Indian Education Commission (1882-83) by YourArticleLibrary

Accessed: 8/25/24

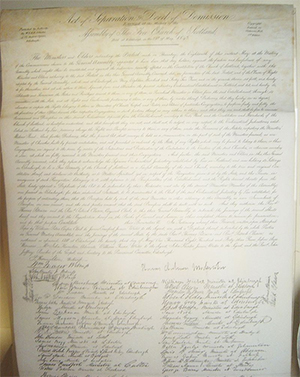

The Calcutta School-Book Society was an organisation based in Kolkata during the British Raj. It was established in 1817, with the aim of publishing text books and supplying them to schools and madrasas in India.

In 1814, four years before the establishment of the Calcutta School Society and three years before the formation of the Calcutta School-Book Society,

the London Missionary Society, under the supervision of Robert May, set up 36 elementary schools in Chinsurah, West Bengal, India (now Chunchura).[1]

Fort William College was created in 1800 by

Lord Wellesley, the Governor-General at the time. A growing eagerness and enthusiasm towards education led to the translation and printing of the Bible in Sanskrit, Bengali, Assamese and Oriya. Scholars like

Mrityunjay Vidyalankar and

Ramram Basu did the work with foreign language experts and alongside, the Ramayana, Mahabharata and other Indian epics were skilfully translated into different languages. The Calcutta School-Book Society followed a similar path and helped Bengali prose writers achieve national and international acclaim. As a result of rise of widespread higher education, journalism became a major component of British society, with magazines like the Magazine for Indian Youth and newspapers like the Samachar Darpan (The News Mirror) becoming a widespread phenomenon. Mass education, however, came much later in 1885 with

the Hunter Education Commission, which ended

James Long's and other missionary organisations' zealous ideas of dissipating education among the masses, in an expression of the continuing battle for superiority of the British over the natives.

To strengthen their political colonisation of India, the British strategised emotional and intellectual colonisation and, in the Charter of 1833, announced English as the official language of British India.

This ideology had at its fulcrum, Thomas Babington Macaulay’s assertion of the British ideology that Western learning was superior to Oriental languages and indigenous Sanskrit and other vernacular knowledge. The setting up of several colleges in Calcutta, India, namely

the Hindu College in 1816 and

the Sanskrit College in 1824, portrays this shift of emphasis from the study of Oriental languages in

Fort William College to the establishment of the English language, ensuring that all Indian students studying in these new colleges and schools, which were developed under the Calcutta School Society (1818), had to learn English whether they liked it or not.

In the shadow of this shift in cultural paradigm, the Calcutta School-Book Society also known as the Calcutta Book Society, was instituted on 4 July 1817, in Calcutta (now known as Kolkata), the then capital of the British Empire. The society was set up under the patronage of

Lord Marquess of Hastings who was Governor-General at that point of time. The School-Book Society was set up with the coming of Western methods in education to India and henceforth, the rising demand for textbooks and dictionaries. The society also encouraged the establishment of new elementary schools. The Calcutta School Society, an educational institution independent from the School-Book Society was set up on 1 September 1818. The government established it with a sole aim 'to endorse education beyond the curriculum' and to introduce similar teaching techniques at different schools and to develop, build or reconstruct old and new schools. The Calcutta School-Book Society on the other hand aimed at publishing textbooks for these new schools and other institutions of higher learning.

-- Calcutta School-Book Society [Calcutta Book Society], by Wikipedia

Essay Contents:1. Essay on the Background of Indian Education Commission

2. Essay on Composition of the Council

3. Essay on the Report of Indian Education Commission

________________________________________

1. Essay on the Background of Indian Education Commission:1. There was no spread of mass education due to the indifferent and apathetic attitude of the Government since 1854. The progress of primary education was extremely slow.

2. The system of indigenous education was gradually decaying due to willful neglect of the Government as well as want of native patronage.

3. There was no suitable Government help to primary education.

4. The Government did not help in any way the Indian private enterprise in education which was the directive of the Despatch. It was practically crushed and consequently primary education was neglected.

5. The Government had little intention to withdraw gradually from the arena of education which the framers of the Despatch intended.

