the Lord of Elephants. The Portuguese visitor Domingo Paes was suitably impressed by the infantry of Vijayanagara when he saw them marching in procession in the year 1520. The troops on foot are so many that they surrounded all the valleys and hills in a way with which nothing in the world

can compare. At the waist, they have swords and small

battleaxes, and in their hands, javelins with the shafts covered with gold and silver. You will see amongst them dresses

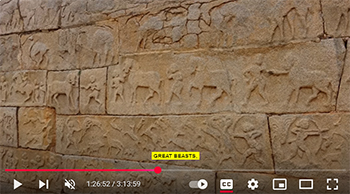

of such rich cloths that I do not know where they came from. Nor could anyone tell you how many colors they have; shield-men with their shields, with many flowers of gold and silver on them, others with figures of tigers and other

great beasts, others all are covered with silver leaf work,

beautifully wrought. But in the early days, they were no match for the horsepower of the Bahmani Sultanate, and with their connections to

the vibrant intellectual world of Muslim learning, the Bahmanis also enjoyed a technological advantage.

One of the first sultans, Mohammed Shah Bahmani, was a keen follower of new technologies. He even established gunpowder factories in the sultanate to

make use of the emerging technology.

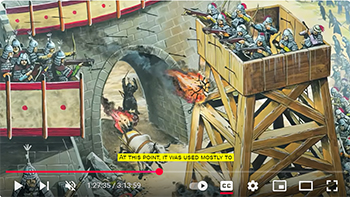

Gunpowder had first been introduced to India and the Middle East by the Mongols, who had learned about it from the Chinese.

At this point, it was used mostly to create burning or exploding projectiles to be fired from catapults, and

occasionally to create crude rockets. But soon, experiments would begin in using it to propel heavy projectiles along metal tubes, first as siege weapons and then as weapons on the battlefield. Soon, the sounds of cannon fire would

ring out over the battlefields of medieval India, and the Bahmani sultans’ early adoption of this technology would put them in a strong position in the

coming centuries. So, although the Hindus of Vijayanagara were the larger and often wealthier kingdom, they often found themselves in the position of paying tribute to their

Muslim neighbours to the north,

whose powerful cavalry armies, soon backed by the technological might of cannons, gave them the upper hand. But these wars were never true wars of conquest. The two powers would fight over a seaport or the rich diamond mines of Raichur between them, but when the war's result became clear, the loser would inevitably sue for peace, agree to pay an enormous sum of money to the victor,

often hand over one of their daughters in marriage, and then they would both return home. There was never any suggestion that one side in this rivalry would ever conquer and consume the other. Still, the growing power of the Bahmanis was of growing concern to the kings of Vijayanagara. Soon, the Bahmani Sultanate stretched right across India from east coast to

west, an unbroken belt that walled off the people of Vijayanagara to the north, that seized the rich lands of Raichur, and meant that the Hindus of the south were

forever looking with fearful eyes to their northern borders. But despite these concerns, the city of

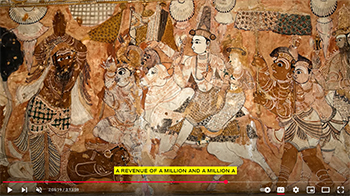

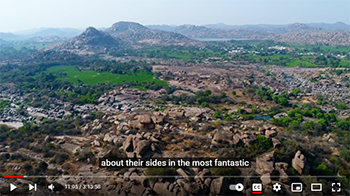

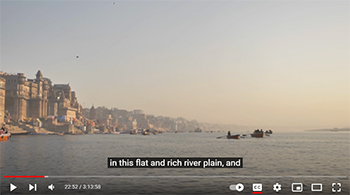

Vijayanagara grew with astonishing speed.

From the mid-14th century, the capital of Vijayanagara grew steadily from the center of a wealthy kingdom

into a great world capital. Thanks to developments in water

management in the countryside, the

population boomed. Enormous work teams would have dug new irrigation systems and reservoirs lined with stone, as well as distinctive step --

wells so that its people could draw water up from the earth.

The city expanded rapidly, sprawling to absorb villages and towns around it, and

soon grew to house as many as 300,000 people at a time when London had only a fifth of that population, and when the

largest city in Europe was Paris, with little more than two hundred thousand. By the year 1500,

Vijayanagara was the world's second -- largest medieval city after Beijing, and probably India's richest. One poet alive at the time of the city's flourishing wrote the following ode to its

beauty. Walk around the great city of victory.

Go where you will on city streets. Everywhere you walk, bright assembly halls decked out with golden vessels will dazzle your eyes.

