18. Awake the Nation: 1880–1930

TRAINS AND DRAINS

INDIA’S RURAL LANDSCAPE looks rather different from that of most tropical ex-colonies. In particular it lacks those bold and regimented patterns of cultivation associated with large-scale agri-business. Tousled hectares of banana and coconut, rows of pineapples receding over the horizon, or gloomy ranks of regulation rubber trees are comparatively rare. There are exceptions: tea estates muffle the hills of Assam and Kerala in what are major enterprises by any standards, and cotton in the Deccan monopolises the black soil for mile upon featureless mile. But for the most part, rural India is a patchwork of more intimate fields, often eccentric in their layout, not over-capitalised in terms of machinery, and devoid of that plantation logic which is the usual legacy of colonial agrarian development.

It could have been otherwise. Expectations of white settlement and European enterprise transforming Indian agriculture had surfaced in the blueprints of early-nineteenth-century reformers. In respect of two highly valuable crops, the opium poppy and the indigo vetch, they had been partially realised. British investment in the processing necessary to produce China’s favourite narcotic and to extract the blue dye for assorted European uniforms led to some contentious involvement in the supply and cultivation of these crops, particularly in Bengal and Bihar. But the East India Company had been generally opposed to European settlement, and the extortionate conduct of such quasi-planters had done nothing to change attitudes. In 1859–61, just as the British were congratulating themselves on having isolated Bengal itself from the traumas of the Great Rebellion (or sometimes the ‘red mutiny’), serious riots (known as the ‘indigo’ or ‘blue mutiny’) had broken out amongst the oppressed indigo cultivators of west Bengal. Championed by Calcutta’s press, which obligingly pointed out that the planters were mostly British, and not without some official sympathy, the rioting ryots duly won relief from their supply contracts. Thus by 1861 ‘the cultivation of indigo was virtually wiped out from the Bengal districts.’1 Elsewhere indigo cultivators had a longer wait for redress. In neighbouring Bihar it would be over fifty years before their cause was adopted by an eccentric outsider, lately arrived from Africa, called Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

Also in 1861, while the ‘blue mutiny’ was in progress, Mr J.W.B. Money, a Calcutta-born Englishman with interests in indigo, returned from a trip to the Netherlands East Indies. Nursing new thoughts on India’s colonial management, Money promptly wrote a book. The Dutch, according to his provocatively entitled Java, or How to Manage a Colony, had responded to the demise of their own East India Company by introducing a ‘Cultivation System’ whereby the cultivator was obliged to set aside part of his land and labour for the production of specified quantities of an export crop. These yields, usually of sugar or coffee, were then rendered to the government or its contractors in lieu of land rent. Natives, seemingly, did not want rights and legal redress. They wanted a chance to prosper, and that was precisely what the system offered in that it also guaranteed the purchase of any surplus. It thus encouraged the circulation of money, said Money, and improved native purchasing power.2

That the system was advantageous to the Netherlands was sensationally obvious. By 1860 a third of that state’s annual revenue derived from its East Indies colony. Domestic taxation was reduced and the entire Dutch state railway network was built on the proceeds. Why could India, cowed by the suppression of the Great Rebellion, not now be managed to mutual advantage in the same way?

But Money’s cheerful endorsement of the Dutch system overlooked the fact that most Javanese were not in fact enriched. Rather were they reduced to a state of rural bondage which was quite irreconcilable with either Munro-ite ideals of a sturdy peasantry or Cornwallisite ideals of a benign landed gentry. Mr Money also ignored the prevailing spirit of laissez faire which had earlier deprived the English East India Company of its trade monopolies and had since witnessed a steady withdrawal of government from many other areas of economic management. In the Americas and elsewhere, including even the Netherlands East Indies, British exporters and business houses were doing very well without the paraphernalia of empire; free trade, not state management, was the key.

Furthermore, and perhaps decisively, the idea of introducing a plantation economy was precluded by the extent to which in India land, and the extractive surplus/revenue rights to which it was subject, had become marketable assets. In Bengal, for example, the Raja of Burdwan had recently divided up part of his zamindari into lots, or patnis, on condition that the purchasers, or patnidars, paid the revenue on these lots. The patnidars then ‘sometimes sold lots to others known as dar-patnidars, and they too sold lots to others below them, known as das-dar-patnidars ... By 1855 it was estimated that some two-thirds of Bengal were held on tenures of this sort, and there is a presumption that many of the purchasers had urban connections.’3 Inheritance laws encouraged a similar fragmentation; and city-based merchants, moneylenders and financiers were indeed prominent amongst the purchasers.

The ‘commercialisation of agriculture’, begun in late Mughal times, was thus an established fact by the mid-nineteenth century. Facilitated by the new railways, export booms in cotton during the 1860s (courtesy of the American Civil War) and in wheat from the 1870s onwards enriched and entrenched these middle-men as well as sustaining the mainly British business houses which handled overseas shipping and brokerage. Yet such was this superstructure of agents and rentiers, and such the extractive culture of the revenue system, that profits rarely found their way back into production other than as advances on the next crop. The actual cultivator thus became, if anything, even more indebted. Commercialisation only ‘led to differentiation without genuine growth’. In effect India’s rural economy was already experiencing the down-side of plantation economics, in terms of labour exploitation, without the usual up-side of capital investment. ‘The point is not that so many peasants suffered (they would have suffered under capitalist modernisation, too) but that they suffered for nothing.’4

The British preferred to emphasise their investment in infrastructure, especially railways and irrigation works (‘trains and drains’). They also pointed to the country’s generally favourable balance of payments. Critics, though, were less impressed by India’s theoretical prosperity and more exercised by Indians’ actual poverty. As early as 1866 Dadabhai Naoroji, the future ‘Grand Old Man of Congress’, had begun to wonder whom the trains actually benefited and whither the drains actually led. In fact he developed a ‘drain theory’ which, with ramifications provided by his successors, would run like an undercurrent throughout the nationalist debate.

