Chapter 7: Gupta Gold

c300–500 AD

REDEEMED BY RUDRADAMAN

JUST OUTSIDE the town of Junagadh in the Saurashtra peninsula of Gujarat an isolated massif rears abruptly from low-lying fields and pastures. This is Girnar, or ‘Giri-nagar’ (‘city-on-the-hill’), one of the most remarkable mountains in India,1 whose several peaks, some over a thousand metres high, are strung about with a garland of the precariously situated temples so beloved of the Jains. Throughout the year a trickle of Jain pilgrims from all over Gujarat and Rajasthan converges on Junagadh to climb the mountain and make a parikrama (meritorious circuit) of its craggy shrines.

Their route begins along a trail of deceptive ease which, issuing from the west gate of the town, quickly leads to a bridge. Thence, by the shortest of detours, the curious may inspect Girnar’s least-visited attraction. Roughly seven metres by ten, the hump-backed mass of granite that bears Ashoka’s Major Rock Edict can hardly compare with the beetling cliffs and the airy vistas that lie ahead. Wayfaring Jains usually give it a miss. Whether bent to their staves or dangling from doolies (seats for one, suspended from a pole borne by two), they press on to the ethereal heights of their local Olympus.

Isolated and ignored in this remote extremity of the subcontinent, the Ashoka rock, ‘converted by the aid of the iron pen … into a book’ (as James Tod put it), yet retains the capacity to stir an indologist’s dusty emotions. Its improbable location speaks volumes for the extent of ancient India’s empires, and it is vastly more impressive than the much-reduced replica which slumps, equally ignored, outside the main entrance of New Delhi’s National Museum. It is also rather more informative. On close inspection, the rain-blackened rock is found to be neatly etched not only with the ‘pin men’ script of the Ashoka Brahmi inscription but also with two much later records. Both relate to repairs carried out on an irrigation system in the vicinity of Junagadh which has long since disappeared. One is of the reign of Skanda-Gupta, last of the five great Gupta emperors, and so dates from the mid-fifth century AD; an important and colourful piece of verse, it will be noticed later. The other is earlier (150 AD) and even more informative. It tells of the history of the dam, how it was constructed by Chandragupta Maurya’s governor (hence, as noted, providing the only evidence for the first Maurya’s conquests in Gujarat), and how subsequently Ashoka’s provincial governor, evidently a Yavana, added new conduits or canals. Thanks to such improvements, more land was no doubt cleared and more settlers flocked to Junagadh, whose fine soil must have rewarded the engineers’ skills with double cropping and handsome yields.

Sadly, though, according to this second inscription the whole irrigation system had since suffered severe storm damage. In fact it was thought to be beyond repair. Then ‘Maha-kshtrapa (‘Great Satrap’) Rudradaman’ decreed otherwise. Under the direction of his minister Suvisakha, a Pahlava (Parthian), the necessary rebuilding had been put in hand and the system was now, in 150 AD, again in operation. According to the inscription, the Great Satrap Rudradaman had done all this ‘without oppressing the people of the town or the province by exacting taxes, forced labour, donations or the like’. It had been paid for entirely out of his own treasury. Not unreasonably he claimed to be the most undemanding of rulers.

