by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/7/20

-- Moving Against the Stream: The Birth of a new Buddhist Movement, by Sangharakshita [Dennis Lingwood]

-- Local Agency in Global Movements: Negotiating Forms of Buddhist Cosmopolitanism in the Young Men’s Buddhist Associations of Darjeeling and Kalimpong [YMBA], by Kalzang Dorjee Bhutia

-- Honour Thy Fathers: A Tribute to the Venerable Kapilavaddho ... And brief History of the Development of Theravāda Buddhism in the UK, by Terry Shine

-- The English Sangha Trust: History, by Amaravati.org

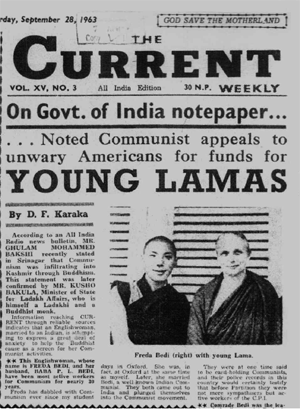

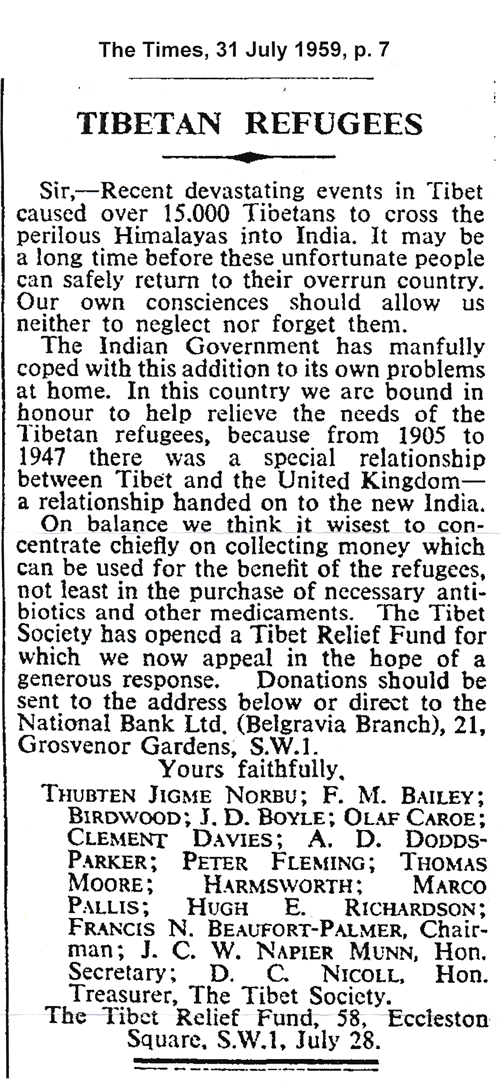

Alongside this noticeable success, Freda faced some acute disappointments. She made enemies as well as friends, and sometimes these rivalries became vicious. Lois Lang-Sims commented, without saying what prompted the observation, that Freda's enemies 'were not only numerous but of an almost incredible malevolence'. That intense animosity seems to have been behind the most wounding public assault on Freda and her integrity. The stiletto was wielded by D.F. [Dosabhai Framji] Karaka, an Oxford contemporary of the Bedis. He was a writer and journalist of some distinction, though by the early 1960s he was the editor of a not-so-distinguished Bombay-based tabloidstyle weekly, the Current. This was awash with brash, sensationalist stories, reflecting Karaka's fiercely polemical style, his crusading anticommunism and his impatience with Nehru, India's prime minister, for his supposed lack of zeal in standing up for the national interest. The weekly paper bore the slogan 'God Save the Motherland' on its front page.

The front page of 'Current' in September 1963 which caused Freda great distress.Saturday, September 28, 1963 GOD SAVE THE MOTHERLAND

THE CURRENT, VOL. XV, NO. 3 All India Edition 30 N.P. WEEKLY

On Govt. of India notepaper ...

... Noted Communist appeals to unwary Americans for funds for

YOUNG LAMAS

by D.F. Karaka

According to an All India Radio news bulletin, Mr. Ghulam Mohammed Bakshi recently stated in Srinagar that Communism was infiltrating into Kashmir through Buddhism. This statement was later confirmed by Mr. Kusho Bakula, Minister of State for Ladakh Affairs, who is himself a Ladakhi and a Buddhist monk.

Information reaching CURRENT through reliable sources indicates that an Englishwoman, married to an Indian, is attempting to express a great deal of anxiety to help the Buddhist cause as a screen for her Communist activities.

This Englishwoman, whose name is FREDA BEDI, and her husband, BABA P.L. BEDI, have been most active workers for Communism for nearly 30 years.

Freda has dabbled with Communism ever since my student days in Oxford. She was, in fact, at Oxford at the same time as myself. Later, she married Bedi, a well known Indian Communist. They both came out to India and plunged themselves into the Communist movement.

They were at one time said to be card-holding Communists, and their police records in this country would certainly testify that before Partition they were not mere sympathisers, but active workers of the C.P.I.

Comrade Bedi was the leader of the Communist Party in Lahore, where in pre-Independence ...

In September 1963, Freda's photograph graced the front-page of the Current, accompanying a story which also took up much of the following page. It was a hatchet job. Under his own byline, Karaka asserted that 'an Englishwoman, married to an Indian, is attempting to express a great deal of anxiety to help the Buddhist cause as a screen for her Communist activities'. He insisted that 'Mrs Freda Bedi ... will always, in my opinion, be a Communist first, irrespective of her outwardly embraced Buddhism.' This was an absurd accusation. Freda's days as a communist sympathiser had come to a close almost twenty years earlier. Her husband had abandoned communism a decade previously.By 1951, the thorny political issue of offering the people of Kashmir a plebiscite to let them decide whether they wanted to join Pakistan or accede to India hung heavily in the air. Freda was torn. While she believed in the people’s right to choose, she was adamantly against Pakistan’s propaganda, with its call for Islamic separation and the holocaust she feared would irrevocably follow, with Hindus and Sikhs the losers.

“There will be a tough fight when and if a plebiscite takes place. The other side uses low weapons – an appeal to religious fanaticism and hatred, which can always find a response. We fight with clean hands. I am content as a democrat that Kashmir should vote and turn whichever way it wishes, but I know a Pakistan victory would mean massacre and mass migration of Hindus and Sikhs – and I hate to face it. God forbid it should happen,” she said.

