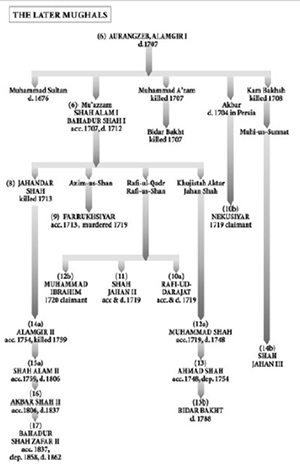

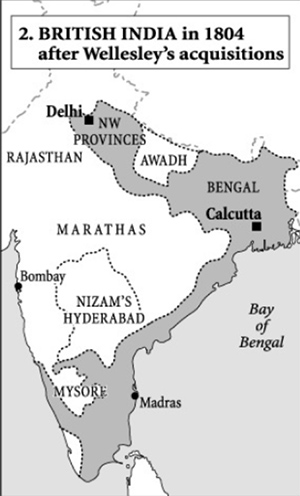

13. The Making of the Mughal Empire: 1500–1605

BABUR GOES TO INDIA

ON 5 JULY IN THE YEAR 1505 a violent earthquake hit the city of Agra. According to Ferishta, ‘so severe an earthquake was never experienced in India either before or since … Lofty buildings were levelled with the ground [and] several thousand inhabitants were buried under the ruins.’1 To the survivors it seemed like an omen. Sikander, the second and greatest of the three Lodi sultans of Delhi, had in the preceding year celebrated his recovery of some of the sultanate’s erstwhile territories by designating Agra as his alternative capital. A small town of no previous importance, its elevation also signified Lodi ambitions to subdue rivals to the south of Jamuna. The town had been replanned round a grand fort and ‘the foundations of the modern Agra were laid.’2

Their almost immediate destruction by the earthquake made no impression on Sikander Lodi. Heedless, he resumed the creation of his new capital and continued to hammer away at his nearest rajput rival. This was Raja Man Singh of Gwalior whose subsidiary fortress of Narwar was indeed taken. But before the beetling cliffs of the superbly fortified palace-citadel at Gwalior itself, the Lodi forces, lacking artillery, proved powerless. At enormous cost the siege dragged on for several years. Worse still, word of the Lodi’s discomfiture reached the ear of a young and ambitious new Mongol ruler in Kabul.

Zahir-ud-din Muhammad, otherwise known as Babur or ‘the Tiger’, was already showing an unhealthy interest in the disturbed affairs of the Panjab, which province bordered his Afghan kingdom and was nominally under Lodi rule. In 1505, the year of the earthquake, he made his first foray across the northwest frontier. It was another omen which the Lodi sultan chose to ignore. Babur drew his own conclusion. As the Lodis’ biographer puts it, ‘Sikander Lodi, while fighting against the Tomars [i.e. the rajputs of Gwalior], was criminally neglecting the north-west frontier and the Panjab.’3

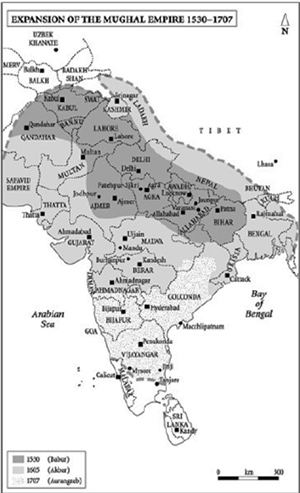

This state of affairs, if anything, worsened as the strife-torn Lodis squabbled amongst themselves. Twenty years and five exploratory incursions later, Babur would invade in earnest, topple Sikander’s successor and, taking both Delhi and Agra, would inaugurate in India a Mongol, or Mughal, empire. Conventionally known in English as that of the Great Mughals, it would wax supreme for two centuries and engross most of the subcontinent. Through the agency of Babur, first of the Great Mughals, the multilateral history of the Indian subcontinent begins to jell into the monolithic history of India.

In his Babur-nama, a personal memoir-cum-diary of such disarming frankness that it was once reckoned ‘amongst the most enthralling and romantic works in the literature of all time’,4 Babur leaps from the page with the zestful energy of a sowar (trooper) bounding into the saddle. Restless to the point of nomadism, he was a born adventurer to whom success was an ultimate certainty and failure but a temporary inconvenience. Publicly he never hesitated. Deliberation inspired decision; decision guaranteed action. Convivial and charismatic, he rejoiced in the adulation of his comrades much as did his adored English contemporary, the young Prince Hal. Yet while ambition and obesity would stifle all scruple in Henry VIII, Babur continued to nurse both a sensitive spirit and the rawest of consciences. In a career that speaks volumes for his courage and genius, it is this emotional frailty which is so remarkable. A succinct piece of versification seemingly gave him as much satisfaction as a well-worked cavalry manoeuvre. Ill health he often reckoned a penalty for past vanities and, though a mighty toper, long and often did he groan over the sinfulness of intoxicants. For his greatest battle he would prepare by finally forswearing alcohol and promoting prohibition. No less typically would the aroma of a musk melon, dewily redolent of his central Asian home, reduce him to a moist-eyed reverie of nostalgic abandon.

To such an adventurer direction was dictated as much by fate as by forebears. On his mother’s side Babur was a distant descendant of Ghenghiz Khan, and on his father’s he was a fifth-generation descendant of Timur, he who in 1398 had sacked the Tughluqs’ Delhi. This latter conquest would furnish Babur with a cherished but highly dubious claim to legitimate sovereignty in northern India. But India was not his first choice. Nor was Kabul. His inheritance lay much further north beyond the Oxus in Ferghana, a minor kingdom to the east of the modern city of Tashkent. He had been born there in 1484 and, though of Mongol blood, it was in the Turkic and Islamic milieu of this subordinate kingdom of Timur’s erstwhile empire that he was educated. Turki would remain his first language; he even wrote of himself and his followers as Turks. His Islam was a robust, workaday faith tempered more by the winds of circumstance and the exigencies of campaigning than by the niceties of theology. And it was to Samarkand, Timur’s capital and the cultural focus of central Asia, that he aspired. Briefly, aged fifteen, he actually occupied it, but was quickly dispossessed by an Uzbeg rival. Twice more he would take the city and twice more he would lose it. Kabul, on the other hand, was just a distraction. Yet for a virtual fugitive it offered consolation. From Afghanistan Timur himself had launched his bid for Samarkand and had then gone on to conquer much of Asia. Babur could do worse. In 1504 he crossed the Oxus, then the Hindu Kush, and seized Kabul.