6. The quality of instruction was deteriorated at an alarming rate.

7. The Despatch categorically discarded the Downward Filtration Theory but it was still favoured by the Government.

8. The system of “grant-in-aid” did not work properly. It was not carried out by the Government as suggested by the Despatch. The Indian private enterprise did not get much financial assistance from the Government. Educational expenditure was mainly directed to Government educational institutions.

The declared non-interference on the part of the Government in education was not carried into effect. But the number of Government educational institutions was increasing day by day. A strong belief was created in the minds of the common people that the Government was trying to destroy the private enterprise in education. Thus the Government was determined to destroy the very spirit of the Despatch.

9. National consciousness was aroused in India which was demanding national education based on national cultural tradition as against western culture. At the end of the 19th century Hindu chauvinism was at its peak.

10. The missionaries were also dissatisfied. After the Despatch they thought they would be the chief agency in Indian education. But their hope was totally frustrated. They criticised the Government policy of religious neutrality in education which they characterised as “Godless and irreligious”. They were agitating against the step-mother-like attitude of the Education Department.

They even started campaign in England and a Council known as the “General Council of Education in India” was set up there in 1878. The missionaries sent a deputation to the then Secretary of State for India (Lord Huttington) and the future Governor-General of India (Lord Ripon) to place their grievances.________________________________________

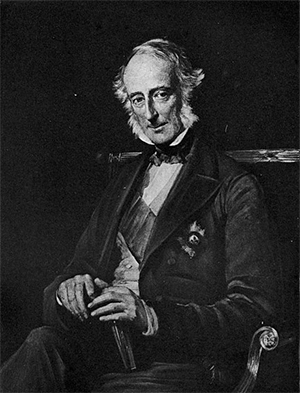

2. Essay on Composition of the Council:The Commission was appointed on 3rd Feb., 1882, by Lord Ripon. It is the first Education Commission in India. Sir William W. Hunter, a member of the Governor General’s Executive Council, was its chairman. Hence it is commonly known as the Hunter Commission. It consisted of twenty members.

The Indian members of the commission were Syed Ahmed Khan, Mr. Haj Ghulam of Amritsar, Mr. Anand Mohan Bose, Mr. P. Rangananda Mudaliar, Babu Bhudeb Mukherjee, Justice K. T. Telang and Maharaja Jyotindra Mohan Tagore. Dr. W. Miller was the representative of the missionaries in the Commission. Mr. B. L. Rice, the then D.P.I, of Mysore was appointed the Secretary of the Commission.

The main objectives and terms of reference of the Commission were:

………. “to enquire into the manner in which effect had been given to the principles of Despatch of 1854 and to suggest such measures as it might think desirable with a view to the further carrying out of the policy therein laid down”.

1. To enquire especially about the primary education as there was a strong demand for mass education;

2. To consider ways and means about the expansion of the grant-in-aid system;

3. To enquire into the activities of the provincial department of education;

4. To enquire about the respective role of the Government Institutions and private institutions in a national system of education;

5. To decide Government attitude towards religious instruction.

Activities of the Indian Universities, technical education and education of the Europeans were kept outside the purview of the Commission.The Commission toured throughout the country for eight months. It worked for seven weeks in Calcutta. The commission appointed provincial Committees which gave reports about education of their respective provinces. The final report was based on these provincial reports. In 1883 the Commission submitted its voluminous report of 600 pages with 222 resolutions. It is an important historical document.

________________________________________

3. Essay on the Report of Indian Education Commission:Policy:

It severely criticised the educational policy of the Government. It opined that the Government has been going against the directives of the Despatch. Private educational institutions were not at all financially helped by the provincial Governments.

The Commission as such proposed liberalisation of the grant-in-aid system; the Government should refrain from establishing new educational institutions; primary education should be handed over to local bodies; and secondary and collegiate education to responsible committees.

The Commission suggested two important measures for working out the policy:

(a) The Government should curtail its educational activities and withdraw from direct enterprise;

(b) It should organise a proper system of grant-in-aid.

1. Primary Education:

The Commission paid special attention to the-subject of primary education. In view of the slow progress of primary education during the period 1854-1882, the subject of primary education figures prominently in the Report of the Indian Education Commission.