This ‘drain theory’ maintained that India’s surplus, instead of being invested so as to create the modernised and industrialised economy needed to support a growing population, was being drained away by the ruling power. The main drain emptied in London with a flood of what the government called ‘home charges’. These included salaries and pensions for government and army officers, military purchases, India Office overheads, debt servicing, and the guaranteed interest payable to private investors in India’s railways. Calculated in sterling at an increasingly unfavourable rate of exchange, they came to something like a quarter of the government of India’s total revenue. With much of what remained being squandered on administrative extravagances and military adventures in Burma and Afghanistan, it was not surprising that Indians lived in such abject poverty or that famines were so frequent.

The theory also included an analysis of how the drain actually worked. The Secretary of State for India in London obtained sterling to meet his ‘home charges’ by selling bills of exchange to British importers. Presented in India, these bills could be converted into rupees out of government revenues and so used for the purchase of Indian produce. The private sector therefore played an important part in the drain since its exports from India constituted the drain’s flow. By the same token the export surplus was of little economic benefit to Indians; and worse still, since they consisted mostly of raw materials, exports gave no encouragement to India’s industrialisation. The classic case was cotton. In the days of the Company, British purchases had been mainly of finished piece-goods. Latterly, with Lancashire’s mills underselling India’s handloom weavers, British purchases switched to raw cotton and yarn. Now, when new and often Indian-owned mills in Bombay were at last in a position to compete, they were repeatedly frustrated by tariff policies which favoured British imports and by regulations which handicapped Indian production.

India’s embryonic industries – principally jute, cotton, coir and coal – needed protection; the British insisted on free trade. Their laissez faire attitudes extended even to the land revenue, where rising prices meant that fixed revenue assessments actually became somewhat less onerous during the latter half of the nineteenth century. But rather than adjust such assessments the government now preferred to explore other sources of revenue, like introducing an income tax. For the Great Rebellion, far from emboldening the British to remodel India’s agrarian economy along the regimented plantation lines suggested by Money, was seen to have demonstrated the extreme danger of intervention.

Such governmental conservatism did not mean that Indians were entirely spared the plantation experience. In regions of marginal cultivation, and especially on the tea estates which proliferated in the Assam hills from the 1850s onwards, indentured labour was widely employed. Further afield the abolition of slavery and the introduction of new crops created more exotic markets for indentured Indian labour in Sri Lanka, Burma, Malaya, Fiji, Mauritius, south and east Africa and the Caribbean. Mortality rates amongst these migrants were so high in the nineteenth century, and the terms of indenture so oppressive, that critics saw only another form of slavery. The plight of emigrant Indian labour would feature prominently amongst early nationalist grievances, and in Africa M.K. Gandhi would find a challenging field for his first experiments in satyagraha.

The young Gandhi had found his way to Natal in south-east Africa in the employ of a Gujarati trading firm. India’s maritime and mercantile contacts with south-east Asia had been sustained ever since the Pala and Chola periods, but under Muslim, Portuguese and British dispensations had been considerably extended. They now reached round the Indian Ocean and the Pacific rim to Aden, Zanzibar, east and south Africa, China, Japan and even the Pacific coast of North America. Latterly small communities of Indian clerks, police, dockworkers and other service personnel had become as sure a sign of a British presence in these places as the Union Jack. From as far afield as Vancouver and Singapore, as well as Gandhi’s Natal, such expatriate groups would make a valuable contribution to the struggle for Indian independence. Conversely they, and the mass of indentured migrants, brought Indian issues to an international audience.

The accompanying diaspora of religious and social traditions established a score of ‘Little Indias’ from Singapore to Georgetown, Guyana, which were as much colonies of Indianisation as their parent settlements were colonies of Anglicisation. As in the long-forgotten days of Kanishka and the Karakoram route, India was successfully projecting its cultural influence just when politically it was in deepest eclipse. But, linked by the telegraph and the shipping line, such agents of outward acculturation now also served as antennae for inward politicisation. From Japan came word of Asian regeneration, from Europe came news of Ireland’s struggle against British rule, and from the white settler colonies of Africa and Canada came ideas of autonomy and dominion status. India was not alone. British rule was not immutable. Nor was it invincible.

Augmented by a further exodus in the twentieth century, mainly to Europe, North America and the Gulf states, the diaspora would make the peoples of the subcontinent amongst the most numerous and recognisable of global societies. In Britain alone the number of immigrants from the subcontinent would eventually exceed the total of British civilian residents in India during the nearly two hundred years of British rule. Between 1880 and 1930 the average exodus was running at around a quarter of a million Indians a year, mainly from Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Gujarat. But although they made a significant impact on most of the receiving countries, they had little effect on India’s teeming demography. This was in part because most indentured emigrants returned after the expiry of their five-year indenture. So did the troops of the British Indian army who were increasingly deployed on imperial service in China, south-east Asia, Persia and Africa. And so did the barristers, like Gandhi, the administrators, doctors and others who, bursting from India’s universities in ever greater numbers, sometimes travelled abroad to complete their studies or pursue their professions. A few Indians were at last acquiring the first-hand experience of other cultures by which they would be enabled to judge their own identity as Indians rather than as members of a particular Indian community. It would be no coincidence that most of the giants of the independence movement, from Dadabhai Naoroji to M.A. Jinnah, Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, were returnees.

Overseas study was an option only for the privileged. For most Indians an acquaintance with the traditions of Western thought depended on a university education, supported by access to newspapers and books. In the increasingly politicised and cosmopolitan atmosphere of the three main ‘presidencies’ – by which was now meant the cities of Calcutta, Bombay and Madras – the level of graduate debate was sophisticated and intense. Participants drew on a wide range of argument and ideology, and they avidly followed developments elsewhere in the world, especially Japan’s modernisation and the course of Anglo–Irish disentanglement. Their enthusiasm for association and mutual collaboration over a range of political and social issues was equally impressive. But in cities where all manner of caste, professional, communal and linguistic groups were well represented, nationalism was perhaps seen more as the sum of its parts than as an indivisible whole. It was something to be laboriously constructed from within rather than being self-evidently defined from without.