Apart from that one ominous raid across the Indian frontier in 1505, Babur spent the next fourteen years securing his position in Afghanistan and chasing the dream of sovereignty in Samarkand. In his memoir, which was written towards the end of his reign, he insists that ‘my desire for Hindustan remained constant’. Yet it was not until 1519 that he resumed the quest and not until 1525 that he launched his successful bid. He did so with a highly mobile force which had shared his exploits in central Asia and which, as it was ferried across the Indus north of Attock, was carefully counted. ‘Great and small, good and bad, retainer and non-retainer, [it] was written down as twelve thousand.’ For the task in hand so modest a force must have seemed pitifully inadequate. But in the interim two factors had greatly emboldened him.

One was the acquisition and potential of firearms. In the new gunpowder technology, as in much else, Babur’s Lodi adversaries lagged behind the kingdoms and sultanates of the Deccan and the south; there is no evidence to suggest that their forces were acquainted with either cannon or matchlocks. He, on the other hand, had both. Though personally more proficient at archery, he had studied the use of artillery in central Asia, had recruited Turkish gunners, and now took a close interest in the casting of siege-cannon and the transport of field guns. On a previous raid into the Panjab the sharp-shooting potential of matchlocks had also impressed him. For what his forces lacked in numbers they compensated with a capacity, terrifying alike to man, horse and elephant, for deafening and increasingly lethal bombardments.

The other consideration which worked in his favour was the now terminal rivalry amongst his enemies. Sikander Lodi had been succeeded by two sons who, on the insistence of the Lodis’ fractious power-brokers, had divided the sultanate between them. Ibrahim, inheriting Delhi, had since overcome his brother in Jaunpur but had thereby alienated the most senior nobility and alarmed Indian rivals like the rajput chief, Rana Sangha of Mewar. The latter now encouraged Babur with offers of collaboration against the Lodis, while in 1523 it had been the Lodis’ own governor in the Panjab who had invited Babur to capture Lahore and challenge for the sultanate. This man, Daulat Khan, had since changed his mind and now threatened to oppose the invasion, although other Lodis, including his own son, continued to back Babur.

In the event the twelve thousand Mughals advanced across the Panjab’s rivers unopposed. Near the city of Lahore Daulat Khan, old though he was, donned a couple of swords and bragged about halting the invader. ‘Was such a rustic blockhead possible!’ scoffed Babur. ‘With things as they were, he still made pretensions!’5 When the old man then sheepishly surrendered, Babur ordered him to submit on bended knee with his ridiculous swords dangling round his neck. Milking the moment for mirth rather than vengeance, Babur then pressed on to Rupar, Ambala and Delhi.

I put my foot in the stirrup of resolution, set my hand on the rein of trust in God, and moved forward against Sultan Ibrahim … in the possession of whose throne at that time were Delhi, the capital, and the dominions of Hindustan, whose standing army was rated at a lakh (100,000) and whose elephants and whose begs’ [nobles’] elephants were about 1000.6

The same figures are given for the host with which Ibrahim now moved out from Delhi to oppose him. Although Babur says that his own forces had, if anything, shrunk during their progress across the Panjab, they had also been supplemented by Lodi deserters. When in April 1526 the two armies met at Panipat, eighty kilometres due north of Delhi, Ibrahim is thought to have still enjoyed a numerical advantage of about ten to one.

Babur was not discouraged. For the Lodi he had nothing but contempt. Ibrahim was a novice who knew little of battle-craft, ‘neither when to stand, nor move, nor fight’. After a week-long stand-off he had to be prodded into action by Mughal raiders; he then moved forward without guile or stratagem. Babur awaited him in a carefully chosen formation with the close-packed walls of Panipat on one flank and an ambuscade of brush on the other. Seven hundred carts, commandeered in the neighbourhood, were lashed together across his front with matchlock-men sheltering between them and gaps every hundred metres for the cavalry to charge from. Additional flying columns were held in reserve. As soon as battle was joined they swung round the enemy’s flanks and pressed hard from the rear. Ibrahim had no room to manoeuvre. Despite repeated charges, he failed to break through the cordon of carts. His forces became ever more compacted, the wings falling back on the centre, unable either to advance or withdraw. That very numerical supremacy which should have overwhelmed the Mughals now overwhelmed the Lodis. ‘By God’s mercy and kindness this difficult affair was made easy for us,’ recalled Babur. ‘In one half-day that armed mass was laid upon the earth.’ The most conservative estimate put the slain at fifteen thousand; amongst them was Ibrahim himself.

Hot in pursuit of survivors, Babur headed for Delhi while Humayun, his son, was ‘to ride light and fast for Agra’, there to secure the Lodi capital and treasury. Amongst those sheltering in Agra Humayun found Ibrahim’s mother and also the family of raja Vikramaditya of Gwalior. Gwalior had finally submitted to the Lodis in 1519; Vikramaditya, Man Singh’s successor, had thus become a Lodi feudatory and, fighting under Ibrahim at Panipat, had been duly ‘sent to hell’. It was supposedly to curry favour with the conqueror that his family now made a ‘voluntary offering [to Humayun] of a mass of jewels and valuables amongst which’, notes Babur, ‘was the famous diamond which Ala-ud-din must have brought’. The weight of this stone he gives as eight misqals, perhaps 186 carats, and its value as equivalent to ‘two and a half days’ food for the whole world’. If the Ala-ud-din in question was the Khalji sultan, the diamond had presumably been obtained during that ‘Aladdin’s’ Deccan campaigns, since the main diamond fields were in Golconda (Hyderabad). How it came into the possession of the Gwalior rajas is not known; but many experts think that this notice in the Babur-nama constitutes the first reference to the famous Koh-i-Nur, ‘the mountain of light’, a gem credited with conferring on its owner either rulership of the world or imminent extinction, depending on how its erratic history is read. It is also sometimes called ‘Babur’s diamond’, although the first Mughal never actually claimed it. Humayun did offer it to him but, perhaps wisely, Babur declined: ‘I just gave it back to him.’7