For the first time she revealed an anticommunist leaning. “I feel the British Press –- with the exception of our friend Norman Cliff on the News Chronicle -– is Pakistan minded, and while I realize that Pakistan and Middle East oil interests are linked, I think it is a great injustice to Kashmir. While a very brutal invasion and a lot of propaganda from the Pakistan side has been trying to make the state communist minded, it has valiantly stuck to his democratic ideas and built up this very war-torn, hungry world.”

BPL was valiantly doing his part in promoting counterpropaganda (a role given to him by Sheikh Abdullah’s administration), churning out publicity and articles both in Delhi and in Kashmir. One day in 1952, things went catastrophically wrong. BPL had a huge argument with his old friend Sheikh Abdullah, who was about to make a speech ratifying the plebiscite.

Kabir said, “My father warned him that India would never accept such a move and that Sheikh Abdullah would be jailed. He was also afraid that a plebiscite would deepen the split already existing in the state and would destroy the work that he, Mummy, and others had been carefully building up over the fragile early years to promote harmony and improve the living conditions of all the people. Kashmir had a huge Muslim majority, but anti-Pakistan feeling was also very high In Kashmir. That was what my father was working with, especially with his counterpropaganda. His ultimate commitment and hope was that Kashmir would be joined to secular India, with its democratic principles. Sadly the best of friendships ended in a bitter battle.”

The minute his argument with Sheikh Abdullah was over, BPL went home, packed up all his household goods and his family, and within twenty-four hours had moved everyone to Delhi. He could no longer stay in a Kashmir that he felt was heading for trouble, and in the employ of a man whose policies he no longer believed in. His prediction was right. In 1953, Sheikh Abdullah was dismissed as prime minister, arrested on charges of conspiracy against the state, and jailed for eleven years.

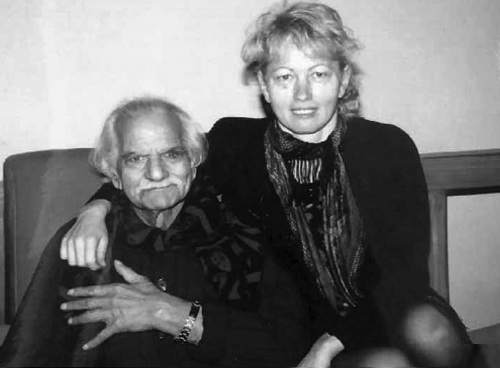

-- The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi, by Vicki Mackenzie[1954] As with Freda, Bedi's crisis had a lasting spiritual aspect. He developed a keen interest in the occult, establishing the Occult Circle of India; he became attracted to the mystical Sufi tradition within Islam and -- re-engaging with the religion he was born into -- in Sikh mysticism; he believed he had acquired special powers, and took to hands-on spiritual healing. He dressed in a smock and carried a staff; as his hair became increasingly unkempt, he looked like a latter-day Moses. He chose to be known as Baba, which carried with it an echo of a mystical or spiritual identity. It was a reinvention almost as complete as those that marked out the phases in Freda's life; he had gone from gilded youth, to communist and peasants' rights activist, to political apparatchik, to prophet and visionary. Bedi had largely broken links with the organised left and although he remained active in a Delhi-based Kashmir support group, he moved decisively away from active politics. 'I had been under an impulsion to take to spiritual life,' he recalled a decade later. 'I resigned at once from all organisations .... It was like a realization that now [the] time had come to quit all this work and take to a new form of life.' Bedi insisted... that his embrace of a spiritual purpose did not involve any repudiation of his socialist beliefs. 'The statue of Lenin I loved still lies on my mantelpiece, and not a dent on [my] Marxist convictions exists.' But several of his old associates felt uncomfortable with Bedi's new look and message and kept their distance. Ranbir Vohra, who had known the Bedis in Lahore and Srinagar as well as Delhi, recalled that his old friend offered to help him communicate with anyone who had passed on: 'He suggested that I talk to Marx. I declined the generous offer.'

-- The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi, by Andrew Whitehead

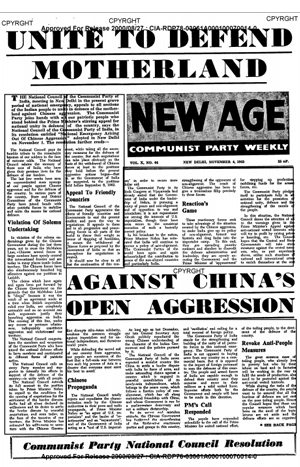

But the accusation of being a concealed communist was deeply wounding especially when the Tibetan refugees regarded communist China as their arch enemy -- the occupiers of their homeland and destroyers of their culture, faith and tradition -- and when India had recently been at war with China.The idea to write Red Shambhala developed gradually as a natural offshoot of my other projects... By chance, I found out that in a secret laboratory in the 1920s Gleb Bokii -- the chief Bolshevik cryptographer, master of codes, ciphers, electronic surveillance -- and his friend Alexander Barchenko, an occult writer from St. Petersburg, explored Kabala, Sufi wisdom, Kalachakra, shamanism, and other esoteric traditions, simultaneously preparing an expedition to Tibet to search for the legendary Shambhala. A natural question arose: what could the Bolshevik commissar have to do with all this? ...

Meanwhile, I learned that during the same years, on the other side of the ocean in New York City, the Russian emigre painter Nicholas Roerich and his wife, Helena, were planning a venture into Inner Asia, hoping to use the Shambhala prophecy to build a spiritual kingdom in Asia that would provide humankind with a blueprint of an ideal social commonwealth. To promote his spiritual scheme, he toyed with an idea to blend Tibetan Buddhism and Communism. Then I stumbled upon the German-Armenian historian Emanuel Sarkisyanz's Russland and der Messianismus des Orients, which mentioned that the same Shambhala legend was used by Bolshevik fellow travelers in Red Mongolia to anchor Communism among nomads in the early 1920s.

I came across this information when I was working on a paper dealing with the Oirot/Amursana prophecy that sprang up among Altaian nomads of southern Siberia at the turn of the twentieth century. This prophecy, also widespread in neighboring western Mongolia, dealt with the legendary hero some named Oirot and others called Amursana. The resurrected hero was expected to redeem suffering people from alien intrusions and lead them into a golden age of spiritual bliss and prosperity. This legend sounded strikingly similar to the Shambhala prophecy that stirred the minds of Tibetans and the nomads of eastern Mongolia. In my research I also found that the Bolsheviks used the Oirot/Amursana prophecy in the 1920s to anchor themselves in Inner Asia. I began to have a feeling that all the individuals and events mentioned above might have somehow been linked...