The Commission declared boldly that while every branch of education can justly claim the fostering care of the State, the elementary education of the masses, its provision, extension and improvement deserves the greatest attention in any national system of education.

The Commission made altogether 36 important recommendations for the spread of elementary education which can conveniently be divided into the following six heads:

A – Policy;

B – Encouragement to indigenous schools;

C – Legislation and Administration;

D – School administration (internal management);

E – Training of teachers;

F – Finance.

A-Policy:

i. Primary education should be self-sufficient. It should not be preparatory to secondary education.

ii. Mass education is needed to remove mounting illiteracy. Primary education should be regarded as the instruction of the masses through the vernacular in such subjects as will fit them best for their position in life.

iii. Strenuous efforts of the State should now be directed to the improvement, provision and extension of elementary education of the masses.

iv. Highest priority should be attached to the extension and development of primary education without which no national system of education can be laid down.

v. Immediate attention should be devoted to those districts which are backward in respect of primary education.

B – Indigenous institutions: Encouragement to indigenous schools:

i) The Commission was of the opinion that these schools deserved encouragement and incorporation into official system. The Commission was fully aware of the utility of the indigenous schools and recommended that these should form the basis of mass education. This was a recommendation in the right direction.

ii) The commission recognised the merits and demerits of the indigenous schools. “Admitting, however, the comparative inferiority of indigenous institutions we consider the efforts should now be made to encourage them. They have survived competition, and thus have proved that they possess both vitality and popularity”. The Commission defined the indigenous schools “as one established or conducted by natives of India on native methods”. For the improvement of these schools the Commission made the following recommendations:

iii) Instruction in indigenous schools should be secular;

iv) The system of “payment by result” should be introduced as a method of financing the indigenous schools. This was not a happy recommendation. A better system would have been that of “capitation grants”;

v) The Commission suggested that an attempt should be made to improve the teaching in indigenous schools, gradually and steadily. For this purpose training of teachers should be encouraged;

vi) The system of inspection and standard of examination should be improved;

vii) Indigenous schools should be open to all irrespective of caste, creed and sex;

viii) The Commission held the view that the administration of indigenous schools should be handed over to the District and Municipal Boards. Financial support should be given to these schools by the Boards. The Education Departments of the provincial Governments should help financially to the District and Municipal Boards. This was no doubt a memorable proposal for democratization of Indian education,

ix) Financial help should be provided to encourage the depressed classes to receive education.

C – Legislation and Administration:

The Commission recommended that the control of primary education should be made over to District and Municipal Boards. These local boards should form “Education Boards” in their localities. The primary schools of their localities should be handed over to these “Education Boards”. But unfortunately the “Education Boards” failed to fulfill the desired expectation in respect of improvement in the field of primary education.

D – School Administration (internal management of schools):

i) There should be no attempt to achieve uniformity. The content of instruction, i.e., the curriculum in primary schools should be adopted to the local needs and environment and should be simplified wherever possible,

ii) Practical subjects such as Indian methods of arithmetic and accounts (book-keeping), agriculture, physical science, hygiene, medicine, fine arts etc. should be introduced.iii) School managers should be free to choose the text books for their schools.

iv) Utmost elasticity should be permitted regarding hours of the day and the seasons of the year during which schools are to remain open.

v) There should be provision for physical exercise and native games and sports in primary schools.

vi) Primary education should not be compulsory in any province.

vii) The Inspectors themselves will take examinations as far as possible.

viii) Instruction should be through the mother-tongue of the children

ix) There should be one Normal School in each sub-division for training primary teachers.

E – Training of Teachers:

To improve the standard of teaching, the indigenous school teachers and their probable successors should be encouraged to undergo training. Inspite of the positive directive in the Despatch there was no remarkable improvement in this field. The Commission laid great emphasis on the training of primary teachers. It emphasised the need of establishing more Normal Schools for the training of teachers so that there might be at least one Normal School in each Sub-division and under a Divisional Inspector.

The Commission recommended that the teachers should not only know the principles of teaching but also they should learn how to apply them in practice. The Government should bear all the expenses of training of teachers.

