Chapter 4: The Song of the Moth

The double role of Faust: creator and destroyer -- "I came not to send peace, but a sword" -- The modern problem of choice between Scylla of world-renunciation and Charybdis of world-acceptance --The ethical pose of The Hymn of Creation having failed, the unconscious projects a new attempt in the Moth-Song -- The choice, as in Faust -- The longing for the sun (or God) the same as that for the ship's officer -- Not the object, however: the longing is important -- God is our own longing to which we pay divine honors -- The failure to replace by a real compensation the libido-object which is surrendered, produces regression to an earlier and discarded object -- A return to the infantile -- The use of the parent image -- It becomes synonymous with God, Sun, Fire -- Sun and snake -- Symbols of the libido gathered into the sun-symbol -- The tendency toward unity and toward multiplicity -- One God with many attributes: or many gods that are attributes of one -- Phallus and sun -- The sun-hero, the well-beloved -- Christ as sun-god -- "Moth and sun" then brings us to historic depths of the soul -- The sun-hero creative and destructive -- Hence: Moth and Flame: burning one's wings -- The destructiveness of being fruitful -- Wherefore the neurotic withdraws from the conflict, committing a sort of self-murder -- Comparison with Byron's Heaven and Earth.

A LITTLE later Miss Miller travelled from Geneva to Paris. She says:

"My weariness on the railway was so great that I could hardly sleep an hour. It was terrifically hot in the ladies' carriage."

At four o'clock in the morning she noticed a moth that flew against the light in her compartment. She then tried to go to sleep again. Suddenly the following poem took possession of her mind.

The Moth to the Sun

"I longed for thee when first I crawled to consciousness.

My dreams were all of thee when in the chrysalis I lay.

Oft myriads of my kind beat out their lives

Against some feeble spark once caught from thee.

And one hour more -- and my poor life is gone;

Yet my last effort, as my first desire, shall be

But to approach thy glory; then, having gained

One raptured glance, I'll die content.

For I, the source of beauty, warmth and life

Have in his perfect splendor once beheld."

Before we go into the material which Miss Miller offers us for the understanding of the poem, we will again cast a glance over the psychologic situation in which the poem originated. Some months or weeks appear to have elapsed since the last direct manifestation of the unconscious that Miss Miller reported to us; about this period we have had no information. We learn nothing about the moods and phantasies of this time. If one might draw a conclusion from this silence it would be presumably that in the time which elapsed between the two poems, really nothing of importance had happened, and that, therefore, this poem is again but a voiced fragment of the unconscious working of the complex stretching out over months and years. It is highly probable that it is concerned with the same complex as before. [1] The earlier product, a hymn of creation full of hope, has, however, but little similarity to the present poem. The poem lying before us has a truly hopeless, melancholy character; moth and sun, two things which never meet. One must in fairness ask, is a moth really expected to rise to the sun? We know indeed the proverbial saying about the moth that flew into the light and singed its wings, but not the legend of the moth that strove towards the sun. Plainly, here, two things are connected in her thoughts that do not belong together; first, the moth which fluttered around the light so long that it burnt itself; and then, the idea of a small ephemeral being, something like the day fly, which, in lamentable contrast to the eternity of the stars, longs for an imperishable daylight. This idea reminds one of Faust:

"Mark how, beneath the evening sunlight's glow

The green-embosomed houses glitter;

The glow retreats, done is the day of toil,

It yonder hastes, new fields of life exploring;

Ah, that no wing can lift me from the soil

Upon its track to follow, follow soaring!

Then would I see eternal Evening gild

The silent world beneath me glowing. . . .

Yet, finally, the weary god is sinking;

The new-born impulse fires my mind, --

I hasten on, his beams eternal drinking,

The day before me and the night behind,

Above me heaven unfurled, the floor of waves beneath me, --

A glorious dream! though now the glories fade.

Alas! the wings that lift the mind to aid

Of wings to lift the body can bequeath me."

Not long afterwards, Faust sees "the black dog roving there through cornfields and stubble," the dog who is the same as the devil, the tempter, in whose hellish fires Faust has singed his wings. When he believed that he was expressing his great longing for the beauty of the sun and the earth, "he went astray thereover" and fell into the hands of "the Evil One."

"Yes, resolute to reach some brighter distance,

On earth's fair sun I turn my back."

This is what Faust had said shortly before, in true recognition of the state of affairs. The honoring of the beauty of nature led the Christian of the Middle Ages to pagan thoughts which lay in an antagonistic relation to his conscious religion, just as once Mithracism was in threatening competition with Christianity, for Satan often disguises himself as an angel of light. [2] The longing of Faust became his ruin. The longing for the Beyond had brought as a consequence a loathing for life, and he stood on the brink of self-destruction. [3] The longing for the beauty of this world led him anew to ruin, into doubt and pain, even to Marguerite's tragic death. His mistake was that he followed after both worlds with no check to the driving force of his libido, like a man of violent passion. Faust portrays once more the folk-psychologic conflict of the beginning of the Christian era, but what is noteworthy, in a reversed order.

Libido: In my view, this concept is synonymous with psychic energy. Psychic energy is the intensity of the psychic process -- its psychological value. By this I do not mean to imply any imparted value, whether moral, aesthetic, or intellectual; the psychological value is simply conditioned by its determining power, which is manifested in definite psychic operations ('effects'). Neither do I understand libido as a psychic force, a misunderstanding that has led many critics astray. I do not hypostasize [assume the reality of] the concept of energy, but employ it as a concept denoting intensity or value. The question as to whether or no a specific psychic force exists has nothing to do with the concept of libido. Frequently I employ the expression libido promiscuously with 'energy'.

-- Psychological Types, by C.G. Jung

Against what fearful powers of seduction Christ had to defend himself by means of his hope of the absolute world beyond, may be seen in the example of Alypius in Augustine. If any of us had been living in that period of antiquity, he would have seen clearly that that culture must inevitably collapse because humanity revolted against it. It is well known that even before the spread of Christianity a remarkable expectation of redemption had taken possession of mankind. The following eclogue of Virgil might well be a result of this mood:

"Ultima Cumasi venit jam carminis aetas; [i]

Magnus ab integro Saeclorum nascitur ordo,

Jam redit et Virgo, [4] redeunt Saturnia regna;

Jam nova progenies caelo demittitur alto.

Tu modo nascenti puero, quo ferrea primum

Desinet ac toto surget gens aurea mundo,

Casta fave Lucina: tuus jam regnat Apollo.

"Te duce, si qua manent sceleris vestigia nostri,

Inrita perpetua solvent formidine terras.

Ille deum vitam accipiet divisque videbit

Permixtos heroas et ipse videbitur illis,

Pacatumque reget patriis virtutibus orbem." [5]

[Google translate: "At last came the age of the song Cumasi;

Great is the order of the generations arises afresh,

Now returns the Maid, returns the reign of Saturn;

Now a new generation sent down from heaven.

Only child at his birth, the first by whom the iron

Cease and a golden race shall rise up with all the world,

Chaste Lucina, favor: now thy own Apollo reigns.

"Under your auspices, if there be any traces of our crimes remain,

Cancel the countries free from perpetual fear.

He will receive the life divisque

Mixed with heroes, and himself be seen by them,

His father's will rule a world at peace."]

The turning to asceticism resulting from the general expansion of Christianity brought about a new misfortune to many: monasticism and the life of the anchorite. [6]

Faust takes the reverse course; for him the ascetic ideal means death. He struggles for freedom and wins life, at the same time giving himself over to the Evil One; but through this he becomes the bringer of death to her whom he loves most, Marguerite. He tears himself away from pain and sacrifices his life in unceasing useful work, through which he saves many lives. [7] His double mission as saviour and destroyer has already been hinted in a preliminary manner:

Wagner:

With what a feeling, thou great man, must thou

Receive the people's honest veneration!

Faust:

Thus we, our hellish boluses compounding,

Among these vales and hills surrounding,

Worse than the pestilence, have passed.

Thousands were done to death from poison of my giving;

And I must hear, by all the living,

The shameless murderers praised at last!

A parallel to this double role is that text in the Gospel of Matthew which has become historically significant:

"I came not to send peace, but a sword." Matt, x: 34.

Just this constitutes the deep significance of Goethe's Faust, that he clothes in words a problem of modern man which has been turning in restless slumber since the Renaissance, just as was done by the drama of Oedipus for the Hellenic sphere of culture. What is to be the way out between the Scylla of renunciation of the world and the Charybdis of the acceptance of the world?