Shambhala... was a prophecy that emerged in the world of Tibetan Buddhism between the 900s and 1100s CE, centered on a legend about a pure and happy kingdom located somewhere in the north; the Tibetan word Shambhala means "source of happiness." The legend said that in this mystical land people enjoyed spiritual bliss, security, and prosperity. Having mastered special techniques, they turned themselves into godlike beings and exercised full control over forces of nature. They were blessed with long lives, never argued, and lived in harmony as brothers and sisters. At one point, as the story went, alien intruders would corrupt and undermine the faith of Buddha. That was when Rudra Chakrin (Rudra with a Wheel), the last king of Shambhala, would step in and in a great battle would crush the forces of evil. After this, the true faith, Tibetan Buddhism, would prevail and spread all over the world....

In the course of time, indigenous lamas and later Western spiritual seekers muted the "crusade" notions of the prophecy, and Shambhala became the peaceable kingdom that could be reached through spiritual enlightenment and perfection. The famous founder of Theosophy Helena Blavatsky was the first to introduce this cleansed version of the legend into Western esoteric lore in the 1880s. At the same time, she draped Shambhala in the mantle of evolutionary theory and progress: ideas widely popular among her contemporaries. Blavatsky's Shambhala was the abode of the Great White Brotherhood hidden in the Himalayas. The mahatmas from this brotherhood worked to engineer the so-called sixth race of spiritually enlightened and perfect human beings, who possessed superior knowledge and would eventually take over the world. After 1945, when this kind of talk naturally went out of fashion, the legend was refurbished to fit new spiritual needs. Today in Tibetan Buddhism and spiritual literature, in both the East and the West, Shambhala is presented as an ideal spiritual state seekers should aspire to reach by practicing compassion, meditation, and high spirituality. In this most recent interpretation of the legend, the old "holy war" feature is not simply set aside but recast into an inner war against internal demons that block a seeker's movement toward perfection....Lama Phuntsok was one of the dozens of lamas we had met, or were going to meet, in our future. It was already starting to get boring; all these amazing, enlightened Tibetan lamas and their cookie-cutter teachings we had access to, for free, because of our circumstances taking care of Trungpa's son. Although I wouldn't admit it, these lamas were all starting to sound the same and quite dull to me. This old lama from Tibet was different, however, being straight from the old country; unskilled in the strategic charms the lamas had learned for western audiences.

Phuntsok, we were told, was the incarnation of every great lama of the past, which was always the case for any new lamas who needed the boost, and this one seemed incoherent and all over the place. But, one thing was for sure, he was teaching us the real Kalachakra prophecy and its inner and secret teachings; how Trungpa's Shambhala legacy was embedded within it. It was not the Camelot Kingdom terma of Trungpa, nor the Shangri-la paradise of Saint Dalai Lama, filled with peace, love, and harmony, that we had come to believe.

This Kalachakra prophecy, the real one, we had never heard about before. Not in this direct and non-evasive way.

The Dalai Lama had finished giving his fourth, U.S. Kalachakra Wheel of Time empowerment in 1991, in New York City, to crowds of unsuspecting thousands, with the usual pitch that it was about bringing peace throughout the world. This Kalachakra prophecy, the real one, straight from this Lama Phuntsok's mouth, straight from Tibet, wasn't talking peace. He was talking about a third world war, the idea of which he seemed to relish, when Tantric Lord Chakravartins, as Rigden Kings, like Trungpa, would come to rule the world.

Lama Phuntsok told us we were the "special" Trungpa students of the "Shambhala Kingdom" and that Trungpa was a lama, who was not just a great bodhisattva, but a great military leader, connected to Gesar of Ling; an emanation of Rigden Kings who would come to rule the earth, in the near future. We were the future army of Shambhala warriors. Nothing new here; the usual teaching by Trungpa and his early students, but told were simply symbolic. We, as his students in this life, and part of his military branch, his kasung, were going to be reborn in the pure land of Shambhala. Yes, that was the same, but then Phuntsok continued: 'when you will come back to fight as Shambhala warriors, some of you as generals, in this great Wheel of Time war between heretics and Shambhala.'

When this war ended, he told us, it would usher in the Age of Maitreya, the Adi-Buddha world of Shambhala and its enlightened society, after this future great apocalyptic war, predicted by these lamas and their ancient prophesies, had destroyed the enemies of their 'dharma.' It was starting to sound like being reborn as kamikaze in a great, epic bloody battle. Not something you would wish for, for any of your next lives, as Lama Phuntsok was describing it. I just flinched, and filed it away.

What remained clear, however, was this great coming war was very real to this old lama from Tibet, and not symbolic at all; not an internal fight, or struggle within us, to tame our own demons -- our egoistic propensities, -- as we had been taught.

It was the first red flag, waving madly before my eyes, about why these lamas are building all their centers and temples, around the world. I realized, that they really believe they will rise up, at the end of this apocalypse they are all predicting; as the new Lord Chakravartins, the Rigden God Kings, ruling over the earth.

Lama Phuntsok, unskilled in donning a 'peaceful' mask for western consumption, had just told us that Tibetan Buddhism is an apocalyptic cult, that believes it will be the world religion in the not too distant future; once it has conquered the other heretic religions. The lamas had been telling us the same thing; but always making sure it was seen as just a metaphor; in a twilight language; about the war inside us, caused by that bug-a-boo: ego. Lama Phuntsok, straight from Tibet, and therefore straight from the thirteenth century, was telling us the truth about his Tibetan Buddhism; this religion of peace.

In a few short years, in Digby, Nova Scotia, at my last graduate Shambhala retreat -- Trungpa's Kalapa Assembly -- I would learn that Trungpa's ambitions to rule the world were as real for him as it was for Lama Phuntsok, transmitting the prophecy of Shambhala before me, now. Clearly, all these lamas believed and wished for the same thing.

-- Enthralled: The Guru Cult of Tibetan Buddhism, by Christine A. Chandler, M.A., C.A.G.S.