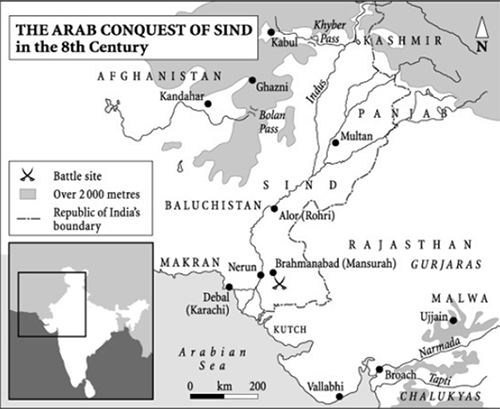

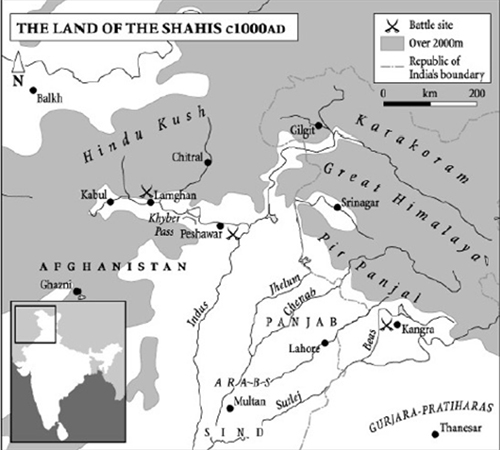

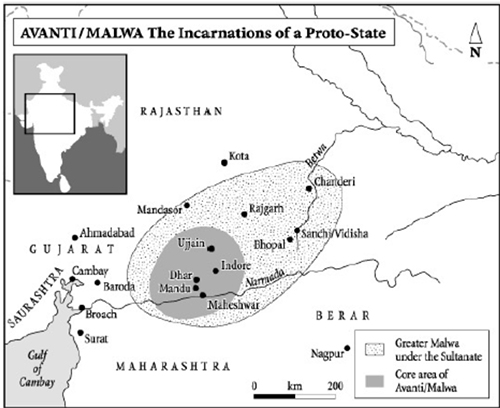

This episode, although presented as testimony of Rudradaman’s indomitable character, may also be taken as symptomatic of his redemptive reign, both of which the inscription describes in fulsome detail. For Rudradaman had inherited a kingdom which was every bit as badly in need of repair as the Junagadh dam. He was in fact one of those, probably Scythian, ‘Western Satraps’ who were offshoots of the Shaka kingdom established by Maues, Azes and Spalirises in Gandhara and the Panjab and which succeeded that of the Bactrian Greeks. In the Panjab the Shakas had subsequently been eased out by the Kushana, but in Gujarat their Western Satraps had soldiered on. Throughout the late first century AD they ruled, initially as kshtrapas (satraps) of Kushana overlords like Kanishka, then as increasingly independent maha-kshtrapas (great satraps) of Kanishka’s less illustrious successors. To their domains in Gujarat were added parts of what is now Rajasthan, while a satellite satrapy was established north of the Narmada in Malwa (now in Madhya Pradesh). Thence, from Ujjain, Malwa’s ancient capital, the Satraps had become embroiled with their richly trading Shatavahana neighbours in the western Deccan. The Periplus records the Satraps’ occupation of Broach and their blockading of Kalyan under a leader called Nahapana, while, inland, inscriptions in the cave temples of Nasik and Junnar further attest the Shaka presence in Shatavahana territory.

It seems, however, that the Shatavahanas did not long suffer this indignity. Under the great Gautamiputra Satakarni they successfully repelled the Satraps and completely ‘uprooted’ Shaka rule in Malwa. A large hoard of Shaka coins found near Nasik, most of which had been restruck by the Shatavahana king, would seem to confirm this victory. The Satraps were forced back into Gujarat and immediately began planning their revenge. A certain Chashtana, from his coins a wily-looking strategist, was chosen to lead the Shaka forces, and duly established his own satrapal dynasty. The task of restoring the power of the Western Satraps then started in earnest and, according to the Junagadh inscription, had now, in 150 AD, been successfully completed by Chashtana’s grandson, the Great Satrap Rudradaman.

Rudradaman had actually done rather better than that. As well as twice defeating the Shatavahanas and reconquering the whole of Malwa, he claimed to have made extensive acquisitions in Rajasthan and Sind and to have routed the Yaudheyas. The latter were ksatriyas who still followed their hereditary calling as professional warriors and who retained a republican form of government in their territory to the west of Delhi. Presumably Rudradaman encountered them somewhere further south, perhaps in Rajasthan; certainly he did not occupy their homeland. Whereas the claimed conquests of, say, Kharavela of Kalinga positively invite suspicion, Rudradaman’s are generally plausible. He avoids the usual clichés about an empire reaching from the ocean to the Himalayas; not one of his elephants had ever been watered in the Ganga. His coins, mostly silver, describe him simply as ‘Mahakshtrapa’; their royal busts, if we may assume that they are portraits, have been taken to ‘show a man of vivacious and cheerful disposition’.2

The Junagadh inscription, while failing to elaborate on this cheerful disposition, does add much personal detail. Rudradaman staunchly upheld dharma, possibly in imitation of Ashoka, with whose Edicts he was so happy to share rock-space. He was also a fine swordsman and boxer, an excellent horseman, charioteer and elephant-rider, universally praised for his generosity and bounty, and far-famed for his knowledge of grammar, music, logic and ‘other great sciences’. Clearly he aspired to what he took to be an essentially Indian ideal of kingship; and he succeeded so well that thereafter his name (which unlike ‘Maues’ and ‘Azes’ was a decidedly Indian one) was ‘repeated by the venerable … as if it was another Veda demanding assiduous study and devout veneration and yielding the most precious fruit’.3 He also, his inscription claims, wrote both prose and verse which were ‘clear, agreeable, sweet, charming, beautiful, excelling in the proper use of words, and adorned’. Moreover, as if to prove his point, he had taken the novel and perhaps presumptuous decision to have his memorial written in classical Sanskrit. Rudradaman’s Junagadh inscription is in fact ‘the earliest known classical Sanskrit inscription of any extent’.4

The records of Ashoka, Kharavela and Kanishka and all those Shatavahana cave inscriptions are in some form of Prakrit, usually Magadhi or Pali. These were the languages of everyday use which, since their adoption by early Buddhist and Jain commentators, had become the normal medium of record. Much-simplified derivatives of classical Sanskrit, the Prakrit languages have sometimes been unfairly likened to pidgin; after a further stage of adaptation, they would spawn the Indo-Aryan regional languages of today – Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, Panjabi, etc. Sanskrit, on the other hand, remained a prestige language, imbued with sacral powers, reserved mainly for religious and literary purposes, and jealously guarded as well as principally understood by brahmans. Its unexpected emergence as a language of contemporary record in the second century AD, and its subsequent acceptance as the medium of courtly and intellectual discourse throughout India, may be taken as a sure sign of a brahmanical renaissance.

