Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Part 1 of 2

Chapter II: Alexander's Campaigns in India, Excerpt from "Age of the Nandas and Mauryas"

by K.A. Nilakanta Sastri

1952

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

CHAPTER II: ALEXANDER'S CAMPAIGNS IN INDIA

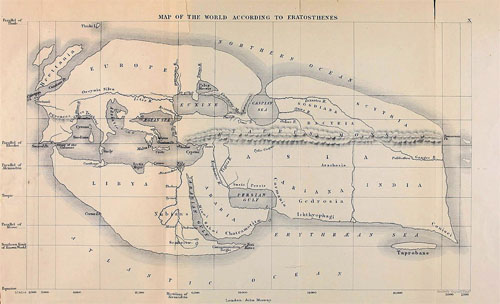

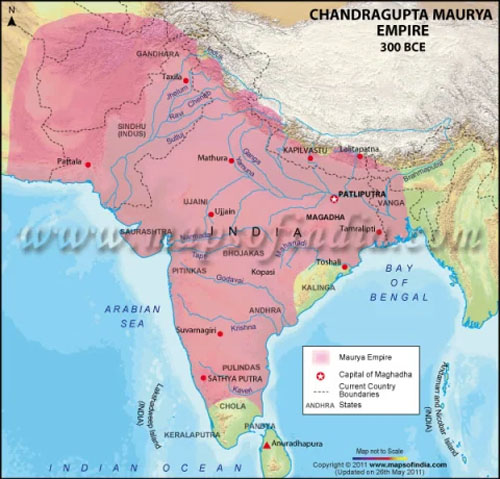

After Alexander’s conquest of Bactria and Sogdiana, the Indian satrapy was the only province of the Persian empire into which he had not carried his arms. Of this province he must have gained some valuable knowledge from Sisikottos (Sasigupta), the Indian mercenary leader who transferred his services from Bactria to her conqueror. Alexander also received an embassy in Sogdiana from Omphis (Ambhi) of Takshasila (Taxila) which offered him the alliance of the Indian prince and sought the foreigner’s aid against his powerful neighbour Porus, the first recorded instance of an Indian seeking foreign aid against fellow Indians.

At the end of the spring of 327 B.C., Alexander started on his Indian expedition leaving Amyntas behind with 3,500 horse and 10,000 foot to hold the land of the Bactrians. He crossed the Central Hindu Kush in ten days following the main road from Balkh to Kabul, and reached the rich and beautiful valley of Koh-i-Daman, where he had already founded an Alexandria, which he now strengthened with fresh recruits from the neighbourhood and from among his war-worn soldiers. He placed Nicanor in charge of the city, and appointed Tyriespes satrap of the area, dispositions intended, as was, usual with Alexander, to secure his rear before advancing further.

Alexander then proceeded to Nikaia (Greek for ‘city of victory’), a place that lay most likely on his route to the river Kabul. Here he offered a sacrifice to the goddess Athena, and met an Indian embassy headed by the king of Takshasila which ‘brought him such presents as are most esteemed by the Indians’ and gave him also all the elephants they had with them, twenty-five in number.

After leaving Nikaia and at some distance from the city on the way to the Kabul river, Alexander divided his army, and sent one part of it under Hephaestion and Perdiccas to the Indus, along the course of the Kabul river, with instructions to take Peucclaotis (Pushkalavatl, near Gharsadda, N.E. of Peshawar) and other places on the way by force if they would not submit of their own accord. When they reached the Indus they were to make necessary preparations for the transport of the army across that river. We have the name of only one tribal chief, Astes, in the Peucelaotis region (the Yusufzai country) who ventured to offer resistance, and paid for it with his life. His city was captured after thirty days, and in his place was installed Sangaios (Sanjaya ?) who had quarrelled with him some time before and gone over to Taxiles. The boats built by the Greeks on reaching the Indus were such as could be taken to pieces and reassembled on reaching another river (Curtius).

Subjugation of the Swat Valley

With the rest of the army Alexander set forth on a hard campaign in the mountains in order to secure the flank of his main line of communication. The people of these mountain tracts are called Aspasians, Gauraians and Assakenians by Arrian. The first and last of these terms are variants of the same tribal name, Asmaka, a name known to Varahamihira’s list of tribes in North-Western India; the other rendering of the name into Asvaka is supported by the fact that the Greeks translated it into Hippasioi (Hypasioi in Strabo). It is noteworthy that the Pushto name for the Yuzufzai still continues to be Asip or Isap. The Gauraians were doubtless closely connected with them and took their name from the river Gauri (Panjkora), the Gouraios of the Greek texts. They were all obviously Indian tribes and are so described by the Greek writers.

The route taken by Alexander along the Khoes is not easy to follow in its details, but doubtless his operations led him for a considerable distance up the large and populous valley of the Kunar, where he fought many hard battles. In an encounter before the first important city taken by the invaders, Alexander was slightly wounded in the shoulder. The city was razed to the ground and all its inhabitants, excepting those who managed to escape to the hills, were put to the sword. Craterus and some other infantry officers were left behind to complete the subjugation of the district, while Alexander advanced to attack the Aspasians, who abandoned their capital on hearing of his approach, and were pursued with great slaughter to their mountain refuges.

Alexander then crossed the mountains to the east and entered the Bajaur valley. Here Craterus rejoined him after carrying out his orders, and was asked to find fresh inhabitants for the city of Arigaion which occupied an advantageous site, but had been burnt down and deserted by its original residents. Meanwhile Ptolemy, the son of Lagos, spotted the main Indian camp and brought news of its whereabouts to Alexander, who planned an attack against it in three divisions, one of which he led ‘in person against the position occupied by the main body’ of the Indian forces. Confident in the strength of their numbers, the Indians descended from the high ground they held to meet the invader on the plain below and sustained a defeat; the number of prisoners taken by the conqueror is said to have been no less than 40,000; then were captured also 230,000 oxen, from which Alexander chose the best to be sent over to Macedonia for use in agriculture. After the subjugation of the Aspasians, Alexander moved, according to Curtius, to the city of Nysa; Arrian records the visit in detail, but gives no indication of the position of Nysa, and is openly sceptical not only of the legendary details, but of the existence of the city itself. The inhabitants of Nysa offered no resistance, but sent an embassy with presents and claimed kinship with the Greeks on the score that their city had been founded by Dionysus and named after his nurse, Nysa, and that the Nysans were the descendants of his followers; the mountain near the city also bore the name Meros (thigh) because Dionysus grew, before his birth, in the thigh of Zeus. Nysa had remained a free city with its own laws ever since, and Alexander should permit them to continue as they were. ‘It gratified Alexander to hear all this' from Akuphis, the leader of the Nysan deputation, and he was not inclined to be too critical of legends that were pleasing to the ears of his soldiers, and promised him the glory of excelling the achievements of Dionysus. So he offered a sacrifice to his divine predecessor and confirmed his colony in the enjoyment of its ancient laws and liberty as an aristocratic republic. When Alexander asked for three hundred horsemen from Nysa and one hundred of their best men to accompany him, Akuphis smiled and agreed readily to give the horsemen, but offered two hundred of the worst men of Nysa instead of the hundred best demanded by Alexander. The reply by no means displeased Alexander who took the cavalry and waived the other demand. He made a pilgrimage to Mount Meros (Koh-i-Mor ?) where his followers rejoiced at the sight of the ivy and laurel and wove chaplets of them for their heads while they joyfully chanted hymns to the divine forerunner of Alexander.

Marching across the land of the Gauraians and crossing the river Gauri (Panjkora), a difficult task owing to the depth and swiftness of the stream, Alexander appeared before Massaga, ‘the largest city in those parts'. Thus began the war in the upper Swat region against the Assakenoi. This powerful confederation commanded extensive territory including the whole of Swat, Buner and the valleys to the north of Buner, and extending right up to the Indus. It had an army of 20,000 cavalry'1 [Lassen and Stein give 2,000.], and more than 30,000 infantry besides 30 elephants. Yet, it seems to have relied for defence against the invader not on fighting in open battle, but on the fortifications of its walled towns. The Greek accounts of the war contain details of several places besieged and taken by Alexander, but their position can seldom be fixed with confidence on modern maps. Stein, who knew the country very well, suggests that they ‘were probably situated in the main Swat valley; for this at all times must, as now, have been the most fertile and populous portion of the territory'.