Red Shambhala is the first book in English that recounts the story of political and spiritual seekers from the West and the East, who used Tibetan Buddhist prophecies to promote their spiritual, social, and geopolitical agendas and schemes. These were people of different persuasions and backgrounds: lamas (Ja-Lama and Agvan Dorzhiev), a painter-Theosophist (Nicholas Roerich), a Bolshevik secret police cryptographer (Gleb Bokii), an occult writer with leftist leanings (Alexander Barchenko), Bolshevik diplomats and revolutionaries (Georgy Chicherin, Boris Shumatsky) along with their indigenous fellow-travelers (Elbek-Dorji Rinchino, Sergei Borisov, and Choibalsan), and the rightwing fanatic "Bloody White Baron" Roman von Ungern-Sternberg. Despite their different backgrounds and loyalties, they shared the same totalitarian temptation -- the faith in ultimate solutions. They were on the quest for what one of them (Bokii) defined as the search for the source of absolute good and absolute evil. All of them were true believers, idealists who dreamed about engineering a perfect free-of-social-vice society based on collective living and controlled by enlightened spiritual or ideological masters (an emperor, the Bolshevik Party, the Great White Brotherhood, a reincarnated deity) who would guide people on the "correct" path. Healthy skepticism and moderation, rare commodities at that time anyway, never visited the minds of the individuals I profile in this book. In this sense, they were true children of their time -- an age of extremes that gave birth to totalitarian society.

-- Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia, by Andrei Znamenski

'Freda has dabbled with Communism ever since my student days in Oxford,' Karaka reported. 'She was, in fact, at Oxford at the same time as myself. Later, she married Bedi, a well known Indian Communist. They both came out to India and plunged themselves into the Communist movement.' The article resorted to innuendo, suggesting that 'the alleged indoctrination of Sheikh Abdulla [sic] was largely to be traced to his very close association with Freda Bedi'. It suggested that some former associates of the Bedis in Kashmir had 'mysteriously disappeared'. Freda was alleged to have been caught up in controversy about Buddhist property and funds before turning, 'with the active encouragement of Shri J. Nehru, the Prime Minister', to the running of the Young Lamas' Home School. The article suggested that Freda was getting money from the Indian government, and using government headed paper to appeal for funds from supporters in America and elsewhere. Karaka suggested that the Tibetan Friendship Group was a 'Communist stunt' and he alleged that 'noted Communists, with the usual "blessings" of Mr. Nehru, are using the excuse of helping Tibetan refugees and Buddhist monks for furthering the cause of Communism in strategic border areas.'

Aside from the venomous smears, the only evidence of inappropriate conduct that the article pointed to was her use of official notepaper to appeal for funds for her school and other Tibetan relief operations. It cited a letter of complaint, sent by an unnamed Buddhist organisation which clearly was antagonistic to Freda, stating that she had been using the headed paper of the Central Social Welfare Board which bore the Government of India's logo. A civil servant's response was also quoted: 'Mrs Bedi is not authorised to use Government of India stationery for correspondence in connection with the affairs of the "Young Lama's Home" or the "Tibetan Friendship Group". This has now been pointed out to Mrs. Bedi.'

Even if Freda has been using government headed paper to help raise money -- which those who worked with her say is perfectly possible -- it was hardly a major misdemeanour. But detractors were able to use this blemish to damage her reputation. She was, it seems, distraught at this vicious personal attack and took advice about whether to take legal action. She was advised, probably wisely, to do nothing, as any riposte would simply give further life to accusations so insubstantial that they would quickly fade away. 'The accusation was that Freda was a communist in nun's clothing -- not that Freda was a nun at that time,' recalls Cherry Armstrong. 'I remember her being particularly distressed and "beyond belief' when she believed she had identified the culprit. Freda was totally dumbfounded about it.'

Freda was convinced that another western convert to Buddhism, Sangharakshita (earlier Dennis Lingwood), was either behind the slur or was abetting it. They had much in common -- including a deep antipathy to each other. Lingwood encountered Theosophy and Buddhism as a teenager in England and was ordained before he was twenty by the Burmese monk U Titthila, who later helped Freda towards Buddhism. During the war, he served in the armed forces in South and South-east Asia and from 1950 spent about fourteen years based in Kalimpong in north-east India, where he was influenced by several leading Tibetan Buddhist teachers. In the small world of Indian Buddhism, the two English converts rubbed shoulders. More than sixty years later, Sangharakshita -- who established a Buddhist community in England -- recalls coming across Freda, then new to Buddhism, living at the Ashoka Vihar Buddhist centre outside Delhi. 'She was tall, thin, and intense and wore Indian dress. She had a very pale complexion, with light fair hair and very pale blue eyes. In other words, she looked very English! I also noticed, especially later on, that she was very much the Memsaheb ... During the time that I knew Freda she knew hardly anything about Buddhism, having never studied it seriously .... She had however developed what I called her "patter" about the Dalai Lama, compassion, and the poor dear little Tulkus. So far as I could see, Freda had no spiritual awareness or Enlightenment. She may, of course, have developed these later.' His view of the Young Lamas' Home School is also somewhat jaundiced -- 'some of [the tulkus] developed rather expensive tastes, such as for Rolex watches.'In 1989 he was awarded with the Nobel Peace Prize, he is the spiritual head of Tibetan Buddhism -– and he, himself is a self-confessed watch lover. The speech is of course by Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama. Granted, the ascetic monk is not the first name that comes to mind in connection with luxury watches. But the Dalai Lama has a weakness for mechanical watches and has been happy to disassemble and reassemble them for years. His personal collection consists of over 15 watches, about which, however, little is known....

However, three of his watches can be clearly seen in photos and we are able to identity them. In addition to a Patek Philippe pocket watch, given to him as a young boy from U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the monk also has two Rolex models whose origin is unknown.

His love of mechanical watches began very early: At the age of 6 or 7, the Dalai Lama received his first watch, from none other than the U.S. American President Franklin D. Roosevelt....Eric Wind identified the watch... in a Hodinkee article as a pocket watch with Ref. 658, of which only 15 were made between 1937 and 1950, a truly special gift!... Roosevelt did not hand over the gift personally. Two agents of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of today’s CIA, offered the watch along with a letter from the president. Brooke Dolan and his colleague Ilia [Ilya Andreyevich] Tolstoy, who was allegedly the grandson of the famous author Leo Tolstoy, strictly followed the protocol: visitors silently handed over their presents and received a so-called 'katha‘, a prayer shawl traditionally handed over. The two had a mission to find out more about the possibility of building a road from India to China, which was strategically important to the United States for supplying China during the war with Japan.

The Dalai Lama’s watch is a complex and rare specimen that displays the moon phases, date, day of the week and months. It aroused his enthusiasm for mechanical watches and watchmaking. A well-known photograph shows him working on watches....