Higher education was restricted to a minute elite; books and newspapers circulated sluggishly outside the main cities. The homespun nationalist in the mofussil had only the ubiquitous British presence against which to measure and define his identity. As in 1857, all manner of different definitions resulted. Yet recent studies, like that undertaken by Christopher Bayly in respect of Allahabad and other north Indian towns, discover a significant continuity between traditional urban groupings and the later ‘nationalist’ groups and interests which would subscribe to the National Congress. ‘In all the major centres of Hindi-speaking north India, the new religious and political associations had links with existing shrines, sabhas [councils, societies] and commercial solidarities. In Allahabad, for instance, commercial and devotional relationships generated by the great bathing fair, the Magh [or Kumbh] Mela, contributed as much to the emergence of modern political associations as the camaraderies of the Bar Library.’5

Similar links are traced between Muslim associations of service gentry and membership of the later Muslim League. In Maharashtra the devotional allegiances of Pune’s brahmans would see their festivals transformed into political protest gatherings and their cults being promoted as nationalist propaganda. Nor was this a passing phenomenon. ‘The style of Hindu politics which emerged from the corporate urban life of the later nineteenth century remains vital … whether in the guise of the Hindu Mahasabha of the 1930s or of the Jana Sangh in the 1970s’6 – or indeed of the Jana Sangh’s later reincarnation, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Here, in short, was (and is) a third perspective, one by which nationalism was perceived, neither from without as an indivisible whole, nor from the metropolitan centres as the sum of its parts, but from deep within as a projection of entrenched sectional interests which were proud to owe very little to extraneous ideologies or a foreign-language education.

EVERYTHING IN MODERATION

Lord Lytton’s 1877 Imperial Assemblage at Delhi was the sort of wasteful extravaganza to which Indians of almost every perspective took strong exception. That it happened to coincide with the worst famine of the century, which claimed perhaps 5.5 million lives in the Deccan and the south, added to the outrage. It may therefore be deeply unacceptable to suggest that the Assemblage provided the format, eight years later, for the first meeting of the Indian National Congress. But parallels have been noted. ‘The early meetings of the All India Congress Committees were much like durbars, with processions and the centrality of leading figures and their speeches...’ The sentiments expressed were not dissimilar either. The Congress leaders spoke of progressive government and the welfare and happiness of the Indian people, just like the viceroy; and when they demanded fair access to the civil service and greater representation in the councils of state they were merely reminding the Calcutta government of pledges already made, as for instance in the Queen’s 1858 Proclamation which promised that all suitably qualified Indians would be ‘freely and impartially admitted to office in Our service’. Indeed, some had already been admitted; but as the supply of qualified Indians increased, so did the government’s reluctance to honour such pledges. Hence the reminders. Framed in the British ‘idiom’ of the great Delhi durbar, they ‘set the terms of discourse of the national movement in its beginning phases. In effect, the early nationalists were claiming that they were more loyal to the true goals of the Indian empire than were their British rulers.’7

Nor was this claim obviously mischievous. Gandhi himself would invoke the 1858 Proclamation when demanding British redress against racial discrimination in Natal. Earlier in India, on the assumption – all too correct during Lytton’s viceroyalty – that the Calcutta government was dragging its feet and was less receptive to Indian aspirations than were the British people, leading Indian protest groups despatched representatives to London and set up branches there. One of the earliest such organisations was the East India Association founded in 1866 by Dadabhai Naoroji, a successful businessman and a member of Bombay’s small but immensely influential Parsi community (so-called because they subscribed to the Zoroastrian faith of pre-Islamic ‘Pars’, or Persia, whence their forebears had sought sanctuary in India). Much of Dadabhai Naoroji’s career was spent in London, where he attracted a succession of high-flying Indian professionals who returned to India to lead many of the associations which eventually subscribed to Congress. He himself attended the first Indian National Congress and was elected president for the second. The better to represent Indian opinion in London he later became a Westminster MP. In 1893, while still sitting in the House of Commons, he would again return to India and the presidency of Congress.

The uncompromising imperialism of a Lytton (1876–80), or the temporising of a Dufferin (1884–8), encouraged such circumventory tactics. Conversely a Liberal viceroy like Lord Ripon (1880–4) was expected to be as sympathetic to Indian demands as was Gladstone to Irish demands, and could therefore expect nationalist support. Yet Ripon, repeatedly thwarted by the caution of the India Office in London and by the opposition of his own officials in India, delivered much less than he promised. He had the pleasure of repealing Lytton’s draconian censorship of the vernacular press, and he introduced a degree of local self-government with the inauguration of municipal and rural boards whose members, partly elected, were to assume responsibility for such things as roads, schools and sewerage. Implementation proved more difficult, especially in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras, where the main deluge of suitably educated Indians met the high dam of greatest official suspicion. Moreover, highly qualified patriots who were exercised about the iniquities of Naoroji’s drain theory found it hard to get excited about actual drains. Yet they liked Ripon’s ideas, they appreciated the need for a political induction which started at the bottom of the ladder, and they eagerly awaited the invitation to climb to the next rung.

This prospect receded in 1883 when the innocuous-looking Ilbert Bill provoked a ‘white backlash’ from India’s British residents. The bill, introduced by the Calcutta government to iron out a minor legal anomaly, was found on close examination to entitle a few Indian barristers who had now risen to the level of district magistrates and session judges to preside over trials of British as well as Indian subjects. This was too much for the planters and businessmen who made up the bulk of the European community. That there had to be Indian judges was one thing, but that an Indian judge might pronounce sentence on a member of the ruling race, perhaps even a female member of the ruling race, provoked the entire community into a hysterical and undisguisedly racist uproar. Memories of Kanpur and the ‘red mutiny’ were resurrected; Ripon was threatened; and, mindful of the ‘indigo’ or ‘blue mutiny’ of 1860, irate loyalists now promised a ‘white mutiny’ which would seal the fate of such a treacherous government. Their campaign ‘gave Indians an object lesson in the arts of unprincipled, but highly organised, agitation’;8 it was also notably successful, emasculating Ilbert’s bill and discrediting most of Ripon’s other reforms. Here was another British ‘idiom’, another form of ‘discourse’, more raucous than that of the durbar and evidently more potent; it, too, would in due course be emulated.