On many streets, homes with mirrored doors will shine, and sugarcane and plantain all around will invite you with welcomes. You'll find able-bodied fighters and horses, elephants and riders. You'll smell aromas of camphor and musk from breasts of

exquisite doe-eyed women. You will face gardens lush with enjoyments,

precious stones and glowing gold, a city of wealth and glory gleaming. You'll agree that this magnificent city is the most enchanting place you've ever

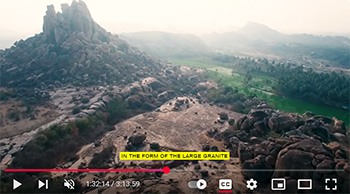

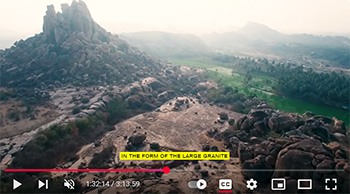

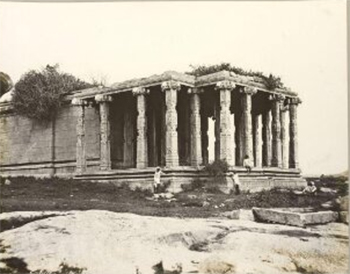

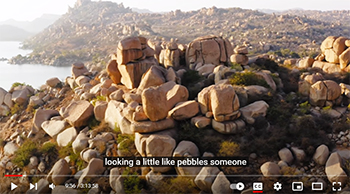

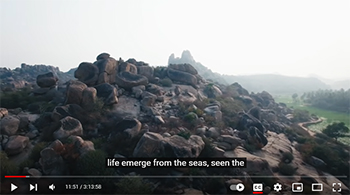

seen. The city also benefited from being surrounded by a seemingly inexhaustible amount of exceptional building material

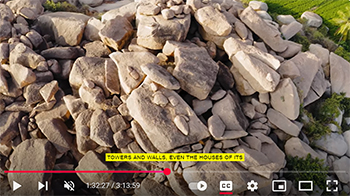

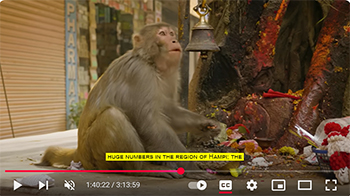

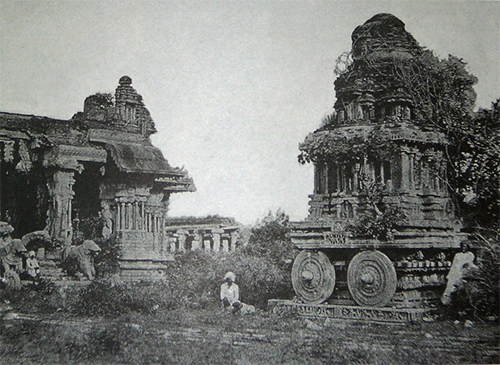

in the form of the large granite boulders of Hampi's ancient terrain. Vijayanagara was truly a city of stone, with all its palaces and stables, its

towers and walls, even the houses of its

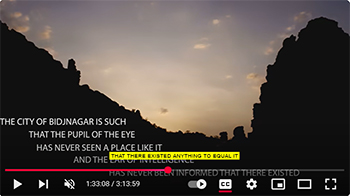

citizens carved out of blocks of solid granite. An ambassador from the Timurid capital of Samarkand named Abdur Razzak, working

as an ambassador for the Persian king, passed through Vijayanagara in the year 1443, and by this time, the city's skyline had grown impressive enough for him to give the following glowing report. The city of Bidjnagar is such that the pupil of the eye has never seen a place like it, and the ear of intelligence has never been informed

that there existed anything to equal it in the world. Vijayanagara would continue to grow. By the early 16th century, some 50 years later, it would be home to as many as half a

million people, and the Portuguese writer Domingo Paes was stunned to see the heights it had reached. The size of the city cannot all be seen from one spot, but I climbed a hill whence I could see a great part of it. I could not see it all because it lies between several ranges of hills. What I saw from then seemed to me as large as Rome

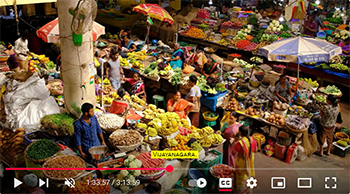

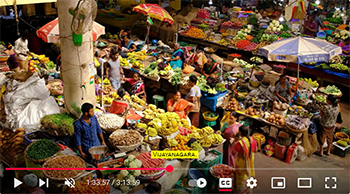

and very beautiful to the sight. Paes was also impressed by the great abundance available in the markets of

Vijayanagara. Going forward, you have a broad and beautiful street,

full of rows of fine houses and streets of sorts I've described, and it is understood that the houses belong to men

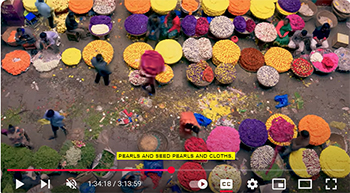

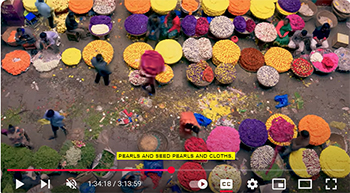

rich enough to afford such. In this city live many merchants, and there you will find all sorts of rubies and diamonds and emeralds and

pearls and seed pearls and cloths, and every other sort of thing there is on the earth that you may wish to buy.