If you are interested in mechanical watches, there is no way around a classic Rolex. The Dalai Lama owns two models that are well-known: A Rolesor Rolex Datejust made of gold and stainless steel with a Jubilee bracelet and a Rolex Day-Date, both presumably gifts. The latter is made of yellow gold and has a blue dial, as seen in some photographs. Some people say that they are a sign of proudness among a monk, but if you look at the meaning of the colours in Tibetan Buddhism, you will see a beautiful picture: blue stands for heaven and spiritual insights, yellow for earth and the experiences of the real world. Thus, the watch purely by chance reflects the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism.

-- The Dalai Lama and his [Rolex] watches, by Manuel Lütgens

Sangharakshita's recollection is that he and Freda 'got on quite well, even though I did not take her "Buddhism" very seriously' as they were both English and (in his view) of working-class origin. He was not impressed by her husband: 'he struck me as a bit of a humbug ... I was told (not by Freda) that he was then living with one of his cousins.' In his memoirs, he recycled one of the allegations that featured in Current, that an 'Englishwoman married to a well-known Indian communist' was trying to 'wrest' control of Ashoka Vihar outside Delhi from the Cambodian monk who had founded it. Decades later, he continues to recount this and other of the items on the Current charge sheet, describing Freda as 'a rather ruthless operator' while in Kashmir. He recalls the furore over the Current article, but says that he had no reason to believe that Freda was using the Lamas' School for a political purpose. Freda never tackled him over her suspicions, but he does not deny a tangential involvement. 'It is possible,' he concedes, 'that certain reservations about the Young Lamas' Home School eventually reached the ears of Current.'

The incident was a reflection of the intense rivalries within the Tibetan movement and its supporters. 'Strong personalities do seem to draw opposition by their very nature,' Cherry Armstrong comments, 'and there is a lot of personal politics amongst the Tibetan groups -- not all light and loveliness as one might like to think.'

-- The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi, by Andrew Whitehead

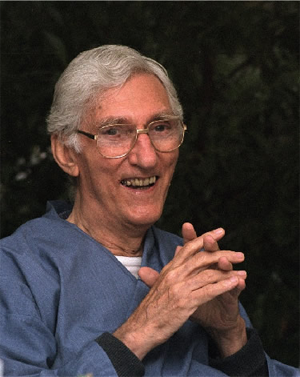

Sangharakshita

At the Western Buddhist Order men's ordination course, Guhyaloka, Spain, June 2002

Personal

Born: Dennis Philip Edward Lingwood, 26 August 1925, Tooting, London, England, U.K.

Died: 30 October 2018 (aged 93), Hereford, Herefordshire, England, U.K.

Religion: Buddhism

Nationality: British

Dharma names: Urgyen Sangharakshita

Occupation: Buddhist teacher, writer

Senior posting

Based in: Coddington, England, United Kingdom

Website: sangharakshita.org

Sangharakshita (born Dennis Philip Edward Lingwood, 26 August 1925 – 30 October 2018) was a British Buddhist teacher and writer. He was the founder of the Triratna Buddhist Community, which was known until 2010 as the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order, or FWBO.[1][2]

He was one of a handful of westerners to be ordained as Theravadin Bhikkhus in the period following World War II,[3] and spent over 20 years in Asia,[4] where he had a number of Tibetan Buddhist teachers.[5] In India, he was active in the conversion movement of Dalits—so-called "Untouchables"—initiated in 1956 by B. R. Ambedkar.[4] He authored more than 60 books, including compilations of his talks, and was described as "one of the most prolific and influential Buddhists of our era,"[6] "a skilled innovator in his efforts to translate Buddhism to the West,"[7] and as "the founding father of Western Buddhism"[8] for his role in setting up what is now the Triratna Buddhist Community,[9] but Sangharakshita was often regarded as a controversial teacher.[3] He was criticised for having had sexual relations with Order members,[10] which allegedly amounted to abuse and coercion.[11]

Sangharakshita retired formally in 1995 and in 2000 stepped down from the movement's ostensive leadership, but he remained its dominant figure and lived at its headquarters in Coddington, Herefordshire.[12]

The Triratna Order Office announced the death of Sangharakshita after a short illness on 30 October 2018.[13][14]

Early life

Sangharakshita was born Dennis Philip Edward Lingwood in Tooting, London, in 1925.[15] After being diagnosed with a heart condition he spent much of his childhood confined to bed, and used the opportunity to read widely.[16] His first encounter with non-Christian thought was with Madame Helena Blavatsky's Isis Unveiled,[17] upon reading which, he later said, he realised that he had never been a Christian.[18] The following year he came across two Buddhist texts—the Diamond Sutra and the Platform Sutra—and concluded that he had always been a Buddhist.[18]

As Dennis Lingwood, he joined the Buddhist Society at the age of 18,[19] and formally became a Buddhist in May 1944 by taking the Three Refuges and Five Precepts from the Burmese monk, U Thittila.[16]

He was conscripted into the army in 1943, and served in India, Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon) and Singapore as a radio engineer[20] in the Royal Corps of Signals.[21] It was in Sri Lanka, while in contact with the swamis in the (Hindu) Ramakrishna Mission, that he developed the desire to become a monk.[22] In 1946, after the cessation of hostilities, he was transferred to Singapore, where he made contact with Buddhists and learned to meditate.[23]

India

Having been conscripted into the British Army and posted to India, at the end of the war Sangharakshita handed in his rifle, left the camp where he was stationed and deserted.[23] He moved about in India for a few years, with a Bengali novice Buddhist, the future Buddharakshita, as his companion, meditating and experiencing for himself the company of eminent spiritual personalities of the times, like Mata Anandamayi, Ramana Maharishi and Swamis of Ramakrishna Mission. They spent fifteen months in 1947-48, in the Ramakrishna Mission centre at Muvattupuzha with the consent of Swami Tapasyananda and Swami Agamananda. In May 1949 he became a novice monk, or sramanera, in a ceremony conducted by the Burmese monk, U Chandramani, who was then the most senior monk in India. It was then that he was given the name Sangharakshita (Pali: Sangharakkhita), which means "protected by the spiritual community."[23] Sangharakshita took full bhikkhu ordination the following year,[21] with another Burmese bhikkhu, U Kawinda, as his preceptor (upādhyāya), and with the Ven. Jagdish Kashyap as his teacher (ācārya).[23] He studied Pali, Abhidhamma, and Logic with Jagdish Kashyap at Benares (Varanasi) University.[19] In 1950, at Kashyap's suggestion, Sangharakshita moved to the hill town of Kalimpong[17] close to the borders of India, Bhutan, Nepal. and Sikkim, and only a few miles from Tibet. Kalimpong was his base for 14 years until his return to England in 1966.[20]

