Part 2 of 2

Influence of Achaemenid culture in the Indian subcontinent

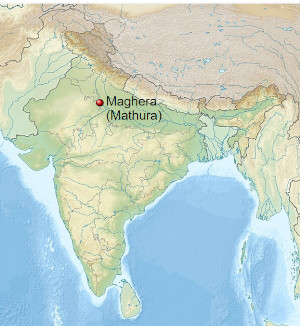

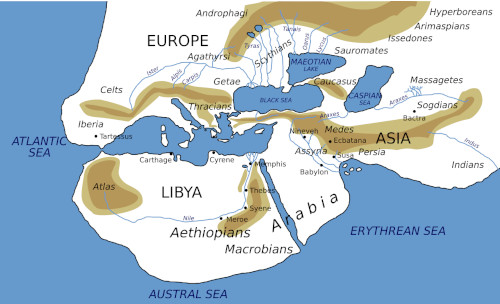

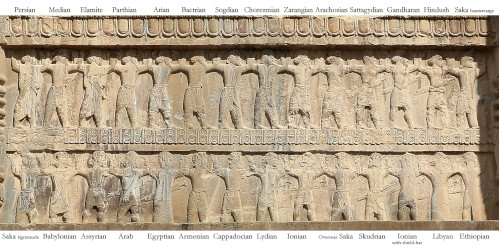

Cultural exchanges: Taxila Global location of Persepolis, capital of the Achaemenid Empire, and Taxila.

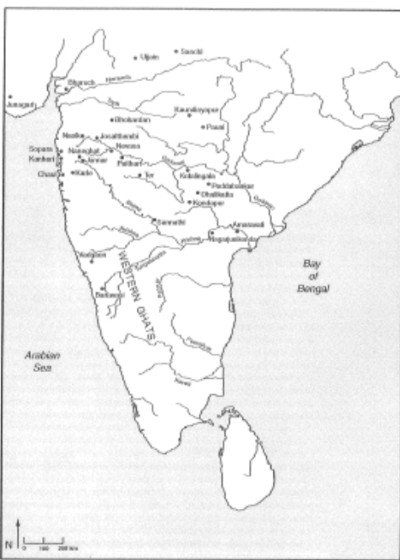

Global location of Persepolis, capital of the Achaemenid Empire, and Taxila. South Asia circa 500 BCE.[109][110]

South Asia circa 500 BCE.[109][110]Taxila (site of Bhir Mound), the "most plausible candidate for the capital of Achaemenid India",[16] was at the crossroad of the main trade roads of Asia, was probably populated by Persians, Greeks and other people from throughout the Achaemenid Empire.[111][112][113] As reported by Strabo (XV, 1, 62),[114] when Alexander the Great was in Taxila, one of his companions named Aristobulus, noticed that in the city the dead were being fed to the vultures, a clear allusion to the presence of Zoroastrianism.[115] The renowned University of Taxila became the greatest learning centre in the region, and allowed for exchanges between people from various cultures.[116]

Followers of the BuddhaSeveral contemporaries, and close followers, of the Buddha are said to have studied in Achaemenid Taxila: King Pasenadi of Kosala,[117] a close friend of the Buddha, Bandhula, the commander of Pasedani's army, Aṅgulimāla, a close follower of the Buddha, and Jivaka, court doctor at Rajagriha and personal doctor of the Buddha.[118][119] According to Stephen Batchelor, the Buddha may have been influenced by the experiences and knowledge acquired by some of his closest followers in Taxila.[120]

PāṇiniThe 5th century BCE grammarian Pāṇini lived in an Achaemenid environment.[121][122][123] He is said to have been born in the north-west, in Shalatula near Attock to the north-west of Taxila, in what was then a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, which technically made him a Persian subject.[121][122][123]

Kautilya and Chandragupta MauryaKautilya, the influential Prime Minister of Chandragupta Maurya, is also said to have been a professor teaching in Taxila.[124] According to Buddhist legend, Kautilya brought Chandragupta Maurya, the future founder of the Mauryan Empire to Taxila as a child, and had him educated there in "all the sciences and arts" of the period, including military sciences, for a period of 7 to 8 years.[125] These legends match Plutarch's assertion that Alexander the Great met with the young Chandragupta while campaigning in the Punjab.[125][126]

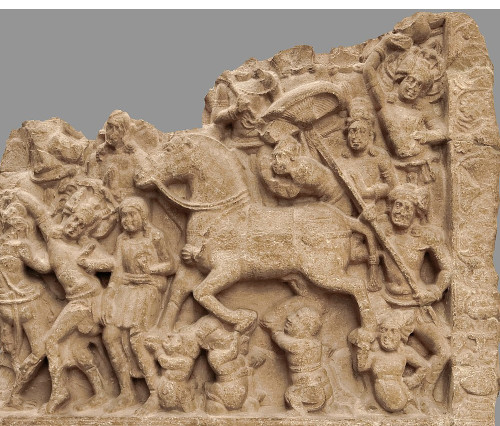

The Persians may have later participated, together with Sakas and Greeks, in the campaigns of Chandragupta Maurya to gain the throne of Magadha circa 320 BCE. The Mudrarakshasa states that after Alexander's death, an alliance of "Shaka-Yavana-Kamboja-Parasika-Bahlika" was used by Chandragupta Maurya in his campaign to take the throne in Magadha and found the Mauryan Empire.[127][128][129] The Sakas were Scythians, the Yavanas were Greeks, and the Parasikas were Persians.[128][130][127] David Brainard Spooner theorized upon Chandragupta Maurya's conquest and claimed that "it was with largely the Persian army that he won the throne of India."[129]

Scientific knowledgeAstronomical and astrological knowledge was also probably transmitted to India from Babylon during the 5th century BCE as a consequence of the Achaemenid presence in the sub-continent.[131][132] Babylonian astronomy was the first form of astronomy to fully develop and likely influenced other civilizations. The spread of knowledge may have hastened with the expansion of the Achaemenid Empire.

According to David Pingree, elements of Achaemenid scientific knowledge, particularly works on omens and astronomy, were adopted by India from the 5th century BCE:[133]

"India today is estimated to have about thirty million manuscripts, the largest body of handwritten reading material anywhere in the world. The literate culture of Indian science goes back to at least the fifth century B.C. ... as is shown by the elements of Mesopotamian omen literature and astronomy that entered India at that time."[133]

The outstanding feature of the oldest Indian education and Indian culture in general, especially in the centuries B.C., is its orality. The Vedic texts make no reference to writing, and there is no reliable indication that writing was known in India except perhaps in the northwestern provinces when these were under Achaemenid rule, since the time of Darius or even Cyrus. Those who write down the Veda go to hell, as the Mahabharata tells us, and Kumarila [700 A.D.] confirms: "That knowledge of the truth is worthless which has been acquired from the Veda, if the Veda has not been rightly comprehended or if it has been learnt from writing."2 Sayana [d. 1387] wrote in the introduction to his Rgveda commentary that "the text of the Veda is to be learned by the method of learning it from the lips of the teacher and not from a manuscript."3

The best evidence today is that no script was used or even known in India before 300 B.C., except in the extreme Northwest that was under Persian domination. That is in complete accord with the Indian tradition which at every occasion stresses the orality of the cultural and literary heritage....

There were no books; the common Indian word for "book" (pusta[ka]) is found not before the early centuries A.D. and is probably a loanword from Persian (post),25 and grantha denoted originally only "knot, nexus, text" acquiring the meaning "manuscript" much later.

The older Indian literature (including some texts as late as the early centuries A.D.) belongs to one of two classes: sruti "hearing" and smrti "remembering." It behooves us to pay attention to this distinction made by the Indians themselves early on.