Such would indeed prove to be the case under the Guptas. The great era of all that is deemed classical in Indian literature, art and science was now dawning. It was this crescendo of creativity and scholarship, as much as the unevenly documented political achievements of the Guptas, which would make their age so golden; and it was to the wider use of Sanskrit and the exploration of its myriad subtleties that this awakening owed most.

In the development of languages the classical phase usually precedes the proliferation of vernacular derivatives; thus the Latin of Cicero, Virgil and Horace precedes the vulgarised vernacular from which the Romance languages developed. Sanskrit somehow reversed the process; it was making its great comeback when it should have been dying. Why this happened remains a puzzle. ‘The answer cannot be given in purely cultural terms,’ wrote D.D. Kosambi. A Marxist as well as a brahman, Kosambi sought an explanation in ‘the development of India’s productive systems’ and ‘the emergence of a special position for the brahman caste’.5 Behind the glittering façade of Gupta culture, society was about to undergo the profound changes associated with the Indian version of feudalism. A gradual process of unsensational devolution, it would give a new impetus to the Aryanising primacy of both the brahmans and their language.

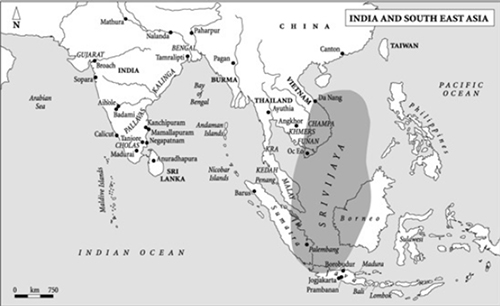

One other linguistic question remains. How was it that Rudradaman and his minister anticipated such a quintessentially classical trend as the triumph of Sanskrit by a couple of centuries, and in an inscription so remotely located that it can have been seen only by a literate few? The suggestion has been made that the Satrap’s use of Sanskrit was ‘a method followed to endear a ruler of foreign descent to the indigenous ruling class’; thus, in the case of Rudradaman, a Shaka, and his deputy Suvisakha, a Parthian, the adoption of Sanskrit and the patronage of those who held it dear was designed to reconcile brahman opinion to a foreign ruler – or as Kosambi puts it ‘to mitigate the lamentable choice of parents on the part of both Satrap and governor’.6 This seems plausible and is generally accepted in respect of the Sanskrit inscriptions soon to be composed by, or for, Indophil rulers in Sumatra, Java, Indo-China and other parts of Indianised south-east Asia. The employment of a prestige language lent distinction and authority even to non-Indic dynasties. One wonders why, though, if Sanskrit offered such ready legitimacy it was not also adopted by the earlier Shakas or the contemporary Kushanas.

However objectionable to north Indian pride, the possibility must remain that in a little-regarded region of the subcontinent long-Indianised dynasts, albeit originally of foreign extraction, could actually have pioneered and popularised such a cardinal feature of the classical Indian tradition. Aryanisation was, as will appear, a two-way process; and many other cultural achievements associated with the Gupta age cannot readily be ascribed to Gupta rule. To the emerging ‘Great Tradition’ of Hinduism, borrowing from the subcontinent’s far-flung store of local custom and innovation was quite as natural as banking on the Indo- Aryan orthodoxies of the Gangetic heartland.

But the history of India’s so-called ‘regions’ (Gujarat, Bengal, Tamil Nadu and so on) is still today in its infancy. Habitually disparaged as divisive, ‘regional’ history has few champions in the Senior Common Rooms of power. Untypical and brave are the scholars who insist that Rudradaman of Gujarat did himself write such ‘clear, agreeable, sweet, charming, beautiful’ and altogether excellent Sanskrit; or that under the Satraps’ patronage classical Sanskrit was actively promoted (as is further suggested by its appearance in the donative inscription of a Shatavahana queen who was of Satrapal birth); or that ‘the Shakas had shown the way by using Sanskrit in their inscriptions … [and] the Guptas only perpetuated the tradition when they came to power.’7

THE ARM OF THE GUPTAS

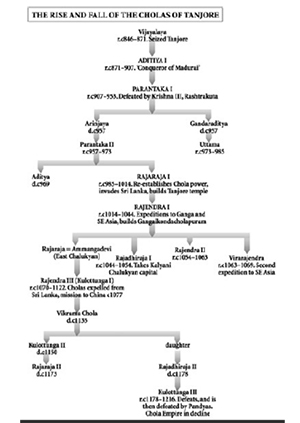

History, whatever its parameters, is said to repeat itself. Seldom, though, does it oblige so readily as with the creators of ancient India’s two greatest dynasties. A Chandragupta had founded the Mauryan empire in c320; just so did a Chandragupta found the Gupta dynasty in c320. It could be confusing. But the first date was, of course, BC, the second AD; and to clarify matters further, the Gupta Chandragupta is often phonetically dismembered as ‘Chandra-Gupta’ or ‘Chandra Gupta’. Unfortunately there would be another Gupta Chandra-Gupta. The founder of the Gupta dynasty is therefore designated as Chandra-Gupta I – which naturally brings to mind the Mauryan Chandragupta. (Here the Gupta founder will be called Chandra-Gupta I and his Mauryan counterpart Chandragupta Maurya.) Coincidence, however, continues. As well as a name, the Gupta founder shares with his Mauryan predecessor a shadowy profile, a reputation for important but doubtful conquests, and the misfortune of being hopelessly upstaged by a more illustrious successor – Ashoka in the case of Chandragupta Maurya, Samudra-Gupta in the case of Chandra-Gupta I.