During his time in Kalimpong, Sangharakshita formed a young men's Buddhist association and established an ecumenical centre for the practice of Buddhism (the Triyana Vardhana Vihara).[20] He also edited the Maha Bodhi Journal and established a magazine, Stepping Stones.[24] In 1951, Sangharakshita met the German-born Lama Govinda, who was the first Buddhist Sangharakshita had known "to declare openly the compatibility of art with the spiritual life", and who gave Sangharakshita a greater appreciation for Tibetan Buddhism.[25] Govinda had begun his explorations of Buddhism in the Theravada tradition, studying briefly under the German-born bhikkhu, Nyanatiloka Mahathera (who gave him the name Govinda), but after meeting the Gelug Lama, Tomo Geshe Rinpoche, in 1931, he turned towards Tibetan Buddhism.[26] Sangharakshita's spiritual explorations were to follow a similar trajectory.

Sangharakshita was ordained in the Theravada school, but said he became disillusioned by what he felt was the dogmatism, formalism, and nationalism of many of the Theravadin bhikkhus he met[5] and became increasingly influenced by Tibetan Buddhist teachers who had fled Tibet after the Chinese invasion in the 1950s. Two years after his meeting with Lama Govinda he began studying with the Gelug Lama, Dhardo Rinpoche.[5] Sangharakshita also received initiations and teachings from teachers who included Jamyang Khyentse, Dudjom Rinpoche, as well as Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche.[5] It was Dhardo Rinpoche who was to give Sangharakshita Mayahana ordination.[19] Later, Sangharakshita also studied with a Ch'an teacher, Yogi Chen (Chen Chien-Ming), along with another English monk, Bhikkhu Khantipalo.[27] Together, the three men turned their ongoing seminar on Buddhist theory and practice into a book, Buddhist Meditation, Systematic and Practical.[28]

In 1952, Sangharakshita met Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar[29] (1891–1956), the chief architect of the Indian constitution and India's first law minister. Ambedkar, who had been a so-called Untouchable, converted to Buddhism, along with 380,000 other Untouchables (now known as "dalits") on 14 October 1956.[30] Ambedkar and Sangharakshita had been in correspondence since 1950, and the Indian politician had encouraged the young monk to expand his Buddhist activities.[31] Ambedkar appreciated Sangharakshita's "commitment to a more critically engaged Buddhism that did not at the same time dilute the cardinal precepts of Buddhist thought".[32] Ambedkar initially invited Sangharakshita to perform his conversion ceremony, but the latter refused, arguing that U Chandramani should preside.[32] Ambedkar died six weeks later, leaving his conversion movement leaderless, and Sangharakshita, who had just arrived in Nagpur to visit dalit Buddhists,[32] continued what he felt was Ambedkar's work by lecturing to former Untouchables,[29] and presiding over a ceremony in which a further 200,000 Untouchables converted.[30] For the next decade, Sangharakshita spent much of his time visiting dalit Buddhist communities in western India.[33]

Return to the West

In 1964, Sangharakshita was invited to help with a dispute at the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara in north London,[34] where he proved to be a popular teacher.[15] His ecumenical approach and failure to conform to some of the trustees' expectations was said to contrast with the strict Theravadin-style Buddhism at the vihara.[15] Although originally planning to stay only six months, he decided to settle in England, but after he returned to India for a farewell tour, the Vihara's trustees voted to expel him.[15]

Sangharakshita returned to England and in April 1967 founded the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order.[15] The Western Buddhist Order was founded a year later, when he ordained the first dozen men and women. The first ordinations were attended by a Zen monk, a Shin priest and two Theravadin monks.[35]

Satisfied neither with the lay-Buddhist approach of the Buddhist Society, nor the monastic approach of the Hampstead vihara—the two dominant Buddhist organisations in Britain at that time—he created what he said was a new form of Buddhism. The order would be neither lay nor monastic,[36] and members take a set of ten precepts[35] that are a traditional part of Mahayana Buddhism.[37]

Initially, Sangharakshita led all classes and conducted all ordinations.[35] He gave lectures drawing on what he felt were the essential teachings of all the major Buddhist schools.[34] He led major retreats twice a year and frequent day and weekend events.[34] As the order grew, and centres became established across Britain and in other countries, order members took more responsibility until, in August 2000, he devolved his responsibilities as the head of the Western Buddhist Order to eight men and women who formed what was called the "College of Public Preceptors."[38] In 2005 Sangharakshita donated all of his books and artefacts, with an insurance value of £314,400, to the charitable trust dedicated to his 'support and assistance' as well as enabling his office to 'maintain contact with his disciples and friends worldwide' and to 'support them in activities'.[39] In 2015 this trust had an income of £140K, and for 2016 it was £73K.[40][41]

Sangharakshita died, aged 93, on 30 October 2018 after a short illness.[42]

Sexual misconduct

Main article: Triratna Buddhist Community

In 1997, Sangharakshita became the focus for controversy when The Guardian newspaper published complaints concerning some of his sexual relationships with FWBO members during the 1970s and 1980s.[43] For a decade following these public revelations, he declined to give any response to concerns from within the movement that he had misused his position as a Buddhist teacher to sexually exploit young men. He later addressed the controversy, stressing that his sexual partners were, or appeared to be, willing, and he expressed regret for any mistakes.[44]

Contributions and legacy

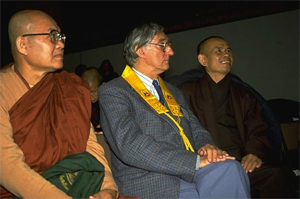

Ven. Rewata Dhamma, Sangharakshita and Thich Nhat Hanh at the European Buddhist Union Congress, Berlin, 1992

Sangharakshita has been described as "among the first Westerners who devoted their life to the practice as well as the spreading of Buddhism" and also as a "prolific writer, translator, and practitioner of Buddhism".[45] As a Westerner seeking to use Western concepts to communicate Buddhism, he has been compared to Teilhard de Chardin,[46] termed "the founding father of Western Buddhism,"[8] and noted as "a skilled innovator in his efforts to translate Buddhism to the West."[7]