The histrionics over the Ilbert Bill had come mainly from Bengal, whose British planters, industrialists and traders were much the most numerous. But Bengal also fielded much the largest body of Western-educated and articulate Indians. They rallied to Ripon’s defence and, in loyal support of a cause which for once transcended creed, caste, class and locality, they were joined by fellow activists from all over India. Hailed as ‘a constitutional combination to support the policy of … Government’, this dignified and carefully orchestrated demonstration of all-India support found eloquent expression in the Bombay send-off arranged for Ripon in late 1884.

From Madras and Mysore [reported the Times of India ], from the Panjab and Gujarat, they came as an organised voice, from the communities where caste and race had merged their differences … waving their banners, rushing along with the carriages, crowding the roofs, and even filling the trees, and cheering their hero to the very echo … in order to express their appreciation of the new principles of government.9

In December 1885, exactly one year later, also in Bombay, and partly inspired by this demonstration of all-India action, the first Indian National Congress was convened. As yet Congress was just that – a congress, a gathering; not a movement, let alone a party. It was not unique; another national convention was meeting simultaneously in Calcutta (they would merge in the following year). Nor was it exclusively Indian. Its acknowledged founder, Allan Octavian Hume, was an ex-Secretary for Agriculture in the Calcutta government, a distinguished ornithologist and a Scot. Like his father, a Liberal radical who had spoken ‘longer and oftener and probably worse than any other Member [of the Westminster Parliament]’ in support of every imaginable reform, repeal and abolition, A.O. Hume had long been a thorn in the side of the authority he served. He had been particularly critical of ‘the millions and millions of Indian money’ squandered by Lytton, both on the Imperial Assemblage in Delhi and then on the Second Afghan War which in 1878 climaxed another confused passage of play in the interminable ‘Great Game’ between the British and Russian empires in central Asia.

After Lytton, in the happier times of Ripon’s viceroyalty, Hume had come to see himself as a conduit between Government House and its Indian subjects. The role no doubt appealed to him, as an associate of the Theosophists who from their base in Madras energetically espoused Hindu revivalism while seeking ecstatic encounters with spiritualistic go-betweens; indeed, ‘mystical mahatmas’ seem to have figured prominently amongst Hume’s anonymous Indian informants. There was nothing discreditable in such ‘contacts’. Late Victorians relished spiritual experiments; and in India Theosophy was one of many revivalist movements which were significantly contributing to the climate of social reform and religious and cultural rehabilitation in which national regeneration would flourish.

To the British it seemed that many of these reform movements cancelled one another out. Social reformers who demanded, for instance, an end to child marriages were opposed by religious revivalists who resented any interference with existing custom; in the north, champions of the Hindi language antagonised the heirs of Urdu’s literary heritage; and Marathas invoking the memory of Shivaji to sanction acts of violence were contradicted by universalist movements like the Brahmo Samaj whose adherents stressed the humanity and non-violence of Hinduism. In Bengal, as in Maharashtra, the literary and largely Hindu renaissance often bracketed British rule with that of the Muslim emperors and nawabs which had preceded it, both being deemed equally alien. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee went even further. In his immensely influential novel Anandamath (1882), Hindu leaders appeared to be struggling not against the British, who had supposedly come to India as liberators, but against Muslim tyranny and misrule.10

Needless to say, Muslims took exception to this as to much else about the predominantly Hindu character of many of these movements. In the north they responded both with a burst of fundamentalist activity which appealed to poorer Muslims and with a drive towards a more flexible and outward-looking orthodoxy which could accommodate a degree of Westernisation. The latter trend was well represented by Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan who in 1875 founded the Anglo-Muhammadan Oriental College, later University, of Aligarh (south-east of Delhi).

All these movements and associations would endow the political struggle with strong spiritual, cultural and social undertones. In the case of Vivekananda, the first of India’s ‘gurus’ to address a world audience, they served to alert international opinion. In the case of the Arya Samaj, a reformist and aggressively Hindu ‘Aryan Movement’ which made spectacular advances in the Panjab, they drew on fashions in international scholarship, specifically the pan-Aryan enthusiasms of Max Muller, the Oxford Professor of Sanskrit. Additionally the high-profile Theosophists set a useful organisational example with their annual conventions. But it was the mainstream political groupings of Calcutta, Bombay and Pune, heavily influenced by Dadabhai Naoroji and his associates, which first urged the need for a national congress; the organisation for such a gathering had come into existence at the time of Ripon’s send-off demonstrations in the winter of 1884;11 and Allan Hume was regarded by the British authorities as the prime instigator. Additionally, by the seventy-two delegates who attended the first Congress, he was seen as an able organiser and, because unaligned as to caste and community, as the most suitable secretary and spokesman.

Hume also had more time and money than most to devote to the Congress. For the next decade it existed as an annual gathering, organised by a local committee in whichever city had been chosen to host it, and presided over by a president chosen for that one occasion. ‘There were no paying members, no permanent organisation, no officials other than a general secretary [usually Hume], no central offices and no funds.’12 It met over the Christmas break, thereby ensuring that the professional careers of the principally lawyers, journalists and civil servants who attended were not unduly disrupted. Proceedings were conducted in English, the only language shared by all delegates; and given the Congress’s pan-Indian character, resolutions focused on those national, as opposed to local or communal, issues around which delegates could be expected to unite.