For far from being any kind of world-ruler, Babur, although now possessed of the Panjab, Delhi and Agra, was in a critical situation. It was one thing to defeat the unloved Ibrahim, quite another to secure the submission of the unruly Afghan nobles who had poured into India at the invitation of the Lodi sultans and amongst whom the Lodi territories were now parcelled out. The populace of even Agra was openly hostile and, ‘Delhi and Agra excepted, not a fortified town … was in obedience.’ The entire Doab was in enemy hands; so were Aligarh, Bayana and Dholpur, all within easy striking distance of Agra.

Babur’s situation was further worsened by growing dissatisfaction within the ranks of his own forces. India had few charms for a God-fearing Mughal beg . In a long inventory wherein he reveals as much enthusiasm for India’s birds as for its revenues, Babur candidly lists the country’s defects: ‘no good horses, no good dogs, no grapes, musk-melons or first-rate fruits, no ice or cold water, no good bread or cooked food in the bazaars, no hot-baths, no colleges, no candles, no torches, and no candlesticks.’ Perhaps his men could have managed without candlesticks, but amongst what Babur dubbed an unattractive, unsociable, uncouth and exceedingly numerous race of infidels they could never live at ease. In short, like Alexander’s Macedonians, Babur’s Mughals had had enough. It was May, one of the hottest and dustiest months of the north Indian year. Honours had been won, booty had been secured and vast amounts of treasure distributed. A more successful raid could scarcely have been hoped for. Now all they wanted was to return to their homes and families, to drink the cooler air of Kabul and in due course resume the struggle for Samarkand.

Babur, like Alexander, remonstrated with them. Sovereignty, he said, depended on the possession of resources, revenues and retainers. After long years of struggle and at appalling risk they had at last obtained such things: broad lands, infinite wealth and innumerable subjects were awaiting their command; who would seriously abandon such plenty for ‘the harsh poverty of Kabul’? A close friend, who was also one of his most senior commanders, would do just that. Babur let him go, and took less exception to his departure than to the parting couplet he had daubed on his house: ‘If safe and sound I cross the Sind,/Blacken my face ere I wish for Hind.’ Most, however, stayed. Babur says they were swayed by his just and reasonable words. More probably they were shamed by his resolution. A few weeks later the monsoon brought relief from the heat. Then, in the campaigning season that followed, Humayun lead a force east to Awadh and Jaunpur, scattering the Lodis’ recalcitrant feudatories and at last securing those broad lands and that infinite wealth. Greed could be gratified with spoils and ransoms, loyalty rewarded with offices, contracts, revenue assignments and landed fiefs.

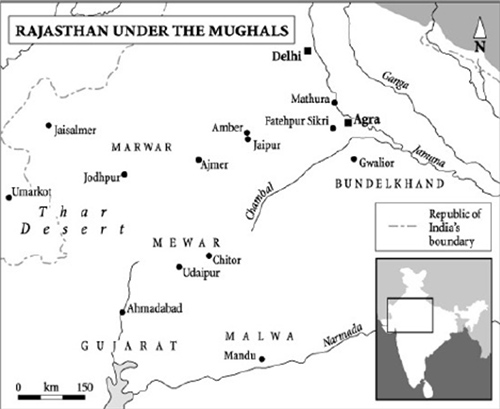

There remained, though, one more obstacle to Mughal supremacy in the north. Listing the native powers of India in order of territory and forces, Babur placed first ‘the Raja of Bijanagar’. This was Krishna-deva-raya, the greatest of the Vijayanagar kings; since his kingdom was more than a thousand kilometres from Agra he posed no threat. But the second, wrote Babur, ‘is Rana Sangha [of Mewar] who in these days has grown great by his own valour and sword’. Though contemptuous of the rajput’s idolatry, Babur seems to have had a sneaking regard for Rana Sangha. It was not because Rana Sangha had originally encouraged him to invade. No treaty had ever been signed, and it was obvious that the rajput had simply hoped for a Lodi defeat and then a Mughal withdrawal which would leave the coast clear for his own ambitions. As it was, Rana Sangha had taken the opportunity to strengthen his hold over Rajasthan, and now, in early 1527, he swiftly advanced at the head of a largely rajput army to see off the invader who had so obligingly disposed of the Lodis.

By February the rajputs were at Bayana, seventy kilometres south-west of Agra and lately occupied by the Mughals. Babur moved out to give battle amidst news that his Bayana garrison had been heavily defeated and a reconnaissance party, a thousand strong, routed by ‘the fierceness and valour of the pagan army’. It was an ominous beginning and brought gloom amongst the Mughal ranks. A soothsayer predicted disaster; subsidiary forts defected, Indian recruits deserted; ‘every day bad news came from every side.’ Once again Babur dug deep to rally his men, this time by appealing to their Islamic convictions. Since the rajputs were infidels, the war was designated a jihad . Cowardice thus became apostasy while death assumed the welcome guise of martyrdom. Better still, an acquisitive venture of doubtful legitimacy became the noblest possible of causes while any ambiguity in the minds of former Lodi retainers who were now under his command was dispelled. ‘The plan was perfect,’ confides Babur, ‘it worked admirably...’ All took an oath on the Quran to fight till they fell. Babur himself made what for him was the ultimate sacrifice by ostentatiously abjuring alcohol. Decanters and goblets were dashed to pieces, wine-skins emptied, and a quantity of the latest vintage from Ghazni salted for vinegar. At one, now, with both his men and his troublesome conscience, the born-again Babur prepared for battle.