The hopeful tone, voiced in the "Hymn to the God of Creation," cannot continue very long with our author. The pose simply promises, but does not fulfil. The old longing will come again, for it is a peculiarity of all complexes worked over merely in the unconscious [8] that they lose nothing of their original amount of affect. Meanwhile, their outward manifestations can change almost endlessly. One might therefore consider the first poem as an unconscious longing to solve the conflict through positive religiousness, somewhat in the same manner as they of the earlier centuries decided their conscious conflicts by opposing to them the religious standpoint. This wish does not succeed. Now with the second poem there follows a second attempt which turns out in a decidedly more material way; its thought is unequivocal. Only once "having gained one raptured glance . . ." and then to die.

From the realms of the religious world, the attention, just as in Faust, [9] turns towards the sun of this world, and already there is something mingled with it which has another sense, that is to say, the moth which fluttered so long around the light that it burnt its wings.

We now pass to that which Miss Miller offers for the better understanding of the poem. She says:

"This small poem made a profound impression upon me. I could not, of course, find immediately a sufficiently clear and direct explanation for it. However, a few days later when I once more read a certain philosophical work, which I had read in Berlin the previous winter, and which I had enjoyed very much, (I was reading it aloud to a friend), I came across the following words: 'La meme aspiration passionnee de la mite vers l'etoile, de l'homme vers Dieu.' (The same passionate longing of the moth for the star, of man for God.) I had forgotten this sentence entirely, but it seemed very clear to me that precisely these words had reappeared in my hypnagogic poem. In addition to that it occurred to me that a play seen some years previously, 'La Mite et La Flamme,' was a further possible cause of the poem. It is easy to see how often the word 'moth' had been impressed upon me."

The deep impression made by the poem upon the author shows that she put into it a large amount of love. In the expression "aspiration passionnee" we meet the passionate longing of the moth for the star, of man for God, and indeed, the moth is Miss Miller herself. Her last observation that the word "moth" was often impressed upon her shows how often she had noticed the word "moth" as applicable to herself. Her longing for God resembles the longing of the moth for the "star." The reader will recall that this expression has already had a place in the earlier material, "when the morning stars sang together," that is to say, the ship's officer who sings on deck in the night watch. The passionate longing for God is the same as that longing for the singing morning stars. It was pointed out at great length in the foregoing chapter that this analogy is to be expected: "Sic parvis componere magna solebam."

It is shameful or exalted just as one chooses, that the divine longing of humanity, which is really the first thing to make it human, should be brought into connection with an erotic phantasy. Such a comparison jars upon the finer feelings. Therefore, one is inclined in spite of the undeniable facts to dispute the connection. An Italian steersman with brown hair and black moustache, and the loftiest, clearest conception of humanity! These two things cannot be brought together; against this not only our religious feelings revolt, but our taste also rebels.

It would certainly be unjust to make a comparison of the two objects as concrete things since they are so heterogeneous. One loves a Beethoven sonata but one loves caviar also. It would not occur to any one to liken the sonata to caviar. It is a common error for one to judge the longing according to the quality of the object. The appetite of the gourmand which is only satisfied with goose liver and quail is no more distinguished than the appetite of the laboring man for corned beef and cabbage. The longing is the same; the object changes. Nature is beautiful only by virtue of the longing and love given her by man. The aesthetic attributes emanating from that has influence primarily on the libido, which alone constitutes the beauty of nature. The dream recognizes this well when it depicts a strong and beautiful feeling by means of a representation of a beautiful landscape. Whenever one moves in the territory of the erotic it becomes altogether clear how little the object and how much the love means. The "sexual object" is as a rule overrated far too much and that only on account of the extreme degree to which libido is devoted to the object.

Apparently Miss Miller had but little left over for the officer, which is humanly very intelligible. But in spite of that a deep and lasting effect emanates from this connection which places divinity on a par with the erotic object. The moods which apparently are produced by these objects do not, however, spring from them, but are manifestations of her strong love. When Miss Miller praises either God or the sun she means her love, that deepest and strongest impulse of the human and animal being.

The reader will recall that in the preceding chapter the following chain of synonyms was adduced: the singer -- God of sound -- singing morning star -- creator -- God of Light -- sun -- fire -- God of Love.

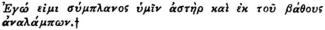

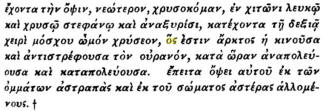

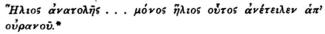

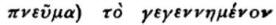

At that time we had placed sun and fire in parentheses. Now they are entitled to their right place in the chain of synonyms. With the changing of the erotic impression from the affirmative to the negative the symbols of light occur as the paramount object. In the second poem where the longing is clearly exposed it is by no means the terrestrial sun. Since the longing has been turned away from the real object, its object has become, first of all, a subjective one, namely, God. Psychologically, however, God is the name of a representation-complex which is grouped around a strong feeling (the sum of libido). Properly, the feeling is what gives character and reality to the complex. [10] The attributes and symbols of the divinity must belong in a consistent manner to the feeling (longing, love, libido, and so on). If one honors God, the sun or the fire, then one honors one's own vital force, the libido. It is as Seneca says: "God is near you, he is with you, in you." God is our own longing to which we pay divine honors. [11] If it were not known how tremendously significant religion was, and is, this marvellous play with one's self would appear absurd. There must be something more than this, however, because, notwithstanding its absurdity, it is, in a certain sense, conformable to the purpose in the highest degree. To bear a God within one's self signifies a great deal; it is a guarantee of happiness, of power, indeed even of omnipotence, as far as these attributes belong to the Deity. To bear a God within one's self signifies just as much as to be God one's self. In Christianity, where, it is true, the grossly sensual representations and symbols are weeded out as carefully as possible, which seems to be a continuation of the poverty of symbols of the Jewish cult, there are to be found plain traces of this psychology. There are even plainer traces, to be sure, in the "becoming-one with God" in those mysteries closely related to the Christian, where the mystic himself is lifted up to divine adoration through initiatory rites. At the close of the consecration into the Isis mysteries the mystic was crowned with the palm crown, [12] he was placed on a pedestal and worshipped as Helios. [13] In the magic papyrus of the Mithraic liturgy published by Dieterich there is the [ii] of the consecrated one:

[iii]

[iii]The mystic in religious ecstasies put himself on a plane with the stars, just as a saint of the Middle Ages put himself by means of the stigmata on a level with Christ. St. Francis of Assisi expressed this in a truly pagan manner, [14] even as far as a close relationship with the brother sun and the sister moon. These representations of "becoming-one with God" are very ancient. The old belief removed the becoming-one with God until the time after death; the mysteries, however, suggest this as taking place already in this world. A very old text brings most beautifully before one this unity with God; it is the song of triumph of the ascending soul. [15]

"I am the God Atum, I who alone was.

I am the God Re at his first splendor.

I am the great God, self-created, God of Gods,

To whom no other God compares."

"I was yesterday and know tomorrow; the battle-ground of Gods was made when I spoke. I know the name of that great God who tarries therein.

"I am that great Phoenix who is in Heliopolis, who there keeps account of all there is, of all that exists.

"I am the God Min, at his coming forth, who placed the feathers upon my head. [16]

"I am in my country. I come into my city. Daily I am together with my father Atum. [17]

"My impurity is driven away, and the sin which was in me is overcome. I washed myself in those two great pools of water which are in Heracleopolis, in which is purified the sacrifice of mankind for that great God who abideth there.

"I go on my way to where I wash my head in the sea of the righteous. I arrive at this land of the glorified, and enter through the splendid portal.

"Thou, who standest before me, stretch out to me thy hands, it is I. I am become one of thee. Daily am I together with my Father Atum."

The identification with God necessarily has as a result the enhancing of the meaning and power of the individual. [18] That seems, first of all, to have been really its purpose: a strengthening of the individual against his all too great weakness and insecurity in real life. This great megalomania thus has a genuinely pitiable background. The strengthening of the consciousness of power is, however, only an external result of the "becoming-one with God." Of much more significance are the deeper-lying disturbances in the realm of feeling. Whoever introverts libido -- that is to say, whoever takes it away from a real object without putting in its place a real compensation -- is overtaken by the inevitable results of introversion. The libido, which is turned inward into the subject, awakens again from among the sleeping remembrances one which contains the path upon which earlier the libido once had come to the real object. At the very first and in foremost position it was father and mother who were the objects of the childish love. They are unequalled and imperishable. Not many difficulties are needed in an adult's life to cause those memories to reawaken and to become effectual. In religion the regressive reanimation of the father-and-mother image is organized into a system. The benefits of religion are the benefits of parental hands; its protection and its peace are the results of parental care upon the child; its mystic feelings are the unconscious memories of the tender emotions of the first childhood, just as the hymn expresses it:

"I am in my country.