Not surprisingly, the first years of Congress would therefore come to be seen as years of caution and moderation. Dufferin would sneer that it represented only ‘a microscropic minority’. Lord Curzon (viceroy 1899–1905), though conceding that its semi-permanent committees now made it a ‘party’, insisted that it was ‘tottering towards its fall’. Frustration led even supporters to decry the Congress’s ‘mendicancy’ when in the 1890s its ritual demands for political, administrative, and economic concessions, as also its pitiful funds, were rerouted through its London subsidiary. Although Congress continued to aspire to the status of an embryonic Indian parliament, its hopes lay with the Westminster Parliament, with allies in the British Liberal Party, and with the London lobbying of the likes of Dadabhai Naoroji.

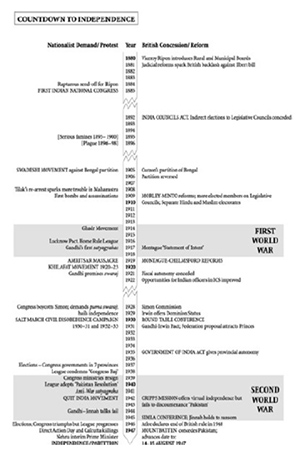

An 1892 India Councils Act was accounted a notable Congress triumph. It broadened the remit of the Legislative Councils which advised the viceroy and his provincial governors and to which Indians were already being nominated. It also increased the membership of these councils and conceded that in principle some members might be elected, albeit indirectly. This was a far cry from swaraj (self-rule), the avowed objective of many Congress speakers, but it did ensure more Indian representation at the political level. Access to the higher grades of the administration also looked to have been secured when in 1893 the Westminster Parliament acceded to Congress demands for entrance examinations into the elite Indian Civil Service to be held in India as well as England. In the event this measure was aborted by the government in India on the grounds that free and accessible competition would be discriminatory. It would favour, they said, the educated and mainly Hindu elite, so alienating less academic communities like the Muslims and Sikhs of the north-west on whose loyalty the Indian army, and so the British Raj, particularly relied.

Muslim attendances at Congress were already falling away. Hume had assiduously wooed Muslim support but, with his retirement to Britain in 1892, the opposition of Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan became more pronounced. Anticipating the arguments which would eventually lead to the genesis of Pakistan, Khan insisted that representative government might work in societies ‘united by ties of race, religion, manners, customs, culture and historical traditions [but] in their absence would only injure the well-being and tranquillity of the land.’ The land in question he liked to portray as a bright-eyed bride, one eye being Hindu, the other Muslim, and each equally brilliant. Any cosmetic enhancement which had the effect of favouring one over the other would ruin the whole countenance.

Resentment of Congress, and especially the elitist, ‘mendicant’ and Anglophone tone of its leadership, came also from non-Muslims. In the late 1890s, against a background of industrial unrest, more appalling famines and an outbreak of plague, the first signs of a polarisation in the Congress ranks began to appear in Maharashtra. Moderates who favoured constitutional methods, albeit backed by trenchant economic and political critiques, became identified with Ferozeshah Mehta and Gopal Krishna Gokhale, whose power base was amongst the Bombay intelligentsia. Meanwhile radicals gravitated towards the Marathi populism and the more experimental methods urged by Bal Gangadhar Tilak from his power base around Pune.

British Viceroys

Gokhale, a lecturer at Bombay University, and Mehta, a Parsi lawyer, accepted the need for patience and moved easily between the presidency of Congress and membership of the viceroy’s council. Tilak, on the other hand, from the same brahman community which had furnished the Maratha state with its peshwas, experimented with a variety of mass-focus appeals through his editorship of a Marathi newspaper. They included the politicisation of fairs and festivals associated with the local cult of Ganapati (Ganesh) and a patriotic crusade based on the defiance of Shivaji. Tentative boycotts and exhortations to civil disobedience were also tried. In 1897 Tilak’s exposition of Shivaji’s most famous exploit, the disembowelling of the Bijapuri general Afzal Khan with those fearsome steel talons, was taken to have incited the assassination of a British official. Sentenced to prison, Tilak, the scapegoat for this first successful act of terrorism, duly became Tilak, the martyr for the nationalist cause. A repeat performance in 1908 would galvanise all Bombay. Tilak had made the important discovery that the consequences of extremist rhetoric could transcend its appeal.

Bengali luminaries, including Aurobindo Ghose, the social and religious reformer, and Rabindranath Tagore, the poet, philosopher, educationalist and first Indian Nobel laureate for literature, also sought to broaden the base of the struggle. The former’s advocacy of passive resistance and the latter’s of psychological, educational and economic self-reliance were both, however, dramatically subsumed in the explosion that greeted the partition of Bengal in 1905. Courtesy of the British and the greatest of their proconsuls, rather than of the stridency of Congress, the first phase of the national struggle was about to peak.

DIVIDE AND UNITE

George Nathaniel Curzon, Baron of Kedleston, had equipped himself for viceregal authority like no other British viceroy. He had had India on the brain since his schooldays at Eton, and ‘as early as 1890 he had admitted at a dinner in the House of Commons that [the viceroyalty] was the greatest of his various ambitions’.13 Perhaps it had something to do with the familiar aspect of Government House in Calcutta. The viceregal residence, built by Wellesley a century earlier, had been modelled on the Curzon family’s Kedleston Hall. By design, as it were, a home from home awaited him in India.