-- Chapter Two: The Oral Tradition, From "Education in Ancient India", by Hartmut Scharfe

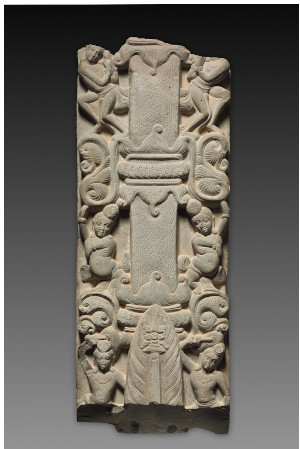

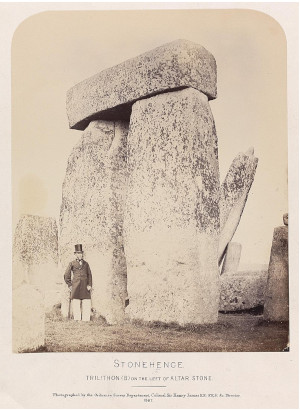

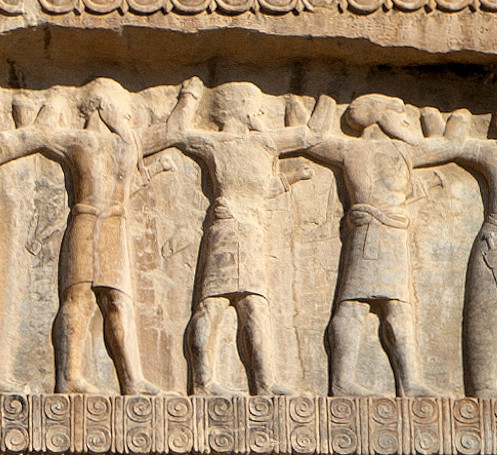

Palatial art and architecture: Pataliputra The Masarh lion. The sculptural style is "unquestionably Achaemenid".[134]

The Masarh lion. The sculptural style is "unquestionably Achaemenid".[134]Various Indian artefacts tend to suggest some Perso-Hellenistic artistic influence in India, mainly felt during the time of the Mauryan Empire.[1] The sculpture of the Masarh lion, found near the Maurya capital of Pataliputra, raises the question of the Achaemenid and Greek influence on the art of the Maurya Empire, and on the western origins of stone carving in India. The lion is carved in Chunar sandstone, like the Pillars of Ashoka, and its finish is polished, a feature of the Maurya sculpture.[134] According to S.P. Gupta, the sculptural style is unquestionably Achaemenid.[134] This is particularly the case for the well-ordered tubular representation of whiskers (vibrissas) and the geometrical representation of inflated veins flush with the entire face.[134] The mane, on the other hand, with tufts of hair represented in wavelets, is rather naturalistic.[134] Very similar examples are however known in Greece and Persepolis.[134] It is possible that this sculpture was made by an Achaemenid or Greek sculptor in India and either remained without effect, or was the Indian imitation of a Greek or Achaemenid model, somewhere between the fifth century B.C. and the first century B.C., although it is generally dated from the time of the Maurya Empire, around the 3rd century B.C.[134]

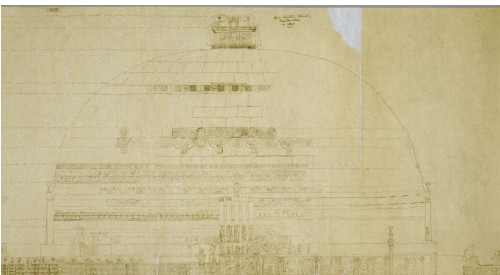

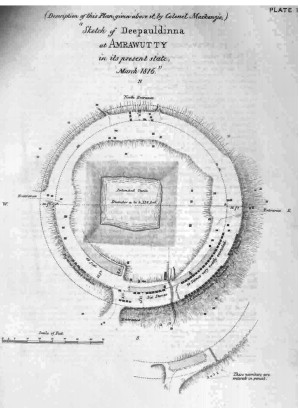

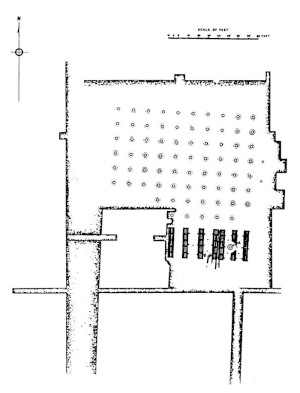

The Pataliputra palace with its pillared hall shows decorative influences of the Achaemenid palaces and Persepolis and may have used the help of foreign craftsmen.[135][1] Mauryan rulers may have even imported craftsmen from abroad to build royal monuments.[136] This may be the result of the formative influence of craftsmen employed from Persia following the disintegration of the Achaemenid Empire after the conquests of Alexander the Great.[137][138] The Pataliputra capital, or also the Hellenistic friezes of the Rampurva capitals, Sankissa, and the diamond throne of Bodh Gaya are other examples.[139]

The renowned Mauryan polish, especially used in the Pillars of Ashoka, may also have been a technique imported from the Achaemenid Empire.[1]

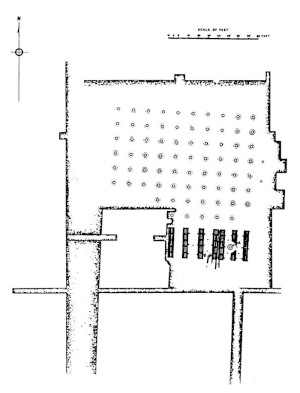

Ruins of pillared hall at Kumrahar site at Pataliputra.

Plan of the 80-column pillared hall in Pataliputra.

The Pataliputra capital, generally described as "Perso-Hellenistic".

Griffin of Pataliputra.[140]

Lotus motifs in Pataliputra.

Rock-cut architectureSee also: Buddhist caves in India

Lycian Tomb of Payava (dated 375-360 BCE)

Lycian Tomb of Payava (dated 375-360 BCE)  Lomas Rishi cave entrance (dated circa 250 BCE).

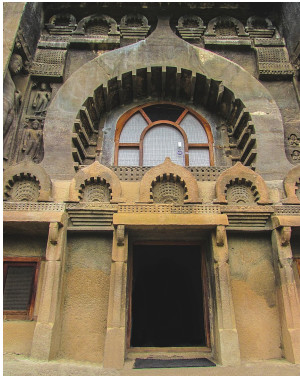

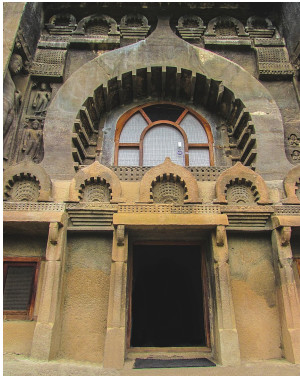

Lomas Rishi cave entrance (dated circa 250 BCE). Ajanta Cave 9 (dated 1st century BCE)

Ajanta Cave 9 (dated 1st century BCE)The similarity of the 4th century BCE Lycian barrel-vaulted tombs, such as the tomb of Payava, in the western part of the Achaemenid Empire, with the Indian architectural design of the Chaitya (starting at least a century later from circa 250 BCE, with the Lomas Rishi caves in the Barabar caves group), suggests that the designs of the Lycian rock-cut tombs travelled to India along the trade routes across the Achaemenid Empire.[141][142]

Early on, James Fergusson, in his Illustrated Handbook of Architecture, while describing the very progressive evolution from wooden architecture to stone architecture in various ancient civilizations, has commented that "In India, the form and construction of the older Buddhist temples resemble so singularly these examples in Lycia".[143] The structural similarities, down to many architectural details, with the Chaitya-type Indian Buddhist temple designs, such as the "same pointed form of roof, with a ridge", are further developed in The cave temples of India.[144] The Lycian tombs, dated to the 4th century BCE, are either free-standing or rock-cut barrel-vaulted sarcophagi, placed on a high base, with architectural features carved in stone to imitate wooden structures. There are numerous rock-cut equivalents to the free-standing structures and decorated with reliefs.[145][146][147] Fergusson went on to suggest an "Indian connection", and some form of cultural transfer across the Achaemenid Empire.[142] The ancient transfer of Lycian designs for rock-cut monuments to India is considered as "quite probable".[141]

Art historian David Napier has also proposed a reverse relationship, claiming that the Payava tomb was a descendant of an ancient South Asian style, and that Payava may actually have been a Graeco-Indian named "Pallava".[148]

Monumental columns: the Pillars of Ashoka Highly polished Achaemenid load-bearing column with lotus capital and animals, Persepolis, c. 5th-4th BCE.