F- Finance:

In the opinion of the Commission finance is the greatest obstacle in the way of primary education.

So it made important recommendations with regard to finance:

i) A specific fund should be created in each local-self Govt. for primary education.

ii) Local funds should be utilised mainly for primary education.

iii) It was the duty of the Provincial Government to assist the local funds by a suitable system of grant-in-aid.

iv) The accounts of the primary education fund in municipal areas should be separated from those for the rural areas.

v) The Provincial Governments should bear the expenditure for Normal Schools and School Inspection.

vi) The Commission desired that one-third of the total expenditure for primary education should be borne by the Provincial Government; but it was silent regarding from where the huge money required for primary education would be available. For this lacuna in the Report most of the recommendations of the Commission for the development of primary education remained ineffective.

vii) The report emphasised “payment by results” to the primary schools. This was no doubt a wrong suggestion.

viii) Free studentships to poor students and scholarships to meritorious students were also recommended.

ix) The doors of all the Government and aided primary schools should be open to all.

2. Secondary Education:

Soon after the receipt of the Despatch, the number of secondary schools under Government control multiplied rapidly. Due to the provision of grant-in-aid there was a large increase in the number of private Secondary schools also.

The Commission had to make recommendations on two important matters connected with the expansion of secondary education:

(1) Firstly, it had to suggest ways and means for seeming a more rapid expansion of secondary education;

(2) Secondly, the Commission had to recommend the best agency for expansion of secondary education.

Opinion was strongly divided on this subject:

(a) One view held that Government ought to multiply the number of secondary schools directly under its control,

(b) Another view favoured private enterprise, particularly Indian private enterprise, as an effective means of expanding secondary education because it is less costly and will take shorter time. The Commission recommended that the Govt. ought to withdraw from the field of direct management of secondary schools and encourage private enterprise as largely as possible.

It was of opinion that the relation of the State to primary education was different from that to secondary education. It was a duty of the State to provide primary education. Secondary education did not have such a paramount claim upon the State. Government was not under an obligation to provide it directly.The Commission, therefore, recommended that secondary education should, as far as possible, be provided on the grant-in-aid basis and Government should withdraw, as early as possible from the direct management of secondary schools. The Commission emphasised that the system of grant-in-aid should liberally and judiciously be followed. The goal of Govt. efforts should be to transfer gradually all Government secondary schools to a suitable non-Government agency.

The Govt., of course, could establish secondary schools in places “where they may be required in the interests of the people, and where the people themselves may not be advanced or wealthy enough to establish such schools for themselves with a grant-in-aid”. The Commission emphasised that the duty of the Govt. was restricted only to the establishment of one efficient and Model High School, Govt. or aided, in each district.

Regarding the use of mother-tongue as the medium of instruction the recommendation of the Commission was disappointing and unsatisfactory. It was silent on the subject, and evidently favoured the use of English. Thus the mother-tongue as a medium of instruction was neglected by the Commission. The Despatch, of course, favoured the mother-tongue as the medium of instruction at the secondary stage. Again, the Commission did not lay down any definite policy with regard to Middle Schools.

The Despatch also emphasised the importance of training of secondary teachers for qualitative improvement of education. But no satisfactory measures were taken to train secondary teachers. There were only two training institutions at that time for secondary teachers in India (Madras and Lahore). The Commission emphasised training of secondary teachers with some hesitation both in theory and practice, in the principles of teaching and practice of teaching.

More normal schools should be established for training of Secondary teachers and the Govt. should bear all the expenses of these institutions. In respect of appointments, in Government or aided schools, preference should be given to trained teachers. In the cases of graduate teachers the period of training may be shorter (one year) than that for other teachers.

Secondary education was mainly theoretical, narrow and unpractical. The Despatch explicitly stated that the instruction in secondary schools should be practically useful. But this advice for vocational education was utterly neglected. The Commission, therefore, gave considerable attention to the provision of vocational courses at the upper secondary stage (VIII – X) with a view to preparing pupils for various walks of life.It recommended a bifurcation of the secondary course and said:

“We, therefore, recommend that in the upper classes of high schools there be two divisions, – one leading to the Entrance Examination of the Universities, the other of a more practical character, intended to fit youths for commercial or non-literary pursuits”. The first is known as “Course ‘A’ and the Second ‘B’ course. But the attempt to popularise the ‘B’ Course ultimately failed.