I come into my city.

Daily am I together with my father Atum." [19]

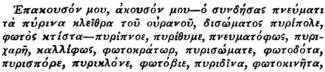

The visible father of the world is, however, the sun, the heavenly fire; therefore, Father, God, Sun, Fire are mythologically synonymous. The well-known fact that in the sun's strength the great generative power of nature honored shows plainly, very plainly, to any one to whom as yet it may not be clear that in the Deity man honors his own libido, and naturally in the form of the image or symbol of the present object of transference. This symbol faces us in an especially marked manner in the third Logos of the Dieterich papyrus. After the second prayer [20] stars come from the disc of the sun to the mystic, "five-pointed, in quantities, filling the whole air. If the sun's disc has expanded, you will see an immeasurable circle, and fiery gates which are shut off." The mystic utters the following prayer:

The invocation is, as one sees, almost inexhaustible in light and fire attributes, and can be likened in its extravagance only to the synonymous attributes of love of the mystic of the Middle Ages. Among the innumerable texts which might be used as an illustration of this, I select a passage from the writings of Mechtild von Magdeburg (1212-1277):

"O Lord, love me excessively and love me often and long; the oftener you love me, so much the purer do I become; the more excessively you love me, the more beautiful I become; the longer you love me, the more holy will I become here upon earth."

God answered: "That I love you often, that I have from my nature, for I myself am love. That I love you excessively, that I have from my desire, for I too desire that men love me excessively. That I love you long, that I have from my everlastingness, for I am without end." [21]

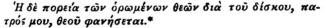

The religious regression makes use indeed of the parent image without, however, consciously making it an object of transference, for the incest horror [22] forbids that. It remains rather as a synonym, for example, of the father or of God, or of the more or less personified symbol of the sun and fire. [23] Sun and fire that is to say, the fructifying strength and heat -- are attributes of the libido. In Mysticism the inwardly perceived, divine vision is often merely sun or light, and is very little, or not at all, personified. In the Mithraic liturgy there is found, for example, a significant quotation:

[v]

[v]Hildegarde von Bingen (1100-1178) expresses herself in the following manner: [24]

"But the light I see is not local, but far off, and brighter than the cloud which supports the sun. I can in no way know the form of this light since I cannot entirely see the sun's disc. But within this light I see at times, and infrequently, another light which is called by me the living light, but when and in what manner I see this I do not know how to say, and when I see it all weariness and need is lifted from me, then too, I feel like a simple girl and not like an old woman."

Symeon, the New Theologian (970-1040), says the following:

"My tongue lacks words, and what happens in me my spirit sees clearly but does not explain. It sees the invisible, that emptiness of all forms, simple throughout, not complex, and in extent infinite. For it sees no beginning, and it sees no end. It is entirely unconscious of the meanings, and does not know what to call that which it sees. Something complete appears, it seems to me, not indeed through the being itself, but through a participation. For you enkindle fire from fire, and you receive the whole fire; but this remains undiminished and undivided, as before. Similarly, that which is divided separates itself from the first; and like something corporeal spreads itself into several lights. This, however, is something spiritual, immeasurable, indivisible, and inexhaustible. For it is not separated when it becomes many, but remains undivided and is in me, and enters within my poor heart like a sun or circular disc of the sun, similar to the light, for it is a light." [25]

That that thing, perceived as inner light, as the sun of the other world, is longing, is clearly shown by Symeon's words: [26]

"And following It my spirit demanded to embrace the splendor beheld, but it found It not as creature and did not succeed in coming out from among created beings, so that it might embrace that uncreated and uncomprehended splendor. Nevertheless it wandered everywhere, and strove to behold It. It penetrated the air, it wandered over the Heavens, it crossed over the abysses, it searched, as it seemed to it, the ends of the world. [27] But in all of that it found nothing, for all was created. And I lamented and was sorrowful, and my breast burned, and I lived as one distraught in mind. But It came, as It would, and descending like a luminous mystic cloud. It seemed to envelop my whole head so that dismayed I cried out. But flying away again It left me alone. And when I, troubled, sought for It, I realized suddenly that It was in me, myself, and in the midst of my heart It appeared as the light of a spherical sun."

In Nietzsche's "Glory and Eternity" we meet with an essentially similar symbol:

"Hush! I see vastness! -- and of vasty things

Shall man be done, unless he can enshrine

Them with his words? Then take the night which brings

The heart upon thy tongue, charmed wisdom mine!

"I look above, there rolls the star-strewn sea.

O night, mute silence, voiceless cry of stars!

And lo! A sign! The heaven its verge unbars --

A shining constellation falls towards me." [vi]

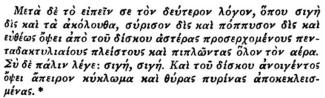

It is not astonishing if Nietzsche's great inner loneliness calls again into existence certain forms of thought which the mystic ecstasy of the old cults has elevated to ritual representation. In the visions of the Mithraic liturgy we have to deal with many similar representations which we can now understand without difficulty as the ecstatic symbol of the libido:

[vii]

[vii]Silence is commanded, then the vision of light is revealed. The similarity of the mystic's condition and Nietzsche's poetical vision is surprising. Nietzsche says "constellation." It is well known that constellations are chiefly therio- or anthropomorphic symbols.

The papyrus says,

[viii] (similar to the "rosy-fingered" Eos), which is nothing else than an anthropomorphic image. Accordingly, one may expect from that, that by long gazing a living being would be formed out of the "flame image," a "star constellation" of therio- or anthropomorphic nature, for the symbolism of the libido does not end with sun, light and fire, but makes use of wholly other means of expression. I yield precedence to Nietzsche:

[viii] (similar to the "rosy-fingered" Eos), which is nothing else than an anthropomorphic image. Accordingly, one may expect from that, that by long gazing a living being would be formed out of the "flame image," a "star constellation" of therio- or anthropomorphic nature, for the symbolism of the libido does not end with sun, light and fire, but makes use of wholly other means of expression. I yield precedence to Nietzsche:The Beacon [ix]

"Here, where the island grew amid the seas,

A sacrificial rock high-towering,

Here under darkling heavens,

Zarathustra lights his mountain-fires.

"These flames with grey-white belly,

In cold distances sparkle their desire,

Stretches its neck towards ever purer heights --

A snake upreared in impatience:

"This signal I set up there before me.

This flame is mine own soul,

Insatiable for new distances,

Speeding upward, upward its silent heat.

"At all lonely ones I now throw my fishing rod.

Give answer to the flame's impatience,

Let me, the fisher on high mountains,

Catch my seventh, last solitude!"

Here libido becomes fire, flame and snake. The Egyptian symbol of the "living disc of the sun," the disc with the two entwining snakes, contains the combination of both the libido analogies. The disc of the sun with its fructifying warmth is analogous to the fructifying warmth of love. The comparison of the libido with sun and fire is in reality analogous.

There is also a "causative" element in it, for sun and fire as beneficent powers are objects of human love; for example, the sun-hero Mithra is called the "well-beloved." In Nietzsche's poem the comparison is also a causative one, but this time in a reversed sense. The comparison with the snake is unequivocally phallic, corresponding completely with the tendency in antiquity, which was to see in the symbol of the phallus the quintessence of life and fruitfulness. The phallus is the source of life and libido, the great creator and worker of miracles, and as such it received reverence everywhere. We have, therefore, three designating symbols of the libido: First, the comparison by analogy, as sun and fire. Second, the comparisons based on causative relations, as A: Object comparison. The libido is designated by its object, for example, the beneficent sun. B: The subject comparison, in which the libido is designated by its place of origin or by analogies of this, for example, by phallus or (analogous) snake.

To these two fundamental forms of comparison still a third is added, in which the "tertium comparationis" is the activity; for example, the libido is dangerous when fecundating like the bull -- through the power of its passion -- like the lion, like the raging boar when in heat, like the ever-rutting ass, and so on.

This activity comparison can belong equally well to the category of the analogous or to the category of the causative comparisons. The possibilities of comparison mean just as many possibilities for symbolic expression, and from this basis all the infinitely varied symbols, so far as they are libido images, may properly be reduced to a very simple root, that is, just to libido and its fixed primitive qualities. This psychologic reduction and simplification is in accordance with the historic efforts of civilization to unify and simplify, to syncretize, the endless number of the gods. We come across this desire as far back as the old Egyptians, where the unlimited polytheism as exemplified in the numerous demons of places finally necessitated simplification. All the various local gods, Amon of Thebes, Horus of Edfu, Horus of the East, Chnum of Elephantine, Atum of Heliopolis, and others, [29] became identified with the sun God Re. In the hymns to the sun the composite being Amon-Re-Harmachis-Atum was invoked as "the only god which truly lives." [30]

Amenhotep IV (XVIII dynasty) went the furthest in this direction. He replaced all former gods by the "living great disc of the sun," the official title reading:

"The sun ruling both horizons, triumphant in the horizon in his name; the glittering splendor which is in the sun's disc."