Highly polished Achaemenid load-bearing column with lotus capital and animals, Persepolis, c. 5th-4th BCE. Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath.

Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath.See also: Pillars of Ashoka

Regarding the Pillars of Ashoka, there has been much discussion of the extent of influence from Achaemenid Persia,[149] since the column capitals supporting the roofs at Persepolis have similarities, and the "rather cold, hieratic style" of the Sarnath Lion Capital of Ashoka especially shows "obvious Achaemenid and Sargonid influence".[150]

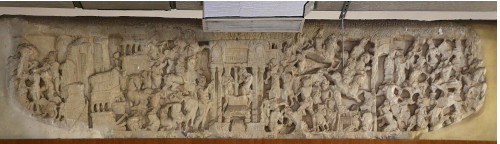

Hellenistic influence has also been suggested.[151] In particular the abaci of some of the pillars (especially the Rampurva bull, the Sankissa elephant and the Allahabad pillar capital) use bands of motifs, like the bead and reel pattern, the ovolo, the flame palmettes, lotuses, which likely originated from Greek and Near-Eastern arts.[152] Such examples can also be seen in the remains of the Mauryan capital city of Pataliputra.

Frieze of Rampurva capitals, alternating palmettes and lotus .

Frieze of Rampurva capitals, alternating palmettes and lotus . Frieze of Sankissa.

Frieze of Sankissa. Frieze of the diamond throne of Bodh Gaya.Aramaic language and script

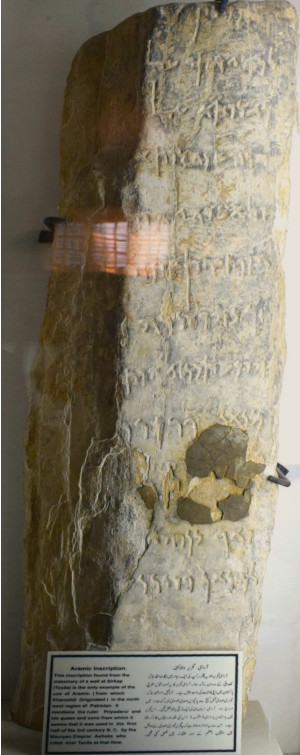

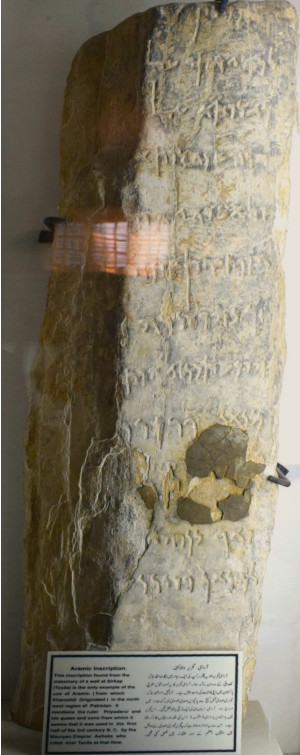

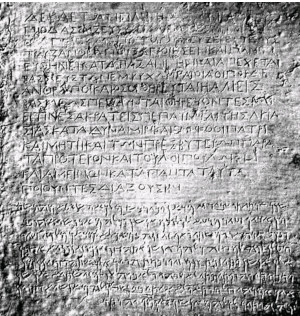

Frieze of the diamond throne of Bodh Gaya.Aramaic language and script The Aramaic Inscription of Taxila, dated circa 260 BCE. Taxila Museum, Pakistan.

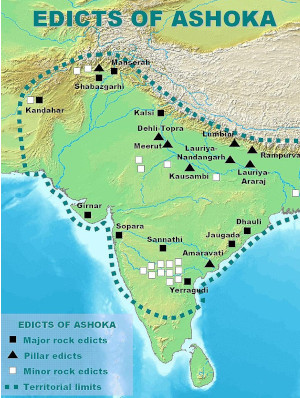

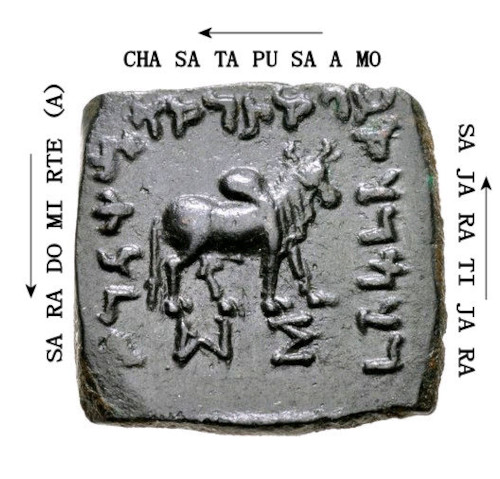

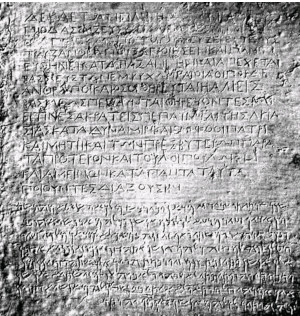

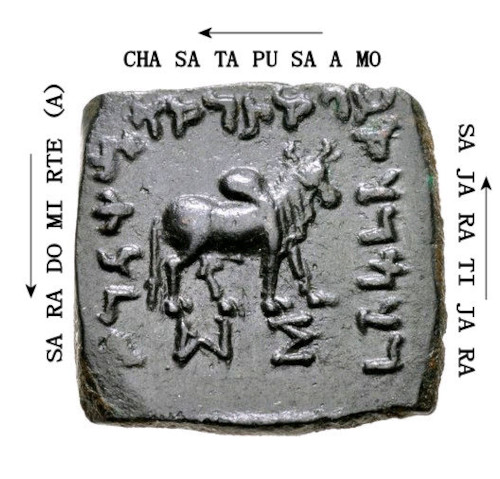

The Aramaic Inscription of Taxila, dated circa 260 BCE. Taxila Museum, Pakistan.The Aramaic language, official language of the Achaemenid Empire, started to be used in the Indian territories.[153] Some of the Edicts of Ashoka in the north-western areas of Ashoka's territory, in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan, used Aramaic (the official language of the former Achaemenid Empire), together with Prakrit and Greek (the language of the neighbouring Greco-Bactrian kingdom and the Greek communities in Ashoka's realm).[154]

The Indian Kharosthi script shows a clear dependency on the Aramaic alphabet but with extensive modifications to support the sounds found in Indic languages.[1][155] One model is that the Aramaic script arrived with the Achaemenid Empire's conquest of the Indus River (modern Pakistan) in 500 BCE and evolved over the next 200+ years, reaching its final form by the 3rd century BCE where it appears in some of the Edicts of Ashoka.[153][1]