3. Collegiate and University Education:

The Government Resolution appointing the Commission observed that it would “not be necessary for the Commission to enquire into the general working of the Indian Universities”. The Commission, therefore, could not study the problem of collegiate education in a comprehensive manner and hence its recommendations on this subject are not so important.The Report of the Commission did little to improve University education. The Commission was also precluded from studying professional colleges because that “would expand unduly” the task before it.

But its recommendations on other matters reacted indirectly on the development of collegiate education in two ways:

a) Firstly, the recommendations led to a great expansion of secondary education. As there was no alternative channel and University degree was regarded as passport of lucrative Govt. posts the students who passed matriculation examination joined the colleges. As a result the number of students seeking admission to colleges increased substantially.

b) Secondly, the recommendations of the Commission created a background in which Indian private enterprise could thrive. Contrary to missionary institutions new institutions managed by Indians came into the field in large numbers.

The Commission also voluntarily made some direct references to the development of collegiate education.

These are:

a) Gradual withdrawal by the Govt. from the field of collegiate education;

b) More liberal grants to colleges in order to encourage Indian private enterprise in collegiate education;

c) Necessity of the maintenance of higher education in India;

d) Freedom to private colleges to determine college fees;

e) Introduction of a large number of optional subjects;

f) Liberal grants for libraries and research work;

g) Scholarships to poor but meritorious students.

As a result of these recommendations higher liberal education expanded rapidly at the cost of professional and technical education. Quality of higher education had also been lowered.4. Special Recommendations for the Establishment of Special schools and Colleges for the Children of Native Princes and the Muhammedans:

The Commission recommended the establishment of institutions, schools and colleges, for the education of princes and children of native chiefs. On account of the existence of wide disparity between the educational advancement of the Hindus and Muslims, the commission also proposed to provide some special educational facilities to the Muslim community to encourage them to receive education.

Hence, it was recommended that Government should award scholarships, stipends and free studentship to Muslim students in large numbers, and to establish Muslim Normal Schools and appoint Muslim Inspectors. This recommendation was not a happy one as it led to communal trouble in later years.

5. Adult Education:

Mass illiteracy in India attracted the attention of the Commission, and hence it recommended the establishment of Night Schools for adults.

6. Religious Education:

The missionaries demanded that religion should be made an integral part of education. The Commission discarded this demand and recommended complete religious neutrality in the field of education. It, of course, favoured religious instruction on voluntary basis and recommended preparation of text books on morality and organisation of religious lectures.7. Women’s Education:

The Commission was fully conscious of the low rate of literacy among Indian women. It found that 95.5% of women were illiterate. “It will have been seen that female education is still in an extremely backward condition and that it needs to be fostered in every legitimate way………….. Hence we think it expedient to recommend that public funds of all kinds – local, municipal and provincial – should be chargeable in an equitable proportion for the support of girls’ schools as well as for boys’ schools”.For the spread of women education the commission made some important recommendations:

a) Govt. should give more liberal grants to private girls’ schools;

b) School fees should be nominal;

c) Govt. should give award grants to women teachers;

d) Prizes should be given to girls above 12;

e) Establishment of Normal Schools for training of women teachers;

f) Introduction of simpler and easier curriculum for girls than boys;g) Organisation of a separate Inspectorate for girls’ education and appointment of lady Inspectors.

8. Role of the Missionaries in Indian Education:

The missionaries hoped that they would dominate the entire educational arena in India. In order to fulfill this objective they were agitating even in England. But the recommendations of the Commission totally frustrated their expectations. The fate of the missionaries was completely sealed by the Commission. Their demand for spreading education as the main agency was rejected by the Commission.