The siege of Massaga (Masakavati ?) the capital of the Assakenoi, lasted for four days; at the outset Alexander was wounded in the leg, 'though not severely', by an arrow from the besieged; but the Greek engines of war battered down the defences and inflicted great losses on the besieged, and their chief fell on the fourth day ‘struck by a missile from an engine'. Among the besieged were 7,000 mercenary troop who had no inclination to continue the arduous defence, especially after the death of the ruler of the city, and they started negotiations with Alexander; they were allowed to hill, leave the city, arms in hand, and encamp on a neighbouring on condition that they changed sides and accepted service under Alexander. But they had no wish to aid the foreigner against their countrymen and planned an escape by night to their homes; Alexander heard of this, surrounded their camp and cut them to pieces. Diodorus and Plutarch state that Alexander’s conduct on this occasion was a ‘foul blot on his martial fame’; he had made separate peace with the mercenaries to escape the serious losses they inflicted on his forces, and then fell upon them treacherously. Massaga itself, deprived of its best defenders, was taken by storm, and according to Arrian, the mother and daughter of its ruler became prisoners of war. Curtius records a story that the queen of the city, who had an infant son whom she placed on Alexander’s knees was treated indulgently by the conqueror, rather owing ‘to the charms of her person than to pity for her misfortunes'. He adds that afterwards she gave birth to a child who received the name of Alexander. Justin mentions that the Indians called the queen ‘the royal harlot'.

The final stages of the campaign in the Swat valley centred round Bazira (Bir-kot) and Ora (Udegram). Koinos was sent to Bazira, which was expected to surrender, and three other generals against Ora, with instructions to invest the place until the arrival of Alexander. Bazira, which stood on a lofty eminence and was strongly fortified, offered resistance to Koinos, and on hearing this, Alexander started to conduct the operations there himself. But then he learned of attempts to reinforce Ora, set on foot by Abhisares, the king of Abhisara, territory east of the Indus. Alexander directed his march to that city first, and ordered Koinos to join him there after fortifying a position before Bazira and leaving there a garrison strong enough 'to keep the inhabitants from undisturbed access to their lands’. A sortie by the defenders of Bazira after the departure of Koinos was unsuccessful and they were confined more rigorously than before within the walls their city. Ora was captured at the first assault with little loss to the invader, who took over all the elephants he found there. The news of the fall of Ora led the inhabitants of Bazira to abandon their city at dead of night and seek refuge in the more inaccessible heights of the neighbouring mountains. This was the end of the campaign in the Swat valley; Alexander turned Ora and Massaga into strongholds for guarding the country round about, and improved the defences of Bazira, before marching south towards the Peshawar valley to follow the line taken by Hephaestion and Perdiccas down the Kabul river.

These generals had fortified a town called Orobatis (not identified) on their way to the Indus Alexander now appointed Nicanor satrap of the country west of the Indus, and received the submission of Peucelaotis (Pushkalavati), the ancient capital of Gandhara, stationing a garrison of Macedonian soldiers in the city under the command of Philip. Alexander then spent some days reducing minor strongholds, some on the way to the Indus, and some on its right bank, accompanied by two local chieftains Kophaios and Assagetes (Asvajit ?).

Aornos

Before crossing the Indus, Alexander had still to deal with the last stronghold of the Assakenoi at Aornos to which they had all flocked for refuge. This place has been most satisfactorily located by Stein in the mountain ranges of Pir-sar and Una-sar, which answer to all the topographical details contained in the Greek accounts of Alexander’s operations against Aornos, accounts derived ultimately from Ptolemy, the son of Lagos, who took a prominent part in those operations.

A word may be said at this stage about political conditions in the North-West frontier of India at the time of Alexander’s invasion; the Assakenoi and their neighbouring and allied tribes were supported by Abhisares, and probably also by Porus, in their resistance to the invader; Abhisara proper is the name of the hill country between the upper Jhelum and the Chenab; but the ruler of this territory at this time seems to have extended his sway in the west into Hazara (Ursa) up to the Indus, and on the east his territory might well have included parts of Kashmir. The ruler of Takshailla whose territory lay between the kingdoms of Abhisares and Porus, was on no friendly terms with them, and, as we have already seen, he welcomed the invader, hoping to have his support against his local enemies. It is not surprising then that the Assakenoi prepared themselves to defend their independence in a region impregnable because of its physical features and in close proximity to the territory of Abhisares, and that Alexander did not feel free to accept the welcome of Taxila until he had overthrown this last and most redoubtable stronghold of the tribes whose subjugation was the chief aim of the arduous campaigns he had fought in the Swat valley.

To get at this stronghold on the eastern frontier of the Assakenian country, Alexander had to move some way up the right bank of the Indus to Embolima (Amb), a city within two marches of Aornos. Here he left Craterus with a part of the army to gather into the city as much corn as possible and all other requisites for a prolonged stay, in order that the Macedonians, having that place as a base, might by protracted investment wear out those holding the rock, in case it should not be taken at the first assault. Alexander himself then advanced to the rock, taking with him the archers, the Agrianians, the brigade of Koines, the lightest and best armed of the phalanx, two hundred of the companion cavalry and one hundred horse-archers. He fixed his camp on the second day very near the rock.

Aornos is described by Arrian as a mighty mass of rock, 6,600 ft. in height with a circuit of about 22 miles; Diodorus halves the circuit, puts the height at 9,600 ft., and says that it was washed by the Indus on its southern side. 'It was ascended', says Arrian, ‘by a single path cut by the hand of man, yet difficult. On the summit of the rock there was, it is also said, plenty of pure water which gushed out from a copious spring. There was timber besides, and as much good arable land as required for its cultivation the labour of a thousand men'. A report was current that this stronghold was once assaulted in vain by Hercules who had to abandon the attempt on the occurrence of a ‘violent earthquake and signs from heaven', and this is said to have made Alexander the more eager for the capture of the stronghold. But it should be noted that Arrian discredits the story and says ‘my own conviction is that Herakles was mentioned to make the story of its capture all the more wonderful'.

At first Alexander was at a loss how to proceed to the attack, when some people from the neighbourhood came to him, offered their submission and undertook to guide him to the most accessible portion of the rock, from which the assault on the main eminence would not be difficult. Alexander accepted their guidance and sent with them Ptolemy with a select body of light-armed troops, telling him that on securing the position he was to signal to him and to hold it with a strong force. Traversing a rough and difficult route which led most probably up the valley to the west of the Danda-Nurdai spur, Ptolemy succeeded in occupying the indicated position on the height known as Little Una, unobserved by the defending forces on the heights of Pir-Sar. He fortified his position with a palisade and a trench, and signified his success to Alexander by means of a beacon raised on a height from which it would be seen by Alexander. Alexander did see it, and he moved forward the next day with his army along the route that Ptolemy had taken; but the defenders soon saw what had happened and sent their men to the heights of Danda-Nurdai to obstruct the ascent of Alexander, which they did successfully, and then turned round and attacked the position held by Ptolemy higher up; after severe fighting in the latter part of the day, the Indians failed to carry Ptolemy’s fortifications and retired at nightfall.