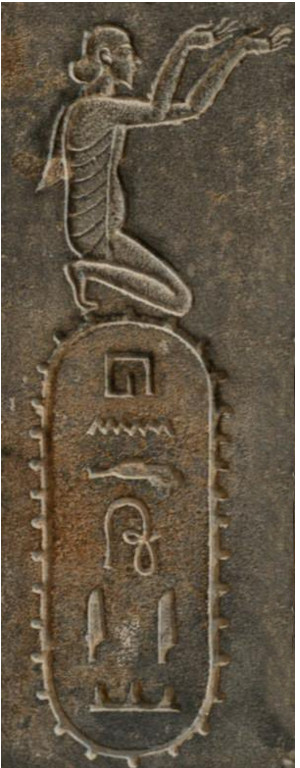

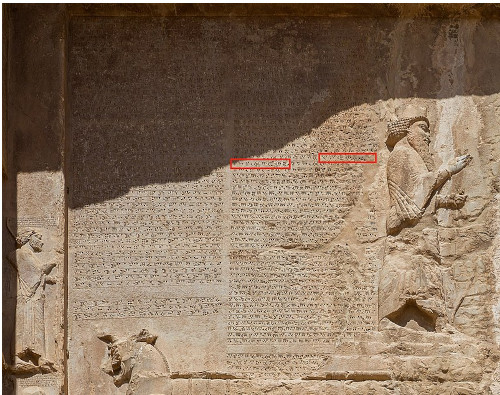

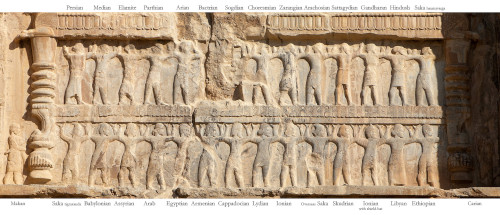

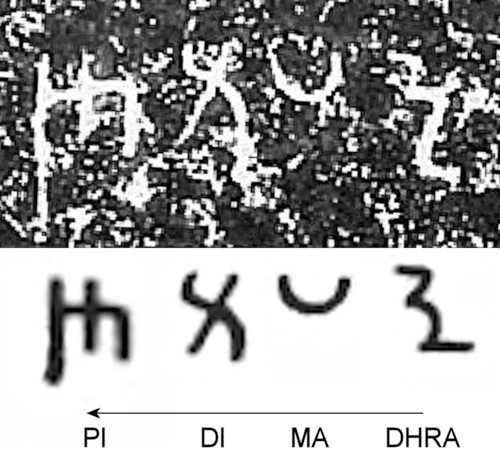

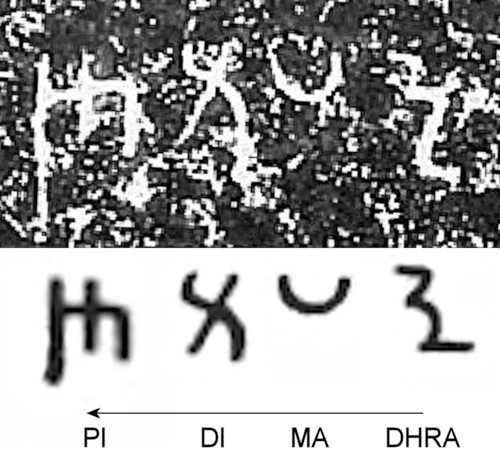

Edicts of AshokaThe Edicts of Ashoka (circa 250 BCE) may show Achaemenid influences, including formulaic parallels with Achaemenid inscriptions, presence of Iranian loanwords (in Aramaic inscriptions), and the very act of engraving edicts on rocks and mountains (compare for example Behistun inscription).[156][157] To describe his own edicts, Ashoka used the word Lipī ([x]), now generally simply translated as "writing" or "inscription". It is thought the word "lipi", which is also orthographed "dipi" ([x]) in the two Kharosthi versions of the rock edicts,[ b] comes from an Old Persian prototype dipî ([x]) also meaning "inscription", which is used for example by Darius I in his Behistun inscription,[c] suggesting borrowing and diffusion.[158][159][160] There are other borrowings of Old Persian terms for writing-related words in the Edicts of Ashoka, such as nipista or nipesita ([x], "written" and "made to be written") in the Kharoshthi version of Major Rock Edict No.4, which can be related to the word nipištā ([x], "written") from the daiva inscription of Xerxes at Persepolis.[161]

Several of the Edicts of Ashoka, such as the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription or the Taxila inscription were written in Aramaic, one of the official languages of the former Achaemenid Empire.[162]

The word Dipi ("Edict") in the Edicts of Ashoka, identical with the Achaemenid word for "writing".[163]

The word Dipi ("Edict") in the Edicts of Ashoka, identical with the Achaemenid word for "writing".[163] The Kharoshthi script is generally considered as a development from Aramaic.

The Kharoshthi script is generally considered as a development from Aramaic. The Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription of Ashoka (circa 256 BCE) in Greek and Aramaic.Figurines of West Asian foreigners in Mathura, Sarnath and Patna (4th-2nd century BCE)

The Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription of Ashoka (circa 256 BCE) in Greek and Aramaic.Figurines of West Asian foreigners in Mathura, Sarnath and Patna (4th-2nd century BCE)See also: Mathura art

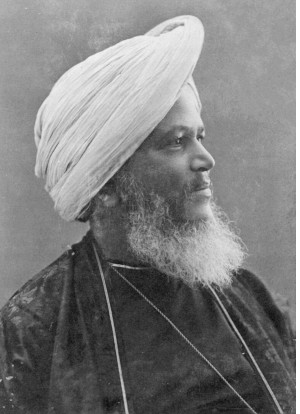

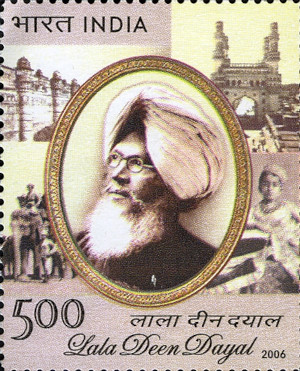

Figurines of foreigners in India "Ethnic head", Mathura, c. 2nd century BCE. Mathura Museum.[164]

"Ethnic head", Mathura, c. 2nd century BCE. Mathura Museum.[164] "Persian Nobleman clad in coat dupatta trouser and turban", Mathura, c. 2nd Century BCE. Mathura Museum.[164]

"Persian Nobleman clad in coat dupatta trouser and turban", Mathura, c. 2nd Century BCE. Mathura Museum.[164] Figure of a foreigner, from Sarnath.[165][166]

Figure of a foreigner, from Sarnath.[165][166]Some relatively high quality terracotta statuettes have been recovered from the Mauryan Empire strata in the excavations of Mathura in northern India.[167] Most of these terracottas show what appears to be female deities or mother goddesses.[168][169] However, several figures of foreigners also appear in the terracottas from the 4th to the 2nd century BCE, which are either described simply as "foreigners" or Persian or Iranian because of their foreign features.[164][170][171] These figurines might reflect the increased contacts of Indians with Iranian people during this period.[170] Several of these seem to represent foreign soldiers who visited India during the Mauryan period and influenced modellers in Mathura with their peculiar ethnic features and uniforms.[172] One of the terracotta statuettes, a man nicknamed the "Persian nobleman" and dated to the 2nd century BCE, can be seen wearing a coat, scarf, trousers and a turban.[173][174][175][164]

S.P. Gupta also mentions the "male heads of foreigners from Patna city and Sarnath", which according to him attest to the presence of a foreign elite in the Gangetic plains during the Mauryan or late Mauryan period. This elite was West Asian, specifically related to the Pahlavas and Sakas based in Iran and Afghanistan, and their presence was a consequence of their eastern forays into India.[165][166]

ReligionAccording to Ammianus Marcellinus,[176] a 4th-century CE Roman author, Hystaspes, the father of Darius I, studied under the Brahmanas in India, thus contributing to the development of the religion of the Magi (Zoroastrianism):[177]

"Hystaspes, a very wise monarch, the father of Darius. Who while boldly penetrating into the remoter districts of upper India, came to a certain woody retreat, of which with its tranquil silence the Brahmans, men of sublime genius, were the possessors. From their teaching he learnt the principles of the motion of the world and of the stars, and the pure rites of sacrifice, as far as he could; and of what he learnt he infused some portion into the minds of the Magi, which they have handed down by tradition to later ages, each instructing his own children, and adding to it their own system of divination".