Unfortunately the details of the great encounter at Khanua (just west of the later Fatehpur Sikri) are not altogether clear. For the forces available to Rana Sangha and his confederates a figure of 200,000 was calculated, but he probably never commanded half that number in battle. Babur, on the other hand, had far more troops than at Panipat; he had just received reinforcements from Kabul, and had now been joined by numerous ex-Lodi retainers including Ibrahim’s son. Presumably there was nothing like the disparity of Panipat and, since the battle raged for a whole day, it seems to have been more evenly and much more fiercely contested. Babur again relied on a semi-fortified arrangement of ditches and fascines flanking the same chain of carts which were again interspersed with artillery and matchlock-men; and again he deployed his cavalry so that they early encircled the enemy. But the rajputs fought with the courage, if also with the lack of co-ordination, that was their wont. In the end, according to their annals as seen by Colonel Tod, defeat resulted not from tactical naivety but from treachery. ‘The Tomar traitor who led the [rajput] van went over to Babur, and [Rana] Sangha was obliged to retreat.’8 But if such a defection did indeed take place, it clearly came when the issue was already decided.

Khanua left the Mughals supreme in the heartland of northern India. Here mopping-up operations became something of a formality as Babur looked further afield. After the 1527 monsoon another expedition was sent east to Jaunpur. Meanwhile Babur himself struck south into Malwa territory and took the fortified town of Chanderi, whose rajput garrison re-enacted the suicidal ritual of jauhar. He planned to continue south, but rapidly changed his mind when news arrived that the eastern expedition had been defeated by Lodi sympathisers and other assorted Afghans.

Campaigns against these and other dissidents in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar kept him busy in 1528–9. It is clear from his memoir, however, that such challenges were not unwelcome; indeed the belligerence was often Babur’s. ‘The army must move … in whatever direction favours fortune,’ he told his senior advisers; and again, ‘To go to Bengal would be improper; but if the move be not on Bengal, where else on that side has treasure helpful for the army?’9 Although ‘boundless and infinite’ was his declared desire to return to central Asia, it was not that easy to disengage from India; the appetite for broad lands and abundant revenues which he himself had aroused was proving insatiable. His now considerable forces and feudatories could best be held together only by the prospect of further conquests, plus the further treasure they would bring and the further emoluments they would afford. Babur, in effect, was confronting the challenge which would dog his successors: how to sustain an empire of conquest other than by making more conquests. When he died near Agra in 1530, the question remained unanswered.

INTERLUDE OR INSPIRATION

Of Babur’s three sons, Humayun, the eldest and his favourite, had been designated his heir. After winning his spurs at Panipat and Khanua, Humayun had been sent back to Afghanistan to make another bid for Samarkand. This had failed through no fault of his own, and in 1529 he had reappeared in India, perhaps alerted by news of his father’s failing health. In the event it was Humayun who suddenly sickened and looked as if he were about to die. Distraught, his father supposedly prayed by his sickbed that his own life be forfeit for Humayun’s recovery. To a man who had traded abstinence for victory at Khanua, such dealings with the divine were second nature, and once again his piety was rewarded: the father faded as the son convalesced. Humayun was twenty-two when Babur was laid to rest in a parterred garden in Agra, one of many which the nature-loving Babur had himself planned and landscaped. (Later, in accordance with his final wishes, it was to another such retreat amidst the melons and vines of Kabul that his body was removed.)

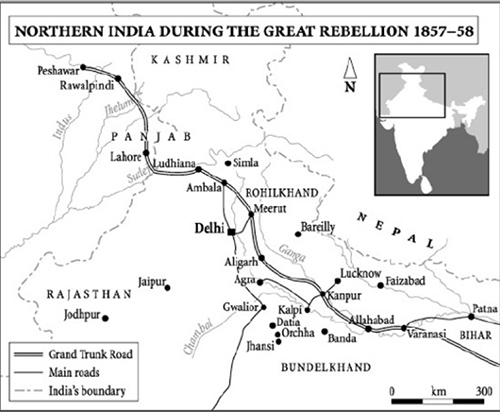

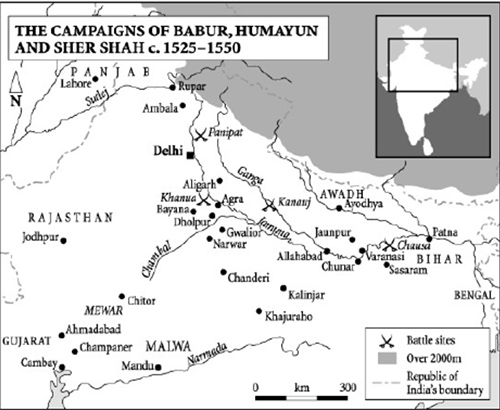

The Campaigns of Babur, Hamayun and Sher Shah c. 1525-1550

Hankering for central Asia, Babur had won an empire in India; scorning central Asia, Humayun now lost the empire in India. Thus, though he reigned for twenty-six years, he ruled for barely ten. ‘As remarkable for his wit as for his urbanity’, says Ferishta, Humayun was ‘for the most part disposed to spend his time in social intercourse and pleasure’.10 Like his father he could be a formidable campaigner but, more wayward, more indulgent and much more indolent, he knew neither how to counter failure nor how to capitalise on success. Nor, unlike Babur, did he personally write any record which might explain his actions – or the lack of them. The long interludes of passivity which punctuated his campaigns are therefore ascribed to his addiction to opium, a drug which in various ‘confections’ Babur too had used and on which Humayun seemingly depended.

But his first mistake was to trust his three brothers; later Mughals would learn not to repeat it. Instead of eliminating them, he appointed each to the command of a part of the empire. Prince Kamran, who got Kabul, promptly added to it the Panjab, thus in effect severing Babur’s legacy. Humayun simply accepted this situation and, in so doing, emboldened his two other brothers, Askari and Hindal. Both would support him only when it suited them; and when it did not, each would make a bid for the throne.