But characteristically he had recommended himself for the job by travelling and writing extensively not about India itself but about its landward frontiers and the central Asian wastes beyond. For to Curzon, India’s appeal resided in its status as the proverbial jewel in the imperial crown. ‘For as long as we rule India,’ he told Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, ‘we are the greatest power in the world.’ That made the viceroyalty the jewel of imperial patronage; and who better to wear it than George Nathaniel Curzon, that ‘most superior person’ (as one rhymester had put it)? By common consent Curzon was not only the most brilliant scholar-administrator of his day but also the soundest of imperialists. In words which would have dashed a few hopes in Congress, he told Balfour that it would ‘be well for England, better for India and best of all for the cause of progressive civilisation if it be clearly understood that … we have not the smallest intention of abandoning our Indian possessions and that it is highly improbable that any such intention will be entertained by our posterity’.14

As viceroy, one of Curzon’s less controversial achievements would be the establishment of India’s Archaeological Survey, set up to revive the work of recording and preserving what he rightly hailed as ‘the greatest galaxy of monuments in the world’. India’s history fascinated him, and he was probably better informed about its languages and customs than any British ruler since Warren Hastings. But of its people as other than an administrative commodity and the decadent heirs of an interesting past he knew, and perhaps cared, little. Like the Taj Mahal to which he devoted much attention, India was a great imperial edifice which posed a challenge of presentation and preservation. It needed firm direction, not gentle persuasion. History, by whose verdict Curzon set great store, would judge him by how he secured this magnificent construction, both externally against all conceivable threats and internally against all possible decay. To this end he worked heroically and unselfishly; but his example terrorised rather than inspired, his caustic wit devastated rather than delighted. Even the British in India found him quite impossible.

To the troublesome north-west frontier, where British India petered out amongst mountains swept by gusts of Afghan disquiet and strewn with the debris of unsatisfactory campaigns, Curzon did indeed bring order. British troops were withdrawn from the Afghan frontier and a buffer zone was created within which tribal levies under British command were to keep the peace. Responsibility for this zone and for the whole area west of the Indus was in 1901 transferred from the Panjab province to a newly-created North-West Frontier Province. Further north, in the high Hindu Kush, British expeditions operating in the name of the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir had already pushed the frontier up to that of Chinese Sinkiang. This practically doubled the size of Kashmir and pre-empted any Russian approach by way of the Karakoram route. It also established the near physical impossibility of any such ‘invasion’. Nevertheless, by way of a lookout post over this ‘roof of the world’, the Gilgit Agency was retained, nominally as part of Kashmir territory.

East of Kashmir, the politically uncharted wastes of Tibet had frustrated repeated British overtures. To a mind as orderly as Curzon’s, the uncertainties posed by Tibet’s status and by the naivety and indifference of its monkish rulers were anathema. Doubtful rumours about a doubtful Russian spy in Lhasa were made into an imperative for intervention. With exasperation masquerading as policy, a military expedition commanded by Sir Francis Younghusband was despatched across the frontier in 1904. Militarily it fared better than Zorawar Singh’s frost-blighted invasion thanks largely to death-dealing inventions like the Gatling machine-gun. But the reports and, worse, the photographs of robed monks being mown down amongst the glaciers as they brandished hoes and fumbled with their flintlocks was a poor advertisement for imperialism. So much, noted nationalist critics, for ‘the cause of progressive civilisation’.

If civilisation was supposed to be progressive, government was supposed to be efficient. More railways were built and ambitious irrigation projects were undertaken, especially in the Panjab. The drive for greater efficiency lay behind most of Curzon’s internal reforms, and nowhere to greater effect than with the bureaucratic leviathan that was the government of India itself. Famously in 1901 he ridiculed the year-long odyssey of a particularly important proposal. ‘Round and round, like the diurnal revolution of the earth, went the file, stately, solemn, sure, and slow; and now, in due season, it has completed its orbit, and I am invited to register the concluding stage.’15 The file in question concerned another bit of territorial repackaging like the creation of the North-West Frontier Province. That alone was important enough to merit the viceroy’s early attention. But the file also mooted other such adjustments, including the break-up of Bengal.

The partition of Bengal would be Curzon’s nemesis. It fatally discredited the unyielding imperialism for which he stood, it sparked the first nationwide protest movement, and it introduced direct confrontation, plus a limited recourse to violence, into the repertoire of British–Indian ‘discourse’. Only the tidiest of minds would have tackled such a thorny project, only the most arrogant of autocrats have persisted with it. But as the largest, most populous and most troublesome administrative unit in British India, Bengal posed a worthy challenge. With a population, twice that of Great Britain, which was predominantly Hindu in the west and Muslim in the east, the administrative case for a division of the two brooked little argument. Curzon therefore pushed ahead.

He was not unimpressed by the view that Bengal’s highly vocal critics would also thereby be partitioned. ‘The best guarantee of the political advantage of our proposal is its dislike by the Congress Party,’ he told the secretary of state. But whether he understood the grounds for this dislike, or its intensity, may be doubted. In a 1904 speech in Dacca, the capital of the proposed new province of ‘East Bengal and Assam’, he assured Muslims that the new arrangement would restore a unity not seen since ‘the days of the Mussulman viceroys and kings’. This was presumably a reference to the heavily Persianised courts of the eighteenth-century nawabs; it may not, therefore, have had much resonance for East Bengal’s mainly low-caste converts to Islam. On the other hand it was certainly offensive to the mainly Hindu zamindars,patnidars, and their innumerable diminutives who were so well represented amongst the vocal Anglophone agitators of Calcutta.

Stock accusations of a wider Macchiavellian intent to ‘divide and rule’ and to ‘stir up Hindu–Muslim animosity’ assume some premonition of a later partition. They make little sense in the contemporary context. ‘Divide and rule’ as a governing precept supposes the pre-existence of an integrated entity. In an India politically united only by British rule – and not yet even by the opposition which it generated – such a thing did not exist. Division was a fact of life. As Maulana Muhammad Ali would later put it, ‘We divide and you rule.’ Without recognising, exploring and accommodating such division, British dominion in India would have been impossible to establish, let alone sustain. Provoking sectarian conflict, on the other hand, was rarely in the British interest.

Only ten years earlier the armies of Bengal, Bombay and Madras, which had been kept separate as a safeguard against another mutiny, had been quietly amalgamated. It was thought to be a more efficient arrangement; in that efficiency meant more effective deployment, this could be seen as a case of ‘unite and rule’. For similar reasons of imperial convenience the North-West Frontier Province had been carved out of the Panjab, and Bengal and Assam were now rearranged as West Bengal (with Orissa and Bihar) and East Bengal (with Assam). Arguably this partition should have reduced sectarian rivalry. More certainly, under a viceroy as committed to indefinite British rule as Curzon, there was no logic in stirring up conflict. At the time the nationalist challenge was being comfortably contained and Muslims were already boycotting Congress. More discord would merely defeat efficiency. It was costly to contain, it damaged British business interests, and it taxed the loyalties of the princely states and the now-united Indian army.