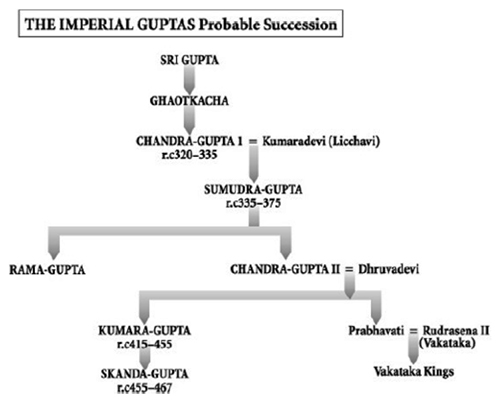

Of earlier Guptas before Chandra-Gupta I, a Sri Gupta and a Ghatotkacha Gupta are listed in inscriptions. The former would be remembered solely for having endowed a place of worship in Bihar for Chinese Buddhists. By the third century AD the first Chinese monks had begun trickling back along the Karakoram route to tour the sites associated with the Buddha’s life. For these foreign pilgrims to the Buddhist ‘Holy Land’ Sri Gupta built a temple; when first noticed in the fifth century, it was already in ruins. Sri Gupta was probably not a Buddhist but was raja of some minor polity near or within erstwhile Magadha. He was succeeded by his son Ghatotkacha. Their origins are unknown; their caste may have been vaisya.

Chandra-Gupta I was Ghatotkacha’s son. He is regarded as founder of the dynasty partly because he assumed a new title, partly because later Gupta chronology is calculated from what is taken to be the date of his accession (320 or 321 AD), and partly because by marriage or conquest he acquired more territory and authority than he inherited. The new title was Maharajadhiraja, ‘great raja of rajas’, an Indian adaptation of the Persian ‘king of kings’ as previously adopted by the Kushanas. Its assumption seems premature, but lofty titles and epithets would be important to the Guptas. They would soon up the stakes to paramaharajadhiraja and even rajarajadhiraja, ‘king of kings-of-kings’.

Presumably the title reflected growing ambitions. Chandra-Gupta I was the first of his line to feature on coins. According to the Puranas, his territory stretched along the Ganga from Magadha (southern Bihar) to Prayaga (the later Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh). Whether he conquered this rich swathe of the Gangetic heartland and, if so, from whom, is not known. Magadha, for instance, or part of it, may have come to him as a marriage settlement. Kumaradevi, his chief queen, was a Licchavi and so a descendant of one of those 7707 Licchavi knights-raja who had been defeated by Ajatashatru seven hundred years previously. The Licchavis had a distinguished pedigree which was doubtless highly desirable to unknowns like the Guptas. But the importance the Guptas attached to this union was of an altogether higher order. Chandra-Gupta I’s successor would style himself not ‘son of a Gupta father’ but ‘son of a Licchavi daughter’. There are even coins showing king and queen together, an unprecedented development; they bear, as well as the king’s name, that of ‘Kumaradevi Licchavayah’. It is known that the Licchavis had acquired territory in Nepal and it may be that ‘they had taken possession of Pataliputra, the city which had been built and fortified many centuries earlier for the express purpose of curbing their restless spirit.’8 Certainly it is probable that the Guptas and the Licchavis ruled adjacent territories ‘and that the two kingdoms were united under Chandra-Gupta I by his marriage with Kumaradevi’.9

The Imperial Guptas: Probable Succession

Only under their son Samudra-Gupta does the dynasty emerge from obscurity. Once again this is mostly thanks to the survival of a single inscription. Like Kharavela’s, it advances extravagant claims, but, like Rudradaman’s, these claims are substantiated by other epigraphic and numismatic evidence. The inscription is probably the most famous in all India. Written in a script known as Gupta Brahmi (more elaborate than Ashoka Brahmi), and composed in classical Sanskrit verse and prose, its translation is often credited to James Prinsep of Ashoka fame, although it had been known and partially translated by earlier scholars. Its idiom and language echo that of Rudradaman. So does Samudra- Gupta’s choice of site; for as if aspiring to Mauryan hegemony, his panegyric appears as an addition to the Edicts of Ashoka on one of those highly polished Ashokan pillars.

The pillar stands in the city of Allahabad where, soon after Prinsep’s death, another Ashokan pillar, or part of it, was found in the possession of a contractor who used it as a road-roller. British antiquarians were mortified. A similar fate had almost befallen the pillar with the Samudra-Gupta epigraph. It had been uprooted in the eighteenth century and was discovered by Prinsep’s colleagues lying half-buried in the ground. They re-erected it on a new pedestal and designed an Achaemenid-style replacement for its missing capital. Supposedly a lion, the capital ‘resembles nothing so much as a stuffed poodle on top of an inverted flower pot’, wrote Alexander Cunningham, the father of Indian archaeology in the nineteenth century.