The Commission favoured purely Indian private enterprise and not European private enterprise like the missionaries. “The private effort, which it is mainly intended to evoke is that of the people themselves”, the Commission remarked. It further observed: “We think it will to put on record our unanimous opinion that withdrawal of direct departmental agency should not take place in favour Of missionary bodies and the departmental institutions of the higher order should not be transferred to missionary management”. It is evident thus that missionary enterprise was regarded as inferior to Indian private enterprise.

9. Gradual Withdrawal of the Government from Educational Field:

It was the policy of the Commission to make the Government free from the responsibilities of national education. It recommended that the responsibilities of mass education should be entrusted to the Indian people. Therefore, the people were required to raise funds for their own education.The money thus saved could be utilised in sanctioning grants-in-aid to a larger number of institutions. Accordingly primary education was placed under the control and supervision of Local Boards and secondary and collegiate education was entrusted to the fostering care of Indian private enterprise under the proper direction of the Government.

10. Grant-in-Aid System:

The Commission laid special stress on the improvement and extension in the system of grant-in-aid. It gave directions to all the provinces to set up a general principle in this respect consistent with their local needs. It, however, wiped out the distinction between Government and non-Government institutions. The rules of grant-in-aid were liberalised, made simpler and lenient.

Every application for a grant-in-aid should receive an official reply and in case of refusal the reasons for such refusal should always be given. Grants be paid without delay when they become due according to the rules. Interference with internal affairs of the institutions was forbidden.

11. Results:

The Government of India accepted almost all the recommendations except the recommendation regarding religion.The report produced three major results:

a) Administration of primary education was entirely handed over to the Local Self-Government Bodies.

b) Withdrawal by the Government from the field of secondary education was partially carried out.

c) Place of Indian enterprise in national education was recognised.

12. Criticism:

(1) The Commission favoured withdrawal by the Govt. from the field of education as early as possible. This was a memorable recommendation with far-reaching effects.

(2) It intended rapid development of education from primary to uni¬ersity level with the help of both Govt. and private enterprises.

(3) The commission emphasised keenly on adult education with the intention to remove mass illiteracy in our country more than a century ago and thus the intention was definitely good.

(4) Administration of primary education was left to the local Self-Government bodies mostly represented by Indians. Thus an attempt was made to democratise and Indianise educational administration. The attempt is no doubt praiseworthy.

(5) Indian enterprise in a national system of education was recognised by the Commission.

(6) Recommendations with regard to the place of the missionaries and religion in education were also no doubt commendable.

(7) The Commission virtually supported the educational policies laid down in the Despatch of 1854 and Standby Despatch of 1859. No new policy was recommended by the Commission.

The only and most important policy recommended by the Commission was regarding the place of missionaries in education. But we should remember that it was not the function of the Commission to frame policy but to execute.

(8) Vocational education in the upper classes of secondary schools was recommended and two types of Courses ‘A’ and ‘B’ were to be introduced for the purpose. But the ‘B’ course was not implemented. Technical and industrial education was not recommended by the Commission with obvious reasons. This major defect was exhibited later in the field of secondary education which the national leaders wanted to rectify.

(9) The Commission laid emphasis on primary education, but it was not made free, universal and compulsory.

(10) It failed to make any suitable provision for financing primary education. Most of its financial recommendations with regard to primary education were not carried out due to lack of adequate finances.(11) The principle of “payment by result” was not a happy recommendation. It was not good for the country and as such it was later abolished by Lord Curzon.

(12) The Commission was almost silent on the question of medium of instruction at the secondary stage and thereby indirectly supported English as the medium of instruction and neglected the claim of the mother-tongue and other modern Indian languages.(13) The Commission made some recommendations with regard to training of teachers at secondary stage in half-hearted manner and these were not implemented in right earnest, and this non-implementation led to dearth of trained teachers in the field of secondary education.

(14) The recommendation for granting special educational facilities to the Muslim students introduced communalism in education in later years.

(15) The area of recommendation of the Commission was narrow. The Government desired that the Commission should only enquire into limited and specific fields of education.(16) The Commission made some casual recommendations with regard to higher education. As a result, some defects originated in the field of higher education which Lord Curzon had to heal up. These included lop-sided development of liberal education, neglect of professional education, deterioration in the quality of higher education and neglect of modern Indian languages.