— Ammianus Marcellinus, XXIII. 6.[178][177]

In ancient sources, Hystapes is sometimes considered as identical with Vishtaspa (the Avestan and Old Persian name for Hystapes), an early patron of Zoroaster.[177]

Historically, the life of the Buddha also coincided with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley.[179] The Achaemenid occupation of the areas of Gandara and Hinduš, which was to last for about two centuries, was accompanied by Achaemenid religions, reformed Mazdaism or early Zoroastrianism, to which Buddhism might also have in part reacted.[179] In particular, the ideas of the Buddha may have partly consisted in a rejection of the "absolutist" or "perfectionist" ideas contained in these Achaemenid religions.[179]

Still, according to Christopher I. Beckwith, commenting on the content of the Edicts of Ashoka, the early Buddhist concepts of karma, rebirth, and affirming that good deeds will be rewarded in this life and the next, in Heaven, probably find their origin in Achaemenid Mazdaism, which had been introduced in India from the time of the Achaemenid conquest of Gandara.[180]

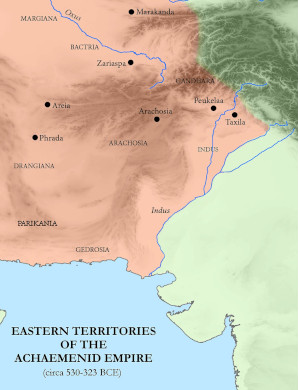

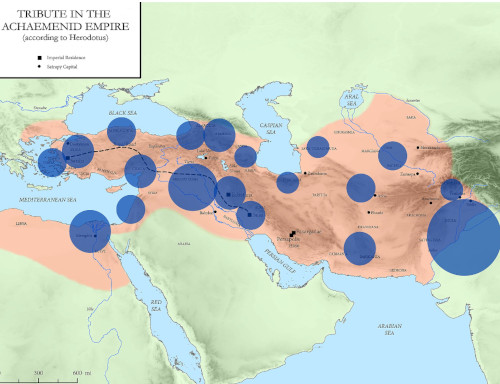

List of satrapiesSeveral satrapies were founded by the Achaemenid empire in the Indian subcontinent, including;

• Gandāra satrapy

• Hindush satrapy

• Sattagydia satrapy

Other important satrapies in South Asia (in modern day's Balochistan) include:

• Arachosia satrapy

• Gedrosia satrapy

• Drangiana satrapy

See also• Persian Immortals

Notes1. Ctesias: "The Indians also include this substance among their most precious gifts for the Persian king who receives it as a prize revered above all others."[59]

2. For example, according to Hultzsch, the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi (or at Mansehra) reads: "(Ayam) Dhrama-dipi Devanapriyasa Raño likhapitu" ("This Dharma-Edicts was written by King Devanampriya" Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 51.

This appears in the reading of Hultzsch's original rubbing of the Kharoshthi inscription of the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi.

3. For example Column IV, Line 89

References[edit]

1. Sen, Ancient Indian History and Civilization 1999, pp. 116–117.

2. Philip's Atlas of World History (1999)

3. O'Brien, Patrick Karl (2002). Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780195219210.

4. Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 15. ISBN 0226742210.

5. Errington, Elizabeth; Trust, Ancient India and Iran; Museum, Fitzwilliam (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ancient India and Iran Trust. p. 56. ISBN 9780951839911.

6. André-Salvini, Béatrice (2005). Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24731-4.

7. (Fussman, 1993, p. 84).[full citation needed] "This is inferred from the fact that Gandhara (OPers. Gandāra) is already mentioned at Bisotun, while the toponym Hinduš (Sindhu) is added only in later inscriptions."

8. Briant, Pierre (2002-07-21). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-1-57506-574-8.

9. Kerr, Gordon (2017). A Short History of India: From the Earliest Civilisations to Today's Economic Powerhouse (in German). Oldcastle Books. p. PT16. ISBN 9781843449232.

10. Thapar, Romila (1990). A History of India. Penguin UK. p. 422. ISBN 9780141949765.

11. Some sounds are omitted in the writing of Old Persian, and are shown with a raised letter.Old Persian p.164Old Persian p.13. In particular Old Persian nasals such as "n" were omitted in writing before consonants Old Persian p.17Old Persian p.25

12. Perfrancesco Callieri, INDIA ii. Historical Geography, Encyclopaedia Iranica, 15 December 2004.

13. Eggermont, Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan 1975, p. 177: "One should, therefore, be careful to distinguish the limited geographical unit of Gandhāra from the political one bearing the same name."

14. Tauqeer Ahmad, University of the Punjab, Lahore, South Asian Studies, A Research Journal of South Asian Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1, January–June 2012, pp. 221-232 p.222

15. FLEMING, DAVID (1993). "Where was Achaemenid India?". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 7: 67–72. JSTOR 24048427.

16. FLEMING, DAVID (1993). "Where was Achaemenid India?". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 7: 70. JSTOR 24048427.

17. Marshall, John (1975) [1951]. Taxila: Volume I. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 83.

18. Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. p. 82. ISBN 9781107009608.

19. DNa - Livius.

20. Hamadan Gold and Silver Tablet inscription

21. Dandamaev, A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire 1989, p. 147; Neelis, Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks 2010, pp. 96–97; Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 117. ISBN 9788122411980.

22. "The region was soon to appear as Hindūš in the Old Persian inscriptions... Transparent though the name appears at first sight, its location is not without problems. Foucher, Kent and many subsequent writers have identified Hindūš with its etymological equivalent , Sind, thereby placing it on the lower Indus towards the delta. However, (...) no material evidence of Achaemenid activity in this region is so far available. (...) There seems no evidence at present of gold production in the Indus delta, so this detail seems to weight against the location of the Hindūš province in Sind. (...) The alternative location to Sind for an Achaemenid province of Hindūš is naturally at Taxila and in the West Punjab, where there are indications that a Persian satrapy may have existed, though no clear evidence of its name." in Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. 2002. pp. 203–204. ISBN 9780521228046.

23. FLEMING, DAVID (1993). "Where was Achaemenid India?". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 7: 69. JSTOR 24048427.

24. Parker, Grant (2008). The Making of Roman India. Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780521858342.

25. Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire 1948, pp. 144–145.

26. Samad, Rafi U. (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-859-2.

27. Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9781400866328.

28. Herodotus VII 65

29. "INDIA RELATIONS: ACHAEMENID PERIOD – Encyclopaedia Iranica".

http://www.iranicaonline.org.

30. Behistun T 02 - Livius.

31. King, L. W. (Leonard William); Thompson, R. Campbell (Reginald Campbell) (1907). The sculptures and inscription of Darius the Great on the Rock of Behistûn in Persia : a new collation of the Persian, Susian and Babylonian texts. London : Longmans. p. 3.

32. Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 21. ISBN 9788172110284.

33. "Susa, Statue of Darius - Livius".

http://www.livius.org.

34. Also described here Archived 2019-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

35. Zournatzi, Antigoni (2003). "The Apadana Coin Hoards, Darius I, and the West". American Journal of Numismatics. 15: 1–28. JSTOR 43580364.

36. Persepolis : discovery and afterlife of a world wonder. 2012. pp. 171–181.

37. DPh inscription, also Photographs of one of the gold plaques Archived 2019-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

38. Livius DNa inscription

39. DSe - Livius.

40. DSm inscription

41. Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 20. ISBN 9788172110284.

42. "DNa - Livius".

http://www.livius.org.

43. Alcock, Susan E.; Alcock, John H. D'Arms Collegiate Professor of Classical Archaeology and Classics and Arthur F. Thurnau Professor Susan E.; D'Altroy, Terence N.; Morrison, Kathleen D.; Sinopoli, Carla M. (2001). Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History. Cambridge University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780521770200.

44. Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 756. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

45. "Strabo Geography, Book XV, Chapter 2, 9". penelope.uchicago.edu.

46. Barraclough, Geoffrey (1989). The Times Atlas of World History. Times Books. p. 79. ISBN 9780723009061.

47. Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire 1948, pp. 291–292: "The Gandarians thus make their last appearance as Persian tribute paying subjects in the lists of Artaxerxes, though the land continued to be known under the name of Gandhara down to classic Indian times."

48. Inscription A2Pa of Artaxerxes II

49. Lecoq, Pierre. Les inscriptions de la perse achemenide (1997) (in French). pp. 271–272.

50. Magee et al., The Achaemenid Empire in South Asia and Recent Excavations 2005, pp. 713–714.

51. Tola, Fernando (1986). "India and Greece before Alexander". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 67 (1/4): 159–194. JSTOR 41693244.

52. Samad, Rafi U. (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-859-2.

53. Samad, Rafi U. (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-859-2.

54. Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire 1948, pp. 291–292

55. Herodotus III 91, Herodotus III 94

56. Mitchiner, The Ancient & Classical World 1978, p. 44.

57. Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire 1948, pp. 291–292: "...the official tribute list incorporated by Herodotus shows decided administrative change. As under Cyrus, there were again twenty satrapies, but the larger number of Darius had been reduced by the union of some hitherto separate. This process, already to be detected in the army list of Xerxes, but accelerated in the tribute list of Artaxerxes, again suggests actual loss of territory. (25 lines later).... Two satrapies are united in the case of the Sattagydians, Gandarians, Dadicae, and Aparytae, whose tribute was 170 talents."

58. Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire 1948, pp. 291–292.

59. The Complete Fragments of Ctesias of Cnidus. pp. 120–121.

60. The Complete Fragments of Ctesias of Cnidus. p. Page 116 Fragment F45bα) and Page 219 Note F45bα).

61. The hypothesis that the region had already become independent by the end of the reign of Darius I or during the reign of Artaxerxes II (Chattopadhyaya, 1974, pp. 25-26) appears to be contradicted by Ctesias's reference to gifts received from the kings of India and by the fact that even Darius III still had some Indian units in his army (Briant, 1996, pp. 699, 774). At the time of the arrival of the Alexander's Macedonian army in the Indus Valley, there is no mention of officers of the Persian kings in India; but this does not mean (Dittmann, 1984, p. 185) that the Achaemenids had no power there. Other data indicate that they still exercised control over the area, although in ways that differed from those of Darius I's time (Briant, 1996, pp. 776-78).

62. Kistler, John M. (2007). War Elephants. U of Nebraska Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0803260047.

63. "Furthermore the second member of Delegation XVIII is carrying four small but evidently heavy jars on a yoke, probably containing the gold dust which was the tribute paid by the Indians." in Iran, Délégation archéologique française en (1972). Cahiers de la Délégation archéologique française en Iran. Institut français de recherches en Iran (section archéologique). p. 146.

64. André-Salvini, Béatrice (2005). Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520247314.

65. Bosworth, A. B. (1996). Alexander and the East : The Tragedy of Triumph: The Tragedy of Triumph. Clarendon Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780191589454.

66. Herodotus Book III, 89-95

67. Archibald, Zosia; Davies, John K.; Gabrielsen, Vincent (2011). The Economies of Hellenistic Societies, Third to First Centuries BC. Oxford University Press. p. 404. ISBN 9780199587926.

68. Archibald, Davies & Gabrielsen, The Economies of Hellenistic Societies 2011, p. 404.

69. Herodotus III, 89

70. 'Ινδοι, Greek Word Study Tool, Tufts University

71. Nations of the soldiers on the tombs, Walser. Also [1]

72. The Achaemenid Empire in South Asia and Recent Excavations in Akra in Northwest Pakistan Peter Magee, Cameron Petrie, Robert Knox, Farid Khan, Ken Thomas p.713

73. NAQŠ-E ROSTAM – Encyclopaedia Iranica.

74. DSf inscription

75. Stoneman, Richard (2015). Xerxes: A Persian Life. Yale University Press. p. 118. ISBN 9780300180077.

76. Herodotus. LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book VII: Chapters 1 56. pp. VII-26.

77. Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9781400866328.

78. Daniélou, Alain (2003). A Brief History of India. Simon and Schuster. p. 67. ISBN 9781594777943.

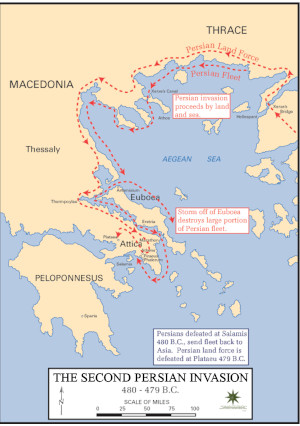

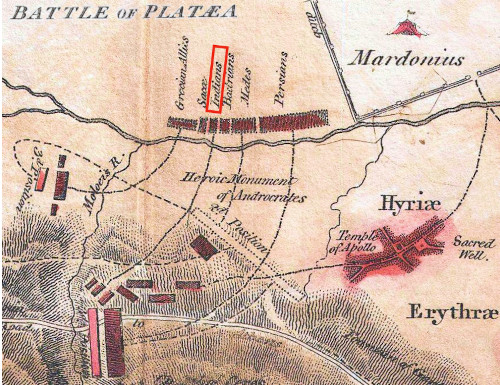

79. "A Sindhu contingent formed a part of his army which invaded Greece and stormed the defile at Thermopylae in 480 BC, thus becoming the first ever force from India to fight on the continent of Europe. It, apparently, distinguished itself in battle because it was followed by another contingent which formed a part of the Persian army under Mardonius which lost the battle of Platea"Sandhu, Gurcharn Singh (2000). A military history of ancient India. Vision Books. p. 179. ISBN 9788170943754.

80. 7 LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book IX: Chapters 1 89. pp. IX-32.

81. Freeman, Charles (2014). Egypt, Greece, and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780199651917.

82. Naqs-e Rostam – Encyclopaedia Iranica.

83. Naqs-e Rostam – Encyclopaedia Iranica List of nationalities of the Achaemenid military with corresponding drawings.

84. Tola, Fernando (1986). "India and Greece before Alexander". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 67 (1/4): 165. JSTOR 41693244.

85. LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book VIII: Chapters 97 144. p. Herodotus VIII, 113.

86. Roy, Kaushik (2015). Warfare in Pre-British India – 1500BCE to 1740CE. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 9781317586920.

87. LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book IX: Chapters 1 89. pp. IX-31.

88. Shepherd, William (2012). Plataea 479 BC: The most glorious victory ever seen. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 9781849085557.

89. Shepherd, William (2012). Plataea 479 BC: The most glorious victory ever seen. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 9781849085557.

90. Shepherd, William (2012). Plataea 479 BC: The most glorious victory ever seen. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 9781849085557.

91. Heckel, Waldemar; Tritle, Lawrence A. (2011). Alexander the Great: A New History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 164. ISBN 9781444360158.

92. Yenne, Bill (2010). Alexander the Great: Lessons from History's Undefeated General. St. Martin's Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780230106406.

93. Kistler, John M. (2007). War Elephants. U of Nebraska Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0803260047.

94. Holt, Frank L. (2003). Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions. University of California Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780520938786.

95. "Coins of this type found in Chaman Hazouri (deposited c.350 BC) and Bhir Mound hoards (deposited c.300 BC)." Article by Joe Cribb and Osmund Bopearachchi in Errington, Elizabeth; Trust, Ancient India and Iran; Museum, Fitzwilliam (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ancient India and Iran Trust. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9780951839911.

96. Classical Numismatic Group, Coin page

97. Bopearachchi & Cribb, Coins illustrating the History of the Crossroads of Asia 1992, pp. 57–59

98. CNG Coins

99. "Silver bent-bar punch-marked coin of Kabul region under the Achaemenid Empire, c.350 BC: Coins of this type found in quantity in Chaman Hazouri and Bhir Mound hoards" Article by Joe Cribb and Osmund Bopearachchi in Errington, Elizabeth; Trust, Ancient India and Iran; Museum, Fitzwilliam (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ancient India and Iran Trust. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9780951839911.

100. Bopearachchi, Coin Production and Circulation 2000, pp. 300–301.

101. "US Department of Defense". Archived from the original on 2020-06-10. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

102. Bopearachchi, Coin Production and Circulation 2000, pp. 308-.

103. Bopearachchi, Coin Production and Circulation 2000, p. 308.

104. Cribb, Investigating the introduction of coinage in India 1983, pp. 85–86.

105. "the local coins of the Achaemenid era (...) were the precursors of the bent and punch-marked bars" in Bopearachchi, Osmund. Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander's Conquest). p. 311.

106. About the hoard in Kabul: "In the same hoard there were also discovered two series of local silver coins which appear to be the product of local Achaemenid administration. One series (...) was made in a new way, which relates it to the punch-marked silver coins of India. It appears that it was these local coins, using technology adapted from Greek coins, which provided the prototypes for punch-marked coins made in India." p.57 "In the territories to the south of the Hindu Kush the punch-marked coins, descendants of the local coins of the Achaemenid administration in the same area, were issued by the Mauryan kings of India for local circulation." in Errington, Elizabeth; Trust, Ancient India and Iran; Museum, Fitzwilliam (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ancient India and Iran Trust. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9780951839911.