More pressing in Humayun’s estimation was the situation in the east. Lodi warlords had again seized Jaunpur; Kalinjar, the great hill-fort of the Chandelas of Khajuraho which had defied Mahmud of Ghazni and almost every Delhi sultan, awaited its first Mughal assault; and in the neighbourhood of Varanasi one Sher Khan, an Afghan of the Sur clan who had followed the Lodis into India, was carving out a kingdom for himself based on the fortress of Chunar. Humayun abandoned his siege of Kalinjar to tackle the situation in Jaunpur; but he had scarcely focused on Sher Khan when news came of a threat to Agra from Ahmed Shah, the sultan of Gujarat. Operations in the east were therefore suspended, much to Sher Khan’s advantage, as Humayun faced about. Pausing only to commission a palace which was meant to be the nucleus of another new Delhi, he led his forces south and west.

During the two-year (1534–6) campaign which followed, Humayun achieved in Rajasthan, Malwa and Gujarat conquests of which his father would have been proud and which his son (Akbar) would more famously emulate. The Gujarati sultan, though possessed of a formidable artillery, was roundly defeated, and the near-impregnable heights of both Mandu and Champaner were successfully stormed. At Champaner Humayun himself led the raiders and, with hammer and pitons, scaled the sheer rock-face in a wildly audacious assault which, says Ferishta, was ‘equal in the opinion of military men to anything of the kind recorded in history’.11 Ahmadabad was then occupied and so was Cambay, respectively the richest city and port in western India. It was a dazzling triumph which, carefully consolidated, could have provided the economic foundation of Humayun’s empire as well as doubling its size. But he rejected the traditional solution of reinstating the defeated Ahmad Shah as a feudatory and, instead, installed the worthless Prince Askari. He then retired to Mandu whence, after several dazed months in the company of his favourites and his opium pipe, he headed home to Agra. As he did so, his conquests were simply rolled up behind him. Askari, seeing Gujarat primarily as a base whence to launch a bid for the throne, allowed Ahmad Shah to reoccupy his kingdom while he himself also hastened to Agra.

There Humayun forestalled him but, nothing if not conciliatory, again forgave the fraternal transgression. Then he returned to the familiar solace of pipe and playmates. ‘Public business was neglected,’ says Ferishta, ‘and the governors of the surrounding districts, taking advantage of this state of affairs, … enlisted under the standard of Sher Khan Sur.’ In July 1537 Humayun at last bestirred himself and marched east against the Afghan usurper. Chunar fell after a long siege but Sher Khan was not there; nor was he at Jaunpur or anywhere else in Awadh. For while Humayun had been conquering Gujarat, Sher Khan had been about the same business in Bihar and now Bengal. And unlike Humayun, he was taking great care to secure his newly-acquired conquests. Instead of another Afghan upstart, Humayun suddenly found himself faced by a well-prepared contender for sovereignty. The tussle between Mughal and Afghan was far from over.

In 1539, after much to-ing and fro-ing in Bengal, the rival armies finally met at Chausa between Varanasi and Patna. Humayun fell for an Afghan ruse and was defeated. He barely escaped with his life, his troops were decimated, and the myth of Mughal invincibility was badly dented.

A year later it was utterly exploded. Near Kanauj, the imperial city on the upper Ganga from which the Gurjara-Pratiharas had once obscurely reigned, the fate of the short-lived Mughal empire looked to have been decided. In a surprising reversal of Panipat, Humayun’s army, forty thousand strong and well supplied with firepower, was overwhelmed by Sher Khan’s fifteen thousand mainly Afghan cavalry. Humayun again escaped with his life – and with his monstrous diamond. But failing to win help or even sanctuary from his ungrateful brothers, he became a fugitive in the deserts of Sind and Rajasthan and then an exile at the court of Shah Tamasp, the Safavid ruler of Iran. Luckily Shah Tamasp liked diamonds. Humayun’s fortunes would yet revive. Meanwhile Sher Khan Sur was supreme.

The Afghan Surs, dynastically sandwiched amongst the great and magnificently documented Mughals, easily elude the credit that is their due. Their fifteen-year supremacy is sometimes portrayed as a reactionary interlude or an impertinent interruption to the glorious Mughal succession. Yet the interlude was rich in inspiration. Sher Khan, who following victory at Chausa had assumed the royal title of Sher Shah, was as able as any Mughal. If, fortuitously, the adventures of Babur the Mughal have a fictitious ring, no such complaint is heard of the stern and often devious doings of Sher Shah Sur. Where Babur’s genius lay in the glamour of battle-craft, Sher Shah’s lay in the minutiae of statecraft. To the sombre text of his short reign the empire which would soon embrace all India owes just as much as to the animated excitement of Babur’s more colourful adventures.

Although embroidered by Afghan admirers, it is clear that Sher Shah’s rise from an insignificant Lodi retainer with a couple of small fiefs near Varanasi was in itself remarkable. It took some time, and when he finally gained the throne he was already into his fifties. But to have overcome the rivalries of his fractious Afghan compeers was more than most Lodis had managed, while the conquest of Bengal, and his subsequent settlement of it, reduced that troublesome and previously independent kingdom to a subordinate status unknown since the Tughluq interventions of the fourteenth century.

Further Sur campaigns in the Panjab, Sind and Malwa followed the defeat of Humayun and duly secured those provinces. An expedition into the Deccan like that of Ala-ud-din Khalji, the sultan whom Sher Shah most admired, was also proposed. But, a devout if not fanatical Muslim, Sher Shah argued that the eradication of infidel authority within his existing domains was a higher priority. On the pretext that Muslim mothers and maidens were being abused in rajput households, he preferred first to reduce bastions of Hindu resistance like Jodhpur, Chitor and, fatefully, Kalinjar. There, too, he triumphed where so many others had failed, but at the cost of his life. A rocket aimed at the fort rebounded off its walls and, exploding, ignited the pile of rockets which were intended to follow it. Sher Shah, who was directing operations, was horribly burnt. He died a few hours later, just as news of the fort’s surrender arrived.