Such reasoning would duly surface when in 1911 it was announced that Curzon’s partition had been reversed and Bengal was to be reunited. Instead, Bihar and Orissa would be detached to form a separate province, and likewise Assam. The ‘unity’ promised to East Bengal’s Muslims thus lasted just six years. Their resentment was understandable. Nor was it soothed by the simultaneous announcement that Delhi, the erstwhile seat of a Muslim empire to which Bengalis had rarely been reconciled, was to replace Calcutta as British India’s capital (and be graced with a new New Delhi). If this was an acceptable idea to the Muslim gentry of northern India, it was meaningless to the Muslim peasantry of what is now Bangladesh. More obviously, Bengali Muslim resentment over the reversal of partition scarcely squares with the popular idea that it was Bengali patriotism which forced this reversal. All communities in Bengal did indeed share the same language, the same rich literature, the same distinctive history and the same passionate attachment to a delightfully mellow land. But the explosion of protest which had greeted Curzon’s partition and which had rocked much of India while the partition lasted had other causes.

Many related to the disadvantaged status and lost job opportunities which Bengali Hindus anticipated within a divided Bengal. In ‘East Bengal and Assam’ they would be a religious minority in a predominantly Muslim province; in ‘West Bengal with Orissa and Bihar’ they would be a linguistic minority amongst a non-Bengali-speaking majority. Wherever they lived they stood to lose by partition. Other grievances drew on the catalogue of demands being submitted by Congress and the negligible progress being made in their redress. But one outstanding objection, for which Curzon must be held directly responsible, was the appalling insensitivity with which the scheme had been imposed. As Gokhale apprised Congress at the end of 1905, no Bengali had been consulted, no objections entertained.

The scheme of partition, concocted in the dark and carried out in the face of the fiercest opposition that any government measure has encountered in the last half-a-century, will always stand as a complete illustration of the worst features of the present system of bureaucratic rule – its utter contempt for public opinion, its arrogant pretensions to superior wisdom, its reckless disregard of the most cherished feelings of the people, the mockery of an appeal to its sense of justice, [and] its cold preference of Service interests to those of the governed.16

Gokhale’s, it will be remembered, was the voice of moderation. Others preferred action to words. Mass rallies clogged the thoroughfares of Calcutta, Dacca and other Bengali towns. Pamphlets and petitions out-circulated the newspapers. Within a month of the government decree a popular proclamation had announced the extension of swadeshi protest to the whole of India.Swadeshi, meaning ‘of our own country’ or ‘home-produced’, expressed a determination to be self-reliant and included a strict boycott of imported products, most obviously British textiles. Those on sale were publicly destroyed and existing stocks became practically valueless; while Indian mills prospered and some hand-loom weavers resumed production, Lancashire manufacturers fumed.

Significantly it was in 1907 and as a result of enthusiastic swadeshi investment that Jamshed Tata, a Parsi mill-owner, diversified into foundry work with the launch of his Tata Iron and Steel Company based at what became the ‘steel-city’ of Jamshedpur in Bihar. The plant would become one of the largest in the world and the Tatas the greatest of India’s, and Congress’s, industrialist backers. Reversing dependence on imported manufactures and developing indigenous production had entered the nationalist soul. Whether as Gandhian self-suffiency or Nehruvian ‘import-substitution’, it would continue to inform economic thinking long after independence.

By pamphlet, press and word of mouth swadeshi protest was extended throughout India in a remarkable display of united and effective action which soon obscured the partition which had provoked it. The coincidence of Japan’s sensational victory over a major European power in the 1905 Russo–Japanese war fanned the movement and persuaded some that victory was nigh. In Bengal a more extreme form of boycott extending to government institutions, colleges and offices was widely urged, fitfully adopted, and brutally suppressed by cane-wielding security forces. It was also disowned by the rump of Congress, whose gradualism now appeared outdated. At the 1906 Congress a split was avoided by inviting the octogenarian Dadabhai Naoroji to take the chair for the third time and by some not very ingenious fudgi ng; one resolution boldly but nonsensically called for ‘Swaraj [self-rule] like that of the United Kingdom or the colonies’. In 1907 at Surat the divisions between ‘extremists’ like Tilak and ‘moderates’ like Gokhale could no longer be contained. The Surat Congress dissolved into chaos and was aborted.

Briefly an ‘extremist’ splinter group known as ‘Lal, Bal and Pal’ now made most of the running – as well as providing its youthful followers with a head-banging mantra. ‘Lal’ was otherwise Lala Lajpat Rai, the militant Arya Samaj leader from the Panjab; ‘Bal’ was the fiery Maratha revivalist Bal Gangadhar Tilak; and ‘Pal’ the radical Bengali leader Bipin Chandra Pal. Pal also edited the journal Bande Mataram, itself named after the patriotic Bengali anthem which, written by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, had been set to music by Tagore. Swadeshi ideals were extended to educational reform, labour organisation, self-help programmes and cultural activities. But in advocating a total boycott amounting to non-co-operation and including non-payment of taxes, ‘Lal, Bal and Pal’ invited a ferocious government clampdown. In 1907, fifty years after the last Mughal had been packed off to Burma, an untried ‘Lal’ trod the deportee’s road to Mandalay, and in 1908 he was followed by ‘Bal’. Tilak’s trial for incitement had brought Bombay’s industries to a standstill; for leftist nationalists this ‘massive outburst of proletarian anger … remains a major landmark in our history’.17 The even more explosive response to his six-year sentence brought troops onto the streets and sixteen reported deaths. In a quieter Mandalay, Tilak consulted his traditional inspiration. While awaiting the dawn ‘like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay’, he wrote a commentary on the Bhagavad Gita.