"And, indeed," Erman adds, [31] "the sun, as a God, should not be honored, but the sun itself as a planet which imparts through its rays [32] the infinite life which is in it to all living creatures."

Amenhotep IV by his reform completed a work which is psychologically important. He united all the bull, [33] ram, [34] crocodile [35] and pile-dwelling [36] gods into the disc of the sun, and made it clear that their various attributes were compatible with the sun's attributes. [37] A similar fate overtook the Hellenic and Roman polytheism through the syncretistic efforts of later centuries. The beautiful prayer of Lucius [38] to the queen of the Heavens furnishes an important proof of this:

"Queen of Heaven, whether thou art the genial Ceres, the prime parent of fruits; -- or whether thou art celestial Venus; -- or whether thou art the sister of Phoebus; -- or whether thou art Proserpina, terrific with midnight howlings -- with that feminine brightness of thine illuminating the walls of every city." [39]

This attempt to gather again into a few units the religious thoughts which were divided into countless variations and personified in individual gods according to their polytheistic distribution and separation makes clear the fact that already at an earlier time analogies had formally arisen. Herodotus is rich in just such references, not to mention the systems of the Hellenic-Roman world. Opposed to the endeavor to form a unity there stands a still stronger endeavor to create again and again a multiplicity, so that even in the so-called severe monotheistic religions, as Christianity, for example, the polytheistic tendency is irrepressible. The Deity is divided into three parts at least, to which is added the feminine Deity of Mary and the numerous company of the lesser gods, the angels and saints, respectively. These two tendencies are in constant warfare. There is only one God with countless attributes, or else there are many gods who are then simply known differently, according to locality, and personify sometimes this, sometimes that attribute of the fundamental thought, an example of which we have seen above in the Egyptian gods.

With this we turn once more to Nietzsche's poem, "The Beacon." We found the flame there used as an image of the libido, theriomorphically represented as a snake (also as an image of the soul: [40] "This flame is mine own soul"). We saw that the snake is to be taken as a phallic image of the libido (upreared in impatience), and that this image, also an attribute of the conception of the sun (the Egyptian sun idol), is an image of the libido in the combination of sun and phallus. It is not a wholly strange conception, therefore, that the sun's disc is represented with a penis, as well as with hands and feet. We find proof for this idea in a peculiar part of the Mithraic liturgy:

[x]

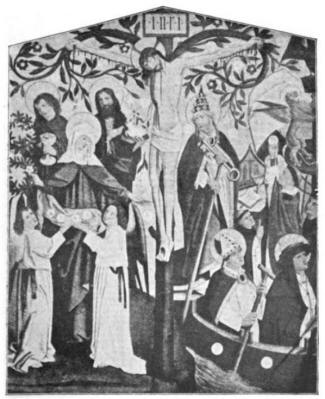

[x]This extremely important vision of a tube hanging down from the sun would produce in a religious text, such as that of the Mithraic liturgy, a strange and at the same time meaningless effect if it did not have the phallic meaning. The tube is the place of origin of the wind. The phallic meaning seems very faint in this idea, but one must remember that the wind, as well as the sun, is a fructifier and creator. This has already been pointed out in a footnote. [41] There is a picture by a Germanic painter of the Middle Ages of the "conceptio immaculata" which deserves mention here. The conception is represented by a tube or pipe coming down from heaven and passing beneath the skirt of Mary. Into this flies the Holy Ghost in the form of a dove for the impregnation of the Mother of God. [42]

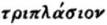

Honegger discovered the following hallucination in an insane man (paranoid dement): The patient sees in the sun an "upright tail" similar to an erected penis. When he moves his head back and forth, then, too, the sun's penis sways back and forth in a like manner, and out of that the wind arises. This strange hallucination remained unintelligible to us for a long time until I became acquainted with the Mithraic liturgy and its visions. This hallucination threw an illuminating light, as it appears to me, upon a very obscure place in the text which immediately follows the passage previously cited:

Mead translates this very clearly: [43]

"And towards the regions westward, as though it were an infinite East wind. But if the other wind, towards the regions of the East, should be in service, in the like fashion shalt thou see towards the regions of that side the converse of the sight."

In the original

is the vision, the thing seen.

is the vision, the thing seen.  means properly the carrying away. The sense of the text, according to this, might be: the thing seen may be carried or turned sometimes here, sometimes there, according to the direction of the wind. The

means properly the carrying away. The sense of the text, according to this, might be: the thing seen may be carried or turned sometimes here, sometimes there, according to the direction of the wind. The  is the tube, "the place of origin of the wind," which turns sometimes to the east, sometimes to the west, and, one might add, generates the corresponding wind. The vision of the insane man coincides astonishingly with this description of the movement of the tube. [44]

is the tube, "the place of origin of the wind," which turns sometimes to the east, sometimes to the west, and, one might add, generates the corresponding wind. The vision of the insane man coincides astonishingly with this description of the movement of the tube. [44] At the point of contact between leaders and followers reside ideologies. The term "ideology" is used here in quite a loose sense. It refers to any idea or set of ideas that provides a prescriptive view of life. The term is therefore not confined to lengthy doctrines that are systematized in the form of a tract or a dissertation, since ideologies may also be expressed by short slogans. Moreover, they can be loaded with different layers of meaning. They can consist of a formalized and presumably conscious worldview that includes many parts. But they can equally well be comprised of unconscious shared group fantasies, which have the power to charge up the entire group with sufficient energy to trigger unified mass action. Consequently they frequently include myths while their promoters engage in the selling of those myths. Moreover, slogans, catch phrases, enticing ideas, poignant jokes, stirring songs but also a variety of visual images that appear on posters, placards, and walls as well as in illustrations and cartoons published by newspapers and magazines may all represent small bits or chunks of ideologies. Whatever form they take, whether it is one picture that is worth more than a thousand words or an uplifting short slogan, these bits and chunks of ideology encapsulate succinct and rather unidimensional views of the world or of national life. What is more, they may be widely dispersed and "float in the air." When that happens, the ideological prescriptions frequently express themselves through aphorisms. A current American example would be the saying "winning isn't everything, it's the only thing." An earlier German example which is taken from a Nazi marching song would be the lines "For today Germany belongs to us and tomorrow the whole world." As can be seen, such small ideological segments, which prescribe what to expect from life, ride on a variety of "carriers." That is why they may frequently be lifted from songs, plays, jokes, drawings or paintings, political speeches and similar layers of the cultural repository. They are embedded in the culture but their drawing power fluctuates according to the position they happen to occupy in the particular zeitgeist, or spirit of the time. The zeitgeist is a concept that denotes the ripening of a cultural image or idea to the point where its time has arrived. It also connotes a notion of movement where ideas float to the foreground when their time comes or sink to the background when their time is gone. The issue of when an ideology's time for action has arrived is largely determined by changes within the zeitgeist that reflect an altered emotional climate and the shifting winds of public mood.

-- The Roots of Nazi Psychology, by Jay Y. Gonen

The various attributes of the sun, separated into a series, appear one after the other in the Mithraic liturgy. According to the vision of Helios, seven maidens appear with the heads of snakes, and seven gods with the heads of black bulls.