In so short a reign (1540–5) a complete overhaul of the machinery of government had scarcely been possible. Yet ‘during that brief period his energetic administration forecast many of the centralising measures in revenue assessment and military organisation that would be carried to completion by the Mughals.’12 These were particularly evident in his settlement of Bengal. Instead of appointing another all-powerful governor, who would assuredly cast off his allegiance at the first opportunity, he divided the province into districts, each directly responsible to himself, and then divided the exercise of authority amongst civil, military and religious officials who were themselves subject to rotation. There and elsewhere efforts were also made to rationalise the assessment and collection of revenue and to afford the cultivator a modicum of security; village headmen were made responsible for any unpunished crimes; corrupt officials were dismissed.

Corruption within the military was also tackled. The practice was revived of branding all cavalry horses so that on active service they could not be replaced by lesser mounts; and for similar reasons attempts were made to compile service rolls which identified and described each trooper. Military posts were established throughout the provinces; roads and caravanserais were built; illegal imposts and duties were removed to facilitate trade. Memorably Sher Shah also occupies an important place in the history of Indian coinage, in that he coined the first silver rupees which, together with his other coins of gold and copper, would form the basis of the Mughal currency.13

Something similar might be said of his architectural creations. Babur’s only noteworthy additions to India’s monuments had been three mosques of little stylistic distinction. One, at Panipat, celebrated his victory over the Lodi, although another, that at Ayodhya, has since upstaged it. Historians have of late been sorely taxed over this Ayodhya Babur-i (or Babri )masjid. Did it replace a Hindu temple which marked the spot where Lord Rama (of the Ramayana ) was born? And what, if any, was Babur’s role in its construction? Ever since Hindu fanatics laid into the mosque with pickaxes in 1992, thus provoking a more serious cave-in of modern India’s secular credentials, more words have been written about this unimpressive site than about any other in India. Adding to them would be only to invite contradiction.

Happily, the much more stylish monuments of Sher Shah have fared better. In Delhi he added to the complex begun by Humayun on the supposed site of Indraprastha, the capital of the Pandavas in the Mahabharata and now known as Purana Qila. He also built there a mosque. Only parts of this Qila-i-Kuhna survive, but ‘no sanctum and façade in India possesses quite such measured dignity allied to perfect taste in the rich but restrained decoration.’ Making comparison with Brunelleschi, the master-builder of fifteenth-century Florence, J.C. Harle in the Pelican History of Art series finds here ‘a strength, beauty and richness beyond anything achieved by the Mughals’.14

Still more arresting, although rarely visited, is the magnificent five-storey tomb at Sasaram (Sahasaram), midway between Varanasi and Gaya, to which Sher Shah’s charred remains were carried from Kalinjar for interment. Octagonal like many of the Lodi tombs, and set upon a stepped plinth in the middle of a lake like that of Ghiyas-ud-din Tughluq, Sher Shah’s mausoleum is yet wholly original. At the angles of three of its storeys, chattris (pillared and cupola-ed pavilions) of diminishing size recall the amlakas of a temple tower and contribute to a pyramidal profile of stunning beauty. The overall impression is as much of a palace as of a tomb and may owe something to Man Singh’s great façade at Gwalior which Babur had much admired and where Sher Shah had stayed.

Nearly fifty metres high, the massive scale of Sher Shah’s tomb is also remarkable. Dwarfing all previous Muslim tombs in India, it set another standard to which the greatest Mughal builders, Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan, would dutifully strive. Nor was it their only challenge. The most ambitious structure of the seventeenth century would in fact be located neither in Agra nor Delhi but deep in the Deccan at Bijapur. Not far away, the sprawling stone metropolis of Vijayanagar, India’s Angkor, offered further convincing proof that in the peninsula worthy rivals of Mughal and Sur yet flourished.

THE RISE AND FALL OF VIJAYANAGAR

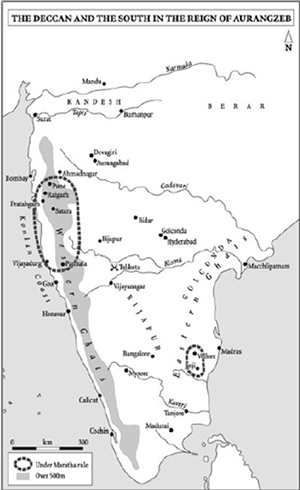

When listing the native powers of what he called ‘Hindustan’, Babur had placed first ‘the Raja of Bijanagar’, that is Vijayanagar. From the great city beside the Tungabhadra river in northern Karnataka an erratic succession of Hindu kings had been extending its sway throughout the fifteenth century. With territories that now included much of Andhra Pradesh and Kerala and most of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, the king of Vijayanagar, according to the Babur-nama, controlled the most extensive kingdom in the subcontinent. His forces were also the most numerous, although Babur knew nothing else worth recording of such a distant potentate.

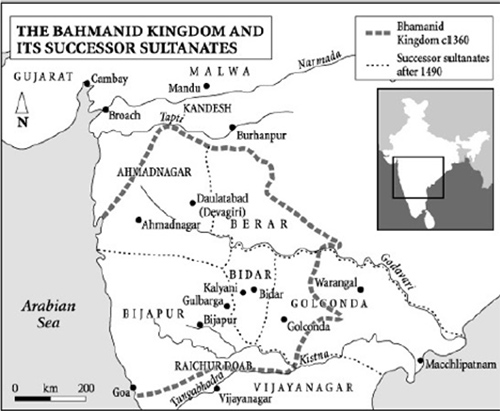

He was better informed as to the plight of the Bahmanid sultans, Vijayanagar’s one-time rivals in the Deccan. ‘At the present time no independent authority is left them; their great begs have laid hands on the whole country, and must be asked for whatever is needed.’15 In fact the great begs, or nobles, were in the process of carving up the Bahmanid kingdom. While Mahmud Shah, the last Bahmanid, yet reigned (1482–1518), four major power-centres, each with its own Muslim dynasty, laid claim to the Bahmanid dominions. One, based on the city of Ahmadnagar (two hundred kilometres east of Bombay in Maharashtra), occupied the north-western corner of the erstwhile sultanate and, adjacent to Malwa, would soon be of consuming interest to Babur’s successors; another retained Bidar, the Bahmanid capital; to the south-east, the third was based on Golconda, the future Hyderabad; and the fourth, based on Bijapur, inherited the southern, or Karnataka, part of the Bahmanid sultanate and, along with it, frontline status in respect of the Vijayanagar kings.