Cunningham also deduced that the Allahabad column had been shifted once before. Evidently later Muslim rulers had come to see these spectacular monoliths as a challenge to the excellence both of their sovereignty and their transport. They had therefore attempted to relocate them as totemic embellishments to their palatial courts. The truncated pillar which now tops Feroz Shah’s palace in Delhi originally stood near Khizrabad higher up the Jamuna. A contemporary (thirteenth-century) account describes how it was toppled onto a capacious pillow, then manoeuvred onto a forty-two-wheeler cart and hauled to the river by 8400 men. Lashed to a fleet of river transports, it was finally brought to Delhi in triumph.

Just so, the Allahabad pillar had apparently been shifted downriver from its original site in Kaushambi. It was meant to enhance the pretensions of the Allahabad fort as rebuilt by the Mughal emperor Akbar in the late sixteenth century. Akbar’s son Jahangir would add his own inscription to those of Ashoka and Samudra-Gupta; and thus it is that scions of each of north India’s three greatest dynasties – Maurya, Gupta and Mughal – share adjacent column inches in the heart of Allahabad, a city whose further claim to fame is as the home of a fourth great dynasty, that of the Nehru-Gandhis.

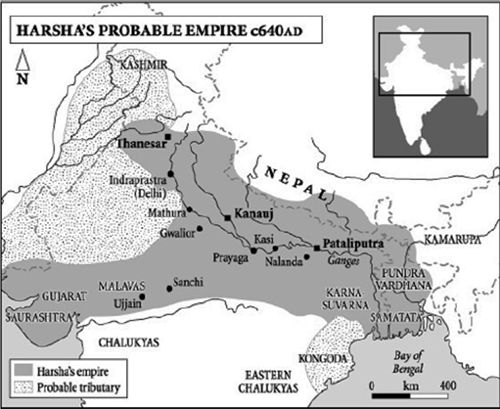

Miraculously, all that shunting around of the Allahabad pillar little damaged its inscriptions. That of Samudra-Gupta, if not posthumous, dates from near the end of his reign, which was a long one. He is thought to have succeeded as maharajadhiraja, or been so nominated by his father, in c335, and to have died in c380. The inscription may therefore be of about 375 and, with forty years’ achievements to cover, it has much to tell. The most important sections consist of long lists of kings and regions subdued by ‘the prowess of his arm in battle’, otherwise ‘the arm that rose up so as to pass all bounds’; indeed the pillar itself ‘is, as it were, an arm of the earth’ extended in a gesture of command.10 Some historians take these strong-arm conquests to be arranged in chronological order and, on that basis, have divided them into separate ‘campaigns’. Thus the first campaign seems to have taken Samudra-Gupta west where, with the strength of his arm, he ‘uprooted’ kingdoms in the Bareilly and Mathura regions of what is now Uttar Pradesh and in neighbouring Rajasthan. These were incorporated into the Gupta kingdom.

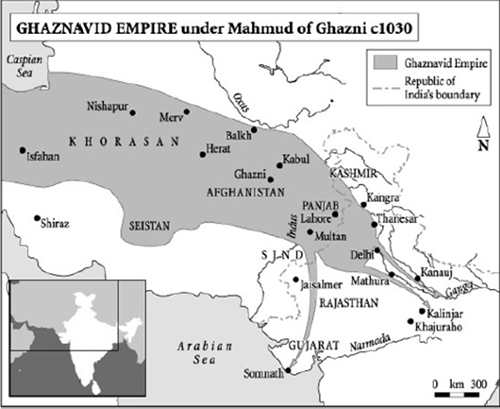

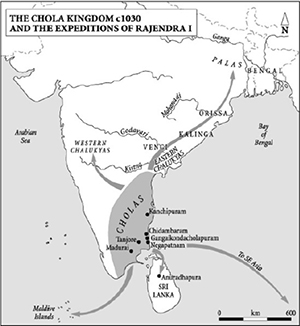

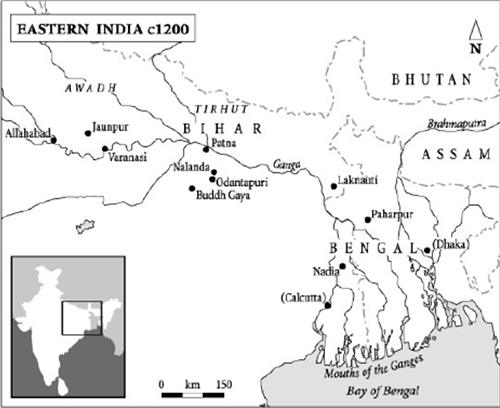

Next he headed south down the eastern seaboard and, perhaps in the course of several campaigns, elbowed aside a dozen more rivals. He turned back only after capturing Vishnugopa, the Pallava king of Kanchipuram (near Madras). Further campaigns in the north saw Gupta forces overrunning most of Bengal, ‘exterminating’ independent republics like that of the Yaudheyas west of Delhi, and establishing Gupta rule throughout the ancient arya-varta (the Aryan homeland – roughly the modern states of West Bengal, Bihar, UP, Madhya Pradesh and the eastern parts of Rajastan and the Panjab). This became the core region of Gupta rule, within which numerous tribal peoples were also deprived of their autonomy and where most extant inscriptions of the early Guptas have been found. Further afield the Kushanas in Gandhara, Great Satrap Rudradaman’s descendants in Gujarat and Malwa, various rulers in Assam and Nepal, and the kings of Sri Lanka and ‘other islands’ (which could mean the Indianised kingdoms of south-east Asia) are all said to have acknowledged Samudra-Gupta’s sovereignty and to have solicited his favour with deferential missions, handsome gifts and desirable maidens.