During the night, Alexander secured the aid of an Indian deserter and sent a letter to Ptolemy asking him not to be content on the following day with just holding his position but to attack the Indians in the rear when they sought to obstruct the passage of the main army up the hill. At daybreak he started again, and succeeded, after a hard fight in forcing a passage and effecting a junction with Ptolemy’s men. But the assault on the main rock (Pir-Sar) could not be undertaken without much toil in filling up a ravine that lay between his position and the height held, by the defenders. This task was begun the next day and Alexander himself supervised the operations of cutting stakes and piling up a mound towards the main rock. The mound was advanced to a length of 200 yards as a result of the first day’s work, but progress became necessarily slower in the depths of the ravine. The Indians attempted to obstruct the progress of the work and, though by their sallies they inflicted some losses on the enemy, their main object was foiled by the missiles of the Greeks shot from engines which were being advanced along the mound as each section of it was completed. The work of piling up the mound went on for three days without intermission, and on the fourth a few Macedonians succeeded in forcing their way up a small hill and occupying its crest on a level with the rock. The work on the extension of the mound was continued until it was joined three days later to the small hill near the rock that had passed into Greek occupation. Seeing the extraordinary skill with which these daring operations were carried out and the success which attended them, the Indians began to feel that further resistance was hopeless and sent a messenger to Alexander offering to surrender the rock if he granted them terms of capitulation. While the negotiations were dragging on, the besieged formed plans of dispersing to their several homes under cover of night; Alexander saw this, allowed them to begin their retreat without any obstruction, and then with a picked body of seven hundred troops scaled the rock at the point abandoned by the defenders. The surprise was complete; many of the Indians were slaughtered, and many others fell over the precipices and were dashed to death; ‘Alexander thus became master of the rock which had baffled Herakles himself. He celebrated his success by offering sacrifice and worship to the gods and erected altars dedicated to Minerva and Victory. He also built a fort and gave command of it to Sisikottos before setting out to complete the conquest of the Assakenoi and rejoin his main forces on the banks of the Indus. The siege and capture of Aornos may be placed round about the month of April 326 B. C.

From Aornos, records Arrian, Alexander went in pursuit of the fleeing defenders of Aornos, who were led by a brother of the Assakenian chief killed in Massaga. The fugitives had taken refuge in the mountains with an army and some elephants. When Alexander reached Dyrta he found the city and its environs deserted, and thereupon he detached certain troops to reconnoitre the surrounding country and secure information about the enemy, particularly his elephants. Dyrta has not been identified, but the fact that a new road had to be made, without which the march across the country to the Indus would have been impracticable, seems to point to the central parts of Buner as the scene of the operations. From captives Alexander learned that the Indian prince had crossed the Indus and taken refuge with Abhisares, leaving his elephants at pasture near the Indus. These he succeeded in capturing with a loss of only two animals killed in the chase by their falling down a precipice. He also discovered a lot of serviceable timber, which he caused to be floated down the Indus to the bridge constructed long before this by the other section of the army.

When Alexander reached the bridge at Ohind, at the end of sixteen marches, he gave his army a rest of thirty days, entertaining them with games and contests. Here he was met by an embassy from Ambhi of Takshasila who had recently succeeded to his father’s throne, but was awaiting the arrival of Alexander to assume sovereignty. The embassy brought presents consisting of 200 talents of silver, 3,000 fat oxen, 10,000 sheep or more and 30 elephants; a force of 700 horsemen also came to the assistance of Alexander from the same prince and brought word that Ambhi surrendered into Alexander’s hands his capital Takshasila, ‘the greatest of all the cities between the river Indus and Kydaspes’. Alexander then offered sacrifice to the gods on a magnificent scale and found the signs favourable for his crossing into India proper the first European to set his foot on Indian soil.

Taxila

As the invader approached Takshasila a strange incident occurred. When he was at a distance of some four miles from the city, he was met by a whole army drawn in battle order and elephants ranged in a line; Alexander suspected treachery and instructed his troops to prepare for a battle; but Ambhi seeing the mistake made by the Macedonians, left his army with a few friends and contrived to explain to Alexander, with the aid of an interpreter, that he meant not to fight, but to honour his foreign ally whose protection he had been soliciting for so long and with so much persistence. He surrendered himself, his army and kingdom into the hands of Alexander, and got them back as his favoured protege.

Alexander was entertained in Takshasila for three days with lavish hospitality, and on the fourth day he and his friends received presents of golden crowns and eighty talents of coined silver (Curtius). In his turn Alexander showed his gratification by sending to Ambhi a thousand talents from his spoils of war ‘along with many banqueting vessels of gold and silver, a vast quantity of Persian drapery, and thirty chargers from his own stalls, caparisoned as when ridden by himself'. Thus did a fraction of the loot from the store-houses of the old Persian kings find its lodgement in the palace of Takshasila. But Alexander’s liberality on the occasion displeased some of the Macedonian generals, though it secured for him an additional force of five thousand men and the unfailing loyalty of a most useful ally. Embassies from Indian princes met Alexander here with presents and declared their submission to him; even Abhisares of the hill country sent his brother. Only Porus (Paurava), bearer of a great name coming down from the age of the Rigveda, sent a defiant reply to Alexander’s message and said he would meet the invader at the frontier of his territory, but in arms. Porus was the ruler of a considerable kingdom, and its expansion was doubtless causing some stir among the neighbouring kings and tribes, and bringing about the political alliances and groupings among them at the time.

Preparing to leave Takshasila for the encounter with Porus, Alexander offered the customary sacrifices and celebrated a gymnastic and equestrian contest. He sent Koinos back to the Indus to dismantle the bridge of boats and bring it over to the Jhelum river, the ancient (Vitasta, the Hydaspes of the Greeks). He posted Philip, the son of Machatus, at the head of a garrison, as satrap of Takshasila and its neighbourhood, and began his march to the Jhelum with his own army and the Taxilan contingent of 5,000 men commanded by their king in person. The route lay in a south-easterly direction over difficult country and was about a hundred miles in length. On his march Alexander found a defile on his road occupied by Spitaces, a nephew of Porus, with a body of troops; these he soon dispersed, and then completed his march without encountering any further opposition; Spitaces fought later on the side of his uncle and fell in the battle of the Jhelum.

Battle of the Jhelum

Alexander fixed his camp in the vicinity of the town of Jhelum on the right bank of the river; it was the spring of 326 B.C. Porus had ranged his entire forces on the opposite side, and stationed posts at various points up and down the river to watch the enemy’s movements and give the alarm when he attempted to cross the river. The Paurava’s army drawn from the populous villages of his principality was an imposing force. Arrian records that in the final encounter with Alexander, he employed all his cavalry, 4,000 strong, all his chariots, 300 in number, 200 of his elephants, and 30,000 efficient infantry. We should add to these numbers the 2,000 men and 120 chariots he detached earlier in the day under his son's charge to meet the enemy as he was crossing the river, as also the considerable section of the army he left behind in his original camp to oppose the crossing of the troops that Alexander left behind in his camp on the opposite bank. Alexander's army on the other side was made up of many elements; the heavy-armed Macedonian infantry carrying the long spear in phalanxes; and the highly disciplined cavalry, the ‘Companions’ of the king who were drawn from the aristocracy of Macedon and formed the core of the force. The original 2,000 Companions were much reduced in numbers and the four hipparchies into which they were now reorganised contained only one Macedonian squadron each. There were also mercenary soldiers in thousands from the Greek cities and half-civilized hill-men from the Balkan lands serving as light troops. But mingled with the Europeans were men of many nations. Here were troops of horsemen, representing the chivalry of Iran, which had followed Alexander from Bactria and beyond, Pashtus of the Hindu Kush with their highland-bred horses, Central Asiatics who could ride and shoot at the same time; and among the camp followers one could find groups representing the older civilizations of the world, Phoenicians inheriting an immemorial tradition of ship-craft and trade, bronzed Egyptians able to confront the Indians with an antiquity still longer than their own’ (Bevan). The battle of Jhelum was indeed a battle of the nations. Alexander’s army had already become ‘a school for the fusion of races’. Of the numbers in Alexander’s force we have no certain knowledge. Tradition counts 120,000 in his camp, and this number included camp followers, traders and scientific experts, besides the Asiatic wives of the Macedonian soldiers and their children. Tarn estimates the number of fighting men at some 35,000 and adds that the known formations of Alexander render any much greater number impossible. All our authorities agree that his cavalry decidedly outnumbered that of Porus.