107. O. Bopearachchi, "Premières frappes locales de l'Inde du Nord-Ouest: nouvelles données," in Trésors d'Orient: Mélanges offerts à Rika Gyselen, Fig. 1 (this coin) CNG Coins Archived 2019-12-25 at the Wayback Machine

108. Bopearachchi, Coin Production and Circulation 2000, p. 309.

109. Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 15. ISBN 0226742210.

110. See also this map

111. Lowe, Roy; Yasuhara, Yoshihito (2016). The Origins of Higher Learning: Knowledge networks and the early development of universities. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 9781317543268.

112. Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 50. ISBN 9780984404308.

113. Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 255–256. ISBN 9781588369840.

114. "LacusCurtius • Strabo's Geography — Book XV Chapter 1 (§§ 39 73)". penelope.uchicago.edu.

115. Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 177. ISBN 9781400866328.

116. Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 125. ISBN 9781588369840.

117. "The Dhammapada Commentary furnishes us with some interesting information regarding Kosala. We learn from this work that Pasenadi, son of Mahākosala, was educated at Taxila." in The Indian Historical Quarterly. Calcutta Oriental Press. 1925. p. 150.

118. "One account suggests that, as a young man, Jivaka had travelled across India to Taxila, in the distant west, to study medicine under the well-known Disapamok Achariya" in Lowe, Roy; Yasuhara, Yoshihito (2016). The Origins of Higher Learning: Knowledge networks and the early development of universities. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-317-54326-8.

119. Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 256. ISBN 9781588369840.

120. Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 255. ISBN 9781588369840.

121. Scharfe, Hartmut (1977). Grammatical Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 89. ISBN 9783447017060.

122. Bakshi, S. R. (2005). Early Aryans to Swaraj. Sarup & Sons. p. 47. ISBN 9788176255370.

123. Ninan, M. M. (2008). The Development of Hinduism. Madathil Mammen Ninan. p. 97. ISBN 9781438228204.

124. Schlichtmann, Klaus (2016). A Peace History of India: From Ashoka Maurya to Mahatma Gandhi. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. 29. ISBN 9789385563522.

125. Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9788120804050.

126. "Sandrocottus, when he was a stripling, saw Alexander himself, and we are told that he often said in later times that Alexander narrowly missed making himself master of the country, since its king was hated and despised on account of his baseness and low birth". Plutarch 62-4 "Plutarch, Alexander, chapter 1, section 1".

127. Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 27. ISBN 9788120804050.; Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1957). "The Foundation of the Mauryan Empire". In K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (ed.). A Comprehensive History of India, Volume 2: Mauryas and Satavahanas. Orient Longmans. p. 4.: "The Mudrarakshasa further informs us that his Himalayan alliance gave Chandragupta a composite army ... Among these are mentioned the following : Sakas, Yavanas (probably Greeks), Kiratas, Kambojas, Parasikas and Bahlikas."

128. Shashi, Shyam Singh (1999). Encyclopaedia Indica: Mauryas. Anmol Publications. p. 134. ISBN 9788170418597.: "Among those who helped Chandragupta in his struggle against the Nandas, were the Sakas (Scythians), Yavanas (Greeks), and Parasikas (Persians)"

129. D. B. Spooner (1915). "The Zoroastrian Period of Indian History". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 47 (3): 416–417. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00048437. JSTOR 25189338. S2CID 162867863.: "After Alexander's death, when Chandragupta marched on Magada, it was with largely the Persian army that he won the throne of India. The testimony of the Mudrarakshasa is explicit on this point, and we have no reason to doubt its accuracy in matter[s] of this kind."

130. Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 210. ISBN 9788120804050.

131. Boyce, Mary (1982). A History of Zoroastrianism: Volume II: Under the Achaemenians. BRILL. p. 41. ISBN 9789004065062.

132. Boyce, Mary (1982). A History of Zoroastrianism: Volume II: Under the Achaemenians. BRILL. p. 278. ISBN 9789004065062.

133. Pingree, David (1988). "Review of The Fidelity of Oral Tradition and the Origins of Science". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 108 (4): 638. doi:10.2307/603154. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 603154.

134. Page 88: "There is one fragmentary lion head from Masarh, Distt. Bhojpur, Bihar. It is carved out of Chunar sandstone and it also bears the typical Mauryan polish. But it is undoubtedly based on the Achaemenian idiom. The tubular or wick-like whiskers and highly decorated neck with long locks of the mane with one series arranged like sea waves is somewhat non-Indian in approach . But, to be exact, we have an example of a lion from a sculptural frieze from Persepolis of 5th century BCE in which it is overpowering a bull which may be compared with the Masarh lion."... Page 122: "This particular example of a foreign model gets added support from the male heads of foreigners from Patna city and Sarnath since they also prove beyond doubt that a section of the elite in the Gangetic Basin was of foreign origin. However, as noted earlier, this is an example of the late Mauryan period since this is not the type adopted in any Ashoka pillar. We are, therefore, visualizing a historical situation in India in which the West Asian influence on Indian art was felt more in the late Mauryan than in the early Mauryan period. The term West Asia in this context stands for Iran and Afghanistan, where the Sakas and Pahlavas had their basecamps for eastward movement. The prelude to future inroads of the Indo-Bactrians in India had after all started in the second century B.C."... in Gupta, Swarajya Prakash (1980). The Roots of Indian Art: A Detailed Study of the Formative Period of Indian Art and Architecture, Third and Second Centuries B.C., Mauryan and Late Mauryan. B.R. Publishing Corporation. pp. 88, 122. ISBN 978-0-391-02172-3.. Also Kumar, Vinay (Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi Faculty Member) (2015). "West Asian Influence on Lion Motifs in Mauryan Art". Heritage and Us (4): 14.

135. The Analysis of Indian Muria Empire affected from Achaemenid's architecture art Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. In: Journal of Subcontinent Researches. Article 8, Volume 6, Issue 19, Summer 2014, Page 149-174.

136. Monuments, Power and Poverty in India: From Ashoka to the Raj, A. S. Bhalla, I.B.Tauris, 2015 p.18 [2]

137. "The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE-200 CE" Robin Coningham, Ruth Young Cambridge University Press, 31 aout 2015, p.414 [3]

138. Report on the excavations at Pātaliputra (Patna); the Palibothra of the Greeks by Waddell, L. A. (Laurence Austine)

139. The Origins of Indian Stone Architecture, 1998, John Boardman p. 13-22.

140. "A griffin carved from milky white chalcedony represents a blend of Greek and Achaemenid Persian cultures", National Geographic, Volume 177, National Geographic Society, 1990

141. Ching, Francis D.K; Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (2017). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 707. ISBN 9781118981603.

142. Fergusson, James (1849). An historical inquiry into the true principles of beauty in art, more especially with reference to architecture. London, Longmans, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 316–320.

143. The Illustrated Handbook of Architecture Being a Concise and Popular Account of the Different Styles of Architecture Prevailing in All Ages and All Countries by James Fergusson. J. Murray. 1859. p. 212.

144. Fergusson, James; Burgess, James (1880). The cave temples of India. London : Allen. p. 120.

145. M. Caygill, The British Museum A-Z companion (London, The British Museum Press, 1999)

146. E. Slatter, Xanthus: travels and discovery (London, Rubicon Press, 1994)

147. Smith, A. H. (Arthur Hamilton) (1892–1904). A catalogue of sculpture in the Department of Greek and Roman antiquities, British museum. London : Printed by order of the Trustees. pp. 46–64.

148. According to David Napier, author of Masks, Transformation, and Paradox, "In the British Museum we find a Lycian building, the roof of which is clearly the descendant of an ancient South Asian style.", "For this is the so-called "Tomb of Payava" a Graeco-Indian Pallava if ever there was one." in "Masks and metaphysics in the ancient world: an anthropological view" in Malik, Subhash Chandra; Arts, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the (2001). Mind, Man, and Mask. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. p. 10. ISBN 9788173051920.

149. Boardman (1998), 13

150. Harle, 22, 24, quoted in turn

151. A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd, 2003, p.87

152. Buddhist Architecture, by Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010 p.44

153. Marshall, John (2013). A Guide to Taxila. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9781107615441.

154. Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 73–76. ISBN 9780195356663.