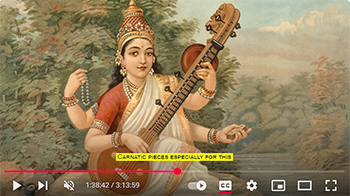

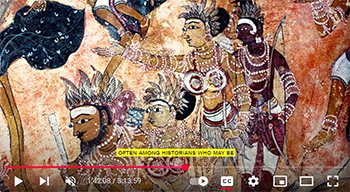

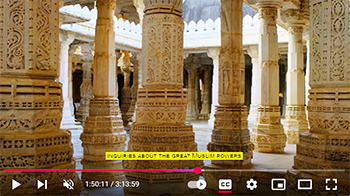

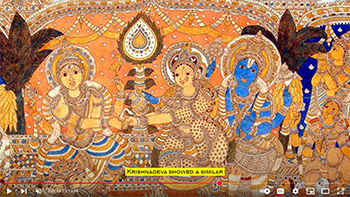

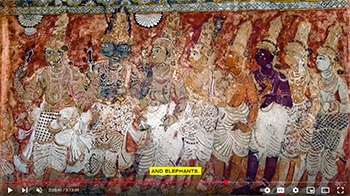

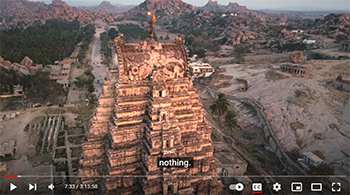

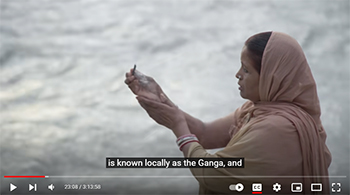

Vijayanagara was divided into a number of different districts, each with a unique character. Near the river was the area known today as the Sacred Center, so called because of the many large temples that can be found here. Here, the

mighty Virupaksha temple still soars up to the sky, with its enormous carved gate tower known as a gopuram. The streets here would have been full of the sounds of chanting hymns and the clanging of temple bells, the smoke of incense, and the pleas of the faithful as they came to pray, to be healed, and to

be closer to the gods.

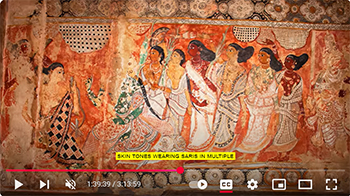

Many of these temples were so large that for tax purposes, they were classed as towns in their own right. These enormous building complexes

supported a huge cast of retainers and specialists, dancers and labourers, cooks and cleaners, as well as scholars, holy men, and artists. Further south is what's been termed the

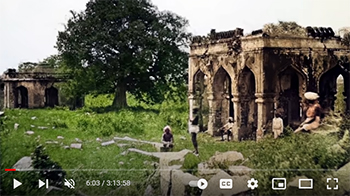

urban core, a walled area of around 20 square kilometers that contains both houses and markets, as well as workshops, rest houses, and other places of business,

as the historian Atul Chandra Chatterjee recalls. The great majority of the houses were naturally small and undistinguished, but

among them were scattered palaces, temples, public buildings, wide streets of shops shaded by trees, busy markets, and all the equipment of a great and wealthy city. Here, the ruined remains of the city

clearly show a great amount of religious diversity.

Local temples here cater to the Jains, as well as Hindu temples for both Vishnu and Shiva followers, and one area with a mosque. The Portuguese traveler Duarte Barbosa, arriving in Vijayanagara around the year 1501, gave the following vivid description of this district. The houses are thatched, but are

nonetheless very well-built and arranged according to occupations in long streets with many open places, and the folk here are ever in such numbers that the streets and places cannot contain them. There is a great traffic and an endless

number of merchants and wealthy men. The king allows such freedom that every man may come and go according to his

creed, without suffering any annoyance, and without inquiry whether he is Christian, Jew, Moor, or Heathen.

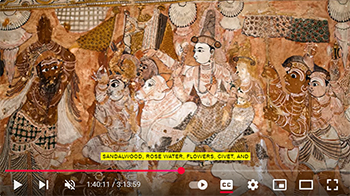

Barbosa also pays particular attention to the smells that would have wafted

through the air from the markets selling spices and perfumes.

Here also is used vermilion, saffron, rose water, a great store of opium, sandalwood, aloes -- wood, camphor musk, and scented materials.

Likewise, much pepper is used here, which they bring from Malabar on donkeys and pack cattle. Here, we can imagine scenes of family life; children running in the streets, wood smoke billowing overhead.

`

`