Alexander soon saw that it was impracticable to cross the river in the face of so powerful and vigilant a foe, for the very sight of Porus' elephants would have thrown his cavalry into confusion. He had therefore to resort to a ruse and to steal a passage, as Arrian puts it. He sought at first to divert the attention of Porus by dividing his army into several columns with which he made frequent excursions in different directions, as if searching out a spot for easy passage across the river. At the same time he sent out foraging parties into the country and gathered provisions in large quantities, so as to lead the enemy to think that he intended to await a more favourable time when the melting of the snow on the mountains would stop, the river would be low and the crossing easier. The numerous feints of Alexander kept Porus at first perpetually on the move in the nights, and finally he became indifferent to the threats of crossing that never materialised. ‘When Alexander had thus quieted the suspicions of Porus about his nocturnal attempts’, he completed his plans for crossing the river at a point some sixteen miles above his camp. The spot chosen was completely screened from the view of Porus' camp by a remarkable bend in the river, a thickly wooded island in its middle and a bluff on the opposite bank. And Porus' men had become so used to the noises on Alexander's side of the river that the actual preparations for the crossing were carried out with hardly any concealment and without the sentries of Porus suspecting anything unusual; a thunderstorm and a heavy downpour of rain also helped to drown the sound of arms and the shouting of orders.

The actual day chosen for the crossing was advanced by the news that Abhisares of the hill country was, notwithstanding his recent embassy to Takshasila, hastening with his army to the assistance of the Paurava, and it was important to force the encounter before the allies joined their forces.

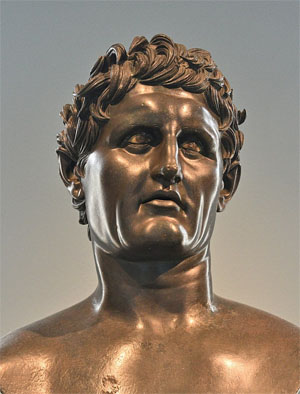

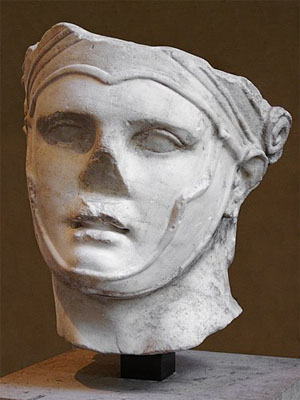

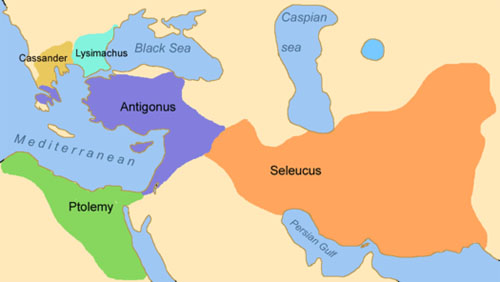

Alexander laid his plans with care and precision. A strong division under Craterus and the troops of Takshasila were left behind in the main camp with orders to remain there as long as they saw the elephants on the opposite bank, but to attempt the passage of the river ‘with all possible speed' whenever they should see the elephants withdrawn. Half way between the main camp and the island were posted the mercenary cavalry and infantry under three commanders, Meleager, Attalus and Gorgias, with instructions to cross to the other side in detachments as soon as they saw the Indians fairly engaged in battle. Alexander took the bulk of the army including the Companions under his own command and marched to the selected spot keeping at a considerable distance from the river bank to avoid detection by the enemy. Towards daybreak the storm subsided and the rain ceased. The army crossed over to the island in boats and skin rafts specially prepared for the cavalry, without being noticed by enemy sentries. Alexander himself crossed over in a thirty-oared galley accompanied by Ptolemy, afterwards king of Egypt, Perdiccas, the future regent, Lysimachus, later king of Thrace, and Seleucus who was to inherit Alexander’s Asiatic empire; there also were the body-guards and one half of the hypaspists. The movements of the troops were concealed by the woody island, until, having passed it, they came within a short distance of the left bank. Then they were perceived by the Indian sentinels who rode off to convey the news to their camp. Meanwhile Alexander, who was the first to disembark, formed the cavalry into line as they came up and moved forward at their head; but he soon discovered that he had not yet reached the mainland, but was still on another island separated from it by a channel, usually shallow, but swollen into a formidable stream on account of the rain. A ford, barely passable, was at length found and the infantry crossed over breast-deep in water and the horses swam across with only their heads above the stream. On this occasion Alexander is said to have exclaimed: ‘O Athenians! Can you believe what dangers I undergo to earn your applause?' Then crossing over, Alexander drew up his forces in order of battle. He posted the body-guards and cavalry on the right wing, and the horse-archers in front of them; next to these were placed the infantry with the archers and javelin-men at each extremity of the phalanx.

Having made these dispositions, Alexander led his 5,000 cavalry forward at a rapid pace; he asked the archers to hasten at the back to give support to the cavalry, while the infantry were to follow at ordinary marching pace in regular order. He decided to avail himself of his superior strength in cavalry, and was confident of defeating the entire army of Porus or keeping it engaged till the infantry came up; if, on the other hand, at the news of his marvellous crossing the enemy took to flight, he would be able to overtake and destroy the fugitives quickly. But the Paurava was no craven. When he received intelligence of the crossing, his first thought was to come up with the enemy, if possible, before he completed the landing; and he immediately sent one of his sons with 2,000 cavalry and 120 chariots to go and contest the passage. But Alexander had made even the final passage before he came up. When he saw the prince advancing, Alexander thought that Porus was approaching with his whole army and sent the horse-archers to reconnoitre. When he discovered the real strength of the advancing force he charged with all his cavalry and overwhelmed it; 400 Indians fell, Porus’ son among them. The chariots were no help on ground loosened by the rain and fell into the hands of the enemy, horses and all. When the survivors went and reported to Porus that Alexander had himself crossed the river with the strongest division of his army, he was perplexed for a while by the necessity of meeting Alexander’s attack and defending the passage of the river against Craterus at the same time. He took a quick decision, and leaving a part of his elephants to check Craterus, he advanced to the decisive conflict with Alexander with the bulk of his troops. Beyond the swampy ground near the river, Porus found a tract of sandy soil on the Karri plain, suited to the movements of his forces, and there he drew up his army for the battle. He relied chiefly on his elephants and he placed them in the front of his line at intervals of a hundred feet; between and behind the elephants were ranged the infantry with huge bows capable of shooting long arrows with great force, though the looseness of the ground due to rain handicapped them badly on this occasion. One half of the cavalry was posted on each flank and the chariots in front of them.

Chapter II: Alexander's Campaigns in India, Excerpt from "Age of the Nandas and Mauryas"

by K.A. Nilakanta Sastri

1952

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Highlights:

We have the name of only one tribal chief, Astes, in the Peucelaotis region (the Yusufzai country) who ventured to offer resistance, and paid for it with his life. His city was captured after thirty days, and in his place was installed Sangaios (Sanjaya ?) who had quarrelled with him some time before and gone over to Taxiles...

The route taken by Alexander along the Khoes is not easy to follow in its details, but doubtless his operations led him for a considerable distance up the large and populous valley of the Kunar, where he fought many hard battles. In an encounter before the first important city taken by the invaders, Alexander was slightly wounded in the shoulder. The city was razed to the ground and all its inhabitants, excepting those who managed to escape to the hills, were put to the sword. Craterus and some other infantry officers were left behind to complete the subjugation of the district, while Alexander advanced to attack the Aspasians, who abandoned their capital on hearing of his approach, and were pursued with great slaughter to their mountain refuges.

Alexander then crossed the mountains to the east and entered the Bajaur valley. Here Craterus rejoined him after carrying out his orders, and was asked to find fresh inhabitants for the city of Arigaion which occupied an advantageous site, but had been burnt down and deserted by its original residents. Meanwhile Ptolemy, the son of Lagos, spotted the main Indian camp ... the Indians descended from the high ground they held to meet the invader on the plain below and sustained a defeat; the number of prisoners taken by the conqueror is said to have been no less than 40,000; then were captured also 230,000 oxen, from which Alexander chose the best to be sent over to Macedonia for use in agriculture...