His offence had been that of apparently condoning terrorism. ‘The sound of the bomb’, a spontaneous response to government repression according to Tilak, was first heard in Bengal in 1907 when the lieutenant-governor’s train was derailed. More tragically two Kennedys, a mother and daughter, were killed at Muzaffarapur in Bihar in 1908; a bomb had been lobbed into their carriage in the mistaken belief that it was that of an unpopular magistrate. The apprehending of the culprits led to the discovery of a munitions factory in the garden of the Calcutta home of the Ghose brothers. Aurobindo Ghose was amongst those brought to trial. Disillusioned, he, like Tilak, then found in religion a ‘royal road for an honourable retreat’.18 In Pondicherry (still under French rule) he also found a sanctuary from British rule and a site for his proposed ‘Auroville’, an urban experiment in internationalism and cross-cultural collaboration. Unlike Tilak in Mandalay, he would stay there.

Sporadic assassinations and ‘swadeshi dacoities’ (political crimes) continued, notably in Maharashtra and Bengal. Clandestine revolutionary groupings headed by V.D. Savarkar, Rashbehari Bose and others also made contacts outside India. In 1909 London itself witnessed its first Indian atrocity when Sir Curzon Wyllie, an India Office official, was gunned down by a Panjabi, Madanlal Dhingra.

Such assassination attempts, many of them botched, remained a threat to both British and Indian officials. The only viceroy to die in a terrorist attack would be the last – Lord Louis Mountbatten – and the nationalists responsible would be Irish rather than Indian. But in 1913 Lord Hardinge, one of Mountbatten’s vice-regal predecessors, would have a bomb tossed into his howdah while making his ceremonial entry into Delhi to mark its adoption as the new capital; severely wounded, both viceroy and elephant yet survived. The culprit proved to be one of Rashbehari Bose’s Bengali followers. ‘They gave us back the pride of our manhood,’ writes an irresponsible but not untypical apologist for these first ‘revolutionaries’.19 Happily by 1910 their threat was being contained and the ‘moderate’ Congress rump, headed by Gokhale and Mehta, at last had something to show for its moderation.

Curzon had resigned as viceroy within days of the Bengal partition, although not as a result of it; the affront to his dignity from a petty row with his notorious commander-in-chief, Lord Kitchener, proved a more fatal wound than swadeshi. His successor, Lord Minto, reached India in late 1905 just as a Liberal ministry was taking over in London. With the appointment of the Liberal scholar John Morley as Secretary of State for India a new programme of reforms/concessions had soon come under consideration. These did not materialise till 1909, but knowledge of their preparation, plus swadeshi’s assertion of mainly Hindu demands, prompted a Muslim deputation to the viceroy at Simla in late 1906.

Not without British encouragement, the Muslim deputees cited the underrepresentation of Muslims amongst those Indians already elected to official bodies and demanded that any future reforms include separate electorates for Muslims. They also wanted a weighted system of representation which would reflect the size of the Muslim population and the value of its ‘contribution to the defence of the empire’. Headed by the Aga Khan and heavily supported by mainly landed and commercial Muslim interests in the United Provinces (which were the same as the early-nineteenth-century North-West Provinces and the future Uttar Pradesh), the deputees had inherited Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan’s distrust of Congress. In early 1907 they duly consummated this distrust by forming the All India Muslim League. Not all Muslim interests supported them, however. Some groups continued to subscribe to Congress, amongst them one headed by a brilliant young Bombay lawyer, Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

The Morley–Minto Indian Councils Act, when it at last materialised in 1909, was the first major reform package since the 1892 Councils Act and apparently did no more than, as Minto put it, ‘prudently extend’ the principle of representative institutions. The councils in question were those attached to the central government, still in Calcutta but about to remove to Delhi, and to the now numerous provincial governments in Madras, Bombay, Agra (for the United Provinces), Lahore (for the Panjab and North-West Frontier provinces) and so on. Known as Legislative Councils, all were now increased in size; more seats were to go to non-officials and more of these non-officials were to be indirectly elected. With up to sixty members the Legislative Councils would thus accommodate more Indians, some of whom would represent a wider spectrum of Indian opinion. They became in effect chambers rather than councils and, although Minto disclaimed the very idea, could be seen to foreshadow a parliamentary system.

But they were not legislatures and had no power to initiate or frustrate legislation, merely to question and criticise it; India remained a British autocracy, albeit a consultative one. Additionally, an Indian member, Satyendra Sinha, was co-opted onto the viceroy’s Executive Council, and in London two Indians served on the council which advised the Secretary of State for India.

The reforms were initially welcomed by Congress, but not by the Muslim League. When supplementary regulations later revealed that some seats were indeed to be reserved for Muslims and elected only by Muslims, the situation was reversed; Congress complained and the League rejoiced. Other seats were reserved for other sectional interests. It was not the principle of reservation which caused controversy but that of a separate electorate for the perhaps 20 per cent of the population, distributed throughout the subcontinent, who happened to adhere to Islam. Fairly in the subsequent view of Pakistanis, fatally in that of most citizens of the Republic of India, the principle of a separate electorate along sectarian lines had been conceded to a fifth of all Indians.

It would be impossible to deny that the arrangement suited British interests. But once again it was hardly an insidious application of ‘divide and rule’. It neither fractured an existing consensus nor prejudiced any future consensus. No division had been created that did not already exist, no demand created which could not subsequently be accommodated. In fact, seven years later, Congress would itself accept the principle of separate electorates. The 1916 Lucknow Pact, by which Congress and the League agreed a joint programme, would see the League accept Muslim under-representation in Muslim majority areas (like East Bengal) in return for Congress’s acceptance of Hindu under-representation in Hindu majority areas (like the United Provinces). Here was precisely the political horse-trading essential to the working of a plural society. Both sides embraced it; so even did an ‘extremist’ like the lately returned Tilak. At this stage, with one partition having just failed, another was not only unthinkable; it was eminently avoidable.