The Bahmanid Kingdom and Its Successor Sultanates

For Vijayanagar this gradual fragmentation of its ancient rival was timely. Following the death in 1446 of Deva Raya II, the last effective ruler of the Sangama dynasty, Vijayanagar too had been rent by internal strife. But territory lost in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu had been largely reclaimed by Narasimha, a general who eventually assumed the kingship and founded the Saluva dynasty. His death in 1491 led to another succession crisis from which emerged a second Narasimha who founded the Tuluva dynasty. It was this Narasimha Tuluva who in 1509 was gloriously succeeded by his half-brother, and Babur’s contemporary, the great Krishna-deva-raya.

During the latter’s twenty-year reign Vijayanagar soared to its spectacular zenith. Krishna-deva-raya’s armies overran the strategic Raichur Doab, menaced the new Deccan sultanates, worsted even the Gajapati kings of Orissa and claimed extensive new territories in Andhra Pradesh. Tribute and plunder poured into Vijayanagar, there to be lavished on royal rituals, academic patronage and architectural extravaganzas. For his support of scholars Krishna-deva-raya was hailed as another King Bhoj. The city itself, covering thirty square kilometres, occasioned the sort of superlatives which a hundred years later would be showered on the Mughal capitals of Agra and Delhi. It ‘seemed to me as large as Rome, and very beautiful’, wrote Domingo Paes, a Portuguese visitor in the 1520s. Paes refrained from guessing at its population lest the improbable figure be taken to impugn the rest of his account, but from a check on its markets he was convinced that it was also ‘the best provided city in the world’. Likewise the kingdom’s resources, about which Paes was less reticent: ‘the king has continually a million fighting troops [under arms].’ And likewise Krishna-devaraya himself, of whom Paes provides a thumbnail sketch as convincing as any in Mughal literature.

This king is of medium height, and of fair complexion and good figure, rather fat than thin; he has on his face signs of small-pox. He is the most feared and perfect king that could possibly be, cheerful of disposition and very merry; he is one that seeks to honour foreigners, and receives them kindly, asking about all their affairs, whatever their condition may be. He is a great ruler and a man of much justice, but subject to sudden fits of rage, and this is his title ‘Crisnarao Macacao, king of kings, lord of the greater lords of India, lord of the three seas and of the land’. He has this title because by rank he is a greater lord than any by reason of what he possesses … but it seems that (in fact) he has nothing compared to what a man like him ought to have, so gallant and perfect is he in all things.16

Thanks to this paragon of kingly virtues, to the magnificence of his metropolis as evidenced by its still staggering ruins, and to the abrupt and imminent eclipse of both, Vijayanagar has attracted much scholarly attention. Typically the kingdom has been seen as the epitome of traditional Indian kingship and a spectacular finale to two thousand years of Hindu empire. ‘It stood for the older religion and culture of the country and saved these from being engulfed by the rush of new ideas and forces.’17 It was also ‘the last bastion of Hinduism’; and when it fell, ‘the South died’. All the city’s monuments, its bazaars and streets, its temples and palaces, are constructed of massive stone blocks which have been hewn, dressed and sculpted from the rock-scape of monumental boulders amongst which they stand. Even the intervening hills are composed of these boulders, and so daringly are they stacked and balanced on top of one another that they too could be architecture and the city’s monuments but an inspired elaboration of what nature has already ordained. Just so the kingdom has often been seen as a natural and climactic reordering of the ideals and achievements of all those earlier stone-whittling, elephant-trumpeting Deccan dynasties – Shatavahanas and Vakatakas, Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas. In particular the earliest Chalukyas seem to have inspired the kings of Vijayanagar, who modelled some of their temples on those of Badami and Aihole.

More recently, however, the Vijayanagar kingdom has been reinterpreted as very far from traditional and in fact a radical experiment in political and military organisation during a time of social and economic upheaval. The evidence, culled from accounts like that of Paes, from literary sources and from a painstaking analysis of thousands of inscriptions, suggests that by the sixteenth century the defence of Hindu dharma was not uppermost in the minds of the Vijayanagar kings (if it ever had been). Nor did they rely on the support of satellite kings or the impact of intoxicated elephants. Instead they looked to often Muslim cavalry and to a variety of new military structures including ‘a system of royal fortresses under brahman commanders … Portuguese and Muslim mercenary gunners … foot-soldiers recruited from non-peasant, or forest, people … and a new strata of lesser chiefs totally dependent on military service [the so-called ‘Poligars’]’.18

At the apex of this organisation the Vijayanagar kings, dispensing with the traditional notion of paramountcy implicit in the ‘society of kings’, had adopted a semi-feudal system of powerful military subordinates. It was amongst these subordinates, known as ‘Nayaks’ and numbering several hundred, that most of the kingdom was parcelled out. They were appointed by the sovereign and were responsible both for maintaining large military contingents at the service of the sovereign and for organising the collection and remission of revenue to the sovereign. In other words they performed somewhat the expected role of the mainly Afghan feudatories in the north. But whilst the latter, from a position of semi-independence, were coming under increasing pressure to submit to Mughal or Sur overlords, the Nayaks in the south, from a position of dependent commanders, were becoming king-makers whose standing with local religious and commercial institutions often eclipsed that of their sovereign.