For Sangharakshita, as with other Buddhists, the factor that unites all Buddhist schools is not any particular teaching, but the act of "going for refuge" (sarana-gamana), which he regards "not simply as a formula but as a life-changing event"[17] and as an ongoing "reorientation of one's life away from mundane concerns to the values embodied in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha."[47] Any decisive act upon the spiritual path—renunciation, ordination, initiation, the attainment of Stream Entry, and the arising of the bodhicitta—are manifestations or examples of Going for Refuge.[48]

Among his distinctive views is his use of the scientific theory of evolution as a metaphor for spiritual development, referring to biological evolution as the "lower evolution" and spiritual development as being a form of self-directed "higher evolution". Though he considers women and men equally capable of Enlightenment and ordained them equally right from the start, he has also said he had "tentatively reached the conclusion that the spiritual life is more difficult for women because they are less able than men to envisage...something purely transcendental..."[49] He also criticised heterosexual nuclear relationships as tending to neuroticism. The FWBO has been accused of cult-like behaviour in the 1970s and 80s for encouraging heterosexual men to engage in sexual relationships with men in order to get over their fear of intimacy with men and obtain spiritual growth.[48] He has drawn parallels between Buddhism and the spirit of the Romantics, who believed that what art reveals has great moral and spiritual significance, and has written of "the religion of art."[50]

Including compilations of his talks, Sangharakshita has authored more than 60 books. Meanwhile, the Triratna Buddhist Community, which he founded as the FWBO, has been described as "perhaps the most successful attempt to create an ecumenical international Buddhist organization".[51] The community is one of the three largest Buddhist movements in Britain,[52] and has a presence in Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa. More than a fifth of all Order members, as of 2006, were in India,[53] where Dr. Ambedkar's mission to convert dalits to Buddhism continues.[54] Martin Baumann, a scholar of Buddhism, has estimated that there are 100,000 people worldwide who are affiliated with the Triratna Buddhist Community.[54]

For Buddhologist Francis Brassard, Sangharakshita's major contribution is "without doubt his attempt to translate the ideas and practices of [Buddhism] into Western languages."[55] The non-denominational nature of the Triratna Buddhist Community,[35] its equal ordination for both men and women,[56] and its evolution of new forms of shared practice, such as what it calls team-based right livelihood projects, have been cited as examples of such "translation", and also as the creation of a "Buddhist society in miniature within the Western, industrialized world".[4] For Martin Baumann, the Triratna Buddhist Community serves as proof that "Western concepts, such as a capitalistic work ethos, ecological considerations, and a social-reformist perspective, can be integrated into the Buddhist tradition".[57]

Bibliography

Biography

• Anagarika Dharmapala: A Biographical Sketch

• Great Buddhists of the Twentieth Century

Books on Buddhism

• The Eternal Legacy: An Introduction to the Canonical Literature of Buddhism

• A Survey of Buddhism: Its Doctrines and Methods Through the Ages

• The Ten Pillars of Buddhism

• The Three Jewels: The Central Ideals of Buddhism

Edited seminars and lectures on Buddhism[edit]

• The Bodhisattva Ideal

• Buddha Mind

• The Buddha's Victory

• Buddhism for Today – and Tomorrow

• Creative Symbols of Tantric Buddhism

• The Drama of Cosmic Enlightenment

• The Essence of Zen

• A Guide to the Buddhist Path

• Human Enlightenment

• The Inconceivable Emancipation

• Know Your Mind

• Living with Awareness

• Living with Kindness

• The Meaning of Conversion in Buddhism

• New Currents in Western Buddhism

• Ritual and Devotion in Buddhism

• The Taste of Freedom

• The Yogi's Joy: Songs of Milarepa

• Tibetan Buddhism: An Introduction

• Transforming Self and World

• Vision and Transformation (also known as The Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path)

• Who Is the Buddha?

• What Is the Dharma?

• What Is the Sangha?

• Wisdom Beyond Words

Essays and papers

• Alternative Traditions

• Crossing the Stream

• Going For Refuge

• The Priceless Jewel

• Aspects of Buddhist Morality

• Dialogue between Buddhism and Christianity

• The Journey to Il Covento

• St Jerome Revisited

• Buddhism and Blasphemy

• Buddhism, World Peace, and Nuclear War

• The Bodhisattva Principle

• The Glory of the Literary World

• A Note on The Burial of Count Orgaz

• Criticism East and West

• Dharmapala: The Spiritual Dimension

• With Allen Ginsburg In Kalimpong (1962)

• Indian Buddhists

• Ambedkar and Buddhism

Memoirs, autobiography and letters

• Facing Mount Kanchenjunga: An English Buddhist in the Eastern Himalayas

• From Genesis to the Diamond Sutra: A Western Buddhist's Encounters with Christianity

• In the Sign of the Golden Wheel: Indian Memoirs of an English Buddhist

• Moving Against the Stream: The Birth of a New Buddhist Movement

• The Rainbow Road: From Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong

• The History of My Going for Refuge

• Precious Teachers

• Travel Letters

• Through Buddhist Eyes

Poetry and art

• The Call of the Forest and Other Poems

• Complete Poems 1941–1994

• Conquering New Worlds: Selected Poems

• Hercules and the Birds

• In the Realm of the Lotus

• The Religion of Art

Polemic

• Forty Three Years Ago: Reflections on My Bhikkhu Ordination

• The FWBO and 'Protestant Buddhism': An Affirmation and a Protest

• The Meaning of Orthodoxy in Buddhism

• Was the Buddha a Bhikkhu? A Rejoinder to a Reply to 'Forty Three Years Ago'.

Translation

• The Dhammapada

See also

• Dharmachari Subhuti - Senior associate of Sangharakshita

References

1. Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 333, ISBN 978-0-938077-69-5

2. George D. Chryssides; Margaret Z. Wilkins (2006). A Reader in New Religious Movements: Readings in the Study of New Religious. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0826461674.

3. Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 326, ISBN 978-0-938077-69-5

4. Baumann, Martin (May 1998), "Working in the Right Spirit: The Application of Buddhist Right Livelihood in the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order" (PDF), Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 5: 132.

5. Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 329, ISBN 978-0-938077-69-5

6. Smith, Huston; Novak, Philip (2004), Buddhism: A Concise Introduction, HarperCollins, p. 221, ISBN 978-0-06-073067-3

7. Doyle, Anita (Summer 1996), "Women, Men, and Angels (review)", Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, 5: 105

8. Berkwitz, Stephen C (2006), Buddhism in world cultures: comparative perspectives, ABC-CLIO, p. 303, ISBN 978-1-85109-782-1

9. Kay, David N (2004), Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain: transplantation, development and adaptation, Routledge, p. 25, ISBN 978-0-415-29765-3

10. Tsomo, Karma Lekshe (2000), Innovative Buddhist women: swimming against the stream, Routledge, p. 266, ISBN 978-0-7007-1253-3

11. Doward, Jamie (21 July 2019). "Buddhist, teacher, predator: dark secrets of the Triratna guru". The Observer. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

12. "Adhisthana". Triratna Buddhist Order. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

13. "Urgyen Sangharakshita 1925-2018".

14. Littlefair, Sam (30 October 2018). "Sangharakshita, founder of Triratna Buddhism, dead at 93". Lion's Roar. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

15. Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 46, ISBN 978-0-8264-6168-1

16. Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 47, ISBN 978-0-8264-6168-1

17. Lopez Jr, Donald S (2002), A Modern Buddhist Bible: Essential Readings from East and West, Beacon Press, p. 186, ISBN 978-0-8070-1243-7

18. Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 323, ISBN 978-0-938077-69-5

19. Snelling, John (1999), The Buddhist Handbook: A Complete Guide to Buddhist Schools, Teaching, Practice, and History, Inner Traditions, p. 230, ISBN 978-0-89281-761-0

20. Chryssides, George D. (1999), Exploring New Religions, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 225, ISBN 978-0-8264-5959-6

21. Prebish, Charles S. (1999), Luminous passage: the practice and study of Buddhism in America, University of California Press, p. 47, ISBN 978-0-520-21697-6

22. Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, pp. 47–48, ISBN 978-0-8264-6168-1

23. Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 48, ISBN 978-0-8264-6168-1

24. Oldmeadow, Harry (1999), Journeys East: 20th century Western encounters with Eastern religious traditions, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 280, ISBN 978-0-8264-5959-6

25. Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, pp. 328–329, ISBN 978-0-938077-69-5

26. Lopez, Donald (2002), A Modern Buddhist Bible: Essential Readings from East and West, Beacon Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-8070-1243-7

27. Khantipalo, Laurence (2002), Noble Friendship: Travels of a Buddhist Monk, Windhorse Publications, pp. 140–142, ISBN 978-1-899579-46-4

28. Chen, C.M. (1983), Buddhist Meditation, Systematic and Practical (Volume 42 of Hsientai fohsüeh tahsi), Mile ch'upanshe, p. xiii

29. Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 331, ISBN 978-0-938077-69-5

30. Chryssides, George D. (1999), Exploring New Religions, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 226, ISBN 978-0-8264-5959-6

31. Ganguly, debjani (2005), Caste, Colonialism, and Counter-Modernity: Notes on a Postcolonial Hermeneutics of Caste, Routledge, pp. 167–168, ISBN 978-0-415-34294-0

32. Ganguly, debjani (2005), Caste, Colonialism, and Counter-Modernity: Notes on a Postcolonial Hermeneutics of Caste, Routledge, p. 168, ISBN 978-0-415-34294-0

33. Ganguly, debjani (2005), Caste, Colonialism, and Counter-Modernity: Notes on a Postcolonial Hermeneutics of Caste, Routledge, p. 169, ISBN 978-0-415-34294-0

34. Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 49, ISBN 978-0-8264-6168-1

35. Rawlinson, Andrew (1997), The Book of Enlightened Masters, Open Court, p. 503, ISBN 978-0-8126-9310-2

36. Queen, Christopher S.; King, Sallie B. (1996), Engaged Buddhism, SUNY Press, p. 86, ISBN 978-0-7914-2844-3

37. Keown, Damien (2003), A Dictionary of Buddhism, Oxford University Press US, p. 70, ISBN 978-0-8126-9310-2

38. "Have Map, Can Unravel". Dharmalife.com. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

39. ADM of Triratna Buddhist Community (Uddiyana), 2015, Charity Commission for England and Wales. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

40. "Triratna Buddhist Community (Uddiyana)". Charity Commission for England and Wales. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

41. "Triratna Buddhist Community (Uddiyana)". Charity Commission for England and Wales. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

42. Triratna Buddhist Order Website. Sangharakshita Memorial Space. https://thebuddhistcentre.com/sangharak ... splay=team

43. Tsomo, Karma Lekshe (2000), Innovative Buddhist Women: Swimming Against the Stream, Routledge, pp. 266–267, ISBN 978-0-7007-1219-9

44. Vajragupta (2010), The Triratna Story: Behind the Scenes of a New Buddhist Movement, Windhorse, ISBN 978-1-899579-92-1

45. Brassard, Francis (2000), The Concept of Bodhicitta in Santideva's Bodhicaryavatara, SUNY Press, pp. 22–23, ISBN 978-0-7914-4575-4

46. Brassard, Francis (2000), The Concept of Bodhicitta in Santideva's Bodhicaryavatara, SUNY Press, p. 23, ISBN 978-0-7914-4575-4

47. Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 334, ISBN 978-0-938077-69-5

48. Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 335, ISBN 978-0-938077-69-5

49. Transforming Self and World, 1995, p117

50. McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford University Press US, p. 334, ISBN 978-0-19-518327-6

51. Oldmeadow, Harry L. (2004), Journeys East: 20th century Western encounters with Eastern religious traditions, World Wisdom, Inc, p. 280, ISBN 978-0-941532-57-0

52. Beckerlegge, Gwilym (2001), From Sacred Text to Internet, Ashgate, p. 147, ISBN 978-0-7546-0748-9

53. McAra, Sally (2007), Land of Beautiful Vision: Making a Buddhist Sacred Place in New Zealand, University of Hawaii Press, p. 18, ISBN 978-0-8248-2996-4

54. King, Sally B. (2005), Being Benevolence: The Social Ethics of Engaged Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, p. 79, ISBN 978-0-8248-2935-3

55. Brassard, Francis (2000), The Concept of Bodhicitta in Śāntideva's Bodhícaryāvatāra, SUNY Press, pp. 22–23, ISBN 978-0-7914-4575-4

56. McAra, Sally (2007), Land of Beautiful Vision: Making a Buddhist Sacred Place in New Zealand, University of Hawaii Press, p. 60, ISBN 978-0-8248-2996-4

57. Baumann, Martin (May 1998), "Working in the Right Spirit:The Application of Buddhist Right Livelihood in the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order", Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 5: 135.

External links

• Official website

• FWBO files

• Works by Sangharakshita at Project Gutenberg