Alexander appeared before Massaga, ‘the largest city in those parts'. Thus began the war in the upper Swat region against the Assakenoi....the Greek engines of war battered down the defences and inflicted great losses on the besieged, and their chief fell on the fourth day ‘struck by a missile from an engine'. Among the besieged were 7,000 mercenary troop who had no inclination to continue the arduous defence, especially after the death of the ruler of the city, and they started negotiations with Alexander; they were allowed to hill, leave the city, arms in hand, and encamp on a neighbouring on condition that they changed sides and accepted service under Alexander. But they had no wish to aid the foreigner against their countrymen and planned an escape by night to their homes; Alexander heard of this, surrounded their camp and cut them to pieces. Diodorus and Plutarch state that Alexander’s conduct on this occasion was a ‘foul blot on his martial fame’; he had made separate peace with the mercenaries to escape the serious losses they inflicted on his forces, and then fell upon them treacherously. Massaga itself, deprived of its best defenders, was taken by storm, and according to Arrian, the mother and daughter of its ruler became prisoners of war. Curtius records a story that the queen of the city, who had an infant son whom she placed on Alexander’s knees was treated indulgently by the conqueror, rather owing ‘to the charms of her person than to pity for her misfortunes'. He adds that afterwards she gave birth to a child who received the name of Alexander. Justin mentions that the Indians called the queen ‘the royal harlot'....

Bazira, which stood on a lofty eminence and was strongly fortified, offered resistance to Koinos... Alexander directed his march to that city first, and ordered Koinos to join him there after fortifying a position before Bazira and leaving there a garrison strong enough 'to keep the inhabitants from undisturbed access to their lands’. A sortie by the defenders of Bazira after the departure of Koinos was unsuccessful and they were confined more rigorously than before within the walls their city. Ora was captured at the first assault with little loss to the invader, who took over all the elephants he found there. The news of the fall of Ora led the inhabitants of Bazira to abandon their city at dead of night and seek refuge in the more inaccessible heights of the neighbouring mountains....

Alexander then spent some days reducing minor strongholds, some on the way to the Indus, and some on its right bank, accompanied by two local chieftains Kophaios and Assagetes (Asvajit ?)....

Before crossing the Indus, Alexander had still to deal with the last stronghold of the Assakenoi at Aornos to which they had all flocked for refuge...

Seeing the extraordinary skill with which these daring operations were carried out and the success which attended them, the Indians began to feel that further resistance was hopeless and sent a messenger to Alexander offering to surrender the rock if he granted them terms of capitulation. While the negotiations were dragging on, the besieged formed plans of dispersing to their several homes under cover of night; Alexander saw this, allowed them to begin their retreat without any obstruction, and then with a picked body of seven hundred troops scaled the rock at the point abandoned by the defenders. The surprise was complete; many of the Indians were slaughtered, and many others fell over the precipices and were dashed to death; ‘Alexander thus became master of the rock which had baffled Herakles himself....

From Aornos, records Arrian, Alexander went in pursuit of the fleeing defenders of Aornos, who were led by a brother of the Assakenian chief killed in Massaga. The fugitives had taken refuge in the mountains with an army and some elephants. When Alexander reached Dyrta he found the city and its environs deserted, and thereupon he detached certain troops to reconnoitre the surrounding country and secure information about the enemy, particularly his elephants....From captives Alexander learned that the Indian prince had crossed the Indus and taken refuge with Abhisares, leaving his elephants at pasture near the Indus. These he succeeded in capturing with a loss of only two animals killed in the chase by their falling down a precipice....

Only Porus (Paurava), bearer of a great name coming down from the age of the Rigveda, sent a defiant reply to Alexander’s message and said he would meet the invader at the frontier of his territory, but in arms....

When he saw the prince advancing, Alexander thought that Porus was approaching with his whole army and sent the horse-archers to reconnoitre. When he discovered the real strength of the advancing force he charged with all his cavalry and overwhelmed it; 400 Indians fell, Porus’ son among them. The chariots were no help on ground loosened by the rain and fell into the hands of the enemy, horses and all...

The engagement now became crowded into a narrow space, and the elephants being pressed from all sides became uncontrollable; many of them lost their drivers, and maddened by wounds, they turned their fury against friend and foe quite indiscriminately. The Macedonians who retained a wide and open field on the whole suffered less from the elephants as they eluded their attack by giving way when they charged, and followed them and plied them with darts when they retreated. At length many of the elephants were killed and the rest spent with wounds and toil, ceased to be formidable. Then Alexander ordered a general charge of horse and foot and the battle ended in a decisive victory for him. By this time the Macedonian divisions on the right bank had crossed over, and being fresh, were employed in the pursuit of the retreating Indians on whom they inflicted great slaughter...

When Alexander took the field again with a select division of horse and foot, he invaded the land of the Glausai or Glauganikai (Glauchukayanas) as they were called, a free tribe on the western bank of the Akesines (Chenab) living in thirty-seven cities of between five and ten thousand inhabitants each and a multitude of villages. These people were now placed under the rule of the Paurava against whom they had maintained their independence for so long...

Alexander crossed the Ravi and entered the land of the Kathaians (Kathas), who were among the best fighters in the Punjab and had gathered their allies for the defence of their fortified capital, Sangala (not yet identified). These warlike Kshatriya tribes had proved their mettle a short time before against Porus and Abhisares when they marched against them; would they prevail against the new-comer from farther west? Within two days of his crossing the Ravi, Alexander had received the submission of Pimprama (unidentified), the city of the Adraistai (Adhrshtas or, according to Jayaswal, Arishtas), But the Kathaians of Sangala camped under shelter of a low hill outside the city and offered a determined resistance from behind a triple barricade of wagons. Finding his cavalry of no avail against the enemy, Alexander led the infantry on foot and after much hard fighting, compelled the Indians to seek refuge behind the city walls. Alexander now closely invested the city, and Porus joined him with a force, of 5,000 Indians and several elephants; the besieged made a plan of escape by night across a shallow lake on one side of the city, but it was betrayed to Alexander, who fell upon the fugitives and forced them back into the city, after inflicting losses on them. Military engines then began to batter the walls, but before a breach was effected, the Macedonians carried the walls by escalade. The city was taken, many of the Kathaians were killed, and more taken prisoner. The desperate nature of the fighting is clear; the Greek accounts admit an unusually large number of slain and wounded in Alexander’s army; and Alexander razed the city to the ground. The inhabitants of two neighbouring cities, the allies of the Kathaians, escaped a similar fate by abandoning their cities in good time.

The Malloi (Malavas) and the Oxydrakoi (Kshudrakas) were getting ready to give a hostile reception to the invader, and Alexander wanted to press on quickly and attack them before they completed their dispositions...

Alexander himself landed with a body of picked troops and made an inroad against the Siboi (Sibis) and the Agalassoi (Agrasrenis) to prevent their joining the powerful confederacy of the Malloi lower down the river. The Sibis, a wild people clad in skins and armed with clubs, who claimed descent from the soldiers of Hercules, made their submission when Alexander encamped near their capital. Their neighbours, the Agalassoi, were not so amenable; they had mustered an army of 40,000 foot and 3,000 horse and offered battle. They fought in the field and in the streets of their city, and many Macedonian soldiers fell; this roused the fury of Alexander, who set fire to the city and massacred large numbers of the inhabitants, condemning many others to slavery; a bare 3,000 sued for mercy and were spared....

Alexander planned a great drive against the tribal confederations of the Malavas, and their allies, the Kshudrakas who lived farther to the East along the Beas. While he himself with his favourite troops would deliver the main attack, Hephaestion, who had gone in advance, and Ptolemy, who was to follow behind, would prevent the enemy's attempts to escape in either direction....

Alexander struck across fifty miles of waterless desert and completely surprised the first city of the Malavas he came against; the men, who were abroad in the fields unarmed, offered no resistance and were simply butchered; the rest were shut up in the city, guarded by a cordon of cavalry round the walls till the infantry came up. Then Perdiccas was sent forward to the next city, which he was to invest without attempting to storm the place till Alexander came up. The first city was now carried by assault, the citadel in the centre of it holding out somewhat longer; practically all the garrison were killed. Meanwhile Perdiccas reached the city against which he had been sent, and found it deserted; he rode in hot pursuit of the fugitives and overtook and killed some, but the bulk of them managed to escape him to the marshes of the river and beyond.