It is easy to understand the maiden as a symbol of the libido used in the sense of causative comparison. The snake in Paradise is usually considered as feminine, as the seductive principle in woman, and is represented as feminine by the old artists, although properly the snake has a phallic meaning. Through a similar change of meaning the snake in antiquity becomes the symbol of the earth, which on its side is always considered feminine. The bull is the well-known, symbol for the fruitfulness of the sun. The bull gods in the Mithraic liturgy were called

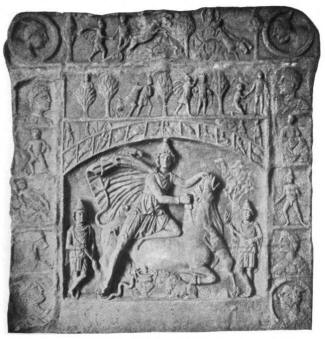

"guardians of the axis of the earth," by whom the axle of the orb of the heavens was turned. The divine man, Mithra, also had the same attributes; he is sometimes called the "Sol invictus" itself, sometimes the mighty companion and ruler of Helios; he holds in his right hand the " bear constellation, which moves and turns the heavens." The bull-headed gods, equally

"guardians of the axis of the earth," by whom the axle of the orb of the heavens was turned. The divine man, Mithra, also had the same attributes; he is sometimes called the "Sol invictus" itself, sometimes the mighty companion and ruler of Helios; he holds in his right hand the " bear constellation, which moves and turns the heavens." The bull-headed gods, equally  with Mithra himself, to whom the attribute

with Mithra himself, to whom the attribute  , "young one," "the newcomer," is given, are merely attributive components of the same divinity. The chief god of the Mithraic liturgy is himself subdivided into Mithra and Helios; the attributes of each of these are closely related to the other. Of Helios it is said:

, "young one," "the newcomer," is given, are merely attributive components of the same divinity. The chief god of the Mithraic liturgy is himself subdivided into Mithra and Helios; the attributes of each of these are closely related to the other. Of Helios it is said:

[xi]

[xi]Of Mithra it is said:

[xii]

[xii]If we place fire and gold as essentially similar, then a great accord is found in the attributes of the two gods. To these mystical pagan ideas there deserve to be added the probably almost contemporaneous vision of Revelation:

"And being turned, I saw seven golden candlesticks. And in the midst of the candlesticks [45] one like unto the son of man, clothed with a garment down to the foot, and girt about at the breasts with a golden girdle. And his head and his hair were white as white wool, white as snow, and his eyes were as a flame of fire. And his feet like unto burnished brass, as if it had been refined in a furnace; and his voice as the sound of many waters. And he had in his right hand seven stars, [46] and out of his mouth proceeded a sharp two- edged sword, [47] and his countenance was as the sun shineth in his strength." -- Rev. i: 12 ff.

"And I looked, and beheld a white cloud, and upon the cloud I saw one sitting like unto the son of man, having on his head a golden crown, and in his hand a sharp sickle." [48] -- Rev. xiv: 14.

"And his eyes were as a flame of fire, and upon his head were many diadems. And he was arrayed in a garment [49] sprinkled with blood. . . . And the armies which were in heaven followed him upon white horses, clothed in fine linen, [50] white and pure. And out of his mouth proceeded a sharp sword." -- Rev. xix: 12-15.

THE FIRE OF TRUTH PRODUCES

LIGHT AND ILLUMINATION

WE ARE ABLE TO BRING ABOUT ILLUMINATION BY BURNING

MORE INTENSELY IN OUR LIVES

BY BEARING THE COSMIC CROSS

BY OFFERING OUR SELF

AS A JOYFUL SACRIFICE

DECREPITUDE AND OLD AGE ARE A SIGN OF THE PROCESS OF

COMBUSTION WHICH HAS TRANSFORMED THE PHYSICAL BODY AT

ITS OWN EXPENSE INTO A SUBTLE BODY, INTO THE BODY

OF RESURRECTION. OUR SUFFERINGS ARE A SIGN OF BEING BURNED, OF

BEING ANNIHILATED IN OUR EGO.

THE MORE WE ARE SHATTERED THE MORE OUR CONSCIOUSNESS

RISES WITH GREATER BRIGHTNESS, GREATER INCANDESCENCE

WE GLOW

WE BECOME TRANSPARENT TO LIGHT

THIS IS THE PASSAGE FROM FIRE TO

LIGHTABRAHAM TURNED THE SWORD, WHICH WAS SUPPOSED TO HAVE

SACRIFICED ISAAC, UPWARDS, AND IT BECAME THE FLAMING

SWORD WHICH BREAKS THROUGH ALL PLANES, RESULTING IN THE

PRODUCTION OF LIGHT. ALL THIS MAKES POSSIBLE, IN THE

HEKALOTH OF THE JEWS, THE PASSAGE OF SOULS FROM THE

FOURTH PLANE, THE PLANE OF THE SERAPHIM, WHO ARE ANGELS

OF FIRE, TO THE FIFTH PLANE, THE PLANE OF THE CHERUBIM, WHO

ARE BEINGS OF LIGHT. EVERYTHING SEEMS TO TEND TO MAKE

US PURE CONSCIOUSNESS. THE FIRE IS ONE'S VIBRATION TO THE

TRUTH, AND IT IS THAT WHICH TRANSFORMS ONE INTO A BEING OF

LIGHT.

IT IS A MATTER OF BECOMING AWARE OF THE PROCESS OF COMBUSTION

IN OURSELVES BY FANNING THE FIRE IN THE SOLAR

PLEXUS WITH THE BREATH, THEREBY REALIZING THE PURIFYING

IGNEOUS ELEMENT IN OUR MAGNETIC FIELD.

IN A CERTAIN SENSE WE ARE LIKE A FLAME. THE BUDDHISTS HAVE

THE IMAGE OF THE FLAME THAT PASSES FROM LOG TO LOG, BURNING

THROUGH LOG AFTER LOG; FOR THE FLAME TO PERSIST THERE

ALWAYS HAS TO BE ANOTHER LOG, OTHERWISE THE FLAME IS

EXTINGUISHED. THE LOWER ASPECT OF OUR CONSCIOUSNESS IS

LIKE A FLAME WHICH DEPENDS ON WHAT IT CAN BURN. IN A CERTAIN

SENSE THIS FLAME IS OUR DESIRES, OUR CRAVINGS. WE ARE A

CONTINUITY OF CRAVINGS: THE CRAVING OF ONE BEING IS

CONTINUED THROUGH ANOTHER BEING, THE WHOLE OF LIFE

IS TENSIONED TOWARD THE FULFILLMENT OF DESIRE.

RESURRECTION IS THE OVERCOMING OF DESIRE

WE ARE FIRE WHICH IS BURNING NOT ONLY OUR BODIES BUT OUR

PERSONALITIES

UNTIL THEY ARE PURIFIED AND ILLUMINATED

PURIFICATION HAPPENS WHEN THERE IS JUST COLD LIGHT.

IN THE HEART CENTER THERE IS HEAT AND LIGHT, IN THE THROAT

CENTER THERE IS HEAT AND NO LIGHT, AND IN THE HIGHER

CENTERS THERE IS JUST THIS COLD LIGHT AND NO HEAT. BY HAMMERING

THE FIRE IN THE SOLAR PLEXUS WE UNLEASH A CHAIN

REACTION WHICH WILL IGNITE THE LIGHT OF THE SUN IN THE

HEART CENTER, WHICH WILL THEN BE SUBLIMATED INTO THE

COLD LIGHT OF THE CROWN CENTER, A VERY COOL TRANSCENDENTAL

LIGHT CORRESPONDING TO THE LIGHT OF VERY HIGH

ALTITUDES, ALMOST FROZEN, IMMACULATE AND DIAPHANOUS,

RISING LIKE A FOUNTAIN OF LIGHT ABOVE THE TOP OF THE HEAD.

-- Toward the One, by Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan

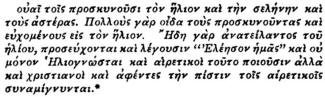

, called Christ the

, called Christ the  [xiii] [Helios, the rising sun -- the only sun rising from heaven!]

[xiii] [Helios, the rising sun -- the only sun rising from heaven!]

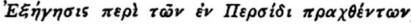

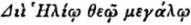

[xvi]

[xvi] , edited by Wirth. [61] This is a book of fables, but, nevertheless, a mine for near-Christian phantasies, which gives a profound insight into Christian symbolism. In this is found the following magical dedication:

, edited by Wirth. [61] This is a book of fables, but, nevertheless, a mine for near-Christian phantasies, which gives a profound insight into Christian symbolism. In this is found the following magical dedication:

[xvii] In certain parts of Armenia the rising sun is still worshipped by Christians, that "it may let its foot rest upon the faces of the worshippers." [62] The foot occurs as an anthropomorphic attribute, and we have already met the theriomorphic attribute in the feathers and the sun phallus. Other comparisons of the sun's ray, as knife, sword, arrow, and so on, have also, as we have learned from the psychology of the dream, a phallic meaning at bottom. This meaning is attached to the foot as I here point out, [63] and also to the feathers, or hair, of the sun, which signify the power or strength of the sun. I refer to the story of Samson, and to that of the Apocalypse of Baruch, concerning the phoenix bird, which, flying before the sun, loses its feathers, and, exhausted, is strengthened again in an ocean bath at evening.