Now indisputably ‘the unconquered conqueror of unconquered kings’, Samudra-Gupta stood on the threshold of a pan-Indian empire. Other favourite epithets describe him as ‘conqueror of the four quarters of the earth’ and ‘a god dwelling on earth’. He performed the horse-sacrifice; 100,000 cows were distributed as gifts, presumably to his brahman supporters. His coins reveal Vaishnavite leanings but, as a world conqueror, he was seen not just as a devotee of Vishnu but as an emanation or incarnation of that deity. Universal dominion was his. Besides the Garuda symbol of Vishnu, some of his coins feature the one-umbrella of a samrat. Its welcome shade was seen to engulf the political landscape as he turned the cakravartin’s wheel of world-rule.

Gupta Conquests

But what kind of empire was this? Not, it seems, a continually intrusive one. Gupta rhetoric had perhaps outstripped reality; alternatively its richly allusive phrasing may simply have been misinterpreted. For a close scrutiny of Samudra- Gupta’s rule reveals little of the bureaucratic interventionism associated with Mauryan empire; and despite the best efforts of patriotic scholarship, the claims advanced by zealous nationalists about his ‘unifying India’ and arousing a nation are hard to sustain. He may indeed have been ‘a man of genius who may fairly claim the title of the Indian Napoleon’;11 the Allahabad inscription certainly refutes the idea that only foreigners have conquered India. But it was a conquest to little lasting political purpose other than dynastic gratification. Just as the celebrity of the Guptas was only perceived after the translation of the Allahabad inscription in the nineteenth century, so a deeper design for their empire was only discovered in the twentieth century. ‘Far from the Guptas reviving nationalism it was nationalism that revived the Guptas,’ writes Kosambi.12

In such championship, Indian nationalism reveals as much about its own ambiguities as about those of the Guptas. Thus we learn that Samudra-Gupta ‘was not moved by a lust for conquest for its own sake. He worked for an international system of brotherhood and peace replacing that of violence, war and aggression.’13 A less likely candidate for the Gandhian mantle of nonaggressive satyagrahi it would be hard to find. Nor is this a very convincing explanation for Samudra-Gupta’s failure to consolidate his conquests. In the Deccan and elsewhere beyond the frontiers of his Gangetic arya-varta, he had made no attempt at annexation. ‘Uprooted’ kings were reinstated, their territories restored, and the Gupta forces withdrawn. A one-off tribute was exacted and on this the Gupta court waxed wealthy, with conspicuous patronage of the arts and a prolific output of the beautifully minted gold coins to which the Guptas first owed their ‘golden’ reputation. But unlike the directly administered empire of the Mauryas, this was at best a web of feudatory arrangements and one which, lacking an obvious bureaucratic structure, left the sovereignty of the feudatories largely intact.

In the fourth century BC the Mauryas had been able to extend their rule into politically virgin territories where state-formation, if it existed at all, had been in its infancy. Ashoka had carefully noted several foreign kings in his inscriptions but within India he found not one sovereign worthy of being so named; the ‘Cholas’ and ‘Keralaputras’ were families or clans; even Kalinga was just a place and a people. In such a vacuum, Mauryan empire had a pioneering quality and was necessarily one of agricultural settlement, administrative decree and fiscal organisation.

Six hundred years later the Guptas may have found a similar situation in Bengal and have pursued similar policies there. Elsewhere they faced more advanced opponents who were already administering their own states and taxing their own subjects. The submission of all these now carefully named and previously unconquered kings was, of course, most gratifying; ‘the Beloved of the Gods’ had been merely a raja, a ‘king’; the Guptas were maharajadhirajas, ‘kings of kings’. On the other hand they also recognised the difficulty of trying permanently to engross such distant and confident kingdoms. It was more expedient to content themselves with the rich pickings of conquest and to retain the option of perhaps repeating this feat when more such pickings had accumulated.