Soon Alexander came up and joined the pursuit; many of the Malavas were overtaken and slain while crossing the Ravi, but others, made good their escape to a position of great natural strength which was also strongly fortified; here they were attacked by Peithon, who carried the fortress by assault and made slaves of all who had fled to it for refuge. The next place to be attacked was a city of the Brahmins to which the Malavas had flocked; here the resistance was desperate and most of the five thousand defenders sold their lives dear, only a few being taken prisoners. After a day’s rest for the army, Alexander resumed the pursuit and, when he found the cities empty, he had the jungles scoured for fugitives, and his soldiers had instructions to kill everyone that was caught, unless he surrendered voluntarily....The Malavas now withdrew into the nearest stronghold, being hotly pursued by the enemy. In the assaults that followed the next day, the main walls of the city were yielded with little resistance; the citadel held out, and in the assault on it Alexander exposed himself in a way that nearly cost him his life; scaling ladders were few, and Alexander got up one of them, being the first to appear on the wall, a conspicuous target because of his shining arms; to escape the danger, he jumped within the citadel and only a few of his companions could join him there at once; they maintained an unequal contest for some time, but the arrows of the Malavas killed some of them, and Alexander himself was deeply wounded in the chest, and fainted with loss of blood when the arrowhead was pulled out by Perdiccas. Possibly Alexander adopted the desperate expedient to keep up the morale of his troops in this difficult war. The danger to their king maddened the Greek troops and when they managed to gain the citadel by scrambling up the earthen walls and breaking In the gates, they did not spare man, woman or child....

What was left of the Malava people after the decimation of the war sent in their submission now, and the Kshudrakas, who had been holding aloof so long as the swiftness of Alexander’s movements left them no chance of going to aid the Malavas, also sent their representatives with full authority to conclude a treaty with the invader....But the campaign against the Malavas was no unalloyed success. As a record of mere slaughter it stands out unique even in the blood-stained annals of Alexander’s Indian campaigns...

The progress of the flotilla down the Chenab and the Indus cannot be traced...More ships were built, and more tribes submitted along the course, the Abastanoi, (Ambashthas), Xathaoi (Kshaitiyas) and Ossadioi (Vasatis)....

The country below the last confluence differed from the Punjab in its political and social conditions, which have been noted with surprise by the Greek writers. There were no free tribes here, but principalities ruled by kings whose Brahmin counsellors had great influence with them and the people....

The greatest king of this region was known to the Greeks by the name Musicanus (Muchukarna ?). He did not offer his submission or even send presents, but when surprised by the sudden arrival of Alexander in his country, he adopted the course of prudence, tendered his submission and was confirmed in his territory though a garrison was installed in the citadel of his capital (Alor?), which Craterus was to fortify adequately. Alexander then took a number of cities with much booty, all from a chieftain named Oxycanus who was made prisoner. Sambus had abandoned his capital Sindimana when he heard that Alexander had made friends with his arch-enemy Musicanus; his relatives explained the situation to Alexander and offered presents, which were accepted. But the most irreconcilable enemies of the foreigners in this region were the Brahmins (Brahmanako nama Janapadah-Patanjali) and one of their cities was carried by storm and all its inhabitants put to death. Meanwhile Musicanus, acting probably on the advice of his ministers, threw off his allegiance; Peithon who was sent against him suppressed the revolt with a strong hand. He destroyed some cities and placed garrisons in others; he took Musicanus captive and produced him before Alexander, who ordered that he should be executed along with his instigators.

Then came the ruler of Patala and the delta country and offered his submission...With the rest of the army Alexander continued his course downstream and reached Patala in the middle of July 325 B. C.; when he found the city deserted, he sent his emissaries to overtake the fugitives and persuade them to return in safety to their lands and cultivate them as formerly, and so most of the people did return to their homes....

Alexander set out with some ships to explore the western arm of the river; the task was rendered difficult by lack of knowledgeable pilots, the whole country having been deserted by its inhabitants....

When he reached the Arabios (Hab) he found the country deserted, as the Arabitai tribesmen had fled in terror. Crossing the river, he entered Las Bela, the land of the Oreitai, who offered a slight and ineffectual opposition to his progress. One of their villages, Rambakia, pleased Alexander by its situation and Hephaestion was instructed to colonise it with Arachosians (Curtius). When he passed on to the country of the Gedrosi, he appointed Apollophanes satrap over the Oreitai and leit Lenonnatus to reduce the country and help in the scheme of colonisation. Leonnatus fought a pitched battle with the tribesmen, inflicting great losses on them, and the satrap designate, Apollophanes, was among those who fell on his side.

-- Chapter II: Alexander's Campaigns in India, Excerpt from "Age of the Nandas and Mauryas", by K.A. Nilakanta Sastri

CHAPTER II: ALEXANDER'S CAMPAIGNS IN INDIA

After Alexander’s conquest of Bactria and Sogdiana, the Indian satrapy was the only province of the Persian empire into which he had not carried his arms. Of this province he must have gained some valuable knowledge from Sisikottos (Sasigupta), the Indian mercenary leader who transferred his services from Bactria to her conqueror. Alexander also received an embassy in Sogdiana from Omphis (Ambhi) of Takshasila (Taxila) which offered him the alliance of the Indian prince and sought the foreigner’s aid against his powerful neighbour Porus, the first recorded instance of an Indian seeking foreign aid against fellow Indians.

At the end of the spring of 327 B.C., Alexander started on his Indian expedition leaving Amyntas behind with 3,500 horse and 10,000 foot to hold the land of the Bactrians. He crossed the Central Hindu Kush in ten days following the main road from Balkh to Kabul, and reached the rich and beautiful valley of Koh-i-Daman, where he had already founded an Alexandria, which he now strengthened with fresh recruits from the neighbourhood and from among his war-worn soldiers. He placed Nicanor in charge of the city, and appointed Tyriespes satrap of the area, dispositions intended, as was, usual with Alexander, to secure his rear before advancing further.

Alexander then proceeded to Nikaia (Greek for ‘city of victory’), a place that lay most likely on his route to the river Kabul. Here he offered a sacrifice to the goddess Athena, and met an Indian embassy headed by the king of Takshasila which ‘brought him such presents as are most esteemed by the Indians’ and gave him also all the elephants they had with them, twenty-five in number.

After leaving Nikaia and at some distance from the city on the way to the Kabul river, Alexander divided his army, and sent one part of it under Hephaestion and Perdiccas to the Indus, along the course of the Kabul river, with instructions to take Peucclaotis (Pushkalavatl, near Gharsadda, N.E. of Peshawar) and other places on the way by force if they would not submit of their own accord. When they reached the Indus they were to make necessary preparations for the transport of the army across that river. We have the name of only one tribal chief, Astes, in the Peucelaotis region (the Yusufzai country) who ventured to offer resistance, and paid for it with his life. His city was captured after thirty days, and in his place was installed Sangaios (Sanjaya ?) who had quarrelled with him some time before and gone over to Taxiles. The boats built by the Greeks on reaching the Indus were such as could be taken to pieces and reassembled on reaching another river (Curtius).

Subjugation of the Swat Valley

With the rest of the army Alexander set forth on a hard campaign in the mountains in order to secure the flank of his main line of communication. The people of these mountain tracts are called Aspasians, Gauraians and Assakenians by Arrian. The first and last of these terms are variants of the same tribal name, Asmaka, a name known to Varahamihira’s list of tribes in North-Western India; the other rendering of the name into Asvaka is supported by the fact that the Greeks translated it into Hippasioi (Hypasioi in Strabo). It is noteworthy that the Pushto name for the Yuzufzai still continues to be Asip or Isap. The Gauraians were doubtless closely connected with them and took their name from the river Gauri (Panjkora), the Gouraios of the Greek texts. They were all obviously Indian tribes and are so described by the Greek writers.

The route taken by Alexander along the Khoes is not easy to follow in its details, but doubtless his operations led him for a considerable distance up the large and populous valley of the Kunar, where he fought many hard battles. In an encounter before the first important city taken by the invaders, Alexander was slightly wounded in the shoulder. The city was razed to the ground and all its inhabitants, excepting those who managed to escape to the hills, were put to the sword. Craterus and some other infantry officers were left behind to complete the subjugation of the district, while Alexander advanced to attack the Aspasians, who abandoned their capital on hearing of his approach, and were pursued with great slaughter to their mountain refuges.