[xvii] In certain parts of Armenia the rising sun is still worshipped by Christians, that "it may let its foot rest upon the faces of the worshippers." [62] The foot occurs as an anthropomorphic attribute, and we have already met the theriomorphic attribute in the feathers and the sun phallus. Other comparisons of the sun's ray, as knife, sword, arrow, and so on, have also, as we have learned from the psychology of the dream, a phallic meaning at bottom. This meaning is attached to the foot as I here point out, [63] and also to the feathers, or hair, of the sun, which signify the power or strength of the sun. I refer to the story of Samson, and to that of the Apocalypse of Baruch, concerning the phoenix bird, which, flying before the sun, loses its feathers, and, exhausted, is strengthened again in an ocean bath at evening.

, the great gods. Their near relations are the "Idaean dactyli " (finger or Idaean thumb), [10] to whom the mother of the gods had taught the blacksmith's art. ("The key will scent the true place from all others! follow it down! -- 't will lead thee to the Mothers!") They were the first leaders, the teachers of Orpheus, and invented the Ephesian magic formulas and the musical rhythms. [11] The characteristic disparity which is shown above in the Upanishad text, and in "Faust," is also found here, since the gigantic Hercules passed as an Idaean dactyl.

, the great gods. Their near relations are the "Idaean dactyli " (finger or Idaean thumb), [10] to whom the mother of the gods had taught the blacksmith's art. ("The key will scent the true place from all others! follow it down! -- 't will lead thee to the Mothers!") They were the first leaders, the teachers of Orpheus, and invented the Ephesian magic formulas and the musical rhythms. [11] The characteristic disparity which is shown above in the Upanishad text, and in "Faust," is also found here, since the gigantic Hercules passed as an Idaean dactyl. , together with a figure of a boy as

, together with a figure of a boy as  , followed by a caricatured boy's figure designated as

, followed by a caricatured boy's figure designated as  and then again a caricatured man, which is represented as

and then again a caricatured man, which is represented as  .

.  really means thread, but in orphic speech it stands for semen. It was conjectured that this collection corresponded to a group of statuary in the sanctuary of a cult. This supposition is supported by the history of the cult as far as it is known; it is an original Phoenician cult of father and son; [21] of an old and young Cabir who were more or less assimilated with the Grecian gods. The double figures of the adult and the child Dionysus lend themselves particularly to this assimilation. One might also call this the cult of the large and small man. Now, under various aspects, Dionysus is a phallic god in whose worship the phallus held an important place; for example, in the cult of the Argivian Bull -- Dionysus. Moreover, the phallic herme of the god has given occasion for a personification of the phallus of Dionysus, in the form of the god Phales, who is nothing else but a Priapus. He is called

really means thread, but in orphic speech it stands for semen. It was conjectured that this collection corresponded to a group of statuary in the sanctuary of a cult. This supposition is supported by the history of the cult as far as it is known; it is an original Phoenician cult of father and son; [21] of an old and young Cabir who were more or less assimilated with the Grecian gods. The double figures of the adult and the child Dionysus lend themselves particularly to this assimilation. One might also call this the cult of the large and small man. Now, under various aspects, Dionysus is a phallic god in whose worship the phallus held an important place; for example, in the cult of the Argivian Bull -- Dionysus. Moreover, the phallic herme of the god has given occasion for a personification of the phallus of Dionysus, in the form of the god Phales, who is nothing else but a Priapus. He is called  or

or  [ii]. [22] Corresponding to this state of affairs, one cannot very well fail to recognize in the previously mentioned Cabiric representation, and in the added boy's figure, the picture of man and his penis. [23] The previously mentioned paradox in the Upanishad text of large and small, of giant and dwarf, is expressed more mildly here by man and boy, or father and son. [24] The motive of deformity which is used constantly by the Cabiric cult is present also in the vase picture, while the parallel figures to Dionysus and

[ii]. [22] Corresponding to this state of affairs, one cannot very well fail to recognize in the previously mentioned Cabiric representation, and in the added boy's figure, the picture of man and his penis. [23] The previously mentioned paradox in the Upanishad text of large and small, of giant and dwarf, is expressed more mildly here by man and boy, or father and son. [24] The motive of deformity which is used constantly by the Cabiric cult is present also in the vase picture, while the parallel figures to Dionysus and  are the caricatured

are the caricatured  and

and  . Just as formerly the difference in size gave occasion for division, so does the deformity here. [25]

. Just as formerly the difference in size gave occasion for division, so does the deformity here. [25] appellant, nos appellamus voluntatem; earn illi putant in solo esse sapiente, quam sic definiunt; voluntas est quae quid cum ratione desiderat : quae autem ratione adversa incitata est vehementius, ea libido est, vel cupiditas effrenata, quae in omnibus stultis invenitur." [iii]*

appellant, nos appellamus voluntatem; earn illi putant in solo esse sapiente, quam sic definiunt; voluntas est quae quid cum ratione desiderat : quae autem ratione adversa incitata est vehementius, ea libido est, vel cupiditas effrenata, quae in omnibus stultis invenitur." [iii]* ), the world-soul with the moon (

), the world-soul with the moon ( ). In another comparison Plotinus compares "The One" with the Father, the intellect with the Son. [20] The "One" designated as Uranus is transcendent. The son as Kronos has dominion over the visible world. The world-soul (designated as Zeus) appears as subordinate to him. The "One," or the Usia of the whole existence is designated by Plotinus as hypostatic, also as the three forms of emanation, also

). In another comparison Plotinus compares "The One" with the Father, the intellect with the Son. [20] The "One" designated as Uranus is transcendent. The son as Kronos has dominion over the visible world. The world-soul (designated as Zeus) appears as subordinate to him. The "One," or the Usia of the whole existence is designated by Plotinus as hypostatic, also as the three forms of emanation, also  . [i] As Drews observed, this is also the formula of the Christian Trinity (God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost) as it was decided upon at the councils of Nicea and Constantinople. [21] It may also be noticed that certain early Christian sectarians attributed a maternal significance to the Holy Ghost (world-soul, moon). (See what follows concerning Chi of Timaeus.) According to Plotinus, the world-soul has a tendency toward a divided existence and towards divisibility, the conditio sine qua non of all change, creation and procreation (also a maternal quality). It is an "unending all of life" and wholly energy; it is a living organism of ideas, which attain in it effectiveness and reality. [22] The intellect is its procreator, its father, which, having conceived it, brings it to development in thought. [23]

. [i] As Drews observed, this is also the formula of the Christian Trinity (God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost) as it was decided upon at the councils of Nicea and Constantinople. [21] It may also be noticed that certain early Christian sectarians attributed a maternal significance to the Holy Ghost (world-soul, moon). (See what follows concerning Chi of Timaeus.) According to Plotinus, the world-soul has a tendency toward a divided existence and towards divisibility, the conditio sine qua non of all change, creation and procreation (also a maternal quality). It is an "unending all of life" and wholly energy; it is a living organism of ideas, which attain in it effectiveness and reality. [22] The intellect is its procreator, its father, which, having conceived it, brings it to development in thought. [23] , which means "to learn," and has explained this conceptual relationship. [7] The "tertium comparationis" might lie in the rhythm, the movement to and fro in the mind. According to Kuhn, the root "manth" or "math" must be traced from

, which means "to learn," and has explained this conceptual relationship. [7] The "tertium comparationis" might lie in the rhythm, the movement to and fro in the mind. According to Kuhn, the root "manth" or "math" must be traced from  to

to  to

to  [i ] who is the Greek fire-robber. Through an unauthorized Sanskrit word "pramathyus," which comes by way of "pramantha," and which possesses the double meaning of "Rubber" and "Robber," the transition to Prometheus was effected. With that, however, the prefix "pra" caused special difficulty, so that the whole derivation was doubted by a series of authors, and was held, in part, as erroneous. On the other hand, it was pointed out that as the Thuric Zeus bore the especially interesting cognomen

[i ] who is the Greek fire-robber. Through an unauthorized Sanskrit word "pramathyus," which comes by way of "pramantha," and which possesses the double meaning of "Rubber" and "Robber," the transition to Prometheus was effected. With that, however, the prefix "pra" caused special difficulty, so that the whole derivation was doubted by a series of authors, and was held, in part, as erroneous. On the other hand, it was pointed out that as the Thuric Zeus bore the especially interesting cognomen  , thus

, thus  might not be an original Indo-Germanic stem word that was related to the Sanskrit "pramantha," but might represent only a cognomen. This interpretation is supported by a gloss of Hesychius,

might not be an original Indo-Germanic stem word that was related to the Sanskrit "pramantha," but might represent only a cognomen. This interpretation is supported by a gloss of Hesychius,