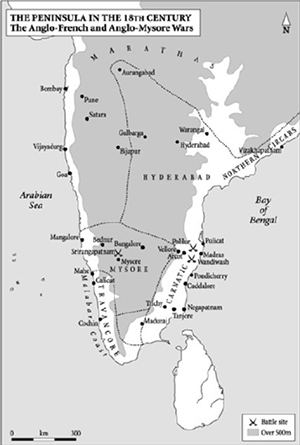

Other factors beyond the control of Krishna-deva-raya and his successors also contributed to the growing instability of the kingdom. Amongst them was the new Portuguese presence on the peninsular seaboard. According to one authority, ‘the Portuguese have the dubious distinction of introducing politics into the [Indian] ocean.’19 Maritime trade had hitherto been considered as open to all and subject only to competitive pressures and local incentives. That Muslim traders and Islamic shipping interests had gained a near monopoly of the sea-routes to the west and to the east had not therefore been cause for alarm. But as of the early sixteenth century the freedom of the seas and of the monsoon winds was called in question. Thanks to developments in navigation and naval gunnery, oceanic trade was suddenly revealed as susceptible to state direction and subject to military control. By demonstrating that maritime empire was a paying and practical proposition, the Portuguese had indeed politicised the Indian Ocean. Land-based empires which in any way depended on overseas trade would have to come to terms with it.

Vasco da Gama’s appearance at Calicut on the Kerala coast in 1498 had climaxed a century of Portuguese attempts to find a sea-route round Africa to the spice-producing Indies. He returned to Lisbon with a cargo of Indian pepper and his route was immediately followed by an annual armada of Portuguese shipping, much of it manned and armed for combat. In 1503 the first Portuguese fort was built at Cochin, whose raja then became something of a Portuguese puppet. Two years later the appointment of a viceroy for something which Lisbon now called its Estado da India, or ‘State of India’, betrayed the true nature of Portuguese ambition. Goa was taken in 1510, not from Vijayanagar but from the Bijapur sultanate, and was soon fortified as the hub of Portuguese maritime empire in Indian waters.

Stiffer resistance was offered to the Portuguese by the sultan of Gujarat and his distant allies, the Mameluke rulers of Egypt with whom Gujarati merchants traditionally traded. But in the 1530s the ports of Bassein (near Bombay) and Diu (in Saurastra) were incorporated into the Estado da India and effectively controlled access to Gujarat’s outlets of Cambay, Surat and Broach. Portuguese ships and guns were demonstrably superior to those of either Indian or Arab, and Lisbon’s claim to control the shipping of the entire west coast thus became effective.

To what extent the rulers of Vijayanagar had benefited from overseas trade is disputed. But the land-routes from the west coast ports up to Vijayanagar were evidently a high priority, and the city was a conspicuous consumer of foreign imports as well as a major market for their onward distribution. Crucially these imports included the desiderata of every Indian army, namely horses, mostly from the Persian Gulf, and some fire-arms. To encourage the supply of horses it was said that the Vijayanagar rulers would pay even for dead ones. The new Portuguese monopoly of the horse trade looks both to have deprived the kingdom of important revenues and to have prejudiced the supply of remounts when, as under Krishna-devaraya’s successor, Vijayanagar was at war with the Portuguese.

The war in question did not last long. Of far greater consequence was the rivalry between Achyuta-deva-raya, the brother and nominated successor of the great Krishna-deva-raya, and Rama Raja, Krishna’s powerful son-in-law. Failing to secure the succession in 1529, Rama Raja tried again when Achyuta died in 1542. To advance his chances, he also sought the aid of the sultan of Bijapur. There were ample precedents for the involvement of the sultanates in the Vijayanagar succession (and vice versa). Rama Raja, a consummate intriguer, was merely taking advantage of the Deccan’s fluid and opportunist rivalries. When, thanks to this alliance, he was safely ensconced as regent, he continued to pursue a tortuous policy of advancing Vijayanagar’s frontiers by exploiting the rivalries between Bijapur, Golconda and the other Bahmanid successors.

In this Rama Raja succeeded, if anything, too well. During twenty years of complex intrigue he so provoked the sultanates that they came to fear for their very survival. It is possible that he also outraged their Islamic sensibilities. Ferishta makes this accusation so often that it smacks of pious convention; on the other hand religious sensitivity and sectarian solidarity may well have been heightened at a time when the neighbouring Portuguese were combining the anti-Muslim spirit of the Crusades with the excesses of the Inquisition.

Certainly, and fatally, Rama Raja also overstretched those frayed loyalties on which Vijayanagar’s cohesion depended. This became apparent when in 1564 the four sultans at last patched up their differences and turned on him in concert. To meet this threat he summoned his Nayaks even from as far south as Madurai. Most did respond, but in January 1565 the Vijayanagar forces were catastrophically routed in the battle of Talikota. Rama Raja himself was beheaded, and casualties were colossal. Yet the great city of Vijayanagar, with its seven massive walls and its ingeniously designed gatehouses, might still have been defended. In the event, it was just deserted; Nayaks and Poligars withdrew to their individual territories. The 550 elephant-loads of treasure which they hastily ‘rescued’ from the city could just as well have been pillaged.

The battle had taken place on the banks of the Kistna river, about 120 kilometres north of Vijayanagar. But the victors did not immediately swoop on the city; local scavengers seem to have been the first to gain access. Nor is it self-evident that the Muslims’ intention was to obliterate the place. Despite colourful descriptions of a five-month sack, wholesale slaughter, savage iconoclasm and such remorseless demolition that ‘nothing now remains but a heap of ruins’,20 the impression these ‘ruins’ convey is less of wilful destruction and more of neglect, plus some random treasure-hunting and much casual pillage of building materials. Temples, the bigot’s prime target, prove to be the least damaged structures; and in many of them the statuary, so invitingly vulnerable, remains miraculously intact. In short the city, like the kingdom, looks to have suffered less from conquering fanatics and more from that deepening internal crisis of authority.

Rid of Vijayanagar’s supervision, Nayaks would continue to rule in many parts of the south just as would the quarrelsome sultans in the Deccan. In the extreme south the Nayaks of Madurai would evade even Mughal rule. Not so the others. Just when ‘Vijaya-nagar’ (‘City of Victory’ in Sanskrit) was disappearing from the map, a ‘Fateh-pur’ (‘City of Victory’ in the Persian of the Mughal court) was being built at Sikri near Agra. Urban triumphalism was passing from the Deccan to the north. Vijayanagar’s collapse did indeed spell the end of the south as a separate political arena. As time would reveal, the real victors of Talikota were not Bijapur and Golconda but the Great Mughals.