Alexander then crossed the mountains to the east and entered the Bajaur valley. Here Craterus rejoined him after carrying out his orders, and was asked to find fresh inhabitants for the city of Arigaion which occupied an advantageous site, but had been burnt down and deserted by its original residents. Meanwhile Ptolemy, the son of Lagos, spotted the main Indian camp and brought news of its whereabouts to Alexander, who planned an attack against it in three divisions, one of which he led ‘in person against the position occupied by the main body’ of the Indian forces. Confident in the strength of their numbers, the Indians descended from the high ground they held to meet the invader on the plain below and sustained a defeat; the number of prisoners taken by the conqueror is said to have been no less than 40,000; then were captured also 230,000 oxen, from which Alexander chose the best to be sent over to Macedonia for use in agriculture. After the subjugation of the Aspasians, Alexander moved, according to Curtius, to the city of Nysa; Arrian records the visit in detail, but gives no indication of the position of Nysa, and is openly sceptical not only of the legendary details, but of the existence of the city itself. The inhabitants of Nysa offered no resistance, but sent an embassy with presents and claimed kinship with the Greeks on the score that their city had been founded by Dionysus and named after his nurse, Nysa, and that the Nysans were the descendants of his followers; the mountain near the city also bore the name Meros (thigh) because Dionysus grew, before his birth, in the thigh of Zeus. Nysa had remained a free city with its own laws ever since, and Alexander should permit them to continue as they were. ‘It gratified Alexander to hear all this' from Akuphis, the leader of the Nysan deputation, and he was not inclined to be too critical of legends that were pleasing to the ears of his soldiers, and promised him the glory of excelling the achievements of Dionysus. So he offered a sacrifice to his divine predecessor and confirmed his colony in the enjoyment of its ancient laws and liberty as an aristocratic republic. When Alexander asked for three hundred horsemen from Nysa and one hundred of their best men to accompany him, Akuphis smiled and agreed readily to give the horsemen, but offered two hundred of the worst men of Nysa instead of the hundred best demanded by Alexander. The reply by no means displeased Alexander who took the cavalry and waived the other demand. He made a pilgrimage to Mount Meros (Koh-i-Mor ?) where his followers rejoiced at the sight of the ivy and laurel and wove chaplets of them for their heads while they joyfully chanted hymns to the divine forerunner of Alexander.

Marching across the land of the Gauraians and crossing the river Gauri (Panjkora), a difficult task owing to the depth and swiftness of the stream, Alexander appeared before Massaga, ‘the largest city in those parts'. Thus began the war in the upper Swat region against the Assakenoi. This powerful confederation commanded extensive territory including the whole of Swat, Buner and the valleys to the north of Buner, and extending right up to the Indus. It had an army of 20,000 cavalry'1 [Lassen and Stein give 2,000.], and more than 30,000 infantry besides 30 elephants. Yet, it seems to have relied for defence against the invader not on fighting in open battle, but on the fortifications of its walled towns. The Greek accounts of the war contain details of several places besieged and taken by Alexander, but their position can seldom be fixed with confidence on modern maps. Stein, who knew the country very well, suggests that they ‘were probably situated in the main Swat valley; for this at all times must, as now, have been the most fertile and populous portion of the territory'.

The siege of Massaga (Masakavati ?) the capital of the Assakenoi, lasted for four days; at the outset Alexander was wounded in the leg, 'though not severely', by an arrow from the besieged; but the Greek engines of war battered down the defences and inflicted great losses on the besieged, and their chief fell on the fourth day ‘struck by a missile from an engine'. Among the besieged were 7,000 mercenary troop who had no inclination to continue the arduous defence, especially after the death of the ruler of the city, and they started negotiations with Alexander; they were allowed to hill, leave the city, arms in hand, and encamp on a neighbouring on condition that they changed sides and accepted service under Alexander. But they had no wish to aid the foreigner against their countrymen and planned an escape by night to their homes; Alexander heard of this, surrounded their camp and cut them to pieces. Diodorus and Plutarch state that Alexander’s conduct on this occasion was a ‘foul blot on his martial fame’; he had made separate peace with the mercenaries to escape the serious losses they inflicted on his forces, and then fell upon them treacherously. Massaga itself, deprived of its best defenders, was taken by storm, and according to Arrian, the mother and daughter of its ruler became prisoners of war. Curtius records a story that the queen of the city, who had an infant son whom she placed on Alexander’s knees was treated indulgently by the conqueror, rather owing ‘to the charms of her person than to pity for her misfortunes'. He adds that afterwards she gave birth to a child who received the name of Alexander. Justin mentions that the Indians called the queen ‘the royal harlot'.

The final stages of the campaign in the Swat valley centred round Bazira (Bir-kot) and Ora (Udegram). Koinos was sent to Bazira, which was expected to surrender, and three other generals against Ora, with instructions to invest the place until the arrival of Alexander. Bazira, which stood on a lofty eminence and was strongly fortified, offered resistance to Koinos, and on hearing this, Alexander started to conduct the operations there himself. But then he learned of attempts to reinforce Ora, set on foot by Abhisares, the king of Abhisara, territory east of the Indus. Alexander directed his march to that city first, and ordered Koinos to join him there after fortifying a position before Bazira and leaving there a garrison strong enough 'to keep the inhabitants from undisturbed access to their lands’. A sortie by the defenders of Bazira after the departure of Koinos was unsuccessful and they were confined more rigorously than before within the walls their city. Ora was captured at the first assault with little loss to the invader, who took over all the elephants he found there. The news of the fall of Ora led the inhabitants of Bazira to abandon their city at dead of night and seek refuge in the more inaccessible heights of the neighbouring mountains. This was the end of the campaign in the Swat valley; Alexander turned Ora and Massaga into strongholds for guarding the country round about, and improved the defences of Bazira, before marching south towards the Peshawar valley to follow the line taken by Hephaestion and Perdiccas down the Kabul river.

These generals had fortified a town called Orobatis (not identified) on their way to the Indus Alexander now appointed Nicanor satrap of the country west of the Indus, and received the submission of Peucelaotis (Pushkalavati), the ancient capital of Gandhara, stationing a garrison of Macedonian soldiers in the city under the command of Philip. Alexander then spent some days reducing minor strongholds, some on the way to the Indus, and some on its right bank, accompanied by two local chieftains Kophaios and Assagetes (Asvajit ?).

Aornos

Before crossing the Indus, Alexander had still to deal with the last stronghold of the Assakenoi at Aornos to which they had all flocked for refuge. This place has been most satisfactorily located by Stein in the mountain ranges of Pir-sar and Una-sar, which answer to all the topographical details contained in the Greek accounts of Alexander’s operations against Aornos, accounts derived ultimately from Ptolemy, the son of Lagos, who took a prominent part in those operations.

A word may be said at this stage about political conditions in the North-West frontier of India at the time of Alexander’s invasion; the Assakenoi and their neighbouring and allied tribes were supported by Abhisares, and probably also by Porus, in their resistance to the invader; Abhisara proper is the name of the hill country between the upper Jhelum and the Chenab; but the ruler of this territory at this time seems to have extended his sway in the west into Hazara (Ursa) up to the Indus, and on the east his territory might well have included parts of Kashmir. The ruler of Takshailla whose territory lay between the kingdoms of Abhisares and Porus, was on no friendly terms with them, and, as we have already seen, he welcomed the invader, hoping to have his support against his local enemies. It is not surprising then that the Assakenoi prepared themselves to defend their independence in a region impregnable because of its physical features and in close proximity to the territory of Abhisares, and that Alexander did not feel free to accept the welcome of Taxila until he had overthrown this last and most redoubtable stronghold of the tribes whose subjugation was the chief aim of the arduous campaigns he had fought in the Swat valley.

To get at this stronghold on the eastern frontier of the Assakenian country, Alexander had to move some way up the right bank of the Indus to Embolima (Amb), a city within two marches of Aornos. Here he left Craterus with a part of the army to gather into the city as much corn as possible and all other requisites for a prolonged stay, in order that the Macedonians, having that place as a base, might by protracted investment wear out those holding the rock, in case it should not be taken at the first assault. Alexander himself then advanced to the rock, taking with him the archers, the Agrianians, the brigade of Koines, the lightest and best armed of the phalanx, two hundred of the companion cavalry and one hundred horse-archers. He fixed his camp on the second day very near the rock.