It also seems that the criteria associated with the status of cakravartin did not include sustained government or direct control. In the case of distant rulers a nominal submission looks to have been sufficient, while of those nearer at hand regular attendance on the cakravartin was also required. As will emerge, a world-ruler did not actually have to rule the world; it was enough that the world should acknowledge him as such; in fact his status as a maharajadhiraja was dependent on the survival of rajas, both within and beyond his arya-varta, who were powerful enough to justify the title. ‘The point here was not to do away with other kings as such and produce a single, absolute kingship, blessed by a monotheist deity, for all India.’ Tributary rajas, or kings, were essential as validating and magnifying agents. In the same way as local cults and lesser deities were harnessed to the personae of Lords Vishnu or Shiva, so lesser rulers were inducted into an enhancing relationship with the ‘world-ruler’. Precedence and paramountcy were what mattered, not governance or integration. ‘What distinguished an imperial court politically, and especially one whose king claimed to be the universal king of India, was that it was primarily a society of kings.’14

Samudra-Gupta’s immediate successors maintained his elevated status and continued his policies. No inscription as detailed as the Allahabad testimonial is available for any of them, but from minor inscriptions, coins and literary sources it is clear that the Gupta ‘empire’ now climbed to its ambiguous zenith. There were, however, setbacks and compromises. A sixth-century drama tells of a Rama-Gupta who is thought to have briefly succeeded Samudra-Gupta and who attempted to ‘uproot’ the Western Satraps in Malwa.15 The attempt went badly wrong. Rama-Gupta was defeated and, when he tried to disengage, he was informed that the price of escape would be the surrender of his queen. According to a much later biography, the Shaka Satrap sorely coveted the lovely Queen Dhruvadevi. No doubt she had been represented to him as lotus-eyed, with thighs like banana stems, and all the other ripe attributes of desirable womanhood as detailed in textual tradition and epitomised in the yaksi temptresses of Mathura and Sanchi sculpture. Aflame with desire, ‘the lustful Shaka king’ was adamant; Rama-Gupta, hopelessly unworthy of such a desirable consort, conceded defeat and agreed to hand her over.

But the ignominy was too much for Rama-Gupta’s younger brother. The latter somehow disguised himself as the shapely Dhruvadevi, was duly given entry to the enemy camp, and promptly slew the Satrap. He must also have made his escape for, Rama-Gupta having been irrevocably disgraced by this affair, it was the righteous brother who now took over the reins of empire as Chandra-Gupta II. He may have had to kill Rama-Gupta in the process; more certainly it was he who eventually claimed the hand of Dhruvadevi.

Not surprisingly Chandra-Gupta II’s main offensive was a continuation of this struggle against the Shaka Satraps. Judging by inscriptions in and around Sanchi he seems to have been in eastern Malwa for some years, presumably while he conducted the necessary campaigns. Patience was eventually rewarded. By the year 409 Chandra-Gupta II was issuing silver coins to replace those of the Satraps. The Shaka territories in western India had been annexed to those of the Guptas, and of the Western Satraps no more is heard.

The Guptas thus secured their western frontier and inherited whatever remained of the cultural traditions established by the Sanskrit-loving Rudradaman and his successors. On the evidence of a Buddhist site in northern Gujarat (Devnimori) which may date to about 375, it has been suggested that Gupta sculpture and architecture owed several motifs and design features to western India. It may also be significant that the cultural achievements usually associated with the Guptas are little in evidence in the fourth century and only become established after Chandra-Gupta II’s conquest of the Satraps.

Success against the Satraps also gave the Guptas access to the ports of Gujarat and to the profits of its international maritime trade. There and throughout central India, just as the Satraps had once become embroiled with their Shatavahana trading neighbours, so the Guptas became involved with the Vakatakas, the dynasty which had succeeded the Shatavahanas as the dominant power in the Deccan. For once, war was not the outcome; perhaps the campaigns against the Satraps were taking their toll. Instead, the Guptas opted for a dynastic alliance whereby Chandra-Gupta II’s daughter was married to Rudrasena II, the Vakataka king. The latter soon died and during the ensuing regency (c390–410) it was Prabhavati, this Gupta queen, who as regent controlled the Vakataka state in accordance with Gupta policy. Thereafter the Vakatakas continued as allies and associates of the imperial Guptas.

Other dynastic pairings suggest that the Guptas often made intelligent use of the prestige which attached to the maharajadhiraja’s bed-chamber. Prabhavati was Chandra-Gupta II’s daughter not by the coveted Dhruvadevi but by a princess of the Naga dynasty. This was an ancient lineage which seems to have re-established itself in Mathura and other parts to the west and south of the Jamuna in the wake of Kushana retraction. Since Samudra-Gupta had earlier ‘violently exterminated’ the Naga king, it would seem that marriage was used to consolidate existing acquisitions as well as to neutralise external rivals.

Chandra-Gupta II, like his predecessor Samudra-Gupta and his successor Kumara-Gupta, reigned for about forty years. Such longevity over three generations is exceptional and must have been another important factor in the stability of Gupta rule. Of further Gupta feats there is little evidence, the only notable exceptions being a doubtful record of far-flung campaigns by Chandra- Gupta II and an important defensive role undertaken during the reign of Kumara- Gupta.