. [ii] Another gloss of Hesychius explains

. [ii] Another gloss of Hesychius explains  as

as  , through which

, through which  attains the meaning of "the flaming one," analogous to

attains the meaning of "the flaming one," analogous to  or

or  . [8] The relation of Prometheus to pramantha could scarcely be so direct as Kuhn conjectures. The question of an indirect relation is not decided with that. Above all,

. [8] The relation of Prometheus to pramantha could scarcely be so direct as Kuhn conjectures. The question of an indirect relation is not decided with that. Above all,  is of great significance as a surname for

is of great significance as a surname for  , since the "flaming one" is the "fore-thinker." (Pramati = precaution is also an attribute of Agni, although pramati is of another derivation.) Prometheus, however, belongs to the line of Phlegians which was placed by Kuhn in uncontested relationship to the Indian priest family of Bhrgu. [9] The Bhrgu are like Matarigvan (the "one swelling in the mother"), also fire-bringers. Kuhn quotes a passage, according to which Bhrgu also arises from the flame like Agni. ("In the flame Bhrgu originated. Bhrgu roasted, but did not burn.") This view leads to a root related to Bhrgu, that is to say, to the Sanskrit bhray = to light, Latin fulgeo and Greek

, since the "flaming one" is the "fore-thinker." (Pramati = precaution is also an attribute of Agni, although pramati is of another derivation.) Prometheus, however, belongs to the line of Phlegians which was placed by Kuhn in uncontested relationship to the Indian priest family of Bhrgu. [9] The Bhrgu are like Matarigvan (the "one swelling in the mother"), also fire-bringers. Kuhn quotes a passage, according to which Bhrgu also arises from the flame like Agni. ("In the flame Bhrgu originated. Bhrgu roasted, but did not burn.") This view leads to a root related to Bhrgu, that is to say, to the Sanskrit bhray = to light, Latin fulgeo and Greek  (Sanskrit bhargas = splendor, Latin fulgur). Bhrgu appears, therefore, as "the shining one."

(Sanskrit bhargas = splendor, Latin fulgur). Bhrgu appears, therefore, as "the shining one."  means a certain species of eagle, on account of its burnished gold color. The connection with

means a certain species of eagle, on account of its burnished gold color. The connection with , which signifies "to burn," is clear. The Phlegians are also the fire eagles. [10] Prometheus also belongs to the Phlegians. The path from Pramantha to Prometheus passes not through the word, but through the idea, and, therefore, we should adopt this same meaning for Prometheus as that which Pramantha attains from the Hindoo fire symbolism. [11]

, which signifies "to burn," is clear. The Phlegians are also the fire eagles. [10] Prometheus also belongs to the Phlegians. The path from Pramantha to Prometheus passes not through the word, but through the idea, and, therefore, we should adopt this same meaning for Prometheus as that which Pramantha attains from the Hindoo fire symbolism. [11]

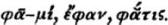

[iv], in old Icelandic ban = white, in New High German bohnen = to make shining. The same root bha also designates "to speak"; it is found in Sanskrit bhan = to speak, Armenian ban = word, in New High German bann to banish, Greek

[iv], in old Icelandic ban = white, in New High German bohnen = to make shining. The same root bha also designates "to speak"; it is found in Sanskrit bhan = to speak, Armenian ban = word, in New High German bann to banish, Greek  [v] Latin fa-ri fanum.

[v] Latin fa-ri fanum. = bright, Lithuanian balti = to become white, Middle High German blasz = pale.

= bright, Lithuanian balti = to become white, Middle High German blasz = pale. , Attic

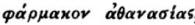

, Attic  = Vulcan. This same root vel means also "to sound"; in Sanskrit vani = tone, song, music. Tschech volati = to call.

= Vulcan. This same root vel means also "to sound"; in Sanskrit vani = tone, song, music. Tschech volati = to call. [vii] in the stimulating wine, so Agni is the Soma, the holy drink of inspiration, the mead of immortality. [46] Soma and Fire are entirely identical in Hindoo literature, so that in Soma we easily rediscover the libido symbol, through which a series of apparently paradoxical qualities of the Soma are immediately explained. As the old Hindoos recognized in fire an emanation of the inner libido fire, so too they recognized, in the intoxicating drink (Firewater, Soma-Agni, as rain and fire), an emanation of libido. The Vedic definition of Soma as seminal fluid confirms this interpretation. [47] The Soma significance of fire, similar to the significance of the body of Christ in the Last Supper (compare the Passover lamb of the Jews, baked in the form of a cross), is explained by the psychology of the presexual stage, where the libido was still in part the function of nutrition. The "Soma" is the "nourishing drink," the mythological characterization of which runs parallel to fire in its origin; therefore, both are united in Agni. The drink of immortality was stirred by the Hindoo gods like fire. Through the retreat of the libido into the presexual stage it becomes clear why so many gods were either defined sexually or were devoured.

[vii] in the stimulating wine, so Agni is the Soma, the holy drink of inspiration, the mead of immortality. [46] Soma and Fire are entirely identical in Hindoo literature, so that in Soma we easily rediscover the libido symbol, through which a series of apparently paradoxical qualities of the Soma are immediately explained. As the old Hindoos recognized in fire an emanation of the inner libido fire, so too they recognized, in the intoxicating drink (Firewater, Soma-Agni, as rain and fire), an emanation of libido. The Vedic definition of Soma as seminal fluid confirms this interpretation. [47] The Soma significance of fire, similar to the significance of the body of Christ in the Last Supper (compare the Passover lamb of the Jews, baked in the form of a cross), is explained by the psychology of the presexual stage, where the libido was still in part the function of nutrition. The "Soma" is the "nourishing drink," the mythological characterization of which runs parallel to fire in its origin; therefore, both are united in Agni. The drink of immortality was stirred by the Hindoo gods like fire. Through the retreat of the libido into the presexual stage it becomes clear why so many gods were either defined sexually or were devoured. designates a cracking, snapping or blowing sound. It is used of kissing; by Theocritus also of the associated noise of flute blowing. The etymologic parallels show a remarkable relationship between the part of the body in question and the child. This relationship we will mention here, only to let it drop at once, as this question will claim our attention later.

designates a cracking, snapping or blowing sound. It is used of kissing; by Theocritus also of the associated noise of flute blowing. The etymologic parallels show a remarkable relationship between the part of the body in question and the child. This relationship we will mention here, only to let it drop at once, as this question will claim our attention later. . The Sun mounts like a goat to the highest mountain, and later goes into the water as a fish. The fish is the symbol of the child, [48] for the child before his birth lives in the water like a fish, and the Sun, because it plunges into the sea, becomes equally child and fish. The fish, however, is also a phallic symbol, [49] also a symbol for the woman. [50] Briefly stated, the fish is a libido symbol, and, indeed, as it seems predominately for the renewal of the libido.

. The Sun mounts like a goat to the highest mountain, and later goes into the water as a fish. The fish is the symbol of the child, [48] for the child before his birth lives in the water like a fish, and the Sun, because it plunges into the sea, becomes equally child and fish. The fish, however, is also a phallic symbol, [49] also a symbol for the woman. [50] Briefly stated, the fish is a libido symbol, and, indeed, as it seems predominately for the renewal of the libido.

." [i] [58] An observation likewise referring to the Trinity is made by Plutarch concerning Ormuzd:

." [i] [58] An observation likewise referring to the Trinity is made by Plutarch concerning Ormuzd:  . [ii] The Trinity, as three different states of the unity, is also a Christian thought. In the very first place this suggests a sun myth. An observation by Macrobius i: 18 seems to lend support to this idea:

. [ii] The Trinity, as three different states of the unity, is also a Christian thought. In the very first place this suggests a sun myth. An observation by Macrobius i: 18 seems to lend support to this idea:

[iv] from the phallic symbolism, the originality of which may well be uncontested. [64] The male genitals are the basis for this Trinity. It is an anatomical fact that one testicle is generally placed somewhat higher than the other, and it is also a very old, but, nevertheless, still surviving, superstition that one testicle generates a boy and the other a girl. [65] A late Babylonian bas-relief from Lajard's [66] collection seems to be in accordance with this view. In the middle of the image stands an androgynous god (masculine and feminine face [67]); upon the right, male side, is found a serpent, with a sun halo round its head; upon the left, female side, there is also a serpent, with the moon above its head. Above the head of the god there are three stars. This ensemble would seem to confirm the Trinity [68] of the representation. The Sun serpent at the right side is male; the serpent at the left side is female (signified by the moon). This image possesses a symbolic sexual suffix, which makes the sexual significance of the whole obtrusive. Upon the male side a rhomb is found -- a favorite symbol of the female genitals; upon the female side there is a wheel or felly. A wheel always refers to the Sun, but the spokes are thickened and enlarged at the ends, which suggests phallic symbolism. It seems to be a phallic wheel, which was not unknown in antiquity. There are obscene bas-reliefs where Cupid turns a wheel of nothing but phalli. [69] It is not only the serpent which suggests the phallic significance of the Sun; I quote one especially marked case, from an abundance of proof. In the antique collection at Verona I discovered a late Roman mystic inscription in which are the following representations:

[iv] from the phallic symbolism, the originality of which may well be uncontested. [64] The male genitals are the basis for this Trinity. It is an anatomical fact that one testicle is generally placed somewhat higher than the other, and it is also a very old, but, nevertheless, still surviving, superstition that one testicle generates a boy and the other a girl. [65] A late Babylonian bas-relief from Lajard's [66] collection seems to be in accordance with this view. In the middle of the image stands an androgynous god (masculine and feminine face [67]); upon the right, male side, is found a serpent, with a sun halo round its head; upon the left, female side, there is also a serpent, with the moon above its head. Above the head of the god there are three stars. This ensemble would seem to confirm the Trinity [68] of the representation. The Sun serpent at the right side is male; the serpent at the left side is female (signified by the moon). This image possesses a symbolic sexual suffix, which makes the sexual significance of the whole obtrusive. Upon the male side a rhomb is found -- a favorite symbol of the female genitals; upon the female side there is a wheel or felly. A wheel always refers to the Sun, but the spokes are thickened and enlarged at the ends, which suggests phallic symbolism. It seems to be a phallic wheel, which was not unknown in antiquity. There are obscene bas-reliefs where Cupid turns a wheel of nothing but phalli. [69] It is not only the serpent which suggests the phallic significance of the Sun; I quote one especially marked case, from an abundance of proof. In the antique collection at Verona I discovered a late Roman mystic inscription in which are the following representations:

--

--  .[i] From water comes life; [19] therefore, of the two gods which here interest us the most, Christ and Mithra, the latter was born beside a river, according to representations, while Christ experienced his new birth in the Jordan; moreover, he is born from the

.[i] From water comes life; [19] therefore, of the two gods which here interest us the most, Christ and Mithra, the latter was born beside a river, according to representations, while Christ experienced his new birth in the Jordan; moreover, he is born from the  , the "sempiterni fons amoris," the mother of God, who by the heathen-Christian legend was made a nymph of the Spring. The "Sprin" is also found in Mithracism. A Pannonian dedication reads, "Fonti perenni." An inscription in Apulia is dedicated to the "Fons Aeterni." In Persia, Ardvicura is the well of the water of life. Ardvicura-Anahita is a goddess of water and love (just as Aphrodite is born from foam). The neo-Persians designate the Planet Venus and a nubile girl by the name "Nahid." In the temples of Anaitis there existed prostitute Hierodules (harlots). In the Sakaeen (in honor of Anaitis) there, occurred ritual combats as in the festival of the Egyptian Ares and his mother. In the Vedas the waters are called Matritamah -- the most maternal. [20] All that is living rises as does the sun, from the water, and at evening plunges into the water. Born from the springs, the rivers, the seas, at death man arrives at the waters of the Styx in order to enter upon the "night journey on the sea." The wish is that the black water of death might be the water of life; that death, with its cold embrace, might be the mother's womb, just as the sea devours the sun, but brings it forth again out of the maternal womb (Jonah motive [21]). Life believes not in death.

, the "sempiterni fons amoris," the mother of God, who by the heathen-Christian legend was made a nymph of the Spring. The "Sprin" is also found in Mithracism. A Pannonian dedication reads, "Fonti perenni." An inscription in Apulia is dedicated to the "Fons Aeterni." In Persia, Ardvicura is the well of the water of life. Ardvicura-Anahita is a goddess of water and love (just as Aphrodite is born from foam). The neo-Persians designate the Planet Venus and a nubile girl by the name "Nahid." In the temples of Anaitis there existed prostitute Hierodules (harlots). In the Sakaeen (in honor of Anaitis) there, occurred ritual combats as in the festival of the Egyptian Ares and his mother. In the Vedas the waters are called Matritamah -- the most maternal. [20] All that is living rises as does the sun, from the water, and at evening plunges into the water. Born from the springs, the rivers, the seas, at death man arrives at the waters of the Styx in order to enter upon the "night journey on the sea." The wish is that the black water of death might be the water of life; that death, with its cold embrace, might be the mother's womb, just as the sea devours the sun, but brings it forth again out of the maternal womb (Jonah motive [21]). Life believes not in death. , the wood of life, or the tree of life, is a maternal symbol would seem to follow from the previous deductions. The etymologic connection of

, the wood of life, or the tree of life, is a maternal symbol would seem to follow from the previous deductions. The etymologic connection of  ,

,  , in the Indo-Germanic root suggests the blending of the meanings in the underlying symbolism of mother and of generation. The tree of life is probably, first of all, a fruit-bearing genealogical tree, that is, a mother-image. Countless myths prove the derivation of man from trees; many myths show how the hero is enclosed in the maternal tree -- thus dead Osiris in the column, Adonis in the myrtle, etc. Numerous female divinities were worshipped as trees, from which resulted the cult of the holy groves and trees. It is of transparent significance when Attis castrates himself under a pine tree, i.e. he does it because of the mother. Goddesses were often worshipped in the form of a tree or of a wood. Thus Juno of Thespiae was a branch of a tree, Juno of Samos was a board. Juno of Argos was a column. The Carian Diana was an uncut piece of wood. Athene of Lindus was a polished column. Tertullian calls Ceres of Pharos "rudis palus et informe lignum sine effigie." Athenaeus remarks of Latona at Dalos that she is

, in the Indo-Germanic root suggests the blending of the meanings in the underlying symbolism of mother and of generation. The tree of life is probably, first of all, a fruit-bearing genealogical tree, that is, a mother-image. Countless myths prove the derivation of man from trees; many myths show how the hero is enclosed in the maternal tree -- thus dead Osiris in the column, Adonis in the myrtle, etc. Numerous female divinities were worshipped as trees, from which resulted the cult of the holy groves and trees. It is of transparent significance when Attis castrates himself under a pine tree, i.e. he does it because of the mother. Goddesses were often worshipped in the form of a tree or of a wood. Thus Juno of Thespiae was a branch of a tree, Juno of Samos was a board. Juno of Argos was a column. The Carian Diana was an uncut piece of wood. Athene of Lindus was a polished column. Tertullian calls Ceres of Pharos "rudis palus et informe lignum sine effigie." Athenaeus remarks of Latona at Dalos that she is  , a shapeless piece of wood. [22] Tertullian calls an Attic Pallas "crucis stipes," a wooden pale or mast. The wooden pale is phallic, as the name suggests,

, a shapeless piece of wood. [22] Tertullian calls an Attic Pallas "crucis stipes," a wooden pale or mast. The wooden pale is phallic, as the name suggests,  , Pallus. The

, Pallus. The  is a pale, a ceremonial lingam carved out of figwood, as are all Roman statues of Priapus.

is a pale, a ceremonial lingam carved out of figwood, as are all Roman statues of Priapus.  means a projection or centrepiece on the helmet, later called

means a projection or centrepiece on the helmet, later called  , just as

, just as

signifies baldheadedness on the forepart of the head, and

signifies baldheadedness on the forepart of the head, and  signifies baldheadedness in regard to the

signifies baldheadedness in regard to the  of the helmet; a semi-phallic meaning is given to the upper part of the head as well. [25]

of the helmet; a semi-phallic meaning is given to the upper part of the head as well. [25]  has, besides

has, besides  , the significance of "wooden"

, the significance of "wooden"  , "cylinder"

, "cylinder"  "a round beam." The Macedonian battle array, distinguished by its powerful impetus, is called

"a round beam." The Macedonian battle array, distinguished by its powerful impetus, is called  . or

. or  is a whale. Now

is a whale. Now  appears with the meaning "shining, brilliant." The Indo-Germanic root is bhale = to bulge, to swell. [25] Who does not think of Faust?

appears with the meaning "shining, brilliant." The Indo-Germanic root is bhale = to bulge, to swell. [25] Who does not think of Faust?

. ("and there shall be no more curse"). There shall be no more sins, no repression, no disharmony with one's self, no guilt, no fear of death and no pain of separation more!

. ("and there shall be no more curse"). There shall be no more sins, no repression, no disharmony with one's self, no guilt, no fear of death and no pain of separation more!

[ii] etc.

[ii] etc.