Aornos is described by Arrian as a mighty mass of rock, 6,600 ft. in height with a circuit of about 22 miles; Diodorus halves the circuit, puts the height at 9,600 ft., and says that it was washed by the Indus on its southern side. 'It was ascended', says Arrian, ‘by a single path cut by the hand of man, yet difficult. On the summit of the rock there was, it is also said, plenty of pure water which gushed out from a copious spring. There was timber besides, and as much good arable land as required for its cultivation the labour of a thousand men'. A report was current that this stronghold was once assaulted in vain by Hercules who had to abandon the attempt on the occurrence of a ‘violent earthquake and signs from heaven', and this is said to have made Alexander the more eager for the capture of the stronghold. But it should be noted that Arrian discredits the story and says ‘my own conviction is that Herakles was mentioned to make the story of its capture all the more wonderful'.

At first Alexander was at a loss how to proceed to the attack, when some people from the neighbourhood came to him, offered their submission and undertook to guide him to the most accessible portion of the rock, from which the assault on the main eminence would not be difficult. Alexander accepted their guidance and sent with them Ptolemy with a select body of light-armed troops, telling him that on securing the position he was to signal to him and to hold it with a strong force. Traversing a rough and difficult route which led most probably up the valley to the west of the Danda-Nurdai spur, Ptolemy succeeded in occupying the indicated position on the height known as Little Una, unobserved by the defending forces on the heights of Pir-Sar. He fortified his position with a palisade and a trench, and signified his success to Alexander by means of a beacon raised on a height from which it would be seen by Alexander. Alexander did see it, and he moved forward the next day with his army along the route that Ptolemy had taken; but the defenders soon saw what had happened and sent their men to the heights of Danda-Nurdai to obstruct the ascent of Alexander, which they did successfully, and then turned round and attacked the position held by Ptolemy higher up; after severe fighting in the latter part of the day, the Indians failed to carry Ptolemy’s fortifications and retired at nightfall.

During the night, Alexander secured the aid of an Indian deserter and sent a letter to Ptolemy asking him not to be content on the following day with just holding his position but to attack the Indians in the rear when they sought to obstruct the passage of the main army up the hill. At daybreak he started again, and succeeded, after a hard fight in forcing a passage and effecting a junction with Ptolemy’s men. But the assault on the main rock (Pir-Sar) could not be undertaken without much toil in filling up a ravine that lay between his position and the height held, by the defenders. This task was begun the next day and Alexander himself supervised the operations of cutting stakes and piling up a mound towards the main rock. The mound was advanced to a length of 200 yards as a result of the first day’s work, but progress became necessarily slower in the depths of the ravine. The Indians attempted to obstruct the progress of the work and, though by their sallies they inflicted some losses on the enemy, their main object was foiled by the missiles of the Greeks shot from engines which were being advanced along the mound as each section of it was completed. The work of piling up the mound went on for three days without intermission, and on the fourth a few Macedonians succeeded in forcing their way up a small hill and occupying its crest on a level with the rock. The work on the extension of the mound was continued until it was joined three days later to the small hill near the rock that had passed into Greek occupation. Seeing the extraordinary skill with which these daring operations were carried out and the success which attended them, the Indians began to feel that further resistance was hopeless and sent a messenger to Alexander offering to surrender the rock if he granted them terms of capitulation. While the negotiations were dragging on, the besieged formed plans of dispersing to their several homes under cover of night; Alexander saw this, allowed them to begin their retreat without any obstruction, and then with a picked body of seven hundred troops scaled the rock at the point abandoned by the defenders. The surprise was complete; many of the Indians were slaughtered, and many others fell over the precipices and were dashed to death; ‘Alexander thus became master of the rock which had baffled Herakles himself. He celebrated his success by offering sacrifice and worship to the gods and erected altars dedicated to Minerva and Victory. He also built a fort and gave command of it to Sisikottos before setting out to complete the conquest of the Assakenoi and rejoin his main forces on the banks of the Indus. The siege and capture of Aornos may be placed round about the month of April 326 B. C.

From Aornos, records Arrian, Alexander went in pursuit of the fleeing defenders of Aornos, who were led by a brother of the Assakenian chief killed in Massaga. The fugitives had taken refuge in the mountains with an army and some elephants. When Alexander reached Dyrta he found the city and its environs deserted, and thereupon he detached certain troops to reconnoitre the surrounding country and secure information about the enemy, particularly his elephants. Dyrta has not been identified, but the fact that a new road had to be made, without which the march across the country to the Indus would have been impracticable, seems to point to the central parts of Buner as the scene of the operations. From captives Alexander learned that the Indian prince had crossed the Indus and taken refuge with Abhisares, leaving his elephants at pasture near the Indus. These he succeeded in capturing with a loss of only two animals killed in the chase by their falling down a precipice. He also discovered a lot of serviceable timber, which he caused to be floated down the Indus to the bridge constructed long before this by the other section of the army.

When Alexander reached the bridge at Ohind, at the end of sixteen marches, he gave his army a rest of thirty days, entertaining them with games and contests. Here he was met by an embassy from Ambhi of Takshasila who had recently succeeded to his father’s throne, but was awaiting the arrival of Alexander to assume sovereignty. The embassy brought presents consisting of 200 talents of silver, 3,000 fat oxen, 10,000 sheep or more and 30 elephants; a force of 700 horsemen also came to the assistance of Alexander from the same prince and brought word that Ambhi surrendered into Alexander’s hands his capital Takshasila, ‘the greatest of all the cities between the river Indus and Kydaspes’. Alexander then offered sacrifice to the gods on a magnificent scale and found the signs favourable for his crossing into India proper the first European to set his foot on Indian soil.

Taxila

As the invader approached Takshasila a strange incident occurred. When he was at a distance of some four miles from the city, he was met by a whole army drawn in battle order and elephants ranged in a line; Alexander suspected treachery and instructed his troops to prepare for a battle; but Ambhi seeing the mistake made by the Macedonians, left his army with a few friends and contrived to explain to Alexander, with the aid of an interpreter, that he meant not to fight, but to honour his foreign ally whose protection he had been soliciting for so long and with so much persistence. He surrendered himself, his army and kingdom into the hands of Alexander, and got them back as his favoured protege.

Alexander was entertained in Takshasila for three days with lavish hospitality, and on the fourth day he and his friends received presents of golden crowns and eighty talents of coined silver (Curtius). In his turn Alexander showed his gratification by sending to Ambhi a thousand talents from his spoils of war ‘along with many banqueting vessels of gold and silver, a vast quantity of Persian drapery, and thirty chargers from his own stalls, caparisoned as when ridden by himself'. Thus did a fraction of the loot from the store-houses of the old Persian kings find its lodgement in the palace of Takshasila. But Alexander’s liberality on the occasion displeased some of the Macedonian generals, though it secured for him an additional force of five thousand men and the unfailing loyalty of a most useful ally. Embassies from Indian princes met Alexander here with presents and declared their submission to him; even Abhisares of the hill country sent his brother. Only Porus (Paurava), bearer of a great name coming down from the age of the Rigveda, sent a defiant reply to Alexander’s message and said he would meet the invader at the frontier of his territory, but in arms. Porus was the ruler of a considerable kingdom, and its expansion was doubtless causing some stir among the neighbouring kings and tribes, and bringing about the political alliances and groupings among them at the time.

Preparing to leave Takshasila for the encounter with Porus, Alexander offered the customary sacrifices and celebrated a gymnastic and equestrian contest. He sent Koinos back to the Indus to dismantle the bridge of boats and bring it over to the Jhelum river, the ancient (Vitasta, the Hydaspes of the Greeks). He posted Philip, the son of Machatus, at the head of a garrison, as satrap of Takshasila and its neighbourhood, and began his march to the Jhelum with his own army and the Taxilan contingent of 5,000 men commanded by their king in person. The route lay in a south-easterly direction over difficult country and was about a hundred miles in length. On his march Alexander found a defile on his road occupied by Spitaces, a nephew of Porus, with a body of troops; these he soon dispersed, and then completed his march without encountering any further opposition; Spitaces fought later on the side of his uncle and fell in the battle of the Jhelum.

Battle of the Jhelum