The former, the campaigns sometimes attributed to Chandra-Gupta II, are recorded in a short inscription engraved on a pillar located at Mehrauli, once a village on the outskirts of Delhi. The pillar, unlike the stone pillars, or lats, of Ashoka, is made of iron, and the village is better known as the site where Delhi’s twelfth-century sultans would build the renowned Qutb minar and mosque. It is in fact the famously rust-resistant ‘Iron Pillar’ which now stands in the main courtyard of the mosque and attracts hordes of visitors, many of them convinced that wish-fulfilment awaits those whose arms are long enough to embrace its trunk. Fortunately out of reach, as it might otherwise have been erased by this activity, the inscription commemorates the erection of the pillar as ‘a lofty standard of the divine Vishnu’. Its donor was one ‘Chandra’, supreme world conqueror ‘on whose arm fame was inscribed by the sword when in battle in the Vanga countries’ and who, having ‘crossed in warfare the seven mouths of the [river] Sindhu’ defeated the ‘Vahlikas’. He also perfumed the breezes of the southern ocean with his prowess. Unfortunately no date is mentioned and, worse still, there is no sign of the word ‘Gupta’. ‘Chandra’ could therefore as well have been a Chandra-sena or a Chandra-varman, both attested kings of the period. And if a Chandra-Gupta, which one? Straining for clarification, scholars, even long-armed epigraphists, find their wishes unfulfilled. The identity of this fragrant ‘Chandra’ remains a mystery, as does the technology which enabled Guptan smelters to cast an iron obelisk of such rust-resistant purity that sixteen hundred monsoons have scarcely pitted its surface or defaced its inscription.

There is also doubt about this Chandra’s listed conquests. ‘Vanga’, like Anga, was an ancient janapada in west Bengal; the ‘Sindhu’ is usually the Indus; and the ‘Vahlikas’ have been taken to be the Bactrians. But military successes at such distant poles of the subcontinent strain credulity. In the west no corroborative evidence of Gupta intervention beyond the Indus, let alone beyond the Hindu Kush, is available. However, most of Bengal definitely was within the Gupta ambit. In fact the Guptas were the first north Indian dynasty to extend their rule into and across the heavily forested maze of swamps and waterways that was the Ganga-Brahmaputra delta. Hitherto little exposed to Aryanising influences except along its western seaboard, nearly all of Bengal was now claimed by the Guptas, and it seems reasonable to suppose an accelerated process of drainage, clearance and settlement. From the ruins of the Gupta empire would emerge east and central Bengal’s first historical states, amongst which Vanga would be eminent.

Kumara-Gupta, who ruled from c415 to c455, faced a different challenge. In his reign there seems to have been a major uprising in Malwa by one Pushyamitra. Briefly, in the words of the only inscription which refers to it, it ‘ruined the fortunes of the Gupta family’. Soon after there first appeared on the Indian scene the Hunas, otherwise described as a new breed of mlecchas (incomprehensible foreigners). These newcomers were a branch of the Hiung-nu of Chinese history and the Huns of European history. In a new wave of central Asian displacement, an offshoot of this horde, the Ephthalites or White Huns, had established themselves in Bactria in the late fourth century (thus making a Gupta conquest there unlikely). In the mid-fifth they followed their Yuehchi/ Kushana predecessors across the Hindu Kush and into Gandhara, and thence they pushed east against the Guptas.

Fortunately the Guptas produced a champion worthy of the occasion. In one inscription Skanda-Gupta, a son of Kumara-Gupta, is described as ‘subsisting like a bee on the wide-spreading water-lilies which were the feet of his father’. The bee, though, had a sting. It was Skanda-Gupta who took the field successfully against the upstart Pushyamitra. He then made good a doubtful claim to succeed his father. And finally, if only temporarily, he repulsed the Huns. It was also during the reign of Skanda-Gupta, he who ‘made subject the whole earth bounded by the waters of the four oceans and full of thriving countries round the borders of it’, that the last major addition was made to the great rock outside Junagadh in the Saurashtra peninsula. Following the inscriptions of Ashoka and Rudradaman, this third inscription tells of Skanda- Gupta’s governor in Gujarat and of his son. Both paragons of virtue, they built a massive embankment when Rudradaman’s reservoir was in its turn overwhelmed by floodwaters, and they also added a temple.

But if the temple was meant to guarantee the dam’s future security, it failed. Not even a trace of the irrigation system which prompted this unique series of inscriptions beneath the crags of Girnar remains. The rulers of Saurashtra soon deserted Junagadh, perhaps after another disastrous flood, and by 500 a new capital had been established at Vallabhi in the east of the peninsula. Only the hump-backed rock, converted into a book ‘by the aid of the iron pen’, still mutely protests the majesty of Junagadh’s distinguished benefactors.

A similar fate, redeemed only by the tenacity of tradition, now overtook the Gupta empire. After the death of Skanda-Gupta in c467, his nephew Budha- Gupta, then another nephew, his son and then his grandson continued to claim world dominion well into the sixth century. But their reigns were mostly brief and it is clear that by 510 other Guptas, who may or may not have been related to them, operated as independent rulers within the core area of the erstwhile empire. In that year the Huns, led by a formidable leader called Toramana, were again on the move. They overran Kashmir and the Panjab and defeated a Gupta army near Gwalior, thus extending their rule to Malwa. In the face of such disarray, even the fiction of the Guptas’ universal sovereignty was unsustainable. Their golden reputation fades from history as the famous gold coinage, debased under Skanda-Gupta, becomes crudely cast, increasingly stereotyped, of rare occurrence, and then non-existent.