155. "The derivation of the Kharosstshī script from Aramaic, which was used throughout the Achaemenid realm, is relatively straightforward, but the development of Brāhmī as a chancellery script for writing Aśokan inscriptions may have also been related to an effort to emulate the royal inscriptions of Achaemenid or later Seleukid rulers." in Neelis, Jason (2011). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange within and beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. Brill. p. 98. ISBN 9789004194588.

156. Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 39. ISBN 9788172110284.

157. "Ashoka" in Encyclopaedia Iranica

158. Hultzsch, E. (1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum v. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xlii.

159. Sharma, R. S. (2006). India's Ancient Past. Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780199087860.

160. "The word dipi appears in the Old Persian inscription of Darius I at Behistan (Column IV. 39) having the meaning inscription or "written document" in Congress, Indian History (2007). Proceedings - Indian History Congress. p. 90.

161. Voogt, Alexander J. de; Finkel, Irving L. (2010). The Idea of Writing: Play and Complexity. BRILL. p. 209. ISBN 978-9004174467.

162. Dupree, L. (2014). Afghanistan. Princeton University Press. p. 286. ISBN 9781400858910. Retrieved 2016-11-27.

163. Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 51.

164. Vishnu, Asha (1993). Material Life of Northern India: Based on an Archaeological Study, 3rd Century B.C. to 1st Century B.C. Mittal Publications. p. 141. ISBN 9788170994107.

165. Page 122: About the Masarh lion: "This particular example of a foreign model gets added support from the male heads of foreigners from Patna city and Sarnath since they also prove beyond doubt that a section of the elite in the Gangetic Basin was of foreign origin. However, as noted earlier, this is an example of the late Mauryan period since this is not the type adopted in any Ashoka pillar. We are, therefore, visualizing a historical situation in India in which the West Asian influence on Indian art was felt more in the late Mauryan than in the early Mauryan period. The term West Asia in this context stands for Iran and Afghanistan, where the Sakas and Pahlavas had their base-camps for eastward movement. The prelude to future inroads of the Indo-Bactrians in India had after all started in the second century B.C."... in Gupta, Swarajya Prakash (1980). The Roots of Indian Art: A Detailed Study of the Formative Period of Indian Art and Architecture, Third and Second Centuries B.C., Mauryan and Late Mauryan. B.R. Publishing Corporation. pp. 88, 122. ISBN 978-0-391-02172-3..

166. According to Gupta this is a non-Indian face of a foreigner with a conical hat: "If there are a few faces which are nonIndian , such as one head from Sarnath with conical cap ( Bachhofer , Vol . I , Pl . 13 ), they are due to the presence of the foreigners their costumes, tastes and liking for portrait art and not their art styles." in Gupta, Swarajya Prakash (1980). The Roots of Indian Art: A Detailed Study of the Formative Period of Indian Art and Architecture, Third and Second Centuries B.C., Mauryan and Late Mauryan. B.R. Publishing Corporation. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-391-02172-3.

167. "The relatively high quality of terracotta sculptures recovered from Maurya strata at Mathura suggests some level of artistic activity prior to the second century BCE." Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 35. ISBN 9789004155374.

168. Kala, Satish Chandra (1980). Terracottas in the Allahabad Museum. Abhinav Publications. p. 5. ISBN 9780391022348.

169. "The largest number of mother-goddess figurines has been found in western Uttar Pradesh in Mathura, which in the Mauryan period became an important terracotta making centre outside Magadh." in Sant, Urmila (1997). Terracotta Art of Rajasthan: From Pre-Harappan and Harappan Times to the Gupta Period. Aryan Books International. p. 136. ISBN 9788173051159.

170.

"Iranian Heads From Mathura, some terracotta male-heads were recovered, which portray the Iranian people with whom the Indians came into closer contact during the fourth and third centuries B.C. Agrawala calls them the representatives of Iranian people because their facial features present foreign ethnic affinities." Srivastava, Surendra Kumar (1996). Terracotta art in northern India. Parimal Publications. p. 81.

171. "Mathura has also yielded a special class of terracotta heads in which the facial features present foreign ethnic affinities." Dhavalikar, Madhukar Keshav (1977). Masterpieces of Indian Terracottas. Taraporevala. p. 23.

172. "Soldier heads. During the Mauryan period, the military activity was more evidenced in the public life. Possibly, foreign soldiers frequently visited India and attracted Indian modellers with their ethnic features and uncommon uniform. From Mathura in Uttar Pradesh and Basarh in Bihar, some terracotta heads have been reported, which represent soldiers. Artistically, the Basarh terracotta soldier-heads are better, executed than those from Mathura." in Srivastava, Surendra Kumar (1996). Terracotta art in northern India. Parimal Publications. p. 82.

173. Vishnu, Asha (1993). Material Life of Northern India: Based on an Archaeological Study, 3rd Century B.C. to 1st Century B.C. Mittal Publications. p. XV. ISBN 9788170994107.

174. "The figure of a Persian youth (35.2556) wearing coat, scarf, trousers and turban is a rare item." Museum, Mathura Archaeological (1971). Mathura Museum Introduction: A Pictorial Guide Book. Archaeological Museum. p. 14.

175. Sharma, Ramesh Chandra (1994). The Splendour of Mathurā Art and Museum. D.K. Printworld. p. 58.[permanent dead link]

176. xxiii. 6 in Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History. London: Bohn (1862) Book 23. pp.316-345.

177. James, Montague Rhodes (2007). The Lost Apocrypha of the Old Testament: their titles and fragments. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 93. ISBN 9781556352898.

178. Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History. London: Bohn (1862) Book 23. pp.316-345.

179. Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. pp. 7–12. ISBN 9781400866328.

180. Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 9781400866328.

Bibliography• Archibald, Zosia; Davies, John K.; Gabrielsen, Vincent (2011), The Economies of Hellenistic Societies, Third to First Centuries BC, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199587926

• Alram, Michael (2016), "The Coinage of the Persian Empire", in William E. Metcalf (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage, Oxford University Press, pp. 61–, ISBN 9780199372188

• Boardman, John (1998), "Reflections on the Origins of Indian Stone Architecture", Bulletin of the Asia Institute, pp. 15–19, 1998, New Series, Vol. 12, (Alexander's Legacy in the East: Studies in Honor of Paul Bernard), p. 13-22, JSTOR

• Bopearachchi, Osmund (2000), "Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander's Conquest)", Indologica Taurinensia, 25, International Association of Sanskrit Studies

• Bopearachchi, Osmund (2017), "Achaemenids and Mauryans: Emergence of Coins and Plastic Arts in India", in Alka Patel; Touraj Daryaee (eds.), India and Iran in the Longue Durée, UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies, pp. 15–48

• Bopearachchi, Osmund; Cribb, Joe (1992), "Coins illustrating the History of the Crossroads of Asia", in Errington, Elizabeth; Cribb, Joe; Claringbull, Maggie (eds.), The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan, Ancient India and Iran Trust, pp. 56–59, ISBN 978-0-9518399-1-1

• Cribb, Joe (1983), "Investigating the introduction of coinage in India - A review of recent research", Journal of the Numismatic Society of India: 80–101

• Dandamaev, M. A. (1989), A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-09172-6

• Eggermont, Pierre Herman Leonard (1975), Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the Siege of the Brahmin Town of Harmatelia, Peeters Publishers, ISBN 978-90-6186-037-2

• Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

• Magee, Peter; Petrie, Cameron; Knox, Richard; Khan, Farid; Thomas, Ken (2005), "The Achaemenid Empire in South Asia and Recent Excavations in Akra in Northwest Pakistan", American Journal of Archaeology, 109 (4): 711–741, doi:10.3764/aja.109.4.711, S2CID 54089753

• Mitchiner, Michael (1978), The Ancient & Classical World, 600 B.C.-A.D. 650, Hawkins Publications ; distributed by B. A. Seaby, ISBN 9780904173161

• Neelis, Jason (2010), Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5

• Olmstead, A. T. (1948), History of the Persian Empire, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-62777-9

• Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. ISBN 9788122411980.

External links• Ancient India, A History Textbook for Class XI, Ram Sharan Sharma, National Council of Educational Research and Training, India Iranian and Macedonian Invasion, pp 108

• INDIA iii. RELATIONS: ACHAEMENID PERIOD